The Double Face of Microglia in the Brain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Microglia: “The Cells of Pío Del Río-Hortega”

3. Microglial Activation and Functional Polarization

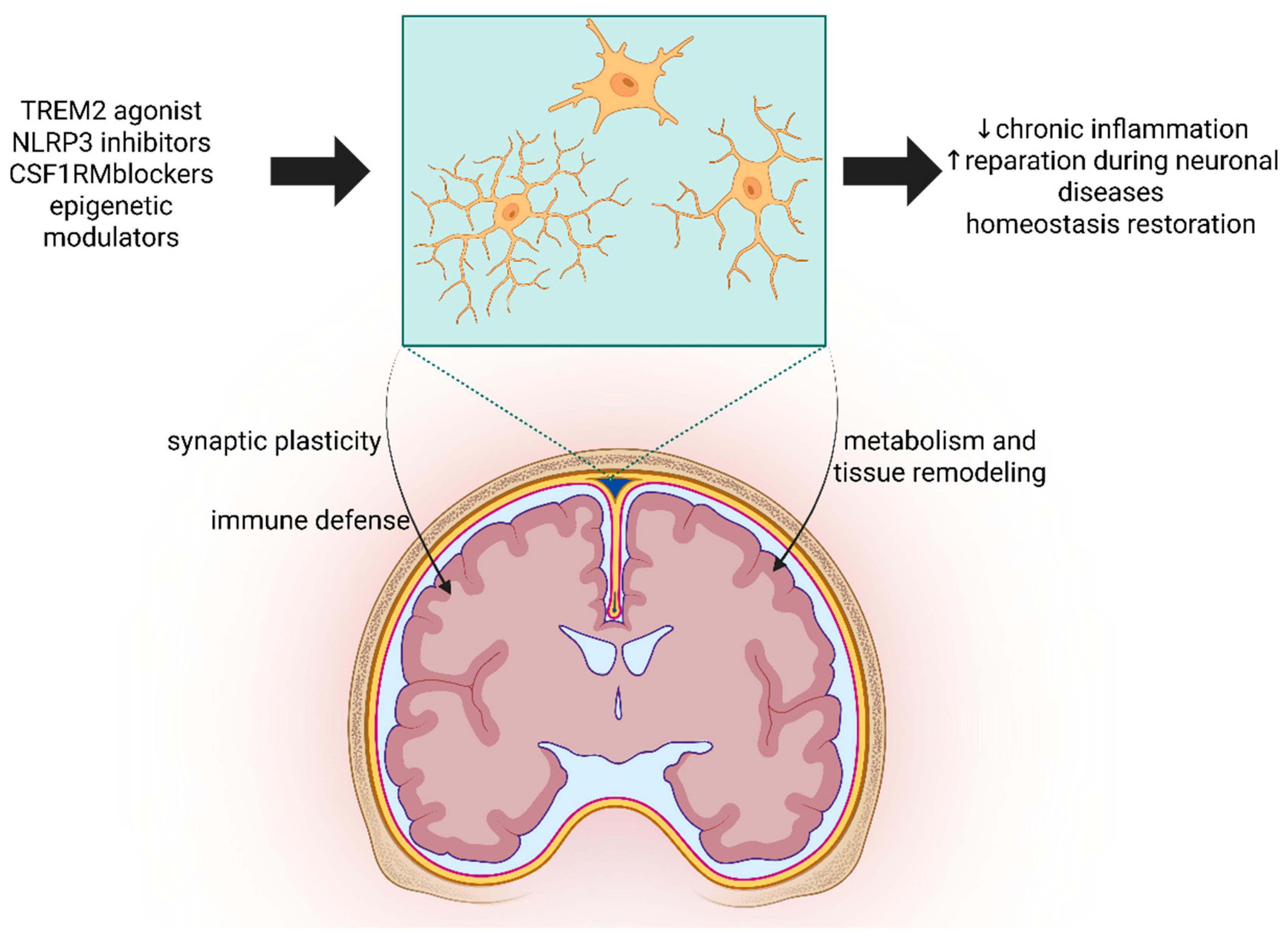

4. Neuroimmune Integration and Microglial Modulation: Therapeutic Strategies

5. Microglia Metabolic Modulation by Bioactive Natural Compounds

6. Aging, Metabolism, and Oxidative Vulnerability

7. Epigenetic and Transcriptional Control of Microglial Identity

8. Microglia and Neuroglial Communication

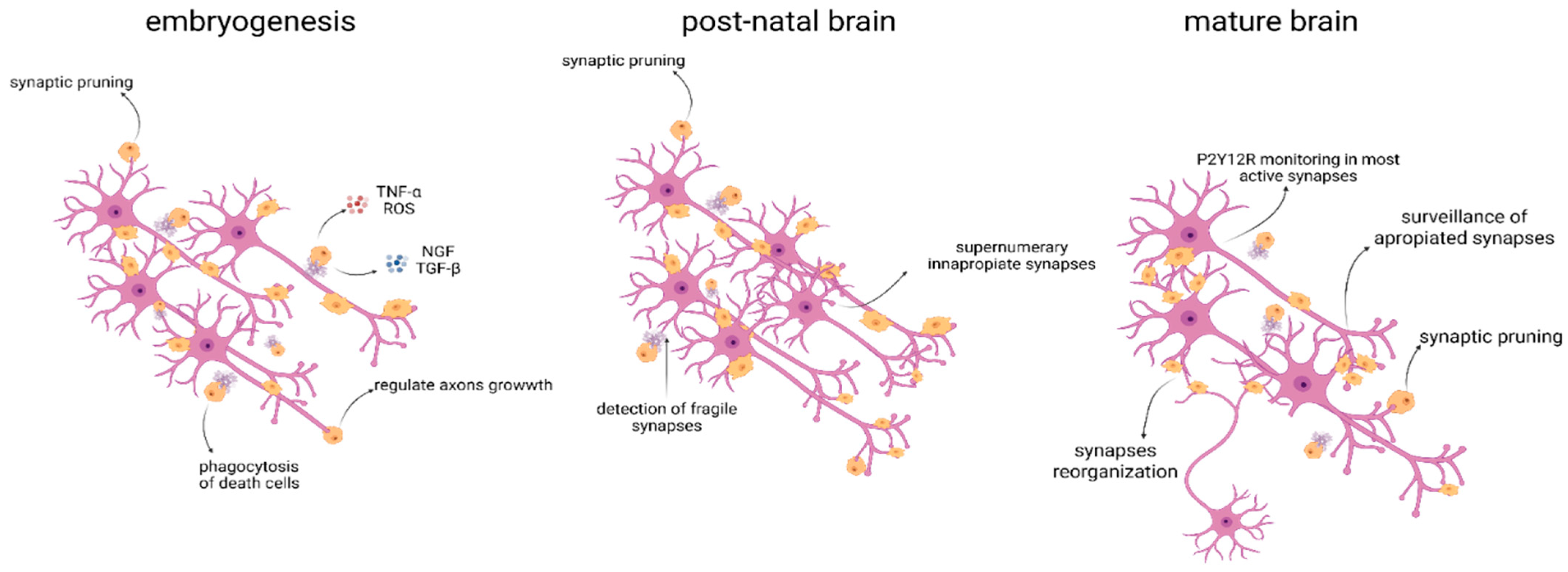

9. Microglia in Development, Synaptic Plasticity, and Apoptosis

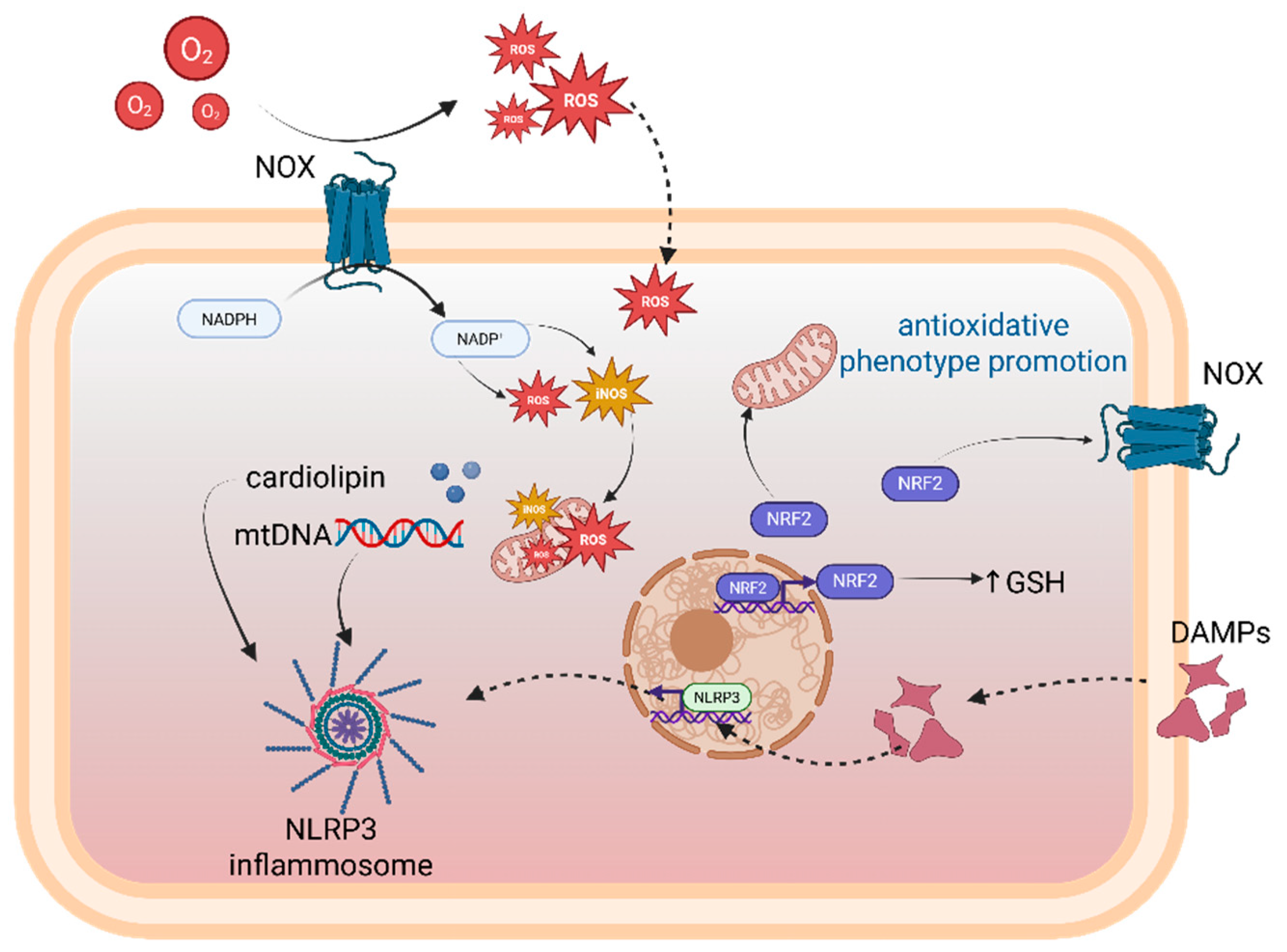

10. Microglia, Redox Homeostasis, and Mitochondrial Communication

11. Neuroimmune Integration and Therapeutic Perspectives

12. Insights from Microglia Knockout Models in Neurodegeneration

13. Conclusions

14. Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boullerne, A.I.; Feinstein, D.L. History of Neuroscience I. Pío del Río-Hortega (1882–1945): The Discoverer of Microglia and Oligodendroglia. ASN Neuro 2020, 12, 1759091420953259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schafer, D.P.; Stevens, B. Microglia Function in Central Nervous System Development and Plasticity. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2015, 7, a020545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, R.K.; Zhang, L.; Molina-Gonzalez, I.; Ton, K.; Nicoll, J.A.R.; Boardman, J.P.; Liang, Y.; Williams, A.; Miron, V.E. Localized microglia dysregulation impairs central nervous system myelination in development. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2023, 11, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, J.; Jiang, X.; Leak, R.K.; Shi, Y.; Hu, X.; Chen, J. Microglial Responses to Brain Injury and Disease: Functional Diversity and New Opportunities. Transl. Stroke Res. 2021, 12, 474–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Gutierrez, R.A.; Bhat, M.A. Microglia, Trem2, and Neurodegeneration. Neuroscientist 2025, 31, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marín-Teva, J.L.; Sepúlveda, M.R.; Neubrand, V.E.; Cuadros, M.A. Microglial Phagocytosis During Embryonic and Postnatal Development. Adv. Neurobiol. 2024, 37, 151–161. [Google Scholar]

- Navabi, S.P.; Badreh, F.; Khombi Shooshtari, M.; Hajipour, S.; Moradi Vastegani, S.; Khoshnam, S.E. Microglia-induced neuroinflammation in hippocampal neurogenesis following traumatic brain injury. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiens, K.R.; Wasti, N.; Ulloa, O.O.; Klegeris, A. Diversity of Microglia-Derived Molecules with Neurotrophic Properties That Support Neurons in the Central Nervous System and Other Tissues. Molecules 2024, 29, 5525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zou, C. Microglial Dysfunction in Neurodegenerative Diseases via RIPK1 and ROS. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devanney, N.A.; Stewart, A.N.; Gensel, J.C. Microglia and macrophage metabolism in CNS injury and disease: The role of immunometabolism in neurodegeneration and neurotrauma. Exp. Neurol. 2020, 329, 113310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, M.; Lin, S.; Li, S.; Du, Y.; Zhao, H.; Hong, H.; Yang, M.; Yang, X.; Wu, Y.; Ren, L.; et al. TIR-Domain-Containing Adapter-Inducing Interferon-β (TRIF) Is Essential for MPTP-Induced Dopaminergic Neuroprotection via Microglial Cell M1/M2 Modulation. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2017, 11, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Wang, H.; Yin, Y. Microglia Polarization from M1 to M2 in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 815347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaik, S.M.; Cao, Y.; Gogola, J.V.; Dodiya, H.B.; Zhang, X.; Boutej, H.; Han, W.; Kriz, J.; Sisodia, S.S. Translational profiling identifies sex-specific metabolic and epigenetic reprogramming of cortical microglia/macrophages in APPPS1-21 mice with an antibiotic-perturbed-microbiome. Mol. Neurodegener. 2023, 18, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orihuela, R.; McPherson, C.A.; Harry, G.J. Microglial M1/M2 polarization and metabolic states. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 173, 649–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Son, Y. Astrocytes Stimulate Microglial Proliferation and M2 Polarization In Vitro through Crosstalk between Astrocytes and Microglia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldman, D.H.; Dykstra, T.; Smirnov, I.; Blackburn, S.M.; Da Mesquita, S.; Kipnis, J.; Herz, J. Age-associated suppression of exploratory activity during sickness is linked to meningeal lymphatic dysfunction and microglia activation. Nat. Aging 2022, 2, 704–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaraj, K.; Kumar, R.; Shyamasundar, S.; Arumugam, T.V.; Polepalli, J.S.; Dheen, S.T. Spatial Transcriptomic Analysis Reveals HDAC Inhibition Modulates Microglial Dynamics to Protect Against Ischemic Stroke in Mice. Glia 2025, 73, 1817–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirakis, N.; Dimothyra, S.; Karadima, E.; Alexaki, V.I. Metabolic regulation of immune memory and function of microglia. Elife 2025, 14, e107552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginhoux, F.; Prinz, M. Origin of microglia: Current concepts and past controversies. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2015, 1, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, T.; Sankowski, R.; Staszewski, O.; Prinz, M. Microglia Heterogeneity in the Single-Cell Era. Cell Rep. 2020, 30, 1271–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paolicelli, R.C.; Bolasco, G.; Pagani, F.; Maggi, L.; Scianni, M.; Panzanelli, P.; Giustetto, M.; Ferreira, T.A.; Guiducci, E.; Dumas, L.; et al. Synaptic pruning by microglia is necessary for normal brain development. Science 2011, 333, 1456–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colonna, M.; Butovsky, O. Microglia function in the central nervous system during health and neurodegeneration. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 35, 441–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salter, M.W.; Stevens, B. Microglia emerge as central players in brain disease. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 1018–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Barres, B.A. Microglia and macrophages in brain homeostasis and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 18, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ransohoff, R.M. How neuroinflammation contributes to neurodegeneration. Science 2016, 353, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, T.R.; Dufort, C.; Dissing-Olesen, L.; Giera, S.; Young, A.; Wysoker, A.; Walker, A.J.; Gergits, F.; Segel, M.; Nemesh, J.; et al. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing of Microglia throughout the Mouse Lifespan and in the Injured Brain Reveals Complex Cell-State Changes. Immunity 2019, 50, 253–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, T.; Sankowski, R.; Staszewski, O.; Böttcher, C.; Amann, L.; Sagar-Scheiwe, C.; Nessler, S.; Kunz, P.; van Loo, G.; Coenen, V.A.; et al. Spatial and temporal heterogeneity of mouse and human microglia at single-cell resolution. Nature 2019, 566, 388–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, K.A.; Van Enoo, A.A.; Ikezu, T. Alzheimer’s Disease: The Role of Microglia in Brain Homeostasis and Proteopathy. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, L.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Li, Y.; Sun, L.; Zhou, Y.; Qian, G.; Zheng, J.C. IL-1β and TNF-α induce neurotoxicity through glutamate production: A potential role for neuronal glutaminase. J. Neurochem. 2013, 125, 897–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartra, C.; Vuraić, K.; Yuan, Y.; Codony, S.; Valdés-Quiroz, H.; Casal, C.; Slevin, M.; Máquez-Kisinousky, L.; Planas, A.M.; Griñán-Ferré, C.; et al. Microglial pro-inflammatory mechanisms induced by monomeric C-reactive protein are counteracted by soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibitors. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2025, 155, 114644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keren-Shaul, H.; Spinrad, A.; Weiner, A.; Matcovitch-Natan, O.; Dvir-Szternfeld, R.; Ulland, T.K.; David, E.; Baruch, K.; Lara-Astaiso, D.; Toth, B.; et al. A Unique Microglia Type Associated with Restricting Development of Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell 2017, 169, 1276–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleland, N.R.W.; Potter, G.J.; Buck, C.; Quang, D.; Oldham, D.; Neal, M.; Saviola, A.; Niemeyer, C.S.; Dobrinskikh, E.; Bruce, K.D. Altered metabolism and DAM-signatures in female brains and microglia with aging. Brain Res. 2024, 1829, 148772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, T.; Prinz, M. Microglia across evolution: From conserved origins to functional divergence. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2025, 22, 1533–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, S.R.; Federoff, H.J. Targeting Microglial Activation States as a Therapeutic Avenue in Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2017, 9, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Liu, S.; Han, J.; Li, S.; Gao, X.; Wang, M.; Zhu, J.; Jin, T. Role of Toll-Like Receptors in Neuroimmune Diseases: Therapeutic Targets and Problems. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 777606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.; Han, K.; Wang, Y.; Qu, R.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; An, Z.; Li, J.; Wu, H.; et al. Microglial Activation and Oxidative Stress in PM2.5-Induced Neurodegenerative Disorders. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lull, M.E.; Block, M.L. Microglial activation and chronic neurodegeneration. Neurotherapeutics 2010, 7, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Shui, X.; Sun, R.; Wan, L.; Zhang, B.; Xiao, B.; Luo, Z. Microglial Phenotypic Transition: Signaling Pathways and Influencing Modulators Involved in Regulation in Central Nervous System Diseases. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2021, 15, 736310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Han, B.; Hai, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Yang, J.; Sun, D.; Yin, P. The Role of Microglia/Macrophages Activation and TLR4/NF-κB/MAPK Pathway in Distraction Spinal Cord Injury-Induced Inflammation. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2022, 16, 926453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederiksen, H.R.; Haukedal, H.; Freude, K. Cell Type Specific Expression of Toll-Like Receptors in Human Brains and Implications in Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomed. Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 7420189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Jiang, J.; Tan, Y.; Chen, S. Microglia in neurodegenerative diseases: Mechanism and potential therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2023, 8, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordão, M.J.C.; Sankowski, R.; Brendecke, S.M.; Sagar; Locatelli, G.; Tai, Y.-H.; Tay, T.L.; Schramm, E.; Armbruster, S.; Hagemeyer, N.; et al. Single-cell profiling identifies myeloid cell subsets with distinct fates during neuroinflammation. Science 2019, 363, eaat7554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathys, H.; Adaikkan, C.; Gao, F.; Young, J.Z.; Manet, E.; Hemberg, M.; De Jager, P.L.; Ransohoff, R.M.; Regev, A.; Tsai, L.-H. Temporal Tracking of Microglia Activation in Neurodegeneration at Single-Cell Resolution. Cell Rep. 2017, 21, 366–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, T.E.; Lewis, C.V.; Zhu, M.; Wang, C.; Samuel, C.S.; Drummond, G.R.; Kemp-Harper, B.K. IL-4 and IL-13 induce equivalent expression of traditional M2 markers and modulation of reactive oxygen species in human macrophages. Sci Rep. 2023, 13, 19589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, B.A.; Srinivasan, K.; Ayalon, G.; Meilandt, W.J.; Lin, H.; Huntley, M.A.; Cao, Y.; Lee, S.-H.; Haddick, P.C.; Ngu, H.; et al. Diverse Brain Myeloid Expression Profiles Reveal Distinct Microglial Activation States and Aspects of Alzheimer’s Disease Not Evident in Mouse Models. Cell Rep. 2018, 22, 832–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streit, W.J.; Khoshbouei, H.; Bechmann, I. Dystrophic microglia in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Glia 2020, 68, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safaiyan, S.; Besson-Girard, S.; Kaya, T.; Cantuti-Castelvetri, L.; Liu, L.; Ji, H.; Schifferer, M.; Gouna, G.; Usifo, F.; Kannaiyan, N. White matter aging drives microglial diversity. Neuron 2021, 109, 1100–1117.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Dong, Y.; Li, M.; Liu, H.; Yan, C.; Li, X.; Gu, Y.; Wang, L.; Xu, C.; Xu, J.; et al. Targeting microglia polarization with Chinese herb-derived natural compounds for neuroprotection in ischemic stroke. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 13, 1580479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek-Szukala, K.; Markiewicz, M.; Walczewska, A.; Zgorzynska, E. Docosahexaenoic Acid (DHA) Reduces LPS-Induced Inflammatory Response Via ATF3 Transcription Factor and Stimulates Src/Syk Signaling-Dependent Phagocytosis in Microglia. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 57, 411–425. [Google Scholar]

- Jara, C.; Torres, A.K.; Park-Kang, H.S.; Sandoval, L.; Retamal, C.; Gonzalez, A.; Ricca, M.; Valenzuela, S.; Murphy, M.P.; Inestrosa, N.C.; et al. Curcumin Improves Hippocampal Cell Bioenergetics, Redox and Inflammatory Markers, and Synaptic Proteins, Regulating Mitochondrial Calcium Homeostasis. Neurotox Res. 2025, 43, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Wang, K.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, T.; Zhan, K.; Zhao, G. Quercetin Alleviates Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Cell Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Responses via Regulation of the TLR4-NF-κB Signaling Pathway in Bovine Rumen Epithelial Cells. Toxins 2023, 15, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bissacotti, B.F.; da Silveira, M.V.; Assmann, C.E.; Copetti, P.M.; Santos, A.F.D.; Fagan, S.B.; da Rocha, J.A.P.; Schetinger, M.R.C.; Morsch, V.M.M.; Bottari, N.B.; et al. Resveratrol Alleviates Inflammatory Response Through P2X7/NLRP3 Signaling Pathway: In Silico and In Vitro Evidence from Activated Microglia. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inchingolo, A.D.; Inchingolo, A.M.; Malcangi, G.; Avantario, P.; Azzollini, D.; Buongiorno, S.; Viapiano, F.; Campanelli, M.; Ciocia, A.M.; De Leonardis, N.; et al. Effects of Resveratrol, Curcumin and Quercetin Supplementation on Bone Metabolism—A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Liu, M.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Song, C. ω-3 DPA Protected Neurons from Neuroinflammation by Balancing Microglia M1/M2 Polarizations through Inhibiting NF-κB/MAPK p38 Signaling and Activating Neuron-BDNF-PI3K/AKT Pathways. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Fu, S.; Wen, J.; Yan, A.; Yang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, D.; He, D. Orally Administered Ginkgolide C Alleviates MPTP-Induced Neurodegeneration by Suppressing Neuroinflammation and Oxidative Stress through Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis in Mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 22115–22131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Han, L.; Zhang, W.; Wang, D.; Huo, D.; Tan, X.; Su, X.; Wang, M.; Xu, J.; Cheng, J.; et al. Neuroprotective mechanisms of valproic acid and alpha-lipoic acid in ALS: A network pharmacology-based investigation. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1681929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trépanier, M.O.; Hopperton, K.E.; Orr, S.K.; Bazinet, R.P. N-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in animal models with neuroinflammation: An update. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 785, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javed, H.; Meeran, M.F.N.; Azimullah, S.; Bader Eddin, L.; Dwivedi, V.D.; Jha, N.K.; Ojha, S. α-Bisabolol, a Dietary Bioactive Phytochemical Attenuates Dopaminergic Neurodegeneration through Modulation of Oxidative Stress, Neuroinflammation and Apoptosis in Rotenone-Induced Rat Model of Parkinson’s disease. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, P.; Ma, J.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Zou, Q.; Cai, Z.; Tang, Y. Curcumin Prevents Neuroinflammation by Inducing Microglia to Transform into the M2-phenotype via CaMKKβ-dependent Activation of the AMP-Activated Protein Kinase Signal Pathway. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2020, 17, 735–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.K.; Wang, L.; Wang, F.; Zhang, J. Resveratrol improved mitochondrial biogenesis by activating SIRT1/PGC-1α signal pathway in SAP. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhao, H.; Wang, L.; Tao, Y.; Du, G.; Guan, W.; Liu, J.; Brennan, C.; Ho, C.T.; Li, S. Effects of Selected Resveratrol Analogues on Activation and Polarization of Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated BV-2 Microglial Cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 3750–3757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Zhong, Y.; Gao, B.; Zheng, B.; Liu, Y. Nrf2-mediated therapeutic effects of dietary flavones in different diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1240433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadad, N.; Levy, R. Combination of EPA with Carotenoids and Polyphenol Synergistically Attenuated the Transformation of Microglia to M1 Phenotype Via Inhibition of NF-κB. Neuromolecular. Med. 2017, 19, 436–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulland, T.K.; Song, W.M.; Huang, S.C.-C.; Ulrich, J.D.; Sergushichev, A.; Beatty, W.L.; Loboda, A.A.; Zhou, Y.; Cairns, N.J.; Kambal, A.; et al. TREM2 Maintains Microglial Metabolic Fitness in Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell 2017, 170, 649–663.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Tang, Z. Therapeutic potential of natural molecules against Alzheimer’s disease via SIRT1 modulation. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 161, 114474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Ortega, F. Microglial modulation of neuronal network function and plasticity. J. Neurophysiol. 2025, 133, 661–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, A.W.; Hu, X.; Yoon, H.; Yan, P.; Xiao, Q.; Wang, Y.; Gil, S.C.; Brown, J.; Wilhelmsson, U.; Restivo, J.L.; et al. Attenuating astrocyte activation accelerates plaque pathogenesis in APP/PS1 mice. FASEB J. 2013, 27, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Li, Y.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Xu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Cai, L.; Gao, S.; Liu, T.; et al. Transcriptional and epigenetic decoding of the microglial aging process. Nat. Aging 2023, 3, 1288–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, M.N.; Barbosa-Silva, M.C.; Maron-Gutierrez, T. Microglial Priming in Infections and Its Risk to Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2022, 16, 878987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritzel, R.M.; Li, Y.; Jiao, Y.; Lei, Z.; Doran, S.J.; He, J.; Shahror, R.A.; Henry, R.J.; Khan, R.; Tan, C.; et al. Brain injury accelerates the onset of a reversible age-related microglial phenotype associated with inflammatory neurodegeneration. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadd1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, K.; Imagama, S.; Ohgomori, T.; Hirano, K.; Uchimura, K.; Sakamoto, K.; Hirakawa, A.; Takeuchi, H.; Suzumura, A.; Ishiguro, N.; et al. Minocycline selectively inhibits M1 polarization of microglia. Cell Death Dis. 2013, 4, e525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E Hickman, S.; Kingery, N.D.; Ohsumi, T.K.; Borowsky, M.L.; Wang, L.-C.; Means, T.K.; El Khoury, J. The microglial sensome revealed by direct RNA sequencing. Nat. Neurosci. 2013, 16, 1896–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinz, M.; Priller, J.; Sisodia, S.S.; Ransohoff, R.M. Heterogeneity of CNS myeloid cells and their roles in neurodegeneration. Nat. Neurosci. 2011, 14, 1227–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au, W.H.; Miller-Fleming, L.; Sanchez-Martinez, A.; Lee, J.A.; Twyning, M.J.; A Prag, H.; Raik, L.; Allen, S.P.; Shaw, P.J.; Ferraiuolo, L.; et al. Activation of the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway suppresses mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and motor phenotypes in C9orf72 ALS/FTD models. Life Sci. Alliance 2024, 7, e202402853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Chen, D.; Li, Y.; Gao, X.; Li, R.; Ma, T.; Zhang, Z. Molecular Mechanism of the Protective Effects of M2 Microglia on Neurons: A Review Focused on Exosomes and Secretory Proteins. Neurochem. Res. 2022, 47, 3556–3564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augusto-Oliveira, M.; Arrifano, G.d.P.; Leal-Nazaré, C.G.; Chaves-Filho, A.; Santos-Sacramento, L.; Lopes-Araujo, A.; Tremblay, M.; Crespo-Lopez, M.E. Morphological diversity of microglia: Implications for learning, environmental adaptation, ageing, sex differences and neuropathology. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2025, 172, 106091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rim, C.; You, M.J.; Nahm, M.; Kwon, M.S. Emerging role of senescent microglia in brain aging-related neurodegenerative diseases. Transl. Neurodegener. 2024, 13, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maassen, A.; Steciuk, J.; Wilga, M.; Szurmak, J.; Garbicz, D.; Sarnowska, E.; Sarnowski, T.J. SWI/SNF-type complexes-transcription factor interplay: A key regulatory interaction. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2025, 30, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, R.; Brösamle, D.; Yuan, X.; Beyer, M.; Neher, J.J. Epigenetic control of microglial immune responses. Immunol. Rev. 2024, 323, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunna, S.; Bowen, C.A.; Ramelow, C.C.; Santiago, J.V.; Kumar, P.; Rangaraju, S. Advances in proteomic phenotyping of microglia in neurodegeneration. Proteomics 2023, 23, e2200183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeki, K.; Ozato, K. Transcription factors that define the epigenome structures and transcriptomes in microglia. Exp. Hematol. 2025, 149, 104814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamera, K.; Trojan, E.; Szuster-Głuszczak, M.; Basta-Kaim, A. The Potential Role of Dysfunctions in Neuron-Microglia Communication in the Pathogenesis of Brain Disorders. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2019, 18, 408–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sofroniew, M.V. Astrocyte Reactivity: Subtypes, States, and Functions in CNS Innate Immunity. Trends Immunol. 2020, 41, 758–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escartin, C.; Galea, E.; Lakatos, A.; O’cAllaghan, J.P.; Petzold, G.C.; Serrano-Pozo, A.; Steinhäuser, C.; Volterra, A.; Carmignoto, G.; Agarwal, A.; et al. Reactive astrocyte nomenclature, definitions, and future directions. Nature 2017, 541, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liddelow, S.A.; Guttenplan, K.A.; Clarke, L.E.; Bennett, F.C.; Bohlen, C.J.; Schirmer, L.; Bennett, M.L.; Münch, A.E.; Chung, W.-S.; Peterson, T.C.; et al. Neurotoxic reactive astrocytes are induced by activated microglia. Nature 2017, 541, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baik, S.H.; Kang, S.; Lee, W.; Choi, H.; Chung, S.; Kim, J.-I.; Mook-Jung, I. A Breakdown in Metabolic Reprogramming Causes Microglia Dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 493–507.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, N.; McCabe, C.; Medina, S.; Varshavsky, M.; Kitsberg, D.; Dvir-Szternfeld, R.; Green, G.; Dionne, D.; Nguyen, L.; Marshall, J.L.; et al. Disease-associated astrocytes in Alzheimer’s disease and aging. Nat. Neurosci. 2020, 23, 701–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtman, I.R.; Raj, D.D.; Miller, J.A.; Schaafsma, W.; Yin, Z.; Brouwer, N.; Wes, P.D.; Möller, T.; Orre, M.; Kamphuis, W.; et al. Induction of a common microglia gene expression signature by aging and neurodegenerative conditions: A co-expression meta-analysis. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2015, 3, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Eisel, U.L.M. Microglia-Astrocyte Communication in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2023, 95, 785–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Mao, T.; Ma, R.; Xiong, Y.; Han, R.; Wang, L. The role of astrocyte metabolic reprogramming in ischemic stroke [Review]. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2025, 55, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, N.J.; Bhat, J.A.; John, U.; Bhat, S.A. Neuroglia in Neurodegeneration: Exploring Glial Dynamics in Brain Disorders. Neuroglia 2024, 5, 488–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, L.; Uyeda, A.; Muramatsu, R. Central nervous system regeneration: The roles of glial cells in the potential molecular mechanism underlying remyelination. Inflamm. Regen. 2022, 42, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, E.N.; Fields, R.D. Regulation of myelination by microglia. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, S.; Ranjan, S.; Das, S.; Kumari, J.; Singh, S. Role of growth factors and their interplay during oligodendroglial differentiation and maturation. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2025, 84, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosser, C.A.; Baptista, S.; Arnoux, I.; Audinat, E. Microglia in CNS development: Shaping the brain for the future. Prog. Neurobiol. 2017, 149–150, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hattori, Y. The multifaceted roles of embryonic microglia in the developing brain. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2023, 17, 988952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, Y.; Yamashita, T. Neuroprotective function of microglia in the developing brain. Neuronal Signal 2021, 5, NS20200024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, C.K.; Vidyadaran, S. Role of microglia in embryonic neurogenesis. Exp. Biol. Med. 2016, 241, 1669–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cserép, C.; Pósfai, B.; Lénárt, N.; Fekete, R.; László, Z.I.; Lele, Z.; Orsolits, B.; Molnár, G.; Heindl, S.; Schwarcz, A.D.; et al. Microglia monitor and protect neuronal function through specialized somatic purinergic junctions. Science 2020, 367, 528–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornell, J.; Salinas, S.; Huang, H.Y.; Zhou, M. Microglia regulation of synaptic plasticity and learning and memory. Neural Regen. Res. 2021, 17, 705. [Google Scholar]

- Béchade, C.; Cantaut-Belarif, Y.; Bessis, A. Microglial control of neuronal activity. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2013, 7, 42900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaraguru, S.; Morgan, J.; Wong, F.K. Activity-dependent regulation of microglia numbers by pyramidal cells during development shape cortical functions. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadq5842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriano, A.; Viviano, M.; Feoli, A.; Milite, C.; Sarno, G.; Castellano, S.; Sbardella, G. NADPH Oxidases: From Molecular Mechanisms to Current Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 11632–11655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, S.J.; Kikuchi, D.S.; Hernandes, M.S.; Xu, Q.; Griendling, K.K. Reactive Oxygen Species in Metabolic and Inflammatory Signaling. Circ. Res. 2018, 122, 877–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Liu, S.; Luo, J.; Tu, Y.; Li, T.; Li, P.; Yu, J.; Shi, L. Oxidative stress and reactive oxygen species in otorhinolaryngological diseases: Insights from pathophysiology to targeted antioxidant therapies. Redox Rep. 2025, 30, 2458942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.A.; Al-Jarallah, A.; Rao, M.S.; Babiker, A.; Bensalamah, K. Upregulation of NADPH-oxidase, inducible nitric oxide synthase and apoptosis in the hippocampus following impaired insulin signaling in the rats: Development of sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. 2024, 1834, 148890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamzeh, O.; Rabiei, F.; Shakeri, M.; Parsian, H.; Saadat, P.; Rostami-Mansoor, S. Mitochondrial dysfunction and inflammasome activation in neurodegenerative diseases: Mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Mitochondrion 2023, 73, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.; Xiong, W.; Fu, L.; Yi, J.; Yang, J. Damage-associated molecular patterns [DAMPs] in diseases: Implications for therapy. Mol. Biomed. 2025, 6, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naddaf, E.; Nguyen, T.K.O.; Watzlawik, J.O.; Gao, H.; Hou, X.; Fiesel, F.C.; Mandrekar, J.; Kokesh, E.; Harmsen, W.S.; Lanza, I.R.; et al. NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation and Altered Mitophagy Are Key Pathways in Inclusion Body Myositis. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2024, 16, e13672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Ren, K.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, H.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, X.; Yang, Y.; Wei, Z. Mitochondrial DAMPs: Key mediators in neuroinflammation and neurodegenerative disease pathogenesis. Neuropharmacology 2025, 264, 110217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paik, S.; Kim, J.K.; Shin, H.J.; Park, E.J.; Kim, I.S.; Jo, E.K. Updated insights into the molecular networks for NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2025, 22, 563–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.N.; Shaughness, M.; Collier, S.; Hopkins, D.; Byrnes, K.R. Therapeutic targeting of microglia mediated oxidative stress after neurotrauma. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 1034692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Yu, C.C.; Liu, X.Y.; Deng, X.N.; Tian, Q.; Du, Y.J. Epigenetic Modulation of Microglia Function and Phenotypes in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Neural Plast. 2021, 2021, 9912686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Ma, Z.; Chen, X.; Shu, S. Microglia activation in central nervous system disorders: A review of recent mechanistic investigations and development efforts. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1103416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heneka, M.T.; Kummer, M.P.; Stutz, A.; Delekate, A.; Schwartz, S.; Vieira-Saecker, A.; Griep, A.; Axt, D.; Remus, A.; Tzeng, T.C.; et al. NLRP3 is activated in Alzheimer’s disease and contributes to pathology in APP/PS1 mice. Nature 2013, 493, 674–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.-Y.; Ye, C.-Y.; Liu, Y.-C.; Wang, X.-M.; Fu, J.-C.; Liu, X.-Y.; Zhu, R.; Li, Y.-Z.; Tian, Q. Role of meningeal lymphatic vessels in brain homeostasis. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1593630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lall, D.; Baloh, R.H. Microglia and C9orf72 in neuroinflammation and ALS and frontotemporal dementia. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 3250–3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marchi, F.; Tondo, G.; Corrado, L.; Menegon, F.; Aprile, D.; Anselmi, M.; D’Alfonso, S.; Comi, C.; Mazzini, L. Neuroinflammatory Pathways in the ALS-FTD Continuum: A Focus on Genetic Variants. Genes 2023, 14, 1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLean, M.; Juranek, J.; Cuddapah, S.; López-Díez, R.; Ruiz, H.H.; Hu, J.; Frye, L.; Li, H.; Gugger, P.F.; Schmidt, A.M. Microglia RAGE exacerbates the progression of neurodegeneration within the SOD1G93A murine model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in a sex-dependent manner. J. Neuroinflam. 2021, 18, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunner, G.; Basu, H.; Lu, Y.; Bergstresser, M.; Neel, D.; Choi, S.Y.; Chiu, I.M. Gasdermin D is activated but does not drive neurodegeneration in SOD1 G93A model of ALS: Implications for targeting pyroptosis. Neurobiol. Dis. 2024, 214, 107048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catale, C.; Garel, S. Microglia in early brain development: A window of opportunity. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2025, 93, 103062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogerson-Wood, L.; Sawatari, A.; Leamey, C.A. Microglia: Mediators of experience-driven corrective neuroplasticity. IBRO Neurosci. Rep. 2025, 19, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrant, A.E.; Filiano, A.J.; Patel, A.R.; Hoffmann, M.Q.; Boyle, N.R.; Kashyap, S.N.; Onyilo, V.C.; Young, A.H.; Roberson, E.D. Reduction of microglial progranulin does not exacerbate pathology or behavioral deficits in neuronal progranulin-insufficient mice. Neurobiol. Dis. 2019, 124, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Ulland, T.K.; Colonna, M. TREM2-Dependent Effects on Microglia in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018, 10, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adaikkan, C.; Islam, M.R.; Bozzelli, P.L.; Sears, M.; Parro, C.; Pao, P.C.; Sun, N.; Kim, T.; Abdelaal, K.; Sedgwick, M.; et al. A multimodal approach of microglial CSF1R inhibition and GENUS provides therapeutic effects in Alzheimer’s disease mice. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Weyer, M.P.; Hummel, R.; Wilken-Schmitz, A.; Tegeder, I.; Schäfer, M.K.E. Selective neuronal expression of progranulin is sufficient to provide neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects after traumatic brain injury. J. Neuroinflam. 2024, 21, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhn, M.K.; Proctor, E.A. Microglial Drivers of Alzheimer’s Disease Pathology: An Evolution of Diverse Participating States. Proteins 2025, 93, 1330–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnathambi, S. α-Linolenic Acid Vesicles-Mediated Tau Internalization in Microglia. Methods Mol Biol. 2024, 2816, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; Li, F.; Zhang, S.; Chen, Y.; Ikezu, T.C.; Li, Z.; Martens, Y.A.; Qiao, W.; Meneses, A.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Enhancing TREM2 expression activates microglia and modestly mitigates tau pathology and neurodegeneration. J. Neuroinflam. 2025, 22, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramakrishnan, G.S.; Berry, W.L.; Pacherille, A.; Kerr, W.G.; Chisholm, J.D.; Pedicone, C.; Humphrey, M.B. SHIP inhibition mediates select TREM2-induced microglial functions. Mol. Immunol. 2024, 170, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daudelin, D.; Westerhaus, A.; Zhang, N.; Leyder, E.; Savonenko, A.; Sockanathan, S. Loss of GDE2 leads to complex behavioral changes including memory impairment. Behav. Brain Funct. 2024, 20, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyanova, S.; Banks, G.; Lipina, T.V.; Bains, R.S.; Forrest, H.; Stewart, M.; Carcolé, M.; Milioto, C.; Isaacs, A.M.; Wells, S.E.; et al. Multi-modal comparative phenotyping of knock-in mouse models of frontotemporal dementia/amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Dis. Model Mech. 2025, 18, dmm052324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Microglia Subtype | Key Molecular Features | Main Functions | Associated Conditions | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homeostatic Microglia | Tmem119, P2ry12, Cx3cr1, Sall1 | Synaptic homeostasis, immune surveillance | Healthy brain, early aging | [26,27] |

| Disease-Associated Microglia | Apoe, Lpl, Cst7, Trem2, Tyrobp | Phagocytosis, debris clearance, response to misfolded proteins | Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, ALS | [28] |

| Interferon-Responsive Microglia | Ifit2, Ifit3, Irf7, Isg15 | Antiviral response, interferon-driven inflammation | Alzheimer’s, viral infections, chronic neuroinflammation | [20] |

| Pro-inflammatory Microglia | Il1b, TNF, Ccl2, Nos2 | Cytokine production, amplification of neuroinflammation | Demyelinating diseases, acute injury, neurotoxicity | [29,30] |

| Aging-Related Microglia | Gpnmb, Dap12, Lgals3, Cd9 | Cellular stress response, senescence-associated dysfunction | Aging, late-stage Alzheimer’s | [26] |

| Proliferative Region-Associated Microglia | Mki67, Top2a, Cdk1 | Tissue repair, local clonal expansion | Active neurodegeneration, traumatic injury | [20] |

| Transitional Microglia | Mixed signatures: P2ry12, Apoe, Lpl | Intermediate state between homeostatic and DAM | Early-stage Alzheimer’s, neurodegeneration | [31,32] |

| Myelin-Associated Microglia | Spp1, Itgax, Lpl | Myelin phagocytosis, axonal repair | Multiple sclerosis, toxic demyelination | [20] |

| Neuroprotective Microglia | Igf1, Apoe, Spp1 | Neuronal survival promotion, trophic support | Acute injury, early neurodegeneration | [33] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rubio-Osornio, M.; Rubio, C.; Ganado, M.; Romo-Parra, H. The Double Face of Microglia in the Brain. Neuroglia 2026, 7, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/neuroglia7010003

Rubio-Osornio M, Rubio C, Ganado M, Romo-Parra H. The Double Face of Microglia in the Brain. Neuroglia. 2026; 7(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/neuroglia7010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleRubio-Osornio, Moisés, Carmen Rubio, Maximiliano Ganado, and Héctor Romo-Parra. 2026. "The Double Face of Microglia in the Brain" Neuroglia 7, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/neuroglia7010003

APA StyleRubio-Osornio, M., Rubio, C., Ganado, M., & Romo-Parra, H. (2026). The Double Face of Microglia in the Brain. Neuroglia, 7(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/neuroglia7010003