Abstract

This paper reviews, analyses, and suggests practical mitigation techniques at source for reducing vibration-induced annoyance to occupants in building structures that are built on top of significant railway infrastructure. The dynamic characteristics of vibration caused by wheel-rail interaction at metro train depots are different from those on main-lines and conventional studies. Ground-borne vibration in a building directly above a double-deck railway depot was investigated, focusing on vibration attenuation through rail track design, which is more effective and economic compared to treatments at receivers or along prorogation paths. A 2.5-Dimensional finite element model was established to simulate vibration transmission using different combinations of track-forms. Source contribution under different train running conditions has been evaluated by computing vibration levels along the main transmission path. Vibration levels at representative positions in the building rooms have been predicted using the numerical model and have been compared against site measurements at the corresponding locations after the completion of the construction of the depot and buildings. It was found that the 2.5D FE model enables a reasonable prediction of ground-borne vibration from the metro depot, and that by appropriate design of the track-form, a good level of vibration attenuation can be achieved in an economical way.

1. Introduction

1.1. Noise and Vibration from the Metro System

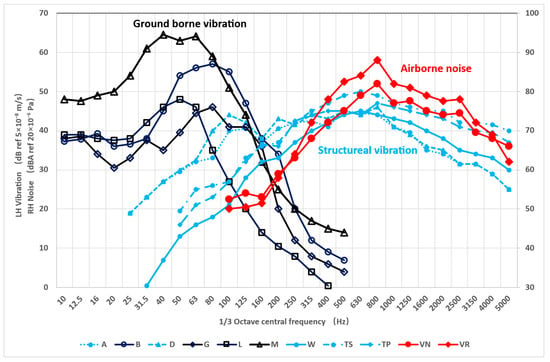

In railway engineering, the two coupled dynamical systems are the train-track system and the pantograph-catenary system. Noise and vibration from the train-track interaction include rolling noise, squeal noise, aerodynamic noise typically from high-speed rail, ground-borne vibration, and structure-borne noise [1]. These different categories of noise and vibration each features its own character frequency range, as shown in Figure 1. Ground-borne vibration features a relatively low frequency range in the railway dynamical system, typically below 100 Hz. On the other hand, structural vibration dominates between 200 to 2000 Hz. In the railway system, it is conventionally defined that low frequencies being below 10 Hz, medium frequencies being in-between 10 and 100 Hz, and high frequency range being above 100 Hz [2].

Figure 1.

Typical frequency ranges for different types of railway-induced noise and vibration (re-produced from original data in [2]).

Railway-induced ground-borne vibration deals with environmental concerns due to the generation and propagation of vibrations that affect the comfort and life quality of the inhabitants in railway surroundings. Such low frequency ground-borne vibration, typically in the range between 1 Hz and 80 Hz as per standard [3], is mainly due to wheel-rail interaction, especially where rail corrugation and wheel polygonalisation are present.

In a metro system, train-induced ground-borne vibration can be transmitted into nearby buildings through underground soil around a tunnel or the viaduct for elevated lines, causing nuisance and discomfort to inhabitants. A number of characteristic frequencies are excited on any conventional metro system, including bogie-passing, axle-passing, fastener-passing, rail corrugation excitations [2]. P2 resonance, vertical and lateral pinned-pinned frequencies, all above 20 Hz, are characteristic frequencies of long- and short-wavelength rail corrugation, which are responsible for ground-borne vibration due to railway traffic. Bogie-passing, axle-passing, and fastener-passing frequencies are not significant dynamic vibration sources in railways, as according to data [1,4,5,6,7], ground-borne vibration response at receivers below 10 Hz are very low, up-to 40 dB below peak magnitude vibration around 50 Hz and 63 Hz 1/3 octave band central frequencies.

In the past decades, research on railway-induced ground-borne vibration and mitigation measures for the control of noise and vibration for buildings along railway tracks have been undertaken [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Computational simulation has been extensively used to further investigate wheel-rail coupling problems [17,18,19,20,21] and to predict vibrations transmitted from source to receivers [22,23,24,25].

In terms of noise and vibration control, in any industry, e.g., industrial noise and vibration, occupational noise and vibration, and building services engineering such as HVAC, it is a common practice and rule of thumb to design and implement mitigation measures at source wherever possible [26,27,28] (“Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Prevention and Control of Noise Pollution” specifically says “to reduce and control at source”.). This is because reducing source intensity is often the most efficient technically and most economical means. Examples include the selection of quieter and low-vibration heavy machinery at factories; the selection of low noise and vibration emission hand-held tools for construction workers, the control of noise and vibration of air conditioning systems in office environments etc. When the control of source emission is insufficient, further mitigation measures through transmission paths, e.g., noise and vibration insulation techniques, and/or at receivers, e.g., noise reduction earmuffs for construction workers, sound absorption materials inside a room, etc.

1.2. Transit-Oriented-Development (TOD)

A transit-oriented-development (TOD), in a metro system, is a complex of building structures directly connected to a station or a railway depot (Some also define the TOD as all the building property forms within the surrounding 500 m range from a metro station or a train depot.). This particular urban development mode magnifies the amount of residential, commercial, and leisure space within the walking distance of public transport. TOD reduces environmental pollution and energy consumption and provides an effective financing channel for the construction and operation of metro-lines, promoting a sustainable development of the city.

In recent years in China, TOD directly above railway depots of a metro system tends to be popular, wherein the real estate investor and the metro owner work closely from the planning stage of a TOD scheme. A TOD in China typically includes various types of residential houses and buildings, educational facilities such as schools and nurseries, shops, etc.

Up to the end of 2024 in China, 55 cities have metro systems, over 40 of which were with TOD projects. The total real estate value of those TODs exceeds 1 trillion Chinese yuan. One of the key issues related to TOD is the noise and vibration impact from the railway depot, which is significantly different from the main line in the following aspects:

- The track layout at railway depots is far more complex, with a large number of small-radius curves, rail switches, and rail joints, leading to significant impact load and more frequent and severe vibration excitation.

- The operation modes at a typical railway depot of the metro system are significantly different from that on main lines. For instance, the majority of activities at the depot are undertaken during night-time hours or very early in the morning with low background noise; the operation hours at the depot also impose more stringent noise and vibration limits.

- Different train activities at the depot feature a wide range of train speeds, varying from 5 to 10 km/h in the inspection and maintenance warehouse; around 15–20 km/h at the throat zone (amongst the metro-line operators and relevant stakeholders in China, the throat zone is loosely defined as the area where tracks merge and diverge through rail switches between the main line and the railway depot); and up-to 60 km/h on the test track.

To this end, noise and vibration characteristics at source at railway depots are expected to be much more complex than those on the main lines in conventional studies in this field. Yet, noise and vibration impact from railway depots to people in buildings directly above has not yet been studied systematically.

Tao et al. [29] performed a vibration and noise impact assessment with measurements taken at receivers in buildings above a metro depot.

Cao et al. [7] measured ground-borne vibration from a metro depot at receivers. Structural analysis was carried out for key structural elements, including columns and floor slabs at the receiver building, with the conclusion that thicker slabs reduce vibration magnitudes, and therefore a good mitigation effect may be obtained. This falls outside of the scope of this paper, which is on noise and vibration control at source as railway engineers, during the track design stage, to achieve greater technical efficiency at lower costs.

Zou et al. [30] proposed vibration mitigation measures for a metro depot to use trackside wave barriers, which is a concept borrowed from high-speed railways, i.e., trenches. However, substantial space is required for the isolation of ground-borne vibration in 1 Hz to 80 Hz frequency range to take effects.

When designing a metro system against environmental noise and vibration impacts, national and industrial standards, and guidance are used. Owing to the cross-disciplinary nature of this type of engineering problem, inconsistencies in design limits exist between the standards in the metro system and in the building industry (Table 1). Lacking communication and coordination at the planning and design stage of the metro depot and property development sometimes leads to inefficient or even insufficient design of noise and vibration mitigation measures, which consequently cause complaints when the depot is under operation. So far, there has not yet been a dedicated standard or code of practice for the design of noise and vibration control for TOD above depots, partly due to the lack of understanding of dynamic characteristics and transmission patterns from the source to receivers.

Table 1.

Noise and vibration limit values in different Chinese standards and codes.

This research study aims at gaining a better understanding of the dynamic characteristics at different function areas at metro depots, as well as vibration transmission patterns from source to sensitive receivers at TOD. At this preliminary stage of the project, a numerical model was developed and validated against field data collected at existing railway depots. Vibration source contribution has been examined for trains running on the upper- and lower-deck of a double-deck metro depot. Ground-borne vibration to occupants in buildings above the depot using different track-forms combinations with different vibration isolation levels were quantified. An equivalent parameter method has been used in this study to couple the “train-track-tunnel-ground” model with the building above the TOD, all in 2.5D with reasonable assumptions, enabling quick modelling for assessment. The work so-far provides a full set of simulation and field measured data, for practical guidance for the design of rail track-form and vibration mitigation measures for TODs in China. The outputs focus on more effective and economical mitigation measures at source where possible, which are expected to shed insights for a design standard or guidance specifically for TOD above metro depots.

2. Research Methodology

2.1. The Double-Deck Railway Depot

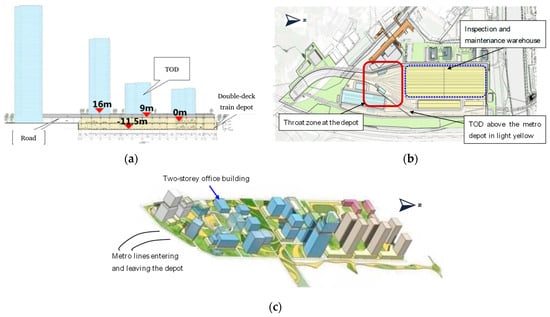

This study features a double-deck railway depot shared by several metro lines. The TOD above the railway depot, in this case, consists of high-rise residential buildings and houses; office buildings; a school; a nursery; merchandise shops; and miscellaneous facilities. A graphical illustration of the railway depot and above TOD is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The double-deck railway depot and above TOD: (a) the cross-sectional layout; (b) the plan view of the railway depot; (c) planned buildings above the depot.

Figure 2a shows the front view of the metro-line depot and its above TOD. The upper- and lower-decks of the depot is in light yellow. The ground level of the upper deck is defined as the “0 m plate”, the space in grey between the “9 m plate” and the “16 m plate” is a car park for residents and users at the TOD. The “16 m plate” is also called the roof plate of the depot. Figure 2b is the plan view of the depot, with different functional areas. Highlighted in red is the throat zone where tracks between the maintenance and inspection warehouse and the main lines merge and split. As tracks in this area feature a large quantity of rail joints and switches causing impact forces between wheel and rail, it is common practice to avoid tall building structures especially with sensitive noise and vibration receivers above this area at the design stage of TOD. In this case, some low-rise office buildings and merchandise shops are allocated above the throat zone. Inspection and maintenance warehouse is enveloped in dotted blue, at the rear of the depot. Sensitive receivers such as high-rise residential buildings, educational facilities are designed to be put above this area, as shown in Figure 2c.

It is a common practice, in railway depot applications, to divide the analysis according to the functionality of vibration sources. The test track, the throat zone, and the inspection and maintenance warehouse are three main function areas where wheel-rail induced vibration is most significant (Fixed plants such as train washing plants are also a major source of noise and vibration, but are relatively easy to treat, due to the steady state nature of the source. Usually fixed plants with quieter motor/source and a vibration isolation platform are sufficient for vibration control, thus is not included in this paper.). The following analysis steps were undertaken:

- The construction, verification, and validation of the computational model: a 2.5D Finite Element (FE) model was developed using Ansys software 2020 R2 [36]. The vibration level on the “16 m plate”, as per Figure 2a, was compared against field measurement collected from the depot roof plate at a similar depot, to validate the FE model.

- Using the validated FE model, vibration contribution of trains running on the upper-and lower-decks of the depot was evaluated, to support the design of rail track-forms on both decks.

- A parametric study was then undertaken wherein the vibration attenuation effect of using different combinations of track-forms at the throat zone with complex track geometry was examined, providing useful information for the design of vibration mitigation measures at source.

- After the completion of the construction of the depot, numerically computed vibration levels in rooms of the two-storey office building were compared to site measurement at corresponding sensitive receivers.

2.2. The Numerical Model

2.5D models are efficient tools for dynamic analysis of structures that are longitudinally invariant. Such models have been widely used in the studies of ground-borne vibrations caused by railways [25,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46].

2.2.1. The Rail Track Model

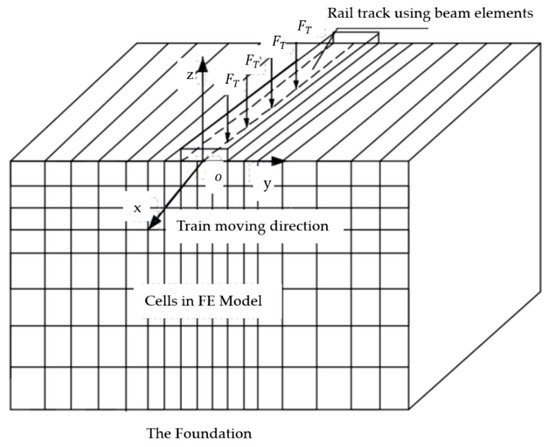

An illustration of the rail track structure-ground model is shown in Figure 3. The material and geometric properties are assumed to be invariant in the x direction, which is the train running direction.

Figure 3.

The rail track-ground FE model.

The tracks and sleepers are simplified and modelled with Euler–Bernoulli beams rested on half-space; the Equation of Motion (EoM) can be written as per Equation (1):

where is Young’s modulus, is the second moment of area about y-axis, is the overall mass of the rail and sleeper per unit length; is the vibration displacement of the rail; is the reaction force from the foundation; and is the train load.

By implementing the Fourier Transform, the above EoM of the beam can then be written as Equation (2) in the frequency domain, and finally represented in the matrix form in Equation (3):

where and are the wave number corresponding to x and circular frequency, respectively, in the frequency domain.

2.2.2. The Foundation Model

The soil foundation is assumed to be isotropic, the EoM in the frequency domain is shown in Equations (4) and (5).

wherein:

where are vibration amplitudes of the components of displacement along the directions, respectively; to are coefficients of soil reaction of isotropic soil; and are tensile modulus in the horizontal and vertical direction, respectively; denotes shear modulus in the vertical plane; is the Poisson’s ratio in the horizontal plane, and is the Poisson’s ratio of the strain in the vertical plane orthogonal to the normal stress in that plane.

Using the Galerkin method with fully coupled boundary conditions between rail tracks and the soil foundation, and visco-elastic boundary conditions for the soil foundation, a set of differential equation in the frequency–wavenumber domain can be obtained, as per Equation (6):

where are virtual displacement in the directions, respectively. A discretization of 8 node iso-parametric elements per sleeper bay is used, the EoM in the frequency–wavenumber domain is therefore written in the matrix form per Equation (7):

2.2.3. The Building Model

Conventionally, 3D FE models are built for structural analysis for buildings. However, for vibration impact concerning nuisance and comfortableness on habitants in buildings, 2.5D FE models is considered suitable for the following reasons.

- (1)

- The building in consideration is of simple rectangle shape, without curvature or any complex shape.

- (2)

- Structural columns within the office building are evenly distributed along the train running direction, which means periodical boundary conditions is applicable.

- (3)

- The “track-tunnel-ground” excitation source originates from the interaction between the “train-track” system. Since the train has a finite length, only the effect of one train’s length is considered herein. The finite train excitation source is assumed to be an infinite line source. The conditions assumed, here, are that the influence of the train’s length on the effects beyond a certain distance within the frequency range of interest can be considered negligible for a given observation point, e.g., a building. For example, the contribution of far-field excitation beyond 50 m to the near-field response of vibrations above 20 Hz can be considered negligible.

- (4)

- The frequency range of interests is between 1 Hz and 80 Hz, as per compliance standard; and the actual frequency range of interests from the majority of train-vehicle excitations and responses in the metro system is between 20 Hz and 80 Hz, which means short wavelength excitation at the wheel-rail coupled interface, which contributes the most energy in wheel-rail induce vibration, is dissipated through the transmission paths from the source to the receiver at the TOD.

- (5)

- The ground-borne vibration decay rate due to railway excitation is some 0.5 dB/m to 1.5 dB/m, i.e., around 10 dB attenuation with the source and receiver 10 m apart, which means that the truncation is irrelevant as long as the computational grid is large enough.

For the rest of the factors that might have an impact on the truncation from 3D to 2.5D, an equivalent parameter method has been used to transform the discontinuous 3D building into 2.5D, as described below.

The principle underlying the 2.5D FEA parameter equivalence is based on the equivalent energy and equivalent modes of the system, ensuring that the responses of the building’s excitations and observation points align with the actual 3D model. The coupling between the “track-tunnel-ground” and the “building” is transformed into 2.5D parameters by re-interpreting the equivalent “mass-damping-stiffness” parameters in the equation f motion of the 3D building, as per Equation (8).

where are mass, damping, and stiffness, with being acceleration, velocity, and displacement of the structure; and is the force.

- The main parameters in the building model are:

- (1)

- Equivalent mass: The equivalent total mass of key structural elements such as beams, columns, slabs, and walls per unit length is equivalent to the actual total mass of the building per unit length. This is achieved by using the equivalent material density.

- (2)

- Equivalent stiffness: The equivalent stiffness of the 2.5D building per unit length is the same as the actual stiffness of the key structural elements of the building, specifically the equivalent Young’s modulus E and cross-sectional moment of inertia I.

- (3)

- Equivalent damping: Different physical material damping coefficients are used for various sections within a building structure. The damping parameters in 2.5D FE and 3D FE models are identical in this case.

Equivalent parameter values used in the 2.5D FE building model is in Section 2.2.5.

2.2.4. Excitation Force from Wheel-Rail Interaction

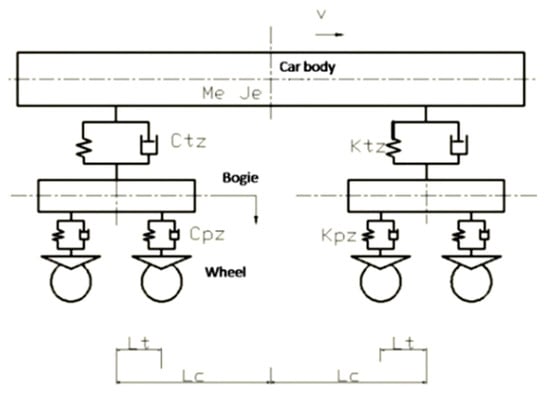

As shown in Figure 4, the train vehicle can be simplified and modelled as seven rigid-bodies, including the main car body, bogies, and wheels, with a total of 21 degrees-of-freedom, two translational, and one rotational for each rigid body, under wheel-rail interaction force in the vertical direction, i.e., z direction in Figure 3.

Figure 4.

The simplified train vehicle model.

The EoM of the train vehicle can be described by Equation (9):

where are the mass, stiffness, and damping matrices, respectively, while is the configuration parameter related to the track-foundation subsystem. represents the forces acting on the track, including the wheel-rail contact forces. The receptance of the wheel displacement of the train in the frequency domain can be obtained according to Equation (10):

where is the receptance of wheel with loading force applied at wheel ; and is the receptance matrix at the wheels of the train vehicle.

The total wheel-rail force, according to Thompson [1], comprises contributions from the receptance of wheel , the receptance of rail and that of wheel-rail contact forces , and can be expressed by Equation (11).

2.2.5. Input of the Numerical Model

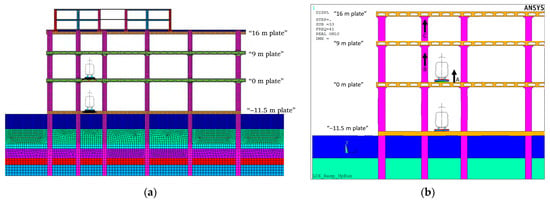

The double-deck railway depot was constructed with computation points along the main vibration transmission path (Figure 5). In Figure 5b, computation point A is on the ground at 7.5 m from the track centre-line on the “0 m plate”; point B is on the structural column at the “0 m plate”; and point C is on the column at the “9 m plate”, all calculated in the vertical direction.

Figure 5.

The FE model of the two-storey office building above the throat zone of the depot: (a) the cross-sectional view and (b) computation points along the main vibration transmission path.

Type A train vehicle was used in this study. Properties of the train vehicle are summarised in Table 2. As used in most metro railway depots, the rail is standard CN 50 rail, the mass of which is 50 kg/m. Material properties of key components of the track structure and track-bed are summarised in Table 3. Material properties of key components of the metro plates and key structural elements in the building are summarised in Table 4.

Table 2.

Input parameters of the train vehicle in the FE model.

Table 3.

Material properties of the track-bed in the 2.5D FE model.

Table 4.

Material properties of the depot and the building in the 2.5D FE model.

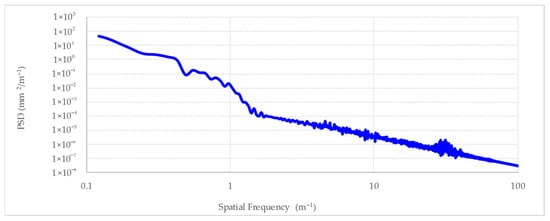

Roughness profile R of rails, for calculating the wheel-rail interaction force, consists of two parts. For wavelengths between 1 m and 300 m, R takes the value from the roughness profile in the FRA manual [47]. For shorter wavelengths, typically from 10 mm to 1 m, which correspond to medium- to high-frequency excitation, site measurements of rail roughness at a similar depot according to [48], using Corrugation Analysis Trolly (CAT) [49], were used. Total roughness profile across all frequency ranges (all wavelengths) is combined and shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

PSD of rail roughness R in the vertical direction.

2.2.6. Boundary Conditions

In the FE model, the foundation depth of the depot track-bed was set to be 20 m (Figure 5a), with three-dimensional visco-elastic artificial boundary conditions.

Dynamic analysis was performed throughout from the underground railway depot to its above TOD building structures.

2.2.7. Validation of the Numerical Model

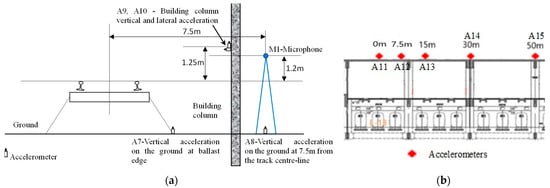

Numerically predicted total vertical vibration level on the “16 m plate”, directly above the vibration source, was compared against field data collected at the depot roof plate, at 0 m from the track centre-line above a track of the same track-form, at a similar railway depot (Figure 7). Measurement points and device setup are shown in Figure 8 and Figure 9, respectively.

Figure 7.

Photos of site measurement at a similar depot: (a) an aerial photo of the TOD and (b) noise and vibration measurement devices on the ground of the TOD.

Figure 8.

Site measurement points: (a) At vibration source and (b) on the ground of the depot roof plate.

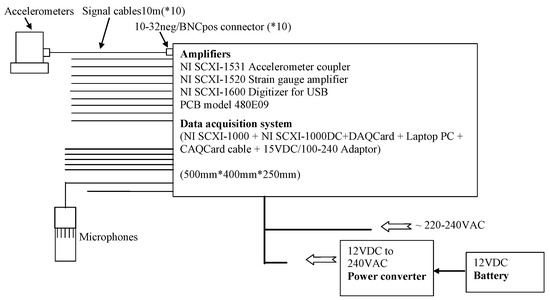

Figure 9.

Schematic diagram of the data collection system.

Vibration levels at the throat zone feathering rail switches were measured using PCB type low frequency high sensitivity accelerometers and were recorded with NI data acquisition system. Appropriate sensors were assigned at relevant locations to account for different frequency ranges, as per Table 5. For instance, sensors with a 0.5 g pk measurement range were chosen for low frequency vibration measurement on the ground of building plates (1–80 Hz as per ISO 2631-1:1997 [3]). In other words, the lower the measurement frequency range, the higher the measurement accuracy needs to be achieved.

Table 5.

Measurement sensor properties.

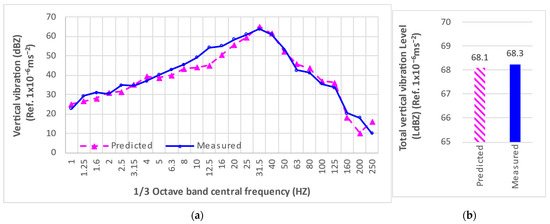

Frequency weighted vibration spectra and total vibration levels from the numerical model and from site measurements are shown in Figure 10. Vibration energy is summed up and presented in 1/3 octave bands, in terms of vibration amplitude in decibels (dB). As per ISO 2631-1:1997, total vibration level LdBZ is obtained by applying frequency weighting along the z-axis in the vertical direction.

Figure 10.

Comparison between predicted vibration level and site measurement: (a) 1/3 octave band spectra; (b) total vibration levels.

Both sets of data show a good agreement, in terms of the total value and the vibration contents in each 1/3 octave band. Therefore the 2.5D FE model is considered successfully validated and is ready to be used for further study.

3. A Parametric Study of the Vibration Mitigation Effects of Track-Forms

3.1. Track-Forms and Properties

Impact vibration at the throat zone of the depot is mainly caused by switches and rail joints for rails to merge and split. The lateral and torsional impact forces are much more significant compared to those of main-lines, it is more economic and efficient to reduce such vibration at source. Table 6 consists of commonly used track-forms in the metro system in China. Standard concrete slab tracks with non-resilient rail fasteners and concrete sleepers, typically of 10–12 m in length, was used as the reference track-form, i.e., standard track-form without vibration mitigation measures. Ballast provides good vibration isolation, but usually requires regular and sometimes intensive maintenance works, hence higher life-cycle costs. Vibration isolation mat is in general a long-term solution but is almost non-replaceable. Resilient rail fasteners provide some reasonable amount of vibration isolation, hence an economical solution if the vibration attenuation requirement is relatively low. Steel Spring Floating-Slab-Track (SSFST), on the other hand, offers a good level of vibration isolation, but it is expensive and should be applied only where necessary.

Table 6.

Track-form list.

Four combinations of track-forms on the upper- and lower-decks were designed as shown in Table 7. In theory, vibration level on the upper-deck contributes the most to vibration levels in buildings at TOD. This has been confirmed by simulating trains running on the upper-deck only, on the lower-deck only, and on both decks. The vibration attenuation capacity of the track-forms in Table 7 is in a gradually increasing order. For the parametric study, a reasonable train speed of 15 km/h was assumed for the throat zone.

Table 7.

Different combinations of track-forms for the upper and lower decks of the depot.

3.2. Vibration Contributions from Trains Running on the Upper- and Lower-Deck

Energy contribution of trains running on the upper-deck only; the lower-deck only was also examined.

Total vertical vibration levels at computation points along transmission path (Figure 5b) under the following conditions are summarised in Table 8:

Table 8.

Vertical vibration responses with different track-forms and train running conditions.

- (a)

- Test train running on the upper-deck only (TUD);

- (b)

- Test train running on the lower-deck only (TLD);

- (c)

- Test trains running on both the upper- and lower-decks simultaneously (TBD).

When trains are running on both the upper- and lower-deck simultaneously, by subtracting vibration response when the train runs on the upper-deck only, from vibration response when trains run on both decks, vibration contribution from the lower-deck (column “TBD-TUD”) as shaded in Table 8 can be obtained. With a baseline vibration level of at least 57.2 dB at point A at the source, vibration contribution from the lower-deck ranges from 0.2 dB to 0.7 dB, considered negligible. The finding confirms that the upper-deck rail tracks require more intensive vibration mitigation measures than the lower-deck rail tracks. Therefore, the rail track design in Table 7 is found to be sensible, with higher vibration mitigation measures such as SSFST at the upper-deck, and mainly resilient rail fasteners for tracks at the lower-deck.

3.3. Vibraton Attenuation at Sensitive Receivers

Vibration levels in the rooms of the two-storey office building in Figure 2c were computed for the comparison of vibration attenuation by different track-forms.

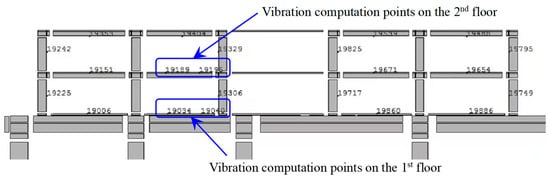

Vibration levels were predicted at computation points closest to the track centre-line, as shown in Figure 11. Calculation points 19034, 19040, 19189, and 19195 are on the floor in the rooms directly above the track centre-line and trains. Total vertical vibration levels at computation points in the building, as well as along the vibration transmission path as per Figure 5b, are summarised in Table 9.

Figure 11.

Vibration computation points in the office building.

Table 9.

Vertical vibration responses from vibration source transmitted to receivers.

Total vibration levels on the second floor of the office rooms are slightly higher than the corresponding calculation points underneath on the first floor of the building. This was due to the vibration frequency range being close to the modal frequency of the floor slab of the 2nd floor room and can be alleviated by re-arranging the modal frequency of the floor slab, by changing the thickness of the floor, amongst other means.

From the prediction, the use of ballast track with mat on the upper-deck tracks provides an overall 4.7 dBZ to 8.3 dBZ vibration attenuation effect. The use of SSFST on tracks of the upper-deck provides a vibration attenuation effect between 6.6 dBZ and 8.5 dBZ.

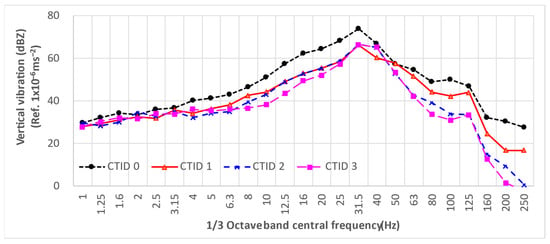

A comparison of the vibration spectrum in 1/3 octave frequency band at location 19034, i.e., in the middle of the room of the first floor office directly above the track centre-line, using the four combinations of track-forms is plotted in Figure 12. Using track-form option 0, i.e., the reference track-form without resilient track components, gives an overall highest vertical vibration in every frequency band. The use of SSFST on tracks on the upper deck provides a relatively good vibration isolation in the lower frequency range.

Figure 12.

Vibration spectra at computation point 19034 in the office building.

As expected, the use of SSFST features the peak vibration response in the low frequency range between 25 Hz and 50 Hz; and the use of under-ballast mat and rail resilient fasteners feature another peak vibration response at around 125 Hz.

3.4. Validation of the Computation

After the completion of construction of the depot and the TOD, site measurements in the rooms of the office building have been conducted, for comparison to numerical simulation results.

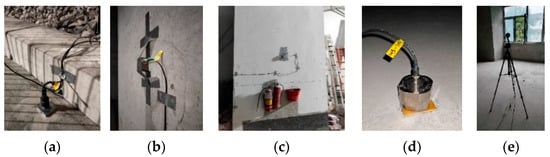

The final design of the track-form is steel spring floating-slab-track on the upper deck, and slab track with resilient rail fasteners on the lower deck. As the track works of the lower-deck is yet to be finished, measurements were undertaken when trains running on the tracks at the upper-deck below the office building. The train was scheduled to run 5 rounds northbound and 5 rounds southbound, that is a total of 10 train passing recordings, at an average train speed of 20 km/h. According to the Chinese national vibration measurement standard GB 10071-1988 <Measurement method of environmental vibration of urban area> [50], the 10 total vibration level readings are averaged to obtain the vibration level. To account for the train running modes and vibration features of southbound and northbound trips, 5 records of each direction was averaged. Site photos are shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Measurement devices at source and receiver rooms: (a) Accelerometer at 7.5m from the centre-line of the test track; (b) accelerometer on the structural column next to the test track; (c) accelerometer on the 9m plate structural column; (d) accelerometer on the floor slab in 2F room; and (e) microphone and accelerometer in 2F room.

Site measurement results, together with numerical prediction at the same location are summarised in Table 10. It can be seen that in general, southbound trains cause higher vibration levels than northbound trains. Measured data are somehow different from predictions, which can be due to a combination of factors such as uncertainties in train speed in terms of the assumption in the numerical model, and variation in train speed during testing.

Table 10.

Total vertical vibration level at different locations.

In addition, noise and vibration measurement at the source location, i.e., point A and point B along the cross-section at the test track, was at a certain degree, disrupted by surrounding environment, concurrent construction work onsite. Vibration levels inside the 2nd floor office room was lower than the prediction level and was well below the 75 dBZ upper limit in relevant standard, which was satisfactory to the property developer.

4. Conclusions

This part of the research work entails a preliminary study employing computational modelling to:

- Evaluate vibration contribution from trains running simultaneously on the upper- and lower-deck of a double-deck metro-line depot; this output gives an indication for the design of rail track-forms on the upper- and lower-deck.

- Examine receiver-end ground-borne vibration of using different track-forms representing different vibration mitigation measures at the source.

- Comparison of numerical simulation results and site measurements.

Key findings and conclusions are summarised below:

- Outputs from the 2.5D FE model in the study have been successfully validated against site measurements from a similar metro-line depot. Therefore, the model is adequate for the prediction of vibration transmission from the railway depot to the TOD built above the depot.

- It has been found that when trains run simultaneously on the upper- and lower-deck of the railway depot, vibration impacts from the train-track interaction on the lower-deck contributes no more than 1 dB, thus can be considered negligible.

- Compared to the reference track-form, using ballast track with vibration isolation mat on the upper-deck may provide up to 8 dB vibration insertion loss, whereas Steel Spring Floating Slab Track (SSFST) provides a similar level of vibration attenuation, i.e., no more than 1 dB difference. Ballast track with isolation mat is therefore a cost-effective option considering its lower capital cost.

Above findings can be used as general guidance in track design against vibration impact for buildings constructed on top of double-deck metro-line depots.

Vibration transmission from train-track source, through structural elements of a double-deck metro depot to closest receiver, i.e., a two-storey office building above the depot, using a successfully validated numerical model has been predicted. Vibration attenuation effects and trends using different track-forms, from non-resilient, to medium- to highly resilient track structures have been compared. Vibration levels measured onsite after the completion of the construction of the depot have been compared with numerically predicted results. Discrepancies were within 15% and were caused mainly by concurrent site construction works and the varying of actual train speeds.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.W. and H.H.; methodology, A.W. and X.P.G.; software, A.W. and X.P.G.; validation, A.W. and H.H.; formal analysis, X.P.G. and A.W.; investigation, A.W. and X.P.G.; resources, H.H. and A.W.; data curation, X.P.G.; writing—original draft preparation, X.P.G.; writing—review and editing, A.W.; visualisation, X.P.G.; supervision, A.W.; project administration, X.P.G.; funding acquisition, A.W. and H.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TOD | Transit oriented development |

| PSD | Power spectral density |

| PCB | PCB accelerometers |

| SSFST | Steel spring floating slab track |

| TUD | Test train running on the upper-deck only |

| TLD | Test train running on the lower-deck only |

| TBD | Test trains running on both the upper- and lower-decks simultaneously |

References

- Thompson, D. Railway Noise and Vibration: Mechanisms, Modelling and Means of Control, 1st ed.; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, S.J.; Wang, A.; Adedipe, A. Survey of Metro Excitation Frequencies and Coincidence of Different Modes. In Noise and Vibration Mitigation for Rail Transportation Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 2631-1:1997; Mechanical Vibration and Shock—Evaluation of Human Exposure to Whole-Body Vibration—Part 1: General Requirements. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1997.

- Degrande, G.; Schevenels, M.; Chatterjee, P.; Van de Velde, W.; Hölscher, P.; Hopman, V.; Wang, A.; Dadkah, N. Vibrations due to a test train at variable speeds in a deep bored tunnel embedded in London clay. J. Sound Vib. 2006, 293, 626–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Ground-Borne Noise and Vibration in Buildings Caused by Rail Transit; Transportation Research Board: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanayei, M.; Maurya, P.; Moore, J.A. Measurement of building foundation and ground-borne vibrations due to surface trains and subways. Eng. Struct. 2013, 53, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Guo, T.; Zhang, Z.; Li, A. Measurement and analysis of vibrations in a residential building constructed on an elevated metro depot. Measurement 2018, 125, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurzweil, L.G. Ground-borne noise and vibration from underground rail systems. J. Sound Vib. 1979, 66, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouakka, S.; Verlinden, O.; Kouroussis, G. Railway ground vibration and mitigation measures: Benchmarking of best practices. Railw. Eng. Sci. 2022, 30, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, 19M.; Mosayebi, S.A.; Zakeri, J.A. Ground-Borne Vibrations Caused by Unsupported Railway Sleepers in Ballasted Tracks. Procedia Eng. 2017, 199, 2645–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lurcock, D.E.J.; Thompson, D.J.; Bewes, O.G. Groundborne Railway Noise and Vibration in Buildings: Results of a Structural and Acoustic Parametric Study. In Noise and Vibration Mitigation for Rail Transportation Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Xiao, Z.; Liu, T.; Lou, P.; Song, X. Comparison of 2D and 3D prediction models for environmental vibration induced by underground railway with two types of tracks. Comput. Geotech. 2015, 68, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhairy, S. Prediction of Ground Vibration from Railways; Chalmers University of Technology: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Eadie, D.T.; Santoro, M. Top-of-rail friction control for curve noise mitigation and corrugation rate reduction. J. Sound Vib. 2006, 293, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eadie, D.T.; Kalousek, J.; Chiddick, K.C. The role of high positive friction (HPF) modifier in the control of short pitch corrugations and related phenomena. Wear 2002, 253, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eadie, D.T.; Santoro, M.; Oldknow, K.; Oka, Y. Field studies of the effect of friction modifiers on short pitch corrugation generation in curves. Wear 2008, 265, 1212–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torstensson, P.T.; Pieringer, A.; Nielsen, J.C.O. Simulation of rail roughness growth on small radius curves using a non-Hertzian and non-steady wheel-rail contact model. Wear 2014, 314, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torstensson, P.T.; Schilke, M. Rail corrugation growth on small radius curves-Measurements and validation of a numerical prediction model. Wear 2013, 303, 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.X. Parametric excitation of wheel/track system and its effects on rail corrugation. Wear 2008, 265, 1176–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.S.; Wen, Z.F.; Wang, K.Y.; Zhou, Z.R.; Liu, Q.Y.; Li, C.H. Three-dimensional train-track model for study of rail corrugation. J. Sound Vib. 2006, 293, 830–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Wen, Z.; Zhang, W.; Shen, Z. Numerical simulation of rail corrugation on a curved track. Comput. Struct. 2005, 83, 2052–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, A.G.; Aguilar, J.J.R.; Lopez, J.A.M. Towards the numerical ground-borne vibrations predictive models as a design tool for railway lines: A starting point THE. Transp. Res. Procedia 2021, 58, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcos, R.; Soares, P.J.; Costa, P.A.; Godinho, L. An experimental/numerical hybrid methodology for the prediction of railway-induced ground-borne vibration on buildings to be constructed close to existing railway infrastructures: Numerical validation and parametric study. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2021, 150, 106888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean, P.; Guigou-Carter, C. Reducing ground borne noise due to railways: A practical application. Appl. Acoust. 2021, 178, 108011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colaço, A.; Costa, P.A.; Amado-Mendes, P.; Calçada, R. Vibrations induced by railway traffic in buildings: Experimental validation of a sub-structuring methodology based on 2.5D FEM-MFS and 3D FEM. Eng. Struct. 2021, 240, 112381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U. Health and Safety Executive, How Do I Reduce Noise? n.d. Available online: https://www.hse.gov.uk/Noise/Reducenoise.Htm (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- U.S. Department of Labor. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, Occupational Noise Exposure. Available online: https://www.osha.gov/Noise/Exposure-Controls (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- The National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China. Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Prevention and Control of Noise Pollution. 2021. Available online: http://en.npc.gov.cn.cdurl.cn/2022-10/08/c_817695.htm (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Tao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Sanayei, M.; Moore, J.A.; Zou, C. Experimental study of train-induced vibration in over-track buildings in a metro depot. Eng. Struct. 2019, 198, 109473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Tao, Z. Vibration isolation of over-track buildings in a metro depot by using trackside wave barriers. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 30, 101270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 10070-1988; Standard of Environmental Vibration in Urban Area. Ministry of Ecology and Environment of People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 1988.

- GB 3096-2008; Environmental Quality Standard for Noise. Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2008.

- GB 55016-2021; General Code for Building Environment. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2021.

- GB 12348-2008; Emission Standard for Industrial Enterprises Noise at Boundary. Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2008.

- JGJ/T 170-2009; Standard for Limit and Measuring Method of Building Vibration and Secondary Noise Caused by Urban Rail Transit. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2009.

- ANSYS Mechanical APD 2020 R2, Synopsys, 2020. Available online: www.ansys.com (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Li, H.; Thompson, D.; Squicciarini, G. A 2.5D acoustic finite element method applied to railway acoustics. Appl. Acoust. 2021, 182, 108270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaseri, A.; Bazyar, M.H.; Javady, S. 2.5D coupled FEM-SBFEM analysis of ground vibrations induced by train movement. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2018, 104, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amado-Mendes, P.; Costa, P.A.; Godinho, L.M.C.; Lopes, P. 2.5D MFS-FEM model for the prediction of vibrations due to underground railway traffic. Eng. Struct. 2015, 104, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.B.; Liu, S.J.; Chen, W.; Tan, Q.; Wu, Y.T. Half-space response to trains moving along curved paths by 2.5D finite/infinite element approach. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2021, 145, 106740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.B.; Liu, S.J.; Li, Q.M.; Ge, P.B. Stress waves in half-space due to moving train loads by 2.5D finite/infinite element approach. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2019, 125, 105714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, D.P.; Galvín, P.; Olivier, B.; Romero, A.; Kouroussis, G. A 2.5D time-frequency domain model for railway induced soil-building vibration due to railway defects. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2019, 120, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.A.; Calçada, R.; Cardoso, A.S. Track–ground vibrations induced by railway traffic: In-situ measurements and validation of a 2.5D FEM-BEM model. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2012, 32, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghangale, D.; Arcos, R.; Clot, A.; Cayero, J.; Romeu, J. A methodology based on 2.5D FEM-BEM for the evaluation of the vibration energy flow radiated by underground railway infrastructures. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2020, 101, 103392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Thompson, D.J.; Lurcock, D.E.J.; Toward, M.G.R.; Ntotsios, E. A 2.5D finite element and boundary element model for the ground vibration from trains in tunnels and validation using measurement data. J. Sound Vib. 2018, 422, 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabib, M.; Rasheed, A.; Siddiqui, M.S.; Kvamsdal, T. A full-scale 3D Vs 2.5D Vs 2D analysis of flow pattern and forces for an industrial-scale 5MW NREL reference wind-turbine. Energy Procedia 2017, 137, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Transportation. U.S. Manual for High-Speed Ground Transportation Noise and Vibration Impact Assessment; Federal Railroad Administration; U.S. Department of Transportation: Washington, DC, USA, 2005.

- ISO 3095:2025; Railway Applications—Acoustics—Measurement of Noise Emitted by Railbound Vehicles. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025.

- RailMeasurement, Corrugation Analysis Trolley (CAT). Available online: https://www.railmeasurement.com/ (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- GB 10071-1988; Measurement Method of Environmental Vibration of Urban Area. Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 1988.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).