Abstract

This work highlights the feasible fabrication of translucent ceramics from un-doped and Nd3+-doped BaLaLiWO6 (BLLW) and BaLaNaWO6 (BLNW) cubic tungstates using the Spark Plasma Sintering (SPS) method. Ceramics were sintered using pure-phase, homogeneous powders with submicron particle sizes, obtained via the solid-state reaction method. The present study investigated the microstructural, structural, and spectroscopic properties of both un-doped and Nd3+-doped sintered specimens. All the ceramic materials exhibited certain drawbacks that significantly contributed to their low transparency in both sample types. However, initial spectroscopic tests on sintered translucent ceramics doped with Nd3+ ions revealed promising properties, comparable to those of the powdered samples. Therefore, we believe that producing higher-quality ceramics would improve their spectroscopic properties. For that, further optimization of the manufacturing conditions is necessary.

1. Introduction

For nearly three decades, transparent ceramics have attracted significant attention as advanced optical materials. These materials are prized for their combination of optical transparency (comparable with single-crystal materials) and exceptional mechanical properties. Recently, the range of applications for transparent ceramics has expanded significantly, extending to highly sophisticated uses such as optically active materials for solid-state laser gain media, light converters, and scintillators. Optically passive ceramics are now employed in armored windows, infrared domes, and electro-optical components, significantly impacting various industries and everyday life [1,2,3]. Additionally, their use in photonics, particularly when doped with rare earth elements, has become increasingly important.

It is well established that achieving transparency in specimens is not universally possible for all inorganic compounds. For single-crystal materials, good transmission of visible light requires an energy band gap wider than the energy of visible photons—that is, greater than 3 eV. In the case of polycrystalline ceramics, however, additional challenges arise. Light scattering can occur at grain boundaries, residual pores, secondary phases, or impurities, all of which can significantly impair optical performance. Among these effects, the most common cause of translucency is scattering from pores within the material, making the elimination of porosity a critical goal. To produce transparent ceramics, full densification must be achieved during sintering so that all pores are completely removed. Another key factor is the choice of inorganic matrix: the crystallographic system should have high symmetry, ideally cubic, to ensure optical isotropy.

Advanced sintering techniques are crucial for achieving high optical quality in ceramics. In recent years, Spark Plasma Sintering (SPS) has emerged as a promising alternative to Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP) for producing transparent ceramics [4]. SPS is a densification method that utilizes high pressure and temperature, generated by a strong electrical current passing through a conductive die, usually made of graphite. This technique has gained widespread adoption for its ability to reduce the required sintering temperature by achieving rapid heating rates exceeding 200–300 °C/min. This approach significantly shortens processing time while simultaneously applying pressure during heating. Lastly, the number of articles on ceramics produced using this method has grown substantially. This technique has been instrumental in fabricating high-quality transparent ceramics such as MgAl2O4 [5], Al2O3 [6], and YAG [7], including these for optics doped with RE3+, like YAG, Y2O3 [8], or Lu2O3 [9,10]. Extensive research focuses on the impact of sintering parameters, such as temperature and pressure, on final density, which directly enhances the transparency of ceramic samples [11].

The initial materials used for preparing ceramics should be characterized by high chemical and structural purity, with excellent sintering capability. Additionally, the powders should be homogeneous in size and shape, with grains being as spherical as possible to ensure optimal stacking. Achieving such high-quality initial materials is therefore a critical challenge. Given these strict requirements, it is evident that producing high-quality transparent ceramics is a highly demanding process. This explains why only a limited number of transparent ceramics have been developed and widely adopted as practical optical materials, as outlined in our previous articles [12,13,14].

This work introduces BLLW and BLNW cubic tungstates as a new class of translucent ceramics, previously reported only in the form of micro-powders or single crystals. Their structural framework provides multiple substitutional sites, enabling the incorporation of optically active ions with 4f and 5d electrons. This compositional flexibility, combined with the successful fabrication of translucent ceramics, underscores the novelty of these materials and their potential as versatile platforms for advanced photonic applications.

Building on this concept, the present study extends our research into Nd3+-doped BLLW and BLNW tungstates as novel ceramic optical materials. In earlier work [15], we investigated the structural, morphological, and spectroscopic properties of both un-doped and Nd3+-doped microcrystalline powders. Here, we advance this effort by fabricating polycrystalline sintered ceramics using the Spark Plasma Sintering (SPS) method and conducting comparative analyses with their micro-powdered counterparts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of Micro-Powders

For the synthesis, high-purity commercial precursors were employed: BaCO3 (Aldrich, 99.999%), Li2CO3 (Acros Organics, 99.999%), Na2CO3 (Acros Organics, 99.999%), La2O3 (Stanford Materials, 99.999%), Nd2O3 (Apollo, 99.995%), and (NH4)10H2W12O42· 4H2O (Aldrich, 99.99%). Passive and Nd3+-substituted microcrystalline powders were synthesized by a conventional solid-state reaction route with a dopant concentration of 1 mol%. Prior to synthesis, La2O3 and Nd2O3 were pre-calcined at 850 °C in two successive 12-h cycles to eliminate absorbed carbonates and residual moisture. A 20 mol% excess of Li2CO3 was introduced to compensate for its volatility. In this case, Li2CO3 acted not only as a reactant but also as a fluxing agent, enhancing reactivity and facilitating the formation of a single phase. In the case of BLNW, no excess was necessary; reagents were used in strictly stoichiometric amounts. The starting materials were intimately ground in an agate mortar with a small amount of acetone to ensure homogeneity. The resulting mixtures were then heated at 500 °C for 10 h in corundum crucibles under static air. After controlled cooling to room temperature (RT), the powders were reground with acetone to improve reactivity. Subsequently, the samples were annealed at 1000 °C for 10 h, reground, and homogenized again. In the case of BLNW, an additional heat treatment at 1000 °C for 5 h was required to obtain phase-pure products. At each stage of thermal processing, the phase composition was verified using X-ray diffraction (XRD).

2.2. Fabrication of Sintered Ceramics by the SPS Technique

Un-doped and Nd3+-doped BLLW and BLNW micro-crystalline powders obtained using the solid-state reaction method served as initial materials for the sintering process. The powders were loaded into a graphite die with a 10 mm diameter, part of the SPS machine, model HPD 25 (FCT system GmbH, Rauenstein, Germany). The die was wrapped with 5 mm thick graphite wool to provide thermal insulation. The inner surface of the graphite die was lined with a 0.35 mm-thick graphite foil. A thermocouple monitored the temperature. Various sintering regimes were tested to evaluate the effect of SPS processing parameters on the final quality and properties of the obtained specimens. The selected processing parameters for the SPS treatment included a sintering temperature of 1100 °C, a holding time of 10 min. at the sintering temperature, and a heating rate ranging from 2 °C/min to 100 °C/min. A constant axial pressure of 90 MPa was applied from room temperature (RT) throughout the entire cycle. The sintering process was performed in a vacuum. Identical quantities of powder were used in all tests and placed between the pistons inside the die. The thickness of the sample after sintering was approximately 1.6–1.8 mm. Annealing of the sintered ceramics was carried out at 800 °C in air for 2 h to achieve color correction and ensure complete removal of residual graphite. Polishing, the final stage described in the following section, was conducted to assess the optical properties of the fabricated ceramics. This procedure resulted in a reduction of the sample thickness by approximately 1–1.5 mm.

2.3. Characterization of Ceramic Samples

2.3.1. Structural Analysis

XRD patterns were measured using a D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany). The measurements were performed at RT within the range of 10–80 2θ with a scan rate of 0.008° per step and a counting time of 5 s per step. Nickel-filtered CuKα radiation (Kα1+2, λ = 0.15418 nm) was used for the experiment. The diffractograms were compared with the simulated XRD pattern of cubic BLNW (ICSD #2313366) and BLLW (ICSD #2177313), respectively.

2.3.2. Microscopic Analysis via Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

The morphology and grain size of sintered ceramics were investigated by SEM using the Hitachi S-3400 N microscope equipped with the energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy EDS detector Thermo Scientific Ultra Dry (Karlsruhe, Germany). The observations were made under the backscattered electrons (BSE) mode with an accelerating voltage of 30 kV and a beam current equal to 20 and 30 pA. The ceramics were not coated with any gold alloy layer. Two polishing methods were applied to prepare the ceramic samples for SEM analysis.

Disc Polishing

The polishing process was carried out as follows: initially, diamond shields with grit sizes of 200, 500, 1200, and 4000 µm were used. Then, diamond grains suspended in a lubricating fluid were applied to polishing cloths with 5 µm, 3 µm, 1 µm, and 100 nm grit sizes. After each stage, the polishing effect was continuously monitored to ensure the best quality mirror-finished samples. Disc polishing affects more than just material removal; it also influences microstructure, residual stresses, and surface roughness. To minimize these effects and maintain surface uniformity, the final sample thickness ranged from 1 to 1.5 mm. This carefully controlled variation minimized material removal while maximizing surface quality.

Ionic Polishing

Ionic polishing was used before some observations of the internal surface of the sample, free of any debris that might fill the small pores and grain boundaries after the disc polishing. For that, an ILION II+ from Gatan equipped with a double ion gas gun at an angle of incidence of −10 to 10° was used. The energy of the gun was set at 6 keV for 4 h.

2.3.3. Absorption Measurements

Absorption spectra were measured using a Cary-Varian 5000 Scan UV-Vis-NIR spectrophotometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with an Oxford CF 1204 helium flow cryostat. The measurements were realized in the 400–900 nm spectral range at 4.2 K and RT.

2.3.4. Luminescence Measurements

Emission spectra and luminescence decay curves at RT and 77K were recorded under pulsed laser excitation (OPO laser, EKSPLA NT342, 10 Hz, 7 ns) and non-selective Thorlabs 810 LED excitation. The emission spectra were recorded using an InGaAs CCD camera by ANDOR, followed by a Shamrock 500 monochromator equipped with a 1 μm blazed grating. The decay times of the fluorescence around 880 nm were detected with a Hamamatsu NIR PMT H10330B-75 coupled to a Wave Runner 64Xi Lecroy (Chestnut Ridge, NY, USA) digital scope.

2.3.5. Total Transmission Measurements

The total forward transmission (TFT) of BLNW and BLLW ceramics was recorded using an Edinburgh FLS980 spectrofluorometer (Edinburgh, Scotland), equipped with a 450 W Xenon continuous arc lamp, R928P, R2658P PMT detectors, and an integrating sphere. The measurements were performed at RT in the 300–850 nm spectral range. The transmission was normalized to 1 mm thickness. For this measurement, the ceramic samples were prepared using disc polishing, following the previously described procedure.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Analysis of Sintered Micro-Ceramics

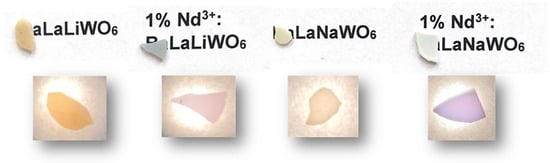

Photographs of the mirror-polished ceramics, fabricated via the SPS method, reveal that under the indirect light of a simple flashlight, the SPS-sintered materials exhibit a certain degree of transparency (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The photographs of the first translucent sintered ceramics of un-doped and activated by the Nd3+ ion BLLW and BLNW.

The un-doped micro-ceramics exhibit a light yellowish color, potentially due to the presence of oxygen vacancies in the structure. Similar phenomena have been observed for Yb3+-doped La2MoWO9 molybdato-tungstates [12]. In the case of Nd3+-doped samples, a characteristic violet color, typical of materials activated with the Nd3+ ion, was observed. This coloration can be attributed to the forbidden f-f absorption transitions of the optically active ion.

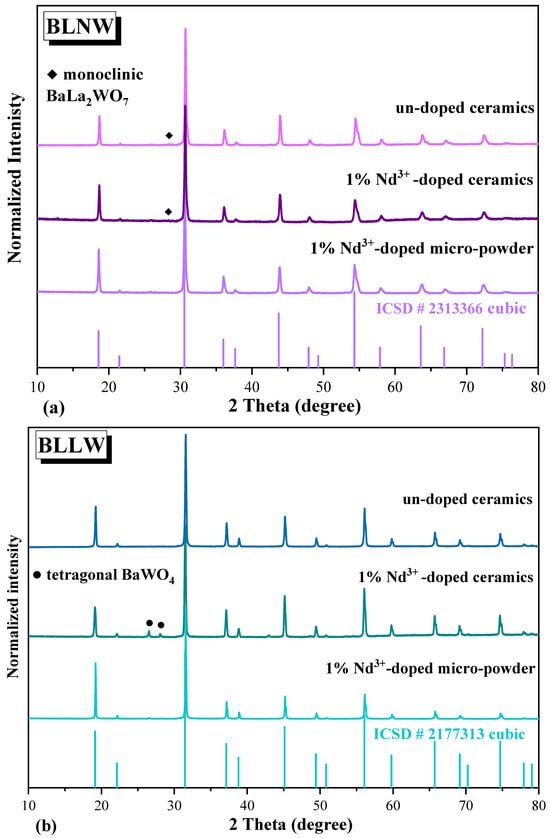

3.2. Structure Analysis by X-Ray Diffraction

All the obtained sintered bodies were analyzed using the X-ray powder diffraction method at RT. Figure 2 presents the XRD patterns of initial powders and sintered ceramics of un-doped and 1% Nd3+-doped BLNW (a) and BLLW (b) along with the simulated XRD patterns (ICSD #2313366) and (ICSD #2177313), respectively. The patterns display all the main peaks corresponding to the cubic phase of BLNW and BLLW. In the case of BLNW, a reflection observed at 28.4° 2θ of very weak intensity corresponds to the monoclinic BaLa2WO7 phase. We suppose that the trace amounts of this phase are present both in un-doped and 1% Nd3+-doped micro-ceramics. In turn, for BLLW, two additional reflections at 26.5° and 28° 2θ of weak intensity correspond to the tetragonal BaWO4 phase and were observed exclusively for 1% Nd3+-doped ceramic samples. Only the un-doped BLLW micro-ceramics seem to exhibit phase purity. Following the detailed high-temperature XRD analysis presented in our previous study [15], the formation of monoclinic BaLa2WO7 or tetragonal BaWO4 phases can be attributed to the thermal decomposition of the initial powders. Considering that the SPS process was conducted at a temperature of 1100 °C, it’s plausible that random local temperature spikes, up to 1130 °C, occurred, contributing to phase decomposition. However, a too low sintering temperature resulted in insufficient densification and substantial interconnected porosity, and a too high temperature above 1130 °C was not feasible, as the targeted perovskite phase begins to decompose, leading to secondary-phase formation [15].

Figure 2.

Powder XRD patterns of initial powders and sintered ceramics of un-doped and 1% Nd3+-doped BLNW (a) and BLLW (b).

Here, we present the results of our initial tests with these materials, and we believe that adjusting the synthesis conditions will enable the production of ceramics free from traces of additional phases.

3.3. Morphology and Particle Size Analysis by SEM

3.3.1. Micro-Powders of Un-Doped and 1% Nd3+-Doped BLLW and BLNW

The morphology of BLLW and BLNW micro-powders, both un-doped and activated with Nd3+ ions was examined by SEM. As shown in Figure S1, the powders are homogeneous, with spherical grains forming loose clusters and distinct grain boundaries. BLNW particles are larger (1.6–6.2 µm) than those of BLLW (0.9–3.9 µm), likely due to the additional 1000 °C/5 h heating step in BLNW synthesis. Grains remain mostly regular and well-separated, with occasional agglomerates up to 5–7 µm. Nd3+ doping did not significantly affect morphology or grain size.

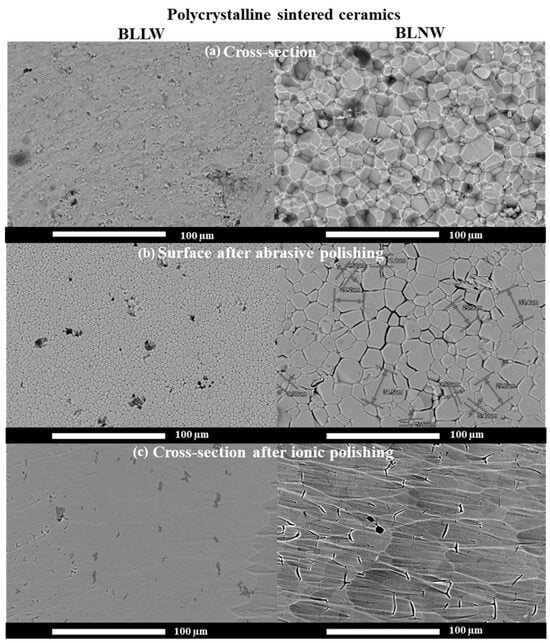

3.3.2. Un-Doped Ceramics of BLLW and BLNW

Figure 3 presents SEM micrographs of un-doped BLLW and BLNW polycrystalline ceramics. For a more comprehensive microstructural analysis, three distinct imaging approaches have been applied under the same magnification: (a) cross-sectional morphology analysis, (b) examination of the surface after disc polishing, and (c) cross-sectional examination after ionic polishing.

Figure 3.

SEM micrographs of the cross-section (a), the surface after disc polishing (b), and the cross-section after ionic polishing (c) of un-doped BLLW and BLNW polycrystalline ceramics.

The first approach enabled the observation of well-compacted grains with a homogeneous morphology (Figure 3a). At the same magnification, we observe larger grain sizes in the BLNW ceramics (ranging from 3.9 to 33.4 µm) than in the BLLW ceramics (ranging from 1.5 to 7.4 µm). In both types of polycrystalline ceramics, individual crystal grains remain distinctly separated by grain boundaries. Larger grains seen for BLNW are also observed in the micrographs of the ceramic surface analyzed after disc polishing (Figure 3b). The BLNW grains do not fit closely together, leaving gaps between them. These defects are present along the grain boundaries, which may result from internal stresses in the microstructure. In contrast, the material sintered from BLLW consists of more tightly packed, irregular particles ranging from 1.1 to 10.7 µm. This material exhibited better sintering ability. However, random intergranular pores are present in this ceramic, which may cause direct light scattering and reduce transmission properties. In the micrographs presented in Figure 3a, it is unclear whether the visible holes (darker places) resulted from the fracture of the ceramics to perform cross-sectional analysis (removed grains) or whether they are open pores. Therefore, in the next step, the ionic polishing process was performed on the cross-section of BLLW and BLNW ceramics before the additional analysis. It helped to reveal the presence of a second phase (darker area) in the BLLW sample on a perfectly flat surface (Figure 3c). Most probably, it corresponds to the presence of a BaWO4 phase, an impurity occurring during the thermal decomposition of BLLW. However, this observation contrasts with the earlier XRD analysis, which indicated that the un-doped sample was free of the second phase. Despite this, the SEM analysis clearly shows the presence of BaWO4 even in the un-doped sample, highlighting the complementary nature of XRD and SEM techniques. For BLNW ceramics, the cracks between the grains are very visible, and open pores occasionally appear. All these defects observed for both types of samples could significantly affect the ceramics’ transparency.

3.3.3. Comparison of 1% Nd3+-Doped BLLW and 1% Nd3+-Doped BLNW Ceramics at Low Magnification

Figure S2 presents micrographs of Nd3+-doped BLLW and Nd3+-doped BLNW micro-ceramics after disc polishing. The two samples exhibit distinctly different morphologies. Nd3+-doped BLLW sample seems to be better compacted and consists of closely packed particles. However, some open pores ranging from 3 to 16.5 µm can be easily seen. Using the same magnification for the analogous sodium-containing sample gives the impression that it has significantly more open pores.

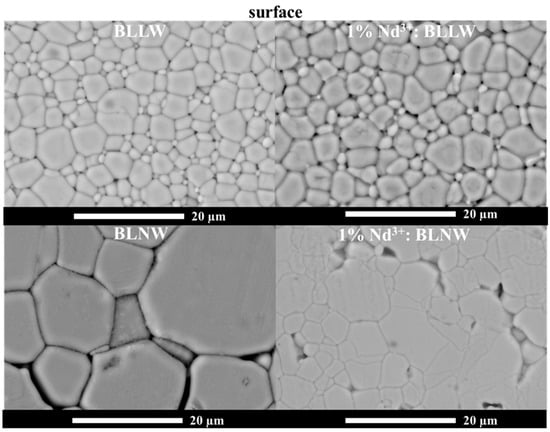

3.3.4. Comparison of All Fabricated Ceramics at High Magnification

Figure S3 presents the surface morphology of un-doped and Nd3+-doped ceramics after disc polishing. The micrographs reveal smaller, isolated grains scattered among well-compacted grains. For BLLW samples at higher magnification, it is evident that the seemingly well-compacted grains do not tightly adhere to each other, and submicron pores are visible. In the case of Nd3+-doped BLLW, the grains are even more loosely arranged and connected by bridges.

Figure 4 shows the magnifications of the cross-sectional morphology of un-doped BLLW and 1% Nd3+-doped BLLW ceramics. Here, the bridges are even better seen, especially in the case of the 1% Nd3+-doped BLLW sample. By comparison, BLNW lacks bridge connections, has a reduced number of fine grains, and exhibits distinct intergranular gaps. For the Nd3+-activated sample, the grains tightly adhere to each other; however, numerous open pores of various sizes are present. The samples exhibit high porosity, which hinders the achievement of satisfactory transparency. Due to their very small dimensions, density measurements using the Archimedes method could not be performed.

Figure 4.

SEM micrographs of un-doped BLLW and 1% Nd3+-doped BLLW, as well as un-doped BLNW and 1% Nd3+-doped BLNW micro-ceramics (surface after disc polishing).

3.4. High-Resolution Low-Temperature Spectroscopy

3.4.1. Absorption Spectra at RT and 4.2 K

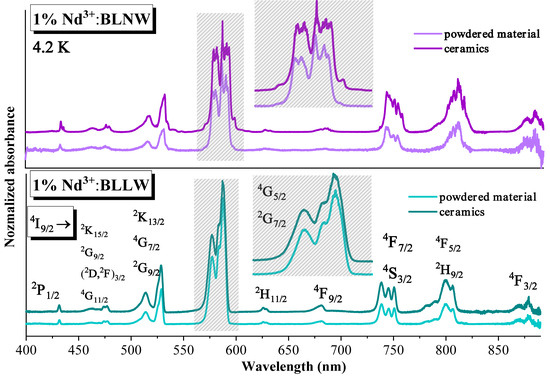

The spectroscopic properties of cubic 1% Nd3+-doped BLLW and BLNW sintered ceramics were investigated using UV-Vis-NIR absorption spectroscopy. Figure 5 presents absorption spectra registered at 4.2 K for 1% Nd3+-doped BLLW and BLNW micro-powders (initial materials) and sintered ceramics. The absorption lines in the 400–900 nm spectral range correspond to parity-forbidden intra-configuration 4f3 transitions originating from the 4I9/2 ground state to the appropriate excited states. For both sample types, the absorption bands are relatively broad, and the spectra remain similar. As for the micro-powdered samples, also here, reducing the temperature to 4.2 K results in only a slight narrowing of the absorption bandwidths [15]. This characteristic behavior is typical of disordered structures following our previous reports on other Nd3+-doped materials [12,13,16]. A detailed absorption spectroscopic study comparing BLLW and BLNW materials doped with Nd3+ ions was presented in our previous work [15]. Similarly, as observed in the powdered samples [15], the primary difference between the hosts is the more structured spectra recorded at 4.2 K for BLNW, particularly for the 4I9/2 → 4G5/2, 2G7/2 hypersensitive transitions, indicating a higher ordering in the structure in this sample.

Figure 5.

Absorption spectra recorded at 4.2 K for 1% Nd3+-doped BLLW and BLNW micro-powders (initial materials) and sintered ceramics.

3.4.2. Luminescence Spectra at RT and 77 K

Emission Under Non-Selective Excitation

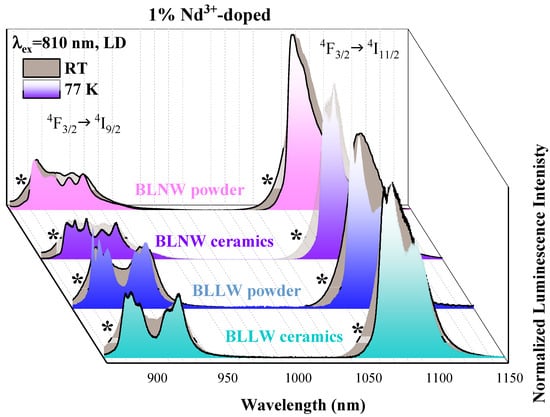

Figure 6 shows the luminescence spectra recorded at RT and 77 K under broad LD excitation at 810 nm for both initial materials and ceramics of 1% Nd3+-doped BLLW and BLNW. The spectra registered for the 4F3/2 → 4I9/2 and 4F3/2 → 4I11/2 transitions reveal similar trends for micro-powders and ceramics when comparing measurements at RT and 77 K. At 77 K, the emission bands exhibit a slight narrowing, similar to the case of absorption spectra. At this temperature, the emission from the R2 Stark level of the 4F3/2 manifold (marked by an asterisk in the spectra) vanishes.

Figure 6.

Luminescence spectra recorded at RT and 77 K for 1% Nd3+-doped BLNW and 1% Nd3+-doped BLLW micro-powders and ceramics under λex = 810 nm excitation of LD.

When comparing the spectra at 77 K for the BLLW samples, the micro-powdered sample provides better resolution of individual spectral components at 879, 884, 890, 909, and 917 nm than the ceramics with maxima at 880, 884, 889, 909, and 917 nm. Specifically, the 4F3/2 → 4I9/2 transition shows better resolved first two components, and the 4F3/2 → 4I11/2 transition displays well-defined maxima at 1063.5, 1068.5, and 1083 for powders and 1064, 1068, and 1086 for ceramics. Also, in this case, for powders, the first two components are better resolved.

In the case of BLNW, these samples show the opposite phenomenon. The bands of the ceramic sample exhibit better resolution, with well-defined maxima at 883, 889, 897, 907, and 917 nm for the 4F3/2→4I9/2 transition, and for powders at 882, 895, 907, and 917 nm. In turn, for the 4F3/2→4I11/2 transition for BLNW powders, the maxima are localized at 1063.5, 1068.5, and 1083 nm, while in ceramics, at 1064, 1068, and 1086 nm.

Emission Under Selective Excitation

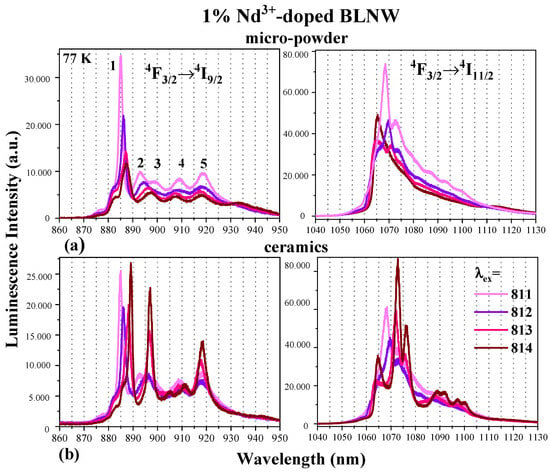

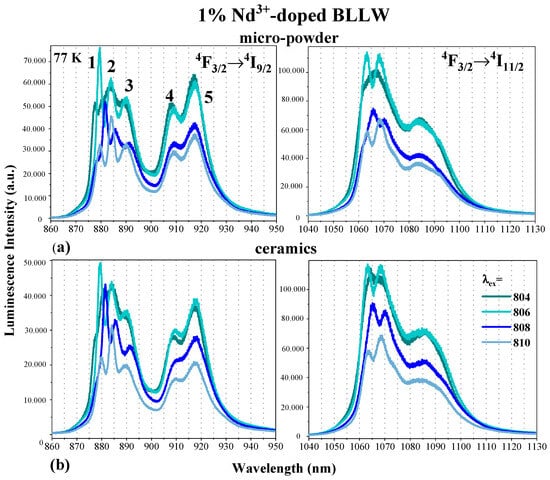

To thoroughly examine the presence of non-equivalent Nd3+ sites and compare the luminescence of powdered and ceramic BLLW and BLNW samples, OPO laser-excited emission measurements were performed on Nd3+-doped ceramics at 77 K. Among the recorded spectra across a wide range of laser excitation lines, only those showing the most noticeable differences are presented in this work.

Figure 7 presents the luminescence spectra corresponding to 4F3/2 → 4I9/2 and 4F3/2 → 4I11/2 transitions observed for Nd3+-doped BLNW micro-powders (a) and ceramics (b). Under 811 nm and 812 nm excitation, the spectral characteristics remain similar for ceramic and micro-powdered forms. The lines exhibit a slight shift with changes in the excitation line. However, under 813 nm and 814 nm excitation, the components with maxima at 889.1 nm, 897 nm, and 917 nm for the 4F3/2 → 4I9/2 transition, as well as at 1072.8 nm and 1076 nm for the 4F3/2 → 4I11/2 transition, are of much higher intensity. Similar spectral features of an intense, narrow additional line located at around 1071 nm (4F3/2 → 4I11/2) have also been previously observed for BLNW ceramics under broad LD excitation of 810 nm. To explore the cause of the enhanced emission, a detailed microscopic analysis was performed (see Figure S4). The ceramic micrographs reveal areas with slightly different morphology. EDS analysis at this location revealed a distinct elemental composition, with higher concentrations of Ba, La, and W and lower amounts of Na and O compared to other areas. This stays in agreement with the XRD analysis, which indicated the presence of a minor secondary phase, i.e., monoclinic BaLa2WO7 tungstate in 1% Nd3+-doped BLNW ceramics. Since La3+ ions in the monoclinic tungstate can be substituted by optically active Nd3+ ions, it is hypothesized that these additional luminescence lines arise from the incorporation of Nd3+ ions into the BaLa2WO7 phase. This phenomenon was not observed in BLLW ceramics (see Figure 8).

Figure 7.

Luminescence spectra recorded at 77 K for 1% Nd3+-doped BLNW micro-powders (a) and ceramics (b) under OPO laser excitation (λex = 811–814 nm) within the 4F3/2 → 4I9/2 (left) and 4F3/2 → 4I11/2 (right) transitions.

Figure 8.

Luminescence spectra recorded at 77 K for 1% Nd3+-doped BLLW micro-powders (a) and ceramics (b) under OPO laser excitation (λex = 811–814 nm) within the 4F3/2 → 4I9/2 (left) and 4F3/2 → 4I11/2 (right) transitions.

In powdered and ceramic BLLW, changing the selective excitation wavelength activates the different, non-equivalent Nd3+ sites. Consequently, a shift in the peak position, along with modifications in the contour and structure of the spectral bands, was detected. Furthermore, the absence of luminescence lines associated with tetragonal BaWO4, an impurity phase identified through XRD and SEM analysis, confirms that the optically active Nd3+ ions do not incorporate into the tetragonal structure.

The influence of varying excitation wavelengths on the luminescence properties of the Nd3+ ion in BLNW ceramics and micro-powders is analyzed in the spectra presented in Figure S5. This figure illustrates the 4F3/2 → 4I9/2 transition under excitation within the 811–820 nm range. For excitation lines of 811 nm, 812 nm, and within the range of 816–819, the spectral profiles of ceramics and micro-powders exhibit similarity. The peak positions remain consistent, highlighting optically active ions’ multisite character and non-homogeneous distribution. In ceramic samples, the Stark Z1 component appears noticeably narrower. On the contrary, excitation at 813–815 nm and 820 nm produces more complex spectra, featuring additional sharp emission lines linked to the presence of the monoclinic BaLa2WO7 phase.

Figure S6 illustrates the 4F3/2 → 4I11/2 transition, excited by a resonant line within the 876–889 nm range, corresponding to direct excitation into the 4F3/2 level for Nd3+-doped BLNW. Under excitation at 879 nm, 882 nm, and 885 nm, the spectral shape remains similar, maintaining coherence between ceramics and micro-powders, with ceramics showing enhanced peak resolution. In contrast, at other wavelengths within this range, specifically 876–879 nm and 886–889 nm, more complex spectral features arise, exhibiting additional emission lines likely associated with the previously mentioned monoclinic impurity phase. A distinct behavior appears to manifest in the Nd3+-doped BLLW sample.

A comparative analysis of the spectra for Nd3+-doped BLLW powders and ceramics, presented in Figure 8, shows a strong resemblance. The peak positions, overall spectral shape, and width remain consistent between micro-powders and ceramics when excited at 804, 806, 808, and 810 nm. This phenomenon has also been observed across various Nd3+-doped BLLW powdered samples as discussed in our previous articles [15,16].

In the Supplementary Materials of the article [16], luminescence spectra in the spectral range of the 4F3/2 → 4I11/2 transition for cubic Nd3+-doped BLLW and tetragonal 1% Nd3+-doped BaWO4 micro-crystalline samples at 77 K (λex = 806 nm of OPO laser) were presented. Based on this comparison, it can be concluded that in the tested samples, even if trace amounts of the BaWO4 phase are present as a contaminant in the Nd3+-doped BLLW ceramics, the Nd3+ ions are not incorporated into this phase. Instead, they preferentially occupy only the cubic phase.

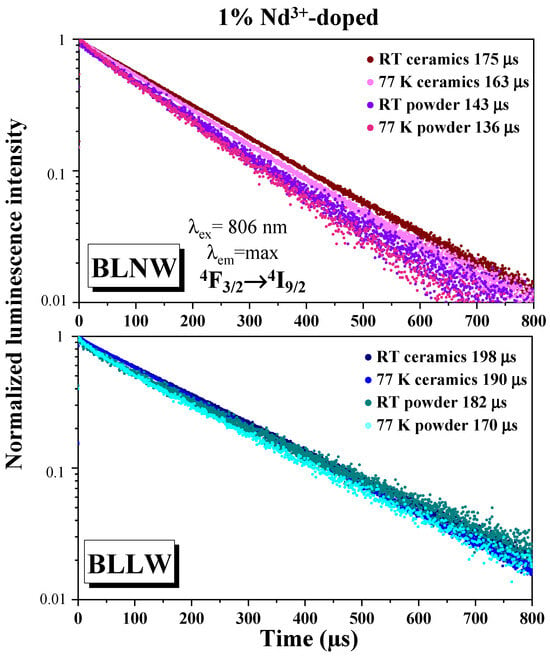

3.4.3. Excited State Dynamics of the Nd3+ Ion

The excited state dynamics of the Nd3+ ion in BLLW and BLNW micro-powders and ceramics were also investigated.

The measurements were conducted at RT and 77 K using a pulsed OPO laser with an excitation at 806 nm into the 4I9/2 → 4F5/2 + 2H9/2 transition, and the emission was monitored for the 4F3/2 → 4I9/2 transition. The decay curves presented in Figure 9 predominantly show a mono-exponential decay, except for the 1% Nd3+-doped BLLW powder measured at both RT and 77 K. In all cases, the ceramic samples exhibit a longer average integrated luminescence lifetime than micro-powders. For BLNW, the lifetime difference between ceramics and powders is 27 µs at 77 K and 32 µs at RT, whereas for BLLW, it is 20 µs at 77 K and 16 µs at RT. This behavior can be attributed to the larger surface area of the powders, which introduces more surface defects acting as recombination centers, resulting in shorter lifetimes. In contrast, ceramics have fewer grain boundaries, reduced light scattering due to their well-sintered nature, and longer charge carrier lifetimes. Similar discrepancies of a few percent in decay times between powders and ceramics have been reported for Nd3+:YAG [17], leading to an estimated uncertainty of about 10% in tail lifetimes.

Figure 9.

Luminescence decay curves recorded at RT and 77 K for 1% Nd3+-doped BLLW and BLNW micro-powders and ceramics.

As a result, the weak differences of the integrated lifetimes between 77K and RT, both for powders and ceramics, of about 10 μs, show that the radiative reabsorption is less significant than, for example, in the case of Nd3+-doped LuPO4 or YPO4 previously reported by our group [18]. As shown in Figure S7, which presents decay times for BLNW under different excitation wavelengths (804, 808, 810, 813, and 817 nm), the fluorescence lifetimes ranged from 155 to 104 µs. This study was important for determining the luminescence decay time at the emission maxima, helping to confirm the presence of Nd3+ ions incorporated into the monoclinic BaLa2WO7 phase, as discussed in the previous section. For excitation wavelengths of 813 nm and 814 nm, associated with emission lines characteristic of the monoclinic phase, the decay times were significantly shorter (133 µs and 104 µs, respectively) compared to the 163 µs observed for the emission at 806 nm, originating from the primary Nd3+ site in BLNW.

Additionally, excitation at 804, 808, and 810 nm yielded decay times between 155 and 140 µs, emphasizing the non-homogeneous distribution of Nd3+ ions within the cubic BLNW phase.

Analysis of decay times between powders and ceramics also shows that the lifetime increase in ceramics is more pronounced for BLNW than BLLW. SEM analysis shows that BLNW powders consist of larger, well-separated grains with a relatively high surface-to-volume ratio, which introduces more surface-related non-radiative recombination centers. Consequently, the corresponding ceramics—despite containing some intergranular gaps—exhibit a more substantial reduction in surface defects after sintering compared to BLLW, leading to a stronger lifetime enhancement. In contrast, BLLW powders already show smaller and more compact grains, resulting in fewer surface defects in the powdered state and therefore a less evident improvement upon densification. Furthermore, in BLNW ceramics, a minor fraction of Nd3+ ions occupies sites associated with the monoclinic BaLa2WO7 phase, as evidenced by the selective-excitation spectra. These sites exhibit longer intrinsic lifetimes, which additionally contributes to the larger overall increase observed for BLNW ceramics.

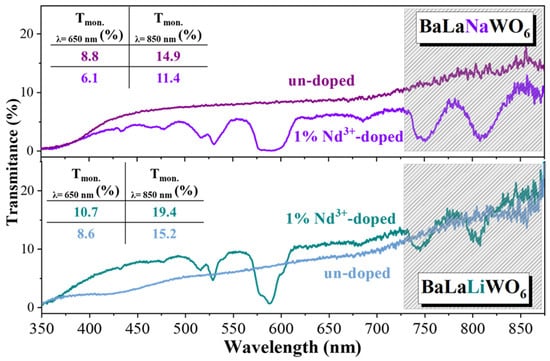

3.4.4. Total Forward Transmission (TFT) at RT for Sintered Micro-Ceramics

Figure 10 presents the TFT spectra recorded for un-doped and Nd3+-doped BLNW and BLLW micro-crystalline ceramics. Their low light transmittance is attributed to defects in the microstructure as well as the presence of a second phase manifested in all obtained ceramic bodies. The ceramics consist of micro-metric grain sizes with some residual intergranular porosity and show translucency.

Figure 10.

Total Forward Transmission (TFT) recorded for un-doped Nd3+-doped BLNW and BLLW micro-crystalline ceramics.

All samples show low transmittance across the 350–900 nm spectral range, primarily due to the presence of pores and secondary phase inclusions, while doping appears to have no significant effect. Higher magnification SEM images revealed that despite appearing well-compacted, the grains do not adhere tightly to one another, showing BLLW the free spaces between the grains and the gaps in the case of BLNW. Furthermore, for Nd3+-doped BLLW, the grains appear even more loosely packed, with visible connecting bridges between them. In the NIR region, light scattering is less prominent, resulting in similar transmission for both types of sintered bodies. The transmission values at λ = 650 and 850 nm are larger for un-doped BLNW (8.8 and 14.8%), while in the case of BLLW, they are larger for Nd3+-doped sample (10.7 and 19.4%).

To sum up, the best transmission was recorded for both un-doped BLNW and Nd3+-doped BLLW ceramics. Although these initial results are encouraging, further optimization of the sintering conditions and, most probably, the quality of the initial powder are necessary to enhance the quality of ceramics derived from both BLLW and BLNW.

To achieve higher transparency in the investigated tungstate ceramics, ongoing work is focused on optimizing the SPS parameters, in particular the sintering temperature profile, total sintering time, dwell time and application of multi-step sintering [19]. Further improvement is also anticipated through the preparation of finer and more homogeneous nano-powders, which should facilitate enhanced densification and reduce light-scattering defects. In addition, the introduction of selected sintering additives will be examined as a means of promoting grain growth control and minimizing residual porosity. These continued developments are expected to significantly improve the optical quality of the materials and support their assessment as a new class of transparent ceramics.

4. Conclusions

Given the very limited number of available transparent optical ceramics, this study presents the first successful fabrication of polycrystalline BLLW and BLNW cubic tungstate ceramics (s.g , No. 225, Z = 4) via the SPS method. Pure-phase, homogeneous micro-powders—both passive and Nd3+-doped—were synthesized by solid-state reaction and employed as starting materials. For the first time, these tungstate compounds, previously known only as micro-powders or single crystals, have been demonstrated in translucent ceramic form, showing a certain level of visible light transmission. Minor secondary phases were detected in some specimens: BLNW exhibited traces of a monoclinic BaLa2WO7 phase, while BLLW showed weak reflections of BaWO4 in 1% Nd3+-doped ceramics, whereas the un-doped BLLW ceramics appeared phase-pure. SEM analysis revealed larger grains in BLNW (3.9–33.4 µm) compared to BLLW (1.5–7.4 µm) and exposed morphological defects limiting optical transparency. Despite these challenges, the spectroscopic studies highlight the strong potential of these novel ceramics. Nd3+ ions were confirmed to occupy non-equivalent lattice sites, with additional site-selective luminescence observed in BLNW due to the monoclinic BaLa2WO7 phase. Luminescence decay measurements further revealed longer lifetimes in ceramics compared to powders, suggesting reduced surface defect effects.

Importantly, the comparative microstructural and spectroscopic analysis indicates that BLLW provides a more favorable host environment for Nd3+ than BLNW. BLLW ceramics exhibit smaller and more compact grains, fewer intergranular gaps, and a reduced contribution of secondary phases, correlating with longer 4F3/2 lifetimes and more homogeneous Nd3+ emission. In contrast, BLNW shows stronger multisite behavior and additional emission components arising from the monoclinic BaLa2WO7 impurity phase. These findings suggest that Nd3+ ions experience a less perturbed crystalline environment in BLLW, making it the more promising host among the two investigated tungstates.

In summary, this work establishes BLLW and BLNW as a new family of transparent ceramics with a flexible structural framework suitable for incorporating optically active ions. While current transparency is limited by processing-related defects, the successful demonstration of these materials in ceramic form marks a significant advance in the field and provides a platform for further optimization toward high-performance optical ceramics.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ceramics8040155/s1, Figure S1, SEM micrographs of un-doped and 1% Nd3+-doped BLLW and BLNW micropowders obtained using the solid-state reaction method; Figure S2, SEM micrographs of 1% Nd3+-doped BLLW and 1% Nd3+-doped BLNW micro-ceramics (surface after disc polishing); Figure S3, SEM micrographs of un-doped BLLW and 1% Nd3+-doped BLLW surface and cross-section after disc polishing; Figure S4, SEM images of the overall cross-section of 1% Nd3+-doped BLNW ceramic with EDS analysis of elements (right); Figure S5, Normalized luminescence spectra recorded at 77 K for 1% Nd3+-doped BLNW micro-powders and ceramics under OPO laser excitation lines in the range of λex = 811–820 nm within the 4F3/2 → 4I9/2 transition; Figure S6, Normalized luminescence spectra recorded at 77 K for 1% Nd3+-doped BLNW micro-powders and ceramics under OPO laser excitation lines in the range of λex = 876–889 nm within the 4F3/2 → 4I11/2 transition; Figure S7, Luminescence decay curves collected for 1% Nd3+-doped BLNW ceramics at 77 K for 802–817 excitation lines of the OPO laser in the range of 4F3/2 → 4I9/2 transition.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.A.P., S.C., V.G., G.F., Y.G., G.B. and M.G.; Data curation, K.A.P., S.C., M.S., E.T. and M.G.; Formal analysis, K.A.P., S.C., M.S., K.R., E.T., V.G., G.F., Y.G., G.B. and M.G.; Funding acquisition, K.A.P. and M.G.; Investigation, K.A.P., S.C., M.S., K.R., E.T., V.G., G.F., Y.G., G.B. and M.G.; Methodology, M.S., S.C., V.G. and G.F.; Project administration, M.G.; Resources, S.C., V.G. and G.F.; Supervision, G.F., K.R., E.T., G.B. and M.G.; Validation, G.F. and G.B.; Visualization, K.A.P., M.S., and M.G.; Writing—original draft, K.A.P. and M.G.; Writing—review & editing, S.C., M.S., K.R., E.T., V.G., G.F., Y.G. and G.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science Centre Poland under the HARMONIA 8 project (UMO-2016/22/M/ST5/00546). This work was also developed within the scope of the project PHC POLONIUM from the Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange (NAWA) N1 PPN/BIL/2018/1/00214/U/00020 as well as the Ministries of Europe and Foreign Affairs (MEAE) and Higher Education, Research and Innovation (MESRI) N1 42883SM, for scientific exchange between Institute Light Matter (iLM), University Claude Bernard Lyon1 in France and Faculty of Chemistry, University of Wroclaw in Poland. K.A.P. would like to thank the Ministry of Science and Higher Education in Poland for Grant No. DWD/5/0361/2021 in the frame of the Implementation Doctorate Programme. The authors would like to thank Bérangère LESAINT for performing the ionic polishing.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Goldstein, A.; Krell, A.; Burshtein, Z. Transparent Ceramics: Materials, Engineering, and Applications; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-1-119-42949-4. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, A.; Krell, A. Transparent ceramics at 50: Progress made and further prospects. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2016, 99, 3173–3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikesue, A.; Aung, L.A. (Eds.) Processing of Ceramics: Breakthroughs in Optical Materials; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.F.; Zhang, J.; Luo, D.W.; Gu, F.; Tang, D.Y.; Dong, Z.L.; Tan, G.E.B.; Que, W.X.; Zhang, T.S.; Li, S.; et al. Transparent ceramics: Processing, materials and applications. Prog. Solid State Chem. 2013, 41, 20–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegadi, A.; Kolli, M.; Hamidouche, M.; Fantozzi, G. Transparent MgAl2O4 spinel fabricated by spark plasma sintering from commercial powders. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 18828–18835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussel, N.; Lallemant, L.; Chane-Ching, J.Y.; Guillemet-Fristch, G.; Durand, B.; Garnier, V.; Bonnefont, G.; Fantozzi, G.; Bonneau, L.; Trombert, S.; et al. Highly dense, transparent alpha-Al2O3 ceramics from ultrafine nanoparticles via a standard SPS sintering. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2013, 96, 1039–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frage, N.; Kalabukhov, S.; Sverdlov, N.; Ezersky, V.; Dariel, M.P. Densification of transparent yttrium aluminum garnet (YAG) by SPS processing. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2010, 30, 3331–3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epicier, T.; Boulon, G.; Zhao, W.; Guzik, M.; Jiang, B.; Ikesue, A.; Esposito, L. Spatial distribution of the Yb3+ rare earth ions in Y3Al5O12 and Y2O3 optical ceramics as analyzed by TEM. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 18221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toci, G.; Vannini, M.; Ciofini, M.; Lapucci, A.; Pirri, A.; Ito, A.; Goto, T.; Yoshikawa, A.; Ikesue, A.; Alombert-Goget, G.; et al. Nd3+-doped Lu2O3 transparent sesquioxide ceramics elaborated by the Spark Plasma Sintering (SPS) method. Part 2: First laser output results and comparison with Nd3+-doped Lu2O3 and Nd3+-Y2O3 ceramics elaborated by a conventional method. Opt. Mater. 2015, 41, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulon, G.; Guyot, Y.; Guzik, M.; Toci, G.; Pirri, A.; Patrizi, B.; Vannini, M.; Yoshikawa, A.; Kurosawa, S.; Ikesue, A. Specifics of spectroscopic features of Yb3+-doped Lu2O3 laser transparent ceramics. Phys. Status Solidi B 2022, 259, 2100521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hostasa, J.; Picelli, F.; Hribalova, S.; Necina, V. Sintering aids, their role and behaviour in the production of transparent ceramics. Open Ceram. 2021, 7, 100137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilk (Bieza), M.; Tomaszewicz, E.; Siczek, M.; Guyot, Y.; Boulon, G.; Guzik, M. The first characterization of cubic Nd3+-doped mixed La2MoWO9 in micro-crystalline powders and translucent micro-ceramics. J. Mater. Chem. C 2022, 10, 10083–10098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokop, K.A.; Siczek, M.; Tomaszewicz, E.; Rola, K.; Guyot, Y.; Boulon, G.; Guzik, M. Structural ordering studies of Nd3+ ion in cubic M3Y(PO4)3 (M = Sr2+ or Ba2+) perovskites. First translucent ceramics from micro-crystalline cubic powders. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 8042–8056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokop, K.A.; Cottrino, S.; Garnier, V.; Fantozzi, G.; Guyot, Y.; Boulon, G.; Guzik, M. Enhancing transparency in non-cubic calcium phosphate ceramics: Effect of starting powder, LiF doping, and spark plasma sintering parameters. Ceramics 2024, 7, 607–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokop, K.A.; Cottrino, S.; Garnier, V.; Fantozzi, G.; Siczek, M.; Rola, K.; Tomaszewicz, E.; Guyot, Y.; Boulon, G.; Guzik, M. Nd3+-activated cubic BaLaLiWO6 and BaLaNaWO6 tungstates: Structure, spectroscopy, and potential for optical ceramic hosts. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2025, 46, 117968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokop, K.A.; Tomaszewicz, E.; Siczek, M.; Guyot, Y.; Boulon, G.; Guzik, M. Unexpected dominant substitution of Ba2+ instead of La3+ in cubic Nd3+-doped BaLaLiWO6 perovskites. Acta Mater. 2024, 277, 120131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkle, L.D.; Dubinskii, M.; Schepler, K.L.; Hegde, S.M. Concentration quenching in fine-grained ceramic Nd:YAG. Opt. Express 2006, 14, 3893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawłόw, J.; Prokop, K.A.; Guzik, M.; Guyot, Y.; Boulon, G.; Cybinska, J. Nano/micro-powders of Nd3+-doped YPO4 and LuPO4 under structural and spectroscopic studies. An abnormal temporal behavior of f–f photoluminescence. J. Lumin. 2021, 236, 117997. [Google Scholar]

- Stanciu, G.; Voicu, F.; Brandus, C.-A.; Tihon, C.-E.; Hau, S.; Gheorghe, C.; Croitoru, G.; Gheorghe, L.; Dumitru, M. Enhancement of the laser emission efficiency of Yb:Y2O3 ceramics via multi-step sintering method fabrication. Opt. Mater. 2020, 109, 110411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).