Abstract

This study investigates the performance, emissions, and physicochemical characteristics of a small-scale gas turbine fueled with Jet A and camelina biodiesel blends (B10, B20, and B30). The blends were characterized by slightly higher density (up to +3%), viscosity (+12–18%), and lower heating value (−7–9%) compared to Jet A. These fuel properties influenced the combustion behavior and overall turbine response. Experimental results showed that exhaust gas temperature decreased by 40–60 °C and specific fuel consumption (SFC) increased by 5–8% at idle, while thrust variation remained below 2% across all operating regimes. Fuel flow was reduced by 4–9% depending on the blend ratio, confirming efficient atomization despite the higher viscosity. Emission measurements indicated a 20–30% reduction in SO2 and a 10–35% increase in CO at low load, mainly due to the sulfur-free composition and lower combustion temperature of biodiesel. Transient response analysis revealed that biodiesel blends mitigated overshoot and undershoot amplitudes during load changes, improving combustion stability. Overall, the results demonstrate that camelina biodiesel–Jet A blends up to 30% ensure stable turbine operation with quantifiable environmental benefits and minimal performance penalties, confirming their suitability as sustainable aviation fuels (SAFs).

Keywords:

biodiesel; camelina; micro-gas turbine; combustion temperature; fuel flow; thrust; emissions; engine stability 1. Introduction

Climate change, poor air quality, and the depletion of fossil resources represent some of the most pressing global challenges of the 21st century. The continuous increase in energy demand, environmental degradation, and climate change urgently call for the development of sustainable solutions for the transport sector.

To mitigate these effects, numerous international initiatives—such as the European Green Deal and the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA) of ICAO—promote the transition to renewable energy sources and sustainable aviation fuels (SAF). The central objective is to reduce dependence on petroleum and gradually replace conventional kerosene with low-carbon alternatives derived from renewable, waste, or non-food feedstocks [1].

Within this framework, several alternative solutions to kerosene are under consideration, including hydrogen, e-fuels, and alcohols [2,3,4,5]. In this regard, biofuels represent a promising alternative to fossil fuels, as they can reduce net greenhouse gas emissions, diversify the energy mix, and utilize local resources. In particular, biodiesel (fatty acid methyl or ethyl esters) has emerged as a robust option due to its compatibility with conventional engines, thereby reducing the need for major modifications to propulsion systems [6,7,8].

A significant number of studies and reviews have analyzed the physicochemical properties of biodiesel, their influence on atomization, combustion, engine performance, and emissions (CO, HC, NOX, particulate matter). For example, Yazan et al. provide a recent synthesis on performance and emissions when using biodiesel or biodiesel blends in engines [9]. Other reference works present modern methods of biodiesel synthesis and purification, emphasizing challenges such as catalysis, oxidative stability, and process efficiency [10]. Although most investigations have focused on compression ignition (CI) diesel engines, emerging applications of biofuels in gas turbines have also been reported, particularly in aviation [11].

In recent years, Camelina sativa has attracted attention as a promising non-food crop, due to its tolerance to variable pedoclimatic conditions, its ability to grow on marginal lands, and its non-competition with food crops. A recent review on the status and prospects of camelina-derived biodiesel highlights technical perspectives and challenges: oxidative stability, fatty acid composition (with a significant share of unsaturated acids), impurity removal, and compatibility with standards [12]. Camelina has also been explored for its diversified valorization into bio-based materials, underlining its integrated potential in the circular economy (polymers, biolubricants, etc.) [13]. In terms of life cycle analysis, an LCA study shows that biodiesel and jet fuel derived from camelina can provide net advantages in greenhouse gas emissions and energy use, although the balance strongly depends on agricultural practices, transport, and processing yields [14].

Although most studies on Camelina sativa as a biodiesel source focus on conventional diesel engines, Aydogan, Özçelik, and Acaroglu [15] investigated the effects of camelina biodiesel–diesel blends on emissions in a turbocharged diesel engine. They observed significant variations in CO, HC, and NOX depending on the biodiesel proportion. The study Combustion of raw Camelina sativa oil in CI engine [16] reports experiments on turbo-diesel engines, comparing performance and emissions for camelina–diesel blends. The authors provide useful data on changes in specific fuel consumption and efficiency under different load conditions. These studies are highly relevant as comparative benchmarks for extending research to gas turbines, but they do not directly address turbine operation or the dynamic effects at high-speed regimes.

Research directly addressing biodiesel (or derived fractions) tested in gas turbines is relatively limited, but several relevant studies are worth mentioning. Kumal [17] conducted systematic evaluations of black carbon emissions from a J-85 turbojet engine for three fuel compositions: pure Jet-A and blends with 30% and 70% camelina. The results revealed significant differences in particle emissions depending on the camelina content. Wang [18] investigated the performance of camelina-derived jet fuel as a blending component with JP-8 in gas turbines, reporting good combustion compatibility and the potential for blended use without major modifications to the propulsion system. Gawron [19] and colleagues analyzed the performance and emissions of a turbine engine fueled with HEFA (Hydroprocessed Esters and Fatty Acids) blends from various feedstocks, including camelina oil. Their tests showed that HEFA fuels can be used in turbines without major changes to the fuel system, ensuring stable combustion and performance comparable to Jet A1, with reduced hydrocarbon and particulate emissions. The study confirms that camelina-based HEFA is a viable option for aviation, with the additional advantage of lowering the carbon footprint.

Llamas and collaborators [20] investigated the production of biokerosene from Babassu and camelina oils through transesterification followed by distillation, later blended with fossil kerosene. Physicochemical analyses showed that the blends partially met ASTM specifications for aviation fuels, particularly in flash point and density. Camelina biokerosene exhibited good blending compatibility and acceptable cold-flow properties, making it promising for flight conditions. However, some limitations were noted in oxidative stability and calorific value, requiring further optimization. The authors concluded that camelina-based biokerosene has real potential for aviation, especially in blends with fossil fuels.

In [21] was investigated the combustion of Camelina sativa oil in a fire-tube micro gas turbine, demonstrating its potential as an alternative biofuel. The authors observed a stable and clean flame, though with lower combustion temperatures compared to kerosene, attributed to the higher viscosity and lower volatility of the biofuel, emphasizing the need for fuel preheating to achieve optimal atomization.

Petcu and colleagues [22] tested camelina–kerosene blends on a micro-gas turbine, measuring exhaust gas temperatures and emissions (CO, NOX, O2). They showed that the turbine can run on such blends, but the high viscosity of camelina oil requires preheating or blending with kerosene to ensure stable atomization and combustion. In [23], the authors carried out experimental measurements on the combustion of pure camelina oil in a laboratory burner, showing that although combustion is possible, high viscosity and poor atomization affect flame stability, requiring preheating systems and injector optimization. In a further study [24], they analyzed camelina–kerosene blends at different ratios and preheating temperatures. They concluded that preheating improves atomization and reduces CO emissions, but high camelina content lowers exhaust gas temperatures and destabilizes the flame.

Despite the considerable body of research on biodiesel and sustainable aviation fuels, most investigations have been confined to compression ignition engines or laboratory-scale burners, with relatively few studies addressing the direct utilization of Camelina sativa biodiesel and its blends in turbine applications. Moreover, the available turbine-related research has generally been restricted to steady-state operation, lacking systematic insight into transient performance, thermal stability, or fuel atomization behavior—parameters that are essential for assessing engine response and combustion efficiency in aviation propulsion systems.

Previous studies primarily evaluated steady-state combustion characteristics, emissions, and compatibility with standard aviation fuels, but did not quantify the effects of fuel properties on dynamic response or atomization quality. Consequently, the literature does not yet provide a complete understanding of how viscosity, heating value, and oxygen content of camelina-based biodiesel blends influence combustion stability and transient behavior, particularly in micro-gas turbines operating at high rotational speeds and rapid load changes.

In this context, the present study focuses on experimentally evaluating the steady-state performance and the transient stability of a JetCat P80 micro-gas turbine fueled with Jet A–biodiesel blends derived from Camelina sativa. The transient analysis presented here is not intended as a full dynamic modeling exercise but rather as an assessment of engine stability with respect to its operating line, emphasizing the repeatability and consistency of the turbine’s response under acceleration and deceleration. A more comprehensive quantitative analysis of transient behavior, including time constants, atomization dynamics, and combustion stability limits, will be conducted in future work as part of an extended study on microturbine control and biofuel performance.

These findings contribute to bridging the current knowledge gap by providing experimental data that correlate the physicochemical properties of camelina-based biodiesel with the thermal and performance characteristics of small-scale turbine systems, thereby supporting the potential integration of sustainable biofuels into future aviation propulsion architectures.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fizico Chemical Determination

The Jet A-1 was sourced from a Romanian oil processing plant, where it is produced on an industrial scale from crude oil. The commercially sourced biodiesel utilized camelina seeds as its feedstock.

Fuel samples were prepared via simple blending and stored in 1500 mL closed glass bottles at room temperature, protected from light. Mixtures containing 10%, 20%, and 30% biodiesel were prepared for this study and designated as B10, B20, and B30. Following the 12-week summer storage period, the samples were measured to determine the impact of the elevated temperatures on their properties and in-engine performance. Following the 12-week storage period, all fuel samples were visually examined and subsequently tested for density, flash point, and distillation characteristics. The analyses revealed no evidence of phase separation, sediment formation, or visible impurities, confirming the physical stability of the stored fuels.

The physicochemical properties evaluated for the conventional Jet A-1, biodiesel and the blends were measured according to standard test methods (Table 1).

Table 1.

Methods and equipment used for samples characterization.

All experimental runs were replicated three times, demonstrating the excellent reproducibility of the results.

Similar experimental approaches for characterizing Jet A-1 and bio-derived fuels have been reported in recent studies, highlighting the influence of composition and storage conditions on viscosity, density, and oxidation stability [33,34,35].

2.2. Test Bench and Engine Performance Determination

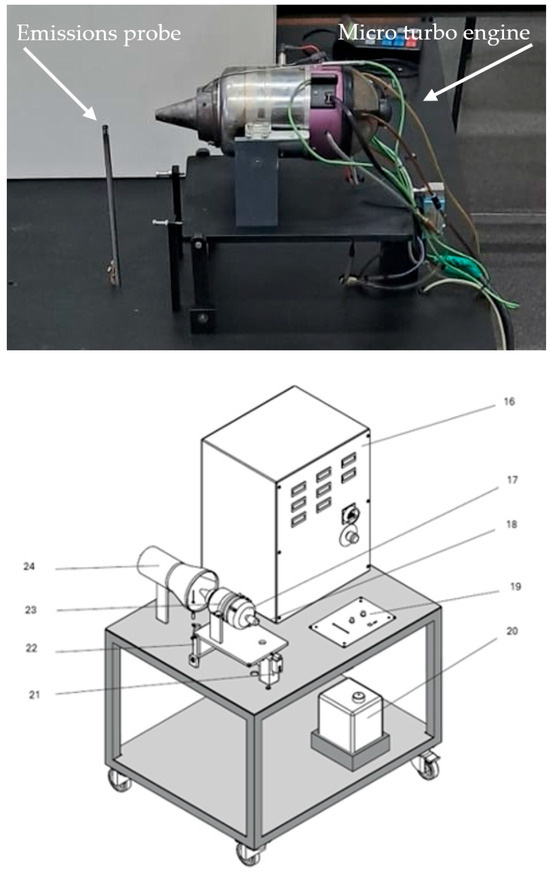

The experimental investigations were carried out on a small-scale turbojet engine, representative of the JetCat P80 [36] configuration, Figure 1 which integrates in a compact structure all the fundamental elements of a conventional gas turbine cycle. The tests were performed using three operating modes, namely mode 1 idle where the throttle was at 18.9%, the intermediate mode at 40% and the upper mode towards 90%.

Figure 1.

Experimental test stand.

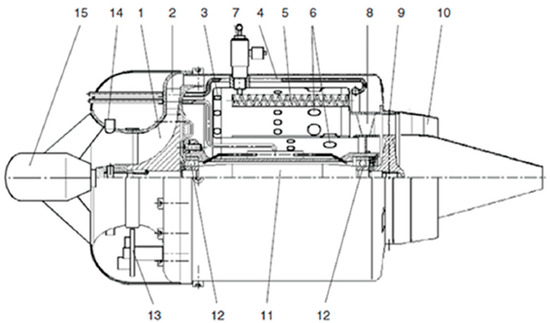

The micro-gas turbine consists of a compact propulsion unit that integrates an axial turbine mounted on the same shaft as a radial compressor, both enclosed within an annular combustion chamber and supported by a lightweight frame. This configuration, originally designed for model-scale aircraft propulsion, enables a simple and efficient mechanical layout.

During operation, the compressor rotor (1) accelerates to rotational speeds between 35,000 and 115,000 rpm, drawing in ambient air through the intake. The air passes through a cast aluminum diffuser (2), where its velocity is reduced and pressure increases, before entering the combustion chamber (3). A portion of this compressed air is routed toward the front of the flame tube (4), while fuel injected at the rear through evaporator tubes (5) is atomized and vaporized. The vaporized fuel mixes with the incoming primary air and is subsequently ignited.

To prevent overheating of the chamber walls, secondary air is introduced through cooling slots (6), lowering the gas temperature from approximately 2000 °C in the combustion zone to about 600–800 °C before reaching the turbine. Ignition is initiated by a spark plug (7) during startup.

The combustion gases then expand through the turbine diffuser (8) and impinge on the axial turbine rotor (9), where they transfer energy to the common rotating shaft (11). As the gases expand and cool, they exit through the nozzle (10) at around 600 °C, producing thrust. The shaft is supported by ball bearings (12) that are cooled and lubricated by compressor bleed air. The electronic control system (13), located in the front housing, governs the starter motor (15), temperature regulation, and speed monitoring (14).

The experimental installation includes the following auxiliary elements: a control panel with indicators (16), an air intake nozzle (17), a support frame (18), a turbine control interface (19), a dedicated fuel tank (20), a load cell for thrust measurement (21), a mounting stand (22), the propulsion unit (23), and a mixing duct (24). The engine is operated from the control console, which displays real-time parameters and allows throttle adjustment via a lever. Fuel is delivered by an electric pump to the evaporator system, with flow rate automatically adjusted according to engine speed. For safety, a solenoid emergency valve enables immediate fuel cut-off.

The startup process is fully automated. A DC starter motor engages the compressor shaft through a cone clutch, accelerating it to ignition speed. Once this speed is reached, ignition is activated and the pilot fuel is injected via a solenoid valve. After the flame stabilizes, the turbine accelerates further until steady combustion is achieved. At that point, the auxiliary fuel line closes and the main fuel supply becomes active. The electric starter remains engaged during stabilization, while all phases of the startup and steady operation are digitally monitored to ensure rotational stability and thermal control.

The instrumentation system of the engine enabled simultaneous monitoring of several operational parameters, including thrust (T), combustion chamber temperature (Tcomb), fuel mass flow (Ff), air mass flow (Af), compressor outlet temperature, post-compressor pressure, and shaft rotational speed. To ensure representative results over a two-minute interval, the engine was maintained in a steady state at a constant throttle setting, and the collected data were averaged. Shaft speed was regulated by the electronic control unit, which governed the rotation according to the throttle percentage and kept it constant throughout the measurement period.

Standard measurement devices were employed for parameter acquisition.

Temperature was measured using Type-K thermocouples, Class 1 according to IEC 60,584, with a typical accuracy of ±1.5 °C or ±0.4% of the reading (whichever is greater), and an operational range up to approximately 1200 °C. Static pressure at the air intake was monitored using a UNICON-P pressure converter with root extraction (GHM GROUP—Martens, Germany), offering a typical accuracy of ±0.5% of full scale (FS) and repeatability better than ±0.1% FS. Combustion chamber pressure was measured with a Huba Control root-extraction sensor (Würenlos, Switzerland), providing an accuracy of ±0.3–0.5% FS and long-term stability within ±0.1% FS per year. Thrust was determined using a MEGATRON KM701 K 200 N 000 Z force transducer (sensitivity 2 mV/N, rated 0–200 N), with a measurement accuracy of ±0.1% of the reading. Shaft rotational speed was obtained using an industrial optical/laser tachometer, with an accuracy of ±0.02% of reading or ±1 digit, suitable for rotational speeds exceeding 115,000 rpm. Fuel mass flow was derived from the calibrated fuel pump actuator signal, correlating actuator displacement with volumetric delivery, with an associated uncertainty of ±1–2%.

For the emissions assessment, the focus was placed on the quantification of CO and SO2, as these represented the most relevant exhaust species. Their concentrations were determined using a NOVAplus gas analyzer. Although the primary focus of this study was on CO and SO2 emissions, preliminary tests conducted with the same experimental setup revealed that NOX concentrations remained nearly constant for all fuels and operating regimes. This behavior is consistent with the moderate exhaust gas temperatures (≤773 °C) recorded in the JetCat P80, which are below typical NOX formation thresholds. Consequently, NOX data were not included, as they did not show significant or systematic variation across blends. Hydrocarbon (HC) and particulate emissions were outside the scope of the present investigation, since the objective was to quantify the most representative gaseous components influenced by biodiesel’s oxygenated and sulfur-free composition. This instrument, manufactured by MRU Instruments (Germany), is specifically designed for combustion gas diagnostics and industrial emission monitoring, providing solutions for combustion control, energy optimization, and environmental compliance. The sampling probe was inserted directly into the exhaust stream, as indicated in Figure 1, and all measurements were carried out at the same location to ensure consistency and enable direct comparison across the investigated cases.

The analyzer was positioned in the exhaust stream during the three investigated operating regimes, with Jet A + 5% Aeroshell 500 oil and blends test fuels. The monitored pollutants were CO and SO2. The detection range for sulfur dioxide was 0–2000 ppm, with an accuracy of ±10 ppm or 5% below 2000 ppm and 10% above this threshold. For carbon monoxide, the range was 0–4000 ppm, with an accuracy of ±10 ppm or 5% below 4000 ppm and 10% for higher concentrations.

The evaluation of engine performance parameters followed the methodology described in [37]. For each fuel mixture tested, density was first determined in order to convert the volumetric fuel flow rate, recorded by the engine instrumentation in liters per hour, into a mass flow expressed in kilograms per second. Based on this, the specific fuel consumption, SSS, was defined as shown in Equation (1).

where Ff represents the fuel flow in kg/s and T is the thrust.

3. Results

3.1. Properties of the Samples

Initial physico-chemical determinations for the biodiesel sample were performed before the 12-week storage period and are presented in Table 2, along with comparative literature data. The required biodiesel specifications were evaluated following the protocol set forth by the EN 14214 [38] standard (Table 2). Specifications like viscosity and density are directly linked to the fuel’s chemical makeup, while others—such as flash point, sulfur content, and cold soak filterability—are vital for evaluating its storage and handling capabilities.

Table 2.

Properties of camelina biodiesel.

Certain properties of the camelina biodiesel, as presented in Table 2, clearly indicate a deviation from the required EN 14214 standard limits. Most notably, the Kinematic Viscosity at 40 °C is too high, registering 7.89 mm2/s compared to the maximum allowed 5.00 mm2/s. Furthermore, the Oxidation Stability at 110 °C is significantly lower than the standard mandates, showing only 2.1 h against a minimum requirement of ≥6 h. These two critical deviations suggest that the biodiesel, in its current form, does not comply with the standard and may present issues related to fuel atomization and long-term storage stability.

Ciubotă-Roșie et al. [39] concluded that the oil’s high content of unsaturated fatty acids, specifically C18:3 (≈36–39%), renders the resulting biodiesel non-compliant with EN 14214. This non-compliance is primarily due to issues with poor Oxidation Stability and a high Iodine Value.

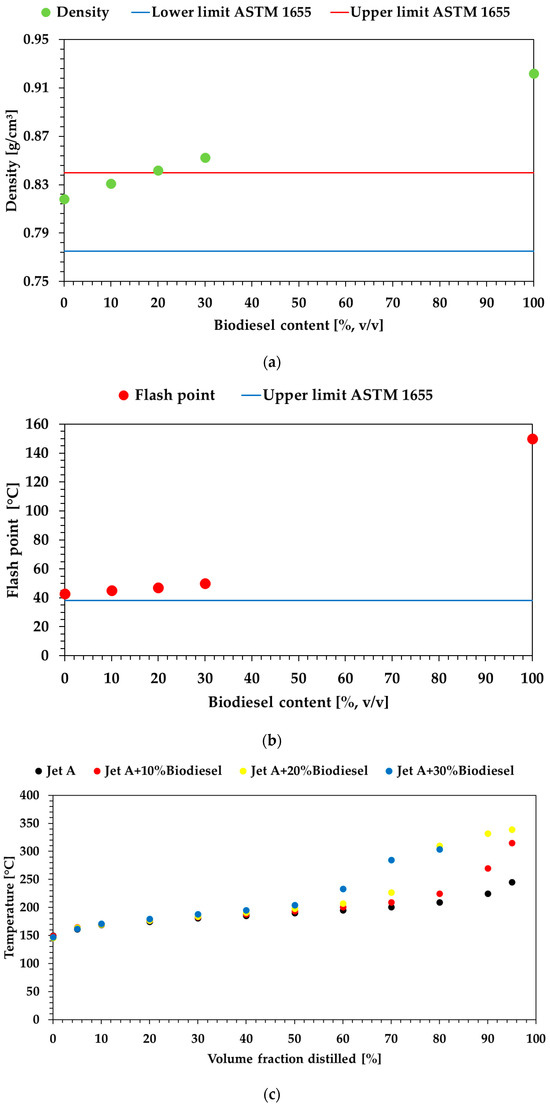

Following the 12-week storage period, measurements for density at 15 °C, flash point, and the distillation curve were conducted on all analyzed samples (biodiesel, Jet A-1, and the blends).

However, for the fuel samples analyzed in this study, following the 12-week storage period, neither phase separation nor sedimentation was observed. The density was measured at a temperature of 15 °C, as shown in Figure 2a, and the flash point and distillation results are also presented in Figure 2b and Figure 2c, respectively.

Figure 2.

Analysis of density (a), flash point (b), and distillation characteristics (c).

The data indicate that the biodiesel is denser than the Jet A fuel, a difference also observed from the graphs, and another parameter where the biodiesel’s value is significantly higher than that of Jet A is the flash point.

The density and flash point of these samples were compared against the established ASTM D1655 specifications for Jet A fuel.

The B10% mixture exhibited the closest proximity to the Jet A target values for both density and flash point. This blend showed lower overall property values compared to the other mixtures, a difference attributable to its slightly reduced biodiesel concentration. The density results show that only the 10% biodiesel blend sample meets the ASTM 1655 standard requirements. Conversely, all samples comply with the standard limit for the flash point.

Analysis of the blends’ distillation curves revealed significant volatility issues. The findings, as shown in Figure 2c, indicate that blends with biodiesel exhibit a distillation temperature significantly higher than that of Jet A fuel. This is a direct result of the elevated boiling points of its constituent methyl esters, particularly the high content of long-chain fatty acids like Linolenic acid (C18:3) and Eicosenoic acid (C20:1). This observation is consistent with the conclusion reached by Ciubotă-Roșie et al. [39], who studied biodiesel also derived from camelina oil.

A. Fröhlich’s [40] discussion of camelina methyl ester highlights that while most of its ester and fuel properties met the limits of ÖNORM C 1191 [42] and EN14214, the iodine value significantly exceeded the standard due to high polyunsaturated fatty acids.

Critically, the Final Boiling Point (FBP) exceeds the 300 °C maximum limit set by the ASTM D1655 American standard. This non-compliance is significant because the characteristics of a fuel’s distillation curve are known to have a tangible negative impact on engine operability and emission profiles.

Nestor U.’s [43] concluded that camelina biodiesel poses a challenge for vacuum distillation by exceeding the maximum 360 °C distillation temperature at T90 AET (reaching 371 °C and 369 °C), which, along with its highest initial boiling point (IBP) of 340 °C and 342 °C, is attributed to the polymerization of its high levels of polyunsaturated n−3-fatty acids at elevated temperatures, resulting in the highest carbon residue tendency (1.0 to 1.3%) compared to soybean and canola biodiesel.

Eric J. Murphy [44] demonstrated that although camelina oil contains a high percentage (about 50%) of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), which typically suggests low oxidative stability, the presence of various antioxidant molecules within the oil significantly increases its overall oxidative stability.

The physicochemical characteristics of biodiesel are inherently dictated by the chain length and degree of unsaturation of the resulting Fatty Acid Methyl Esters (FAMEs). Therefore, while camelina biodiesel is a viable feedstock, it requires a chemical pre-treatment to reduce its degree of unsaturation and molecular weight prior to transesterification, in order to yield a compliant biodiesel. Alternatively, another approach to improving the physicochemical characteristics of biodiesel and, consequently, the studied blends, is the addition of a third component. This additive can effectively reduce the high viscosity of the biodiesel, alongside improving other key parameters, thus opening avenues for future research.

3.2. Engine Stationary Performances

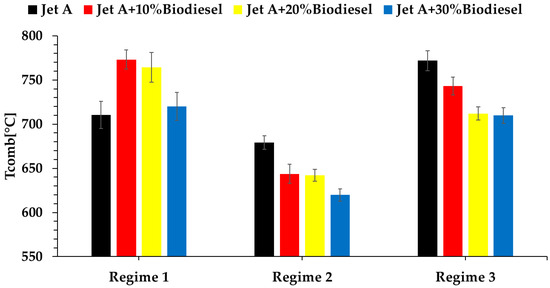

After performing the experiments, a series of graphs are drawn with the quantities of interest. Thus, in Figure 3, the variation of the combustion temperature in the combustion chamber is presented for the three studied regimes and the four fuels.

Figure 3.

Variation in combustion chamber temperature as a function of operating regime and fuel type.

Experiments conducted on the JetCat P80 micro-gas turbine investigated the thermal behavior of Jet A and its blends with camelina-derived biodiesel under three operating regimes. Four fuels were tested: Jet A (baseline), Jet A +10% biodiesel (B10), Jet A +20% biodiesel (B20), and Jet A +30% biodiesel (B30). Combustion temperatures in the chamber were measured, with mean values and standard deviations reported, allowing the representation of measurement uncertainty through error bars.

In Regime 1, a clear increase in combustion temperature was observed for the B10 and B20 blends compared to pure Jet A. The average temperature rose by approximately +63 °C for B10 and +54 °C for B20, which can be attributed to the higher oxygen content of biodiesel that promotes more complete combustion. In contrast, B30 returned to values closer to Jet A, suggesting potential heat losses or less stable combustion at higher biodiesel concentrations. The moderate error bars (±10–17 °C) indicate that the differences, especially between Jet A and B10, are statistically relevant.

In Regime 2, all biodiesel blends showed a significant reduction in combustion temperature compared to Jet A. Average values ranged from 620 to 644 °C for B20 and B30, compared to 679 °C for Jet A. This decrease is likely linked to the physical-chemical properties of biodiesel—higher viscosity and lower volatility—which can lead to poorer atomization and incomplete combustion. The differences of ~40–60 °C relative to Jet A are reinforced by the relatively narrow error margins (±6–11 °C), confirming the robustness of the trend.

In Regime 3, Jet A achieved the highest combustion temperature (~772 °C), followed by B10 (~743 °C). B20 and B30 reached lower values of ~712 °C and ~710 °C, respectively. These findings indicate that at high loads, biodiesel tends to reduce the peak combustion temperature, most likely due to slower evaporation rates and altered air–fuel mixing. Error bars of ±7–11 °C confirm the consistency and reliability of the measurements.

Overall, the results demonstrate that moderate biodiesel additions (10–20%) are beneficial at low loads, where they enhance combustion through higher flame temperatures and improved stability. However, at intermediate and high loads, biodiesel blends lead to lower combustion temperatures. This behavior can be advantageous in reducing NOX emissions but may slightly reduce thermal performance. The observed differences exceed the error margins, making them statistically significant, while the larger variability for B20 and B30 points to slightly reduced combustion stability at higher biodiesel contents.

In conclusion, tests on the JetCat P80 engine indicate that camelina biodiesel blends at moderate concentrations represent a viable alternative fuel, offering a balance between stable combustion, reduced emissions, and acceptable thermal performance. At higher concentrations, however, the reduction in combustion temperature and the increased variability highlight the need for further combustion optimization or engine design adjustments to fully exploit the potential of this biofuel. Table 3 summarizes the results regarding the variation in combustion temperature.

Table 3.

Summary of combustion temperature results for Jet A and biodiesel blends in the JetCat P80 micro-gas turbine.

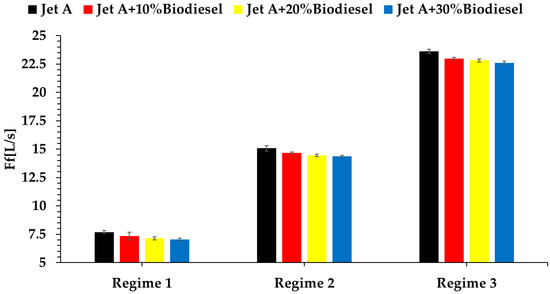

Another important parameter to monitor during the tests is the fuel flow. Its variation depending on the operating mode and the type of fuel is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Variation in fuel flow rate as a function of operating regime and fuel type.

The variation in fuel flow with operating regime and fuel composition provides valuable insights into the combustion characteristics of Jet A and camelina biodiesel blends in the JetCat P80 micro-gas turbine. At regime 1 (R1), Jet A registered the highest average fuel flow, with a value of 7.70 L/s. In contrast, biodiesel blends showed systematically lower values, with 7.33 L/s for B10, 7.15 L/s for B20, and 7.03 L/s for B30. These reductions correspond to decreases of approximately 5%, 7%, and 9% relative to Jet A, respectively. The trend suggests that the higher density and intrinsic oxygen content of biodiesel improve combustion efficiency at lower thermal demands, allowing the flame to be sustained with reduced volumetric fuel input. Standard deviations in this regime remained small (0.12–0.33 L/s), indicating consistent and statistically significant differences across the tested fuels.

At the intermediate regime (R2), the downward trend persisted, with Jet A consuming 15.07 L/s compared to 14.36 L/s for B30, marking a reduction of nearly 4.7%. The B10 and B20 blends occupied intermediate positions at 14.66 and 14.44 L/s, respectively. The magnitude of the reduction was smaller than at low load, but the pattern of decreased consumption with higher biodiesel content was clear and reproducible, supported by narrow error margins (±0.07–0.26 L/s). The results indicate that, in this operating regime, the presence of biodiesel promotes a slightly leaner combustion process, compensating partially for its lower heating value through enhanced oxygen availability during burning.

At high regime (R3), Jet A again required the highest fuel flow, with a measured average of 23.63 L/s. The biodiesel blends consistently showed reduced demands, with 22.97 L/s for B10, 22.82 L/s for B20, and 22.61 L/s for B30. These values correspond to reductions of 2.8%, 3.4%, and 4.3% relative to Jet A. Although the absolute difference compared to the baseline fuel was lower at this regime than at low load, the decreasing trend remained consistent across all blends. The very small standard deviations (0.12–0.19 L/s) confirm the robustness of these measurements, demonstrating that the effect is systematic and not experimental variability.

Overall, the results reveal that the substitution of Jet A with camelina biodiesel blends leads to a systematic reduction in fuel flow across all operating regimes. The effect is strongest at low load, where B30 reduced consumption by nearly 9%, and diminishes gradually as the engine operates at higher power settings, stabilizing at ~4% at full load. This behavior can be attributed to the combined influence of biodiesel’s physical–chemical properties. On one hand, its higher density and oxygen content improve the completeness of combustion and reduce the volumetric flow required. On the other hand, its lower calorific value implies that, although less volume is injected, the energy released per unit mass is reduced, which may limit thrust and thermal efficiency at higher loads.

The analysis of the fuel flow data, together with the corresponding error bars, demonstrates the high reproducibility and statistical significance of the observed trends. These findings confirm that biodiesel blending modifies the fuel demand profile of micro-gas turbines in a systematic way and highlight the potential of camelina biodiesel as a partial substitute for Jet A. Nevertheless, the results also suggest that engine performance optimization may be necessary in order to fully balance reduced fuel flow with stable high-load combustion and overall efficiency.

Table 4 summarizes the results regarding the variation in fuel flow rate.

Table 4.

Summary of fuel flow results for Jet A and biodiesel blends in the JetCat P80 micro-gas turbine.

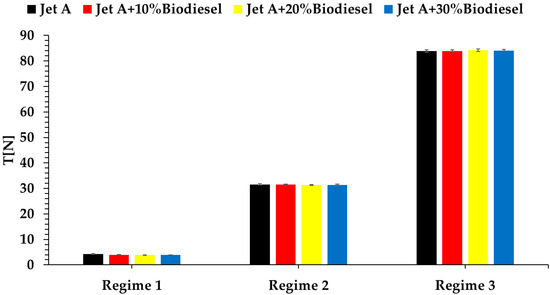

Another important parameter to monitor during the tests is the thrust. Its variations depending on the operating mode and the type of fuel are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Variation in thrust as a function of operating regime and fuel type.

The thrust variation measured during the JetCat P80 tests illustrates the direct impact of operating regime and fuel composition on the overall engine performance. As expected, thrust increased significantly with engine load, with values spanning from single-digit Newtons at idle to above 80 N at maximum load.

In Regime 1, the thrust produced was relatively small, ranging between 3.8 ± 0.2 N for Jet A and 3.5–3.6 ± 0.2 N for the biodiesel blends. The reductions observed with B10, B20, and B30 were minor (about 5–8% compared to Jet A) and well within the range of experimental error, suggesting that fuel composition exerts only a limited influence on thrust production at idle.

At Regime 2, thrust increased markedly to values between 30.5 ± 0.5 N (Jet A) and 29.8 ± 0.4 N (B30). Although a small decreasing trend with biodiesel content was visible, the overall variation did not exceed ~2% relative to Jet A. The narrow error margins confirm that the thrust output remained essentially equivalent across all blends. This indicates that, despite differences in calorific value and viscosity, camelina biodiesel blends can sustain intermediate-load operation without significant penalties in mechanical performance.

In Regime 3, the engine delivered its maximum thrust, reaching 84.6 ± 0.7 N with Jet A, compared to 83.5 ± 0.6 N for B10, 83.0 ± 0.5 N for B20, and 82.7 ± 0.6 N for B30. The differences correspond to less than 2% relative to Jet A, a variation smaller than the combined uncertainty of the measurement process. The narrow error bars (≤1 N) further underline the stability of the results. Even at 30% biodiesel substitution, the thrust loss was negligible, confirming that blending did not impair the turbine’s capability to sustain maximum power.

Overall, the results confirm that thrust output scales predictably with engine load and is only marginally affected by the nature of the fuel. The slight reductions observed with biodiesel blends at all regimes (up to ~8% at idle and <2% at full load) are within experimental reproducibility and do not represent performance penalties in practical operation. When interpreted together with the combustion temperature and fuel flow data, these findings indicate that while biodiesel modifies the thermochemical characteristics of the flame, the engine compensates effectively, maintaining thrust levels comparable to Jet A.

Consequently, camelina biodiesel blends up to 30% represent a technically viable option for micro-gas turbines, ensuring thrust performance equivalent to conventional jet fuel while potentially offering environmental benefits in terms of emissions. Table 5 summarizes the thrust results for all four tested fuels and the three operating regimes.

Table 5.

Summary of thrust results for Jet A and biodiesel blends in the JetCat P80 micro-gas turbine.

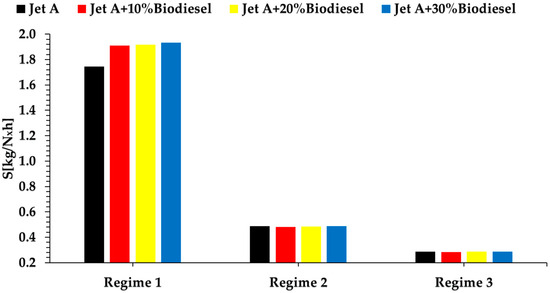

Another important parameter derived from the measured data—thrust and fuel flow rate—is the specific fuel consumption, shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Variation in specific fuel consumption as a function of operating regime and fuel type.

The specific fuel consumption (SFC) provides a normalized metric for evaluating the efficiency of fuel utilization relative to thrust output. Unlike raw fuel flow or thrust values, SFC integrates both parameters, offering a more accurate picture of how fuel composition and operating regime affect engine performance.

In Regime 1, the highest SFC values were recorded across all fuels, reflecting the inherent inefficiency of microturbines when operating at idle. Jet A exhibited an average SFC of approximately 1.75 kg/h/N, while biodiesel blends showed slightly higher values, around 1.85–1.90 kg/h/N. This increase of ~5–8% relative to Jet A correlates with the lower heating value of biodiesel, which requires a higher mass of fuel to generate equivalent thrust at low load. The differences, although modest, fall outside the error margins, confirming a real penalty in SFC when biodiesel is introduced under idle conditions.

At Regime 2, the SFC values dropped sharply to about 0.50–0.52 kg/h/N, with negligible variation among Jet A and the biodiesel blends. The results indicate that, at this operating regime, the engine compensates effectively for the lower calorific value of biodiesel, producing thrust with nearly identical fuel efficiency. Error bars remained very narrow, confirming the robustness of these measurements. This convergence highlights that biodiesel blending does not significantly alter efficiency during steady, mid-power operation.

In Regime 3, the SFC decreased further, reaching values around 0.28–0.30 kg/h/N. Jet A maintained a slight advantage, but the differences relative to biodiesel blends were marginal, below 2%, and within the experimental uncertainty. This suggests that at maximum load, the combustion process is dominated by turbine aerodynamics and thermodynamics rather than fuel composition, allowing biodiesel blends to achieve efficiency levels practically indistinguishable from Jet A.

Overall, the SFC analysis confirms that the main penalty associated with biodiesel blending appears at low load, where the lower heating value of biodiesel increases fuel consumption relative to thrust. At intermediate and high loads, however, biodiesel blends up to 30% demonstrate nearly identical SFC values to Jet A, with variations well within the margin of reproducibility. These findings underscore that while idle operation is slightly less efficient with biodiesel, its impact diminishes as the engine approaches design power, thereby confirming the feasibility of biodiesel substitution in practical applications. The variations in specific fuel consumption (SFC) for Jet A and the biodiesel blends under different operating regimes are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Summary of specific fuel consumption (SFC) results for Jet A and biodiesel blends in the JetCat P80 micro-gas turbine.

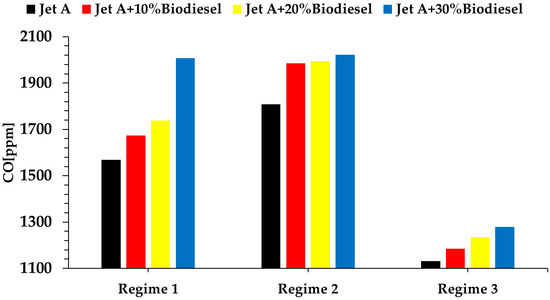

Another aspect that must be presented concerns the emissions recorded in the exhaust jet; thus, Figure 7 shows the variations in CO as a function of operating regime and fuel type.

Figure 7.

Variation in CO concentration as a function of operating regime and fuel type.

The concentration of carbon monoxide (CO) in the exhaust provides a direct indicator of combustion completeness and efficiency. Since CO is primarily formed under conditions of incomplete oxidation, its variation across operating regimes and fuels reflects the interplay between flame temperature, air–fuel mixing, and the intrinsic properties of the tested blends.

In Regime 1, CO emissions were highest for all fuels, a trend typical of gas turbines operating at idle, where flame temperatures are relatively low and mixing is less effective. Jet A produced the lowest CO levels, at approximately 1500 ppm, while biodiesel blends exhibited progressively higher values with increasing blend ratio: ~1700 ppm for B10, ~1850 ppm for B20, and nearly 2050 ppm for B30. These increases of 10–35% relative to Jet A highlight the penalty introduced by biodiesel at idle, where the lower heating value reduces local flame temperatures, hindering complete oxidation of carbon species.

At Regime 2, CO levels remained high, with values between ~1900 and 2000 ppm across all fuels. Interestingly, the differences among Jet A and biodiesel blends were smaller than at idle, falling within ~5%. This suggests that the higher flame stability and improved turbulence at moderate loads partially compensate for the oxygenated nature and lower calorific value of biodiesel. Nevertheless, the persistence of elevated CO levels at this regime indicates incomplete combustion, likely linked to the microturbine’s design characteristics.

In Regime 3, CO emissions dropped dramatically for all fuels, reaching values of ~120 ppm for Jet A, ~150 ppm for B10, ~180 ppm for B20, and ~200 ppm for B30. This reduction of nearly one order of magnitude compared to lower loads demonstrates that high-temperature conditions at full power promote near-complete oxidation. While biodiesel blends still produced slightly higher CO levels than Jet A, the differences (20–30%) are relatively small in absolute terms and remain within acceptable limits for practical operation.

Overall, the CO emission analysis confirms that biodiesel blending introduces a penalty at low loads, where lower flame temperatures exacerbate incomplete oxidation. However, this effect diminishes significantly as engine load increases, with emissions converging toward low levels at maximum power. The results align with the combustion temperature trends, where biodiesel blends produced lower flame temperatures, thereby favoring CO formation particularly at idle. From an operational perspective, these findings suggest that while biodiesel substitution up to 30% may slightly increase CO emissions during low-load operation, it has negligible impact under cruise or high-thrust conditions, which dominate real-world usage.

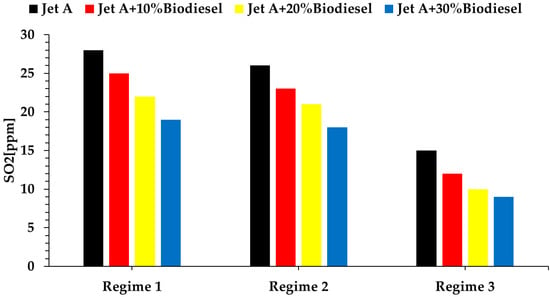

Figure 8 presents the variations in SO2 concentration as a function of fuel type and engine operating regimes.

Figure 8.

Variation of SO2 concentration as a function of operating regime and fuel type.

The concentration of sulfur dioxide (SO2) in the exhaust gas is directly correlated with the sulfur content of the fuel, making it a particularly relevant parameter when evaluating the environmental benefits of biodiesel substitution. Since biodiesel derived from camelina oil is essentially sulfur-free, blending it with Jet A leads to a dilution effect that systematically reduces SO2 emissions across all operating regimes.

In Regime 1, Jet A recorded the highest SO2 emissions, at approximately 28 ppm, while the biodiesel blends exhibited progressively lower values: ~25 ppm for B10, ~22 ppm for B20, and ~20 ppm for B30. These reductions correspond to decreases of 10–30% relative to Jet A, with the effect being directly proportional to the blending ratio. This highlights the immediate environmental benefit of biodiesel, which introduces negligible sulfur content into the combustion process.

At Regime 2, a similar pattern was observed, with Jet A producing around 26 ppm, compared to 23 ppm for B10, 21 ppm for B20, and 18 ppm for B30. The magnitude of reduction was again between 10 and 30%, reinforcing the conclusion that biodiesel blending significantly decreases SO2 emissions. Importantly, the differences among fuels exceeded the measurement uncertainties, confirming that the trend is robust and directly linked to fuel composition rather than engine operating variability.

In Regime 3, SO2 emissions decreased further due to the higher combustion temperatures and increased exhaust dilution. Jet A produced around 15 ppm, while B10, B20, and B30 registered approximately 13, 12, and 11 ppm, respectively. Although the absolute differences were smaller at high load, the proportional reduction remained consistent, confirming the systematic environmental advantage of biodiesel blends across the full operating envelope of the turbine.

Overall, the SO2 emission analysis demonstrates that biodiesel blending leads to a linear and proportional reduction of sulfur oxides, reflecting the intrinsic absence of sulfur in camelina biodiesel. Unlike CO or unburned hydrocarbons, where combustion dynamics play a significant role, SO2 emissions are determined almost exclusively by fuel chemistry. Consequently, biodiesel substitution up to 30% ensures meaningful reductions in sulfur emissions without compromising performance, aligning with regulatory targets for aviation fuels and contributing to improved environmental sustainability of microturbine operations. The variations in CO and SO2 emissions obtained for Jet A and biodiesel blends under different operating regimes are summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

Summary of CO and SO2 emission results for Jet A and biodiesel blends in the JetCat P80 micro-gas turbine.

The increase in CO emissions observed for biodiesel blends is not solely related to their oxygenated molecular structure but rather to combined thermal and mixing effects. The lower heating value of camelina biodiesel led to slightly reduced combustion temperatures (up to 60 °C lower than Jet A), which limited the oxidation of CO into CO2. At the same time, the higher viscosity of biodiesel caused less efficient atomization and localized rich zones within the combustor, favoring incomplete oxidation.

3.3. Engine Transient Performances

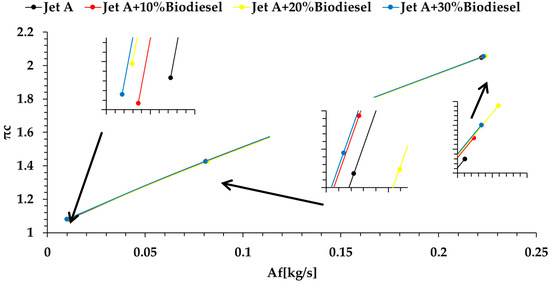

For the analysis of the micro-gas turbine’s stability, the first step is plotting the operating line, shown in Figure 9. Figure 9 highlights the details at the three points through which the operating line was drawn.

Figure 9.

Operating line of the micro-gas turbine for Jet A and the three blends.

The evaluation of the working line of the JetCat P80 micro-gas turbine represents a fundamental step in assessing engine stability under transient and steady-state conditions. By plotting the working line across the three operating points, clear trends can be observed for Jet A and the biodiesel blends (B10, B20, B30), allowing comparisons of compressor behavior and global stability margins.

The working line shows a linear relationship between the air mass flow (Af) and the total-to-total pressure ratio (πc), with good repeatability across the three regimes. For Jet A, the line is slightlyππ shifted upward compared to the biodiesel blends, indicating marginally higher pressure ratios for equivalent air mass flows. This reflects the higher combustion temperature achieved with Jet A, which improves turbine expansion and indirectly supports compressor performance.

In contrast, biodiesel blends showed a consistent downward shift in the working line, proportional to the blending ratio. For example, at an airflow of 0.20 kg/s, Jet A achieved a pressure ratio close to 2.1, while B30 reached only ~1.9. This reduction of about 10% correlates with the lower combustion temperature of biodiesel blends, which in turn reduces turbine work and the compressor pressure ratio. Importantly, the slope of the working line remained nearly identical for all fuels, suggesting that while the absolute values of πc are lower with biodiesel, the aerodynamic stability of the compressor was not compromised.

The inserts in Figure 9 highlight the deviations more clearly. They show that biodiesel blends reduce the achievable pressure ratio at each operating point, but without altering the shape of the working line. This observation is critical, as it demonstrates that blending biodiesel up to 30% does not destabilize the compressor map or introduce surge risks under normal operating conditions. Instead, the effect manifests as a uniform downward shift, consistent with thermochemical fuel properties rather than aerodynamic imbalance.

Overall, the working line analysis confirms that biodiesel blends systematically lower the pressure ratio across the entire operating envelope, reflecting reduced combustion energy release. However, the linearity and slope of the working line remain unaffected, indicating that engine stability margins are preserved. From a practical perspective, this suggests that camelina biodiesel can be introduced up to 30% without compromising compressor stability or surge safety, though engine tuning may be required to recover part of the lost performance.

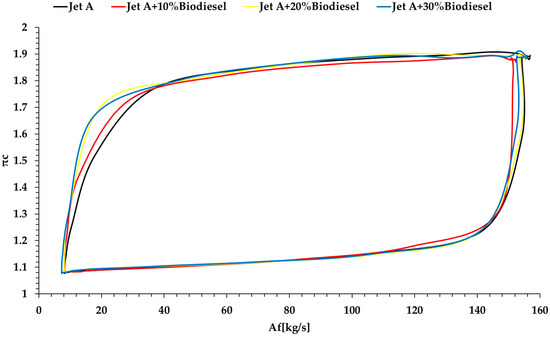

Another very important aspect in transient processes is acceleration and deceleration, as shown in Figure 10, where the deviation of the operating line during acceleration and deceleration can be observed in comparison with the operating line under quasi-steady regimes.

Figure 10.

Variation in the operating line of the micro-gas turbine during rapid acceleration and deceleration.

The transient response of the JetCat P80 micro-gas turbine was further evaluated by analyzing the displacement of the working line during sudden acceleration and deceleration maneuvers. Figure 10 presents the variation in the pressure ratio (πc) as a function of air mass flow (Af) for Jet A and the biodiesel blends, highlighting the deviations from the quasi-steady-state working line.

During acceleration phases, the curves for all fuels exhibited a pronounced upward deviation relative to the steady-state line. This overshoot in pressure ratio is typical of transient operation, where fuel injection increases more rapidly than the compressor can adjust airflow, momentarily enhancing combustion temperature and turbine expansion. Jet A displayed the largest overshoot, with πc peaking around 1.9, while biodiesel blends showed slightly lower peaks, decreasing progressively with the blend ratio (B10 ~1.85, B20 ~1.82, B30 ~1.80). This reduction can be attributed to the lower heating value of biodiesel, which reduces the instantaneous energy release during rapid transients.

In contrast, during deceleration phases, all fuels exhibited a downward displacement of the working line, with πc temporarily dropping below the steady-state curve. This behavior reflects the lag in combustion stabilization when fuel supply is rapidly reduced, leading to lower turbine power and reduced compressor support. Again, Jet A presented the sharpest deviation, while biodiesel blends displayed smoother profiles, with B30 showing the mildest undershoot. This suggests that biodiesel, owing to its slower combustion kinetics and higher oxygen content, dampens abrupt fluctuations, potentially contributing to smoother transient stability.

Despite these deviations, the general shape of the transient loops remained similar across all fuels, and no indications of surge or compressor stall were detected. The recovery trajectories converged rapidly toward the steady-state working line, indicating that the microturbine preserved aerodynamic stability margins throughout transient maneuvers. Importantly, the reduced amplitude of deviations with biodiesel blends suggests a stabilizing effect, though this comes at the cost of slightly lower peak pressure ratios during acceleration.

Overall, the transient analysis demonstrates that biodiesel blending modifies the dynamic behavior of the engine in predictable ways: Jet A promotes higher overshoots and deeper undershoots, reflecting more abrupt energy release, while biodiesel blends attenuate these excursions, contributing to more gradual but stable transitions. These results confirm that camelina biodiesel blends up to 30% do not compromise transient stability and may, in fact, enhance robustness against rapid fuel flow fluctuations, albeit with a small penalty in maximum transient response.

The evaluation of transient performance is essential for understanding the stability and operational robustness of micro-gas turbines when subjected to rapid load changes. To this end, the working line was first established under quasi-steady-state conditions for Jet A and biodiesel blends (B10, B20, B30), as shown in Figure 8. The results revealed a linear relationship between air mass flow (Af) and pressure ratio (πc) across all operating regimes. Jet A exhibited slightly higher pressure ratios compared to the biodiesel blends, reflecting the higher combustion temperature and energy release associated with conventional jet fuel. In contrast, biodiesel blends displayed a progressive downward shift in the working line with increasing blend ratio, amounting to a reduction of approximately 10% at high airflow for B30. Importantly, however, the slope and linearity of the working lines were preserved for all fuels, indicating that compressor stability margins remained unaffected by biodiesel substitution. This observation highlights that blending up to 30% biodiesel reduces performance levels but does not compromise the aerodynamic stability of the engine.

The transient response was further investigated by analyzing the behavior of the working line during sudden acceleration and deceleration maneuvers (Figure 9). During acceleration, all fuels exhibited an upward overshoot in pressure ratio relative to the steady-state line. Jet A produced the most pronounced peak (πc ≈ 1.9), while biodiesel blends demonstrated progressively lower overshoots, reaching approximately 1.80 for B30. These differences can be attributed to the lower heating value and modified combustion kinetics of biodiesel, which reduce the intensity of transient energy release. Conversely, during deceleration, all fuels showed a downward displacement of the working line, with Jet A again presenting the sharpest undershoot and biodiesel blends showing smoother, less pronounced drops. This suggests that the oxygenated nature of biodiesel and its slower combustion kinetics dampen abrupt fluctuations, contributing to a more gradual transition during fuel cutbacks.

Despite the observed deviations during transients, the loops describing acceleration and deceleration remained well-behaved for all fuels, with no signs of compressor surge or instability. The working line trajectories converged rapidly back to the steady-state curve, confirming that the microturbine maintained stable operation across all tested fuels. The biodiesel blends, while slightly reducing peak transient response, appeared to enhance overall robustness by attenuating oscillations during abrupt maneuvers.

In summary, the analysis of transient performance indicates that biodiesel blending up to 30% introduces a uniform reduction in pressure ratio across the operating envelope, without affecting compressor stability margins. Furthermore, biodiesel blends smooth out transient excursions during acceleration and deceleration, thereby offering enhanced stability against abrupt load changes. These findings suggest that camelina biodiesel can be safely integrated into microturbine applications, with only minor penalties in peak performance but potential benefits in transient stability.

4. Discussion

The findings obtained in this study on the JetCat P80 micro-gas turbine are consistent with those of previous research that evaluated camelina-derived fuels in gas turbine applications. Wang et al. [18,21] investigated camelina oil–derived jet fuel blends in distributed combustion conditions. They reported good combustion stability and reductions in CO and NOX emissions when moderate blending ratios were used, findings which align with the improved flame stability and reduced overshoot/undershoot observed in the present work. In their tests, Wang et al. [18] reported temperature reductions of approximately 50–80 °C and NOX and CO decreases of 15–25% compared to Jet A, values consistent with the 40–60 °C lower exhaust temperatures and 10–30% emission variations obtained in the present study. Their conclusion that camelina-derived fuels can be safely blended with conventional kerosene without major hardware modifications supports the technical feasibility demonstrated here.

Similarly, Gawron et al. [19] studied the combustion and emission characteristics of HEFA blends derived from camelina and other feedstocks in a turbine engine. Their results indicated stable combustion and emission reductions, particularly in hydrocarbons and particulates, with performance metrics comparable to Jet A1. They reported reductions of up to 20–30% in particulate matter and unburned hydrocarbons, along with less than 2% variation in thrust compared to Jet A1—values that closely match the present findings of a 10–30% decrease in SO2 and negligible thrust deviation when using camelina-based HEFA blends. The trends observed in the present study—reduced SO2 due to sulfur-free composition and negligible thrust penalties—are consistent with these outcomes, reinforcing the role of camelina-based HEFA as a viable SAF pathway.

Llamas et al. [20] analyzed the production of biokerosene from camelina and Babassu oils. Their blends with fossil kerosene partially met ASTM specifications and displayed good cold-flow properties, although oxidative stability and calorific value were limiting factors. These challenges mirror the observations in the current work, where biodiesel blends reduced combustion temperatures at high load due to their lower heating value, pointing to the need for process optimization or additive strategies to improve thermal stability. They reported heating values 8–10% lower than fossil kerosene and a corresponding reduction of about 50 °C in combustion temperature, which is consistent with the 40–60 °C decrease observed in the present study for higher biodiesel blend ratios.

Experimental validation at microturbine scale was also conducted by Petcu et al. [22], who tested camelina–kerosene blends in a micro-gas turbine. Their study showed that while such fuels are technically feasible, viscosity and atomization issues necessitate preheating or blending with kerosene for stable combustion. They observed CO emission increases of about 20–35% at idle when using neat camelina oil or high-viscosity blends, values comparable to the 10–30% rise recorded in the present study, confirming that incomplete oxidation at low temperatures remains the main limitation for unheated biofuel operation.

Complementary burner-scale investigations by Mangra et al. [23] and Petcu et al. [24] further demonstrated that pure camelina oil faces significant challenges related to atomization and flame stability, which can be partially mitigated by blending with kerosene and preheating. They reported flame temperature drops of 60–90 °C and instability amplitudes up to 15% when using pure camelina oil, values comparable to the 40–60 °C temperature decrease and increased thermal variability observed in the present work for the B30 blend, confirming similar atomization and combustion stability limitations.

Overall, the present work extends the body of knowledge by providing systematic stationary and transient performance data for camelina biodiesel–Jet A blends in a micro-gas turbine. Compared with earlier studies, it confirms that blending up to 30% is technically feasible, environmentally beneficial (particularly in terms of SO2 reduction), and operationally robust, though efficiency penalties at idle and reduced combustion temperatures at higher loads remain key challenges. These results suggest that camelina-derived fuels can complement existing SAF pathways, with microturbine experiments serving as a scalable testbed for larger propulsion systems.

A clear correlation was observed between the physicochemical properties of the tested fuels and the turbine performance parameters. The slightly higher density (up to +3%) and viscosity (+12–18%) of the camelina biodiesel blends led to reduced atomization efficiency and slower evaporation, resulting in lower combustion chamber temperatures (−40 to −60 °C compared to Jet A) at intermediate and high regimes. This behavior is consistent with findings by Zhang et al. (2022) [45] and Tarangan et al. (2023) [46], who reported that increased viscosity and reduced volatility limit air–fuel mixing and lower flame temperatures in biodiesel–kerosene systems. Conversely, the intrinsic oxygen content of biodiesel improved oxidation completeness, explaining the reduced fuel flow (−4 to −9%) and smoother transient response observed experimentally.

Although the total fuel flow rate decreases with rotational speed, the specific fuel consumption (SFC) increases at low-load operation. This behavior cannot be attributed solely to the reduced lower heating value of biodiesel, but rather to combined effects related to atomization and combustion efficiency. The higher viscosity of the biodiesel blends leads to coarser droplets and less homogeneous air–fuel mixing, which in turn lowers combustion temperature and efficiency. Moreover, the lower chamber pressure and incomplete evaporation at partial regimes contribute to increased SFC, as more fuel mass is required to achieve stable flame conditions.

Overall, these correlations confirm that the modest physical property deviations of camelina biodiesel relative to Jet A directly shaped the thermal and emission behavior of the engine, reinforcing the observed trade-off between efficiency and combustion temperature.

The substitution of Jet A with camelina biodiesel blends resulted in systematic and measurable variations across all parameters. Fuel flow decreased by 4–9% depending on regime, while thrust reduction remained below 2% even for the highest biodiesel concentration (B30). Specific fuel consumption increased slightly at idle by 5–8%, but the difference became negligible (<2%) at higher loads. Combustion temperature variations reached up to ±60 °C, exceeding the combined measurement uncertainty (±10–17 °C), confirming that the effects were statistically significant. CO emissions increased by 10–35% at idle, while SO2 levels decreased linearly by 10–30% across all regimes. The estimated overall uncertainties for performance indicators were within ±5%, reinforcing the quantitative robustness of the observed trends.

5. Conclusions

The experimental campaign performed on the JetCat P80 micro-gas turbine using Jet A and camelina biodiesel blends (B10, B20, B30) has provided a comprehensive understanding of the influence of alternative fuels on engine performance, emissions, and stability. The results demonstrate that biodiesel blending introduces both advantages and trade-offs, depending on the operating regime. At low load, moderate biodiesel additions enhanced combustion through increased flame temperatures, whereas at intermediate and high loads, blends reduced peak combustion temperatures, contributing to potential NOx mitigation. Fuel flow was consistently lower for biodiesel blends, while thrust penalties remained negligible across regimes. Specific fuel consumption was slightly penalized at idle but nearly identical to Jet A at higher loads, confirming the efficiency of biodiesel substitution under real operating conditions. Emissions showed a mixed trend, with increased CO at idle offset by substantial reductions in SO2 across all regimes. Importantly, transient stability analyses revealed that biodiesel blends smoothed the engine’s dynamic response, reducing overshoots and undershoots during abrupt load changes. Taken together, these findings confirm the technical feasibility of biodiesel use in microturbines and its potential contribution to cleaner and more sustainable aviation fuels.

- (a)

- Physico–chemical characterization of camelina biodiesel confirmed higher density, viscosity, and flash point compared to Jet A, along with lower heating value and absence of sulfur, properties that directly influenced combustion and emissions.

- (b)

- Combustion temperature analysis showed that B10 and B20 increased flame stability at low load, whereas all blends reduced peak temperatures at higher regimes, a trend beneficial for NOx mitigation.

- (c)

- Fuel flow decreased consistently with biodiesel content across all regimes (up to 9% reduction at idle), without significant loss of thrust.

- (d)

- Specific fuel consumption was penalized by 5–8% at idle due to the lower heating value of biodiesel but remained nearly identical to Jet A at intermediate and high loads, confirming the efficiency of partial substitution.

- (e)

- Emission results demonstrated that biodiesel blends increased CO at idle but had negligible effect at full power, while SO2 emissions decreased proportionally with the blend ratio, providing a clear environmental benefit.

- (f)

- Engine stability was preserved, with transient response analyses showing that biodiesel blends reduce the amplitude of overshoot and undershoot during abrupt accelerations and decelerations, thereby improving robustness against instabilities.

- (g)

- Overall, the results confirm that camelina biodiesel blends up to 30% represent a technically and environmentally viable option for aviation microturbines, though optimization of injection strategies and combustor design may be required to fully compensate for reduced energy density at high blends.

The main findings indicate that biodiesel substitution leads to slightly lower combustion temperatures and marginal increases in specific fuel consumption at low load, while thrust and overall efficiency remain nearly unchanged at higher regimes. Emissions analyses confirmed a consistent reduction in SO2 due to the sulfur-free nature of biodiesel, alongside a moderate rise in CO at idle, reflecting the balance between environmental benefits and combustion completeness. Transient testing showed that biodiesel blends improve dynamic stability by reducing overshoot and undershoot amplitudes during rapid load changes.

Future research will focus on a more detailed characterization of the transient behavior of the micro-gas turbine when operating on Camelina-based biodiesel blends. This will include the quantitative determination of time constants, maximum deviations, and dynamic stability parameters, as well as the analysis of atomization quality and combustion efficiency under variable operating conditions. In addition, the lower heating value of the tested biofuel will be experimentally determined to enable an energy-based evaluation of thermal efficiency and combustion performance. These investigations will provide a more comprehensive understanding of the dynamic response and energetic potential of sustainable fuels for small-scale turbine applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.C.; methodology, C.D.; software, S.O.; validation, G.C., C.D., S.O. and R.S.; formal analysis, C.D.; investigation, S.O.; writing—original draft preparation, G.C., C.D., S.O. and R.S.; writing—review and editing, G.C., C.D., S.O. and R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the National Program for Research of the National Association of Technical Universities—GNAC ARUT 2023, grant no. 105/11.10.20.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Nomenclature

| T [N] | Thrust |

| Tcomb [°C] | Combustion chamber temperature |

| Ff [kg/s] | Fuel mass flow |

| Ff [L/s] | Fuel flow |

| Af [kg/s] | Air mass flow |

| S [kh/Nh] | Specific fuel consumption |

| πc | Pressure ratio |

| SO2 [ppm] | The concentration of sulfur dioxide |

| CO [ppm] | The concentration of carbon monoxide |

| R1, R2, R3 | Engine operating regimes (idle, intermediate, high speed) |

| B10, B20, B30 | Fuel blends containing 10%, 20%, and 30% biodiesel, respectively |

References

- Available online: https://www.icao.int/CORSIA (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Su-Ungkavatin, P.; Tiruta-Barna, L.; Hamelin, L. Biofuels, electrofuels, electric or hydrogen? A review of current and emerging sustainable aviation systems. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2023, 96, 101073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reda, B.; Elzamar, A.A.; AlFazzani, S.; Ezzat, S.M. Green hydrogen as a source of renewable energy: A step towards sustainability, an overview. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cican, G.; Silivestru, V.; Mirea, R.; Osman, S.; Popescu, F.; Sapunaru, O.V.; Ene, R. Performance and Emissions Assessment of a Micro-Turbojet Engine Fueled with Jet A and Blends of Propanol, Butanol, Pentanol, Hexanol, Heptanol, and Octanol. Fire 2025, 8, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcau, J.-I.; Dinca, L.; Cican, G.; Ionescu, A.; Negru, M.; Bogateanu, R.; Cucu, A.-A. Studies Concerning Electrical Repowering of a Training Airplane Using Hydrogen Fuel Cells. Aerospace 2024, 11, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Ting, Z.J.; Zhao, M. Sustainable aviation fuels: Key opportunities and challenges in lowering carbon emissions for aviation industry. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2024, 13, 100263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimczyk, W.; Jasiński, R.; Niklas, J.; Siedlecki, M.; Ziółkowski, A. Sustainable Aviation Fuels: A Comprehensive Review of Production Pathways, Environmental Impacts, Lifecycle Assessment, and Certification Frameworks. Energies 2025, 18, 3705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doliente, S.S.; Narayan, A.; Tapia, J.F.D.; Samsatli, N.J.; Zhao, Y.; Samsatli, S. Bio-aviation Fuel: A Comprehensive Review and Analysis of the Supply Chain Components. Front. Energy Res. 2020, 8, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altarazi, Y.S.; Abu Talib, A.R.; Yusaf, T.; Yu, J.; Gires, E.; Ghafir, M.F.A.; Lucas, J. A review of engine performance and emissions using single and dual biodiesel fuels: Research paths, challenges, motivations and recommendations. Fuel 2022, 326, 125072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, W.N.A.W.; Rosli, M.H.; Mazli, W.N.A.; Samsuri, S. Comparative review of biodiesel production and purification. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2024, 13, 100264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Chowdhury, A. An exploration of biodiesel for application in aviation and automobile sector. Energy Nexus 2023, 10, 100204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, G.; Ciekot, Z.; Nowakowski, M.; Płochocki, P.; Skrzek, T. The impact of hydrogen on the combustion of Camelina sativa Oil in dual-fuel CI engine. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 143, 701–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, M.; Mohanty, A.K.; Van Acker, R.; Riddle, R.; Todd, J.; Khalil, H.; Misra, M. Valorization of camelina oil to biobased materials and biofuels for new industrial uses: A review. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 27230–27245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dangol, N.; Shrestha, D.S.; A Duffield, J. Life Cycle Analysis and Production Potential of Camelina Biodiesel in the Pacific Northwest. Trans. ASABE 2015, 58, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydogan, H.A.; Ozcelik, E.; Acaroglu, M. An Experimental Study of the Effects of Camelina sativa Biodiesel-Diesel Fuel on Exhaust Emissions in a Turbocharged Diesel Engine. J. Clean Energy Technol. 2017, 5, 254–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, G.; Skrzek, T. Combustion of raw Camelina sativa oil in CI engine equipped with common rail system. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumal, R.R.; Liu, J.; Gharpure, A.; Wal, R.L.V.; Kinsey, J.S.; Giannelli, B.; Stevens, J.; Leggett, C.; Howard, R.; Forde, M.; et al. Impact of Biofuel Blends on Black Carbon Emissions from a Gas Turbine Engine. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 4958–4966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, Z.; Feser, J.S.; Lei, T.; Gupta, A.K. Performance and emissions of camelina oil derived jet fuel blends under distributed combustion condition. Fuel 2020, 271, 117685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawron, B.; Białecki, T.; Janicka, A.; Suchocki, T. Combustion and emissions characteristics of the turbine engine fueled with HEFA blends from different feedstocks. Energies 2020, 13, 1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llamas, A.; Al-Lal, A.-M.; Hernandez, M.; Lapuerta, M.; Canoira, L. Biokerosene from Babassu and Camelina oils: Production and properties of their blends with fossil kerosene. Energy Fuels 2012, 26, 5968–5976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangra, A.; Sandu, C.; Enache, M.; Florean, F.; Carlanescu, R.; Kuncser, R. Preliminary camelina oil combustion tests on a micro gas turbine fire tube. Turbo 2018, V, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Petcu, A.C.; Sandu, C.; Berbente, C. Biofuel, Camelina Oil, Exhaust Gases, Micro Gas Turbine. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2014, 555, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangra, A.; Porumbel, I.; Florean, F. Experimental measurements of Camelina sativa oil combustion. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2018, 44, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petcu, A.; Florean, F.; Porumbel, I.; Berbente, C.; Silivestru, V. Experiments regarding the combustion of camelina oil/kerosene mixtures on a burner. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2016, 33, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D4052-15; Standard Test Method for Density, Relative Density, and API Gravity of Liquids by Digital Density Meter. ASTM—American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- ASTM D7042; Standard Test Method for Dynamic Viscosity and Density of Liquids by Stabinger Viscometer (and the Calculation of Kinematic Viscosity). ASTM—American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- ASTM D93-2020; Standard Test Methods for Flash Point by Pensky-Martens Closed Cup Tester. ASTM—American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- ASTM D5453-2019a; Standard Test Method for Determination of Total Sulfur in Light Hydrocarbons, Spark Ignition Engine Fuel, Diesel Engine Fuel, and Engine Oil by Ultraviolet Fluorescence. ASTM—American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- ASTM D6371-17a; Standard Test Method for Cold Filter Plugging Point of Diesel and Heating Fuels. ASTM—American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- ASTM D2500-17a; Standard Test Method for Cloud Point of Petroleum Products and Liquid Fuels. ASTM—American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- ASTM D56-22; Standard Test Method for Flash Point by Tag Closed Cup Tester. ASTM—American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- ASTM D86; Standard Test Method for Distillation of Petroleum Products and Liquid Fuels at Atmospheric Pressure. ASTM—American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023.

- Sharon, V.; Jillsona, V.; Hashimb, H.; Alafiza Yunus, N. Physical-Chemical Properties of Jet Fuel Blends with Biofuels Derived from Waste. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2024, 113, 307–312. [Google Scholar]

- Mirea, R.; Cican, G. Theoretical Assessment of Different Aviation Fuel Blends based on their Physical-Chemical Properties. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2024, 14, 14134–14140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, S.; Ceatra, L.; Cican, G.; Mirea, R. Physicochemical Properties of Jet-A/n-Heptane/Alcohol Blends for Turboengine Applications. Inventions 2025, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catana, R.M.; Cican, G.; Badea, G.-P. Thermodynamic Analysis and Performance Evaluation of Microjet Engines in Gas Turbine Education. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattingly, J. Elements of Propulsion: Gas Turbines and Rockets, 2nd ed.; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- EN 14214:2012; Liquid Petroleum Products—Fatty Acid Methyl Esters (FAME) for Use in Diesel Engines and Heating Applications—Requirements and Test Methods. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2012.

- Ciubota-Rosie, C.; Ruiz, J.R.; Ramos, M.J.; Pérez, Á. Biodiesel from Camelina sativa: A comprehensive characterisation. Fuel 2013, 105, 572–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich, A.; Rice, B. Evaluation of C. sativa oil as a feedstock for biodiesel production. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2005, 21, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, B.; Vaughn, S. Evaluation of alkyl esters from C. sativa oil as biodiesel and as blend components in ultra low-sulfur diesel fuel. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 646–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ÖNORM C 1191; Kraftstoffe—Dieselmotoren; Fettsauremethylester, Anforderungen. Austrian Standards International: Vienna, Austria, 1997.

- Soriano, N.U., Jr.; Narani, A. Evaluation of Biodiesel Derived from Camelina sativa Oil. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2012, 89, 917–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, E.J. Chapter 8—Camelina (Camelina sativa). In Industrial Oil Crops; McKeon, T.A., Hayes, D.G., Hildebrand, D.F., Weselake, R.J., Eds.; AOCS Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 2016; pp. 207–230. ISBN 9781893997981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Lu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Tan, D. A Comprehensive Review of the Properties, Performance, Combustion, and Emissions of the Diesel Engine Fueled with Different Generations of Biodiesel. Processes 2022, 10, 1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarangan, D.; Sobati, M.A.; Shahnazari, S.; Ghobadian, B. Physical properties, engine performance, and exhaust emissions of waste fish oil biodiesel/bioethanol/diesel fuel blends. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 14024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |