Abstract

Climate change is widely recognized as a significant contributor to both wildfire initiation and spread, conditions such as high temperatures and prolonged droughts facilitating the rapid ignition and propagation of fires. As a result, extreme weather events can trigger fires through lightning strikes with increases in frequency and severity. Despite this, we argue that it is important to distinguish and clarify the concepts of fire occurrence and fire spread, as these phenomena are not directly synonymous in the field of fire ecology. This review examined the published literature to determine if climate factors contribute to fire occurrence and/or spread, and evaluated how well the concepts are used when drawing connections between fire occurrence and fire spread related to climate variables. Using the PRISMA bibliographic analysis methodology, 70 scientific articles were analyzed, including reviews and research papers in the last 5 years. According to the analysis, most publications dealing with fire occurrence, fire spread, and climate change come from the northern hemisphere, specifically from the United States, China, Europe, and Oceania with South America appearing to be significantly underrepresented (less than 10% of published articles). Additionally, despite climatic variables being the most prevalent factors in predictive models, only 38% of the studies analyzed simultaneously integrated climatic, topographic, vegetational, and anthropogenic factors when assessing wildfires. Furthermore, of the 47 studies that explicitly addressed occurrence and spread, 66 percent used the term “occurrence” in line with its definition cited by the authors, that is, referring specifically to ignition. In contrast, 27 percent employed the term in a broader sense that did not explicitly denote the moment a fire starts, often incorporating aspects such as the predisposition of fuels to burn. The remaining 73 percent focused exclusively on “spread.” Hence, caution is advised when making generalizations as climate impact on wildfires can be overestimated in predictive models when conceptual ambiguity is present. Our results showed that, although climate change can amplify conditions for fire spread and contribute to the occurrence of fire, anthropogenic factors remain the most significant factor related to the onset of fires on a global scale, above climatic factors.

1. Introduction

Wildfires have been an integral part of the ecological cycles in several ecosystems long before the appearance of humans [1,2]. Fire coexisted with the evolution of several groups of terrestrial plants, mainly gymnosperms, contributing significantly to the distribution factors of flora and fauna worldwide, and thus to the formation of current ecosystems [1,2,3,4]. It has been clear that fires have acted as a selective factor in the evolution of vegetation, accompanying its adaptation to survive and even thrive in fire-affected environments [5,6,7,8,9]. According to research, different fire regimes have selected key adaptations in different species, such as regrowth capacity through resprouting, post fire regeneration via seed banks, bark thickness to withstand fire, temperature resistance of internal tissues, among others [9,10]. The above background makes it relevant to understand and recognize that some ecosystems require fire for their development and evolution, and that these ecosystems are natural to the planet [6,11] and adapted to a given fire regime [12].

However, recent decades have seen an alarming increase in the magnitude, frequency, and severity of wildfires, and therefore a change in fire regimes, globally [13,14,15,16]. These events have also been observed in regions where they do not occur so frequently [17]. As a consequence, people, society, and natural ecosystems have been adversely affected by these altered fire regimes. In addition to tropical forests, fires have also impacted savannas and scrublands, affecting roughly 200 to 500 million hectares annually [18,19], and being among the most serious disturbances in the world due to their economic, social, and environmental impacts [11,19,20,21,22,23,24]. Due to their increasing trend, wildfires are generating significant consequences in socio-environmental systems, whose impacts extend far beyond loss of biodiversity or degradation of ecosystems. As an example, fires in wildland–urban interface (WUI) zones are becoming more prevalent as a result of demographic expansion and the rise in WUI areas throughout the world [21,22,23,24,25,26]. The main consequences include loss of human lives, injuries, respiratory diseases, and structural damage, which highlight the vulnerability of society to increased fire regimes in these areas [27,28,29]. Additionally, wildfires can intensify social tensions between local actors, such as farmers, government agencies, and companies, particularly when fires are caused by human activities [30,31,32,33,34]. If this trend persists over time, wildfires may have even more serious consequences for the ecological balance, natural assets, ecosystem services, and socio-environmental systems [15,35,36,37,38].

The rise in fire frequency and extent is widely acknowledged to result from multiple factors, most of them linked to human impacts on ecosystems [1,39,40]. Among these, climate change has emerged as a dominant global driver [4,32,41,42,43,44]. To be precise, and following the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), climate change refers to a change in climate which is attributed directly or indirectly to human activity that alters the composition of the global atmosphere. This anthropogenically driven process is increasing risk conditions (such as droughts, heatwaves, and longer dry seasons) that promote the occurrence and spread of mega-fires [45,46,47,48].

Nevertheless, wildfires are almost entirely caused by direct anthropogenic ignition sources, either accidental or intentional, accounting for approximately 85% to 99% of all recorded ignitions worldwide [3,38,49,50]. In contrast, natural ignitions (lightning or volcanic activity) are statistically minor [14,15,51,52] but their occurrence spatially varies. Therefore, when attributing wildfire occurrence to climate change, caution is necessary. Climate change alters the biophysical conditions that favor ignition and fire spread; however, its influence interacts with regional fire regimes and socio-ecological contexts. In ecosystems where human presence is high, most ignitions originate from anthropogenic sources, whereas in lightning-dominated regions natural ignitions can play a comparatively larger role [53,54].

This distinction reveals a key conceptual problem often overlooked in both science and policy: although both processes are anthropogenic in their origin, they operate at different scales and through different mechanisms. Global-scale anthropogenic processes drive climate change, indirectly amplifying fire risk, whereas local-scale human actions directly cause ignitions. Conflating these two forms of causality leads to misattribution of drivers and misinformed fire management strategies. Effective prevention requires reducing ignition sources (through education, land-use planning, and law enforcement), while adaptation must focus on mitigating spread under changing climatic conditions. Recognizing this distinction is essential for both conceptual accuracy and the design of effective fire policies.

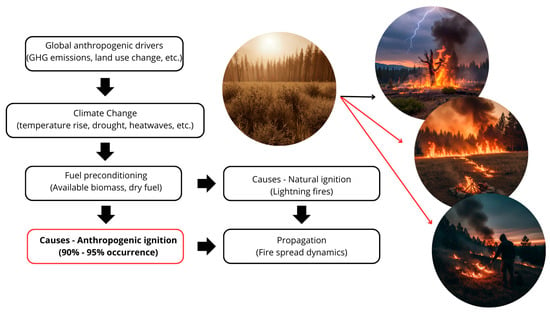

Lastly, it is essential to establish precise definitions before advancing the discussion. Differentiating between drivers, factors, and causes is crucial for understanding the framework of this review. Drivers refer to underlying processes or large-scale conditions that modify fire regimes over extensive temporal and spatial scales (e.g., climate change, land-use transitions) [27]. Factors are specific, measurable variables that influence the probability of fire occurrence and/or fire spread, such as fuel moisture, slope, or human accessibility [55]. Finally, causes correspond to the direct ignition agents that trigger the start of a fire. This conceptual distinction is critical to avoid misattributing mechanisms and to better guide effective strategies for wildfire prevention and risk management [38] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of the causality and dynamics of wildfires, with emphasis on depicting anthropogenic ignition (images generated by AI, Gemini 3).

In this systematic review, we synthesize the recent literature (2020–2024) to disentangle the relative contributions of climatic and anthropogenic drivers to fire occurrence and spread. Our objectives are as follows: (1) to identify the main factors influencing wildfire occurrence and their interactions with climatic variables; (2) to evaluate how temperature increases and related climatic anomalies are associated with fire spread relative to ignition probability; and (3) to clarify and operationalize the concepts of occurrence (ignition) and spread to improve attribution in future research. By explicitly distinguishing these processes, this review aims to strengthen the theoretical and practical basis for preventing ignitions and adapting to climate-driven fire dynamics.

2. Materials and Methods

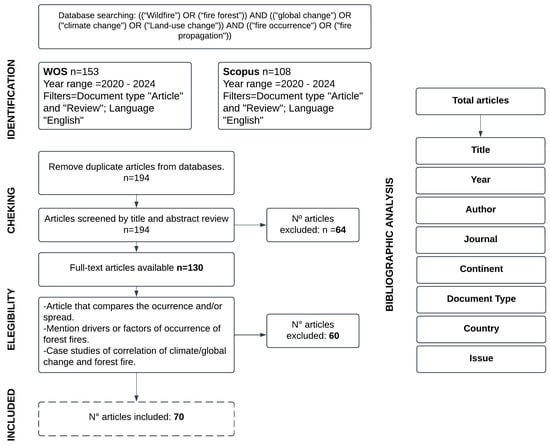

Using the PRISMA systematic review methodology, as defined by Page et al. (2021), we conducted the literature review. PRISMA provides a rigorous, transparent, and structured framework for identifying, screening, and selecting scientific evidence, ensuring that each step of the review process is explicitly documented. This methodology organizes the workflow into clearly defined stages, including the formulation of research questions, identification of data sources, application of inclusion and exclusion criteria, removal of duplicates, and full-text assessment. Such structure minimizes subjective bias, increases traceability, and improves the overall reliability of systematic reviews. Following this standardized procedure, seven sections comprising a total of 27 items ensured the proper organization of the article, facilitating information retrieval and the synthesis of findings [56]. The PRISMA flow diagram allowed us to detail the number of records identified, screened, excluded, and retained for qualitative synthesis, reinforcing transparency in the decision-making process. In addition, a Supplementary Material File presents a detailed step-by-step description of the methodology, including the specific criteria applied, the operationalization of the 27 PRISMA items, and the justification of exclusion decisions. This Supplementary Documentation enhances the replicability of the study and provides readers with full methodological clarity. All references from the selected articles were managed using Zotero 6.0.26 citation software.

2.1. Literature Search

This article is based on a systematic literature review conducted between 18 November and 20 December 2024. Scopus and Web of Science (WOS) databases were used exclusively to search and index articles. This search incorporated general keywords related to wildfires, global change, land-use changes, and climate change, as well as specific concepts such as fire occurrence and spread, which resulted in the following syntactic search for optimal information retrieval: TITLE-ABS-KEY = ((“wildfire”) OR (“forest fire”)) AND ((“global change”) OR (“climate change”) OR (“land-use change”)) AND ((“fire occurrence”) OR (“fire propagation”)).

We applied specific filters to our search. As a first step, only original articles and scientific reviews were selected, excluding conference proceedings, book chapters, or other articles within the range of “grey literature”. Secondly, the scope of the study was limited to a five-year period (2020–2024), in order to include only recent research that reflects trends in the field of wildland fire. Finally, only papers published in English were selected, given its predominance in the production and dissemination of scientific knowledge. After applying these selection criteria, an exhaustive bibliographic analysis of the included articles was conducted. There were multiple categories assigned to each document, including title, publication year, authorship, scientific journal, continent and country of origin, type of document (empirical articles or scientific reviews), and variables related to fire occurrence and spread. After applying the aforementioned filters, articles were first pre-selected based on their titles and abstracts. Then, a detailed review was conducted using three main inclusion criteria. Only studies that met all the following conditions were considered: (1) comparisons and/or analyses between wildfires occurrence and spread, (2) factors influencing wildfires occurrence and spread, and (3) case studies of the association between climate/global change and wildfires occurrence and spread.

2.2. Information Analysis

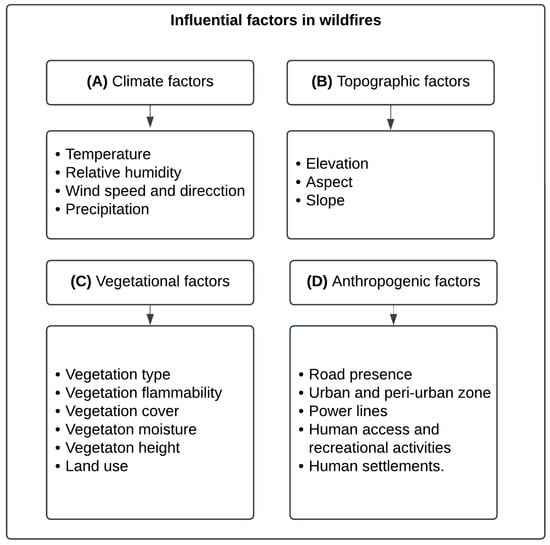

For each of the selected articles, a specific bibliographic analysis was conducted, which classified all fire occurrence factors into five main categories. These categories are not mutually exclusive, meaning that a single study may belong to two or more categories depending on the factors it addresses. (1) climatic factors: temperature, humidity, precipitation, winds, electrical storms; (2) biological factors: available fuel, exotic/invasive species, flammable vegetation; (3) anthropogenic factors: agricultural activity (i.e., land-use), urban expansion, negligence, infrastructure, change in use; (4) topographic factors: slope, orientation, altitude (Figure 2). Using this classification, a detailed analysis was developed, examining the relationships between each of the factors and fire occurrence. Additionally, we examined how these factors interact with climate change in order to influence the occurrence and spread of fires. A focus was placed on the synergy between climatic and anthropogenic factors, since they may contribute to the acceleration of global warming; for this point, articles that explicitly analyze these variables were used (47 out of 70). As a final step, a comparative analysis of fire occurrence in selected case studies was proposed. This analysis investigated whether observed changes in fire occurrence are primarily caused by factors related to climate change or, on the contrary, result of interactions between biological, anthropogenic, and topographic factors. As a result of this approach, climate change can be contextualized and differentiated from factors affecting wildfires dynamics of more local or regional relevance.

Figure 2.

Diagram of factors of direct influence on the dynamics of wildfires assessed in the review, grouped into 4 categories; climate, topographic, vegetational, and anthropic.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Search Results

The systematic search of the scientific databases SCOPUS and Web of Science (WOS) produced 261 articles, divided between 108 articles from SCOPUS and 153 articles from WOS. Following the elimination of duplicate articles, a set of 194 unique articles was obtained (Figure 3). The initial reduction to 130 articles occurred because 64 studies did not meet the previously established inclusion criteria. Specifically, these studies did not address at least one of the following: (1) comparison or analysis between fire occurrence and spread, (2) identification and discussion of factors associated with fire occurrence, or (3) case studies examining the relationship between climate (or global) change and fire occurrence or increased fire frequency. During the full-text assessment, these same criteria were applied again in greater depth, resulting in a final selection of 70 articles. This second reduction occurred when some studies, although mentioning wildfires or climate change in general terms, did not include analyses aligned with the objectives of the review or lacked sufficient information to allow systematic comparison.

Figure 3.

A flow chart showing the stages of the methodological procedure for finding and selecting articles for the review, and organizing the articles included in the review.

After applying the above criteria rigorously, 70 articles (see Appendix A) that met the criteria for inclusion were selected in this systematic review. We use this filtering process to ensure that the sources used in this study are relevant and of high quality, ensuring that the conclusions represented in this study are in line with the stated objectives.

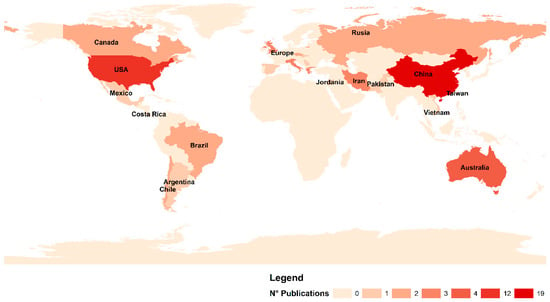

Final selections include empirical and predictive modeling studies, providing a comprehensive perspective on the interactions between climatic and anthropogenic factors in wildfire dynamics. In addition, the selected papers present evidence from a variety of regions and types of forest ecosystems from around the world, providing a comparative analysis of how global change and climate variables influence fire regimes worldwide, but with a significant concentration in the northern hemisphere, mostly in Asia, followed by North America and Oceania (Figure 4). There may be a connection between this distribution and regions where wildfires present a significant environmental and economic challenge, as well as more developed scientific research capacities in some regions.

Figure 4.

Global distribution of publications related to the topic of this review. Increased number of publications is mainly observed in North America and Asia (global north), while the southern hemisphere is much less represented.

3.2. Influencing Factors of Fire Occurrence and Their Relation to Climate Change

In the articles reviewed, a variety of variables are found to influence wildfire occurrence, as fire is caused by a complex and dynamic interaction between several factors [33,55,56,57,58,59]. As a general rule, they can be classified as (a) climatic, (b) topographical, (c) vegetational, and (d) anthropogenic factors. They all influence fire dynamics in different ways, either by promoting ignition and/or flame sustainability, or by influencing the rate and extent of spread [55,60,61,62].

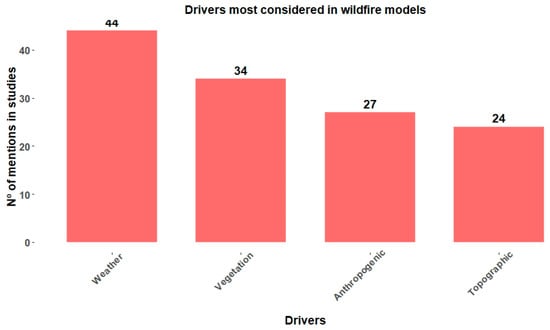

We found a discrepancy in the relative importance of these factors based on the significance of the variables. Several studies highlighted accessibility and human activity in wildlands [63,64,65] while others pointed to early successional vegetation and moderate slopes as relevant contributors for the occurrence of fires [66,67,68,69]. Fires are also more likely to occur in particular types of landscape cover [67,70,71,72]. Despite this, climatic variables overwhelmingly dominate fire occurrence and spread models (Figure 5). Temperature, relative humidity, accumulated precipitation, and wind patterns influence fuel moisture, which in turn plays an important role in shaping fire occurrence and spread [68,71,73,74]. Although these variables are generally considered highly responsive to atmospheric shifts associated with global climate change [52,75], their specific contribution to ignition processes can vary depending on context and fuel characteristics. Consequently, most wildfire risk prediction models emphasize their relevance while recognizing that ignition dynamics often emerge from the combined action of climatic and non-climatic drivers.

Figure 5.

Studies where various factors of occurrence of wildfires were analyzed, grouped into weather, vegetation, anthropic, and topographical drivers.

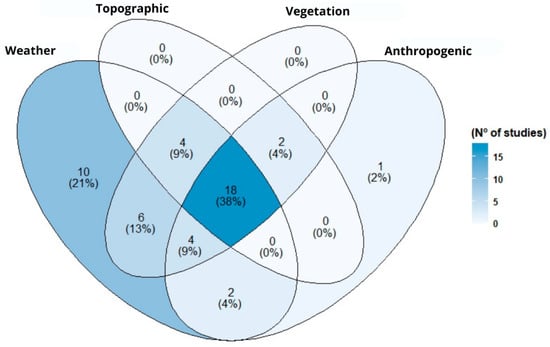

However, this predominance should not be understood merely as a methodological outcome but as a conceptual over-representation in how the relationship between climate change and fire occurrence is interpreted. In most cases, climatic variables are treated as the main determinants of ignition, when global evidence shows that approximately 90% of wildfires originate from direct anthropogenic causes, whether accidental or intentional [38]. This perspective tends to assign climate a causal responsibility that actually lies with human activity, shifting the discussion away from local drivers (such as land-use, agricultural practices, territorial management, or urban expansion) toward a more abstract environmental framework. While climatic conditions such as temperature, drought, and vapor pressure deficit increase the predisposition of landscapes to burn and therefore play a critical role in fire spread, they do not explain its initial occurrence. Nevertheless, within the set of risk models and empirical studies analyzed in this review, climatic variables are often treated as if climate change directly triggered ignition, without sufficiently incorporating the influence of local human factors, which in these studies emerge as key triggers of fire occurrence. Furthermore, by analyzing the interaction between the different factors considered in risk models (see Figure 6), it is observed that only 38% of the studies include the four groups of factors, resulting in integrated models that better capture the complexity of fire dynamics. Conversely, 21% of the studies focus exclusively on climatic variables, demonstrating that trends depend on climatic factors, with high temporal and spatial variability. It is possible that this over-representation of climatic factors in univariate studies will result in an underestimation of risk if vegetation factors and mainly anthropogenic factors are underrepresented [58,59,76]. These findings suggest that the influence of climate change on fire occurrence is not homogeneous but rather operates through the amplification of specific enabling factors (mainly related to climatic conditions and vegetation characteristics) that increase the likelihood of fire spread rather than ignition, particularly in fires of anthropogenic origin. This interpretation highlights that climate change acts primarily as a modulator of fire behavior, creating conditions that facilitate the expansion and intensity of events initially triggered by human activities, rather than as a direct cause of fire occurrence itself.

Figure 6.

Venn diagram highlighting the interaction of factors considered in wildfire models for the different studies assessed in the review (47 of the 70 studies evaluated these variables).

Despite the predominance of anthropogenic ignitions in terms of global frequency, it is essential to distinguish between ignition frequency and burned area when interpreting fire occurrence patterns. Natural ignitions, particularly lightning-caused fires, account for a relatively small proportion of total ignition events, yet they frequently dominate the annual burned area in high-biomass and remote regions where suppression capacity is limited. This pattern has been extensively documented in boreal and sub-boreal ecosystems of Canada and Alaska, where lightning fires can account for more than 70 percent of the area burned in some years due to their high ignition efficiency and the prevalence of “holdover fires” that remain undetected for days before expanding under favorable weather conditions [14,68]. Similar dynamics have been reported in Siberia and the Russian Far East, where lightning-driven wildfires are responsible for extreme fire seasons characterized by very large burn scars in remote taiga landscapes [52]. Even in temperate regions such as the western United States, lightning ignitions have historically generated some of the largest and longest-lasting wildfires, particularly during periods of fuel accumulation and prolonged drought [77,78]. In Chile, although lightning-caused fires represent a minor fraction of total ignitions, natural ignitions occurring in remote Andean or Patagonian forests have produced disproportionately large burned areas under extreme weather conditions [53,79]. Recognizing this distinction between ignition frequency and impact is fundamental to avoid underestimating the ecological and management relevance of natural ignitions, which, despite being less common, can exert disproportionate influence on total burned area in specific biomes.

3.3. Increasing Temperatures and Wildfires

Fires are necessarily always triggered by ignition sources, even when conditions like dry vegetation and climatic conditions favor their spread [33]. Ignition sources can be natural, such as lightning or volcanic eruptions (lightning being the most common), or anthropogenic, either intentional or accidental. No fire can start without this initial trigger, regardless of the extreme environmental conditions. In boreal regions, however, the increase in global temperatures is altering natural ignition patterns, especially by increasing the frequency of dry storms and lightning [80,81,82].

The increase in temperature has altered fire regimes, facilitating ignition, but primarily spreading and escalating fires [46,83]. In areas such as Alaska and northern Canada, an increase of 1 °C consistently raises lightning ignition efficiency from 14% to 31%, which translates into a 40% to 65% increase in the likelihood of naturally occurring fires [68]. According to another study, global warming has accelerated lightning strikes by approximately 41% at the global scale, leading to an increase in naturally ignited forest fires [84]. This effect is particularly pronounced in South America, the western coast of North America, Central America, Australia, southern and eastern Asia, and Europe, where the frequency of lightning-related ignitions has risen more noticeably [53,84]. Moreover, a study conducted in Asia asserts that the rise in temperature has a direct effect on natural fires, amplifying their spread and severity [85]. When it comes to propagation and amplification effects, however, the temperature increase plays a much greater role, reducing fuel moisture and increasing the vapor pressure deficit [86,87,88]. In China, El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) plays a key role in fire spread by affecting humidity and temperature distribution in different regions [57,86] and, the most important factor affecting fire dynamics is climatic variability, especially temperature [55,60,74,85,89,90,91]. Fires have increased in severity and frequency in Australia due to an increase in heat waves, but mainly due to decreased precipitation [92]. Finally, the increase in temperatures in North America has prolonged the duration of fires, specifically in boreal regions, which makes them more intense and severe [38,62,78,80,81,93,94].

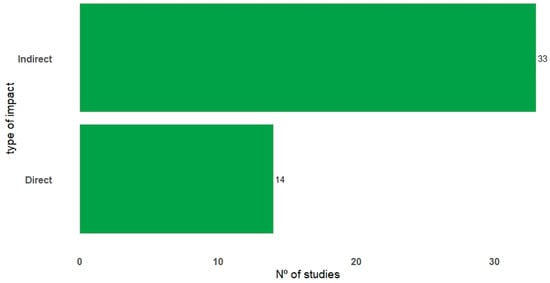

In general, 70% of the studies examined, out of the total subgroup of 47 that analyzed these variables, revealed that the variables associated with increased temperature had an indirect impact on forest fires (Figure 7). Therefore, it is important to note that, although this factor does not directly cause fires, it modifies environmental conditions (for example, by reducing vegetation moisture), which causes fires to spread, intensify, and last longer [71,95,96]. Conversely, 30% of studies have found a direct connection between elevated temperatures and fire initiation, particularly in natural contexts where warming increases the frequency of lightning strikes during dry storms. This has been documented in countries like the United States, Canada, Chile, and Australia [81,82,84,97]. Despite the fact that anthropogenic factors continue to trigger ignition, climate change acts as a critical amplifier, either by facilitating conditions for spread (indirect impact) or, to a lesser extent, by increasing natural ignition risks (direct impact).

Figure 7.

Relationships (direct vs. indirect) linking the impact of temperature increase with the occurrence of natural wildfires, being indirect if the temperature affects propagation and direct if it affects the occurrence of wildfires.

3.4. Concept of Fire Occurrence and Fire Spread

As mentioned above, two concepts are frequently used in the current review: occurrence and spread. Although they are often treated as synonyms, it is important to distinguish between them because both are influenced by different drivers and have distinct implications for risk management and for understanding how climate change affects fire regimes. In a physical and behavioral sense, the occurrence of a fire refers to the exact moment in which a fire starts, that is, the ignition process that initiates combustion, which is uncontrolled and may phase into a wildfire [86]. For this event to take place, there must be an ignition source, either anthropic or natural [33,62]. Spread or propagation, however, is the horizontal expansion of a fire once it has been ignited [55].

Of the 48 articles reviewed that addressed the concepts of fire occurrence and spread, 66 percent (32 articles) explicitly used the term occurrence in their conclusions, suggesting that the factors analyzed directly influenced either fire ignition or detection. Among these 32 articles, only 13 (27 percent) applied the concept of occurrence in the narrow sense adopted in this review, referring specifically to the ignition phase rather than to fire spread [38,40,56,57,60,66,72,74,85,87,89,92,97,98,99,100,101,102,103]. The remaining studies used the term more broadly or interchangeably with spread. In many cases, they applied the standard statistical definition employed in predictive fire modeling, where occurrence denotes the probability that a fire is detected in a given spatiotemporal unit under specific environmental conditions. Under this framework, climatic variables legitimately influence fire occurrence because they modulate fuel receptivity, ignition sustainability, and the likelihood that a nascent ignition becomes a detectable fire. Recognizing this dual usage is crucial. Treating occurrence strictly as ignition may lead to dismissing the climatic controls that affect the probability of a successful and observable ignition. Conversely, treating occurrence only as the result of climatic conditions can obscure the dominant role of human activities, which generate nearly 90 percent of ignition sources worldwide. Misinterpreting the scale and meaning of occurrence may therefore lead to biased causal attributions and to overestimating the direct role of climate as a trigger. In our sample, 73 percent of the studies analyzed in this section focused on fire spread or on occurrence modeled as a climate-sensitive probability, while only 27 percent addressed ignition sources, incorporating climatic, vegetational, topographic, and anthropogenic variables [104,105,106].

Distinguishing between potential ignition sources (the spark) and realized fire occurrence (the detectable event) is fundamental not only for understanding fire dynamics but also for designing more efficient public policies. Climate change is an important factor to consider because it affects the conditions that promote fire spread and increase the probability that an ignition persists. However, in most instances, it is not the main cause of ignition itself. In this context, factors of human origin must be examined in greater depth, since they constitute the major global source of ignition [59,76,99,107]. To reduce the incidence of fires in WUI areas, preventive measures centered on human behavior, land-use, and management are essential. Moreover, attention must be paid to the flammability and availability of vegetative fuel, since not all vegetation exhibits the same level of flammability; some species can help reduce fire behavior depending on their characteristics [107,108,109]. Managing highly flammable species and reducing fuel loads can significantly prevent or delay ignition from becoming a sustained fire, thereby increasing response and control capacity.

3.5. Limitations

This review presents a primary limitation related to the search criteria. The literature search was restricted to English-language publications, which may have excluded relevant studies conducted in South America, particularly those published in Spanish or Portuguese. As a result, this restriction could have contributed to the underrepresentation of research from this region in the final dataset. This limitation underscores the need for broader multilingual searches in future systematic reviews to achieve a more comprehensive regional balance.

4. Concluding Remarks

This systematic review highlights that wildfires are a highly complex phenomenon, whose dynamics (particularly during the ignition phase) are influenced by multiple interrelated factors, including climatic, biological, topographical, and especially anthropogenic components. Over recent decades, an increase in the magnitude and frequency of these events has been observed, and although this trend is likely to persist under current global conditions, distinguishing the causes of ignition and spread is essential to improve predictive models, management practices, and prevention strategies, rather than assuming that a better understanding alone will reverse these patterns.

It is important to note that, although climate change modifies variables such as temperature, humidity, wind regimes, precipitation, and vegetation characteristics, its influence is mainly associated with the spread and behavior of wildfires rather than their direct occurrence. However, climate change can directly increase the frequency of natural ignitions through a higher incidence of lightning storms or dry thunderstorms, mainly in boreal areas or high mountain ranges. These processes, however, often act synergistically, where human negligence or intentional actions coincide with more flammable and drier fuels caused by climatic anomalies. Recognizing this interaction is important, but maintaining a clear conceptual distinction between direct anthropogenic ignition and climate-driven propagation is essential to correctly interpret causality and improve the design of management and mitigation strategies.

A predominant trend in the literature continues to emphasize climatic variables in predictive models, leaving aside other equally relevant factors such as vegetation composition, topography, and, above all, human influence. This bias has limited the correct understanding of the phenomenon, since globally, around 90% of wildfires are directly caused by human activities, whether accidental or intentional. Additionally, within the set of studies analyzed in this review, socioeconomic dimensions (such as land-use practices, environmental education, and governance) are less frequently incorporated into wildfire risk models, despite their relevance for explaining ignition patterns, particularly in regions experiencing rapid demographic expansion. Moreover, the geographic distribution of the research constitutes a limitation, as there is a strong concentration of studies from the Northern Hemisphere (United States, China, Europe) and a marked underrepresentation of work from South America within English-language journals indexed in WoS/Scopus. This methodological limitation could influence the representation of the region in relation to the phenomenon studied, potentially altering (or not) the perceived weight of South America in the global patterns identified.

Furthermore, a lack of comparative metrics (e.g., weighted proportions, meta-analytic approaches) limits the possibility of establishing the magnitude of influence that each factor exerts on fire occurrence and spread. In addition, a considerable proportion of studies show conceptual ambiguity when using terms such as occurrence, spread, factors, and causes, which could introduce bias into the interpretation of results. Correlation does not imply causation, and recognizing this limitation is key for improving future analyses.

The use of the PRISMA framework provided a clear and methodologically sound foundation for structuring and organizing the scientific search process. Its systematic workflow facilitated a transparent and replicable selection of studies, reduced potential selection bias, and improved the coherence of the evidence compiled. This strengthened the reliability of the patterns identified in wildfire ignition and spread.

Finally, distinguishing between the concepts of occurrence and spread not only improves scientific understanding of fire dynamics but is also essential for developing more effective public policies. This distinction allows for more precise territorial planning in highly affected areas, particularly in wildland–urban interface (WUI) areas, and for enhancing early warning systems. While human activity is the main cause of ignition, climatic conditions play a determining role in the way fires spread and intensify. Therefore, prevention efforts must focus on both controlling ignition sources and managing landscape flammability. By incorporating this conceptual clarification into fire management, through actions such as vegetation control, creation of firebreaks, and restoration with less flammable species, it will be possible to reduce not only the extent of fires but also their ecological, economic, and social consequences. Facing the challenges of global change will require integrated predictive models that jointly consider climatic, ecological, and anthropogenic factors.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/fire9010023/s1, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist [110].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.T.-O., A.F.-R. and A.A.; Methodology, O.T.-O. and A.F.-R.; Validation, O.T.-O.; formal analysis, O.T.-O.; Investigation, A.F.-R., M.B. and A.G.; Writing—original draft preparation, O.T.-O.; writing—review and editing, O.T.-O., A.F.-R., A.A., A.G., M.B., V.F. and Á.G.-F.; Supervision, A.F.-R.; Project administration, A.F.-R.; Funding acquisition, A.F.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

OTO is funded by ANID Doctoral Scholarship 21240592. This research is part of the Red Firewall initiative (ANID grant AMSUD 240053 and ANID FOVI 220101). Research was partially funded by ANID FONDECYT Regular 1241295. AFR and OTO thank the support received from Centro ANID Basal CENAMAD (FB210015).

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available upon request to the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Total list of articles analyzed in the review analysis.

Table A1.

Total list of articles analyzed in the review analysis.

| N | Title | Author | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A Review of the Occurrence and Causes for Wildfires and Their Impacts on the Geoenvironment | Farid et al. | 2024 |

| 2 | Assessing the Link between Wildfires, Vulnerability, and Climate Change: Insights from the Regions of Greece | Xepapadeas et al. | 2024 |

| 3 | Characterizing the occurrence of wildland-urban interface fires and their important factors in China | Gong et al. | 2024 |

| 4 | Igniting lightning, wildfire occurrence, and precipitation in the boreal forest of northeast China | Gao et al. | 2024 |

| 5 | Integrating meteorological and geospatial data for forest fire risk assessment | Parvar et al. | 2024 |

| 6 | Land and Atmosphere Precursors to Fuel Loading, Wildfire Ignition and Post-Fire Recovery | Alizadeh et al. | 2024 |

| 7 | Modelling the daily probability of wildfire occurrence in the contiguous United States | Keeping et al. | 2024 |

| 8 | Prediction and driving factors of forest fire occurrence in Jilin Province, China | Gao et al. | 2024 |

| 9 | Research Trends in Wildland Fire Prediction Amidst Climate Change: A Comprehensive Bibliometric Analysis | Bao et al. | 2024 |

| 10 | Spatial and temporal patterns of forest fires in the Central Monte: relationships with regional climate | Villagra et al. | 2024 |

| 11 | Spatio-temporal feature of active fire occurrence on the loess plateau from 2001 to 2020 based on modis | Zheng et al. | 2024 |

| 12 | The global drivers of wildfire | Haas et al. | 2024 |

| 13 | The importance of geography in forecasting future fire patterns under climate change | Syphard et al. | 2024 |

| 14 | Vegetation phenology as a key driver for fire occurrence in the UK and comparable humid temperate regions | Nikonovas et al. | 2024 |

| 15 | Assessment of fire hazard in Southwestern Amazon | Ferreira et al. | 2023 |

| 16 | Climate Change, Forest Fires, and Territorial Dynamics in the Amazon Rainforest: An Integrated Analysis for Mitigation Strategies | Celis et al. | 2023 |

| 17 | Evaluation of the Spatial Distribution of Predictors of Fire Regimes in China from 2003 to 2016 | Su et al. | 2023 |

| 18 | Explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) for interpreting the contributing factors feed into the wildfire susceptibility prediction model | Abdollahi & Pradhan | 2023 |

| 19 | Fire risk modeling: An integrated and data-driven approach applied to Sicily | Marquez Torres et al. | 2023 |

| 20 | Holocene wildfire on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau–witness of abrupt millennial timescale climate events | Hao et al. | 2023 |

| 21 | Integrated wildfire danger models and factors: A review | Zacharakis & Tsihrintzis | 2023 |

| 22 | Lightning-Ignited Wildfires beyond the Polar Circle | Kharuk et al. | 2023 |

| 23 | Mapping the probability of wildland fire occurrence in Central America, and identifying the key factors | Valdez et al. | 2023 |

| 24 | Ongoing climatic change increases the risk of wildfires. Case study: Carpathian spruce forests | Korená Hillayová et al. | 2023 |

| 25 | Prediction of forest fire occurrence in China under climate change scenarios | Shao et al. | 2023 |

| 26 | The Influence of Socioeconomic Factors on Human Wildfire Ignitions in the Pacific Northwest, USA | Reilley et al. | 2023 |

| 27 | Variation of lightning-ignited wildfire patterns under climate change | Perez-Invernon et al. | 2023 |

| 28 | Wildfire Dynamics in Pine Forests of Central Siberia in a Changing Climate | Petrov et al. | 2023 |

| 29 | Analysis of Factors Related to Forest Fires in Different Forest Ecosystems in China | Wu et al. | 2022 |

| 30 | Characterizing Spatial Patterns of Amazon Rainforest Wildfires and Driving Factors by Using Remote Sensing and GIS Geospatial Technologies | Ma et al. | 2022 |

| 31 | Cloud-to-Ground Lightning and Near-Surface Fire Weather Control Wildfire Occurrence in Arctic Tundra | He et al. | 2022 |

| 32 | Forest fire and its key drivers in the tropical forests of northern Vietnam | Trang et al. | 2022 |

| 33 | Future climate change impact on wildfire danger over the Mediterranean: The case of Greece | Rovithakis et al. | 2022 |

| 34 | Future increases in lightning ignition efficiency and wildfire occurrence expected from drier fuels in boreal forest ecosystems of western North America | Hessilt et al. | 2022 |

| 35 | Global and Regional Trends and Drivers of Fire Under Climate Change | Jones et al. | 2022 |

| 36 | Global Wildfire Susceptibility Mapping Based on Machine Learning Models | Shmuel & Heifetz | 2022 |

| 37 | Holocene fire history in southwestern China linked to climate change and human activities | Yuan et al. | 2022 |

| 38 | How Environmental Factors Affect Forest Fire Occurrence in Yunnan Forest Region | Zhu et al. | 2022 |

| 39 | Human Activity Behind the Unprecedented 2020 Wildfire in Brazilian Wetlands (Pantanal) | de Magalhães Neto & Evangelista | 2022 |

| 40 | Joint Analysis of Lightning-Induced Forest Fire and Surface Influence Factors in the Great Xing’an Range | Zhang et al. | 2022 |

| 41 | Modelling ignition probability for human- and lightning-caused wildfires in Victoria, Australia | Dorph et al. | 2022 |

| 42 | Modelling the Effect of Temperature Increments on Wildfires | Razavi et al. | 2022 |

| 43 | Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Climate Influence of Forest Fires in Fujian Province, China | Zeng et al. | 2022 |

| 44 | Study of Driving Factors Using Machine Learning to Determine the Effect of Topography, Climate, and Fuel on Wildfire in Pakistan | Rafaqat et al. | 2022 |

| 45 | The combined role of plant cover and fire occurrence on soil properties reveals response to wildfire in the Mediterranean basin | Memoli et al. | 2022 |

| 46 | Tracking Deforestation, Drought, and Fire Occurrence in Kutai National Park, Indonesia | Guild et al. | 2022 |

| 47 | Wildfire Susceptibility Mapping using NBR Index and Frequency Ratio Model | Heidari & Arfania | 2022 |

| 48 | Are climate factors driving the contemporary wildfire occurrence in China? | Lan et al. | 2021 |

| 49 | Assessing the Probability of Wildfire Occurrences in a Neotropical Dry Forest | Campos-Vargas & Vargas-Sanabria | 2021 |

| 50 | Data-based wildfire risk model for Mediterranean ecosystems-case study of the Concepción metropolitan area in central Chile | Jacque Castillo et al. | 2021 |

| 51 | Exploring the multidimensional effects of human activity and land cover on fire occurrence for territorial planning | Carrasco et al. | 2021 |

| 52 | Fifty years of wildland fire science in Canada | Coogan et al. | 2021 |

| 53 | Forest Fire Probability Mapping in Eastern Serbia: Logistic Regression versus Random Forest | Milanovic et al. | 2021 |

| 54 | Forest fire probability under ENSO conditions in a semi-arid region: a case study in Guanajuato | Farfan et al. | 2021 |

| 55 | Observed and estimated consequences of climate change for the fire weather regime in the moist-temperate climate of the Czech Republic | Trnka et al. | 2021 |

| 56 | Robust projections of future fire probability for the conterminous United States | Gao et al. | 2021 |

| 57 | Spatio-temporal analysis of fire occurrence in Australia | Valente & Laurini | 2021 |

| 58 | The changes in species composition mediate direct effects of climate change on future fire regimes of boreal forests in northeastern China | Huang et al. | 2021 |

| 59 | Using Artificial Intelligence to Estimate the Probability of Forest Fires in Heilongjiang, Northeast China | Wu et al. | 2021 |

| 60 | Wildfire response to changing daily temperature extremes in California’s Sierra Nevada | Klimaszewski-Patterson et al. | 2021 |

| 61 | Wildland Fire Susceptibility Mapping Using Support Vector Regression and Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System-Based Whale Optimization Algorithm and Simulated Annealing | Al-Fugara et al. | 2021 |

| 62 | Climate relationships with increasing wildfire in the southwestern US from 1984 to 2015 | Mueller et al. | 2020 |

| 63 | Current and future patterns of forest fire occurrence in China | Wu et al. | 2020 |

| 64 | Identifying Forest Fire Driving Factors and Related Impacts in China Using Random Forest Algorithm | Ma et al. | 2020 |

| 65 | Observed and expected changes in wildfireconducive weather and fire events in peri-urban zones and key nature reserves of the Czech Republic | Trnka et al. | 2020 |

| 66 | The driving factors and their interactions of fire occurrence in Greater Khingan Mountains, China | Guo et al. | 2020 |

| 67 | The Proximal Drivers of Large Fires: A Pyrogeographic Study | Clarke et al. | 2020 |

| 68 | The temporal and spatial relationships between climatic parameters and fire occurrence in northeastern Iran | Eskandari et al. | 2020 |

| 69 | Topography, Climate and Fire History Regulate Wildfire Activity in the Alaskan Tundra | Masrur et al. | 2020 |

| 70 | Wildfire ignition probability in Belgium | Depicker et al. | 2020 |

References

- Bond, W.J.; Woodward, F.I.; Midgley, G.F. The Global Distribution of Ecosystems in a World without Fire. New Phytol. 2005, 165, 525–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, D.M.J.S.; Balch, J.K.; Artaxo, P.; Bond, W.J.; Carlson, J.M.; Cochrane, M.A.; D’Antonio, C.M.; DeFries, R.S.; Doyle, J.C.; Harrison, S.P.; et al. Fire in the Earth System. Science 2009, 324, 481–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubeda, X.; Sarricolea, P. Wildfires in Chile: A Review. Glob. Planet. Change 2016, 146, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrutia-Jalabert, R.; González, M.E.; González-Reyes, Á.; Lara, A.; Garreaud, R. Climate Variability and Forest Fires in Central and South-Central Chile. Ecosphere 2018, 9, e02171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, M.P.; Stephens, S.L.; Collins, B.M.; Agee, J.K.; Aplet, G.; Franklin, J.F.; Fulé, P.Z. Reform Forest Fire Management: Agency Incentives Undermine Policy Effectiveness. 2015. Available online: https://fusee.org/efmdatabase/reform-forest-fire-management-agency-incentives-undermine-policy-effectiveness-north-et-al-2015 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Pausas, J.G.; Keeley, J.E.; Schwilk, D.W. Flammability as an Ecological and Evolutionary Driver. J. Ecol. 2017, 105, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo-Vargas, P.; Holz, A.; Veblen, T.T. Fire Effects on Diversity Patterns of the Understory Communities of Araucaria-Nothofagus Forests. Plant Ecol. 2022, 223, 883–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almonacid-Muñoz, L.; Herrera, H.; Fuentes-Ramírez, A.; Vargas-Gaete, R.; Toy-Opazo, O.; de Oliveira Costa, P.H.; da Silva Valadares, R.B. What Fire Didn’t Take Away: Plant Growth-Promoting Microorganisms in Burned Soils of Old-Growth Nothofagus Forests in Los Andes Cordillera. Plant Soil 2024, 507, 655–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pausas, J.G.; Keeley, J.E. Evolutionary Fire Ecology: An Historical Account and Future Directions. BioScience 2023, 73, 602–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pausas, J.G. Bark Thickness and Fire Regime. Funct. Ecol. 2015, 29, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, F.; Ascoli, D.; Safford, H.; Adams, M.A.; Moreno, J.M.; Pereira, J.M.C.; Catry, F.X.; Armesto, J.; Bond, W.; González, M.E.; et al. Wildfire Management in Mediterranean-Type Regions: Paradigm Change Needed. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 011001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mediterranean-Type Climate Ecosystems and Fire. In Fire in Mediterranean Ecosystems: Ecology, Evolution and Management; Keeley, J.E., Bond, W.J., Bradstock, R.A., Pausas, J.G., Rundel, P.W., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 3–29. ISBN 978-0-521-82491-0. [Google Scholar]

- Westerling, A.L.; Hidalgo, H.G.; Cayan, D.R.; Swetnam, T.W. Warming and Earlier Spring Increase Western U.S. Forest Wildfire Activity. Science 2006, 313, 940–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapin, F.S., III; Trainor, S.F.; Huntington, O.; Lovecraft, A.L.; Zavaleta, E.; Natcher, D.C.; McGuire, A.D.; Nelson, J.L.; Ray, L.; Calef, M.; et al. Increasing Wildfire in Alaska’s Boreal Forest: Pathways to Potential Solutions of a Wicked Problem. Bioscience 2008, 58, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeley, J.E.; Syphard, A.D. Climate Change and Future Fire Regimes: Examples from California. Geosciences 2016, 6, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, N.J.; Dunfield, K.E.; Johnstone, J.F.; Mack, M.C.; Turetsky, M.R.; Walker, X.J.; White, A.L.; Baltzer, J.L. Wildfire Severity Reduces Richness and Alters Composition of Soil Fungal Communities in Boreal Forests of Western Canada. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 25, 2310–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reszka, P.; Fuentes, A. The Great Valparaiso Fire and Fire Safety Management in Chile. Fire Technol. 2015, 51, 753–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavorel, S.; Flannigan, M.D.; Lambin, E.F.; Scholes, M.C. Vulnerability of Land Systems to Fire: Interactions among Humans, Climate, the Atmosphere, and Ecosystems. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 2007, 12, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syphard, A.D.; Radeloff, V.C.; Hawbaker, T.J.; Stewart, S.I. Conservation Threats Due to Human-Caused Increases in Fire Frequency in Mediterranean-Climate Ecosystems. Conserv. Biol. 2009, 23, 758–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasilla, D.F.; García-Codron, J.C.; Carracedo, V.; Diego, C. Circulation Patterns, Wildfire Risk and Wildfire Occurrence at Continental Spain. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2010, 35, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, G.C.L.; Prince, S.E.; Rappold, A.G. Trends in Fire Danger and Population Exposure along the Wildland-Urban Interface. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 16257–16265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvino-Cancela, M.; Chas-Amil, M.L.; Garcia-Martinez, E.D.; Touza, J. Wildfire Risk Associated with Different Vegetation Types within and Outside Wildland-Urban Interfaces. For. Ecol. Manag. 2016, 372, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganteaume, A.; Barbero, R.; Jappiot, M.; Maillé, E. Understanding Future Changes to Fires in Southern Europe and Their Impacts on the Wildland-Urban Interface. J. Saf. Sci. Resil. 2021, 2, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappaz, F.; Ganteaume, A. Role of Land-Cover and WUI Types on Spatio-Temporal Dynamics of Fires in the French Mediterranean Area. Risk Anal. 2023, 43, 1032–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radeloff, V.C.; Helmers, D.P.; Kramer, H.A.; Mockrin, M.H.; Alexandre, P.M.; Bar-Massada, A.; Butsic, V.; Hawbaker, T.J.; Martinuzzi, S.; Syphard, A.D.; et al. Rapid Growth of the US Wildland-Urban Interface Raises Wildfire Risk. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 3314–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, F.; Espinoza, L.; Vidal, V.; Carmona, C.; Krecl, P.; Targino, A.C.; Ruggeri, M.F.; Toledo, M. Black Carbon and Particulate Matter Concentrations amid Central Chile’s Extreme Wildfires. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 951, 175541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, D.M.J.S.; Moreira-Muñoz, A.; Kolden, C.A.; Chávez, R.O.; Muñoz, A.A.; Salinas, F.; González-Reyes, Á.; Rocco, R.; de la Barrera, F.; Williamson, G.J.; et al. Human–Environmental Drivers and Impacts of the Globally Extreme 2017 Chilean Fires. Ambio 2019, 48, 350–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, C.E.; Brauer, M.; Johnston, F.H.; Jerrett, M.; Balmes, J.R.; Elliott, C.T. Critical Review of Health Impacts of Wildfire Smoke Exposure. Environ. Health Perspect. 2016, 124, 1334–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, W.; Emmons, L.K.; Wiedinmyer, C.; Partha, D.B.; Huang, Y.; He, C.; Zhang, J.; Barsanti, K.C.; Gaubert, B.; Jo, D.S.; et al. Disproportionately Large Impacts of Wildland-Urban Interface Fire Emissions on Global Air Quality and Human Health. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadr2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, M.B.; Silman, M.R.; McMichael, C.; Saatchi, S. Fire, Climate Change and Biodiversity in Amazonia: A Late-Holocene Perspective. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2008, 363, 1795–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, A.M.; Chin, A.; Simon, G.L.; Briles, C.; Hogue, T.S.; O’Dowd, A.P.; Gerlak, A.K.; Albornoz, A.U. Wildfire, Water, and Society: Toward Integrative Research in the “Anthropocene”. Anthropocene 2016, 16, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celis, N.; Casallas, A.; Lopez-Barrera, E.A.; Felician, M.; De Marchi, M.; Pappalardo, S.E. Climate Change, Forest Fires, and Territorial Dynamics in the Amazon Rainforest: An Integrated Analysis for Mitigation Strategies. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2023, 12, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, J.; Acuna, M.; Miranda, A.; Alfaro, G.; Pais, C.; Weintraub, A. Exploring the Multidimensional Effects of Human Activity and Land Cover on Fire Occurrence for Territorial Planning. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 297, 113428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvino-Cancela, M.; Canizo-Novelle, N. Human Dimensions of Wildfires in NW Spain: Causes, Value of the Burned Vegetation and Administrative Measures. PeerJ 2018, 6, e5657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, K.C.; Christie, F.; York, A. Global Climate Change and Litter Decomposition: More Frequent Fire Slows Decomposition and Increases the Functional Importance of Invertebrates. Glob. Change Biol. 2009, 15, 2958–2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, B.R.; Hardstaff, L.K.; Phillips, M.L. Differences in Leaf Flammability, Leaf Traits and Flammability-Trait Relationships between Native and Exotic Plant Species of Dry Sclerophyll Forest. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e79205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riis, T.; Kelly-Quinn, M.; Aguiar, F.C.; Manolaki, P.; Bruno, D.; Bejarano, M.D.; Clerici, N.; Fernandes, M.R.; Franco, J.C.; Pettit, N.; et al. Global Overview of Ecosystem Services Provided by Riparian Vegetation. BioScience 2020, 70, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farid, A.; Alam, M.K.; Goli, V.S.N.S.; Akin, I.D.; Akinleye, T.; Chen, X.; Cheng, Q.; Cleall, P.; Cuomo, S.; Foresta, V.; et al. A Review of the Occurrence and Causes for Wildfires and Their Impacts on the Geoenvironment. Fire 2024, 7, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, M.E.; Gomez-Gonzalez, S.; Lara, A.; Garreaud, R.; Diaz-Hormazabal, I. The 2010-2015 Megadrought and Its Influence on the Fire Regime in Central and South-Central Chile. Ecosphere 2018, 9, e02300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, D.; Sun, L.; Hu, T. Characterizing the Occurrence of Wildland-Urban Interface Fires and Their Important Factors in China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 165, 112179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte, S.; Miller, K.A. Wildfire Risk and Climate Change: The Influence on Homeowner Mitigation Behavior in the Wildland–Urban Interface. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2010, 23, 417–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, S.D.; Dixon, K.W.; Hopper, S.D.; Lambers, H.; Turner, S.R. Little Evidence for Fire-Adapted Plant Traits in Mediterranean Climate Regions. Trends Plant Sci. 2011, 16, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castilla-Beltran, A.; de Nascimento, L.; Fernandez-Palacios, J.M.; Whittaker, R.J.; Romeiras, M.M.; Cundy, A.B.; Edwards, M.; Nogue, S. Effects of Holocene Climate Change, Volcanism and Mass Migration on the Ecosystem of a Small, Dry Island (Brava, Cabo Verde). J. Biogeogr. 2021, 48, 1392–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrotta, T.; Gobet, E.; Schworer, C.; Beffa, G.; Butz, C.; Henne, P.D.; Morales-Molino, C.; Pasta, S.; van Leeuwen, J.F.N.; Vogel, H.; et al. 8000 Years of Climate, Vegetation, Fire and Land-Use Dynamics in the Thermo-Mediterranean Vegetation Belt of Northern Sardinia (Italy). Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 2021, 30, 789–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, S.; Wang, X.; Park, T.; Chen, C.; Lian, X.; He, Y.; Bjerke, J.W.; Chen, A.; Ciais, P.; Tømmervik, H.; et al. Characteristics, Drivers and Feedbacks of Global Greening. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.W.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Veraverbeke, S.; Andela, N.; Lasslop, G.; Forkel, M.; Smith, A.J.P.; Burton, C.; Betts, R.A.; van der Werf, G.R.; et al. Global and Regional Trends and Drivers of Fire Under Climate Change. Rev. Geophys. 2022, 60, e2020RG000726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWethy, D.B.; Pauchard, A.; Garcia, R.A.; Holz, A.; Gonzalez, M.E.; Veblen, T.T.; Stahl, J.; Currey, B. Landscape Drivers of Recent Fire Activity (2001–2017) in South-Central Chile. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0201195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbero, R.; Curt, T.; Ganteaume, A.; Maillé, E.; Jappiot, M.; Bellet, A. Simulating the Effects of Weather and Climate on Large Wildfires in France. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2019, 19, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balch, J.K.; Bradley, B.A.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Nagy, R.C.; Fusco, E.J.; Mahood, A.L. Human-Started Wildfires Expand the Fire Niche across the United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 2946–2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WWF. Fires, Forests and the Future: A Crisis Raging out of Control? WWF/Boston Consulting Group: Boston, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Loope, W.L.; Anderton, J.B. Human vs. Lightning Ignition of Presettlement Surface Fires in Coastal Pine Forests of the Upper Great Lakes. Am. Midl. Nat. 1998, 140, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharuk, V.I.I.; Dvinskaya, M.L.L.; Golyukov, A.S.S.; Im, S.T.T.; Stalmak, A.V.V. Lightning-Ignited Wildfires beyond the Polar Circle. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitzberger, T.; Bürgesser, R.E. A Novel Fire Regime Driven by Increased Lightning Activity and Lightning Ignition Efficiency for Northwestern Patagonia, Argentina. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2025, 34, WF25016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Shi, C.; Li, J.; Yuan, S.; Huang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Ma, Q.; Wu, G. Igniting Lightning, Wildfire Occurrence, and Precipitation in the Boreal Forest of Northeast China. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2024, 354, 110081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Li, M.; Wang, B.; Tian, Y.; Quan, Y.; Liu, J. Analysis of Factors Related to Forest Fires in Different Forest Ecosystems in China. Forests 2022, 13, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaque Castillo, E.; Fernández, A.; Fuentes Robles, R.; Ojeda, C.G. Data-Based Wildfire Risk Model for Mediterranean Ecosystems-Case Study of the Concepción Metropolitan Area in Central Chile. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 21, 3663–3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farfan, M.; Dominguez, C.; Espinoza, A.; Jaramillo, A.; Alcantara, C.; Maldonado, V.; Tovar, I.; Flamenco, A. Forest Fire Probability under ENSO Conditions in a Semi-Arid Region: A Case Study in Guanajuato. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021, 193, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.; Pu, R.; Downs, J.; Jin, H. Characterizing Spatial Patterns of Amazon Rainforest Wildfires and Driving Factors by Using Remote Sensing and GIS Geospatial Technologies. Geosciences 2022, 12, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvar, Z.; Saeidi, S.; Mirkarimi, S. Integrating Meteorological and Geospatial Data for Forest Fire Risk Assessment. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 358, 120925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; He, H.S.; Keane, R.E.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Shan, Y. Current and Future Patterns of Forest Fire Occurrence in China. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2020, 29, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafaqat, W.; Iqbal, M.; Kanwal, R.; Song, W. Study of Driving Factors Using Machine Learning to Determine the Effect of Topography, Climate, and Fuel on Wildfire in Pakistan. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, O.; Keeping, T.; Gomez-Dans, J.; Prentice, I.C.; Harrison, S.P. The Global Drivers of Wildfire. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1438262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanović, S.; Marković, N.; Pamučar, D.; Gigović, L.; Kostić, P.; Milanović, S.D. Forest Fire Probability Mapping in Eastern Serbia: Logistic Regression versus Random Forest Method. Forests 2021, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syphard, A.D.; Brennan, T.J.; Rustigian-Romsos, H.; Keeley, J.E. Fire-Driven Vegetation Type Conversion in Southern California. Ecol. Appl. 2022, 32, e2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilley, C.; Crandall, M.S.; Kline, J.D.; Kim, J.B.; de Diego, J. The Influence of Socioeconomic Factors on Human Wildfire Ignitions in the Pacific Northwest, USA. Fire 2023, 6, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Z. The Driving Factors and Their Interactions of Fire Occurrence in Greater Khingan Mountains, China. J. Mt. Sci. 2020, 17, 2674–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Vargas, C.; Vargas-Sanabria, D. Assessing the Probability of Wildfire Occurrences in a Neotropical Dry Forest. Ecoscience 2021, 28, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masrur, A.; Taylor, A.; Harris, L.; Barnes, J.; Petrov, A. Topography, Climate and Fire History Regulate Wildfire Activity in the Alaskan Tundra. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosciences 2022, 127, e2021JG006608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, I.A.; Shushpanov, A.S.; Golyukov, A.S.; Dvinskaya, M.L.; Kharuk, V.I. Wildfire Dynamics in Pine Forests of Central Siberia in a Changing Climate. Contemp. Probl. Ecol. 2023, 16, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depicker, A.; De Baets, B.; Baetens, J.M. Wildfire Ignition Probability in Belgium. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2020, 20, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trang, P.T.; Andrew, M.E.; Chu, T.; Enright, N.J. Forest Fire and Its Key Drivers in the Tropical Forests of Northern Vietnam. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2022, 31, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memoli, V.; Santorufo, L.; Santini, G.; Ruggiero, A.G.; Giarra, A.; Ranieri, P.; Di Natale, G.; Ceccherini, M.T.; Trifuoggi, M.; Barile, R.; et al. The Combined Role of Plant Cover and Fire Occurrence on Soil Properties Reveals Response to Wildfire in the Mediterranean Basin. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2022, 112, 103430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chileen, B.V.; McLauchlan, K.K.; Higuera, P.E.; Parish, M.; Shuman, B.N. Vegetation Response to Wildfire and Climate Forcing in a Rocky Mountain Lodgepole Pine Forest over the Past 2500 Years. Holocene 2020, 30, 1493–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Fan, G.; Feng, Z.; Sun, L.; Yang, X.; Ma, T.; Li, X.; Fu, H.; Wang, A. Prediction of Forest Fire Occurrence in China under Climate Change Scenarios. J. For. Res. 2023, 34, 1217–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, M.R.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Luce, C.H.; Adamowski, J.F.; Farid, A.; Sadegh, M. Warming Enabled Upslope Advance in Western US Forest Fires. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2009717118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zacharakis, I.; Tsihrintzis, V.A. Integrated Wildfire Danger Models and Factors: A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 899, 165704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegeman, E.E.; Dickson, B.G.; Zachmann, L.J. Probabilistic Models of Fire Occurrence across National Park Service Units within the Mojave Desert Network, USA. Landsc. Ecol. 2014, 29, 1587–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, A.A.; Hantson, S.; Langenbrunner, B.; Chen, B.; Jin, Y.; Goulden, M.L.; Randerson, J.T. Wildfire Response to Changing Daily Temperature Extremes in California’s Sierra Nevada. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabe6417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veblen, T.T.; Kitzberger, T.; Raffaele, E.; Mermoz, M.; Conzalez, M.E.; Sibold, J.S.; Holz, A. The Historical Range of Variability of Fires in the Andean-Patagonian Nothofagus Forest Region. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2008, 17, 724–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Loboda, T.V.; Chen, D.; French, N.H.F. Cloud-to-Ground Lightning and Near-Surface Fire Weather Control Wildfire Occurrence in Arctic Tundra. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2022, 49, e2021GL096814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessilt, T.D.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Chen, Y.; Randerson, J.T.; Scholten, R.C.; van der Werf, G.; Veraverbeke, S. Future Increases in Lightning Ignition Efficiency and Wildfire Occurrence Expected from Drier Fuels in Boreal Forest Ecosystems of Western North America. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 054008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorph, A.; Marshall, E.; Parkins, K.A.; Penman, T.D. Modelling Ignition Probability for Human- and Lightning-Caused Wildfires in Victoria, Australia. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2022, 22, 3487–3499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, I.J.M.; Campanharo, W.A.; Barbosa, M.L.F.; da Silva, S.S.; Selaya, G.; Aragão, L.E.O.C.; Anderson, L.O. Assessment of Fire Hazard in Southwestern Amazon. Front. For. Glob. Change 2023, 6, 1107417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Invernon, F.J.; Gordillo-Vazquez, F.J.; Huntrieser, H.; Joeckel, P. Variation of Lightning-Ignited Wildfire Patterns under Climate Change. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Shan, Y.; Liu, X.; Yin, S.; Yu, B.; Cui, C.; Cao, L. Prediction and Driving Factors of Forest Fire Occurrence in Jilin Province, China. J. For. Res. 2024, 35, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, K.; Yao, Q.; Guo, Z.; Zheng, B.; Du, J.; Qi, F.; Yan, P.; Li, J.; Ou, T.; Liu, J.; et al. ENSO Modulates Wildfire Activity in China. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marquez Torres, A.; Signorello, G.; Kumar, S.; Adamo, G.; Villa, F.; Balbi, S. Fire Risk Modeling: An Integrated and Data-Driven Approach Applied to Sicily. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2023, 23, 2937–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xepapadeas, P.; Douvis, K.; Kapsomenakis, I.; Xepapadeas, A.; Zerefos, C. Assessing the Link between Wildfires, Vulnerability, and Climate Change: Insights from the Regions of Greece. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskandari, S.; Miesel, J.R.; Pourghasemi, H.R. The Temporal and Spatial Relationships between Climatic Parameters and Fire Occurrence in Northeastern Iran. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 118, 106720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Z.; Su, Z.; Guo, M.; Alvarado, E.C.; Guo, F.; Hu, H.; Wang, G. Are Climate Factors Driving the Contemporary Wildfire Occurrence in China? Forests 2021, 12, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Homayouni, S.; Yao, H.; Shu, Y.; Li, M.; Zhou, M. Joint Analysis of Lightning-Induced Forest Fire and Surface Influence Factors in the Great Xing’an Range. Forests 2022, 13, 1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, F.; Laurini, M. Spatio-Temporal Analysis of Fire Occurrence in Australia. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2021, 35, 1759–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coogan, S.C.P.; Daniels, L.D.; Boychuk, D.; Burton, P.J.; Flannigan, M.D.; Gauthier, S.; Kafka, V.; Park, J.S.; Wotton, B.M. Fifty Years of Wildland Fire Science in Canada. Can. J. For. Res. 2021, 51, 283–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Terando, A.J.; Kupfer, J.A.; Morgan Varner, J.; Stambaugh, M.C.; Lei, T.L.; Kevin Hiers, J. Robust Projections of Future Fire Probability for the Conterminous United States. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 789, 147872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, H.; Penman, T.; Boer, M.; Cary, G.J.; Fontaine, J.B.; Price, O.; Bradstock, R. The Proximal Drivers of Large Fires: A Pyrogeographic Study. Front. Earth Sci. 2020, 8, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Jin, M.; Mao, J.; Ricciuto, D.M.; Chen, A.; Zhang, Y. Quantifying Wildfire Drivers and Predictability in Boreal Peatlands Using a Two-Step Error-Correcting Machine Learning Framework in TeFire v1.0. Geosci. Model Dev. 2024, 17, 1525–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeping, T.; Harrison, S.P.; Prentice, I.C. Modelling the Daily Probability of Wildfire Occurrence in the Contiguous United States. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 024036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, S.E.; Thode, A.E.; Margolis, E.Q.; Yocom, L.L.; Young, J.D.; Iniguez, J.M. Climate Relationships with Increasing Wildfire in the Southwestern US from 1984 to 2015. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 460, 117861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, A.H.S.; Motlagh, M.S.; Noorpoor, A.; Ehsani, A.H. Modelling the Effect of Temperature Increments on Wildfires. Pollution 2022, 8, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Deng, X.; Zhao, F.; Li, S.; Wang, L. How Environmental Factors Affect Forest Fire Occurrence in Yunnan Forest Region. Forests 2022, 13, 1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, W.; Jiao, K.; Yu, Y.; Li, K.; Lü, Q.; Fletcher, T.L. Evaluation of the Spatial Distribution of Predictors of Fire Regimes in China from 2003 to 2016. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikonovas, T.; Santin, C.; Belcher, C.M.; Clay, G.D.; Kettridge, N.; Smith, T.E.L.; Doerr, S.H. Vegetation Phenology as a Key Driver for Fire Occurrence in the UK and Comparable Humid Temperate Regions. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2024, 33, WF23205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Sun, N.; Luo, F. Spatio-Temporal Feature of Active Fire Occurrence on the Loess Plateau from 2001 to 2020 Based on Modis. Quat. Sci. 2024, 44, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trnka, M.; Balek, J.; Možný, M.; Cienciala, E.; Cermák, P.; Semerádová, D.; Jurecka, F.; Hlavinka, P.; Štepánek, P.; Farda, A.; et al. Observed and Expected Changes in Wildfireconducive Weather and Fire Events in Peri-Urban Zones and Key Nature Reserves of the Czech Republic. Clim. Res. 2020, 82, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trnka, M.; Možný, M.; Jurečka, F.; Balek, J.; Semerádová, D.; Hlavinka, P.; Štěpánek, P.; Farda, A.; Skalák, P.; Cienciala, E.; et al. Observed and Estimated Consequences of Climate Change for the Fire Weather Regime in the Moist-Temperate Climate of the Czech Republic. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2021, 310, 108583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, A.; Yang, S.; Zhu, H.; Tigabu, M.; Su, Z.; Wang, G.; Guo, F. Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Climate Influence of Forest Fires in Fujian Province, China. Forests 2022, 13, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, F.B.; Arfania, R. Wildfire Susceptibility Mapping Using NBR Index and Frequency Ratio Model. Geoconservation Res. 2022, 5, 240–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganteaume, A. Does Plant Flammability Differ between Leaf and Litter Bed Scale? Role of Fuel Characteristics and Consequences for Flammability Assessment. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2018, 27, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toy-Opazo, O.; Fuentes-Ramirez, A.; Palma-Soto, V.; Garcia, R.A.; Moloney, K.A.; Demarco, R.; Fuentes-Castillo, A. Flammability Features of Native and Non-Native Woody Species from the Southernmost Ecosystems: A Review. Fire Ecol. 2024, 20, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMAScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.