Abstract

This research employs an integrated experimental and numerical simulation approach to investigate how varying angles of continuous elbows in a “Z”-shaped pipeline affect the deflagration behavior of hydrogen-propane-air mixtures. Findings indicate that centrifugal forces acting on the flame front as it traverses an elbow cause a distinctive “tongue-shaped” propagation along the inner wall. A cavity that generates unburned gas near the outer wall. The volume of this cavity increases significantly with the Angle of the elbow. The flame propagation is regulated by it and presents three distinct stages: the initial development section within the straight pipe section, the disturbance section when entering the first elbow, and the subsequent suppression section under the action of the cavity. The more intense turbulent combustion occurs at the 90° bend, with the highest peak flame velocity. On the contrary, the 120° and 150° elbows suppress the spread of flames. In addition, the angle of the elbow has a significant effect on the second overpressure peak, which exhibits strong non-linear growth. The value at 150° is 2.7 times greater than that at 30°. This is mainly caused by the energy focusing effect of the reflected pressure wave in the cavity magnified by the large-angle elbow. These findings provide mechanism-level understanding for the safe design of complex hydrogen pipeline systems.

1. Introduction

In response to the national “dual carbon” targets—aiming for carbon peak by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060 [1]—hydrogen energy has gained prominence as a clean alternative and is now integral to China’s strategic energy framework [2]. Thanks to policy promotion, hydrogen energy has become a key focus of energy transformation. More than one-third of central enterprises have already established the entire industrial chain, covering hydrogen production, storage, and refueling [3]. These central enterprises are making the most of their leading and driving roles in technological research and development, as well as infrastructure construction. This is giving the large-scale, commercial development of the hydrogen energy industry a strong impetus. During its industrialization process, the transportation of hydrogen energy has become one of the important factors influencing the development of the hydrogen energy industry. At present, there are various ways to transport hydrogen energy, mainly including long pipe trailer transportation [4], liquid hydrogen tanker transportation [5], ship transportation [6], and pipeline hydrogen transportation [7], etc. The advantages and disadvantages of different common hydrogen delivery methods are compared in Table 1. Pipeline transport is increasingly viewed as the future backbone for large-scale hydrogen distribution, primarily due to its economic viability and sustainability compared to other methods.

Table 1.

Advantages and disadvantages of different common hydrogen transport methods.

Currently, the construction of hydrogen pipelines has reached a total of more than 5000 km [12]. In pipeline transportation systems, hydrogen molecules tend to interact with the metal pipe walls. It induces a significant increase in the hardness of steel while causing a sharp decrease in its toughness. This thereby triggers the embrittlement phenomenon of the pipeline material (i.e., hydrogen embrittlement) [13]. This effect increases the risk of pipe body rupture under the action of the internal stress field, especially in stress concentration areas such as welded joints and pipe elbows [14]. Due to the superimposed effect of local microstructure defects and stress distribution gradients, hydrogen embrittlement damage is significantly increased, leading to a leakage risk in the pipeline. Hydrogen has a number of physical properties. These include being colorless and odorless. It also has an extremely low density [15]. Therefore, hydrogen leakage is not easily identifiable in real-time when it happens. When leakage occurs in a confined space, the gas will accumulate and remain due to the obstruction of diffusion [16], and then form a mixture of gases with explosive hazards. The explosive limit range of hydrogen is wide (4.0–75.6%vol) [17,18]. It has the characteristics of strong buoyancy, wide combustible range, and only 0.02 mJ of ignition energy [19,20]. Any source of fire may cause an explosion, posing a catastrophic danger. This characteristic makes hydrogen leakage in confined spaces highly likely to develop into explosion accidents.

To enhance the safety of hydrogen-containing pipeline systems and ensure the large-scale application and sustainable development of hydrogen energy within the energy system, there is an urgent need to gain a deeper understanding of the explosive combustion characteristics of hydrogen. For this reason, many researchers have adopted a method combining experimental studies and numerical simulations to systematically reveal the transmission characteristics of hydrogen in pipelines, the flame propagation laws during the explosion and combustion process, and the stable and continuous combustion mechanism through a combination of experimental research and numerical simulation. In terms of pipeline transportation, Raj et al. [11] studied the flow characteristics of hydrogen in pipelines through numerical simulation methods and found that the physical properties of hydrogen significantly affect its flow behavior in pipelines, including pressure distribution, flow velocity variation and turbulence characteristics. In terms of combustion characteristics, Qu et al. [21] systematically studied the influence mechanism of the equivalent ratio on the flame propagation characteristics of non-uniform hydrogen-air premixed gases by constructing a three-dimensional premixed model. The research results show that the flame propagation rate presents a non-monotonic variation trend of first increasing and then decreasing with the increase of the equivalent ratio. When the equivalent ratio is 1.2, the flame propagation rate reaches its maximum value. Qin et al. [22] quantitatively analyzed the influence of turbulence effect on flame acceleration by building a multi-obstacle deflagration experimental platform. The results show that the number of obstacles is positively correlated with the flame propagation rate. The data indicates that for each additional group of obstacles, the propagation rate can increase by approximately 41%. To build a safe and controllable combustion system, scholars have explored methods to suppress hydrogen detonation. Research has found that blending propane into hydrogen fuel can significantly suppress its deflagration tendency [23]. In addition, experimental studies have shown that adding propane can effectively control the laminar combustion rate and flammability limit of the mixed fuel [24]. Meanwhile, thanks to the high thermodynamic stability of propane, the probability of deflagration during the combustion of the mixed fuel is also effectively reduced. Masoumi et al. [25] conducted a study combining experiments and numerical simulations to investigate the stability of ammonia-methane and ammonia-hydrogen dual-fuel laminar flow propagation flames. The study examined the effects of different equivalence ratios, fuel compositions, initial temperatures, pressures, and diluent addition conditions on flame stability. Kazemi et al. [26] used the CFD numerical simulation method, which was verified by experiments on pure hydrogen and methane flames, to study the critical diameter and stability curves of non-premixed turbulent hydrogen-methane flames with different volume ratios, at various leakage diameters and driving pressures. The finding was that an increase in hydrogen content in the mixed fuel would result in a significant reduction in the critical diameter and a widening of the flame stability range. Meanwhile, Kazemi et al. [27] explored flame stability in hydrogen non-premixed flames at different nozzle diameters and driving pressures, establishing and validating a numerical model based on CFD in the process. It was found that a significant impact on the flame state is caused by pressure. Under low pressure, adhered flames are more likely to form. As pressure increases, these flames transform into lifted flames. When pressure exceeds the critical pressure, blowout occurs. In terms of combustion stability, Peng et al. [28] found that a specific proportion of a hydrogen-propane mixture could significantly broaden the stability range. This was especially the case when the equivalent ratio was 0.8. In terms of flame morphology, the research by Gao et al. [29] revealed the key influence of the Frude number on flame height: when Fr < 0.4, the flame height slightly increased with the increase of hydrogen proportion; When Fr is greater than 0.4, it drops rapidly. Meanwhile, the height of flame detachment is directly proportional to the outlet velocity of propane and inversely proportional to the volume ratio of hydrogen.

In a straight-tube hydrogen-air premixed gas explosion, Xu et al. [30] found that there was a coupling effect between the pipe length and the hydrogen concentration. The research reveals the key influence of this coupling effect on the explosion pressure, flame morphology, and the formation location of the new explosion system. By means of experiments and numerical simulations, Gaathaug et al. [31] investigated the transformation process of hydrogen-air mixtures from dedetonation to detonation in a square channel containing a single obstacle. Through comparative experiments, Li et al. [32] confirmed the extreme danger of hydrogen explosion. Compared with a methane explosion, a hydrogen explosion spreads faster, has a higher peak overpressure (exceeding 1.5 MPa), and is more likely to develop into a detonation, significantly increasing the explosion’s intensity. In actual hydrogen transmission pipelines, the risk of explosion can be significantly increased by complex structures such as elbows. Research shows that the geometry of the elbow can alter the flow field and induce vortices, thereby accelerating flame propagation and intensifying explosive overpressure [33]. The essence lies in that the geometric configuration of the elbow will induce the coupling effect of the centrifugal force field and the turbulent flow field. This coupling effect is precisely the fundamental cause that alters the flame propagation path and velocity distribution, ultimately leading to an increase in risk. The Dean number (De) has been proven to be a key parameter for quantitatively describing this influence. De quantifies the relative importance of centrifugal and viscous forces [34], which are directly related to the intensity and instability of the secondary flow in the elbow [35]. In the case of flammable gas explosions, the distortion of the flow field induced by curvature significantly enhances turbulent mixing, thereby severely affecting the structure of the flame, its propagation speed and the overpressure [36]. At the same time, the interaction between turbulence and chemical reactions is equally crucial and is characterized by parameters such as the Damköhler number (Da, the ratio of the time scale of the chemical reaction to the time scale of the flow) and the Karlovitz number (Ka, the ratio of the time scale of the flame to the time scale of the Kolmogorov vortex) [37,38]. Therefore, gas explosions in curved pipelines are complex, multi-scale physical processes jointly dominated by Re (global flow), De (the effect of curvature), Da and Ka (the interaction between turbulence and chemical reactions). Existing studies have utilised these theoretical frameworks to reveal fundamental phenomena such as flame acceleration and vortex generation in single-elbow pipe structures in greater depth. Guo et al. [39] discovered that the explosion shock wave’s overpressure increased a lot with an increase in the turning angle. Zhou et al. [40] Further studied and pointed out that in the release of high-pressure hydrogen, 60° elbow pipes are more likely to cause severe spontaneous combustion than 90° elbow pipes. At the mechanism level, Mei et al. [41] revealed that the interaction between the pressure wave and the flame in the elbow pipe is the key. Due to the shortened wave reflection distance, the overpressure oscillation frequency and growth range of the elbow pipe far exceed those of the straight pipe, and are positively correlated with the angle.

However, most of the existing research focuses on straight pipe sections or single elbows. In real industrial pipeline systems, continuously arranged elbows (such as “Z”-shaped pipes) are more common. In this configuration, the distortion of the flow field generated by the upstream elbow, the incompletely combusted mixture and the pressure wave will affect the explosion process in the downstream elbow continuously, resulting in a cumulative effect. At present, there is a lack of systematic research on how the key geometric parameter of the pipe bending angle affects the flame dynamic evolution and pressure wave focusing mechanism of mixed fuels. These fuels include hydrogen-propane. This is in the continuous pipe bending system. To address the above research void, this study utilizes an integrated approach of experimental testing and numerical simulations to comprehensively examine how the elbow angle in the “Z”-shaped pipeline affects the explosion characteristics of hydrogen-propane mixed gas. The research will focus on analyzing the dynamic evolution of the flame leading edge, the variation law of the propagation rate, and the characteristics of overpressure development. This research aims to provide a scientific basis for the safety design and optimization of related pipelines, thereby ultimately enhancing the safety performance of the pipeline system.

2. Experimental Steps

2.1. Experimental Setup and Pipeline Dimensions

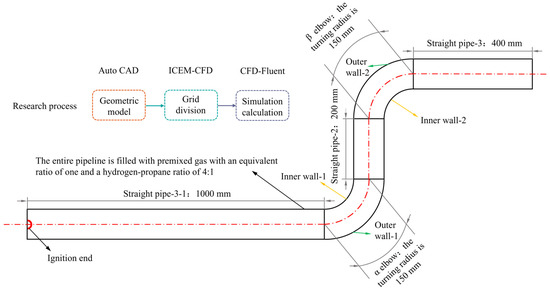

Five elbows at different angles were used in the setup. The elbow pipeline consisted of five segments: straight pipe-1, elbow, straight pipe-2, elbow, and straight pipe-3. The pipe with = = 0° served as a straight pipe control for comparison with curved configurations. The lengths of the first, second, and third straight pipe segments were 1000 mm, 200 mm, and 600 mm, respectively.

The entire pipeline featured a circular cross-section with a 100 mm diameter, and elbows had a turning radius of 150 mm, tested at angles of 30°, 60°, 90°, 120°, and 150°. Two elbows were positioned between the first and second pipe segments, and between the second and third segments, forming an overall “Z” shaped pipeline. The pipeline body was constructed from 5 mm thick Q235 carbon steel, with each small segment measuring 200 mm in length. Segments were secured using eight 6 mm bolts per connection. This can ensure the structural stability of the pipeline during the experiment. To enhance the sealing performance, rubber gaskets are placed at the connection points of each section, thus ensuring the overall sealing of the pipeline. Table 2 summarizes the parameters of the pipeline.

Table 2.

Parameters of the pipeline.

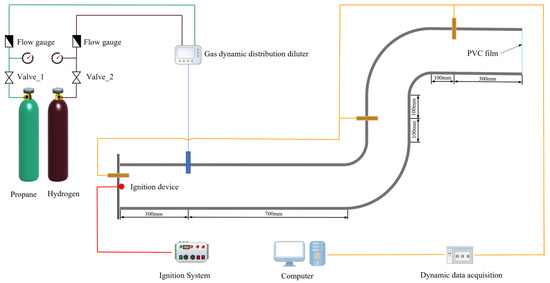

Figure 1 presents a schematic illustration of the experimental setup. The experimental system comprised segmented straight pipes, elbows, CY301 digital pressure sensors (Range: 0–100 MPa, sampling frequency: 1 kHz, accuracy: ±0.1% F.S.), a KTGD-B adjustable igniter, and LPG (Liquefied Petroleum Gas) cylinders with a propane purity of at least 95%, hydrogen gas cylinders with a hydrogen purity of no less than 99%, a dynamic data acquisition system, a gas dynamic gas mixing and dilution instrument, and valves. The specific models are shown in Table 3. The pipe’s left end was closed off using a steel plate equipped with five 20 mm threaded holes. The ignition end was placed at the center hole of the steel plate. The remaining holes can be used for connection with other experimental equipment, such as pressure sensors. Additionally, each small pipe section featured a 20 mm aperture at its central top section, facilitating equipment connections such as gas inlet ports. The pipe’s end was closed off using PVC (Polyvinyl Chloride) film to avoid gas leakage prior to ignition during the experiment. The pressure sensors were positioned respectively at the hole locations 30 mm to the right of the ignition end, 100 mm to the left of the second pipe section, and 100 mm to the left of the third pipe section.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the experiment.

Table 3.

Instruments used in laboratories.

2.2. Experimental Method

The experimental investigation was conducted according to the following procedure to ensure consistency and reproducibility.

First, each pipe section was assembled with the elbows to form the “Z”-shaped configuration depicted in Figure 1. The assembled pipeline was then mounted onto a steel support frame. The outlet of the pipe was sealed with PVC film to contain the gas mixture before ignition.

Subsequently, all experimental instruments were connected. The igniter, dynamic data acquisition system, and gas distribution system were interfaced with the pipeline at their designated ports. Following the connections, the pressure sensors and data acquisition system were powered on and set to standby mode to await the trigger signal.

The gas mixture was prepared using a dynamic gas mixing and dilution instrument. The valves of the LPG cylinder (propane content ≥ 95%) and the hydrogen cylinder (hydrogen content ≥ 99%) were opened. The instrument was set to a proportional mode to achieve a hydrogen-to-propane volume ratio of 4:1. Upon activating the instrument and the J-LY-20 gas circulation pump (Nanjing Longyi Technology Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China)), the hydrogen-propane mixture was introduced into the pipeline until it was completely filled, with adequate time allowed to ensure a homogeneous mixture.

After the filling process was complete, the gas distribution instrument and the circulation pump were switched off and disconnected from the pipeline to isolate it. The power supplies for the igniter and the pressure sensors were then activated simultaneously. The ignition energy was regulated via computer control to 20 J, and the ignition switch was manually triggered to initiate the deflagration.

For experiments investigating other elbow angles, only the and elbow segments needed to be disassembled and replaced before proceeding with the next configuration. The operational sequence for all subsequent tests remained identical to that described above. To guarantee the reliability of the experimental data, each explosion test under a given configuration was repeated three times.

3. Numerical Model

The numerical simulation process is grounded on the pipeline illustrated in Figure 2. The research procedure was primarily split into three components: geometric model development, mesh partitioning, and simulation execution. Numerical simulations with the LES model and the premixed combustion model were employed. The premixed combustion model has been elaborated upon in relevant literature [42,43]. Based on Favre filtering resolving large-scale turbulence was solely focused upon. The governing equations utilized in the large eddy simulation included filtered three-dimensional transient mass conservation [44], momentum conservation [45], energy conservation [46], and the coupling of constitutive equations with state equations [47], as presented subsequently:

where denotes the density, represents the velocity, stands for time,, are the velocity components, and indicates pressure. refers to the viscous stress tensor, denotes enthalpy, represents the thermal conductivity coefficient, and signifies temperature. Furthermore, reconstruction of the component transport equation [48] was employed. Specifically, c = 0 (unburned mixture) and c = 1 (burned mixture):

where denotes the mass fraction of the kth species. The superscript represents unburned reactants, eq indicates chemical equilibrium, and is a constant—typically 0 for reactants and 1 for a small portion of products. Moreover, in premixed combustion processes, the flame front is thickened to achieve more precise computational outcomes. Consequently, the Zimont combustion model was utilized to thicken the flame [49], with its turbulent flame calculation equations as follows:

where denotes the model constant. stands for the mean square velocity. signifies the laminar flame speed, denotes the molecular thermal conductivity coefficient of the unburned mixture, and indicates the turbulent length scale.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the pipeline.

3.1. Grid Generation

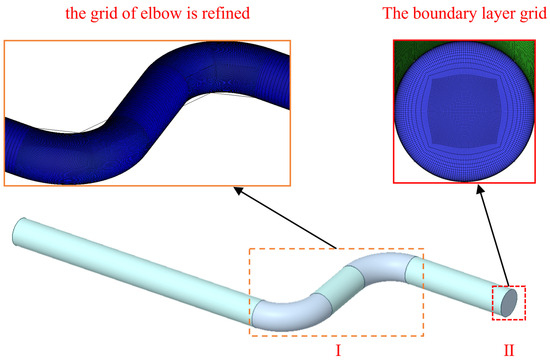

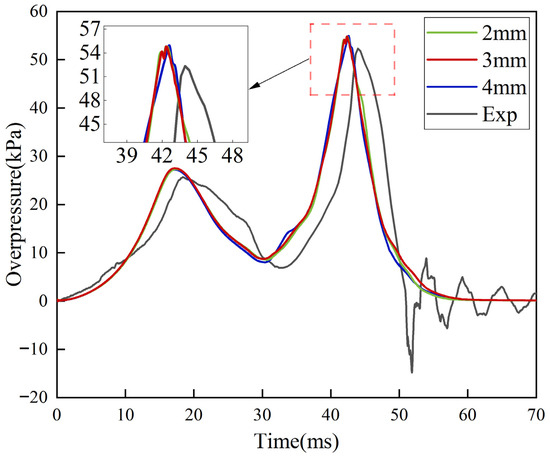

First, the geometric dimensions of the pipeline on the Auto CAD 2020 software platform were defined. Then, the mesh model and size details were generated through the ICEM CFD 2021 R2 software. Given that the structural grid enhanced the accuracy and convergence of computational outcomes, it was employed to partition the fluid computational domain as shown in Figure 3. Considering both computational cost and accuracy, three grid sizes (2 mm, 3 mm, 4 mm) were selected to analyze and verify the grid independence of the model (as shown in Figure 4) [50,51]. By comparing numerical simulation results with experimental data, it was observed that when the grid size was 3 mm, the simulated results most closely matched the experimental findings. This study focuses on investigating the influence of elbow angle on hydrogen-propane explosion characteristics. To obtain more precise simulation results at the elbow section, a refined 3 mm × 3 mm × 3 mm grid was employed for this region (Figure 3I). In Figure 3II, a boundary layer mesh was employed to partition the computational domain near the pipe wall. Mesh density gradually decreased along the boundary layer direction. The first layer had a height of 0.1 mm. The expansion coefficient was set to 1.2. Mesh density progressively decreased along the boundary layer. Furthermore, constrained by computational resources and time limitations, a 5 mm mesh size was employed for the straight pipe section to implement a gradient mesh refinement strategy. This approach effectively balances computational efficiency with simulation accuracy requirements. Specifically, a gradient mesh design was adopted for the straight pipe region, where the mesh size gradually transitions from 3 mm at the elbow to 5 mm. This transition was achieved by controlling the expansion ratio and number of layers. This ensured a smooth variation in mesh density, preventing numerical oscillations caused by abrupt size changes. This strategy significantly reduced the overall number of meshes, substantially shortening the duration of each simulation run. Figure 4 illustrates the longitudinal distribution details of the gradient mesh in the straight pipe section, showing the mesh uniformly expanding along the axial direction, fully accommodating the evolving characteristics of the explosive flow field.

Figure 4.

Grid independence verification.

3.2. Boundary and Initial Settings

The pipe wall of the elbow model shown in Figure 2 was set to be non-slip. Because the explosion test was completed in an instant and lasted for a short time, its impact on the temperature of the inner wall of the pipeline was negligible. To simplify the model calculation and improve the simulation efficiency, the boundary condition of the pipeline was set as the adiabatic wall boundary condition. To prevent pressure attenuation caused by pressure wave reflection, the pipe outlet was set to be non-reflective. The necessary parameters required for the calculation included the kinematic viscosity, thermal conductivity, and laminar flame velocity of the premixed gas. The laminar flow flame velocity was experimentally measured by Tang et al. [52] and set at 0.706 m/s. The thermal conductivity evaluated by the polynomial function of the fifth power of temperature was approximately 0.068 W/(m·K) [53]. Based on Sutherland’s visibility law [54], the viscosity was set at 1.76189 × 10−5 kg/(m·s). The initial temperature was set at 297.15 K. The initial relative pressure inside the pipeline was set to 0 MPa [55], and the initial velocity and reaction process variables were all set to zero. To control the pre-flame stretching and quenching, the critical strain rate was set at 5 × 10−4. At the ignition end of the elbow pipe model, a spherical ignition area with a diameter of 10 mm was captured [46], and the reaction process variable c within the region was set to 1 to simulate the ignition function.

3.3. Discussion on Model Limitations and Validation

The Large Eddy Simulation (LES) model employed in the present study relied primarily on experimental data from 90° elbows for parameter calibration and validation. This validation process demonstrated that the model accurately captured key physical phenomena during elbow explosions under the aforementioned geometric configurations. It encompassed centrifugal force-dominated flame morphology evolution, the formation mechanism of flow field cavitation structures, and the dynamic characteristics of pressure wave propagation and interaction, thereby establishing a foundation for subsequent research. However, the quantitative accuracy of this model across the entire range of elbow angles—particularly at the extreme angles of 30° and 150°—had yet to be comprehensively validated through experimental measurements. Consequently, research conclusions drawn for such extreme angular conditions were essentially extrapolated inferences based on physically validated models. Their quantitative reliability remained contingent upon corroboration through dedicated experimental data.

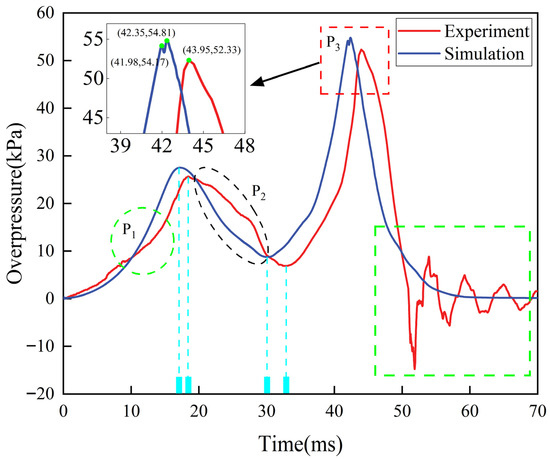

Regarding boundary condition settings, the adiabatic wall assumption employed in the simulation process differed from the actual heat transfer characteristics of steel pipes observed in experiments. This assumption disregarded the heat conduction loss effect on the pipe wall during combustion. This simplification had been confirmed as the key factor causing discrepancies between simulation results and experimental measurements. Specifically, the simulated overpressure peaks were systematically higher than the experimental data (as shown in Figure 5). However, this heat transfer effect exhibited consistent patterns across all simulated cases. Consequently, it did not undermine the validity of comparative analyses regarding the influence of different elbow angles on explosion characteristics, and the relevant qualitative conclusions remained of reference value.

Figure 5.

Real and simulated pressure characteristics.

Furthermore, the conclusions drawn in this study were based on specific initial conditions and geometric parameter settings. These comprised a fixed hydrogen/propane mixture ratio of 4:1, a constant pipe diameter of 100 mm, and a fixed ignition strategy involving central ignition at the closed end. The elbow angle served as the sole variable parameter. This controlled-variable research methodology ensures the systematic and accurate analysis of elbow angle effects. However, it also limits the generalizability of quantitative results. Although the core physical mechanisms identified in the study (such as centrifugal flame guidance and cavity-induced turbulence enhancement) possess a degree of universality, the relative contribution of each mechanism during the explosion process and the ultimate explosion intensity remain significantly influenced by parameters such as fuel mixture ratio and pipe geometric dimensions. Concurrently, different ignition locations (e.g., sidewall ignition, multi-point ignition) alter the spatial distribution characteristics of the unburned gas reservoir and the structure of the turbulent intensity field. This, in turn, influences the three-stage evolution pattern of flame acceleration and the pressure wave superposition effect. This factor has not been sufficiently considered in current research, making it difficult to directly generalize quantitative conclusions to other operating conditions. This constitutes a potential limitation in the application of the model.

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Verification of the Validity of Numerical Models

Figure 5 shows the pressure comparison chart between the 90° pipe bending experiment and the simulation. A fundamental distinction existed at the outlet boundary: the experiment used a rupturable PVC membrane, whereas the simulation used a non-reflective boundary. This discrepancy directly accounted for the pronounced pressure drop observed at position P1 in the experiment. This is consistent with previous studies [56,57,58]. However, this represented a transient venting event that the simulation was unable to capture. Consequently, a direct comparison at point P1 immediately after diaphragm rupture was not reasonable for model validation. Therefore, verifying the model’s ability to capture internal explosion dynamics primarily relied on data from locations less affected by the venting process. As shown in Figure 5, the simulated pressure at positions P2 and P3 matched the experimental data remarkably well in terms of the rising trend, peak pressure timing, and decay curve. This strong correlation indicated that the LES model reliably reproduced the core physical characteristics of flame propagation and pressure wave dynamics within the pipe. Despite idealized boundary conditions, both simulation and experiment demonstrated consistent early rapid pressure rise trends at P1. The time interval until the first pressure peak occurred was merely 2 ms. The error in peak pressure values was within the acceptable range for such transient events. The overall consistency, particularly at internal monitoring points, confirmed that the numerical model employed effectively captured the explosion characteristics of hydrogen-propane-air mixtures within “Z”-shaped conduits.

Compared with the experiment, the simulation was unable to simulate the existence of polyethylene film; thus, the pressure wave showed a gentle rise. In numerical simulation, the pipe boundary was set under adiabatic non-slip conditions. This means that the energy and pressure waves generated by the flame propagation will not dissipate or be blocked. However, the main body of the experimental pipeline was made of Q235 steel, and its inner wall had a certain degree of roughness. Moreover, it absorbed some heat during the explosion process. It is precisely this difference in boundary conditions between the ideal situation and reality that caused the pressure wave in the simulation to reach its peak earlier than the experimental value [51]. As the explosion reaction proceeded, the pressure began to drop. The downward trend of the simulation and experimental curves at this stage showed good consistency, indicating that the adopted numerical model effectively captured the explosion pressure characteristics of the hydrogen-propane-air premixed gas in the 90° elbow pipe. The experimental pressure at position P2 in the figure dropped more slowly. This can be attributed to the hindering effect of the roughness of the inner wall of the pipe on flame propagation, thereby slowing down the release rate of energy. Surface roughness may potentially promote combustion by enhancing turbulence intensity and similar mechanisms. However, under the experimental conditions employed, the roughness of the pipe inner wall primarily manifested as a macroscopic flow resistance. Specifically, increased wall friction and turbulent energy dissipation consumed the flow energy that propels flame acceleration. The formation of larger-scale low-velocity zones or separation regions near the wall physically prevented the continuous advancement of the flame front. More significantly, for flames already in a state of intense turbulence, the ‘enhancement’ effect of additional wall roughness on combustion tended towards saturation, whilst its ‘dissipation’ effect continued to increase linearly, becoming the dominant factor. Comparing the experimental and simulated results in Figure 5, it was observed that the experimental pressure rise rate was slower and the peak was delayed, which was more compatible with the aforementioned net suppression effect. Therefore, although roughness theoretically exhibited dual characteristics, under specific pipe dimensions, flow conditions, and roughness parameters, its macroscopic effects on flow resistance and energy dissipation outweighed its potential to enhance microscopic combustion processes. Consequently, the overall flame propagation and energy release rates observed in the experiment exhibited a decelerated trend relative to the ideal adiabatic simulation results.

At the P3 position, when the pressure rose again to the second peak, the simulation curve accurately captured a slight pressure fluctuation. However, the experimental data did not record this phenomenon. This was mainly due to the accuracy limitation of the experimental pressure sensor. Because the sampling interval was greater than the frequency of pressure changes during this rapid response period, it was impossible to analyze such subtle changes. During the final phase of the explosion, positive and negative pressure fluctuations appeared on the experimental curve. These fluctuations were not captured by the simulation. They resulted from the combined effects of several real-world factors absent in the idealized numerical model. These include: (i) Complex three-dimensional transient flow phenomena (e.g., secondary flows and vortex shedding at pipe junctions), amplified by non-ideal wall conditions such as surface roughness and sedimentation; (ii) Minor flow disturbances at pipe joint interfaces; (iii) Low-amplitude environmental noise, such as background vibrations and electronic noise within the data acquisition system. Simulations conducted under adiabatic and hydraulically smoothed assumptions naturally filter out these real-world complexities, resulting in a smoother pressure decay profile. From the perspective of the overall pressure change trend, the relative error between the simulation and experimental results was relatively small. The average relative error was controlled within 5%. Further, through the comparative analysis of multiple repeated experimental data, it was confirmed that the numerical simulation results had good repeatability and stability.

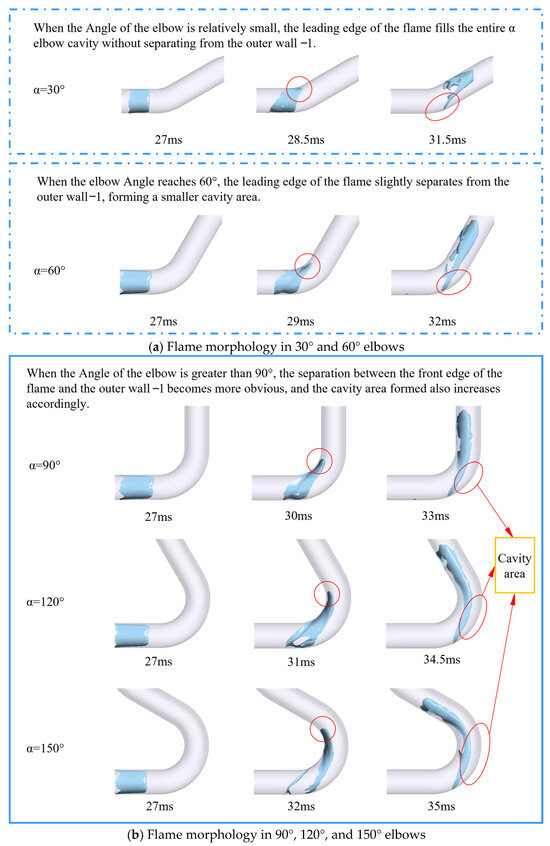

As shown in Figure 6a,b, the transient process was captured when the flame front passed through the first section of the elbow at different angles ( elbow) but did not reach the second section of the elbow ( elbow). It can be intuitively observed that the structure of the elbow pipe had a significant impact on the evolution of the flame leading edge structure during an explosion. When the flame passed through the elbow, the front surface significantly extended towards the inner wall-1 side, forming a unique “tongue-like” flame structure (marked by the red circle in the figure) [59]. As the angle of the elbow increased from 30° to 150°, the separation phenomenon between the leading edge of the flame and the outer wall became more and more obvious. Specifically, in a 30° elbow, the leading edge of the flame filled the cavity of the elbow without separation. When the angle increased to 60°, the flame front began to slightly separate from the outer wall. When the angle exceeded 90°, the front surface and the outer wall were clearly separated, and the degree of separation intensified with the increase of the angle. Eventually, a clear cavity area was formed inside the elbow (marked by the red ellipse in the figure).

Figure 6.

Simulated flame fronts of α-elbow joints.

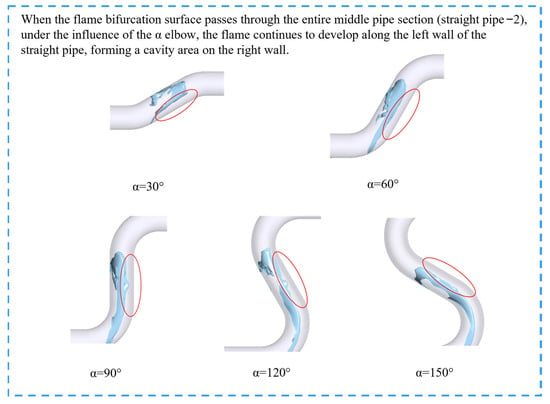

As shown in Figure 7, when the flame entered the straight pipe-2 section for propagation, its behavior was continuously affected by the upstream α elbow. Due to the guiding effect of the elbow, the leading edge of the flame spread in close contact with the left wall of the straight pipe-2 connected to the inner wall of the α elbow. At the same time, a local cavity area was formed on the right wall (marked by an ellipse in the figure). As the flame front continued to advance, the area of its leading edge showed an expanding trend. The flame shape underwent discontinuous changes, causing the “tongue-shaped” flame structure previously formed at the elbow to gradually disappear. By comparing the working conditions from different angles, it was found that the angle of the elbow will affect the specific propagation trajectory of the flame and the initial shape of the cavity area. However, regardless of how the angle changed, the formation of a local cavity area in the straight pipe-2 section and its influence on the subsequent evolution of the flame were common key features.

Figure 7.

Simulated flame fronts of Straight Pipe-2.

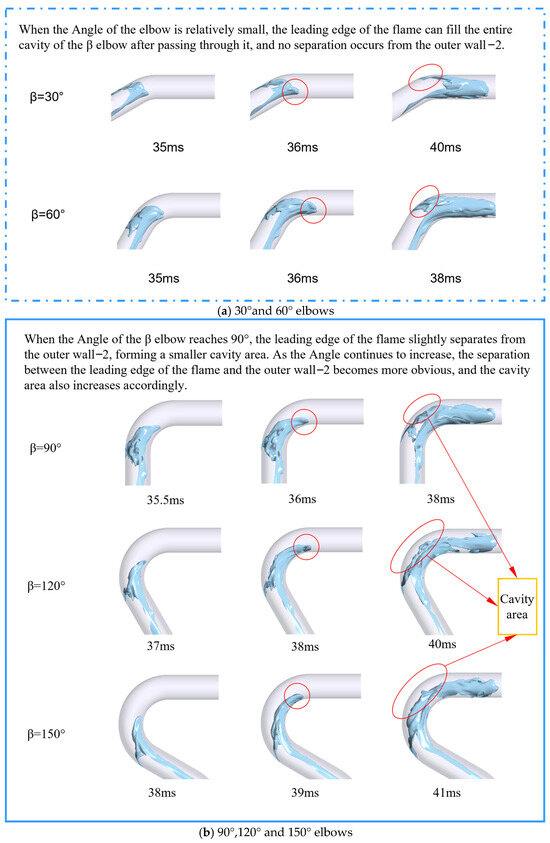

As shown in Figure 8a,b, when the flame front passed through the second elbow ( elbow), its evolution law was similar to that when it passed through the α elbow. The front will extend along one side of the inner wall-2, causing the “tongue-shaped” flame structure that was previously eliminated in the straight pipe section to reappear (as shown by the red circle in the figure). The flame shape was also significantly regulated by the angle of the elbow: when the angle was small (30°, 60°), the flame filled the entire elbow chamber without separating from the outer wall-2. As the angle increased, the flame front began to separate from the outer wall. Moreover, the degree of separation intensified as the angle increased, and the cavity area formed also expanded accordingly (as shown by the red ellipse in the figure). From this, it can be known that when the flame passed through the elbow, its front always extended towards the inner wall side. Moreover, the larger the angle of the elbow, the closer the combustion of the combustible mixture was to the inner wall. In a continuous elbow structure, due to the influence of the previous elbow, the flame formed a cavity area in the middle section of the pipe. This was a key flame dynamic feature in such pipes.

Figure 8.

Simulated flame fronts of -elbows.

The formation and separation of the “tongue-shaped” flame at the elbow were fundamentally driven by the changes in the flow field caused by the geometric structure of the pipeline. When the flame front entered the elbow, the high-speed airflow was deflected towards the outer wall under the action of centrifugal force. This led to the formation of a low-pressure area near the inner wall, which in turn prompted the flame to extend towards the inner wall, creating a “tongue-like” structure. Meanwhile, the outer wall area generated vortices due to the separation of gas flow, causing the accumulation of unburned mixed gas and forming a cavity area. As the angle of the elbow increased, the centrifugal effect intensified. The separation distance between the flame and the outer wall had significantly increased, and the cavity area also expanded accordingly. Numerical simulation quantified this relationship: in elbows of 90° and above, the volume of the cavity area increased significantly compared to elbows of 30°. This indicates that the large-angle elbow will intensify the non-uniform distribution of the flame front. This phenomenon was closely related to the variation of turbulence intensity. When the Reynolds number inside the elbow rose to a sufficiently high value, the intense turbulent pulsation caused the flame front to break, thereby further strengthening the separation tendency. Furthermore, the elimination and recurrence of the “tongue-shaped” flame between the elbow and the elbow revealed the cumulative effect of the continuous turning of the pipeline on the flame dynamics. Among them, the local cavity area in the middle section of the pipe served as a temporary reservoir for unburned gas.

4.2. Patterns of Flame Propagation Within Curved Pipes

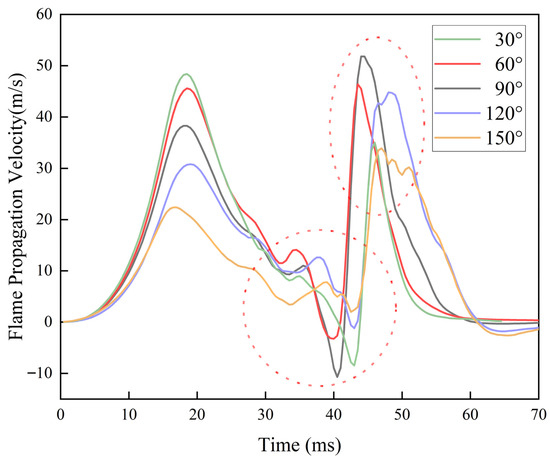

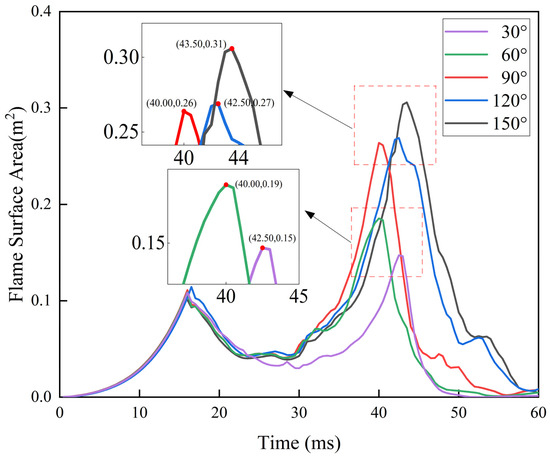

Figure 9 and Figure 10 show the variations in flame propagation speed and area of pipes bent at different angles. As can be observed in Figure 8, the oscillation change of flame propagation speed was almost the same under all working conditions. And there were three speed peaks during the propagation process. The flame development was divided into the early stage, the middle stage, and the late stage, which respectively correspond to the development of the three speed peaks. It is obvious that under different working conditions, the values of the three speed fronts all showed significant differences. This indicates that the continuous elbow structure had a significant impact on the development of the flame.

Figure 9.

Simulation results of flame propagation velocity in elbows at different angles.

Figure 10.

Simulation results flame surface area for elbows at different angles.

In the early stage of flame propagation, due to the simple structure of the pipeline, the flame advanced rapidly in an approximately straight line. Figure 10 shows that before the flame reached the elbow, the flame area curves corresponding to the elbow at different angles almost coincided. This indicates that the structure of the elbow had little influence at this stage. Meanwhile, as can be seen from Figure 9, the flame propagation speed changed steadily at this stage. Moreover, the value of speed peak 1 showed a gradually decreasing trend as the elbow angle increased. At 27 ms, there was a significant fluctuation in the flame propagation speed. This marked the propagation entering the middle stage, that is, the flame began to enter the elbow area. The flame front was deformed due to the influence of the geometric shape of the elbow. Under the action of centrifugal force, the change in the direction of the airflow caused the flame to accelerate. But the speed only increased slightly. This was mainly because the flame entered the bend before it had fully developed. Moreover, the distance between the elbow and the elbow was relatively short, which caused the flame to quickly enter the straight pipe-2 after passing through the elbow. Due to the influence of the elbow, sufficient velocity accumulation cannot be formed. Furthermore, as the angle of the α elbow increased from 60° to 150°, the peak time of speed peak 2 was gradually postponed. This is because the increase in the angle of the elbow caused the flame’s propagation path within the elbow to lengthen, thereby delaying the time to reach the peak speed. About 35 ms later, the flame developed into the late stage and entered the elbow area. As shown in the red ellipse in Figure 7, the peak value of speed peak 3 first increased and then decreased with the increase of the elbow angle. And it reached the maximum at 90°. At this time, the contact area between the flame front and the inner wall of the elbow increased the fastest and the turbulent mixing effect was the strongest. When the angle exceeded 90°, the peak value of speed peak 3 began to decline. This was mainly because the cavity area formed by the large-angle bend hindered the continuous advancement of the flame forward. The expansion of the range of the flame striker led to a significant increase in propagation resistance, offsetting the increase in speed. Meanwhile, the local accumulation of unburned gas in the middle section of the pipe also reduced the combustion reaction rate. The variation pattern of the flame surface area in Figure 10 is highly consistent with this: at 90° working conditions, the surface area reached a peak much higher than that at other angles at the fastest speed. However, the attenuation in the later stage was also more severe. This propagation characteristic of “early growth rate, middle suppression, and late intensification” reveals the dual mechanism of continuous elbow on flame dynamics: on the one hand, it promotes flame acceleration through enhanced turbulence; on the other hand, it causes energy dissipation due to the cavity effect. Numerical simulation further indicated that when the elbow angle exceeded 120°, both the oscillation amplitude of the flame propagation speed and the surface area expansion rate decreased accordingly. This indicates that the large-angle elbow may ultimately suppress the stable propagation of the flame by altering the topological structure of the flow field.

This unique three-stage propagation pattern arose from the interaction between the continuous curved-tube geometry and turbulent combustion. During the initial phase (Peak 1), the flame accelerated within the straight tube section, with its dynamics primarily governed by the Reynolds number and Damkoler number, reflecting the competition between turbulent intensity and chemical reaction rates. Upon entering the first bend (mid-phase, Peak 2), the Dean number became the critical parameter. Centrifugal forces dominated flame redirection and acceleration, though peak propagation was delayed due to the elongated propagation path. In the later stage (peak 3), the flame entered the second elbow. By this point, the flow field had been pre-conditioned by the upstream elbow and the intermediate cavity, becoming saturated with unburned gas exhibiting high turbulence. The Karlowitz number (Ka) increased at this stage, indicating enhanced influence of small-scale turbulence on the flame front. Consequently, the most intense combustion and velocity peaks occurred at the 90° bend (which exhibits optimal De-turbulence matching). Conversely, for bends with angles ≥ 120°, the excessive cavity volume led to a reduction in the local Da number (shortening the flow timescale while relatively lengthening the reaction timescale). This diminished combustion efficiency, thereby inhibiting flame propagation.

4.3. Development of Explosion Overpressure Under the Influence of Bends

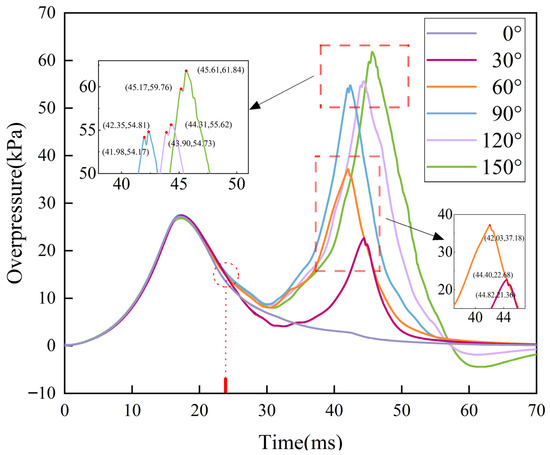

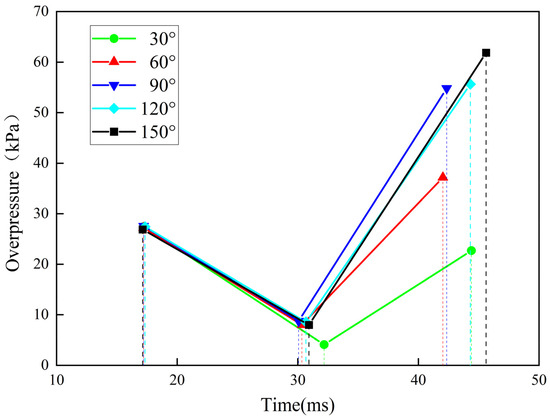

Figure 11 shows a comparison chart of pressure data for five simulated working conditions and the control group. Compared with the control group, the pressure time history curves of the other five working conditions were all bimodal structures. From the first peak, that is, the 0–24 ms period, it can be seen that the pressure curves of the five working conditions almost overlapped with those of the control group. And the upward and downward trends were consistent; that is, the existence of the elbow pipe had no impact on the pressure evolution pattern in this area. It can be seen from the figure that the pressure was in a uniformly rising state before reaching the first pressure peak. This is because after ignition at one end of the pipeline, the hydrogen-propane-air mixture began to deflagrate. The flame spread at an accelerated speed along the axis of the tube. Constrained by the pipe wall, the combustion products and unburned gases only expanded towards the end of the pipe (the explosion venting port). This generated a sparse wave that propagated towards the closed end (ignition end). Therefore, the initial pressure increase was not severe. As the flame continued to spread, the PVC film at the end of the pipe did not yet break, causing energy to accumulate continuously inside the pipe and the local pressure to keep rising, thus forming the first pressure peak. When the local pressure reached the rupture threshold of the diaphragm, the diaphragm underwent an instantaneous rupture. High-pressure gas was rapidly ejected outward through the break, causing a sharp drop in the internal pressure of the pipeline.

Figure 11.

Simulation results of explosion overpressure comparison of elbows at different angles.

However, during the development stage of the second pressure peak (approximately 30–50 ms), the pressure evolution under different elbow angle working conditions showed significant differences. The mechanism ensured that after the diaphragm broke for the first time, the remaining flammable gas in the pipeline continued to burn. At the same time, the rapid release of high-pressure combustion products caused intense pressure disturbances, forming reflected waves within the pipeline. When these reflected waves propagated to the elbow structure, their complex geometric shapes had a crucial impact on the propagation path and the superposition effect of the pressure waves. As shown in Figure 12, with the increase of the elbow angle, the second pressure peak showed a distinct increasing trend, and the rate of pressure rise accelerated. Specifically, when the elbow angle was 60°, the second pressure peak was approximately 1.6 times that of a 30° elbow. When the angle increased to 90° and 120°, the second peak value significantly rose to 2.4 times that of the 30° elbow. When the angle reached 150°, the second peak reached its maximum value, approximately 2.7 times that of a 30° elbow, and the pressure time-history curve was steeper near the peak. This phenomenon was closely related to the morphological changes of the flame leading edge observed in Section 4.2. The larger elbow angle intensified the separation of the flame front from the outer wall, thereby forming a larger low-pressure cavity area inside the elbow (as shown by the red ellipses in Figure 5 and Figure 7). When the reflected pressure wave propagated to this area, due to the significant pressure gradient between the high-pressure zone and the low-pressure cavity, the wavefront was distorted, and an energy focusing effect occurred. This effect caused the energy of the wave to be highly concentrated in a specific area (such as near the outer wall of the elbow or the downstream straight pipe section), eventually leading to a sharp increase in local pressure in that area and forming a higher second pressure peak. An increase in the angle of the elbow impeded the smooth propagation of pressure waves and prolonged their reflection and superposition time in the elbow area. This further intensified the aforementioned pressure-boosting effect. Therefore, the existence of the elbow structure and the increase in its angle mainly significantly intensified the overpressure development in the later stage of the explosion by altering the flame shape (inducing the formation of the cavity area) and disturbing the propagation and superposition process of the pressure wave. This effect was particularly evident in the substantial increase in the second pressure peak. During the latter stages of the explosion, the unburned gases trapped within the cavity did not remain in a state of permanent stasis. Instead, they underwent turbulent mixing with the combustion products due to the entrainment effect of the main flow. After passing through the elbow, the turbulently mixed, fuel-enriched gas mixtures underwent delayed combustion downstream. These non-uniform, unsteady combustion processes were a key factor in generating the second pressure peak (see Figure 11 and Figure 12) and subsequent high-frequency oscillations. This was particularly pronounced in large-angle elbows (120° and 150°), where the increased cavity volume resulted in the retention of greater volumes of unburned gas. The substantial energy released when a large volume of gas ignites downstream was directly correlated with the observed phenomenon of ‘a second pressure peak exhibiting a non-linear increase with bend angle’ (the pressure peak at a 150° bend being 2.7 times greater than that at a 30° bend). Moreover, when the elbow angle reached 90 degrees, a slight pressure fluctuation was observed prior to the second pressure peak. This fluctuation primarily arose from the interaction between the flame propagating within the elbow and the wall surfaces. When the elbow angle was larger, the interaction between the flame and the wall surfaces became more pronounced. Upon entering the elbow region, the flame front might experience a temporary reduction in propagation velocity due to the abrupt changes in the flow field, leading to a slight local pressure drop. As the flame continued propagating along the inner wall of the elbow and gradually accelerated, the local pressure rose again, thereby generating a minor pressure fluctuation. This phenomenon was closely associated with the intense lateral pressure gradient present at the elbow inlet. This pressure gradient induced significant separation of the main flow, forming a large-scale cavity on the outer wall of the bend and generating a reverse pressure gradient upstream. This reverse gradient exerted an instantaneous braking effect on the arriving flame front, causing flame deceleration and a slight local pressure drop, manifesting as the trough within the fluctuation. Subsequently, the flame accelerated along the inner wall under centrifugal force. It violently consumed the unburned gases drawn into the main flow cavity, thereby causing the pressure to rebound rapidly and form a peak within the wave.

Figure 12.

Simulation results comparing the peak explosion overpressure of elbows at different angles.

5. Conclusions

An integrated experimental and numerical simulation approach is used to investigate the key mechanism of hydrogen-propane mixture explosion in a continuous elbow structure (“Z” pipe), which provides a new mechanistic insight into the inherent coupling and cumulative effects of a continuous elbow system, beyond the understanding achieved by single elbow analysis. The simulation results clearly reveal the dual influence mechanism of the continuous elbow structure on the flame propagation characteristics and the development of explosion overpressure.

In terms of flame propagation, the cumulative “cavity effect” was clarified: the unfilled gas cavity generated by the first elbow continuously affects the middle section of the pipe and significantly regulates the interaction between the flame and the second elbow. This phenomenon fills the gap in single-elbow research. In terms of explosion overpressure, a unique three-stage flame propagation mode (development, disturbance and cavity-dominated suppression) was revealed, and a quantitative analysis was conducted on the significant suppression effect of large-angle elbows on flame oscillation. It is worth noting that the second peak of overpressure increases nonlinearly with the Angle of the elbow. The mechanism is directly related to the reflection of the pressure wave and the energy focusing effect of the amplified cavity in the large-angle elbow. By analyzing the coupling effect law of the geometric parameters of continuous elbow pipes and turbulent combustion, it provides an important design basis and risk assessment method for the safe transportation of clean energy such as hydrogen energy in complex pipeline networks, which has direct guiding significance for optimizing the explosion-proof structure of pipelines and reducing the risk of explosion disasters.

Based on existing research, in the future, the trade-off relationship between flame velocity suppression and overpressure enhancement within a smaller Angle range (such as 100–140°) can be systematically studied to determine the potential “optimal” bending Angle, thereby minimizing the overall explosion risk to the greatest extent. In addition, the universality of the determined cumulative effect can be verified by testing different hydrogen-propane ratios and hydrogen-methane mixtures, and the role of basic fuel characteristics in regulating these complex dynamic processes can be clarified.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.W. and Y.W.; methodology, X.W. and B.H.; validation, X.W., Y.H. and Y.Y.; formal analysis, X.W., X.S. and M.L.; writing—original draft, X.W.; writing—review and editing, X.W. and J.G.; resources, J.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Basic Public Welfare Research Project of Zhejiang Province, grant number LGF22E040002.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Bin Hao was employed by Sinochem Emergency Technical Service Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Jia, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, R.R.; Li, Z.; Wang, S.; Wang, F.; Fang, K. Multi-Objective Energy Planning for China’s Dual Carbon Goals. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 34, 552–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain Bhuiyan, M.M.; Siddique, Z. Hydrogen as an Alternative Fuel: A Comprehensive Review of Challenges and Opportunities in Production, Storage, and Transportation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 102, 1026–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhong, R.; Wei, C.; Zhu, B. Hydrogen Energy Development in China: Potential Assessment and Policy Implications. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 49, 659–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Hao, Y.; Ali, K.; Hua, Q.; Sun, L. Techno-Economic Analysis of Hydrogen Pipeline Network in China Based on Levelized Cost of Transportation. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 301, 118025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovač, A.; Paranos, M.; Marciuš, D. Hydrogen in Energy Transition: A Review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 10016–10035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tountas, A.A.; Ozin, G.A.; Sain, M.M. Choosing a Liquid Hydrogen Carrier for Sustainable Transportation. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2024, 8, 5181–5194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Fu, G.; Liao, Q.; Tu, R.; Zhang, H.; Liang, Y. Large-Scale Hydrogen Supply Chain Vision with Blended Pipeline Transportation of China. Renew. Energy 2025, 240, 122230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lullo, G.; Giwa, T.; Okunlola, A.; Davis, M.; Mehedi, T.; Oni, A.O.; Kumar, A. Large-Scale Long-Distance Land-Based Hydrogen Transportation Systems: A Comparative Techno-Economic and Greenhouse Gas Emission Assessment. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 35293–35319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, H.; Yu, Y.; Wan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, T. Levelized Cost of Long-Distance Large-Scale Transportation of Hydrogen in China. Energy 2024, 310, 133201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-S.; Cherif, A.; Yoon, H.-J.; Seo, S.-K.; Bae, J.-E.; Shin, H.-J.; Lee, C.; Kwon, H.; Lee, C.-J. Large-Scale Overseas Transportation of Hydrogen: Comparative Techno-Economic and Environmental Investigation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 165, 112556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, A.; Larsson, I.A.S.; Ljung, A.-L.; Forslund, T.; Andersson, R.; Sundström, J.; Lundström, T.S. Evaluating Hydrogen Gas Transport in Pipelines: Current State of Numerical and Experimental Methodologies. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 67, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Cheng, Y.F. Hydrogen Pipelines and Embrittlement in Gaseous Environments: An up-to-Date Review. Appl. Energy 2025, 387, 125636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Farhat, Z.N.; Alam, T.; Islam, M.A. Assessing Hydrogen Embrittlement in Pipeline Steels for Natural Gas-Hydrogen Blends: Implications for Existing Infrastructure. Solids 2024, 5, 375–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappes, M.A.; Perez, T. Hydrogen Blending in Existing Natural Gas Transmission Pipelines: A Review of Hydrogen Embrittlement, Governing Codes, and Life Prediction Methods. Corros. Rev. 2023, 41, 319–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najjar, Y.S.; S, M. Hydrogen Leakage Sensing and Control: (Review). Biomed. J. Sci. Tech. Res. 2019, 21, 16228–16240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardozo Soares Amaral, P.; Oh, C.B.; Do, K.H.; Choi, B.-I. Risk Assessment of Hydrogen Leakage and Explosion in a Liquid Hydrogen Facility Using Computational Analysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 91, 950–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wierzba, I.; Kilchyk, V. Flammability Limits of Hydrogen–Carbon Monoxide Mixtures at Moderately Elevated Temperatures. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2001, 26, 639–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, C.G.; Forest, T.W. Effect of Hydrogen Addition on the Performance of Methane-Fueled Vehicles. Part I: Effect on S.I. Engine Performance. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2001, 26, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houf, W.; Schefer, R.; Evans, G.; Merilo, E.; Groethe, M. Evaluation of Barrier Walls for Mitigation of Unintended Releases of Hydrogen. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 4758–4775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramamurthi, K.; Bhadraiah, K.; Murthy, S.S. Formation of Flammable Hydrogen–Air Clouds from Hydrogen Leakage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2009, 34, 8428–8437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, L.; Luo, Z.-M.; Wang, T.; Deng, J. Flame Propagation Characteristics of Non-Uniform Premixed Hydrogen-Air Mixtures Explosion in a Pipeline. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 88, 462–476. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Y.; Chen, X. Flame Propagation of Premixed Hydrogen-Air Explosion in a Closed Duct with Obstacles. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 2684–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, D.; Yin, J.; Liu, L.; Shu, C.-M. Experimental Study on Explosion Characteristics of Hydrogen–Propane Mixtures. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 22712–22718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Scribano, G. Effects of Hydrogen Addition on the Laminar Premixed Flames and Emissions of Methane and Propane. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 53, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Masoumi, S.; Ashjaee, M.; Houshfar, E. Laminar Flame Stability Analysis of Ammonia-Methane and Ammonia-Hydrogen Dual-Fuel Combustion. Fuel 2024, 363, 131041. [Google Scholar]

- Kazemi, M.; Brennan, S.; Molkov, V. Hydrogen-Methane Blends: Critical Diameters and Flame Stability Curves for Non-Premixed Turbulent Flames. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 105, 693–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, M.; Brennan, S.; Molkov, V. Numerical Simulations of the Critical Diameter and Flame Stability for Hydrogen Flames. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 59, 591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q.; Wei, J.; Yang, W.; E, J. Study on Combustion Characteristic of Premixed H2/C3H8/Air and Working Performance in the Micro Combustor with Block. Fuel 2022, 318, 123676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Gao, Y.; Sun, C.; He, P.; Liu, Y.; Tao, C.; Gao, W. Morphological Characteristics of Propane–Hydrogen Diffusion Flame: Experiments and Correlations. Combust. Sci. Technol. 2025, 197, 3577–3595. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chu, Z.; Yu, C.; Fu, G.; Xu, J.; Zhou, W.; Zhao, H.; Yu, Y.; et al. Experimental Investigation on Vented Hydrogen Explosion in Synergetic Application of Hydrogen Concentration and Pipe Length. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 123, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaathaug, A.V.; Vaagsaether, K.; Bjerketvedt, D. Experimental and Numerical Investigation of DDT in Hydrogen–Air behind a Single Obstacle. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 17606–17615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhang, Q.; Ma, Q.; Shen, S. Comparison of Explosion Characteristics between Hydrogen/Air and Methane/Air at the Stoichiometric Concentrations. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 8761–8768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, J. Numerical Analysis on Propagation Characteristics of Methane/Air Explosion in Elbow Pipe and Pipe Network. Int. J. Numer. Methods Heat Fluid Flow 2014, 24, 1610–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutabaa, M.; Helin, L.; Mompean, G.; Thais, L. Numerical Study of Dean Vortices in Developing Newtonian and Viscoelastic Flows through a Curved Duct of Square Cross-Section. Comptes Rendus Mécanique 2008, 337, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalpakli, A.; Örlü, R.; Alfredsson, P.H. Vortical Patterns in Turbulent Flow Downstream a 90° Curved Pipe at High Womersley Numbers. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 2013, 44, 692–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciccarelli, G.; Dorofeev, S. Flame Acceleration and Transition to Detonation in Ducts. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2008, 34, 499–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipatnikov, A.N.; Sabelnikov, V.A. Karlovitz Numbers and Premixed Turbulent Combustion Regimes for Complex-Chemistry Flames. Energies 2022, 15, 5840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabelnikov, V.A.; Lipatnikov, A.N. Bifractal Nature of Turbulent Reaction Waves at High Damköhler and Karlovitz Numbers. Phys. Fluids 2020, 32, 095118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Jing, G.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Y. Research on Gas Explosion Pressure and Flame Propagation Characteristics in Turning Pipelines. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 43203–43210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Jing, J.; Chen, C.; He, L. Physics of Pressurized Hydrogen Spontaneous Ignition in Pipes Containing Bends of Different Angles. Front. Energy Res. 2024, 12, 1383759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Shuai, J.; Zhou, N.; Ren, W.; Ren, F. Flame Propagation of Premixed Hydrogen-Air Explosions in Bend Pipes. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2022, 77, 104790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Wang, X.; Sun, H.; Zhu, X.; Zhao, J.; Fan, H.; Liu, Y. Large-Eddy Simulation and Experimental Study on Effects of Single-Dual Sparks Positions on Vented Explosions in a Channel. Fuel 2022, 322, 124282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, H. Machine Learning Assisted Modeling of Mixing Timescale for LES/PDF of High-Karlovitz Turbulent Premixed Combustion. Combust. Flame 2022, 238, 111895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Malalasekera, W.; Ibrahim, S. Numerical Study of Vented Hydrogen Explosions in a Small Scale Obstructed Chamber. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 16667–16683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Xiu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Q.; Li, M. Simulation of Obstacle Spacing Effects on Premixed Hydrogen-Air Explosion Dynamics in Semi-Confined Spaces. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 105, 735–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlette, F.; Meneveau, C.; Veynante, D. A Power-Law Flame Wrinkling Model for LES of Premixed Turbulent Combustion Part I: Non-Dynamic Formulation and Initial Tests. Combust. Flame 2002, 131, 159–180. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, Z.; Ma, H.; Li, C. Influence of Change in Obstacle Blocking Rate Gradient on LPG Explosion Behavior. Arab. J. Chem. 2023, 16, 104496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Ai, B.; Hao, B.; Guo, B.; Hong, B.; Jiang, X. Effect of Obstacles Gradient Arrangement on Non-Uniformly Distributed LPG–Air Premixed Gas Deflagration. Energies 2022, 15, 6872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimont, V.L. Gas Premixed Combustion at High Turbulence. Turbulent Flame Closure Combustion Model. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2000, 21, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Gao, J.; Hao, B.; Ai, B.; Hong, B.; Jiang, X. Experimental and Numerical Study on the Explosion Dynamics of the Non-Uniform Liquefied Petroleum Gas and Air Mixture in a Channel with Mixed Obstacles. Energies 2022, 15, 7999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Gao, J.; Hao, B.; Ai, B.; Han, Y.; Wu, Y.; Guo, B. Study on the LES of Premixed Gas Flame Dynamics in a Weak Confinement Structure: The Influence of Continuous Obstacle Plates. J. Appl. Fluid Mech. 2025, 18, 864–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Huang, Z.; Jin, C.; He, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Miao, H. Laminar Burning Velocities and Combustion Characteristics of Propane–Hydrogen–Air Premixed Flames. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2008, 33, 4906–4914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilly, D.K. A Proposed Modification of the Germano Subgrid-Scale Closure Method. Phys. Fluids A Fluid Dyn. 1992, 4, 633–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William, S. The Viscosity of Gases and Molecular Force. Lond. Edinb. Dublin Philos. Mag. J. Sci. 1893, 36, 507–531. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zheng, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, S.; Tang, S.; Xu, M. Effect of Initial Pressure on Hydrogen/Propane/Air Flames in a Closed Duct. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 64, 947–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponizy, B.; Leyer, J.C. Flame Dynamics in a Vented Vessel Connected to a Duct: 1. Mechanism of Vessel-Duct Interaction. Combust. Flame 1999, 116, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Li, B.; Gao, K. Pressure Characteristics during Vented Explosion of Ethylene-Air Mixtures in a Square Vessel. Energy 2018, 151, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakandu, B.M.; Andrews, G.E.; Phylaktou, H.N. Vent Burst Pressure Effects on Vented Gas Explosion Reduced Pressure. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2015, 36, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Pan, Z. Morphing Flames and Localized Hot Spots: Unlocking the Dynamics of Deflagration-to-Detonation Transition in Curved Channels. Combust. Flame 2025, 276, 114169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).