Abstract

In the last 30 years, considerable effort has been invested in the public presentation of archaeological sites and, in general, in the dissemination of the heritage bequeathed to us by the pre-Roman communities of the western Iberian Peninsula. In this paper, we critically analyse the most outstanding measures implemented in this area by the different administrations and specialists involved. Similarly, we present the main initiatives undertaken in this regard in recent years by our research team within the framework of the REFIT and VETTONIA projects. Finally, we put forward ten essential proposals for future actions to achieve a more effective dissemination and management of Iron Age heritage.

1. Introduction

The last twenty-five years of archaeological research on the Iberian Peninsula have significantly increased our knowledge of the large settlements or oppida [1]. It is not in vain that they are said to represent the first urbanism in Temperate Europe. However, despite their importance in the European past, oppida are poorly identified and scarcely recognised as the foci for the cultural and economic development of the regions in which they emerged [2,3]. Their size has led them to be considered “archaeological sites” and, at the same time, “cultural landscapes”, which implies an enormous challenge for their management and dissemination [4]. To some extent, they represent a microcosm of the challenges we face every day in defending these fragile and exceptional places, created from people’s lives, perceptions, beliefs, etc. Therefore, they are fundamental for us to be able to understand the feelings of identity of those people [5] (p. 76).

Oppida were large, occupying tens and even hundreds of hectares. They were usually highly visible, thanks to their monumental structures, such as walls and ditches, and their location in conspicuous places. Furthermore, their remains are usually set in landscapes of great natural beauty. Therefore, they seem ideal for introducing the general public to historical knowledge and an appreciation of archaeological heritage and nature. However, as Sommer [6] (p. 167) rightly points out, these apparent advantages can turn into disadvantages, because, among other factors, the large size of the sites sometimes makes it difficult for the non-expert visitor to interpret the remains and the different visitable structures that may be excessively dispersed. Likewise, their location in exceptional landscapes, in some cases protected, can greatly hinder accessibility and, thus, the visitor experience.

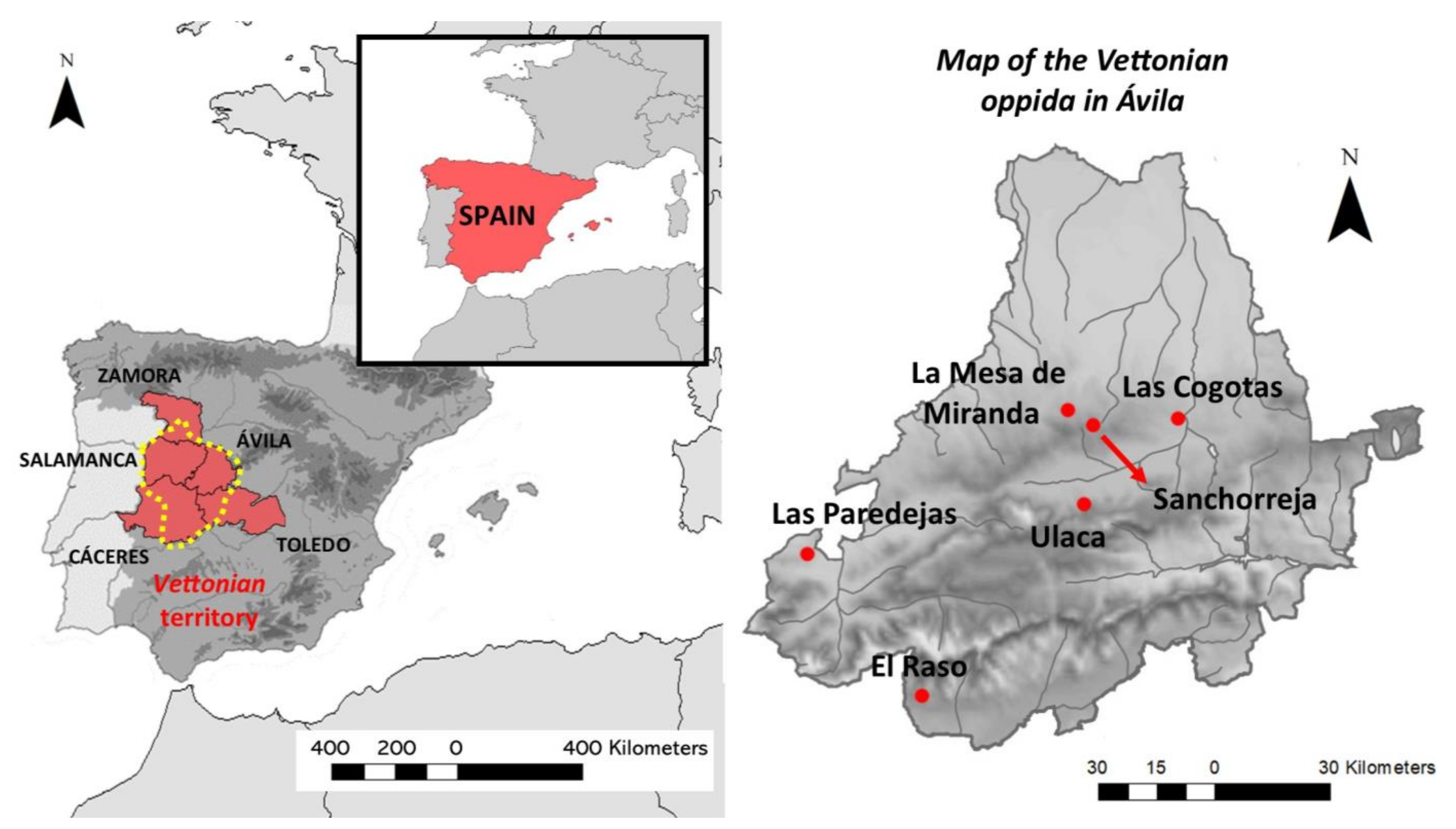

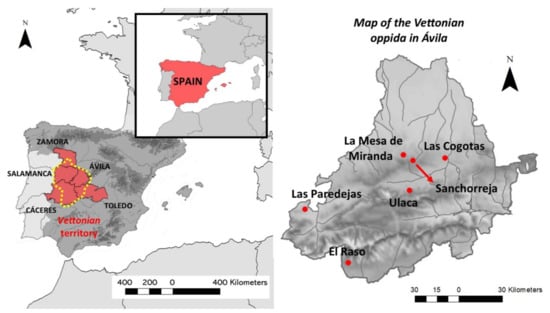

In our case, the people who lived in western Iberia during the Iron Age left an enormous material imprint that is particularly important in the province of Ávila (Figure 1). In this area, we have large fortified towns that are much more visible than the farms and villages that must have undoubtedly existed as well. There are also ritual sites with a certain monumentality [7] (p. 64). They include rock sanctuaries, initiation saunas, burial mounds and stelae used in cremation cemeteries. There are also verracos, large stone sculptures of bulls or boars that signposted and protected the pastures and settlements of the western Iberian Peninsula, a phenomenon unparalleled in Temperate Europe at the time [8,9,10]. The visibility of the ancient verracos extends into recent history, from the 15th century to the present day. Once they had lost their original meaning, in some cases, they were reused or moved to decorate houses, palaces and, more recently, town squares (Figure 2) [11].

Figure 1.

Location of the main Iron Age sites in the province of Ávila (Central Spain).

Figure 2.

Pre-Roman bull in Villanueva del Campillo (Ávila), currently in the town square.

One very important aspect is the activities of the archaeologists and managers, as well as those of the organisations in charge of protecting and disseminating heritage and the local and regional administrations. Archaeological remains may or may not be visible, but public interest is ultimately essential for them to be appreciated, interpreted and disseminated [12,13,14]. There is a long history of research into the oppida of the western Iberian Peninsula. The first descriptions date back to the 19th century, although no exhaustive studies were carried out until the end of the 1920s and the 1930s, when the oppida of Las Cogotas (Cardeñosa, Ávila) and La Mesa de Miranda (Chamartín, Ávila) and their respective cemeteries were excavated [15,16,17]. The remains revealed at that time were identified as belonging to the pre-Roman Vettones. Almost six decades had to pass after Juan Cabré’s pioneering studies until the emergence of the first programmes for the reconstruction and dissemination of the Vetton culture. This was brought about in part by an increasing demand for cultural tourism and, more specifically, the so-called archaeotourism [18,19,20].

In this article, we will briefly review the main measures undertaken in recent decades by the administration and the various specialists to disseminate the heritage bequeathed to us by the Vetton communities, as well as the different initiatives carried out in this area by our team in recent years. Finally, we will propose some directions for future actions we believe to be essential for achieving a more effective dissemination.

2. The Present Past

The initial steps in their recovery quickly led to the growing fame of these archaeological sites [21,22]. Since then, the province of Ávila has witnessed some of the most important Iron Age excavations in north–central Spain, with a growing awareness and interest from the local population in the past. Suffice it to point out the archaeological excavations of El Raso and Las Cogotas [23,24,25,26,27], the different interventions in Sanchorreja and La Mesa de Miranda [28,29,30,31], the review of the necropolis associated with this last site [32], the surveys around Ulaca and the Amblés valley and the subsequent discovery of the cemetery [33,34,35], and the public presentation of these sites [36].

This dynamism of archaeological research into the large oppida explains the major exhibition on Celts and Vettones held in Ávila [37], which was extraordinarily successful among the public and had an important impact on society [38]. The exhibition received more than 120,000 visitors in just three months, sold more than 5000 catalogues and promoted a unique offer of “Celtic foods” in the town’s restaurants and hotels. Subsequent exhibitions, also in Ávila, were devoted to the discovery of the Vettones [39] and their relations with the Iberian and Mediterranean regions [40]. To these we should add the Vettones. Shepherds and Warriors of the Iron Age exhibition held at the Regional Archaeological Museum of the Community of Madrid [41].

Shortly after, the European Interreg III-A project between Salamanca, Ávila and the north of Portugal, headed by the Diputación de Ávila (Regional Government of Ávila), provided another decisive impetus for the recognition and dissemination of the archaeological heritage of the oppida in different formats [42]. There were new excavations; new restoration tasks and public presentations [43,44]; guide books and other informative publications (Cuadernos de Patrimonio Abulense); scientific meetings (Castros y Verracos, Gentes de la Edad del Hierro en el Occidente de Iberia—Hillforts and Verracos, Iron Age People in Western Iberia, Ávila, 2004) [45]; the establishment of a permanent exhibition centre dedicated to the Vettones (Vettonia. Cultura y Naturaleza) [46]; specific actions on some verracos, such as the restoration of the bull in Villanueva del Campillo (Ávila) (Figure 2) [21] (pp. 35–36); and a tourist route taking in the archaeological sites and most emblematic verracos [44].

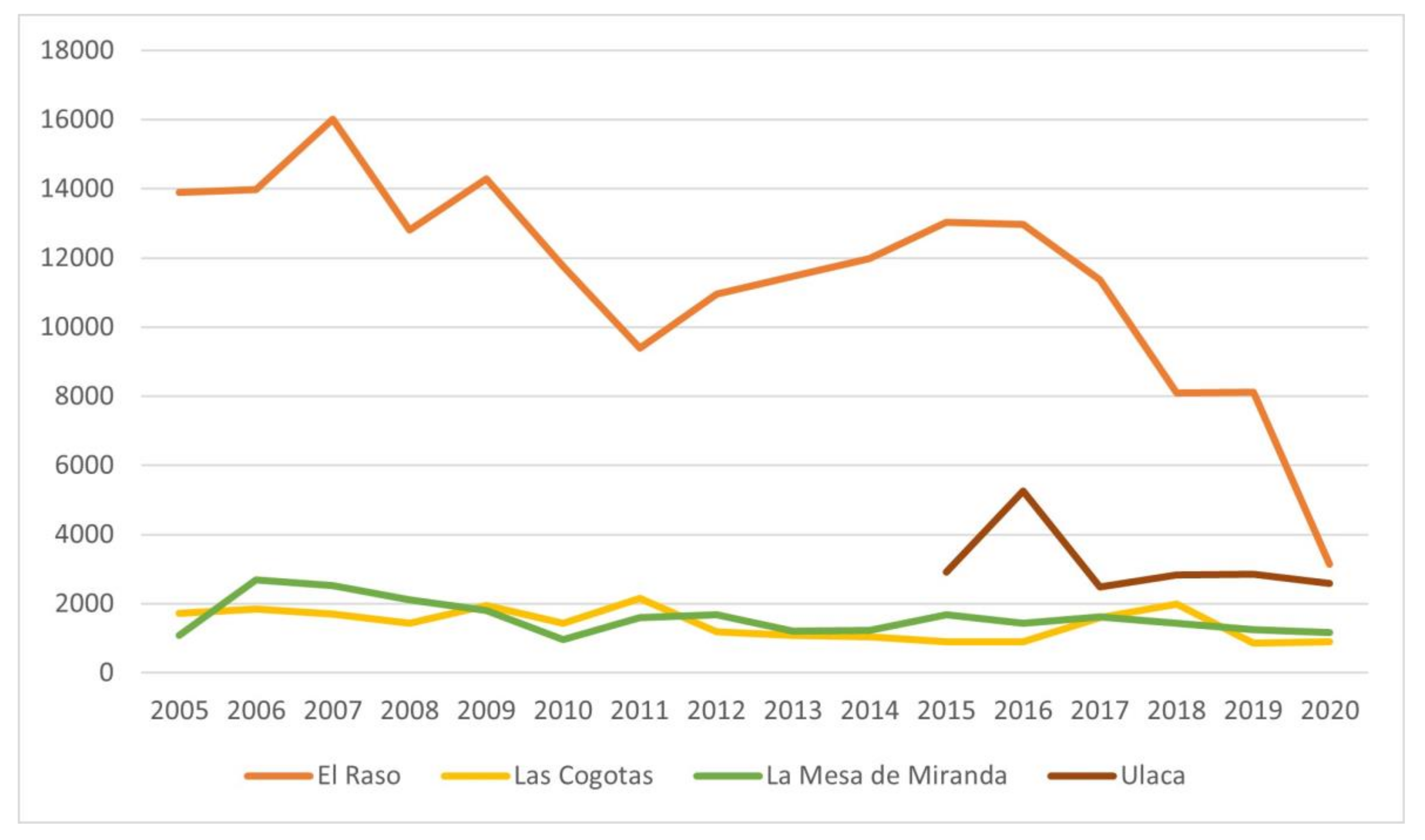

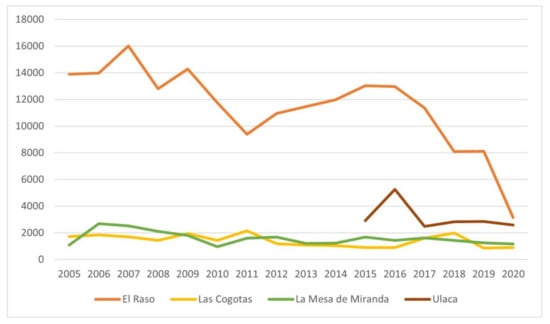

All these actions led to a large increase in the number of visits to these sites, between 43% and 75% from 2001 to 2006 [22] (p. 434). However, an analysis of the visitor data to these same sites corresponding to the period 2005–2020 yields a much less positive reading. In the cases of Las Cogotas, La Mesa de Miranda and Ulaca, there appears to be a detectable stagnation in the annual trend of visitors and in the case of El Raso, the number of visits is in clear decline (Table 1 and Figure 3). These numbers are observed despite the opening in 2015 of the Municipal Archaeological Museum of El Raso and the activities programmed by the new Ávila Range and Amblés Valley Open Museum (Museo Abierto Sierra de Ávila y Valle Amblés –MASAV–), which include guided tours to the other three sites analysed (https://masavterralevis.org/ (accessed on 1 December 2022)) [47]. However, we have to take into account that these data are approximate since they are obtained from the controls carried out by the guards who monitor these sites, who do not work every day of the week. In addition, there have occasionally been periods during which some sites have not been guarded and, in the case of the data corresponding to the year 2020, during the months of April and May, there were no visits due to the COVID-19 pandemic confinement [48,49].

Table 1.

Number of visitors to the main visitable Iron Age sites in Ávila. 2005–2014 data according to Castelo Ruano and González Casarrubios [48]. 2015–2020 data according to Maté-González et al. [49].

Figure 3.

Evolution of visitor numbers to the main visitable oppida in the province of Ávila (2005–2020). Graph prepared from the data compiled in Table 1.

However, the different actions undertaken are not without problems. The construction and rehabilitation of buildings for archaeology rooms and interpretation centres (Figure 4) around the most outstanding pre-Roman enclaves of Ávila and Salamanca [22,50] have been undertaken without carrying out a serious evaluation of the potential number of visitors [51]. This means that many of these centres are not viable in the medium and long term and even present deficiencies [20]. Similarly, in some cases, walls and gateways have been restored without prior excavation, meaning we have lost a valuable opportunity to increase our knowledge of their structure and dating [7] (p. 67). Finally, in the case of the verracos, there have been controversial interventions, such as the transfer of the Villanueva del Campillo sculptures from the field in which they were presumably installed in pre-Roman times to the town square (Figure 2) [52].

Figure 4.

Interpretation centre at the La Mesa de Miranda oppidum (Chamartín, Ávila).

The growth of research and dissemination in the last thirty years has also given rise to new forms of appropriation of the past in contemporary culture. There is even talk of a popular “Vettonism” [53] (pp. 411–421) that takes the most representative elements from archaeological iconography for the construction of identities and “prestige referents” [54,55]. The manifestations are multiple: logos inspired by verracos and horse-shaped brooches (Figure 5), festivals and recreations such as Luna Celta (Celtic Moon) in Ulaca and Solosancho, souvenirs, and even fictional recreations in novels and comics set in the Iron Age.

Figure 5.

Some of the prestige archaeological icons used by institutions and companies in the province of Ávila and nearby territories: (A) The Solosancho coat of arms with a verraco from the Ulaca oppidum; (B) Regional government tourism logo; (C) Vettonia Hockey Club logo; (D) ‘Tierra Vettona’ craft beer; (E) ‘Vettonia’ security company; (F) Carne de Ávila (Ávila Beef) logo, with the profile of a pre-Roman bull-shaped sculpture; (G) ‘Vettonia’ goat cheese.

In this context, the impact of archaeology is so real that recent prehistory becomes useful for creating feelings of local identity, a way of reaffirming the specificity of current societies in the context of cultural globalisation [56,57]. On the other hand, the archaeological sites presented to the public—and especially those of the Iron Age with their imposing structures—allow the different audiences to be introduced to an almost “living” past. This allows the visitors to empathise with the land and the missing people, which is difficult to achieve by other means [58].

3. The REFIT Project

Knowing the impact that cultural landscapes and their archaeological sites have on the rural communities that live in their environs is important, because the interest has a lot to do with the economy, archaeology, ecology, leisure and other uses. However, this is a very underdeveloped topic in archaeological heritage research [59,60]. One of the research projects that successfully competed in the 2015 call for International Joint Programming Actions, within the framework of the European Horizon 2020 programme, was Resituating Europe’s first towns: A case study in enhancing knowledge transfer and developing sustainable management of cultural landscapes (acronym: REFIT) [61]. It was made possible by joint funding from the British, French and Spanish governments through the Joint Heritage European Program (JHEP), the Joint Heritage Initiative (JHI) and Heritage Plus.

Between 2015 and 2018, the project explored how local communities (farmers, stockbreeders, small- and medium-sized enterprises, nature protection organisations, cultural associations, etc.) understand and experience cultural landscapes [2,3,62,63,64]. For this purpose, the existing experience and knowledge of the oppida in the scope of three academic institutions was maximised. These were the Department of Archaeology at the University of Durham (United Kingdom), the European Archaeological Centre of Bibracte (France) and the Department of Prehistory at the Complutense University of Madrid (Spain).

Despite their importance as the germ of European urbanism, oppida are barely recognised as foci for the cultural and economic sustainability of the rural areas where they emerge. The REFIT project began by recognising that the ecology, heritage, flora and fauna of these unique landscapes inhabited in prehistory cannot be dissociated from the economic value they have today. Therefore, in collaboration with other interested entities—Gloucestershire Wildlife Trust, Cotswold Archaeology (United Kingdom), Réseau des Grands Sites de France, Parc naturel régional du Morvan (France) and the Regional Government of Ávila (Spain)—our objective was to examine the perceptions and needs of different stakeholders and to try and integrate them into archaeological research.

We focused on four large oppida and their landscapes: Bibracte in France, Bagendon and Salmonsbury in the UK, and Ulaca in Spain. These examples reflect the idiosyncrasies of a characteristic European Iron Age phenomenon, as well as the different ways we have of understanding, investigating and managing these unique places today [62]. They have truly fascinating histories, but also different uses. The four landscapes offer a vast archaeological heritage represented by Iron Age oppida and an important ecological value.

With archaeological research still ongoing, these four sites provide an excellent example of how archaeologists attempt to engage—to a greater or lesser extent—groups outside of academia (small landowners and entrepreneurs, farm workers, heritage and tourism managers, managers and politicians responsible for national parks, environmental and cultural associations, etc.).

The diversity of the case studies was deliberate. Thus, we addressed the different approaches to and levels of perception of these cultural landscapes, seeking novel methods to improve the way in which they are managed and, at the same time, increasing the transfer of knowledge. The REFIT project has developed sustainable strategies related to the management and use of cultural heritage. It has done this, essentially, by focusing on the underlying links between (1) sustainable landscapes, (2) protected heritage and (3) research dissemination.

For this purpose, a whole series of methodological tools has been developed, including questionnaires, mind-mapping exercises and interviews/surveys with heritage managers, politicians, local association members, etc. [2]. Likewise, we have carried out workshops and participatory events during fieldwork, disseminated on social media (Twitter and Facebook). In addition, we have analysed how the studied oppida are represented on the most popular photo-sharing platforms (Flickr, Snapfish, etc.).

The aim has been to promote the internationalisation of the action, to improve knowledge transfer and to develop a sustainable management for these cultural landscapes. In addition, a series of interactive digital guides has been produced, among them one on Ulaca. They offer a holistic perspective of each cultural landscape and can be consulted on the REFIT project website (http://www.refitproject.com (accessed on 1 December 2022)). By working on European heritage assets—late-Iron-Age oppida—the social and scientific impact of this project has become clear, as it has led to the development of long-term sustainable strategies and mechanisms applicable to other case studies.

Between 2016 and 2018, we undertook various fieldwork projects in the four aforementioned oppida. In the particular case of Ulaca, the building known as El Torreón (The Tower) was excavated and presented to the public, while a team of specialists carried out geophysical surveys of the site to determine the characteristics of the subsoil and identify structures of anthropic origin [65]. A photogrammetric flight with a fixed-wing drone was also able to identify other similar constructions from a zenithal perspective. In this way we obtained a quality planimetry of the site and defined its general urban morphology, developing a useful model of internal occupation and aspiring to make plausible demographic estimates. At the same time, we contextualised the immediate territory of the oppidum, defining Ulaca’s relationship with its environs and the nearby verraco sculptures.

Our understanding of the studied surface areas has improved considerably compared to the challenges confronted by traditional archaeological interventions. These studies have also opened up new ways of analysing the functional organisation of settlements and provided new ideas for understanding the contrast between the urban and rural worlds in the period preceding the Roman conquest. Simultaneously, we organised participation events aimed at local communities to enable them to learn about the practices and the most interesting results of the research carried out.

Within the events held in Ulaca, the open days and the guided tours offered to the schoolchildren (about fifty at the ages of 5–11) who participate in the summer camps every year are particularly special (Figure 6). Another of the most notable activities has been the ethnographic analysis of the Celtic festival that has been held since 2005 in Solosancho (Figure 7) [66,67] and has become increasingly popular (almost 3000 people participated in the night climb to Ulaca in 2016 and 2017). The objective of the study was to evaluate (1) the local population’s degree of involvement in the defence and promotion of their heritage, (2) the festival’s evolution throughout its thirteen editions (it has now reached the sixteenth after a two-year break due to the pandemic), (3) the documentary sources on which the theatrical performance, the costumes, the storytellers, etc., are based, (4) the audiences of the different organised events, and (5) the economic impact of the festival on Solosancho and other nearby towns.

Figure 6.

Children from the Ulaka camp visit the oppidum in 2019. During the tour, they were able to learn about the archaeology of the site and the main features of the surrounding landscape.

Figure 7.

Luna Celta festival closing ceremony (2017 edition).

The management strategies of the oppida landscapes, with special attention, in the Spanish case, to those of Ulaca, Las Cogotas and La Mesa de Miranda, have been discussed in different workshops, including (1) The management of oppida landscapes: current strategies, problems and potential, held in March 2016 in Bibracte (France); (2) Engaging stakeholders in oppida heritage: challenges and possibilities, held in October 2016 in Ávila (Spain); and (3) Working across boundaries: Integrating different stakeholder approaches to cultural landscapes, held in September 2017 in Cirencester (United Kingdom). Among other benefits, these forums allowed for reflection on the sustainable management of European late-Iron-Age oppida and the challenges and successes in the co-production of the management of the cultural landscapes in which they are inserted.

Archaeological sites such as Ulaca represent a particular challenge and a unique opportunity for us to explore how people perceive these sites today and how they can be reasonably managed [59]. The archaeology of oppida involves the mobilisation of important social and economic resources and cannot be reduced to basic research [68]. The interpretation and presentation of the past are inseparable from their social basis, and archaeology is no different from other disciplines in that it has responsibilities to the citizenship. We need to develop a more inclusive management of the landscape to value and highlight its archaeological heritage and vice versa, understanding that the landscape is the support of any heritage location [69] (p. 126).

The objective must be based on four components: first, the local communities and agents who live and operate in those territories; second, the cultural landscapes themselves as immense containers of the human footprint over time; third, the different types of heritage structured holistically among themselves, not only the archaeological, but also the natural and ethnographic; and fourth, the research, production and dissemination of the knowledge generated, which should provide feedback on all the above. As Ballart [69] (p. 127) wisely concluded, “any archaeological site must be able to explain a story that captures the desire and imagination of the people and each locality is potentially in a position to obtain the greatest benefit from the patrimony it treasures”.

4. The VETTONIA Project

The VETTONIA project: a virtual environment for the dissemination of the Iron Age, financed by the Spanish Foundation for Science and Technology (FECYT), is currently ongoing. Its main objective is the dissemination of the rich heritage bequeathed to us by the Vetton communities and the research carried out in this area in recent years. To do this, it intends to create and improve different virtual tours of the Ulaca, La Mesa de Miranda and Las Cogotas archaeological sites, to print 3D models of their main monuments and some of the finds excavated in recent years, and to carry out a series of dissemination activities aimed at different audiences.

The first of the aforementioned initiatives consists of improving the virtual environment of the Ulaca oppidum already created in a previous project (https://tidop.usal.es/Ulaca/(accessed on 1 December 2022)) [49], adding information on the different methodologies and techniques applied to the study of the site and their corresponding results. This improved prior experience will be replicated for the other two case studies by creating virtual tours. To prepare for this, data have been collected in the field that involve photographing the different panorama views that constitute the skeleton of the virtual tool (Figure 8) and geometrically characterising the different buildings that make up the two archaeological sites, using drones and conventional photography to document some of the structures in detail. The virtual tours created will include numerous historical-archaeological facts, landscape and ecological information, the different study methodologies applied, and 3D virtual models of the most outstanding monuments and artifacts found in recent archaeological excavations.

Figure 8.

Taking panoramic photographs at Las Cogotas oppidum (Cardeñosa, Ávila).

This action is intended to attract visitors to these sites and thus promote sustainable tourism in fragile natural environments that have been seriously harmed by depopulation and natural disasters, such as the huge forest fire that severely impacted Ulaca and the entire surrounding landscape in 2021 [49] (pp. 15–16). Virtual tours are also valuable tools for presenting numerous types of information to the general public in a contextualised and highly suggestive manner, including the results of the research carried out in recent years.

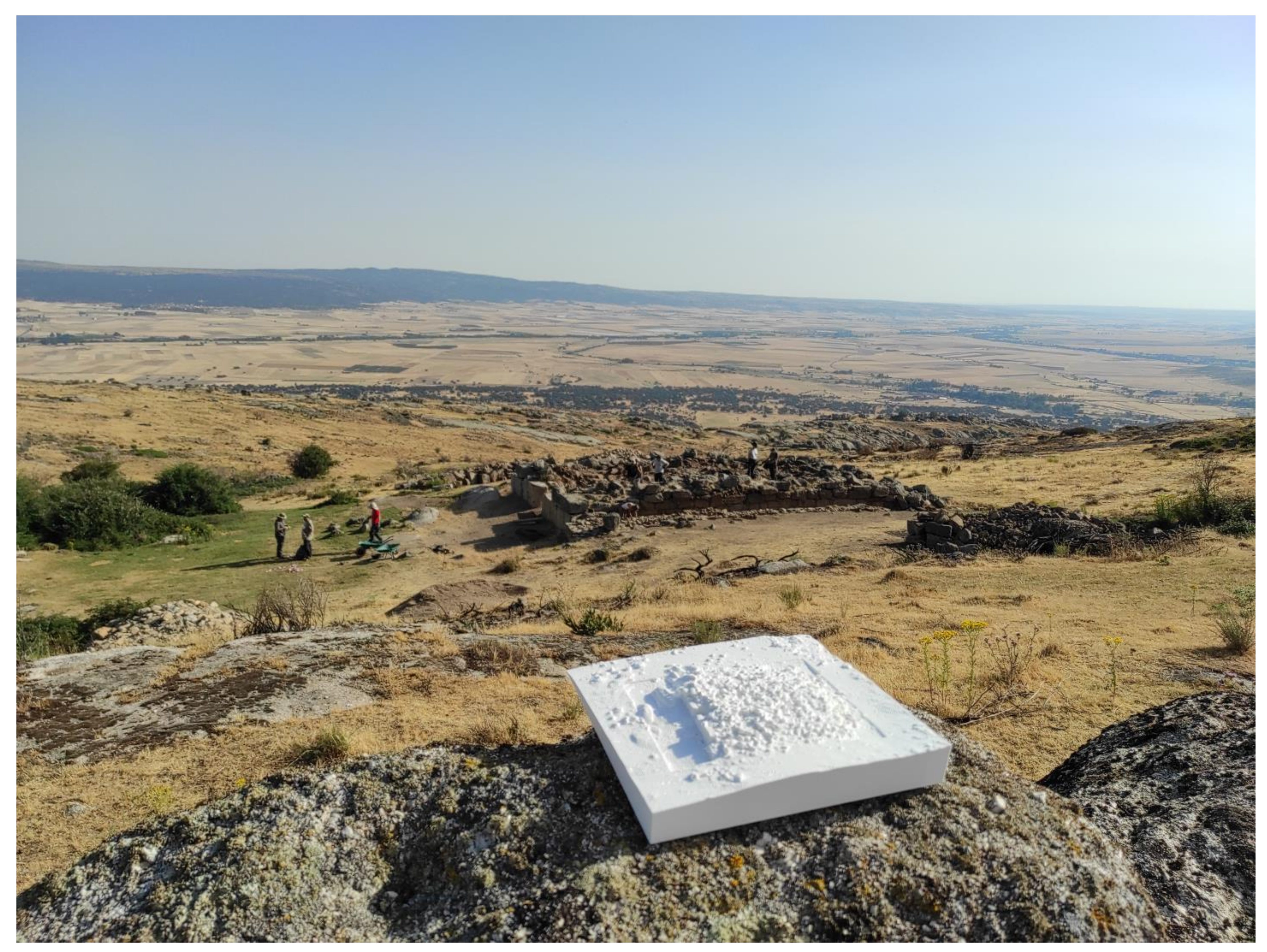

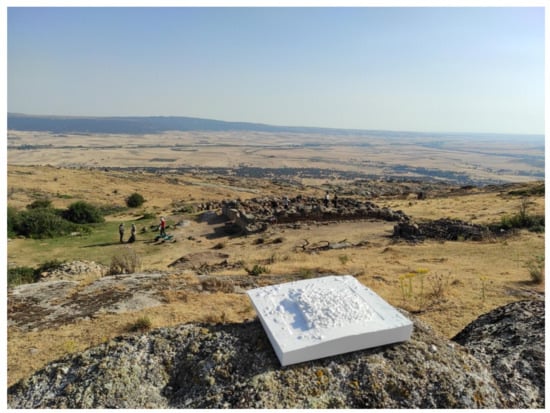

The second set of initiatives, to be carried out within the framework of the VETTONIA project, consists of different dissemination activities aimed at both the general public and students and professionals. Different members of the research team will explain the methodologies used, the findings achieved and the results obtained from the different projects they have undertaken in recent years. To this end, talks and seminars have been scheduled to be given throughout the duration of the project in various forums: the municipalities in which the analysed archaeological sites are located (including field demonstrations during the excavation campaigns carried out at Ulaca), Ávila capital, educational institutions (secondary schools and/or universities), and scientific dissemination at conferences and specialised congresses. Three-dimensionally printed replicas of Iron Age monuments and findings will be of great help in such presentations (Figure 9). The aim of this activity is to show the different scientific disciplines involved in the archaeological process first-hand and the results that can be obtained, highlighting the importance of applying technological innovations in this field and the importance of the composition of multidisciplinary teams in the study of the past [65].

Figure 9.

In the foreground, a 3D printed replica of El Torreón (Ulaca oppidum). In the background, a view of the excavation work on the building (2022 campaign).

In summary, it is about finding attractive ways to bring heritage and archaeological studies closer to society by taking advantage of the new technologies. Thus, we aim to transmit the results of the research to society in general and avoid historical knowledge remaining solely in the scientific field, as well as to promote an appreciation of archaeology and heritage among the general public [60]. In this way, we aspire to encourage respect for our archaeological heritage, which is under considerable threat from, among other factors, looters and the illicit trade in cultural property. We also wish to raise awareness of how important it is to preserve this heritage for future generations.

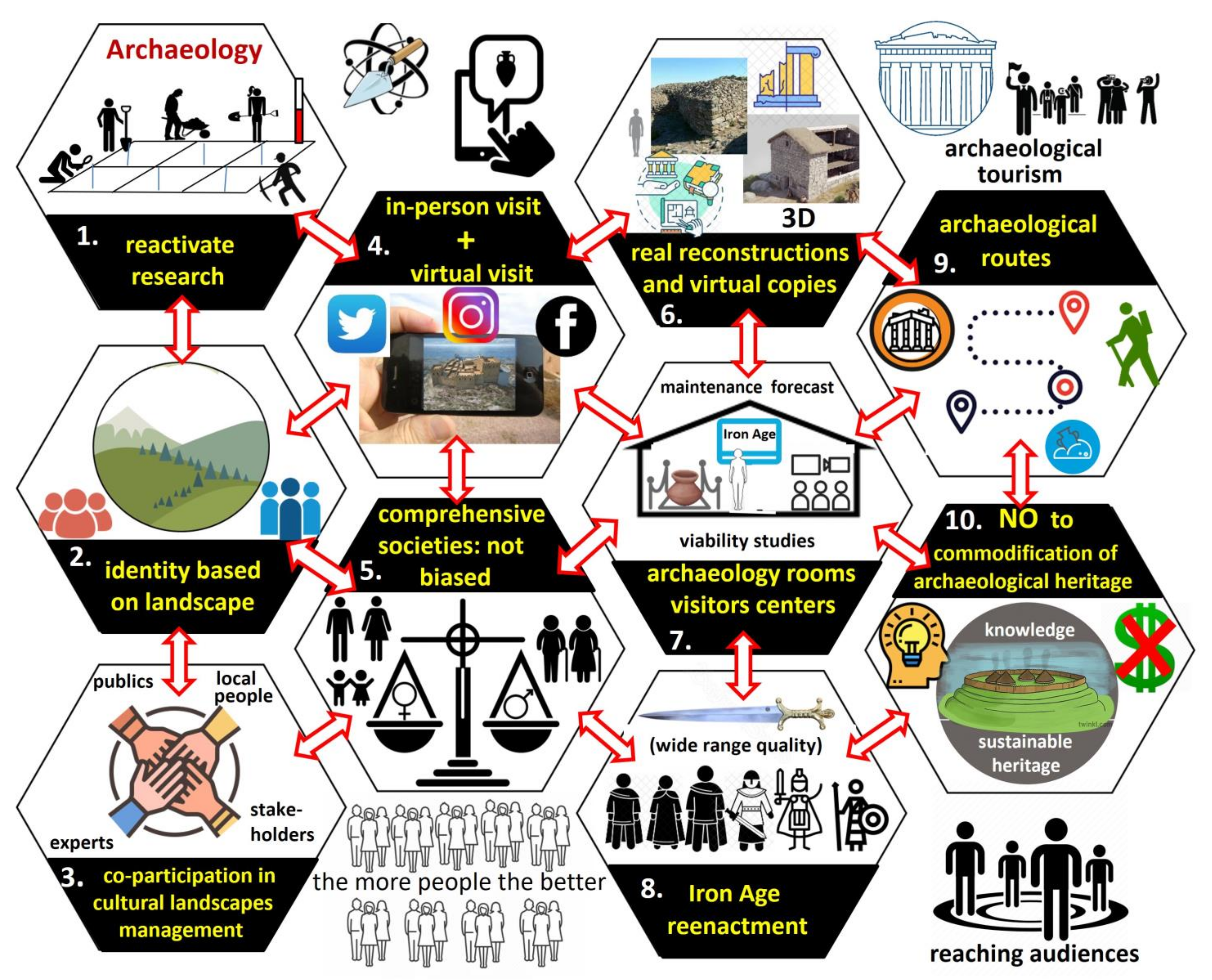

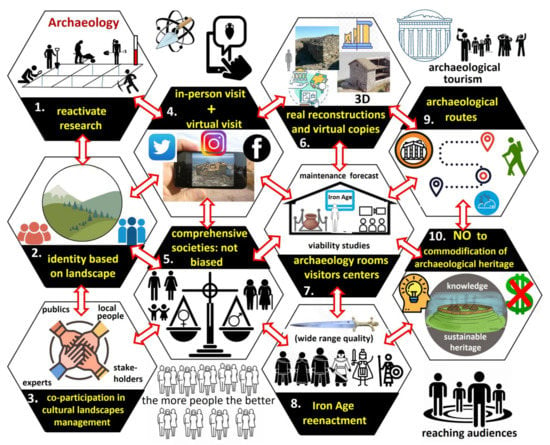

5. Future Perspectives

Below, we present ten proposals for future actions we believe to be essential for achieving a more effective dissemination of our Iron Age heritage, paying special attention to the western Iberian Peninsula (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Ten future action proposals for the dissemination and management of Iron Age heritage.

- After three decades characterised mainly by the enhancement of some settlements and the dissemination of the protohistoric communities of western Iberia, it is necessary to reactivate archaeological research. This is because “only serious and cutting-edge research allows the past to be disseminated effectively and coherently to the various audiences” [42] (p. 9). These new interventions should focus not only on the large oppida known for centuries, but also on some of the settlements that remain virtually unpublished and that can provide valuable data to broaden our perspective on the people of the Iron Age. This will allow us to spread a more plural and comprehensive vision of these societies.

- It would be interesting to try a new formula in the dissemination strategy to link the people of the present with the societies of the past through the landscape and not only through some supposed distant forebears (Celts, Gauls, Vettones, etc.) or ancestors [70]. On the one hand, this would avoid the usual attempts by nationalist and regionalist movements to manipulate the discourse [71,72,73,74]. On the other hand, it would allow a better integration of all the inhabitants of a certain area, including migrants, since everyone, even if they have only been in an area for a short time, contributes to the construction of the landscape in which they live. This change in the dissemination strategy has already been implemented, for example, in the renovated Bibracte Museum (Glux-en-Glenne, France) [70].

- In relation to the previous point, it would be convenient to progress in the integral management of cultural landscapes through the participation and co-production of all the agents involved [3]. The “principle of participation” established in the Rio Declaration [75], reinforced in the Aarhus Convention [76] and promoted in the Faro Convention [77], emphasises that the various stakeholders must be an integral part of landscape and heritage management. In this respect, it is necessary to recognise the importance of the participation of the different stakeholders in the management, since in this way, the long-term sustainability of the landscape and the cultural heritage it treasures is guaranteed [78]. This alternative management model is “in line with the principles of participatory governance, rather than those of traditional heritage protection, aimed at protecting and conserving, rather than guiding and leading change” [79] (p. 13). However, this commitment to citizen participation runs the risk of remaining a mere symbolic effort [80] if there is no clear promotion of a participatory culture that leads to the development of real transformative processes.

- The objective of the public presentation of archaeological sites should be “direct contact with the ruins, their contextualisation in the landscape and their historical understanding” [58] (p. 36). However, although it may seem contradictory, it is necessary to take firm steps in heritage digitalisation, due to the enormous possibilities offered by digital tools such as virtual tours. Thus, among other things, these virtual itineraries can provide valuable general information when it comes to understanding the relevance of the site visited, allow access to 3D models of monuments that at some point may suffer damage or even complete destruction, and to 3D reconstructions of some of the finds from the excavations. They may also be the only way people with mobility difficulties have of coming into contact with the archaeological remains in hard-to-access sites [49,81].

- Traditionally, in Iron Age studies, the story has focused on the role played by men, and male warriors have been represented almost exclusively [82] (p. 147). It is therefore imperative to incorporate women, children, the elderly, peasants, potters, etc., in the texts and illustrations. Fortunately, in this respect, we have an increasing number of publications that attempt to alleviate this research imbalance [83,84,85,86,87] and that can be used to disseminate a less biased image of the pre-Roman societies of the Iberian Peninsula.

- The reconstruction of structures present at archaeological sites, such as walls, houses or burial mounds, represents a great opportunity when it comes to attracting more visitors and communicating the past to a wider audience. However, we have to be aware of its inherent problems [88] and demand the maximum possible rigour in its undertaking, making the available evidence used to carry out the reconstruction clear. An alternative that merits an increasing level of commitment, given its multiple advantages, is the creation of virtual reconstructions. In contrast to the closed and unique image provided by traditional reconstructions [58] (p. 37), the virtual equivalent is open and plural [89] (p. 15), allowing different alternatives to be proposed with absolute respect for the ruins and at a lower cost.

- The incorporation of archaeology rooms and interpretation centres at archaeological sites undoubtedly facilitates their understanding, by allowing the use of resources such as videos, models, manipulable reproductions or even augmented reality [58,90]. However, in Spain, many of these centres “were installed in periods of economic prosperity without taking into account their viability and sustainability in the medium to long term, thus endangering their opening to the public” [20] (p. 606). For this reason, in future, it would be advisable to make serious estimates of the potential number of visitors before embarking on such projects [51], although economic viability should not be the only parameter to take into account in this type of cultural investment. In addition, it would also be opportune to make an exhaustive evaluation of the strengths and weaknesses that can be detected in the rooms and centres already in place to improve those that may be built in the coming years [48].

- There has been an enormous growth in recent years in historical re-enactments, with more and more people contributing as organisers, participants and spectators. This represents an opportunity that archaeologists and heritage managers should take advantage of to disseminate our archaeological narratives to wider audiences. To achieve this, we have to change our habitual attitude towards this type of event and be more constructive, participating in them and even getting involved in their organisation to promote changes in cultural representations [66,91]. However, it is not about imposing our expert vision on the public, but about working together with other groups, learning about their concerns and perspectives and transferring a more positive image of archaeology as a discipline useful to society.

- The potential of archaeological itineraries, such as the Hillforts and Verracos Route [44], suggests it would be worth redoubling efforts in this regard. This type of project makes it possible to channel different local, county and regional heritage initiatives and, in this way, develop an archaeological heritage management model capable of generating resources for the maintenance and improvement of the sites that make up the different routes. In addition, archaeological tourism can become a sustainable alternative for local economies in territories that are suffering from rural depopulation [18]. In any case, it is always necessary to place the integrity of the sites and their surroundings before the economic returns that this touristic activity can generate.

- The rise in the dissemination and public presentation of archaeological sites and archaeological tourism in the last two decades [20] should lead us to remain alert and oppose the simple commodification of archaeological sites and the past in general [92].

In short, all these proposals are aimed at achieving a more powerful, diverse and rigorous dissemination and, in this way, at promoting a more informed, critical and aware society with regard to archaeological heritage and nature. Likewise, these propositions for the future aim to develop solid connections between archaeologists and local communities, through the participation of multiple local agents in the management of their heritage, thus responding to their identity and development desires.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.R.-H., J.R.Á.-S. and G.R.-Z.; methodology, J.R.-H., J.R.Á.-S., M.Á.M.-G., C.D.-S., M.S.F.-B. and G.R.-Z.; validation, J.R.-H., J.R.Á.-S., M.Á.M.-G. and G.R.-Z.; formal analysis, J.R.-H. and J.R.Á.-S.; investigation, J.R.-H., J.R.Á.-S., M.Á.M.-G., C.D.-S., M.S.F.-B. and G.R.-Z.; resources, J.R.-H., J.R.Á.-S., M.Á.M.-G. and G.R.-Z.; data curation, J.R.-H., J.R.Á.-S., M.Á.M.-G., C.D.-S., M.S.F.-B. and G.R.-Z.; writing—original draft preparation, J.R.-H., J.R.Á.-S., M.Á.M.-G., C.D.-S., M.S.F.-B. and G.R.-Z.; writing—review and editing, J.R.-H., J.R.Á.-S., M.Á.M.-G., C.D.-S., M.S.F.-B. and G.R.-Z.; supervision, J.R.-H., J.R.Á.-S. and G.R.-Z.; project administration, J.R.-H., J.R.Á.-S., M.Á.M.-G. and G.R.-Z.; funding acquisition, J.R.-H., J.R.Á.-S., M.Á.M.-G. and G.R.-Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been partially funded by the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (PCIN-2015-022), Fundación Española para la Ciencia y la Tecnología (FCT-21-17318), the project PID2021-123721OB-I00 funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033/FEDER, UE and the grant RYC2021-034813-I funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by European Union “NextGenerationEU”/PRTR.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to the members of the REFIT and VETTONIA project research teams, as well as to the institutions and people who have contributed to the successful development of those projects. We also wish to express our thanks to the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ruiz Zapatero, G.; Álvarez-Sanchís, J.R.; Rodríguez-Hernández, J. Urbanism in Iron Age Iberia: Two Worlds in Contact. J. Urban Archaeol. 2020, 1, 123–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tully, G.; Piai, C.; Rodríguez-Hernández, J.; Delhommeau, E. Understanding perceptions of cultural landscapes in Europe: A comparative analysis using ‘oppida’ landscapes. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2019, 10, 198–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, T.; Guichard, V.; Álvarez-Sanchís, J.R. The place of archaeology in integrated cultural landscape management: A case study comparing landscapes with Iron Age oppida in England, France and Spain. J. Eur. Landsc. 2020, 1, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tully, G. Resituating cultural landscapes: Pan-European strategies for sustainable management. In Heritage 2016, Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Heritage and Sustainable Development; Amoêda, R., Lira, S., Pinheiro, C., Eds.; Green Lines Institute for Sustainable Development: Barcelos, Portugal, 2016; Volume 1, pp. 347–359. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-Sanchís, J.R.; Ruiz Zapatero, G.; Rodríguez-Hernández, J. Arqueología y comunidad en Ulaca (Solosancho, Ávila): La gestión de los oppida como paisajes culturales. In Investigar el pasado para entender el presente. Homenaje al profesor Carmelo Luis López; Institución Gran Duque de Alba: Ávila, Spain, 2019; Volume 1, pp. 75–90. [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, U. Some reflections on site presentation. In Gestion et Présentation des Oppida. Un panorama Européen = Management and Presentation of Oppida: A European Overview; Benkova, I., Guichard, V., Eds.; Bibracte-Institut Archéologique de Bohême Centrale: Glux-en-Glenne-Prague, France-Czech Republic, 2008; pp. 165–178. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/1337271/Some_reflections_on_site_presentation (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Collis, J. The vettones in a european context. In Arqueología Vettona. La Meseta Occidental en la Edad del Hierro; Álvarez-Sanchís, J.R., Ed.; Museo Arqueológico Regional: Alcalá de Henares, Spain, 2008; pp. 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-Sanchís, J.R. Zoomorphic Iron Age Sculpture in Western Iberia: Symbols of Social and Cultural Identity? Proc. Prehist. Soc. 1994, 60, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Zapatero, G.; Álvarez-Sanchís, J.R. Los verracos y los vettones. In Arqueología Vettona. La Meseta Occidental en la Edad del Hierro; Álvarez-Sanchís, J.R., Ed.; Museo Arqueológico Regional: Alcalá de Henares, Spain, 2008; pp. 214–231. [Google Scholar]

- Berrocal-Rangel, L.; García-Giménez, R.; Manglano, G.R.; Ruano, L. When archaeological context is lacking. Lithology and spatial analysis, new interpretations of the “verracos” Iron Age sculptures in Western Iberian Peninsula. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2018, 22, 344–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariné, M. Ávila, tierra de verracos . In Arqueología Vettona. La Meseta Occidental en la Edad del Hierro; Álvarez-Sanchís, J.R., Ed.; Museo Arqueológico Regional: Alcalá de Henares, Spain, 2008; pp. 440–453. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, D.; Smith, S.N.; Ostergren, G. Consensus Building, Negotiation and Conflict Resolution for Heritage Place Management: Proceedings of a Workshop Organizated by the Getty Conservation Institute, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1–3 December 2009; Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, D.; Smith, S.N.; Shaer, M. A Didactic Case Study of Jarash Archaeological Site, Jordan: Stakeholders and Heritage Values in Site Management; Getty Conservation Institute-Dept. of Antiquities, Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hodder, I. Is a shared past possible? The ethics and practice of Archaeology in the twenty-first century. In New Perspectives in Global Public Archaeology; Okamura, K., Matsuda, A., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2011; pp. 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Cabré Aguiló, J. Excavaciones de Las Cogotas, Cardeñosa (Ávila). I. El Castro; Junta Superior de Excavaciones y Antigüedades: Madrid, Spain, 1930. [Google Scholar]

- Cabré Aguiló, J. Excavaciones de Las Cogotas, Cardeñosa (Ávila). II. La Necrópoli; Junta Superior de Excavaciones y Antigüedades: Madrid, Spain, 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Cabré Aguiló, J.; Cabré de Morán, M.E.; Molinero Pérez, A. El castro y la necrópolis del Hierro céltico de Chamartín de la Sierra (Ávila); Comisaría General de Excavaciones Arqueológicas: Madrid, Spain, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer García, C.; Vives-Ferrándiz Sánchez, J. Patrimonio arqueológico y turismo. Unas reflexiones finales. In El Pasado en su Lugar. Patrimonio, Arqueología, Desarrollo y Turismo; Vives-Ferrándiz, J., Ferrer, C., Eds.; Museu de Prehistòria de València: Valencia, Spain, 2014; pp. 177–189. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno Melgarejo, A.; Sariego López, I. Relaciones entre Turismo y Arqueología: El Turismo Arqueológico, una tipología turística propia. PASOS Rev. De Tur. Y Patrim. Cult. 2017, 15, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega López, D.; Collado Moreno, Y. Arqueoturismo ¿un fenómeno en auge? Reflexiones acerca del turismo arqueológico en la actualidad en España. PASOS Rev. De Tur. Y Patrim. Cult. 2018, 16, 599–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabián García, J.F. Recuperación, rehabilitación y difusión del patrimonio arqueológico de Ávila. In Actas. Puesta en valor del patrimonio arqueológico en Castilla y León; Val Recio, J., Escribano Velasco, C., Eds.; Junta de Castilla y León: Salamanca, Spain, 2004; pp. 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Fabián García, J.F. La arqueología y el público en los yacimientos vettones de Ávila y Salamanca. In Arqueología Vettona. La Meseta Occidental en la Edad del Hierro; Álvarez-Sanchís, J.R., Ed.; Museo Arqueológico Regional: Alcalá de Henares, Spain, 2008; pp. 424–439. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Gómez, F. Excavaciones Arqueológicas en el Raso de Candeleda (I-II); Institución Gran Duque de Alba: Ávila, Spain, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Gómez, F. La Necrópolis de la Edad del Hierro de “El Raso” (Candeleda. Ávila) “Las Guijas, B”; Junta de Castilla y León: Zamora, Spain, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Gómez, F. El Poblado Fortificado de “El Raso de Candeleda” (Ávila): El núcleo D. Un Poblado de la III Edad del Hierro en la Meseta de Castilla; Universidad de Sevilla-Institución Gran Duque de Alba-Real Academia de la Historia: Sevilla, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Zapatero, G.; Álvarez-Sanchís, J.R. Las Cogotas: Oppida and the Roots of Urbanism in the Spanish Meseta. In Social Complexity and the Development of Towns in Iberia: From the Copper Age to the Second Century AD; Cunliffe, B.W., Keay, S.J., Eds.; British Academy: London, UK, 1995; pp. 209–235. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Entrecanales, R. Castro de Las Cogotas. Cardeñosa, Ávila; Institución Gran Duque de Alba: Ávila, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- González-Tablas Sastre, F.J. La necrópolis de «Los Castillejos» de Sanchorreja: Su contexto histórico; Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca: Salamanca, Spain, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- González-Tablas Sastre, F.J. Castro de Los Castillejos. Sanchorreja, Ávila; Institución Gran Duque de Alba: Ávila, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fabián García, J.F. Castro de La Mesa de Miranda. Chamartín, Ávila; Institución Gran Duque de Alba: Ávila, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- López García, J.P. Arqueología de la arquitectura en el mundo vettón. La Casa C de La Mesa de Miranda; Ediciones de La Ergástula: Madrid, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Baquedano Beltrán, I. La necrópolis vettona de La Osera (Chamartín, Ávila, España); Museo Arqueológico Regional: Alcalá de Henares, Spain, 2016; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Zapatero, G. Castro de Ulaca. Solosancho, Ávila; Institución Gran Duque de Alba: Ávila, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-Sanchís, J.R.; Marín, C.; Falquina, A.; Ruiz Zapatero, G. El oppidum vettón de Ulaca (Solosancho, Ávila) y su necrópolis. In Arqueología Vettona. La Meseta Occidental en la Edad del Hierro; Álvarez-Sanchís, J.R., Ed.; Museo Arqueológico Regional: Alcalá de Henares, Spain, 2008; pp. 338–361. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Hernández, J. Poder y sociedad: El oeste de la Meseta en la Edad del Hierro; Institución Gran Duque de Alba: Ávila, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-Sanchís, J.R. Guía arqueológica de castros y verracos. Provincia de Ávila; Institución Gran Duque de Alba: Ávila, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Almagro-Gorbea, M.; Mariné, M.; Álvarez-Sanchís, J.R. Celtas y Vettones, 4th ed.; Institución Gran Duque de Alba-Real Academia de la Historia: Ávila, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mariné, M. La fama de los vettones en Ávila. In El descubrimiento de los vettones. Los materiales del Museo Arqueológico Nacional. Catálogo de la exposición; Institución Gran Duque de Alba: Ávila, Spain, 2005; pp. 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Lorrio, A.J. El descubrimiento de los vettones. Los materiales del Museo Arqueológico Nacional. Catálogo de la exposición; Institución Gran Duque de Alba: Ávila, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Barril Vicente, M.M.; Galán Domingo, E. (Eds.) Ecos del Mediterráneo: El mundo ibérico y la cultura vettona; Institución Gran Duque de Alba: Ávila, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-Sanchís, J.R. Vettones. Pastores y guerreros de la Edad del Hierro; Museo Arqueológico Regional: Madrid, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Zapatero, G. Gentes de la Edad del Hierro en el occidente de Iberia: Agenda actual e investigación futura. In Castros y Verracos. Las Gentes de la Edad del Hierro en el Occidente de Iberia. (Reunión Internacional Castros y Verracos. Ávila 9-11 de noviembre de 2004, Palacio de los Serrano); Ruiz Zapatero, G., Álvarez-Sanchís, J.R., Eds.; Institución Gran Duque de Alba: Ávila, Spain, 2011; pp. 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Fabián García, J.F. Guía de la Ruta de los Castros Vettones de Ávila y su Entorno; Institución Gran Duque de Alba: Ávila, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ser Quijano, G. (Ed.) Ruta de Castros y Verracos de Ávila, Salamanca, Miranda do Douro, Mogadouro y Penafiel; Institución Gran Duque de Alba: Ávila, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Zapatero, G.; Álvarez-Sanchís, J.R. (Eds.) Castros y Verracos. Las Gentes de la Edad del Hierro en el Occidente de Iberia. (Reunión Internacional Castros y Verracos. Ávila 9-11 de noviembre de 2004, Palacio de los Serrano); Ruiz Zapatero, G.; Álvarez-Sanchís, J.R. (Eds.) Institución Gran Duque de Alba: Ávila, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-Sanchís, J.R.; González-Tablas, F.J. Vettonia. Cultura y Naturaleza; Institución Gran Duque de Alba: Ávila, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- López García, J.P. MASAV (Museo Abierto Sierra de Ávila y Valle Amblés). Propuesta para la supervivencia de los paisajes culturales de la provincia de Ávila a partir de su patrimonio histórico y arqueológico. In Investigar el Pasado Para Entender el Presente. Homenaje al Profesor Carmelo Luis López; Institución Gran Duque de Alba: Ávila, Spain, 2019; Volume 2, pp. 365–384. [Google Scholar]

- Castelo Ruano, R.; González Casarrubios, C. Monitoreo, diagnóstico y evaluación de los efectos de la divulgación en los sitios patrimoniales. Castros vettones de las provincias de Ávila y Salamanca: Las Cogotas, Mesa de Miranda, El Freíllo, Las Merchanas y Yecla la Vieja. In Proyectando lo Oculto. Tecnologías LiDAR y 3D Aplicadas a la Arqueología de la Arquitectura Protohistórica; Berrocal-Rangel, L., Ed.; Anejos 5 CUPAUAM: Madrid, Spain, 2021; pp. 245–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maté-González, M.A.; Rodríguez-Hernández, J.; Sáez Blázquez, C.; Troitiño Torralba, L.; Sánchez-Aparicio, L.J.; Fernández Hernández, J.; Herrero Tejedor, T.R.; Fabián García, J.F.; Piras, M.; Díaz-Sánchez, C.; et al. Challenges and Possibilities of Archaeological Sites Virtual Tours: The Ulaca Oppidum (Central Spain) as a Case Study. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benet, N.; Martín Valls, R. Actuar sobre el patrimonio cultural: Veinte años en Yecla la Vieja (Salamanca). In Actas. Puesta en Valor del Patrimonio Arqueológico en Castilla y León; Val Recio, J., Escribano Velasco, C., Eds.; Junta de Castilla y León: Salamanca, Spain, 2004; pp. 191–206. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-Sanchís, J.R.; Torre Echávarri, J.I. Enseñar el pasado al público: Aulas arqueológicas y centros de interpretación. In V Simposio Sobre Celtíberos: Gestión y Desarrollo; Burillo Mozota, F., Ed.; Fundación Segeda-Centro de Estudios Celtibéricos: Zaragoza, Spain, 2007; pp. 137–147. [Google Scholar]

- Falquina, A.; Marín, C.; Rolland, J. El polémico traslado de los verracos de Villanueva del Campillo (Ávila). Rev. Cult. De Ávila Segovia Y Salamanca 2005, 67, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Zapatero, G.; Salas Lopes, N. Los vettones hoy: Arqueología, identidad moderna y divulgación. In Arqueología Vettona. La Meseta Occidental en la Edad del Hierro; Álvarez-Sanchís, J.R., Ed.; Museo Arqueológico Regional: Alcalá de Henares, Spain, 2008; pp. 408–423. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Zapatero, G. Arqueología e identidad: La construcción de referentes de prestigio en la sociedad contemporánea. Arqueoweb 2002, 4, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Zapatero, G. La construcción de un referente de prestigio: El celtiberismo en la Soria contemporánea. Arevacón (Boletín De La Asoc. De Amigos Del Mus. Numantino) 2005, 25, 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Andreu, M. Constructing identities through culture: The past in the forging of Europe. In Cultural Identity and Archaeology: The Construction of European Communities; Graves Brown, P., Jones, S., Gamble, C., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1996; pp. 48–61. [Google Scholar]

- Fewster, K.J. The role of agency and material culture in remembering and forgetting: An ethnoarchaeological case study from central Spain. J. Mediterr. Archaeol. 2007, 20, 89–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorrio Alvarado, A.J.; Ruiz Zapatero, G. Un modelo de difusión para la Edad del Hierro: La presentación pública de yacimientos. In Musealizando la Protohistoria Peninsular; Munilla, G., Ed.; Edicions de la Universitat de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2019; pp. 13–44. [Google Scholar]

- Grima, R. Presenting archaeological sites to the public. In Key Concepts in Public Archaeology; Moshenska, G., Ed.; UCL Press: London, UK, 2017; pp. 73–92. [Google Scholar]

- Kajda, K.; Marx, A.; Wright, H.; Richards, J.; Marciniak, A.; Salas Rossenbach, K.; Pawleta, M.; van den Dries, M.H.; Boom, K.; Guermandi, M.P.; et al. Archaeology, Heritage, and Social Value: Public Perspectives on European Archaeology. Eur. J. Archaeol. 2018, 21, 96–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Sanchís, J.R.; Guichard, V.; Moore, T. Las primeras ciudades de Europa. Un proyecto para mejorar la gestión de los paisajes culturales. Red.Escubre. Boletín De Not. Científicas Y Cult. 2016, 81, 8–10. Available online: https://www.ucm.es/redescubre-81-del-2-al-15-de-octubre-de-2016 (accessed on 25 November 2022).

- Álvarez-Sanchís, J.R.; Rodríguez-Hernández, J. Engagement strategies for Late Iron Age oppida in North-Central Spain. Complutum 2016, 27, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, T.; Tully, G. Connecting landscapes: Examining and enhancing the relationship between stakeholder values and cultural landscape management in England. Landsc. Res. 2018, 43, 769–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, T.; Tully, G. Exploring archaeologys place in participatory European cultural landscape management: Perspectives from the REFIT project. In A Research Agenda for Heritage Planning; Stegmeijer, E., Veldpaus, L., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maté-González, M.Á.; Sáez Blázquez, C.; Carrasco García, P.; Rodríguez-Hernández, J.; Fernández Hernández, J.; Vallés Iriso, J.; Torres, Y.; Troitiño Torralba, L.; Courtenay, L.A.; González-Aguilera, D.; et al. Towards a Combined Use of Geophysics and Remote Sensing Techniques for the Characterization of a Singular Building: “El Torreón” (the Tower) at Ulaca Oppidum (Solosancho, Ávila, Spain). Sensors 2021, 21, 2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Hernández, J.; González-Álvarez, D. Luna Celta historical re-enactment, central Spain: Iron Age alive! Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2021, 27, 134–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Álvarez, D.; Alonso-González, P.; Rodríguez-Hernández, J. Historical Reenactments in Spain: A Critical Approach to Public Perceptions of the Iron Age and Roman Past. In Historical Reenactment: New Ways of Experiencing History; Carretero, M., Wagoner, B., Perez-Manjarrez, E., Eds.; Berghahn Books: New York, NY, USA; Oxford, UK, 2022; pp. 49–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Zapatero, G. Casas, “hogares” y comunidades: Castros y oppida prerromanos en la Meseta. In Más allá de las Casas. Familias, Linajes y Comunidades en la Protohistoria Peninsular; Rodríguez, A., Pavón, I., Duque, D.M., Eds.; Universidad de Extremadura: Cáceres, Spain, 2018; pp. 327–361. [Google Scholar]

- Ballart Hernández, J. Paisaje y Patrimonio. Un Mismo Destino a Compartir; JAS Arqueología: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Guichard, V. Bibracte: Le paysage au cœur du projet de site = Bibracte: Die Landschaft im Zentrum des Projekts der archäologischen Stätte. In Paysages Entre Archéologie et Tourisme = Landschaften Zwischen Archäologie und Tourismus; ArchaeoTourism: Biel-Bienne, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 102–113. [Google Scholar]

- Dietler, M. “Our ancestors the Gauls”: Archaeology, ethnic nationalism, and the manipulation of Celtic identity in modern Europe. Am. Anthropol. 1994, 96, 584–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Andreu, M. Archaeology and nationalism in Spain. In Nationalism, Politics, and the Practice of Archaeology; Kohl, P.L., Fawcett, C., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995; pp. 39–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Zapatero, G. Celts and Iberians: Ideological manipulations in Spanish archaeology. In Cultural Identity and Archaeology. The Construction of European Communities; Graves-Brown, P., Jones, S., Gamble, C., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1996; pp. 179–195. [Google Scholar]

- Marín Suárez, C.; González Álvarez, D.; Alonso González, P. Building nations in the XXI century. Celticism, nationalism and archaeology in Northern Spain: The case of Asturias and León. In Archaeology and the (de)Construction of National and Supra-national Polities; Ríagáin, R.O., Popa, C.N., Eds.; Archaeological Review from Cambridge 27: Cambridge, UK, 2012; pp. 11–31. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Rio Declaration on Environment and Development. 1992. Available online: https://daccess-ods.un.org/tmp/1683715.43288231.html (accessed on 25 November 2022).

- UNECE. Aarhus Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-Making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters. 1998. Available online: https://unece.org/DAM/env/pp/documents/cep43e.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2022).

- Council of Europe. Faro Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society. 2005. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/1680083746 (accessed on 25 November 2022).

- Guichard, V. An example of integrated management of an heritage site: Bibracte—Mont Beuvray (Burgundy, France). In Less More Architecture Design Landscape. Le vie dei Mercanti. X Forum Internazionale di Studi; Gambardella, C., Ed.; La Scuola di Pitagora Editrice: Napoli, Italy, 2012; pp. 1220–1230. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Cacho, S. Criterios Para la Elaboración de Guías de Paisaje Cultural; Consejería de Cultura y Patrimonio Histórico. Junta de Andalucía: Sevilla, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso González, P.; González-Álvarez, D.; Roura-Expósito, J. ParticiPat: Exploring the Impact of Participatory Governance in the Heritage Field. PoLAR: Political Leg. Anthropol. Rev. 2018, 41, 306–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyrlitsias, C.; Christofi, M.; Michael-Grigoriou, D.; Banakou, D.; Ioannou, A. A virtual Tour of a Hardly Accessible Archaeological Site: The Effect of Immersive Virtual Reality on User Experience, Learning and Attitude Change. Front. Comput. Sci. 2020, 2, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín Suárez, C. Astures y Asturianos. Historiografía de la Edad de Hierro en Asturias; Toxosoutos: Noia, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Chapa, T. La percepción de la infancia en el mundo ibérico. Trab. De Prehist. 2003, 60, 115–138. [Google Scholar]

- Prados Torreira, L. Y la mujer se hace visible. Estudios de género en la arqueología ibérica. In Arqueología del género: 1.er encuentro internacional en la UAM; Prados Torrerira, L., López Ruiz, C., Eds.; Universidad Autónoma de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 2008; pp. 225–250. [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo Peraile, I. Aristócratas, ciudadanas y madres. Imágenes de mujeres en la sociedad ibérica. In Política y Género en la Propaganda en la Antigüedad. Antecedentes y Legado; Domínguez Arranz, M.A., Ed.; Trea: Gijón, Spain, 2013; pp. 103–128. [Google Scholar]

- Baquedano, I.; Arlegui, M. La mitad de la Edad del Hierro. Mujeres y silencios. In Tejiendo pasado II. Patrimonios invisibles. Mujeres portadoras de memoria; Torija, A., Baquedano, I., Eds.; Consejería de Cultura, Turismo y Deportes de la Comunidad de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 2020; pp. 61–102. [Google Scholar]

- Liceras Garrido, R. Género y edad en las necrópolis de la meseta norte durante la Edad del Hierro (siglos VI-II a. n. e.). Trab. De Prehist. 2021, 78, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley-Price, N. The reconstruction of ruins: Principles and practice. In Conservation: Principles, Dilemmas and Uncomfortable truths; Richmond, A., Bracker, A., Eds.; Elsevier-Butterworth Heinemann: London, UK, 2009; pp. 32–46. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Hernández, J.; Álvarez-Sanchís, J.R.; Aparicio-Resco, P.; Maté-González, M.Á.; Ruiz-Zapatero, G. Reconstrucción virtual en 3D del “Torreón” del oppidum de Ulaca (Solosancho, Ávila): Mucho más que una imagen. Arqueol. De La Arquit. 2021, 18, e123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansilla Castaño, A.M. La Divulgación del Patrimonio Arqueológico en Castilla y León: Un Análisis de los Discursos. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 22 June 2004. Available online: https://eprints.ucm.es/id/eprint/5133/ (accessed on 25 November 2022).

- González Álvarez, D.; Alonso González, P. The ‘Celtic-Barbarian Assemblage’: Archaeology and Cultural Memory in the Fiestas de Astures y Romanos, Astorga, Spain. Public Archaeol. 2013, 12, 155–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitálišová, K.; Borseková, K.; Bitušíková, A.; Visiting the Margins. INnovative CULtural ToUrisM in European Peripheries. Available online: https://www.heritageresearch-hub.eu/app/uploads/2022/06/INCULTUM-D4.1-Report-on-participatory-models.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2022).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).