Abstract

The blast-wave model with Boltzmann–Gibbs statistics is used to examine the transverse momentum spectra of mesons generated at the Relativistic High-Energy Collider (RHIC) Beam Energies with mid-rapidity () in symmetric collisions. There is a clear correlation between the extracted kinetic freeze-out temperature () and transverse flow velocity () in various collision centralities and center-of-mass energies (). Since a larger initial energy density delays freeze-out and a shorter system lifetime limits cooling, is directly proportional to both and peripheral collisions. On the other hand, drops in peripheral symmetric collisions due to weaker collective expansion, while it rises with because of larger pressure gradients. The concurrence between the thermal and collective energy components in the expanding fireball is reflected in the obvious anti-correlation between and . These findings support hydrodynamic predictions and offer important new information about QGP’s freeze-out behavior.

1. Introduction

It has been demonstrated, through particle collider experiments, that protons and neutrons are formed of quarks tied together by gluons via the strong nuclear force; however, the temperatures and energy densities in symmetric and asymmetric heavy-ion collisions are extremely high, resulting in a failure in this binding mechanism and leading to the formation of quark–gluon plasma (QGP)—a state of matter in which quarks and gluons become deconfined [1,2,3,4,5]. This exotic phase makes independent survival unattainable for both individual quarks and gluons, as the strong interacting medium acts as a nearly perfect fluid with a typically low viscosity. Three fundamental areas of physics are revealed by studying the properties of QGP: the nature of the strong nuclear force that binds quarks into hadrons and other particles, the behavior of matter under extreme conditions, and the evolution of the early universe before hadron formation [6,7,8,9,10].

At Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL), the relativistic heavy ion collider (RHIC) and the beam energy scan (BES) are intended to study the nature of confinement and deconfinement transitions, the root of baryon and meson resonances, the phase pattern of QCD matter in symmetric and asymmetric high-energy collisions, and the properties of QGP at different energies [11,12,13]. Additionally, as explained by Lattice QCD [14,15], investigations at the BES program can offer crucial information regarding critical limits in the QCD phase diagram where a significant change in the QGP characteristics is anticipated [16,17,18]. Given that it may provide insight into the basic characteristics of quarks and gluons, as well as the nature of the strong force holding them together, information regarding this vital point is highly intriguing. The Beam Energy Scan allows us to map the phase boundary between confined hadronic matter and the QGP by identifying non-monotonic changes in bulk observables and transport properties and, unlike experiments at a single energy, allows us to search for the hypothesized critical point by varying the baryon chemical potential (). Besides, it gives us significant experimental constraints on the Equation-of-State at high baryon density—a regime that is directly relevant to neutron star interiors and notoriously challenging for theoretical lattice QCD calculations [19]. The BES program also helps us to understand how the transport properties of the strongly coupled medium, such as its viscosity, can emerge from the underlying dynamics of quarks and gluons under varying extreme conditions by measuring the evolution of collective flow and other manifestations of deconfinement across energies. Therefore, the special strength of BES data is in its capacity to disclose the basic characteristics of strong force matter as they vary with temperature and density, which serves as a crucial key to revealing QCD’s phase structure. In the upcoming years, the BES initiative is also anticipated to improve our knowledge of the characteristics of QCD matter.

Temperature is one of the most essential factors that merit inclusion in the creation of QGP matter. Furthermore, different temperature scales are used to characterize the evolution of the system in heavy-ion collisions, from the first impact to the ultimate emission. The initial temperature, chemical freeze-out temperature, kinetic freeze-out temperature, and effective temperature are the critical temperatures. Each of these contributes in a different way to the comprehension of the various stages of the collision [20,21,22,23,24]. The kinetics of particle creation, the transition to hadronic matter, and the formation and characteristics of the Quark–Gluon Plasma (QGP) are all significantly influenced by these temperatures. It is also important to highlight that while the kinetic freeze-out temperature and effective temperature occur at the kinetic freeze-out stage, the flow effect is included only in the effective temperature.

The initial temperature () is the temperature of the system immediately following the collision, when the energy density is sufficiently high to create a deconfined state of quarks and gluons (the QGP) [25,26,27]. After , another temperature is considered: the chemical freeze-out temperature (), which occurs at a later stage of evolution of the system where the inelastic interaction between the hadrons ceases and the particle chemistry is fixed, known as the chemical freeze-out stage [28,29,30]. can be extracted by fitting statistical thermal models to particle yield ratios (e.g., protons, kaons, and pions). The crossover transition temperature predicted by lattice QCD [31,32] is in accordance with the typical values for , which are approximately 150–160 MeV. The importance of the chemical freeze-out temperature lies in its indication of the circumstances in which quarks and gluons hadronize, which in turn provides hints regarding the QCD phase diagram and the characteristics of the transition between deconfined and confined matter.

Elastic collisions keep the hadrons’ local thermal equilibrium as the system cools and expands after chemical freeze-out. The momentum distributions of particles eventually freeze at the last stage of system evolution, where even the elastic interactions cease, and the temperature of the system at this stage is known as the kinetic freeze-out temperature (). Transverse momentum () spectra are generally analyzed using hydrodynamic models, such as blast-wave fits, which account for the radial flow effects to obtain this temperature. Although the effective temperature is not a real temperature, it can be obtained from the heat distribution spectrum. The difference between the kinetic freeze-out temperature and the effective temperature is that the latter includes the flow effect, while both temperatures occur at the last stage of system evolution, and they are both derived from the spectrum of heat dispersion. Additionally, at the thermal (kinetic) freeze-out stage, the degree of excitation of the system is described by the kinetic freeze-out temperature and effective temperature [20,23,33,34]. The selection of for the current investigation is predicated on the fact that it investigates the change from collective flow to free-streaming particles, determines the period of the hadronic phase, and constrains the characteristics of the Quark–Gluon Plasma’s transformation into observable matter. Therefore, is a fundamental observable for evaluating hydrodynamic models and mapping the QCD phase diagram.

We would like to emphasize that it is widely accepted that the simultaneous fit of primary stable hadrons (, K, p) is the most effective and conventional approach to deriving the bulk kinetic freeze-out parameters [35]. Instead of replacing that approach, we decided to investigate the resonance as an additional probe that provides special access to the hadronic phase dynamics—a key focus of Beam Energy Scan (BES) research. The (∼4 fm/c) has a short lifetime that is similar to the hadronic phase’s projected lifetime. Moreover, it is extremely sensitive to post-chemical-freeze-out dynamics, in contrast to stable particles, whose yields are frozen upon chemical freeze-out. In addition, its yield can be regenerated by the reverse process or substantially reduced by hadronic regeneration (e.g., + K ⟶ ). Thus, the extraction of its apparent kinetic freeze-out parameters provides important insight into the hadronic phase duration and density. To determine the magnitude of these late-stage effects, these characteristics can be compared to those of stable particles.

2. The Method and Formalism

The blast-wave model integrated with Boltzmann–Gibbs statistics [36,37,38] or with Tsallis statistics [20,39,40,41], the Boltzmann distribution [42,43,44,45], and the alternative method using the Tsallis distribution [46,47] are some of the methods available for the extraction of and . In the alternate approach, represents the cutoff in the linear relation between T and ; T is the effective temperature that accounts for the contributions of thermal motion and flow effect, while represents the rest mass. Moreover, stands for the slope in the linear relation between and , where the mean transverse momentum is represented by and is acting as the mean moving mass. The main objective of this work is to determine the kinetic freeze-out parameters (, ) under the precise and explicit presumption of local thermal equilibrium at the particle decoupling transition. Therefore, the blast-wave Model with Boltzmann–Gibbs Statistics is used, as it yields the following distribution, as per Refs. [36,37,38].

where the transverse momentum , the parameter N refers to the total number of particles in the event sample for a given centrality and energy. The term thus represents the normalized experimental yield per event, and D is the normalized constant. The modified Bessel functions of the first and second kinds are presented as and , respectively. The boost angle is presented as . The relationship between (collective transverse fluid velocity) and (self-similar flow profile) is , where is the flow velocity on the surface, the radial distance from the center of the system is denoted by the letter r, and R is the radius of the freeze-out surface. In this work, we consider the flow profile , as in [36], which leads to . Since has a maximum value of , has a maximum value of . Other research that deals with the blast-wave model using Tsallis statistics, such as [39], considers , which yields , with as the maximum . To represent the centrality from center to periphery, another study [48] uses as a non-integer from less than 1 to greater than 2, leading to a significant variation in . The choice of is flexible because it is a variable that is not overly sensitive. It impacts even though other can be chosen to fit the spectrum. Meanwhile, is likewise impacted by . The reasons behind our selection of are as follows: firstly, fixing n to 2 improves the stability of our fit practically by lowering the number of free parameters, making it possible to extract our key parameters, and , more robustly and reliably. Secondly, in physical terms, the velocity field grows quadratically with the radius, in a hydrodynamic-like expansion with a flow profile parameter of . Additionally, this is well-motivated for a system displaying collective flow since it represents an underlying pressure gradient, even in small collision systems such as collisions. Moreover, this selection is backed by the fundamental blast-wave formalism, as per ref. [36]. It should be noted that the standard blast-wave model with Boltzmann–Gibbs statistics was chosen in this analysis because it is the established framework for directly extracting the collective flow parameters ( and ), which are the main focus of this work, even though Tsallis statistics offer a powerful description of non-extensive systems and particle yields. The Tsallis formalism is often the best way to express the hard , while the blast-wave model with Boltzmann–Gibbs statistics is the most appropriate and widely used technique for explaining the bulk properties of the system.

3. Results and Discussion

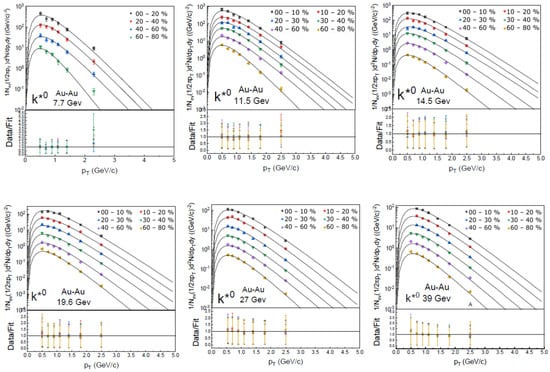

Figure 1 displays the transverse momentum spectra, , for the meson produced at mid-rapidity in symmetric collisions at RHIC Beam energies, as observed at RHIC. The experimental data points (symbols) were supplied by the STAR [49] Collaborations. The solid curves in Equation (1) demonstrate how well we match the blast-wave model with Boltzmann–Gibbs statistics. Table 1 shows the result of the model’s retrieved parameters. Even though the /dof values differ, some are higher than others, a visual examination of Figure 1 shows that the model accurately depicts the general form and evolution of the spectra for all centralities and energies. Although the /dof value is a valuable quantitative measure, it should not be used as the only indicator of goodness of fit; rather, a thorough evaluation necessitates its combination with a visual examination of the fitting outcomes shown in the figure. The distribution of residuals and the visual agreement between the data and the fitted function offer crucial context that the /dof statistic may not accurately convey. Even though the distributions fluctuate in correlation with energy or centrality intervals, nevertheless, /dof values do not exceed the range deemed appropriate for such studies, especially considering the complexity of the dataset and the model used. Essentially, the evident correlation between the fit and the data points indicates the satisfactory and consistent manner of the methodology used to describe the experimental data. Therefore, we conclude that the model can adequately capture the underlying events.

Figure 1.

Transverse momentum spectra of mesons produced in symmetric collisions at RHIC-BES measured by the STAR Collaboration at mid-rapidity . The spectra, represented by color-coded symbols, are dispersed at different centrality intervals, while the curves represent the result of the blast-wave model. The lower panel of each sub-figure presents the data/fit ratio, which indicates the quality of the fit.

Table 1.

Values of free parameters (T, and ), and related to the solid lines in Figure 1.

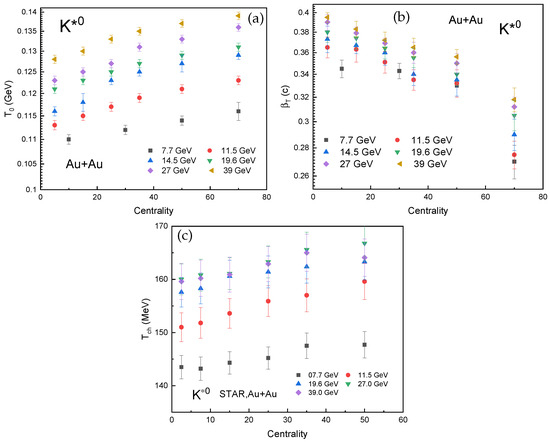

The transverse flow velocity () and the kinetic freeze-out temperature () are shown in Figure 2 as functions of centrality and center-of-mass energy, . Panel (a) displays the result, and panel (b) displays the result. Color-coded symbols represent different energies, and the centrality is indicated by the tendencies of the symbols from left to right. In panel (a), the trend of is gradually increasing toward the periphery along with the rise of . This is due to the system’s subsequent evolution and the high initial energy density. Collisions at higher energies result in a significantly hotter and denser initial state, leading to the production of more particles and an overall increase in the total energy of the system. Because of the extended duration of particle interaction caused by this high initial temperature, the freeze-out process is delayed. Consequently, the elevated is a result of the system retaining a higher amount of thermal energy prior to decoupling. Meanwhile, the high energy particle multiplicity also increases the likelihood of rescattering, which maintains the system’s thermal equilibrium and delays kinetic freeze-out until later, when the temperature is still high. This increase in with is consistently observed in experimental observations over a range of collision energies, from lower-energy heavy-ion collisions to those at the LHC [11,48,50]. This is indicative of a longer lifetime and stronger initial heating of the interacting system. Thus, the higher initial thermal energy and the delayed particle decoupling in high-energy collisions are directly related to the increase in kinetic freeze-out temperature with center-of-mass energy. In contrast, as the system becomes less central, exhibits an increasing trend. Furthermore, examining how the lifetime and interaction dynamics of the system vary with collision centrality helps to explain this trend. The vast overlap region between nuclei in core collisions produces a dense, long-lived system in which particles experience multiple rescatterings over a long time span. Consequently, the final temperature is diminished due to the substantial cooling facilitated by the extended contact phase preceding kinetic freeze-out. On the other hand, peripheral collisions result in smaller, shorter-lived systems with lower particle densities and fewer participant nucleons. When the temperature stays relatively high, the system freezes out early in its evolution due to the reduced spatial extent and shorter evolution time, which restricts the number of particle interactions. Furthermore, the system’s ability to cool effectively is prevented prior to decoupling due to the elevated probability of rescattering caused by the reduced particle multiplicity in peripheral collisions. According to experimental studies, peripheral interactions maintain greater temperatures because of their shorter evolution and less thermalization, while central collisions have lower kinetic freeze-out temperatures as a result of prolonged cooling. The size and lifespan of the system have a fundamental impact on its cooling history and ultimate freeze-out circumstances, as this centrality dependence illustrates.

Figure 2.

Kinetic freeze-out temperature and transverse flow velocity as a function of and event centrality.

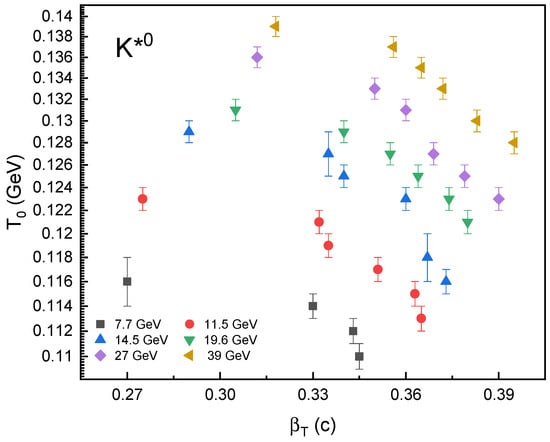

Similarly, the results of are displayed in Figure 2b. Due to fundamental variations in the dynamics of the system’s growth and pressure development, the trend of shows a reduction with decreasing event centrality and an increase with increasing . The huge overlap volume in center collisions produces a high-density system with strong initial pressure gradients that continue to exist throughout the hydrodynamic evolution, resulting in a substantial buildup of transverse flow as the system grows. The extended lifetime of head-on collisions offers these pressure gradients more time to transform thermal energy into collective motion, leading to higher flow velocities. In contrast, peripheral collisions have shorter evolution times and weaker pressure gradients because of the smaller interaction region. When energy dependence is taken into account, collisions with higher produce more extreme initial energy densities and temperatures, which result in stronger initial pressure gradients. At these energies, the system lifetime is longer, giving the flow more time to develop before freeze-out. Due to the higher particle multiplicity at higher energies, the system may sustain these pressure gradients for a longer expansion time. The stronger initial driving forces and longer development times work together to explain why transverse flow velocities increase with collision energy and decrease from central to peripheral collisions. This illustrates how the final collective dynamics observed in heavy-ion collisions are governed by the interaction between initial conditions and system evolution. Figure 2c shows the chemical freeze-out temperature results from Ref. [11]. We use the values obtained from the Strangeness Canonical Ensemble yield fit (SCEY) method to maintain consistency with our analysis, which primarily relies on absolute particle spectra and yields to extract the kinetic freeze-out parameters. The anticipated hierarchical relationship between these basic collision stages is obtained from a simple comparison between our recovered kinetic freeze-out parameter and the chemical freeze-out temperature from the SCEY fit. The epoch of inelastic collision stoppage and fixed particle yields is shown by the SCEY temperatures, which are consistently and significantly greater than our results. In central (0–10%) collisions at 19.6 GeV, for example, our -derived is 121 MeV, whereas the SCEY is 157.6 ± 2.8 MeV. This distinction of approximately 36 MeV is in agreement with the established picture of a cooling fireball where the system first experiences the chemical freeze-out at a higher temperature and then expands and cools through elastic collisions until it kinetically freezes out at a lower temperature. The interpretation that meson probes an intermediate phase, perhaps closer to chemical freeze-out than to the final kinetic decoupling, is further supported by the fact that our values logically fit between the SCEY , and the lower kinetic temperatures extracted from stable hadrons. This quantitative hierarchy, , , , offers a logical thermometric account of the quark–gluon plasma’s evolution. Furthermore, the relationship between and is presented in Figure 3. The negative association of the two parameters can be explained by the interaction of collective expansion and thermal motion in the fireball created following heavy-ion collisions.

Figure 3.

The correlation of with .

The final spectra at the kinetic freeze-out stage show two opposing contributions: (1) collective transverse flow and (2) thermal motion, which is controlled by and results in a random, isotropic distribution of momenta. The system will have a lower effective if it generates a stronger flow (higher ), indicating that a greater percentage of the thermal energy has been transformed into collective motion and less energy remains in the form of random thermal motion. On the other hand, a weak flow (low ) results in a higher measured because more energy is retained as thermal motion. It should be noted that the negative correlation occurs because, for a given initial energy, the system can divide its energy into collective flow (low , high ) or thermal motion (high , low ), but not both at the same time. In addition, it is very important to note that the current behavior of increasing and decreasing with centrality is sensitive to the well-known parameter correlations of the blast-wave model, even if it is physically reasonable. It will be crucial to confirm the exact nature of this relationship in future research using techniques that can control this connected uncertainty more effectively. We acknowledge that this inverse relationship is consistent with hydrodynamic expectations and previous observations. Since this is a known limitation of the model that should be taken into account when evaluating the extracted values, we acknowledge that the precise intensity of this anti-correlation and the associated centrality trends are sensitive to the parameter correlations within the blast-wave framework.

Before going to the next section, it is necessary to acknowledge that the increase of from central to peripheral collisions and the negative correlation between and have been observed in several studies [11,35]. However, the main contribution of our study is not the discovery of this trend but rather demonstrating that this well-known phenomenon is valid for the short-lived resonance. It is not a trivial result that displays the same systematics as stable particles (protons, kaons, and pions). Despite its short lifetime and possible re-scattering effects, it verifies the use of within the blast-wave framework and demonstrates that its spectral shape is sensitive to the system’s collective kinematics. In addition, , , and follow the same trend with the variation of centrality bins as the stable particles do. This demonstrates that the same global collision geometry dynamics also influence the evolution of the hadronic phase, which directly affects the yield and spectrum of the resonance. In this way, the hadronic phase’s centrality dependency using can be investigated. Furthermore, this work presents the first comprehensive extraction of bulk kinetic freeze-out parameters , using short-lived resonance across the RHIC Beam Energy Scan. It illustrates that the resonance is a useful probe of the global freeze-out dynamics driven by collision geometry and expansion, though it is sensitive to complex hadronic re-scattering and regeneration.

4. Conclusions

Fitting the blast-wave model with Boltzmann–Gibbs statistics to the transverse momentum spectra of mesons in symmetric Au–Au collisions at RHIC energies reveals important trends in the transverse flow velocity and kinetic freeze-out temperature as functions of collision centrality and center-of-mass energy.

Two clear trends can be seen in the kinetic freeze-out temperature: (1) an increase with the collision energy as a result of the higher initial energy density, which delays freeze-out and prolongs the system’s evolution, preserving more thermal energy; and (2) an increase from central to peripheral collisions because the smaller, shorter-lived systems in peripheral interactions freeze out earlier with less cooling.

On the other hand, the transverse flow velocity decreases from central to peripheral collisions. This behavior is caused by weaker pressure gradients and shorter system lifetimes in less central events, while it increases with because of stronger initial pressure gradients and longer expansion times at higher energies.

Hydrodynamic expansion is characterized by the distinctive anti-correlation between and . A longer and more vigorous expansion lowers the freeze-out temperature by enhancing cooling and raising . This inverse relationship is in line with earlier experimental results and hydrodynamic predictions.

Our results are consistent with earlier research carried out at the same beam energy. In particular, the anti-correlation between and is reproduced, indicating the exchange of the thermal and collective energy components within the expanding fireball. This pattern suggests an inverse correlation between the radial flow and the kinetic freeze-out temperature, which supports the expected exchange of energy between thermal and collective components. These findings support hydrodynamic hypotheses and provide crucial information about QGP’s freeze-out behavior.

Author Contributions

The authors contributed to the paper as follows: conceptualization, P.-P.Y. and A.H.I.; methodology, P.-P.Y. and A.H.I.; software, P.-P.Y. and A.H.I.; validation, P.-P.Y. and A.H.I.; formal analysis, P.-P.Y. and A.H.I.; investigation, P.-P.Y. and A.H.I.; resources, P.-P.Y. and A.H.I.; data curation, P.-P.Y. and A.H.I.; writing original draft preparation, P.-P.Y. and A.H.I.; writing review and editing, P.-P.Y. and A.H.I.; visualization, P.-P.Y. and A.H.I.; supervision, P.-P.Y. and A.H.I.; project administration, P.-P.Y. and A.H.I.; funding acquisition, P.-P.Y. and A.H.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Ajman University, grant number 2025-IRG-CHS-6, Fudamental Research Program of Shanxi Province under grant No. 202203021222308, Collge level project of Xinzhou Normal University under grant No. 2024RC10 and 2024RC10B, and the Doctoral Scientific Research Foundations of Shanxi Province and Xinzhou Normal University.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of Ajman University Internal Research Grant No. [DRGS Ref. 2025-IRG-CHS-6], Fudamental Research Program of Shanxi Province [No. 202203021222308], Collge level project of Xinzhou Normal University [No. 2024RC10] and [No. 2024RC10B], and the Doctoral Scientific Research Foundations of Shanxi Province and Xinzhou Normal University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Satz, H.; Stock, R. Quark Matter: The Beginning. Nucl. Phys. A 2016, 956, 898–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Di Toro, M.; Shao, G.Y.; Greco, V.; Shen, C.W.; Li, Z.H. Hadron-quark phase coexistence in a hybrid MIT-Bag model. Eur. Phys. J. A 2011, 47, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohr, H.; Nielsen, H. Hadron Production from a Boiling Quark Soup. Nucl. Phys. B 1977, 128, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabibbo, N.; Parisi, G. Exponential hadronic spectrum and quark liberation. Phys. Lett. B 1975, 59, 67–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, J.C.; Perry, M.J. Superdense Matter: Neutrons or Asymptotically Free Quarks? Phys. Rev. Lett. 1975, 34, 1353–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Gyulassy, M. Open charm as a probe of preequilibrium dynamics in nuclear collisions? Phys. Rev. C Erratum in Phys. Rev. C 1995, 52, 440. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.52.440. 1995, 51, 2177–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, C.P.; Casella, G. Monte Carlo Statistical Methods, 2nd ed.; Springer Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kharzeev, D.; Tuchin, K. Bulk viscosity of QCD matter near the critical temperature. J. High Energy Phys. 2008, 9, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karsch, F.; Kharzeev, D.; Tuchin, K. Universal properties of bulk viscosity near the QCD phase transition. Phys. Lett. B 2008, 663, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephanov, M. QCD Phase Diagram and the Critical Point. Prog. Theor. Phys. Suppl. 2004, 153, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczyk, L.; Adkins, J.K.; Agakishiev, G.; Aggarwal, M.M.; Ahammed, Z.; Ajitanand, N.N.; Alekseev, I.; Anderson, D.M.; Aoyama, R.; Aparin, A.; et al. Bulk properties of the medium produced in relativistic heavy-ion collisions from the beam energy scan program. Phys. Rev. C 2017, 96, 044904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokarev, M.; Kechechyan, A.; Zborovský, I. Validation of z-scaling for negative particle production in Au + Au collisions from BES-I at STAR. Nucl. Phys. A 2020, 993, 121646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, L. STAR Results from the RHIC Beam Energy Scan-I. Nucl. Phys. A 2013, 904–905, 256c–263c. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laermann, E.; Philipsen, O. The Status of lattice QCD at finite temperature. Annu. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 2003, 53, 163–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, A.N. Lattice QCD Thermodynamics and RHIC-BES Particle Production within Generic Nonextensive Statistics. Phys. Part. Nucl. Lett. 2018, 15, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleymans, J.; Redlich, K. Chemical and thermal freezeout parameters from 1-A/GeV to 200-A/GeV. Phys. Rev. C 1999, 60, 054908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becattini, F.; Manninen, J.; Gaździcki, M. Energy and system size dependence of chemical freeze-out in relativistic nuclear collisions. Phys. Rev. C 2006, 73, 044905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andronic, A.; Braun-Munzinger, P.; Stachel, J. Hadron production in central nucleus–nucleus collisions at chemical freeze-out. Nucl. Phys. A 2006, 772, 167–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masayuki, A.; Koichi, Y. Chiral restoration at finite density and temperature. Nucl. Phys. A 1989, 504, 668–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, J.; Adamczyk, L.; Adams, J.R.; Adkins, J.K.; Agakishiev, G.; Aggarwal, M.M.; Ahammed, Z.; Alekseev, I.; Anderson, D.M.; Aoyama, R.; et al. Centrality and transverse momentum dependence of D0-meson production at mid-rapidity in Au+Au collisions at = 200 GeV. Phys. Rev. C 2019, 99, 034908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Li, C.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, W.; Zheng, H. Collective expansion in pp collisions using the Tsallis statistics. J. Phys. G Nucl. Part. Phys. 2022, 49, 115101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.-C.; Wang, Y.-Z.; Liu, F.-H. Formulation of transverse mass distributions in Au-Au collisions at = 200 GeV/nucleon. Phys. Lett. B 2013, 725, 352–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, M.; Peng, G.X.; Wazir, Z.; Lao, H.-L. Analysis of kinetic freeze-out temperature and transverse flow velocity in nucleus–nucleus and proton–proton collisions at same center-of-mass energy. Int. J. Mod. Phys. E 2021, 30, 2150061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.X.; Liu, L.L.; Wang, E.Q.; Liu, F.H. Charged particle pseudorapidity distributions in high energy p- or p-p collisions and the improved multi-source thermal model. Indian J. Phys. 2012, 87, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, M.; Liu, L.M.; Peng, G.X.; Ajaz, M.; Haj Ismail, A.A.; Dawi, E.A.; Khubrani, A.M. Observation of non-homogeneous scenarios for different temperatures in hadron(nucleus)-nucleus collisions at RHIC and LHC energies. Chin. J. Phys. 2022, 80, 206–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, F.-H.; Olimov, K.K. Initial- and Final-State Temperatures of Emission Source from Differential Cross-Section in Squared Momentum Transfer in High-Energy Collisions. Adv. High Energy Phys. 2021, 2021, 6677885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, F.-H.; Olimov, K.K. Initial-State Temperature of Light Meson Emission Source From Squared Momentum Transfer Spectra in High-Energy Collisions. Front. Phys. 2021, 9, 792039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun-Munzinger, P. Chemical eguilibration and the hadron–QGP phase transition. Nucl. Phys. A 2001, 681, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, T.; Tsuda, K. Collective flow and two-pion correlations from a relativistic hydrodynamic model with early chemical freeze-out. Phys. Rev. C 2002, 66, 54905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinz, U.; Kestin, G. Universal chemical freezeout as a phase transition signature. Proc. Sci. 2006, CPOD2006, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, Y.; Endrődi, G.; Fodor, Z.; Katz, S.D.; Szabó, K.K. The order of the quantum chromodynamics transition predicted by the standard model of particle physics. Nature 2006, 443, 675–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Christ, N.H.; Datta, S.; van der Heide, J.; Jung, C.; Karsch, F.; Kaczmarek, O.; Laermann, E.; Mawhinney, R.D.; Miao, C.; et al. The QCD equation of state with almost physical quark masses. Phys. Rev. D 2008, 77, 014511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajaz, M.; Khubrani, A.M.; Waqas, M.; Ismail, A.A.K.H.; Dawi, E.A. Collective properties of hadrons in comparison of models prediction in pp collisions at 7 TeV. Results Phys. 2022, 36, 105433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, M.; Chen, H.-M.; Peng, G.-X.; Ismail, A.A.K.H.; Ajaz, M.; Wazir, Z.; Shehzadi, R.; Jamal, S.; AbdelKader, A. Study of Kinetic Freeze-Out Parameters as a Function of Rapidity in pp Collisions at CERN SPS Energies. Entropy 2021, 23, 1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, S.; Das, S.; Kumar, L.; Mishra, D.; Mohanty, B.; Sahoo, R.; Sharma, N. Freeze-Out Parameters in Heavy-Ion Collisions at AGS, SPS, RHIC, and LHC Energies. Adv. High Energy Phys. 2015, 2015, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnedermann, E.; Sollfrank, J.; Heinz, U. Thermal phenomenology of hadrons from 200AGeV S+S collisions. Phys. Rev. C 1993, 48, 2462–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abelev, B.I.; Aggarwal, M.M.; Ahammed, Z.; Alakhverdyants, A.V.; Anderson, B.D.; Arkhipkin, D.; Averichev, G.S.; Balewski, J.; Barannikova, O.; Barnby, L.S.; et al. Identified particle production, azimuthal anisotropy, and interferometry measurements in Au+Au collisions at s(NN)**(1/2) = 9.2 GeV. Phys. Rev. C 2010, 81, 24911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abelev, B.I.; Aggarwal, M.M.; Ahammed, Z.; Anderson, B.D.; Arkhipkin, D.; Averichev, G.S.; Bai, Y.; Balewski, J.; Barannikova, O.; Barnby, L.S.; et al. Systematic Measurements of Identified Particle Spectra in pp, d+ Au and Au+Au Collisions from STAR. Phys. Rev. C 2009, 79, 034909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Ruan, L.; van Buren, G.; Wang, F.; Xu, Z. Spectra and radial flow in relativistic heavy ion collisions with Tsallis statistics in a blast-wave description. Phys. Rev. C 2009, 79, 051901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, M.; Hassan, B.; Alnakhlani, A.; Ajaz, M.; Altalbe, A.; Ghodhbani, R.; Ismail, A.H. Bulk properties of the system in Au–Au collisions at 3 GeV and their dependence on collision centrality and particle rapidity. Results Phys. 2024, 64, 107894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, M.; Bietenholz, W.; Bouzidi, M.; Ajaz, M.; Haj Ismail, A.A.; Saidani, T. Analyzing the correlation between thermal and kinematic parameters in various multiplicity classes within 7 and 13 TeV pp collisions. J. Phys. G 2024, 51, 075102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.-R.; Liu, F.-H.; A Lacey, R. Disentangling random thermal motion of particles and collective expansion of source from transverse momentum spectra in high energy collisions. J. Phys. G Nucl. Part. Phys. 2016, 43, 125102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.-R.; Liu, F.-H.; Lacey, R.A. Kinetic freeze-out temperature and flow velocity extracted from transverse momentum spectra of final-state light flavor particles produced in collisions at RHIC and LHC. Eur. Phys. J. A 2016, 52, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiselberg, H.; Levy, A.-M. Elliptic flow and Hanbury-Brown–Twiss correlations in noncentral nuclear collisions. Phys. Rev. C 1999, 59, 2716–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, R. Measurement of D+ meson production in p-Pb collisions with the ALICE detector. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1511.04380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleymans, J.; Worku, D. Relativistic thermodynamics: Transverse momentum distributions in high-energy physics. Eur. Phys. J. A 2012, 48, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Zhu, L. Comparing the Tsallis Distribution with and without Thermodynamical Description in p + p Collisions. Adv. High Energy Phys. 2016, 2016, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abelev, B.; Adam, J.; Adamová, D.; Adare, A.M.; Aggarwal, M.M.; Rinella, G.A.; Agocs, A.G.; Agostinelli, A.; Salazar, S.A.; Ahammed, Z.; et al. Pion, Kaon, and Proton Production in Central Pb–Pb Collisions at = 2.76 TeV. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 109, 252301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, M.S.; Aboona, B.E.; Adam, J.; Adamczyk, L.; Adams, J.R.; Adkins, J.K.; Aggarwal, I.; Aggarwal, M.M.; Ahammed, Z.; Anderson, D.M.; et al. K*0 production in Au+Au collisions at sNN = 7.7, 11.5, 14.5, 19.6, 27, and 39 GeV from the RHIC beam energy scan. Phys. Rev. C 2023, 107, 034907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abelev, B.; Adam, J.; Adamová, D.; Adare, A.; Aggarwal, M.; Rinella, G.A.; Agnello, M.; Agocs, A.; Agostinelli, A.; Ahammed, Z.; et al. Multiplicity Dependence of Pion, Kaon, Proton and Lambda Production in p-Pb Collisions at = 5.02 TeV. Phys. Lett. B 2014, 728, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).