Abstract

Background/Objectives: A healthy lifestyle based on a balanced diet promotes overall well-being and supports brain health, while the consumption of high-energy foods can negatively affect cognitive function, particularly during early developmental stages, such as adolescence. Astrocytes are essential for brain homeostasis, including modulation of neurogenesis in the hippocampus, a region involved in cognitive functions. The impact of short-term high-fat diet (HFD) exposure on astrocytes during adolescence remains unclear. In this study, we examined if brief periods of HFD influence astrocyte morphology, density, and territory volume and, in parallel, the maturation of doublecortin-positive (DCX+) cells in the dorsal hippocampus of adolescent male mice. Methods: We performed 3D reconstructions, analyzed morphometric features as well as other parameters of astrocytes and DCX+ cells following 1 week of HFD (1 w-HFD), 2 weeks of HFD (2 w-HFD), and 1 week of HFD followed by 1 week of return to a low-fat diet (1 w-HFD – 1w-LFD). Results: We observed that 1 w-HFD significantly increased astrocyte morphological complexity and density compared with the control group (1 w-LFD). After 2 w-HFD, astrocyte complexity declined, whereas density was unchanged. Notably, in the 1 w-HFD – 1 w-LFD group, astrocyte complexity was comparable to that of the 2 w-HFD group; density increased compared to both control groups (2 w-LFD and 2 w-HFD). Moreover, both 1 w- and 2 w-HFD impaired granular cell layer (GCL) DCX+ cells density and maturation, and a return to LFD after 1 w-HFD restored maturation but not density. Conclusions: Altogether, these data suggest that short-term HFD exposure has complex effects on GCL astrocytes and impairs DCX+ cell maturation in the dorsal hippocampus of adolescent mice.

1. Introduction

Lifestyle is known to play a key role in neuroplasticity [1,2,3]. A healthy lifestyle characterized by physical activity, adequate sleep, social integration, stress management, and, mainly, a balanced diet, can significantly reduce the risk of brain homeostasis impairment [1,4]. Conversely, an unhealthy lifestyle behavior can significantly increase the risk of developing central nervous system (CNS) detrimental outcomes [5,6,7].

In humans, long-term consumption of a Western diet, which is rich in red meat, refined sugars, grains, and high-fat content, contributes to an unbalanced lifestyle [8]. Evidence highlighted that even short periods of Western diet consumption can affect CNS health, with a more severe effect mainly at young ages [9].

Adolescence represents a critical period for both CNS development and for the establishment of healthy lifestyle behaviors that are likely to persist in adulthood. In humans, an unhealthy lifestyle during adolescence is associated with cognitive deficits that can chronically lead to marked alterations in selected brain structures [10,11,12,13]. Such evidence is corroborated by preclinical studies in rodents, where high-fat diet (HFD) exposure during adolescence negatively affects hippocampal-dependent learning tasks [14,15,16,17,18]. Among other regions, the plasticity of the dorsal hippocampus, a brain structure involved in learning and memory [19,20], is particularly vulnerable to dietary insults. As an example, in male adolescent rats, HFD was shown to induce learning impairments in the conditioned place preference task, with effects that persisted into adulthood [21]. In previous work, our group demonstrated that a very short period of HFD feeding in adolescent male mice dramatically reduced dendritic tree complexity of doublecortin positive immature neurons (DCX+) in dorsal, but not in ventral, hippocampus, and that this effect correlated with a region-specific reduction in Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) expression levels [22]. Moreover, both structural and biochemical alterations were reverted by returning to a low-fat diet (LFD) [22].

Astrocytes provide key signals involved in the modulation of hippocampal newborn neurons and their functions under both physiological and pathological conditions [23,24,25,26]. They play an important role in lipolysis and fatty acid metabolism [27,28], and maintain brain homeostasis [29,30,31]. Of note, the impact of a short period of HFD on hippocampal astrocytes in adolescent mice remains largely unexplored.

For this reason, herein we investigated the effects of a short period of HFD on astrocyte complexity and density in the dorsal hippocampal granular cell layer (GCL) of adolescent male mice. Furthermore, we conducted a more in-depth analysis of the effects of HFD on DCX+ cell maturation in the dorsal hippocampus of the same mice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

Twenty 4-week-old male C57BL/6J mice were utilized. Mice, kept 3–5/cage with access to water and food ad libitum, were housed in a light-(12 h light, 12 h dark) and temperature-(22–24 °C) controlled room in high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA)-filtered Thoren units (Thoren Caging Systems) at the University of Piemonte Orientale animal facility. The 1 w-HFD vs. 1 w-LFD animal set (Study 1) is the same used in previous work [22]. Animal care and handling were performed following the Italian law on animal care (D.L. 26/2014), as well as European Directive (2010/63/UE) and ARRIVE guidelines and approved by the Organismo Preposto al Benessere Animale (OPBA) of University of Piemonte Orientale, Novara, Italy (DB064.61).

2.2. Diet Administration Protocol

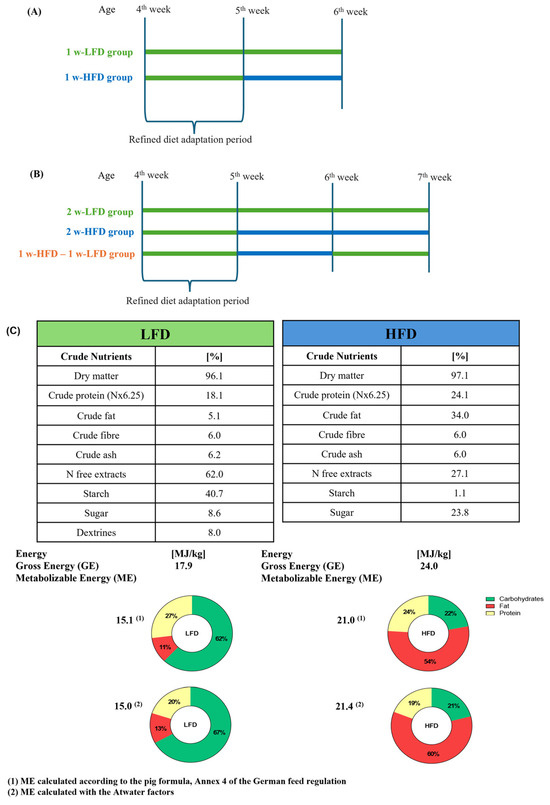

Experimental designs are summarized in Figure 1A,B.

Figure 1.

Experimental designs and diet composition. (A) Schematic experimental design of mice fed 1 w-LFD and 1 w-HFD; (B) Schematic experimental design of mice fed 2 w-LFD, 2 w-HFD, and 1 w-HFD–1 w-LFD; (C) LFD and HFD composition.

Study 1: Eight 4-week-old male mice started receiving a standard low-fat diet (LFD) (13% kcal from fat, 67% kcal from carbohydrates, 20% kcal from proteins, Laboratori Piccioni) for one week [32,33]. After that, animals were randomly divided into 2 groups: the first group continued to be fed with LFD (1 w-LFD group, n = 4 male mice), while the second group of animals was fed with an HFD (60% kcal from fat, 21% kcal from carbohydrates, 19% kcal from proteins, Laboratori Piccioni) (1 w-HFD group, n = 4 male mice) for 1 week. Diet composition is described in Figure 1C.

Study 2: Twelve 4-week-old male mice started LFD as previously described. After 1 week of LFD, animals were randomly divided into 3 groups: the first group continued to be fed with LFD, while the second and third groups of animals were fed with HFD. After another week, the third group of animals was reverted to LFD for another week (1 w-HFD – 1 w-LFD group, n = 4), while the first (2 w-LFD, n = 4) and the second (2 w-HFD, n = 4) groups continued with their diet regimen.

In both experiments, animal body weight and the average values of food/caloric intake per mouse were recorded on day one and weekly thereafter (available data [22]).

2.3. Tissue Preparation for IHC Analysis

At the end of the experimental procedure, mice were anesthetized with a mix of zoletil (zolazepam and tiletamina, 60 mg/kg) and xylazine (20 mg/kg) i.p. and then transcardially perfused first with saline and then with paraformaldehyde (PFA) 4% in 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 7.4, as previously described [22]. Subsequently, brains were rapidly removed, post-fixed in 4% PFA for 24 h, and cryoprotected in 15% sucrose for 24 h, and then transferred into sucrose 30% solution for at least 24 h. 40 μm-thick coronal sections were cut by cryostat, collected and stored in cryoprotectant solution [2:1:1 PB 0.2M; Glycerol (Applichem, Darmstadt, Germany) Ethylene glycol (Carlo Erba, Milan, Italy)] at −20 °C until use.

2.4. Immunohistochemistry

From a complete series of one-in-eight brain sections throughout the hippocampus, four corresponding sections from the dorsal hippocampus (anterior–posterior −1.34 to −2.30 mm from Bregma, according to the Paxinos mouse Brain atlas [34]) were selected for each mouse. Immunohistochemical staining for Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein (GFAP) and Doublecortin (DCX) was performed on free-floating sections as previously described [35,36]. The following primary antibodies were utilized: goat polyclonal anti-GFAP antibody (code: AB53554, 1:5000; Abcam, Cambridge, UK); guinea pig anti-DCX antibody (code: AB2253, 1:18000; Millipore, Burlington, VT, USA).

2.5. Image Acquisition

Image acquisition and analysis were performed as previously described [36] by an operator blinded to mouse brain identity. Confocal 3D images were acquired using the z-stack function of an LSM700 laser-scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss, Le Pecq, France). All images were acquired at 0.4 µm intervals with a 20× objective (1024 × 1024 pixels, 8-bit depth, pixel size 0.313 µm).

2.6. Morphometric Analysis of GFAP+ and DCX+ Cells

For morphometric analysis, 12 astrocytes with fully intact GFAP-immunostained processes were selected in the dorsal GCL of the suprapyramidal blade of the DG in each animal [36]. For morphometric analysis of DCX+ immature neurons, 30 cells were selected in the dentate gyrus of the dorsal hippocampus of each animal based on the following a priori criteria: (i) cells were located in the suprapyramidal blade of the DG; (ii) soma was placed in the inner third of GCL; (iii) dendrites were extending into the outer molecular layer (OML) [22,37]. Three-dimensional reconstructions of astrocytes and DCX+ immature neurons were obtained using FIJI software (version 1.52) with the Simple Neurite Tracer (SNT) plugin, which allows semi-automatic and unbiased reconstruction of the cell, as previously described [38]. The Sholl Intersection Profile (SIP) counts the number of intersections between cell processes and concentric spheres emanating from the center of the cell soma at fixed distances (5 µm), as previously described [36]. Three-dimensional reconstructions were exported as SWC files and analyzed with the SNT or L-measure tool to evaluate additional morphometric features, as previously described [38,39,40].

The territory occupied by each cell was evaluated using 3D convex hull analysis, which measures the volume enclosed by a polygon connecting the terminal points of cellular processes, as previously described [36,38].

2.7. GFAP+ and DCX+ Cell Density and Maturation Stage

For each animal, GFAP+ cells in the GCL and the subgranular zone (SGZ) were counted and expressed as the number of cells/100 μm of the DG, as previously described [41,42]. GFAP+ cells were classified according to their morphology: stellate cells were identified as astrocytes (and were included in the analysis), while radial cells with a main long process were identified as radial glia-like cells (RGLc) and were excluded from the analysis. For DCX+ cell maturation [42], criteria were soma/processes with tangential or radial orientation to the GCL and soma localization in the SGZ or GCL of the DG. Neuroblasts were DCX+ cells with their soma in the SGZ and tangentially oriented, with few or no processes, whereas more mature DCX+ cells had their soma in the GCL, radially oriented, with processes extending toward the molecular layer (ML).

2.8. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses and data visualizations were performed with GraphPad Prism version 8.0.2. A total of four animals per group were included in the analysis, and four sections were evaluated for each animal. For complexity analysis, a linear mixed effects model was used to model the data of each parameter, with animals as a random effect. For statistical Sholl analysis, significant differences were analyzed by mixed-effects nested t-test or a nested one-way ANOVA approach with individual animal as a random effect. For additional morphometric parameters and GFAP+ and DCX+ cell counts, the presence of significant differences was tested using Student’s t-test, one-way or two-way ANOVA. For all analyses, significance was defined as p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. One-Week HFD Is Associated with Increased Morphological Complexity and Territory Volume of Astrocytes in the Dorsal GCL of Adolescent Mice

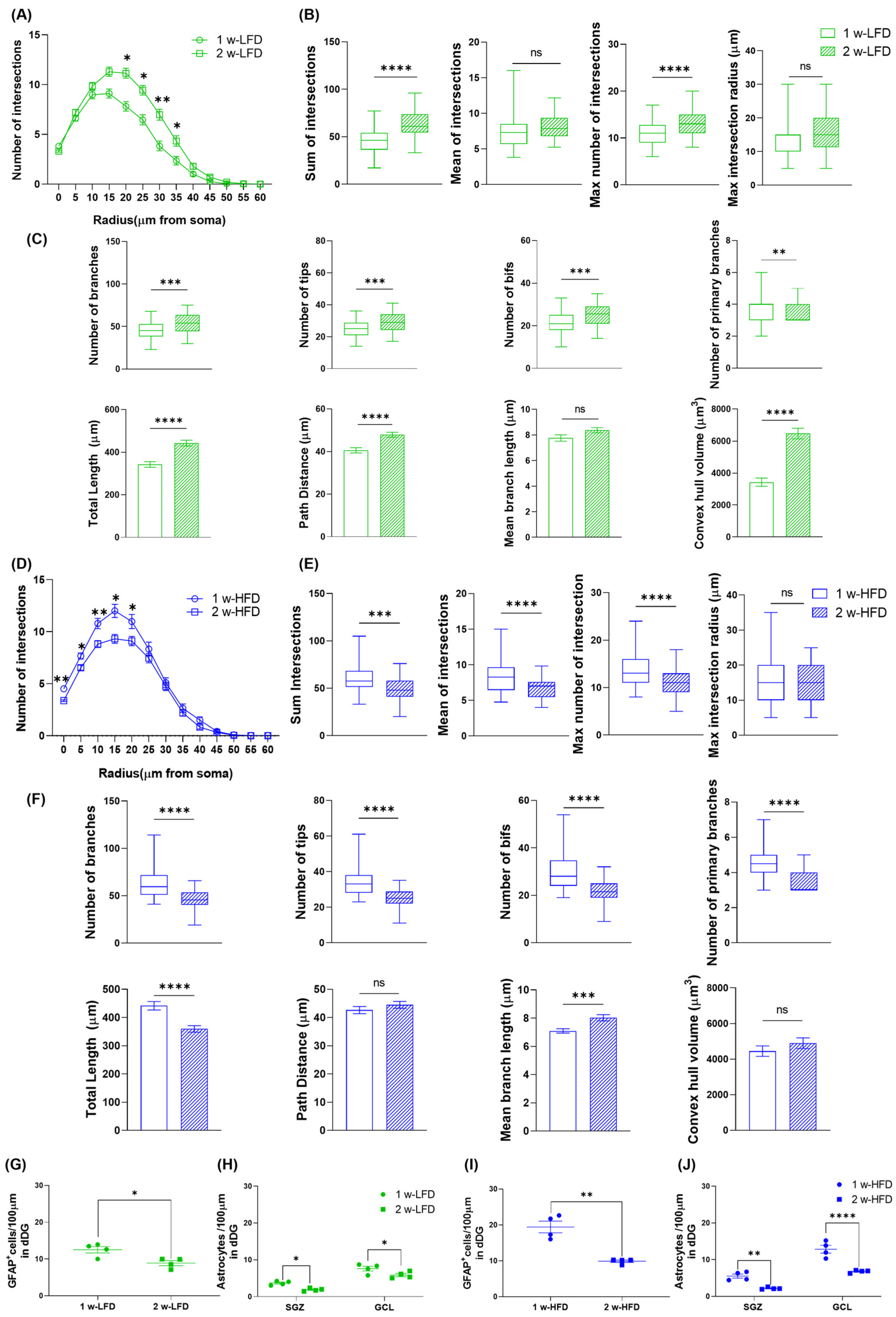

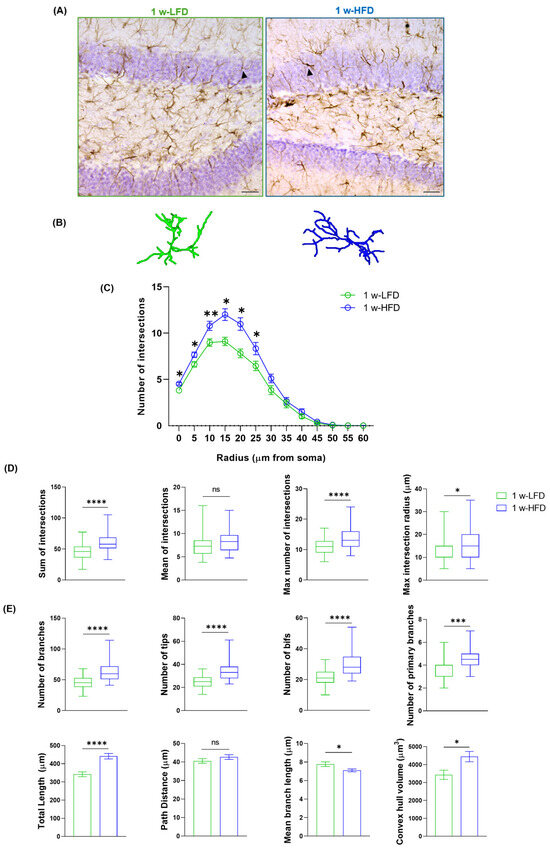

To evaluate astroglial alterations in the dorsal GCL, we performed a morphometric analysis on a three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction of astrocytes immunolabelled with GFAP in 1 w-LFD or 1 w-HFD fed mice (Figure 1A and Figure 2A,B). As shown by Sholl Intersection Profile (SIP) analysis (Figure 2C), we observed a significant increase in the number of intersections at 0–25 µm from soma in the 1 w-HFD as compared to the 1 w-LFD mice. The HFD-associated increase in GFAP+ cell complexity was also confirmed by quantification of the total, maximum number of intersections, and the maximum intersection radius (Figure 2D, Table 1). Conversely, 1 w-HFD did not impact the mean number of intersections (Figure 2D, Table 1). We also performed a quantitative analysis of additional morphological features of GFAP+ astrocytes in 1 w-HFD and 1 w-LFD experimental groups. Astrocytes from the 1 w-HFD group were characterized by a higher number of branches, terminal points, bifurcations, and primary branches compared with the 1 w-LFD mice group (Figure 2E, Table 1). Moreover, the total arborization length significantly increased after one week of HFD (Figure 2E, Table 1). In contrast, the average length of arborization branches decreased in the 1 w-HFD group compared to the 1 w-LFD group (Figure 2E, Table 1). Finally, 1 w-HFD did not impact path distance (Figure 2E, Table 1). We also evaluated whether the increased morphological complexity was accompanied by an expansion of the territory occupied by individual astroglial cells. In 1 w-HFD mice, compared to 1 w-LFD, astrocytes showed a significant expansion in their territory (Figure 2E, Table 1).

Figure 2.

One week of HFD increases astrocyte complexity in the dorsal GCL of adolescent mice. (A) Representative images of GFAP+ cells in the GCL of the dorsal hippocampus of mice fed with LFD or HFD for 1 week. Arrows indicate cells reconstructed in panel B. Scale bars= 30 µm. (B) Representative 3D morphological reconstruction of GFAP+ cells in the GCL of the dorsal hippocampus in 1 w-LFD and 1 w-HFD groups. (C) Sholl intersections profiles (SIP) of astrocytes in the GCL of the dorsal hippocampus (n = 4 animals each group). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 vs. 1 w-LFD. Nested t-test on a linear mixed-effect model, with animal as a random effect. (D) Summary of Sholl-related parameters and (E) morphometric features describing astrocyte structural morphology. Data are represented as Box and Wiskers and as mean ± SEM * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001, ns = not significant vs. 1 w-LFD. Student’s t-test.

Table 1.

Summary statistics of morphometric parameters for astrocytes within the granular cell layer (GCL) of the dorsal hippocampus in adolescent male mice fed with one week of low-fat diet (1 w-LFD) or high-fat diet (1 w-HFD).

Altogether, these data suggest that 1 week of exposure of adolescent mice to HFD is associated with morphological remodeling of dorsal GCL astrocytes, characterized by increased branching, structural complexity, and territory volume.

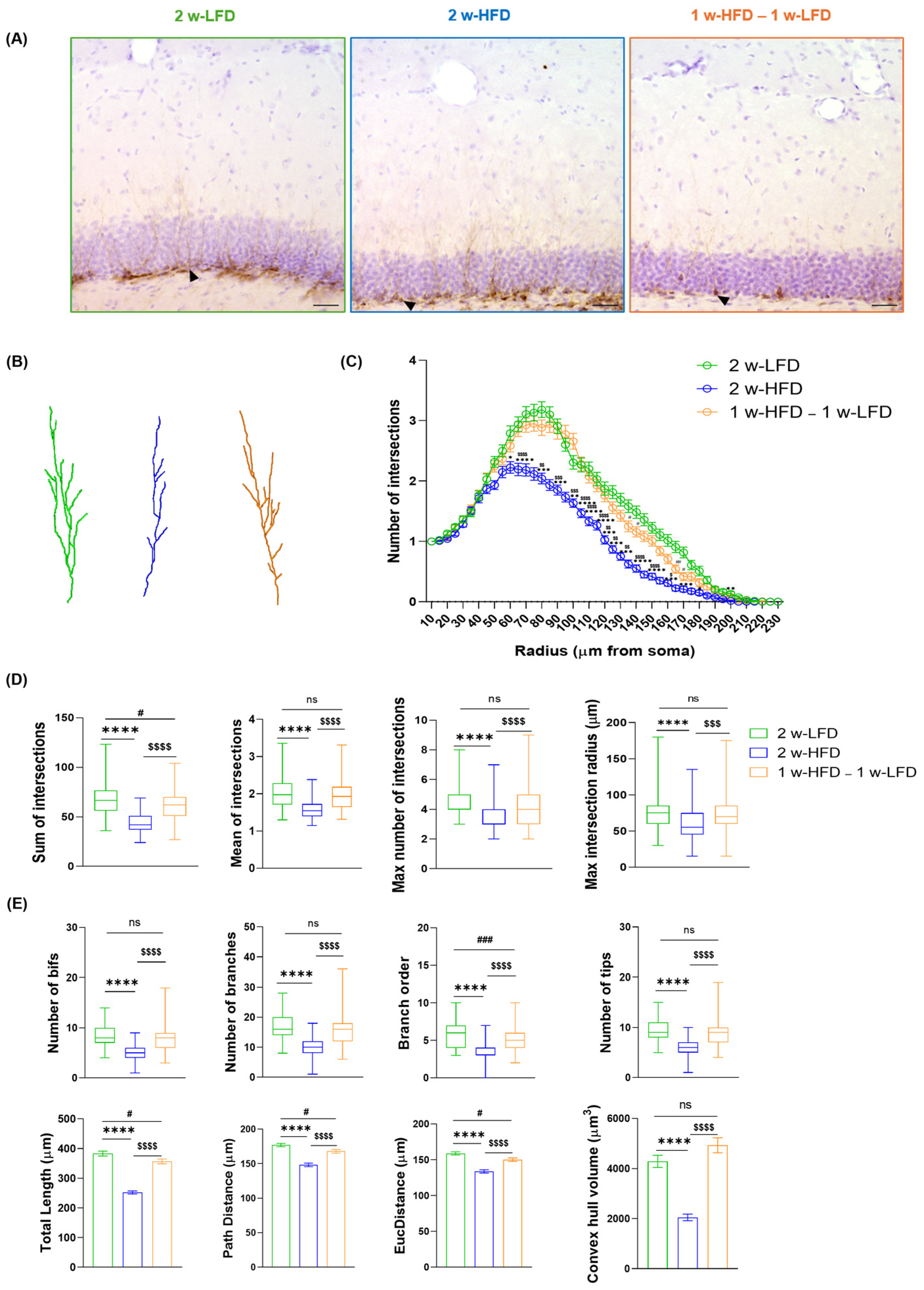

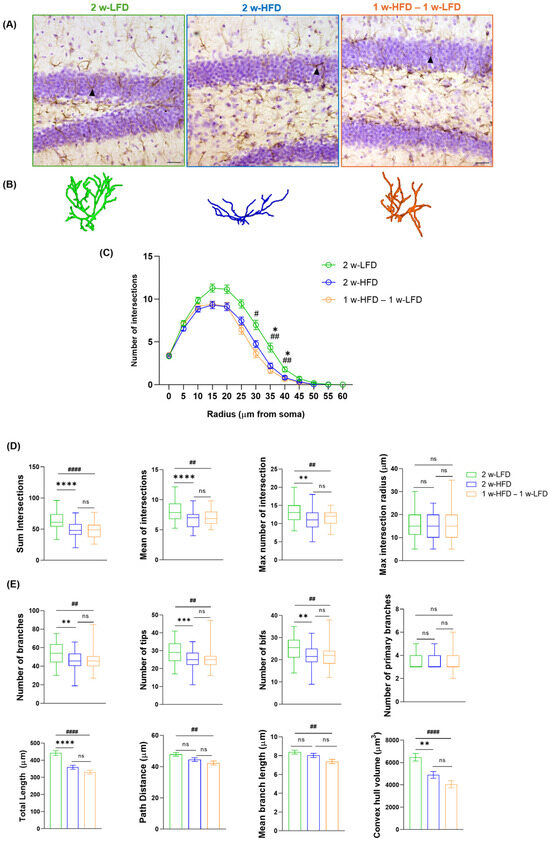

3.2. Two-Week-Long HFD Is Associated with Reduced Astrocyte Complexity and Territory Volume in the Dorsal GCL of Adolescent Mice

A second group of mice was exposed to two weeks of HFD (2 w-HFD group, n = 4) or LFD (2 w-LFD group, n = 4), as a control (Figure 1B). GFAP immunohistochemistry followed by 3D reconstruction and morphometric analysis of astrocytes in the dorsal GCL was performed (Figure 3A,B). 2 w-HFD led to a reduction in astrocyte complexity, with a significant difference observed between 35 and 40 µm from the soma, compared to the 2 w-LFD controls (Figure 3C). Specifically, in 2 w-HFD mice, the total number, mean, and maximum number of intersections were significantly reduced compared to 2 w-LFD mice (Figure 3D, Table 2), whereas the maximum intersection radius was not changed (Figure 3D, Table 2). Astrocytes from the 2 w-HFD group were also characterized by a lower number of branches, terminal points, and bifurcations compared with the 2 w-LFD group (Figure 3E, Table 2). No differences were observed in the number of primary branches between experimental groups (Figure 3E, Table 2). Moreover, the total arborization length and territory volume were significantly decreased in mice fed an HFD for 2 weeks, compared to those fed an LFD for the same period (Figure 3E, Table 2).

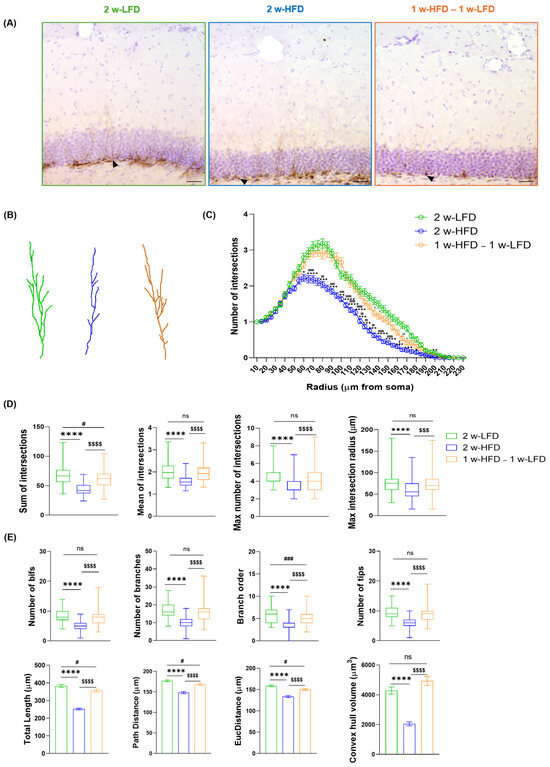

Figure 3.

Two-week-long HFD reduces astrocyte complexity in the dorsal GCL of adolescent mice. (A) Representative images of GFAP+ cells in the GCL of the dorsal hippocampus of 2 w-LFD, 2 w-HFD. 1 w-HFD–1 w-LFD groups. Arrows indicate cells reconstructed in panel B. Scale bars= 30 µm (B) Representative 3D morphological reconstruction of GFAP+ cells in the GCL of the dorsal hippocampus in 2 w-LFD, 2 w-HFD, and 1 w-HFD – 1 w-LFD groups. (C) SIP of astrocytes in the GCL of the dorsal hippocampus (n = 4 animals each group). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM * p < 0.05 2 w-LFD vs. 2 w-HFD; # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01 2 w-LFD vs. 1 w-HFD–1 w-LFD. Nested ANOVA on a linear mixed-effect model, with animal as a random effect. (D) Summary of Sholl-related parameters and (E) morphometric features describing astrocytes’ structural morphology. Data are represented as Box and Wiskers and as mean ± SEM ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001, 2 w-LFD vs. 2 w-HFD; ## p < 0.01, #### p < 0.0001, 2 w-LFD vs. 1 w-HFD–1 w-LFD; ns = not significant. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HDS test on a linear mixed-effect model.

Table 2.

Summary statistics of morphometric parameters for astrocytes within GCL of the dorsal hippocampus in adolescent male mice fed 2 w-LFD, 2 w-HFD, and 1 w-HFD – 1 w-LFD.

Within the same experimental design, an additional group of adolescent male mice was exposed to one week of HFD, followed by one week of LFD (1 w-HFD–1 w-LFD group, n = 4) (Figure 1B). When SIP was evaluated, no differences were found between 2 w-HFD and 1 w-HFD–1 w-LFD mice since both experimental groups showed a remarkable reduction in astrocyte complexity compared to 2 w-LFD mice (Figure 3C). Moreover, the 1 w-HFD – 1 w-LFD group showed no differences compared to the 2 w-HFD group in terms of Sholl-related parameters and morphological features (Figure 3D,E, Table 2). Only in mice from the 1 w-HFD–1 w-LFD group, path distance and average branch length showed a significant reduction compared to the 2 w-LFD mouse group (Figure 3E, Table 2). Furthermore, astrocyte territory volume was significantly reduced in 1 w-HFD–1 w-LFD compared to the 2 w-LFD control group (Figure 3E, Table 2).

Altogether, these findings indicate that 2 w-HFD exposure induces morphological changes in dorsal GCL astrocytes, marked by reduced branching, structural complexity, and territory volume. Furthermore, switching to a 1 w-LFD after 1 w-HFD produces similar morphological changes.

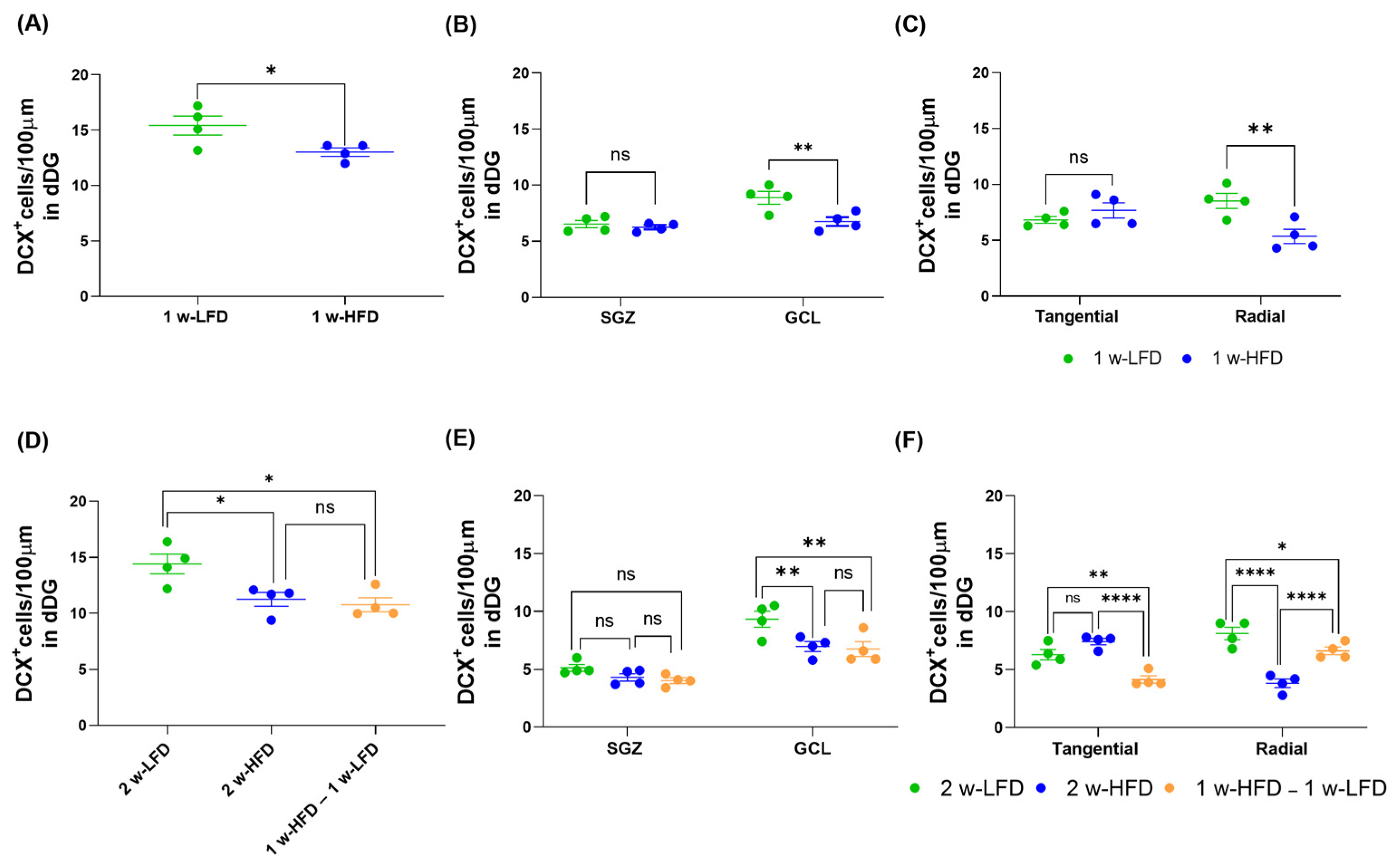

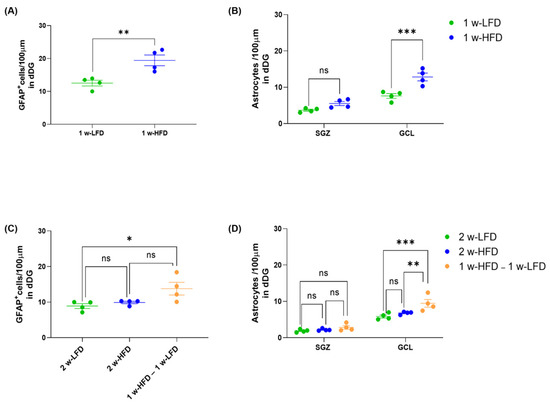

3.3. One Week-HFD, but Not Two-Week HFD, Increased Astrocyte Density in the Dorsal GCL of Adolescent Mice

The opposite effects of one vs. two-week HFD of dorsal GCL astrocyte morphological features prompted us to further dissect the effects of HFD on astrocytes by measuring the density of GFAP+ cells (number of cells/100 μm of dorsal DG length) in the suprapyramidal blade of DG. We found that the number of GFAP+ cells/100 μm was increased in 1 w-HFD mice when compared to 1 w-LFD mice (Figure 4A; 1 w-LFD: 12.52 ± 0.88, 1 w-HFD: 19.43; ** p < 0.01, Student’s t-test). Conversely, 2 w-HFD did not change GFAP+ cell density compared to its relative control group; however, in this experimental setting, a significant increase was detected in 1 w-HFD – 1 w-LFD group compared to 2 w-LFD (Figure 4C; 2 w-LFD: 8.88 ± 0.68, 2 w-HFD: 8.90 ± 0.35, 1 w-HFD–1 w-LFD: 13.77 ± 1.78; * p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s post hoc test). We also assessed astrocyte density in the two DG subregions, SGZ and GCL. In the first experiment, GFAP+ astrocytes density increased specifically in the GCL and not in the SGZ (Figure 4B; 1 w-LFD: 5.65 ± 1.97, 1 w-HFD: 9.18 ± 3.66; *** p < 0.001, Two-way ANOVA, Bonferroni’s post hoc test). In the second experimental setting, changes in the density of GFAP+ astrocytes in 2 w-HFD mice compared to 2 w-LFD mice were observed neither in SGZ nor in GCL, while a significant increase occurred in the 1 w-HFD–1 w-LFD group compared to both control groups in the GCL, but not in the SGZ (Figure 4D; 2 w-LFD: 3. 87 ± 1.99, 2 w-HFD: 4.50 ± 2.30, 1 w-HFD–1w-LFD: 6.14 ± 3.13; ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, Two-way ANOVA, Tukey’s post hoc test).

Figure 4.

One week of HFD, but not two weeks of HFD, increases astrocyte density only in the dorsal GCL of adolescent mice. (A) Number of GFAP+ cells/100 μm in the DG of the dorsal hippocampus. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. ** p < 0.01 vs. 1 w-LFD. Student’s t-test. (B) Number of astrocytes/100 μm in the SGZ and GCL of the dorsal DG. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM *** p < 0.001 vs. 1 w-LFD. Two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test. (C) Number of GFAP+ cells/100 μm in the GCL of the dorsal hippocampus. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05 vs. 2 w-LFD. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. (D) Number of astrocytes/100 μm in the SGZ and GCL of the dorsal hippocampus. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM *** p < 0.001 vs. 2 w-LFD, ** p < 0.01 vs. 2 w-HFD. ns= not significant. Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test (n = 4 mice each group).

Altogether, the data suggested even more complex changes in dorsal DG astrocytes of mice exposed to short periods of HFD. One-week HFD increased density, morphological complexity, and territory volume of GFAP+ astrocytes selectively in the dorsal GCL. Conversely, two weeks of HFD did not affect density but decreased the morphological complexity of GFAP+ astrocytes in the dorsal GCL compared to the relative control group. One week of HFD followed by LFD increased density and decreased morphological complexity of GFAP+ astrocytes in the dorsal GCL compared to both control groups.

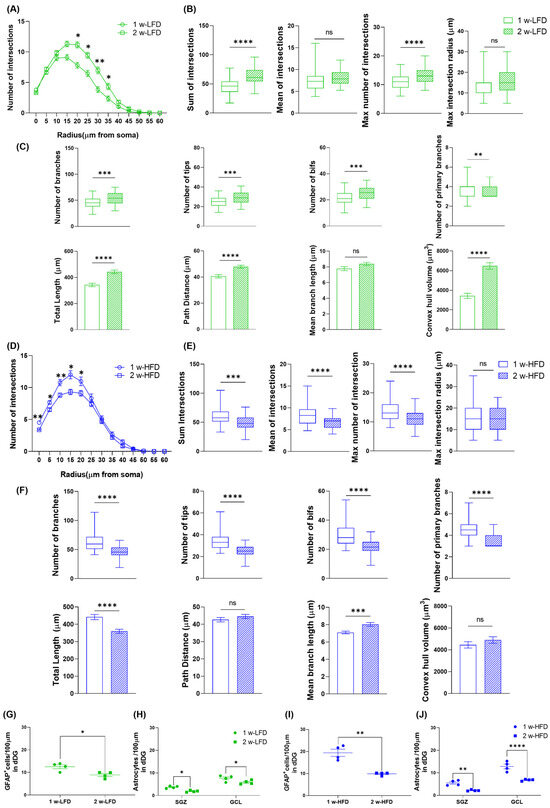

3.4. Comparison Between Mice Exposed to Either LFD or HFD at 6 and 7 Weeks of Age

Since in the two experimental settings mice had different ages at sacrifice (6 and 7 weeks), we also compared astrocyte morphological features between the two age groups. In LFD-fed mice, astrocyte complexity significantly increased from 6 to 7 weeks of age, as shown by a higher total number and maximum number of intersections, increased branching, terminal points, bifurcations, total arborization length, and path distance in Sholl analysis. Furthermore, astrocyte territory volume increased from 6 to 7 weeks of age (Figure 5A–C). In contrast, HFD-fed mice showed a marked reduction in astrocyte complexity between 6 and 7 weeks of age with decreases in SIP and morphometric parameters, including total intersections, branches, and arborization length, while average branch length increased (Figure 5D–F). However, the maximum intersection radius, path distance, and territory volume did not change with age.

Figure 5.

Comparison between mice exposed to either LFD or HFD at 6 and 7 weeks of age. (A) SIP of astrocytes in the GCL of the dorsal hippocampus of mice fed for 1 week and 2 weeks with LFD or (D) HFD (n = 4 mice each group). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 vs. 1 w-LFD or 1 w-HFD. Nested t-test on a linear mixed-effect model, with animal as a random effect. (B,E) Summary of Sholl-related parameters and (C,F) morphometric features describing astrocytes structural morphology. Data are represented as Box and Wiskers and as mean ± SEM ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001 vs. 1 w-LFD or 1 w-HFD. Student’s t-test. (G,I) Number of GFAP+ cells/100 μm in the GCL of the dorsal hippocampus. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 vs. 1 w-LFD or 1 w-HFD. Student’s t-test. (H,J) Number of astrocytes/100 μm in the SGZ and GCL of the dorsal DG of the hippocampus. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM * p < 0.05. ** p < 0.01, **** p < 0.0001 vs. 1 w-LFD or 1 w-HFD. ns = not significant. Two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc.

3.5. Short HFD Impairs DCX+ Cell Maturation in the Dorsal GCL of Adolescent Mice

Our previous work demonstrated that both 1-week and 2-week-long HFD in adolescent mice resulted in reduced complexity in the dendritic arborizations of newly born DCX+ immature neurons in the dorsal GCL [22]. DCX+ immature neurons represent one important cell population due to their role in learning and memory [43,44].

On the other hand, a larger and heterogeneous population of DCX+ cells is present in the hippocampus, since this marker is expressed not only by immature neurons but also by neuroblasts at different stages of maturation [45,46]. DCX+ cell maturation can be staged based on their soma location within the SGZ or GCL, the tangential vs. radial orientation of their processes, and the length of their dendritic arborizations, which reach the outer molecular layer (OML) in the immature neurons. Specifically, less mature neuroblasts have their soma in the SGZ with a tangential orientation and possess no or few processes; during maturation, they migrate to the GCL, acquire soma radial orientation, grow primary processes, which are also radially oriented in the GCL, and extend toward the ML [42]. We decided to better understand the impact of HFD not only on immature neurons but also on the different maturation stages of DCX+ cells within dorsal DG.

We evaluated DCX+ immature neurons via 3D reconstruction followed by Sholl analysis and additional morphometric parameters, confirming the negative impact of 2 w-HFD on immature neurons (Figure 6A–E, Table 3). Furthermore, we confirmed that HFD-associated reduction in immature neurons’ complexity was reversible in the 1 w-HFD – 1 w-LFD group (Figure 6A–E, Table 3).

Figure 6.

2 w-HFD negatively impacts immature neuron complexity in the dorsal hippocampus of adolescent mice. (A) Representative images of immature neurons in the DG of the dorsal hippocampus of 2 w-LFD, 2 w-HFD. 1 w-HFD – 1 w-LFD groups (n = 4 animals each group). Arrows indicate the 3D reconstruction shown in panel B. (B) Representative 3D morphological reconstruction of immature neurons in the DG of the dorsal hippocampus. Scale bars= 30 μm. (C) SIP of immature neurons in the DG of the dorsal hippocampus. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001 2 w-LFD vs. 2 w-HFD; # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01 2 w-LFD vs. 1 w-HFD–1 w-LFD; $ p < 0.05, $$ p < 0.01, $$$ p< 0.001, $$$$ p < 0.0001 2 w-HFD vs. 1 w-HFD–1 w-LFD. Nested ANOVA on a linear mixed-effect model, with animal as a random effect. (D) Summary of Sholl-related parameters and (E) morphometric features describing immature neurons’ structural morphology. Data are represented as Box and Wiskers and as mean ± SEM **** p < 0.0001 2 w-LFD vs. 2 w-HFD; # p < 0.05, ### p < 0.001 2 w-LFD vs. 1 w-HFD–1 w-LFD; $$$ p< 0.001, $$$$ p < 0.0001 2 w-HFD vs. 1 w-HFD–1 w-LFD. ns= not significant. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HDS test on linear mixed-effect model.

Table 3.

Summary statistics of morphometric parameters for immature neurons within the dentate gyrus (DG) of the dorsal hippocampus in adolescent male mice fed 2 w-LFD, 2 w-HFD, and 1 w-HFD–1 w-LFD.

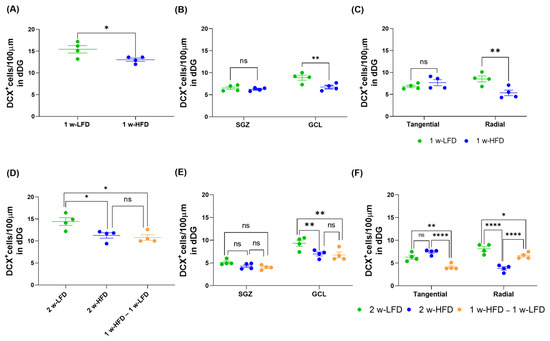

We also analyzed the density of DCX+ cells in the two different experimental settings. We found a significant reduction in the density of DCX+ cells in 1 w-HFD mice compared to 1 w-LFD (Figure 7A; 1 w-LFD: 15.43 ± 0.86, 1 w-HFD: 13.03 ± 0.38; * p < 0.05, Student’s t-test). Significant reductions were also observed in the 2 w-HFD and in 1 w-HFD – 1 w-LFD groups compared to the 2 w-LFD group (Figure 7D; 2 w-LFD: 14.40 ± 0.87, 2 w-HFD: 11.25 ± 0.63, 1 w-HFD–1 w-LFD: 10.77 ± 0.63; * p < 0.05, One-way ANOVA, Tukey’s post hoc test).

Figure 7.

1 w- and 2 w-HFD impair the maturation of DCX+ cells in the dorsal hippocampus of adolescence mice. (A) Number of DCX+ cells/100 μm in the DG of the dorsal hippocampus. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05 vs. 1 w-LFD Student’s t-test. (B) Number of DCX+ cells/100 μm in the SGZ and GCL of the dorsal hippocampus. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. ** p < 0.01 vs. 1 w-LFD. Two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test. (C) Number of tangential and radial DCX+ cells/100 μm in the DG of the dorsal hippocampus. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. ** p < 0.01 vs. 1 w-LFD. Two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test. (D) Number of DCX+ cells/100 μm in the DG of the dorsal hippocampus. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05, vs. 2 w-LFD. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. (E) Number of DCX+ cells/100 μm in the SGZ and GCL of the dorsal hippocampus. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. ** p < 0.01 vs. 2 w-LFD. Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. (F) Number of tangential and radial DCX+ cells/100 μm of the dorsal hippocampus. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, **** p < 0.0001 vs. 2 w-LFD or 2w-HFD. ns=not significant. Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test (n = 4 mice each group).

We subsequently evaluated the effect of HFD specifically on SGZ versus GCL location of DCX+ cells. In the first experimental setting, we observed a significant decrease in the density of DCX+ cells localized within the GCL, but not in the SGZ, where the most immature neuroblasts are located (Figure 7B; 1 w-LFD: 7.70 ± 1.18, 1 w-HFD: 6.50 ± 0.25; ** p < 0.01, Two-way ANOVA, Bonferroni’s post hoc test). In agreement with these data, the number of tangentially oriented DCX+ cells did not differ in the 1 w-HFD group compared to 1 w-LFD. A significant decrease was observed only in radially oriented DCX+ cells (Figure 7C; 1 w-LFD: 7.68 ± 0.85, 1 w-HFD: 6.50 ± 1.63; ** p < 0.01, two-way ANOVA, Bonferroni’s post hoc test). In the second experimental setting, a significant reduction in the density of DCX+ cells was observed again in the GCL, and not in the SGZ, of 2 w-HFD and 1 w-HFD–1 w-LFD groups compared to the 2 w-LFD group. (Figure 7E; 2 w-LFD: 7.23 ± 2.10, 2 w-HFD: 5.64 ± 1.34, 1 w-HFD–1 w-LFD: 5.39 ± 1.36; ** p < 0.01, two-way ANOVA, Tukey’s post hoc test). In agreement with these data, we observed no difference in the density of tangentially oriented DCX+ neuroblasts and a significant reduction in the density of radially oriented DCX+ cells in 2 w-HFD versus 2 w-LFD groups. To our surprise, the 1 w-HFD – 1 w-LFD group showed a significant decrease in the number of DCX+ cells with both tangential and radial orientation compared to the 2 w-LFD (Figure 7F; 2 w-LFD: 7.21 ± 0.91, 2 w-HFD: 5.63 ± 1.80, 1 w-HFD–1 w-LFD: 5.38 ± 1.23; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, **** p < 0.0001, Two-way ANOVA, Tukey’s post hoc test). Compared to the 2 w-HFD, the 1 w-HFD–1 w-LFD group exhibited a significant reduction in tangential DCX+ cells and a significantly increased number of radially oriented DCX+ cells (Figure 7F; **** p < 0.0001 Two-way ANOVA, Tukey’s post hoc test).

Altogether, our data suggest that both 1 w-HFD and 2 w-HFD not only reduce dendritic arborization complexity of immature neurons [22], but are also associated with a general reduction in the number of GCL DCX+ cells (including more mature neuroblasts and immature neurons) [37]. Moreover, HFD had no apparent effect on immature neuroblasts located in the SGZ. The negative effect of HFD on GCL DCX+ cells appears reversible since it is partially attenuated when 1 w-HFD is followed by return to LFD for a week.

4. Discussion

Diet-related lifestyle plays a pivotal role in the human CNS, modulating brain structure, neuroplasticity, and cognitive functions [4,47]. Clinical evidence indicates that even brief exposure to a Western diet is sufficient to impair hippocampal-dependent learning and memory in young people [9].

Our previous work demonstrated that a short period (1 w and 2 w) of HFD significantly reduces the morphological complexity of DCX+ immature neurons in the dorsal hippocampus of adolescent male mice, associated with a decrease in BDNF levels [22]. In the current paper, we extended our previous analysis and evaluated the impact of HFD in adolescent mice on dorsal hippocampus astrocytes, which are key regulators of brain homeostasis [48,49], and play a role in the functional integration of newborn neurons in preexisting circuits [25,27,28,29,30,31,50]. Furthermore, we analyzed in more detail the impact of HFD on DCX+ cells’ maturation stages in the dorsal hippocampus.

Literature data reported that chronic exposure to HFD increases astrocyte branching and amplifies their territorial domains in the hippocampi of adolescent rodents [51,52]. This enhanced complexity is believed to be associated with improved glutamate clearance and may be linked to alterations in hippocampal long-term potentiation (LTP) [53]. However, no data are currently available regarding the effects of short HFD exposure (1 or 2 weeks long) on astrocytes.

Herein, we demonstrated for the first time increased morphological complexity, territory volume, and density of astrocytes after 1 w-HFD feeding, suggesting an early adaptive response to changes in energy availability [54]. A limitation of our previous study [22], however, was its exclusive focus on DCX+ cell morphometry. It is well established that DCX expression marks cells at different stages of maturation, including neuroblasts and immature neurons [55,56], a maturing process that in rodents lasts about four weeks [45,46]. The maturation stage of DCX+ cells can be assessed based on established criteria [37,42,57], distinguishing neuroblasts, with tangential soma in the SGZ, from more mature stages, including neuroblasts and immature neurons, with radial soma orientation in the GCL and dendritic projections into the ML [42]. Our current and new data show that mice fed for one week with HFD have decreased density of DCX+ cells at a more advanced maturation stage in the GCL, but not in the SGZ, suggesting an impairment in later stages of the neurogenic process [42].

One week of HFD leads to an increase in astrocyte complexity and density and to a reduced maturation of DCX+ cells. Astrocytes modulate the differentiation and survival of neuroblasts and immature neurons [58], releasing molecules such as D-serine and glutamate that support neuronal maturation, survival, and integration within the neurogenic niche [58,59]. At present, since the descriptive nature of the data, we cannot propose any correlation between changes occurring in astrocytes and in DCX+ cells. Future studies in vivo and in vitro should address this aspect. If the two phenomena prove to be not just coincidental, it could be envisioned that short-term HFD primarily alters astrocyte morphology, which in turn may affect the maturation and integration of DCX+ cells in the dorsal GCL. Alternatively, HFD may impair DCX+ cell maturation, prompting astrocytes to adopt compensatory morphological changes in an attempt to maintain local homeostasis.

To understand if these phenomena were persistent with longer HFD administration (2 w-HFD) and if they were reversible by returning to a LFD, we performed a second experimental setting.

Surprisingly, we observed a marked reduction in astrocyte complexity and territory volume, without altering their density in the 2 w-HFD group compared with the 2 w-LFD fed group.

We questioned whether these changes could vary as a function of age, even under standard dietary conditions. We showed that there is a baseline difference in astrocyte morphological complexity and density between LFD groups at 6 and 7 weeks of age. After 2 w-LFD (7 weeks of age), the increase in astrocyte morphological complexity compared to 1 w-HFD suggests an age-related maturation of these cells in the adolescent GCL. In contrast, the reduction in astrocyte density may lead to an expansion of the territory volume occupied by each cell, indicating physiological remodeling of astrocytes during adolescence.

Regarding HFD-exposed mice, we highlighted a dramatic shift in astrocyte complexity and density between early and later stages of HFD exposure. One-week HFD increased astrocyte complexity (compared to 1w-LFD), showing a possible immediate response to metabolic stress, whereas prolonged (2 w-HFD) exposure impaired the maturation process and reduced cell density compared to 1 w-HFD.

Moreover, we were able to demonstrate that 2 w-HFD not only decreases the morphological complexity and density of the most advanced maturation stage of DCX+ cells, namely the immature neurons, but also reduces the number of DCX+ cells at intermediate maturation stages, which are more mature than neuroblasts but not yet fully immature neurons. Previous data suggested that an early acute HFD exposure in rodents can reduce DCX+ cells density in the dorsal hippocampus [16,51,60], potentially contributing to hippocampal-dependent impairments, such as in spatial and contextual memory [16,60,61]. Moreover, adolescent rodents exposed to a short HFD period exhibited impaired LTP in the hippocampus and deficits in long-term spatial memory, without affecting short-term memory [62]. Thus, our data suggests that impaired DCX+ cell maturation and reduced branching may limit the integration of immature neurons into existing neural networks, due to a reduced synaptic input.

We analyzed adolescent mice fed 1 w-HFD, followed by a return to 1 w-LFD. Astrocytic complexity in this group remained comparable to that of mice fed HFD for two weeks. However, astrocyte density in the dorsal GCL increased in the 1 w-HFD–1 w-LFD mice compared to the 2 w-HFD mice. Taken together, the data on morphology and density indicate that a short-term HFD alters astrocytes and that a brief return to LFD is not sufficient to recover their complexity, while still affecting their density.

Regarding DCX+ cells, 1 w-LFD after 1 w-HFD significantly reduces the density of neuroblasts and increases the number of DCX+ cells at advanced maturation stages compared to the 2 w-HFD mice. This indicates that a short HFD period may disrupt DCX+ cell maturation, whereas a return to LFD may promote recovery. Moreover, the restoration of DCX+ immature neuron complexity and the progression of DCX+ cells through maturation stages could be associated with an increased astrocyte density. This would suggest a possible disruption in the supportive astrocyte-neuron crosstalk, which may impair key processes such as synaptic plasticity and normal synaptogenesis [50,63,64,65].

One of the limitations of our data is that they are descriptive in nature and do not allow for the establishment of a causal link between astrocyte morphological alterations and DCX+ cell maturation impairment. Additionally, our analysis is only based on two time points, and it could be potentially interesting to evaluate the impact of HFD in adolescence at additional time points. More importantly, future experiments with a mechanistic in-depth analysis are required to disclose the functional alterations associated with astrocyte morphological changes and their potential causal relationship with DCX+ cell maturation in the dorsal hippocampus. Another limitation of our study is that it was conducted only in male mice. Males and females respond differently to HFD; as an example, indeed, early Western diet exposure impaired long-term memory in males but not females [66], whereas females showed reduced cell proliferation and fewer DCX+ cells [67].

In conclusion, herein we provide novel evidence that a short period of HFD during adolescence induces complex changes in GCL astrocytes and impairs the maturation of DCX+ cells in the GCL of the dorsal hippocampus. The correlation between the two events and the underlying mechanisms should be further investigated.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G.; analysis, G.D.C. and G.G.B.; data curation, G.D.C.; writing—original draft preparation, G.D.C., F.C. and M.G.; writing—review and editing, G.D.C., F.C., E.P., V.B. and M.G.; visualization, E.P. and V.B.; supervision and funding acquisition, M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was, in part, supported by MIUR Progetti di Ricerca di Rilevante Interesse Nazionale (PRIN) Bando 2017—grant 2017XZ7A37 to M.G.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Organismo Preposto al Benessere Animale (D.L. 26/2014; 2010/63/UE) of University of Piemonte Orientale, Novara, Italy (protocol code DB064.61 and date of approval 14 October 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HFD | High-Fat Diet |

| LFD | Low-Fat Diet |

| GFAP | Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein |

| DCX | Doublecortin |

| DG | Dentate Gyrus |

| GCL | Granular Cell Layer |

| SGZ | SubGranular Zone |

References

- Zaman, R.; Hankir, A.; Jemni, M. Lifestyle Factors and Mental Health. Psychiatr. Danub. 2019, 31, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Randolph, J.J.; Lacritz, L.H.; Colvin, M.K.; Espe-Pfeifer, P.; Carter, K.R.; Arnett, P.A.; Fox-Fuller, J.; Aduen, P.A.; Cullum, C.M.; Sperling, S.A. Integrating Lifestyle Factor Science into Neuropsychological Practice: A National Academy of Neuropsychology Education Paper. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. Off. J. Natl. Acad. Neuropsychol. 2024, 39, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazerani, P. The Neuroplastic Brain: Current Breakthroughs and Emerging Frontiers. Brain Res. 2025, 1858, 149643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augusto-Oliveira, M.; Verkhratsky, A. Lifestyle-Dependent Microglial Plasticity: Training the Brain Guardians. Biol. Direct 2021, 16, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittner, N.; Jockwitz, C.; Mühleisen, T.W.; Hoffstaedter, F.; Eickhoff, S.B.; Moebus, S.; Bayen, U.J.; Cichon, S.; Zilles, K.; Amunts, K.; et al. Combining Lifestyle Risks to Disentangle Brain Structure and Functional Connectivity Differences in Older Adults. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Santiago, J.A.; Bernstein, M.; Potashkin, J.A. Diet and Lifestyle Impact the Development and Progression of Alzheimer’s Dementia. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1213223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa-Wagner, A.; Dumitrascu, D.I.; Capitanescu, B.; Petcu, E.B.; Surugiu, R.; Fang, W.-H.; Dumbrava, D.-A. Dietary Habits, Lifestyle Factors and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Neural Regen. Res. 2020, 15, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordain, L.; Eaton, S.B.; Sebastian, A.; Mann, N.; Lindeberg, S.; Watkins, B.A.; O’Keefe, J.H.; Brand-Miller, J. Origins and Evolution of the Western Diet: Health Implications for the 21st Century. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 81, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attuquayefio, T.; Stevenson, R.J.; Oaten, M.J.; Francis, H.M. A Four-Day Western-Style Dietary Intervention Causes Reductions in Hippocampal-Dependent Learning and Memory and Interoceptive Sensitivity. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förster, L.-J.; Vogel, M.; Stein, R.; Hilbert, A.; Breinker, J.L.; Böttcher, M.; Kiess, W.; Poulain, T. Mental Health in Children and Adolescents with Overweight or Obesity. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, C.J.; Morton, J.B.; Reichelt, A.C. Adolescent Obesity and Dietary Decision Making—A Brain-Health Perspective. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, S.; Chen, E.Y. Examining Adolescence as a Sensitive Period for High-Fat, High-Sugar Diet Exposure: A Systematic Review of the Animal Literature. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennis, E.; Manza, P.; Volkow, N.D. Socioeconomic Status, BMI, and Brain Development in Children. Transl. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, X.; Yang, C.; Jia, X.; Yu, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhao, J.; Chen, Y.; Xie, B.; Zhuang, H.; Sun, C.; et al. High-Fat Diet Consumption Promotes Adolescent Neurobehavioral Abnormalities and Hippocampal Structural Alterations via Microglial Overactivation Accompanied by an Elevated Serum Free Fatty Acid Concentration. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2024, 119, 236–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Yang, C.; Wang, C.; Li, H.; Zhao, J.; Kang, X.; Liu, Z.; Chen, L.; Chen, X.; Pu, T.; et al. High-Fat Diet Consumption in Adolescence Induces Emotional Behavior Alterations and Hippocampal Neurogenesis Deficits Accompanied by Excessive Microglial Activation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinuesa, A.; Pomilio, C.; Menafra, M.; Bonaventura, M.M.; Garay, L.; Mercogliano, M.F.; Schillaci, R.; Lux Lantos, V.; Brites, F.; Beauquis, J.; et al. Juvenile Exposure to a High Fat Diet Promotes Behavioral and Limbic Alterations in the Absence of Obesity. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2016, 72, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Gao, C.-X.; Luo, F.-J.; Huang, Y.-T.; Gao, M.-M.; Long, Y.-S. Hippocampal Proteomic Changes in High-Fat Diet-Induced Obese Mice Associated with Memory Decline. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2024, 125, 109554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valladolid-Acebes, I.; Stucchi, P.; Cano, V.; Fernández-Alfonso, M.S.; Merino, B.; Gil-Ortega, M.; Fole, A.; Morales, L.; Ruiz-Gayo, M.; Del Olmo, N. High-Fat Diets Impair Spatial Learning in the Radial-Arm Maze in Mice. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2011, 95, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanselow, M.S.; Dong, H.-W. Are the Dorsal and Ventral Hippocampus Functionally Distinct Structures? Neuron 2010, 65, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheirbek, M.A.; Hen, R. Dorsal vs Ventral Hippocampal Neurogenesis: Implications for Cognition and Mood. Neuropsychopharmacology 2011, 36, 373–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Privitera, G.J.; Zavala, A.R.; Sanabria, F.; Sotak, K.L. High Fat Diet Intake during Pre and Periadolescence Impairs Learning of a Conditioned Place Preference in Adulthood. Behav. Brain Funct. 2011, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiazza, F.; Bondi, H.; Masante, I.; Ugazio, F.; Bortolotto, V.; Canonico, P.L.; Grilli, M. Short High Fat Diet Triggers Reversible and Region Specific Effects in DCX+ Hippocampal Immature Neurons of Adolescent Male Mice. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 21499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seri, B.; García-Verdugo, J.M.; McEwen, B.S.; Alvarez-Buylla, A. Astrocytes Give Rise to New Neurons in the Adult Mammalian Hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, 7153–7160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultan, S.; Li, L.; Moss, J.; Petrelli, F.; Cassé, F.; Gebara, E.; Lopatar, J.; Pfrieger, F.W.; Bezzi, P.; Bischofberger, J.; et al. Synaptic Integration of Adult-Born Hippocampal Neurons Is Locally Controlled by Astrocytes. Neuron 2015, 88, 957–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalmers, N.; Masouti, E.; Beckervordersandforth, R. Astrocytes in the Adult Dentate Gyrus—Balance between Adult and Developmental Tasks. Mol. Psychiatry 2024, 29, 982–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uguagliati, B.; Grilli, M. Astrocytic Alterations and Dysfunction in Down Syndrome: Focus on Neurogenesis, Synaptogenesis, and Neural Circuits Formation. Cells 2024, 13, 2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.A.; Hall, B.; Allsop, J.; Alqarni, R.; Allen, S.P. Lipid Metabolism in Astrocytic Structure and Function. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 112, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfrieger, F.W.; Ungerer, N. Cholesterol Metabolism in Neurons and Astrocytes. Prog. Lipid Res. 2011, 50, 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, G.; Volpi, L.; Pasquali, L.; Petrozzi, L.; Siciliano, G. Astrocyte–Neuron Interactions in Neurological Disorders. J. Biol. Phys. 2009, 35, 317–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allaman, I.; Bélanger, M.; Magistretti, P.J. Astrocyte–Neuron Metabolic Relationships: For Better and for Worse. Trends Neurosci. 2011, 34, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semyanov, A.; Verkhratsky, A. Astrocytic Processes: From Tripartite Synapses to the Active Milieu. Trends Neurosci. 2021, 44, 781–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellizzon, M.A.; Ricci, M.R. Choice of Laboratory Rodent Diet May Confound Data Interpretation and Reproducibility. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, nzaa031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellizzon, M.A.; Ricci, M.R. The Common Use of Improper Control Diets in Diet-Induced Metabolic Disease Research Confounds Data Interpretation: The Fiber Factor. Nutr. Metab. 2018, 15, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paxinos, G.; Franklin, K.B.J. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2001; Volume 296. [Google Scholar]

- Dellarole, A.; Grilli, M. Adult Dorsal Root Ganglia Sensory Neurons Express the Early Neuronal Fate Marker Doublecortin. J. Comp. Neurol. 2008, 511, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bondi, H.; Chiazza, F.; Masante, I.; Bortolotto, V.; Canonico, P.L.; Grilli, M. Heterogenous Response to Aging of Astrocytes in Murine Substantia Nigra Pars Compacta and Pars Reticulata. Neurobiol. Aging 2023, 123, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radic, T.; Al-Qaisi, O.; Jungenitz, T.; Beining, M.; Schwarzacher, S.W. Differential Structural Development of Adult-Born Septal Hippocampal Granule Cells in the Thy1-GFP Mouse, Nuclear Size as a New Index of Maturation. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0135493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Longair, M.H.; Baker, D.A.; Armstrong, J.D. Simple Neurite Tracer: Open Source Software for Reconstruction, Visualization and Analysis of Neuronal Processes. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2453–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scorcioni, R.; Polavaram, S.; Ascoli, G.A. L-Measure: A Web-Accessible Tool for the Analysis, Comparison and Search of Digital Reconstructions of Neuronal Morphologies. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 866–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, M.A.; Wei, Q.; Ascoli, G.A. Machine Learning Classification Reveals Robust Morphometric Biomarker of Glial and Neuronal Arbors. J. Neurosci. Res. 2023, 101, 112–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tassinari, M.; Uguagliati, B.; Trazzi, S.; Cerchier, C.B.; Cavina, O.V.; Mottolese, N.; Loi, M.; Candini, G.; Medici, G.; Ciani, E. Early-Onset Brain Alterations during Postnatal Development in a Mouse Model of CDKL5 Deficiency Disorder. Neurobiol. Dis. 2023, 182, 106146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encinas, J.M.; Vaahtokari, A.; Enikolopov, G. Fluoxetine Targets Early Progenitor Cells in the Adult Brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 8233–8238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terranova, J.I.; Ogawa, S.K.; Kitamura, T. Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis for Systems Consolidation of Memory. Behav. Brain Res. 2019, 372, 112035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, W.; Aimone, J.B.; Gage, F.H. New Neurons and New Memories: How Does Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis Affect Learning and Memory? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010, 11, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, M.S.; Shetty, A.K. Efficacy of Doublecortin as a Marker to Analyse the Absolute Number and Dendritic Growth of Newly Generated Neurons in the Adult Dentate Gyrus. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2004, 19, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plümpe, T.; Ehninger, D.; Steiner, B.; Klempin, F.; Jessberger, S.; Brandt, M.; Römer, B.; Rodriguez, G.R.; Kronenberg, G.; Kempermann, G. Variability of Doublecortin-Associated Dendrite Maturation in Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis Is Independent of the Regulation of Precursor Cell Proliferation. BMC Neurosci. 2006, 7, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, T.; Dias, G.P.; Thuret, S. Effects of Diet on Brain Plasticity in Animal and Human Studies: Mind the Gap. Neural Plast. 2014, 2014, 563160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkhratsky, A.; Ho, M.S.; Vardjan, N.; Zorec, R.; Parpura, V. General Pathophysiology of Astroglia. In Neuroglia in Neurodegenerative Diseases; Verkhratsky, A., Ho, M.S., Zorec, R., Parpura, V., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 149–179. ISBN 978-981-13-9913-8. [Google Scholar]

- Verkhratsky, A.; Nedergaard, M. Physiology of Astroglia. Physiol. Rev. 2018, 98, 239–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augusto-Oliveira, M.; Arrifano, G.P.; Takeda, P.Y.; Lopes-Araújo, A.; Santos-Sacramento, L.; Anthony, D.C.; Verkhratsky, A.; Crespo-Lopez, M.E. Astroglia-Specific Contributions to the Regulation of Synapses, Cognition and Behaviour. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020, 118, 331–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, B.; Brás, A.R.; Araújo-Andrade, L.; Silva, A.; Pereira, P.A.; Madeira, M.D.; Cardoso, A. High-Caloric Diets in Adolescence Impair Specific GABAergic Subpopulations, Neurogenesis, and Alter Astrocyte Morphology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, A.; Brazhe, N.; Fedotova, A.; Tiaglik, A.; Bychkov, M.; Morozova, K.; Brazhe, A.; Aronov, D.; Lyukmanova, E.; Lazareva, N.; et al. A High-Fat Diet Changes Astrocytic Metabolism to Promote Synaptic Plasticity and Behavior. Acta Physiol. Oxf. Engl. 2022, 236, e13847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongin, A.A. Astrocytes on “Cholesteroids”: The Size- and Function-Promoting Effects of a High-Fat Diet on Hippocampal Astroglia. Acta Physiol. 2022, 236, e13859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckman, L.B.; Thompson, M.M.; Lippert, R.N.; Blackwell, T.S.; Yull, F.E.; Ellacott, K.L.J. Evidence for a Novel Functional Role of Astrocytes in the Acute Homeostatic Response to High-Fat Diet Intake in Mice. Mol. Metab. 2015, 4, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gleeson, J.G.; Lin, P.T.; Flanagan, L.A.; Walsh, C.A. Doublecortin Is a Microtubule-Associated Protein and Is Expressed Widely by Migrating Neurons. Neuron 1999, 23, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couillard-Despres, S.; Winner, B.; Schaubeck, S.; Aigner, R.; Vroemen, M.; Weidner, N.; Bogdahn, U.; Winkler, J.; Kuhn, H.-G.; Aigner, L. Doublecortin Expression Levels in Adult Brain Reflect Neurogenesis. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2005, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungenitz, T.; Radic, T.; Jedlicka, P.; Schwarzacher, S.W. High-Frequency Stimulation Induces Gradual Immediate Early Gene Expression in Maturing Adult-Generated Hippocampal Granule Cells. Cereb. Cortex 2014, 24, 1845–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassé, F.; Richetin, K.; Toni, N. Astrocytes’ Contribution to Adult Neurogenesis in Physiology and Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spampinato, S.F.; Bortolotto, V.; Canonico, P.L.; Sortino, M.A.; Grilli, M. Astrocyte-Derived Paracrine Signals: Relevance for Neurogenic Niche Regulation and Blood–Brain Barrier Integrity. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boitard, C.; Etchamendy, N.; Sauvant, J.; Aubert, A.; Tronel, S.; Marighetto, A.; Layé, S.; Ferreira, G. Juvenile, but Not Adult Exposure to High-Fat Diet Impairs Relational Memory and Hippocampal Neurogenesis in Mice. Hippocampus 2012, 22, 2095–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boitard, C.; Cavaroc, A.; Sauvant, J.; Aubert, A.; Castanon, N.; Layé, S.; Ferreira, G. Impairment of Hippocampal-Dependent Memory Induced by Juvenile High-Fat Diet Intake Is Associated with Enhanced Hippocampal Inflammation in Rats. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2014, 40, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazen, T.; Hatoum, O.A.; Ferreira, G.; Maroun, M. Acute Exposure to a High-Fat Diet in Juvenile Male Rats Disrupts Hippocampal-Dependent Memory and Plasticity through Glucocorticoids. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Liu, H.; Dai, Z.; He, C.; Qin, S.; Su, Z. From Physiology to Pathology of Astrocytes: Highlighting Their Potential as Therapeutic Targets for CNS Injury. Neurosci. Bull. 2025, 41, 131–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Long, C.; Peng, X.; Tao, J.; Pu, Y.; Yue, R. Bridging Metabolic Syndrome and Cognitive Dysfunction: Role of Astrocytes. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1393253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkhratsky, A.; Butt, A.; Li, B.; Illes, P.; Zorec, R.; Semyanov, A.; Tang, Y.; Sofroniew, M.V. Astrocytes in Human Central Nervous System Diseases: A Frontier for New Therapies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, L.-L.; Wang, C.-H.; Li, T.-L.; Chang, S.-D.; Lin, L.-C.; Chen, C.-P.; Chen, C.-T.; Liang, K.-C.; Ho, I.-K.; Yang, W.-S.; et al. Sex Differences in High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity, Metabolic Alterations and Learning, and Synaptic Plasticity Deficits in Mice. Obesity 2010, 18, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robison, L.S.; Albert, N.M.; Camargo, L.A.; Anderson, B.M.; Salinero, A.E.; Riccio, D.A.; Abi-Ghanem, C.; Gannon, O.J.; Zuloaga, K.L. High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity Causes Sex-Specific Deficits in Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis in Mice. eNeuro 2020, 7, ENEURO.0391-19.2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.