1. Introduction

The rapid vertical expansion of urban buildings has increased the complexity of fire safety design, particularly with respect to smoke control in high-rise structures. In such buildings, stairwells represent the primary evacuation routes and critical access paths for firefighters. Their performance during a fire is strongly influenced by smoke propagation, thermal stratification, and pressure distribution, all of which depend on the vertical location of the fire and the ventilation or pressurization strategy applied [

1,

2,

3]. Understanding these coupled phenomena is essential for ensuring adequate evacuation conditions and supporting safe emergency intervention.

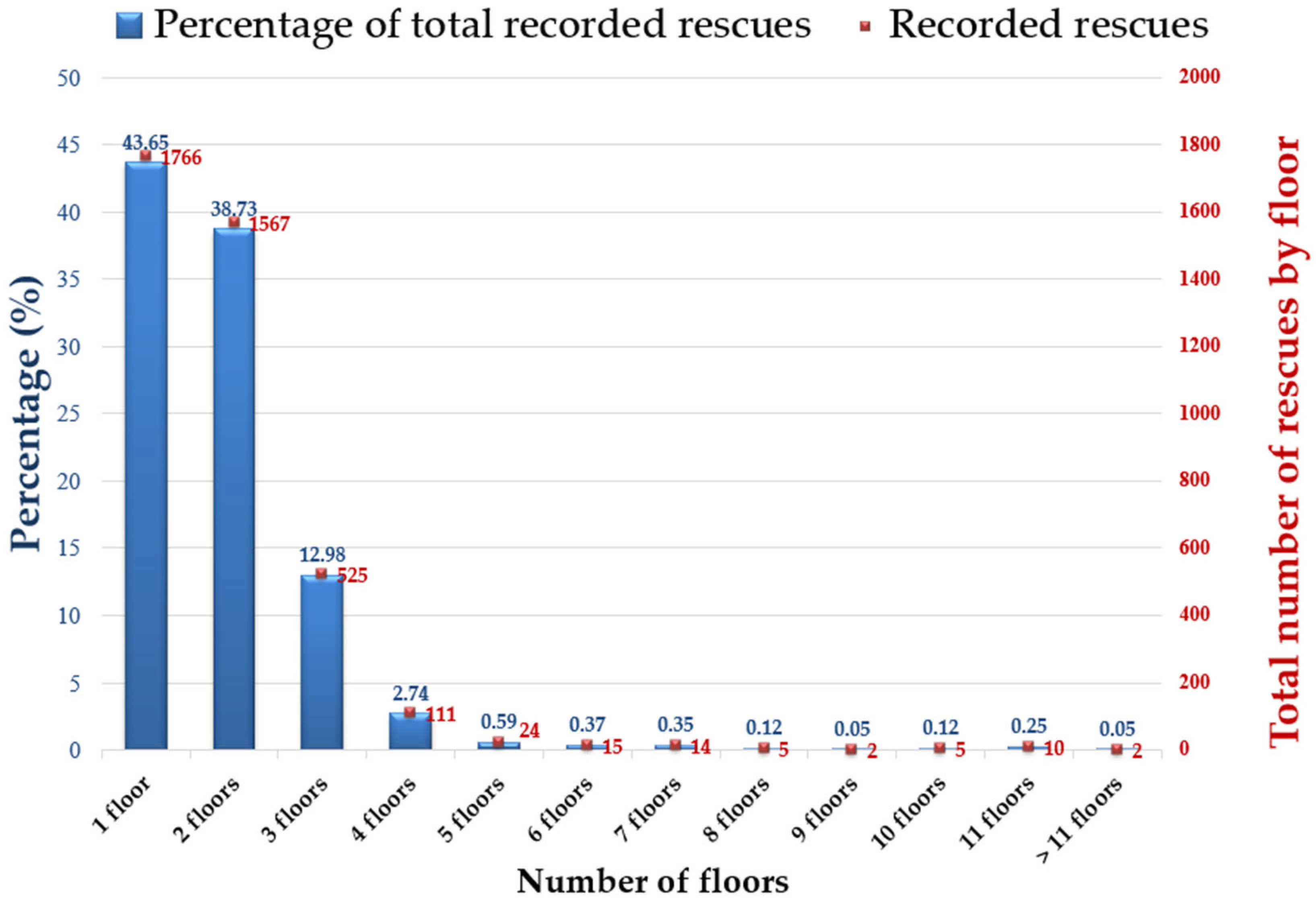

Operational fire statistics further emphasize the importance of stairwell conditions. An analysis of 4046 documented firefighter rescue operations in the United States shows a clear decrease in successful rescues with increasing building height [

4]. While this general trend is expected due to longer access times and severe thermal environments, the data also reveal an anomalous deviation at the 11th floor (

Figure 1), where rescue outcomes deviate from the expected decreasing trend.

The overall decrease in rescues with height reflects increasing access and evacuation times. The local deviation observed at the 11th floor is likely influenced by the limited number of cases, combined with specific building features such as access to roof terraces or protected roof areas, which may temporarily improve survival and rescue conditions; therefore, this variation should be interpreted as statistical scatter rather than a distinct trend.

Previous research has extensively examined smoke movement in stairwells using numerical and experimental approaches. The Fire Dynamics Simulator (FDS) is widely applied to study fire-induced flows, buoyancy-driven smoke transport, and the effectiveness of ventilation systems [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Under natural ventilation conditions, multiple studies have shown that buoyancy forces dominate vertical smoke movement, particularly in stairwells, where the stack effect governs pressure and flow distribution [

10,

11,

12]. In the absence of mechanical ventilation, smoke dynamics are primarily controlled by buoyancy and thermal gradients [

13,

14]. However, many of these studies rely on simplified geometries, fixed fire locations, or configurations that do not reflect the constraints of existing buildings.

Mechanical pressurization, including positive pressure ventilation (PPV), has been proposed as an effective means of limiting smoke ingress into stairwells. Previous investigations indicate that applying overpressure at the building entrance or stairwell base can counteract buoyancy-driven smoke flow, particularly for fires located on lower floors [

15,

16]. Nevertheless, fire development and smoke propagation are also influenced by internal thermal loads, architectural features, and vertical fire location, which can significantly alter the effectiveness of single-point pressurization systems [

17,

18,

19]. As a result, uncertainties remain regarding how natural ventilation and mechanical pressurization compare under realistic conditions and how their performance varies with fire-floor location. Recent work has expanded this understanding by demonstrating that adaptive or hybrid ventilation control can enhance pressure stability and maintain tenability under varying fire conditions [

20,

21]. Other studies have emphasized that combining active and passive smoke management improves performance in existing high-rise buildings [

22], while additional findings show that improper fan placement or uncontrolled leakage rapidly reduces pressurization effectiveness [

23,

24].

The scientific challenge addressed in this study is the comparative evaluation of natural ventilation and mechanical pressurization applied at the lower part of the stairwell, with explicit consideration of fire location along the building height. This work complements existing research by focusing on existing high-rise buildings without smoke exhaust openings at the top of the stairwell, a configuration commonly encountered in the building stock of Bucharest, Romania. In such buildings, stairwell smoke control relies primarily on natural leakage paths or on mechanical pressurization applied at the base, making their comparative assessment particularly relevant.

The motivation of this research is closely linked to emergency response practice. Firefighters operating in high-rise buildings must make rapid decisions regarding access routes, ventilation actions, and evacuation support, often under limited visibility and high thermal stress. A clearer understanding of how smoke and heat propagate in stairwells depending on fire location and ventilation mode can directly improve decision-making during intervention and enhance firefighter safety.

Accordingly, the study addresses the following research questions:

Under natural ventilation, how does the vertical location of the fire source influence temperature, pressure, visibility, and toxic gas levels along the stairwell?

What is the impact of stairwell mechanical pressurization (PPV at the base) on these indoor environmental conditions?

Is the effect of base pressurization consistent across fire-floor locations, or are benefits limited to specific scenarios and fire stages?

Do the results indicate the need for an adaptive or multi-zone pressurization strategy to maintain tenability during fire development?

To answer these questions, three-dimensional FDS simulations were performed for an administrative building with basement + ground floor + nine floors (B + GF + 9F). Two ventilation scenarios were analyzed: S1, natural ventilation without stairwell pressurization (smoke transport governed by buoyancy and infiltration), and S2, mechanical pressurization with a supply fan installed at the stairwell base to maintain positive pressure relative to adjacent spaces.

In each scenario, the fire source was located at three floor levels (F0, F5, and F9), resulting in six simulations (S1-F0, S1-F5, S1-F9, S2-F0, S2-F5, and S2-F9). The analysis focuses on tenability-relevant parameters (temperature, pressure, airflow velocity, visibility, and carbon monoxide concentration) to evaluate stairwell performance and to provide information that can support better-informed firefighter decision-making during intervention in existing high-rise buildings.

2. Experimental Input Data

The present work forms part of a broader research stage in which two full-scale experiments were conducted within a full-scale experimental compartment [

25,

26]. The study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of Positive Pressure Ventilation (PPV) compared with Natural Ventilation in a multi-story residential building.

Given the complexity and considerable dimensions of the studied objective, as well as the nature of the reproduced phenomena, performing a full-scale experiment on an actual building would have been impracticable. Consequently, the research methodology was grounded in a previously conducted experimental study carried out in a full-scale, room-level test compartment with a floor area of 16 m

2. This setup employed a fire source with a total heat load of 6720 MJ, corresponding to a typical office fire according to standard [

27], generated through the combustion of nine wood cribs arranged in a configuration selected for its documented advantages [

28].

2.1. Testing Room and Wood Crib Characteristics

The objective of the experimental stage was to obtain three output datasets intended for use in the numerical phase: the HRR value derived from the mass loss of the fire source under realistic full-scale conditions, the characteristic cell size of the ignition source for the numerical model, and the temporal evolution of air quality parameters. The numerical model developed to replicate the experimental study was constructed using the Fire Dynamics Simulator (FDS), which employs the heat release rate per unit area (HRRPUA), expressed in kW/m2, as the principal input parameter for fire reproduction. Unlike empirical models, FDS does not use temperature, velocity, visibility, or toxic gas concentrations as direct input variables.

To prepare the required wood sticks corresponding to the target heat load, the material was first weighed, then dried for 14 days in a controlled drying chamber, and subsequently arranged inside the experimental compartment, as illustrated in

Figure 2. The configuration of the wood crib was established based on the methodology proposed reference [

29], which also provided a computational tool for estimating the HRR as a function of several user-defined input parameters.

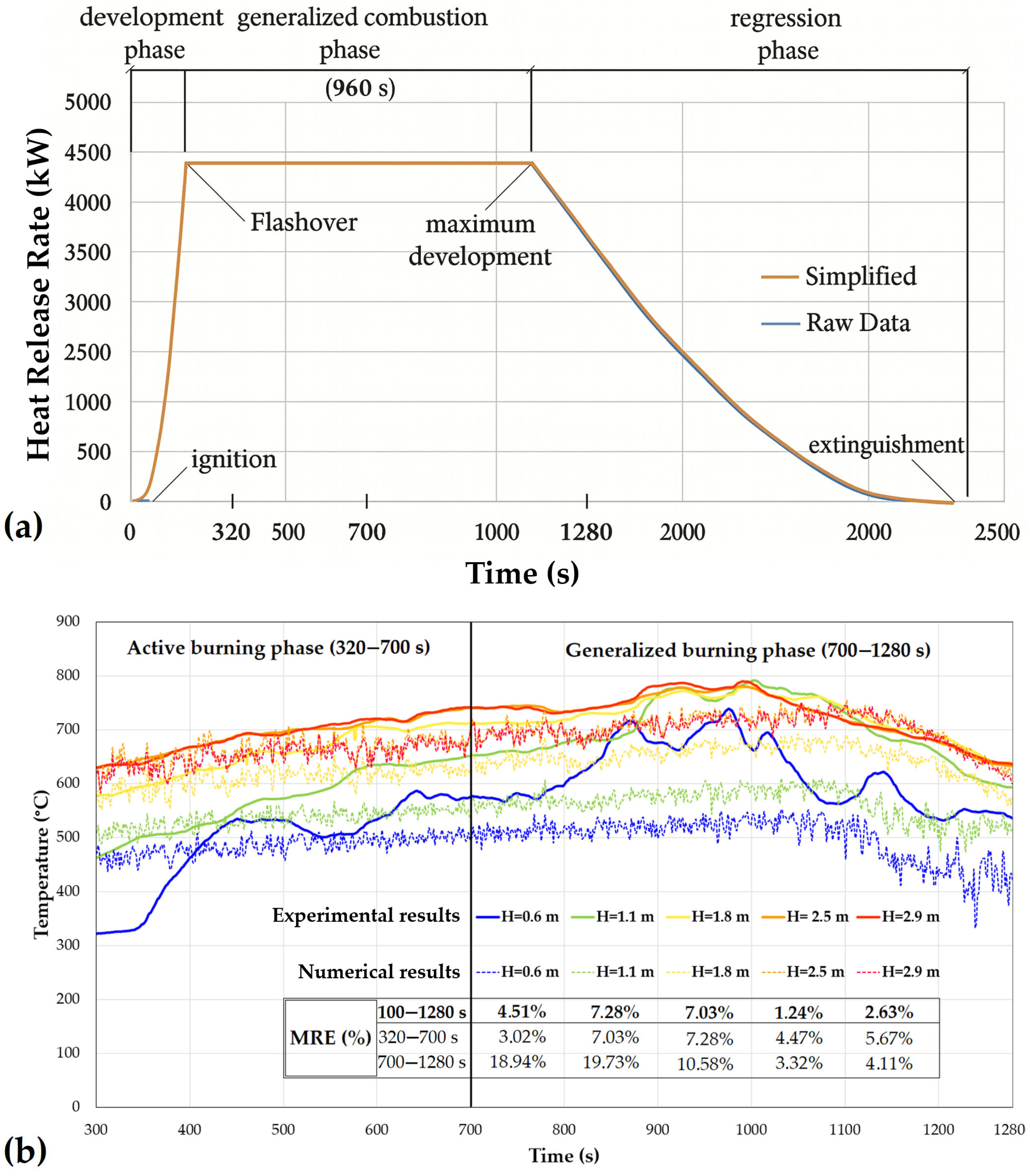

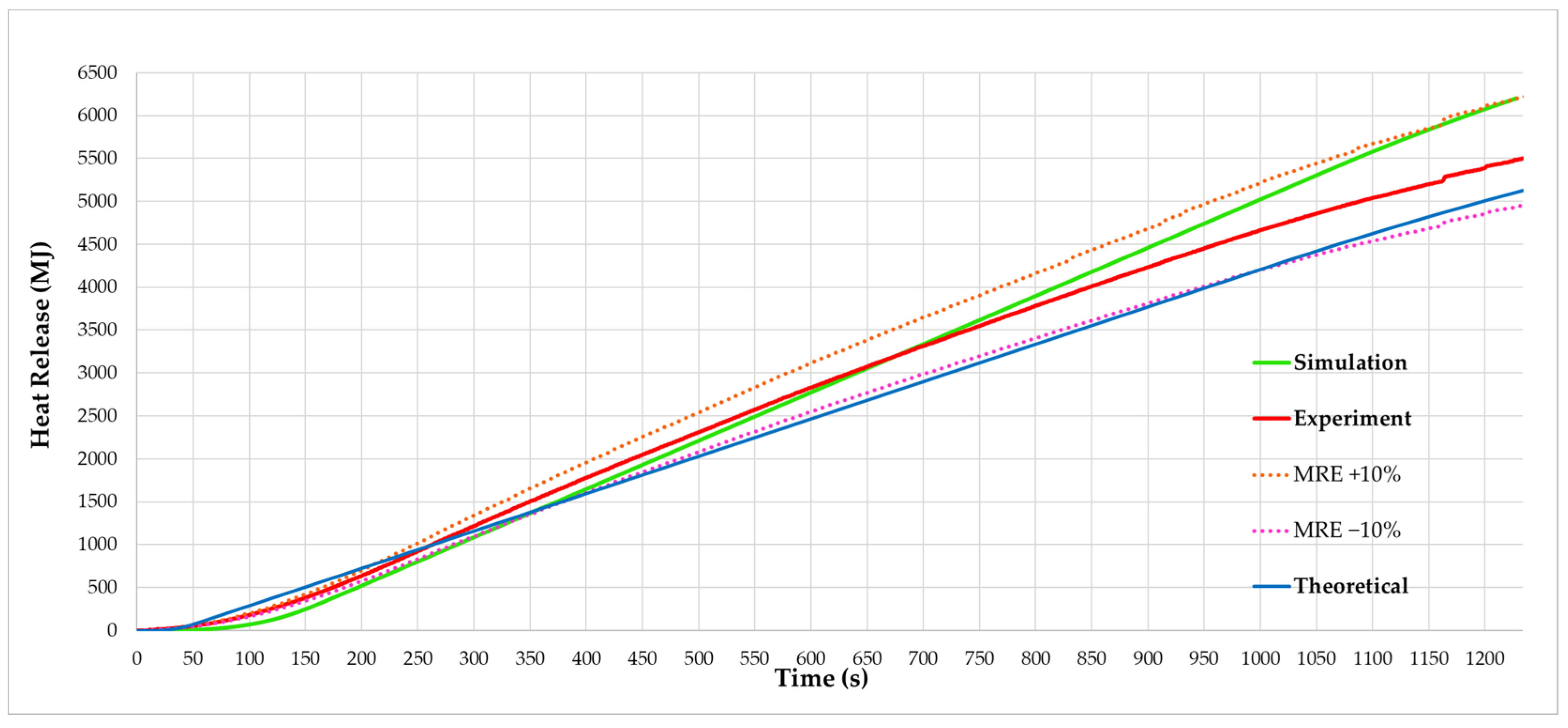

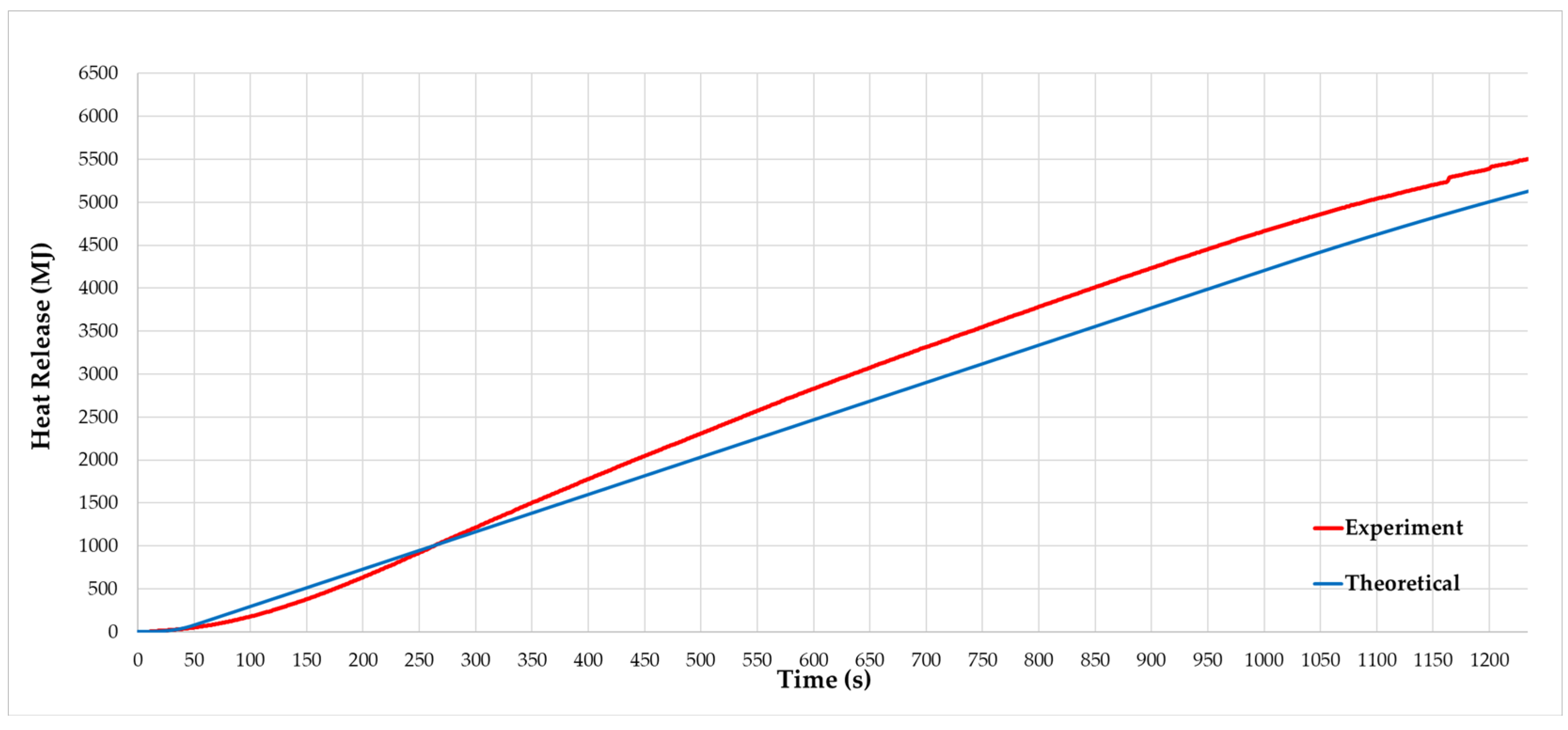

The mass loss measured throughout the experiment enabled the real-time determination of the HRR, given the linear relationship between these two quantities through the calorific value of the fuel. Once the experiment was completed, the theoretical HRR curve generated by the reference model [

29] was compared with the experimentally derived HRR obtained from mass-loss data. (

Figure 3). This comparison indicated an acceptable level of agreement, confirming the practical reliability of the estimation tool.

2.2. Mesh Analysis and HRR Determination Through Mass Loss Rate

The experiment lasted approximately 5 h and was divided into four developmental stages: the slow burning phase (0–320 s), the active burning phase (320–700 s), the generalized burning phase (700–1280 s), and the regression phase (1280–1600 s). However, the interval of primary relevance, during which the peak HRR is also reached, corresponds to the first 0–1280 s. Considering the substantial computational time required for a single simulation and the associated resource demand, a simulation duration of 1280 s was selected. This interval was deemed sufficient to capture the most representative numerical results for the purpose of calibrating the numerical model against the experimental data.

As can also be observed in

Figure 4, the choice of a reduced simulation duration of 360 s for the parametric study was justified by the fact that, within the interval 300–1000 s, the fire enters a phase of relative thermal stability, characterized by limited fluctuations in HRR and temperature. This quasi-steady behavior provides a representative basis for evaluating smoke transport and pressurization performance without the need to reproduce the entire fire duration. Furthermore, considering the large number of simulations initiated within the study (six distinct scenarios), a reasonable simulation time window was required in order to ensure the feasibility of the numerical campaign. Extending the simulation duration to 20–30 min (1200–1800 s) for each case would have significantly hindered the progress of the research.

Even under the selected conditions, a single 360 s simulation using the refined setups described in the following sections required between 10 and 20 days of computational time. Consequently, adopting longer simulation intervals would have rendered the study impractical, leading to excessive computational demands and an unjustified consumption of resources relative to the objectives of the investigation.

A defining parameter for any FDS numerical model is mesh refinement. While reducing the cell size generally increases agreement with experimental observations, it also results in a substantial rise in computational time. Therefore, a mesh analysis was required to identify an appropriate compromise between spatial resolution, numerical accuracy, and processing cost.

In the preliminary testing phase, four candidate cell sizes were examined (0.25 m, 0.10 m, 0.05 m, and 0.025 m) in order to understand their computational implications and sensitivity effects. Based on these initial results, the refinement process was later streamlined to two representative resolutions, which were subsequently incorporated into the 23 refinement matrix. Using the available workstation (Intel Core i9-13900K processor, 36 MB cache, up to 5.80 GHz, 32 GB RAM, manufactured by DELL Romania), a 1280 s simulation with a 0.10 m grid required approximately 5 h of processing time.

The objective of the mesh-refinement analysis was to vary three input parameters (domain meshing type, cell size, and total crib surface area) and to evaluate two key output metrics: result precision and computational processing time, as discussed in detail in Chapter 6 of reference [

26]. A total of eight setup configurations were evaluated, and iteration no. 6 demonstrated the most favorable performance, corresponding to a 0.05 m cell size, a multiple-mesh configuration, and a cumulative crib surface area of 40 m

2.

This refinement methodology systematically varied three independent control parameters, the cell size (cm), the crib surface area (m

2, directly dependent on the HRRPUA), and the mesh discretization type, each intentionally reduced to two representative variants. The repeated combinatorial multiplication of these two-option variables (2 × 2 × 2) yielded a total of eight distinct simulation permutations, as reported in

Table 1, which are presented in detail in reference [

26]. The objectives of this refinement process were quantitatively evaluated by monitoring output metrics such as the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and Mean Relative Error (MRE), used to assess result precision in relation to the associated computational cost. This structured 2 × 2 × 2 refinement matrix ensured a balanced comparison of error trends while maintaining full computational tractability [

26].

Accordingly, the refinement analysis incorporated both single-mesh and multiple-mesh discretization strategies, while the cell size was limited to two representative resolutions of 5 cm and 10 cm. This restriction, reduced from the broader mesh intervals commonly explored in the literature, was intentionally adopted to maintain sufficient sensitivity to grid-induced variations while ensuring computational tractability. In parallel, the crib surface area was varied between 40 m

2, representing the cumulative exposed surface of all wooden elements, and 80 m

2, an approximation of the average effective burning surface throughout the fire development, corresponding to roughly half of the maximum exposed area. The resulting configuration space formed the basis of the error-quantification matrix, enabling a systematic assessment of the model’s sensitivity across the selected meshing and burning-surface parameters. The analysis revealed a MRE of only 5.04% and an RMSE of 210 kW, both values fully compliant with the initial accuracy requirements [

26].

The comprehensive validation of the numerical fire model was based on a rigorous comparison between the simulation output and the empirical experimental data. The HRR (

Figure 5) served as the primary reference parameter for assessing model fidelity, while temperature fields and toxic gas concentrations were used as secondary indicators to characterize vertical gradients and transient phases of the fire development. Prior to the core simulation campaign, a detailed domain-refinement analysis was carried out to optimize the trade-off between solution precision and computational efficiency.

2.3. Experimental Results

To support a comprehensive assessment of the fire dynamics and ventilation performance, the numerical model was configured to systematically monitor the key parameters governing smoke propagation and fire evolution. Within the numerical model, a detailed monitoring of the main fire-related and ventilation-efficiency parameters was performed, namely temperature, velocity, visibility, and gas concentrations (CO, CO

2, and O

2), using both spatial distributions on monitoring planes and discrete point measurements. To this end, three horizontal monitoring planes (

Figure 6), one transverse plane, and one longitudinal plane were implemented to capture the three-dimensional distribution of the analyzed parameters and to highlight thermal stratification phenomena and smoke propagation patterns. In addition, monitoring points were defined to record the local temporal evolution of the parameters, with the corresponding temperature values already illustrated in

Figure 4b in the form of time-history curves. This combined monitoring strategy enabled a comprehensive assessment of both the global fire dynamics and the critical local variations.

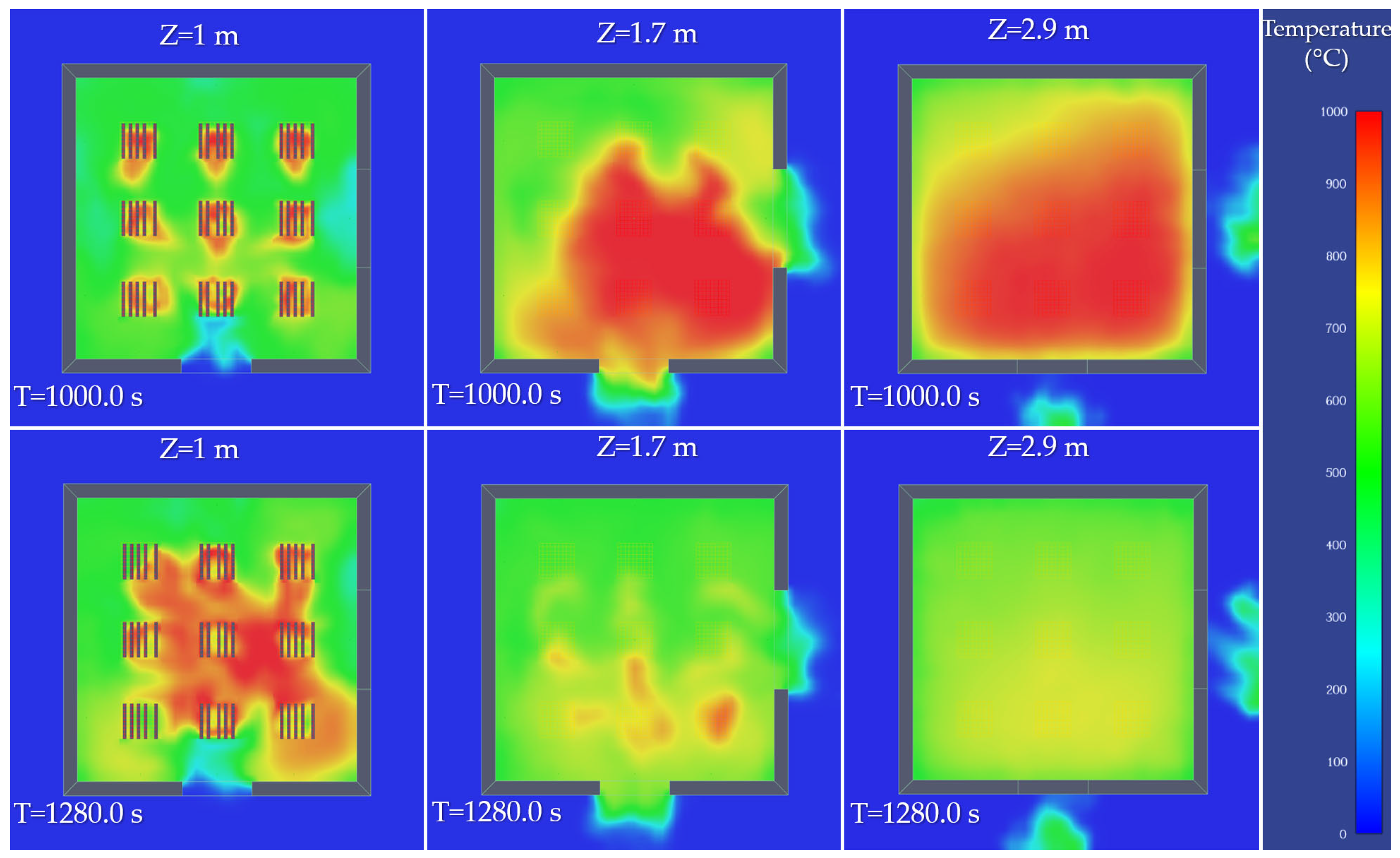

Figure 6 presents the horizontal temperature fields at three characteristic height levels (Z = 1.0 m, 1.7 m, and 2.9 m) within the compartment at two representative time instants, T = 1000 s and T = 1280 s. At T = 1000 s, corresponding to the fully developed fire stage, a pronounced thermal stratification is evident. The upper layer (Z = 2.9 m) is uniformly dominated by high temperatures exceeding 700–800 °C, indicating the accumulation of hot combustion gases. At the intermediate level (Z = 1.7 m), elevated but spatially non-uniform temperatures reflect partial mixing and stratified gas layering. Near the floor (Z = 1.0 m), localized high-temperature regions associated with the wood cribs are clearly defined, accompanied by cooler inflow air entering through the lower exterior opening.

By T = 1280 s, a marked reduction in temperature is observed across all height levels, signifying the transition toward a stagnation and decay phase of the fire. The dissipation of the upper hot gas layer and the attenuation of heat release at the crib level indicate a progressive limitation of the combustion process, primarily driven by reduced oxygen availability. Together, these horizontal temperature fields effectively capture the vertical thermal evolution of the fire and provide critical insight into ventilation effectiveness, stratification behavior, and spatial variations in thermal hazard within the compartment.

3. Development of the Model and Calibration of Its Parameters

3.1. Geometric Modelling and Ventilation Configuration

To rigorously investigate smoke distribution and pressurization performance during a fire event, a detailed geometric model of an administrative building (B + GF + 9F) was developed. This modeling stage is essential for understanding the complex phenomena that occur in vertical evacuation spaces, particularly in the stairwell, where smoke control becomes critical in the absence of natural lighting and direct ventilation [

30]. In line with this objective, the interior was intentionally modeled without furniture or small-scale obstructions, as such elements would not be properly resolved under the global mesh size required for a building of this scale and would not contribute meaningfully to the accuracy of the pressurization analysis. Moreover, stairwells and evacuation routes in real buildings are legally required to remain free of furniture, which supports the decision to exclude such items from the numerical model. Including detailed furnishings would therefore not only be computationally inefficient but would also reduce the representativeness of the evacuation pathways under actual regulatory and operational conditions. In contrast to approaches commonly reported in the literature [

20], which consider stairwell pressurization through air injection at multiple points, the present study focuses on existing buildings where the installation of extended duct networks is limited by major structural constraints.

Therefore, the proposed methodology was structured around two operational scenarios:

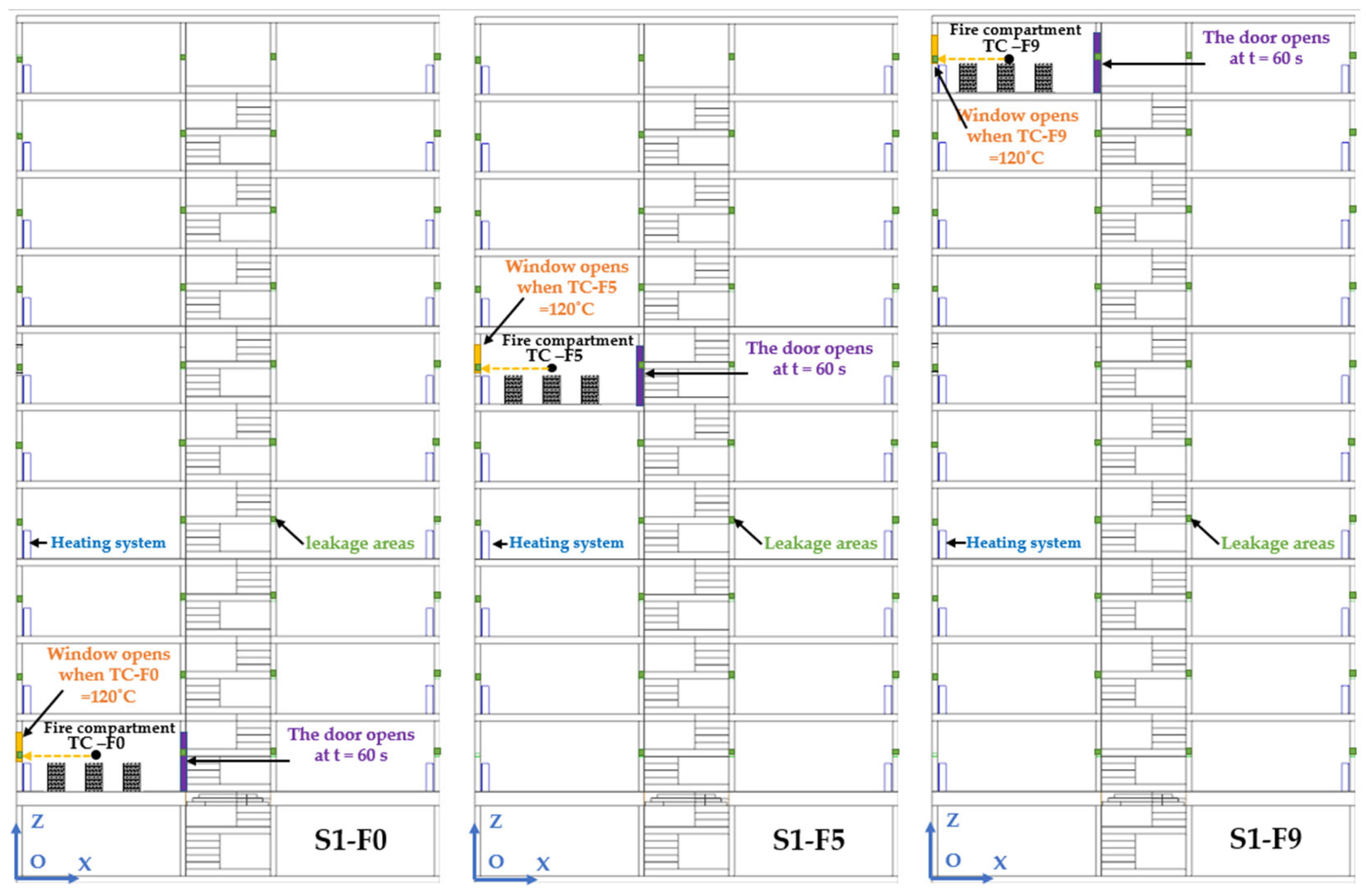

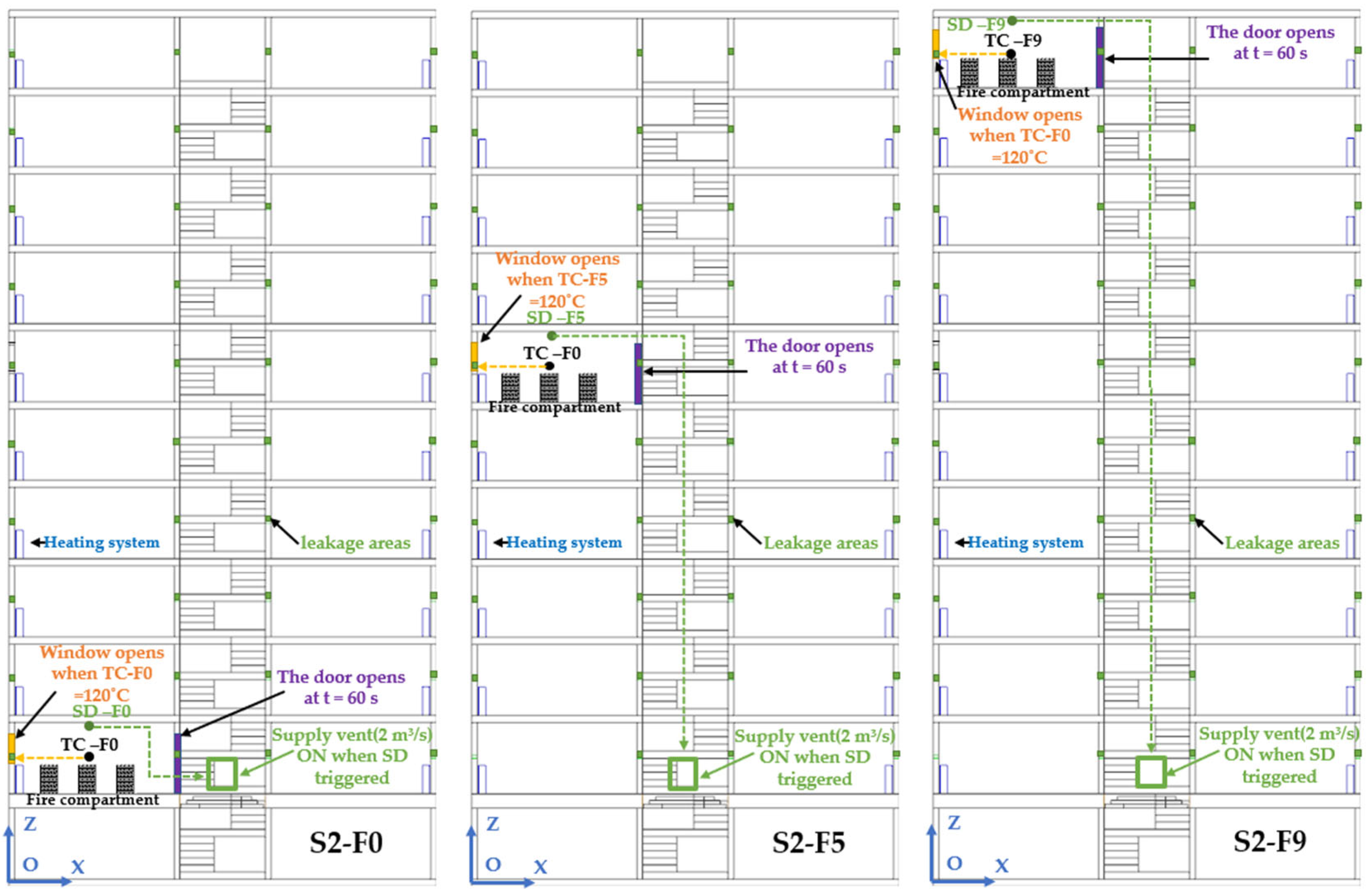

Scenario S1 (

Figure 7): a configuration without mechanical pressurization of the stairwell. The building has a height configuration of B + GF + 9F building and the stairwell is fully enclosed, with no openings to the exterior, except for infiltration surfaces resulting from building permeability. Within this scenario, the fire source is placed successively in three distinct locations: at the ground floor level (S1-F0), at the fifth floor (S1-F5), and at the ninth floor (S1-F9). These configurations ensure complete vertical coverage of the building structure and provide a consistent basis for subsequent comparative analysis.

Scenario S2 (

Figure 8): this configuration uses the same building geometry as Scenario S1 but incorporates a mechanical stairwell pressurization system operated by a fan installed at the ground floor level. As in the previous scenario, the fire source is defined at three vertical positions: S2-F0 (ground floor), S2-F5 (fifth floor), and S2-F9 (ninth floor). The spatial configuration of the stairwell, door locations, simulation conditions, and vertical floor distribution are kept identical to ensure controlled comparability between the two scenarios.

Maintaining effective pressurization in the stairwells of high-rise buildings requires not only systems capable of compensating for vertical pressure differences but also the integration of automated mechanisms for fire-door control, such as electromechanical closing devices or adjustable dampers. These components enable real-time adjustment of door positions and help sustain a stable and adaptive pressure regime throughout the entire emergency event [

31,

32].

The model used in this study is based on an architectural layout commonly found in multi-story buildings, featuring a central stairwell and two open compartments on each floor. This configuration represents a realistic situation in which interior doors typically remain open, eliminating the need for additional compartmentalization. The selected geometry aims to accurately capture the essential phenomena of smoke propagation and ventilation behavior without resorting to highly detailed modeling that would significantly increase computational cost. This approach provides an optimal balance between simulation accuracy and numerical efficiency. Its reliability is supported by previous research [

6,

7], which has demonstrated the model’s capability to reproduce critical effects such as vertical thermal stack effect and differential pressure development within the building.

To ensure the relevance of the simulations with respect to real fire scenarios, the modeling conditions were defined in accordance with the provisions of standards EN 12101-6 [

33] and EN 12101-13 [

34], which establish the technical reference framework for differential pressurization control systems, as follows:

Scenario S2: Positive pressurization was applied exclusively within the stairwell using a 1 m × 1 m axial fan installed at the ground floor. This design choice reflects the building’s configuration, where access to the fire compartment is made directly from the stairwell without intermediate buffer zones.

In the compartment containing the fire source, a 1.40 m × 1.00 m exterior window was introduced and modeled as a thermally activated vent. Although the activation temperature was set at 120 °C, this value was not intended to represent a thermally induced glass-breakage threshold such as those reported in reference [

35], where failure typically requires surface temperatures around 447 °C or incident heat fluxes near 35 kW/m

2. Instead, the chosen trigger reflects a mechanically driven opening mechanism, which is more consistent with real-scale fire behavior, where windows often fail due to differential thermal expansion between the PVC frame and the glazed surface, causing deformation and loss of structural support well before thermal cracking criteria are reached [

35]. The 120 °C threshold therefore serves as a pragmatic approximation of the earliest plausible moment at which mechanically induced window opening may occur under the high fire load considered in this study. Incorporating this dynamic vent condition allows the model to more accurately represent smoke movement, pressure equalization, and heat transfer during the fire, particularly under natural ventilation conditions, while preserving the comparative validity of the analyzed scenarios regardless of the exact activation point [

36].

Fire-compartment door opening: For all three fire-source positions analyzed in both scenarios, ground floor (F0), fifth floor (F5), and ninth floor (F9), it was assumed that the fire-compartment door opened 60 s after ignition, representing the initial evacuation of occupants. Once opened, the door remained fully open throughout the simulation to reflect conditions typical of firefighter intervention. All other doors providing direct access to the stairwell were kept closed to maintain airflow control and assess pressurization performance.

Pressure differentials: The pressure difference between the stairwell and adjacent spaces, as defined by EN 12101-6 [

33], is acceptable within a range of 50 ± 10 Pa, which is considered optimal for preventing smoke ingress into evacuation routes. However, recent studies [

37] indicate that exceeding these values, especially in tightly sealed buildings or under high mechanical ventilation rates, can create hazardous pressure regimes that impede evacuation and firefighter access. Accurate configuration of ventilation parameters is therefore essential to ensure both numerical reliability and physical validity of the simulated scenarios.

Overpressure vents: To avoid compromising the simulated pressure behavior, the model did not include over-pressure vent openings. In PyroSim, enabling this feature reduces overpressure and may degrade the realism of the simulated phenomena. Thus, excluding this option was an intentional decision to ensure a more faithful representation of the pressure dynamics within the analyzed space [

7].

Envelope leakage: To account for air leakage through the building envelope, equivalent openings with an area of 0.01 m

2 (0.10 m × 0.10 m) were introduced on each floor, representing cumulative infiltration through window and door frames in compartments adjacent to the exterior façade. This approach allowed realistic simulation of passive airflow through leaks without increasing geometric complexity [

6].

Mechanical air supply: Differential pressure in the analyzed configuration was generated by mechanical air supply at the base of the stairwell, with a constant flow rate of 2 m

3/s. The airflow prescribed at the stairwell inlet was chosen to satisfy the pressure-differential requirement of approximately 50–60 Pa defined in EN 12101-6 for pressurized escape routes. Under the assumed leakage conditions, this flow rate ensures that the stairwell remains positively pressurized with respect to adjacent spaces, in compliance with the standard [

33]. Considering the building’s infiltration characteristics, these conditions cannot be achieved simultaneously without significant configuration adjustments. Therefore, the scenario was tested in three variants, varying only the fire-source position at the ground floor, fifth floor, and ninth floor, to evaluate system performance in relation to vertical smoke propagation and pressure distribution.

In this study, the numerical simulations were conducted using PyroSim 2025.1.0826, a dedicated graphical interface for the Fire Dynamics Simulator (FDS) 6.10.1. This configuration enabled efficient definition of the building geometry, fire sources, and boundary conditions, with the objective of evaluating the influence of mechanical ventilation on smoke distribution and pressure behavior under specific fire scenarios. PyroSim provides an intuitive yet robust environment for modeling complex smoke-propagation phenomena in built spaces using computational fluid dynamics (CFD) techniques. The resulting outputs contribute to a deeper understanding of smoke movement and associated risks, supporting the optimization of technical fire-protection strategies [

38].

Ventilation plays a critical role in fire simulations, influencing both smoke movement and HVAC system behavior. Although PyroSim allows for detailed fan configuration, conventional fan models, such as square-law or fixed-flow models, do not accurately reproduce dynamic pressure variations. Recent studies [

39,

40] recommend using a performance-point approach, in which airflow adjusts according to the system curve, providing more realistic and physically consistent results. In this study, for an existing building without a dedicated air-distribution network, a simplified pressurization strategy was adopted, consisting of a single fan installed at the top level [

7]. With this configuration, air is supplied directly where it is needed, eliminating the requirement for a full HVAC system. The supply opening enables localized control of airflow and generates overpressure within a defined zone. As a result, smoke spread is effectively limited in critical areas, while avoiding the cost, time, and complexity associated with traditional ducted systems employing multiple fans.

3.2. Simulation Domain and Mesh Rafinement

An effective configuration of the computational domain and mesh in FDS, implemented through PyroSim, forms the foundation for obtaining credible results and numerically balanced simulations. The computational domain must be sufficiently large to capture the dynamic influence of the fire on the physical boundaries and to prevent errors caused by artificial interactions at the domain limits. Proper mesh placement and adequate buffer distances between the fire source and the boundaries are essential to ensure realistic boundary conditions and coherent fluid behavior. This preparatory stage directly affects the overall quality of the simulation from both physical and numerical perspectives [

38]. The spatial resolution of the computational mesh plays a decisive role in resolving thermal phenomena and accurately tracking smoke evolution [

41]. Typically, resolution is calibrated according to the characteristic fire diameter. However, there is always a trade-off between mesh refinement and computational cost: a coarse mesh reduces accuracy, while an excessively fine mesh substantially increases computational demand. Therefore, sensitivity analyses and rigorous mesh-optimization strategies are indispensable for achieving an appropriate balance between performance and realism [

42,

43].

The model presented in

Figure 9 was designed according to a functional logic grounded in the physical behavior of fires and the requirements of modern CFD simulations within the large-eddy simulation (LES) framework. The computational domain was intentionally extended beyond the building geometry to capture external influences, such as atmospheric currents and environmental pressure differences, that significantly affect smoke distribution and air exchange between indoor and outdoor spaces [

6]. Domain discretization was performed using a hierarchical mesh structure. Regions characterized by intense thermal activity and highly dynamic flow features were assigned a fine spatial resolution, while peripheral areas were meshed with a coarser, uniform grid. This adaptive configuration ensured an appropriate balance between numerical precision and computational cost. To prevent inconsistencies at subdomain interfaces, strict alignment of mesh cells was maintained in accordance with established practices in the literature and with the implementation guidelines provided by PyroSim [

38].

The model was calibrated using experimental data obtained from full-scale tests involving wooden crib fires, in which the HRR and temperature evolution were measured and integrated into the simulations [

26]. This calibration step allowed the adjustment of key model parameters to reproduce, as accurately as possible, the phenomena observed under real fire conditions.

To accurately capture the thermodynamic behavior of air around the analyzed building, the computational domain was designed to extend beyond the structural footprint. This design choice was intentional: enlarging the domain allows for realistic modeling of interactions between internal airflow and external environmental conditions, an essential aspect of fire and ventilation simulations involving both natural and mechanical systems. According to the principles outlined in [

38], the domain must be sufficiently large to minimize artificial boundary effects. In this study, a final domain size of 35 × 20 × 15 m was selected, providing a buffer zone that enables accurate observation and control of both interior and exterior airflow. This configuration supports realistic simulation of wind-induced pressure variations, temperature gradients, and fire-induced flow effects, contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of the building’s aerodynamic response under fire conditions. Additionally, the extended volume ensures proper placement of boundary conditions without introducing artificial influences on flow distributions in the regions of interest.

The computational domain was configured modularly by defining several local subdomains, each tailored to a specific role within the fire-simulation framework. Multiple uniform local meshes were implemented, with dimensions and resolutions adapted to the fire-source location, infiltration points, and mechanically supplied airflow. To analyze fire behavior, the fire source was positioned at three elevations: the ground floor, fifth floor (F5), and ninth floor (F9). In each scenario, the ignition zone was enclosed within a refined subdomain measuring 6 × 4 × 1 m, allowing for detailed resolution of early-stage plume dynamics and thermal energy release. Additionally, forty small subdomains (0.75 × 0.75 × 0.75 m) were defined to simulate air infiltration associated with doors and windows at locations where envelope leakage significantly influences pressure distribution and airflow direction. These subdomains were strategically positioned near access areas and exposed façades to incorporate realistic air-leakage effects into the model [

6]. To maintain positive pressure at the ground floor, a single mechanical fan was modeled using the supply vent function, represented by a dedicated subdomain measuring 3 × 1.5 × 2 m. This configuration was applied consistently across all three scenarios (fire located at the ground floor, fifth floor, and ninth floor).

The computational mesh size [

3] plays a crucial role in determining both the precision of numerical results and the total simulation time. Consequently, identifying an optimal balance between accuracy and computational efficiency is essential for obtaining reliable outcomes within a reasonable timeframe. To evaluate the influence of mesh resolution on the simulation, several mesh densities were evaluated using the D*/dx ratio, which expresses the relationship between the characteristic fire diameter and the mesh cell size [

44]. In this study, D*/dx values ranged from 6.68 (coarse mesh, 0.25 m cells) to 33.4 (fine mesh, 0.05 m cells). Sensitivity analysis showed that a cell size of 0.05 m provides sufficient accuracy in resolving fire-induced airflow and smoke movement while maintaining a reasonable computational cost. Therefore, this resolution was selected for the final stage of simulations [

6].

In this study, fine mesh resolution with a cell size of 0.05 m was applied to the regions surrounding the fire source, air-supply openings, and infiltration zones. The remainder of the computational domain was modeled using a coarser mesh with 0.25 m cells. In the final mesh configuration, the fire-source region contained 192,000 cells, the supply-air subdomain 72,000 cells, and the infiltration regions 135,000 cells. Out of a total of 1,204,704 cells in the computational domain, approximately 877,632 were located in coarser-mesh regions, thereby optimizing computational cost without compromising accuracy in critical areas.

3.3. Specification of Boundary and Initial Conditions

The accurate definition of initial and boundary conditions constitutes a critical step in fire-driven CFD simulations, as these parameters directly influence numerical stability, thermal prediction accuracy, and the physical realism of the modeled flow and combustion processes. In the present study, Fire Dynamics Simulator (FDS) [

38] was employed to prescribe the ambient environment, domain boundaries, and the initial thermodynamic and chemical fields.

All simulations were conducted over a predefined total duration, starting from an initial time of t

0 = 0 s, with an adaptive time-step scheme applied to ensure numerical stability during the rapid fire growth stage. The flow field was resolved using the Very Large Eddy Simulation (VLES) approach, which explicitly captures the dominant turbulent structures while modeling subgrid-scale effects, thereby providing a balanced compromise between physical fidelity and computational efficiency [

6].

The computational domain boundaries were defined as open, allowing unrestricted mass and energy exchange between the interior and exterior environments. This configuration enables a realistic representation of natural ventilation through architectural openings without imposing artificial constraints on airflow. Exterior boundary conditions were specified to ensure equilibrium with the surrounding atmosphere.

Initial indoor conditions were prescribed to represent a typical pre-fire indoor environment, with thermodynamic and chemical parameters selected to reflect standard atmospheric composition and naturally ventilated conditions. Optical properties relevant to visibility and radiative transfer were defined using commonly adopted smoke-transport formulations, while gravitational acceleration was applied along the vertical axis to accurately reproduce buoyancy-driven flow behavior.

Atmospheric conditions in the exterior domain were modeled using the Monin-Obukhov similarity theory [

45], assuming a stable boundary layer and horizontally homogeneous inflow conditions. This approach ensures a realistic coupling between wind-driven ventilation and buoyancy effects within the building.

Overall, the selected initial and boundary conditions provide a physically consistent framework for simulating the coupled interaction between fire development, ventilation, buoyancy, and smoke transport in a multi-story building, as summarized in

Table 2.

3.4. Simulation Configuration

To evaluate the impact of forced ventilation on smoke distribution and pressure conditions in high-rise buildings, a fresh-air supply system was implemented in the simulation and configured within the PyroSim interface. In the analyzed S2 scenario, a supply-type fan was activated at the ground level of the structure, delivering an airflow rate of 2.0 m3/s introduced normal to the surface. The imposed flow was defined by volumetric rate rather than velocity or mass flux, allowing precise control of the pressure generated within the interior space.

Fan operation was modeled using a hyperbolic-tangent (tanh) activation function, enabling a gradual ramp-up over 3 s to prevent initial flow shocks and to provide realistic transient behavior. In addition, the wind profile was defined using an atmospheric power-law relationship with an exponent of 0.2 and a reference height of 3 m, parameters chosen to reproduce realistic street-level conditions in the surrounding urban environment. This configuration proved essential for simulating differentiated pressure fields and airflow patterns under fire conditions, significantly contributing to the limitation of smoke ingress into vertical circulation zones, as observed in the results for Scenario S2.

Beyond airflow specification, the configuration of the lower supply fan included detailed modeling of convective heat transfer at the interface between the fan surface and the surrounding environment. A constant convective heat-transfer coefficient of 25 W/(m2·K) was applied, representing a moderate heat-exchange regime between the incoming air and the domain boundaries.

From a radiative perspective, the surface emissivity was set to 0.9, characteristic of a nearly perfect radiative surface typical of coated metallic components or other technical building elements exposed to elevated temperatures. Thermal boundary conditions were defined using a constant imposed temperature correlated with the standard ambient temperature of the simulation domain, ensuring that the supplied air entered the interior space unheated.

The environmental parameters used in the simulation, pressure, temperature, velocity, visibility, and carbon monoxide concentration, were selected based on their direct influence on fire development and smoke propagation in high-rise buildings, consistent with recent CFD-based fire modeling studies [

46,

47,

48,

49]. The heat release rate (HRR) was defined using a t

2 growth model adapted to the thermal load and compartment geometry. Boundary conditions for pressure and temperature were chosen according to realistic operating scenarios and refined through sensitivity analyses to ensure numerical stability and physical realism.

Figure 10 illustrates the placement of monitoring points and analysis sections used to evaluate the thermal and gas-flow behavior during the fire. Ten measurement points were distributed within the stairwell, one at each above-ground floor, positioned centrally along the stair flights to capture vertical variations in temperature, air velocity, and carbon monoxide (CO) concentration. This sensor configuration enables clear observation of thermal stratification and smoke migration between levels.

Three-dimensional slice planes oriented along the X, Y, and Z axes at various elevations provided detailed insight into the propagation of hot gases and the stack-effect-driven movement within the stairwell. Monitoring environmental conditions in this zone is imperative, as the stairwell represents the primary evacuation route for occupants during a fire.

Temperature sensors were strategically positioned to capture the key phases of smoke movement along the evacuation routes. In parallel, the system monitored airflow directions influenced by natural pressure differentials and mechanical ventilation. This monitoring framework provides a comprehensive perspective on thermal stratification, smoke dispersion, differential pressure effects, occupant protection, and accessibility for firefighting and rescue operations.

The PyroSim simulations were executed on a high-performance computing infrastructure consisting of multiple workstations optimized for parallel processing. Each workstation was equipped with a 13th-generation Intel Core i9-13900K processor, operating at a maximum clock speed of 5.80 GHz with a 36 MB cache, capable of efficiently handling complex computational loads through its hybrid architecture. The OpenMP environment was configured with 24 threads and a stack memory of 64 MB, ensuring balanced workload distribution across processor cores and maintaining high execution efficiency.

Simulations for scenarios S1 and S2 were performed over a total duration of 360 s using a constant time step, ensuring numerical stability and consistency of the results throughout all analyzed configurations.

3.5. Description of the Burner’s Structural and Operational Characteristics

The characteristics of the fire source used in this study are grounded in a rigorous process of design, testing, and validation, based on the experimental-numerical research published [

26].

The burner surface was defined in FDS and configured to reproduce as accurately as possible the thermal behavior observed in the full-scale experiments. The key parameter, HRRPUA (Heat Release Rate per Unit Area), was set to 100 kW/m2, a value characteristic of dry solid wood burning under indoor, well-ventilated conditions. As a result, the burner surface provides a realistic fire representation and allows precise calibration of the thermal response of the built environment relative to the imposed heat source.

The combustion model associated with the burner was defined using a custom chemical reaction representative of processed cellulosic materials and composite wood products. In accordance with the requirements of FDS the combustible material was described using a predefined and widely recognized elemental composition model, consisting of carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen with stoichiometric proportions of C

3.4H

6.2O

2.5N

0 [

50]. This formulation provides a physically consistent approximation of wood-based fuels and enables a reliable representation of the combustion process within the numerical framework.

The reaction includes key parameters that influence fire development and occupant safety: the critical flame temperature was set to 1327 K, the carbon monoxide (CO) yield to 0.042 kg/kg, and the soot yield to 0.198 kg/kg, a relatively high value indicating significant smoke production and the presence of suspended solid particles. In addition, the radiative fraction was set to 35%, reflecting the burner’s ability to transfer a substantial portion of energy through thermal radiation. These parameters, combined with the burner surface characteristics, enable realistic modeling of combustion behavior and toxic product generation, with direct applications in ventilation assessment, evacuation analysis, and thermal protection evaluation.

4. Simulation Results

4.1. Description of the Simulation Cases

To accurately reproduce the real behavior of a building under fire conditions, the scenarios simulated in PyroSim incorporated dynamic activation conditions correlated with the thermal development of the fire and the response of safety systems. The mechanical fan was programmed to start automatically upon smoke-detector activation, simulating the operation of an emergency pressurization system. In parallel, the window of the affected compartment was configured to open only when the temperature measured above the burner reached 120 °C, allowing the analysis of ventilation driven by thermal effects rather than pre-defined scheduling. In all six simulations, the door of the compartment containing the fire source opened 60 s after ignition, representing the moment of a sudden change in pressure balance and oxygen availability. These simulation conditions ensure consistency across all cases and allow a relevant comparative assessment of how controlled openings, thermal, mechanical, or time-triggered, affect smoke propagation, temperature distribution, and occupant safety.

The two analyzed scenarios are described below to clarify the simulation conditions:

Scenario 1 (

Figure 11)—No active ventilation (passive system based on infiltration):

Three numerical simulations were performed: S1-F0 (fire on the ground floor), S1-F5 (fire on the 5th floor), and S1-F9 (fire on the 9th floor).

Smoke propagation is influenced solely by the stack effect and natural air infiltration through permeable building elements.

The door of the fire compartment (1 × 2 m) opens 60 s after ignition in all cases.

The window of the fire compartment (1.40 × 1 m) opens dynamically when the local temperature reaches 120 °C, simulating a thermally driven opening.

Before the door and window open, infiltration paths remain active in all three simulations; after their activation, the infiltration surfaces in the fire compartment are replaced by the corresponding window and door openings.

Scenario 2 (

Figure 12)—Mechanical ventilation with controlled pressurization (differential pressure system):

Three numerical simulations were performed: S2-F0 (fire on the ground floor), S2-F5 (fire on the 5th floor), and S2-F9 (fire on the 9th floor).

A mechanical supply fan located at the ground floor is activated, introducing a constant airflow rate of 2 m3/s, which starts automatically upon smoke detection by the detector installed inside the fire compartment.

The window in the fire compartment (1.40 × 1 m) opens dynamically when the local temperature reaches 120 °C in all cases, simulating a thermally driven opening.

The door of the fire compartment (1 × 2 m) opens after 60 s in all cases.

Until the moment the door and window of the fire compartment open, infiltration vents remain active in all three simulations. When the door and window open, the infiltration openings at the fire-compartment level are replaced by the effective openings created by the window and the door.

The modeling assumptions regarding fire growth, heat release, and time-dependent openings were derived and calibrated based on prior experimental and numerical research [

6,

7,

26]. Implemented in PyroSim, the FDS model incorporates realistic boundary conditions and thermal interactions, ensuring a robust representation of the physical processes relevant under both passive and mechanically ventilated conditions. This scenario structure provides a scientifically sound and practically relevant framework for assessing fire dynamics and the performance of smoke-control strategies in tall buildings.

4.2. Analysis of Temperature Distribution Inside the Building

The specialized literature indicates that human tolerance to high temperatures during a fire is strictly limited by exposure duration and ambient conditions (humidity and radiation). According to guideline [

51], air temperatures up to 60 °C can be tolerated for a maximum of 5–10 min without causing severe physiological effects. Above this threshold, at 80–100 °C, the safe exposure time decreases to 1–3 min, a range also confirmed by the evacuation model presented in another scientific study [

52]. Experimental data on firefighting interventions show that at approximately 120 °C, incapacitation can occur in less than one minute, even under dry-air conditions [

53]. Evaluations based on the ISO 13571 criterion [

54] further confirm that cumulative exposure depends on the combined effect of temperature and time, explaining the rapid decrease in survivable duration as temperature increases.

Consequently, for protecting evacuation routes, including the stairwell, it is essential that air temperature be maintained below 60 °C throughout the entire evacuation period, since exceeding this limit rapidly reduces safe exposure time and compromises interior safety conditions. To evaluate the thermal behavior in evacuation-critical zones, the simulations included a vertical slice positioned along the stairwell, which communicates with the fire compartment through a door automatically opened at t = 60 s, as well as temperature measurement points located on each floor. This configuration enables precise observation of how hot smoke enters and spreads within the stairwell under the combined influence of the stack effect and potential recirculation patterns.

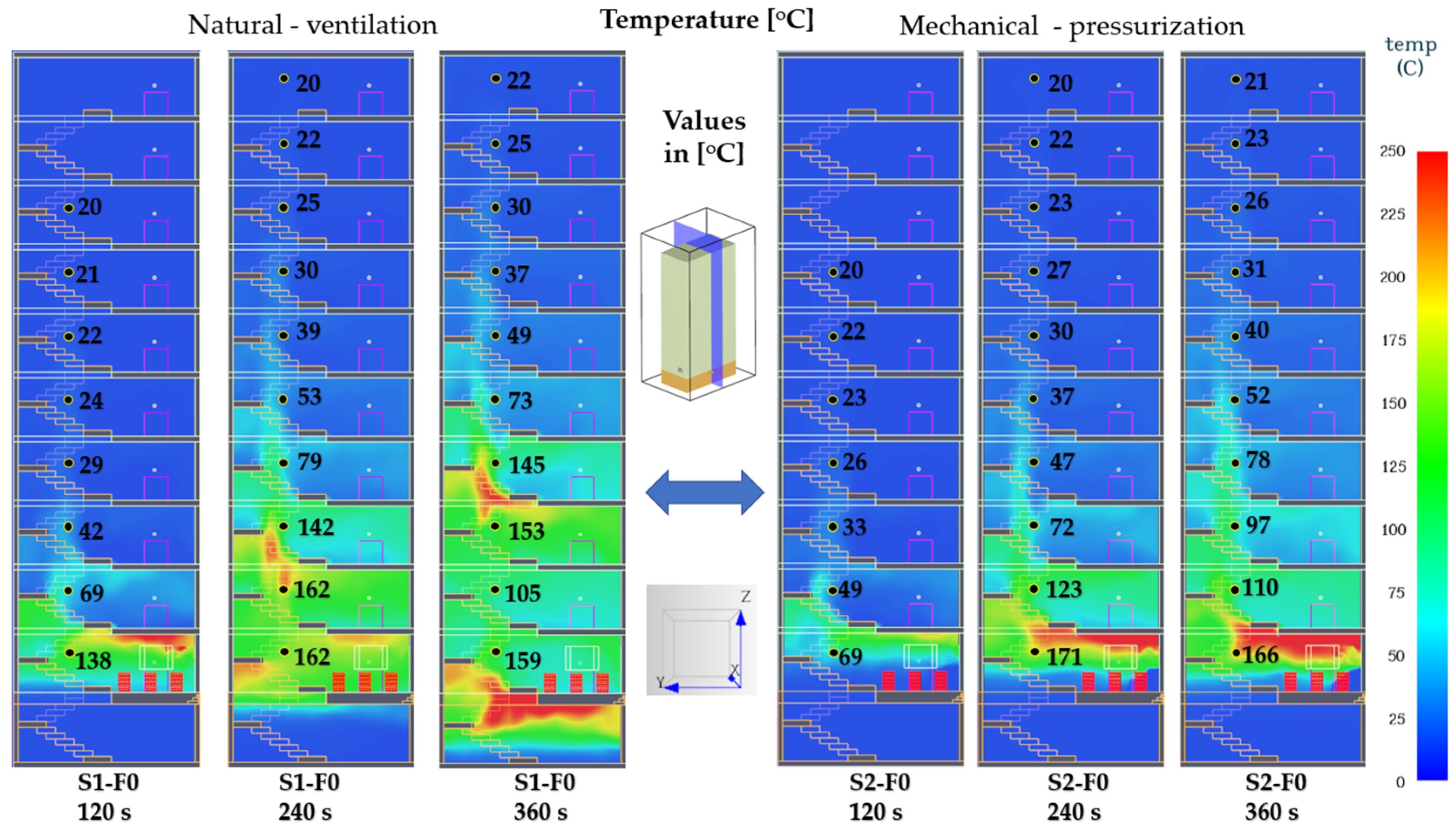

A comparative evaluation of scenarios S1-F0 and S2-F0 (

Figure 13) reveals measurable differences in thermal behavior along the stairwell. The average stairwell temperature was determined by averaging ten representative temperature points along the stairwell height at 360 s. For the natural ventilation case (S1), the mean temperature reached approximately 79.8 °C, while for the mechanically pressurized case (S2) it was about 64.4 °C, corresponding to an overall 19% reduction under mechanical pressurization. These results confirm that the system mitigates vertical heat accumulation and stabilizes the thermal field, thereby delaying smoke propagation without significantly lowering the peak temperature near the fire floor.

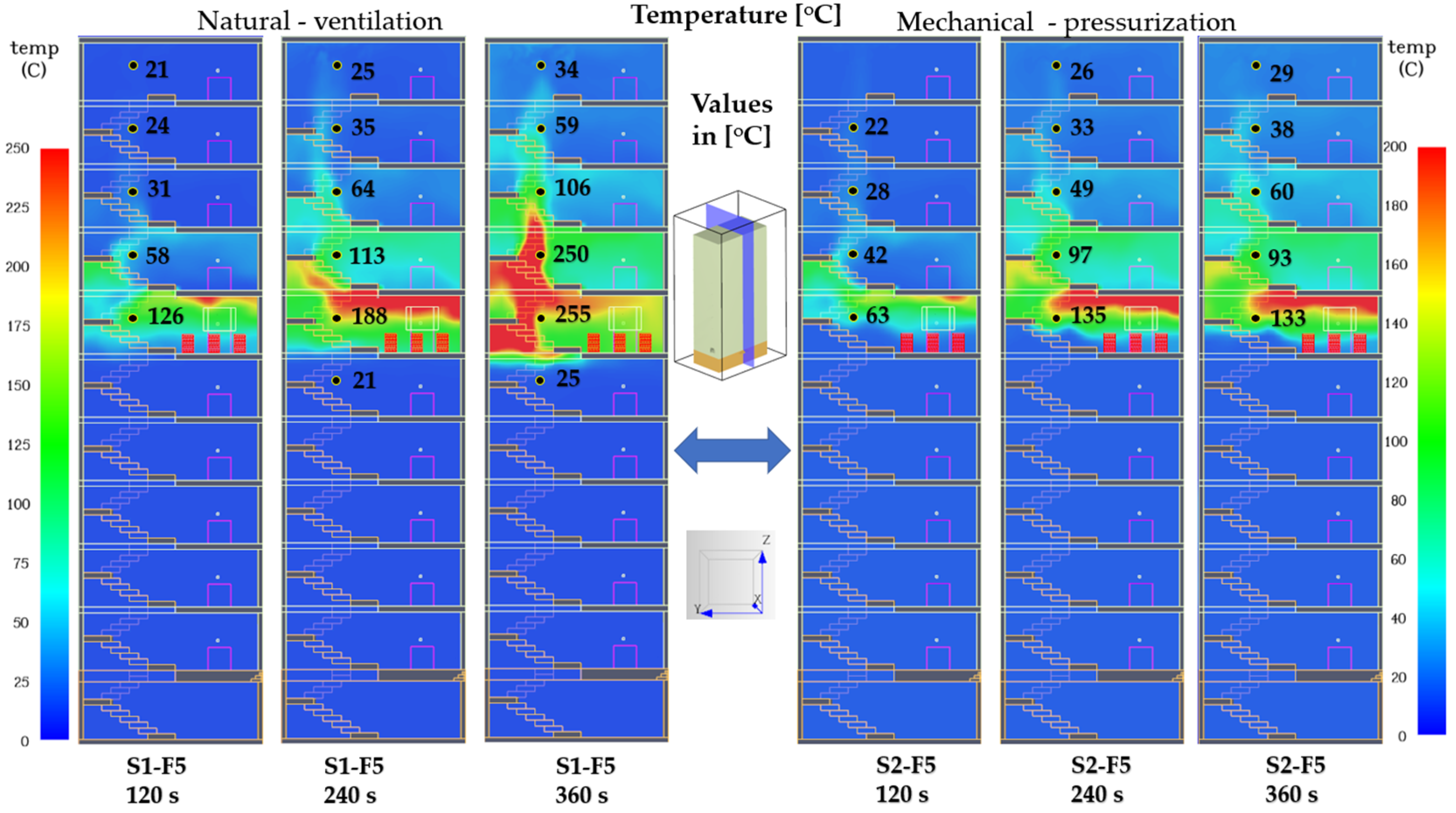

When the fire source is located at the fifth floor (F5), distinct thermal behaviors are observed between the two ventilation modes (

Figure 14). Under natural ventilation (S1), buoyancy forces drive rapid heat rise from the fire floor, producing peak temperatures of about 255 °C and an average of 80.9 °C along the stairwell, indicating extensive vertical spread. In contrast, mechanical pressurization (S2) confines the hot gases near the fire floor, with upper-level temperatures remaining below 93 °C and an overall average of 45.3 °C, representing a 44% reduction. This confirms that pressurization effectively limits upward heat propagation and preserves tenable conditions in the upper stairwell zone.

The thermal analysis for scenarios S1-F9 and S2-F9 (

Figure 15), corresponding to a fire located on the top floor, highlights pronounced differences in stairwell convection and heat retention. Under natural ventilation (S1-F9), the stack effect drives strong upward buoyant flow, leading to a stagnant hot-gas layer near the ceiling where temperatures reach 329 °C. The mean stairwell temperature, calculated as 63.2 °C, confirms intense thermal accumulation in the upper section, with levels 8 and 9 becoming completely non-tenable. In contrast, mechanical pressurization (S2-F9) introduces a forced airflow that partially counteracts buoyancy. The average temperature decreases to 33.7 °C, while the peak temperature is reduced to 137 °C, indicating a 47% reduction in mean thermal load compared to S1.

Overall, these results show that while base-level pressurization enhances vertical airflow and mitigates excessive heat buildup, its efficiency diminishes for upper-floor fires without a dedicated venting path.

The comparative assessment of fires located on the ground, fifth, and ninth floors demonstrates that the efficiency of mechanical pressurization increases with fire elevation. Under natural ventilation, the stairwell acts as a buoyancy-driven shaft where temperatures exceed 250–300 °C, causing rapid loss of tenability. Mechanical pressurization reduces this effect progressively: by about 19% at the ground floor, 44% at mid-height, and up to 47% on the top floor. As the fire source moves upward, the airflow counteracts buoyancy more effectively, confining heat near the ignition level and maintaining lower sections below 25 °C. This trend confirms a shift from uncontrolled natural convection to a balanced mixed-convection regime, where mechanical pressurization becomes increasingly dominant.

4.3. Velocity of Airflow Throughout the Building Interior

The velocity analysis within the stairwell shows that once the fire-compartment door opens, smoke control is no longer governed by pressure differentials but by the airflow velocity at the doorway connecting the stairwell to the fire compartment. According to the European standard [

26], a minimum airflow velocity of 2 m/s is required at this interface to prevent smoke entering the stairwell.

In Scenario S1, the flow is driven solely by the thermal stack effect, resulting from density differences between the hot gases in the fire compartment and the cooler air inside the stairwell (

Figure 16). In the absence of mechanical pressurization or an upper-level exhaust opening, the airflow develops transiently through structural leakages, reaching local velocities of up to 2.3 m/s in the upper region. As thermal stratification stabilizes, the stack effect weakens and the airflow becomes reversible, allowing smoke to migrate into the evacuation route.

In Scenario S2, the pressurization fan initially maintains a 50 Pa pressure differential, preventing smoke infiltration. After the fire-compartment door opens, the system generates a mechanically assisted stack effect, producing a more stable upward flow; however, the absence of an upper-level exhaust opening causes smoke to accumulate at the top of the stairwell. At the fire-compartment doorway, the measured velocities in the fan supply region (1.25–1.4 m/s) remain below the 2 m/s threshold required by standard [

26], indicating the need to optimize pressurization settings or local geometry to ensure an effective aerodynamic smoke barrier.

The velocity distribution analysis for the fire located on the fifth floor (

Figure 17) reveals distinct airflow behaviors between the two scenarios. In Scenario S1, a strong thermal stack effect develops in the upper part of the stairwell, where velocities reach up to 3.3 m/s at 360 s, indicating a rapid upward movement of hot gases generated by the fire. At the lower levels, airflow drops below 0.3 m/s, promoting smoke stagnation and local recirculation. In Scenario S2, the pressurization fan introduces a more stable vertical airflow but weakens the stack effect, as heat accumulates predominantly within the fire-floor lobby rather than propagating toward the stairwell. The fan-induced flow counteracts the natural upward motion of hot gases. Although the system is designed to maintain 2 m/s at the fire-room door, the simulated velocities, approximately 1.6 m/s along the stairwell ramps, indicate insufficient pressurization, unable to fully prevent smoke migration into the stairwell. Overall, Scenario S1 generates a strong but unstable buoyancy-driven draft, whereas Scenario S2 provides a more coherent but only partially effective air barrier. These findings highlight the need to optimize airflow direction and balance the interaction between the stack effect and mechanical pressurization.

For the fire located on the top floor (

Figure 18), Scenario S1 shows that airflow within the stairwell is extremely weak. Velocities remain near zero along most of the vertical shaft, and the thermal plume generated in S1-F9 is insufficient to establish a sustained stack effect. The flow remains isolated and unstable, characterized by recirculation pockets and stagnant regions persisting even at 360 s. In Scenario S2, the ground-floor pressurization fan generates a stable upward airflow through the lower and intermediate levels (F0–F8), establishing a continuous pressure column up to the top floor. At the ninth floor, velocities remain below 1 m/s, allowing limited smoke infiltration into the stairwell; however, the mechanically induced upward flow prevents significant smoke accumulation at the upper landing and protects the lower floors from backflow and thermal contamination.

The results show that stairwell airflow is strongly dependent on fire location. In the passive case (S1), buoyancy generates only localized and unstable drafts: a short-lived plume at F0, partial upper-shaft activation at F5, and almost no vertical circulation at F9. In contrast, mechanical supply (S2) produces a stable upward airflow on the lower floors, with effectiveness increasing as the fire source is positioned higher in the building. However, at F9, the doorway velocity drops below 1 m/s, allowing limited smoke ingress through the upper opening while still preventing smoke accumulation on the lower levels. Overall, neither natural ventilation nor single-point pressurization ensures compliant airflow across all scenarios. The findings support multi-level or stratified pressurization strategies to consistently meet the standard [

26], velocity requirements at critical smoke-transfer locations.

4.4. Visibility Inside the Building

Reduced visibility caused by smoke propagation is a critical factor that determines the success or failure of evacuation during a fire. In study [

55], simulations performed on a building under construction showed that visibility drops below the 10 m threshold in less than 200 s, particularly in corridors and stairwells where smoke accumulates rapidly in the absence of compartmentation. Complementarily, another study [

56] proposes a method for evaluating visibility along evacuation routes based on the relationship between the smoke extinction coefficient and visible distance. Using visibility fields, the authors demonstrate that distances greater than 8-10 m to exit signs become visually inaccessible under dense smoke conditions. Building on these findings, the present analysis evaluates visibility in the simulated scenarios, focusing on the impact of smoke on vertical evacuation through the stairwell.

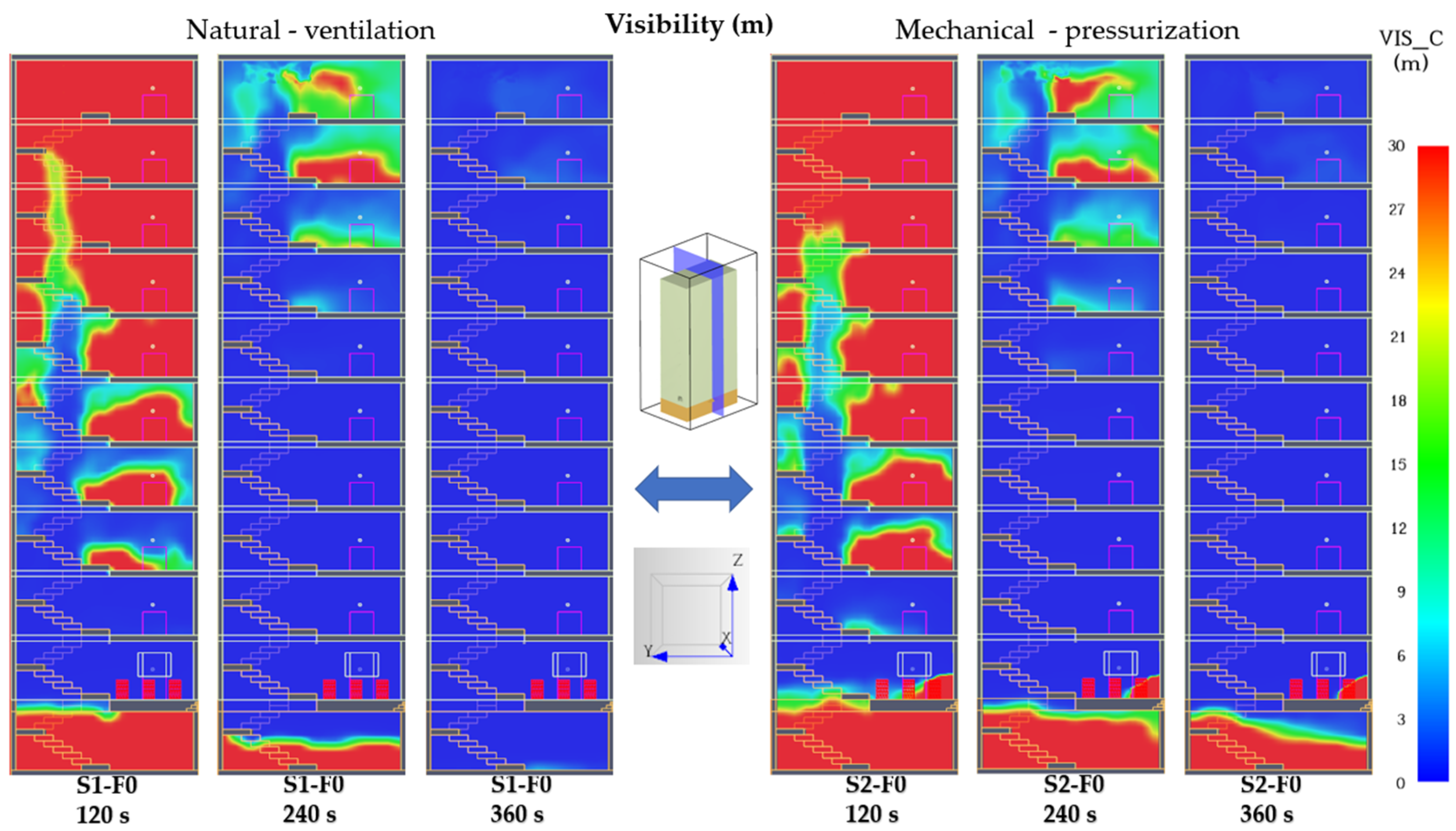

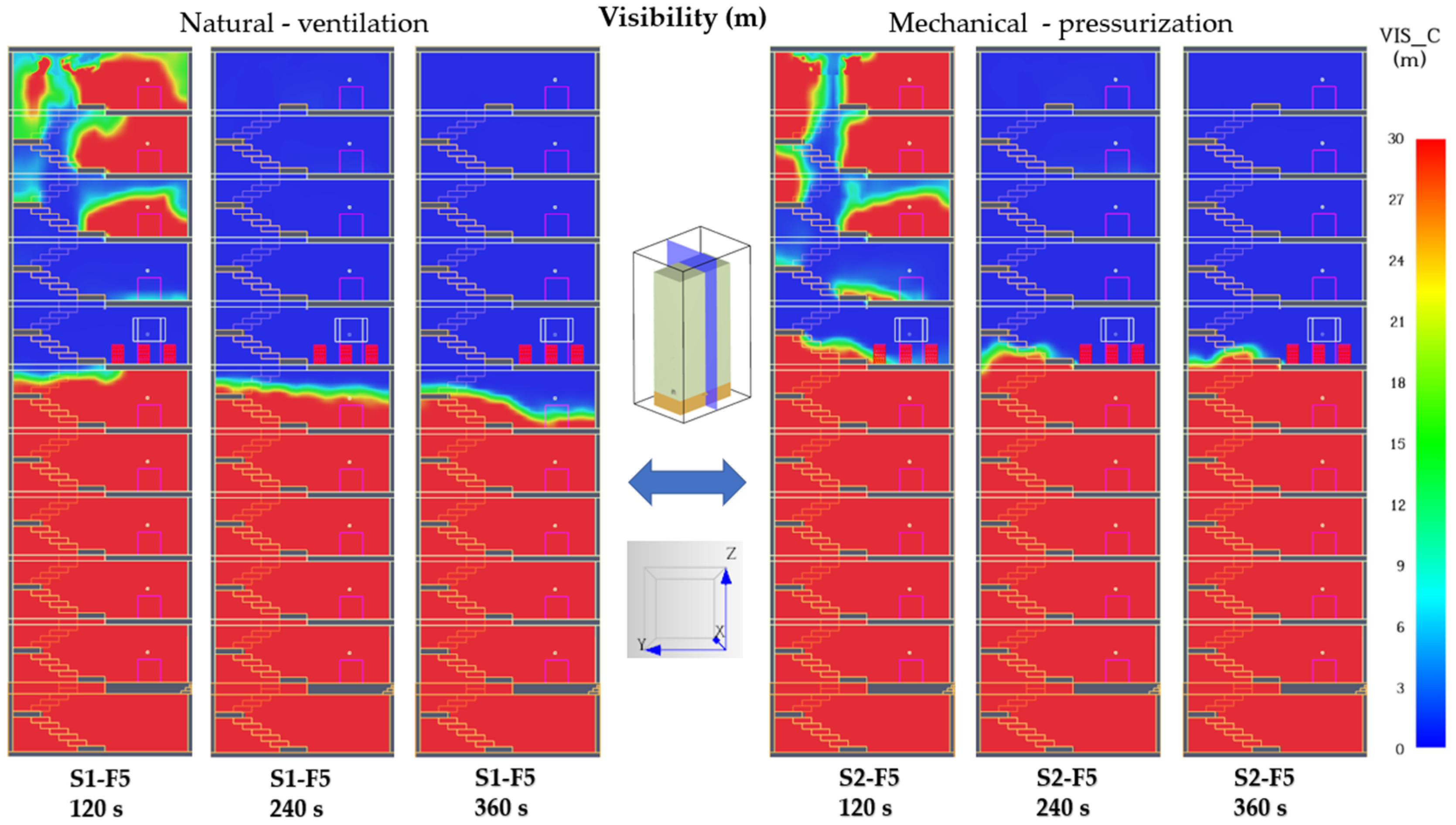

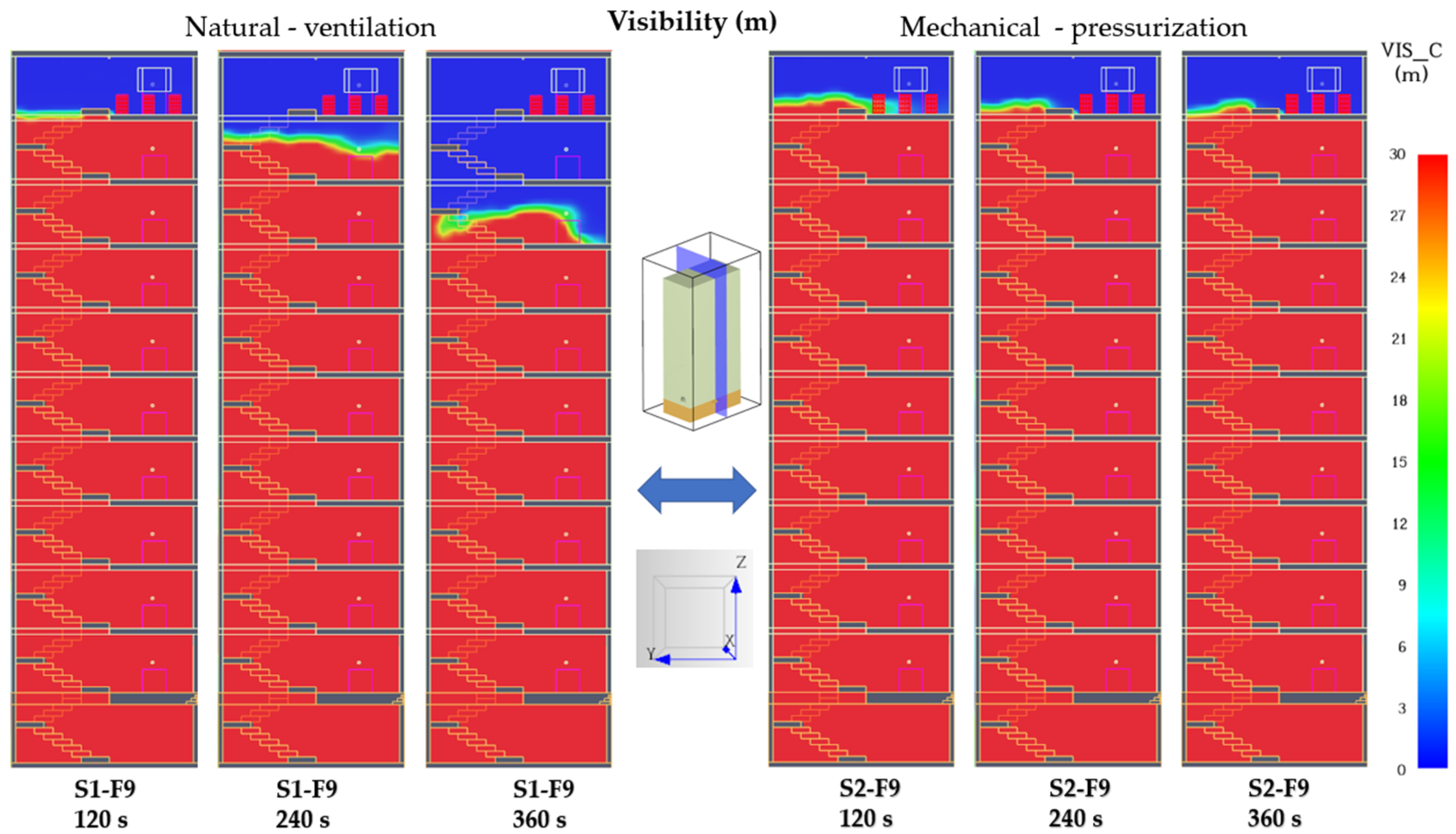

For a ground-floor fire (

Figure 19), visibility deteriorates rapidly in both configurations. Under natural ventilation (S1-F0), the stairwell becomes completely smoke-filled within 360 s, with visibility below 2–3 m across all levels. In the mechanically pressurized case (S2-F0), visibility remains high only in the basement zone, where pressurization air is supplied, maintaining 28–30 m. Above the ground floor, however, visibility collapses to values similar to S1, generally below 5 m. The overall improvement is therefore localized and limited, confirming that mechanical pressurization protects only the supply zone but cannot prevent smoke accumulation in the vertical shaft. These findings highlight the need for enhanced airflow direction or compartment sealing at the ground-floor interface to ensure full stairwell protection.

At 360 s (

Figure 20), visibility in the stairwell is critically reduced in both scenarios. Under natural ventilation (S1-F5), the mid and upper sections are completely obscured, with visibility below 3 m across five consecutive levels. In the mechanically pressurized case (S2-F5), only the basement and first four floors maintain 28–30 m visibility, while the central and upper zones exhibit heavy smoke accumulation similar to S1. The mean visibility improvement is confined to the lower third of the stairwell, confirming that single-point pressurization protects the supply zone but cannot sustain clear conditions near or above the fire floor.

At 360 s (

Figure 21), smoke accumulation is confined to the upper section of the stairwell. In the natural ventilation case (S1-F9), visibility drops to 0–2 m on the ninth floor, 2–5 m on the eighth, and partially recovers to about 10 m at the seventh, while lower levels remain clear (28–30 m). Under mechanical pressurization (S2-F9), airflow sustains full visibility (30 m) across the lower seven floors but fails to improve conditions near the fire floor, where visibility remains near zero. The pressurization thus prevents smoke descent but cannot restore tenability in the uppermost volume, confirming the need for a top exhaust or localized upper-floor pressurization to maintain safe evacuation visibility.

At 360 s, visibility varies with fire location. Under natural ventilation (S1), the stairwell is fully obscured for ground-floor fires, severely degraded at mid-level, and limited to the upper floors for top-level fires. Mechanical pressurization (S2) preserves clear conditions (25–30 m) only near the air inlet, with little improvement (≈20%) in smoke-affected zones where visibility remains below 5 m. Overall, single-point pressurization delays smoke descent but cannot maintain tenable visibility near the fire source, indicating the need for multi-level or top exhaust systems.

4.5. Differential Pressure Inside the Building

The differential pressure within the stairwell shows a strong dependency on fire location and the ventilation regime. Under natural ventilation (S1), the pressure field is unstable and governed entirely by buoyancy, generating positive values near the upper floors and slight depressurization at the lower levels. This pattern provides no effective aerodynamic barrier against smoke migration.

Under mechanical pressurization (S2), the system initially achieves 50–70 Pa, consistent with standard [

26] requirements, but this barrier rapidly weakens once the fire-room door opens, when flow control transitions from pressure-based to velocity-based. For fires located on the lower floors, the pressurized volume is rapidly depleted toward the fire compartment, reducing pressure near the fan. For mid-level fires, pressure redistributes vertically, moderating stack-driven flow but failing to maintain normative values. For upper-floor fires, the base-mounted pressurization cannot counteract the strong buoyant up flow, leading to a loss of positive pressure in the critical upper volume.

Overall, the results demonstrate that single-point pressurization at the ground floor is insufficient to ensure robust differential-pressure control for all fire locations. This supports the need for zoned or adaptive pressurization strategies capable of maintaining both the required differential pressure and the 2 m/s door-jet criterion, regardless of fire position.

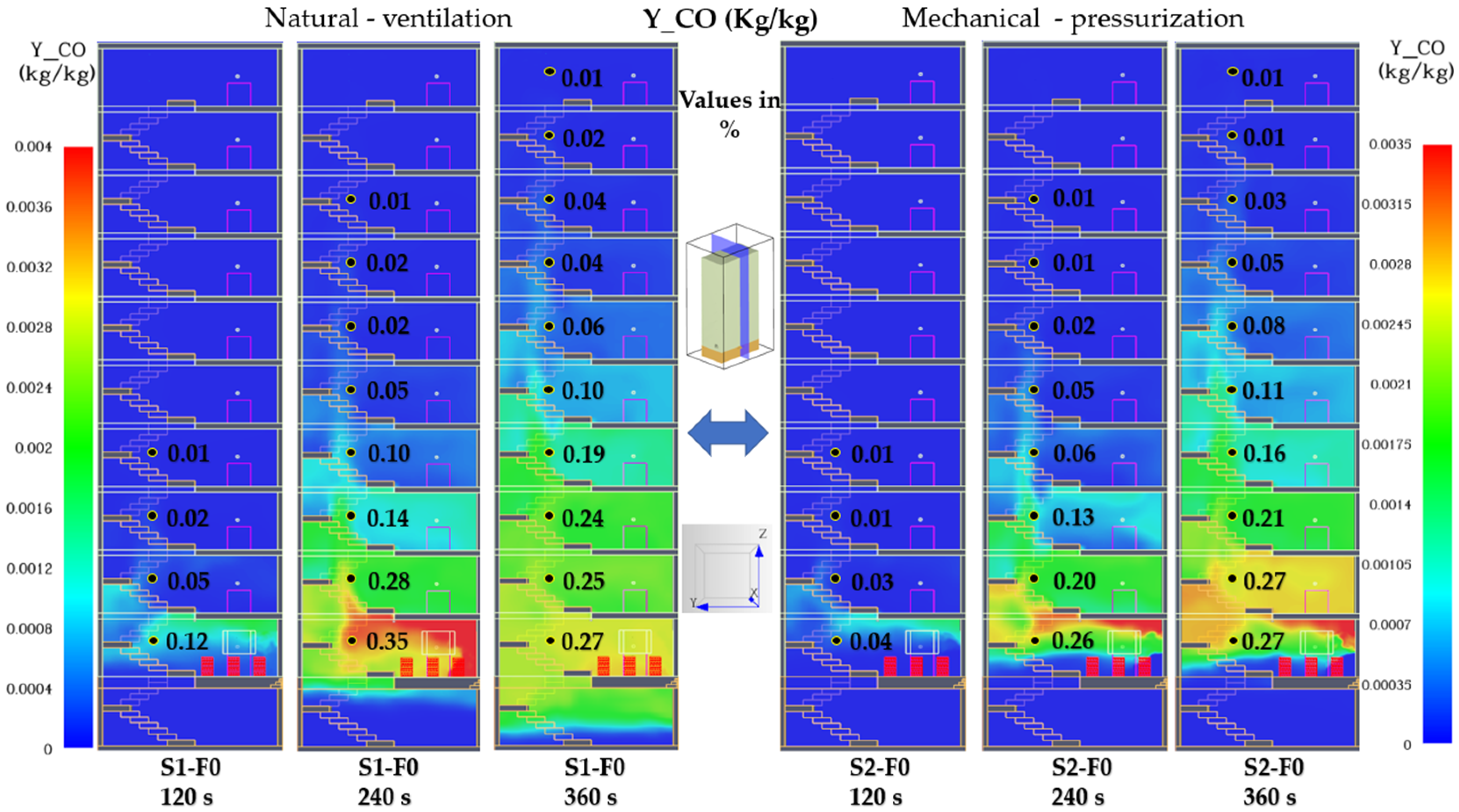

4.6. Dynamics of Combustion Gas Accumulation CO in the Built Environment

According to the conclusions of study [

6], carbon monoxide concentrations in fire environments can exceed 1200 ppm (0.12%), a threshold associated with a lethal exposure time of approximately 15 min. In the present analysis, CO distribution within the stairwell was evaluated using vertical slices along the X = 7.50 m axis, comparing the two ventilation scenarios. In both S1 and S2 (

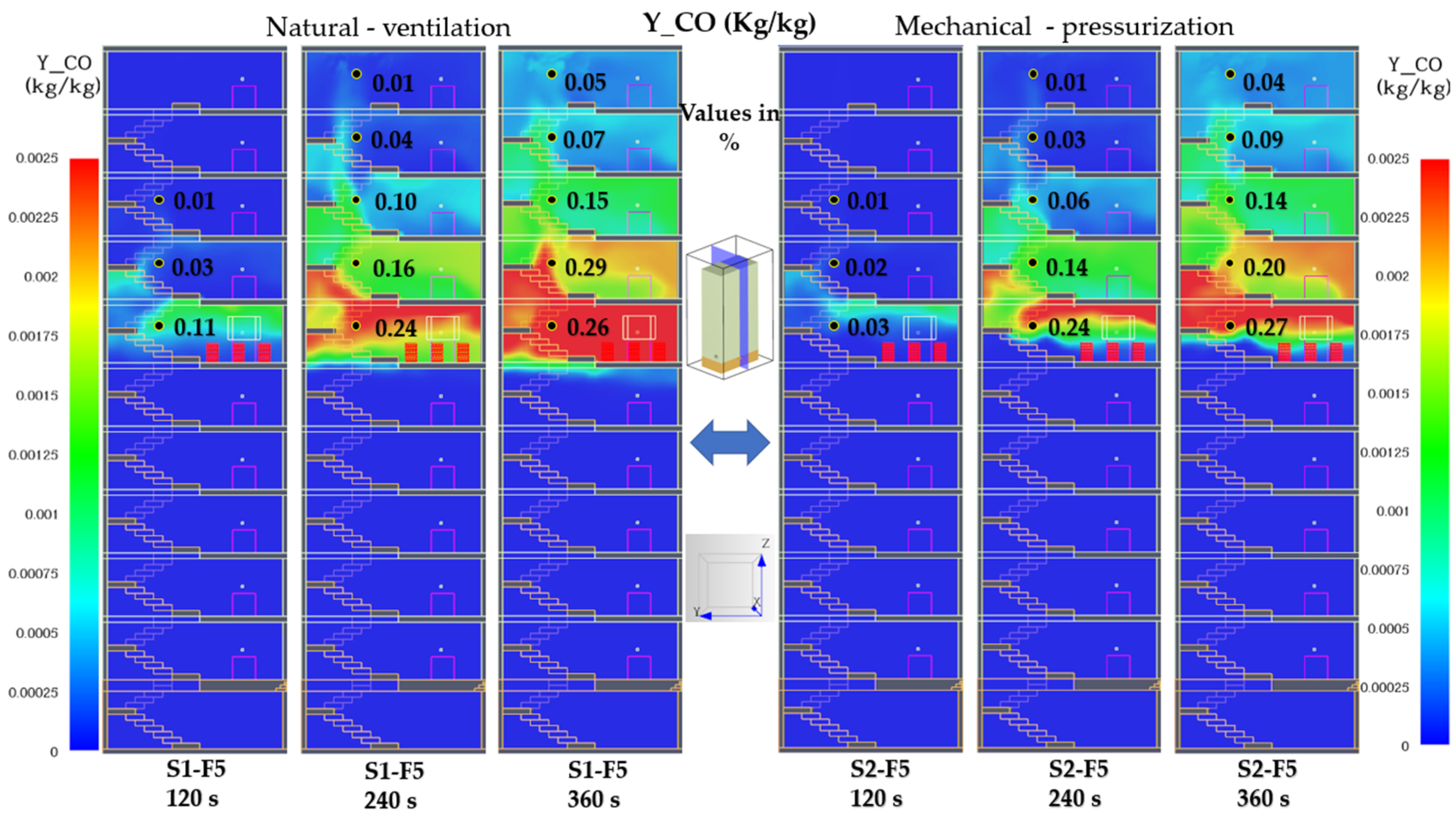

Figure 22), the average CO concentration along the stairwell exceeds the admissible safety threshold of 0.12%, with mean values of 0.122% for S1-F0 and 0.133% for S2-F0 at 360 s. While mechanical pressurization (S2) effectively limits the vertical spread of smoke and CO, confining high concentrations to the lower section, it does not reduce the overall toxicity below critical levels. Consequently, neither configuration ensures tenable evacuation conditions. These results indicate that single-point pressurization must be complemented by top-level exhaust or dilution systems to maintain CO concentrations within acceptable safety limits throughout the stairwell.

In both S1 and S2 (

Figure 23), carbon monoxide concentrations exceed the critical threshold of 0.12% (1200 ppm) near the fire source located on the fifth floor. Under natural ventilation (S1-F5), mean CO levels reach 0.164% (1.64 × 10

−3 kg/kg), with peak values of 0.26–0.29%, showing rapid vertical spread that contaminates both adjacent levels. In the mechanically pressurized case (S2-F5), the mean concentration decreases slightly to 0.148% (1.48 × 10

−3 kg/kg), and high values (0.20–0.27%) remain confined to the fire and upper floors. Although pressurization limits downward gas migration, both scenarios remain above the tenability threshold, confirming that airflow supplied only from the ground floor cannot control CO accumulation when the fire occurs at mid-height.

In both S1 and S2 (

Figure 24), carbon monoxide concentrations in the upper part of the building exceed the tenability threshold of 0.12%, reaching 0.27% under natural ventilation and 0.28% under mechanical pressurization. In S1-F9, CO accumulates in a stable upper layer confined between floors 8 and 9, with negligible downward propagation due to strong thermal stratification. In S2-F9, positive pressure generated at the stairwell base prevents smoke intrusion into the lower floors but intensifies local accumulation near the fire compartment, where counter-flow buoyancy limits venting.

Thus, both configurations produce critical CO levels through different mechanisms, S1 by vertical smoke spread and S2 by localized buildup. This confirms that single-point pressurization cannot ensure safe upper-level conditions and that dedicated exhaust or dual-pressurization systems are required to remove toxic gases effectively from the upper volume.

In all simulated scenarios, carbon monoxide concentrations exceed the critical safety threshold of 0.12%, regardless of ventilation mode. While mechanical pressurization limits CO spread to lower floors, it does not reduce overall toxicity, mean values remain between 0.13% and 0.28% near the fire source. These results confirm that single-point pressurization alone cannot control CO accumulation, and effective mitigation requires dedicated exhaust or multi-level airflow systems to maintain safe CO levels within the stairwell.

5. Discussions

The comparative analysis of the simulated scenarios confirms the strong influence of fire-source location on stairwell tenability and the performance of ventilation systems in high-rise buildings. Under natural ventilation (S1), the stairwell behaves as a buoyancy-driven shaft where the stack effect promotes rapid vertical propagation of smoke and hot gases. Temperatures exceed 250–300 °C, leading to a complete loss of tenability, which is consistent with previous experimental findings on natural smoke movement in vertical shafts [

57]. When mechanical pressurization (S2) is applied, the airflow transitions from uncontrolled free convection to a partially directed mixed-convection regime. The injected air establishes a stabilizing buffer layer that reduces the upward movement of smoke and delays heat transfer, particularly when the fire source is located on upper floors. As the fire elevation increases, the mechanical airflow counteracts buoyancy more effectively, reducing temperatures by approximately 19% at the ground floor, 44% at mid-height, and 47% at the top floor.

At 360 s, visibility depends strongly on fire location. In S1, the stairwell is fully obscured for ground-floor fires, severely degraded at mid-level, and partially clear at the top when the fire occurs on higher floors. In S2, clear visibility (25–30 m) is preserved only near the air inlet, while smoke-affected zones improve slightly (20%), yet visibility remains below 5 m near the source. These results confirm that single-point pressurization delays smoke descent but cannot maintain tenable visibility, emphasizing the need for multi-level or top-exhaust systems [

7,

58].

In all simulated scenarios, carbon monoxide (CO) concentrations exceed the critical safety threshold of 0.12% (1200 ppm), regardless of ventilation mode. Mechanical pressurization confines CO to lower floors but does not reduce overall toxicity, mean values range between 0.13% and 0.28% near the fire source. In contrast, under natural ventilation, CO disperses vertically throughout the stairwell, simultaneously affecting several levels. These findings demonstrate that single-point pressurization alone cannot control CO accumulation and that effective mitigation requires dedicated exhaust or multi-level air supply systems [

58].

Moreover, when the door of the fire-compartment opens, the pressure equilibrium collapses, and air distribution becomes dependent on smoke flow velocity. This behavior highlights the temporary efficiency of single-point pressurization and supports the adoption of zoned or adaptive multi-level control systems capable of maintaining stable pressure conditions under dynamic fire scenarios [

59].

The model employs a simplified geometry, excluding furnishing and adjacent rooms to optimize computational time, while the fire source was experimentally validated to ensure accurate representation of combustion behavior. The simulation duration of 360 s reflects the critical early stage of fire development, which is crucial for evacuation and intervention assessment. Furthermore, additional monitoring points were implemented to improve data resolution, and the corresponding figure was updated. Despite these simplifications, the results offer practical insights applicable to multi-story buildings in Bucharest, providing valuable guidance for firefighters to anticipate smoke, heat, and toxic gas behavior during real interventions.

6. Conclusions

This study provides a quantitative assessment of the interaction between fire-source location and mechanical pressurization in high-rise stairwells, with direct implications for smoke control and firefighter safety. The results show that natural ventilation fails to maintain tenable conditions, while mechanical pressurization improves performance progressively with fire elevation, reducing temperatures and delaying smoke descent. However, single-point pressurization cannot ensure safe CO levels or adequate visibility near the fire source, confirming its practical limitations in real intervention scenarios.

Although these tendencies are consistent with the existing literature, this work advances current understanding by integrating temperature, visibility, and CO concentration analyses within a unified framework representative of Bucharest high-rise buildings lacking top exhaust openings. The findings bridge the gap between numerical modeling and operational decision-making, clarifying how ventilation mode and fire location jointly affect stairwell safety conditions.

The model, though simplified, was experimentally validated and designed to capture the early critical phase of fire development. Within these constraints, the results remain valid for comparable configurations and provide operationally meaningful insights for both safety engineers and first responders.

Future work should include upper-level smoke exhaust systems, multi-point adaptive pressurization, extended simulation durations, and an extension of the analysis to higher HRR fires, such as flammable-liquid scenarios. For a more comprehensive assessment, future studies may also integrate evacuation modeling tools, such as Pathfinder, alongside fire simulations to enable a coupled analysis of fire dynamics and occupant movement.

In conclusion, the study offers a concise and practical understanding of stairwell smoke behavior, supporting the design of adaptive, multi-zone ventilation systems and aiding firefighters in anticipating smoke and heat dynamics during real high-rise fire interventions.