An Adult Arrhythmia in a Child’s Heart: A Case Report of Unexplained Atrial Fibrillation

Abstract

1. Introduction and Clinical Significance

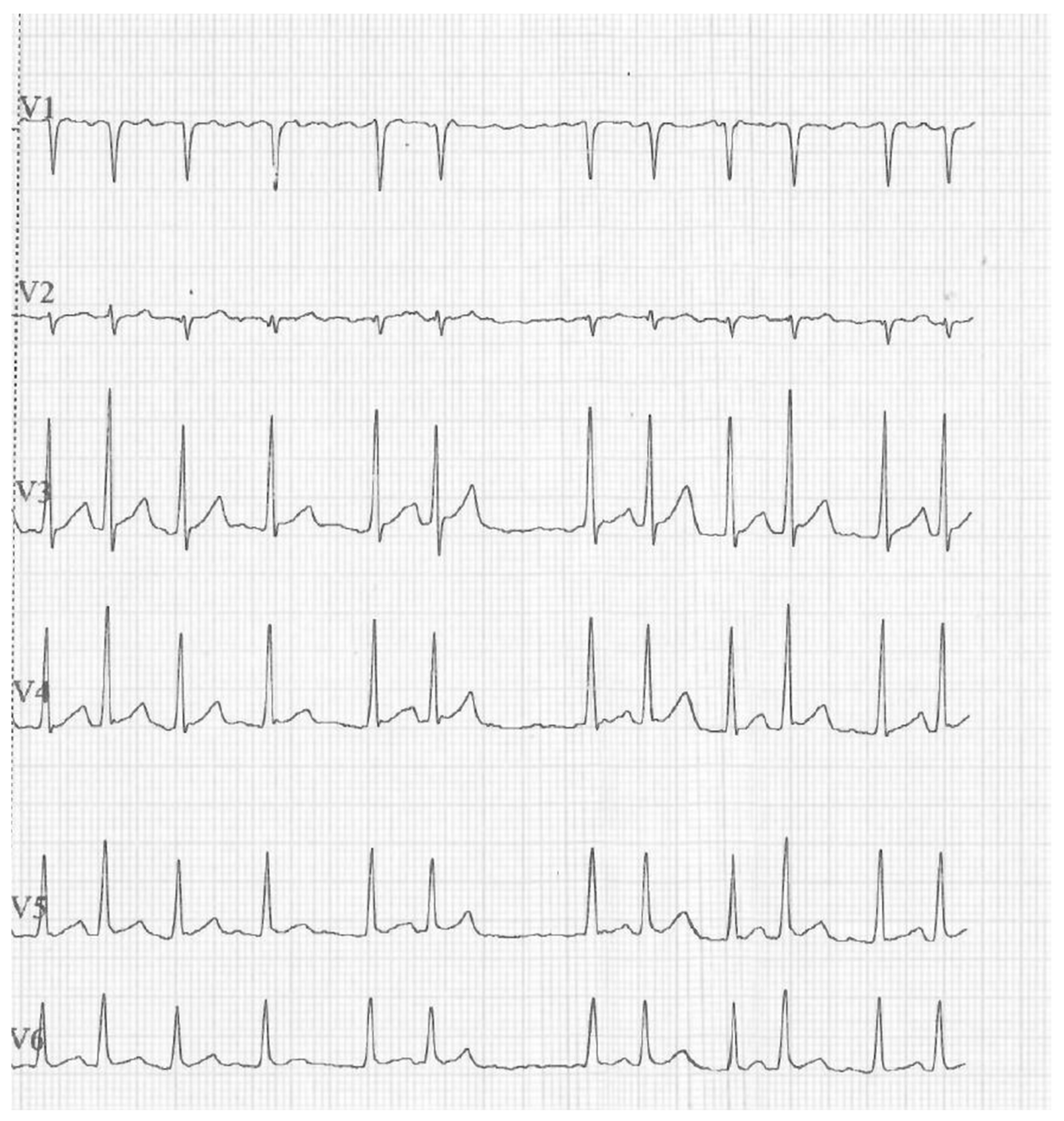

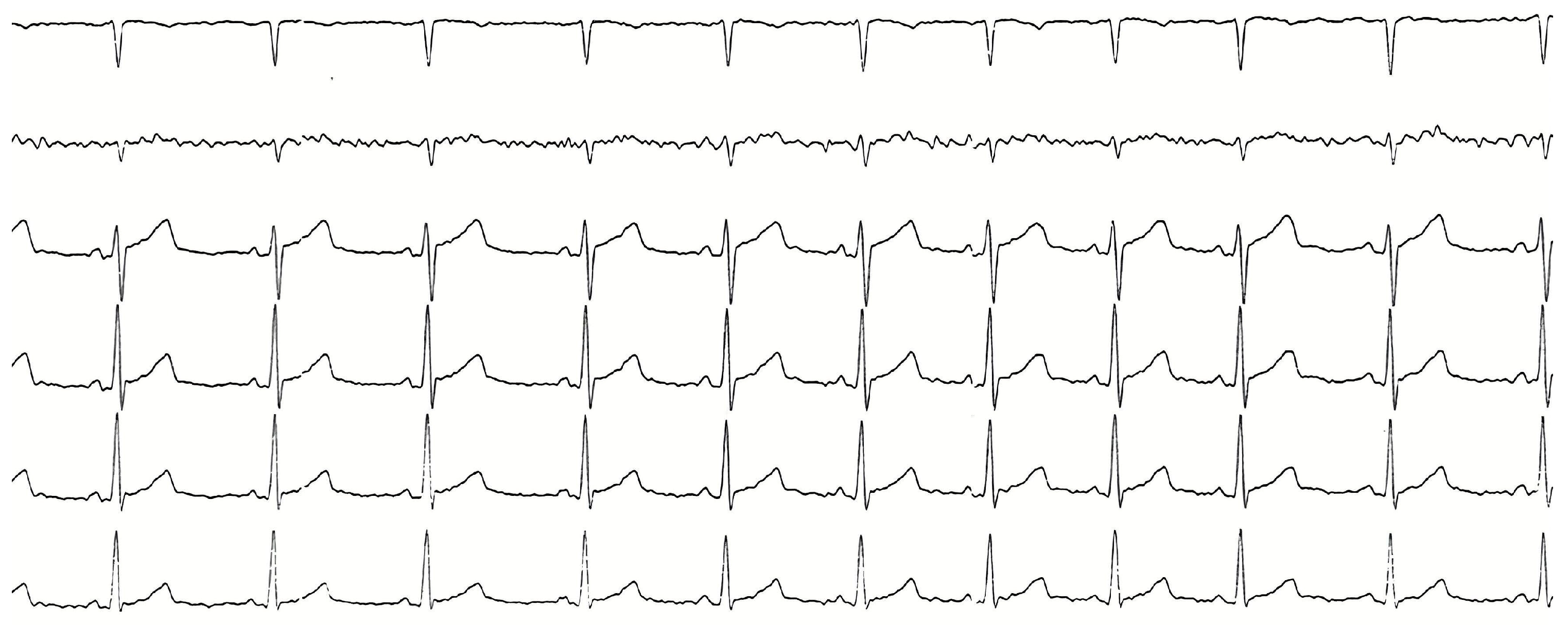

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion

3.1. Epidemiology and Clinical Context of AF in Children

3.2. Role of Epicardial Fat and Inflammation in AF Development

- (1)

- (2)

- Adipokines secreted by epicardial fat within the pericardial sac could promote paracrine effects on myocardium and consequently fibrosis [18];

- (3)

- Epicardial fat secretes markers of inflammation that result in local pro-inflammatory effects on the adjacent myocardium with increased risk of arrhythmia [19].

3.3. Electrical and Structural Remodeling Mechanisms in Obesity-Related AF

3.4. Oxidative Stress, Endothelial Dysfunction, and Clinical Implications

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AF | Atrial Fibrillation |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| COSI | Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| CRP | C Reactive Protein |

| IL | Interleukin |

| TNF | Tumor Necrosis Factor |

| HSP | Heat-Shock Protein |

| HIF | Hypoxia-inducible Factor |

| TGF | Transforming Growth Factor |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| TAC | Total Antioxidant Capacity |

References

- Go, A.S.; Hylek, E.M.; Phillips, K.A.; Chang, Y.; Henault, L.E.; Selby, J.V.; Singer, D.E. Prevalence of Diagnosed Atrial Fibrillation in Adults: National Implications for Rhythm Management and Stroke Prevention: The Anticoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. JAMA 2001, 285, 2370–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obrycki, Ł.; Skoczyński, K.; Sikorski, M.; Koziej, J.; Mitoraj, K.; Pilip, J.; Pac, M.; Feber, J.; Litwin, M. Current Etiology of Hypertension in European Children-Factors Associated with Primary Hypertension. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2025, 40, 3233–3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Assaad, I.; Hammond, B.H.; Kost, L.D.; Worley, S.; Janson, C.M.; Sherwin, E.D.; Stephenson, E.A.; Johnsrude, C.L.; Niu, M.; Shetty, I.; et al. Management and Outcomes of Atrial Fibrillation in 241 Healthy Children and Young Adults: Revisiting “Lone” Atrial Fibrillation—A Multi-Institutional PACES Collaborative Study. Heart Rhythm 2021, 18, 1815–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceresnak, S.R.; Liberman, L.; Silver, E.S.; Fishberger, S.B.; Gates, G.J.; Nappo, L.; Mahgerefteh, J.; Pass, R.H. Lone Atrial Fibrillation in the Young–Perhaps Not So “Lone”? J. Pediatr. 2013, 162, 827–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constante, A.D.; Suarez, J.; Lourenço, G.; Portugal, G.; Cunha, P.S.; Oliveira, M.M.; Trigo, C.; Pinto, F.F.; Laranjo, S. Prevalence, Management, and Outcomes of Atrial Fibrillation in Paediatric Patients: Insights from a Tertiary Cardiology Centre. Medicina 2024, 60, 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, E.P.; Cecchin, F. Arrhythmias in Adult Patients with Congenital Heart Disease. Circulation 2007, 115, 534–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, L.E.; Pflaumer, A. Review of Atrial Fibrillation for the General Paediatrician. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2021, 57, 1564–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentzel, A.; Mabhida, S.E.; Ndlovu, M.; Mokoena, H.; Esterhuizen, B.; Sekgala, M.D.; Dludla, P.V.; Kengne, A.P.; Mchiza, Z.J. Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome in Children and Adolescents with Obesity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Obesity 2024, 33, 12–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, L.; Hune, L.J.; Vestergaard, P. Overweight and Obesity as Risk Factors for Atrial Fibrillation or Flutter: The Danish Diet, Cancer, and Health Study. Am. J. Med. 2005, 118, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, L. Lone Atrial Fibrillation: Good, Bad, or Ugly? Circulation 2007, 115, 3040–3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Assaad, I.; Al-Kindi, S.G.; Saarel, E.V.; Aziz, P.F. Lone Pediatric Atrial Fibrillation in the United States: Analysis of Over 1500 Cases. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2017, 38, 1004–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamura, T.; Hayakawa, T.; Kadowaki, T.; Kita, Y.; Okayama, A.; Elliott, P.; Ueshima, H.; NIPPONDATA80 Research Group. Resting Heart Rate and Cause-Specific Death in a 16.5-Year Cohort Study of the Japanese General Population. Am. Heart J. 2004, 147, 1024–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thanassoulis, G.; Massaro, J.M.; O’Donnell, C.J.; Hoffmann, U.; Levy, D.; Ellinor, P.T.; Wang, T.J.; Schnabel, R.B.; Vasan, R.S.; Fox, C.S.; et al. Pericardial Fat Is Associated with Prevalent Atrial Fibrillation: The Framingham Heart Study. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2010, 3, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahrori, Z.; Chedid El Helou, M.; Sallam, S.; Iacobellis, G.; Neeland, I.J. The Role of Pericardial Fat in Cardiometabolic Disease: Emerging Evidence and Therapeutic Potential. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2025, 27, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Chekakie, M.O.; Welles, C.C.; Metoyer, R.; Ibrahim, A.; Shapira, A.R.; Cytron, J.; Santucci, P.; Wilber, D.J.; Akar, J.G. Pericardial Fat Is Independently Associated with Human Atrial Fibrillation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010, 56, 784–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatem, S.N. Is Epicardial Adipose Tissue an Epiphenomenon or a New Player in the Pathophysiology of Atrial Fibrillation? Arch. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2014, 107, 349–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mahajan, R.; Lau, D.H.; Brooks, A.G.; Shipp, N.J.; Manavis, J.; Wood, J.P.M.; Finnie, J.W.; Samuel, C.S.; Royce, S.G.; Twomey, D.J.; et al. Electrophysiological, Electroanatomical, and Structural Remodeling of the Atria as Consequences of Sustained Obesity. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 66, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venteclef, N.; Guglielmi, V.; Balse, E.; Gaborit, B.; Cotillard, A.; Atassi, F.; Amour, J.; Leprince, P.; Dutour, A.; Clement, K.; et al. Human Epicardial Adipose Tissue Induces Fibrosis of the Atrial Myocardium through the Secretion of Adipo-Fibrokines. Eur. Heart J. 2015, 36, 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aviles, R.J.; Martin, D.O.; Apperson-Hansen, C.; Houghtaling, P.L.; Rautaharju, P.; Kronmal, R.A.; Tracy, R.P.; Van Wagoner, D.R.; Psaty, B.M.; Lauer, M.S.; et al. Inflammation as a Risk Factor for Atrial Fibrillation. Circulation 2003, 108, 3006–3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Sulek, K.; Stinson, S.E.; Holm, L.A.; Kim, M.; Trost, K.; Hooshmand, K.; Lund, M.A.V.; Fonvig, C.E.; Juel, H.B.; et al. Lipid Profiling Identifies Modifiable Signatures of Cardiometabolic Risk in Children and Adolescents with Obesity. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goeller, M.; Achenbach, S.; Marwan, M.; Doris, M.K.; Cadet, S.; Commandeur, F.; Chen, X.; Slomka, P.J.; Gransar, H.; Cao, J.J.; et al. Epicardial Adipose Tissue Density and Volume Are Related to Subclinical Atherosclerosis, Inflammation and Major Adverse Cardiac Events in Asymptomatic Subjects. J. Cardiovasc. Comput. Tomogr. 2018, 12, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, G.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Ge, W.; Kang, Y.; Guo, S. The PD-1 with PD-L1 Axis Is Pertinent with the Immune Modulation of Atrial Fibrillation by Regulating T Cell Excitation and Promoting the Secretion of Inflammatory Factors. J. Immunol. Res. 2022, 2022, 3647817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Apostolakis, S. Inflammation in Atrial Fibrillation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012, 60, 2263–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gramley, F.; Lorenzen, J.; Jedamzik, B.; Gatter, K.; Koellensperger, E.; Munzel, T.; Pezzella, F. Atrial Fibrillation Is Associated with Cardiac Hypoxia. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2010, 19, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, L.; Feng, J.; Gaspo, R.; Li, G.-R.; Wang, Z.; Nattel, S. Ionic Remodeling Underlying Action Potential Changes in a Canine Model of Atrial Fibrillation. Circ. Res. 1997, 81, 512–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heijman, J.; Voigt, N.; Nattel, S.; Dobrev, D. Cellular and Molecular Electrophysiology of Atrial Fibrillation Initiation, Maintenance, and Progression. Circ. Res. 2014, 114, 1483–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idil, S.; Yildiz, K.; Ayranci, I.; Catli, G.; Dundar, B.N.; Karadeniz, C. Evaluation of the Effects of Insulin Resistance on ECG Parameters in Obese Children. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 27, 8754–8761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellulu, M.S.; Patimah, I.; Khaza’ai, H.; Rahmat, A.; Abed, Y. Obesity and Inflammation: The Linking Mechanism and the Complications. Arch. Med. Sci. 2017, 13, 851–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogi, H.; Okamura, H.; Kida, T.; Yamaguchi, O.; Hikoso, S.; Takeda, T.; Tani, T.; Otsu, K. Is Structural Remodeling of Fibrillated Atria the Consequence of Tissue Hypoxia? Circ. J. 2010, 74, 1815–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shu, H.; Cheng, J.; Li, N.; Zhang, Z.; Nie, J.; Peng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, D.W.; Zhou, N. Obesity and Atrial Fibrillation: A Narrative Review from Arrhythmogenic Mechanisms to Clinical Significance. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2023, 22, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, R.; Khairunnisa, K.; Gu, Y.; Tee, N.; Yin, N.O.; Naylynn, T.M.; Moe, K.T. Role of Tumor Necrosis Factor-α in the Pathogenesis of Atrial Fibrosis and Development of an Arrhythmogenic Substrate. Circ. J. 2013, 77, 1171–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kao, Y.-H.; Chen, Y.-C.; Cheng, C.-C.; Lee, T.-I.; Chen, Y.-J.; Chen, S.-A. Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha Decreases Sarcoplasmic Reticulum Ca2+-ATPase Expressions via the Promoter Methylation in Cardiomyocytes. Crit. Care Med. 2010, 38, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, Y.S.; Chi, S.Y.; Shin, H.J.; Kim, E.Y.; Yoon, B.K.; Ban, H.J.; Oh, I.J.; Kim, K.S.; Kim, Y.C.; Lim, S.C. Plasma C-Reactive Protein and Endothelin-1 Level in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Pulmonary Hypertension. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2010, 25, 1487–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Chang, G.; Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Cheng, D.; Tang, Y.; Sang, H. IL-6-miR-210 Suppresses Regulatory T Cell Function and Promotes Atrial Fibrosis by Targeting Foxp3. Mol. Cells 2020, 43, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Zhang, S.; Yang, S.; Lu, Y.; Lu, K.; Wu, Y.; Wu, Q.; Zhao, N.; Dong, Q.; Chen, L.; et al. Interleukin-6-Mediated-Ca2+ Handling Abnormalities Contributes to Atrial Fibrillation in Sterile Pericarditis Rats. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 758157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuerer, M.; Herrero, L.; Cipolletta, D.; Naaz, A.; Wong, J.; Nayer, A.; Lee, J.; Goldfine, A.B.; Benoist, C.; Shoelson, S.; et al. Lean, but Not Obese, Fat Is Enriched for a Unique Population of Regulatory T Cells That Affect Metabolic Parameters. Nat. Med. 2009, 15, 930–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, B.; Yuan, P.; Du, X.; Jin, H.; Du, J.; Huang, Y. Hypoxia Inducible Factor-1α Is an Important Regulator of Macrophage Biology. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancello, R.; Henegar, C.; Viguerie, N.; Taleb, S.; Poitou, C.; Rouault, C.; Coupaye, M.; Pelloux, V.; Hugol, D.; Bouillot, J.-L.; et al. Reduction of Macrophage Infiltration and Chemoattractant Gene Expression Changes in White Adipose Tissue of Morbidly Obese Subjects after Surgery-Induced Weight Loss. Diabetes 2005, 54, 2277–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samman Tahhan, A.; Sandesara, P.B.; Hayek, S.S.; Alkhoder, A.; Chivukula, K.; Hammadah, M.; Mohamed-Kelli, H.; O’Neal, W.T.; Topel, M.; Ghasemzadeh, N.; et al. Association between Oxidative Stress and Atrial Fibrillation. Heart Rhythm 2017, 14, 1849–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Kang, P.M. Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Treatments in Cardiovascular Diseases. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefranc, C.; Friederich-Persson, M.; Palacios-Ramirez, R.; Nguyen Dinh Cat, A. Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress in Obesity: Role of the Mineralocorticoid Receptor. J. Endocrinol. 2018, 238, R143–R159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urlacher, S.S.; Kim, E.Y.; Luan, T.; Young, L.J.; Adjetey, B. Minimally Invasive Biomarkers in Human and Non-Human Primate Evolutionary Biology: Tools for Understanding Variation and Adaptation. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2022, 34, e23811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.L.; Chiou, C.-C.; Chang, P.-Y.; Wu, J.T. Urinary 8-OHdG: A Marker of Oxidative Stress to DNA and a Risk Factor for Cancer, Atherosclerosis and Diabetes. Clin. Chim. Acta 2004, 339, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kehm, R.; Baldensperger, T.; Raupbach, J.; Höhn, A. Protein Oxidation - Formation Mechanisms, Detection and Relevance as Biomarkers in Human Diseases. Redox Biol. 2021, 42, 101901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrow, V.; Wu, S.; Aguilar, A.; Bonner, R., Jr.; Suarez, E.; De Luca, F. Association between Oxidative Stress and Masked Hypertension in a Multi-Ethnic Population of Obese Children and Adolescents. J. Pediatr. 2011, 158, 628–633.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupérez, A.I.; Mesa, M.D.; Anguita-Ruiz, A.; González-Gil, E.M.; Vázquez-Cobela, R.; Moreno, L.A.; Gil, Á.; Gil-Campos, M.; Leis, R.; Bueno, G.; et al. Antioxidants and Oxidative Stress in Children: Influence of Puberty and Metabolically Unhealthy Status. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, S.A.; Saad, E.A.; Elsharkawy, A.A.; Attia, Z.R. Pro-Inflammatory Adipocytokines, Oxidative Stress, Insulin, Zn and Cu: Interrelations with Obesity in Egyptian Non-Diabetic Obese Children and Adolescents. Adv. Med. Sci. 2015, 60, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecoraro, L.; Zoller, T.; Atkinson, R.L.; Nisi, F.; Antoniazzi, F.; Cavarzere, P.; Piacentini, G.; Pietrobelli, A. Supportive Treatment of Vascular Dysfunction in Pediatric Subjects with Obesity: The OBELIX Study. Nutr. Diabetes 2022, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.P.; Gu, J.F.; Tan, X.B.; Wang, C.F.; Jia, X.B.; Feng, L.; Liu, J.P. Curcumin Inhibits Advanced Glycation End Product-Induced Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Responses in Endothelial Cell Damage via Trapping Methylglyoxal. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 13, 1475–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Spuy, W.J.; Pretorius, E. Is the Use of Resveratrol in the Treatment and Prevention of Obesity Premature? Nutr. Res. Rev. 2009, 22, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocaadam, B.; Şanlier, N. Curcumin, an Active Component of Turmeric (Curcuma longa), and Its Effects on Health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 2889–2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesheiwat, Z.; Goyal, A.; Jagtap, M. Atrial Fibrillation. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526072/ (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Duncan, M.J.; James, L.; Griffiths, L. The Relationship between Resting Blood Pressure, Body Mass Index and Lean Body Mass Index in British Children. Ann. Hum. Biol. 2011, 38, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joglar, J.A.; Chung, M.K.; Armbruster, A.L.; Benjamin, E.J.; Chyou, J.Y.; Cronin, E.M.; Deswal, A.; Eckhardt, L.L.; Goldberger, Z.D.; Gopinathannair, R.; et al. 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Atrial Fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2024, 149, e1–e156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampl, S.E.; Hassink, S.G.; Skinner, A.C.; Armstrong, S.C.; Barlow, S.E.; Bolling, C.F.; Edwards, K.C.A.; Eneli, I.; Hamre, R.; Joseph, M.M.; et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Obesity. Pediatrics 2023, 151, e2022060640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pecoraro, L.; De Musso, M.; Benelli, M.; Rosati, E.; Indrio, F. An Adult Arrhythmia in a Child’s Heart: A Case Report of Unexplained Atrial Fibrillation. Reports 2025, 8, 264. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8040264

Pecoraro L, De Musso M, Benelli M, Rosati E, Indrio F. An Adult Arrhythmia in a Child’s Heart: A Case Report of Unexplained Atrial Fibrillation. Reports. 2025; 8(4):264. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8040264

Chicago/Turabian StylePecoraro, Luca, Marta De Musso, Marzia Benelli, Enrico Rosati, and Flavia Indrio. 2025. "An Adult Arrhythmia in a Child’s Heart: A Case Report of Unexplained Atrial Fibrillation" Reports 8, no. 4: 264. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8040264

APA StylePecoraro, L., De Musso, M., Benelli, M., Rosati, E., & Indrio, F. (2025). An Adult Arrhythmia in a Child’s Heart: A Case Report of Unexplained Atrial Fibrillation. Reports, 8(4), 264. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8040264