Ethicametrics: A New Interdisciplinary Science

Abstract

1. Introduction

- EOM and MOE should be combined in EM as an inclusive interdisciplinary science (Section 2). Otherwise, cross-disciplinary improvements are not exploited.

- Insights from both the epistemological and empirical literature should be shared by using multi-level statistical analyses (Section 3.1). Otherwise, biased ethical assessments are obtained.

- Too few articles inside EM, which produce unbiased estimations. EM should be depicted to a greater extent in an interdisciplinary book, by providing unbiased estimations by many scientists in many disciplines (Section 3.2).

- Too few scholars inside EM, which create good or bad examples. EM should be spread to a greater extent in a quantitative Special Issue, by providing good examples from many scientists in many disciplines (Section 4).

2. Methods: What (Definition) and Why (Necessity)

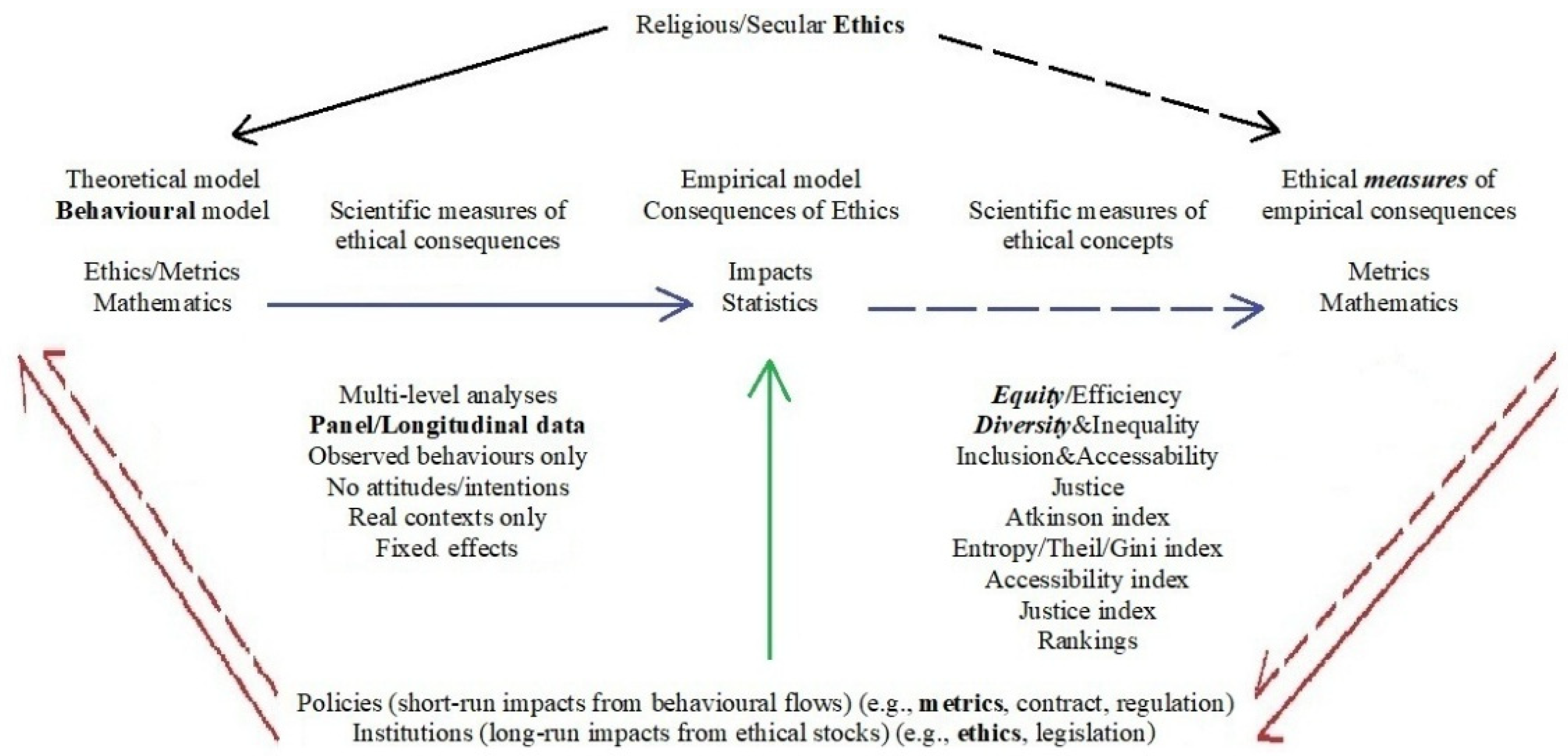

- (dotted blue line) Scientific measures of ethical concepts can be implicit if ethical assessments are obvious. For example, Healthy Life Expectancy at Birth can be assumed to better depict a beneficial impact than Life Expectancy at Birth.

- (dotted black line) Ethical measures of empirical consequences can be implicit if ethical grounds are obvious. For example, a larger increase in Life Expectancy at Birth on average can be assumed to be better than a smaller increase.

- (green line) One observation (of a phenomenon) for many people can have beneficial social impacts (e.g., a tax on cigarettes reduces the quantity of smoke but not the number of smokers), but it is not possible to attach these observations to a specific ethics, since they could be linked to a behavioural flow rather than to an ethical stock (i.e., it amounts to the estimation of the marginal value of a sewing machine in terms of a shirt produced once by many firms in a specific context). Similarly, one observation (of a phenomenon) for one person can have detrimental social impacts (e.g., the arson of an illegal landfill of plastic materials), but it is not possible to attach this observation to a specific ethics, since it could be linked to an occasional behaviour rather than to a behavioural flow. In other words, a quick procedure based on “ethical policies, then ethical consequences” is biased, even if behavioural models and ethical measures are obvious, because it estimates flow rather than stock.

- (dotted red line up) Specific policies should not be starting points, unless they have affected behaviours for many periods in the past.

- (dotted red line down) Specific policies should not be ending points, unless they are expected to affect behaviours for many periods in the future.

- (red line up) Specific institutions could be starting points, if they are included in the behavioural model.

- (red line down) Specific institutions could be ending points, if they are characterised by a specific ethics.

- Some ethics of computer scientists in developing an artificial intelligence software does not need a behavioural model (e.g., the unethical goal could be to influence the opinion of students in favour of Nazism), since few people could behave unethically with unethical and detrimental social consequences (i.e., many observations for the implications of unethical behaviour by few individuals). In other words, computer scientists who alter their artificial intelligence software to increase consensus for a specific political party supporting Nazism could be evaluated in terms of its detrimental impacts on race equity, by relying on many observations in alternative contexts.

- The relative assessment of alternative ethics can be obtained by disregarding the periods of time they are expected to affect behaviours, under the assumption that alternative ethics will last for the same period of time.

- Some ethics of medical scientists in testing new drugs do not need a behavioural model (e.g., the unethical practice could be to test drugs without written acceptance by patients), since few people could behave unethically with ethical and beneficial social consequences (i.e., many observations of the consequences of unethical behaviour by few individuals). In other words, medical scientists who perform unauthorised experiments on people to implement a protocol for improving health conditions could be evaluated in terms of beneficial impacts on the health status of the general population by relying on many observations in alternative contexts.

- The use of ethics to achieve ethical goals (e.g., speeches by priests to increase recycling in [27]) might be an ethical strategy (i.e., the adoption of a specific ethics within a set of alternative ethics).

- Legislation could affect ethics in the long run (e.g., public smoking ban and the number of smokers in [38]).

- Ethics could have a negative monetary value (e.g., ethics as a socially responsible investment is not yet a reliable fundraising tool for Italian-listed companies in [23]) (i.e., ethics is an opportunity cost).

- Risks could have negative ethical consequences (e.g., fraud due to climate change in [21]).

- Metrics can be ranked in ethical terms (e.g., equity from alternative standardisations of the H-index in [4]), whereas ethics cannot be ranked in ethical terms (e.g., Islam better than Christianity in terms of equity), although alternative ethics can be ranked ethically in terms of outcomes (e.g., the observed gender inequity in alternative cultural contexts). In other words, consequentialism could be redundant if some statements about ethics are ethically undisputable (e.g., the sum of citations and articles over time in the original H-index favours old scholars).

- Time-invariant effects, either at an entity level (e.g., each country in [37]) or at a group level (e.g., developed vs. developing countries in [17]), should be used to depict specific unobserved or omitted features and to reduce variability across rather than within entities (i.e., fixed effects > random effects).

2.1. A Scientific Research Area

2.2. An Interdisciplinary Research Area

2.3. Summary

3. Results: Where (Disciplines) and When (Dynamics)

3.1. Epistemology Without Applications

- Make a stringent relationship between quantification and associated contexts or purposes, while avoiding the symbiotic relationship between quantification and trust.

- Be a defence against statistical abuses perpetrated by public or private actors, possibly using consequentialism in ethical quantification.

- Assign responsibilities to social actors when metrics produce unintended or undesirable effects, stressing that techniques are never neutral.

- Bridge scholarship with society by joining scholars from different disciplines within the same methodological framework.

- Bridge social actors with society by using ethical quantification to explain strategically legitimated decisions.

- Specify the purpose of the mathematical model to be statistically validated and tested by reflecting on the ambiguity, indeterminacy, and complexity of the problem under consideration.

- Clarify the ethical assumptions by distinguishing evidence from values to encourage social learning about unfolding possible stakes, biases, interests, blind spots, overlooked narratives, and worldviews of the developers.

- Choose analytical tools that are consistent with the purpose of the model by stressing their inner assumptions.

- Consider the relationship between error and complexity in choosing models and variables by performing sensitivity analyses to favour immediate interpretations.

- Avoid under-specification problems by applying adequate statistical units and methods to properly communicate uncertainty.

- Clarify all ethical implications by highlighting the relationship between power and knowledge.

- Use mathematically grounded metrics to evaluate empirical consequences.

- Use theologically and philosophically grounded ethics to evaluate empirical consequences.

- Check for consistency of ethical assumptions built into mathematical models and ethical principles used in empirical evaluations by performing sensitivity auditing.

- Specify all policy implications by highlighting people or institutions responsible for policy implementations.

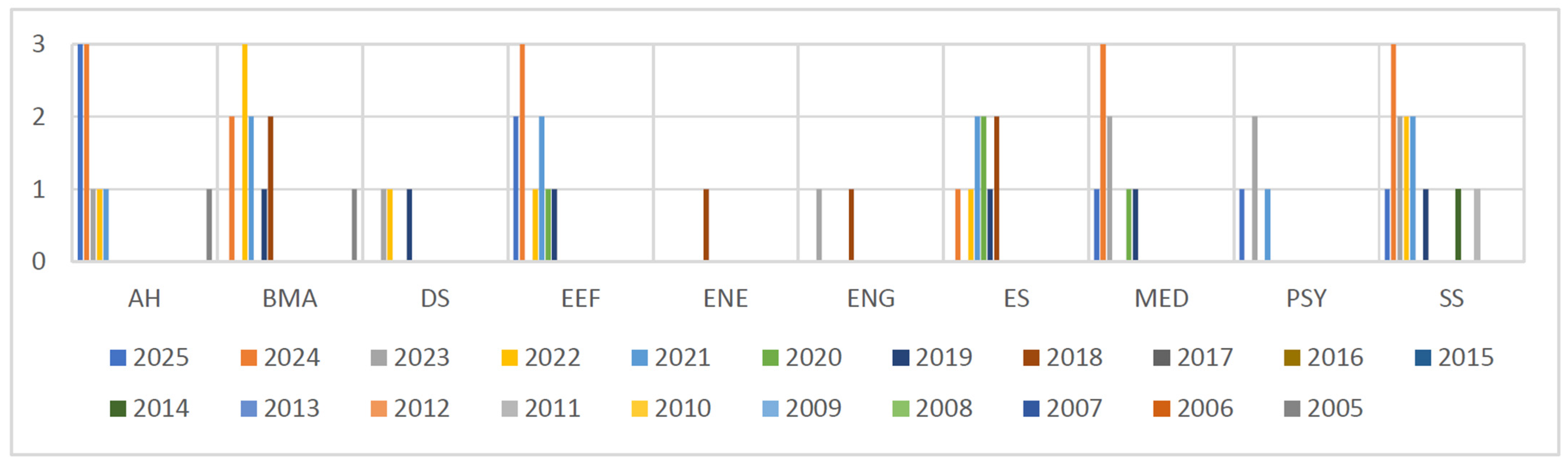

3.2. Applications Without Epistemology

3.3. Summary

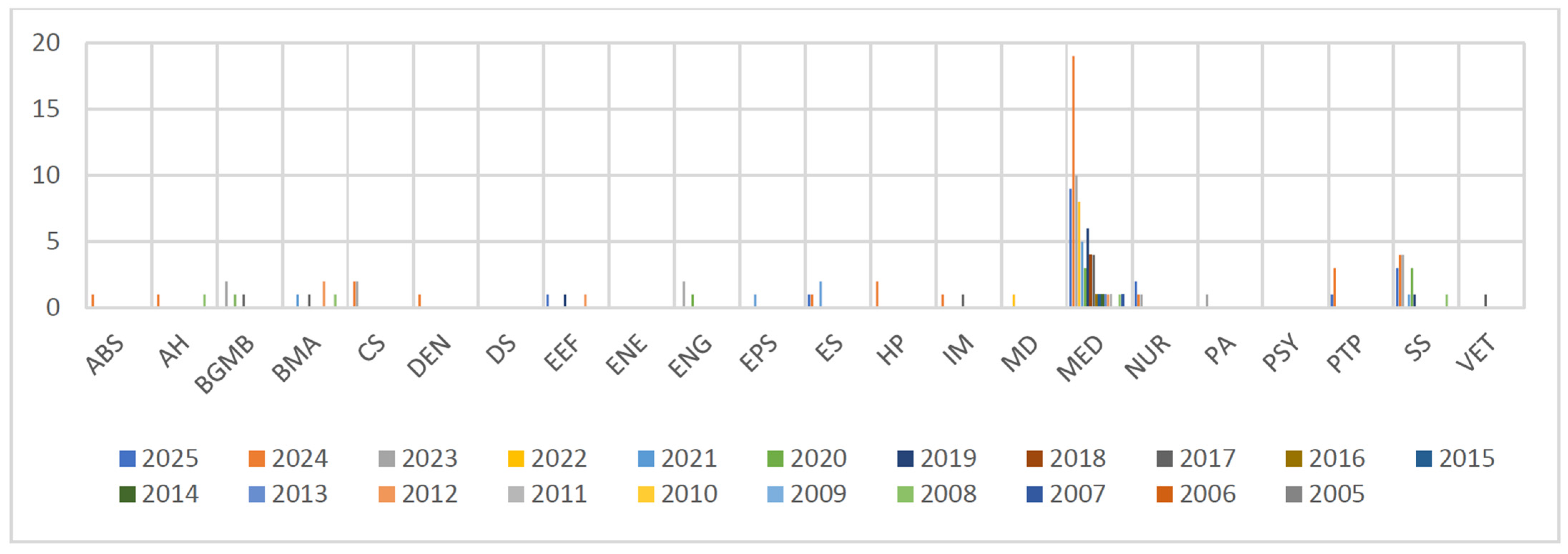

4. Results: How (Applications) and Who (Researchers)

4.1. Perfect Examples

4.2. Imperfect Examples

4.3. Perfect Applications in Alternative Contexts

4.4. Summary

5. Discussion

- Ethics as (a stock of) social values in a behavioural model can be used to assess interactions across groups between alternative social ethics (e.g., Western values in developing countries) and to assess interactions between social behaviours and social institutions over time (e.g., divorce rates in Western countries).

- EM refers to a universal context (i.e., ethics are general rules), although the realism of assumptions in specific cultural contexts leads to more causal models [53]. In other words, EM is closer to socialised habits from Evolutionary Behavioural Economics than to utility maximisation from Neoclassical Economics or to specific cognitive biases from Behavioural Economics (e.g., [54,55]).

- EM is focused on targeted decisions depicted by behavioural models (i.e., ethics are beneficial or detrimental constraints to individual decisions), although ethics represent a social structure with a restrictive or enabling effect on opportunity and flourishing of individuals [56]. In other words, EM is closer to reciprocal transactions from parental bent in Evolutionary Behavioural Economics than to market transactions from self-interest purposes in Neoclassical Economics or to specific cooperative attitudes from Behavioural Economics (e.g., [57,58]).

- EM is deductive (i.e., general models to be tested are based on general rules) by applying an engineering approach (i.e., it is based on mathematics and statistics) to measure and rank ethics [59], but it is also abductive (i.e., explanatory hypotheses are tentative and require verification).

- EM aims at model estimation rather than at model selection, assuming that a correctly specified model enables the achievement of closures of causal sequences, although models are provided by moral philosophy and theology [60]. This requires detailed justifications of simplifying assumptions (LIMIT 1).

- EM aims at causal inference rather than causal discovery [61], where the average impacts (to depict possible interactions at an individual level) at a social level (e.g., to depict share ethics at a country level) obtained from large datasets with fixed effects should be preferred to small datasets with random effects (to account for structural differences in relative importance of ethics). This requires huge efforts in constructing panel/longitudinal datasets (LIMIT 2).

- EM can use instrumental variables [62], although these variables need interpretations and they must satisfy some theoretical conditions, which can be hardly tested in practice (LIMIT 3). Actually, the same instrumental variables could be used as regressors.

- EM can use both frequentist or classical inference as well as Bayesian, likelihood, or Akaikean inferences [63], although these latter inferences (all referring to the Likelihood Principle) require a priori information, a statistical model, and a posteriori criteria (LIMIT 4). Actually, frequentist tools could be used to compare two models at once.

- 8.

- EM is not limited to rational decisions based on the internal consistency criterion and the self-interest pursuit approach by interpreting the rationality of choices as a reason for choices (i.e., free scrutiny of objectives and motivations) [64].

- 9.

- EM does not aim at predicting actual behaviours by avoiding the assumptions of stable and complete preferences, interactions in markets tending to reach an equilibrium, fixed societies, and absence of uncertainty [65].

- 10.

- EM is an evolutionary science referring to an open system (i.e., some outcomes are caused by something that went before them, with cumulative causation and without predetermined purpose) rather than a taxonomic science referring to a closed system (i.e., EM provides empirical generalisations of historical phenomena, where exceptions are interpreted as disturbing factors) [66] by applying a quantitative approach to human motivations and social achievements with an explanatory rather than descriptive perspective.

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Agricultural and Biological Sciences | ABS |

| Arts and Humanities | AH |

| Biochemistry, Genetics, and Molecular Biology | BGMB |

| Business, Management and Accounting | BMA |

| Computer Science | CS |

| Dentistry | DEN |

| Decision Sciences | DS |

| Economics, Econometrics and Finance | EEF |

| Energy | ENE |

| Engineering | ENG |

| Earth and Planetary Sciences | EPS |

| Environmental Science | ES |

| Health Professions | HP |

| Immunology and Microbiology | IM |

| Multidisciplinary | MD |

| Medicine | MED |

| Nursing | NUR |

| Physics and Astronomy | PA |

| Psychology | PSY |

| Pharmacology, Toxicology and Pharmaceutics | PTP |

| Social Sciences | SS |

| Veterinary | VET |

References

- Zagonari, F. Coping with the Inequity and Inefficiency of the H-Index: A Cross-Disciplinary Analytical Model. Publ. Res. Q. 2019, 35, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, G.; Greenwood, M. The Metrics of Ethics and the Ethics of Metrics. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 175, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobles, E.C. The ethical foundations of biodiversity metrics. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2025, 72, 101503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagonari, F.; Foschi, P. Coping with the Inequity and Inefficiency of the H-Index: A Cross-Disciplinary Empirical Analysis. Publications 2024, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltelli, A. Ethics of quantification or quantification of ethics? Futures 2020, 116, 102509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fiore, M.; Kuc-Czarnecka, M.; Lo Piano, S.; Puy, A.; Saltelli, A. The challenge of quantification: An interdisciplinary reading. Minerva 2023, 61, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persad, G. Will more organs save more lives? Cost-effectiveness and the ethics of expanding organ procurement. Bioethics 2019, 33, 684–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsan, M.-F.; Van Hook, H. Assessing the Quality and Performance of Institutional Review Boards: Impact of the Revised Common Rule. J. Empir. Res. Hum. Res. Ethics 2022, 17, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafino, B.A.; Kwakkel, J.H.; Taebi, B. Enabling assessment of distributive justice through models for climate change planning: A review of recent advances and a research agenda. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2021, 12, e721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchione, E.; Chalabi, Z. Is mathematical modelling an instrument of knowledge co-production? Interdiscip. Sci. Rev. 2021, 46, 632–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatto, A. A pluralistic approach to economic and business sustainability: A critical meta-synthesis of foundations, metrics, and evidence of human and local development. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1525–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikerd, J. Business Management for Sustainability. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuc-Czarnecka, M.; Olczyk, M. How ethics combine with big data: A bibliometric analysis. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2020, 7, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Piano, S. Ethical principles in machine learning and artificial intelligence: Cases from the field and possible ways forward. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2020, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunce, A.; Hashemi, L.; Clark, C.; Myers, C.A.; Stansfeld, S.; McManus, S. Prevalence and nature of workplace bullying and harassment and associations with mental health conditions in England: A cross-sectional probability sample survey. Lancet 2023, 402, S2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.-K.; Yeung, J.W.K. Prediction of Youth Violence Perpetration by Parental Nurturing Over Time. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2023, 69, 1081–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagonari, F. Foreign direct investment vs. cross-border trade in environmental services with ethical spillovers: A theoretical model based on panel data. J. Environ. Econ. Policy 2021, 10, 130–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boţa-Avram, C.; Groşanu, A.; Răchişan, P.R. Investigating Country-Level Determinant Factors on Ethical Behavior of Firms: Evidence from CEE Countries. J. East-West Bus. 2021, 27, 184–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakas, D.; Kostis, P.; Petrakis, P. Culture and labour productivity: An empirical investigation. Econ. Model. 2020, 85, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmoula, L.; Chouaibi, S.; Chouaibi, J. The effect of business ethics and governance score on tax avoidance: A European perspective. Int. J. Ethic Syst. 2022, 38, 576–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wen, F.; Xiao, J.; Tian, G.G. Weathering the Risk: How Climate Uncertainty Fuels Corporate Fraud. J. Bus. Ethic 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouaibi, Y.; Khlifi, S.; Chouaibi, J.; Zouari-Hadiji, R. The effect of CSR and corporate ethical behavior on implicit cost of equity: The mediating role of integrated reporting quality. Glob. Knowledge Mem. Commun 2024. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, G.; Sciarelli, M. Towards a more ethical market: The impact of ESG rating on corporate financial performance. Soc. Responsib. J. 2019, 15, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouki, A.; Ben Amar, A. Managerial overconfidence, earnings management and the moderating role of business ethics: Evidence from the Stoxx Europe 600. Int. J. Ethic Syst. 2024. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.-T. The relationship between corporate sustainability performance and earnings management: Evidence from emerging East Asian economies. J. Financ. Rep. Account. 2024, 22, 564–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugraheni, P.; Alhabsyi, S.M.; Rosman, R. The influence of audit committee characteristics on the ethical disclosure of sharia compliant companies. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2022, 9, 2115220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagonari, F. Comparing religious environmental ethics to support efforts to achieve local and global sustainability: Empirical insights based on a theoretical framework. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagonari, F. Only religious ethics can help achieve equal burden sharing of global environmental sustainability. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2023, 80, 807–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagonari, F. Pope Francis vs. Patriarch Bartholomew to Achieve Global Environmental Sustainability: Theoretical Insights Supported by Empirical Results. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagonari, F. Responsibility, inequality, efficiency, and equity in four sustainability paradigms: Insights for the global environment from a cross-development analytical model. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2019, 21, 2733–2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagonari, F. Environmental sustainability is not worth pursuing unless it is achieved for ethical reasons. Palgrave Commun. 2020, 6, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagonari, F. Both de-growth and a-growth to achieve strong and weak sustainability: A theoretical model, empirical results, and some ethical insights. Front. Sustain. 2024, 5, 1351841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagonari, F. Religious and secular ethics offer complementary strategies to achieve environmental sustainability. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021, 8, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagonari, F. Environmental Ethics, Sustainability and Decisions: Literature Problems and Suggested Solutions; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 1–253. [Google Scholar]

- Zagonari, F. An empirical support of Schopenhauer’s ethics: A dynamic panel data analysis on developed and developing countries. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2023, 8, 100706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagonari, F. Both religious and secular ethics to achieve both happiness and health: Panel data results based on a dynamic theoretical model. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0301905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagonari, F. Interrelationships between income and both religious and secular ethics: Panel Data Envelopment and Stochastic Frontier Analyses combined. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2025, 11, 101515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Tsuei, S.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhu, S.; Xu, D.; Yip, W. Effects of comprehensive smoke-free legislation on smoking behaviours and macroeconomic outcomes in Shanghai, China: A difference-in-differences analysis and modelling study. Lancet Public Health 2024, 9, e1037–e1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagonari, F. Decommissioning vs. reusing offshore gas platforms within ethical decision-making for sustainable development: Theoretical framework with application to the Adriatic Sea. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2021, 199, 105409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagonari, F. Scientific production and productivity for characterizing an author’s publication history: Simple and nested Gini’s and Hirsch’s indexes combined. Publications 2019, 7, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagonari, F. Sustainable business models and conflict indices for sustainable decision-making: An application to decommissioning versus reusing offshore gas platforms. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 180–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkert, F.; Sticker, M. Procreation, Footprint and Responsibility for Climate Change. J. Ethics 2021, 25, 293–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowding, K.; Oprea, A. Manipulation in politics and public policy. Econ. Philos. 2024, 40, 685–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, R. Fairness in Machine Learning: Against False Positive Rate Equality as a Measure of Fairness. J. Moral Philos. 2021, 19, 49–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, T. Value creation and CSR. J. Bus. Econ. 2023, 93, 1255–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagonari, F. (Moral) philosophy and (moral) theology can function as (behavioural) science: A methodological framework for interdisciplinary research. Qual. Quant. 2019, 53, 3131–3158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltelli, A.; Di Fiore, M. From sociology of quantification to ethics of quantification. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2020, 7, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltelli, A.; Puy, A. What can mathematical modelling contribute to a sociology of quantification? Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagonari, F. The requiem of Olympic ethics and sports’ independence. Stats (SI on “Ethicametrics”) 2025. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Zagonari, F. Having a body vs. being a body to achieve happiness and health. Stats (SI on “Ethicametrics”) 2025. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Saltelli, A. What is Post-normal Science? A Personal Encounter. Found. Sci. 2024, 29, 945–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Staveren, I. Normative empirical concepts–A practical guiding tool for economists. J. Econ. Methodol. 2024, 31, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.B. Objectivity in economics and the problem of the individual. J. Econ. Methodol. 2023, 30, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanfield, K.C. Evolutionary Behavioral Economics: Veblenian Institutionalist Insights from Recent Evidence. J. Econ. Issues 2023, 57, 693–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munien, I.; Telukdarie, A. Updating neoclassical economics with contemporary conceptions of homo economicus: A bibliometric analysis. Qual. Quant. 2025, 59, 1123–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrova, A.; Northcott, R.; Wright, J. Back to the big picture. J. Econ. Methodol. 2021, 28, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcés, P. Pragmatic behaviour: Pragmatism as a philosophy for behavioural economics. J. Philos. Econ. 2022, XV, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, R.A. Nudges, preferences and competences: A critique of both neoclassical and behavioral economics. Behav. Public Policy 2025, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, M. A more scientific approach to applied economics: Reconstructing statistical, analytical significance, and correlation analysis. Econ. Anal. Policy 2020, 66, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małecka, M. Values in economics: A recent revival with a twist. J. Econ. Methodol. 2021, 28, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, A.R.; Pugnana, A.; Ruggieri, S.; Pedreschi, D.; Gama, J. Methods and tools for causal discovery and causal inference. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2022, 12, e1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, S.M. Econometric methods and Reichenbach’s principle. Synthese 2022, 200, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engler, J.-O.; Beeck, J.J.; von Wehrden, H. Mostly harmless econometrics? Statistical paradigms in the ‘top five’ from 2000 to 2018. J. Econ. Methodol. 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, T.-H. Veblen’s evolutionary methodology and its implications for heterodox economics in the calculable future. Rev. Evol. Politi Econ. 2021, 2, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avtonomov, V.; Avtonomov, Y. Four Methodenstreits between behavioral and mainstream economics. J. Econ. Methodol. 2019, 26, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragkousis, A. Amartya Sen as a Neoclassical Economist. J. Econ. Issues 2024, 58, 24–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleinik, A. Content Analysis as a Method for Heterodox Economics. J. Econ. Issues 2022, 56, 259–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, F. Recent contributions to heterodox economics: Meaning, ideology, and future. Rev. Evol. Political Economy 2024, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianulardo, G.; Stella, A. The concept of relation in methodological individualism and holism: A reply to a functionalist critique. J. Philos. Econ. 2024, 17, 226–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, N. Social Ontology and Model-Building: A Response to Epstein. Philos. Soc. Sci. 2021, 51, 176–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telles, K. Pursuing a Grand Theory: Douglass, C. North and the early making of a New Institutional Social Science (1950–1981). EconomiA 2024, 25, 109–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosino, A.; Cedrini, M.; Davis, J.B. The unity of science and the disunity of economics. Camb. J. Econ. 2021, 45, 631–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neck, R. Methodological Individualism: Still a Useful Methodology for the Social Sciences? Atl. Econ. J. 2021, 49, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Reference | Outside Ethics | Behavioural Model (Maths) | Measure Consequence (Stats) | Ethical Assessment (Maths) | Outside Ethics | Policy Institution | DIS | UNI | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous Black | Ethics or Metrics | Impacts | Metrics | Dotted Black | Dotted Red | ||||

| Zagonari [30] | NO | EXP | FE | EF | Many | NO | ES | COU | 1 |

| Zagonari [27] | REL | EXP | FE | EF | NO | NO | ES | COU | 1 |

| Zagonari [31] | NO | EXP | FE | EF | Efficiency | NO | ES | COU | 1 |

| Zagonari [33] | NO | EXP | FE | EF | NO | NO | ES | COU | 1 |

| Zagonari [29] | REL | EXP | FE | EF | NO | NO | ES | COU | 1 |

| Zagonari [35] | REL/SEC | EXP | FE | LS | EXP | NO | AH | COU | 1 |

| Zagonari [36] | REL/SEC | EXP | FE | LS, HLEB | NO | REL/SEC | AH | COU | 1 |

| Zagonari [37] | REL/SEC | EXP | FE | GDP | Efficiency | REL/SEC | EFE | COU | 1 |

| Zagonari [49] | REL/SEC | EXP | RE | OM | NPE, SCE | NO | AH | COU | 1 |

| Zagonari [50] | REL/SEC | EXP | FE | LS, HLEB | NO | REL/SEC | AH | COU | 1 |

| Zagonari [1] | Outside Metrics | EXP | FE | H-index | Ranking | Improved H-index | DC | IND | 1 |

| Reference | Outside Ethics | Behavioural Model (maths) | Measure Consequence (Stats) | Ethical Assessment (Maths) | Outside Ethics | Policy Institution | DIS | UNI | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous Black | Ethics or Metrics | Impacts | Metrics | Dotted Black | Dotted Red | ||||

| Landi & Sciarelli [23] | NO | IMP | RE | SRI | NO | NO | SS | IND | 2 |

| Bakas et al. [19] | NO | IMP | RE | LP | NO | NO | EEF | COU | 3 |

| Zagonari [17] | REL/SEC | IMP | FE | WM, OF, EC | IMP | FDI, CBT | ES | COU | 1 |

| Boţa-Avram et al. [18] | NO | IMP | RE | PMS, WGS | NO | NO | SS | IND | 3 |

| Zagonari [28] | REL/SEC | IMP | FE | EF | Equity | REL/SEC | ES | COU | 1 |

| Abdelmoula et al. [20] | NO | IMP | RE | TA | NO | NO | BMA | IND | 3 |

| Nugraheni et al. [26] | REL | IMP | RE | CIG | NO | NO | BMA | IND | 3 |

| Bunce et al. [15] | NO | IMP | RE | MH | NO | NO | MED | IND | 6 |

| Cheung & Yeung [16] | NO | IMP | RE | VP | NO | NO | MED | IND | 2 |

| Zagonari [32] | NO | EXP | NO | EF | Many | NO | ES | COU | 1 |

| Marzouki & Ben Amar [24] | NO | IMP | RE | SRI | Equity | NO | BMA | IND | 2 |

| Chen et al. [21] | NO | IMP | RE | FC | NO | NO | BMA | IND | 4 |

| Chouaibi et al. [22] | NO | IMP | RE | COE | NO | NO | BMA | IND | 4 |

| Nguyen [25] | NO | IMP | RE | ME | NO | NO | BMA | IND | 4 |

| Zagonari & Foschi [4] | Outside Metrics | IMP | FE | H-index | Ranking | Improved H-index | DC | IND | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zagonari, F. Ethicametrics: A New Interdisciplinary Science. Stats 2025, 8, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/stats8030050

Zagonari F. Ethicametrics: A New Interdisciplinary Science. Stats. 2025; 8(3):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/stats8030050

Chicago/Turabian StyleZagonari, Fabio. 2025. "Ethicametrics: A New Interdisciplinary Science" Stats 8, no. 3: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/stats8030050

APA StyleZagonari, F. (2025). Ethicametrics: A New Interdisciplinary Science. Stats, 8(3), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/stats8030050