Abstract

Collective memory is vital for people as it gives them the sense of belonging to a community. In particular, refugee population groups feel the need to maintain contact with their routes through collective memory, due to the abolishment of the physical connection to their homeland. However, people’s memories fade over time and stories are lost. In such a context a crucial question arises: Is it feasible to design and create a crowdsourcing collective memory management system for the benefit of such social groups preserving memory for next generations? In this work, we present a system that is able to collect and manage refugee stories disseminating them to the public. In order to stress the strength of the proposed system, we have created an evaluation methodology that assesses such a system in terms of system services and system stakeholders’ real impact. We chose to deal with the collective memory of refugee groups coming from Asia Minor to Greece at the end of the first quarter of the twentieth century. Evaluation results reveal that such a system positively affects personal and social impact factors. Furthermore, a preliminary results analysis suggests specific interactions among the examined personal and social impact factors. We believe that the proposed system facilitates the needs of collective memory management and the assessment scheme could be adapted in the creation and evaluation of collective memory management systems.

1. Introduction

Intangible cultural heritage (ICH) is “transmitted from generation to generation, is constantly recreated by communities and groups in response to their environment, their interaction with nature and their history, and provides them with a sense of identity and continuity” [1]. Today UNESCO’s attention is given to displaced persons [2]. These people are often leaving their homelands, and thus, their bonds with their cultural heritage roots are damaged. It is necessary to assist those people to preserve their cultural heritage (CH). The carriers of these bonds are memories.

Memories remain in people’s minds but fade over time and as such, their timely recording is necessary. Current information technology can gather data from people that have suffered violent events and help them heal any trauma caused. The authors of [3] reported that memory is of great value when it is shared, as it causes the activation of other people memories. Also, memories become stronger when they are connected to existing objects. People suffering displacement usually carry with them objects that are valuable, objects that help them remember. In such a context, several questions arise. How can memories be associated with persons’ memorabilia from their homelands and their past lives? Can spontaneous, person memories form collective memory repositories?

Heritage has the great potential to become a tool for supporting political reconciliation and stability [4]. There are few nations in the world that have not been born out of violence, a fact that is reflected in each country’s list of monuments [5]. Giblin, studying symbolic healing and cultural renewal, states that heritage is better understood as a common element of post-conflict renewal, which becomes intensified as the past is aggressively negotiated to provide healing related to conflict trauma [6]. Basu states that it is better to negotiate a heritage of conflict rather than building a post-war society on a flimsy myth of piece [5]. Cultural heritage systems may also serve the needs of cultural groups in large urban centers. Systems that care about the smart management of information in the context of a city have already been implemented [7,8]. However, CH is a predominantly unexploited asset presenting multiple integration opportunities within city contexts [9,10]. For example, 9/11 was a devastating event experienced by the inhabitants of a city which created a collective memory. Also, an urban environment could alienate its inhabitants due to the long distances created between people sharing common interests as well as collective memory. We are aware that regimes have the power to shape the collective memory of their nations [11]. In some countries, previously suppressed, marginalized, and “unofficial” memories can now be collected and disseminated [12]. A challenge for systems that deal with traumatic collective memory is to allow people to upload their content without being censored by the applied authoring mechanism.

People already use social networks to create collections of items related to the past [13,14] or to participate in the crisis management of their society [15]. Gaitan [16] states that social media is a great instrument to preserve and promote CH. The success of social media networks in the preservation and promotion of CH relies on the vast number of users they contain. Efforts to collect memory exploit this advantage [17]. People tend to form communities in order to discuss issues of common interest to them. But what about the management of this information? The solution could be in the form custom management CH data. Several digital systems cater for memory collection [8,18,19,20,21]. Some specific challenges arise: Is it feasible to enhance people’s memories management through a digital system supporting mobile services? Is a trustworthy system a prerequisite for people in order to share their intangible and tangible memories?

Crowdsourcing (CS) [22,23,24] promises to help data gathering for several real-life paradigms. The use of this technology can apply also in CH [25] and specifically in memory collection systems [8,18,26,27]. CS can solve the problem of recruiting big teams for digitizing intangible and tangible memories by involving citizens in this task. A citizen will contribute her/his memory associated with specific memorabilia which are in her/his property. A system that supports CS through specific collection services can benefit the transformation of a city to a smart one [28]. Two interested questions concerning smart services and collective memory management follow: Can we address diverse users’ needs and expectations using a system preserving collective memory? How can we exploit the stored memories in such a dynamic archive for educational purposes?

Systems are usually designed to be used in the real world. The success of a system depends on the success of its evaluation. A set of criteria for evaluation of information systems is described in [29]. The evaluation methodologies usually care about criteria related to the application interface or the contained services [30,31,32]. Models are often used to evaluate a systems’ acceptance [33,34,35]. A well-known evaluation methodology in CH is CH-MILE [36] which cares about usability evaluation and problem detection, but it is a time-consuming process.

This work is focused on the design, implementation and evaluation of a crowdsourcing collective memory management system dedicated to groups of people violently evicted (or not) from their homeland (or not). A preliminary version of this work has been presented in [37]. In the process of the system development, we designed and applied a “sustainable” evaluation methodology. We are interested in assessing the design goals and the required services which should be offered by such a system, along with the evaluation of personal and social impact to content contributors (volunteers), groups with an interest in cultural heritage or general population. In order to apply the proposed methodology, we designed and implemented a system that collects, manages and disseminates people’s memories (http://crowdpower.e-ch.eu). The system interacts with the users through a portal and a mobile app. The mobile app is the tool that implements all CS services helping volunteers collect and upload their stories and digitized memorabilia. The portal contains services for the management and dissemination of imported stories. Services such as management, annotation, story collection creation and view are assigned to different types of users in a trustworthy manner using the Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) model.

2. Related Work

For several years, CS has been used for providing services and information to people while processing data provided by them. Industries and researchers have already developed software based on the idea of CS with their popular field to be traffic and navigation [38]. Moovit is an app that gets feedback from its users and provides them information regarding the best transit route to follow, or a public transport arrival time taking into account the traffic data of the area [39]. iSPEX is a system that gathers information from a smartphone app with the help of special equipment attached to it and the processed data create a map showing air pollution in Europe [40]. Such applications have thrived because they exploit the widespread availability of mobile phones and the use of wireless internet [38]. However, issues such as the control of the content quality, task assignment and finding ways to motivate volunteers, remain [24]. When looking at CS in CH the challenges include focusing on semantic web techniques, gathering loyal users and quality assurance [25]. In this work, we first attempt to model collective memory data in a coherent context taking into account user needs in terms of raising user awareness and facilitating users operating as memory carriers. Regarding quality assurance, a question that can be asked is about the quality such a content can have (in terms of image resolution or content coherence). This obstacle has now been overcome, thanks to technological progress. The technical quality of digital material (photos, videos, audio) that volunteers feed into databases is usually very good. Cameras, camcorders, and smart mobile devices with many capabilities are now easier to be obtained by non-experts [23]. However, the problem of soundness concerning content uploaded by users remains. Some solutions to this problem have been proposed in [26,27], based on content authoring by specialists. In order to ensure the quality of the collected content, the developed system applies an authoring mechanism, asking expert users to comment on the validity of the provided content and permitting any registered user, expert or not, to rate the corresponding post.

In CS projects the crowd participation is essential. However, the crowd needs to be motivated. In GLAM projects (galleries, libraries, archives, museums) intrinsic motivations (egoism, community and enjoyment based) are more valuable than the extrinsic (social) ones [41]. But participation is not enough. The public needs to be deeply engaged and crowdsourcing is suggested to be ideal towards this objective [42]. In the field of Cultural Heritage (CH) the type of crowdsourcing projects could be contributory, collaborative, co-curated, co-created depending on the aim: transcription and correction work, understanding, collection, classification, co-editing, money collection, microhistory [25]. The design of a CS system to be successful should be executed with care, because of engaging the public in the whole activity. A simple design may not quite be attractive to the public, but a more complex and step-by-step design with more requirements is likely to succeed and encourage an audience [43]. Gathering loyal users is essential for a crowd-sourcing system. The proposed system has an advantage compared to other crowd-sourcing systems. The potential user group is people that have an interest in a specific collective memory, which mainly is traumatic. The proposed system supports specific participatory services that permit users not only to offer their content, but, also, to comment on it, exchange ideas with other people and transfer their memories to younger generations creating a dynamic social ecosystem. Also, the presented system strengthens the cohesion of the society giving to other people who are not related to the specific collective memory the opportunity to know their neighbors. The user loyalty in the system further increases due to a specific mobile app service that permits a mere user to become a researcher itself and collect relative material.

One of the most known CS systems in CH is the project called “Europeana 1914-1918”. It is a project created to gather the untold stories and official histories of World War I. People can upload their data and a repository available to the public disseminates all that information through a portal [26]. The project “1001 stories about Denmark” focuses on stories from Denmark and tries to raise people’s interest about the history of the country [18]. Using a desktop application or a mobile app, registered users can upload their stories along with connected digitized material. “HistoryPin” is mainly focused on groups of pins about particular places and themes gathered by their members [8]. These groups of pins are named collections. Each pin is a mark on a map, which can contain text, images, audio and video items. Another great effort was made in Singapore [17], where there was a need to record both institutional and personal memories related to the city. Every available means (portal, mobile app, social networks, etc.) was used and managed to gather millions of memory artifacts. MOSAICA [30] is a Web 2.0-based toolbox, dedicated to the preservation and presentation of cultural heritage. MOSAICA permits users to create personal stories, share them with the community and express their national, ethnic and religious identity values and legacy. Finally, a distinct case is the one that refers to the restoration of an old Greek bridge called the bridge of “Plaka” [44]. After the destruction of the bridge, caused by extreme weather conditions, there was a need to start its restoration. Since it was a very popular tourist destination, the public was asked to contribute images in order to create a fully detailed 3D image of the bridge. About 130 volunteers contributed digital material, uploading more than 470 photos. A more general type of system permitting content contribution is participatory platforms. MOSAICA [30] and Culture-Gate [27] are examples of participatory platforms for CH.

The evaluation process of a system is critical. Qualitative, quantitative [45] or mixed methods [46] are used for this objective. In a number of studied evaluation procedures, a variety of tools and methods was observed [30,31,32,47,48,49,50]. This differentiation is due to the different needs of each evaluation. Questionnaires alone [47,48,49,50] or mixed with interviews [30,31,32] are commonly used. In most cases a scenario was conducted by the participants before the completion of the questionnaire. The objective in the studied evaluations is mostly the system usability and just in one case the educational impact [49]. Students are the most commonly used population due to their availability and specializations. In cases where real system impacts are investigated, there are a number of approaches that use students and general population as research samples [31,48]. Each described evaluation methodology, measures selected criteria using the best suited qualitative or quantitative instruments in one or more phases. Evaluation factors were adopted from multiple sources (theories, methodologies or models). Frequent measured factors are the Intergenerational Dialogue, the Intention, the Satisfaction, the Exploitation, the Dissemination, the Belonging, the Perceived ease of use and the Perceived usefulness. Perceived usefulness and Perceived ease of use are two independent constructs in the Technology Acceptance Model [51]. Intention is a key factor in the Theory of Planned behavior [34]. Belongingness is highly correlated with memory. Assmann states that “if you want to belong, you must remember” [52]. Also, in [53] the positive impressions about the city heritage led to increased personal belongingness. The Intergenerational Dialogue is studied in [54], proposing an intergenerational exchange process with positive results. Satisfaction is a factor in the context of Information systems success model [55] and was studied in [53] with positive results. The dissemination of the system, and thus the motivation for using the system, is adopted by Self-Categorization Theory [56]. Exploitation of intangible cultural heritage is underpinned in [57] with the theory of constructivism authenticity, which emphasizes both the authenticity of tourist experience and toured objects.

3. Design Goals

In this stage, we tried to accomplish two main goals: (i) understand if the problem of memory management with modern technology is important for refugees or refugee descendants, and (ii) create and evaluate a set of specified system design goals with respect to their actual needs. Cooperating with a group of field specialists, who in this case were historians, we designed a questionnaire aimed at the volunteers. The historians were secondary education teachers and university professors relating to refugee historic memory issues. The target group was 8 females and 6 males 30–60 years old (average 45.7 years old), all refugees and descendants of people who suffered the war in Asia Minor. The participants were asked to fill in a questionnaire. A semi-structured interview followed in order to provide them with the opportunity to note anything they wanted to say and clarify any issues regarding the questionnaire. All of the participants were using smart phones or tablets in everyday life, and most of them (92.9%) were using social networks. Also, most of them would use a smart phone app to digitize material in order to upload it. The questionnaire consisted of three sections: demographics and Information and Communication Technology (ICT) skills, detecting the way of life of relatives before the events (Table 1) and finally memory management (Table 2).

Table 1.

The Life Before the Events.

Table 2.

Memory Management.

In Q1 most of the refugees came from Smyrna (64.3%) and the rest of them came from Pontus (35.7%). Items Q2, Q3 and Q4 refer to the relationship between the two communities in that land (Greek and Turkish). Most participants answered that these communities had good relations with few incidents between them and also that family relations between the communities were at a good level. Q5 reveals that refugees did not manage to carry with them their personal belongings (92.3%) and finally Q6 indicates a variation in the way that the local Greek population welcomed them (hostile behavior 42.9%, friendly behavior, 14.3%, and indifferent behavior, 42.9%).

Table 2 illustrates the results of the analysis of answers to the distributed questionnaires. The calculated Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to 0.830. All items refer to negative (0) or positive (1) reaction. Nearly half of the population believes that people forget or do not remember what happened there (40%). The majority of them would like to read stories from that period (M3) and all of them would like to learn more about the past of their ancestors (M4). In M5, M6, M7, M8, M9 indicate the need for an information system to be used in order to manage and diffuse this information.

In the semi-structured interview, they indicated that:

- they were happy to hear that a memory management system was planned;

- they want to preserve their memories and want their children to know about their routes.

From the evaluation results at this stage, we realized that the creation of a system that manages memories was a necessity. The system’s volunteer target groups said that they carry memories and are willing to share them, not only for preservation, but also for educational purposes. These results were also a starting point for building the system’s design goals. Content soundness, user participation, user awareness and the use of the content for educational purposes were all factors important for our target group. Consequently, similar systems were studied and analyzed [8,18,26,30] regarding design goals and system features that would be of interest to users. A session of interviews with the volunteers followed in order to enrich their previously stated goals targeting the system’s functionality. Interviews were also conducted with the historians’ group in order to clarify the system design goals obtained by volunteers. Table 3 demonstrates with √ the system goals firstly identified by the volunteers and the system goals of similar systems. With x we mark the goals that came out after the interviews with the volunteers and historians.

Table 3.

Design goals. S1 is “Europeana 1914/18” [26], S2 is “HistoryPin” [8], S3 is “1001 Stories about Denmark” [18] and S4 is MOSAICA [30].

A detailed description of the desired design goals is follows:

- Content soundness: the content validity is a desired quality metric of the contributed content.

- User participation: the user can contribute content in the form of memories, comment on other user memories and propose specific classifications of content.

- Authoring: expert users can author contributed content.

- User awareness and loyalty: support of rich multimedia content and provision of services that supports the building of a sustainable ecosystem for the fruitful exchanging of memories.

- Collections of content: users can create their own content collections using their material and content contributed by other users according to their interests.

- Security: the system provides an authorization mechanism for content access.

- Mobile users and services: the system offers services through a mobile interface for recording and disseminating purposes.

- Search and filtering: support of various search and filtering methods oriented to specific user groups’ needs.

- Navigation and usage: easy to use navigation tools (such as maps and lists).

- Educational content: content can be used for educational purposes in local history classes.

- Multimedia content: support of various types of content (text, audio, video, images).

- Content rating: content can be rated by other users for recommendation purposes.

- Content full ownership by users: content can be uploaded and deleted according to the content owner’s will.

This stage was helpful to evaluate the credibility of our hypotheses concerning design goals and then refine them accordingly. We adopted all goals that were stated by the volunteers and the most common goals of the other systems.

4. System

4.1. Architecture and Implementation Technologies

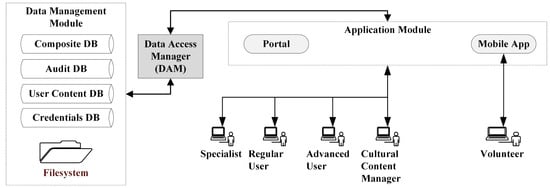

The proposed system architecture (Figure 1) is based on a model where data, application logic and presentation exist in separate modules. The system’s data management module contains several databases (DBs): Composite, Audit, User Content and Credentials DB. Direct database access is prohibited. Any access to the data is mediated by the Data Access Manager and is recorded in the Audit DB. The User Content DB contains all unpublished uploaded data and the Composite DB contains all published content. Application Module contains all services that interact with Data Access Manager and provide all needed information to the users. The same module contains the system interface. Screens were designed to interact successfully and efficiently with the users. The Application Module consists of two different modules: a portal and a mobile app. The portal is mainly aimed at information management and dissemination, and the mobile app is aimed at information gathering.

Figure 1.

System architecture.

The system supports user categorization extending RBAC model [58]. The basic user categories are System Audience—SAU (Regular Users, Advanced Users), Information Producers—InP (Volunteers, Specialists) and Regulators—REG (Cultural Content Managers). Users can perform tasks on both portal and mobile app. Each user role can access custom services:

- Regular User (RU): these are not registered users and can freely access published stories.

- Advanced User (AU): these are registered to the system. They are able to both access published stories, as well as share them on social media and create their own lists of stories. They can also participate, along with other users, in forums discussing the uploaded material.

- Volunteer (VOL): these are people that can contribute content to the system and also manage that content. They can decide whether or not to make their stories visible to the public.

- Specialist (SPE): specialists need to be registered and can perform rating and annotation on stories. These users are professionals in the fields related to cultural heritage.

- Cultural Content Manager (CCM): these managers supervise the system. They can manage all uploaded content and can assign roles to registered users.

The main database content is produced by volunteers and is about the stories (generic content). However, SPEs, AUs and CCMs can create their own content (user content). The generic content can be of any media type (images, audios, videos, texts, coordinates) and along with the user content, facilitates the generation of the composite content. For example, a volunteer adds a story and can attach a video file showing the place of the story, a picture of an official document and an interview. Data contain context attributes related to content (such as story title and story description), and model (such as viewing rights and user roles). All content can be classified in a number of databases:

- User Content DB (UC) holds stories uploaded by VOLs and are ready to be published.

- Composite DB (COM) has the published VOLs generated data. These data can be annotated by SPEs or CCMs. These data are also manageable (delete, unpublish) by CCMs. Finally, the collections created by AUs are stored here.

- Credentials DB (CRE): Data regarding authentication and user’s role information.

- Audit DB (AUD): A database, for security purposes, that contains a recording of user actions in the system.

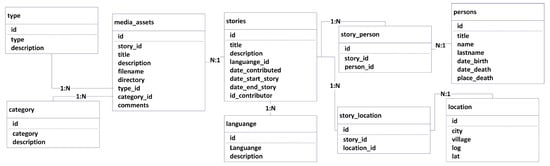

In Figure 2, we illustrate the architecture of the User Content database that stores the stories uploaded by volunteers. The basic database entity is the story. Mandatory fields are the story title, the story description and information related to its context, such as the date that the story begins and ends. Volunteers can attach media files that are related to the story (postcards, images of documents, photographs, etc.). Each story may also be related to a number of persons and to a location.

Figure 2.

User Content Database.

The basic operations on data are: View, Search, Delete, Insert, Edit, Annotate, Rate and Publish. The cultural content manager is only responsible for assigning rights on different types of users. The authorizations control mechanism that is related to these operations is well described in a preliminary version of the system [37].

The system was implemented using open source technologies intending to show that the system creation is low cost. MariaDB was used for databases and a filesystem was hosted in an apache server. For data accessing, PHP services were created. The presentation layer, also containing the business logic, was built using edge technologies. Specifically, the mobile app was created using Ionic Framework, which is capable of producing applications for all mobile platforms. The version used was Ionic 3. The test platform was an android mobile phone with android 7.0. Angular6 was used for the implementation of the portal creating a single page application installed on a filesystem of an Apache web server. The development was held on a computer with operating system Windows 10 and equipped with an i5 CPU and 8 GB ram installed.

4.2. System Services

System services are classified in three categories depending on the users’ access point: Common (both portal and app), Portal and App services.

Common services facilitate user needs and can be accessed through all system entry points:

- System Registration provides the tools for registering the system helping the user to obtain a specific role.

- Authorization facilitates the assignment of the five distinct user roles that are offered by the system. CMMs are obligated to assign roles to new or existing registered users.

- Story Search is available to the SAU group. This service can be held with the use of a map or a keyword-based procedure. Both ways end up on a list where SAUs can select the desired story and see more detail.

- Story View helps SAUs to access story details such as story title, description, related media files and people.

- Collection Creation is dedicated to the AU group and helps them create a list of their preferred stories. Rating Service is responsible for the rating of the published material is provided to SAU.

- Help is offered to the users in the form of advice on the home screen.

Portal services are necessary for the management and the dissemination of the contained stories:

- Annotation can be made by SPEs and CCMs. These users can intervene by adding their comment to the VOLs.

- Material Download helps users download all desired information using the portal.

- Edit Service helps VOLs edit their uploaded unpublished stories and also helps CMMs and SPEs to alter any of their annotations.

- Social Media Sharing is a service that provides story dissemination to existing social networks and is available to all users.

- Advanced Delete facilitate VOLs and SPEs deleting their own uploaded material.

- Authoring: An authoring mechanism is provided to CMMs to ensure the quality of the published material. CMMs can delete stories that they judge to be irrelevant or offensive, or unpublish these with a note requesting improvement and give appropriate advice to the VOLs.

App services are mainly responsible for the gathering of stories by VOLS. App services can be used after downloading the corresponding app on a user’s smartphone. VOLs can:

- Add new stories and story related content to the system.

- Update Service allows any change to inputted story information.

- Delete Service allows story owners to delete their stories.

- Publish and Unpublish Services allow users to make their stories visible to the public and vice versa. UGC DB holds unpublished stories and the COM DB has the published ones. The story transfer between these databases offers the visibility of the story or not.

5. Usage Design Scenarios

Four usage scenarios are presented in this section to show the system’s functionality related to VOLs, SAU. The case study refers to a group of refugees and their descendants that moved to Greece after the "Asia Minor Disaster" at the end of the first quarter of 20th century. The whole incident was traumatic for this population of refugees. The goal of this case study was the collection and dissemination of content including object images, tradition videos and interviews.

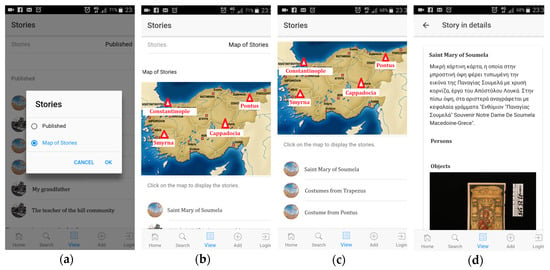

5.1. First Scenario: Audience Searches for a Story Using Map

The user wants to search and view a story that is relevant to a place. She/he chooses the tab “view” and published stories are immediately shown. At the top of the screen she/he taps on the dropdown menu and chooses “map of stories” (Figure 3a). A map is shown to the user, indicating places of interest (Figure 3b). In the implemented case the regions are “Smyrna”, “Constantinople”, “Cappadocia” and “Pontus”. Her/his intention is to view a story unfolding in “Pontus”. She/he taps on the map, in the region of “Pontus” and below the map stories related to that region are displayed (Figure 3c). She/he is interested in the story about a monastery in a place called Sumela. The only action that remains to be done is to tap on the desired story and its information will be displayed (Figure 3d). The user can rate the story.

Figure 3.

Viewing a story: (a) Selecting map; (b) Map with places of interest; (c) Stories related to a place; (d) Story details.

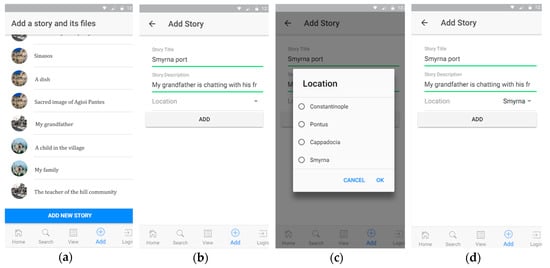

5.2. Second Scenario: Volunteer Adds and Publishes a New Story

A VOL wants to insert a story along with some photographs. The first step is to login to the app to access the volunteer functionality. The volunteer taps on “Add” tab (Figure 4a) and she/he is then prompted to put information regarding the title of the story, its description and location (Figure 4b). The location contains a list of radio buttons with predefined values (Figure 4c). These values have emerged from the questionnaire addressed to the system target group. The story now can be added by pressing the “Add” button (Figure 4d).

Figure 4.

Adding a story: (a) Main add tab; (b) Completing fields; (c) Choosing a region, (d) Submitting the story.

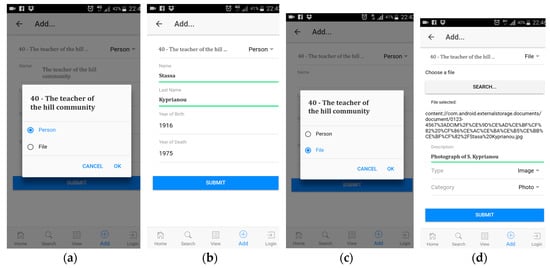

An added story is not published immediately. After it is saved, it is stored in the unpublished stories list. In order to be published, additional information should be added by the volunteer-owner. Volunteer chooses to add a person (Figure 5a) filling corresponding information (such as name, surname and year of birth) and then taps on the submit button (Figure 5b). Also, she/he adds a photo of the person by choosing the “file” from the list (Figure 5c). Next, she/he adds all required information in the fields (Figure 5d). As soon as she/he has completed importing data about connected persons and objects, she/he taps on “submit” button to complete the data import (Figure 5d).

Figure 5.

Adding story details: (a) Add a person; (b) Person fields; (c) Add a file; (d) File fields.

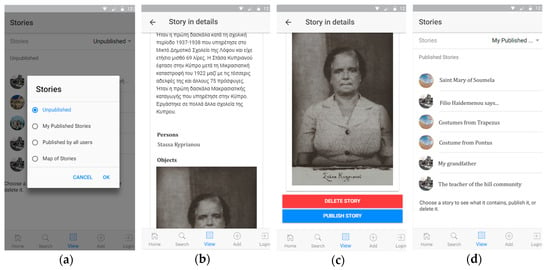

The volunteer locates the story to be published in the unpublished stories list (Figure 6a) and then she/he displays its details (Figure 6b). At the end of the story the option “Publish” is available and the user taps on it (Figure 6c). The story automatically is included in the published stories list (Figure 6d).

Figure 6.

Publishing a story: (a) Locate the story; (b) display story details; (c) Tap on publish button; (d) The story is published.

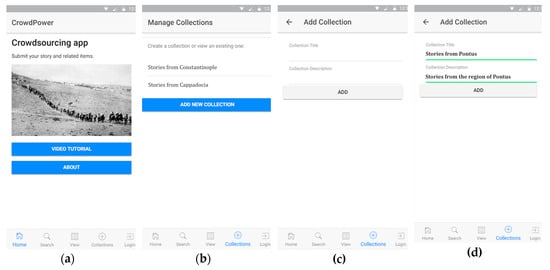

5.3. Third Scenario: Advanced User Creates a List of Stories

An AU wants to create a list of stories regarding the region of “Pontus”. First, she/he must log in the app with her/his credentials. The advanced user can now see that the tab named “Add” has changed to “collections” (Figure 7a). After the AU taps on the “collections” tab, she/he can see a button named “Add New Collection” (Figure 7b) and a list of collections that already exist in her/his portfolio. AU taps on “Add New Collection” and she/he is being forwarded to a new screen (Figure 7c) where she/he enters all needed data (Figure 7d). In this case, the user enters a collection named “Stories from Pontus”.

Figure 7.

Creating a collection of stories: (a) Connected as advanced user; (b) Add new collection; (c) Add collection screen; (d) Entering collection information.

The moment she/he taps on “Add” button (Figure 7d), the new collection is added (Figure 8a). She/he is now able to add stories to that collection. To do so, AU needs to tap on the “View” tab, view the details of a story and then click “Add to collection” (Figure 8b). A popup with the AU’s collections appears and she/he selects the desired collection (Figure 8c). The story then is added to the collection. To view the specific collection, the users should click on “Collections” tab (Figure 8d).

Figure 8.

Adding a story to a collection: (a) Locate the story; (b) Display story details; (c) Tap on publish button; (d) The story is published.

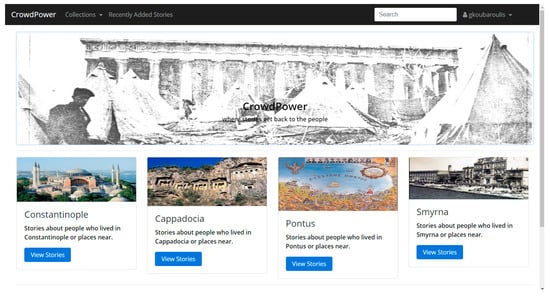

5.4. Fourth Scenario: Specialist Annotates a Story

The portal’s first page contains a menu item called “Collections” and it is available to all visitors. This menu includes some story categories. Stories are categorized depending on the region of origin, the type of included digitized material (such as videos, audios, images) and the category of digitized material (such as postcards and letters). The default categorization is by region as shown in Figure 9. In this scenario, a specialist is going to annotate a story. After she/he logs in, her/his name is shown at the upper right corner and menu items are automatically added depending on her/his role. The connected user is a specialist and the menu that is added is “Recently Added Stories”. This option lists all stories that are recently added, published and are not yet annotated. All stories listed here are already published by volunteers. The specialist selects that menu and the list of stories is being displayed. Each list item contains information about the story name, the name of the volunteer, a check indicating if the story is already annotated (and if so, who did the annotation). Clicking on a story shows all its contents, such as story’s name, description, the associated files and individuals. At the end of the story there is another framework where the specialist can write her/his comments on the story. These comments may be chosen to be available for viewing or not by regular users or even the volunteers who uploaded the stories.

Figure 9.

The first page of the portal for a logged in specialist.

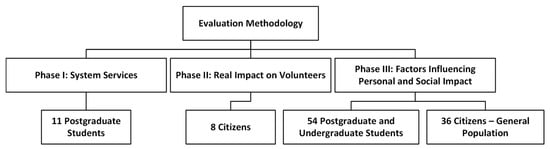

6. Evaluation Methodology

An evaluation methodology was followed throughout all the phases of the system creation (Figure 10). These phases include the evaluation of system features, real impact of crowdsourcing services on volunteers, and finally the personal and social impact to the audience. The tools where selected depending on the available time, the available population and population type. The aim was to produce, in each phase, reliable and useful conclusions. Whenever refugees or refugee descendants were used as an evaluation sample, we chose inhabitants of Agios Konstantinos, a suburb of the city of Agrinio in Greece which was established by the Greek state at the first quarter of 20th century with refugees coming from all parts of Asia Minor and Constantinople (Smyrna, Cappadocia, Pontus, Constantinople).

Figure 10.

Evaluation phases.

The first phase aims to assess the proposed system’s basic features and services, comparing them to well-known systems that offer crowdsourcing services in CH. In the second phase we try to evaluate the real system impact on prospective volunteers. We try to trace whether the system achieves suitable levels of engagement and cultivates responsibility for content contribution. The third phase investigates the system’s personal and social impact to specific user communities (undergraduate/postgraduate students and general population). The third phase also tries to make a first trace of specific correlations among specified personal and social impact factors. The personal and social impact factors investigated in the evaluation phases 2 and 3 are defined in Table 4.

Table 4.

Personal and Social Impact Factor Definitions.

6.1. First Phase (Ph1): System Services Evaluation

This task was assigned to a group of eleven postgraduate students of the Department of Cultural Heritage and New Technologies of the University of Patras specialized in CH digital systems. Students were given the prototype and they were asked to record the services offered following the proposed usage scenarios in this work. Then, they were asked to find similar systems and compare them using a quantitative method evaluation. The criterion was just the existence of the specific service features in all the systems.

The compared systems apply CS methods for collecting cultural content. Table 5 contains the systems to be compared. Students chose to compare the proposed system with S1—“Europeana 1914/18” [26], S2—“HistoryPin” [8], S3—“1001 Stories about Denmark” [18] and S4—MOSAICA [30]. The criteria to be compared concern both portal and mobile services that some systems may possess. M marks the availability of the service in a mobile environment and P on the system portal.

Table 5.

Mobile app evaluation.

Table 5 shows the findings concerning the existence, or lack of, system features and services. The proposed system contains functionalities for both portal and mobile app module. Functionality availability in both mobile and portal is recorded also for S3 but is totally absent in the rest of the cases. S1, S2, S3 and S4 do not contain functionality to unpublish or delete uploaded content. S1 and S4 do not contain any rating service or the ability to create collections. Help in the form of an explanatory video was not present in most of the cases. The absence of mobile module, in most systems, providing the requested services is obvious. The mobile app, when present, contains portal functionalities (S3). This phase confirms the hypothesis that mobile apps can offer CH services.

6.2. Second Phase (Ph2): Personal Impact on VOLs

George (50 years old): “My ancestors came from Pontus and Asia Minor. I believe that it is worthwhile to save the testimonies, the photographs and the objects not only because they are important historical documents for study by historians, but also for cultural, folkloric and other reasons”.

During this phase, the system was demonstrated to a group of people that could be prospective volunteers to the system. A mobile device containing the systems app was given to each one of the prospective volunteers (participants). The task was to accomplish the basic scenario of adding and publishing a new story (second scenario). Then a semi-structured interview was held to get information about systems real impact. We chose to use semi-structured interviews to detect the system’s impact on volunteers, due to the age of volunteers who were refugees or immediate descendants of refugees (there was an assistant for the elderly volunteers on the system use). Also, interviews permitted us to discover the emotions caused by the interaction with the system. This approach was followed in [30,31]. In this phase, 6 interviews were taken.

The sense of belonging was determined to be strong in all participants. They mentioned that they are proud of their legacy. Most of them participate in annual festivals, learn their dances by going to dance clubs, they are subscribers to the newspapers of their clubs and some of them even speak their ancestor’s dialect. Their nostalgia for the old days is obvious. Popi (60 years old) said: “I am an active member of our community. I think our past is special and we have to preserve it”.

Intergenerational Dialogue: Most of the participants started thinking of the value of the memories concerning their ancestors or past lives. Popi said: “I think that I should start asking my mother to tell me her stories with details”. Ioannis (55 years old) told us: “there is a newspaper dealing with these things in my village. I never had the chance to write something there. I will definitely ask my father to tell me stories”. Alexis (96 years old) mentioned: “Every day, I tell my grandchildren stories. I am going to tell more to write them down.”

Dissemination: Participants declared their willingness to spread the system to their relatives and friends due to the opportunity this platform gives to contribute their memories or view content about their origins. George said: “I am going to tell all my friends about the existence of this system”. Alexis told us about how his friends/refugees deal with historical memory: “My village people contribute a lot of material to the local newspaper. As soon as they find out about this system, they will start uploading dozens of stories regularly”.

Intention: All participants declared their willingness to use the platform and contribute their memories. Maria (60 years old) told us: “I used the mobile app and I added a story. I will add a lot of stories with photos of the things that my parents brought with them”. Ioannis mentioned: “Ι have a lot of stories written from my parents. I am going to add them all to the system”. George said: “I am willing to transcribe stories I heard from my ancestors in the system”. Alexis said: “…in order to write them down in this platform”. Popi told us: “…I will tell to write them down in this system”.

Perceived ease of use: Older people could not use the system, but people between the ages of 50 and 65 completed the task easily. They declared that the system was easy to be used by people like them. Giannis (54 years old): “I saw that it is easy to publish stories in that system”. Ioannis said: “I didn’t need to use the help. It was clear how to publish a story”. Alexis told us: “I can’t use a smartphone, you know, it is difficult for me”.

Perceived usefulness and exploitation: Although perceived usefulness and exploitation refer to separate indicators in almost all cases the answers of the participants were in the same sentence. Most of them declared that the system is useful to them. Some users expressed their thoughts of using the system for other reasons (in educational system). Maria told us: “The application is not only useful for us refugees but also for students”. Ioannis said: “is very useful for those who want to post stories but more for those who want to study our story like historians or students”.

Satisfaction: All participants were satisfied from the existence of such a system. Ioannis said: “I always wanted to find a platform where all refugees could upload their stories”. Popi told us: “I am very pleased that the stories of our ancestors can be preserved and disseminated”. George: “I know a lot of stories and I didn’t know how to record them to let the people know about them”.

The above interview fragments are presented to demonstrate a quantity of the interviews’ recordings regarding the CS module. The qualitative tool (semi-structured interviews) revealed not only the prospective volunteers’ intentions but, also, suggested explanations about them. Also, during the interview, an observation sheet was filled out where the participants’ feelings were written down: Emotion, nostalgia and a spark in their eyes appeared when they thought that everything they know or lived can be preserved forever.

6.3. Third Phase (Ph3): Personal and Social Impact on SAUs

This phase was conducted in a group of students specialized in CH management systems and a general population group (Table 6). The first group consisted of 54 undergraduate and postgraduate students (STU) of the Department of Cultural Heritage Management and New Technologies of the University of Patras. We used a questionnaire based on personal and social impact factors defined in (Table A1). We chose as evaluation sample students who have a professional interest in cultural heritage because we wanted to study the system’s impact to specialized groups of users who are experts of this field. Also, we study the system’s impact to a general population (GeP) that had no special relation to CH trying to trace if the system’s value is similarly recognized from a general audience that maybe has no relation to the specific collective memory. All those results are compared together aimed at understanding the real impact of our system to focused communities or not (Table 7).

Table 6.

Demographics.

Table 7.

Evaluation of diffusion module.

All factors get high scores for both groups. STU compared to GeP gets a slightly smaller percentage in Intergenerational Dialogue, Exploitation, Dissemination, Satisfaction, Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Ease of Use. Τhere is a case in which the opposite happens. For Intention, the percentages are slightly smaller for GeP. Finally, for Belonging, the percentages are recorded to be higher by 10 percentage points for GeP. This phase showed that system can be considered successful since, in different population groups, personal and social factors (Intergenerational Dialogue, Exploitation, Dissemination, Satisfaction, Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Ease of Use) get high positive scores.

To investigate social and personal impact factor correlations with each other, we performed a preliminary statistical analysis using Pearson correlation method. Considering the Pearson’s correlations with p value <0.01 we reached some first interesting results that may suggest specific interactions among certain social and personal factors. Particularly, Satisfaction affects intention (0.488 for STU and 0.524 for GeP) and depends on Perceived Usefulness (0.427 for STU and 0.356 for GeP). Also, Satisfaction is affected by Exploitation (0.510) only in STUs and by Perceived Ease of Use (0.404) only in GeP. As concerns Intention for real use, this is affected positively by Satisfaction and Ease of Use (0.379 for STU and 0.633 for GeP) in both groups. However, on STU intention is affected additionally by the possibility of Exploitation (0.598), Intergenerational Dialogue (0.325), Belonging (0.301), Perceived Usefulness (0.513), while on GeP intention is additionally affected by Dissemination (0.689).

Dissemination depends on perceived ease of use (0.523) and Satisfaction (0.496) in GeP, while Dissemination affects Exploitation (0.443) and Intergenerational Dialogue (0.392) in STU. Intergenerational Dialogue promotes Intention (0.325), Exploitation (0.423) and Dissemination (0.392) only in STU. The sense of Belonging to a community is strong in both groups and it is affected by Perceived Usefulness (0.355) in STU and Exploitation (0.559) in GeP, and it also affects Intention in STU. Exploitation is affected by Belonging only in GeP. Also, Exploitation is affected by Intergenerational Dialog, Perceived Ease of Use (0.376), Intention, Dissemination (0.443), Perceived Usefulness (0.738) and Satisfaction in STU. Perceived Usefulness is affected positively be Perceived Ease of Use (0.396) in STU.

7. Discussion

The proposed evaluation methodology is conducted in three phases and follows the course of the creation of the system. The goals for each phase were clear. The whole project was dealing with an innovative system that would manage traumatic memories. The first phase was in the point where the system’s first development should be evaluated in order to see if its design meets the standards that other systems pose. Second and third phases were conducted after the full implementation of the system. Although, the system provides services to a number of user types, in this work, we deal with users who might be volunteers or system audience.

Evaluation revealed that the Intergenerational Dialogue is promoted by using the system. Interestingly, this result confirmed by volunteer interviews and student group. However, this was not apparent to the general population. An explanation could be that students are specialists in CH and along with volunteers, they are familiar to the importance of CH. On the other hand, the selected case study of Asia Minor Refugee memories may be not familiar with the general population memories. Therefore, it is suggested that Intergenerational Dialogue acts complementary to the collective memory that is already apparent in a user. If a user is aware of a specific memory before using the system, this memory comes to the surface and triggers dialogue. This suggestion is validated by evaluation findings concerning the relation between Intergenerational Dialogue and intention, Exploitation and dissemination in students. This is further confirmed by volunteer interviews. A positive influence of a memory management system to the Intergenerational Dialogue is mentioned in [32].

The sense of belonging to a community is promoted by the proposed system. Through the interview interaction with volunteers, we observed strong emotions concerning their past memories that connected them with their origins. This sense gets stronger in relation to their age. Also, volunteers mentioned their need to participate in events with members that share the same collective memories. Moreover, volunteers understood the usefulness of such a system preserving their memories, as they indicated their fear that those memories may fade with them. Furthermore, volunteers strongly declared the need for exploiting such a system for the education of the younger generations to their tradition and history. This suggestion is validated by Phase 4 evaluation findings relating the factor of Belonging to a community to the factor of Perceived Usefulness and Intention for students and Exploitation for the general population. The relation between the sense of Belonging to a community with intention to real use the proposed system in student group is a strong indication of the social impact of the system to young generations. The enhancement of the belonging from the use of a memory management system is a positive objective [17].

Satisfaction from the system is recorded in all populations. Volunteers expressed their satisfaction, admitting that the system meets their real needs (to preserve and share their traditions). The usefulness along with the intention of the system use led the general population and students to also declare their satisfaction. Moreover, for students, the satisfaction is affected by the possibility of educational exploitation. Students may believe that systems devoted to CH need to contain this aspect and it is pleasant for them to see the existence of this factor here. On the other hand, the general population is satisfied with the system because they believe that is easy to use, while they intend to suggest its use to others.

Volunteers said they intend to use the system because of its Preservation, Dissemination and Exploitation capabilities. Students and general population intend to use it due to its Ease of Use and the Satisfaction they feel. Also, general population would recommend the system to others, while students think that the system is worth using because it promotes Intergenerational Dialogue and Belonging to a community, and it has capabilities that permit its exploitation as an educational tool in class and for self-education. Those results may reveal that general population has a trivial attitude towards the system, thinking it as an easy and pleasant tool that is worth showing to their peers, while students of cultural heritage management perceive the system useful as a tool with many functionalities that can be exploited for educational and other purposes. MOSAICA [30] states that online communities are difficult to generate content since in many cases users fail to engage in long term engagement.

Volunteers’ interviews suggest that they would recommend the system’s use to people sharing their traditions. Evaluation results suggest that the general population would do the same due to the system’s ease of use and the satisfaction they get. On the other hand, evaluation results suggest that students relate dissemination to the possibility of the system’s educational exploitation and the promotion of Intergenerational Dialogue. It seems that students may care about the educational value of the system more than the general population.

Evaluation results suggest that the possibility of educational exploitation is obvious to all system users. Results for volunteers and general population suggest that the system exploitation can strengthen the sense of Belonging to a community. Furthermore, evaluation results suggest that Exploitation is affected by Intergenerational Dialogue, Perceived Ease of Use, Intention, Dissemination, Perceived Usefulness and Satisfaction in students. Positive results about Exploitation in terms of learning are presented in [49].

During the interviews, volunteers talked positively about the systems’ Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Ease of Use. The usefulness for them was mainly derived from the educational exploitation of the content that they would upload. Evaluation results reveal that students may relate system usefulness with Satisfaction, possibility of educational exploitation and their intention to use the system. On the other hand, evaluation results may suggest that general population relates usefulness with Satisfaction only. Students probably believe that the content of the system is educational. On the other hand, the general population does not see any relation between the aforementioned factors and system exploitation, but they only believe that the system is useful because it satisfies them. This may suggest that they are not familiar in learning using digital platforms. As for the Ease of Use, the two populations relate it positively with the intention. They probably intend to use the system because they feel that it is easy. Another interesting fact is that the general population connects the Ease of Use with Satisfaction and students relate Ease of Use with Exploitation. Perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use are important for checking the acceptance of a system [35] and, also, they were evaluated in a system managing CH content with positive results [32].

8. Conclusions

This work presents management services for collective memory. The system facilitates memory recording, preservation, archiving and dissemination services. The specified design goals were evaluated for their credibility from specialists and refined correspondingly. The developed system was used as a test bed for applying a specific evaluation methodology concerning the soundness of a memory management system and its personal and social impact. The goal of this methodology was to reveal factors influencing personal and social impact not only to diverse audience groups but also to prospective volunteers. These factors can be exploited by specialists to change their working practices concerning the proliferation of real users’ satisfaction and the strengthening of social cohesion.

The proposed methodology, along with the presented system design and implementation could be used for the design and evaluation of collective memory management systems from professionals working in memory organizations. The presented evaluation results could be useful for professionals as a guide for performing specific changes to their working practices. The presented system exploits the power of the crowd for managing memories of a population for a specific event. We plan to apply the system on other situations of collective memories concerning different time periods such as World War II, as it was mentioned by people in the evaluation process. It seems that people feel the need to record, preserve and disseminate the possessions they deem valuable to others. Also, we plan to conduct the third phase of the demonstrated evaluation procedure in the same groups, after a time interval, to estimate if there would be a change in their beliefs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.K. and D.K.; Methodology, K.K. and D.K.; Formal Analysis, K.K. and D.K.; Investigation, K.K. and D.K.; Resources, K.K. and D.K.; Data Curation, K.K. and D.K.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, K.K. and D.K.; Writing—Review and Editing, K.K. and D.K.; Visualization, K.K. and D.K.; Supervision, D.K.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

This research was fully conducted by Konstantinos Koukoulis and Dimitrios Koukopoulos.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Phase 3 questionnaire. Section B: Social and personal impact regarding the platform.

Table A1.

Phase 3 questionnaire. Section B: Social and personal impact regarding the platform.

| Statement | Agree | Disagree | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | I would suggest to my children or ancestors to visit and use the platform | □ | □ |

| 2 | I would help my children or ancestors to use the platform | □ | □ |

| 3 | I would ask an elderly refugee for stories to upload to the platform | □ | □ |

| 4 | I would devote time to prepare and upload content working with a refugee | □ | □ |

| 5 | I would inform the platform managers about information that is not related to refugees | □ | □ |

| 6 | The platform would sensitize me to participate in a collective memory rescue process | □ | □ |

| 7 | I would use the mobile app to upload a story | □ | □ |

| 8 | I would upload an annotation for a story | □ | □ |

| 9 | I would rate a story on the platform | □ | □ |

| 10 | The platform gives users the opportunity to upload stories and photos | □ | □ |

| 11 | The platform interests only refugees | □ | □ |

| 12 | Users are interested in finding stories about their place of origin | □ | □ |

| 13 | The platform helps the users get in touch with their place of origin | □ | □ |

| 14 | I would like a teacher to use the platform for a lesson | □ | □ |

| 15 | I would like to see a story from the platform to a social media network | □ | □ |

| 16 | I am going to talk to people I know about a story I read on the platform | □ | □ |

| 17 | I would publish a story to the social media networks I use | □ | □ |

| 18 | The platform is an educational tool | □ | □ |

| 19 | A platform visitor will learn important information about refugees | □ | □ |

| 20 | I will tell people I know to use the platform | □ | □ |

| 21 | I am going to tell people I know to upload content on the platform | □ | □ |

| 22 | I like the platform | □ | □ |

| 23 | Using the platform has created some emotion | □ | □ |

| 24 | The use of the platform is indifferent | □ | □ |

| 25 | I like platform services | □ | □ |

| 26 | I think that map service is interesting | □ | □ |

| 27 | I believe that the content of the platform is great | □ | □ |

| 28 | It is easy to use the platform services | □ | □ |

| 29 | There is adequate help on the platform | □ | □ |

| 30 | Computer skills are required to navigate to the platform | □ | □ |

| 31 | Searching with a list is very easy | □ | □ |

| 32 | Searching by map is very easy | □ | □ |

| 33 | I’d rather use search based on a keyword | □ | □ |

References

- Unesco. Text of the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/convention (accessed on 25 May 2018).

- Unesco. 11th Session of the Intergovernmental Committee for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/events/11th-session-intergovernmental-committee-safeguarding-intangible-cultural-heritage (accessed on 25 May 2018).

- Sas, C.; Dix, A. Designing for collective remembering. In Proceedings of the CHI’06: CHI’06 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 22–27 April 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, P.; Chan, B. “Putting Broken Pieces Back Together” Reconciliation, Justice, and Heritage in Post-Conflict Situations. Companion Herit. Stud. 2015, 491–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, P. Confronting the past? Negotiating a heritage of conflict in Sierra Leone. J. Mater. Cult. 2008, 13, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giblin, J.D. Post-conflict heritage: Symbolic healing and cultural renewal. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2014, 20, 500–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukopoulos, Z.; Koukopoulos, D. Smart dissemination and exploitation mobile services for carnival events. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2017, 110, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Historypin. Available online: https://www.historypin.org/en/ (accessed on 25 May 2018).

- Angelidou, M.; Karachaliou, E.; Stylianidis, E. Cultural Heritage in Smart City Environments. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2017, 42, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neirotti, P.; De Marco, A.; Cagliano, A.C.; Mangano, G.; Scorrano, F. Current trends in Smart City initiatives: Some stylised facts. Cities 2014, 38, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitamurto, T. Crowdsourcing for Democracy: A New Era in Policymaking. In Crowdsourcing for Democracy: A New Era in Policy-Making; Committee for the Future, Parliament of Finland: Helsinki, Finland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Liu, J. Social Media and Collective Remembrance. The debate over China’s Great Famine on weibo. China Perspect. 2015, 1, 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Savaş, O. Facebook communities about nostalgic photos of Turkey: Creative practices of remembering and representing the past. Digit. Creativity 2017, 28, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanowska, M.; Poland, I. Protecting Kraków’s heritage through the power of social networking. In Proceedings of the ICOMOS Scientific Symposium, Dublin, Ireland, 30 October 2010; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Al Omoush, K.S. Harnessing mobile-social networking to participate in crises management in war-torn societies: The case of Syria. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaitan, M. Cultural Heritage and Social Media. e-dialogos - Ann. Digit. J. Res. Conserv. Cult. Herit. 2014, 4, 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Chew, I.; Haliza, J. Preserving the crowdsourced memories of a nation, The Singapore Memory Project. In Proceedings of the Memory of the World in the Digital Age: Digitization and Preservation, Vancouver, Canada, BC, USA, 26–28 September 2013; pp. 354–365. [Google Scholar]

- 1001 Stories of Denmark. Available online: http://www.kulturarv.dk/1001fortaellinger/en_GB (accessed on 25 May 2018).

- Ruotsalο, T.; Makela, E.; Kauppinen, T.; Hyvonen, E.; Haav, K.; Rantala, V.; Frosterus, M.; Dokoohaki, N.; Matskin, M. Smartmuseum, Personalized Context-aware Access to Digital Cultural Heritage. In Proceedings of the International Conferences on Digital Libraries and the Semantic Web, Trento, Italy, 8–11 September 2009. [Google Scholar]

- The Prow. Available online: http://www.theprow.org.nz/ (accessed on 25 May 2018).

- My Maine Stories. Available online: https://www.mainememory.net/mymainestories/ (accessed on 25 May 2018).

- Estellés-Arolas, E.; González-Ladrón-De-Guevara, F. Towards an integrated crowdsourcing definition. J. Inf. Sci. 2012, 38, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, J. The Rise of Crowdsourcing. Wired Mag. 2006, 14, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, X.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y.; Yang, C.; Lu, L. What? How? Where? A Survey of Crowdsourcing. In Frontier and Future Development of Information Technology in Medicine and Education: ITME 2013; Li, S., Jin, Q., Jiang, X., Park, J.J., Jong, H., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 221–232. [Google Scholar]

- Oomen, J.; Aroyo, L. Crowdsourcing in the cultural heritage domain: Opportunities and challenges. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Communities and Technologies, Brisbane, Australia, 29 June–2 July 2011; pp. 138–149. [Google Scholar]

- 1914–1918 Europeana Collections. Available online: http://www.europeana.eu/portal/en/collections/world-war-I (accessed on 25 May 2018).

- Koukopoulos, Z.; Koukopoulos, D. A participatory digital platform for cultural heritage within smart city environments. In Proceedings of the 2016 12th International Conference on Signal-Image Technology & Internet-Based Systems (SITIS), Naples, Italy, 28 November–1 December 2016; pp. 412–419. [Google Scholar]

- Christopoulou, E.; Ringas, D. Learning Activities in a Sociable Smart City. IDA 2013, 17, 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Palmius, J. Criteria for Measuring and Comparing Information Systems. In Proceedings of the 30th Information Systems Research Seminar in Scandinavia (IRIS), Murikka, Tampere, Finland, 11 August–14 August 2007; pp. 823–846. [Google Scholar]

- Barak, M.; Herscoviz, O.; Kaberman, Z.; Dori, Y.J. MOSAICA: A web-2.0 based system for the preservation and presentation of cultural heritage. Comput. Educ. 2009, 53, 841–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringas, D.; Christopoulou, E. Collective city memory: Field experience on the effect of urban computing on community. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Communities and Technologies, Munich, Germany, 29 June–2 July 2013; pp. 157–165. [Google Scholar]

- Galatis, P.; Gavalas, D.; Kasapakis, V.; Pantziou, G.; Zaroliagis, C. Mobile Augmented Reality Guides in Cultural Heritage. In Proceedings of the 8th EAI International Conference on Mobile Computing, Applications and Services ICST (Institute for Computer Sciences, Social-Informatics and Telecommunications Engineering), Brussels, Belgium, 30 November–1 December 2016; pp. 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.D.D. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: Four longitudinal field studies. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolchini, D.; Di Blas, N.; Garzotto, F.; Paolini, P.; Cantoni, L.; Rubegni, E. Evaluating Usability Assessment Methods for Web Based Cultural Heritage Applications. In Proceedings of the Open Digital Cultural Heritage Systems Conference, Rome, Italy, 25–26 February 2008; p. 67. [Google Scholar]

- Koukoulis, K.; Koukopoulos, D.; Koubaroulis, G. Towards a Mobile Crowdsourcing System for Collective Memory Management. In Proceeding of the 7th International Conference on Digital Heritage-EuroMed 2018, Nicosia, Cyprus, 14 November 2018; pp. 572–582. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmud, F.; Aris, H. State of mobile crowdsourcing applications: A review. In Proceedings of the 2015 4th International Conference on Software Engineering and Computer Systems (ICSECS), Kuantan, Malaysia, 19–21 August 2015; pp. 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Moovit. Available online: https://www.company.moovitapp.com/ (accessed on 25 May 2018).

- Snik, F.; Rietjens, J.H.H.; Apituley, A.; Volten, H.; Mijling, B.; Di Noia, A.; Heikamp, S.; Heinsbroek, R.C.; Hasekamp, O.P.; Smit, J.M.; et al. Mapping atmospheric aerosols with a citizen science network of smartphone spectropolarimeters. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2014, 41, 7351–7358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.L.; Campbell, J. Crowdsourcing motivations in a not-for-profit GLAM context: The Australian newspapers digitisation program. In Proceedings of the 23rd Australasian Conference on Information Systems, Geelong, Australia, 3–5 December 2012; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Owens, T. Digital Cultural Heritage and the Crowd. Curator Mus. J. 2013, 56, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julia, N.; Bartholomew, A.; Eveleigh, A. Modeling Crowdsourcing for Cultural Heritage; Universiteit van Amstrerdam: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Stathopoulou, E.K.; Georgopoulos, A.; Panagiotopoulos, G.; Kaliampakos, D. Crowdsourcing Lost Cultural Heritage. In Proceedings of the 25th International CIPA Symposium, Taipei, Taiwan, 31 August–4 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, I.; Benz, C.R. Qualitative-Quantitative Research Methodology: Exploring the Interactive Continuum; SIU Press: Carbondale, IL, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.B.; Onwuegbuzie, A.J. Mixed Methods Research: A Research Paradigm Whose Time Has Come. Educ. Res. 2004, 33, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylaiou, S.; Economou, M.; Karoulis, A.; White, M. The evaluation of ARCO: A lesson in curatorial competence and intuition with new technology. Comput. Entertain. 2008, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artese, M.T.; Ciocca, G.; Gagliardi, I. Evaluating perceptual visual attributes in social and cultural heritage web sites. J. Cult. Herit. 2017, 26, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylaiou, S.; Mania, K.; Paliokas, I.; Pujol-Tost, L.; Killintzis, V.; Liarokapis, F. Exploring the educational impact of diverse technologies in online virtual museums. Int. J. Arts Technol. 2017, 10, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylaiou, S.; Killintzis, V.; Paliokas, I.; Mania, K.; Patias, P. Usability Evaluation of Virtual Museums’ Interfaces Visualization Technologies; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 124–133. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.; Davis, F. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assmann, J. Communicative and cultural memory. In Cultural Memories; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2011; pp. 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Nosrati, F.; Crippa, C.; Detlor, B. Connecting people with city cultural heritage through proximity-based digital storytelling. J. Librariansh. Inf. Sci. 2018, 50, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wexler, L. Intergenerational Dialogue Exchange and Action: Introducing a Community-Based Participatory Approach to Connect Youth, Adults and Elders in an Alaskan Native Community. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2011, 10, 248–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delone, W.H.; McLean, E.R. The DeLone and McLean Model of Information Systems Success: A Ten-Year Update. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2003, 19, 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, J.C.; Oakes, P.J. The significance of the social identity concept for social psychology with reference to individualism, interactionism and social influence. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 25, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao-yan, D. On Tourism Exploitation of Intangible Cultural Heritage Resource: From the Theory of Perspective of Constructivism Authenticity. Guizhou Ethn. Stud. 2010, 2, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraiolo, D.F.; Kuhn, R. Role-based access controls. In Proceedings of the 15th NIST-NSA National Computer Security Conference, Baltimore, MD, USA, 13–16 October 1992. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).