Abstract

Magnetoliposomes are hybrid nanostructures that integrate superparamagnetic ultrasmall carbon-coated ferrite nanodots (MNCDs) within liposomes (Lipo) composed of egg yolk-derived phospholipids and stabilized with an environmentally benign potato peel extract (PPE), enabling enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and optical imaging. The hydrothermally synthesized MNCDs were entrapped in liposomes prepared by thin-film hydration, and physicochemical properties were established at each stage of engineering. These magnetoresponsive vesicles (MNCDs+Lipo@PPE) serve as a triple-mode medical imaging contrast for T1 & T2-weighted MRI, while simultaneously enabling optical tracking of liposome degradation under an external magnetic field. They exhibited long-term enhanced fluorescence intensity and colloidal stability over 30 days, with hydrodynamic diameters ranging from 190 to 331 nm and an improved surface charge following PPE coating. In vitro cytotoxicity assays (MTT and Live/Dead staining) demonstrated over 87% cell viability for MNCDs+Lipo@PPE up to 2.7 mM concentration in A549 cells, indicating considerable toxicity. This multimodality engineering facilitates precise image-guided anticancer doxorubicin delivery and magnetic-responsive controlled release. The theoretical model shows that the release profile follows the Korsmeyer-Peppas profile. The externally applied magnetic field enhances the release by 1.4-fold. To demonstrate the anticancer efficiency in vitro with minimum off-target cytotoxicity, MTT and live/dead cell assay were performed against A549 cells. The reported study is a validated demonstration of magnetic-responsive nanocarrier systems for anticancer therapy and multimodal MRI and optical imaging-based diagnosis.

1. Introduction

Magnetic nanoparticles (MNP) are of special interest due to their small size and specific magnetochemical properties. These features make them particularly attractive for anticancer therapies, including hyperthermia, in which external magnetic fields could be used to address specific therapeutic sites within the body. Ferrite nanoparticles with high magnetization, good physicochemical stability, and superparamagnetic behavior are most commonly used in biomedicine. The form, size distribution, surface effects, and magnetic properties of these nanoparticles strongly depend on the synthesis techniques. They tend, however, to form aggregates, so it is suspect from a health point of view. Several encapsulation or coating strategies have been reported by researchers involving liposomes, hydrogels, and biodegradable polymers to bypass these limitations. These coating structures are made of non-toxic, biocompatible molecular assemblies and can accommodate both hydrophobic/hydrophilic drugs or biomolecules; liposomes in particular are an appealing example of these. When magnetic nanoparticles are encapsulated in liposomes, their behavior and occlusion within the body are enhanced while the magnetic properties are conserved.

Over the past few years, MRI has become a crucial diagnostic technique for deep-seated cancerous tissue and monitoring therapeutic responses and progression [1,2,3]. It relies on the magnetic properties of water molecules present in tissues and proton relaxation times in longitudinal (T1) and transverse (T2) planes [4,5]. In MRI, two types of contrast are typically generated: T1-weighted and T2-weighted images, which use magnetic gadolinium (Gd) chelates or superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles, or SPIONs, to enhance contrast (CAs) [6,7]. Liu et al. created a multifunctional Gd-nanoprobe that enhances MRI signal sensitivity, tumor targeting, and radiation sensitivity by combining bioorthogonal click chemistry with theranostic properties [8]. Through biomimetic mineralization, BSA and Gd ions were used to create nanoparticles, which were subsequently functionalized with dibenzocyclooctyne to create the probe. Compared to the standard clinical contrast agent Gd-DTPA (Magnevist), which has a r1 value of 3.8 mM−1s−1, the Gd-nanoprobe formulation exhibited a significantly higher r1 of approximately 25 mM−1s−1, nearly seven times greater [8]. Nevertheless, they are not without risk, especially among patients with reduced renal function; the long-term persistence in the kidneys can cause nephrogenic systemic fibrosis [9,10,11]. In contrast, contrast agents based on SPIONs are less used owing to the generation of negative contrast and lower penetration in tissue [12]. Therefore, new magnetic nanomaterials as contrast agents in MRI are becoming highly required to have a higher contrasting effect and better imaging properties for biomedical applications [13,14].

Fluorescent nanomaterials show particular promise in this regard, as they offer substantial stability, lower dosages, and the possibility for theranostic imaging [15,16], i.e., the use of a diagnostic material in combination with a potential therapy. With MRI contrast agents becoming more and more specialized for both imaging and therapeutic purposes [17,18], the breakthroughs described above can propel us closer to a new world of precision diagnostics. Carbon family representatives called carbon dots (CD) established their strong foundation numerically and technically in fluorescent nanomaterials and seem to be one of the most currently represented contrast agents for the resolution of addressable problems compared to the prior traditional contrast agent (CAs) [19,20,21,22]. Hojjati et al. developed a theragnostic system based on magnetic mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MMSN) loaded with regorafenib capped by graphene quantum dots (GQDs) [23]. Regorafenib encapsulated in MMSN and GQDs resulted in excellent pH-dependent drug release, while GQDs maintained their drug release. It also exhibited efficient cytotoxicity against the SW-480 cell line while maintaining biocompatibility. Stepanidenko et al. developed CDs doped with manganese chloride from O-phenylenediamine and citric acid, exhibiting good r1 and r2 relaxivity values and decreased relaxation times of T1 and T2 [24]. These findings collectively report that both Manganese and magnetic nanoparticles entrapped in fluorescent carbon nanomaterials could efficiently serve as potential CA for MR imaging along with optical imaging, overcoming the problems faced by traditional CAs. This entrapment also improved their biocompatibility moderately, as well as their catalytic activity in terms of ROS generation, enabling them to be used in both environmental and bio-imaging applications. As a result of the inherently weak surface chemical and physical properties of particles, dispersing them is often challenging [25,26].

In order to circumvent these drawbacks, the surfaces of CDs are required to be functionalized with polymers, liposomes, and MOFs [27,28]. This enables better particle stability (biodegradability, degradation time, less toxicity, better surface for more biocompatibility on the particle [29,30]. Liposomes are a well-established drug release system (DRS) to deliver payloads to destination sites [31,32]. These assemble cholesterol and phospholipids to create a membrane of lipid bilayer containing both hydrophilic and hydrophobic elements [33,34]. The entrapment of CDs into the lipid bilayer of liposomes presents many benefits, such as improved encapsulation efficiency, biocompatibility, optimal payload-delivering properties, and degradation rates [35,36]. Ren et al. encapsulated carbon dots with liposomes loaded with cinobufagin and studied their application in vivo and in vitro [37]. This system could effectively improve fivefold the fluorescence of the CD, the uptake of the CD by cells, and its anticancer effects. Demir et al. prepared a multi-functional theragnostic material. By co-encapsulating CDs and curcumin (Cur) into anti-CD44 antibody functionalized liposomes [38]. Consequently, the anticancer efficacy of the Anti-CD44 functionalized Cur/CD-loaded liposomes was more effectively improved than that of the Cur-loaded liposomes and the Cur/CD-loaded liposomes, and the bioimaging also exhibited an improvement.

Potato peel is the most abundant byproduct generated in the potato processing industry, accounting for a significant portion of agro-industrial waste and containing valuable bioactive compounds such as dietary fibers, polyphenols, and starch [39,40,41]. It contains more abundant polyphenols, starch, and flavonoids than potato flesh, which enables it to act as an antioxidant naturally. Potato peel extract (PPE) has been extensively studied by researchers for its antioxidant activity, oxidative damage, and antimicrobial properties [42,43]. Using aqueous extracts of potatoes, their peels, and their leaves, Himanshu et al. developed iron nanoparticles and evaluated their capacity to degrade methylene blue dye via photocatalysis [44]. When exposed to sunlight, the synthesized nanoparticles demonstrated efficient dye degradation. With 99% degradation in 120 min, the NPs made from potato peel extract performed the best out of all of them. Their optimal band gap, larger surface area, and smaller crystallite size were associated with this superior activity, which aided in accelerating first-order kinetics. Through various research analyses, this study aims to develop carbon-coated manganese ferrite-based magnetoliposomes that hold doxorubicin as an anticancer drug and are surface-functionalized by PPE (MNCDs+Lipo@PPE). PPE was chosen to stabilize the magneto-liposomes because it offers excellent biocompatibility and biodegradation rates. The engineered MNCDs+Lipo@PPE were characterized using various techniques, tested in vitro for biocompatibility, and employed for multimodal medical imaging and therapy.

2. Materials and Methods

Urea (CH4N2O), Ferric Chloride (FeCl3·6H2O), Citric Acid (C6H8O7), and Manganese Chloride (MnCl2·4H2O), and Doxorubicin hydrochloride were procured from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA while Cholesterol, Methanol, ethidium bromide, Sodium Chloride (NaCl), acridine orange, and MTT reagent were obtained from Himedia Laboratories, Mumbai, India. Chloroform was bought solely from SRL India Ltd., Mumbai, India. Potatoes and eggs were bought at a local market near Kelambakkam, Chennai, India. For cell culture studies, DMEM medium, antibiotic solutions, and FBS (fetal bovine serum) were acquired from Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA. All experiments were performed with sterile distilled water, and chemicals were used without purification.

2.1. Synthesis of Magnetic Carbon Dots (MNCDs)

Magnetic carbon dots (MNCDs) were fabricated according to a modified version of the synthesis method reported in the literature [45]. In summary, FeCl3 0.20 M in 50.0 mL of deionized water, and 0.1 M of MnCl2 was added to it. The blend was then mechanically stirred and homogenized. A 2:1 ratio of urea and citric acid was introduced during stirring, which then formed a colloidal suspension. The obtained solution was transferred into a Teflon-coated stainless steel hydrothermal autoclave and heated in a hot air oven for 12 hrs at 160 °C and cooled to room temperature. To get rid of unreacted molecules, the resulting solution was centrifuged for 15 min at 15,000 RPM and then rinsed four to five times with distilled water. The pellet was dried at 100 °C on a hot plate. Magnetic carbon dots (MNCDs) were then created by grinding the dried pellet into a powder with a mortar and pestle.

2.2. Synthesis of Liposomes Encapsulated MNCDs (MNCDs+Lipo)

Liposomes were prepared from phospholipids extracted from egg yolk [46]. One mL of egg yolk was transferred to a fresh tube, followed by 3 mL of 1 M NaCl, and then vortexed vigorously. A 2:1 ratio of methanol and chloroform was added and mixed well. This was followed by adding 1 mL of 1 M NaCl and 3 mL of chloroform and vortexing the mixture. The resulting solution was centrifuged for 5 min at 2500 RPM. Centrifugation resulted in three different layers. The lowermost organic phase contained phospholipids. These phospholipids were washed and re-suspended in a new tube and frozen at −20 °C until used. For liposome preparation, 20 µL of phospholipids was taken in a round-bottom (RB) flask. Then, 2 mg of cholesterol, 2.0 mL of CH3OH (methanol), and 8.0 mL of CHCl3 (chloroform) were added and evaporated under vacuum using a rotary evaporator. The dried mixture was collected as thin films on the walls of the RB flask and stored overnight in a desiccator at 25 °C or room temperature under vacuum. The RB flask with thin films was sonicated for 15 min at room temperature the next day with 10 mL of PBS. It was then kept at 4 °C until it was needed again. Equal volumes of MNCDs and synthesized liposomes were taken in a beaker and sonicated for 15 min at room temperature for the preparation of Liposomes encapsulated MNCDs (MNCDs+Lipo). Encapsulation of Dox was achieved by mixing 1 mg/mL of Dox with an equal volume of liposome to form a 1:1 ratio and sonicated for 20 min at room temperature.

2.3. Preparation of PP Extract-Coated Liposomes Encapsulated MNCDs (MNCDs+Lipo@PPE)

PPE (potato peel extract) was prepared by procuring potatoes from a local market near Kelambakkam. The potatoes were peeled, and the peels were washed and dried at 60 °C. Then, the dried peels were boiled in water at 100 °C, and the obtained solution was centrifuged for 10 min at 3000 RPM. The supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube and stored at 4 °C for further use. 200 µL of PP extract was added to liposomes-encapsulated MNCDs and incubated for 15 min at room temperature, resulting in the successful synthesis of MNCDs+Lipo@PPE. Dox-loaded (1 mg/mL & 1:1) magnetic liposomes were also coated with PPE using the same protocol to obtain MNCDs+Lipo@PPE+Dox.

2.4. Instrumentation

We used a UV-1900 spectrophotometer, Kyoto, Japan, to obtain the UV-Vis absorption spectrum and a Jasco FP-3800 spectrofluorometer, Tokyo, Japan, to obtain the fluorescence spectrum. Functional groups were identified through analysis using a Bruker-Alpha FTIR spectrophotometer, Billerica, MA, USA. Hydrodynamic diameter and Zeta potential (ζ) were measured using a Malvern Nano ZS-90 size analyzer, Worcestershire, UK. The magnetic properties of MNCDs were measured using a Lakeshore 7410 vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM), Westerville, OH, USA. Optical imaging was conducted using an IVIS® LUMINA LT system, Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed on a GE Signa HDxt 3T MRI scanner, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. XPS measurements were taken with XPS, ULVAC-PHI, Chigasaki, Japan. An Olympus BX51 fluorescence microscope, Olympus, Gurgaon, India, was used for fluorescence cell imaging.

2.5. Colloidal Stability Measurement

The stability of MNCDs, MNCDs+Lipo, and MNCDs+Lipo@PPE was evaluated based on their fluorescence intensity, hydrodynamic size, and surface charge in terms of zeta potential using a spectrofluorometer and dynamic light scattering (DLS). Samples were stored at both 4 °C and room temperature (25–27 °C) and monitored for 30 days, with measurements taken every 5 days to assess changes in hydrodynamic diameter, fluorescence emission intensity, and Zeta potential [47,48].

2.6. Optical and MR Imaging

Intensifying concentrations of MNCDs, MNCDs+Lipo, and MNCDs+Lipo@PPE were implemented into water phantoms in a 24-well plate at room temperature. The water phantoms were subjected to MR imaging under T1- and T2-weighted MR protocols using the Philips Ingenia 3.0 T MRI scanner. T1-weighted flair imaging sequence was obtained with a slice thickness of 2 mm, 3000 ms of TR, 14 ms of TE, a voxel of 12 × 12 matrix, and variable TI from 400 ms to 2000 ms. For the T2-weighted spin-echo sequence, a 2 mm slice thickness, followed by a FOV of 12 × 12, with TR of 3000 ms, variable TE at 10–100 ms, and echo train length of 12 ms. Phantom imaging ability was assessed by using an IVIS optical animal imaging system. The fluorescence image was acquired using an excitation band of 530 nm, with samples in a 96-well plate at increasing concentrations.

2.7. MTT Assay

The biocompatibility of MNCDs, MNCDs+Lipo, and MNCDs+Lipo@PPE and anticancer effects of Lipo+Dox, MNCDs+Lipo+Dox, and MNCDs+Lipo@PPE+DOX were evaluated using the MTT assay. A549 (human lung cancer cells) were grown in DMEM media with FBS (10%) along with the required antibiotic solution (1%), at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere for these tests. The cells were planted onto sterile 48-well plates with a new DMEM solution and raised for 24 h to adhere. Following this, A549 cells were exposed to varying concentrations (0.31, 0.5, 1.1, 1.7, 2.2, and 2.7 mM) of the test formulations for 24 h. After 24 h of treatment, MTT reagent (5 mg/mL) was added to each well under dark conditions and incubated for 4 h to enable the formation of formazan crystals. The resulting crystals were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and absorbance was recorded at 570 nm. Cell viability was determined from the OD values, expressed as a percentage relative to untreated controls [49].

2.8. Live/Dead Assay

The Live/Dead assay was performed using Acridine Orange (AO) and Ethidium Bromide (EtBr) dual staining to evaluate both the biocompatibility of MNCDs, MNCDs+Lipo, and MNCDs+Lipo@PPE and the anticancer activity of Lipo+Dox, MNCDS+Lipo+Dox, and MNCDS+Lipo@PPE+Dox. For these assays, A549 cells were cultured on sterile coverslips in DMEM culturing media complemented with 10% serum (fetal bovine serum or FBS) and 1% antimycotic-antibiotic solution and maintained at 37 °C in a humidified CO2 incubator to maintain 5% level. After 24 h of initial incubation to allow cell attachment, the cells were treated with the lowest (0.31 mM) and highest concentrations (2.7 mM) of the test formulations and further incubated for 24 h. Following treatment, the medium was removed, and a freshly prepared mixture of 100 μg EtBr and AO each in 1 mL in PBS was supplemented to the cells. The plates were incubated for 3 min in the dark, and excess dye was carefully washed away. Live cells exhibited green fluorescence due to AO uptake, whereas dead/apoptotic cells displayed orange-red fluorescence from EtBr binding. Imaging was performed using a fluorescence microscope, enabling qualitative visualization of cell survival (biocompatibility) and cell death (anticancer activity) [50,51].

2.9. Encapsulation Efficiency

Dox was chosen as the drug to load into the nanostructures at a concentration of 1 mM. For this, 1 mL of Dox was sonicated with Lipo, MNCDs+Lipo, and MNCDs+Lipo@PPE for 15 min at room temperature. To calculate the encapsulation efficiency of Dox into nanostructures, the formula mentioned below was utilized. All three formulations were subjected to centrifugation at 15,000 RPM for 15 min, and the supernatant of the formulations was measured at 498 nm using a UV spectrophotometer.

where OD(i) = Initial OD of the drug in the system, and OD(s) = OD of supernatant

2.10. Drug Release Kinetics

The doxorubicin release profile from the MNCDs+Lipo@PPE+Dox formulation was carried out in PBS at pH 7.4, using a standard membrane diffusion method. A total of 2 mL of MNCDs+Lipo@PPE+Dox was loaded in two different dialysis membranes and immersed in 25 mL of pH 7.4 PBS in a beaker separately, where one beaker was subjected to magnetic stirring and the other one was kept normal. Every 30 min for 8 h, 2 mL of the drug was taken out of each beaker, and the absorbance was measured at 498 nm to determine how much was released. To keep the final volume the same, 2 mL of fresh PBS was added to the beaker every time while 2 mL was taken out. The formulation’s dox release profile was studied by plotting drug release percentages versus time of release or intervals.

To elucidate the Dox release kinetic behavior from MNCDs+Lipo@PPE, the Korsmeyer–Peppas model was employed. This empirical model is beneficial when the release mechanism is complex or not well-defined, often involving multiple contributing phenomena. The experimental release profiles were analyzed by fitting the data to the Korsmeyer–Peppas equation, as represented in the following equation.

In this model, Qt and Q∞ represent the cumulative amount of drug released at a specific time t and at equilibrium, respectively. The constant k is a release rate constant that reflects the structural and geometric characteristics of the nanoparticles. The term n denotes the diffusion exponent, which provides insight into the underlying release mechanism.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Structural and Magnetic Properties

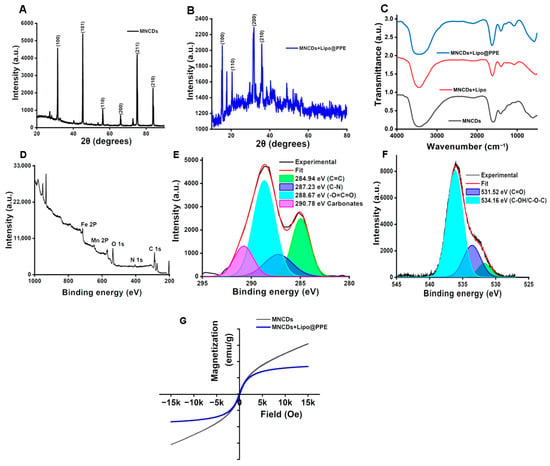

X-ray diffraction patterns of MNCDs and MNCDs+Lipo@PPE are shown in Figure 1A,B. MNCDs exhibited a notable, distinct peak (2θ) at 30.2° corresponding to the cubic spinal structure of MNCDs assigned to the (220) crystal plane (JCPDS card no. 74-2403) [52]. The persistence of this diffraction peak in the MNCDs+Lipo@PPE composite confirms that the crystalline lattice of MNCDs was preserved during liposomal encapsulation and subsequent surface functionalization with PPE. Figure 1B shows a broad peak from 20 to 25 °C, which is indicative of the amorphous nature of the lipid bilayer and bio-organic constituents present in PPE [53]. FTIR spectra, Figure 1C, were acquired to analyze the functional groups in the MNCDs, MNCDs+Lipo, and MNCDs+Lipo@PPE. It was established that metal oxide was produced via Fe–O bond vibration at 586 cm−1. The distinct broad peak at 3572 cm−1 to 3327 cm−1 is ascribed to the O–H bond due to the stretching vibration of -O–H groups. The symmetric bending vibration, as well as the asymmetric vibration of C=O, causes a band at 1412 cm−1 and 1631 cm−1. The C–N bond stretching was observed at 1178 cm−1 and the N–H stretching at 3449 cm−1. All the observed FTIR peaks support the formation of MNCDs. Similar peaks for N-H stretching at 3448 cm−1 were observed for MNCDs+Lipo, with the existence of peaks at 3448 cm−1 ascribing to the presence of primary amines and a band at 1629 cm−1. Bands at 2697 cm−1, 1635 cm−1, and 1402 cm−1 correspond to C–H stretching, C=O stretching, and C–H bending present in MNCDs+Lipo@PPE. XPS is a crucial surface analytical technique that offers detailed insights into the elemental composition and chemical states of atoms within the outermost atomic layers of carbon dots (CDs). The XPS spectra across the full range (250–1250 eV) revealed characteristic peaks corresponding to the binding energies of Fe (713.81 eV), Mn (645.78 eV), oxygen O 1s (533.78 eV), nitrogen N 1s (403.78 eV), and carbon C 1s (287.73 eV), confirming their presence in the sample Figure 1D. The C 1s Figure 1E spectrum reveals a prominent peak near 284.8 eV, attributed to graphitic carbon, along with additional components associated with oxygenized carbon type such as C–O and O–C=O, confirming the presence of a surface carbon layer. The O 1s Figure 1F peak centered around 531.52 eV suggests contributions from both metal-oxygen bonds in the ferrite matrix and surface-bound hydroxyl or carbonyl groups. Notably, the N 1s signal observed around 403.73 eV implies the presence of nitrogen-containing functional groups, which may originate from nitrogen doping or precursor residues [54]. Figure 1G shows the hysteresis curve of MNCDs and MNCDs+Lipo@PPE, plotted by magnetization vs. Field (Oe), which shows an apparent anhysteretic curve (S-shaped) indicating their superparamagnetic behavior, which is useful for MR imaging, as superparamagnetic nanoparticles can generate strong local magnetic field inhomogeneities that shorten the transverse relaxation time (T2) of nearby protons. This results in enhanced image contrast in T2-weighted MRI scans, allowing for improved visualization and differentiation of pathological tissues. Therefore, the observed superparamagnetic nature of MNCDs and MNCDs+Lipo@PPE makes them promising candidates for use as efficient MRI contrast agents [55].

Figure 1.

(A) X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of MNCDs showing the characteristic cubic spinel ferrite reflection. (B) XRD spectrum of MNCDs+Lipo@PPE indicating preservation of MNCD crystallinity with an additional amorphous contribution from the lipid bilayer and PPE coating. (C) FTIR spectra of MNCDs, MNCDs+Lipo, and MNCDs+Lipo@PPE. (D) Survey XPS spectrum of MNCDs. (E,F) High-resolution deconvoluted XPS spectra of C 1s and O 1s. (G) Room-temperature VSM anhysteretic loops of MNCDs and MNCDs+Lipo@PPE demonstrating superparamagnetic behavior.

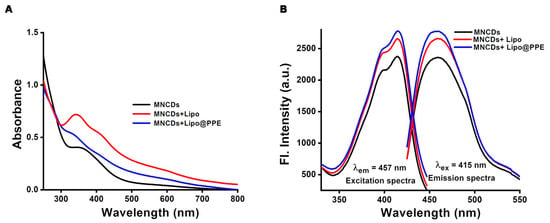

3.2. Optical Properties

As shown in Figure 2A, the UV-Vis spectrophotometric analysis of the synthesized MNCDs revealed a broad absorption range from 350 to 420 nm, with a λmax centered at 357 nm and 415 nm. The absorption spectra of MNCDs+Lipo exhibited a slight hypsochromic shift in λmax, with increased absorption due to the interaction between the MNCDs and the lipid bilayer of the liposomes, which in turn altered the electronic structure of the MNCDs. The MNCDs+Lipo@PPE showed a similar broad absorption in the 320–340 nm range due to π-π* transition of the conjugated system. The reduced optical density can be attributed to changes in the microenvironment after PPE encapsulation. The spectrofluorometric observations revealed that, in comparison to MNCDs alone, the fluorescence emission intensity of liposomes changed significantly when MNCDs were entrapped into them [37]. Therefore, MNCDs+Lipo exhibit increased emission intensity around 457 nm (Figure 2B), and they shifted slightly toward the blue end of the spectrum. More significantly, the addition of a PPE layer outside the liposomes in MNCDs+Lipo@PPE further intensified the emission behavior. This implies that adding MNCDs to liposomes and stealth liposomes is a simple method of enhancing their emission properties. It is known that the surface groups of MNCDs, such as amino, hydroxyl, and carboxyl, can influence their interactions with other coating materials, particularly polymers or lipids, although the precise cause of their emission behavior remains unclear [56]. The fact that surface radical reactions, internal molecular rotations, and other nonradiative decay processes frequently impair the emission efficiency of MNCDs is one of their main problems. These issues reduce the MNCDs’ fluorescence by causing the energy they absorb to be lost in a nonradiative pathway. These restrictions seem to be lessened when MNCDs are encapsulated in liposomes as well as stealth liposomes. The confined, nanoscale environment of liposomes may aid in limiting the motion of MNCDs (such as rotation and vibration) and minimizing undesired surface interactions. Their emission intensity increases as a result of more energy being directed toward light emission in a radiative pathway and less energy being lost to nonradiative processes [57]. It is therefore evident that, by establishing a more stable and regulated microenvironment around MNCDs, MNCDs+Lipo and MNCDs+Lipo@PPE appear to improve their optical performance. The liposomal encapsulation of MNCDs would prevent aggregation and stabilize MNCDs.

Figure 2.

(A) MNCDs, MNCDs+Lipo, and MNCDs+Lipo@PPE absorption spectra. (B) Emission and excitation spectra of MNCDs, MNCDs+Lipo, and MNCDs+Lipo@PPE.

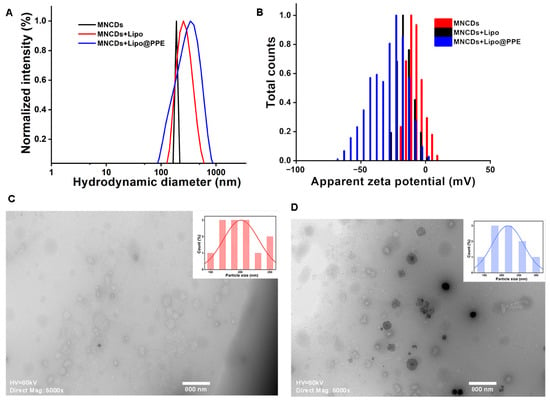

3.3. Particle Size Analysis and Zeta Potential Measurement

A particle size analyzer was utilized based on the dynamic light scattering principle to assess the hydrodynamic diameter and polydispersity index (PDI). The PDI is a dimensionless parameter that denotes the degree of dispersion of solutes in colloidal solutions [58]. As shown in Figure 3A, MNCDs, MNCDs+Lipo, and MNCDs+Lipo@PPE showed a hydrodynamic diameter (dH) of 190 nm, 280.3 nm, and 331.9 nm with PDI of 0.9, 0.3, and 0.5, respectively. These results conclude that the synthesized nanoparticle is monodispersed. The zeta potential analysis was carried out to assess the stability of particles and successive encapsulation and immobilization with liposomes and potato peel extract. Figure 3B shows the zeta potential value of MNCDs, MNCDs+Lipo, and MNCDs+Lipo@PPE of −3.89 mV, −15.8 mV, and −28.8 mV. After encapsulating the MNCDs into liposomes, the zeta potential changed from −3.89 mV to −15.8 mV; after that, successive immobilization with PPE further improved its zeta potential value to −28.8 mV, proving that PPE@L-MNCDs is stable.

Figure 3.

(A) Hydrodynamic diameter obtained from dynamic light scattering studies. (B) Zeta potential of MNCDs, MNCDs+Lipo, and MNCDs+Lipo@PPE (C) TEM image of Liposomes. (D) TEM image of MNCDs+Lipo@PPE showing encapsulated magnetic core in liposomes.

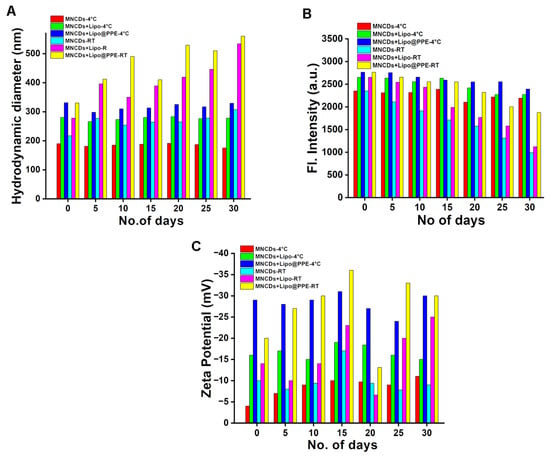

3.4. Stability Analysis

The long-term colloidal stability of MNCDs, MNCDs+Lipo, and MNCDs+Lipo@PPE was systematically evaluated under controlled storage conditions (4 °C and Room temperature). Samples were stored at 4 °C (refrigerated) and 25–27 °C (room temperature) for 30 days. Temporal changes in key colloidal properties were quantified at 5-day intervals using the following analytical methods: Hydrodynamic diameter, Fluorescence emission intensity, and Zeta potential Figure 4. Samples stored at 4 °C demonstrated greater stability in emission intensity, size, and surface charge compared to those kept at room temperature, making them more suitable for long-term applications.

Figure 4.

Stability graph of MNCDs, MNCDs+Lipo, MNCDs+Lipo@PPE stored at 4 °C and room temperature. (A) Hydrodynamic diameter, (B) Emission intensity, (C) Surface charge.

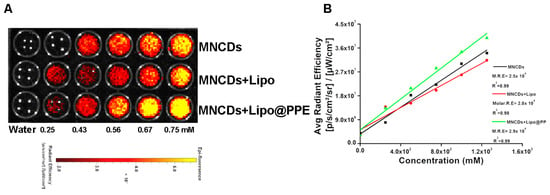

3.5. Phantom Optical Imaging

MNCDs, MNCDs+Lipo, and MNCDs+Lipo@PPE were tested under the IVIS animal imaging system to demonstrate their ability as probes for fluorescence imaging. Figure 5A shows the increasing fluorescence intensities of MNCDs, MNCDs+Lipo, and MNCDs+Lipo@PPE tested in a 96-well plate with increasing concentrations. Background intensities were subtracted from their corresponding intensities and normalized to photons/second/centimeter2/steradian (p/s/cm2/sr). The average radiant efficiencies of MNCDs, MNCDs+Lipo, and MNCDs+Lipo@PPE are shown in Figure 5B with their slope values of 2.5 × 104, 2.0 × 104, and 2.9 × 104 p/s/cm2/sr per mM. These results suggest that MNCDs+Lipo@PPE has improved radiant efficiencies when compared to MNCDs+Lipo and MNCDs, which is also proven by steady-state fluorescence spectra.

Figure 5.

(A) Increasing concentrations of MNCDs, MNCDs+Lipo, and MNCDs+Lipo@PPE were observed under the Phantom optical imaging system. (B) Concentrations vs. Avg Radiant Efficiency to calculate Molar Radiant Efficiencies (MRE).

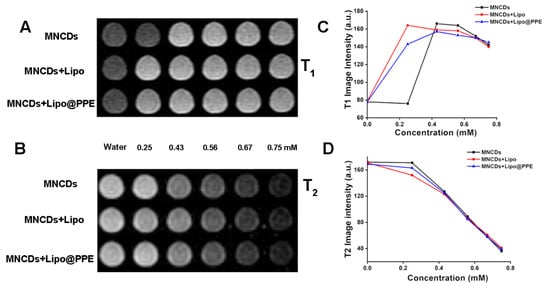

3.6. T1 and T2-Weighted MR Imaging

An in vitro MR imaging study was conducted to assess the capabilities of MNCDs, MNCDs+Lipo, and MNCDs+Lipo@PPE as contrast agents. Samples were prepared in a 24-well plate with increasing concentrations, using water as a control, and monitored with a 3T MRI scanner. The intensities from each well were measured using ImageJ 1.52a and MicroDICOM 2024.3 image processing software. The measurements indicated that the intensities of each well with samples are directly proportional to the concentration of samples present in each well. Figure 6A,B demonstrate the T1 and T2-weighted imaging capabilities of the synthesized samples. The intensities were plotted in Figure 6C for T1 and in Figure 6D for T2. The T1 intensity for MNCDs remains the same as water at 0.25 mM, but at the same concentration, MNCDs+Lipo demonstrated a better contrasting capacity. It is clearly observed that the liposomal encapsulated MNCDs are a better contrast than the free MNCDs. MNCDs+Lipo@PPE showed a similar behavior to MNCDs+Lipo, but with slightly less intensity. Further increasing concentrations for MNCDs show better T1 contrasting, as formulations like MNCDs+Lipo and MNCDs+Lipo@PPE showed at a lesser concentration, followed by a plateau. The increasing intensity was due to the shortening of the longitudinal relaxation time, representing the optimum T1. At the highest concentration range, the intensity began to decrease as the T2 shortening effect started to dominate for all three particles. Figure 6D represents the reduction in T2 intensity, and all three particles show a similar T2 effect, but MNCDs+lipo has better T2 contrasting capacity than the other two due to the local field inhomogeneity. The paramagnetic contrast agents generate local disturbances in the surrounding magnetic field, and protons from water diffuse through these regions to dephase the spin more quickly.

Figure 6.

(A) T1-weighted MRI images of MNCDs, MNCDs+Lipo, MNCDs+Lipo@PPE. (B) T2-weighted MRI images of MNCDs, MNCDs+Lipo, MNCDs+Lipo@PPE. (C) Variation in T1 signal intensity with varying concentration of MNCDs, MNCDs+Lipo, MNCDs+Lipo@PPE. (D) Variation in T2 signal intensity with varying concentration of MNCDs, MNCDs+Lipo, MNCDs+Lipo@PPE.

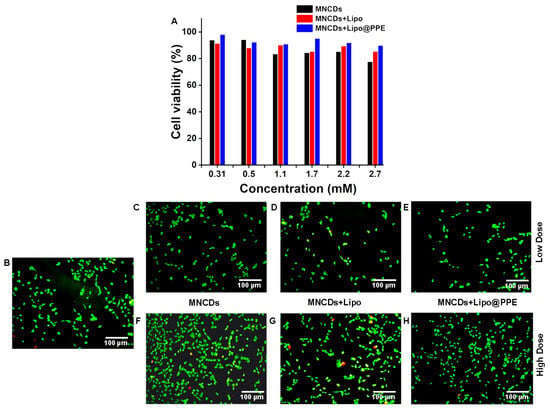

3.7. Toxicity Analysis

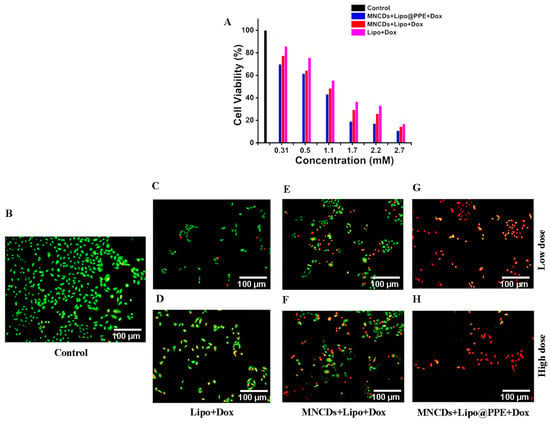

An MTT assay was conducted to assess the in vitro cell toxicity of all formulations on A549 cells. According to MTT results, MNCDs are more toxic than the other two formulations; however, it is apparent that PPE immobilization improves the biocompatibility of the formulations, as evident from Figure 7A, which shows increased cell viability for A549 cells. Two different concentrations of MNCDs, MNCDs+Lipo, and MNCDs+Lipo@PPE were applied to A549 cells (adenocarcinoma human alveolar basal epithelial cells) to evaluate their cellular toxicity. To assess the live and dead cells, a double-staining protocol utilizing Acridine orange and Ethidium bromide was used (Figure 7B–H). All three formulations exhibited over 87% cell viability in A549 cells. Low doses (Figure 7C–E) of MNCDs and related formulations do not show significant toxicity compared with the control (Figure 7B). At high doses (Figure 7F–H) of MNCDs, a cell viability of 89.2%, while MNCDs+Lipo and MNCDs+Lipo@PPE reported cell viability percentages of 91% and 93.5%, respectively. MNCDs exhibited toxicity due to the presence of manganese, whereas in MNCDs+Lipo and MNCDs+Lipo@PPE, subsequent coating with liposomes and the immobilization of potato peel extract, which masks the manganese in the core, are responsible for exhibiting toxicity.

Figure 7.

(A) Viability of A549 cells treated with different concentrations of MNCDs, MNCDs+Lipo, and MNCDs+Lipo@PPE, (B) Control, (C,F) Low and High doses of MNCDs. (D,G) Low and High doses of MNCDs+Lipo (E,H) Low and High doses of MNCDs+Lipo@PPE. (Green: Live cells, Red: Dead cells).

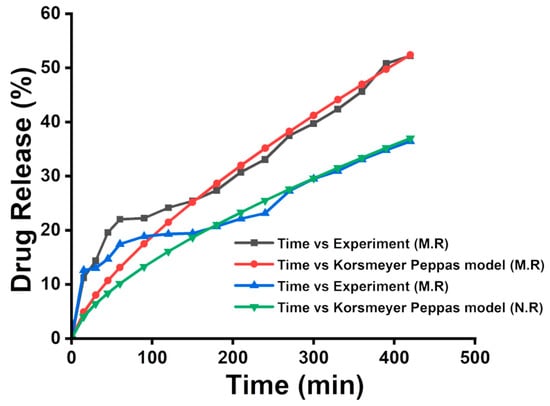

3.8. Encapsulation Efficiency and Drug Release Patterns

The drug loading efficiency of MNCDs+Lipo@PPE+Dox was found to be 62.6%, which was monitored at 498 nm. The drug release profile of doxorubicin from the MNCDs+Lipo@PPE nanoformulation was evaluated under magnetic field (MR) and normal conditions (N.R). As illustrated in Figure 8, the experimental data revealed a significantly higher cumulative drug release under the influence of the magnetic field, reaching approximately 52% at 480 min, compared to 36% under normal conditions. This enhanced release in the presence of the magnetic field is attributed to the magnetic responsiveness of the MNCDs, which facilitates increased nanoparticle mobility and interaction with the surrounding medium [59]. The movement induced by the magnetic field likely accelerated the disruption of the liposomal membrane and promoted drug diffusion.

Figure 8.

Drug release profile of Dox loaded into MNCDs+Lipo+PPE under the influence of a Magnetic field, and the Normal state and Korsmeyer-Peppas model were used to fit the release profile of Dox from MNCDs+Lipo+PPE.

The drug release profile of Dox from MNCDs+Lipo@PPE was identified by the Korsmeyer Peppas model. The r, k, and n values of both MR and N.R were 0.98, 0.71, 0.5, and 0.93, 0.66, and 0.5. The drug release data at pH 4.5 were analyzed using the Korsmeyer–Peppas model, and the calculated n value was found to lie within the range of 0.43 to 0.85. This range is characteristic of anomalous (non-Fickian) transport, indicating that the release of the Dox from the MNCDs+Lipo@PPE nanocarrier does not follow simple diffusion kinetics. Instead, the release behavior is influenced by a combination of diffusion and matrix relaxation or erosion processes. These findings suggest that the structural features of the formulation contribute to a complex release mechanism, deviating from classical Fickian diffusion.

3.9. Anticancer Activity

Lung carcinoma cell line A549 was used to assess the in vitro anticancer activity by MTT and Live/Dead cell assay. In MTT assay Figure 9A, it is visible that MNCDs+Lipo@PPE+Dox at 2.7 mM concentration had dead cells of 90% when compared to the other two formulations, 86% in MNCDs+Lipo+Dox, and 56% in Lipo+Dox. Figure 9C–H shows the live and dead cell images of the formulations along with the control Figure 9B. In the control image, Figure 9B, all the cells are alive, whereas in the treatment group of MNCDs+Lipo@PPE+Dox showed almost 81% cell killing was observed, higher than that of MNCDs+Lipo+Dox 68.1% and Lipo+Dox 47%, exhibiting the potential anticancer activity of formulated MNCDs+Lipo@PPE+Dox. The formulation MNCDs+Lipo@PPE+Dox had higher cell killing activity compared to MNCDs+Lipo+Dox due to the presence of various phytochemicals in PPE. These results clearly indicate that MNCDs+Lipo@PPE+Dox holds strong potential as an effective nanocarrier system for anticancer therapy.

Figure 9.

(A) Percentage of A549 cells viable after treating with Lipo+Dox, MNCDs+Lipo+Dox, and MNCDs+Lipo@PPE+Dox. (B) Control, (C,D) Low and High dose of Lipo+Dox, (E,F) Low and High dose of MNCDs+Lipo+Dox, (G,H) Low and High dose of MNCDs+Lipo@PPE+Dox.

4. Conclusions

This study successfully developed a multifunctional, biocompatible magneto-liposome system (MNCDs+Lipo@PPE) incorporating magnetic carbon dots and antioxidant-rich PPE for enhanced optical and MR imaging. The synthesized MNCDs exhibited desirable magnetic and fluorescent properties, which were further stabilized and enhanced by liposomal encapsulation and surface passivation with PPE. Structural characterization confirmed the successful integration of all components, while optical studies demonstrated improved fluorescence emission. The formulation exhibited excellent colloidal stability over 30 days, especially under refrigerated conditions, with significant improvements in particle size uniformity and surface charge. In vitro assays revealed high biocompatibility, with over 93% cell viability in A549 cells, confirming its safety profile. Both optical and MR phantom imaging validated the system’s dual-modal imaging capability, showing concentration-dependent enhancements in T1- and T2-weighted MR signals. These findings highlight MNCDs+Lipo@PPE as a promising, eco-friendly, and cost-effective platform for non-invasive diagnostic imaging, along with dox loading, which showed anticancer effect against A459, exhibiting its potential for future applications in theragnostic and biomedical imaging. In conclusion, the assembled magnetoliposomes present several advantages, including improved colloidal stability, enhanced biocompatibility, and effective protection and stabilization of magnetic-fluorescent components. Additionally, they enable multimodal imaging capabilities (optical and T1- & T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging). Their magnetic responsiveness and efficient drug-loading capacity further highlight their potential as a versatile theragnostic platform for targeted imaging and cancer therapy.

Author Contributions

V.K.: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, and Writing—original draft. A.T.: Methodology, Investigation, Data curation. P.D.: Methodology, Investigation, Data curation. N.A. and A.D.P.: Investigation, Data curation, Validation. K.G.: Validation, Formal analysis, Visualization. A.G.: Conceptualization, Writing—review and editing, Supervision, Data curation and validation, Formal analysis, Project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies.

Data Availability Statement

All the data provided in the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to CARE for infrastructural support. V.K., A.T., and P.D. acknowledge CARE for research fellowships.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Huang, Y.; Yan, L.; Xu, S.; Zhang, G.; Pei, L.; Yu, H.; Zhu, X.; Han, X. Current role of magnetic resonance imaging on assessing and monitoring the efficacy of phototherapy. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2024, 110, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwivedi, D.K.; Jagannathan, N.R. Emerging MR methods for improved diagnosis of prostate cancer by multiparametric MRI. Magn. Reson. Mater. Phys. Biol. Med. 2022, 35, 587–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, R.; Sinha, N.; Jagannathan, N.R. Potential of in vitro nuclear magnetic resonance of biofluids and tissues in clinical research. NMR Biomed. 2023, 36, e4686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haribabu, V.; Girigoswami, K.; Sharmiladevi, P.; Girigoswami, A. Water–Nanomaterial Interaction to Escalate Twin-Mode Magnetic Resonance Imaging. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 6, 4377–4389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, H.; Zhang, Y.N.; Yan, M.; Xia, J.; Wang, M.; Tian, G.; Lv, H.; Liu, K.; Zhang, G. Aggregation-induced magnetic coupling nanoassemblies that effectively switched from T2 to T1 contrast imaging for highly specific MRI detection of micron sized hepatocellular carcinoma. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 506, 159882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowtham, P.; Haribabu, V.; Prabhu, A.D.; Pallavi, P.; Girigoswami, K.; Girigoswami, A. Impact of nanovectors in multimodal medical imaging. Nanomed. J. 2022, 9, 107–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kailasa, S.K.; Koduru, J.R. Perspectives of magnetic nature carbon dots in analytical chemistry: From separation to detection and bioimaging. Trends Environ. Anal. Chem. 2022, 33, e00153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Wang, H.; Yang, W.; Bai, Y.; Wu, Z.; Cui, T.; Bian, K.; Yi, J.; Shao, C.; Zhang, B. One-Dose Bioorthogonal Gadolinium Nanoprobes for Prolonged Radiosensitization of Tumor. Small 2025, 21, 2500504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coimbra, S.; Rocha, S.; Viana, S.D.; Rebelo, R.; Rocha-Pereira, P.; Lousa, I.; Valente, M.J.; Catarino, C.; Belo, L.; Bronze-da-Rocha, E.; et al. Gadoteric Acid and Gadolinium: Exploring Short- and Long-Term Effects on Healthy Animals. J. Xenobiot. 2025, 15, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhoopathy, J.; Vedakumari, S.W.; Pravin, Y.R.; Prabhu, A.D. Radiopaque Silk Sericin Nanoparticles for Computed Tomography Imaging of Solid Tumors. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2025, 8, 5007–5014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarciglia, A.; Papi, C.; Romiti, C.; Leone, A.; Di Gregorio, E.; Ferrauto, G. Gadolinium-Based Contrast Agents (GBCAs) for MRI: A Benefit–Risk Balance Analysis from a Chemical, Biomedical, and Environmental Point of View. Glob. Chall. 2025, 9, 2400269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, P.; Prabhu, A. Smart SPIONs for Multimodal Cancer Theranostics: A Review. Mol. Pharm. 2025, 22, 2372–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafabakhsh, R.; Zhang, R.; Thoröe-Boveleth, S.; Moosavifar, M.; Abergel, R.J.; Kiessling, F.; Lammers, T.; Pallares, R.M. Gold Nanoparticle-Enabled Fluorescence Sensing of Gadolinium-Based Contrast Agents in Urine. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2025, 8, 2013–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallik, R.; Saha, M.; Ghosh, B.; Chauhan, N.; Mohan, H.; Kumaran, S.S.; Mukherjee, C. Folate Receptor Targeting Mn(II) Complex Encapsulated Porous Silica Nanoparticle as an MRI Contrast Agent for Early-State Detection of Cancer. Small 2025, 21, 2401787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiran, V.; Harini, K.; Thirumalai, A.; Girigoswami, K.; Girigoswami, A. Nanostructured Carbon Dots as Ratiometric Fluorescent Rulers for Heavy Metal Detection. Int. J. Nano Dimens. 2024, 15, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Chen, L.; Guo, R.; Yang, Y.; Liu, X.; Yu, S. Gadolinium Functionalized Carbon Dot Complexes for Dual-Modal Imaging: Structure, Performance, and Applications. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2025, 11, 2037–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajipour Keyvani, A.; Mohammadnejad, P.; Pazoki-Toroudi, H.; Perez Gilabert, I.; Chu, T.; Manshian, B.B.; Soenen, S.J.; Sohrabi, B. Advancements in Cancer Treatment: Harnessing the Synergistic Potential of Graphene-Based Nanomaterials in Combination Therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 2756–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.; Yi, X.; Xiang, D.; Zhou, L. Nanoagent-Mediated Photothermal Therapy: From Delivery System Design to Synergistic Theranostic Applications. Int. J. Nanomed. 2025, 20, 6891–6927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, R.; Yang, B. Carbon dots: A new type of carbon-based nanomaterial with wide applications. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020, 6, 2179–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Kang, M.; Ji, S.; Ye, S.; Guo, J. Research on Red/Near-Infrared Fluorescent Carbon Dots Based on Different Carbon Sources and Solvents: Fluorescence Mechanism and Biological Applications. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, V.; Verma, R.; Gopalkrishnan, C.; Yuan, M.-H.; Batoo, K.M.; Jayavel, R.; Chauhan, A.; Lin, K.-Y.A.; Balasubramani, R.; Ghotekar, S. Bio-inspired synthesis of carbon-based nanomaterials and their potential environmental applications: A state-of-the-art review. Inorganics 2022, 10, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raveendran, R.; Prabakaran, L.; Senthil, R.; Yesudhason, B.V.; Dharmalingam, S.; Sathyaraj, W.V.; Atchudan, R. Current Innovations in Intraocular Pressure Monitoring Biosensors for Diagnosis and Treatment of Glaucoma—Novel Strategies and Future Perspectives. Biosensors 2023, 13, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hojjati, S.M.; Salehi, Z.; Akrami, M. MRI-traceable multifunctional magnetic mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MMSN) capped with graphene quantum dots (GQD) as a theragnostic system in colorectal cancer treatment. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2024, 96, 105700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanidenko, E.A.; Vedernikova, A.A.; Badrieva, Z.F.; Brui, E.A.; Ondar, S.O.; Miruschenko, M.D.; Volina, O.V.; Koroleva, A.V.; Zhizhin, E.V.; Ushakova, E.V. Manganese-Doped Carbon Dots as a Promising Nanoprobe for Luminescent and Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Photonics 2023, 10, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Qing, X.; Liu, S.; Yang, D.; Dong, X.; Zhang, Y. Hollow Mesoporous Manganese Oxides: Application in Cancer Diagnosis and Therapy. Small 2022, 18, 2106511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, C.; Ma, Q.; Gong, L.; Di, S.; Gong, J.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Fu, J.-J.; et al. Manganese-based multifunctional nanoplatform for dual-modal imaging and synergistic therapy of breast cancer. Acta Biomater. 2022, 141, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Jin, X.; Yan, L.; Yang, Y.; Liu, X. Recent research progress in CDs@ MOFs composites: Fabrication, property modulation, and application. Microchim. Acta 2023, 190, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.; Shi, B.; Zhu, W.; Lü, C. Temperature-responsive polymer-tethered Zr-porphyrin MOFs encapsulated carbon dot nanohybrids with boosted visible-light photodegradation for organic contaminants in water. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 426, 131794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Li, S.; Chen, B.; Wang, Y.; Shen, Z.; Qiu, M.; Pan, H.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, X. Endoplasmic reticulum-targeted polymer dots encapsulated with ultrasonic synthesized near-infrared carbon nanodots and their application for in vivo monitoring of Cu2+. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 627, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Fei, J.; Dong, Z.; Yu, F.; Li, J. Nanoarchitectonics with a Membrane-Embedded Electron Shuttle Mimics the Bioenergy Anabolism of Mitochondria. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202319116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Fei, J.; Zhao, J.; Li, H.; Cui, Y.; Li, J. Hypocrellin-Loaded Gold Nanocages with High Two-Photon Efficiency for Photothermal/Photodynamic Cancer Therapy in Vitro. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 8030–8040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Fei, J.; Wang, A.; Yang, Y.; Li, J. Rational assembly of a biointerfaced core@shell nanocomplex towards selective and highly efficient synergistic photothermal/photodynamic therapy. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 20197–20210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Martín, F.; D’Amelio, N. Biomembrane lipids: When physics and chemistry join to shape biological activity. Biochimie 2022, 203, 118–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, M.W.S.; Tero, R. Cholesterol-induced microdomain formation in lipid bilayer membranes consisting of completely miscible lipids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2021, 1863, 183626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Aranguren, L.; Anas, A.T.M.; Muhammad, U.; Parag, J.; Marwah, M.K. Mitochondrial-targeted liposome-based drug delivery—Therapeutic potential and challenges. J. Drug Target. 2025, 33, 575–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegafaw, T.; Mulugeta, E.; Zhao, D.; Liu, Y.; Chen, X.; Baek, A.; Kim, J.; Chang, Y.; Lee, G.H. Surface Modification, Toxicity, and Applications of Carbon Dots to Cancer Theranosis: A Review. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Chen, S.; Liao, Y.; Li, S.; Ge, J.; Tao, F.; Huo, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Z. Near-infrared fluorescent carbon dots encapsulated liposomes as multifunctional nano-carrier and tracer of the anticancer agent cinobufagin in vivo and in vitro. Colloids Surf. B. Biointerfaces 2019, 174, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, B.; Moulahoum, H.; Ghorbanizamani, F.; Barlas, F.B.; Yesiltepe, O.; Gumus, Z.P.; Meral, K.; Odaci Demirkol, D.; Timur, S. Carbon dots and curcumin-loaded CD44-Targeted liposomes for imaging and tracking cancer chemotherapy: A multi-purpose tool for theranostics. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2021, 62, 102363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vescovo, D.; Manetti, C.; Ruggieri, R.; Spizzirri, U.G.; Aiello, F.; Martuscelli, M.; Restuccia, D. The Valorization of Potato Peels as a Functional Ingredient in the Food Industry: A Comprehensive Review. Foods 2025, 14, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Champi, D.; Romero-Orejon, F.L.; Moran-Reyes, A.; Muñoz, A.M.; Ramos-Escudero, F. Bioactive compounds in potato peels, extraction methods, and their applications in the food industry: A review. CyTA—J. Food 2023, 21, 418–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.P.; Saldaña, M.D.A. Subcritical water extraction of phenolic compounds from potato peel. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 2452–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Martínez, B.; Gullón, B.; Yáñez, R. Identification and Recovery of Valuable Bioactive Compounds from Potato Peels: A Comprehensive Review. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayat, W.; Irna, S.; Hemiawati, S.M.; Ronny, L.; Ichwan, S. Pharmacological Activity of Chemical Compounds of Potato Peel Waste (Solanum tuberosum L.) in vitro: A Scoping Review. J. Exp. Pharmacol. 2024, 16, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himanshu, M.; Singh, A.; Srivastava, N.; Verma, B. Comparative photocatalytic performance of iron nanoparticles biosynthesized from aqueous extracts of potato, potato peels, and leaves. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 292, 139156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirumalai, A.; Girigoswami, K.; Prabhu, A.D.; Durgadevi, P.; Kiran, V.; Girigoswami, A. 8-Anilino-1-naphthalenesulfonate-Conjugated Carbon-Coated Ferrite Nanodots for Fluoromagnetic Imaging, Smart Drug Delivery, and Biomolecular Sensing. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1378. [Google Scholar]

- Janani, G.; Girigoswami, A.; Deepika, B.; Udayakumar, S.; Girigoswami, K. Unveiling the Role of Nano-Formulated Red Algae Extract in Cancer Management. Molecules 2024, 29, 2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessy Mercy, D.; Kiran, V.; Thirumalai, A.; Harini, K.; Girigoswami, K.; Girigoswami, A. Rice husk assisted carbon quantum dots synthesis for amoxicillin sensing. Results Chem. 2023, 6, 101219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Long, S.; Feng, R.; Yu, M.-J.; Xu, B.-C.; Tao, H. Thiolated dextrin nanoparticles for curcumin delivery: Stability, in vitro release, and binding mechanism. Food Chem. 2025, 463, 141501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepika, B.; Gowtham, P.; Raghavan, V.; Isaac, J.B.; Devi, S.; Kiran, V.; Mercy, D.J.; Sofini, P.S.; Harini, A.; Girigoswami, A. Harmony in nature’s elixir: A comprehensive exploration of ethanol and nano-formulated extracts from Passiflora incarnata leaves: Unveiling in vitro cytotoxicity, acute and sub-acute toxicity profiles in Swiss albino mice. J. Mol. Histol. 2024, 55, 977–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harini, K.; Alomar, S.Y.; Vajagathali, M.; Manoharadas, S.; Thirumalai, A.; Girigoswami, K.; Girigoswami, A. Niosomal Bupropion: Exploring Therapeutic Frontiers through Behavioral Profiling. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, D.; Rajamanikandan, R.; Ilanchelian, M. Investigating the Function of Ribonucleic Acid in Suppressing the Spectral and In Vitro Cytotoxic Effects of Methylene Blue/Thionine Dyes. Luminescence 2025, 40, e70221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandekar, A.S.; Gaikar, P.S.; Angre, A.P.; Chaughule, A.M.; Pradhan, N.S. Effect of annealing on microstructure and magnetic properties of Mn ferrite powder. J. Biol. Chem. Chron. 2019, 5, 74–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, T.-W.; Yang, C.-H.; Su, C.-J.; Huang, Y.-T.; Yeh, Y.-Q.; Liao, K.-F.; Lin, T.-C.; Shih, O.; Lee, M.-T.; Su, A.-C. Revealing cholesterol effects on PEGylated HSPC liposomes using AF4–MALS and simultaneous small-and wide-angle X-ray scattering. Appl. Crystallogr. 2023, 56, 988–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowtham, P.; Girigoswami, K.; Pallavi, P.; Harini, K.; Gurubharath, I.; Girigoswami, A. Alginate-Derivative Encapsulated Carbon Coated Manganese-Ferrite Nanodots for Multimodal Medical Imaging. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Ge, J.; Gao, Y.; Chen, L.; Cui, J.; Zeng, J.; Gao, M. Ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: A next generation contrast agent for magnetic resonance imaging. WIREs Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol 2022, 14, e1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momper, R.; Steinbrecher, J.; Dorn, M.; Rörich, I.; Bretschneider, S.; Tonigold, M.; Ramanan, C.; Ritz, S.; Mailänder, V.; Landfester, K.; et al. Enhanced photoluminescence properties of a carbon dot system through surface interaction with polymeric nanoparticles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 518, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.-P.; Zhou, B.; Lin, Y.; Wang, W.; Fernando, K.S.; Pathak, P.; Meziani, M.J.; Harruff, B.A.; Wang, X.; Wang, H. Quantum-sized carbon dots for bright and colorful photoluminescence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 7756–7757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiganesh, T.; Daisy Vimala Rani, J.; Girigoswami, A. Spectroscopically characterized cadmium sulfide quantum dots lengthening the lag phase of Escherichia coli growth. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2012, 92, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, H.; Pérez-Andrés, E.; Thevenot, J.; Sandre, O.; Berra, E.; Lecommandoux, S. Magnetic field triggered drug release from polymersomes for cancer therapeutics. J. Control. Release 2013, 169, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.