Abstract

Relatively little is known about stained glass windows in England predating c. 1170; however, art-historical evaluation by Caviness (1987) argued that four figures from the “Ancestors series” of Canterbury Cathedral, usually dated to the late 12th and early 13th century, in fact date earlier (c. 1130–1160). This would place them amongst the earliest stained glass in England, and the world. Building on our previous work, we address Caviness’s hypothesis using a methodology based upon analysis of a few, well-measured heavy trace elements and a 3D-printed attachment for a pXRF spectrometer that facilitates in situ analysis. The results confirm two major periods of “recycling” or re-using medieval glass. The first is consistent with Caviness’s argument that figures predating the 1174 fire were reused in the early 13th century. The results suggest that in addition to figures, ornamental borders were reused, indicating the presence of more early glass than previously thought. In the second period of recycling (1790s), surviving figures from the Ancestors series were removed and adapted into rectangular panels for insertion into large Perpendicular-style windows elsewhere in the cathedral. The results show that the glasses used to adapt the panels to a rectangular shape were broadly contemporary with the glasses used to glaze the original Ancestors windows, again representing a more extensive presence of medieval glass in the windows.

1. Introduction

Large windows with complex figurative decoration, comprising small pieces of colored glass held in position by lead cames, are characteristic of many of the great medieval cathedrals of Europe. The present paper is concerned with some of the earliest of these stained glass windows in England.

The precursors to stained glass were simple, unpainted colored windows, with recorded examples in churches dating back to at least the fifth and sixth centuries that were based upon natron glass, which is widely understood to have been made in the eastern Mediterranean in the Roman tradition [1,2,3,4,5]. From about the eighth century, ecclesiastical window glass based upon potash-rich forest ash became prevalent [6,7,8], and while the beginnings of the use of grisaille (a grey-, black- or brown-monochrome pigment that was painted and fired onto the surface of the glass; 1 in Appendix A) is not precisely known, fragments of grisaille-painted glass survive from the sixth, eighth and eleventh centuries [8,9,10,11]; the earliest extant panels date to the twelfth century (the Prophets from Augsburg Cathedral, amongst the oldest known stained glass windows in Europe, date to sometime after 1132) [11,12]. The development of the Gothic style in church architecture (beginning in the Île-de-France, in the second quarter of the twelfth century) with its emphasis on larger windows for admitting more light, and a dramatic increase in ecclesiastical construction, brought about an intense demand for stained glass windows [13,14,15,16].

In England, there is a dearth of information about stained glass windows predating c. 1170 [17], and the use of early stained glass is not well understood. However, Madeline Caviness [18] suggested that some figures from the Ancestors series, from the late twelfth century clerestory windows of Canterbury Cathedral, are in fact Romanesque in style and had been adapted from previously existing/damaged windows for inclusion in this series. She proposed a date of c. 1130–1160, which would place them amongst the earliest stained glass windows in England, and the world. Until now, the evidence for this has been largely based upon compelling art-historical arguments. Here, we present the results of a scientific study designed to test her hypothesis, using non-invasive, in situ chemical analysis.

The architectural context of medieval stained glass windows poses a major obstacle to answering questions pertaining to their history through chemical analysis. Unless major conservation works are undertaken that include the dismantling of the window and the removal of the glass pieces from the lead cames holding them together, sampling the glass for analysis is impossible. Furthermore, data generated through the application of standard non-invasive methods such as portable X-ray fluorescence (pXRF) can be severely compromised by the presence of weathered layers and geometrical problems caused by the lead cames. Previous applications of this technique to window glass have therefore tended to focus on distinguishing broad compositional types of post-medieval glass (which is less susceptible to deterioration and where the cames are less of an obstacle), which are related to the period of production or intervention (e.g., high potash, HLLA, kelp ash, soda-lime-silica, etc.) [19,20,21,22,23] (see also [24]), rather than more detailed investigation of window production.

In our previous work on dismounted windows [25], we have shown that in principle it should be possible to use a pXRF spectrometer to analyze medieval windows using a few, well-measured trace elements, which had previously been used to classify post-medieval glass by Dungworth [19]. More recently [26], we demonstrated the use of a simple, 3D-printed attachment (“WindoLyzer”) for a pXRF spectrometer that enabled the application of the trace element approach to glass windows that are encased in lead cames and mounted vertically, emulating the in situ situation, to identify different sources of medieval glass. Here, we use the trace element approach together with the WindoLyzer to distinguish groups of original medieval glass and to address a question of historical interest, viz. the hypothesis of Caviness. In addition, the investigation sheds important light on the practice of “recycling” windows between locations in a building at a relatively early date, as well as pointing to a change in the source of glass at Canterbury around the end of the 12th century.

The Ancestors Windows of Canterbury Cathedral

The clerestory windows at Canterbury Cathedral once comprised the longest known series depicting the ancestors of Christ, with 86 figures originally, of which 43 survive [27,28]. The figures were originally portrayed in pairs, one over the other (e.g., Figure 1), in the upper windows (the clerestory) circling the choir, the northeast and southeast transepts, the presbytery, and the Trinity Chapel at the eastern end, such that the first pair (God and Adam) was facing the final pair (Mary and Jesus) across the west end of the choir.

Figure 1.

Before 1790, the Ancestor figures were originally positioned in pairs, one over the other, in the upper windows (clerestory) of Canterbury Cathedral. Two of the extant figures (pictured here), which are now housed in the Great South Window at Canterbury Cathedral (Figure 2), are seen displayed as they would have been originally in an exhibition in the Canterbury Chapter House in 2015.

The Ancestors series in the clerestory windows were created as part of the larger construction works that followed a devastating fire in 1174, which destroyed the previous choir (completed by Prior Conrad in 1126 [17]). Construction of the new choir, transepts, presbytery and Trinity Chapel began in 1175 and finished in 1184 [17,27,29]. Previous study [29] suggests that the clerestory windows of the newly constructed building were initially glazed and installed while keeping pace with the construction of the cathedral and taking advantage of the scaffolding already in place, until 1180. This group includes the windows of the choir, transepts and presbytery, the parts of the new cathedral that were completed in time for the Easter services that year. After this, while glazing of the lower windows may have proceeded at a faster pace (particularly in the 1180s [30]), the glazing of the clerestory no longer kept pace with the construction works and in the early 13th century, it was periodically interrupted by local political upheavals, particularly the disputes between the archbishop and the monks of Canterbury in 1188–1201 and 1207–1213 [29,30]. Caviness noted that the colored glasses of these two production phases (2 in Appendix A) differed in tone and hue [27], which suggests chemically distinct glasses may been used. Four of the figures from the end of the second phase, however, were identified as stylistically closer to an earlier period [18]. This observation led Caviness to hypothesize that they had been made for the previous choir, survived the 1174 fire, and then adapted for inclusion in the new building in the early 13th century [18]. The central aim of the present research was to examine this hypothesis, by consideration of three phases of glazing the clerestory windows: Phase 1 (1176–1180), during which the glazing kept pace with the construction works; Phase 2 (1184–1220), during which the glazing was carried out after the construction was completed (with particular focus on the later period of 1213–1220); and the possible panels from an earlier glazing campaign carried out before the 1174 fire, Phase 0 (c. 1130–1160).

Already by the 1770s, about half of the ancestors were missing, as William Gostling listed only 42 surviving figures [27]; a 43rd (Cosam) has since been rediscovered. In the 1790s, all but seven of the extant Ancestor figures (3 in Appendix A) were removed from their medieval situation in the clerestory, separated from their ornamental borders, and adapted into rectangular panels to fill the great Perpendicular windows in the cathedral’s southwest transept and west end (e.g., Figure 2). The glass used in this intervention will be identified and characterized for better understanding of conservation practice during this period.

Figure 2.

The Great South Window of Canterbury Cathedral. The figures portrayed in the main lights were originally part of the clerestory windows, in a series depicting the ancestors of Christ. They were removed from their original position, adapted and installed in this window in the 1790s. Courtesy Dean and Chapter of Canterbury.

A timeline of the major phases in the production and relocation of the Ancestor figures is given in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Timeline showing key dates and phases of production and restoration in the life history of the Ancestor figures in the clerestory windows of Canterbury Cathedral. Phase 0 refers to the glazing of the earlier choir, which was destroyed by a fire in 1174. Phase 1 refers to the period of glazing that kept pace with the construction of the cathedral in 1176–1180. Phase 2 refers to the glazing that no longer kept pace with construction works.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Panels under Study

The stonework of the Great South Window (GSW, Figure 2), one of the two great Perpendicular windows now home to the surviving Ancestor figures from the clerestory, recently underwent seven years of restoration, culminating in November 2016, providing a rare opportunity for both specialists and the public to examine the stained glass panels more closely. Three figures from the GSW were selected for the present study (Figure 4).

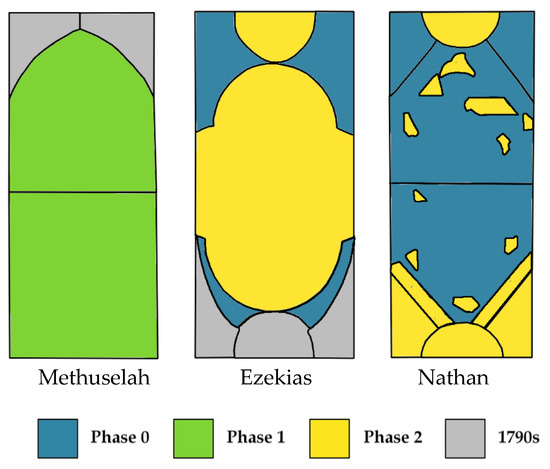

Figure 4.

Three panels from the Ancestors of Christ series, originally in the clerestory windows of Canterbury Cathedral and now in the Great South Window, were selected for this study: (a) Methuselah, from Phase 1; (b) Ezekias, from Phase 2; (c) Nathan, one of the panels that Caviness suggested contains a Romanesque figure. Panel images reproduced courtesy of the Dean and Chapter, Canterbury Cathedral.

The figure of Nathan (panels 12e and 13e, Figure 4c) is one of the four figures identified by Caviness [18] as possible survivors of the 1174 fire that would have been originally produced during Phase 0. She argued that these figures were adapted for the clerestory window openings and installed during the latter part of Phase 2, c. 1213–1220.

For comparison, one figure from Phase 1 and one from Phase 2 were chosen to characterize the glass in use at the beginning and end of the post-fire glazing campaign. The figure of Methuselah (panels 2e and 3e, Figure 4a), from Phase 1, has been dated to about 1178–1179. The figure of Ezekias (panels 7c and 8c, Figure 4b) was installed in the clerestory contemporaneously (c. 1213–1220) to the possible Phase 0 figures, including Nathan.

2.2. Analytical Methods

Although the panels were removed from the GSW, the glass pieces were not removed from the lead cames that hold them together. It was therefore impossible to invasively sample the glass for chemical analysis, and analysis had to be carried out under in situ conditions. Previous work has successfully used pXRF to study in situ window glass [19,21,23,25,26,31], which in many ways is a good candidate for analysis by the technique, being relatively homogeneous and flat. However, specific obstacles face the analyst studying medieval stained glass that require special consideration, specifically the susceptibility of medieval glass to deterioration, and the interference of the protruding lead cames that hold the glass pieces together.

Medieval stained glass is highly prone to deterioration, both due to its atmospheric exposure and the relatively low stability of its low silica, high alkali composition [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41]. The glass may experience leaching, the process by which modifying ions are drawn out from the surface layer of the glass and replaced by the diffusion of hydrogen-containing species from rainwater and indoor humidity, resulting in a layer of altered composition [37,41,42,43,44]. Corrosion crusts can also form when the water evaporates and leaves behind sulfates, carbonates, chlorides and nitrates of the alkalis and alkaline earths, as well as organic compounds [41,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53]. Furthermore, the presence of grisaille (typically high in lead and iron or copper [9,54,55,56,57]) and yellow stain (composed of a silver compound and sometimes copper [58,59,60]), and the tendency of some metals such as lead to diffuse into the surrounding weathered glass [61], also contribute to an altered composition on the surface of the glass. The effect of deterioration (and decorative grisaille painting and yellow stain) on surface analyses of medieval window glass by pXRF has been addressed elsewhere with the result that, where visible corrosion deposits have been removed or are absent, heavy trace elements Rb, Sr and Zr can be well measured and can serve as proxies for major elements to distinguish not only major compositional categories [19], but also different recipes of forest glass from the same period [25].

The protrusion of the lead cames in in situ panels prevents the placement of the spectrometer directly on the surface of the glass, creating distance between the detector and sample that will vary between analyses. In a recent paper, we offered a simple, inexpensive and adaptable solution in the form of a 3D-printed attachment for a pXRF spectrometer (a window analyzer, or WindoLyzer) that maintains a constant distance between the spectrometer and sample, bypassing the lead cames [26]. The WindoLyzer was printed using a material composed of very light elements (polylactic acid, C3H4O2), which means it does not interfere with analysis but also does not stop scattered X-rays and can pose increased radiation risks; after tests with a Geiger counter, it is recommended that the analyst either stand directly behind the spectrometer during operation or, if using the spectrometer for tabletop analyses, use a lead shield for personal protection (for further information, see [26]). Tests indicated that the use of this fixed-distance attachment retains a high degree of precision in the resulting data and the accuracy can be corrected through empirical calibration, at least to the extent that any surface analysis can be considered quantified. In recognition of the valid concerns regarding the use of surface analyses as fully quantified data representative of the bulk composition [26], the graphs in this paper are labelled “s.a. ppm” (surface analysis ppm).

The panels were analyzed while secured to a vertical light box. The analyses were carried out using the Innov-X/Olympus Delta Premium DP6000CC pXRF [62] with the attached WindoLyzer 5 (i.e., with an added working distance of 5 mm between the spectrometer’s face and the glass surface), using the built-in “Soils” mode over three settings (so-called “beams”) with 20 s total analytical time. Beam 1 operated for 10 s at 40 kV and 89 μA with a 0.15 mm copper filter (optimized for heavier elements with higher energy characteristic x-rays), Beam 2 operated for 5 s at 40 kV and 52 μA with a 2 mm aluminum filter (optimized for transition metals and similar); and Beam 3 operated for 5 s at 15 kV and 60 μA with a 0.1 mm aluminum filter (optimized for lighter elements). Empirical calibrations based upon the analysis of several matrix-matched standards, including Corning A and B [63,64,65], AD1-3 [66], standards prepared by Pilkington for Roy Newton [67], NIST 612 and 614 [68], and Society of Glass Technology standard 11 [69], were applied to the data (see [26]). Corning D was used as a secondary standard, and accuracy and precision of the data are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

The mean of repeated analyses (n = 39) of Corning D, compared to the accepted concentrations [63,64,65] of Rb, Sr and Zr in parts per million, with relative accuracy and precision (RSD) reported.

3. Results

The analytical method allowed the identification of the components responsible for glass color; however, they are not key concerns of the present paper, which is concerned with the base glasses. It is pertinent to observe, however, that colorants were consistent across the panels and with previous detailed investigations of colorant technology in medieval glass [70,71,72].

3.1. Baseline Characterisation of the Glass Used in Phase 1 and Phase 2

The figures of Methuselah (Phase 1, c. 1178–1179) and Ezekias (Phase 2, c. 1213–1220) were both originally positioned in the upper portion of the arched clerestory windows (Figure 5), thereby necessitating significant modification to transform them into rectangular panels upon the move to the GSW in the 1790s. Decorative aspects at the extremities of the panels were disturbed or entirely re-glazed in the late 18th century. Therefore, only the glass of the figures and immediate surroundings (i.e., within the archway above Methuselah and the area inside the quatrefoil in the Ezekias panels) were included in the initial baseline characterization of the glass types used during Phases 1 and 2.

Figure 5.

Outlines of the original clerestory windows that housed the panels under study, with superimposed images of the panels as they are today. Outlines are based on those provided in a catalogue of the Canterbury Cathedral windows [27]. Panel images reproduced courtesy of the Dean and Chapter, Canterbury Cathedral.

The two figures are composed of a similar range of colors (though the hues do vary, see the detailed visual and stylistic analysis of Caviness [27]): white, blue (dark and light), green, red, yellow, and three shades of purple/pink colors (murrey, a purplish-brown color; pink; and a very pale pink used for flesh tones). Most colors are found in both figures, excluding light blue (Methuselah’s shoes) and pink (Ezekias’ footstool).

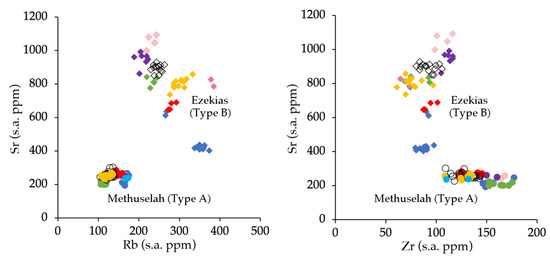

The trace element concentrations of the glass as analyzed by handheld pXRF are in general terms consistent with previously published trace element data for medieval stained glass (e.g., [7,25,37,73,74]). However, the glasses used to glaze the two figures have distinct chemical characteristics (Figure 6). The earlier (Phase 1) Methuselah panels are glazed with glass containing lower Rb and Sr contents and higher Zr concentrations (“Type A” for the purposes of this paper) than the glasses of the later (Phase 2) Ezekias panels (“Type B”). Several blue glass pieces and one yellow from the background of the Methuselah figure are compositional outliers and possibly not original to the panel; while they appear very old and have corrosion patterns indicating they have been in their present shape for a long time, they are visibly more deteriorated, indicating either different chemical composition or different environmental exposure. Many are identified in past conservation records as infills, probably for this reason. They have therefore been excluded from the baseline characterization of Phase 1 glass.

Figure 6.

Trace element contents of the Type A glass (Methuselah, c. 1178–1179) and Type B glass (Ezekias, c. 1213–1220). The colors of the data points correlate to the color of the glass, including blue, light blue, red, yellow, green, murrey (shown as purple), pink, flesh-pink (i.e., very pale pink), and white (shown with black outlines).

The Rb and Sr contents of Type A glass, in the Phase 1 panels (Methuselah), are clustered by color, but these clusters are overlapping and overall very consistent with each other, with a relatively narrow range of compositions (100–175 ppm Rb and 200–300 ppm Sr). On the other hand, the Type B glass colors, from the Phase 2 panels (Ezekias), show a wider variability in Rb and Sr contents (190–390 ppm Rb and 400–1100 ppm Sr), with different colors forming distinct clusters (Figure 6).

3.2. Characterisation of the Possible Phase 0 Panels (Nathan)

The Nathan panels depict one of the four figures identified as possibly painted during Phase 0 (c. 1130–1160, predating the 1174 fire), although they were installed into the clerestory windows during Phase 2 (at a similar date to the Ezekias panels, c. 1213–1220). Therefore, similarities and dissimilarities between the glass used in the Nathan and Ezekias panels are particularly relevant to the investigation of the origins of the Nathan figure.

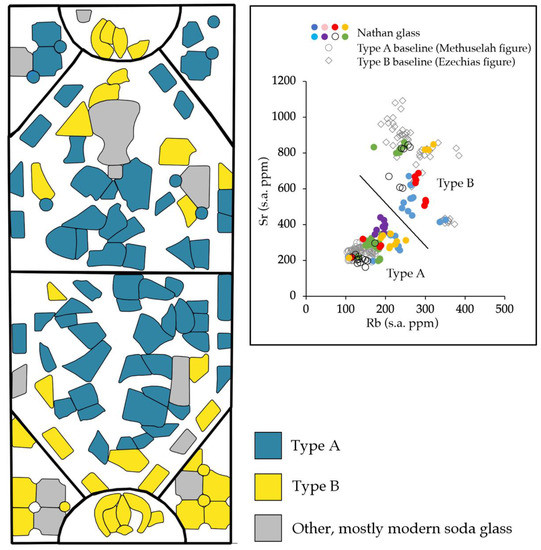

The Nathan panels comprise both Type A and Type B glass (Figure 7): the figure, his immediate surroundings, some of the green border and the upper part of the ornamental frame are glazed in Type A glass, while Type B glass was used to glaze miscellaneous pieces from the background surrounding Nathan, his hat, and parts of the frame concentrated at the base of the panel. Both rosettes (at the top and bottom of the panel) are glazed with Type B glass.

Figure 7.

Image showing the distribution of Type A and Type B glass in the Nathan panels. A distinction is made between Type B glass consistent with the Ezekias panels (glazed for the clerestory at a similar time) and other Type B glass. Below, a scatterplot showing the Nathan glass (circles) against the composition of the Type A and Type B glass pieces from Methuselah (Phase 1) and Ezekias (Phase 2) panels.

The Type B glass pieces used to fill in the background and peripheral areas in the Nathan panels are highly consistent in composition to the baseline Type B glass used to glaze the Phase 2 figure of Ezekias (most of the glass pieces cluster with the same colors in the Ezekias panels, suggesting the Type B parts of the Nathan panels may have been completed around the same time.

The white Type A glasses from the Nathan panels map closely onto the baseline Type A glasses from the Phase 1 Methuselah panel (Figure 7). However, most Type A colored pieces from Nathan show a shift to higher Sr or Rb contents relative to the Methuselah cluster. Thus, while the Nathan Type A glasses are closely related to those used to glaze Methuselah in 1178–1179, they are not identical, which makes the passage of some period of time between the production of the glass used in each panel more likely.

3.3. Characterisation of Areas Disturbed during the 1790s

As illustrated by Figure 5, the panels would have required varying degrees of adaptation to move them from the clerestory window openings to their current rectangular forms in the GSW. The decorative frames outside the figures of Methuselah and Ezekias, both of which were originally at the apex of an arched window, are known to have been disturbed during the 1790s with portions added in order to make them rectangular. In the clerestory, the Nathan figure was positioned within a canted square (or a “diamond” shape), and the green border at the sides of the figure was adjusted to its present form in the 1790s intervention.

The decorative frames outside the Methuselah and Ezekias figures predominantly contain both Type A and Type B glass as well as a few other pieces with other medieval compositions. None of the glass pieces analyzed were of kelp ash composition, which was the type of flat glass manufactured in England in the late eighteenth century [19]. Several pieces of glass made from synthetic soda (produced in England post-1835 [19]) were identified as replacement glass inserted in the panels during later conservation interventions.

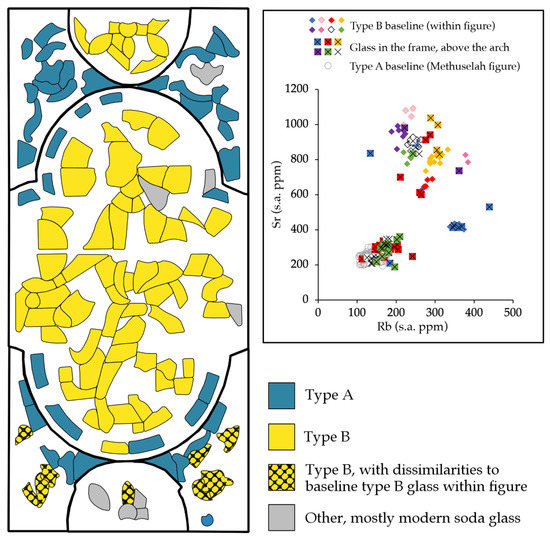

The archway above the figure of Methuselah (Phase 1; Figure 8), the entire of which appears to have been added in the 1790s (Figure 5), contains both Type A and Type B glass. The four identified pieces of Type B glass were red; the Type A glasses are green, red, white and yellow pieces that are mostly characterized by Rb contents higher than the same Type A colors used within the figure.

Figure 8.

Image showing the use of both Type A and Type B glass in the archway above Methuselah, which would have been added to the figure during the 1790s move to the GSW. Below, a scatterplot showing the glass above the archway (marked with an “X”) compared to the original glass of the figure (circles). All but two of the Type A glass have higher Rb than the glass in the figure, and some of the red pieces are Type B.

The frame surrounding Ezekias (Phase 2), which would have been disturbed with parts added in the 1790s to square off the original pointed arch at the top of the panels (Figure 5), is also composed of both Type A and Type B glass (Figure 9). The majority of the frame contains Type A glass, which when compared to the Type A glass found in the Methuselah panels (Phase 1) and the Nathan panels (Phase 0), is compositionally closer to the Nathan glass. The Type B glasses in the Ezekias panels (outside the quatrefoil) are concentrated in the half rosette above the figure and in the bottom corners of the panel; the glass pieces in the rosette are consistent in composition with the same colors used inside the figure, while the glass pieces in the bottom corners show minor dissimilarities.

Figure 9.

Image showing the distribution of Type A and Type B glass in the frame around Ezekias. An arched frame composed of the Type A glass is visible upside-down; the upper rosette is consistent with the original glass used to glaze Ezekias; and at the base, Type B glass pieces were used to alter the figure to a rectangular shape during the 1790s move to the GSW. Below, a scatterplot showing the glass of the frame (marked with an “X”) compared to the original glass of the figure (rhombus).

4. Discussion

4.1. Glass Supply to Canterbury Cathedral

A meta-analysis of chemical data has shown that glass made in the three major regions of medieval glass production in northern Europe (Normandy and northwest France, the Rhine and its environs, and Bohemia and central Europe) can be distinguished by their major element characteristics [75], but as of yet there is not enough data available to characterize these regional industries by their trace elements. However, trace elements may be used to gain similar information regarding the production and provenance of medieval forest glass. The plant species, the bioavailability of elements in the underlying substratum, the mineralogy of the sand raw material, and technological choices all affect the elemental composition of the glass [7,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87]. Therefore, significant differences in trace element composition, as observed between the Type A and Type B glasses in the Canterbury clerestory windows, are attributed to different sources, with chemical characteristics determined by a combination of regional availability of plant species, local geology, access to different sand sources, and local technological traditions.

The figures of Methuselah and Ezekias are the only parts of the panels that can be confidently attributed to Phase 1 and Phase 2, respectively, as the frames (the arched canopy above Methuselah, and the area outside the quatrefoil around Ezekias) were either disturbed or entirely added during the 1790s. The exclusive use of Type A glass (higher Rb and Sr, lower Zr; see again Figure 6) in the Phase 1 figure (Methuselah), and of Type B glass in the Phase 2 figure (Ezekias), suggests a change in glass source at Canterbury sometime in the late 12th or early 13th century. An alternative interpretation would be that the transition between Type A and Type B was not a chronological one and that the two glass types were used concurrently. While constraints on our study have allowed for the analysis of only three panels, it bears emphasizing that visual examination of the entire Ancestor series showed subtle but consistent differences in the shades and hues of the glass colors used in Phase 1 and Phase 2 [27], which initially led us to suspect that chemically different glasses were used in the two phases of production. The lack of mixing of the glass types in the Phase 1 and Phase 2 figures strongly supports the view that the two glass types were not in use at the same time. If they were, we would expect to see mixing of types (for example, Type A blues used in a panel alongside Type B reds). Together these observations suggest that a chronological change is the most likely explanation and we have found no evidence in support for the alternative.

The spread of compositions observed in the two glass types also suggests there might have been a difference in the organization of production technology. The Type A glasses used in the Phase 1 (Methuselah) panels have a narrow range of compositions and the trace element concentrations of the different colors, reflective of the base glass recipe, are highly consistent. This suggests that the glass colors were not only produced and sold together, but that the colors were made from a common base glass, which was then divided for coloring, a practice identified elsewhere (see [88]). Conversely, the spread of compositions found in the Type B glasses used to glaze the Phase 2 Ezekias figure, and the clustering of glass pieces of the same color, suggests that the different colors were made separately and from scratch rather than from a common base glass. Without major element information, it is not currently possible to confirm whether the range of Rb and Sr contents in the Type B glass reflects deliberate alterations to a recipe or if the variability may be attributed to unconscious factors such as the documented variability in ash composition (e.g., [77,83,84,85,87]).

Further work is planned on Canterbury windows that will further our understanding of the glass supply during this period.

4.2. Identifying Episodes of Modification to the Panels

Turning to the frames above Methuselah and around Ezekias, which are areas of known intervention in the panels, the absence of kelp ash glass in the analyzed glass pieces and the dominance of medieval glass is striking, as it suggests that the modifications undertaken in the 1790s upon the removal of the panels to the GSW relied heavily upon the re-use of medieval glass pieces taken from other windows, which are no longer extant. It is possible that some of the more modern soda glass pieces now present in the panels were replacements for kelp ash glass pieces, which is not unlikely if the late 18th-century pieces were later considered visually incompatible with the appearance of the medieval panel. Still, the majority of the infill glasses are medieval glass pieces, most of which are broadly consistent with the Type A and Type B glasses used in the original glazing with some minor discrepancies that we attribute to variability between production events (e.g., [89]). Therefore, it appears that the glasses used to adapt the Ancestor figures for insertion into the GSW originated in windows broadly contemporaneous to the glazing of the Ancestors themselves.

This raises the question of whether some of those infill pieces originated from the missing Ancestor figures. The absent figures were already missing by the 1770s, when William Gostling listed the surviving Ancestors; however, he also documented windows containing “repaired mixed glass” [27] (p. 10) that may have housed fragments from the windows damaged by iconoclasts, including the clerestory windows and other 12th- and 13th-century windows. These miscellany windows, no longer extant, may have been dismantled only decades after Gostling’s account in order to adapt the extant figures for the great Perpendicular windows. If this was the case (that the miscellany windows contained fragments from the missing Ancestors or contemporary glass and were later used in the 1790s to adapt the figures for rectangular openings and other repairs), the glass used to repair and resize the Ancestors would have similar composition to the original glass (Type A and Type B), as we see in the results of this paper. This situation is well illustrated in Figure 10; the two yellow pieces marked in this detail of the Ezekias figure are compositionally identical to the other yellow glass pieces in the panel and yet they are plainly identified as infills by their painted detail.

Figure 10.

Detail from the Ezekias figure, showing the presence of two yellow glass pieces that are visually distinct in their painted detail yet are identical in trace element concentrations to the other yellow pieces found in this panel.

Another period of adaptation or re-use of old glass appears to have taken place in the early 13th century. The use of both Type A and Type B glass in the Nathan panels, and the distribution of these types (Figure 7), supports the suggestion that an earlier (Phase 0) figure was adapted for the clerestory windows by the glass-painters working in c. 1213–1220, the latter part of Phase 2. Excluding the head, which was replaced in the late 19th/early 20th century, the figure of Nathan is entirely composed of Type A glass, indicating that this portion of the panel was not glazed contemporarily to the other Phase 2 panels, but rather was glazed prior to the change in glass source. Although the compositional data themselves do not provide a more specific date for the glazing of this figure, they are fully consistent with the hypothesis put forth by Caviness [18] that the Nathan figure was glazed significantly before its installation in the clerestory in the early thirteenth century (Phase 2). They are consistent with the art-historical interpretation that the Nathan figure was glazed during Phase 0, salvaged after the fire of 1174 and reserved for re-use in the new building. Other portions of the Nathan panels are also glazed with Type A glass, including the white stars on a blue ground inside the canted square containing Nathan as well as significant portions of the frame, suggesting that these parts are also early and that the decorative motifs were replicated or extended by the glaziers working in Phase 2 in order to fill the clerestory window cavity. The hat, previously identified by Caviness [18] as Gothic in style and therefore consistent with a Phase 2 date, is composed of Type B glass. The rosettes above and below the figure, similar to those in the Ezekias panels, also date to the early 13th-century glazing. The close correspondence between the glass types and the identification by Caviness of earlier or later portions of the panel (down to Nathan’s hat) lends further support to the interpretation of a chronological change from Type A to Type B.

The frame surrounding the Ezekias figure (Phase 2) contained an unexpected result. The distribution of glass types suggests that the recycling of old glass in the early 13th century was not confined to Nathan and the three other potential Phase 0 figures. The frame outside the quatrefoil depicting Ezekias also appears to have been taken from an earlier window, with the rosette added during Phase 2. The outline of an upside-down arched window can be detected at the base of the panels (Figure 11), distinguished by glass types but also by the lead lines; this may be the shape of the clerestory window apex, which was then fleshed out into a rectangle during the 1790s modifications using Type B fragments and, at some point, upended. While the relatively narrow range of compositions present in the Type A glass make it difficult to confidently distinguish groups, the Type A green glass found in the Ezekias and Nathan panels are consistent with each other and mostly distinct from the Methuselah green glass, suggesting a common chronology between the two is more likely.

Table 2 and Figure 12 summarize the above interpretation of the glazing activities at Canterbury Cathedral as relates to the Ancestor panels analyzed and published here.

Table 2.

Interpretation of glazing activity according to the data of the current work, corresponding to Figure 12.

4.3. Re-Using Windows

A common method of “recycling” medieval stained glass involved dismantling windows and using their pieces to patch other windows that required intervention. In the post-medieval period, the use of medieval fragments was sometimes preferred to the use of freshly made glass for repairing medieval windows, as there was difficulty achieving the color and appearance of medieval glass using contemporary glass-making technology [90,91]. While the use of medieval glass from other windows could result in visually confusing panels, medieval glass preserved the “ancient tone and quality” [92] (p. 183) of the window under conservation [91,92,93,94]. Similar practicalities probably motivated the glaziers of the 1790s to use medieval fragments to adapt the Ancestor figures for their new positions.

The impetus for the removal of the Canterbury Ancestors from the clerestory for installation in the large Perpendicular-style windows in the southwest transept and west end must have come from the Gothic Revival, a movement in the late 18th and 19th centuries to revive Gothic forms in architecture. Perversely, works carried out within this movement were too often destructive in practice, with architects seeking to “improve” upon the medieval fabric of existing cathedrals with their own interpretations of Gothic architecture and in many instances, medieval stained glass windows were discarded and replaced [95,96]. While the removal and adaptation of the medieval panels might be seen as violating the responsibilities of cultural heritage preservation by today’s standards [94,97,98,99,100], it is fortunate that the decision-makers in Canterbury during the late 18th century appear to have been more conservative than some Gothic Revivalists, seeking to showcase the Ancestors more prominently rather than aiming to discard and replace them entirely.

The early 13th-century re-use of glass presents a more complex situation. The material and political circumstances were not advantageous: the construction of the cathedral had been completed and the architect had left, thus removing both figurative and literal structure (i.e., the scaffolding) from the glazing campaign; moreover, the glazing works were interrupted by political and religious upheavals in the city, such as a siege and subsequent dispute between the archbishop and monks from 1188–1201, and the exile of the Canterbury monks from 1207–1213, during which times glazing activity would have ceased [29,30]. These circumstances could have led to the re-use of old windows as a time- and resource-saving tactic, as well as allowing lesser-skilled glass-painters to help complete the glazing work in circumstances that had led to a shortage of talent.

Yet, in order to use the old windows in the early 13th century, the panels must have been reserved and stored for at least half a century, an act which indicates a “judgment of worth” [101] (p. 296) and which probably indicates a prior intention to incorporate the glass into the new cathedral’s windows. It is possible the Romanesque windows were stored without a specific aim in mind, and then integrated into the Ancestors series during the early thirteenth century in a final push to finish the glazing; this is one explanation for why they were not used in the earlier part of the series. However, the incorporation of Romanesque glazing into Gothic architectural contexts, or belles verrières (a term used as early as the fifteenth century for windows that are saved from earlier buildings and incorporated into new architectural contexts [101]), have been identified elsewhere, including Chartres, Châlons, and Vendôme [102,103,104]. While the subject matter of these windows was preserved when moved from their Romanesque to their new Gothic situations, they were imbued with further meaning and significance as reminders of, and tangible links to, the history and longevity of the site [101]. The importance attached to the representation of the building’s “lineage” [101] (p. 297) is evidenced by another window at Angers that, once thought to be a belle verrière, is now understood to be Gothic glazing mimicking Romanesque style, as if to claim an older origin [101,105,106]. The language used to describe the practice of re-using old windows is varied; Shepard [101] argued that this practice was less like recycling, which might be more appropriately used to describe the creation of fragmented “mosaic” windows (or the use of medieval fragments to patch or alter windows, as in the 1790s at Canterbury), and more akin to the use of spolia [107], except that the old and new contexts are not so wholly different (as, for example, a Roman object being incorporated into a Christian context). These Romanesque relics did not lose their former meaning when incorporated into Gothic contexts, but instead took on further significance and function in their role as vehicles of memory. Even when the incorporation of the earlier glazing into the new context is more invasive, as is evidenced at Rouen, where a large early 13th-century window was cut down into smaller segments to fit smaller late 13th-century openings [108], this meaning is still present and compelling. Similarly at Canterbury, the re-use of such large portions of the old windows, as observed in the Ancestors series (including both the figurative depiction of Nathan as well as the ornamental frame surrounding Ezekias and large portions of the frame surrounding Nathan), retains more of the original window’s artistic and iconographic identity than fragmented “recycling” of individual pieces, suggesting preservation rather than utility was a significant factor driving the decision; the careful copying of the Romanesque design in the frame around Nathan further supports this interpretation.

Shepard’s arguments regarding the purpose and meaning of belles verrières [101] were made without the benefit of surviving accounts recording the reasons behind their use, but for the Canterbury glass, there is a pertinent document by Gervase, a monk of Canterbury whose first-hand account of the fire and the rebuilding of the cathedral survives. He wrote that the architects directing the construction of the cathedral were instructed to preserve the previous building as much as was possible [109,110,111]. Indeed, Draper [110] argued that Canterbury’s regard for tradition was so great that actual repair and restoration of the “glorious choir” [111] (p. 32, 33) was implied by Gervase’s account, and this appears to have been the original aim of the construction. Heslop [112] argued that the lower windows of the choir, known as the typological windows, are close recreations of the pre-fire glazing scheme. The emphasis on preservation, which Boulting [109] referred to as conservatism due to “emotional ties” (p. 10) rather than historicism, may have also led to the rescue of some panels, when possible, and their storage for future use.

What is unknown, however, is whether the subject matter of the Nathan figure, like the belles verrières of Vendôme and Chartres, was preserved from its original context in the “glorious choir” that was built by Prior Conrad, or whether the figure was a portrayal of someone else (4 in Appendix A). Caviness [18] wondered about the origins of the banner bearing Nathan’s name; if these pieces also survived the 1174 fire, then it is likely an ancestral series adorned Conrad’s choir, as well, since Nathan is otherwise an uncommon subject in stained glass of the period. Two pieces of the banner were analyzed in the present study, one of compositional Type A glass and the other Type B. Both are parts of different letters “A”, and are painted in different styles. While not fully conclusive, it seems likely that part of a name survived (Type A), and was supplemented in the early 13th century (Type B). The revival of the ancestral subject matter would explain why this figure was not used at the beginning (Phase 1) of the glazing campaign, but instead was saved for decades, as its prior identity would have dictated its placement in the series.

Gervase described the Easter services in 1180 (by which point the transepts and the presbytery had been completed [29]), for which a temporary wooden partition was erected across the east end that contained three glazed windows. Caviness [113] suggested that he is likely to have mentioned this detail as it would have been a “rather unusual luxury” (p. 30) even if the windows could be used again in the finished cathedral. It is possible some of the pre-fire glass was temporarily housed in this partition, and if so, although portraits of ancestors of Christ would have made unusual subject matter for the focal point behind the altar, they might have been prized as relics of the earlier building and symbols of the ideological framework for the ongoing construction described by Gervase.

5. Conclusions

While significant research into the chemistry of stained glass windows has been carried out in the last decade, these studies have been concerned with technical or conservation issues and have rarely directly addressed the questions posed by art historians. Investigations have been constrained by the architectural situation of stained glass, the resulting difficulties in analysis and the absence of an over-arching understanding of glass compositions and their variation. Here, we have attempted to address a significant art-historical issue, focusing on one of the most important series of stained glass in Britain, if not Europe. Non-invasive analysis of the genealogical figures from the former clerestory windows of Canterbury Cathedral by handheld pXRF, using a simple instrumental modification and focusing upon a small number of carefully selected elements has identified a change in the composition of window glass used in Canterbury in the late 12th or early 13th century. Furthermore, this change in composition corresponds to a contemporary change in the organization of production for glasses of different color. This has allowed us to address a key hypothesis in the early history of the stained glass of Canterbury Cathedral put forward by Caviness [18], who in 1987 suggested that amongst the extant Ancestor Windows are survivors of the 1174 fire that destroyed the previous choir. The results of the present study lend support to her interpretation and to the view that these are some of the earliest known painted windows extant in England, and the world. Furthermore, the current research indicates that the glass from the southwest transept and west end, installed there during the 1790s, is likely to contain more pre-1174 glass than has previously been considered.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.W.A., I.C.F. and L.S.; Methodology, L.W.A.; Validation, L.W.A.; Formal Analysis, L.W.A.; Investigation, L.W.A.; Resources, I.C.F. and L.S.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, L.W.A. and I.C.F.; Writing—Review and Editing, L.W.A., I.C.F. and L.S.; Visualization, L.W.A., I.C.F. and L.S.; Supervision, I.C.F.; Funding Acquisition, L.W.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the UCL Graduate/Overseas Research Scholarships to LWA and a grant from the Canterbury Historical and Archaeological Society to LWA.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the article in graphical form. We have elected not to report the data in numerical or tabular form due to inherent problems in presenting or using data collected from surface analyses as fully quantified data representative of the bulk composition. However, as long as this is understood, the data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Dean and Chapter of Canterbury and to the Cathedral Studios for providing access to the materials. Special thanks are owed to Tim Ayers and Rachel Koopmans, who made invaluable comments on this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

- The term ‘grisaille’ also refers to monochrome painting in various media generally, and within the study of stained glass windows, is also used to refer to windows typical of the late 14th/early 15th century, which was dominated by grisaille-painted white glass, or to refer to the white glass itself. In this paper, like in many other scientific studies of stained glass, grisaille will be used to refer to the pigment only.

- Different atelier groups in the glazing of Canterbury Cathedral (including the clerestory windows) have also been identified and characterized [29,30,112]. In the clerestory windows [29], three stylistic groups have been identified: (1) the windows of the choir, completed under the first architect, William of Sens, who left the project in 1179 after falling from the vaulting; (2) the windows of the transepts and presbytery, hurriedly completed by 1180 under the second architect, William the Englishman; (3) the windows of the Trinity Chapel, completed out of pace with the construction works and largely after the construction had finished and William the Englishman had left. For the purposes of this paper, we are considering two phases of production: the time during which glazing kept pace with the building’s construction, and afterwards when it did not.

- Of those seven, only one is still in its original position, and another is still in its original window but moved to a different position within it. The other five have been moved to other windows, but they are still in the clerestory.

- In a lecture (“Before the Ancestors: the clerestory windows of the early 12th century”, 22 May 2015, as part of a series accompanying the exhibition of The Ancestors at Canterbury Cathedral in 2015), Sandy Heslop supported not only the presence of pre-fire glass amongst the Ancestors series, but also argued for the idea that the pre-fire clerestory contained an Ancestors of Christ scheme, and that the post-1174 glazing reflected the earlier program.

References

- Cramp, R. Decorated window-glass and millefiori from Monkwearmouth. Antiq. J. 1970, 50, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schibille, N.; Freestone, I.C. Composition, production and procurement of glass at San Vincenzo Al Volturno: An early Medieval monastic complex in Southern Italy. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, S.; Kessler, C.M.; Stern, W.B.; Gerber, Y. The composition and manufacture of early medieval coloured window glass from Sion (Valais, Switzerland)—A Roman glass-making tradition or innovative craftsmanship? Archaeometry 2005, 47, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herold, M.; David, V. Vitrail, Ve-XXI Siecle; Éditions du Patrimoine: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Acqua, F. Early History of Stained Glass. In Investigations in Medieval Stained Glass: Materials, Methods, and Expressions; Kurmann-Schwarz, B., Pastan, E.C., Eds.; Brill: Boston, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 23–35. [Google Scholar]

- Aunay, C.; Berthon, A.A.; Gratuze, B.; Guérit, M.; Motteau, J.; Pactat, I. Le verre creux du VIII e au X e siècle dans la vallée de la Loire moyenne et de la Vienne. Essai typo-chronologique et archéométrique. In Le Verre du VIII e au XVI e Siècle en Europe Occidentale: 8 e Colloque International de l’AFAV; Pactat, I., Munier, C., Eds.; Presses universitaires de Franche-Comté: Besançon, France, 2020; Volume 40, pp. 293–314. [Google Scholar]

- Wedepohl, K.H.; Simon, K. The chemical composition of medieval wood ash glass from Central Europe. Geochemistry 2010, 70, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wersch, L.; Loisel, C.; Mathis, F.; Strivay, D.; Bully, S. Analyses of Early Medieval Stained Window Glass From the Monastery of Baume-Les-Messieurs (Jura, France). Archaeometry 2016, 58, 930–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, C.; Machado, A.; Palomar, T.; Vilarigues, M. Grisaille in Historical Written Sources. J. Glass Stud. 2019, 61, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcon-Berry, S.; Perrot, F.; Sapin, C. Vitrail, Verre et Archéologie Entre le Ve et le XIIe Siècle; Archéologie et histoire de l’art 31: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Granboulan, A. Longing for the Heavens: Romanesque Stained Glass in the Plantagenet Domain. In Investigations in Medieval Stained Glass: Materials, Methods, and Expressions; Kurmann-Schwarz, B., Pastan, E.C., Eds.; Brill: Boston, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becksmann, R. Die Augsburger Propheten und die Anfänge des monumentalen Stils in der Glasmalerei. Z. Dtsch Ver. Kunstwiss 2005, 59, 84–110. [Google Scholar]

- Bony, J. French Gothic Architecture of the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum, N. German Gothic Church Architecture; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Von Simpson, O. The Gothic Cathedral; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, C. The Gothic Cathedral: The Architecture of the Great Church, 1130–1530; Thames and Hudson: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, R. Stained Glass in England during the Middle Ages; Routledge: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Caviness, M.H. Romanesque “belles verrières” in Canterbury. In Romanesque and Gothic: Essays for George Zarnecki; Stratford, N., Ed.; Boydell Press: Woodbridge, NH, USA, 1987; pp. 35–38. [Google Scholar]

- Dungworth, D. Historic windows: Investigation of composition groups with nondestructive pXRF. Glass Technol. Eur. J. Glass Sci. Technol. Part. A 2012, 53, 192–197. [Google Scholar]

- Dungworth, D. Glassworking in England from the 14th to the 20th Century; Historic England: Swindon, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, H.M.; Murdoch, K.R.; Buckman, J.; Forster, A.M.; Kennedy, C.J. Compositional Analysis by p-XRF and SEM-EDX of Medieval Window Glass from Elgin Cathedral, Northern Scotland. Archaeometry 2018, 60, 1018–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Snickt, G.; Legrand, S.; Caen, J.; Vanmeert, F.; Alfeld, M.; Janssens, K. Chemical imaging of stained-glass windows by means of macro X-ray fluorescence (MA-XRF) scanning. Microchem. J. 2016, 124, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, R.B.; Shortland, A.J.; Degryse, P.; Power, M.; Domoney, K.; Boyen, S.; Braekmans, D. In situ analysis of ancient glass: 17th century painted glass from Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford and Roman glass vessels. Glass Technol. Eur. J. Glass Sci. Technol. Part A 2012, 53, 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Cagno, S.; Van der Snickt, G.; Legrand, S.; Caen, J.; Patin, M.; Meulebroeck, W.; Dirkx, Y.; Hillen, M.; Steenackers, G.; Rousaki, A.; et al. Comparison of four mobile, non-invasive diagnostic techniques for differentiating glass types in historical leaded windows: MA-XRF, UV–Vis–NIR, Raman spectroscopy and IRT. X-Ray Spectrom. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adlington, L.W.; Freestone, I.C. Using handheld pXRF to study medieval stained glass: A methodology using trace elements. MRS Adv. 2017, 2, 1785–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adlington, L.W.; Freestone, I.C.; Seliger, L.; Martinón-Torres, M.; Brock, F.; Shortland, A.J. In situ methodology for compositional grouping of medieval stained glass windows: Introducing the “WindoLyzer” for Handheld X-ray Fluorescence Spectrometry. In Archaeological Chemistry: A Multidisciplinary Analysis of the Past; Orna, M.V., Rasmussen, S.C., Eds.; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2020; pp. 176–200. [Google Scholar]

- Caviness, M.H. The Windows of Christ Church Cathedral Canterbury; CVMA (GB) II: London, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, J.; Caviness, M.H. The Ancestors of Christ Windows at Canterbury Cathedral; J. Paul Getty Museum: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Caviness, M.H. Canterbury Cathedral Clerestory: The Glazing Programme in Relation to the Campaigns of Construction. In Medieval Art and Architecture at Canterbury before 1220. British Archaeological Association Conference Transactions for the Year 1979; Maney Publishing: Leeds, UK, 1982; Volume 5, pp. 46–55. [Google Scholar]

- Koopmans, R. Pilgrimage scenes in newly identified medieval glass at Canterbury Cathedral. Burlingt. Mag. 2019, 161, 708–715. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, C.J.; Murdoch, K.R.; Kirk, S. Characterization of archaeological and in situ Scottish window glass. Archaeometry 2013, 55, 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, S.; Newton, R.G. Conservation and Restoration of Glass; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, G.A.; Heavens, O.S.; Newton, R.G.; Pollard, A.M. A study of the weathering behaviour of medieval glass from York Minster. J. Glass Stud. 1979, 21, 54–75. [Google Scholar]

- Gentaz, L.; Lombardo, T.; Loisel, C.; Chabas, A.; Vallotto, M. Early stage of weathering of medieval-like potash—lime model glass: Evaluation of key factors. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 2011, 18, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biron, I.; Alloteau, F.; Lehuédé, P.; Majérus, O.; Caurant, D. Glass Atmospheric Alteration: Cultural Heritage, Industrial and Nuclear Glasses; Hermann: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Majérus, O.; Lehuédé, P.; Biron, I.; Alloteau, F.; Narayanasamy, S.; Caurant, D. Glass alteration in atmospheric conditions: Crossing perspectives from cultural heritage, glass industry, and nuclear waste management. NPJ Mater. Degrad. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterpenich, J.; Libourel, G. Using stained glass windows to understand the durability of toxic waste matrices. Chem. Geol. 2001, 174, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sessegolo, L.; Verney-Carron, A.; Ausset, P.; Nowak, S.; Triquet, S.; Saheb, M.; Chabas, A. Alteration rate of medieval potash-lime silicate glass as a function of pH and temperature: A low pH-dependent dissolution. Chem. Geol. 2020, 550, 119704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomar, T.; de la Fuente, D.; Morcillo, M.; Alvarez de Buergo, M.; Vilarigues, M. Early stages of glass alteration in the coastal atmosphere. Build. Environ. 2019, 147, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melcher, M.; Schreiner, M.R. Evaluation procedure for leaching studies on naturally weathered potash-lime-silica glasses with medieval composition by scanning electron microscopy. J. Non Cryst. Solids. 2005, 351, 1210–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melcher, M.; Schreiner, M.R. Leaching studies on naturally weathered potash-lime-silica glasses. J. Non Cryst. Solids. 2006, 352, 368–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, T.; Loisel, C.; Gentaz, L.; Chabas, A.; Verita, M.; Pallot-Frossard, I. Long term assessment of atmospheric decay of stained glass windows. Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2010, 45, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiner, M.R.; Woisetschläger, G.; Schmitz, I.; Wadsak, M. Characterisation of surface layers formed under natural environmental conditions on medieval stained glass and ancient copper alloys using SEM, SIMS and atomic force microscopy. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 1999, 14, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, N.; Oujja, M.; Rebollar, E.; Römich, H.; Castillejo, M. Analysis of corroded glasses by laser induced breakdown spectroscopy. Spectrochim Acta—Part B At. Spectrosc. 2005, 60, 1155–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilarigues, M.; Redol, P.; Machado, A.; Rodrigues, P.A.; Alves, L.C.; da Silva, R.C. Corrosion of 15th and early 16th century stained glass from the monastery of Batalha studied with external ion beam. Mater. Charact. 2011, 62, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, R.G. The Deterioration and Conservation of Painted Glass: A Critical Bibliography; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Sterpenich, J.; Libourel, G. Les vitraux médiévaux: Caractérisation physico-chimique de l’altération. Techne 1997, 6, 70–78. [Google Scholar]

- Woisetschläger, G.; Dutz, M.; Paul, S.; Schreiner, M.R. Weathering Phenomena on Naturally Weathered Potash-Lime-Silica-Glass with Medieval Composition Studied by Secondary Electron Microscopy and Energy Dispersive Microanalysis. Mikrochim Acta 2000, 135, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, T.; Gentaz, L.; Verney-Carron, A.; Chabas, A.; Loisel, C.; Neff, D.; Leroy, E. Characterisation of complex alteration layers in medieval glasses. Corros. Sci. 2013, 72, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulinas, M.; Garcia-Vallès, M.; Gimeno, D.; Fernandex-Turiel, J.L.; Ruggieri, F.; Pugès, M. Weathering patinas on the medieval (S. XIV) stained glass windows of the Pedralbes Monastery (Barcelona, Spain). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2009, 16, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, N. Corrosion of Stained Glass Windows: Applied Study of Spanish Monuments of Different Periods. In Modern Methods for Analysing Archaeological and Historical Glass; Janssens, K., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Piñar, G.; Garcia-Valles, M.; Gimeno-Torrente, D.; Fernandez-Turiel, J.L.; Ettenauer, J.; Sterflinger, K. Microscopic, chemical, and molecular-biological investigation of the decayed medieval stained window glasses of two Catalonian churches. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2013, 84, 388–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.; Gutierrez-Patricio, S.; Zélia Miller, A.; Saiz-Jimenez, C.; Wiley, R.; Nunes, D.; Vilarigues, M.; Macedo, M.F. Fungal biodeterioration of stained-glass windows. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2014, 90, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, N.; Villegas, M.A.; Navarro, J.M.F.; Ferna, J.M. Study of glasses with grisailles from historic stained glass windows of the cathedral of León (Spain). Appl. Surf. Sci. 2006, 252, 5936–5945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, A.; Wolf, S.; Alves, L.C.; Katona-serneels, I.; Serneels, V. Swiss Stained-Glass Panels: An Analytical Study. Microsc. Microanal. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradell, T.; Molina, G.; Murcia, S.; Ibáñez, R.; Liu, C.; Molera, J.; Shortland, A.J. Materials, Techniques, and Conservation of Historic Stained Glass “Grisailles”. Int. J. Appl. Glass Sci. 2016, 7, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.; Coutinho, M.; Machado, A.; Martinho, B.A. A transparent dialogue between iconography and chemical characterisation: A set of foreign stained glasses in Portugal [PREPRINT]. Herit. Sci. 2021, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.Y.; Suetsugu, T.; Kadono, K. Incorporation of silver into soda-lime silicate glass by a classical staining process. J. Non Cryst. Solids 2007, 353, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jembrih-Simbürger, D.; Neelmeijer, C.; Schalm, O.; Fredrickx, P.; Schreiner, M.R.; De Vis, K.; Mäder, M.; Schryvers, D.; Caen, J. The colour of silver stained glass-analytical investigations carried out with XRF, SEM/EDX, TEM, and IBA. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2002, 17, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, J.; Vilarigues, M.; Ruivo, A.; Corregidor, V.; Silva, R.C.; Alves, L.C. Characterisation of medieval yellow silver stained glass from Convento de Cristo in Tomar, Portugal. Nucl. Instruments Methods Phys. Res. B 2011, 269, 2383–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilarigues, M.; da Silva, R.C. Ion beam and infrared analysis of medieval stained glass. Appl. Phys. A 2004, 79, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.; Rousaki, A.; Lycke, S.; Saelens, D.; Tack, P.; Sánchez, A.; Tuñón, J.; Ceprián, B.; Amate, P.; Montejo, M.; et al. Comparison of the performance of two handheld XRF instruments in the study of Roman tesserae from Cástulo ( Linares, Spain). Eur. Phys. J. Plus. 2020, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adlington, L.W. The Corning Archaeological Reference Glasses: New Values for “Old” Compositions. Pap. Inst. Archaeol. 2017, 27, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, B.; Nowak, A.; Bulska, E.; Hametner, K.; Günther, D. Critical assessment of the elemental composition of Corning archeological reference glasses by LA-ICP-MS. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2012, 402, 1667–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brill, R.H. Chemical Analyses of Early Glasses; Corning Museum of Glass: Corning, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Adlington, L.W.; Gratuze, B.; Schibille, N. Comparison of pXRF and LA-ICP-MS analysis of lead-rich glass mosaic tesserae. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2020, 34, 102603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, R.G. Simulated medieval glasses. Corpus. Vitr. Newsl. 1977, 25, 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Jochum, K.P.; Weis, U.; Stoll, B.; Kuzmin, D.; Yang, Q.; Raczek, I.; Jacob, D.E.; Stracke, A.; Birbaum, K.; Frick, D.A.; et al. Determination of reference values for NIST SRM 610-617 glasses following ISO guidelines. Geostand. Geoanalytical. Res. 2011, 35, 397–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SGT Society of Glass Technology. Green Soda-Lime-Silica Container Glass SGT 11. 2000. Available online: https://cdn.ymaws.com/sgt.org/resource/resmgr/certificatesofanalysis/green_certificate__11.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2021).

- Capobianco, N.; Hunault, M.O.J.Y.; Balcon-Berry, S.; Galoisy, L. The Grande Rose of the Reims Cathedral: An eight-century perspective on the colour management of medieval stained glass. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunault, M.; Bauchau, F.; Loisel, C.; Hérold, M.; Galoisy, L.; Newville, M.; Calas, G. Spectroscopic Investigation of the Coloration and Fabrication Conditions of Medieval Blue Glasses. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2016, 99, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunicki-Goldfinger, J.J.; Freestone, I.C.; McDonald, I.; Hobot, J.A.; Gilderdale-Scott, H.; Ayers, T. Technology, production and chronology of red window glass in the medieval period—rediscovery of a lost technology. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2014, 41, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girbal, B.; Dungworth, D. Ightham Mote, Ightham, Kent: Portable XRF Analysis of the Window Glass. Archaeol Sci. Portsmouth: English Heritage. 2011. Available online: http://research.historicengland.org.uk/ (accessed on 13 April 2013).

- Wilk, D.; Kamińska, M.; Walczak, M.; Bulska, E. Archaeometric investigations of medieval stained glass panels from Grodziec in Poland. In Lasers in the Conservation of Artworks XI, Proceedings of LACONA XI; Targowski, Ed.; NCU Press: Torún, Poland, 2017; pp. 263–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adlington, L.W.; Freestone, I.C.; Kunicki-Goldfinger, J.J.; Ayers, T.; Gilderdale Scott, H.; Eavis, A. Regional patterns in medieval European glass composition as a provenancing tool. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2019, 110, 104991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brems, D.; Ganio, M.; Latruwe, K.; Balcaen, L.; Carremans, M.; Gimeno, D.; Silvestri, A.; Vanhaecke, F.; Muchez, P.; Degryse, P. Isotopes on the Beach, Part 1: Strontium Isotope Ratios As a Provenance Indicator for Lime Raw Materials Used in Roman Glass-Making. Archaeometry 2013, 55, 214–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, W.B.; Gerber, Y. Potassium—Calcium glass: New data and experiments. Archaeometry 2004, 46, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedepohl, K.H. Mittelalterliches Glas in Mitteleuropa: Zusammensetzung, Herstellung, Rohstoffe. Nachrichten der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Göttingen, 2, Mathematisch-Physikalische Klasse 1; Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht: Göttingen, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wedepohl, K.H. Glas in Antike und Mittelalter: Geschichte Eines Werkstoffs; Schweizerbart’sche Verlagsbucchandlung: Stuttgart, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cílová, Z.; Woitsch, J. Potash—A key raw material of glass batch for Bohemian glasses from 14th-17th centuries? J. Archaeol. Sci. 2012, 39, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobner, U.; Tyler, G. Conditions controlling relative uptake of potassium and rubidium by plants from soils. Plant. Soil. 1998, 201, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.M.; Smedley, J.W. Medieval and post-medieval glass technology: Melting characteristics of some glasses melted from vegetable ash and sand mixtures. Glass Technol. Eur. J. Glass Sci. Technol. Part. A 2004, 45, 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, C.M.; Booth, C.A.; Smedley, J.W. Glass by design? Raw materials, recipes and compositional data. Archaeometry 2005, 47, 781–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.M.; Smedley, J.W. Medieval and post-medieval glass technology: Seasonal changes in the composition of bracken ashes from different habitats through a growing season. Glass Technol. Eur. J. Glass Sci. Technol. Part. A 2008, 49, 240–245. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, W.E.S. Studies of Ancient Glass and Glass-making Processes. Part V. Raw Materials and Melting Processes. J. Soc. Glass Technol. 1956, 40, 277–300. [Google Scholar]

- Meiwes, K.J.; Beese, F. Ergebnisse der Untersuchung des Stoffhaushaltes eines Buchenwaldökosystems auf Kalkgestein. Ber. Forsch. Wald. 1988, B9, 1–142. [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson, D.C.W.; Hunter, J.R. Composition variability in vegetable ash. Sci Archaeol. 1981, 23, 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hunault, M.O.J.Y.; Loisel, C.; Bauchau, F.; Lemasson, Q.; Pacheco, C.; Moignard, B.; Boulanger, K.; Hérold, M.; Calas, G.; Pallot-Frossard, I. Non-destructive redox quantification reveals glassmaking of rare French Gothic stained glasses. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 6277–6284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freestone, I.C.; Price, J.; Cartwright, C.R. The Batch: Its Recognition and Significance. In Annales du 17e Congrès de l’Association Internationale pour l’Histoire du Verre, Anvers 4–8 Septembre 2006; Janssens, K., Degryse, P., Cosyns, P., Caen, L., Van’t dack, L., Eds.; AIHV: Corning, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 130–135. [Google Scholar]

- Goldring, T. Recovered or Perfected: The Discourse of Chemistry in the Nineteenth-Century Revival of Stained Glass in Britain and France. 19 Interdiscip Stud. Long Ninet Century 2020, 2020, 14–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winston, C. Memoirs Illustrative of the Art of Glass-Painting; John Murray: London, UK, 1865. [Google Scholar]

- Milner-White, E. The Restoration of the East Window of York Minster. Antiq. J. 1950, 30, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S. Medieval Stained Glass and the Victorian Restorer. 19 Interdiscip Stud. Long Ninet Century 2020, 2020, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S. The Great East. Window of York Minster: An. English Masterpiece; Third Millennium Publishing LTD: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett, J. A restoration tragedy: Cathedrals in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In The Future of the Past: Attitudes to Conservation 1174–1974; Fawcett, J., Ed.; Thames and Hudson: London, UK, 1976; pp. 74–115. [Google Scholar]

- Raguin, V.C. Revivals, Revivalists, and Architectural Stained Glass. J. Soc. Archit Hist. 1990, 49, 310–329. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/990521/ (accessed on 3 June 2021). [CrossRef]

- Pye, E. Caring for the Past: Issues in Conservation for Archaeology and Museums; James & James Ltd.: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Richmond, A.; Bracker, A. Conservation: Principles, Dilmennas, and Uncomfortable Truths; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Philippot, P. Historic preservation: Philosophy, criteria, guidelines. In Historical and Philosophical Issues in the Conservation of Cultural Heritage; Stanley-Price, N., Talley, M.K., Melucco, V.A., Eds.; Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CT, USA, 1996; pp. 268–274. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, R.; Atkinson, L. The Medieval Glazing of Westminster Abbey: New Discoveries [Recorded Lecture]. In British Archaeological Association Annual Lecture Series. 2017. Available online: https://thebaa.org/event/the-medieval-glazing-of-westminster-abbey-new-discoveries/ (accessed on 14 February 2018).

- Shepard, M.B. Memory and Belles Verrières. In Romanesque: Art and Thought in the Twelfth Century; Hourihane, C., Ed.; Princeton Index of Christian Art in association with Penn State University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 290–302. [Google Scholar]

- Grodecki, L. Des origines à la fin du XII e siècle. In Le Vitrail Français; Aubert, M., Chastel, A., Grodecki, L., Gruber, J.-J., Lafond, J., Mathey, F., Eds.; Éditions Mondes: Paris, France, 1958; pp. 95–114. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchon, C.; Brisac, C.; Lautier, C.; Zaluska, Y. La “Belle-Verrière” de Chartres. Rev. l’Art. 1979, 46, 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Lillich, M.P. Remembrance of Things past: Stained Glass Spolia at Chalons Cathedral. Z Kunstgesch. 1996, 59, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulanger, K. Les vitraux du chœur de la cathédrale d’Angers: Commanditaires et iconographie. In Anjou: Medieval Art, Architecture, and Archaeology. British Archaeological Association Conference Transactions XXVI, 2000; Maney Publishing: Leeds, UK, 2003; pp. 196–209. [Google Scholar]

- Boulanger, K. Les Vitraux de la Cathédrale d’Angers; Corpus Vitrearum France III: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kinney, D. The Concept of Spolia. In A Companion to Medieval Art: Romanesque and Gothic in Northern Europe; Conrad, R., Ed.; Wiley-Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2010; pp. 233–252. [Google Scholar]

- Cothren, M.W. The Seven Sleepers and the Seven Kneelers: Prolegomena to a Study of the “Belles Verrières” of the Cathedral of Rouen. Gesta 1986, 25, 203–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulting, N. The law’s delays: Conservationist legislation in the British Isles. In The Future of the Past: Attitudes to Conservation 1174–1974; Fawcett, J., Ed.; Thames and Hudson: London, UK, 1976; pp. 9–33. [Google Scholar]

- Draper, P. Interpretations of the Rebuilding of Canterbury Cathedral, 1174–1186: Archaeological and Historical Evidence. J. Soc. Archit Hist. 1997, 56, 184–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, R. The Architectural History of Canterbury Cathedral; Longman: London, UK, 1845. [Google Scholar]

- Heslop, T.A.H. St Anselm and the Visual Arts at Canterbury Cathedral, 1093–1109. In Medieval Art, Architecture & Archaeology at Canterbury. The British Archaeological Association Conference Transactions XXXV 2009; Maney Publishing: Leeds, UK, 2014; pp. 59–81. [Google Scholar]

- Caviness, M.H. The Early Stained Glass of Canterbury Cathedral c. 1175–1220; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).