Abstract

Next-generation space observatories for high-energy gamma-ray astrophysics will increase scientific return using onboard machine learning (ML). This is now possible thanks to today’s low-power, radiation-tolerant processors and artificial intelligence accelerators. This paper provides an overview of current and future ML applications in gamma-ray space missions focused on high-energy transient phenomena. We discuss onboard ML use cases that will be implemented in the future, including real-time event detection and classification (e.g., gamma-ray bursts), and autonomous decision-making, such as rapid repointing to transient events or optimising instrument configuration based on the scientific target or environmental conditions.

1. Introduction

Next-generation space observatories for high-energy gamma-ray astrophysics require advanced data handling. Due to limited bandwidth and ground-contact time, these missions will collect increasingly large data volumes that exceed what can be continuously downlinked to Earth. At the same time, many of the most interesting transient phenomena, such as gamma-ray bursts (GRBs), happen at unknown times and locations.

Transient events are found by onboard space instruments or communicated from external alerts, and upcoming and future observatories will significantly increase the number of notifications, making it difficult to rely on ground-based decisions, increasing the risk of missing important follow-up observations. A certain degree of decision-making must be moved onboard. This motivates onboard artificial intelligence (AI) to detect and characterise transient phenomena in real time, allowing an automatic repointing of telescopes to maximise scientific return. This is especially relevant for multi-messenger and multi-wavelength astronomy, where prompt onboard identification, classification, and scientific prioritisation can improve scientific results.

Previous generation of large missions relied on simple onboard triggers (based on count-rate thresholds or basic algorithms) to detect events like GRBs, while event classification and source identification were performed by ground-based pipelines. For example, the Swift satellite pioneered autonomous rapid repointing after detecting GRBs with its Burst Alert Telescope, enabling multi-wavelength follow-up within minutes [1]. The ESA INTEGRAL generated burst alerts that are distributed in real time [2]. The Italian ASI AGILE mission performed real-time transient identification [3]: the onboard software applied configurable rate thresholds and pattern recognition to identify GRBs. Similarly, NASA Fermi has onboard triggers in the Gamma-ray Burst Monitor to identify GRBs in real time [4].

Today’s approach uses nanosatellites to test and deploy advanced onboard data handling systems, including machine learning (ML) on compact, cost-effective platforms. A full report of existing high-energy small missions can be found in [5]. These CubeSat missions illustrate the shift towards embedding miniaturised gamma-ray detectors within a constellation of distributed platforms. This transition is possible thanks to advances in onboard computing hardware with space-qualified or COTS (commercial off-the-shelf) components that can also run ML algorithms aboard satellites [6,7].

The first in-orbit demonstration of this capability was the ESA -Sat-1 satellite in 2020, which used an Intel Movidius Myriad-2 VPU to run a deep convolutional neural network (CNN) for real-time image analysis, representing the first successful use of onboard AI on a satellite [8]. This experience was followed by ESA OPS-SAT [9].

In parallel, the astrophysical community has gained experience in the last two decades by applying ML to data to recognise and to characterise high-energy transients. An overview is presented in Section 2. A growing amount of work is being done to port ground-based ML techniques onboard. Training and validation of these models are still performed mainly on the ground using archival data, but the resulting networks can be uploaded for in-flight inference.

2. Ground-Based Machine Learning Algorithms for Astrophysical Observatories

Event reconstruction (to determine the physical parameters of each event hitting a detector), event discrimination (to discriminate between events like photons and particle background) and detection and classification of astrophysical transient phenomena have been developed using ML since the beginning of high-energy astrophysics.

The AGILE mission [3] has extensively used ML techniques for the identification of high-energy astrophysics transient phenomena in the real-time analysis pipeline [10]. For example, the AGILE Team developed CNN-based methods to detect GRBs in sky maps [11], and to perform anomaly detection using the ratemeter time series of the Anticoincidence System (ACS) for GRBs identification [12,13]. Unsupervised learning has been applied to the Swift light curves on GRB prompt emission data to provide the first clear classification between short and long bursts [14]. The Fermi mission has also benefited from ML approaches, e.g, classifying GRBs [15] and evaluating a data-driven background estimator, also applied to the HERMES constellation [16]. SVOM mission, continues this tradition with advanced onboard GRB detection and localization capabilities [17]

These applications across different missions focus on the fundamental role of ML in transient astrophysics and its role as essential in future gamma-ray missions. However, experience shows that moving from a proof-of-concept to a reliable, deployable tool is significantly more demanding than was foreseen at the beginning of a ML project.

The initial dataset can be provided by real data acquisition or, more commonly, generated with Monte Carlo simulation [18,19,20], but unforeseen effects (e.g., in the detector model) could bias the training. Validation is required across all inputs and outputs by comparing the simulation results with real data [20]. After training, the verification step is one of the most time-consuming tasks of the entire process.

We also face the same problems with onboard AI where the critical aspect is the limitation of edge computing resources, i.e., the restricted processing power available directly onboard compared to ground infrastructures. Edge computing refers to performing data analysis close to the data source, thereby reducing latency and bandwidth usage while enabling autonomous operation in environments with limited connectivity. In space, this concept is constrained by tight power and radiation-hardness requirements that severely limit computational capability. To provide a couple of examples of ground hardware used also in space as a prototype, a Red Pitaya STEMlab board with a dual-core ARM Cortex-A9 at 667 MHz provides ≈1 GFLOPS (floating point operations per second) within a few watts of power consumption. In contrast, a typical server CPU exceeds some TFLOP with a power consumption of several hundred watts, approximately more performance. Similarly, the NVIDIA Jetson Orin Nano GPU delivers ≈ 1 TFLOP FP32 (Floating Point 32 bit precision) at 7–15 W power consumption, compared to >20 TFLOPS FP32 for an NVIDIA A100 at 3–400 W or 156 TFLOPS TF32 (Tensor Float 32 bit precision, for faster tensor operations while maintaining acceptable accuracy for deep learning tasks), a mode not available in the Orion Nano with a different and less effective architecture.

These differences illustrate that onboard AI must rely on highly optimised, lightweight models rather than brute-force computing. The value of edge processing in space lies in achieving autonomy and responsiveness within these strict hardware and power constraints.

Complex deep neural networks that run efficiently in data centres cannot be directly applied in space without substantial simplification. Therefore, a major ongoing effort in this field is the reduction and optimisation of ML models for edge use. Techniques such as network pruning, quantisation, and efficient model architectures are being investigated to shrink model size and computational load while retaining accuracy. Pruning involves removing unnecessary weights from a neural network after or during training to compress the model, reducing model size and computation. Quantisation is the technique of reducing the numerical precision of model parameters and operations. For example, this can involve converting 32-bit floating-point numbers to 8-bit integers, or even to 1-bit binary in extreme cases. Quantisation significantly decreases memory usage and can accelerate inference. There are two types of quantisation:

- post-training quantisation (PTQ): it is applied after the training phase and is easy to implement, but the performance degradation can be high;

- quantisation-aware training (QAT): this technique trains the model by simulating a quantised model. The real model quantisation, achieved after training, results in lower performance degradation because the training process took into account the quantisation effect.

Efficient architectures are another key element of onboard ML because when designing models for space, one might choose architectures known to be efficient.

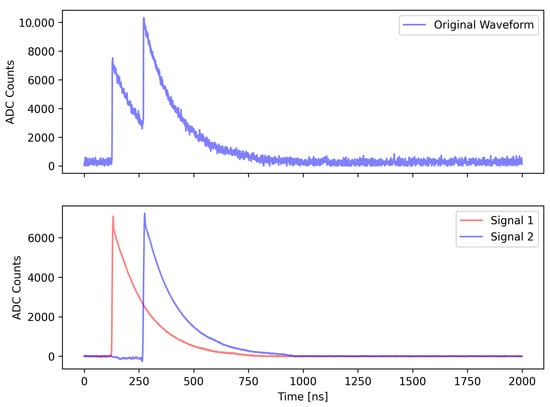

We investigated the impact of pruning and quantisation techniques on a deep learning model developed for the analysis of waveform signals acquired from scintillator detectors. Each waveform corresponds to the electrical response generated by a Silicon Photomultiplier (SiPM) optically coupled to a scintillator. When an X-ray photon interacts with the scintillator material, it produces scintillation light that is collected by the SiPM and converted into an electrical pulse. The amplitude characteristics of this signal are directly related to the energy of the incident X-ray photons. We developed a deep learning model that analyses the waveform and infers the gamma-ray photon energy. The model can also separate the pile-up signals (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Example of pile-up signals separated and reconstructed using the deep learning model. In the top panel, the figure shows the original waveform generated by the SiPM. In the bottom panel the figure shows the two signals separated by the deep learning model.

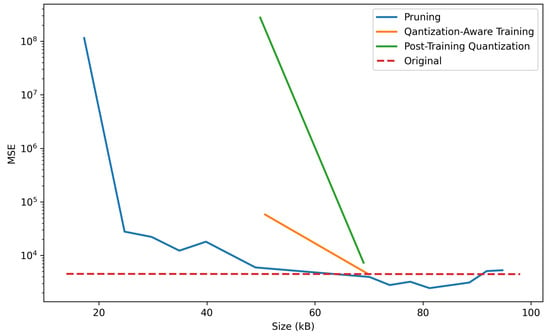

The model is a neural network comprising eight convolutional layers, alternated by eight max pooling layers, and followed by two dense layers. The model employs the tanh activation function, the Huber loss function, and the Adam optimiser with a learning rate of 0.0001. We used the Mean Squared Error (MSE) to evaluate the model’s performance. Then, we measured the MSE of the model as a function of its size (kB) after applying optimisation techniques. The results are shown in Figure 2. The model was developed and trained using Keras https://keras.io/ (accessed on 1 February 2025), then converted to LiteRT https://ai.google.dev/edge/litert (accessed on 1 February 2025). During this conversion, the model size was reduced from 371 kB to 99 kB. The INT8 and FLOAT16 quantisation further reduces the model size to 65 kB and 48 kB, respectively. LiteRT applies quantisation only to the weights, not to the biases. The pruning can still reduce the model size. Considering the model performances, the pruning technique is the best approach for the model we developed, as it offers the best trade-off between performance loss and model size reduction (Figure 2). These results will be presented in a forthcoming work.

Figure 2.

Trade-off between model size reduction and MSE performance degradation. The red dotted line represents the MSE obtained with the full-size model. The other three lines show how the optimization techniques impact the model size reduction and performance degradation.

In summary, ML has the potential to increase the effectiveness of the onboard data processing, but realising this potential requires careful software engineering of algorithms to meet the strict power and performance budgets of onboard computing.

3. Onboard Machine Learning Applications

This section examines specific functions of onboard ML for high-energy astrophysics. Broadly, these use cases fall into the following categories: onboard data reconstruction and analysis, spacecraft autonomy, and ground segment optimisation.

3.1. Onboard Data Reconstruction and Analysis

Event reconstruction, classification, and identification of astrophysical transients are mandatory for fast communication of transients to the ground, enabling spacecraft autonomy (fast repointing or optimisation of onboard instruments) and efficient data transmission. Ground-based machine learning techniques for these tasks can be moved onboard with important advantages for future high-energy space missions.

Reconstructing events in Compton and pair-production telescopes by analysing interaction patterns allows high-level reconstruction of each event onboard, improving the signal-to-background ratio directly onboard. Some examples are reported for AdEPT [21], NUSES [22] and ASTROGAM [23].

Moving the focus to transient phenomena detection, more complex pattern searches or discrimination between different types of events (e.g., short and long GRBs) or noise fluctuations can be evaluated onboard to maximise the probability of detection. All these tasks can be performed more effectively with ML, incorporating complex patterns and more information. Distinguishing different types of events allows the spacecraft to prioritise the response. In addition, forecasting the background level based on orbital parameters increases the detection effectiveness [13,16]. For example, ref. [13] developed a method that uses a deep learning model to predict the background count rates of the AGILE Anticoincidence System top panel (perpendicular to the pointing direction of the payload detectors) using the satellite’s orbital and attitude parameters as input. This prediction is used to detect GRBs by comparing acquired count rates and predictions, with a mean reconstruction error of 3.8%. The model detected 39 GRBs, with four new GRBs detected for the first time in the AGILE data. This demonstrates that this approach, if implemented onboard, can increase the effectiveness of the results.

3.2. Autonomous Decision-Making and Reconfiguration

Autonomous decision-making refers to the spacecraft acting autonomously in response to onboard analyses, without waiting for ground control. High-energy missions often need rapid reactions to maximise the observation of transient events. Onboard ML can empower the spacecraft to make such decisions in a more sophisticated way.

The first example is automatic repointing or retargeting of telescopes. Past and current missions such as NASA’s Swift, Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, ESA INTEGRAL, ASI’s AGILE and SVOM satellites use non-ML software onboard for GRB detection and repointing. With ML, this logic can be more flexible: instead of repointing to any burst above a threshold, the system might evaluate the scientific merit of the detection, estimating the potential relevance of a detected transient event using a set of quantitative and scientific criteria, rather than relying only on a simple signal threshold. Between them, we can train a machine learning model with event classifications (distinguishing astrophysical transient types, e.g., short/long GRBs), physical quantities (brightness, spectral hardness, or temporal structure) and contextual relevance (cross-checks with external alerts or known source catalogues for multi-messenger potential). The spacecraft could then prioritise slewing to that target, even deciding how to allocate observation time.

Another aspect of decision-making is configuring instruments. Some high-energy detectors have several observation modes or tunable settings. An onboard ML system could adjust instrument settings in real time for optimal data collection.

As an example, in missions like THESEUS [24], an AI system can orchestrate a fast slew manoeuvre (>7°/min) of the satellite to bring the infrared telescope to a GRB location identified by the wide-field monitors or communicated by an external observatory. This requires making a decision within seconds and initiating mechanical action. This is critical for GRB science where transients last from ms to hundreds of seconds. Machine learning could be used to combine various trigger information (X-ray location, gamma-ray temporal profile, etc.) and decide when to slew and which transient to follow if multiple one occur. Over the course of a long mission, one could even envision reinforcement learning algorithms that optimise the decision policy for repointing (maximising science return).

Beyond reaction speed for repointing, where we already have many missions that react to onboard triggers, the focus here is onboard ML that allows more sensitive and adaptive transient detection, enabling a more effective autonomous decision-making. Instead of fixed thresholds, algorithms can recognise complex temporal or spectral patterns, increasing the probability of detecting faint or unusual events, based also on an estimation of the background level as described in Section 3.1. In addition, trigger criteria can evolve during the mission as new phenomena are discovered, while unsupervised methods may even identify unknown classes of transients directly onboard.

Finally, running such analyses autonomously is crucial when the satellite is out of ground visibility: more complex processing than past and current missions can be performed onboard without ground intervention, and in addition, only high-level results can be transmitted to Earth. This approach optimises bandwidth and operations.

3.3. Ground Segment Operations and Planning

Onboard ML also impacts the ground segment and operations. In fact, a successful implementation of onboard autonomy necessitates evolution in ground operations. In the past, most high-energy missions transmitted preliminary alerts directly to the Gamma-ray Coordinates Network (GCN) [25]. However, these alerts typically contained basic information, which was subsequently refined manually by the scientific teams or ground-based pipelines. With the advent of onboard ML-driven autonomy, the situation will evolve toward disseminating higher-level results directly from orbit. The ground team of scientists will thus need to intervene much less frequently, progressively transitioning from active operators to supervisors of an almost fully automated alert distribution chain.

On the technical side, ground segments will also manage ML model updates. Mission operations will need procedures to upload new ML models or update existing ones as the mission progresses. This is analogous to sending a software patch and will require careful version control, testing, and fallback mechanisms if a new model behaves unexpectedly.

4. Conclusions

Using onboard machine learning will provide new operational paradigms for high-energy space observatories.

Notable large missions in high-energy astrophysics, such as NASA’s Swift and Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, ESA INTEGRAL and the ASI’s AGILE satellites did not carry AI hardware or complex inference algorithms onboard, but with these missions, the astrophysical community adopted ML for data analysis on the ground. These ground-based ML efforts were critical in guiding follow-up observations of transients and making new discoveries. The future development of onboard ML in space has its foundation in past and current missions and the heritage of machine learning on the ground.

The absence of onboard AI in these earlier missions was largely due to technological limitations, not a lack of interest. Now, with CubeSat missions and the advances in computing hardware for space, we can incorporate advanced computing capabilities into the space segment itself. The lessons learned from ground-based ML applications are the baseline for the onboard implementations and provide confidence that carefully designed ML models are crucial for onboard autonomy. In any case, a lot of research is in progress to reduce the complexity of ML models to fit within a flight computer while achieving the reliability required for the space segment.

In summary, the current situation is a mix of dedicated small demonstrators and new missions under study that are considering how to use or implement onboard ML. They collectively address use cases ranging from single-event reconstruction to astrophysical transient events detection and classification (e.g., recognising a GRB). The accumulated experience suggests that onboard ML can significantly increase the mission’s science return. As we move into the next generation of high-energy astrophysics missions, the integration of edge AI is expected to become commonplace.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization and methodology. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to working in progress for a forthcoming publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Gehrels, N.; Chincarini, G.; Giommi, P.; Mason, K.O.; Nousek, J.A.; Wells, A.A.; White, N.E.; Barthelmy, S.D.; Burrows, D.N.; Cominsky, L.R.; et al. The Swift Gamma-Ray Burst Mission. Astrophys. J. 2004, 611, 1005–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mereghetti, S.; Götz, D.; Borkowski, J.; Walter, R.; Pedersen, H. The INTEGRAL Burst Alert System. Astron. Astrophys. 2003, 411, L291–L297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavani, M.; Barbiellini, G.; Argan, A.; Boffelli, F.; Bulgarelli, A.; Caraveo, P.; Cattaneo, P.W.; Chen, A.W.; Cocco, V.; Costa, E.; et al. The AGILE Mission. Astron. Astrophys. 2009, 502, 995–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meegan, C.; Lichti, G.; Bhat, P.N.; Bissaldi, E.; Briggs, M.S.; Connaughton, V.; Diehl, R.; Fishman, G.; Greiner, J.; Hoover, A.S.; et al. The Fermi Gamma-ray Burst Monitor. Astrophys. J. 2009, 702, 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloser, P.; Murphy, D.; Fiore, F.; Perkins, J. CubeSats for Gamma-Ray Astronomy. In Handbook of X-Ray and Gamma-Ray Astrophysics; Bambi, C., Santangelo, A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furano, G.; Meoni, G.; Dunne, A.; Moloney, D.; Ferlet-Cavrois, V.; Tavoularis, A.; Byrne, J.; Buckley, L.; Psarakis, M.; Voss, K.O.; et al. Towards the use of artificial intelligence on the edge in space systems: Challenges and opportunities. IEEE Aerosp. Electron. Syst. Mag. 2020, 35, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Castillo, M.O.; Morgan, J.; McRobbie, J.; Therakam, C.; Joukhadar, Z.; Mearns, R.; Barraclough, S.; Sinnott, R.O.; Woods, A.; Bayliss, C.; et al. Mitigating Challenges of the Space Environment for Onboard Artificial Intelligence: Design Overview of the Imaging Payload on SpIRIT. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) Workshops, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–18 June 2024; pp. 6789–6798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffrida, G.; Fanucci, L.; Meoni, G.; Batič, M.; Buckley, L.; Dunne, A.; van Dijk, C.; Esposito, M.; Hefele, J.; Vercruyssen, N.; et al. The Φ-Sat-1 mission: The first on-board deep neural network demonstrator for satellite Earth observation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrèche, G.; Evans, D.; Marszk, D.; Mladenov, T.; Shiradhonkar, V.; Soto, T.; Zelenevskiy, V. OPS-SAT Spacecraft Autonomy with TensorFlow Lite, Unsupervised Learning, and Online Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 5–12 March 2022; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulgarelli, A.; Trifoglio, M.; Gianotti, F. The AGILE Alert System for Gamma-Ray Transients. Astrophys. J. 2014, 781, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmiggiani, N.; Bulgarelli, A.; Fioretti, V.; Piano, A.D.; Giuliani, A.; Longo, F.; Verrecchia, F.; Tavani, M.; Macaluso, A. A Deep Learning Method for AGILE-GRID Gamma-Ray Burst Detection. Astrophys. J. 2021, 914, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmiggiani, N.; Bulgarelli, A.; Ursi, A.; Macaluso, A.; Di Piano, A.; Fioretti, V.; Aboudan, A.; Baroncelli, L.; Addis, A.; Tavani, M.; et al. A Deep-Learning Anomaly-Detection Method to Identify Gamma-Ray Bursts in the Ratemeters of the AGILE Anticoincidence System. Astrophys. J. 2023, 945, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmiggiani, N.; Bulgarelli, A.; Castaldini, L.; Rosa, A.D.; Piano, A.D.; Falco, R.; Fioretti, V.; Macaluso, A.; Panebianco, G.; Ursi, A.; et al. A New Deep Learning Model to Detect Gamma-Ray Bursts in the AGILE Anticoincidence System. Astrophys. J. 2024, 973, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jespersen, C.K.; Severin, J.B.; Steinhardt, C.L.; Vinther, J.; Fynbo, J.P.U.; Selsing, J.; Watson, D. An Unambiguous Separation of Gamma-Ray Bursts into Two Classes from Prompt Emission Alone. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2020, 896, L20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, N.; Iyyani, S. Exploring Gamma-Ray Burst Diversity: Clustering analysis of emission characteristics of Fermi and BATSE detected GRBs. Astrophys. J. 2024, 969, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crupi, R.; Dilillo, G.; Della Casa, G.; Fiore, F.; Vacchi, A. Enhancing Gamma-Ray Burst Detection: Evaluation of Neural Network Background Estimator and Explainable AI Insights. Galaxies 2024, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardini, M.G.; Cordier, B.; Wei, J. on behalf of the SVOM Collaboration. The SVOM Mission. Galaxies 2021, 9, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoglauer, A.; Andritschke, R.; Schopper, F. MEGAlib: Simulation and data analysis for low-to-medium-energy gamma-ray telescopes. New Astron. Rev. 2006, 50, 629–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulgarelli, A.; Fioretti, V.; Malaguti, P.; Trifoglio, M.; Gianotti, F. BoGEMMS: The Bologna Geant4 Multi-Mission Simulator. In Proceedings of the Space Telescopes and Instrumentation 2014: Ultraviolet to Gamma-Ray, Montreal, QC, Canada, 22–26 June 2014; Volume 9144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fioretti, V.; Bulgarelli, A.; Tavani, M.; Sabatini, S.; Aboudan, A.; Argan, A.; Cattaneo, P.W.; Chen, A.W.; Donnarumma, I.; Longo, F. AGILESim: Monte Carlo Simulation of the AGILE Gamma-Ray Telescope. Astrophys. J. 2020, 896, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnett, R.L.; Byun, S.H.; Hanu, A.R.; Hunter, S.D. Event selection and background rejection in time projection chambers using convolutional neural networks and a specific application to the AdEPT gamma-ray polarimeter mission. Nucl. Instruments Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2021, 1014, 164860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savina, P.; Smirnov, A., on behalf of The NUSES Collaboration. The Zirè experiment on board of the NUSES mission. EPJ Web Conf. 2025, 319, 12009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lommler, J.P.; Gerd Oberlack, U. CNNCat: Categorizing high-energy photons in a Compton/Pair telescope with convolutional neural networks. Exp. Astron. 2024, 58, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amati, L.; O’Brien, P.; Götz, D.; Bozzo, E.; Santangelo, A.; Tanvir, N.; Frontera, F.; Mereghetti, S.; Osborne, J.P.; Blain, A.; et al. The THESEUS space mission: Science goals, requirements and mission concept. Exp. Astron. 2021, 52, 183–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthelmy, S.D.; Cline, T.L.; Butterworth, P.; Kippen, R.M.; Briggs, M.S.; Connaughton, V.; Pendleton, G.N. GRB Coordinates Network (GCN): A status report. AIP Conf. Proc. 2000, 526, 731–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).