Abstract

Soil contamination by petroleum hydrocarbons represents a significant environmental challenge, especially in industrial and urban areas. This study evaluates the use of three industrial liquid by-products—sludge dewatering sidestream (SD), leftover yeast (LY), and secondary clarifier effluent (SC)—as biostimulant agents for the bioremediation of soils contaminated with gasoline and diesel mixtures. The novelty lies in applying these waste streams within a circular economy framework, with the added advantage that they can be injected directly into the subsurface. Microcosm tests were conducted over 20 weeks, analyzing the degradation of total petroleum hydrocarbons (TPHs) and their aliphatic and aromatic fractions using gas chromatography. The results show that all by-products improved biodegradation compared to natural attenuation. LY was the most effective, achieving 73.2% TPH removal, followed by SD (70.6%) and SC (65.4%). The greatest degradation was observed in short-chain hydrocarbons (C6–C16), while compounds with higher molecular weight (C21–C35) were more recalcitrant. In addition, aliphatic hydrocarbons showed greater degradability than aromatics in heavy fractions. Kinetic analysis revealed that the second-order model best fitted the experimental data, with higher correlation coefficients (R2) and more representative half-lives. Catalase enzyme activity also increased in soils treated with LY and SD, indicating higher microbial activity.

1. Introduction

The synthesis and massive use of petroleum-derived compounds, both in the transport sector and in industry, make these hydrocarbons an essential part of modern life [1,2]. These organic compounds are among the most frequent pollutants in soils and waters (surface and underground) and the number of environmental incidents related to them has continued to increase [3]. Once oil percolates into the soil, it potentially causes substantial ecological disruption, negatively impacting soil microorganisms, vegetation, and even human health [4,5].

According to their chemical structure, gasoline and diesel fuel are divided into two categories by scientists: aliphatic and aromatic. These fuels are complex mixtures containing hundreds of different hydrocarbons [6]. Hydrocarbons such as BTEX (benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, xylenes) compounds and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), are classified as toxic and some of them carcinogenic to human [7,8].

In Europe, hydrocarbons are the source of contamination in upwards of 30% of affected sites [9]. In the United States, petroleum-derived hydrocarbons are estimated to be present in nearly 70% of contaminated soils [10]. In order to address the impacts, physical and chemical remediation methods are often applied, such as thermal desorption, incineration, and other specialized treatments. These approaches are crucial for achieving rapid cleanup and preventing further spread of contaminants [4]. Although conventional strategies enable rapid decontamination and effectively limit pollutant dispersion, these contaminants are often associated with significant financial costs, substantial energy consumption, and adverse impacts on soil structure [11,12]. Consequently, bioremediation has been highlighted as a promising alternative, leveraging the metabolic capabilities of microorganisms to degrade organic contaminants into innocuous compounds, offering a cost-efficient, environmentally sustainable, and non-polluting solution [13,14]. Bioremediation is widely applied in countries such as Austria, Belgium, France, and the United States, accounting for approximately 12% to 35% of all soil remediation techniques. Despite its environmentally friendly nature, bioremediation presents several limitations: it often requires extended treatment periods, its effectiveness is influenced by climatic conditions, and its mechanisms are not yet fully understood [15].

Finding the most suitable soil remediation method depends on several factors, including the type and extent of contamination, the application site (in situ or ex situ), agro-environmental conditions, and soil characteristics [16,17]. Among available strategies for hydrocarbon-contaminated soils, in situ treatments are generally preferred due to their lower environmental impact and cost-effectiveness, as they preserve the soil ecosystem [18,19].

Bioremediation stands out as a sustainable approach, particularly through biostimulation, which enhances native microbial activity by adding nutrients or compounds that accelerate contaminant degradation [20,21]. The addition of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium has proven effective in promoting petroleum biodegradation [22,23]. However, the industrial production of commercial fertilizers supplying these nutrients relies heavily on non-renewable resources such as natural gas and mineral deposits [24,25,26].

To address these limitations, biostimulation using microbial enzymes such as monooxygenases has gained attention for its role in organic pollutant mineralization [10,27]. Industrial by-products offer a promising alternative source of nutrients and enzymes, though their potential remains underexplored [28]. Integrating these materials into remediation practices could reduce costs, support resource sustainability, and align with circular economy principles [29,30].

The use of organic wastes as biostimulating agents has been studied for the remediation of soils contaminated by organic compounds. Some of these wastes are peanut shell [31], sewage sludge, manure [32], municipal solid waste, poultry manure [33,34], soybean texturized waste and orange peel, spent mushroom substrate and sweet potato peel, stabilized poultry litter and effluent from yeast production [35]. However, these wastes are generally solid (except those from yeast production) and require soil excavation in order to come into contact with the contaminants [36]. In the case in which the contamination penetrates several meters below the ground surface, this method seems unsuccessful.

The main novelty of this study is the evaluation of aqueous industrial by-products as biostimulants for the remediation of polluted soil. Furthermore, the introduction of industrial by-products, along with the kinetic modeling, represents an additional innovative aspect of this approach. The valorization of industrial residues for the remediation of contaminated soils constitutes a key strategy within the framework of the circular economy. This approach facilitates the closure of material loops by reducing reliance on virgin resources and minimizing waste generation. By repurposing industrial by-products, otherwise destined for disposal, as functional agents in environmental applications, it promotes industrial symbiosis and transforms environmental liabilities into valuable assets. Such practices directly support the achievement of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 12, Responsible Consumption and Production, by fostering sustainable resource management models. Additionally, they contribute to SDG 15, Life on Land, through the enhancement of soil quality and the restoration of degraded terrestrial ecosystems.

This study investigates the potential of three industrial liquid by-products, (a) sludge dewatering sidestream (SD), (b) leftover yeast (LY), and (c) secondary clarifier effluent (SC), as biostimulant agents to enhance the bioremediation of soils contaminated with gasoline and diesel mixtures. A series of microcosm experiments were carried out over a 20-week period, during which the degradation of TPHs, including their aliphatic and aromatic fractions, was monitored using gas chromatography. A key advantage of these by-products is that they can be administered directly into the subsurface via injection wells. Furthermore, the effect of biostimulants was evaluated by analyzing various hydrocarbon fractions, not just the total petroleum hydrocarbons. The aim of this work was thus to evaluate the suitability of three liquid industrial by-products (including by-products of the brewery, chemical and wastewater industries) for bioremediation of petroleum hydrocarbon-contaminated soils.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Analytical Methods

All hydrocarbon determinations were performed in triplicate. Two analytical methods were used, taking into account whether the compounds analyzed were volatile (C6-C10) or non-volatile (C10–C35). The volatile hydrocarbon group (C6–C10) were determined by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) according to USEPA 8260b [37] and USEPA 5021a [38]. The equipment was a gas chromatograph model 6890N from Agilent Technologies (Madrid, Spain), coupled to a mass spectrometer model 5973 Inert from Agilent Technologies. Samples were sealed in vials and heated at 80 °C for 1 h to allow equilibration between gaseous and solid phases. The headspace was then injected into the GC at 250 °C. Separation was performed on a capillary column (30 m × 0.54 mm × 0.85 µm) using helium as the carrier gas (3.9 mL h−1).

Non-volatile hydrocarbons (C10–C35) were measured with a gas chromatography equipped with a flame ionization detector (GC/FID) [39]. Prior to chromatographic analysis, petroleum hydrocarbons were extracted using Soxhlet extraction, following the standardized EPA 3540 method [40]. Organic compounds in soil were extracted with n-hexane as the solvent. Extracts obtained from Soxhlet extraction were injected into a GC (Agilent Technologies 6890N) equipped with a capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 µm) and helium as carrier gas (10 mL min−1). Injector and detector temperatures were set at 280 °C. The oven program started at 45 °C and increased at 12 °C min−1 to a final temperature of 250 °C. The detection limits (LOD) for aliphatic and aromatic compounds were <2 mg hydrocarbon/kg soil for C6–C8, C8–C10, and C10–C12; <8 mg hydrocarbon/kg soil for C12–C16 and C16–C21; and <12 mg hydrocarbon/kg soil for C21–C35.

All statistical procedures were conducted using SPSS software (version 21), and results were considered statistically significant at a confidence level of 95% (p < 0.05). The following formula was used to calculate degradation removal (Equation (1)), where Cinitial is the initial concentration of TPHs and Cfinal is the final concentration of TPHs.

The pH was measured using a pH meter (Thermo 920A, manufacturer, Seville, Spain). The determination of total organic carbon (TOC) and total nitrogen (TN) was carried out using the high-temperature (720 °C) catalytic oxidative combustion method, with non-dispersive infrared detection and chemiluminescence detection, respectively, using the TNM-1 analyzer from Shimadzu (Duisburg, Germany). The analysis of total phosphorus (P), potassium (K) and sodium (Na) was performed by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES) using the 5100 ICP-OES analyzers from Agilent Technology.

2.2. Soil Sampling, Characterization and Spiking

Uncontaminated soil was collected at a depth of 10–40 cm in Andalusia (Spain): Aldea del Rocío soil (37°11′10.644″ N, 6°29′58.056″ O). The soil properties percentage of sand, slit, texture, organic matter (OM), pH, total organic carbon (TOC), total nitrogen (TN), carbonates, potassium (K), sodium (Na), phosphorous (P), phosphate (PO4), phosphorus pentoxide (P2O5), heterotrophic bacteria, heterotrophic fungi and gasoline/diesel degraders are shown in Table 1. The soil under study has a primarily sandy texture, with 90.1% sand, 9.2% silt, and 0.7% clay, indicating high permeability and low nutrient retention capacity. Its organic matter content is moderately low (1.2%), while its pH of 7.7 suggests slight alkalinity. TOC and TN levels are low (<0.5 g/kg and <0.1 g/kg, respectively). Regarding micronutrient composition, sodium is present at 16 mg/kg, while total phosphorus and its available forms (PO4 and P2O5) are quite low, with concentrations below 0.05 g/kg, 0.15 g/kg, and 0.12 g/kg, respectively.

Table 1.

Soil properties.

Microbiological analysis revealed a high population of heterotrophic bacteria (3.01 × 106 CFU/g), a lower abundance of fungi (5.04 × 103 CFU/g), and limited capacity for gasoline/diesel degradation (72 CFU/g), indicating an active microbial community with low bioremediation potential [41].

Uncontaminated soil samples were homogeneously mixed, air-dried, and passed through a 2 mm sieve. Subsequently, the soil was spiked with a gasoline-diesel mixture prepared at a volumetric ratio of 60:40. Using a precision micropipette, the mixture was applied until reaching a final concentration of 8530 mg hydrocarbons (C6–C35) per kilogram of soil. The contaminated soil was stored in closed bottles, protected from light, for two weeks to allow equilibration. After this period, the initial concentration of hydrocarbons in the soil was analyzed (Table 2).

Table 2.

Initial hydrocarbon concentration (mg hydrocarbon/kg soil).

2.3. Physicochemical Properties of Liquid By-Products Used for Biostimulation

Sludge dewatering sidestream (SD) was obtained at the South Urban Wastewater Treatment Plant of Seville, Spain. Leftover yeast (LY) was collected at the Heineken Brewery of Seville. Secondary clarifier effluent (SC) was obtained at the CEPSA Chemical Company Wastewater Treatment Plant of Huelva, Spain.

TOC, Nitrogen, Phosphorous, Potassium, Sodium, and Suspended Solids (SSs) in the liquid by-products used for the bioremediation trials are detailed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Physicochemical properties of liquid by-products used for bioremediation (mg/L).

2.4. Soil Microcosm Experiments

Bioremediation assays were conducted in 350 mL glass flasks sealed with perforated screw caps to allow ventilation. Each flask contained 200 g of contaminated soil, previously adjusted to 50% of its moisture holding capacity, to which 40 mL of industrial by-products were added (SD, LY ad SC). As a control, Milli-Q type II water was used instead of by-products. The flasks were stored in conditions of complete darkness at a constant temperature of 22 °C, and hydrocarbon concentrations were analyzed at 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 20 weeks. In order to prevent moisture loss due to evaporation, the flasks were weighed on a weekly basis. The evaporated volume was replenished with distilled water when necessary. All analyses were performed in triplicate.

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has emphasized the significance of maintaining sufficient moisture levels in the context of bioremediation experiments. It is essential to adjust the soil-to-liquid ratio in order to simulate realistic environmental conditions that promote microbial degradation without oversaturating the system [42]. Appropriate ratios are important for preserving soil aeration, ensuring even distribution of contaminants and microbial agents, and supporting effective biodegradation. In laboratory-scale studies, soil-to-liquid ratios provide a balanced environment for microbial activity, oxygen diffusion, and contaminant accessibility. In this study, the soil was previously adjusted to 50% of its moisture (water holding capacity (WHC), widely recognized for promoting microbial performance and contaminant bioavailability in bioremediation systems [43,44].

2.5. Catalase Activity Analysis

Catalase activity was determined by mixing 0.5 g of soil with 40 mL of distilled water and shaking for 30 min. The reaction was initiated with 5 mL of 0.3% H2O2 (ReagentPlus®, Sigma-Aldrich, Barcelona, Spain) and maintained under agitation for 10 min. To halt enzymatic activity, 5 mL of 1.5 M H2SO4 (ReagentPlus®, Sigma-Aldrich, Barcelona, Spain) was added. The mixture was filtered, and a 25 mL portion was analyzed using 0.01 M KMnO4 (ReagentPlus®, Sigma-Aldrich, Barlcelona, Spain). Absorbance was measured at 485 nm with a spectrophotometer.

Control assays were conducted following the same procedure as the samples, except that the 5 mL of H2O2 was substituted with distilled water. A blank solution was prepared consisting of 40 mL of distilled water, 5 mL of H2O2, and 5 mL of 1.5 M H2SO4. From this blank, a 25 mL aliquot was taken and evaluated with KMnO4 [45]. Tests were performed in triplicate to ensure accuracy and reproducibility of the measurements. The catalase enzyme activity was expressed in specific activity (mmol H2O2 h−1 g−1 dry soil). Catalase activity in soil was calculated using the following equation [46]:

where:

- = catalase activity, expressed as mmoles of H2O2 consumed per gram of dry soil per hour.

- = volume of KMnO4 (mL) used in the titration of the blank.

- = volume of KMnO4 (mL) used in the titration of the sample.

- = volume of KMnO4 (mL) used in the titration of the control corresponding to each soil sample.

- = exact normality of the KMnO4 solution.

- = dilution factor.

- = dry soil mass factor, determined by drying 0.5 g of moist soil and recording the corresponding dry weight.

- = time factor (6), corresponding to 10 min of reaction, reported as per hour (60/10 = 6).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Biodegradation of Petroleum Hydrocarbons

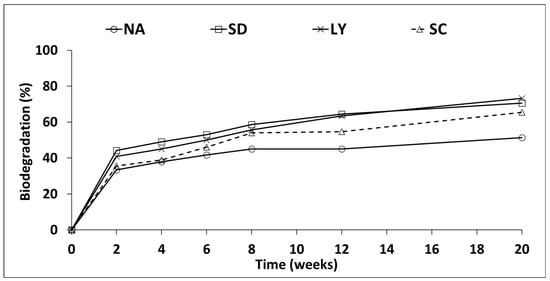

TPH concentration was determined throughout the course of microcosm tests (2, 4, 6, 8, 12 and 20 weeks). Figure 1 show the percentages of soil TPH elimination produced by different industrial by-products (NA (natural attenuation or control), SD, LY and SC).

Figure 1.

Rates of TPH biodegradation for SD, LY and SC.

The total reduction in TPHs in the natural attenuation treatment was 51.3% after 20 weeks of incubation. Natural mechanisms of biodegradation, volatilization, and mineralization were able to eliminate a considerable portion of the hydrocarbons present in the initial contaminated samples. Similar results have been reported by Agamuthu et al. [32], Chaîneau et al. [47], Margesin and Schinner [48], and Nwankwegu et al. [49], who achieved between 47% and 56% removal of organic contaminants through natural attenuation.

Nevertheless, the results showed high biodegradation at the end of 20 weeks with soil treated with industrial by-products compared to natural attenuation. The use of industrial by-products as biostimulants to contaminated soil increased hydrocarbon degradation. Nevertheless, these degradations depend on the biostimulant applied to the soil. At the end of experiments, the hydrocarbon polluted soil amended with LY showed the highest elimination ratio with 73.2%, followed by soil treated with sludge dewatering sidestream and secondary clarifier effluent of chemical company wastewater treatment plant which are 70.6% and 65.4%, respectively (Figure 1). The use of industrial by-products for amending gasoline and diesel fuel contaminated soil has greater TPH biodegradation compared to control soil in this study. The main dissimilarity of TPH biodegradation between natural attenuation and soil treated with industrial waste occurred during the last 12 weeks (8–20 weeks), then biostimulation caused a marked rise in TPH biodegradation. The indigenous microorganisms of soil were stimulated by the addition of nutrients, for this reason the microorganisms reduce the hydrocarbons concentrations in soil faster than in a natural attenuation experiment. Similar results have been reported when organic waste was used as an amendment. Molina et al. [35] found that soils treated with stabilized poultry litter and yeast effluent showed 73.6% hydrocarbon degradation after 90 days. In our study, the LY treatment achieved 73.2% removal after 20 weeks. This comparison emphasizes the efficiency of LY, establishing it as a competitive option in comparison to natural waste supplements in the cleaning up of hydrocarbons. Mayans et al. [50] show that the control degraded only 19–20% of TPHs. In contrast, the treatments with mushroom substrates achieved up to 67% degradation at best, with minimal differences between layers (2–4%), and an additional improvement of 9–16% in other treatments. This value is slightly below those reported for LY.

The superior performance observed with brewer’s yeast may be attributed to differences in the nutrient composition of the industrial residues employed. As shown in Table 3, LY effluent contains the highest concentrations of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. Soils amended with LY exhibited enhanced TPH degradation, likely because this by-product provides an adequate supply of essential nutrients (TN, P, and K) that favor effective biostimulation.

In addition to the TPH analysis, the distribution of hydrocarbon fractions was also examined (Table 4). GC results revealed that degradation increased progressively with bioremediation time. This trend was particularly evident in the fractions C10–C12 and C12–C16. For the C10–C12 fraction, degradation increased from 36–53% at week 2 to 76–97% at week 20, while for the C12–C16 fraction, it rose from 8–18% to 52–74% over the same period.

Table 4.

Elimination rates of hydrocarbon fractions (mg hydrocarbon kg soil−1).

Table 4 also shows that as hydrocarbon chain length increases; the biodegradation of the pollutants decreases. The smallest hydrocarbons (C6–C8) were nearly eliminated after 20 weeks, whereas the heavier hydrocarbons (C21–C35) were more recalcitrant, achieving removal rates of only 13–35%. This trend of decreasing biodegradation with increasing hydrocarbon size was consistent across all three tested biostimulant by-products. These results may be explained by the greater bioavailability, higher aqueous solubility, lower recalcitrance, and higher volatility of shorter-chain hydrocarbons compared to larger ones.

Additionally, an increase in the biodegradation of the heaviest pollutants was observed during the final 8 weeks of the experiment. This suggests that by this stage, the smaller hydrocarbons had largely been depleted (70–90% removal by week 12), directing microbial activity toward the remaining larger hydrocarbons. Similar observations have been reported by Chaîneau et al. [47], Jiang et al. [51], and Nikolopoulou et al. [52], who found that biodegradation preferentially removed lighter petroleum hydrocarbons. Specifically, Okoye et al. [53] reported that composting enhanced the degradation rates of petroleum hydrocarbons, achieving 67.88% removal for the C ≤ 16 fraction and 61.87% for the C > 16 fraction. Cai et al. [54], in their study on biostimulation through composting, reported results slightly lower than those obtained in this study. Specifically, they found that composting increased the rate at which petroleum hydrocarbons degraded, achieving a removal rate of 67.88% removal for the C ≤ 16 fraction and 61.87% for the C > 16 fraction. Some authors reported that larger organic compounds, such as PAHs, are more recalcitrant due to their low bioavailability, hydrophobicity, and greater thermodynamic stability [55,56].

Hydrocarbons with fewer carbon atoms did not exhibit a preferential biodegradation between aliphatic and aromatic types, as both were almost completely degraded after 20 weeks. However, for larger contaminants, Table 4 shows notable differences, for instance, aliphatic hydrocarbons C21–C35 were removed at a maximum of 35.2% after 20 weeks, whereas aromatic hydrocarbons C21–C35 reached only 18.8%. GC analysis indicated that aliphatic hydrocarbons in the C6–C16 range were degraded more extensively than their aromatic counterparts, while compounds with more than 16 carbons also underwent greater biodegradation when aliphatic. This may be attributed to the fact that aromatic hydrocarbons are more volatile compared to aliphatic counterparts; however, as the molecular size increases, aromatic structures confer greater recalcitrance to biodegradation compared to similarly sized aliphatic compounds [57]. Overall, Jiang et al. [51] similarly reported that aromatic hydrocarbons were less biodegraded than aliphatic ones.

It is important to discuss that the observed decrease in the hydrocarbon soil content may not only be due to the biodegradation process, facilitated by the industrial by-products added to the contaminated soil. Furthermore, can be due to other physicochemical processes such as evaporation, photooxidation or dissolution of hydrocarbons. Margesin and Schinner [48] had estimated that at least 10% of the fossil fuel were eliminated through abiotic pathways in 30 days.

As shown in Figure 1, the efficiency in hydrocarbon reduction from week 8 onward was not higher than that in weeks 12 and 20. The removal medium values were 58.7%, 64.4%, and 70.6% for SD; 55.6%, 63.4%, and 73.2% for LY; and 53.6%, 54.7%, and 65.4% for SC, respectively. This may suggest that it is not necessary to wait beyond week 8, as there is no substantial difference between week 8 and week 12, or even week 20. However, if we take into account the data from Table 4 and the removal of contaminants with longer or more resistant hydrocarbon chains, it could indicate that waiting longer is beneficial to achieve better elimination of these compounds.

3.2. Biodegradation Kinetic Modeling

First- and second-order kinetic models were employed to evaluate the degradation rate of TPHs in the studied microcosms. The kinetics of hydrocarbon degradation have been extensively investigated in previous studies [32,49,58,59], and this experimental study was expected to conform to either kinetic order. The equations applied for the first (Equations (3) and (4)) and second (Equations (5) and (6)) order kinetic models were as follows:

where Ct is the concentration of hydrocarbons in soil at time t (mg/kg of dry soil), C0 is the initial concentration of hydrocarbons in soil (mg/kg of dry soil), k is the first-order biodegradation kinetic constant (day−1), k2 is the second-order biodegradation kinetic constant (kg mg−1 day−1), t1/2 is half live time (day) and t is the time (day).

Ct = C0 × e−k·t

T1/2 = ln (2)/k

k2 × t = Ct/C0 × (C0 − Ct)

t1/2 = 1/k2 × C0

The half-life time (t1/2) is defined as the time necessary for half of the hydrocarbons in the soil to be eliminated. The kinetic models and half-lives of the microcosm experiments are shown in Table 5 and Table 6.

Table 5.

Parameters of the first-order biodegradation kinetic model.

Table 6.

Parameters of the second-order biodegradation kinetic model.

Considering the first-order kinetic model, the biosimulation with LY (k1 = 8.1 × 10−3 d−1; half-life = 86 d) was 20% faster than the natural attenuation (k1 = 6.1 × 10−3 d−1; half-life = 114 d). The first-order kinetic model also shows that natural attenuation has a lower biodegradation rate than any of the three biostimulants used. On the other hand, using the second order biodegradation kinetic model, it is observed that the samples treated with sludge dewatering sidestream and secondary clarifier effluent biodegraded 16% (k2 = 1.8 × 10−6 kg mg−1 d−1; half-life = 65 d) and 48% (k2 = 1.4 × 10−6 kg mg−1 d−1; half-life = 83 d), respectively, slower than those treated with leftover yeast (k2 =2.1 × 10−6 kg mg−1 d−1; half-life = 56 d), but both of them biodegraded faster than natural attenuation (k2 =1.3 × 10−6 kg mg−1 d−1; half-life = 91 d) since this sample indicates a 63% slower biodegradation with respect to the sample biostimulated with leftover yeast. Taking into account that the value of R2 closer to 1 shows a higher correlation, the correlation coefficient of the second-order model was higher than the first order. This may be due to limitations in the substrate and its interaction with the growth of the microbial population [60]. In addition, the half-life times of the second order model are better fitted to the results observed in this investigation. It seems that the second order kinetic model better describes the biodegradation of petroleum hydrocarbons. Similar results were observed by Nwankwegu et al. [49]. Also, the second order kinetic model shows shorter half-lives of TPHs.

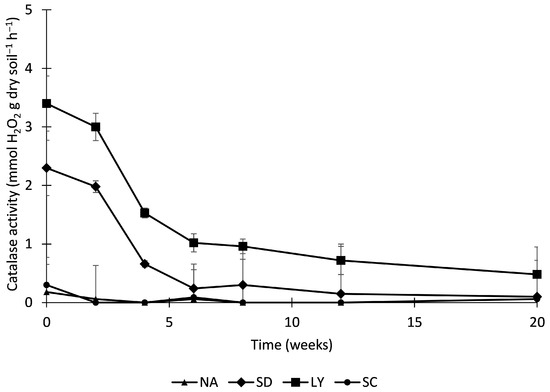

3.3. Changes in Catalase Activities

The enzyme activity of the soil is influenced by the characteristics of the soil, the pollutants and the industrial effluent applied [61,62]. The monitoring of the enzymatic activity of the soil provides valuable information about the health of the soil. Furthermore, the analysis of catalase activity contributes data about the changes in soil properties. As stated in the study by Wu et al. [63], the study of catalase in soil provides relevant information related to the state of contaminant bioremediation, indicates the degree of microbiological activity, and serves as an indicator of possible variations in soil properties. Reduced enzymatic activity indicates limited or no contribution of microorganisms to the biodegradation process. In contrast, significant activity values indicate that the living organisms present in the soil are biodegrading hydrocarbons [64].

Figure 2 shows the evolution of catalase activity with respect to time, it is observed that in the natural attenuation and SC samples the catalase activity was low, while in the other 2 samples, notable activity occurred. The two samples in which there was a greater catalase activity with those that present greater hydrocarbon elimination data (LY and SC). Significant values of enzyme activity may indicate that the microorganisms present in the soil are biodegrading hydrocarbons [48,64].

Figure 2.

Effects of biostimulation on catalase activity in petroleum hydrocarbon contaminated soil. Values are means ± standard deviation (n = 3).

Initially, LY and SD exhibited the highest enzymatic activity, suggesting a stronger immediate response to the applied biostimulants. At week 4, LY maintained elevated activity while SD began to decline, indicating early differences in enzymatic persistence. NA and SC remained at lower levels, with SC showing minimal variation. By week 12, LY continued to outperform the other treatments, whereas SD, NA, and SC showed further reductions, highlighting a progressive loss of enzymatic potential. These trends suggest that the biostimulant associated with LY may have contributed to greater enzymatic resilience. By week 20, all treatments converged toward reduced activity levels, although LY remained slightly higher.

In the samples of contaminated soil to which the SD and LY effluents were added, it is observed that the activity was high in the first weeks and then decreased until it stabilized; this may have been due to these samples containing numerous microorganisms and only some of them were able to adapt to the conditions of the soil contaminated by hydrocarbons. Highly contaminated soil shows high toxicity to most soil microorganisms [65,66]. Specifically, some authors have shown that petroleum hydrocarbon contamination affects microbial diversity and the structure of microbial co-occurrence networks, suggesting a relationship between soil microbial characteristics and its ecological functionality [67].

4. Conclusions

Soil contamination by petroleum hydrocarbons is a significant environmental challenge, especially in industrial and urban areas. This study demonstrates that the use of industrial liquid by-products, sludge dewatering (SD) side stream, residual yeast (LY), and secondary clarifier (SC) effluent, as biostimulants improves the biodegradation of gasoline and diesel mixtures in contaminated soils.

Microcosm tests conducted over 20 weeks revealed that all by-products promoted greater TPH removal compared to natural attenuation. LY was the most effective, achieving 73.2% TPH removal, followed by SD (70.6%) and SC (65.4%). Degradation was more pronounced in short-chain hydrocarbons (C6–C16), while higher molecular weight compounds (C21–C35) showed greater resistance. Likewise, aliphatic hydrocarbons showed superior degradability to aromatics in the heavy fractions. Moreover, the increase in catalase enzyme activity in soils treated with LY and SD suggests greater microbial activity, reinforcing the potential of these by-products as effective tools for the bioremediation of hydrocarbon-contaminated soils.

Although the use of industrial by-products in soil remediation may offer sustainability benefits, such as resource recovery and waste minimization, potential environmental risks must also be considered. The presence of heavy metals, toxic residues, or other contaminants has the potential to compromise soil quality, affect microbial communities, and poses risks to groundwater and ecosystems. However, when managed effectively, the reuse of industrial by-products can support circular economy strategies and enhance hydrocarbon removal efficiency by stimulating microbial activity. Therefore, a balanced assessment is required to ensure that the sustainability gains and improved hydrocarbon degradation are not offset by unintended contamination issues.

In terms of future perspectives, it would be valuable to expand the scope of the study by evaluating other contaminants beyond TPHs, such as heavy metals, to assess the broader applicability of the remediation strategy. Furthermore, a comparison of the current approach with other bioremediation techniques, such as bioaugmentation or phytoremediation, could assist in determining whether higher yields or synergistic effects can be achieved. In addition, microbial characterization, including community shifts and dominant taxa, could be used to better elucidate biodegradation mechanisms. Finally, scaling the experiment to field conditions would allow for validation of its effectiveness in real-world scenarios and provide insight into its technical and economic feasibility.

Author Contributions

E.R.: Sample collection, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft. C.A.: Conceptualization, sample collection, methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft and writing—review and editing. J.M.: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing—review and editing. A.E.-C.: Visualization, writing—original draft and writing—review and editing. J.U.: Conceptualization, methodology, validation, resources, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by INERCO Inspección y Control S. A. (PI 1790/43/2018) and by the VII PPIT-US and partially funded by IBERDROLA, S. A.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in IdUS Institutional Repository (Universidad de Sevilla) at https://idus.us.es/items/18227579-9f27-4985-91bb-777803effe7d (accessed on 15 October 2025).

Acknowledgments

The project was the incentive of the Corporación Tecnológica de Andalucía (CTA).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Nomenclature

| BTEX | Benzene, Toluene, Ethylbenzene and Xylenes |

| CFU | Colony-Forming Unit |

| GC/MS | Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry |

| GC/FID | Gas chromatography equipped with a flame ionization detector |

| LY | Sample leftover yeast |

| NA | Natural attenuation |

| OM | Organic Matter |

| PAHs | Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons |

| SC | Sample secondary clarifier effluent |

| SD | Sample dewatering sidestream |

| SSs | Suspended Solids |

| TOC | Total Organic Carbon |

| TN | Total Nitrogen |

| TPHs | Total petroleum hydrocarbons |

| USEPA | United States Environmental Protection Agency |

References

- Ehis-Eriakha, C.B.; Ajuzieogu, C.A.; Orogu, J.O.; Akemu, S.E. Overview of petroleum hydrocarbon pollution and bioremediation technologies. Bioremediat. J. 2024, 29, 238–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xing, E.; Han, W.; Yang, P.; Zhang, S.; Liu, S.; Cao, D.; Li, M. Petrochemical Industry for the Future. Engineering 2024, 43, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falih, K.T.; Mohd Razali, S.F.; Abdul Maulud, K.N.; Abd Rahman, N.; Abba, S.I.; Yaseen, Z.M. Assessment of petroleum contamination in soil, water, and atmosphere: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 21, 8803–8832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, H.; Hou, J.; Du, M.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, W.; Christie, P.; Luo, Y. Surfactant-enhanced bioremediation of petroleum-contaminated soil and microbial community response: A field study. Chemosphere 2023, 322, 138225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanta, S.; Pradhan, B.; Behera, I.D. Impact and Remediation of Petroleum Hydrocarbon Pollutants on Agricultural Land: A Review. Geomicrobiol. J. 2023, 41, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorrami, M.K.; Sadrara, M.; Mohammadi, M. Quality classification of gasoline samples based on their aliphatic to aromatic ratio and analysis of PONA content using genetic algorithm based multivariate techniques and ATR-FTIR spectroscopy. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2022, 126, 104354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agency for Toxic Substances Disease Registry (ATSDR). Toxicological Profile for Total Petroleum Hydrocarbons; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1999.

- Hilakivi-Clarke, L.; Jolejole, T.K.; da Silva, J.L.; Andrade, F.O.; Dennison, G.; Mueller, S. Aromatics from fossil fuels and breast cancer. iScience 2025, 28, 112204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagos, P.; Van Liedekerke, M.; Yigini, Y.; Montanarella, L. Contaminated Sites in Europe: Review of the Current Situation Based on Data Collected through a European Network. J. Environ. Public Health 2013, 2013, 158764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency USEPA. Introduction to In Situ Bioremediation of Groundwater; Office of Solid Waste Emergency Response: Washington, DC, USA, 2013.

- De, S.; Biswas, S.; Satahrada, S.; Pal, N.; Panda, S.K.; Pattnaik, R. Microbial Remediation of Petroleum Hydrocarbon Polluted Soils: Challenges and Perspectives. In Environmental Friendly Green Technologies for Improvement of Heavy Crude Oil Flow Assurance. Environmental Science and Engineering; Banerjee, S., Chakrabortty, S., Nayak, J., Tripahy, S.K., Shah, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael-Igolima, U.; Abbey, S.J.; Ifelebuegu, A.O. A systematic review on the effectiveness of remediation methods for oil contaminated soils. Environ. Adv. 2022, 9, 100319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.; Oginga, B.; Zhang, Y.; Ling, W.; Tang, L.; Elatafi, E.; Abady, M.; Gao, Y. Bioremediation of soils with emerging organic contaminants using immobilized microorganisms. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2025, 40, 104345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, D.; Sen, S. In-Depth Coverage of Petroleum Waste Sources, Characteristics, Environmental Impact, and Sustainable Remediation Process. In Impact of Petroleum Waste on Environmental Pollution and Its Sustainable Management Through Circular Economy. Environmental Science and Engineering; Behera, I.D., Das, A.P., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micle, V.; Sur, I.M. Experimental investigation of a pilot-scale concerning ex-situ bioremediation of petroleum hydrocarbons contaminated soils. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micle, V.; Sur, I.M.; Criste, A.; Senila, M.; Levei, E.; Marinescu, M.; Cristorean, C.; Rogozan, G.C. Lab-scale experimental investigation concerning ex-situ bioremediation of petroleum hydrocarbons-contaminated soils. Soil Sediment. Contam. Int. J. 2018, 27, 692–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Vazquez, A.; Barciela, P.; Prieto, M.A. In Situ and Ex Situ Bioremediation of Different Persistent Soil Pollutants as Agroecology Tool. Processes 2024, 12, 2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Bernard, I.; Sanz-García, J.; Dorado-Valiño, M.; Villar-Fernández, S. Técnicas de Recuperación de Suelo Contaminados. 2007. Available online: https://www.madrimasd.org/sites/default/files/informacionidi/biblioteca/publicacion/doc/VT/vt6_tecnicas_recuperacion_suelos_contaminados.pdf (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Romantschuk, M.; Lahti-Leikas, K.; Kontro, M.; Galitskaya, P.; Talvenmäki, H.; Simpanen, S.; Allen, J.A.; Sinkkonen, A. Bioremediation of contaminated soil and groundwater by in situ biostimulation. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1258148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oro, C.E.D.; Saorin Puton, B.M.; Venquiaruto, L.D.; Dallago, R.M.; Tres, M.V. Effective Microbial Strategies to Remediate Contaminated Agricultural Soils and Conserve Functions. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suja, F.; Rahim, F.; Taha, M.R.; Hambali, N.; Rizal Razali, M.; Khalid, A.; Hamzah, A. Effects of local microbial bioaugmentation and biostimulation on the bioremediation of total petroleum hydrocarbons (TPH) in crude oil contaminated soil based on laboratory and field observations. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2014, 90, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlas, R.M.; Bartha, R. Degradation and mineralization of petroleum in sea water: Limitation by nitrogen and phosphorous. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1972, 14, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragg, J.R.; Prince, R.C.; Harner, J.E.; Atlas, R.M. Effectiveness of bioremediation for the Exxon Valdez oil spill. Nature 1994, 368, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Quader, A.K.M. Natural gas and the fertilizer industry. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2003, 7, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordell, D.; Neset, T.-S.S.; Prior, T. The phosphorus paradox: Scarcity and wastefulness in industrial agriculture. Sustain. Sci. 2023, 18, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abay, K.A.; Chamberlin, J.; Chivenge, P.; Spielman, D.J. Fertilizer, soil health, and economic shocks: A synthesis of recent evidence. Food Policy 2025, 133, 102892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curiel-Alegre, S.; Velasco-Arroyo, B.; Rumbo, C.; Khan, A.H.A.; Tamayo-Ramos, J.A.; Rad, C.; Gallego, J.L.R.; Barros, R. Evaluation of biostimulation, bioaugmentation, and organic amendments application on the bioremediation of recalcitrant hydrocarbons of soil. Chemosphere 2022, 307, 135638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernysh, Y.; Chubur, V.; Ablieieva, I.; Skvortsova, P.; Yakhnenko, O.; Skydanenko, M.; Plyatsuk, L.; Roubík, H. Soil Contamination by Heavy Metals and Radionuclides and Related Bioremediation Techniques: A Review. Soil Syst. 2024, 8, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Report from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2017.

- Srivastava, N.; Maurya, V.K.; Bee, Z.; Singh, N.; Khare, S.; Singh, S.; Agarwal, N.; Rai, P.K. Chapter 21—Green Solutions for a blue planet: Harnessing bioremediation for sustainable development and circular economies. In Biotechnologies for Wastewater Treatment and Resource Recovery; Srivastav, A.L., Zinicovscaia, I., Cepoi, L., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Sun, Y.; Tian, F.; Xu, C.; Miao, Y.; Jiang, W. Synthesis and performance characteristics of organic-inorganic hybrid fire prevention and extinguishing gel based on phytoextraction-medical stone. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 312, 125310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agamuthu, P.; Tan, Y.S.; Fauziah, S.H. Bioremediation of hydrocarbon contaminated soil using selected organic wastes. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2013, 18, 694–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejada, M.; Masciandaro, G. Application of organic wastes on a benzo(a)pyrene polluted soil. Response of soil biochemical properties and role of Eisenia fetida. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2011, 74, 668–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, C.C.; Netto, L.G.; Barbosa, A.M.; Thomaz, O. Improved Bioremediation of Diesel-Contaminated Soils Using Stabilized Poultry Manure. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2024, 235, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, D.C.; Di Gregorio, V.; Busnardo, G.; Liporace, F.; Quevedo, C.V. Organic Waste Mixtures for Improving Hydrocarbon Bioremediation in Chronically Polluted Soil. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2025, 19, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuppan, N.; Padman, M.; Mahadeva, M.; Srinivasan, S.; Devarajan, R. A comprehensive review of sustainable bioremediation techniques: Eco friendly solutions for waste and pollution management. Waste Manag. Bull. 2024, 2, 154–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency USEPA. 8260b Method 1–86; USEPA: Washington, DC, USA, 1996.

- United States Environmental Protection Agency USEPA. Method 5021a 1–31; USEPA: Washington, DC, USA, 1994.

- United States Environmental Protection Agency USEPA. Bioremediation of Hazardous Waste Sites: Practical Approaches to Implementation EPA/625/K-96/001; USEPA: Washington, DC, USA, 1996.

- United States Environmental Protection Agency USEPA. Method 3540C 1–8; USEPA: Washington, DC, USA, 1996.

- Bekele, G.K.; Gebrie, S.A.; Mekonen, E.; Fida, T.T.; Woldesemayat, A.A.; Abda, E.M.; Tafesse, M.; Assefa, F. Isolation and Characterization of Diesel-Degrading Bacteria from Hydrocarbon-Contaminated Sites, Flower Farms, and Soda Lakes. Int. J. Microbiol. 2022, 2022, 5655767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Environmental Protection Agency USEPA. Green Remediation Best Management Practices: Bioremediation (EPA 542-F-21-028); USEPA: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2022-04/gr_factsheet_bioremediation.pdf (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- García-Gómez, C.; Uysal, Y.; Doğaroğlu, Z.G.; Kalderis, D.; Gasparatos, D.; Fernández, M.D. Influence of Biochar-Reinforced Hydrogel Composites on Growth and Biochemical Parameters of Bean Plants and Soil Microbial Activities under Different Moisture Conditions. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Feng, S.; Liu, Z.; Tang, S. Bioremediation of petroleum-contaminated soil based on both toxicity risk control and hydrocarbon removal—Progress and prospect. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 59795–59818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas-Díaz, M.C.; Martínez-Toledo, Á.; Guzmán-López, O.; Torres-López, C.P.; Ortega-Martínez, A.C.; Hermida-Mendoza, L.J. Catalase and Phosphatase Activities During Hydrocarbon Removal from Oil-Contaminated Soil Amended with Agro-Industrial by-products and Macronutrients. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2017, 228, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montejo Martínez, M.; Torres López, C.P.; Martínez, Á.; Tenorio, J.; Cruz, M.; Ramos, F.; Cuevas, M. Técnicas para el análisis de actividad enzimática en suelos. In Métodos Ecotoxicológicos Para la Evaluación de Suelos Contaminados con Hidrocarburos; Diaz, M.D.C.C., Reyes, G.E., Cantu, C.A.I.H.y.A.M., Eds.; SEMARNAT, INE, Universidad Veracruzana: Veracruz, Mexico, 2012; pp. 19–46. [Google Scholar]

- Chaîneau, C.H.; Rougeux, G.; Yéprémian, C.; Oudot, J. Effects of nutrient concentration on the biodegradation of crude oil and associated microbial populations in the soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2005, 37, 1490–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margesin, R.; Schinner, F. Bioremediation (Natural Attenuation and Biostimulation) of Diesel-Oil-Contaminated Soil in an Alpine Glacier Skiing Area. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 67, 3127–3133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nwankwegu, A.S.; Orji, M.U.; Onwosi, C.O. Studies on organic and in-organic biostimulants in bioremediation of diesel-contaminated arable soil. Chemosphere 2016, 162, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayans, B.; Antón-Herrero, R.; García-Delgado, C.; Delgado-Moreno, L.; Guirado, M.; Pérez-Esteban, J.; Escolástico, C.; Eymar, E. Bioremediation of petroleum hydrocarbons polluted soil by spent mushroom substrates: Microbiological structure and functionality. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 473, 134650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Brassington, K.J.; Prpich, G.; Paton, G.I.; Semple, K.T.; Pollard, S.J.T.; Coulon, F. Insights into the biodegradation of weathered hydrocarbons in contaminated soils by bioaugmentation and nutrient stimulation. Chemosphere 2016, 161, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolopoulou, M.; Pasadakis, N.; Kalogerakis, N. Evaluation of autochthonous bioaugmentation and biostimulation during microcosm-simulated oil spills. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2013, 72, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoye, A.U.; Selvarajan, R.; Chikere, C.B.; Okpokwasili, C.C.; Mearns, K. Characterization and identification of long-chain hydrocarbon-degrading bacterial communities in long-term chronically polluted soil in Ogoniland: An integrated approach using culture-dependent and independent methods. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 30867–30885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, C.; Dang, Q.; Xi, B. Regulating the biodegradation of petroleum hydrocarbons with different carbon chain structures by composting systems. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 903, 166552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daugulis, A.; McCracken, C. Microbial degradation of high and low molecular weight polyaromatic hydrocarbons in a two-phase partitioning bioreactor by two strains of Sphingomonas sp. Biotechnol. Lett. 2005, 25, 1441–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, A.B.; Shaikh, S.; Jain, K.R.; Desai, C.; Madamwar, D. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons: Sources, Toxicity, and Remediation Approaches. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 562813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nzila, A. Current Status of the Degradation of Aliphatic and Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Environment. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 15, 2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Li, Q.; Wang, N.; Liu, D.; Zan, L.; Chang, L.; Gou, X.; Wang, P. Bioremediation of petroleum-contaminated soil using aged refuse from landfills. Waste Manag. 2018, 77, 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, D.; Ferguson, M.; Datta, R.; Birnbaum, S. Bioremediation of petroleum hydrocarbons in contaminated soils: Comparison of biosolids addition, carbon supplementation, and monitored natural attenuation. Environ. Pollut. 2005, 136, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharasoo, M.; Centler, F.; Van Cappellen, P.; Wick, L.Y.; Thullner, M. Kinetics of substrate biodegradation under the cumulative effects of bioavailability and self-inhibition. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 5529–5537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dindar, E.; Topaç Şağban, F.O.; Başkaya, H.S. Variations of soil enzyme activities in petroleum-hydrocarbon contaminated soil. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2015, 105, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asensio, D.; Zuccarini, P.; Sardans, J.; Marañón-Jiménez, S.; Mattana, S.; Ogaya, R.; Mu, Z.; Llusià, J.; Peñuelas, J. Soil biomass-related enzyme activity indicates minimal functional changes after 16 years of persistent drought treatment in a Mediterranean holm oak forest. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2024, 189, 109281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Dick, W.A.; Li, W.; Wang, X.; Yang, Q.; Wang, T.; Xu, L.; Zhang, M.; Chen, L. Bioaugmentation and biostimulation of hydrocarbon degradation and the microbial community in a petroleum-contaminated soil. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2016, 107, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Li, X.; Sun, T.; Li, P.; Zhou, Q.; Sun, L.; Hu, X. Changes in microbial populations and enzyme activities during the bioremediation of oil-contaminated soil. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2009, 83, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tara, N.; Afzal, M.; Ansari, T.M.; Tahseen, R.; Iqbal, S.; Khan, Q.M. Combined use of alkane-degrading plant growth-promoting bacteria enhanced phytoremediation of diesel contaminated soil. Int. J. Phytoremediation 2014, 16, 1268–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, W.; Cheng, L.; Tan, Q.; Liu, Y.; Dou, J.; Yang, K.; Yang, Q.; Wang, S.; Li, J.; Niu, G.; et al. Response of the soil microbial community to petroleum hydrocarbon stress shows a threshold effect: Research on aged realistic contaminated fields. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1188229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, H.; Wu, M.; Liu, H.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Z. Effect of petroleum hydrocarbon pollution levels on the soil microecosystem and ecological function. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 293, 118511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).