Abstract

Eight Views is a time-honored East Asian cultural-landscape paradigm in which eight emblematic natural—cultural scenes fuse regional character, historical memory, and aesthetic ideals into a coherent narrative. It encodes the collective memory and identity of a city (or garden/region), a premodern ‘mental map’ or proto- ‘city brand’. In China, the historic Urban Eight Views are rooted in local environments and traditions and constitute significant, high-value landscape heritage today. Yet rapid urbanization has inflicted severe physical damage on these ensembles. Coupled with insufficient holistic and systemic understanding among managers and the public, this has led, during development and conservation alike, to spatial insularization, fragmentation, and even disappearance, alongside widening divergences in cultural cognition and biases in value judgment. Taking Longmen Haoyue in Chongqing, one of the historic Urban Eight Views, as a case that manifests these issues, this study develops a holistic–relational approach for the urban, historical Eight Views and explores landscape-based pathways to protect the spatial structure and cultural connotations of the heritage that has been severely damaged and is in a state of disappearance or semi-disappearance amid modernization. Methodologically, we employ decomposition analysis to extract the historical information elements of Longmen Haoyue and its internal relational structure and corroborate its persistence through field surveys. We then apply the FAHP method to grade the conservation value and importance of elements within the Eight Views, quantitatively clarifying protection hierarchies and priorities. In parallel, a multidimensional corpus is constructed to analyze online dissemination and public perception, revealing multiple challenges in the evolution and reconstruction of Longmen Haoyue, including symbolic misreading and cultural decontextualization. In response, we propose an integrated strategy comprising graded element protection and intervention, reconstruction of relational structures, and the building of a coherent cultural-semantic and symbol system. This study provides a systematic theoretical basis and methodological support for the conservation of the urban historic Eight Views cultural landscapes, the place-making of distinctive spatial character, and the enhancement of cultural meanings. It develops an integrated research framework, element extraction, value assessment, perception analysis, and strategic response that is applicable not only to the Eight Views heritage in China but is also transferable to World Heritage properties with similar attributes worldwide, especially composite cultural landscapes composed of multiple natural and cultural elements, sustained by narrative traditions of place identity, and facing risks of symbolic weakening, decontextualization, or public misperception.

1. Introduction

As a traditional landscape-narrative paradigm that originated in China and spread across East Asia, the Eight Views fuses natural landforms with human memory through poetic and pictorial imagery, constituting a typical practical manifestation of UNESCO’s ‘cultural landscape’ concept. The ‘eight’ in Eight Views is not always literally eight; rather, it is a conventional label for a set of representative scenic spots. Examples such as the ‘Twelve Views of Ba-Yu’ in Chongqing, the ‘Ten Views of West Lake’ in Hangzhou, the ‘Eight Views of Macao’ in the Historic Centre of Macao, the ‘Eight Views of Xunyang’ in Jiujiang (Figure 1a), Japan’s ‘Eight Views of Omi’ [1] (Figure 1b), and Korea’s ‘Tongdosa Eight Views’ demonstrate that this narrative mechanism, centered on ‘Eight Views,’ not only imbues material landscapes with poetry and historical memory but also serves as a key cultural driver for the recognition of Outstanding Universal Value.

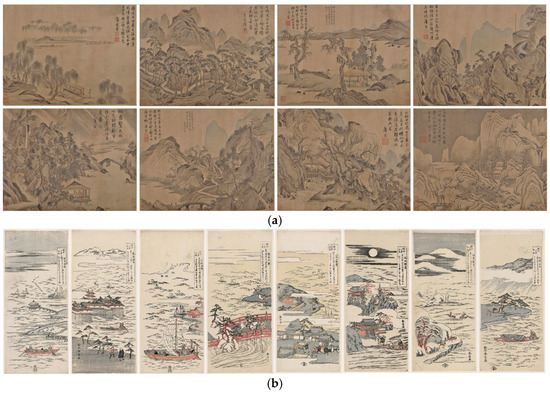

Figure 1.

Eight Views unites landscape, painting, and poetry, turning ‘nature observation’ into ‘spiritual expression’: (a) Tang Yin, Xunyang Eight Views (1515) [2] and (b) Suzuki Harunobu, Eight Views of Omi (1760) [3].

The rapid advance of urbanization has brought profound economic, social, and cultural transformations to developing countries [4], while simultaneously posing severe challenges to cultural heritage conservation, most notably to the materiality, integrity, and authenticity [5,6] of China’s Urban Eight Views.

Over the past four decades of accelerated economic growth, historic Urban Eight Views have suffered extensive damage. Paradoxically, in recent years conservation practices have exhibited the contradictory phenomenon of ‘unprecedented attention alongside unprecedented destruction.’ In response, governments have undertaken a series of protective measures. Yet in most Chinese cities, protected areas still rely on setback- and boundary-based demarcation methods that, although they define the core material elements and their immediate surroundings with some clarity, often fail to adequately encompass spatial structures, cultural connotations, visual relationships, and functional linkages. At the same time, lagging and disjointed delimitation and planning by municipal authorities have led, in practice, to increasing fragmentation [7] and insularization [8] of the Urban Eight Views, again reflecting the contradiction of ‘unprecedented attention, unprecedented destruction’ [9].

This fragmentation and insularization is further exacerbated by land development and land-use change, which intensify the breakup of scenic space and produce a marked ‘islandization’ of core elements within the city. For example, conservation practices for Guangzhou’s Zhenhai Tower (‘Zhenhai Cenglou’) and Kaifeng’s ‘Bright Moon over Zhouqiao Bridge’ (‘Zhouqiao Mingyue’) have often focused narrowly on a single building or bridge while neglecting their intrinsic connections to urban sightlines, flanking architecture, streets and lanes, and other elements. As the concept of sustainable development gains global traction, heritage conservation is being progressively integrated into urban development strategies [10,11,12,13]. The central challenge has thus become ‘how to identify workable conservation pathways that balance preservation and development’ [14,15,16].

As an urban historical landscape, the Urban Eight Views constitute an organic whole composed of multiple tangible and intangible elements. To transcend the limitations of single-object protection and to address the problems of fragmented conservation units, severed spatiotemporal dimensions, missing conservation contexts, and imbalance between protection and development, urban heritage conservation must safeguard all necessary heritage elements [17,18]. In other words, the conservation focus for Urban Eight Views has shifted from partial to holistic strategies [19,20]. Such strategies not only emphasize the static landscapes embodying the co-existence of nature and culture, but more importantly seek to maintain their dynamic integrity through processes of change and development [21,22,23], thereby forming a ‘complete’ contextual perspective that encompasses living neighborhoods, evolving cultural lineages, and a rich cultural ecology [24,25]. A more comprehensive, i.e., holistic, approach, is therefore essential to the conservation of urban heritage.

Nevertheless, the conservation of such urban historical landscapes seeks to move beyond traditional ‘historic center’ or ‘complex-based’ models by integrating the urban environment of both tangible and intangible heritage. In practical application, however, how to deploy these ideas at the finer scale of the Urban Eight Views, so as to achieve more comprehensive and operational conservation, remains a critical, unresolved task.

In response, this study proposes a holistic–relational conservation theory and applies it systematically to the representative case of ‘Longmen Haoyue’ in Chongqing’s historic Urban Eight Views. Our aim is to construct a conservation-planning model and toolkit suited to urban historical Eight Views that are on the verge of disappearance or in a semi-disappearing state. By developing an element classification inventory, a relational mapping of linkages, a value-weighting system, and targeted intervention strategies, this research provides a new theoretical framework and practical reference for the holistic conservation of cultural landscape heritage and for urban planning and management.

2. Literature Review

Heritage conservation has shifted from an object-centered monument paradigm to a relational perspective that places the landscape, systems, and community at the core [26,27], understanding heritage as a dynamic network co-produced by human practice, institutions, place, and nature, rather than as static remains [28,29,30]. Within this framework, heritage is seen as a multi-scalar, transboundary, and continually evolving complex system whose value derives from interactions and negotiation among elements [31,32,33], rather than from isolated objects per se [34]. This conservation philosophy was institutionalized in the 2011 Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape (HUL). HUL situates the ‘built environment and its setting’ within a unified socio-economic and cultural-historical urban context and advocates for making relational networks themselves the objects of conservation [35,36,37,38,39]. Complementary tools, LCA and HLC, provide identification and stratification from the perspectives of ‘landscape character assessment’ and ‘historic landscape characterization’ [40,41,42,43], supporting systematic understanding from regional- to whole-territory scales. The holistic–relational approach is both an application and an extension of this mode.

‘Holism’ no longer equates to a simple morphological collage in conservation, but instead to the organic unity of material, functional, and cultural dimensions within dynamic development. On the material plane, the integrity and indivisibility of the morphological framework, buildings, street networks, water systems, topography, and skyline are fundamental [44,45]. Functionally, everyday operations, residence, commerce, transport, and ecology sustain living values and require integrated conservation with the urban system as a whole [46]. Culturally, intangible heritage, memory, and place attachment must be conserved together with their material carriers as one ‘whole,’ while community identity and participation constitute the social foundation of those carriers [47].

Excavating ‘relationality’ means converting the ‘latent networks’ within heritage into explicit evidence. At the spatial level, multiple relational modalities, view corridors, axes, skyline, and grain continuity, shape the urban image and the collective legibility of heritage [48,49,50]. At the functional level, revealing couplings among systems, such as watercourses and gardens, streets and markets, religion and community, traces the resource flows and mutual-benefit structures through which heritage operates [51,52]. At the cultural level, narrative chains, symbolic systems, ritual paths, and oral memory ‘spatialize’ and render cultural relations explicit [53,54,55]. In heritage conservation, relations are not self-evident; they require mixed methods to uncover and thereby become identifiable, reviewable, and negotiable objects of governance.

In global practice, the notion of the ‘built environment and its setting’ permeates the entire process of identification, analysis, and conservation. At the element-identification stage, Suzhou maps the compound pattern of ‘gardens–historic city–water networks’ creating an inventory that spans the object itself, street grain, hydrological network, and viewsheds [56]; Pingyao identifies tangible and intangible heritage and their social bases through the tripartite lens of ‘livelihood–culture–space’ [57]. In relational analysis, Ballarat employs 3D modeling, viewshed simulations, and scenario testing to convert abstract relations into quantifiable ‘relational evidence’ [58]; Edinburgh delineates key views and skyline anchors to clarify structural visual linkages [33]. In strategy formulation, Suzhou and Pingyao institutionalize holistic objectives through incorporation into statutory planning and community-linkage mechanisms, while Edinburgh codifies visual controls as binding regulatory ‘red lines.’ At the implementation stage, Porto mainstreams heritage objectives into urban operations via a dedicated platform, whereas Florence advances cross-departmental coordination and adaptive governance through periodic plans [59]. Taken together, these practices indicate that only by organically linking element identification, relational analysis, holistic conservation, and institutionalized management can heritage conservation move beyond static preservation toward a new paradigm of systematized, negotiable, and sustainable integrated governance.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

Longmenhao (also known within Chongqing’s ‘Twelve Views of Ba-Yu’ as Longmen Haoyue, Ba-Yu is the historical name of Chongqing, see Figure 2) lies beneath the Dongshuimen Bridge in Nan’an District (N 29°33′38.584″–29°34′1.655″, E 106°35′54.334″–106°36′2.257″). Longmen Haoyue (literally, Dragon Gate Moon) is a several-hundred-meter reef within the Yangtze River of high historical value and emblematic of the distinctive singular charm and sublime beauty of Chongqing’s historic scenery [60]. Longmenhao’s historical importance resides in its unique geography and composite values as both cultural and natural heritage; it fuses landform and human ingenuity, encompassing the reef, port, river eddies, and ancient stone inscriptions, to reveal deep human–nature interactions. As a major shipping port in Chongqing, Longmenhao exerted far-reaching influence on local transport, economy, and culture, becoming a symbol of regional identity. Its inscriptions and archeological remains constitute precious evidence for the study of Bashu culture and the history of the Yangtze River basin, exemplifying traditional knowledge of hydraulics and navigation and serving as a representative historic landscape of continuing practical and cultural significance.

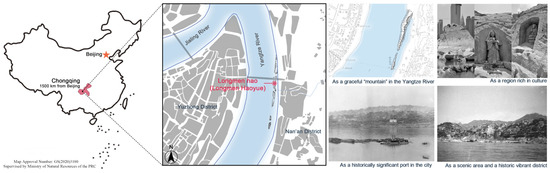

Figure 2.

Research on locational characteristics and the comparative analysis of historical and present conditions (Source: As a graceful ‘mountain’ in the Yangtze River [61], As a historically significant port in the city [62], As a scenic area and a historic vibrant district [63]).

Taken as a whole, Longmenhao (‘The Dragon Gate’) derives primarily from the natural landform. The Tushan Mountains extend into the Yangtze River, forming a massive mid-channel stone reef. This reef is cleaved by a natural gap at its center, like a ‘gate’ through which small boats could pass, hence the name ‘Longmen’. As early as the Song dynasty, the characters ‘龙门’ (Longmen) were carved on the rock in regular and running scripts [60]. Hao (‘The Port’), in Chongqing’s historical vernacular, denotes a small port. Longmenhao refers to the port established by and upon this natural reef [64]. For centuries, until the 1990s, it functioned as a crucial river port and ferry crossing for Chongqing [65]. Yue (‘The Moon-like Eddy’): when the Yangtze’s swift current strikes the Longmen reef, a large, circular vortex forms, resembling a full moon [60]. This is the origin of the ‘moon’ in Longmen Haoyue, a distinctive dynamic landscape born of the encounter between water and stone. With modernization, however, Longmenhao has gradually lost its original aesthetic, cultural, and port functions.

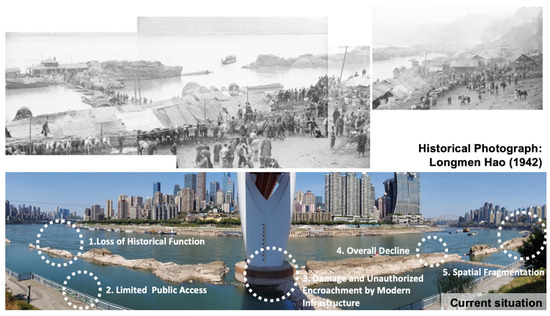

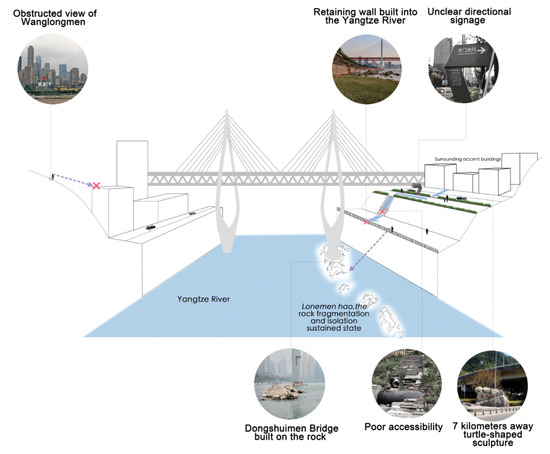

The piers of the Dongshuimen Bridge encroached upon the rock body [66], fracturing the once continuous reef into multiple isolated segments. As a typical representative of the Urban Eight Views, this ‘quick success’ model of urban development inflicted substantial damage on Longmenhao. Spatially, large portions of its natural and cultural elements have been compromised by urban infrastructure construction, leaving Longmenhao in a fragmented condition. Riverbank protective works along the Yangtze River have severed the Longmenhao reef from the adjacent Longmenhao Old Street (surrounding historic buildings) and impaired the mountain–river spatial continuum, rendering Longmenhao a ‘natural and cultural island’ within the city (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Historical and contemporary imagery of Longmen Haoyue and its present-day challenges (Source: Historical Photograph: Longmenhao [63]).

These impacts make the protection of Longmenhao highly urgent [67]. Most of its historical, natural, and cultural elements have disappeared, obscuring the continuity of the site’s history and necessitating the recovery of its historical components. On a holistic basis, a comprehensive inventory and survey of Longmenhao’s constitutive elements is required to identify extant and lost elements alike and to synthesize current problems. Building on such multi-level identification and analysis, and grounded in relational thinking, we will construct a conservation system that reintegrates Longmenhao into the urban landscape, addresses its present ‘island’ condition, and advances the broader conservation of Chongqing’s historic Urban Eight Views.

3.2. Constructing the Holistic–Relational Framework

The word ‘holistic’ [68,69], emphasizes a comprehensive grasp of the urban historical landscape as a composite system, with the explicit goal of achieving the comprehensive conservation of the Urban Eight Views. On this basis, protection must encompass not only the tangible heritage at the material level, such as buildings and vegetation, but also intangible components tied to the natural environment (e.g., landform and hydrology) and cultural practice (e.g., festivals and traditional activities) [70,71,72,73], thereby ensuring the integrity of the Urban Eight Views and their consonance with the broader setting. The word ‘relational’ [74], in turn, provides the methodological tools needed for unveiling internal and external linkages within the landscape and for achieving holism by revealing how elements connect. By analyzing spatial linkages [75] among landscape elements (e.g., view corridors), functional linkages [76] (e.g., ecological corridors), cultural linkages [77] (e.g., historical narratives), and temporal-historical layering, dispersed and damaged heritage components can be reintegrated into an organic whole [78].

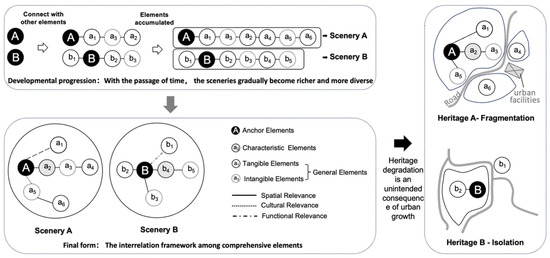

From a holistic perspective, the Urban Eight Views comprise diverse natural and cultural elements [79], which we classify into anchor elements, characteristic elements, and general elements. Anchor elements are the most central components of the Urban Eight Views and are core spatial elements that remain stable across temporal sequences and furnish points of reference for disclosing historical character. Characteristic elements are closely associated with anchor elements and serve to articulate spatial qualities. For instance, in Scenery A and Scenery B (Figure 4), each contains multiple tangible and intangible elements. Over time, the accumulation and interweaving of these rich and varied components produce distinctive landscapes. In topographic–hydrological setting, the mountain may function as an anchor element, yet it is not a singular existence. Attributes such as verdancy, height, and snow cover accentuate its distinctiveness and operate as characteristic elements. General (or associative) elements complement and complete the landscape through their multiple connections with the anchor element. For example, the bamboo grove on the mountain, the sound of the wind, or the stream together constitute the full set of elements of the ‘mountain’ landscape.

Figure 4.

A schematic illustration of the development of landscape elements, the modes of their combination, and the impacts of modern damage.

From a relational perspective, relationality is the core concept of urban historical landscape conservation and is an extension and deepening of the principle of holism. It stresses that the elements constituting heritage do not exist in isolation; rather, they are interconnected with both internal and external environments in spatial, cultural, and functional terms, collectively forming a complex network [80]. In practice, we analyze relationality along three dimensions that structure the landscape: spatial relevance is the physical armature, spatial pattern, and visual logic. Cultural relevance is the cultural and spiritual threads that link material carriers with intangible practices. Functional relevance is the internal logic of adaptive functions that support viable reuse.

Amid rapid urban development, scenery is transformed into heritage, yet that very pace of change tends to render heritage spatially fragmented and isolated [81,82,83]. Operationally, a holistic lens enables a systematic analysis of the distribution of characteristic elements within the Urban Eight Views and of their interdependencies, thereby fully disclosing the natural and humanistic components that are historically embedded in the landscape. Comparison with the current conditions then makes it possible to identify risks affecting both the material and intangible elements, and to provide an evidence base for scientific, systematic strategies of conservation and representation [35]. Moreover, the holistic–relational perspective fosters a comprehensive understanding of the constitution of spatial elements and their relational mechanisms, addressing imbalances between tangible and intangible components, the ‘islanding’ of scenic places, and the loss of overall sense of place. The result is that it more deeply reveals the intrinsic logic and cultural identity of the historic city, ensuring that while the heritage adapts to the contemporary societal needs, its historical values and distinctive qualities are transmitted and developed authentically and sustainably.

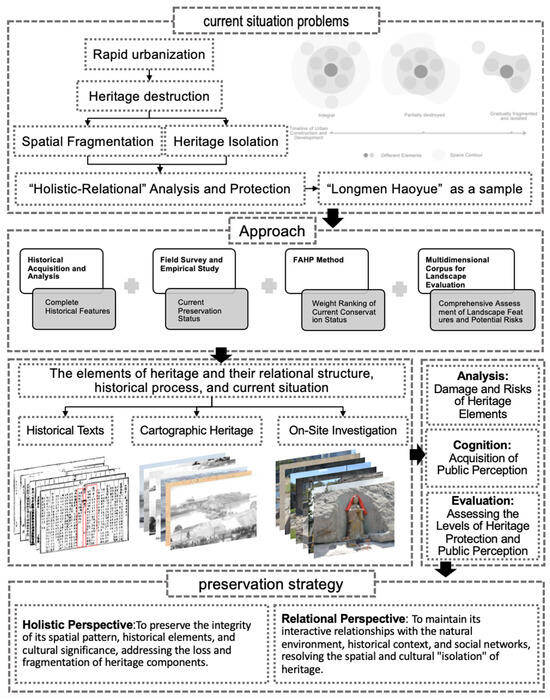

3.3. Overall Research Framework

1. Integrate holistic identification, relational analysis, and historical/field investigation into a unified workflow. Guided by the holistic–relational concept, the three components are designed as a sequential, interlocking process. We first conduct a holistic identification of the Longmenhao landscape using sources such as literature and historical maps. By classifying the anchor element, the characteristic element, and general/associative elements, we delimit the spatial extent and principal components, thereby disclosing the landscape heritage’s stable core and its internal linkages. Building on this inventory, we then carry out relational analysis to uncover the intrinsic connections and synergies among elements, as well as the internal logic and historical continuity underlying landscape formation. Finally, we incorporate a close reading of historical documents and the results of field surveys to validate the identification and relational findings. Fieldwork supplies detailed data on culturally relational elements and is crucial for systematic synthesis, preventing methodological silos and ensuring tight coupling between holistic understanding and fine-grained inquiry.

2. Differentiate quantitative evaluation from qualitative public perception assessment. For the quantitative component of landscape-heritage evaluation, we establish an indicator system grounded in holism, comprising material (tangible) metrics and material, relational metrics, to support assessment. For the multidimensional corpus-based overall evaluation, we emphasize the use of social media texts, tourist reviews, and related data to reflect public perceptions and preferences regarding the Longmenhao landscape. The two parts are complementary: quantitative evaluation addresses ‘what to protect’ and ‘where to prioritize,’ offering an objective basis for conservation planning. Public-perception analysis surfaces value orientations in the socio-cultural sphere, injecting the public voice into decision-making. Together, they balance differing value perspectives, such as expert preferences vs. popular tastes, academic valuation vs. lived experience, and objective standards vs. subjective feelings, to jointly underpin landscape conservation decisions.

3. Formulate targeted conservation strategies accordingly. Based on the preceding steps of identification, evaluation, and operationalizing the holistic–relational approach, we align strategy with assessed importance. For each identified element, we specify its protection content, priority level, and management/control measures within conservation and development, thereby translating evaluation results into actionable guidance (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Research framework for current issues, analysis approaches, and protection strategies.

3.4. Research Methods

3.4.1. Historical Retrieval and Spatial Decomposition, with Field Survey and Empirical Validation

From a holistic–relational perspective in heritage conservation, historical retrospection aims to resituate the observable present landscape within its long-term formative processes and render it intelligible. Its core objectives are: (1) to establish an integrity baseline; (2) to reconstruct multi-dimensional networks of relations, identifying severed critical linkages and recoverable corridors as evidence for the subsequent ‘reconnection’ in conservation; and (3) to calibrate authenticity and narrative coherence while developing an element genealogy to clarify conservation priorities. Accordingly, we employ historical retrieval and spatial decomposition analyses to examine the historical heritage.

Historical retrieval and spatial decomposition analysis systematically deconstruct and probe the spatial constitution of the Urban Eight Views. These ensembles comprise not only natural elements (e.g., land–water morphology, biotic features, and climatic variation) but also rich cultural components (e.g., historic architecture and epigraphic inscriptions) [84,85]. By integrating multi-perspectival sources, historical texts, and historical imagery the method aims to reveal the full inventory of elements embedded in the historical landscape and to clarify the heritage’s integrity.

Document analysis and literary text mining enables a systematic collation and critical comparison of successive sources, thereby reconstructing the historical landscape components and their evolution of “Longmen Haoyue.” We systematically reviewed gazetteers, histories, travelogs, and poetry spanning the Song, Yuan-Ming, and Qing periods through to the modern era. In particular, we located key sources including the Song-dynasty Shu Dao Yi Cheng Ji (《蜀道驿程记》) [86], the Qianlong Baxian Zhi (《乾隆巴县志》) [60] and Tongzhi Baxian Zhi (《同治巴县志》) [87], Chongqing Toponymy Gazetteer (《重庆地名志》) [88], and Nanan District Historical/Documentary Materials (《南岸区文史资料》) [89]. These texts record the geographic entities and scenic characteristics pertinent to Longmen Haoyue. Through textual mining and philological cross-checking, we extracted concrete historical depictions of Longmen Haoyue’s constituent elements and, by collating literary descriptions, assembled a complete set of historical spatial elements.

Historical image interpretation enables a synthetic reading of visual materials to reconstruct the diachronic evolution of landscape form and its cultural context. Archival photographs and paintings encode direct visual information about the landscape. We therefore compared images from different periods, paintings and photographs alike, as corroborative evidence to identify morphological changes. Coupled with stylistic analysis, this not only disclosed shifts in modes of representation across periods but also reflects the socio-cultural milieus and aesthetic preferences of each era.

Synthesizing typological insights from documents and imagery, we delineated element-change trajectories across the Song, Yuan, Ming, Qing, and modern/contemporary, periods. On the basis of the historical landscape prototype reconstructed via spatial decomposition, we then conducted field surveys and empirical checks to enable direct comparison between past and present conditions. Cross-validation enhances an integrated reading of historical transformation and functional transition, furnishing both a conceptual and empirical toolkit for urban heritage conservation and planning management.

3.4.2. Evaluation Methodology Construction

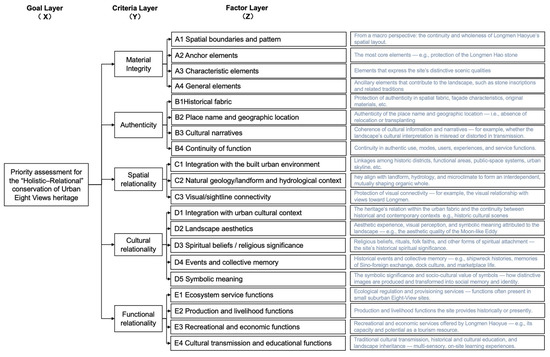

Under the holistic–relational conservation lens, we systematically classified the protection content of the Urban Eight Views into holistic and relational layers and then refined each into specific indicator factors. We applied a FAHP (here termed Fuzzy AHP), combined with expert scoring, to compute indicator weights and achieve quantitative assessment. Ranking factor weights clarifies priority orders required in practice, thus providing an evidence base for scientifically formulated conservation strategies.

In constructing the indicator system for evaluating the Urban Eight Views, protection priority serves as the goal level (X). The criterion level (Y) comprises material integrity/authenticity (holism), spatial linkage, cultural linkage, and functional linkage (relationality). Under each first-level criterion, we selected context-appropriate factor layer/second-level indicators (Z) to build a locally adapted, three-tier framework based on identified elements and widely recognized heritage values (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Indicator-based evaluation framework.

Step 1: Fuzzy complementary judgment matrix.

Using pairwise comparison among factors, we obtained a fuzzy matrix

with properties: (1) , (2) . We adopt a 0.1–0.9 numerical scale for pairwise importance (Table 1).

Table 1.

Scale 0.1–0.9: scales and meanings.

Here denotes equal importance, indicates the factor is more important than , indicates the opposite. Pairwise comparisons over yield the fuzzy complementary matrix.

Step 2: Weight computation.

To determine the weight vector of , we use

Step 3: Consistency testing.

We verify whether the weights are reasonable by testing comparative-judgment consistency. Excessive deviation implies unreliability for decision-making.

Definition 1.

Let,, be fuzzy matrices.

Define the compatibility index.

Definition 2.

Let

be the weight vector of fuzzy matrix

, with

, Define

and the characteristic matrix of as

The consistency ratio must satisfy

.

Step 4: Group decision aggregation.

Suppose experts compare the same factor set, producing fuzzy complementary matrices, . We aggregate individual judgments via the weighted geometric mean to obtain the group matrix

where is the weight of expert (here set equal, ). We then compute weights for and perform the above consistency test. If , the resulting weight vector is accepted as the final group decision weight.

3.4.3. Multidimensional Corpus for Overall Landscape Appraisal

Commercial or policy-driven heritage development can detach heritage from its historical contexts. Such selective interpretation often narrows and ossifies meaning, undermining cultural integrity. A multidimensional corpus allows us to capture how people perceive the landscape as a whole and, on that basis, to diagnose potential risks.

The study drew on multiple dominant platforms, including Dianping, Xiaohongshu, Douyin, Mafengwo, Ctrip, and Douban, spanning comprehensive lifestyle services, lifestyle communities, and travel sites, we compiled textual review data from the past five years (2019–2024). Given platform-reported demographics (with users aged 18–35 constituting >80%), these sources are well suited to reflect younger cohorts’ perceptions of heritage. Using seed terms such as ‘Longmen Haoyue (龙门浩月)’ and ‘Longmen hao (龙门浩),’ we collected 473 reviews/posts over 2019–2024 and expanded to related geographic anchors to reflect authentic public sentiment toward Longmen Haoyue.

After data cleaning and standardization, we applied NLP techniques to extract the top 40 core keywords. Frequency ranking and co-occurrence parsing then surfaced public perceptions and core value orientations, especially among younger users, thereby informing strategies for the sustainable cultivation of cultural integrity awareness for Longmenhao in the future.

4. Results

4.1. Identification Results: Historical Trajectory and Present Status of Heritage Elements and Their Relational Structure

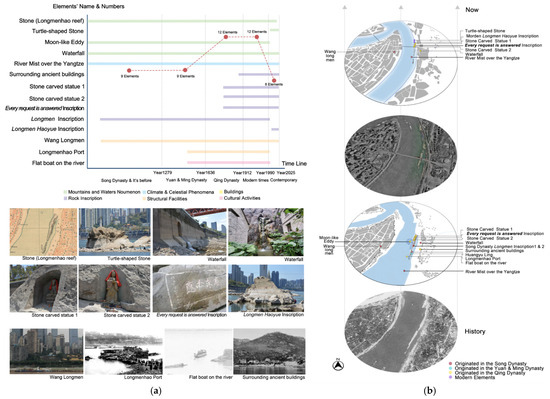

First, systematic collation and verification of pre-modern and modern sources yield concrete attestations of key elements. For example, the Baxian Zhi (Gazetteer of Baxian) records ‘to the right of Longmen lies a large gravel/shingle reef, named Huangyu Ling’ [87], identifying the rock/reef by name. It also explains Haoyue (‘Moon-like Eddy’) as follows: ‘The river flows from the southwest and sweeps over the reef, within the cove it slowly turns, and the current surges crosswise, at the river’s center the eddy whirls in a round motion, its course like the moon.’ [60] The Shudao Yicheng Ji notes: ‘Longmen is a riverside reef, broken in the middle like a gate, common folk call it Longmen. ‘Hao’, in the Ba-Yu dialect, a small port… Above the hao a waterfall hangs like a white silk sash, folding several times into the river’ [86], thus recording the historic waterfall at Longmenhao. The Chongqing Toponymy Gazetteer adds: ‘Only here does one stand across the Yangtze facing Longmenhao on the Nan’an bank, from this spot one can see, on the great rock at the mouth of the ‘hao’, the two characters ‘Longmen’ carved in the Shaoxing reign of the Song. People of old therefore called this place ‘Wanglongmen’’ [88] (literally ‘Viewing the Dragon Gate’).

By decomposing and analyzing textual descriptions, we tally 14 constituent elements of the ‘Longmen Haoyue’ ensemble across history. Specifically, 9 elements are recorded in Song-dynasty sources, 9 in the Yuan-Ming period, 12 in the Qing period, and 12 in the modern era. Field surveys of present conditions, interpreted against historical integrity, show that, owing to urban construction and functional shifts, the extant elements have been reduced to 8 (Figure 7a). Today, anchor elements with historical continuity have not vanished entirely but survive in a damaged or partially lost state. The core characteristic element, the Moon-like Eddy, has completely disappeared, and many general elements (e.g., the port, small boats, the ‘Longmen’ inscription in regular script, and other natural/cultural components), as well as the aesthetic relationships among elements, have been substantially lost (Figure 7b).

Figure 7.

(a) Number, dates, and photographs of surviving elements of Longmen Haoyue, (b) and historical and contemporary distribution of elements (Source: Stone [61], Longmenhao Port [90], Flat boat on the river [63], Surrounding ancient buildings [91], History satellite map [92], Now satellite map [93]).

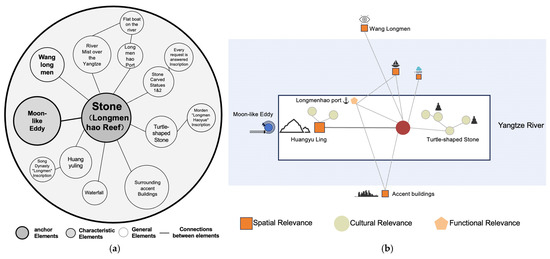

Second, we conducted an overall relational analysis of elements (Figure 8a). The resulting relational structure, an intrinsic network formed when material elements within a specific space are endowed with cultural value [78], in Longmenhao comprises functional, spatial, and cultural linkages that together generate an organic whole (Figure 8b).

Figure 8.

(a) Longmenhao’s anchor element, characteristic element, and general elements, and (b) schematic diagram illustrating the patterns by which a core element connects to different types of elements.

Functional linkages: The material substrate of regional development. Benefiting from favorable hydrological conditions afforded by the encircling reef, the area developed as a port. The two key material elements, the megalith in the Yangtze River and the Longmenhao Port, were tightly coupled by the practical needs of navigation and commerce. This utilitarian interaction forms the physical basis and original logic from which subsequent cultural meanings arise.

Spatial linkages: An environmental narrative organized by vision. Building upon functional foundations, spatial linkages organize dispersed elements through visual experience. The spectator practice of ‘Wanglongmen’ establishes a coherent view corridor that connects the elegant mid-channel reef, the moving boats, and the inscriptions on the bank, seamlessly integrating natural and humanistic scenes. In this way, the functional port becomes an experiential landscape legible as a whole.

Cultural linkages: Deep integration of symbols, aesthetics, and beliefs. Cultural linkages confer the deepest meanings on the space: the great rock in the water acquires the aesthetic image of a soaring dragon, the break in the reef, marked by the ‘Longmen’ inscription, symbolizes ascent/transcendence, and the water eddies current composes the poetic image of ‘Longmen Haoyue.’ From Song-era carvings and Qing-era steles to the myth of Tushan’s landing, historical sedimentations and aesthetic imagination interact to foster local beliefs seeking safe passage and felicitous life. Thus, rock-face carvings and the notion of responsive efficacy (‘prayers answered’) effect a value sublimation, from physical space to a cultural sanctuary, leaving an indelible cultural imprint.

4.2. Analytical Findings: Field-Surveyed Damage and Risk to Landscape Elements

Field investigation and historical contextualization reveal that the area faces severe challenges stemming from damage, misreading, and inappropriate reconstruction during modernization. These are parsed across anchor, characteristic, and general elements, and across physical carriers and cultural connotations.

Physical erosion and spatial isolation of anchor/general elements have broken material continuity. The core anchor, the Longmenhao reef, though not erased, is fragmented by blasting and engineering works. Modern infrastructure (e.g., the riverside expressway and high revetment walls) creates physical and visual barriers that sever the public’s original connection to the reef and the Yangtze River. Damage to connecting facilities (e.g., stairs) has sharply reduced spatial accessibility, turning the historic landscape into a ‘natural and cultural island.’ Such isolation not only impedes the experience of, but also accelerates, the erosion of collective memory.

Misreading of the characteristic element signals a transmission crisis for the core cultural symbol and scrambles the cultural thread. The emblematic characteristic element is ‘Longmen Haoyue,’ whose core lies in the dynamic hydromorphology: when flow strikes the reef (hao, the port), a vortex forms (yue, moon-like). Yet contemporary promotion often misreads this as ‘Longmen Haoyue → Longmen Haoyue (龙门浩月 → 龙门皓月, share the same pronunciation)’, shifting from the river’s turbulence (浩) to the paleness of moonlight (皓). This one-character substitution detaches the symbol from its geohydrological basis, marginalizing the reef, the cultural source, and propagating a generalized imagery that destabilizes the transmission system.

After the disappearance of general elements has led to authenticity loss and the ‘hollowing-out’ of meaning. Two mechanisms are salient: (1) Symbol relocation and decontextualization, e.g., a ‘Longmenhao’ sculpture erected kilometers away from the original landscape, extracts the hao signifier from the Yangtze River shipping culture, port function, and natural setting that sustain it, reducing the anchor to a context-free signifier and risking cultural hollowing, (2) Spectacular visual overrides and narrative rewriting —the Dongshuimen Bridge and transiting light rail, as modern megastructures, impose visual hegemony, restructuring the area’s perceptual hierarchy. Visitors photographing the so-called ‘Shenguishi’ (Divine Turtle Rock) are no longer engaging with historical meaning but consuming a post-modern urban spectacle. The deep historical thread is downgraded to decor, and authenticity shifts from a physically and historically continuous presence to a marketable cultural sign.

In sum, the integrity crisis at Longmenhao is a multidimensional, cascading one (Figure 9) that originates in physical damage and isolation, aggravated by cultural misreading and symbol substitution, and culminates, under the logic of urbanization, in the dissolution of authenticity and the hollowing of cultural meaning. The trajectory demonstrates how, amid rapid development, an organic whole uniting aesthetics, production, and belief can devolve into isolated, fragmented, and misinterpreted cultural shards.

Figure 9.

The challenges of Longmenhao’s historical relics in preservation.

4.3. Evaluation Results: Value Assessment of Longmen Haoyue’s Landscape Elements

Building on identification and analysis, we applied a fuzzy analytic method to quantify key landscape elements within Longmenhao, thereby supporting scientific and orderly strategies for conservation and renewal. Using the established indicator system, we evaluated protection hierarchies for Longmen Haoyue.

From the five-expert fuzzy complementary judgment matrix, the computed weights for different factors (Table 2) range from 0.0441 to 0.0563. A2 (anchor element) ranks first at 0.0563, B2 (place name and geographic location) follows at 0.0537. A1 (spatial boundaries and pattern) and C3 (visual/sightline connectivity) place third and fourth at 0.0540 and 0.0535, respectively. B1 (historical fabric), D1 (integration with urban cultural context), C1 (integration with the built urban environment), B3 (cultural narratives), and D2 (landscape aesthetics) all exceed 0.05, with close values. Remaining factors, C2 (natural geology/landform and hydrological context), D3 (spiritual beliefs/religious significance), D5 (symbolic meaning), D4 (events and collective memory), B4 (continuity of function), E3 (recreational and economic functions), E1 (ecosystem service functions), E2 (production and livelihood functions), E4 (cultural transmission and educational functions), and A3 (characteristic elements), are all < 0.05, with A3 being the lowest at 0.0441.

Table 2.

Computed weights for Longmen Haoyue.

Consistency testing of the judgment matrix ensures the logical reliability of expert input (Table 3), the compatibility ratio is CR ≈ 0.0704, which is within the acceptable threshold. The fuzzy hierarchical analysis yields:

Table 3.

Computed principal eigenvector from the FAHP matrix for Longmen Haoyue.

- Even weight distribution. The narrow spread (0.0122) indicates no dominant single factor; the system reflects comprehensiveness and nuance.

- Spatial armature and anchor element as physical foundations. A2 (anchor element, i.e., the reef) holds the highest weight (0.0563), underscoring the primacy of material conservation for maintaining historical memory and spatial identity. A1 (spatial boundaries and pattern, 0.0540) highlights the importance of overall spatial form, scale, and structure. Preserving the historic spatial fabric is foundational, because without it, other cultural and spiritual values cannot be effectively expressed.

- Historical–cultural value as the core ‘soul.’ Elevated weights for B2 (0.0537) and B1 (0.0526) emphasize the criticality of place name, geographic location, and historical fabric. The D-class (cultural relationality) factors occupy mid-to-upper ranks with comparable weights, indicating that Longmenhao bears deep spiritual and cultural connotations, cultural lineage, aesthetics, belief, and historical events beyond its material shell. Hence, conservation must safeguard cultural memory and symbolic meaning, not merely buildings.

- Environmental integration matters. C3 (0.0535) and C1 (0.0510) show that visual connectivity, e.g., with Longmenhao’s surrounding accent buildings and Nanshan, and integration with the contemporary built environment are pivotal. Maintaining open-view corridors and avoiding blocking structures (e.g., high revetments along the Yangtze River) are key. Integration with the urban fabric argues for enhanced accessibility and active presence, not an isolated ‘museum piece.’ Conservation thus requires a macro-scale perspective harmonizing historic districts with natural settings and modern cityscapes.

- Lower E-class weights do not imply irrelevance. While functional relationality (E-class) ranks the lowest, this reflects expert judgment that Longmenhao’s core value lies in its historical, cultural, spiritual, and spatial qualities rather than present-day functions. Function serves as a vehicle for conservation, not its ultimate goal. Any new functions (e.g., commerce, tourism, cultural creativity, etc.) must be contingent upon and reinforcing of historical and cultural integrity.

In summary, the weighting analysis clarifies a conservation stance: stabilize spatial pattern and physical fabric first, place in the foreground historical-cultural and spiritual-symbolic values, and coordinate integration with surrounding natural and modern urban environments, then achieve sustainable district vitality through appropriate functional activation.

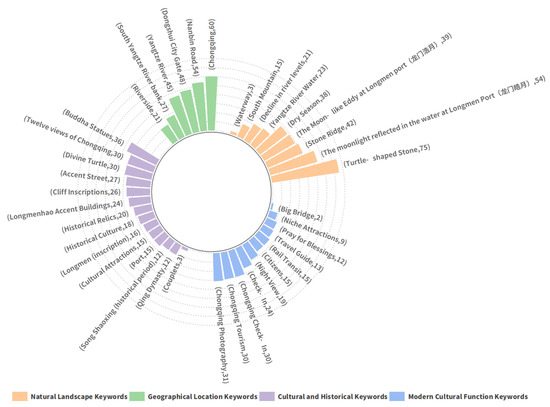

4.4. Overall Cognition: Online Evaluations and Public Perception of Longmen Haoyue

As one of the historic ‘Twelve Views of Ba-Yu’, Longmen Haoyue is undergoing a profound reversal of cultural meaning and a crisis of authenticity, not from a single cause, but from the interplay of digital-media dissemination, public cognition, and contemporary physical conditions. Using keyword frequency (top 40, Figure 10) from multiple platforms, we observe:

Figure 10.

Word frequency analysis of the first 40 terms in Longmenhao’s evaluation.

- Surface symptoms in word frequencies: loss of core characteristics and landscape homogenization. The symbolic substitution now prevalent online signals a two-way cognitive dislocation between the natural and cultural dimensions. Historically, the Moon-like Eddy provided a distinct identity, and its disappearance promotes a generic ‘check-in landscape.’ The clearest expression of this is the shift toward ‘Shenguishi’ (Divine Turtle Rock), appearing 75 times, crowding out the historical toponym. The parallel confusion between ‘Longmen Hao yue’ (浩) and ‘Longmen Hao yue’ (皓) is telling: the drift from hydrologically grounded ‘hao’ (浩, 39 mentions) to moon-whiteness ‘hao’ (浩, 54 mentions) charts a slide from a place-specific hydrological image to a placeless scenic cliché, suspending the cultural core.

- From holistic understanding to fragmentation under a touristic-commercial narrative. High-frequency tokens like ‘check-in’ and ‘tourism’ outnumber ‘historical culture’ and ‘historic site,’ indicating domination by a consumptive, fast-food tourism discourse, a process of decontextualization that strips aesthetic and symbolic depth. The composite landscape once comprising 12 elements is reduced to isolated items (e.g., ‘Shenguishi’ and ‘Old Street’) lacking an overarching narrative.

- Hegemony of new urban spectacles over heritage. Modern mega-infrastructure, emblematically the Dongshuimen Bridge, asserts functional and visual dominance, re-ranking the landscape. The pre-existing historical thread and cultural carriers (e.g., cliff inscriptions) are spatially and perceptually marginalized, becoming mere backdrops to engineering works. This is a textbook case of cultural-landscape overwriting, whereby a new, forceful urban text overlays an older, fragile heritage. Longmen Haoyue thus faces not only symbolic cognitive challenges but also the loss of status as a visual and cultural focal point in physical space.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Anchored in the holistic–relational theory, this study develops an analysis and evaluation approach tailored to historic Urban Eight Views and conducts a systematic empirical test using Longmen Haoyue in Chongqing. The framework departs from boundary- and object-centered routines by emphasizing full-spectrum element identification and the reconstruction of multidimensional linkages, with the aim of safeguarding structural integrity, semantic authenticity, and functional continuity in a dynamic urban context. Methodologically, we introduce a three-tier element model, anchor, characteristic, general, and a three-aspect relational mechanism, spatial, functional, cultural, which together provide clear logic and tools for identifying, assessing, and repairing Eight-Views-type heritage. Because the value of the Eight Views resides not only in discrete material remains but, more profoundly, in the network of meanings woven by interactions among elements, effective conservation must protect the ‘points’ (elements) while repairing the ‘lines’ (relations) so as to reconstitute the ‘plane’ (overall atmosphere/setting).

5.1. Theoretical Contribution to Conservation

This research advances an operational methodology specific to China’s historic Urban Eight Views: a three-level classification of elements (anchor, characteristic, general) and a triadic relational schema (spatial, functional, cultural). The framework supplies a coherent logic and toolset for the identification, evaluation, and repair of analogous landscape heritage. For Eight Views heritage that stresses holistic ambience and cultural narrative, value does not lie solely in isolated material remains but in the web of meaning formed by inter-element linkages. Once this web is severed, the heritage’s integrity and authenticity come into question. Our theoretical innovation therefore offers a systemic mindset to break the impasse of fragmentary protection: only by maintaining both the ‘points’ (elements) and the ‘lines’ (relations) can we truly safeguard the ‘plane’ (overall ambience).

5.2. Case Validation: Applicability and Effectiveness of the Framework

Empirical identification of loss and contextual rupture refers to a source-based, field-verified assessment that quantifies vanished or altered elements and traces the breakdown of their spatial, functional, and narrative linkages over time. Through historical-document analysis and field surveys, we identified 14 historical elements for Longmen Haoyue, of which only 8 persist today, quantitatively demonstrating severe material loss and contextual rupture. This underscores the necessity of holistic identification in Eight Views conservation: focusing only on surviving elements underestimates the richness of the original ensemble and obscures how today’s incompleteness emerged. The framework compels a panoramic view of heritage evolution and thereby sharpens subsequent protective targeting.

The FAHP shows that experts assign the highest weights to anchor element (e.g., the Longmenhao reef, 0.0563) and spatial pattern (0.0540), confirming the foundational role of material carriers in the generation, endurance of cultural meaning, and the urgency of restoring overall spatial structure. Meanwhile, semantic factors, place name and geographic location (B2, 0.0537), historical fabric (B1, 0.0526), and cultural narratives (B3, 0.0510), all exceed 0.05, indicating broad expert endorsement that material preservation without cultural context is incomplete preservation. These results accord with our theoretical expectation: holistic elements and relational context are equally indispensable.

The study further uncovers a deep-seated crisis that is often overlooked by traditional methods, namely semantic drift and symbol substitution, e.g., misreading hydrologically grounded Hao (浩) as moonlight-oriented Hao (皓), or replacing the Longmen Haoyue imagery with consumerist labels such as ‘Divine Turtle Rock.’ Such shifts hollow out cultural connotations, blur identity, and sever essential ties to local history, geography, and ecology. This recognition widens the scope of heritage risk assessment: protection must address not only visible materiality but also the invisible erosion of meaning. The case thereby verifies that the holistic—relational framework can diagnose and quantify overt problems (e.g., fragmentation and insularization) while also revealing latent semantic ruptures, enriching comprehensive heritage health diagnostics.

5.3. Conservation Strategies and Toolkit

Translating the holistic–relational framework into site-specific actions, we structure interventions across multiple layers. At the physical-spatial level, priority is placed on repairing anchor elements and re-establishing key spatial linkages. For Longmen Haoyue, interventions should include engineering stabilization and targeted restoration of the reef remains, sediment clearance near bridge piers to re-expose segments of the reef, redesign of revetments and planting to open historic view corridors, allowing the Old Street once again to ‘see’ the mid-channel reef and river scenery, and the opening of waterside promenades/viewing platforms to restore public accessibility and dissolve the site’s physical island condition. Together these measures counter fragmentation and insularization and re-knit the physical armature.

At the cultural-interpretive layer, we advance a semantics-repair strategy that targets symbolic misreading and gaps, restoring the intended meanings embedded in names, narratives, and practices. Prioritize public communication that correctly explicates ‘Haoyue (浩月)’ and rectifies the ‘Haoyue (皓月)’ misusage, highlighting Longmenhao’s unique hydromorphological phenomenon. Install interactive interpretation on the Old Street or riverfront (e.g., water/lighting devices simulating the vortex) so visitors can intuitively comprehend the original Moon-like Eddy. Clearly mark associated nodes such as Wanglongmen (‘Viewing the Dragon Gate’) and narrate their relationships with Longmen Haoyue, ensuring visitors do not know only the ‘Divine Turtle Rock’ while remaining ignorant of Haoyue. Such measures will re-knit the broken semantic chain and restore the heritage’s intangible values.

Functional activation layer: embed low-intensity cultural services for balanced ‘activation-protection.’ Through restrained programmatic insertion and placemaking, transform the historic landscape from a static relic into an engageable cultural milieu attuned to its historic context. Strengthen public participation (e.g., festivals, cultural experiences, and educational initiatives) to revive historical imagery and elicit cognitive–emotional resonance, embedding transmission in everyday community life rather than confining it to scholarship. Through careful programming and stewardship, facilitate the shift from ‘static relic’ to ‘living heritage,’ serving leisure and tourism while maintaining continuity and authenticity of cultural memory.

6. Discussion

6.1. A Theoretical Turn in Heritage: From Object Protection to Relational Networks

This study employs a holistic–relational approach to argue that the value of Eight Views urban heritage is not embedded in isolated material remains but is generated and sustained within a multidimensional network of relations among elements and between elements and their environment. Accordingly, the logic of heritage conservation needs to shift from the traditional object-centered paradigm to more systemic network-centered and context-centered orientations. This stance aligns closely with UNESCO’s Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) Recommendation, which advocates for the integrated coordination of the built environment with its social, economic, and cultural contexts, and it may be regarded as an attempt to operationalize the HUL framework in small-scale cases characterized by complex temporal discontinuities [36,46,94]. By constructing an analytical method combining three categories of elements, anchor, signature, and general, with three dimensions, spatial, functional, and cultural, the study translates the abstract notion of wholeness into identifiable element inventories and mappable relation diagrams, effectively remedying blind spots in semantic and relational dimensions within traditional ‘boundary delineation-setback control’ protection approaches [31,33].

6.2. Material Skeleton, Relational Network, and Semantic Authenticity: An Empirical Basis for Reconstructing Urban-Heritage Wholeness

The FAHP results indicate that ‘anchor elements’ and ‘spatial boundaries and pattern’ carry the highest weights (0.0563 and 0.0540), suggesting that overall integrity is first grounded in the material and spatial skeleton on which cultural narratives and functional revitalization depend; this echoes the international heritage discourse that couples ‘integrity’ with ‘authenticity,’ wherein material continuity is the necessary precondition for the conveyance of spiritual values [21,22,23,24,25]. However, the signature element of Longmenhao, namely the eddy-forming hydrological phenomenon that produced the ‘moon’ image, has nearly disappeared; even with anchor elements remaining, the overall ambience is difficult to restore, underscoring the decisive role of key landscape attributes in the heritage’s recognizability and legibility. This finding supports recent discussions on the centrality of ‘key attributes’; scientifically reconstructing, rather than inventing, critical attributes is a necessary pathway to restoring wholeness [7,8,9,10].

Across relational dimensions, indicators such as ‘visual/sightline connectivity,’ ‘integration with the built urban environment,’ and ‘integration with urban cultural context’ also receive high weights (≥0.051), indicating that repairing fragmentation cannot rely solely on object-level restoration or buffer zoning; it must concurrently rebuild the ‘visible lines’ (e.g., lines of sight and accessibility) and the ‘invisible lines’ (e.g., stories, toponyms, and rituals) to restore the chain of meanings that runs from viewing practices to symbolic belief. These results are highly consistent with the HUL’s call for ‘full-spectrum integration’ [36], which emphasizes the coupling between attributes, narratives, and structures.

Multisource corpus analysis further reveals a long-overlooked heritage risk: semantic drift and symbolic substitution. ‘Hao-yue’ is widely misread, and its scenic imagery has been replaced by later click-driven symbols such as ‘Tortoise Rock’; coupled with off-site replicas and decontextualized displays, these changes exacerbate cognitive misalignment. This indicates that the semantic system is not ancillary to value but constitutes the core mechanism through which value is generated and transmitted. Semantic drift, symbolic substitution, and decontextualization should be treated as novel risks and incorporated into monitoring systems alongside physical pathologies. Particularly in contemporary cities, newly built megastructures can, through ‘visual hegemony,’ overwrite historical narratives and reduce them to mere backdrops for spectacular consumption. This phenomenon expands the connotation of ‘authenticity’: authenticity concerns not only materials, techniques, and layout but also the correct alignment between words, imagery, narratives, and place [5,6].

In addition, expert evaluations focus on spatial configuration and contextual integrity, whereas public corpora display a check-in-oriented and fragmentary consumption logic; although discrepant, the two are complementary. Public feedback can expose representational gaps in perceptibility and communicability, providing a pragmatic basis for exhibition design; expert judgment helps correct value misalignments and prevents ‘popularity supplanting cultural significance.’ This divergence suggests that heritage interpretation should seek a balance between professional depth and public accessibility.

6.3. From ‘Repairing Objects’ to ‘Repairing Networks’: A Relation-Oriented Governance Framework and Implementation Pathways

Building on the empirical findings of Section 6.2, this study proposes a systemic governance pathway to shift the protection of Eight-Views-type heritage from ‘repairing objects’ to ‘repairing networks.’ The ‘value web’ of Eight Views heritage is woven by ‘points’ (elements) and ‘lines’ (relations); under the joint effects of erosion of the material–spatial skeleton, the fading of signature attributes, and drift in the semantic system, the rupture of wholeness, the hollowing-out of authenticity, and the fragmentation of cognition reinforce one another. Accordingly, the study constructs and validates an operational matrix of anchor–signature–general × spatial–functional–cultural together with an FAHP-based weighting framework, enabling simultaneous identification of priorities for material repair and directions for semantic-relational restoration.

At the theoretical level, the study adds operational steps to the HUL approach for small-scale cases, forming a closed-loop toolkit of ‘element identification, relation mapping, weight prioritization, and semantic restoration’ [42,43]; at the same time, it conceptualizes the semantic misalignment revealed in Section 6.2 as ‘semantic risk,’ arguing for the inclusion of mismatches among words, images, place-names, and locations as a new dimension in assessments of integrity and authenticity [25], thereby expanding the scope of heritage risk monitoring.

At the practical level, it recommends a tripartite collaborative governance mechanism of expert calibration, public co-creation, dynamic monitoring. The expert system secures anchor elements and spatial configuration to ensure interpretive accuracy; public participation optimizes interpretive systems and everyday embedding to enhance perceptibility and communicability, and dynamic monitoring addresses compound risks such as physical degradation and semantic drift.

Concrete steps include prioritizing the repair of anchor elements such as the stone beam and the overall spatial configuration, concurrently re-establishing sightline corridors and waterfront accessibility, undertaking narrative reconstruction centered on the hydrological mechanism of ‘Hao (moon)’ to avoid the erroneous generalization of ‘Hao-yue’ into ‘bright moon (皓月)’ imaginations, and creating perceptible dynamic re-enactment settings through reversible, low-interventional means. Ultimately, requirements such as view-corridor control, the restoration of historical toponyms, and the insertion of narrative nodes should be incorporated into statutory instruments such as regulatory detailed plans and cultural environmental impact assessments, so as to secure systemic safeguarding and living continuity of heritage values in contemporary cities.

6.4. Limitations and Future Directions

This study centers on a single case, ‘Longmen Haoyue’ in Chongqing, China; although typical and representative as one of the Bayu Twelve Views, the inherent limitations of a case study mean that the external validity of the findings remains to be tested. Future work may extend the analytical framework to the entire set of Bayu Twelve Views and, through systematic comparison across the twelve heritage landscapes, explore in depth the method’s transferability and limits of applicability under different geographical, historical, and urban contexts, thereby strengthening the theory’s generalizability and explanatory power. Moreover, the expert consultation sample is small (n = 5); although the experts possess relevant domain experience, the robustness of the weighting results should be validated by enlarging the expert pool and conducting sensitivity analyses. Regarding public perception data, the current corpus is drawn primarily from social media platforms and influenced by algorithmic recommendation mechanisms and user composition, is biased toward younger groups, potentially failing to fully reflect the perceptions and value judgments of older residents, long-standing local communities, and specialist cultural tourists. Future research should improve the representativeness and inclusiveness of public-participation data through multisource data integration and stratified sampling strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: H.M. and W.X.; Data curation: W.X.; Formal analysis: W.X. and J.F.; Funding acquisition: H.M.; Investigation: W.X.; Methodology: W.X.; Validation: W.X. and J.F.; Writing—Original Draft: W.X. and J.F.; Writing—review and editing: W.X., J.F. and R.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 5237082015); Major Program of National Social Science Foundation of Chongqing (Grant No. 2023ZD08); Chongqing University Graduate Student Research Innovation Project (Grant No. CYB240033).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Shiga. Eight Views of Omi: Overview. 2020. Available online: https://www.mlit.go.jp/tagengo-db/zhTW/R2-01402.html (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Tang, Y. Xunyang Eight Views Handscroll (Silk). 1515. Available online: http://xn--vcsu3i05le6a3dq38n.com/digital/1027.htm (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Harunobu, S. Eight Views of Omi. 1760. Available online: https://www.benricho.org/Unchiku/Ukiyoe_NIshikie/Harunobu_Omihakkei/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- United Nations. UN Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes Zancheti, S.; Piccolo Loretto, R. Dynamic integrity: A concept to historic urban landscape. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 5, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen-zhuo, Z.; Feng, H. A review of the theoretical and practical research on historic urban landscape. Landsc. Archit. 2017, 24, 22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Immonen, V. Urban heritage, and the theory of fragmentation: The development of archaeology in the City of Turku, Finland. Herit. Soc. 2024, 17, 346–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D. On phenomena of urban heritage being Islanded in west historic cities. Urban Plan. Forum. 2005, 4, 56–59. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Martínez, P.G. Heritage, values and gentrification: The redevelopment of historic areas in China. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2022, 28, 476–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yutian, L.; Xu, S.; Liu, S.; Wu, J. An approach to urban landscape character assessment: Linking urban big data and machine learning. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 83, 103983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antrop, M. Why landscapes of the past are important for the future. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2005, 70, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Pino, J. The new holistic paradigm and the sustainability of historic cities in Spain: An approach based on the world heritage cities. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripp, M.; Rodwell, D. The governance of urban heritage. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2016, 7, 81–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragheb, A.; Aly, R.; Ahmed, G. Toward sustainable urban development of historical cities: Case study of Fouh City, Egypt. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2022, 13, 101520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höftberger, K. Conservation and development: Implementation of the historic urban landscape approach in Khiva, Uzbekistan. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2023, 29, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muminović, E.; Radosavljević, U.; Beganović, D. Strategic planning and management model for the regeneration of historic urban landscapes: The case of historic center of Novi Pazar in Serbia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olegovich Anisimov, I.; Evgenyevna Gulyaeva, E. The common heritage of mankind and the world heritage: Correlation of concepts. Novos Estudos Juridicos. 2022, 27, 282–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Bastawissi Raslan, R.; Mohsen, H.; Zeayter, H. Conservation of Beirut’s Urban Heritage Values Through the Historic Urban Landscape Approach. Urban Planing. 2022, 7, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Esparza, J.A. Are World Heritage concepts of integrity and authenticity lacking in dynamism? A critical approach to Mediterranean autotopic landscapes. Landsc. Res. 2018, 43, 817–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, P. Assessing the sustainable development of the historic urban landscape through local indicators. Lessons A Mex. World Herit. City. J. Cult. Herit. 2020, 46, 320–327. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, R.; Nasu, S. Adopting the ‘historic layering’concept from the Historic Urban Landscape approach as a methodological framework for urban heritage conservation. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2025, 31, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginzarly, M.; Houbart, C.; Teller, J. The Historic Urban Landscape approach to urban management: A systematic review. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2019, 25, 999–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ren, Y.; Lv, J.; Geng, Y.; Su, C.; Ma, R. Morphological Evolution and Socio-Cultural Transformation in Historic Urban Areas: A Historic Urban Landscape Approach from Luoyang, China. Buildings 2025, 15, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintossi, N.; Kaya, D.I.; Roders, A.P. Identifying challenges and solutions in cultural heritage adaptive reuse through the historic urban landscape approach in Amsterdam. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, J.; Luiten, E.; Renes, H.; Stegmeijer, E. Heritage as sector, factor and vector: Conceptualizing the shifting relationship between heritage management and spatial planning. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2017, 25, 1654–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokilehto, J. A History of Architectural Conservation, Butterworth Heinemann. In European Journal of Archaeology; Cambridge University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999; p. 292. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L. Uses of Heritage; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Page, S. A Geography of Heritage: Power, Culture and Economy; Brian Graham, G.J., Ashworth, J.E., Eds.; Wiley Online Library: Tunbridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, R. Heritage: Critical Approaches; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, T.C.; Muhar, A.; Arnberger, A.; Aznar, O.; Boyd, J.W.; Chan, K.M.A.; Costanza, R.; Elmqvist, T.; Flint, C.G.; Gobster, P.H.; et al. Contributions of cultural services to the ecosystem services agenda. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 8812–8819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudor, C. An approach to landscape character assessment. Nat. Engl. 2014, 65, 101716. [Google Scholar]

- Martín, B.; Ortega, E.; Otero, I.; Arce, R.M. Landscape character assessment with GIS using map-based indicators and photographs in the relationship between landscape and roads. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 180, 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, A.; Åkerskog, A. Awareness-raising of landscape in practice. An analysis of Landscape Character Assessments in England. Land Use Policy 2014, 36, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandarin, F.; Van Oers, R. Reconnecting the City: The Historic Urban Landscape Approach and the Future of Urban Heritage; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape. 2011. Available online: https://unterm.un.org/unterm2/en/view/unesco/c6cb9aaf-d73e-4c91-9824-d6b5b8373606 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Yang, X.; Shen, J. Integrating historic landscape characterization for historic district assessment through multi-source data: A case study from Hangzhou, China. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey-Perez, J.; Siguencia Ávila, M.E. Historic urban landscape: An approach for sustainable management in Cuenca (Ecuador). J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 7, 308–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfantini, G.B. Historic urbanscapes for tomorrow, two Italian cases: Genoa and Bologna. Eur. Spat. Res. Policy 2015, 22, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldpaus, L.; Pereira Roders, A.R.; Colenbrander, B.J. Urban heritage: Putting the past into the future. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2013, 4, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, S. Historic Landscape Characterisation: A landscape archaeology for research, management and planning. Landsc. Res. 2006, 31, 385–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, S. Historic landscape characterisation: An archaeological approach to landscape heritage. In Routledge Handbook of Landscape Character Assessment; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2018; pp. 37–50. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, G.; Lambrick, G.; Hopkins, D. Historic landscape characterisation in England and a Hampshire case study. In Europe’s Cultural Landscape: Archaeologists and the Management of Change; European Association of Archaeologists: Oxford, UK, 2002; pp. 69–83. [Google Scholar]

- Aldred, O.; Fairclough, G. Historic Landscape Characterisation: Taking Stock of the Method; English Heritage/Somerset County Council: London, UK, 2003.

- Conzen, M.R.G. Alnwick, Northumberland: A Study in Town-Plan Analysis; Transactions and Papers (Institute of British Geographers): London, UK, 1960; pp. iii–122. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Bandarin, F.; Van Oers, R. The Historic Urban Landscape: Managing Heritage in an Urban Century; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, B.; Ashworth, G.; Tunbridge, J. A Geography of Heritage; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bill, H.; Julienne, H. The Social Logic of Space; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Benedikt, M.L. To take hold of space: Isovists and isovist fields. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 1979, 6, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanwick, C.; Heritage, S.N. Landscape Character Assessment: Guidance for England and Scotland. Making Sense of Place; Countryside Agency: Cheltenham, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Ovo, M.; Dell’anna, F.; Simonelli, R.; Sdino, L. Enhancing the cultural heritage through adaptive reuse. A Multicriteria Approach Eval. Castello Visconteo Cusago (Italy). Sustainability 2021, 13, 4440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, L.; Huang, J.; Law, A. Research frameworks, methodologies, and assessment methods concerning the adaptive reuse of architectural heritage: A review. Built Herit. 2021, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enfield, N. Legibility in culture. Anthropol. Theory 2025, 14634996251338486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A.; Matulewska, A.; Le, C. Protection, regulation and identity of cultural heritage: From sign-meaning to cultural mediation. Int. J. Semiot. Law-Rev. Int. De Sémiotique Jurid. 2021, 34, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labadi, S.; Giliberto, F.; Rosetti, I.; Shetabi, L.; Yildirim, E. Heritage and the sustainable development goals: Policy guidance for heritage and development actors. ICOMOS 2021, OAI ID: oai:eprints.whiterose.ac.uk:185242. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J.; Zhou, T.; Han, Y.; Ikebe, K. Urban heritage conservation and modern urban development from the perspective of the historic urban landscape approach: A case study of Suzhou. Land 2022, 11, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Gu, K. Pingyao: The historic urban landscape and planning for heritage-led urban changes. Cities 2020, 97, 102489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, K.; Cooke, S.; Fayad, S. Using the historic urban landscape to re-imagine ballarat: The local context. In Urban Heritage, Development and Sustainability; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2015; pp. 93–113. [Google Scholar]

- Cunha Ferreira, T.; Rey-Pérez, J.; Roders, A.P.; Silva, A.T.; Coimbra, I.; Vazquez, I.B. The historic urban landscape approach and the governance of world heritage in urban contexts: Reflections from three European cities. Land 2023, 12, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E. The County Gazetteer of Baxian (Qianlong Period); The Office of the County Magistrate of Ba County: Chongqing, China, 1761; Volume 1, pp. 1–142. [Google Scholar]

- Military Affairs Commission, G.S.H.; Fourth Department. Street Map of Chongqing Urban District; Chongqing, China, 1946. Available online: https://www.ditu114.com/ditu/750.html (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Swire, G.W. Chungking c.1920. Available online: https://www.hpcbristol.sjtu.edu.cn/visual/Sw19-062 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Forman, H. Harrison Forman’s China Photographic Collection. 1940–1943 (Chongqing). Available online: https://www.shuge.org/view/harrison_forman_collection/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Fangcan, Y. General Gazetteer of Sichuan; The Office for Compiling the Collected Statutes: Chengdu, China, 1816; Volume 11, pp. 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Yaojian, Y. Chronicles of Chongqing’s Trade Wharves. In Chongqing Daily; Chongqing Daily Newspaper Group: Chongqing, China, 2025; Available online: https://wap.cqrb.cn/xcq/NewsDetail?classId=1968&newsId=2139575. (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Website, C.M.P.s.G. [Chongqing Toponyms] Bridges—Dongshuimen Yangtze River Bridge. 2024. Available online: https://dfz.cq.gov.cn/zqlswh/rwby_417819/202406/t20240605_13267997.html (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Yi, H. Chongqing: Telling the “Yangtze River Culture” Story Well in the New Era; Chongqing Daily: Chongqing, China, 2022; Available online: https://www.cqrb.cn/content/2022-01/10/content_359472.htm (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Mısırlısoy, D.; Günçe, K. Adaptive reuse strategies for heritage buildings: A holistic approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2016, 26, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, C. A Holistic Approach to Valuing Our Culture; Department for Culture Media and Sport: London, UK, 2013.

- Rudolff, B. Intangible and Tangible Heritage; UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Vecco, M. A definition of cultural heritage: From the tangible to the intangible. J. Cult. Herit. 2010, 11, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, A.P. Values and relationships between tangible and intangible dimensions of heritage places. In Values in Heritage Management: Emerging Approaches And Research Directions; Getty Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2019; Volume 12, pp. 172–185. [Google Scholar]

- Pocock, C.; Collett, D.; Baulch, L. Assessing stories before sites: Identifying the tangible from the intangible. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2015, 21, 962–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stilling, S.; Braae, E. Relational heritage: ‘relational character’ in national cultural heritage characterisation tools. Landsc. Res. 2023, 48, 917–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D.C. Heritage and scale: Settings, boundaries and relations. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2015, 21, 577–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, M.; Meijers, E. Form follows function? Linking morphological and functional polycentricity. Urban Stud. 2012, 49, 1127–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]