Abstract

Background: A training program for University Internship Supervisors in Dentistry (UISD) was created from scratch in 2022 at the Faculty of Dentistry in Tours. Designed to prepare practitioners for the role of UISD, it is structured into three distinct modules, each with specific educational objectives. The first module, dedicated to the supervision of students during observation internships, has been delivered for three years. Aim: To assess the experience of UISDs as trainers, to identify their perceptions of their role, and to assess their expectations regarding the future development of this training. The study also aimed to propose a knowledge and competency framework that could serve as a basis for this first module. Methods: A qualitative approach was used, based on semi-structured individual interviews with trained UISDs who had supervised students during observation internships. Interviews were coded and analyzed inductively. Results: A total of 19 UISDs participated in the study. The mean age was 49.4 years, with an average of 23.9 years of private practice experience. Providing high-quality supervision to students in their offices was considered a major priority. Based on these results, the UISD training program was revised to identify four structuring themes for a competency framework: the internship environment, required knowledge, interpersonal skills (soft skills), and practical skills (know-how). Conclusions: The UISD training program in dentistry, designed for observation internships, has been adapted to meet practitioners’ expectations and has evolved into an initial structured framework of competencies and knowledge for supervising students during observation internships. This framework will require ongoing refinement.

1. Introduction

The transition from university-based dental training to independent private practice remains a well-identified challenge in dental education. Evidence shows that skills developed in academic or hospital-based settings are not always transferred effectively once graduates enter real-world practice environments. Newly qualified dentists often report reduced use of evidence-based practice, difficulties in autonomous decision-making, and gaps in communication or practice-management skills during their first months in practice [1,2,3]. Qualitative studies highlight that the pace, organizational constraints, and medico-legal responsibilities of private practice differ markedly from those experienced during supervised clinical training, contributing to this “theory–practice gap” [3,4]. In response, several educational strategies aim to strengthen the transferability of competencies, including competency-based education frameworks, expanded community-based rotations, and structured mentorship during early professional practice. These approaches seek to align university curricula with the realities of independent clinical work and to better support graduates during the transition. Although promising, current evidence suggests that these interventions only partially bridge the gap, indicating a continued need for curricular refinement and closer integration between dental schools and practice settings [5,6]

Dental studies in France are organized as a progressive and structured curriculum within the Dental Faculties (UFR—Unités de Formation et de Recherche en Odontologie), under the supervision of hospital-university faculty members (Full Professor, Associate Professor or Assistant Professor). Since the 2003–2004 academic year, this program has been integrated into the European LMD system (Bachelor-Master-Doctorate), ensuring degrees harmonization, promoting academic mobility, and facilitating the international recognition of qualifications [7].

The practice of dentistry in France remains predominantly private today, and more than 9 out of 10 students intend to pursue general practice [8]. However, aside from a 250 h private practice internship during the final cycle—where pedagogical objectives remain highly heterogeneous—all initial training for dental practitioners takes place in hospitals. To address this gap, the creation of the Tours Dental Faculty in 2022 prompted a fundamental reflection during curriculum development on the need to involve private practitioners more actively in training. The goal is to ensure high-quality practical learning by transferring hospital-acquired competencies into real-world practice.

Within this context, the curriculum at the Tours Faculty aims to fully integrate private practitioners into training. The objective is for them to transmit their experience in a structured and systematic manner, in full alignment with the core academic teachings delivered within the UFR. The National Council for Higher Education and Research (Conseil national de l’enseignement supérieur et de la recherche—CNESER) validated two initiatives: in 2022, during accreditation to award the General Diploma in Dental Sciences (Diplôme de Formation Générale en Sciences Odontologiques—DFGSO), and in 2024, for the accreditation of the Advanced Diploma in Dental Sciences (Diplôme de Formation Approfondie en Sciences Odontologiques—DFASO). These initiatives include an observation internship with a university internship supervisor (UIS) in the second year, followed by a tutored internship in the fourth year, each lasting 50 h.

In this framework, a training program for university internship supervisors in dentistry (UISD) was established ex nihilo in 2022. It builds on models used in general medicine, adapted to the particularities of dental training. Each specialty retains its own particularities and challenges, and this program remains experimental at the Tours Faculty. This UISD training comprises three distinct modules, each targeting specific pedagogical objectives, delivered as seven-hour training days. The first module prepares UISD to host students in observation internships; the second focuses on supervising students during tutored internships; and the third supports students during supervised autonomous internships during the third cycle.

After three years of implementing the first module, this pilot study aimed to investigate the experiences of UISDs as trainers, to explore their perceptions of their role, and to identify their expectations regarding the development of these training programs. The study was designed to answer the following research questions: (1) How do UISDs perceive their role as trainers? (2) What challenges and opportunities do they encounter in training students? (3) How can their experiences inform the refinement of the training module? Additionally, the study aimed to develop a preliminary knowledge and competency framework that could serve as a foundation for the first module and guide future program improvements.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Participant Selection

Inclusion Criteria

The study involved volunteer dentists willing to host students in their private practices and committed to the healthcare and education project of the Tours Dental Faculty. All applications were reviewed first by the local dental council to which the candidates belonged, and then by a panel of faculty members from the Tours Faculty with the aim of ensuring a balanced distribution of UISD across the six departments of the Centre-Val de Loire region. Participants were also required to have completed the first preparatory UISD training module.

Exclusion Criteria

- -

- History of disciplinary sanctions or ongoing investigations.

- -

- Inability to accommodate a student (e.g., no additional dental chair or adequate equipment).

- -

- Refusal or lack of commitment to the training and healthcare project of the Faculty of Dentistry.

- -

- Practice location incompatible with the planned regional distribution to ensure balanced coverage.

2.1.2. Training Evaluated

The training evaluated focused on the first module of the university internship supervisor program, designed to prepare participants to host students during observation internships. This module is conducted over a full day, during which fundamental pedagogical concepts are addressed using active learning methods such as the flipped classroom and role-playing. The content includes objective-based pedagogy and an introduction to observation-specific teaching methods. Elements related to the students’ level of knowledge were also discussed, enabling supervisors to adjust their teaching approach accordingly (Appendix A).

2.1.3. Collection of Perceptions and Expectations Regarding Training

Data were collected using two anonymous questionnaires (Appendix B and Appendix C), in accordance with the General Data Protection Regulation (RGPD—Règlement général sur la protection des données) applicable at the University of Tours. Responses were automatically centralized in a Google Sheets spreadsheet through the use of an electronic link that allowed efficient access for all targeted participants. This procedure ensured both participant confidentiality and the reliability of data collection [9].

The questionnaire on pre-training expectations consisted of five open-ended questions (Appendix B). Its aim was to elicit the anticipations, concerns, and broader vision that prospective UISDs—naive to UIS training—might have regarding their role in the student’s educational process.

The questionnaire on post-training perceptions (Appendix C) included 14 open-ended questions. It was administered to UISD who had completed the first module of UIS training. Its aim was to explore the knowledge and competencies acquired through the UISD training, as well as their initial practical experience.

2.2. Methods

Production of Verbatim Data: Theoretical Framework

This study follows an evaluative approach as described by Kirkpatrick [10], which consists of four levels:

Level 1—Reaction: Collecting participants’ immediate “in-the-moment” reactions at the end of the training.

Level 2—Learning: Assessing the technical skills, knowledge, and know-how acquired during the training (short-term evaluation).

Level 3—Behaviour: Examining pedagogical transfers in the workplace; measuring changes in operational practices.

Level 4—Results: Measuring the final outcome of the training and its impact on social performance in our context.

Analysis of Verbatim Data

Data were analyzed according to the methodological recommendations of Berthier [11]. First, only clearly expressed ideas and proposals from the UISDs were retained by two independent coders (F.D. and G.S.) Initially, each coder performed an in-depth reading of the transcripts and carried out open coding of the data. The coding frameworks were then compared during regular meetings, where discrepancies were discussed until consensus was reached, allowing the analytical framework to be refined and stabilized. This iterative process helped ensure coding reliability and consistency. Data collection and analysis continued until theoretical saturation was achieved, with no new themes emerging from the analysis of the final interviews. In a second step, an analogical classification of responses was conducted by the principal investigator under the supervision of H;B and G.S. to identify coherent thematic distinguishing competencies derived from participant interviews from those drawn from pedagogical literature. Finally, a third recoding phase was carried out to extract central concepts, following an approach inspired by grounded theory.

3. Results

3.1. Population

A total of 19 UISDs met the inclusion criteria for the study. The mean age was 49.4 years, and the average duration of private practice experience was 23.9 years. The sample showed a slightly higher proportion of men (52%).

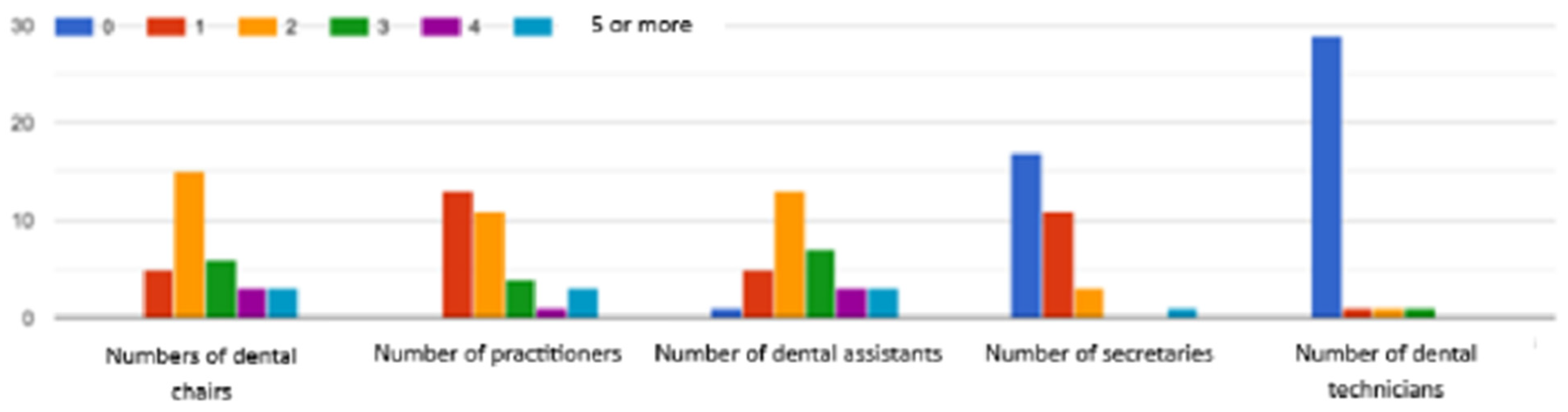

On average, UISDs had more than two dental chairs in their practices. They generally worked in partnerships or associations with another practitioner (one or two) and were mostly assisted by one to two dental assistants. Few practices had a dedicated medical secretary, and none had an on-site dental technician (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Descriptive data of the 19 UISD practice conditions.

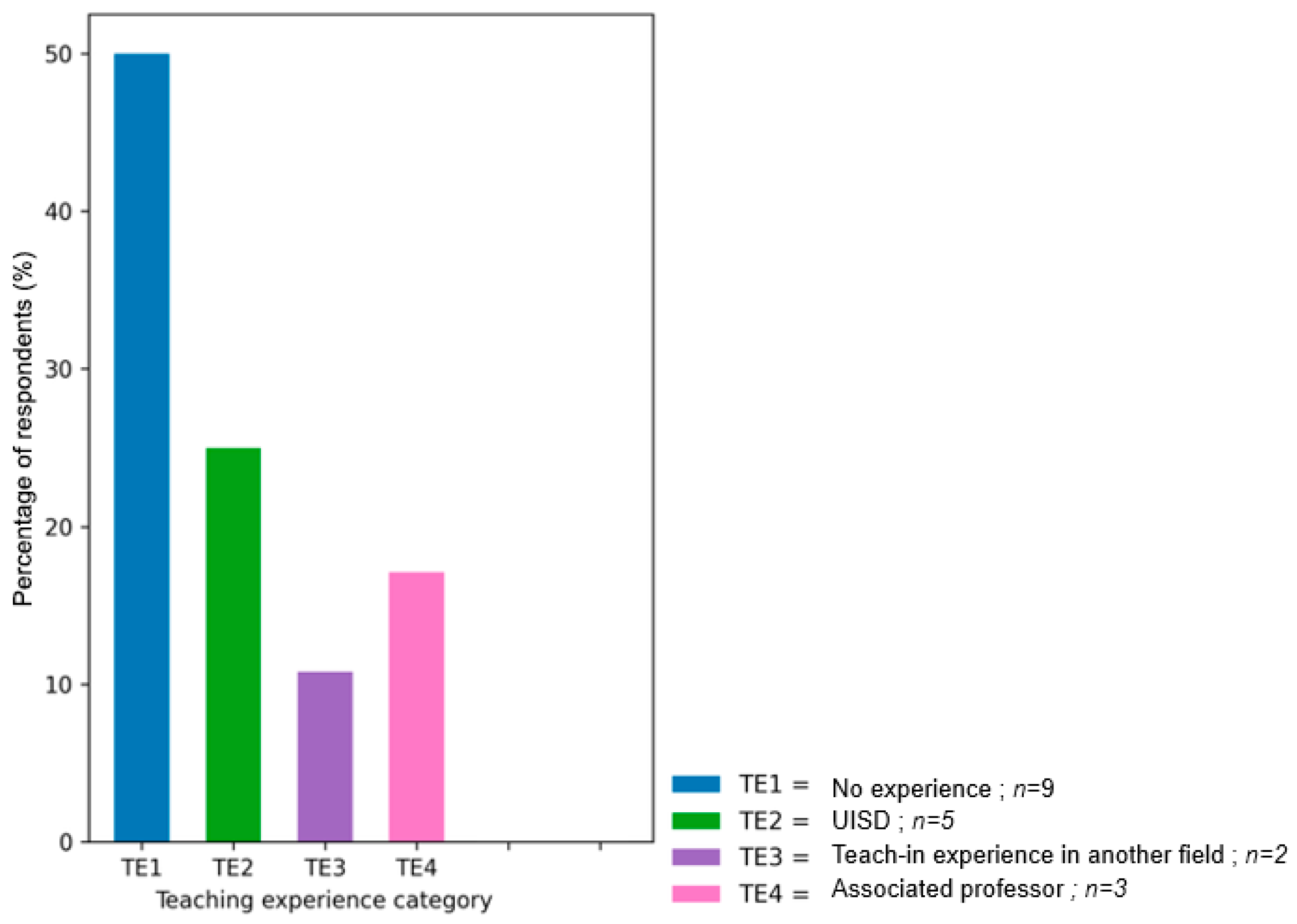

3.2. Teaching Experience Before Training

Regarding teaching experience, 52% of UISDs had no prior experience before their engagement. The remaining participants reported varied experiences, including clinical supervision, hospital-university positions, or other teaching activities (Figure 2). It should be noted that four of the participants had previously received training in internship/supervision management (21.1%).

Figure 2.

Teaching experience of UISDs.

3.3. Pre-Training Expectations

For UISDs, the quality of student hosting in their practices was considered a key issue not to be overlooked. This competency was perceived as important to strengthen, both in terms of know-how—that is, the organization and management of the internship—and in terms of interpersonal skills, particularly the attitude to adopt toward students.

“Welcoming the student under good conditions, adapting my speech to the student’s level…/…will I be up to the standards of my former professors…/…”

Participants also expressed concern about adapting their communication to the knowledge and skill levels of students during observation internships. They acknowledged that teaching is a distinct profession, requiring an appropriate stance and language when interacting with young adults, especially in a societal and professional context that has evolved significantly since their own Faculty years.

“Handling delicate pedagogical situations…/…explaining treatment plans according to the student’s learning level…/…are there specific things I should show them…/…”

At the end of this first questionnaire, only two participants indicated the need to strengthen their pedagogical knowledge, without specifying precise expectations. Pedagogy remains a notion that is still poorly structured in the discourse of future UISDs.

“Pedagogy, relational accessibility…/…pedagogy, patience…”

3.4. Post-Training Expectations

Regarding the training objectives, it appears that the expectations expressed by future UISD were not fully aligned with the pedagogical goals of the trainer. While learners were primarily concerned with improving their practical and interpersonal skills before the course, the training aimed more to provide a theoretical foundation on fundamental pedagogical concepts. Nevertheless, by the end of the session, participants had assimilated several key notions, allowing them to approach both practical and interpersonal dimensions of supervision more confidently and positively reshape their understanding of these essential concepts.

Additionally, the need for feedback on the guidance provided to their interns was particularly pronounced. This highlights UISD’s interest in their role as trainers and their willingness to engage in reflective practice and continuous improvement of their teaching methods.

“Receiving feedback on how the internships went…/…knowing what the student learned…/…we try to respond as best we can”.

Knowledge about training pathways also deserves reinforcement, particularly for UISD whose graduation was some time ago.

“Even though I tried to recall my own studies, I wasn’t fully aware of the student’s current training, what had already been covered, or the practices already performed…/…”

Questions related to dental practice management represent a major area of interest for UISD. This topic should be integrated into the pedagogical objectives of the training to better introduce and explain it to students.

“Integrating the student into the care team but also into the practitioner pair which has become a trio…/…managing a business with staff, orders, suppliers…/…”

Towards a Draft Competency Framework for Level 1 Internships

In light of these initial results, the internship mastery program -initially designed for observation internships- was revised by the trainer as part of a Master’s Research project conducted at the National Institute for Teacher Education (Institut National Supérieur du Professorat et de l’Éducation, Centre Val de Loire), in collaboration with the thesis supervisors.

Four major themes were formalized, structuring a preliminary knowledge and competency framework: internship environment, required knowledge, interpersonal skills (“savoir-être”), and practical skills (“savoir-faire”) (Table 1). Competencies in Table 1 were derived either from participant interviews or from pedagogical literature, as indicated in the Section 2.

Table 1.

Competency framework for an observation internship.

4. Discussion

Internationally, integrating structured private-practice internships into dental curricula is increasingly recognized as essential for effective competency transfer from controlled academic environments to independent practice. Evidence from diverse healthcare systems demonstrates that well-supervised community-based placements improve clinical proficiency, professional confidence, patient-centered care, and readiness for private-sector demands while reducing the transition shock experienced by new graduates [4,5,6].

Competency-based training programs for clinical supervisors have been developed, focusing on the identification, development, and evaluation of supervisory skills, and providing a theoretical and practical foundation for supervisor education in healthcare [12,13].

The present pilot contributes to this global movement by developing and evaluating a dedicated training program for private-practice supervisors in dentistry.

The UIS in medicine is a key component of training for future physicians. It ensures high-quality practical learning by linking theoretical teaching to real-world practice. Internship supervisors play a central role in developing students’ clinical, relational, and decision-making skills. This system also contributes to the progressive professionalization of medical students and residents while enhancing the attractiveness of underserved areas. Furthermore, it offers a form of recognition for supervising physicians, who actively participate in the transmission and renewal of the profession [14].

In nursing and allied health professions, foundational training programs such as Clinical Supervision for Role Development Training have been evaluated with multidisciplinary groups, demonstrating improvements in supervisors’ knowledge, skills, and confidence, and highlighting the value of structured and reflective learning environments for supervisor preparation [15].

Some national initiatives, such as clinical supervision training modules offered by health sciences institutions (e.g., workshops and online modules designed to support clinical educators in physiotherapy and rehabilitation), illustrate how formal training can help develop supervisory skills across different professional contexts [16].

In dentistry, the UIS framework has not yet been formally regulated in France. The work presented here is therefore part of an experimental approach, pending state-level decisions for nationwide implementation, as recommended in the report on the implementation modalities for a reform of the third cycle of dental studies, conducted under the supervision of the French General Inspectorate of Social Affairs and the General Inspectorate of Higher Education and Research [17].

To date, participating practitioners—entirely voluntary and unpaid—are mainly mid-career dentists, with a mean age of 49.4 years. This aligns with the idea that pedagogical engagement usually occurs after professional competencies have been consolidated, thereby conferring legitimacy in mentoring students [13,18]. There is also a noticeable interest in teaching among the 19 UISs participants in this study, as roughly half had previous teaching experience under various roles (hospital-university assistant, lecturer, etc.; see Figure 2. This demonstrates the existence of a pool of resource individuals capable of participating in this developing program, particularly since selection criteria, aside from teaching experience, prioritized geographic location within the Centre-Val de Loire region. This study thus identified competent practitioners ready to be integrated into UIS training, supporting the territorial integration of the Dental Faculties.

Before training, UISDs perceived student hosting as a central challenge, involving both the organization of the internship (know-how) and the attitude adopted toward students (interpersonal skills). They emphasized the need to adapt their communication to the students’ level and recognized that teaching is a profession requiring specific skills to adopt an effective mentor stance [19]. Although the need for pedagogical training was expressed, the concept remained poorly structured in their perception. Preparing health professionals for teaching is considered essential to improving pedagogical effectiveness. In general, faculty development activities are highly valued by participants, who also report changes in their learning and behaviour after completing them [20]. This fully supports the implementation of dedicated programs such as UISD training.

After completing the training and hosting students, UISD gained a better understanding of fundamental pedagogical concepts, allowing them to more confidently address practical skills and interpersonal aspects with their learners. They also expressed a strong need for feedback on their supervisory practices, as well as interest in students’ academic pathways and dental practice management. Based on these findings, the internship mastery program was revised, and four major themes were identified for a potential competency framework: internship environment, knowledge to be acquired, interpersonal skills, and practical skills (Table 1).

5. Limitations of the Study

It is important to note that the sampling strategy may have introduced bias. Participants were particularly committed volunteers with substantial clinical experience, and nearly half had previously held teaching roles. Furthermore, the limited number of participants, although sufficient for a qualitative study in terms of data saturation, does not rule out the possibility that a larger sample size might have provided greater nuance in the results. Finally, the issue of the training required for UISDs remains insufficiently explored in France. This lack of reference points complicated the methodological structuring of this study.

6. Perspectives

The development of the UISD program follows a process of continuous improvement, combining experimentation and iterative refinement. UISDs may test new teaching practices, strengthen their practical and interpersonal skills, and incorporate complementary objectives such as practice management and team leadership. The systematic collection of qualitative and quantitative data, combined with iterative reflection involving trainers and students, would help consolidate the UISD role, optimize intern supervision, and progressively develop a structured and transferable framework applicable to other Dental Faculties. This approach is particularly important for effectively engaging “Zoomers,” a generation characterized by a unique relationship with digital technology and a pragmatic view of society [21]. These students favour active learning, based on experimentation, discussion, and hands-on practice [22,23], in contrast to the pedagogical experience most UISD had, which was often hierarchical and teacher-centered. This approach is essential, as Generation Z no longer simply receives knowledge—they expect to participate in its construction.

7. Conclusions

Dental education in France faces the ongoing challenge of bridging the gap between hospital–university training environments and private practice settings, where the majority of graduates will work. This pilot study contributes to addressing this challenge by evaluating and adapting the UISD training program for observation internships. The program was adjusted to meet practitioners’ expectations and resulted in an initial structured framework of competencies and knowledge for supervising students during these internships. By providing a concrete, practice-oriented model for training UISD, this study offers both practical guidance for clinical education and a foundation for future research. This framework will require ongoing refinement, highlighting the importance of feedback and adaptation to meet the evolving needs of dental education.

Author Contributions

H.B. conceptualized the study, contributed to the methodology, data analysis, and drafted the manuscript; C.N. contributed to the methodology and data collection; F.D. was responsible for writing and drafting the manuscript; G.S. contributed to data collection; N.M. supervised the study; M.R. supervised the study. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors stated that no funding was received for conducting this study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Scientific Integrity and Research Ethics Committee of the University of Tours (reference: 351–2024). Data were handled by state-authorised individuals. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all University Internship Supervisors in Dentistry in the Centre-Val de Loire region for their commitment alongside the Tours UFR, contributing to addressing medical desertification and supporting professional integration in the territory.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Appendix A

Training in supervising university dental internships: Level 1 “Observation” 7 h

- Introduction to Level 1 (30 min)

- -

- Presentation of the regional dental and health training project in the Centre-Val de Loire region and the teaching team.

- -

- Definition and role of UISDs.

- -

- Initial questionnaire on “My vision of the observation internship”.

- General teaching module (1 h)

Presentation of teaching by objectives, introduction to teaching vocabulary. Contributions of conative pedagogy.

- -

- Definition of an objective.

- -

- Definition of a pedagogical activity.

- -

- Construction of a progression, explanation of the method.

- -

- Carrying out an assessment.

- -

- Development of corrective measures.

Quiz on the fundamentals of pedagogy.

The general module courses will be based on a video presentation.

- 3.

- Specific teaching module 2 h

- -

- How to teach in a dental practice? (Methodology)

- -

- Organization for welcoming trainees.

- -

- Observation and demonstration—(supervised work and independent work discussed but will be perfected in UISD level 2 and 3 training courses).

Group work on researching possible teaching activities in the practice Think-Share Pair (30 min).

Quiz on the role of the UISD/on the implementation of educational activities.

- 4.

- The observation internship (1 h)

- -

- Observation.

- -

- Trainer expectations.

- 5.

- Joint development of an internship program (1.5 h)

- -

- Objectives—evaluation criteria.

- -

- Joint work led by trainers.

Method: development of an evaluation grid as part of a collaborative project.

- 6.

- Update on dates and closing (30 min)

- -

- Final questionnaire on “My vision of the observation internship”.

- -

- Quality assessment (questionnaire).

- -

- Presentation of student groups.

- -

- Reminder of dates.

At the end of the session, the number and location of places will be known, as well as the reception arrangements (accommodation and travel). Students will be allocated places based on mobility criteria, accommodation and academic expectations.

Appendix B

Questionnaire administered before the training course

- Describe how you will support the student (the stages of your support, your interactions with them, your objectives, etc.).

- Specify how you will monitor the student’s progress during the internship.

- Do you plan to use any resources to help your student develop their skills?

If so, which ones? If not, why not?

- 4.

- What questions do you have about supporting a student?

- 5.

- What skills do you think you will need to support your student?

Appendix C

Questionnaire administered after training and welcoming interns.

- You have welcomed one or more students. What aspects of your UISD training did you draw upon in your support for them?

- You have welcomed one or more students. What elements of the training did you not use? For what reason(s)?

Given that professional skills are divided into three types of knowledge:

- Knowledge.

- Know-how.

- Interpersonal skills.

Try to answer the following questions:

- 3.

- What knowledge did you use?

- 4.

- What knowledge did you lack?

- 5.

- What skills (in your mentoring and UISD skills) did you use?

- 6.

- What skills (in your mentoring and UISD skills) would have been useful to enhance the support you provided?

- 7.

- What interpersonal skills (in your mentoring and UISD skills) did you use?

Thinking more broadly...

- 8.

- Did you use any management skills?

- 9.

- If so, which ones and for what purpose?

- 10.

- Did you use any communication skills?

- 11.

- If so, which ones and for what purpose?

- 12.

- Did you use other skills? If so, which ones and for what purpose?

- 13.

- Did you have to use skills outside your professional field (dental surgeon and MSUO)?

References

- Al-Yaseen, W.; Nanjappa, S.; Jindal-Snape, D.; Innes, N. A longitudinal study of changes in new dental graduates’ engagement with evidence-based practice during their transition to professional practice. Br. Dent. J. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, C.D.; Sheja, S.; Khanapur, G.D.; Chacko, R.K.; M, S.D. Gaps in Dentistry between Education and Professional Practice—A Theory–Practice Gap Analysis. J. Orofac. Res. 2025, 17, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, M.; Ravindran, T.K.S. Factors affecting preparedness for practice among newly graduated dentists—A cross-sectional study. J. Glob. Oral. Health 2020, 3, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moafa, I.; Jafer, A.; Almashnawi, M.; Hedad, I.; Hakami, S.; Zaidan, M.; Kaabi, A.A.; Abulqasim, H.; Jafer, M. Transitioning to Private Dental Practice: An in-depth exploration of dental graduates’ perspectives in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2024, 17, 777–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- General Dental Council. Preparedness for Practice: A Rapid Evidence Assessment; GDC: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, G.S.S.; Lim, T.W.; Braga, M.M. Embracing competency-based education for modern dental practice. Asia Pac. Sch. 2025, 10, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Décret n° 2002-482 du 8 Avril 2002 Portant Application au Système Français D’enseignement Supérieur de la Construction de L’espace Européen de L’enseignement Supérieur. Available online: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/jorf/id/JORFTEXT000000771048 (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Répartition de la Population des Chirurgiens-Dentistes. Available online: https://www.ordre-chirurgiens-dentistes.fr/cartographie/ (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Le Règlement Général sur la Protection des Données—RGPD 24 Mai 2016. Available online: https://www.cnil.fr/fr/reglement-europeen-protection-donnees (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Kirkpatrick, D. Great ideas revisited. Train. Dev. 1996, 50, 54. [Google Scholar]

- Berthier, N. Les Techniques D’enquête en Sciences Sociales; Armand Colin: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Benè, K.L.; Bergus, G. When learners become teachers: A review of peer teaching in medical student education. Fam. Med. 2014, 46, 783–787. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Flanagan, J.; Smith, R. Competency Based Training for Clinical Supervisors, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Minouei, M.S.; Omid, A.; Yamani, N.; Nasri, P.; Ahmady, S. Enhancing clinical faculties’ knowledge, attitudes, and performance in clinical supervision: A workplace-based faculty development program using proctor’s model. BMC Med. Educ. 2025, 25, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, S.; Spurr, P.; Sidebotham, M.; Fenwick, J. Describing and evaluating a foundational education/training program preparing nurses, midwives and other helping professionals as supervisors of clinical supervision using the Role Development Model. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2020, 42, 102671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGill University School of Physical & Occupational Therapy. Training for Clinical Supervision [Internet]; McGill University: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2026; Available online: https://www.mcgill.ca/spot/fr/formation-clinique/formation-pour-la-supervision-de-stage (accessed on 17 January 2026).

- Modalité de Mise en Place D’une Réforme du Troisième Cycle des Études Odontologiques. Available online: https://www.igas.gouv.fr/modalites-de-mise-en-place-dune-reforme-du-troisieme-cycle-des-etudes-odontologiques-0 (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- Bulte, C.; Betts, A.; Garner, K.; Durning, S. Student teaching: Views of student near-peer teachers and learners. Med. Teach. 2007, 29, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, M. Repère 2. Comprendre ce qu’accompagner veut dire: Les fondamentaux. Perspect. En Éducation Et Form. 2020, 2, 37–59. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, K.; Gordon, J.; MacLeod, A. Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: A systematic review. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. Theory Pract. 2009, 14, 595–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shorey, S.; Chan, V.; Rajendran, P.; Ang, E. Learning styles, preferences and needs of generation Z healthcare students: Scoping review. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2021, 57, 103247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hrdy, M.; Tarver, E.M.; Lei, C.; Moss, H.C.; Wong, A.H.; Moadel, T.; Beattie, L.K.; Lamberta, M.; Cohen, S.B.; Cassara, M.; et al. Applying simulation learning theory to identify instructional strategies for Generation Z emergency medicine residency education. AEM Educ. Train. 2024, 8, S56–S69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bratu, M.L.; Cioca, L.I.; Nerisanu, R.A.; Rotaru, M.; Plesa, R. The expectations of generation Z regarding the university educational act in Romania: Optimizing the didactic process by providing feedback. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1160046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.