Abstract

Precast concrete industrial buildings are typically characterised by high fire risk due to the production or storage of materials/products having high combustion potential and the specific activities carried out in the facility. Due to the large dimensions of these buildings, common simplified and ordinary advanced methods for the determination of the fire-induced demand, both in terms of structural performance and the safety of occupants and firefighters, may be far from accurate. Most large industrial buildings rely on translucid surfaces installed on the roof to let zenithal natural light enter the building. These are typically made with polycarbonate, and lateral windows may eventually be installed. Due to the low glass transition temperature of polycarbonate, these openings can efficiently act as evacuators of smoke and heat, although they are currently neglected by most practitioners, leading to the installation of mechanical evacuators. Moreover, the shape of the roof system of such buildings, especially if wing-shaped elements coupled with either vault or shed elements are used, can naturally ease the smoke and heat evacuation process. This paper aims to provide a contribution to the characterisation of fire development in such buildings, presenting the results of both zone and computational-fluid-dynamic analyses carried out on archetypal precast industrial buildings with a typical arrangement of either vault or shed roof subjected to cellulosic fire. For this purpose, several parameters were investigated, including roof shape (vault and shed) and the effect of short or tall columns. Concerning zone models, other relevant parameters, such as the type of glazing, the installation of smoke and heat evacuators on the roof, and larger window areas, were analysed.

1. Introduction

Industrial buildings are often prone to fire, mainly since many hosted activities involve the production, transformation, or storage of combustible materials. The Italian National Firefighters Brigade declared that 3436 interventions were carried out in industrial buildings (mainly precast) in 2024 alone [1], a small percentage of which could not avoid the development of severe fires. This raises concerns about the vulnerability of the existing industrial building stock in Southern Europe, most of which were neither designed nor conceived for fire resistance and protection, posing a technical/economic issue of their retrofitting. The modern fire safety design of such buildings often leads to the installation of active firefighting measures such as fire control systems (e.g., sprinklers) and mechanical smoke and heat evacuators on the roof that are activated at specified temperatures, typically between 68 °C and 141 °C, in order to delay the accumulation of hot gas in the environment, allowing for safer evacuation of the occupants and operation of fire brigades [2,3,4,5,6]. The interaction between sprinklers and vents was investigated in [7,8,9]. Such evacuators are typically designed by neglecting the presence of roof windows. This approach looks rational given glass is employed for glazing, with high temperature associated with its loss of functionality (typically around 400 °C [10]). However, industrial buildings typically employ chambered (often honeycomb) polycarbonate (PC) glazing, where such glazed surfaces lose consistency at the rather low temperature of around 140–150 °C [11,12,13], after their glass transition is initiated, progressively allowing passive smoke/heat evacuation capacity with increasing temperature. It should be noted that this temperature is not far from the upper bound of the range associated with the activation of the evacuators. Moreover, precast industrial buildings present different typologies of roof shape, which may be mainly divided into sloped [14] and corrugated (flat apart from the corrugation), the latter mainly associated with buildings built since the 1990s [15]. Corrugated roofs are typically made with prestressed wing-shaped roof elements [16,17] installed with a free distance and covered by completing shell elements, typically in the form of vaults or sheds (Figure 1). The shape of precast corrugated roofs is intuitively designed to passively allow for good exploitation of the potential of smoke and heat extraction through the PC windows in case of fire by conveying smoke and heat towards the opening located at the top.

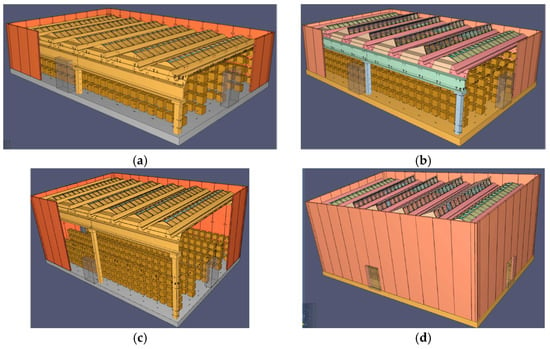

Figure 1.

Roof system for precast industrial buildings at study, with a combination of vault and shed elements: (a) external view; (b) internal view.

Nevertheless, the development of fires in this peculiar though rather common building configuration is not tackled in the current scientific literature. The issue of the transmission of smoke and heat in large atria, including the presence of vents in the roof, was previously investigated, although with reference to simpler geometries, in [18,19,20,21,22], where the theoretical background was also set. Nevertheless, due to the complexity of the geometry of the considered roof typologies, the theoretical formulations can hardly be extended to this case study. A solution can be found with the use of advanced numerical simulation, as also performed in a few previous investigation studies [23,24] tackling the effect of more complex geometries, although very different from the case study under consideration in this paper. A forensic investigation devoted to the analysis of a structural failure employing computational fluid dynamics (CFD) models was previously carried out in [25] in precast industrial buildings with corrugated roofs with vault-completing members. The investigated case study referred to a compartment at the higher floor of a multi-storey portion of a larger industrial complex, with limited height and specific fuel distribution and simplified combustion modelling. Hence, it may not be regarded as representative of the typical development of fire in industrial warehouses. Nevertheless, even in this investigation, the shape of the roof showed a strong influence over fire development, further fostering the motivation of this research.

The methods to simulate fire in terms of temperature time history consist mainly of simplified approaches assuming nominal or parametric temperature time history curves [26], neglecting both the nature of the combustible and the combustion process, with the latter only accounting in a simplified manner for the geometry and physical properties of the compartment structure. Ordinary advanced methods include single- or double-zone models, which may include refined properties of the combustion process [27].

Nevertheless, all the above-cited methods fail to accurately simulate fire in large compartments, mainly due to the assumption of constant thermo-physical properties in the whole considered zone.

CFD analysis can be used as an alternative sophisticated tool for the simulation of fires in such confined environments [28]. Despite the wide skills and multidisciplinary knowledge required by the user, as well as the high computational cost of such analyses, it can accurately simulate realistic fire events with several aims, including (I) to characterise realistic fire development; (II) to obtain the temperature time history of the air inside the compartment and around the structural elements; and (III) to check the evacuation process of occupants and/or the safe operation of firefighters. This is instrumental to further carry carrying out thermal mapping [29] and to predicting the resistance of compartment and structural elements [30,31].

2. Methods

This paper presents the results of fire simulations carried out on archetypal precast industrial buildings with either vaulted or shed roofs, representative of the majority of the precast industrial roofs built today in Italy and other countries. The main objectives of this research are the following: (a) to characterise the realistic fire development in such buildings considering the specific influence of the roof shape and zenithal window configuration; (b) to obtain the temperature time history of the air inside the compartment and around the structural elements, including specific vulnerable components (e.g., shed struts); (c) to analyse the efficiency of translucid PC windows installed in the roof as passive evacuators of smoke and heat; (d) to understand the role of several geometrical and combustion parameters on the development of fire; (e) to compare the results of different advanced approaches to the simulation of fires in such environments; (f) to check the dynamics of smoke layering associated with the safe exodus of the occupants.

The methodology employed is the following: the advanced numerical methods considered for selected representative case studies are both zone and CFD, despite the limitations previously illustrated regarding the employment of the zone models. The zone models, however, were selected for the rapid evaluation of the fire time histories and are therefore useful for carrying out comparative analyses. The investigated parameters include the height of the compartment, the presence of evacuators, the area of horizontal glazing (associated with vault or shed elements), and the typology of window glazing. The results, however, need to be interpreted taking into account the limitations of such models. Such limitations include the simplification of the roof shape into a flat shape, the mean thermo-dynamic parameters within each zone, and the simplified definition of the fuel, not accounting for propagation. CFD models were developed including all the previously described peculiarities not tackled by zone models, investigating a more limited number of parameters (roof shape and compartment height).

The geometry of the building and the typology and distribution of the windows were selected based on layouts and arrangements representative of typical applications. A single fuel type and ignition scenario were considered based on warehouses hosting cellulosic material. The combustion property of the cellulosic material was included in the model through the direct input of experimental data, as will be explained in detail in this paper. For all models, the effect of a sprinkler fire control system was not included, simulating existing buildings not complying with the most recent regulations, or recent buildings designed following a strategy not including the installation of such devices, or finally a possible failure of the installed sprinkler system due either to the pumping or to the plumbing system.

3. Case Study Buildings

The case study buildings are archetypal examples of precast concrete industrial buildings representative of the current production of such structures. These buildings are made with cantilever columns, prestressed beams, and wing-shaped roof elements, 6–12 m, 18 m, and 24 m long, respectively. The distance between adjacent roof elements is covered by reinforced concrete barrel vaults (Figure 2a) or reinforced concrete inclined shed elements supported by metallic struts (Figure 2b). It should be noted that two lines of vaults are placed at the ends of the shed roof as a standard practice. A total floor area of (2 × 19 + 2) m × (24 + 2) m = 988 m2 is considered in the two models. The clear height from the concrete pavement to the beam intrados was set equal to two different values: the value of 6 m is representative of short buildings, and the value of 12 m is representative of tall buildings. Precast concrete thermal-break panels external to the columns clad the building perimeter. One opening of dimensions 5 m × 3 m is inserted in the middle of each side of the building, simulating sectional doors. It is notable that this arrangement of lateral openings has a strong influence on the development of the fire. This configuration was selected since it is a sound option that allows the compartment to receive enough ventilation for the fire to not be hypoventilated early.

Figure 2.

Case study archetypal precast industrial structures with: (a) vaulted roof—6 m; (b) shed roof—6 m; (c) vaulted roof—12 m; (d) shed roof—12 m. In subfigures (a–c) the cladding panels are partially removed to allow for the visualisation of the internal fuel distribution.

It should be noted that the building structures receive light from zenithal windows located at the top of the vault elements or in the shed elements only. These windows are covered with translucid chambered PC panels. Vault windows have individual dimensions of 1.1 m × 0.6 m, with a total of 10.56 m2 per vault line. Shed windows are continuous with a total net translucid surface of 21.70 m2 per shed line.

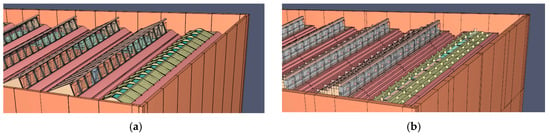

The shape of the elements was imported into the graphical interface Pyrosim [32], release 6.8.0, from an interchange .ifc extension file of a Building Information Modelling (BIM) source.

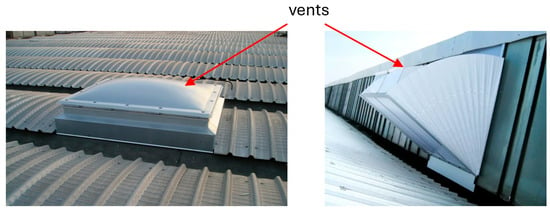

The buildings, if constructed following the current fire regulations in Italy, could have been protected by an active fire control system (e.g., sprinkler), according to the strategy chosen by the designer [2,33]. In addition, vents for a faster evacuation of smoke and heat would be installed in the roof, despite the large area of windows typically made of low-temperature-melting PC honeycomb glazing. Typical vents for natural ventilation installed in industrial building roofs are shown in Figure 3, including both configurations for barrel vaults and for sheds. They can be designed following a simple conservative prescription of a minimum ventilation surface of 1/40 to 1/25 of the floor area depending of the fire load (leading to 24.7 m2 to 39.5 m2 of ventilation surface – the latter associated with the fire load if the case study, with the prescription to install 4 m2 of vents) or, alternatively, their design can follow the specific Italian norm UNI 9494 [34]. The application of this standard would lead to the installation of a minimum vent surface of 6.1 m2 and 3.5 m2 for the 6 m tall and for the 12 m tall buildings, respectively, assuming a height of the smoke interface of 3 m above the pavement. The presence of vents is included in the parametric analysis carried out with the zone models.

Figure 3.

Typical smoke and heat natural evacuation vents installed in precast industrial buildings with either vaults or sheds.

4. Results

4.1. Zone Models

Numerical analyses employing zone models were carried out using the software Ozone [35,36], rel. 3.0.4, with the aim of simulating the cellulosic fire scenario considered with a fast-processing method. This method presents the previously cited important limitations, which should be taken into account for a proper interpretation of the results. Thus, the results presented in this section are mainly considered sound in terms of comparison of the different parameters analysed. The main input data are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Parameters employed for the zone analysis.

In the definition of the compartment geometry, the roof height was set equal to the clear distance below the beam, i.e., alternatively 6 m and 12 m. The lateral sectional doors were modelled, assuming they were constantly open. The properties of the surrounding opaque surfaces were considered in terms of the equivalent thickness of concrete. Indeed, the presence of insulation materials, typically expanded polystyrene (EPS), positioned both inside the elements (this is the case of the sandwich thermal-break cladding panels) and outside the elements (this is the case of the roof), was neglected due to the early degradation of the thermos-physical properties of EPS [37,38,39]. This simplistic assumption will be proven to be sound from the analysis of the results of the CFD analysis in the next chapter, where it is clearly shown that the heat power transmitted by the conductivity of the compartment surfaces is negligible with respect to convection and radiation mechanisms.

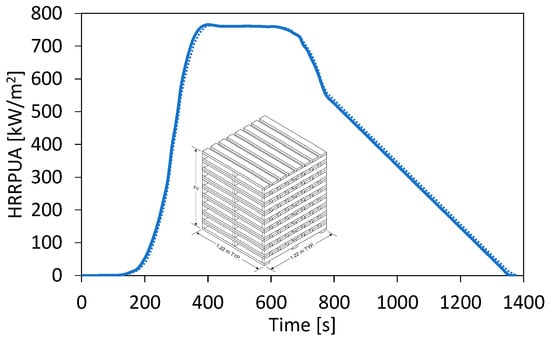

As fuel, cellulosic materials were selected. The definition of the combustion properties was carried out fully based on experimental data. In particular, the curve of heat release rate per unit area (HRRPUA) shown in Figure 4 was derived based on the experimental heat release rate (HRR) curve associated with burning of a wood crib with a side equal to 1.22 m and a height of 1 m below an oxygen-consumption calorimeter, as described in the SPFE handbook [40]. In particular, the original HRR curve was modified initially adjusting the recorded value over time up to the assumed complete combustion of the crib [41]. This was performed with a linear softening branch by imposing to the curve a total fire load of 2521 MJ, based on the evaluation of its integral function (Figure 3). The HRR curve was then divided by the exposed surface of the original test specimen.

Figure 4.

Wood crib combustible modelling: HRRPUA attributed to block surfaces.

Assuming a sound distribution of fuel in the compartment following a grid of 24 by 5 by 4 elements having a volume of 1 m3, as shown in Figure 2, a specific fire load distribution spread on the floor of about 1600 MJ/m2 was considered (independent of the building height). It should be noted that, following the Eurocode 1 [26] approach, this corresponds to a characteristic fire performance request of 120 min.

The combustion properties were then introduced in the software in terms of HRR, by scaling over the ordinates the HRRPUA curve by the sum of the surface of the timber cubes [42]. This corresponds to a curve of HRR with a maximum power of 2203 MW. Since this is a direct experimental input, the coefficient of efficiency of the combustion was taken as unitary. Moreover, a stoichiometric coefficient of 1.27 was selected as an input, associated with the combustion of timber [35,36]. Of note is that the curve was not modified, accounting neither for ventilation nor for propagation. The effect of ventilation may have damped the HRR peak and extended the duration of the fire, as indeed the software does automatically, given the “extended fire duration” option is selected. The effect of fire propagation through adjacent fuel cubes would have extended the first ascending branch of the full curve, where the actual input curve assumes that all cubes ignite simultaneously. This is, however, not possible with the selected software, unless indirectly acting on the input HRR curve with uncertain assumptions. Therefore, it is to be remembered that the results of the zone models shown in the following are much more severe than a real fire in the early stage of fire propagation.

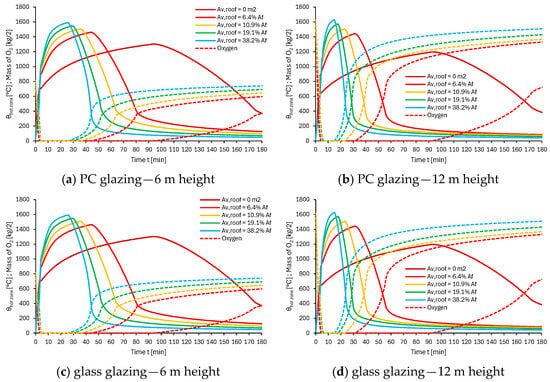

The results of combined models (two zones collapsing into a single zone when the flashover condition is met) are reported in Figure 5 in terms of hot zone temperature and oxygen mass time histories, for different degrees of opening area, expressed as a percentage of the floor area. The case study vault and shed configurations are represented by 6.4% and 10.9%, respectively. Moreover, a lower bound condition without openings was investigated, as well as conditions with larger window areas on the roof, 3 and 6 times larger than that associated with the vault configuration.

Figure 5.

Hot zone temperature and oxygen mass time histories.

The results indicate that in all cases the fire is governed by a lack of ventilation, at least during the peak phase, as indicated by the plot of the mass of oxygen in the compartment. Larger ventilation areas are associated with higher temperature peaks (up to 1600 °C) and a shorter duration of the severe phase of the fire. The building height clearly influences fire development, with taller buildings associated with similar temperature peaks but shorter duration of the severe phase, showing a better efficiency in wasting smoke and heat. Negligible differences are noted between the cases with PC and glass windows, apart from the first minutes of the fire development. This is due to the rapid temperature rise, which takes a very limited amount of time (a few minutes) to increase by several hundreds of degrees at the top. This also leads to the observation that smoke and heat evacuators play a very limited role in the definition of the whole fire.

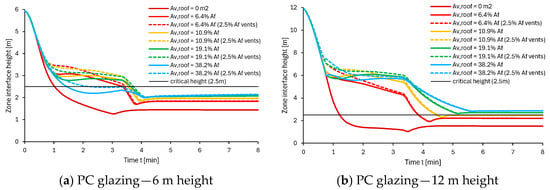

In order to better investigate the effect of the type of glazing and the possible presence of smoke and heat evacuators in the roof, specific analyses were conducted by refining the numerical integration in the early stage of the analysis, selecting a two-zone model in order to investigate the time history of the zone interface height. For the models with smoke and heat evacuators, the options of a large area of 1/40 of the floor surface (larger than the minimum required with both prescriptive and performance approaches, as described above) and lower activation temperature of 68 °C were selected, providing the best evacuation measure to be reasonably designed for the building. It is recalled that the zone models provide conservative results in terms of smoke and heat layering in the compartment, since all the combustible is assumed to take fire instantaneously, and thus the results need to be considered comparatively. The results, shown in Figure 6, highlight a less clear dependence of the smoke layering with time on the window area. As expected, the lower bound is always attained without roof openings. However, in the case with a building height of 6 m, the interface lowers earlier with a larger opening area, indicating the predominant effect of the larger oxygen inlet with respect to the larger evacuation, whereas in the case of a building height of 12 m, the case with lower window area appears to be more severe. Moreover, there are limited differences within the cases with lower and larger glazing surfaces. The building height plays a role in this parameter, with the lower building associated with more rapid layering of smoke and heat down to the area of interest for the safe evacuation of the occupants. In this short initial time window, there is a remarkable difference between PC and glass glazing. In particular, the cases with glass windows allow the interface to get lower than 2.5 m before the windows lose integrity in all analyses, whereas in the cases with PC windows they lose integrity much earlier, allowing for a better performance in terms of delaying the interface quote to lower. This also explains why the efficiency of the evacuators seems limited when PC windows are used. Nevertheless, the installation of the evacuators proves to be efficient in the case where glass windows are used.

Figure 6.

Early time history of the hot-cold zone interface height.

4.2. CFD Models

The CFD numerical models of selected cases were developed with the software Pyrosim rel. 2025.1 [32], acting as a graphical interface for the instruction of the input files for Fire Dynamics Simulator (FDS) software rel. 6.10.1 [43]. The thermo-physical properties of concrete structural elements, steel struts (for the shed roof only), and translucid surfaces were attributed to the model. Moreover, all PC windows were provided with a logic command so that they were removed when the temperature reached 150 °C, simulating a loss of integrity of the PC after such a temperature. Side doors were assumed to be constantly open throughout the analysis.

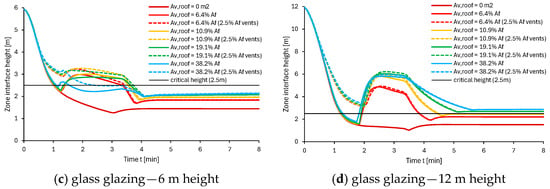

A regular distribution of cellulosic combustible was implemented in the form of cubic boxes of 1 m3, distributed simulating an accumulation of piled material beside distributive corridors, as shown in Figure 2. The boxes were placed at a relative distance of 0.4 m in the vertical and in the horizontal direction parallel to the corridors.

To each side of the boxes, the curve of heat release rate per unit area (HRRPUA) shown in Figure 4 was attributed based on the assumptions previously described. One box placed at the bottom level in the centre of the building plan was assumed to be the fire starter (burner), as shown in Figure 7. The fire propagation was included in the models, simulating realistic travelling fires [44], with an ignition temperature of the wood of 245 °C [40]. Concerning the combustion parameters, a simple chemistry reaction relative to red oak wood was selected, as well as a CO yield parameter of 0.004 and a soot yield of 0.015 [40]. Thermocouple and radiative flux measuring devices were placed along all structural elements, in several points within the environment, and over the PC surfaces, as previously explained. Moreover, several control plans, both vertical and horizontal, were set.

Figure 7.

Position of the burner.

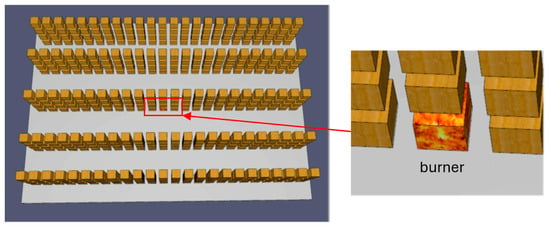

The dimension of the mesh in FDS was selected on the basis of the D* criterion [45] (Equation (1)), also known as the Froude number criterion, resulting in two zones; the bottom zone of the building was meshed with elements with a side of 50 cm. The upper zone, where the area of interest and of complex geometry for the simulation is located, was meshed with elements having a side of 25 cm. A picture with a detailed view of a model, as imported from the BIM software and after discretisation, is shown in Figure 8.

where:

| Q′ is the maximum heat release rate (RHR) of the fire | [kW]; |

| ρ∞ is the air density | [kg/m3]; |

| cp is the air specific heat | [kJ/kg K]; |

| g is the gravitational constant | [m/s2]; |

| T∞ is the ambient temperature | [K]. |

Figure 8.

Numerical model: (a) geometrical model as imported from BIM into interface software; and (b) discretised numerical model.

Computing the analyses required around 2 weeks per analysis on a multi-processor employing 24 cores in parallel. The parallel computing was carried out by attributing a portion of the total mesh to each core processor. A series of preliminary calibration/verification analyses required about another month, which brought to the main result of including the four base openings, which was initially imposed as only one, due to their high influence over the results. A single opening resulted in a fire severely controlled by oxygen supply, thus more conservative with respect to the ones obtained in the final analyses, which are deemed to simulate a more severe though more realistic fire scenario [46], assuming that the sectional doors become permeable to air at a relatively low temperature, or that they are open during the first ignition.

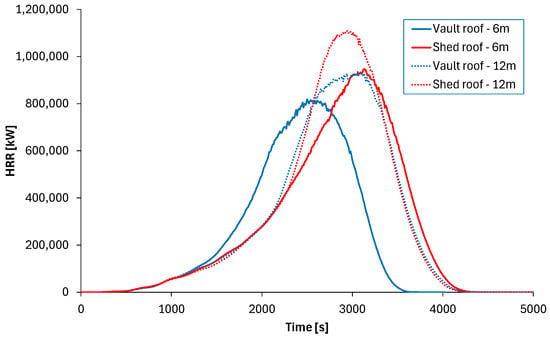

Figure 9 shows the resulting HRR curves. Very high peak HRR was obtained for all curves, associated with specific values of about 850 kW/m2 to 1100 kW/m2 for vault short and shed tall roof, respectively. However, it is worth noting that such a peak is only indicative, since the thermal power associated with flames burning out of the numerical domain (out of the windows and further out of the domain layer of about 1 m) is lost. Therefore, the HRR peak shall be interpreted as a lower bound result.

Figure 9.

Output HRR curves.

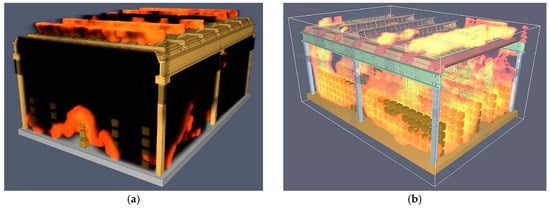

The fire progressively propagated from the starter box (burner) following the upward curve of the HRR diagrams, attaining a flashover condition after around 2200 s from the ignition for the model with a vault roof (Figure 10a) and soon after for the model with a shed roof (Figure 10b).

Figure 10.

Flashover phase: (a) vaulted roof 12 m (view with smoke); (b) shed roof 12 m (view without smoke). Cladding panels are removed from the visualisation for better clarity.

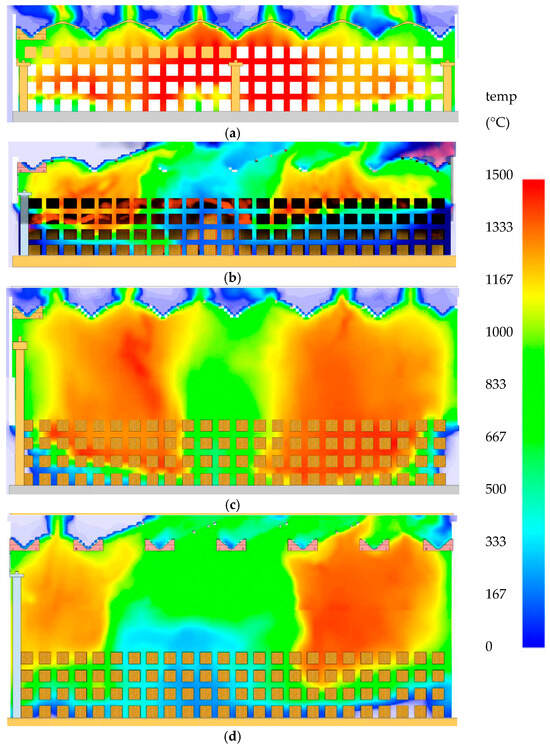

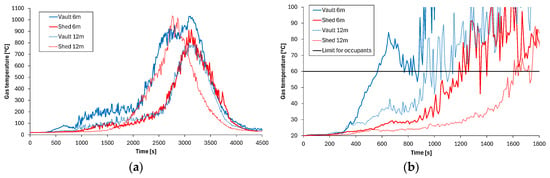

The temperature distribution shown in Figure 11 for an instant of generalised fire shows that, even after flashover occurred, there was a relevant gradient of temperature in the environment, confirming that zone or simpler models would be highly approximated. Moreover, a lower temperature in the centre of the building can be observed in some post-flashover contour plots: the central combustible boxes burn earlier, and when flashover occurs, they have a low residual fire load. This effect is typical of propagating (or travelling) fires [44].

Figure 11.

Temperature over central slice parallel to beams at flashover: (a) vault roof 6 m; (b) shed roof 6 m; (c) vault roof 12 m; (d) shed roof 12 m.

Figure 11 also clarifies how the smoke/heat evacuation flow differs between the different roof configurations: vaults convey smoke/heat at their top, leading to a vertical dispersion in the outer environment; shed elements create an inclined flow. It is interesting to observe that, due to the inclined smoke/heat flow across the shed elements, hot gases are brought above the reinforced concrete shed and wing-shaped roof elements, which is typically neglected in ordinary design.

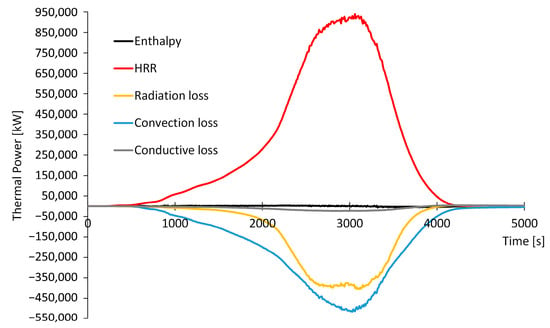

The power time histories associated with both the input HRR and the output heat dispersion mechanisms are shown in Figure 12 for the analysis with the vault roof and a lower building height. The plots clearly show that the heat dissipation mechanism occurs predominantly by convection, i.e., by the evacuation of smoke and heat through the openings. The radiation contribution is lower, but still comparable. The conduction contribution through the opaque building envelope surfaces appears to be very limited, to the extent that it might be considered negligible. Other contributions, such as air pressure change or expansion of gases, are not even represented, since their values are extremely low and definitely negligible. The plot of the enthalpy shows limited resulting powers, positive in the first part of the fire (around pre-peak), where the production of heat is predominant, and negative in the second part of the fire (around post-peak) due to the predominant smoke and heat evacuation term.

Figure 12.

Thermal power balance time history in the compartment for a single analysis (vaults—6 m).

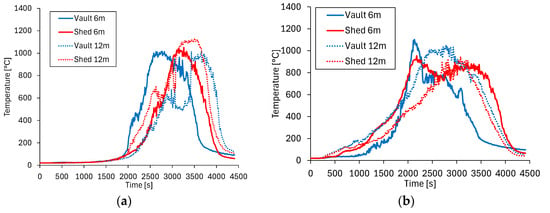

The gas temperature time history near the structural elements is plotted in Figure 13a–c, in terms of peak curves for columns, beams, and wing-shaped roof elements, respectively. These temperature profiles come from AST devices, including both convection and radiation heat transfer mechanisms. It is relevant that relatively high peak values of temperature were obtained around the main structural elements, in the range of 900–1100 °C for columns and beams in all analyses, as well as for roof members for the tall column configurations only. This finding is in line with the ISO834 curve, which for 120 min of exposition gives a temperature of 1045 °C. However, for short column configurations, the flames efficiently engulf the roof elements, making their peak temperature rise to the range of 1200–1400 °C, remarkably higher than what ISO834 would have suggested. Nevertheless, the time span of the generalised strong fire is much more limited in all cases, in the range of 15–30 min. This is deemed to be very positive for the behaviour of reinforced concrete structures, which thanks to their low thermal diffusivity, are sensible not only to the peak temperature, but especially to the duration of the strong fire.

Figure 13.

Temperature distribution over main roof elements: (a) one lateral column top; (b) one beam midspan; (c) the central roof element at midspan; (d) metallic shed struts.

A more severe risk scenario concerns the inclined metallic struts supporting shed elements. As shown in Figure 13d, their peak temperature is higher, up to 1250 °C, due to their presence within the main evacuation flow of smoke/heat. Since steel structures are typically more vulnerable to peak temperature, rather than to the duration of the strong fire, this result highlights their potential vulnerability.

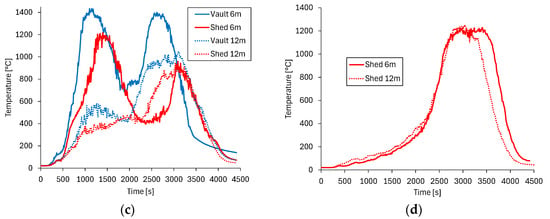

Concerning the capacity of evacuation of the occupants, indirect information can be obtained from the fire simulations. In particular, both the temperature distribution in the environment and the height of accumulation of smoke were considered as parameters determining the ability of evacuation. In this regard, AST devices accounting for radiative flow contribution were positioned in the environment, within the distribution corridors of the warehouse building, at a height of 2.5 m. The height of 2.5 m indicates potential danger for the interaction with the occupants. The most severe readings of selected devices are shown in Figure 14. The results confirm that the temperature time history at different heights is significantly different, with dangerous temperatures attained much earlier near the roof than at the base of the building, as observable with the comparison with the temperature time histories plotted in Figure 13.

Figure 14.

Temperature time histories from sensors positioned in the free air within the distribution corridors of the building: (a) along the full analysis; (b) in the initial time window during fire propagation.

The efficiency of smoke/heat evacuation passively provided by PC glazing is noticeable from the results summarized in Table 2, with reference to typical parameters relevant for the safe evacuation of occupants in terms of time from ignition to measure a temperature higher than 60 °C and time for smoke accumulation at a height of 2 m above the pavement. Moreover, Table 2 shows the time necessary to attain the glass transition temperature for the first PC window. Even though complete melting and falling off of PC windows occurs at slightly higher temperature than that of glass transition, this time is indicative of the potential fall of molten PC over the occupants during their evacuation. However, it is to be considered that the melting of PC windows occurs practically over the open flames, far from the escape paths potentially useful for the occupants.

Table 2.

Results of parameters relevant for evacuation.

The results clearly indicate that the shed roof arrangement allows a longer evacuation time, mainly due to the almost double area of glazing, as mentioned above. Nevertheless, the time allowed even by the vault roof configuration allows a larger window than what is typically needed to evacuate single-storey industrial buildings. It is notable that smoke accumulation is found to clearly be the critical parameter for vault roof configurations with both short and tall columns. Alternatively, the time limits associated with shed roof configurations associated with temperature and smoke accumulation parameters are rather similar, with temperature prevailing for short column configurations and smoke accumulation prevailing for tall column configurations. Moreover, tall column configurations correspond to increased evacuation time limits compared to short column configurations.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The advanced fire simulations carried out allowed for the characterisation of fire in particularly large industrial compartments, in terms of heat production and dispersion mechanisms, fire propagation, and passive evacuation of smoke and heat, mainly from the roof glazings.

The comparison of the results of zone models, where the fire propagation is not modelled and, hence, the results are associated with the conservative assumption that all the fuel simultaneously catches fire, yielded the following results:

- The type of glazing, and the possible presence of smoke and heat evacuators on the roof, play a negligible role in the development of the full fire time history.

- All simulations show natural fires that are controlled by ventilation, even if restricted to the most severe time window of the fire. The time duration of the severe fire phase is significantly greater for the building with a lower height, while the peak temperature is indeed similar for all compartment heights.

- A larger glazed surface on the roof corresponds to a shorter severe fire phase and a higher peak temperature, ranging from about 1200 °C to about 1600 °C.

- In the early phase of fire development, however, the type of glazing plays a role in the height of the hot gas layer, with unsafe configurations where glass is employed, and generally much safer configurations when PC is employed.

- For the configurations with glass glazing, the presence of heat and smoke evacuators is beneficial to avoid early accumulation of hot gases down to heights dangerous for the evacuation. No particular benefits are observed when large heat and smoke evacuators are employed in combination with PC windows.

The analysis of the results of CFD models, where the fire propagation is properly modelled, yielded the following results:

- Severe peak temperatures resulted from the simulations, in the range of 900–1100 °C, for all main structural elements, except for the roof elements in the configurations with short columns, where peaks as high as 1400 °C were detected, mainly due to the efficient engulfment of the roof elements in fire. This is, as expected, less conservative, though in line with the results of the zone models.

- This suggests that preventing efficient flame engulfment of the roof, keeping a proper clearance between the taller position of combustible material and the roof itself, may be suggested as a passive measure of containment of the high temperatures.

- Despite such high temperatures, in line or higher than the equivalent ISO834 demand of 1045 °C following the traditional design approach from Eurocodes, there is a significant lowering of the time window associated with the severe fire phase. In the analysis, such severe fire phase lasted in the range of 15 to 30 min, which is remarkably lower than the standard nominal fire curve at 120 min, as also pointed out by the zone analysis.

- This is indeed a positive feature for reinforced concrete members, which due to their low thermal diffusivity, typically suffer from fires having a long duration of the severe phase.

- Concerning the shed roof configurations, high peak temperatures of about 1200 °C were obtained around the sheds. This poses questions about the performance of the exposed steel struts supporting windows and reinforced concrete shed plates.

- It is observed that the shape of the roof is very efficient in conveying heat and smoke to the windows, with temperature rises over the exposed wing-shaped roof members in case inclined evacuation is adopted (i.e., shed roof configuration).

- Concerning the indirect information about the evacuation of occupants from the fire simulation, it was found that the available evacuation time prior to the exposure to smoke or unbearable temperature is, for all cases, larger than 6 min, typically more than what is required for the evacuation of such premises.

- Shed configurations, allowing an almost double area of PC glazing, provide the most efficient passive evacuation mechanism of heat and smoke, after the polymeric glazing attains glass transition and loses integrity.

- Moreover, taller building configurations allow a delayed time limit for temperature rise and smoke accumulation at the bottom of the building.

The presented simulations allowed the characterisation of the demand induced by fire to both structures and occupants for an archetypal modern precast concrete industrial building, providing interesting insights that contribute to filling the knowledge gap in the field. However, the generalisation of the results is possible only upon careful consideration, taking into account that differences in building geometry, as well as in the nature and distribution of the fuel, may strongly influence the results of different fire scenarios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.D.L.; methodology, B.D.L. and P.T.; software, B.D.L., F.R., and P.T.; validation, B.D.L., F.R., and P.T.; investigation, B.D.L., F.R., and P.T.; resources, B.D.L.; data curation, F.R.; writing—review and editing, B.D.L.; supervision, B.D.L. and P.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

Thunderhead Engineering of Manhattan, Kansas (USA), is gratefully acknowledged for providing the academic waiver for the use of the software Pyrosim. The developers of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) of Gaithersburg, Maryland, are gratefully acknowledged for providing the open-source software FDS. The BIM operators of DLC Consulting s.r.l. of Milan are gratefully acknowledged for building and providing the source 3D models of the case study buildings.

Conflicts of Interest

The first author is the founder and shareholder of DLC Consulting s.r.l. and a consultant active in the field of design of precast structures, among others. However, the author does not envisage a particular benefit to the activity of the consultant from the work described in this paper. The remaining authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Italian Ministry of Interior, Department of Firefighters, Public Rescue and Civil Protection, Central Committee for the Technologic Innovation, Digitalisation, and Logistic-Instrumental Resources. Annuario Statistico del Corpo Nazionale dei vigili del Fuoco. 2025. Available online: https://www.vigilfuoco.it/chi-siamo/le-statistiche/annuari-delle-statistiche-ufficiali-del-corpo-nazionale-dei-vigili-del-fuoco (accessed on 21 December 2025). (In Italian).

- Ward, E.J. Automatic Heat and Smoke Venting in Sprinklered Buildings; Technical Report; Factory Mutual Research Corporation: Norwood, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Elovitz, K.M.; Elovitz, D.M. Understanding smoke management and control. ASHRAE J. 1993, 35, 34–37. [Google Scholar]

- Elovitz, D.M. Evaluating smoke control and smoke management systems. ASHRAE J. 1996, 38, 46–54. [Google Scholar]

- Krisman, A.; Gopala, Y. Gravity Smoke Vents in Storage Occupancies; Technical Report January; Factory Mutual Research Corporation: Norwood, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- NFPA 204; Standard for Smoke and Heat Venting. National Fire Protection Association: Quincy, MA, USA, 2021.

- Heskestad, G. Model Study of Automatic Smoke and Heat Vent Performance in Sprinklered Fires; Project ID 21933; Factory Mutual Research: Norwood, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Hinkley, P.L.; Hansell, G.O.; Marshall, N.R.; Harisson, R. Large-scale experiments with roof vents and sprinklers Part 2: The Operation of Sprinklers and the Effect of Venting with Growing Fires. Fire Sci. Technol. 1993, 13, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyler, C.L.; Cooper, Y. Interaction of Sprinklers with Smoke and Heat Vents. Fire Technol. 2001, 37, 9–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, J.; He, L.; Wang, Q.; Rush, D. Experimental study on fallout behaviour of tempered glass façades with different frame insulation conditions in an enclosure fire. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2019, 37, 3889–3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.S.; Chow, W.K. Cone calorimeter studies on fire behavior of polycarbonate glazing sheets. J. Appl. Fire Sci. 2004, 12, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazzawi, Y.M.; Osorio, F.A.; Heitzmann, M.T. Fire performance of continuous glass fibre reinforced polycarbonate composites: The effect of fibre architecture on the fire properties of polycarbonate composites. J. Compos. Mater. 2018, 53, 1705–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, B.; Jiang, Q.; Xu, W.; Wang, L.; Luo, Z.; Wang, B. A nitrogen-rich DOPO-based phosphoramide for improving the fire resistance of polycarbonate with comparable mechanical property. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2023, 140, e54513. [Google Scholar]

- Dal Lago, B.; Nicora, A.; Tucci, P.; Panico, A. Precast concrete industrial portal frames subjected to simulated fire. Lect. Notes Civil. Eng. 2023, 350, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bosio, M.; Di Salvatore, C.; Bellotti, D.; Capacci, L.; Belleri, A.; Piccolo, V.; Cavalieri, F.; Dal Lago, B.; Riva, P.; Magliulo, G.; et al. Modelling and seismic response analysis of non-residential single-storey existing precast buildings in Italy. J. Earthq. Eng. 2023, 27, 1047–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Lago, B. Experimental and numerical assessment of the service behaviour of an innovative long-span precast roof element. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2017, 11, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capacci, L.; Dal Lago, B. Structural modelling and probabilistic seismic assessment of existing long-span precast industrial buildings. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2025, 23, 2581–2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lougheed, G.D.; Hadjisophocleous, G.V. Investigation of Atrium Smoke Exhaust Effectiveness; ASHRAE Transactions, Symposia, BN-97-5-1; ASHRAE: Peachtree Corners, GA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Klote, J.H. Prediction of Smoke Movement in Atria: Part I and II; ASHRAE Transactions: Symposia; ASHRAE: Peachtree Corners, GA, USA, 1997; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, T.; Yamana, T. Smoke Control in Large Scale Spaces (Part 1: Analytic Theories for Simple Smoke Control Problems); Building Research Institute, Ministry of Construction: Tokyo, Japan, 1985.

- Tanaka, T.; Yamana, T. Smoke Control in Large Scale Spaces (Part 2: Smoke Control Experiments in a Large Scale Space); Building Research Institute, Ministry of Construction: Tokyo, Japan, 1985.

- Gordonova, P. Smoke and Fire Gases Venting in Large Industrial Spaces and Stores; Technical Report TVIT–04/3001; Lund University: Lund, Sweden, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Top, S.M. The effect of domed and hip roof coverings on mosque design in case of fire. J. Eng. Res. 2023, 11, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malendowski, M.; Gglema, A.; Kurzawa, Z.; Polus, L. Structural response under natural fire of barrel shape shell construction. In Proceedings of the International Conference, Prague, Czech Republic, 19–20 April 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dal Lago, B.; Tucci, P. Causes of local collapse of a precast concrete industrial roof after a fire event. Comput. Concr. 2023, 31, 371–384. [Google Scholar]

- CEN-EN 1991-1-2; Eurocode 1: Actions on Structures, Part 1–2: General Actions—Actions on Structures Exposed to Fire. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2002.

- Cadorin, J.-F.; Pintea, D.; Franssen, J.-M. The Design Fire Tool OZone V2.0—Theoretical Description and Validation On Experimental Fire Tests; Internal Report SPEC/2001_01; University of Liège: Liège, Belgium, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- de Silva, D.; Sassi, S.; De Rosa, G.; Corbella, G.; Nigro, E. Effect of the fire modelling on the structural temperature evolution using advanced calculation models. Fire 2023, 6, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolina, F.L.; Dal Lago, B.; Martínez, E.D.R. The effect of experimental thermal-physical parameters on the temperature field of UHPC structures in case of fire. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 411, 134254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolina, F.L.; München, R.M.; Dal Lago, B.; Kodur, V. A comparative study between ultra-high-performance concrete structures and normal strength concrete structures exposed to fire. Structures 2024, 68, 107197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolina, F.L.; Henn, A.; Dal Lago, B. Simplified design procedure for RC ribbed slabs in fire based on experimental and numerical thermal analysis. Buildings 2025, 15, 1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thunderhead Engineering. PyroSim: A Model Construction Tool for Fire Dynamics Simulator (FDS). In PyroSim User Manual; Thunderhead Engineering: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Italian Ministry of Interior, Department of Firefighters, Public Rescue and Civil Protection, Central Committee for Prevention and Technical Safety. Decreto 3 Agosto 2015 (G.U. 20 agosto 2015, n. 192—SO n. 51) e Successive Integrazioni. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2015/08/20/15A06189/sg (accessed on 21 December 2025). (In Italian).

- UNI 9494-1:2017; Sistemi per il Controllo di Fumo e Calore—Parte 1: Progettazione e Installazione dei Sistemi di Evacuazione Naturale di Fumo e Calore (SENFC). UNI: Milan, Italy, 2017. (In Italian)

- Cadorin, J.-F.; Franssen, J.-M. A tool to design steel elements submitted to compartment fires—OZone V2. Part 1: Pre- and post-flashover compartment fire model. Fire Saf. J. 2003, 38, 395–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadorin, J.-F.; Pintea, D.; Dotreppe, J.-C.; Franssen, J.-M. A tool to design steel elements submitted to compartment fires—OZone V2. Part 2: Methodology and application. Fire Saf. J. 2003, 38, 429–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Yoshioka, H.; Noguchi, T.; Ando, T. Experimental study of expanded polystyrene (EPS) External Thermal Insulation Composite Systems (ETICS) masonery façade reaction-to-fire performance. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2018, 8, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, W.; Jiang, L.; Sun, J.; Liew, K.M. Correlation analysis of sample thickness, heat flux, and cone calorimetry test data of polystyrene foam. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2015, 119, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Gou, F.; Wang, Y.; Sun, J. Melt-flowing of expanded polystyrene in large-scale discrete flame spread. Fire Saf. J. 2024, 142, 104011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SFPE Handbook of Fire Protection Engineering, 3rd ed.; National Fire Protection Association, Society of Fire Protection Engineers: Quincy, MA, USA, 2002.

- Babrauskas, V. Ignition of Wood: A Review of the State of the Art. J. Fire Prot. Eng. 2002, 12, 163–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Alam, N.; Liu, C.; Nadjai, A.; Rush, D.; Welch, S. Scaling-up’ fire spread on wood cribs to predict a large-scale travelling fire test using CFD. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2024, 189, 103589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrattan, K.; McDermott, R.; Hostikka, S.; Floyd, J.; Vanella, M.; Weinschenk, C.; Overholt, K. Fire Dynamics Simulator, 6th ed.; NIST Special Publication 1019; NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2017.

- Charlier, M.; Glorieux, A.; Dai, X.; Alam, N.; Welch, S.; Anderson, J.; Vassart, O.; Nadjai, A. Travelling fire experiments in steel-framed structure: Numerical investigations with CFD and FEM. J. Struct. Fire Eng. 2021, 12, 309–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USNRC; EPRI. Verification and Validation of Selected Fire Models for Nuclear Power Plant Applications, Volume 1: Main Report; NUREG-1824 and EPRI 10 11999; U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Office of Nuclear Regulatory Research (RES): Rockville, MD, USA; Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI): Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2007.

- Rizzo, F. Simulazione con Modelli di Campo di Incendi in Ambienti Industriali con Differenti Tipologie di Copertura. Master’s Thesis, University of Insubria, Varese/Como, Italy, 2024. (In Italian). [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.