Abstract

Sedimentary charcoal has been used to reconstruct past fire for over 80 years, but as we try to answer more nuanced questions about the complex interactions between fire, climate, vegetation, and human management, we need tools that can reconstruct specific aspects of past fire regimes. Here, we focus on recent advances in fire intensity reconstruction from sedimentary charcoal, with emphasis on optical reflectance, spectrographic, and geochemical methods. We summarize their origin and basis, before discussing next steps in development to maximize their utility and research impact.

1. Introduction

Wildfire causes 1.53 million deaths each year from emissions alone [1] with 402 Mha burned on average globally from 2001–2024 [2]. While there are many persistent questions about wildfire in the research literature, particularly as it applies to fire management, for at-risk communities the key concerns are the following: “Is fire getting worse?” and “How much worse will it get?” Answering these questions requires region-specific baselines of fire and time-series that exceed the instrumental record [3,4], and even deep-time (pre-Quaternary) analogs for the future climate [5], to constrain the relationships between vegetation [6], climate [7], human management and impacts [8,9], and fire.

The impact of fire is contingent on the multiple characteristics represented in a fire regime. These include the following: spatial characteristics such as the size of the fire (total burned area) and its spatial complexity (variability in severity within the perimeter); temporal characteristics, such as how often fires occur (frequency or fire-return interval) and when the fire occurs (seasonality); and characteristics that describe the fire’s magnitude, such as the loss of organic matter both above- and below-ground caused by fire (severity), the energy or heat released at the fire line (kW/m; fireline intensity) or integrated over the phases of a fire (kW/m2; reaction intensity), and the flaming front pattern (fire type; e.g., surface, passive crown, active crown, and independent crown fires) [10,11]. Fire regimes are determined by factors such as vegetation or fuel type, topography, and meteorological variables such as “fire weather” [12] and so are variable in space and dynamic in time. Depending on the fire regime, impacts may include temporary or sustained loss of, or change in, vegetative cover and community composition, altered habitat characteristics and biodiversity, interaction with other disturbance regimes and landscape stability, alteration in biogeochemical cycling, and changes to air quality, greenhouse gas and aerosol emissions, and albedo resulting in feedback to climate change [13,14,15,16,17]. Increasing impacts on human systems are also possible with changing fire regimes, and this might include loss of life and impacts on human health, property damage, agricultural losses or other impacts on productivity, insurance, emergency preparedness, or natural resources [18,19,20].

Answering the increasingly complex questions about the causes and consequences of fire requires the perspective of long timescales combined with increasingly sophisticated proxies that reflect the distinct components of the fire regime. Here we focus on a seemingly simple question: what can the accumulation of charcoal in sedimentary records tell us in terms of past fire in the landscape? We extend this focus to recent advances in the reflectance/absorption (in visible light), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), and Raman properties of charcoal, and geochemical indicators in sediments (e.g., polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), levoglucosan), which are linked to fire intensity. We contend that parsing out well-defined aspects of fire regimes in proxy records better facilitates our understanding of the drivers of change.

Throughout, we refer to charcoal, which has a high carbon content, condensed aromatic molecular configuration, and anatomical preservation. However, the products of pyrolysis of organic matter exist on a continuum, from material with little thermal alteration, through to incomplete combustion leading to amorphous carbon residues, charcoal, and ash as an end product [21]. Organic matter preserved in the sedimentary record, which has been exposed to the lowest-intensity fires, may be more accurately referred to as charred or char rather than charcoal.

2. What Does Sedimentary Charcoal Tell Us?

Initial applications of charcoal analysis were largely qualitative, with the presence of charcoal in sedimentary archives interpreted as evidence of fire occurrence. Charcoal particles were noted by Iversen [22] on pollen slides from Danish peat and lake sediments, and from this he inferred anthropogenic burning in Neolithic landscapes. Iversen observed that layers with increased charcoal often coincided with declines in forest taxa and rises in herbaceous pollen, suggesting a link between fire and vegetation change. These observations established that charcoal preserved in sedimentary archives, such as lakes and bogs, could serve as a proxy for past fire, although the proxy was not adopted by others until the mid-1960s [23].

The shift from qualitative charcoal presence to systematic counting began in the 1970s [24] when paleoecologists developed methods to quantify charcoal in sediment samples and account for sedimentation rate. As a metric, charcoal accumulation rate (and its shorthand CHAR [25]) is now ubiquitous, and allows comparisons of fire activity between different periods and sites, the latter often achieved using statistical transformation of CHAR [26]. This quantitative approach was combined with observations of how particle size influences transport [27], later confirmed by post-fire field studies [28], leading to the now-standard practice of separating charcoal into microscopic and macroscopic fractions to distinguish regional from local fire signals. In the 1990s, formalized statistical techniques were introduced to identify fire events (peaks compared to a background component) in charcoal time-series [29]. Subsequent work refined and verified peak-detection algorithms, enabling the identification of discrete fire events and the estimation of fire-return intervals from sedimentary records [25,30,31]. Significant advances allowing for the synthesis of multiple charcoal records across a variety of spatial scales have facilitated the development of regional and global fire syntheses, such as those resulting from the Global Charcoal Database [32,33].

Building on the success of reconstructing fire frequency, a growing body of experimental and paleoecological studies demonstrates that the size, shape, and physical features of charcoal particles are linked to the fuels burned and aspects of fire behavior. Umbanhowar and McGrath [34] showed that grass-derived charcoal tends to have higher length-to-width (aspect) ratios than wood-derived charcoal. This finding was supported and expanded with subsequent morphometric analyses which showed that, although charring temperature and post-fire transport can modify particle shapes, the type of fuel remains detectable in charcoal morphology [35]. Although the aspect ratio has become a particularly widely used proxy for grass versus woody fuel [36,37,38,39], the approach is not without caveats. For example, multiple studies have since shown that elongated charcoal can also be produced by sedges and thus charcoal morphology signals are context-dependent [40,41]. Anatomical identification of macro-charcoal has also been employed to distinguish between taxonomic groups of varying resolution. Morphotype classification schemes [42,43] aim to be flexible and applicable beyond the original study site, providing a template to identify charcoal types that can be adapted to other ecosystems, but recent studies highlight the need to experimentally characterize charcoal particles in new ecosystems [44].

The physical and morphological properties of charcoal have also been applied to consideration of the intensity or severity of fire. Umbanhowar and McGrath [34] demonstrated that a hot fire results in less charcoal, and the charcoal produced is generally smaller. Vaughan and Nichols [45] also found that higher temperatures produce charcoal which is strongly fractured, less dense, and with higher porosity in comparison to charcoal formed at lower temperatures. Braadbaart and Poole [46], Kaal et al. [47], and Wurster et al. [48] demonstrated that the carbon content of charcoal or the amount of pyrogenic carbon has some relationship to the temperature of formation. Turney et al. [49] described that a thermosequence of combusted wood samples became progressively depleted in 13C. In contrast, Moroeng [50] reports that 13C is enriched (12C depleted) compared with the parent wood. Bird and Ascough [51] reviewed the use of isotope fractionation accompanying pyrolysis and described considerable unexploited potential, at that time, which has led to the development of methods using hydrogen pyrolysis to quantify the production, fate, and stable isotope composition of pyrogenic carbon [40,52].

Charcoal records have also been used to infer the area burned by fire, adding a spatial aspect to the reconstruction of fire history. Modeling studies have demonstrated that long-term charcoal influx correlates with burned area [53], and empirical calibration studies have validated this relationship. For example, charcoal accumulation in lakes in the Alaskan boreal region has a significant correlation with area burned within a 20 km radius [54], Canadian boreal lake charcoal counts and charcoal particle area correlate with both the burned area and the satellite-derived fire severity of wildfires within 30 km [55], and in European lakes, macro-charcoal accumulation correlates with area burned across biomes [56]. It remains uncertain how well charcoal reflects the burned area in other environments (e.g., Australian eucalypt forests) where fuel structure and fire frequency and behavior differ, but the relationship also holds for African savannas, where fire proximity, area and intensity all correlate with the size and quantity of charcoal [57].

These varied sedimentary records have also been coupled with fire behavior and vegetation models using both forward and inverse approaches, demonstrating that integrating sedimentary charcoal records with fire behavior and vegetation models can improve our understanding of fire processes and their role within the climate–ecosystem–human system. Forward modeling has been used to simulate charcoal production, transport, and deposition from known or hypothetical fire scenarios, enabling quantitative comparisons with sedimentary charcoal records and constraining fire size, proximity, and intensity [53,58]. At regional and global scales, fire models have been benchmarked against charcoal-derived fire histories to evaluate model realism and identify missing processes, such as anthropogenic ignition or vegetation feedbacks [59,60]. Charcoal records have also been used to derive historical biomass burning emissions for climate simulations [61], and to validate aerosol–climate models simulating charcoal transport and deposition [62]. These applications demonstrate that sedimentary charcoal can constrain fire frequency, extent, energy, and severity of burning, providing a robust testbed for fire model development.

Inverse modeling approaches complement forward simulations by using charcoal records to reconstruct fire regime parameters and test competing hypotheses about fire drivers. Bayesian and statistical frameworks have been developed to infer fire-return intervals and ignition sources from charcoal accumulation patterns [63,64]. Charcoal-derived fire metrics have been used to constrain dynamic vegetation models and assess their ability to reproduce long-term fire–vegetation interactions [65]. These inverse approaches expand the interpretive power of charcoal records, allowing researchers to quantify fire characteristics and identify the climatic or anthropogenic processes responsible for observed fire regime shifts. Together, forward and inverse modeling demonstrate that sedimentary charcoal is a critical tool for evaluating and improving fire model performance across spatial and temporal scales.

3. Recent Advances in Intensity Reconstruction

The inter-connected components of a fire regime can influence charcoal accumulation and hence confuse the interpretation of any paleofire record. As an example, and potentially relevant to consideration of Indigenous use of fire, a fire regime consisting of regular, small fires in a complex mosaic of burnt and unburnt vegetation might mean that fire is ubiquitous but not necessarily visible in a charcoal record. Confusingly, frequent fire may also influence the vegetation (e.g., fuel loads and continuity and type) and perhaps lead to less intense fires and less charcoal produced. These observations strongly advocate for methods that allow for the separation of aspects of a fire regime. In this section, we discuss the definition of fire intensity and highlight recent advances in the reconstruction of the intensity of past fire events.

3.1. Defining Fire Intensity

The concept of fire intensity has been applied in wildfire science with multiple meanings and units. Fire intensity describes the energy released from the combustion of organic matter. It is often confused with the term fire severity, which describes the loss of above- and below-ground organic matter during a fire [10]. Fire intensity is difficult to measure, not least owing to the practicality of taking measurements during wildfires. Ideally, fire intensity quantification would include instantaneous measurements of energy output using flux meters; however, it is simpler and safer to deploy thermocouple-based devices that capture aspects of changes in energy as the time integrated trajectory of temperature throughout the period of energy release [66]. When using the thermocouple, it is the fire’s energy flux that causes the rise in temperature of the material; it is not a direct measurement of flame temperature. It is important to note that flame temperatures are not a proxy for fire intensity. As a good illustration, a single candle burns with a flame temperature around 1000 °C; however, although 10 candles produce the same measurable temperature, they will release 10 times the amount of energy. As a fire consumes plant material, the energy released also dries and heats unburned fuel ahead of the flaming front, and the fire moves forward (spreads) once the unburned fuel is dry and hot enough to ignite. This means that a thermocouple in one location will experience the peak of energy release as the main fire front passes it, followed by the gradual fall in temperature, and, finally, the energy flux from post-fire front smoldering. This means the energy regime of wildfires varies with respect to the rate of spread and the residence times of heating, resulting in differing total energy release.

In contemporary wildfire science, fire intensity is conceptualized, and thus quantified, in different ways to address different research or management needs. For example, if considering the impact of a wildfire on the ecosystem, the total energy delivered might be of the greatest importance; hence, the total energy released may be the preferred metric. However, for firefighters working at the fire front, the primary concern is the energy of the main flaming phase and the maximum intensity, to determine safety for operational firefighting and to decide which tactics should be used. This latter requirement has led to the wide adoption of one metric, fireline intensity, defined by Byram [67] as the rate of heat energy release per unit length of the active fire front. In practical terms, fireline intensity (with units of kW per meter of fire front) is the product of the fire’s rate of spread, the amount of fuel consumed per unit area, and the fuel’s heat of combustion. This metric is especially useful for understanding fire behavior in the field; for example, it correlates with flame length and is critical for fire management and suppression, since a higher fireline intensity indicates a more dangerous, harder-to-control fire [10,67].

Another measure of fire intensity is reaction intensity, introduced by Rothermel in his fire spread model [68], which is still frequently used with relatively minor modifications by others [69]. Reaction intensity describes the rate of energy release per unit area of the combustion zone (Btu ft−2 min−1 or kW/m2). Reaction intensity is useful for fire modeling and it provides a common basis to compare fires in experiments or theory [10,68]. In the newer field of remote sensing, additional fire intensity metrics have been developed. A prominent example is Fire Radiative Power (FRP), typically reported in units of watts (W), which estimates a fire’s instantaneous power output by measuring the radiant energy emitted in the mid-infrared. When FRP is integrated over the lifetime of a fire, it yields the total Fire Radiative Energy, representing the cumulative energy released. FRP is limited by the spatial resolution and sensitivity of satellite sensors, but it offers a safe and practical means of measuring fire intensity at large scales. By contrast, fireline intensity and reaction intensity are rarely measured directly in the field, as doing so is often impractical and dangerous [70].

Fire intensity, in a comprehensive sense, represents the energy released during all of the phases of a fire, including flaming and smoldering combustion, so a combination of metrics may be needed to fully describe fire intensity and to understand its impact on the environment. For example, a fast-moving grassfire might have a high fireline intensity but a short residence time at any given point, resulting in relatively modest soil heating, and a low heat flux into the ground. Conversely, a peat fire or a duff layer (plant litter) burn can smolder for hours at lower above-ground intensity (and thus safer for firefighters to approach), yet it delivers a high cumulative heat dose to the soil. Such a fire has a large total heat release per unit area even if its momentary intensity is not extreme. In general, longer-burning or fuel-rich fires that consume more biomass will impart a greater total energy to their environment, even if their peak rate of energy output at any moment is moderate.

Due to the variety of fire intensity metrics that serve different research or management purposes, it is often necessary, even in contemporary wildfire science, to specify which aspect of intensity one is referring to. Maintaining precise terminology is particularly important in paleofire and sedimentary charcoal research, where proxy measurements are used to infer past fire behavior. In these contexts, understanding which aspect of fire intensity a given proxy reflects, and communicating that accurately, is critical for interpreting fire regimes from the geological or sedimentary record and for comparing those proxies to modern fire measurements.

3.2. Reflectance in Visible Light/Optical Reflectance

The application of optical reflectance to charcoal emerged from coal petrology, where reflectance microscopy is used to assess the thermal maturity of fossil organic matter. Early studies showed that the percentage of light reflected (%Ro) from charred wood increases with the formation temperature of the charcoal [71,72]. This provided a pathway for paleofire researchers to explore fire intensity in sedimentary records. Scott and Jones [73] proposed that reflectance distributions could distinguish between low-intensity surface fires and high-intensity crown fires, and subsequent studies confirmed that reflectance provides information about the energy released during combustion [74]. Early interpretations focused on peak temperature or minimum charring temperature, but more recent experimental work has shown that reflectance develops throughout the fire, with maximum values reached during the transition from flaming to smoldering combustion [75,76]. This shift in understanding—towards reflectance as a proxy for total heat release—has improved the method’s relevance to natural fire scenarios.

Optical reflectance of charcoal is a photometric measurement of the fraction of incident light off the surface of an embedded and polished charcoal sample, under immersion oil. Immersion oil with a known refractive index (1.514) is used in combination with a specific light source (single wavelength 546 nm), and the instrument is calibrated against standards of known reflectance [21]. The optical reflectance is calculated from a series of reflectance measurements taken across the sample, in the order of 50–100, to calculate the mean random reflectance (Romean) [76,77].

Charcoal is composed of nanometer-scale, curved carbon domains—resembling fragments of graphene or fullerene structures—embedded within a highly disordered, aromatic-rich matrix [78]. Changes in the reflectance of charcoal are a result of the chemical and structural changes that organic materials undergo with exposure to heat. Particularly aliphatic compounds associated with lignocellulose are altered and the proportion of more stable, aromatic, and graphitic-like domains increases [79]. This graphitic-like component is more reflective, hence the reflectance of the charcoal as a whole increases [76].

Reflectance has potential for application to both modern post-fire assessment and paleoecological research using sedimentary charcoal. For example, a recent experimental burn demonstrated that reflectance of charcoal derived from bark is strongly correlated with the total heat delivered to tree boles, providing a quantitative post-fire measure of the energy flux by a passing fire to living trees [66,76]. This modern application suggests that field measurements of charcoal %Ro on tree bark can complement or improve upon traditional fire-severity assessments. Paleoecological studies have also applied this proxy to Pliocene-aged sediments from the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, where widespread wildfire was documented across boreal and forest–tundra ecosystems. In that study, reflectance values from Banks Island indicated high-intensity crowning fire, while those from Meighen Island and Ellesmere Island indicated low-intensity surface fire regimes, consistent with the modern fire ecology of the floral assemblages at those sites [5]. These findings suggest that reflectance can be used to reconstruct spatial gradients in fire intensity, and that it is a robust proxy for fire behavior under climate conditions analogous to those projected for the near future.

3.3. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

Similarly to optical reflectance, the application of FTIR analysis to charcoal began in coal petrology, and to some extent, built on the use of optical reflectance to determine the processes that lead to fusinite formation [80]. In coal geology, charcoal is recognized both macroscopically as fusain and microscopically as inertinite macerals, which include fusinite, semifusinite, and inertodetrinite. These macerals are now widely accepted as the products of paleo wildfires, with their presence in coal seams providing critical evidence for ancient fire events [81]. Laboratory experiments have shown that increasing the temperature and duration of pyrolysis (Charring Intensity; CI [82]) shifts the IR absorbance spectrum of charcoal in predictable ways: the broad O–H stretching band (~3400 cm−1), C=O stretching (~1700 cm−1), and aliphatic C–H stretching (~2900 cm−1) are prominent in low-temperature charcoals, reflecting the retention of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin-derived structures, but as charring intensity increases, these bands diminish or disappear, while aromatic C=C stretching (~1600 cm−1) and out-of-plane C–H bending (~870–750 cm−1) become more pronounced, indicating the progressive aromatization and condensation of the carbon structure [80,83,84]. These changes reflect the progressive loss of volatiles (e.g., dehydration and breakdown of cellulose and lignin) and the condensation of carbon into stable aromatic structures at higher charring intensity, such that low-intensity charcoal retains distinct aliphatic and carbonyl peaks, while high-intensity charcoal is dominated by aromatic bands [80,83]. Like optical reflectance, many studies used furnace-derived, laboratory-produced charcoal, and initially correlated the spectral changes to maximum temperature [85], but also to CI [83].

FTIR analysis of charcoal has been used to reconstruct fire intensity in archeological and paleofire contexts. For example, Austrian historic and prehistoric charcoals were examined to investigate how original fire intensity and burial environment influence long-term chemistry [84]. Charcoals produced either as residues from combustion in oxygen-available environments or through the intentional production of charcoal in an oxygen-limited environment for metal-working can be clearly distinguished, but the authors warned that particle size and preservation conditions influence the spectral signature. The method has also been applied to a long sedimentary record spanning the past two glacial/interglacial transitions to compare the impact of these transitional climates on fire with and without the influence of Aboriginal cultural practice [86]. They found lower fire intensities following the Pleistocene-Holocene transition than the MIS 6-5 transition, consistent with Australian Indigenous burning practices.

FTIR has benefits over optical reflectance in that it is rapid, inexpensive, and non-destructive, requiring only standard FTIR instrumentation. Hand-held FTIR could even be used in the field for high-resolution post-fire assessment. Although the initial acquisition of data is rapid, the processing of the data can be time-consuming. This contrasts with charcoal reflectance where the preparation of blocks takes time, but once the data are collected, they require no additional processing. Of benefit to paleoecological applications, it appears possible to apply FTIR to bulk sediment without needing to isolate charcoal. Although this will only identify relative increases due to the diluting or obscuring influence of uncharred organic matter and mineral signatures, it has the potential to identify fire events that might otherwise be missed [87].

3.4. Raman Spectroscopy

Following early investigation of FTIR for reconstructing fire intensity, Beyssac [88] proposed that a ratio of the first-order spectral bands (D/G) in Raman spectroscopy described graphitization of carbonaceous materials in metamorphosed sediments. This was applied to carbonization of wood and contemporary and past fire events by Damien Deldicque and Jean-Noel Rouzaud (and colleagues) at the Department of Geosciences CNRS, Paris, France (e.g., [89]).

Many of these pioneering Raman studies, like early studies with reflectance and FTIR, have focused on the temperature at which a material formed: Beyssac [88] described their application as a “geothermometer” but acknowledged that temperature and/or pressure was involved, and in the case of charcoal, Rouzard et al. [89], Deldicque [90], and Deldicque and Rouzaud [91] describe Raman parameters as a “palaeothermometer”, although, as per the previous methods, this is an over-simplification.

Despite this confusion in terminology, there have been several studies linking changes in Raman spectra and fire intensity. These measures of intensity are based on the position, intensity, and width of the two first-order spectral bands, D (disordered or amorphous at ca. 1380 cm−1) and G (graphitic at ca. 1595 cm−1) [90,92,93,94,95,96,97]. These Raman proxies for fire intensity include the width (cm−1) between the D- and G-band peaks, referred to as Raman band separation (RBS), the ratio of the maximum intensity of the peak in the D band and G band (ID/IG; sometimes referred to as the R1 parameter), or the ratio of the areas under the D and G bands (AD/AG). The ratio of the width of the D or G spectral band at half of the maximum intensity (full width at half maximum (FWHM) or WD/WG) has also been reported to be sensitive to the degree of aromaticity [90,95,96]. Unitless ratios such as ID/IG, AD/AG, WD/WG are likely to be particularly useful as they are independent of the intensity (which can be affected by the surface roughness of charcoal).

The experimental work to date (e.g., [90,97]) demonstrates that the primary change in the Raman spectra of charcoal with thermal maturity relates to changes in the D band (height, intensity, width), which reflects the extent of polyaromatic structures. Deldicque et al. ([90] p. 323) argued that the “D band increase is thus a characteristic of the carbonization processes and a paramount Raman signature of this thermal phenomenon”. A simultaneous narrowing and increased intensity of the G band is evident with thermal maturity, as the G band is indicative of structural order in sp2-bonded carbon crystallites.

Although these variations are frequently discussed as changing with thermal maturity, testing is rare, and attempted calibration experiments, as for optical reflectance and FTIR above, have often used relatively simple techniques to combust materials using oxygen-limited environments in ovens. There is a move towards use of calorimeters which are likely to better reflect real-world conditions (e.g., [98]).

There have been several applications of Raman spectroscopy to charcoal from sedimentary sequences to consider past fire intensity (e.g., [97,99]). Nonetheless, methodological issues beyond the lack of calibration experiments still require consideration. This includes methods for the baseline correction of raw Raman spectra, with “sophisticated” techniques (e.g., polynomial or cubic spline interpolation) sometimes resulting in aberrant results, and so consistency and reproducibility may be an issue compared to a simple linear fit (e.g., between 900–2000 cm−1). Second, the deconvolution process can have a significant influence on the position or shape of the D- and G-band features (and hence the aromaticity of charcoal as a proxy of fire intensity). Literature (e.g., [92,93]) defines the position and width of the two first-order spectral bands, and Gaussian functions have previously been demonstrated, using standards, to explain the main features of a Raman spectrum in the region of interest [100]. Nonetheless, deconvolution can result in artifacts in the data, whereas less strict constraints of the D and G bands and the resulting Gaussian functions may result in poorer curve fits. It is also clear that deconvolution assignments constrain the position of the primary bands (by definition), and this affects the Raman parameters of thermal maturity.

An inter-related group of authors [89,90,91] have previously discussed issues with deconvolution. They argued that the determination of fire intensity should not be dependent on the deconvolution process and so favored the ratio of the peak in the D and G bands, orthogonal to the baseline, as a Raman measure of thermal maturity, and they referred to this as height and the ratio as HD/HG. Unpublished work (by SM) comparing ID/IG (deconvoluted data) with non-deconvoluted HD/HG data reveals differences, with the former ratio often higher and with a greater range of values.

3.5. Geochemical Methods

3.5.1. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons

Solvent extraction of sediment or rock samples yields extractable organic matter that can be chemically simplified by fractionation into aliphatic hydrocarbons, aromatic hydrocarbons, and polar compounds [101,102]. These fractions can be analyzed by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) in order to obtain information about wildfire molecular markers, and other biomarkers that provide information on plant type, other organic matter inputs, burial history, etc.

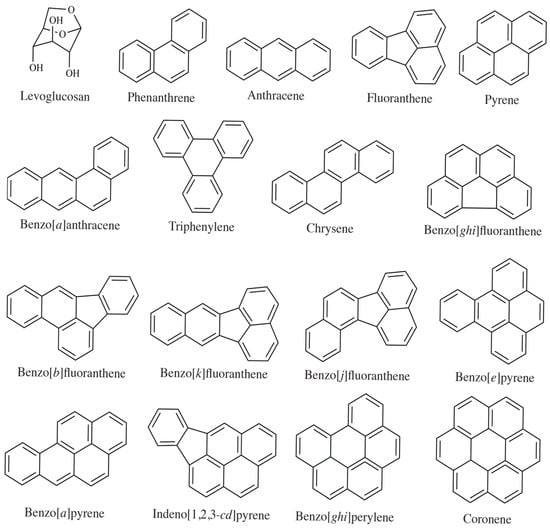

PAHs are a group of hydrocarbons (containing only hydrogen and carbon) made of two or more benzene rings (Figure 1) that in the geosphere are mainly derived from three origins: combustion (sometimes known as pyrolytic PAHs), higher plants, and diagenesis [103]. Combustion-derived PAHs are attributed to the products of wildfires and represent the incomplete combustion of biomass/solid fuel or plants. They have low aqueous solubility so can relatively easily accumulate in a soil environment or in a depositional environment that over geological time will become a sedimentary rock [104,105]. Combustion-derived PAHs are typically unsubstituted with three or more rings, and include (but are not limited to) phenanthrene, anthracene, fluoranthene, pyrene, benzo[a]anthracene, triphenylene, chrysene, benzo[b,j,k]fluoranthene (three isomers nearly co-eluting), benzo[a]pyrene, benzo[e]pyrene, indeno[1,2,3-cd]pyrene, benzo[ghi]perylene, and coronene (Figure 1). Note, however, that these PAHs can also be derived from other sources, including geological burial and diagenesis [106,107], outer space [108], and petrogenic/anthropogenic sources such as oil spills [109]. These 13 PAHs can be readily separated and quantified on a DB5MS 60 m column during GC–MS, although if a 30 m or shorter column is used, triphenylene and chrysene typically co-elute and are reported together [110].

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of levoglucosan and the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons mentioned in the text.

The proportion of different parent PAHs have long been used to source allocate environmental samples between petrogenic or anthropogenic inputs, and combustion-derived inputs such as wildfires [111,112,113]. For example, fluoranthene/(fluoranthene + pyrene) ratios > 0.5, indeno[1,2,3-cd]pyrene/(indeno[1,2,3-cd]pyrene + benzo[ghi]perylene) ratios > 0.5, benzo[b,j,k]fluoranthene/(benzo[b,j,k]fluoranthene + benzo[e]pyrene) ratios > 0.7, and anthracene/(anthracene + phenanthrene) ratios > 0.1 are typical of biomass or solid fuel combustion in environmental samples [113]. Care has to be taken in applying these ratio cut-offs to geological samples in order to assess paleo wildfires, because combustion-derived PAHs in ancient rocks will not necessarily follow the same systematics, due to the influence of diagenetic and burial-related processes over geological time [103,114,115,116,117]. For example, benzo[b,j,k]fluoranthene, benzo[e]pyrene, and coronene are relatively less susceptible to sedimentary alkylation processes [118], whereas benzo[a]anthracene and benzo[a]pyrene are more easily degraded [112,119]. Fluoranthene is less thermally stable than pyrene [120], so the fluoranthene/(fluoranthene + pyrene) ratio might be expected to be lower under high wildfire combustion temperatures, contrary to Yunker et al. [112,113].

Many paleo wildfire studies interpret changes in PAH size distribution as changes in fire intensity, mainly based on the observation that aromaticity in bulk burn products increases with temperature [107,121,122], and also based on a pyrolysis and thermodynamic study [123]. High-temperature wildfires produce more high-molecular-weight (HMW; 6- and 7-ring) PAHs [107,124,125], whereas lower-temperature wildfires or the weathering and burning of sedimentary hydrocarbons such as coal or oil produce more low-molecular-weight (LMW; 3- and 4-ring) PAHs [126,127]. Thus, in addition to using the total amount of PAHs or individual PAHs as a marker of wildfires, expressed quantitatively as ng/g rock or sediment, or as ng/g total organic carbon, the proportion of HMW/LMW PAHs can be used as a proxy for combustion temperature [128]. PAHs are produced over a broad temperature range (200–900 °C or more) so may be useful for recording high-temperature events [107,129]. This approach has been widely used for examining whether disturbance to the Earth system at mass extinction events and oceanic anoxic events was caused by wildfires [126,128,130,131,132,133,134,135].

Many Cretaceous-Paleogene mass extinction sites have high amounts of coronene, benzo[e]pyrene, benzo[ghi]perylene, consistent with extensive wildfires after the impact [136]. However, the Cretaceous-Paleogene mass extinction in non-marine boundary sites from North America is characterized by low amounts of HMW PAHs, consistent with combustion of hydrocarbons and not living plant biomass after the impact event [126]. More proximal locations to the impact have a high (>0.7) coronene index [coronene/(coronene + benzo[e]pyrene + benzo[ghi]perylene)], which was attributed to combustion of hydrocarbons that resulted in extensive soot in the atmosphere, rather than wildfires [130]. The Triassic-Jurassic mass extinction event is characterized by elevated HMW PAHs, which were attributed to igneous activity rather than wildfires, due to the humid climate conditions during the latest Rhaetian [132]. The ratio of coronene/benzo[a]pyrene (7-ring/5-ring) reached nearly 3.5 compared to a background of 1 at the boundary. This coronene/benzo[a]pyrene ratio and the coronene index have been used in more recent studies on the Triassic-Jurassic mass extinction event as recorded in the United Kingdom that have also concluded that biomass burning is not a major source of the PAHs, but instead they are due to a soil erosion event and distant smoke signals of wildfires [133,134]. The background coronene index of ~0.1 is typical of wildfire events with combustion temperatures of 700–1000 °C, whereas higher values (>0.3) are associated with higher temperatures > 1200 °C, and are associated with large-scale volcanic activity or impacts at mass extinctions [131]. At the Permian–Triassic mass extinction event, differing interpretations of the relative amount of coronene (coronene index; coronene/phenanthrene; 7-ring/5-ring (PAH7/5) in the Meishan section in southwestern China have been used either to suggest high-temperature combustion of sedimentary hydrocarbons during initial sill emplacement of the Siberian Traps Large Igneous Provence (LIP [131]), or devastation of the terrestrial ecosystem by wildfires, leading to enhanced nutrient supply to the oceans from soil [135]. Note the proliferation of parameters related to coronene, and the uncertainty of some of the definitions (for example, PAH7/5 is referenced to [132] (coronene/benzo[a]pyrene) by [135], but it is not clear if this is the form used, or whether all 5-ring PAHs (two benzopyrenes and three benzofluoranthenes) are included.

The 6/3-ring PAH ratio increased by orders of magnitude during Oceanic Anoxic Event 2 (OAE2) in the western United States of America, which was suggested to be due to increased wildfire frequency [128]. However, only fluoranthene, pyrene, benzo[ghi]perylene, and coronene increased during OAE2, whereas other PAHs (including the 6-ring indeno[1,2,3-cd]pyrene) did not, which together with the lack of a precise definition of the 6/3-ring PAH ratio complicates the interpretation [128].

Recently, various PAH ratios were compared with fire temperatures calculated from fusinite reflectance for late Triassic and early Jurassic rocks from Poland [116]. The most effective ratio is that of benzo[ghi]fluoranthene/(benzo[ghi]fluoranthene + benzo[a]anthracene), which has an R2 of 0.62 with fusinite reflectance, although triphenylene/(triphenylene + chrysene) also correlates with temperature. These parameters work because of the more condensed structures of benzo[ghi]fluoranthene and triphenylene (Figure 1). Wildfire temperature can be calculated as follows [116]:

where X = benzo[ghi]fluoranthene/(benzo[ghi]fluoranthene + benzo[a]anthracene).

T(°C) = 664 × X + 117,

Apart from burn temperature, PAH distribution patterns may be strongly linked to plant sources and the burn phase (solid residue or smoke-burn phase), because LMW PAHs are more likely to enter the vapor phase, whilst HMW PAHs will sorb primarily to organic residues in the solid phase [122]. Spatial calibration of the distribution of PAHs as proxies of area burned by vegetation fires in California suggests that LMW PAHs are reliable local proxies of area burned (within 40 km), and that larger PAHs such as phenanthrene, chrysene, and benzo[g,h,i]perylene can work on more regional scales (to 75 km), whereas benzo[b]fluoranthene and benzo[k]fluoranthene can work up to 150 km [137].

3.5.2. Levoglucosan

The monosaccharide anhydride levoglucosan (1,6-anhydro-β-D-glucopyranose; Figure 1) and the isomeric and co-analyzed mannosan and galactosan have been used to determine the intensity and heat of paleo wildfires in environmental sediments [105,138,139,140,141]. The role of levoglucosan as a proxy for vegetation fires has recently been reviewed [142,143], so is only briefly summarized here. Levoglucosan is only produced by cellulose pyrolysis, and can be transported both terrestrially and atmospherically [140]. Levoglucosan is typically produced at temperatures between 200–300 °C, during lower intensity or smoldering fires [144]. Higher combustion temperatures (300 °C) and longer combustion durations result in higher levoglucosan/mannosan and levoglucosan/(mannosan + galactosan) ratios, regardless of plant species [144]. Some studies have analyzed both levoglucosan and PAH, in order to compare different combustion temperature regimes [144]. The atmospheric transport of levoglucosan means that it can be used as a proxy for biomass burning in distal sites, such as in Greenland snow [145] and Siberian lakes [146]. Levoglucosan and its isomers are polar compounds that occur in the polar fraction, and an aliquot of these fractions has to be derivatized with N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (BSTFA) or similar, prior to GC–MS analysis. Because levoglucosan and its isomers contain ether-linkages and -OH groups, it is thermally unstable, and breaks down during long-term burial, so is not present in rocks older than 0.5 million years [143,146].

4. Where Do We Go from Here?

While multiple methods for reconstructing aspects of fire intensity from charcoal are already being applied to reconstruct fire histories and archeological activities, the methods for charcoal production in modern calibration studies and the kinds of vegetation used for calibrations are variable, and the sensitive range of the methods has not been systematically established. Only some methods have been validated against real-world wildfires, and the terminology—what is actually being reconstructed—would benefit from greater clarity. In addition, it is essential that those working on proxies familiarize themselves with an understanding of combustion and the appropriate understanding of heat transfer in wildfires, if we are to begin to measure the correct mechanisms of formation with which to test potential proxies.

4.1. Charcoal Production

Charcoals used for the calibration and testing of fire intensity (energy per unit time) proxies have been generated in labororatories primarily using muffle furnaces (e.g., [47,80]), but also tube furnaces [96], cone calorimeters [75,76,147], and other flaming-fire-replicating setups [98,148]. Wildfires involve three stages: pyrolysis, flaming combustion, and smoldering combustion. Of these, furnace charcoals only replicate pyrolysis, and tend to involve holding the material at maximum temperature for an extended period (hours), unlike in a wildfire setting that delivers an energy flux (energy per unit time) [76]. Experiments on charcoal reflectance have demonstrated that maximum reflectance is not reached only in response to the external heat flux, or even at the peak heat release rate during flaming combustion, but continues to respond to total heat release i.e., the energy being produced by the burning item [76]. For these reasons, multiple articles have advocated for charcoal production methods that more closely simulate the stages of wildfire [75,76,148,149,150,151], which will apply to all methods used to interrogate the information held within charcoals, including reflectance, FTIR, and Raman-based methods. Interestingly, the reflectance of charcoals from wildfires has been found to be highly variable [152], which highlights that charcoal reflectance is not the result of consistent temperatures as might be generated in an oven, but rather link to variations in combustion of different vegetation elements in response to varied energy fluxes in time and space throughout the duration of the fire.

4.2. Vegetation Characteristics

The application of optical reflectance to charcoal as a fire intensity proxy is strongly influenced by vegetation characteristics. Wood density, bark thickness, and moisture content all affect the reflectance values obtained from charred samples. Denser woods tend to produce charcoal with higher reflectance (i.e., greater fuel mass per volume and longer potential duration of burning), and moisture content can lower reflectance (likely by lowering the time the tissues are exposed to increasing heat), requiring calibration for both species and fuel conditions [66,75]. While a positive linear relationship has been established between wood density and reflectance (r = 0.53), and wood density is highly correlated with total heat release per unit volume (r = 0.94), calibration datasets remain limited in species diversity and ecological context [147]. The impact of non-woody fuels, such as grasses and herbs, on reflectance proxies has not been systematically tested, and further work is needed to develop universal calibration curves that account for the full range of vegetation types encountered in natural fires. Owing to the use of reflected light microscopy in the measurement of optical reflectance, it does provide the operator the ability to make observations of what the plant material is, i.e., leaf, wood, etc., and what the nature of the wood is. For example, the charcoals can be assessed as to whether they were degraded prior to charring and therefore might represent litter that was burned in a fire [149], and they can be identified to wood type and density by observing the cellular anatomy allowing, with further developments in this area, potential correction for different species [147].

FTIR-based fire intensity proxies may be sensitive to the chemical composition of the fuel, which varies between species and plant functional types. Fuel-specific calibrations or corrections are recommended to account for differences in cellulose, lignin, and other organic compounds [153]. Guo and Bustin [80] found that gymnosperms and angiosperms can be distinguished by their FTIR spectral characteristics, and Constantine et al. [83] argued that charring intensity could be predicted independently of wood type in charcoals produced in ovens, which is to be expected based on the formation of charcoal in oven circumstances but will differ for charcoals formed by wildfires. Smidt et al. [84] reported that tree taxa such as Abies, Acer, Fagus, and Picea are not distinguishable by FTIR, indicating that species-level differences may be subtle or masked by other factors. The effects of fuel mixtures, bark content, and live versus dead material on FTIR proxies remain largely untested, and further research is needed to expand calibration datasets and validate these proxies in complex wildfire scenarios.

Raman-based proxies for fire intensity rely on the structural changes in carbon matrices during combustion, which are influenced by the chemical composition and physical structure of the original vegetation. While most calibration studies have focused on wood, the impact of fuel type, species, and tissue anatomy on Raman parameters such as D/G band ratios and FWHM are not fully understood [95,97]. The role of non-woody fuels, mixed species, and varying moisture content in shaping Raman spectra has not been systematically investigated. As a result, the applicability of Raman proxies across diverse vegetation types remains an open question, and further experimental work is needed to establish calibration standards that reflect the heterogeneity of natural fuels. As with reflectance and FTIR, Raman-based methods also need to be tested on charcoal generated by wildfire-appropriate mechanisms.

The production and distribution of PAHs during combustion are affected by both the type of vegetation and the combustion conditions. Distinct PAH profiles can result from burning different plant types, with high-molecular-weight PAHs favored in high-temperature fires and low-molecular-weight PAHs in smoldering or lower intensity burns [107,122]. However, most studies have focused on woody fuels, and the influence of grasses, herbs, and mixed fuel loads on PAH ratios is not well characterized. The impact of plant chemistry, such as resin or oil content, on PAH formation has also received limited attention, although it is well known that certain types of coniferous resins produce characteristic alkylated PAHs such as retene (1-methyl-7-isopropyl phenanthrene) and 1,7-dimethylphenanthrene [154]. Further research is needed to test PAH proxies across a broader range of vegetation types and to account for post-fire environmental processes that may alter PAH distributions before deposition.

Levoglucosan is produced exclusively by the pyrolysis of cellulose, making its abundance and preservation highly dependent on the proportion of cellulose-rich material in the fuel [140,143]. The yield of levoglucosan varies with plant species, tissue type, and combustion temperature, with higher amounts observed in low-intensity or smoldering fires at <350 °C [144]. The ability of chemical signatures to capture the occurrence of low-intensity and smoldering fires is of clear importance as these fires tend to go unrecognized in the paleo record. However, the impact of fuel mixtures, plant age, and moisture content on levoglucosan production has not been systematically tested. Expanded calibration studies and field validation across diverse vegetation types are needed to improve the reliability of levoglucosan as a fire intensity proxy.

While significant progress has been made in understanding how vegetation characteristics affect fire intensity proxies, substantial gaps remain. Most calibration studies have focused on a limited range of species and fuel types, and the complexity of natural wildfires—including mixed fuels, variable moisture, and post-fire alteration—has yet to be fully addressed. Future research should prioritize expanding reference datasets where charcoal and products are made in wildfire-similar conditions, testing proxies across diverse vegetation types, and developing multi-proxy approaches to improve robustness and ecological relevance.

4.3. Sensitivity Testing

Although the methods described are nominally reflecting the same process, each method is measuring different expressions of the suite of changes that occur in charcoal with increasing fire intensity. As a result, it is likely that each method will perform more strongly within a different range on the fire intensity–energy spectrum, and, therefore, at different stages along the combustion continuum. Where quantitative calibration has been developed, it has predominantly been charcoal–temperature relationships generated in furnaces, which are not realistic simulations of wildfire (see Section 4.1), nor does temperature alone capture fire intensity (see Section 3.1). Future studies ought to systematically test the sensitivity of these proxy methods to meaningful fire intensity ranges reflective of wildfire across different ecosystems. However, as a possible guide to the sensitivity within different methods, we compare each method’s range for charcoals generated at different temperature ranges (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sensitivity of analysis methods to the apparent range of temperatures linked to charcoal formation that should be further explored for fire intensity reconconstruction (noting temperature is only one expression of aspects of fire intensity).

The onset of pyrolysis in wood occurs when the material reaches between 200–300 °C, following heat-generated dehydration of the material. The user of the reflectance microscope can observe thermally altered wood (appearing as dark brown instead of light yellow) but typically there is no measurable reflectance until the sample has been heated to around 300 °C. Below 300 °C, charcoal is often insufficiently carbonized to develop the microstructural changes that the reflectance method detects [155,156]. For oven-based charcoal, reflectance then progressively increases, with a linear or log linear relationship up to 600–700 °C [80,155]. Above 800 °C, the rate of increase observed in oven-based chars slows and plateaus as the charcoal is already highly ordered and graphitic [76,79,156]. This rate and point of plateau is likely to be different for wildfire-generated charcoal owing to the duration of heating rather than temperature. For example, charcoals with lower reflectance than the high-reflectance charcoals made in ovens were produced in wildfire energy regimes linked to temperature measurements of 1000 °C+ [66] (typically the upper limit measurable by thermocouples).

FTIR has been shown to distinguish a range from low-temperature charcoals (200–400 °C) [157] and is not sensitive to changes over 700 °C [83,157]. FTIR is sensitive to the presence of functional groups such as hydroxyl (O–H), carbonyl (C=O), and aliphatic C–H bonds. These groups are progressively lost as charring increases, and once these are lost the FTIR method cannot record further changes. FTIR is therefore particularly effective at identifying low- to moderate-temperature charcoals by detecting residual labile compounds [95].

In contrast, Raman spectroscopy provides structural information about the carbon matrix itself (the same structural changes that reflectance is responding to). It detects the degree of aromatic condensation and graphitization through the D and G bands, which become more pronounced and ordered with higher charring temperatures. Although Theurer et al. [96] found the traditional Raman-based fire intensity metrics such as D/G height ratio and area are unreliable with temperatures greater than 600–700 °C, other metrics, such as band width and peak separation, may remain reliable up to 1000 °C. This potentially suggests that Raman is better for identifying charcoals formed at the upper ranges of measured temperatures and for assessing the degree of carbon ordering [95].

PAHs are produced across a wide temperature range (200–900 °C or more), making them sensitive to both low and high fire intensities [107,116]. Some have suggested that PAHs are produced over a broader temperature range than charcoal, such that they may be particularly useful for recording high temperatures of formation [107,128] that must be driven by prolonged heating or very intense energy fluxes. Charcoal is produced in wildfires where the flaming front can reach 800–1200 °C, and indeed Belcher et al. [66] measured reflectance from charcoals from trees that showed peak temperatures (measured by thermocouples) of up to 1008 °C during an experimental wildfire. Despite recent advances in PAH ratio calibrations to fusinite reflectance and therefore wildfire temperature [115], there is clearly scope for more precise calibrations directly to temperature.

Levoglucosan, in contrast, is only produced by cellulose pyrolysis at relatively low temperatures (typically 200–300 °C), making it most sensitive to low-intensity or smoldering fires [140,143]. Higher combustion temperatures and longer durations increase the levoglucosan/mannosan and levoglucosan/(mannosan + galactosan) ratios, but levoglucosan itself is rapidly degraded at higher temperatures and during long-term burial, limiting its preservation to recent sediments and low-intensity fire events [141,143].

4.4. Wildfire Validation

Across all methods, the natural heterogeneity of wildfire charcoals [66,157]—including differences in fuel type, charring depth, and post-fire weathering—can complicate interpretation and reduce reproducibility when tested in field settings, as opposed to the controlled environment of laboratory-produced charcoal. For optical reflectance, studies by Belcher and colleagues [66,75,147] have shown strong correlations between bark and wood charcoal %Ro and measured energy flux in instrumented burns. In addition, rather than consider only temperature mean or maximum, such research has shown that the integrated area under a temperature response (thermocouple) curve [66] is a better measure where energy fluxes or intensity cannot be measured. Variability in fuel type, bark thickness, and micro-environmental conditions can lead to significant scatter in reflectance values, even within a single fire event [157]. This makes it challenging to establish universal calibration curves for %Ro across different ecosystems or fire regimes [66], highlighting the need for further studies in diverse settings and where measurements of energy flux or integrated area under temperature curves are measured. FTIR validation in the field has similarly demonstrated that although spectral changes in functional groups track fire intensity, and can distinguish low-, medium-, and high-intensity fire, the presence of uncharred organic matter, soil minerals, or post-fire weathering can obscure the charcoal signal, making it difficult to isolate the fire intensity effect in complex, real-world samples [80,85,87,157].

As well as careful sample selection and pretreatment, multi-proxy evaluation of fire intensity is recommended to improve robustness against environmental alteration, fuel variability, and post-fire changes [80,154,157]. Studies on charcoal collected from wildfires or prescribed burns has validated D- and G-band evolution measured by Raman spectroscopy as reflecting differences in fire intensity [95,97]. These studies also demonstrated that uncertainties remain regarding the influence of surface roughness, sample orientation, and the heterogeneity of natural charcoals, which can affect spectral reproducibility and the robustness of field calibrations. Similarly to FTIR, careful sample preparation is needed, and multi-proxy application is recommended to overcome the uncertainties introduced in complex, real-world fire scenarios [96,97].

For geochemical proxies such as PAHs, field validation has confirmed that higher fire intensities yield greater proportions of high-molecular-weight PAHs, but environmental factors such as post-fire leaching, microbial degradation, and atmospheric transport can alter PAH distributions before sampling, complicating the direct interpretation of fire intensity [107,116]. Furthermore, PAHs can be derived from igneous activity, diagenetic processes, and anthropogenic sources [158], so further work is needed to de-convolute PAHs produced from wildfires and from these other processes. One possible solution is the use of compound-specific δ13C measurements of PAHs, which may enable source discrimination. Levoglucosan, validated as a marker for low-intensity burning in controlled burns, is particularly vulnerable to post-fire degradation [138,144]. These uncertainties highlight the potential need for ecosystem-specific calibration, careful sample selection and preparation, and value in multi-proxy approaches when applying fire intensity proxies to real-world wildfire records. Nonetheless, field validation has substantially improved confidence in these proxies by confirming their real-world capacity to identify fire intensities at different levels in a natural setting.

4.5. Terminology

Accurate use of terminology, consideration of what is measured, and how it maps onto or differs from the way those terms are used in modern fire science, is critical for the application of what we can learn from sedimentary charcoal to contemporary fire management and research. To derive more value from fossil and sedimentary records, we must understand wildfire combustion dynamics and test proxies on the products of fires formed in a manner that best captures the fire environment; we must understand contemporary wildfire terminology and those processes and terms used to describe combustion dynamics and apply it according to best practice in the modern literature. In doing so, we not only improve our understanding of modern wildfire dynamics and impacts but also provide the tools to interpret the baseline of natural wildfire variability though the ancient past that provides the context for our future wildfire challenges.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.F. and S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, T.F., S.M., S.C.G. and C.B.; writing—review and editing, T.F., S.M., S.C.G. and C.B.; project administration, T.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

T.F. was funded by a Ramsay Fellowship, through Adelaide University. S.M. was funded by the Australian Research Council Discovery Grant DP20101123 (CIs Dosseto, Mooney and Bradstock). S.C.G. was funded by the Australian & New Zealand International Scientific Drilling Consortium (ANZIC) (grant number PC_SGeorge_0121, AILAF2316, PCAFX4010124_SGeorge), and the Chinese Academy of Sciences President’s International Fellowship Initiative (grant 2024PVA0106). C.B. was funded by NERC, IDEAL UK Fire NE/X005143/1.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank David Bowman and Joan Esterle for early discussions. S.M. acknowledges discussion with Chris Marjo. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used M365 Copilot with GPT-4 architecture, including version number: bizchat.20251208.59.2, for the purposes of literature interrogation and integration of author contributions. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LMW | Low Molecular Weight |

| HMW | High Molecular Weight |

| GC-MS | Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry |

| LIP | Large Igneous Provence |

| OAE2 | Oceanic Anoxic Event 2 |

| FWHM | Full Width at Half Maximum |

| CI | Charring Intensity |

| CHAR | Charcoal Accumulation Rate |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform Infrared |

| PAH | Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon |

References

- Xu, R.; Ye, T.; Huang, W.; Yue, X.; Morawska, L.; Abramson, M.J.; Chen, G.; Yu, P.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Z.; et al. Global, regional, and national mortality burden attributable to air pollution from landscape fires: A health impact assessment study. Lancet 2024, 404, 2447–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolden, C.A.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Jones, M.W.; Jain, P. Wildfires in 2024. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 237–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frelich, L.E. Wildland Fire: Understanding and Maintaining an Ecological Baseline. Curr. For. Rep. 2017, 3, 188–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlon, J.R. What the past can say about the present and future of fire. Quat. Res. 2020, 96, 66–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, T.; Eble, C.; Sinninghe Damsté, J.S.; Brown, K.J.; Rybczynski, N.; Gosse, J.; Liu, Z.; Ballantyne, A. Widespread wildfire across the Pliocene Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2021, 584, 110653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, S.P.; Prentice, I.C.; Bloomfield, K.J.; Dong, N.; Forkel, M.; Forrest, M.; Ningthoujam, R.K.; Pellegrini, A.; Shen, Y.; Baudena, M.; et al. Understanding and modelling wildfire regimes: An ecological perspective. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 125008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlon, J.R. The Geography of Fire: A Paleo Perspective. In Department of Geography; University of Oregon Libraries: Eugene, OR, USA, 2009; p. xvii, 205. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, D.M.J.S.; Balch, J.; Artaxo, P.; Bond, W.J.; Cochrane, M.A.; D’Antonio, C.M.; DeFries, R. The Human Dimension of Fire Regimes on Earth. J. Biogeogr. 2011, 38, 2223–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, O.; Kasoar, M.; Voulgarakis, A.; Edwards, T.; Haas, O.; Millington, J.D.A. The Spatial Distribution and Temporal Drivers of Changing Global Fire Regimes: A Coupled Socio-Ecological Modeling Approach. Earth’s Future 2025, 13, e2024EF004770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeley, J.E. Fire intensity, fire severity and burn severity: A brief review and suggested usage. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2009, 18, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugihara, N.G.; Van Wagtendonk, J.W.; Fites-Kaufman, J.A. Fire as an Ecological Process. In Fire in California’s Ecosystems, 2nd ed.; Sugihara, N.G., Van Wagtendonk, J.W., Fites-Kaufman, J.A., Stephens, S.L., Thode, A.E., Shaffer, K.E., Eds.; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2018; pp. 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Krebs, P.; Pezzatti, G.B.; Mazzoleni, S.; Talbot, L.M.; Conedera, M. Fire regime: History and definition of a key concept in disturbance ecology. Theory Biosci. 2010, 129, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, D.M.J.S.; Sharples, J.J. Taming the flame, from local to global extreme wildfires. Science 2023, 381, 616–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, M.; Vahedifard, F.; Tracy, F.T. Post-Wildfire Stability of Unsaturated Hillslopes Against Rainfall-Triggered Landslides. Earth’s Future 2023, 11, e2022EF003213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, D.A.; Macdonald, K.J.; Gibson, R.K.; Doherty, T.S.; Nimmo, D.G.; Nolan, R.H.; Ritchie, E.G.; Williamson, G.J.; Heard, G.W.; Tasker, E.M.; et al. Biodiversity impacts of the 2019–2020 Australian megafires. Nature 2024, 635, 898–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Breton, T.D.; Lyons, M.B.; Nolan, R.H.; Penman, T.; Williamson, G.J.; Ooi, M.K. Megafire-induced interval squeeze threatens vegetation at landscape scales. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2022, 20, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Eisenhauer, N.; Du, Z.; Lucas-Borja, M.E.; Zhai, K.; Berdugo, M.; Duan, H.; Wu, H.; Liu, S.; Revillini, D.; et al. Fire-driven disruptions of global soil biochemical relationships. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, F.H.; Williamson, G.; Borchers-Arriagada, N.; Henderson, S.B.; Bowman, D.M.J.S. Climate Change, Landscape Fires, and Human Health: A Global Perspective. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2024, 45, 295–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naser, M.Z.; Kodur, V. Vulnerability of structures and infrastructure to wildfires: A perspective into assessment and mitigation strategies. Nat. Hazards 2025, 121, 9995–10015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeshita, L.; Sloat, L.L.; Fischer, E.V.; Kampf, S.; Magzamen, S.; Schultz, C.; Wilkins, M.J.; Kinnebrew, E.; Mueller, N.D. Pathways framework identifies wildfire impacts on agriculture. Nat. Food 2023, 4, 664–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.C. Charcoal recognition, taphonomy and uses in palaeoenvironmental analysis. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2010, 291, 11–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iversen, J. Land Occupation in Denmark’s Stone Age; Sandal, A., Ed.; C. A. Reitzel: Kobenhavn, Denmark, 1941. [Google Scholar]

- Tolonen, K. Charred particle analysis. In Handbook of Holocene Palaeoecology and Palaeolimonology; Berglund, B.E., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chinchester, UK, 1986; Volume 1, pp. 485–496. [Google Scholar]

- Swain, A.M. A history of fire and vegetation in northeastern Minnesota as recorded in lake sediments. Quat. Res. 1973, 3, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, C.J.; Whitlock, C.; Bartlein, P.J.; Millspaugh, S.H. A 9000-year fire history from the Oregon Coast Range, based on a high-resolution charcoal study. Canadian J. For. Res. 1998, 28, 774–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, M.J.; Marlon, J.R.; Bartlein, P.J.; Harrison, S.P. Fire history and the Global Charcoal Database: A new tool for hypothesis testing and data exploration. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2010, 291, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.S. Particle motion and the theory of charcoal analysis: Source area, transport, deposition, and sampling. Quat. Res. 1988, 30, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitlock, C.; Millspaugh, S.H. Testing the assumptions of fire-history studies: An examination of modern charcoal accumulation in Yellowstone National Park, USA. Holocene 1996, 6, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.S.; Royall, P.D. Local and Regional Sediment Charcoal Evidence for Fire Regimes in Presettlement North-Eastern North America. J. Ecol. 1996, 84, 365–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinner, W.; Conedera, M.; Ammann, B.; Gaggeler, H.W.; Gedye, S.; Jones, R.; Sagesser, B. Pollen and charcoal in lake sediments compared with historically documented forest fires in southern Switzerland since AD 1920. Holocene 1998, 8, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higuera, P.E.; Gavin, D.G.; Bartlein, P.J.; Hallett, D.J. Peak detection in sediment–charcoal records: Impacts of alternative data analysis methods on fire-history interpretations. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2011, 19, 996–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlon, J.R.; Bartlein, P.J.; Daniau, A.-L.; Harrison, S.P.; Maezumi, S.Y.; Power, M.J.; Tinner, W.; Vanniére, B. Global biomass burning: A synthesis and review of Holocene paleofire records and their controls. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2013, 65, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, M.J.; Marlon, J.; Ortiz, N.; Bartlein, P.J.; Harrison, S.P.; Mayle, F.E.; Ballouche, A.; Bradshaw, R.H.W.; Carcaillet, C.; Cordova, C.; et al. Changes in fire regimes since the Last Glacial Maximum: An assessment based on a global synthesis and analysis of charcoal data. Clim. Dyn. 2008, 30, 887–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umbanhowar, C.E., Jr.; Mcgrath, M.J. Experimental production and analysis of microscopic charcoal from wood, leaves and grasses. Holocene 1998, 8, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, A.J.; Belcher, C.M. Charcoal morphometry for paleoecological analysis: The effects of fuel type and transportation on morphological parameters. Appl. Plant Sci. 2014, 2, 1400004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leys, B.A.; Commerford, J.L.; McLauchlan, K.K. Reconstructing grassland fire history using sedimentary charcoal: Considering count, size and shape. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aleman, J.C.; Blarquez, O.; Bentaleb, I.; Bonté, P.; Brossier, B.; Carcaillet, C.; Gond, V.; Gourlet-Fleury, S.; Kpolita, A.; Lefèvre, I.; et al. Tracking land-cover changes with sedimentary charcoal in the Afrotropics. Holocene 2013, 23, 1853–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereboom, E.M.; Vachula, R.S.; Huang, Y.; Russell, J. The morphology of experimentally produced charcoal distinguishes fuel types in the Arctic tundra. Holocene 2020, 30, 1091–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vachula, R.S.; Sae-Lim, J.; Li, R. A critical appraisal of charcoal morphometry as a paleofire fuel type proxy. Quaternary Science Reviews 2021, 262, 106979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehn, E.; Rowe, C.; Ulm, S.; Woodward, C.; Bird, M. A late-Holocene multiproxy fire record from a tropical savanna, eastern Arnhem Land, Northern Territory, Australia. Holocene 2021, 31, 870–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, K.; Lynch, E.; Calcote, R.; Hotchkiss, S. Interpretation of charcoal morphotypes in sediments from Ferry Lake, Wisconsin, USA: Do different plant fuel sources produce distinctive charcoal morphotypes? Holocene 2007, 17, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enache, M.D.; Cumming, B.F. Tracking recorded fires using charcoal morphology from the sedimentary sequence of Prosser Lake, British Columbia (Canada). Quat. Res. 2006, 65, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustaphi, C.J.C.; Pisaric, M.F.J. A classification for macroscopic charcoal morphologies found in Holocene lacustrine sediments. Prog. Phys. Geogr. Earth Environ. 2014, 38, 734–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feurdean, A.; Vachula, R.S.; Hanganu, D.; Stobbe, A.; Gumnior, M. Charcoal morphologies and morphometrics of a Eurasian grass-dominated system for robust interpretation of past fuel and fire type. Biogeosciences 2023, 20, 5069–5085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, A.; Nichols, G. Controls on the deposition of charcoal; implications for sedimentary accumulations of fusain. J. Sediment. Res. 1995, 65, 129–135. [Google Scholar]

- Braadbaart, F.; Poole, I. Morphological, chemical and physical changes during charcoalification of wood and its relevance to archaeological contexts. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2008, 35, 2434–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaal, J.; Martínez Cortizas, A.; Reyes, O.; Soliño, M. Molecular characterization of Ulex europaeus biochar obtained from laboratory heat treatment experiments–A pyrolysis–GC/MS study. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2012, 95, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurster, C.M.; Saiz, G.; Schneider, M.P.W.; Schmidt, M.W.I.; Bird, M.I. Quantifying pyrogenic carbon from thermosequences of wood and grass using hydrogen pyrolysis. Org. Geochem. 2013, 62, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turney, C.S.M.; Wheeler, D.; Chivas, A.R. Carbon isotope fractionation in wood during carbonization. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2006, 70, 960–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroeng, O.M.; Moore, T.A.; Shen, J.; Esterle, J.S.; Liu, J. Isotopic and petrographic implications for fire type, temperature and formation of degradosemifusinite in fusain layers from an Early Cretaceous coal bed, Hailar Basin, Inner Mongolia, China. Fuel 2025, 384, 133895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, M.I.; Ascough, P.L. Isotopes in pyrogenic carbon: A review. Org. Geochem. 2012, 42, 1529–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiz, G.; Wynn, J.G.; Wurster, C.M.; Goodrick, I.; Nelson, P.N.; Bird, M.I. Pyrogenic carbon from tropical savanna burning: Production and stable isotope composition. Biogeosciences 2015, 12, 1849–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higuera, P.E.; Peters, M.E.; Brubaker, L.B.; Gavin, D.G. Understanding the origin and analysis of sediment-charcoal records with a simulation model. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2007, 26, 1790–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, R.; Chipman, M.L.; Higuera, P.E.; Stefanova, I.; Brubaker, L.B.; Hu, F.S. Recent burning of boreal forests exceeds fire regime limits of the past 10,000 years. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 13055–13060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennebelle, A.; Aleman, J.C.; Ali, A.A.; Bergeron, Y.; Carcaillet, C.; Grondin, P.; Landry, J.; Blarquez, O. The reconstruction of burned area and fire severity using charcoal from boreal lake sediments. Holocene 2020, 30, 1400–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adolf, C.; Blarquez, O.; Colombaroli, D.; Dietze, E.; Marcisz, K.; Vannière, B. The International Paleofire Network (IPN). Past Glob. Changes Mag. 2020, 28, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffin, K.I.; Gillson, L.; Willis, K.J. Testing the sensitivity of charcoal as an indicator of fire events in savanna environments: Quantitative predictions of fire proximity, area and intensity. Holocene 2008, 18, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brubaker, L.B.; Higuera, P.E.; Rupp, T.S.; Olson, M.A.; Anderson, P.M.; Hu, F.S. Linking sediment-charcoal records and ecological modeling to understand causes of fire-regime change in boreal forests. Ecology 2009, 90, 1788–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlon, J.R.; Kelly, R.; Daniau, A.L.; Vannière, B.; Power, M.J.; Bartlein, P.; Higuera, P.; Blarquez, O.; Brewer, S.; Brücher, T.; et al. Reconstructions of biomass burning from sediment-charcoal records to improve data–model comparisons. Biogeosciences 2016, 13, 3225–3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brücher, T.; Brovkin, V.; Kloster, S.; Marlon, J.R.; Power, M.J. Comparing modelled fire dynamics with charcoal records for the Holocene. Clim. Past 2014, 10, 811–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Marle, M.J.E.; Kloster, S.; Magi, B.I.; Marlon, J.R.; Daniau, A.L.; Field, R.D.; Arneth, A.; Forrest, M.; Hantson, S.; Kehrwald, N.M.; et al. Historic global biomass burning emissions for CMIP6 (BB4CMIP) based on merging satellite observations with proxies and fire models (1750–2015). Geosci. Model Dev. 2017, 10, 3329–3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilgen, A.; Adolf, C.; Brugger, S.O.; Ickes, L.; Schwikowski, M.; van Leeuwen, J.F.N.; Tinner, W.; Lohmann, U. Implementing microscopic charcoal particles into a global aerosol–climate model. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018, 18, 11813–11829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itter, M.S.; Finley, A.O.; Hooten, M.B.; Higuera, P.E.; Marlon, J.R.; Kelly, R.; McLachlan, J.S. A model-based approach to wildland fire reconstruction using sediment charcoal records. Environmetrics 2017, 28, e2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snitker, G. Identifying natural and anthropogenic drivers of prehistoric fire regimes through simulated charcoal records. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2018, 95, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feurdean, A.; Vannière, B.; Finsinger, W.; Warren, D.; Connor, S.C.; Forrest, M.; Liakka, J.; Panait, A.; Werner, C.; Andrič, M.; et al. Fire hazard modulation by long-term dynamics in land cover and dominant forest type in eastern and central Europe. Biogeosciences 2020, 17, 1213–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belcher, C.M.; New, S.L.; Gallagher, M.R.; Grosvenor, M.J.; Clark, K.; Skowronski, N.S. Bark charcoal reflectance may have the potential to estimate the heat delivered to tree boles by wildland fires. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2021, 30, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byram, G.M. Combustion of Forest Fuels, in Forest Fire: Control and Use; Davis, K.P., Ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1959; pp. 61–89. [Google Scholar]

- Rothermel, R.C. A mathematical model for predicting fire spread in wildland fuels INT-115. In Forest Service; U.S. Dept. of Agriculture Research Paper: Ogden, UT, USA, 1972; p. 40. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, P.L. The Rothermel surface fire spread model and associated developments: A comprehensive explanation. In General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-371; USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wooster, M.J.; Roberts, G.; Perry, G.L.W.; Kaufman, Y.J. Retrieval of biomass combustion rates and totals from fire radiative power observations: FRP derivation and calibration relationships between biomass consumption and fire radiative energy release. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2005, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.P.; Scott, A.C.; Cope, M. Reflectance measurements and the temperature of formation of modern charcoals and implications for studies of fusain. Bull. Soc. Géolog. Fr. 1991, 162, 193–200. [Google Scholar]