Abstract

Environmentally friendly materials with superior structural, physical, optical, and shielding capabilities are of great technological importance and are continually being investigated. In this work, novel multicomponent borate glasses with the composition xTiO2-10BaO-5Al2O3-5WO3-20Bi2O3-(60-x) B2O3, where 0 ≤ x ≤ 15 mol%, were produced via the melt-quenching technique. The increase in TiO2 content results in a decrease in molar volume and a corresponding increase in density, indicating the formation of a compact, rigid, and mechanically hard glass network. Elastic constant measurements further confirmed this behavior. FTIR analysis confirms the transformation of BO3 to BO4 units, signifying improved network polymerization and structural stability. The prepared glasses exhibit an optical absorption edge in the visible region, demonstrating their strong ultraviolet light blocking capability. Incorporation of TiO2 leads to an increase in refractive index, optical basicity, and polarizability, and a decrease in the optical band gap and metallization number; all of these suggest enhanced electron density and polarizability of the glass matrix. Radiation shielding properties were evaluated using Phy-X/PSD software. The outcomes illustrate that the Mass Attenuation Coefficient (MAC), Effective Atomic Number (Zeff), Linear Attenuation Coefficient (LAC) increase, while Mean Free Path (MFP) and Half Value Layer (HVL) decrease with increasing TiO2 at the expense of B2O3, confirming superior gamma-ray attenuation capability. Additionally, both TiO2-doped and undoped samples show higher fast neutron removal cross sections (FNRCS) compared to several commercial glasses and concrete materials. Overall, the incorporation of TiO2 significantly enhances the optical performance and radiation-shielding efficiency of the environmentally friendly glass system, making these potential candidates for advanced photonic devices and radiation-shielding applications.

1. Introduction

Since radiation is a component of our everyday existence, life and radiation cannot be separated. Humans constantly encounter background radiation from the sun and naturally existing radioactive elements in the soil. Because of developments in elementary particle accelerators, nuclear power plants, medicine, agriculture, academic research, and industry, it is currently challenging to prevent excessive emissions of ionizing electromagnetic radiation into the environment [1]. Thus, it is important to carefully examine the likelihood of producing free radicals at various energies that might damage biological cells. Skin burns or acute radiation syndrome are examples of negative health consequences that can happen when ionizing radiation doses increase above specific ideal values [2].

Due to the detrimental effects of radiation on the environment, several scientists and researchers are developing radiation shielding and protective materials [3,4,5]. Products categorized as radiation shielding materials should generally serve as a barrier between humans or the environment and sources of radiation in order to reduce the quantity of radiation to acceptable or approved averages [4,5].

In recent decades, lead has been widely used as a substance to guard against photons. Its mechanical and physical attributes, such as high density and comparatively low cost, make it a valuable shielding material [4,5]. However, lead has a number of drawbacks, including toxicity, hefty weight, chemical instability, inflexibility, and secondary radiation generation. As a result, current research has concentrated on identifying a viable substitute shielding material that outperforms lead. Therefore, it is essential to replace Pb with a non-toxic shielding medium. Materials engineers and shielding material developers now aim to create inexpensive, lightweight, flexible, and environmentally friendly gamma-ray protective materials [6,7]. For this reason, materials with large atomic numbers, refractive indices, and densities were thought to be appropriate. Even though ceramics, granite, concrete, polymers, and alloys were often used, their limited application and opaque nature prevented them from being widely used [3,4,8]. Therefore, for the purpose of absorbing ionizing radiation in different forms, such as neutrons and gamma rays, glasses and other high-transparency materials are preferred over opaque ones, such as concrete. Glasses have the advantages of being inexpensive, transparent, and simple to make [8]. These characteristics make glass materials indispensable in our everyday lives since there are many products of glass that may be used for a variety of purposes [9]. Advances in glass manufacturing, chemical composition, and structural design have significantly expanded their utility. Because of the great potential of glass chemical structure, many glass systems have not yet been developed and studied for their related attributes and practical value [3,9].

The development of new glass systems inspires scientists and researchers to design innovative, cost-effective materials in a wide variety of shapes and sizes. Numerous glass formers, including silicates, borates, tellurite, and phosphates, have been extensively investigated in combination with different modifiers and intermediates for various technological applications [8,10,11]. Among these, borate glasses constitute one of the most important glass families due to their wide range of uses [2]. In recent years, borate glasses have attracted significant attention because of their diverse applications, including the encapsulation of radioactive waste, optical devices, radiation shielding materials, and household and laboratory glassware [11,12,13]. They are widely favored because of their versatility, high thermal stability, and low melting temperature. The robust borate glass network also serves as an excellent host for different ions, allowing the incorporation of various metal ions in adjustable concentrations [4]. The type and concentration of these dopants, such as heavy metal oxides or transition metals, can significantly enhance one or more properties of the glass.

With potential structural, mechanical, optical, and magnetic qualities that make them highly suitable for designing optical and shielding applications, transition metal oxides (TMOs) are equally important in the field of glass science [14,15]. One of the members of the 3D transition metal oxides, titanium dioxide (TiO2), is regarded as a valuable glass constituent in glasses because of its many benefits, including chemical and physical properties, increased stability, catalytic activities, and oxidative powers, as well as its ease of manufacturing and low cost [16]. Because of its great transparency, optical qualities, non-toxicity, and photo stability against light, it is also very competitive [16,17,18]. TiO2 glasses exhibit considerable potential as nonlinear optical systems because the nonlinear polarizabilities of titanium ions are more significantly influenced by their empty or unfilled d-shells. By slowing down the process of crystallization, TiO2 dopant aids in maintaining the amorphous state of materials [16,17,18,19]. The capacity of these glasses to absorb UV light is strong [19]. TiO2 enhances the mechanical properties, chemical durability, thermal stability, and refractive index of glass, thereby improving its overall resilience to external influences [16,17,18,19]. Additionally, it enhances its dielectric and thermal stability, which makes it appropriate for use in biological, electronics, and optical applications [19,20,21].

TiO2-based borate glasses have recently become the subject of several studies that have captivated the interest of various researchers. Several recent investigations highlight their potential in diverse technological fields. Germanate glasses containing TiO2 were investigated by M. Kuwik et al. for use in broadband amplifiers and NIR lasers [22]. TiO2-borate glasses have been suggested by M. Ezzeldien et al. as a promising candidate for visible-range photonic devices [23]. P. Mangthong et al. developed hybrid detectors for high-energy radiation applications using glasses coated with photosensitive TiO2 thin films [24]. Jianwei Gao et al. prepared TiO2-doped silicate glasses for photonic ceramic fuel cells applications [25]. M.I. Sayyed et al. effectively evaluated the radiation shielding performance of TiO2-modified borate glasses [26]. The biomedicinal applications of TiO2-containing glasses were explored by Sushil Patel and coworkers [27]. The usage of SrO-TeO2-TiO2-B2O3 glasses for LED applications was discovered by B. Srinivas [28]. The high-efficiency energy storage modification in BiFeO3 composite ceramics by using the BaO-TiO2-SiO2 glasses was examined by R. Montecillo [29]. WO3 and TiO2-containing glasses for optical lenses and fiber drawing applications were studied by N. Chanakya et al. [30].

Aluminum oxide (Al2O3) is another dominant ingredient in glass because it is less expensive and has qualities such as good strength and heat conductivity. Al2O3 addition to borate glasses or other materials improves optical properties, mechanical strength, thermal stability, chemical durability, and glass-forming ability [31,32,33,34] while also lowering non-bridging oxygens [35]. Due to their superior moisture resistance, Al2O3-based B2O3 glasses have been successfully utilized in a wide range of commercial and technological applications, including fuel cells [36], microwave cavities, space-precision mirror-blanks [37], photonics [38], and optoelectronics [39].

The importance of HMO (heavy metal oxide) glasses, especially Bi2O3, in influencing the composition and characteristics of glasses has been documented in a number of investigations [40,41]. Because of its high non-toxicity, high polarizability, refractive index, and wide transmission range, bismuth oxide is utilized in thermal and mechanical sensors, transparent nuclear radiation shielding windows, and electronic devices [40,41,42].

Computerized techniques such as MCNP-X and Phy-X/PSD [2,42] have been used to study the neutron and gamma shielding characteristics of several materials in recent times. The shielding factors, such as the MAC (μm), relative parameters, Mean Free Path (MFP), Effective Atomic Number (Zeff), Half-Value Layer (HVL), Tenth Value Layer (TVL), and Fast Neutron Removal Cross Section (ΣR), are evaluated using these recently created tools. Due to the opacity, toxicity, and limited durability of lead and concrete, recent research has shifted toward developing environmentally friendly, durable, transparent, and easily fabricated alternative materials. Because of their exceptional radiation shielding, optical, structural, infrared transparency, and nonlinear optical characteristics, heavy metal oxide B2O3 glasses meet these requirements.

The prime objective of this study is to analyze the impact of TiO2 on the elastic, optical, structural, and physical characteristics of a novel borate-based glass composition, as well as to evaluate its effectiveness for radiation shielding. Radiation protection parameters were obtained using Phy-X/PSD software [42]. The insertion of TiO2 into the glass environment leads to significant improvement in its structural, optical, and radiation shielding properties and demonstrates the potential of these TiO2–doped glasses as a promising candidate for photonic and advanced radiation-shielding technologies.

2. Materials and Methods

Glass compositions with the composition formula xTiO2-10BaO-5Al2O3-5WO3-20Bi2O3-(60-x) B2O3 with 0 ≤ x ≤ 15 mol% have been chosen for this investigation and manufactured using the melt-quenching process. The specific compositions of the prepared glasses are listed in Table 1. Briefly in preparation, to ensure homogeneity, the raw materials were thoroughly mixed in an agate mortar for 30–40 min. The mixture was then heated at 1200 °C for one hour until a clear, bubble-free melt was obtained. The molten mixture was rapidly quenched onto preheated stainless-steel plates. To relieve internal stresses formed during quenching and to improve the mechanical strength of the glass, the samples were subsequently annealed in a preheated furnace at above 440 °C for 4–5 h. Figure 1 shows the physical appearance of the manufactured glasses. The color varies from yellowish brown to dark brown as the TiO2 concentration increases.

Table 1.

Nominal composition (mole fraction) of different components used.

Figure 1.

Physical appearance of prepared glasses.

The experimental methods used to assess physical, structural, and optical parameters (such as XRD, optical absorption, FTIR, etc.) in this investigation are calculated by using the following methods [15].

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis: The amorphous/crystalline nature of samples is confirmed by X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis using a Pan Analytical X’Pert Pro X-ray diffractometer at a scanning rate of 4°/min with 2θ varied from 10 to 70°. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, the infrared transmission spectra of the glasses are measured at room temperature using a Fourier transform computerized infrared spectrometer (IR Affinity-1 Shimadzu spectrometer type) with wavenumbers ranging from 400 to 4000 cm−1. The prepared glasses are combined with KBr in a 1:100 ratio to create a fine powder from the mixture. The weighed mixtures are then compressed to 150 kg/cm2 to form uniform pellets. The infrared transmission measurements are made immediately after the pellets are ready.

UV-visible spectroscopy: At room temperature, the optical absorption spectra of samples in the 200–1100 nm range are recorded using a UV-visible spectrophotometer manufactured in Japan by Shimadzu.

Radiation shielding analysis: Phy-X/PSD software, which has been suggested by numerous researchers in the past and produced trustworthy results, is used to analyze the radiation shielding ability of these glasses [42].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

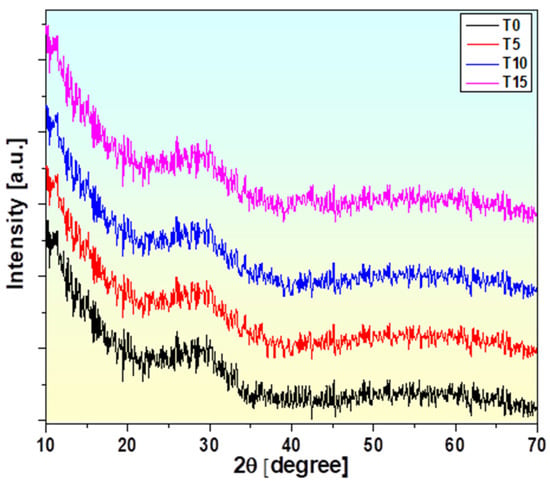

The XRD pattern of the selected glasses was seen at angles between 10° and 70°, as presented in Figure 2. The widespread scattering observed in the XRD pattern indicates the wide structural irregularity in these glasses [15,30]. The amorphous state of manufactured glasses is reflected by the non-appearance of sharp peaks and the occurrence of a widespread halo.

Figure 2.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of glass samples with x = 0, 5, 10, and 15 mol% of TiO2.

3.2. Physical Properties

Table 2 evaluates and illustrates the different physical characteristics of the glasses under study. It has been noted that altering the TiO2 content of glasses also alters these characteristics. The different relations are used to estimate the physical parameters as mentioned in Table 4. Density is a useful physical characteristic of any solid substance that provides insightful information. It is a straightforward and practical method for investigating structural solidity, changes in the network of glass geometrical configurations, and changes in tandem with variations in glass composition [43]. Density can also be used to detect the establishment of interstitial sites. It is influenced by the compactness or structural softness [44]. It illustrates the arrangement of ions and ionic groups inside the glass network [45].

Table 2.

Physical parameters.

The findings showed that the density (ρ) of glasses rose significantly from 4.95 g/cm3 to 5.61 g/cm3 when the amount of TiO2 in the glass system increased. This increase in density in glass might be the result of heavier oxide (TiO2) being substituted at the expense of lighter oxide (B2O3) [45]. The structural alterations in boron coordination in the glass network may also be explained by an increase in density with TiO2 concentrations. Many oxygen ions are accessible in the glass configuration due to the inclusion of transition metal oxide concentrations [46]. Three coordinate boron units [BO3] are changed into four coordinate boron units [BO4] with the aid of these oxygen ions [46]. Compared to the symmetric [BO3] triangle units, the tetrahedral [BO4] units are much denser [46]. Another factor contributing to the higher density of samples T3–T5 is the production of the B-O-Ti bond in the borate system [47], which improves the glass.

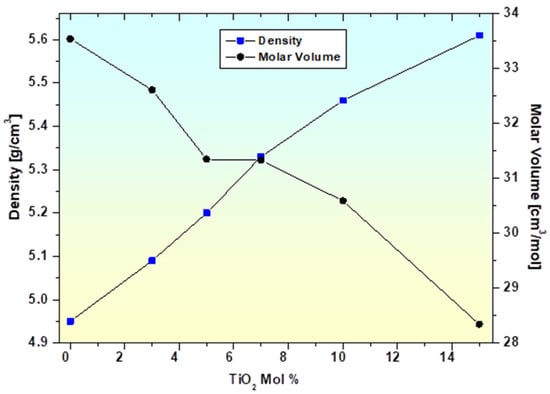

The molar volume (Vm) was crucial in determining the stiffness and compression of the glass. A reduction in molar volume from 33.54 to 28.34 cm3/mol and a conforming increase in density suggested that the addition of TiO2 had altered the structural characteristics. Hence, it is evident that a reduction in bond length, or the interatomic spacing between glass atoms, leads to a compression of the glass structure [45].

Figure 3 shows the variation in density and molar volume as the TiO2 concentration increases. The glass becomes stiffer and less prone to deformation [48] as Vm decreases and ρ increases because the glasses are packed closer together, creating greater intermolecular forces [48,49]. Average boron-boron separation <dB-B> [44], inter-nuclear distance (ri) [48], polaron radius (rp) [49], titanium ion concentration (N) [49], and field strength (F) [48,49] are determined using the expressions shown in Table 4 to have a better understanding of the compactness of the glasses. It shows that when the amount of TiO2 increases, the value of <dB-B> steadily decreases (0.411–0.350 nm). This decrease in <dB-B> indicates the network’s compactness [44], which is probably the result of densification [44] and structural changes brought on by the presence of titanium ions in the glass system. Physical characteristics of the material, such as molar volume and glass density, alter as a result.

Figure 3.

Variation in density and molar volume with mol% of TiO2 in glasses.

It is observed that, with increasing TiO2 content, the polaron radius decreases from 1.057 Å to 0.590 Å, the interatomic distance (ri) steadily decreases from 2.623 Å to 1.464 Å, and the ion concentration (N) increases from 5.540 to 31.876. The field strength (F), ranging from 1.969 to 6.320 cm−2, is enhanced by the increase in N from 5.540 to 31.876 ions/cm3 and the decrease in interatomic distance and polaron radius. These changes indicate restructuring the network of glass and a corresponding increase in the compactness of the glass matrix [48,49].

To achieve a better understanding, the other crucial parameters, i.e., OPD and molar volume (V0) of the glasses, are computed using the relation shown in Table 4 by changing the ratios of TiO2 and B2O3. OPD and V0 results show opposing patterns, with OPD increasing and V0 declining. The inclusion of TiO2, which improves the structure’s connectivity and stiffness by promoting structural compactness through stronger bridging B-O connections in the borate glass network [49], is the reason for the increase in OPD and drop in V0. It is also attributed to the decline of non-bridging oxygens (NBOs) that make the glasses more tightened [49]. Network density and bond distribution change in tandem with a decrease in B2O3 concentration and an increase in TiO2 content.

Further, the equations in Table 4 are used to achieve the average coordination number (m) and bond density (nb) [50]. It has been discovered that the addition of titanium oxide raises the glass samples’ average coordination number. [BO4] groups in glass networks are the result of bridging oxygens gradually rising in response to increased TiO2 concentration, which modifies the glass structure [44].

The bond density (nb) is impacted by the addition of TiO2. The data obtained indicates that the number of bonds per unit volume increases with the amount of titanium. By forming a link between titanium in glasses and the B–O bond vibration of [BO4] groups [44], the titanium ion serves as a form of modifier in the current glass system [44]. The increase in nb with an increase in TiO2 indicates a higher degree of bonding inside the glass, i.e., a more connected and compressed glass system [51]. All of these observations consistently confirm the role of TiO2 as a modifier in the current glass system.

3.3. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

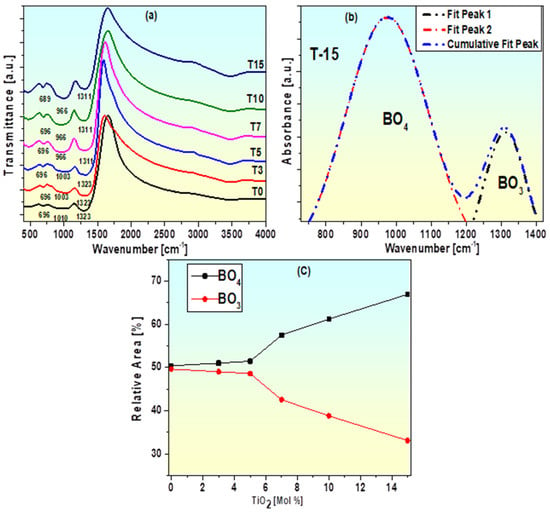

Non-destructive techniques, such as the use of glass infrared spectra, are helpful in gaining an understanding of the structural groupings of various elements in a glass system [15]. It is typically divided into three different sections. Because of B-O bond stretching of [BO3] units, the first zone spans from 1200 to 1600 cm−1; B-O stretching of [BO4] units causes the second region to extend from 800 to 1200 cm−1; and B-O-B bending vibration in the borate network causes the third region to lie approximately at 700 cm−1 [51,52,53].

Figure 4a shows the infrared transmission spectra of borate glasses doped with TiO2, representing the bands as large, medium, weak, and wide. Titanium oxide can contribute as a network former with tetrahedral [TiO4] units at low frequencies 400–500 cm−1 and participates as a glass network modifier with octahedral [TiO6] units and shows bending vibrations attributed to Ti–O–Ti bonds along with B–O–B bonds at frequencies ≈ 600–700 cm−1 [54,55]. The bending vibration of the bridging oxygen atoms in the B-O-B bond is represented by a band located at 696 cm−1 [15,51,52,53]. The change in intensity of this bond may be due to the joint presence of stretching vibrations of the metal–oxygen bond (Ti-O) of the [TiO6] unit of titanium and bending modes of the B–O-B bonds [54,55]. The broad band in sample T1, which is centered at 1323 cm−1, is caused by the symmetric stretching vibration of the B-O bond in [BO3] units [53]. The intensity of this band diminishes as the TiO2 content increases. This occurs when the glass system experiences an increase in tetrahedral [BO4] units and a reduction in trigonal [BO3] units [56]. Additionally, the vibration of stretching of the B-O bond in [BO4] tetrahedral units is attributed to the band about 1010 cm−1 in sample T0 that is visible in all samples [57,58]. In samples T0 to T15, as the TiO2 concentration increases, the intensity of this band has been seen to increase gradually and move to the lower wavenumber side (1010 to 966 cm−1) in other samples [57,58]. This is solely a result of the combined existence of [BO4] and Ti-O stretching vibrations of [TiO4] groups [44,57,58]. As the TiO2 content rises, peak locations and intensities are changed, indicating structural alterations in the glass network, such as variations in bond length [56]. As a result, the content of tetrahedral [BO4] units increases in tandem with the titanium concentration. Titanium’s modifying behavior in the prepared glasses is demonstrated by this outcome. In order to develop more precise evidence about the structural alterations (structural groups in the samples), accompanied with the TiO2 addition, the experimental perceived bands are exposed to deconvolution. Figure 4b demonstrates the outcomes of the deconvolution for sample T-15. The part of 3 and 4-fold coordinated boron is assessed using the relative peak areas of trigonal and tetrahedral boron groups that are separated by Gaussian deconvolution [52,53]. This is predictable as follows [53,56]:

where A3 is the area of [BO3] components, calculated in the range (1200–1600 cm−1), and A4 symbolizes the area of [BO4] components, calculated in the range (800–1200 cm−1).

Figure 4.

(a) FTIR spectra of TiO2 doped BaO-Al2O3-WO3-Bi2O3-B2O3 glasses (b) Deconvolution of FTIR spectra of T15sample. (c) Dependence of the fraction of BO3 and BO4 units on the spectra of the TiO2 mol% sample.

Usually, the relative area of a specified band can reflect the quantity of structural groups connected with that band, so the relative alteration of the area of [BO3] and [BO4] groups can be linked with the [BO3] ↔ [BO4] conversion in the glass network. It is established that by increasing the TiO2 content, the content of [BO4] units upsurges, which suggests the modifier role of TiO2. The variation in the ratios and on titanium content is presented in Figure 4c. It is observed that the ratio escalates and declines by increasing TiO2 concentration revealing the conversion of [BO3] to [BO4] units. Figure 4c makes it evident that more BO4 groups develop in the glass network at greater titanium concentrations.

3.4. Optical Characteristics

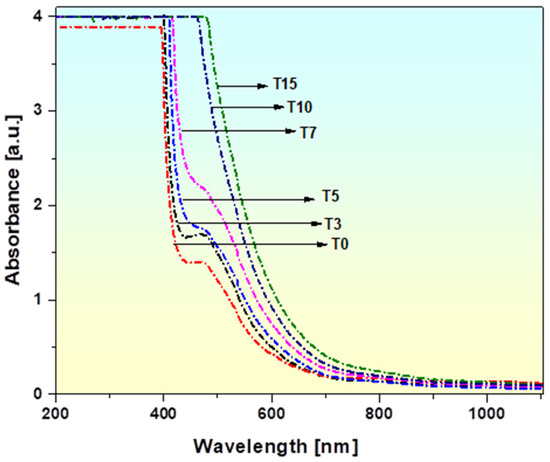

Figure 5 displays the optical absorption spectra of TiO2-doped borate glasses measured between 200 and 900 nm. The figure shows that each glass sample’s absorption edge can be recognized, and there is a certain cut-off wavelength for every glass sample. It is evident from the substitution of TiO2 that the absorption edge of the glass samples under study has consistently shifted towards a higher photon wavelength, which causes a redshift in the ultraviolet absorption properties or shifting of transitions to higher wavelengths [13,59]. This indicates that the TiO2 concentration influences the absorption edge [59]. Additionally, a noticeable change in the glass color was observed as the TiO2 concentration increased, gradually shifting from light yellow brown to reddish-brown as shown in Figure 1. The increase in bridging oxygens (BOs), which promotes the formation of BO4 units, causes the cut-off wavelength to shift from 428 to 636 nm [13,59,60]. When TiO2 is added to the glassy composition, the shift in the absorption edge towards a high wavenumber is likewise associated with changes in the density/molar volume and oxygen packing density. The current composition of the glass sample can be utilized to shield people from ultraviolet radiation because of the existence of a UV edge in the visible band (428 to 636 nm) [61]. The amorphous nature of the produced glasses is characterized by their broad optical absorption edges [62]. Additionally, it has been shown that sample T0 exhibits an absorption band at around 464 nm that may be due to the presence of Bi2O3 [63,64] and that the strength of this band decreases as the TiO2 concentration increases (0–7% in samples T5 and T7). This band disappears in samples T10 and T15 as the titanium content reaches 15 mol%. This might be because of titanium ion bonding, which influences the manufacturing process of these glasses.

Figure 5.

UV–Visible absorption spectra of TiO2-doped BaO-Al2O3-WO3-Bi2O3-B2O3 glasses.

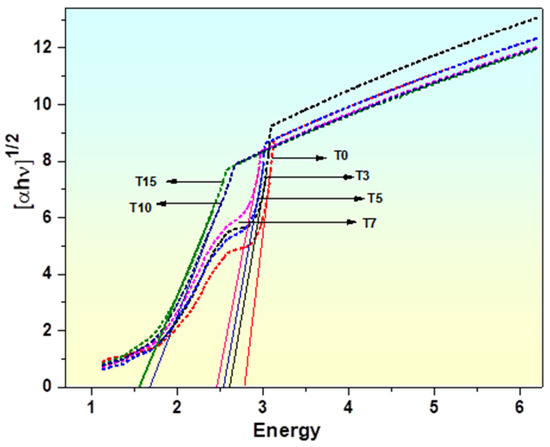

The Tauc plot between (αhv)½ and energy (hv), as shown in Figure 6, is used to determine the energy band gap of various glasses. As can be observed from Figure 4 and Table 3, the indirect optical bandgap Eg for the glass with the greater titanium content continually decreases, shifting and decreasing from 2.78 eV to 1.55 eV. Changes in the glass structure are responsible for the decline in Eg values as the concentration of TiO2 increases. The reasons for the contraction of the energy gap are:

Figure 6.

Tauc’s plot for energy gaps for BaO-Al2O3-WO3-Bi2O3-B2O3doped with TiO2.

Table 3.

Optical parameters.

(a) The change of BO3 to BO4 groups in the glassy matrix: Compared to trigonal BO3 groups, the tetrahedral BO4 groups are more likely to form a glass system with a stronger link. This is because borate’s tetrahedral [BO4] components are significantly denser than its [BO3] groups; as a result, the glassware network’s connectedness has improved [65,66].

(b) Compared to the other components of glasses, Al-O (511 KJ/mol), Ba-O (561.19 KJ/mol), and Bi-O (337.2 KCal/mol), the bond strength of B-O (808.7 KJ/mol) and Ti-O (672.4 Kcal/mol) is greater.

(c) The substitution of the higher atomic weight TiO2 (79.87 g/cm3) for the lower atomic weight B2O3 (69.62 g/cm3) and the stronger polarizing power of titanium ions (0.184 Å3) relative to boron ions (0.002 Å3).

As shown in Table 3, the band gap values of the specified glasses are then used to compute other optical characteristics such as dielectric constant (ε), refractive index (n) [67], optical electronegativity (χe), electronic polarisability (αe), and optical basicity (Λ) [62]. One of the most important characteristics for determining the materials’ importance in optical applications is the refractive index (n). It is impacted by the oxides that make up the glass composition, the polarisability of the cations, and the way light interacts with the electrons of the elements that constitute the glass [62,66]. It was observed that when TiO2 concentrations are raised, dielectric constant (ε) and refractive index (n) rose from 2.46 to 2.96 and from 6.047 to 8.776, respectively. A new localisation state is created when defects (donor centers) occur in the glass lattice, which is implied by the increase in n, directly related to the density. More ionic bonds are formed as a result of the formation, and these bonds have higher polarisability, which raises n values [68]. The resulting n is thought to be high, suggesting that the glasses under examination may be used in a variety of optical systems. The development of conductive three-dimensional networks inside the structure of glass and the impact of interfacial polarization are shown by the increasing tendency of the dielectric constant (ε). Equations as mentioned in Table 4 are used to compute the transmission coefficient (T) and reflection loss (R) [67]. Greater dopant concentrations result in greater R values, which may be explained by the larger n values. There is an inverse relationship between the transmission coefficient and reflection loss, i.e., a decrease in T results in an increase in the R value of glasses. This pattern implies the ionic nature of the prepared glass series.

The optical electronegativity (χe) decreases from 0.747 to 0.417 as the concentration of TiO2 doping enhances with the mol% of TiO2. This decline implies that the glass samples become more electron-donating as doping levels increase, which might affect their chemical reactivity and electromagnetic radiation interaction [68]. A change towards improved characteristics of the donor in the glass network is suggested by a lower χe, which generally indicates the material’s stronger tendency to donate electrons [69]. At the same time, the electronic polarizability (αe) measures how easily an external electric field may deform the electron cloud surrounding atoms or ions in the glass matrix [15,70]. When seen in Table 3, αe also shows a discernible increase from 2.828 to 3.125 when the concentration of dopant increases. This increase indicates that the glass structure becomes more polarizable, suggesting that the addition of dopants creates an electrical environment that is more easily deformed. Such behavior can significantly influence the material’s optical properties, including its dielectric constant and refractive index.

Optical basicity (Λ) is another crucial metric that may be evaluated using the relation provided in the literature [62]. It has been demonstrated that basicity is an essential component helpful in determining a glass system’s qualities prior to using the glass in a variety of applications. The shrinkage of the energy gap and the shifting of the absorption edge of the glasses may also be explained by the optical basicity result displayed in Table 3. The capacity of the oxygens in the glass system to donate electrons is known as optical basicity [71], and it is significantly impacted by changes in electronic polarisability. The addition of TiO2 greatly increases the optical basicity value (1.327 to 1.492) (Table 3). The higher optical basicity value indicates that oxide ions are able to transmit electrons with negative charges to the nearby cations [62,71]. Due to the substitution of B2O3 for TiO2 ions, these components help to raise the Λ value of glasses, which shows the creation of an ionic bond [72].

3.5. Metallisation Criteria

The material’s metal or non-metal status is usually determined by applying the metallisation criteria (M) [73]. It serves as a sign of the material composition that is approved for transfer into semiconductors, metals, or insulators. A formula provided elsewhere is used to compute the material’s Eg values, which determine M [74].

Basically, a material is categorized as an insulator when M has a big value nearby one and as a metal when M approaches zero [74]. Table 3 shows the M findings in our produced glasses, which range from 0.373 to 0.278. Because the M values for the prepared glasses are less than one, these results confirm the non-metallic character of the glasses [62,68,75]. However, the metallisation criteria’s declining trend suggests that the addition of TiO2, a transition metal oxide modifier, is progressively increasing the metallic behavior of the glasses that are created. The valence and conduction bands expand as a result of this declining development in M, which lowers the band gap and raises the glasses’ refractive index (n) [75]. These results therefore support the use of these glasses in new applications involving nonlinear optical materials, etc.

3.6. Elastic Properties

To evaluate the rigidity and compactness of the prepared glasses, it is important to correlate the band-gap energy and density results with the structural rigidity of the glass network. With the replacement of TiO2, the elastic characteristics of the produced glasses show significant variations between samples. Young’s modulus (E), Packing density (VT), Poisson’s ratio (σ), bulk modulus (K), shear modulus (G), and hardness (H) are among the essential elastic parameters that are theoretically evaluated using the M.M. model [76,77]. Table 5 displays the results for these characteristics. VT increases from 0.631 for the undoped sample T0 to 0.713 for the sample T15, which has the greatest titanium oxide level. With increased TiO2 incorporation, the glass matrix’s stiffness and rigidity gradually improve, as seen by this steady increase in VT [78]. The incorporation of TiO2, which results in denser atomic packing and a more robust glass network, can explain the improvement in VT. A stronger bond is produced by the presence of TiO2 ions, which have a higher atomic number than B2O3 [79]. The rise in VT is consistent with the observed increase in density and OPD.

Glass network composition and cross-link dimensionality are directly correlated with Poisson ratio parameters [79]. As demonstrated in Table 5, the inclusion of TiO2 values causes the Poisson’s ratio to increase from 0.280 to 0.305 for these glass samples. These glasses exhibit somewhat more elastic behavior, which enables them to distribute applied stress more uniformly across the glass network, as seen by the noticeably higher Poisson’s ratio values [80].

Table 4.

Different equations of physical, optical, and elastic parameters.

Table 4.

Different equations of physical, optical, and elastic parameters.

| Parameter | Formula |

|---|---|

| Density (ρ) [44] | |

| Molar Volume (Vm) [44] | |

| Average boron–boron separation [44] | |

| Molar volume of Oxygen [44] | |

| Oxygen Packing Density [44] | |

| Bond Density (nb) [44] | |

| Inter nuclear distance ri (Å) [48] | |

| Field strength (F) [48,49] | |

| Polaron radius rp (Å) [49] | |

| Optical Electronegativity (χ) [62] | χ = 0.2688 Eg |

| Electronic Polarizability (αe) [62] | −0.9*χ + 3.5 |

| Basicity (ΛTh) [62] | ΛTh = −χ*0.5 + 1.7 |

| Refractive index [67] | |

| Dielectric constant (ε) [67] | ε = n2 |

| Reflection Loss (R) [67] | |

| Transmission Coefficient (T) [67] | |

| Young’s Modulus of Elasticity (E) [76,77,78] | E = 83.6VTΣGixi |

| Modulus of Compressibility (K) [76,77,78] | |

| Modulus of Elasticity in Shear (G) [76,77,78] | |

| Poisson ratio (σ) [78,79] | |

| Packing Density (VT) [78,79] |

Table 5.

Packing Density (VT), Poisson ratio (σ), Young’s Modulus of Elasticity (E), Modulus of Compressibility (K), Modulus of Elasticity in Shear (G), and Vickers Hardness Number (H) of the glass samples.

Table 5.

Packing Density (VT), Poisson ratio (σ), Young’s Modulus of Elasticity (E), Modulus of Compressibility (K), Modulus of Elasticity in Shear (G), and Vickers Hardness Number (H) of the glass samples.

| Glass | Packing Density (VT) | Poisson Ratio (σ) | Young’s Modulus of Elasticity (E) (GPa) | Modulus of Compressibility (K) (GPa) | Modulus of Elasticity in Shear (G) (GPa) | Vickers Hardness Number (H) (Kg/mm2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | 0.631 | 0.280 | 84.61 | 64.02 | 33.06 | 791.93 |

| T3 | 0.643 | 0.281 | 86.57 | 66.76 | 33.72 | 814.08 |

| T5 | 0.665 | 0.291 | 89.77 | 71.60 | 34.77 | 854.20 |

| T7 | 0.661 | 0.290 | 89.51 | 71.00 | 34.70 | 847.89 |

| T10 | 0.671 | 0.293 | 91.22 | 73.46 | 35.28 | 866.52 |

| T15 | 0.713 | 0.305 | 97.58 | 83.52 | 37.38 | 945.53 |

Elastic constant results showed that higher TiO2 concentrations in the 0–15 mol% range led to higher elastic moduli for a range of parameters. In particular, the Young’s modulus, modulus of compressibility, and shear modulus rose by 84.61 to 97.58 GPa, 64.02 to 83.52 GPa, and 33.06 to 37.38 GPa, respectively. The role of TiO2 in bolstering structural compactness in this arrangement may be the reason for the improved modulus of compressibility, which specifically indicates a stronger resistance to compressive stresses. Increased stiffness is associated with higher shear modulus values, making it appropriate for load-bearing applications [79,81].

Glass Vickers hardness number (VHN) may be calculated using the formula provided by M. Yamane and J.D. Mackenzie [77]. The buildup of modifying oxide causes the VHN of glasses to increase, which is due to a decrease in the average bond length [78,79]. This can also be explained using the density/molar volume finding. The bond length between the oxide and modifier cation shrinks, which causes the molar volume to decrease as the density of synthetic glasses achieves enhanced [78,79,80]. As a result, the hardness of glasses would be improved. The increase in VHN, as seen in Table 5, is also supported by the findings, namely the reduction in inter-nuclear distance (ri) values and average boron-boron separation <dB-B> [79,80].

As the material becomes less compressible and more resistant to deformation, glasses with higher densities (and lower molar volumes) typically exhibit more compact structures, which in turn correlate with enhanced elastic properties [80,81]. The overall structure and stiffness of the glass network are impacted by the addition of TiO2, which modifies the coordinating environment of the components that make the glass [79]. Moreover, unlike other elements in the borate glass system, TiO2 strengthens the chemical interactions between Ti and O. The glass grows stiff and rigid as a result of the stronger interatomic interactions, therefore explaining the observed increase in elastic modulus. Ti-O, on the other hand, has a stronger dissociation energy than the other ingredients of the borate glass system. The observed enhancement in the elastic moduli of the glass systems is generally ascribed to these structural changes brought about by the presence of TiO2.

3.7. Radiation Shielding Parameters

3.7.1. Mass Attenuation Coefficient (MAC)

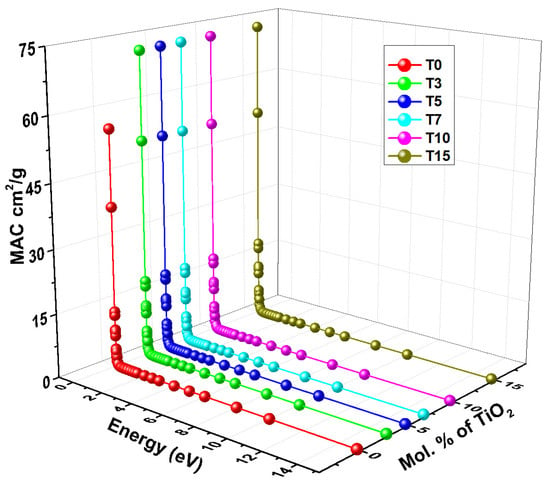

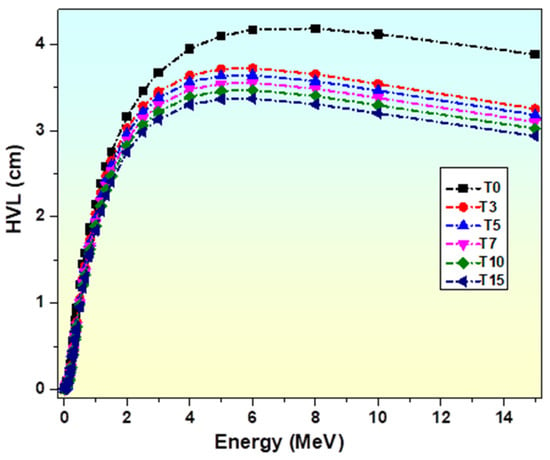

A material’s proficiency to attenuate (shield) X-rays or gamma rays is gauged by its mass attenuation coefficient (MAC) [11]. Additionally, it provides the possibility of interaction of a γ-photon with the material per unit mass; larger MAC values suggest that the material is more effective in protecting against γ or X-ray radiation [82]. At broad photon energies (0.015–15 MeV), Figure 7 displays the variation in MAC of the selected glasses of chemical composition xTiO2-10BaO-5Al2O3-5WO3-20Bi2O3-(60-x) B2O3; x = 0 to 15 mol%. MAC behavior is determined by photon interaction processes with matter. At Eγ of 0.015 MeV, the MAC of glasses rises from 55.61 to 72.41 cm2/g when titanium content is added, indicating a trend of T0 < T3 < T5 < T7 < T10 < T15, respectively.

Figure 7.

The variation in the Mass attenuation coefficient of glasses with energy and mol% of TiO2.

MAC values are influenced by photon energy; a considerable decrease in MAC values is observed when photon energy increases. Interestingly, the MAC values in the low-energy region, ranging from 0.015 to 0.1 MeV, significantly decrease due to the primary photoelectric absorption process. The MAC values are decreased in the mid-energy range region (0.15–1.5 MeV), which is where Compton scattering dominates. The pair production interaction is responsible for the constant MAC values that are seen in the high-energy range [4].

Furthermore, it has been noted that the glass samples’ chemical composition influences MAC values, with higher TiO2 concentrations translating into higher MAC values. Because of its higher TiO2 content, sample T15 has the greatest MAC value. Figure 7 illustrates how the MAC values grow when the TiO2 ratio is increased from 0 to 15 mol%. The MAC values are sorted as follows: T0 < T3 < T5 < T7 < T10 < T15, meaning that the T15 sample has the greatest MAC value due to its higher TiO2 content. It may be concluded that the capacity of samples to absorb photons is improved by the incorporation of TiO2.

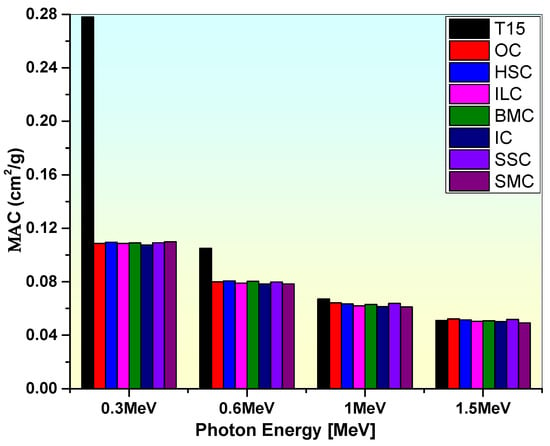

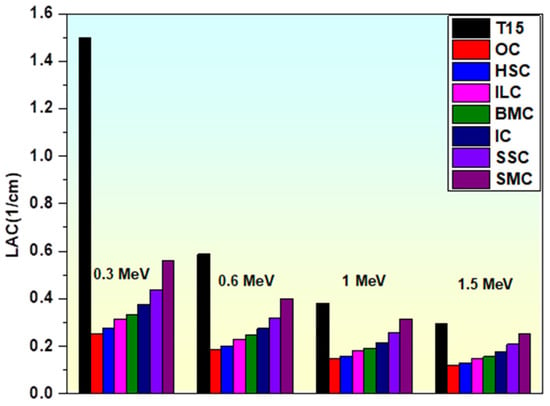

As shown in Figure 8, the MAC value of sample T15 is compared to commercial shielding concretes at energy levels of 0.3, 0.6, 1, and 1.5 MeV [83,84]. According to this comparison, TiO2 glass sample T15 has better attenuation capability than these shielding concretes, as seen by its higher MAC value.

Figure 8.

Comparison of the mass attenuation coefficient of the T15 sample with some commercial concretes.

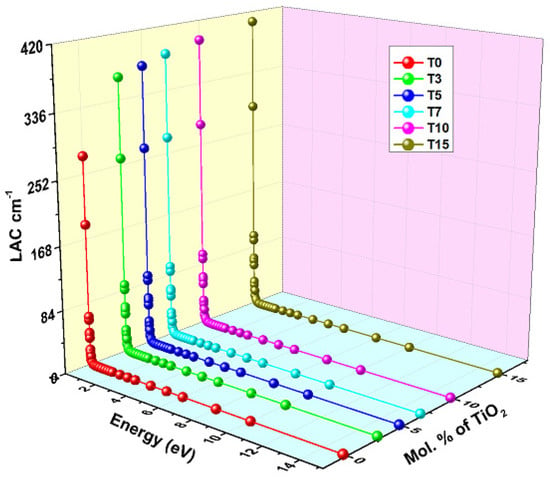

3.7.2. Linear Attenuation Coefficient (LAC)

The Phy-X program is used for evaluating the linear attenuation coefficient (LAC) values of TiO2-BaO-Al2O3-WO3-Bi2O3-B2O3 glasses made of varying amounts of TiO2 at photon energy between 0.015 and 15 MeV. As shown in Figure 9, the newly synthesized glasses’ LAC values are plotted against incident photon energy, which ranges from 0.015 to 15 MeV.

Figure 9.

Variation in the linear attenuation coefficient of glasses with energy and mol% of TiO2.

At low energies, the shielding effect of TiO2 is clearly evident. When TiO2 is added, the LAC increases from 275.27 to 406.23 cm−1. The LAC was observed to show an abrupt drop in the direction of the high-energy photon. The primary cause of this sharp drop in LAC in the lower region is photoelectric absorption. In general, for T15, T10, T7, T5, T3, and T0 at 0.015 MeV–15 MeV, LAC dropped from 406.23 to 0.236 cm−1, 393.847 to 0.229 cm−1, 383.575 to 0.224 cm−1, 373.636 to 0.218 cm−1, 365.160 to 0.213, and 275.267 to 0.179 cm−1, respectively. For the T15 to T0 samples, the LAC value at 0.3 MeV shifts from 1.562 to 1.106 cm−1. However, when compared to intermediate or higher energies, the impact of TiO2 is minimal; for example, at 6 MeV, the LAC decreases from 0.206 to 0.166 cm−1 as the TiO2 content increases from 0 to 15 mol%. The variation in the LAC with energy can be explained by considering the different types of photon-matter interactions that dominate in distinct energy regions. Compton scattering (CS) and pair production (PP) dominate in the medium- and high-energy ranges, respectively. Additionally, when photons undergo partial interactions in both PP and CS modes, the attenuation exhibits a gradual linear behavior [15].

To clearly illustrate the effect of TiO2 incorporation into the glass matrix, the LAC values are carefully examined at selected photon energies (0.3, 0.6, 1, and 1.5 MeV). By raising the LAC values, TiO2 increasing in effect from 0 to 15 mol%, and B2O3 decreasing in effect from 60 to 45 mol% improved the produced glasses’ shielding capacities. As the TiO2 concentration increases, the LAC values in the above-mentioned energies increase in Figure 9, causing the samples to follow the T0 < T3 < T5 < T7 < T10 < T15 trend from the perspective of LAC. The produced samples’ density and LAC are significantly increased by TiO2, which is regarded as one of the oxides with a higher gamma ray shielding. The LAC (μ) values of T15 are compared to commercial radiation shielding concretes OC, HSC, ILC, BMC, IC, SSC, and SMC at specific photon energies of 0.3, 0.6, 1, and 1.5 MeV (Figure 10) [85] to verify the shielding capability of the fabricated glasses. From this comparison, it can be inferred that the fabricated glasses exhibit higher LAC values than comparable commercial concretes, indicating superior gamma radiation shielding capabilities.

Figure 10.

Comparison of the linear attenuation coefficient of the T15 sample with commercial concretes.

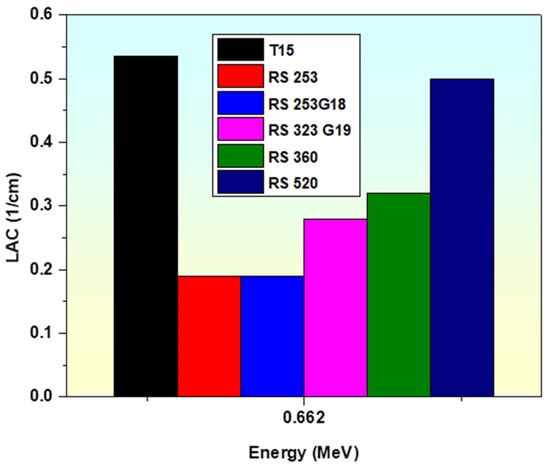

Furthermore, when compared to other commercial shielding glasses, such as RS-253, RS-253G18, RS-323 G19, RS-360, and RS-520 [86,87], the fabricated glass sample T15 at a γ-photon energy of 0.662 MeV has a greater LAC value than these commercial glasses, as observed in Figure 11. The comparison of LAC above supports the idea that our prepared glasses have a greater gamma shielding competence.

Figure 11.

Comparison of the linear attenuation coefficient of the T15 sample with commercial glasses.

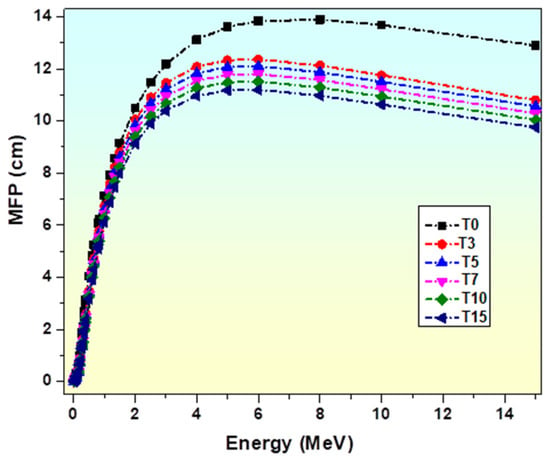

3.7.3. Mean Free Path (MFP)

MFP is frequently employed to assess the manner in which shielding materials protect against gamma rays in a number of applications, such as nuclear physics and medicine [19]. It determines the average distance between subsequent gamma-ray interactions within an attenuator material [84,88]. It is the most crucial indicator that accurately depicts a barrier’s ability to reduce gamma radiation. Notably, smaller values of this parameter result in better shielding performance [84]. The data indicate that the MFP of the studied glasses increases with photon energy (Figure 12), suggesting that a larger number of photons can penetrate the glasses at higher energies [88]. According to the obtained data, the MFP of the studied glasses increases with the radiation’s photon energy (Figure 12), indicating that a greater number of photons can penetrate the glasses at higher energy values. However, Figure 12 clearly shows that as the TiO2 contents increase, the value of MFP considerably drops. In contrast to the other samples, T15 requires a minimum thickness for efficient photon absorption since the sample densities are as follows: T0 < T3 < T5 < T7 < T10 < T15. TiO2-glass samples’ shielding capabilities are found to be in the following order: T0 < T3 < T5 < T7 < T10 < T15. This implies further that titanium presence in glass systems enhances shielding capabilities.

Figure 12.

Variation in MFP of glasses with photon energy.

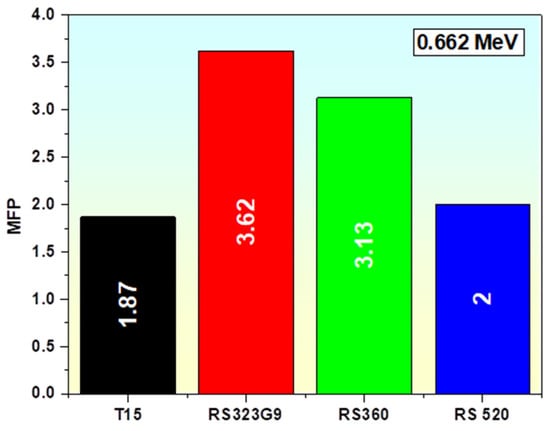

Concrete and commercial glasses are well-established as effective shielding materials due to their low MFP values [83,88]. Compared to these commercial concretes, the T15 glass sample exhibits an even lower MFP (Table 6), indicating superior photon shielding capability. A comparison of these TiO2-doped glasses at 0.662 MeV with various commonly used gamma-ray shielding glasses (RS323G9, RS360, and RS520) shows that the MFP of the TiO2-glass systems is lower than that of most conventional radiation-protection glasses [84,88] (Figure 13) and concretes (Table 6).

Table 6.

Comparison of the MFP of prepared glasses with shielding concretes.

Figure 13.

Comparison of the MFP of the T15 sample with commercial glasses at 0.662 MeV of energy.

3.7.4. Half Value Layer (HVL)

The HVL may be used to measure the amount of gamma photon penetration through any glass sample. It is a significant penetrating parameter that is commonly used to determine how thick the absorber must be in order to block half of the initial radiation intensity. It is better to create and produce glasses with a low HVL value for practical applications, such as greater radiation shielding. It has been established that it is dependent on the energy of the photon, chemical proportion, and density of the materials.

Variation in HVL with Eγ (Photon Energy)

Figure 14 describes the variation in HVL of TiO2-glasses with photon energy. Because of its inverse dependence on the attenuation coefficient, it has a smaller value at lower energy levels. HVL is seen to increase quickly from 0.015 to 3 MeV of energy and becomes roughly constant beyond 3 MeV. In the energy range of 0.015 to 0.4 MeV, HVL has a value less than 1. This variation in HVL is governed by three gamma interaction modes: photoelectric absorption, Compton scattering, and pair production [83]. It is observed from the figure that the sample T15 has the least HVL value.

Figure 14.

Variation in HVL of glasses with photon energy.

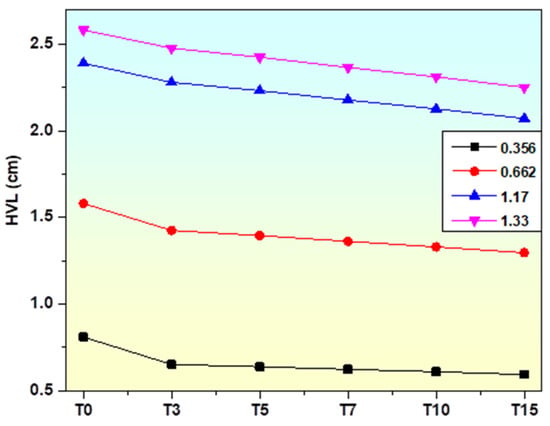

Variation in HVL with Chemical Composition

The HVL variation in the glasses with chemical composition of TiO2 at 0.356, 0.662, 1.17, and 1.33 MeV is shown in Figure 15. It is evident that the HVL for the samples decreases when the TiO2 varies from 0 to 15 mol%. All of the present TiO2 samples have an HVL value lower than the non-doped glass sample, indicating that the addition of TiO2 at the expense of borate oxide has resulted in a reduction in the HVL. For example, the HVL for the undoped sample at 1.33 MeV is 2.58 cm, and this value decreases to 2.48, 2.42, 2.37, 2.31, and 2.25 cm for TiO2-doped. It is well known that the density of the sample has a significant impact on photon penetration and, consequently, the HVL of the sample. A less dense medium allows photons to pass through more readily than denser ones. To put it another way, interactions are more likely to occur in a medium with a higher density, which results in the photons losing energy. Consequently, the lower the HVL of a glass sample, the denser the sample. Table 2 shows that the density of the glasses grows as TiO2 concentrations increase, which accounts for the HVLs decline upon the addition of the transition metal oxide (TiO2).

Figure 15.

Variation in HVL of prepared glasses at selected photon energy.

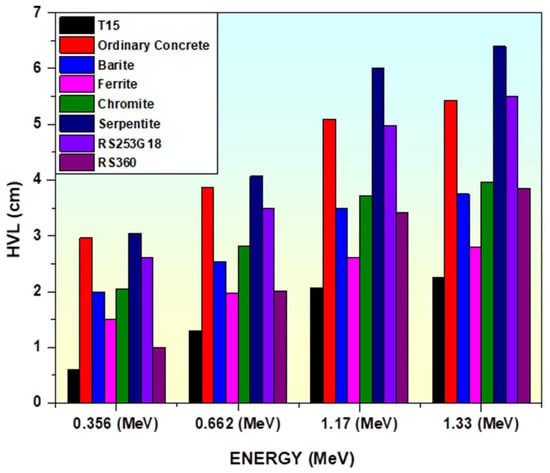

In order to have a deeper comprehension of the shielding capabilities of prepared glasses, Figure 16 compares the HVL of these glasses with commercial radiation shielding concretes and glasses [85,86,89]. According to the comparison, out of all these commercial glasses and concretes, TiO2 glasses have the lowest HVL.

Figure 16.

Variation in HVL of prepared glasses with concretes and commercial shielding glasses.

Table 7 compares the MAC, LAC, HVL, and MFP values of sample T15 against several radiation shielding glasses at 0.662 MeV to gain further insight into the shielding capabilities of titanium glass. This comparison supports T15 glass capability as an efficient and environmentally friendly shield for glasses [90,91,92,93,94,95].

Table 7.

Comparison of MAC, LAC, HVL & MFP of T15 glass sample with the literature-selected radiation shielding glasses at 0.662 MeV of energy.

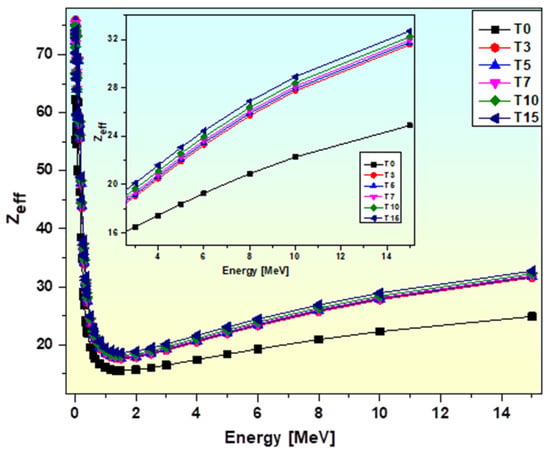

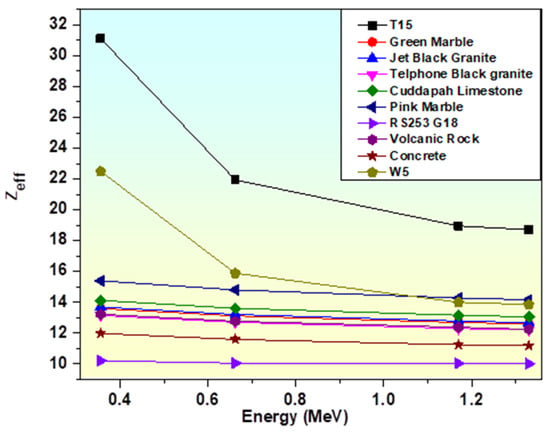

3.7.5. Effective Atomic Number (Zeff)

High atomic number and density are the most relevant properties of radiation-resistant materials. Previous research has demonstrated that materials or glasses with higher effective atomic number (Zeff) values have a better capacity to absorb photons and, as a result, have stronger radiation attenuation capabilities. Figure 17 shows Zeff variation with energy Eγ. The chemical formation of glasses and photon energy both affect Zeff.

Figure 17.

Variation of Zeff of glasses with photon energy.

It is found that the Zeff values are moderate in the high energy zone, minimal in the intermediate energy region, and maximum in the low energy region. At the lower photon energy range of 0.015 MeV to 1 MeV, the Zeff is significantly reduced as a result of photoelectric absorption. The Zeff values continue to decrease, but more gradually, as energy increases towards the middle energy range. With a slightly inverse relationship with energy, the Compton scattering mechanism is the most significant photoelectric effect in the intermediate energy range. Finally, the minor increase in the Zeff values is because of the supremacy of the pair production interaction at high energies. According to the comparison, T0 has the lowest Zeff values of any glass sample, which is associated with its lower molecular mass and density.

It can be inferred from the chemical composition of the glass samples that adding more TiO2 to any of the examined glass samples will greatly increase their Zeff values. The glass sample that has a greater TiO2 content (T15) has a higher Zeff value. The addition of TiO2 enhances the glasses’ density and total atomic number, which in turn enhances their capacity to shield radiation [84].

Zeff of the T15 sample is also compared with bricks, concrete, rocks, granites, and glasses, etc., as reported by other researchers in Figure 18 to achieve a better understanding of the shielding capabilities of produced glasses [84,86,96,97]. The glass sample T15 has an effective atomic number greater than any of them, indicating that the T15 glass sample is a better absorber.

Figure 18.

Variation of Zeff of T15 sample with marbles/concrete/rocks/granites, etc.

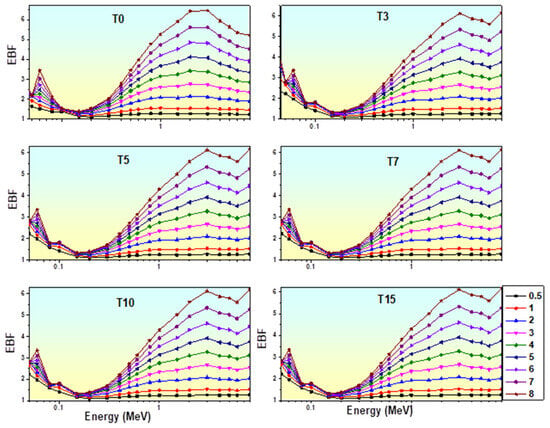

3.7.6. Exposure Buildup Factor (EBF)

The EBF of the TiO2 incorporated glasses with different mol% of TiO2 with photon energy (Eγ) varies at different chosen penetration depths (λ) (0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 mfp), as shown in Figure 19. Table 8 compares the EBF values of the T15 sample at particular penetration depths and photon energies (0.15 and 1.5 MeV) with the EBF of Lead, and some concretes/glasses [78,84,98,99].

Figure 19.

Variation in EBF of glasses with photon energy.

Table 8.

Comparison of the EBF of prepared glasses with shielding materials.

As shown in Figure 19, the EBF of the glasses was highest in the higher-energy regions with 0–15 mol% of TiO2, while it was lowest in the low-energy regions. Since these photons are entirely eliminated by photoelectric absorption, the EBF values are smaller at low energies. At intermediate energy, these increase due to multiple Compton scattering; in the high-energy region, these increase again due to pair production. TiO2 (0, 3, 7, 10, and 15 mol%) added to the matrix alters the EBF values’ magnitude, as observed in Figure 19. It is evident that when the molar concentration of titanium increases, the EBF values of the glasses fall. Figure 19 shows a peak in the EBF values around 0.6 MeV energy, which might be the result of k-edge absorption of heavy metal oxide. Due to many scattering events at significant penetration depths (Pds), the EBF was observed to be maximum at 40 mfp and lowest at 0.5 mfp. For Pds of 40 mfp, EBF for TiO2 glasses reaches its maximum value. At the same time, the value of EBF declines with the upsurge in the mol% of TiO2 in prepared glasses. The T15 glass sample has the lowest value of EBF among other prepared glasses.

The TiO2 glass containing 15 mol% of titanium exhibited the lowest EBF values, making it the finest γ-shielding material. Table 8 compares the EBF values of our glasses to those of ordinary concrete (OC), ilmenite-limonite concrete (ILC), S7, Steel Scrap (SC), BS, steel–magnetite concrete (SMC), and lead [78,84,98,99]. According to this comparison, except for lead, the EBF of the T15-glass containing 15 mol% TiO2 is lower than commercial concretes and glasses. We may thus conclude that the TiO2 glasses are possible choices for safeguarding against gamma rays.

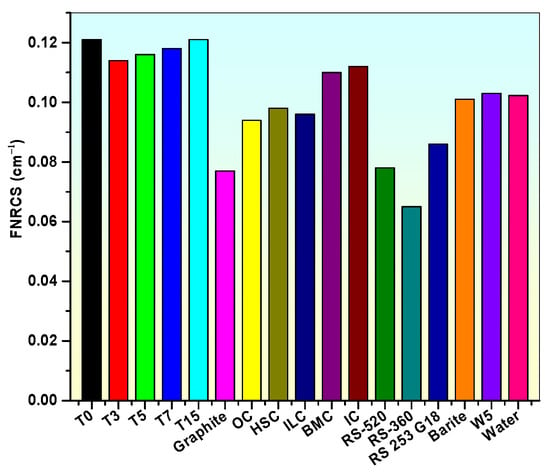

3.8. Fast Neutron Removal Cross Section (FNRCS (∑R) in cm−1)

The (∑R (cm−1) values of the glass samples are given in Figure 20. It is observed that the T0 and T15 samples have the highest value of FNRCS. The extreme value of FNRCS for the T0 sample is detected due to the higher contribution of B2O3 element. But even the sample T15, which has a lower value of boron, possesses better neutron shielding competence. So, it can be concluded that these glass samples (T0 and T15) are superior neutron shielding materials. The FNRCS value of these glasses has been compared with other commercial neutron protecting glasses and concretes, as shown in Figure 20, in order to determine their neutron shielding competency [5,84,85,100]. When compared to the above-mentioned glasses/concrete, this comparison shows that the neutron shielding capacity of TiO2-doped and undoped glasses is higher (Figure 20). Additionally, it has also been perceived that the produced glasses are more successful at diminishing the fast neutrons when comparing their FNRCS (∑R) values to those of water, which is thought to be an excellent neutron absorber (0.1023 cm−1) [5].

Figure 20.

Comparison of FNRCS of prepared samples with concretes and shielding glasses.

4. Conclusions

The findings of this study demonstrate that TiO2 plays a crucial role in modifying the structural, physical, optical, elastic, and shielding properties of the glasses. Specifically, incorporating TiO2 into B2O3-based glasses significantly enhances their structural rigidity, optical performance, elastic behavior, and radiation-shielding efficiency. The addition of titanium decreases the molar volume while increasing the density, indicating the formation of a more compact glass network. Variations in OPD, ion concentration, field strength, inter-ionic distance, and boron–boron separation further clarify how the glass system responds to TiO2 incorporation. The increase in OPD reflects tighter atomic packing and a more compact structure. FTIR analysis confirms that the formation of BO4 units induces structural rearrangements that improve the stiffness of the glass.

Optically, TiO2 doping reduces the optical band gap and increases the refractive index, consistent with a higher concentration of compact BO4 groups. These changes enhance the suitability of the glasses for photonic applications. The reduced metallization criterion value suggests decreased insulating behavior. Additionally, replacing B2O3 units with TiO2 increases the electronic polarizability and optical basicity, indicating the development of stronger ionic bonding. Improvements in Vickers hardness and elastic constants confirm increased stiffness and mechanical stability. Overall, TiO2 incorporation results in a more densely packed glass network, which is essential for enhancing photon–material interactions and improving radiation-shielding performance.

To analyze the radiation protection characteristics of glasses across a broad energy range, the current investigation employed Phy-X/PSD software. The following conclusions have been drawn after analyzing the most often used parameters, such as MAC, LAC, Zeff, MFP, HVL, EBF, and FNRCS:

- The produced glasses have higher LAC, MAC, and Zeff values. The sample T15, which contains the maximum titanium oxide, has the highest Zeff, MAC, and LAC values. Comparing the T15 glass sample’s MAC, LAC, and Zeff to particular concretes such as OC, BMC, HMC, SSC, ILC, shielding glasses, and rocks/granites, etc., it is discovered that the T15 glass sample had superior shielding properties.

- Glass sample T15, which contains the highest TiO2 concentration, exhibits the lowest HVL and MFP values.

- It is discovered that the produced glasses have a lower HVL value than concretes (barite, ferrite, chromite, etc.) and a variety of commercial glasses (RS 253 G18, RS 360). The higher shielding properties of our manufactured glasses are demonstrated by the MFP value of the T15 sample when compared to the RS 360, RS 323 G9, and RS 520 commercial glasses.

- The FNRCS of both TiO2-doped and undoped glasses is superior to that of various other shielding glasses and concrete.

- These modifications make TiO2-incorporated glasses strong candidates for advanced optical applications. Moreover, the results demonstrate their exceptional capability for gamma/neutron radiation shielding, outperforming several conventional concretes and commercial glasses. Consequently, these glasses hold significant potential for future photonic and radiation protection applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.P.S. and J.S.; methodology, G.P.S.; software, G.P.S.; validation, G.P.S., J.S. and K.K.; formal analysis, G.P.S., A.Y., J.S. and K.K.; investigation, G.P.S. and J.S.; resources, G.P.S. and K.K.; data curation, G.P.S.; writing—original draft preparation, G.P.S. and J.S.; writing—review and editing, G.P.S., J.S., A.Y. and K.K.; visualization, G.P.S. and K.K.; supervision, G.P.S. and K.K.; project administration, G.P.S.; funding acquisition, G.P.S., J.S., A.Y. and K.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Abayomi Yusuf and Kulwinder Kaur acknowledge funding from Science Foundation Ireland (SFI) under the SFI–Irish Research Council (IRC) Pathway Program (22/PATH-S/10864).

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors (Gurinder Pal Singh and Joga Singh) express their sincere gratitude to Principal Khalsa College, Amritsar, Punjab, for providing financial support in the form of seed money. Authors are highly thankful to the Departments of Physics and Chemistry, Khalsa College, Amritsar, for providing the instrumental facilities (UV–visible and FTIR). Abayomi Yusuf and Kulwinder Kaur acknowledge funding from Science Foundation Ireland (SFI) under the SFI–Irish Research Council (IRC) Pathway Program (22/PATH-S/10864).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Almuqrin, A.H.; Sayyed, M.I.; Alharbi, F.F.; Elsafi, M. Experimental evaluation of the impact of ZnO on the radiation shielding ability of B2O3–PbO–ZnO–CaO glass systems. Opt. Mater. 2024, 157, 116213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hadeethi, Y.; Sayyed, M.I.; Nune, M. Radiation shielding study of WO3–ZnO–PbO–B2O3 glasses using Geant4 and Phys-X: A comparative study. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 3988–3993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alan, H.Y.; Yilmaz, A.; Susam, L.A.; Ozturk, G.; Kilic, G.; Ilik, E.; Oktik, S.; Akkus, B.; ALMisned, G.; Tekin, H.O. tailoring optimal KERMA, projected range, and mass stopping power, and gamma-ray shielding capabilities through BaO/ZnO/CdO/SrO incorporation into Na2O–SiO2 glasses. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2025, 226, 112234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekin, H.O.; ALMisned, G.; Kilic, G.; Ilik, E.; Susoy, G.; Elshami, W.; Issa, B. A critical assessment of the mechanical strength and radiation shielding efficiency of advanced Concrete composites and Vanadium Oxide-Glass container for enhanced nuclear waste management. Results Phys. 2024, 64, 107901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Buriahi, M.S.; Olarinoye, I.O.; Yılmaz, E.; Çalıskan, F.; Sriwunkum, C. Evaluation of the structural and radiation transmission parameters of recycled borosilicate waste glass system: An effective material for nuclear shielding. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2025, 213, 111136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Buriahi, M.S. Radiation shielding performance of a borate-based glass system doped with bismuth oxide. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2023, 207, 110875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekin, H.O.; Singh, V.P.; Manici, T. Effects of micro-sized and nano-sized WO3 on mass attenauation coefficients of concrete by using MCNPX code. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2017, 121, 122–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, A.N.; Prabhu, N.S.; Sharmila, K.; Sayyed, M.I.; Somshekarappa, H.M.; Lakshminarayana, G.; Mandal, S.; Kamath, S.D. Role of Bi2O3 in altering the structural, optical, mechanical, radiation shielding and thermoluminescence properties of heavy metal oxide borosilicate glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2020, 542, 120136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaduvanshi, N.; Basavapoornima, C.; Alqarni, A.S.; Kagola, U.K.; Uthayakumar, T.; Madhu, A.; Srinatha, N. Enhanced white light emission and quantum efficacy of borate-zinc–lithium-aluminium glasses doped with Dy2O3 for potential white light emission applications. Opt. Mater. 2024, 151, 115359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaly, H.M.H.; Issa, S.A.M.; Ali, A.S.; Almousa, N.; Elsaman, R.; Kubuki, S.; Atta, M.M. Exploring the potential of bismuth-containing silicate borate glasses for optoelectronic devices and radiation protection. Opt. Mater. 2024, 156, 115956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almuqrin, A.H.; Sayyed, M.I.; Kumar, A.; Rilwan, U. Characterization of glasses composed of PbO, ZnO, MgO, and B2O3 in terms of their structural, optical, and gamma ray shielding properties. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2024, 56, 2842–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccaro, S.; Catallo, N.; Cemmi, A.; Sharma, G. Radiation damage of alkali borate glasses for application in safe nuclear waste disposal. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 2011, 269, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shamy, N.T.; Mahrous, E.M.; Alghamdi, S.K.; Tommalieh, M.J.; Abomostafa, H.M.; Abulyazied, D.E.; Rabiea, E.A.; Abouhaswa, A.S.; Ismael, A.; Taha, T.A.M. Synergistic effect of WO3 on structural, physical, optical, and dielectric characteristics of multicomponent borate glasses for optoelectronic applications. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 30, 7927–7937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suragani, S.; Rao, K.H.; Patro, L.N.; Tirupataiah, C. Influence of TiO2 on the physical, thermal, mechanical, optical, and electrical characteristics of Li2O-GeO2-SiO2-Al2O3 glass ceramics. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1022, 179799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.P.; Singh, J.; Kaur, P.; Singh, T.; Kaur, R.; Kaur, S.; Singh, D.P. Impact of TiO2 on radiation shielding competencies and structural, physical and optical properties of CeO2–PbO–B2O3 glasses. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 885, 160939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koudelka, L.; Mošner, P.; Zeyer, M.; Jäger, C. Lead borophosphate glasses doped with titanium dioxide. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2003, 326–327, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aladim, A.K.; Bakry, A.M.; El-Sherif, L.S.; Hassaballa, S.; Ibrahim, A.; Qasem, A.; Moustafa, M.G. Transparent titanium ions doped lead-borate glasses with optimized persistent optical features for optoelectronic applications. Opt. Mater. 2024, 152, 115404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, M.G.; Saad, H.M.H.; Ammar, M.H. Insight on the weak hopping conduction produced by titanium ions in the lead borate glassy system. Mater. Res. Bull. 2021, 140, 111323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagamani, B.; Srinivasu, C. Physical parameters and structural analysis of titanium doped binary boro silicate glasses by spectroscopic techniques. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 18, 2077–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaeedy, H.I.; Qasem, A.; Yakout, H.A.; Mahmoud, M. The pivotal role of TiO2 layer thickness in optimizing the performance of TiO2/P-Si solar cell. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 867, 159150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhivya, V.; Dharshini, R.; Sakthipandi, K.; Rajkumar, G. Role of TiO2 in modifying elastic moduli and enhancing in vitro bioactivity of fluorophosphate glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2023, 608, 122250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwik, M.; Kowalska, K.; Pisarska, J.; Kochanowicz, M.; Żmojda, J.; Dorosz, J.; Dorosz, D.; Pisarski, W.A. Influence of TiO2 concentration on near-infrared emission of germanate glasses doped with Tm3+ and Tm3+/Ho3+ ions. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 41090–41097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzeldien, M.; Sadeq, M.S.; Al-Boajan, A.M.; Al Souwaileh, A.M.; Alrowaili, Z.A.; Almasoudi, A.; Amin, H.Y. Impact of TiO2/B2O3 ratio on the structure and optical properties of Na2O–CoCl2–TiO2–B2O3 glass. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 12678–12689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangthong, P.; Kohout, M.; Ponseca, C.S.; Hubička, Z.; Kaewkhao, J.; Kothan, S.; Kirdsiri, K.; Srisittipokakun, N.; Olejníček, J.; Cadatal-Raduban, M. Hybrid detectors for high-energy radiation based on borosilicate glass scintillator doped with Gd3+ covered by photosensitive TiO2 layer. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2025, 237, 113010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Si, X.; Jiang, H.; Yang, H.; Zhang, W.; Li, C.; Qi, J.; Cao, J. Effect of TiO2 on crystallization and sealing behavior of Na2O-K2O-TiO2-SiO2-Al2O3-ZnO glass sealant for PCFCs. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 15857–15866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyed, M.I.; More, C.V.; Almuqrin, A.H.; Mahmoud, K.A. Investigation of mechanical properties and radiation shielding features for CuO– PbO–B2O3–TiO2 glasses using MCNP5 simulation code. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2025, 235, 112867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Yadav, P.; Adhikari, A.; Mahar, G.; Manavathi, B.; Azeem, P.A. Bioactive investigation of TiO2 containing borophosphate glasses for medical applications: In-vitro studies. Surf. Interfaces 2025, 72, 107029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, B.; Bhemarajam, J.; Bhogi, A.; Prasad, P.S.; Shareefuddin, M. Highly efficient and stable Cr3+ activated SrO-TeO2- TiO2- B2O3 glasses for LED applications. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 23077–23089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montecillo, R.; Chen, C.-A.; Chien, R.R.; Chen, L.-Y.; Chen, C.-S.; Tu, C.-S.; Feng, K.-C. High-efficiency energy storage in BiFeO3 composite ceramics via BaO-TiO2-SiO2 glass modification. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2025, 45, 117197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanakya, N.; Madhuri, J.H.; Katta, K.K.; Upender, G.; Devi, C.S. Investigations on the augmented physical, thermal and optical properties of tellurite glasses containing WO3 and TiO2. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 17355–17367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwakuna, A.E.; Laxmikanth, C.; Manepalli, R.K.N.R. Impact of substituting Al2O3 with CuO on the structural, optical, thermal, mechanical, and gamma-ray attenuation properties of B2O3–Bi2O3–K2O–Al2O3 glass system. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2025, 229, 112517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, S.A.; Roshdy, R.; El-sadek, M.S.A.; Ezzeldien, M. Effect of Al2O3 on the structural, optical and mechanical properties of B2O3- CaO-SiO2-P2O5-Na2O glass system. Optik 2022, 250, 168281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Wang, H.; Ren, L.; Tu, B.; Wang, W.; Fu, Z. Theoretical study on composition-dependent properties of ZnO·nAl2O3 spinels. Part I: Optical and dielectric. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 104, 5099–5109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Wang, H.; Ren, L.; Tu, B.; Wang, W.; Fu, Z. Theoretical study on composition-dependent properties of ZnO·nAl2O3 spinels. Part II: Mechanical and thermo physical. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 104, 6455–6466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shweta; Dixit, P.; Singh, A.; Avinashi, S.K.; Yadav, B.C.; Gautam, C. Fabrication structural, and physical properties of alumina doped calcium silicate glasses for carbon dioxide gas sensing applications. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2022, 583, 121475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-F.; Lu, C.-M.; Wu, Y.-C.; Yang, Y.-C.; Chiu, T.-W. La2O3–Al2O3–B2O3–SiO2 glasses for solid oxide fuel cell applications. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2011, 36, 3666–3672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDowell, J.F. Aluminoborate Glass-Ceramics with Low Thermal Expansivity. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1990, 73, 2287–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, P.P.; Gedam, R.S.; Agarwal, K. Insight into the physical, structural, thermal and spectroscopic characteristics of intense green luminescent Tb3+ incorporated lithium alumino-borate glasses for green LED application. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1340, 142523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Anwar, A.W.; Moin, M.; Moin, M.; Nabi, S.; Ahmed, R.B.; Ahmad, S.; Ali, A.; Shaheen, S. Doping effect on structural, mechanical stability, tunning bandgap, optical and thermodynamical responses of indium doped aluminium arsenide for optoelectronic applications: By first-principles. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2025, 712, 417211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Su, K.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Z. Structure, spectra and thermal, mechanical, Faraday rotation properties of novel diamagnetic SeO2-PbO-Bi2O3-B2O3 glasses. Opt. Mater. 2018, 80, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łaczka, M.; Stoch, L.; Górecki, J. Bismuth-containing glasses as materials for optoelectronics. J. Alloys Compd. 1992, 186, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şakar, E.; Özpolat, Ö.F.; Alım, B.; Sayyed, M.I.; Kurudirek, M. Phy-X/PSD: Development of a user friendly online software for calculation of parameters relevant to radiation shielding and dosimetry. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2020, 166, 108496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, G.N.; Rao, P.V.; Kumar, V.R.; Chandrakala, C.; Ashok, J. Study on the influence of TiO2 on the characteristics of multi component modifier oxide based B2O3 glass system. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2018, 498, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.P.; Kaur, P.; Kaur, S.; Singh, D.P. Conversion of covalent to ionic character of V2O5–CeO2–PbO–B2O3 glasses for solid state ionic devices. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2012, 407, 4269–4273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naaim, M.M.; Malek, M.F.; Sayyed, M.I.; Sahapini, N.F.M.; Hisam, R. Impact of TeO2–B2O3 manipulation on physical, structural, optical and radiation shielding properties of Ho/Yb codoped mixed glass former borotellurite glass. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 10342–10353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saddeek, Y.B.; Azooz, M.A.; Kenawy, S.H. Constants of elasticity of Li2O–B2O3–fly ash: Structural study by ultrasonic technique. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2005, 94, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahshan, A.; Saddeek, Y.B.; Aly, K.A.; Shaaban, K.H.S.; Hussein, M.F.; El Naga, A.O.A.; Shaban, S.A.; Mahmoud, S.O. Preparation and characterization of Li2B4O7–TiO2–SiO2 glasses doped with metal-organic framework derived nano-porous Cr2O3. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2019, 508, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, A.; Aloraini, D.A.; Al-Baradi, A.; Shaaban, S. Synthesis, structural, elastic properties, and radiation shielding potential of La2O3–B2O3–Nd2O3 glasses for multi-application potential. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2025, 233, 112710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouhaswa, A.S.; Mhareb, M.H.A.; Alalawi, A.; Al-Buriahi, M.S. Physical, structural, optical, and radiation shielding properties of B2O3- 20Bi2O3- 20Na2O2- Sb2O3 glasses: Role of Sb2O3. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2020, 543, 120130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Baki, M.; Abdel-Wahab, F.A.; El-Diasty, F. One-photon band gap engineering of borate glass doped with ZnO for photonics applications. J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 111, 073506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamitsos, E.I.; Patsis, A.P.; Karakassides, M.A.; Chryssikos, G.D. Infrared reflectance spectra of lithium borate glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 1990, 126, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciceo-Lucacel, R.; Ardelean, I. FT-IR and Raman study of silver lead borate-based glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2007, 353, 2020–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisarski, W.A.; Pisarska, J. Witold Ryba-Romanowski, Structural role of rare earth ions in lead borate glasses evidenced by infrared spectroscopy: BO3↔BO4 conversion. J. Mol. Struct. 2005, 744–747, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doweidar, H.; El-Egili, K.; Ramadan, R.; Al-Zaibani, M. Structural units distribution, phase separation and properties of PbO–TiO2–B2O3 glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2017, 466–467, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, L.S.; Prasad, M.V.R.D.; Prabha, K.A.; Rahul, G.; Srikanth, B.; Nayak, G.R.; Kiran, B.R. Quantitative structure–property correlations in CaO–B2O3–Al2O3–TiO2 glasses: Synthesis and spectroscopic assessment for radiation shielding, magnetic resonance, and bandgap engineering applications. Next Mater. 2025, 8, 100934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Singh, G.; Kaur, P.; Singh, T.; Singh, I.; Kaur, S.; Singh, I.; Singh, D.P. Exploring the Modification in Physical, Structural and Optical Properties of BaO–PbO–B2O3 Glasses by Incorporating Sm2O3. Acta Phys. Pol. A 2025, 148, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaafar, M.S.; El-Aal, N.S.A.; Gerges, O.W.; El-Amir, G. Elastic properties and structural studies on some zinc-borate glasses derived from ultrasonic, FT-IR and X-ray techniques. J. Alloys Compd. 2009, 475, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Yang, P.; Zhu, H.; Han, B.; Hu, Y. Effect of melting atmospheres on the structure and optical properties of La2O3-TiO2-B2O3 system glass. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 10716–10725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.P.; Singh, J.; Kaur, P.; Singh, T.; Kaur, R.; Singh, D.P. The Role of Lead Oxide in PbO-B2O3 Glasses for Solid State Ionic Devices. Mater. Phys. Mech. 2021, 47, 951–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Singh, G.P.; Kaura, P.; Singh, T.; Bhatia, S.; Kaur, R.; Singh, D.P. Impact of ZnO on the Physical and Optical Properties of PbO–B2O3 Glasses. Acta Phys. Pol. A 2022, 142, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouhaswa, A.S.; Zakaly, H.M.H.; Issa, S.A.M.; Rashad, M.; Pyshkina, M.; Tekin, H.O.; El-Mallawany, R.; Mostafa, M.Y.A. Synthesis, physical, optical, mechanical, and radiation attenuation properties of TiO2–Na2O–Bi2O3–B2O3 glasses. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyed, M.I.; Biradar, S.; More, C.V.; Mahmoud, K.A. Investigation of the optical and gamma-ray attenuation performance of borate-based glasses: Influence of BaO, ZnO, and CaO doping. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2025, 221, 111557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouhaswa, A.S.; Kavaz, E. Bi2O3 effect on physical, optical, structural and radiation safety characteristics of B2O3-Na2O-ZnO-CaO glass system. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2020, 535, 119993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, M.A.; ElBatal, F.H. UV-visible and infrared absorption spectra of Bi2O3in lithium phosphate glasses and effect of gamma irradiation. Appl. Phys. A 2014, 115, 903–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouhaswa, A.S.; Sayyed, M.I.; Altowyan, A.S.; Al-Hadeethi, Y.; Mahmoud, K.A. Synthesis, structural, optical and radiation shielding features of tungsten trioxides doped borate glasses using Monte Carlo simulation and phy-X program. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2020, 543, 120134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Buriahi, M.S.; Alrowaili, Z.A.; Alomairy, S.; Olarinoye, I.O.; Mutuwong, C. Optical properties and radiation shielding competence of Bi/Te-BGe glass system containing B2O3 and GeO2. Optik 2022, 257, 168883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaky, K.M.; Sayyed, M.I.; Hamad, M.K.; Biradar, S.; Mhareb, M.H.A.; Altimari, U.; Taki, M.M. Bismuth oxide effects on optical, structural, mechanical, and radiation shielding features of borosilicate glasses. Opt. Mater. 2024, 155, 115853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biradar, S.; Dinkar, A.; Manjunatha; Bennal, A.S.; Devidas, G.B.; Hareesh, B.T.; Siri, M.K.; Nandan, K.N.; Sayyed, M.I.; Es-soufi, H.; et al. Comprehensive investigation of borate-based glasses doped with BaO: An assessment of physical, structural, thermal, optical, and radiation shielding properties. Opt. Mater. 2024, 150, 115176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]