Abstract

This study investigates how Vision Language Models (VLMs) can be used and methodically configured to extract Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) metrics from corporate sustainability reports, addressing the limitations of existing text-only and manual ESG data-extraction approaches. Using the Design Science Research Methodology, we developed an extraction artifact comprising a curated page-level dataset containing greenhouse gas (GHG) emission-reduction targets, an automated evaluation pipeline, model and text-preprocessing comparisons, and iterative prompt and few-shot refinement. Pages from oil and gas sustainability reports were processed directly by VLMs to preserve visual–textual structure, enabling a controlled comparison of text, image, and combined input modalities, with extraction quality assessed at page and attribute level using F1-scores. Among tested models, Mistral Small 3.2 demonstrated the most stable performance and was used to evaluate image, text, and combined modalities. Combined text + image modality performed best (F1 = 0.82), particularly on complex page layouts. The findings demonstrate how to effectively integrate visual and textual cues for ESG metric extraction with VLMs, though challenges remain for visually dense layouts and avoiding inference-based hallucinations.

1. Introduction

Global interest in information about the sustainability of companies and in sustainability reporting to fulfill the information demand has grown in recent years. Sustainability reports are therefore a considerable data source for individuals and institutions. Investors in sustainable finance increasingly use ESG as selection criteria [1], regulators need to determine the compliance of companies with legislation [2] and researchers rely on sustainability data for empirical analysis [3]. However, no publicly available ESG disclosure database exists [4].

The volume and complexity of the disclosure make human analysis time-consuming and costly. Only a few entities worldwide have the resources to do so at scale. Secondary ESG data from these providers is characterized as being limited, unstandardized, and locked behind proprietary assessment methodologies [5]. The underlying ESG metrics are primarily based on manual data extraction. MSCI, for example, reports that only 20% of the metrics for its ESG ratings are extracted using AI-based methods [6]. In academic research, methods for the automatic extraction of ESG metrics have long been under investigation [4,7]. The ability to extract GHG emission-reduction targets and similar quantitative ESG metrics in a structured, machine-readable format has substantial practical and scientific significance [8]. Structured data enhances transparency and comparability of corporate disclosures and enables stakeholders to reliably evaluate firms or detect greenwashing [9]. It also reduces the reliance on proprietary data providers and facilitates scalable quantitative analyses and reproducible academic research [10]. Traceable extraction of ESG metrics is essential for auditability, as stakeholders must be able to verify reported values against their original disclosure context [11].

Recent approaches increasingly rely on the use of Large Language Models (LLMs) [12]. However, quantitative metrics are mostly reported using tables and graphics [12]. This presents a significant challenge: sustainability reports are often disseminated in PDF format and feature heterogeneous document layouts [13]. Standard optical character recognition (OCR)- or PDF-to-text-based pipelines tend to strip away structural cues such as table boundaries or spatial grouping [14], often resulting in misalignment or loss of critical numeric data (e.g., GHG targets) [15]. This is why recent studies have begun to explore, in addition to LLMs that are limited to text-based inputs, the use of Vision Language Models (VLMs), which are capable of processing both text and images [16].

The growing availability of VLMs, driven by releases such as GPT-4o, open-source alternatives like Mistral 3, or Google’s Gemma, is opening new avenues for research. For instance, Peng et al. [17] demonstrated the applicability of VLMs for structuring unstructured ESG reports. In their study, the authors identified text, images, and tables as the main components of ESG reports and employed VLMs to extract information from visual elements and integrate it into the structuring process. This development highlights the potential of VLMs for extracting ESG metrics from sustainability reports.

Many questions remain open in the current literature. On the one hand, it is still unclear how effectively VLMs can handle the complexity of sustainability reports compared to purely text-based approaches, particularly given the diverse modes of information representation within sustainability reports. On the other hand, it remains largely unexplored how VLMs must be configured and adapted to reliably extract quantitative ESG metrics from visually complex sustainability reports. From this research gap arises the following research question:

RQ:

How can Vision Language Models be used and adapted in the process of extracting ESG metrics from sustainability reports?

By answering this research question, we investigate how different input modalities and prompt-based adaptations can increase the extraction performance of Vision Language Models in document-level ESG information extraction (IE).

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews related work on metric extraction from sustainability reports using language models. Section 3 details the proposed methodology, describing the activities based on the Design Science Research Methodology (DSRM). Section 4 presents the development process in detail and the respective results. Finally, Section 5 discusses the results, and Section 6 summarizes the conclusions and outlines potential directions for future work.

2. Related Research

Prior research has increasingly treated corporate sustainability reports as a valuable data source for automated analysis, reflecting their growing availability and richness [2]. Early natural language processing approaches relied primarily on topic modeling, text classification, and other bag-of-words techniques to generate sustainability scores or derive basic thematic insights from disclosures [18,19].

Studies on climate-related disclosures, including work by Wrzalik et al. [20], Schimanski et al. [21] and Dave et al. [22], touch on the extraction of net-zero-related metrics but do not define these targets in sufficient depth due to the limited abilities of the used language models.

More recent work has shifted toward the use of large language models and Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG). Studies such as Zou et al. [4] or Bronzini et al. [15] have applied RAG-based pipelines to question-answering tasks over sustainability reports, demonstrating improved flexibility compared with earlier NLP systems. However, these approaches remain predominantly text-only. The conversion of PDF sustainability reports to text differs, ranging from OCR pipelines [19] to the use of PDF libraries such as PyMuPDF [15]. These approaches struggle with non-linear layouts, graphical elements, embedded tables, sidebars, and figures [23]. These are elements that are common in sustainability reporting and essential for contextualizing more complex ESG metrics. PDF conversion methods affect the quality of the extracted content, particularly in the presence of visually encoded information. A different approach lies in using specialized VLMs such as tool LayoutLMv3 [24] as a preprocessing step to capture text and table structures from sustainability reports [4]. These authors acknowledge that their approach does not successfully identify information embedded in pictorial or infographic forms.

Beyond the sustainability domain, recent work demonstrates that VLMs can be applied end-to-end for information extraction tasks, e.g., for medical invoices [25] or research articles [26]. While these studies highlight the general feasibility of VLM-based extraction, they do not address the distinctive structural and semantic characteristics of sustainability reports.

Two other research articles incorporate visual information in the extraction pipeline for sustainability reports. Firstly, GPT-4-Vision-Preview was used to produce textual interpretations of image contents, showing that modern models can reason over visual components of sustainability reports [17]. However, these interpretations are used to enrich textual representations, rather than serving as direct inputs to a structured extraction pipeline. Only a single study has been identified that directly employs a VLM for IE of sustainability metrics [27]. Their work identifies relevant sections using GRI index tables and applies 7B and 11B VLMs to extract sustainability disclosures. The outputs appear in heterogeneous formats and require substantial human validation. The authors also do not compare performance across text-only and multimodal input channels. This observation is consistent with recent survey evidence, which shows that VLMs were predominantly used for retrieval, parsing, and document understanding tasks [28].

Information retrieval (IR) represents an additional source of variation in the literature. Across ESG-related extraction tasks and long-document LLM applications more broadly, studies adopt a wide spectrum of retrieval strategies. Some rely on keyword-based filtering using keywords or section headings, while others implement vector-based retrieval [15] or combine different approaches [20]. These retrieval stages are typically introduced to reduce computational cost and restrict the LLM’s context to passages deemed relevant [29]. However, they risk discarding pages that contain critical metrics, especially when those metrics appear in unconventional formats or visual elements that retrieval systems do not index effectively [29].

In summary, prior work on automated sustainability report analysis has largely evolved from traditional text-based NLP methods toward LLM- and RAG-based pipelines, while continuing to rely on PDF-to-text conversion. These text-centric approaches insufficiently capture tables, figures, layout, and other visually encoded information that is central to sustainability reporting. Although recent studies experiment with layout-aware models or VLMs, visual information is rarely integrated into a structured extraction pipeline, and systematic evaluations of multimodal ESG metric extraction remain scarce. Consequently, the literature provides limited evidence on the value of using large VLMs, on the integration of visual and textual modalities, and on domain-specific adaptation strategies for ESG information extraction.

3. Materials and Methods

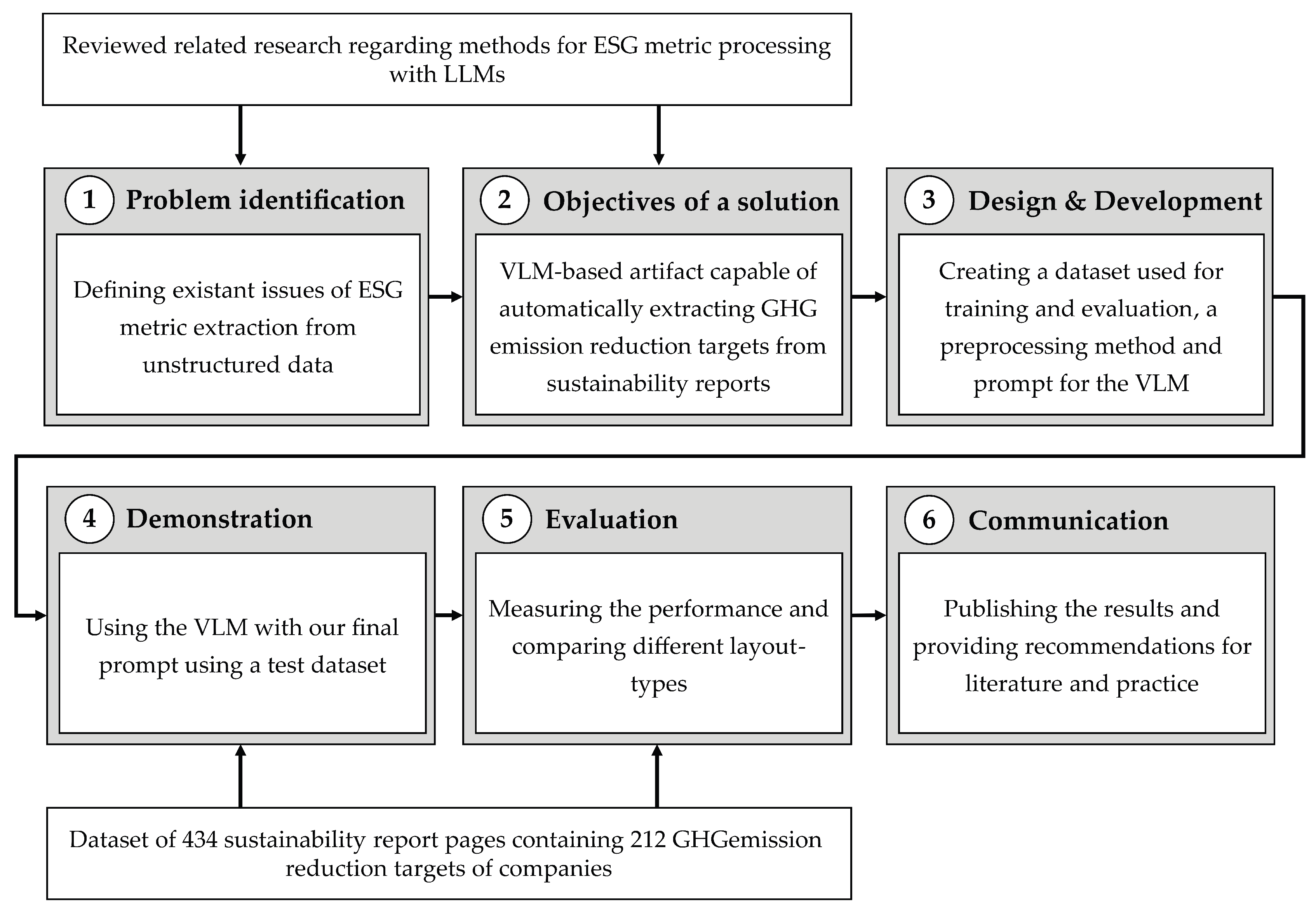

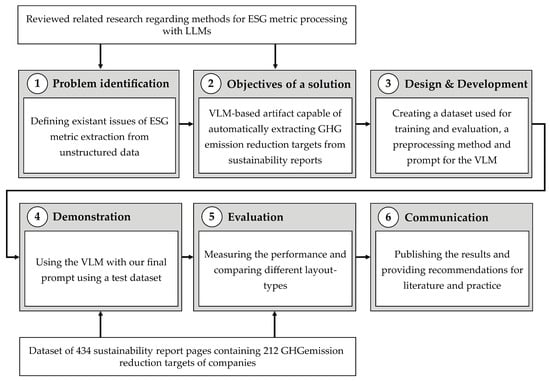

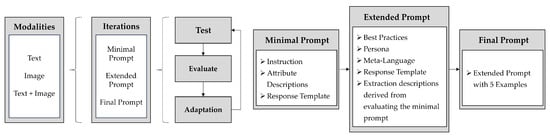

This section outlines the methodology of our study that was used to develop a VLM-based artifact to enhance information extraction and answer the research question. The research design follows the DSRM, which provides a structured and reproducible methodology to guide artifact development [30]. In this study, the artifact is not only the extraction pipeline but also the configurable process used to set and refine its components. It comprises the structured combination of inputs, model settings, and adaptation steps that jointly determine extraction performance. The six-part DSRM was used to formalize intermediate results, document design decisions, and ensure methodological rigor throughout the iterative process. Figure 1 illustrates the methodological workflow.

Figure 1.

Activities of the artifact development following the DSRM.

Prior research predominantly focused on text-only approaches, which rely on PDF-to-text conversion pipelines and LLMs to extract ESG metrics from documents.

Analyzing the related research further revealed a research gap regarding the use of VLMs for ESG metric extraction. Specifically, there is limited evidence on (1) the effective integration of visual and textual modalities, (2) the application of large VLMs to sustainability reporting, and (3) systematic methods for adapting or prompting such models for domain-specific IE tasks. Addressing these gaps motivated the development of a VLM-based extraction artifact.

Based on the identified problem, the objectives of the solution were defined to guide subsequent design decisions. We selected GHG emission-reduction targets for two reasons. First, they are commonly reported by companies in sustainability reports, and secondly, the metric is more difficult to extract due to its composition of base and target years, different units, and differentiations of scope 1, 2, and 3, which are often found in various tables and graphic forms. The artifact is intended to extract all existing attributes within a company report automatically. The information must be represented in a machine-readable JSON format consistent with the provided attribute schema. Moreover, we set the objective not only to surpass a text-only baseline, but also to achieve an F1-score of at least 80% across all required attributes.

Within this methodological framework, we used a simplified IR strategy. Instead of relying on keyword heuristics, vector-based retrieval, or multi-stage filtering, each page of a sustainability report was processed individually by the VLM. This decision reduces dependencies on retrieval-specific hyperparameters and mitigates the risk of omitting relevant passages. Moreover, page-level processing aligns with the operational characteristics of VLMs in contrast to differently sized chunks. This way, the VLM can jointly interpret rendered page images and OCR text while retaining spatial relationships among tables, figures, and layout elements.

The development process consisted of five steps, starting with the creation of a domain-specific dataset. For this purpose, a dataset of GHG emission-reduction targets in the oil and gas sector was used, as it provides real sustainability-report pages referenced in the corresponding manual MSCI annotations. However, these source references required extensive curation. The initial dataset contained 230 ESG metrics obtained from 149 sustainability reports. After adjustments and adding irrelevant pages, it was subsequently split into training, validation, and test subsets.

In the second step of the design and development, the evaluation procedure was formally defined and implemented to gain the ability to calculate the evaluation metrics without human transformation steps. Predictions generated by the VLM were matched to ground-truth records, ensuring a correct comparison even when multiple targets appear on different pages or when models produce different orderings. Attribute-wise F1-scores are computed and aggregated across the dataset.

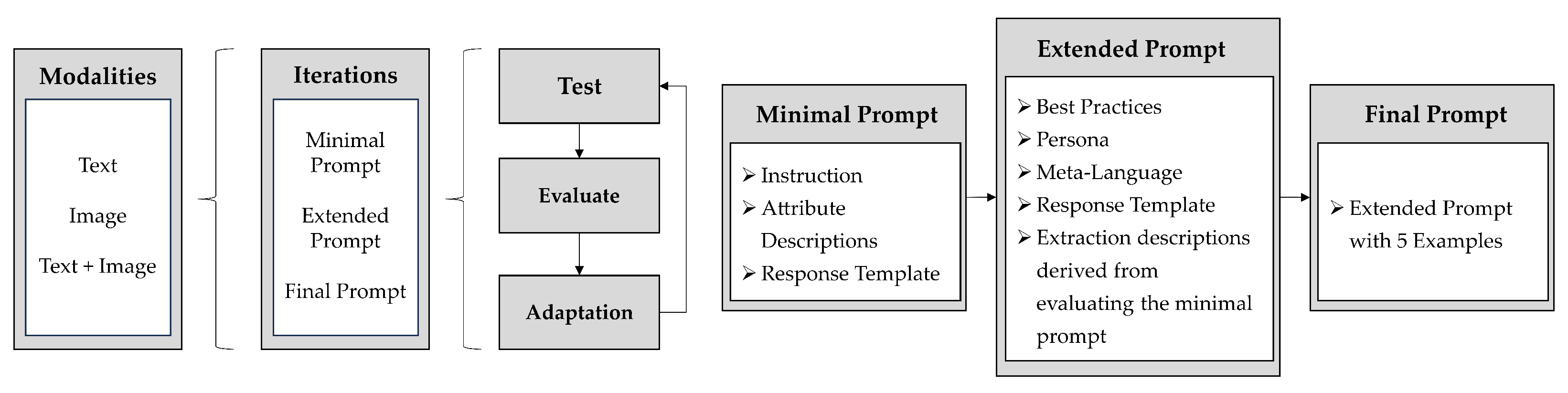

In the third step, we selected four VLMs with a sufficiently large context window so that multiple few-shot examples can also be used. These four models are compared using a minimal prompt and images as input. The fourth step consisted of evaluating which text preparation method allows the selected model to best extract the metrics solely based on text input as a benchmark. To this end, commonly used text preparation methods from Python (v3.12.3) libraries are being compared. In the fifth step, we conducted iterative prompt engineering to refine the prompt until the extraction accuracy stabilized on the validation set. The process is shown in Figure 2. In every iteration of the fifth step, we compared three modalities: text, image, and the combination of text + image.

Figure 2.

Development process for prompt improvement.

After completing these design and development activities, the artifact was demonstrated on a previously unseen test dataset consisting of sustainability-report pages. The subsequent evaluation assessed whether the artifact met the predefined performance criteria and gave insights into the performance on simple and complex layout types. Finally, the outcomes of the study, including methodological contributions, empirical findings, and implications for both research and practice, were synthesized and are presented in the following chapter. We also published the source code used for preprocessing, inference, and calculating the evaluation metrics.

4. Results and Research Process

This chapter presents the design decisions as well as intermediate results based on the conducted experiments. It is structured following the five steps of the development phase, followed by the results of the evaluation phase.

4.1. Adjusted Dataset

The dataset comprises company-wide greenhouse gas emission-reduction targets extracted from global oil and gas companies, based on the MSCI dataset. Individual ESG reports may contain multiple emission-reduction targets, and each page of a report can include zero or many ESG metrics. Each metric is represented by a set of attributes, which are stored as columns in the dataset and include categorical, numerical, and textual fields as listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Attributes of the GHG emission-reduction target metric.

Several adjustments were required to obtain a consistent dataset: Entries for which the underlying report pages were not publicly available were removed. Pages without extractable metrics were added to ensure that the dataset accurately reflects the prevalence of irrelevant pages and to test whether the model can distinguish between relevant and irrelevant content. Extractions were reduced to a single page when earlier entries combined multiple pages or referenced several sources. Attributes that did not appear on the referenced page but had been added from external sources in the MSCI annotations were removed. Duplicate entries were deleted, and all remaining extractions were reviewed to correct mistakes or missing values caused by unclear or complex phrasing in the reports. In addition, the attribute NET_ZERO_CLAIM_TYPE was introduced. The mere mention of net zero is already an important indication of climate strategy. However, there is a risk of greenwashing here, particularly in the oil and gas industry [31]. To compare whether the VLM performs a correct extraction later, three characteristics are defined: Net Zero, Scientific Net Zero, and SBTI Net Zero.

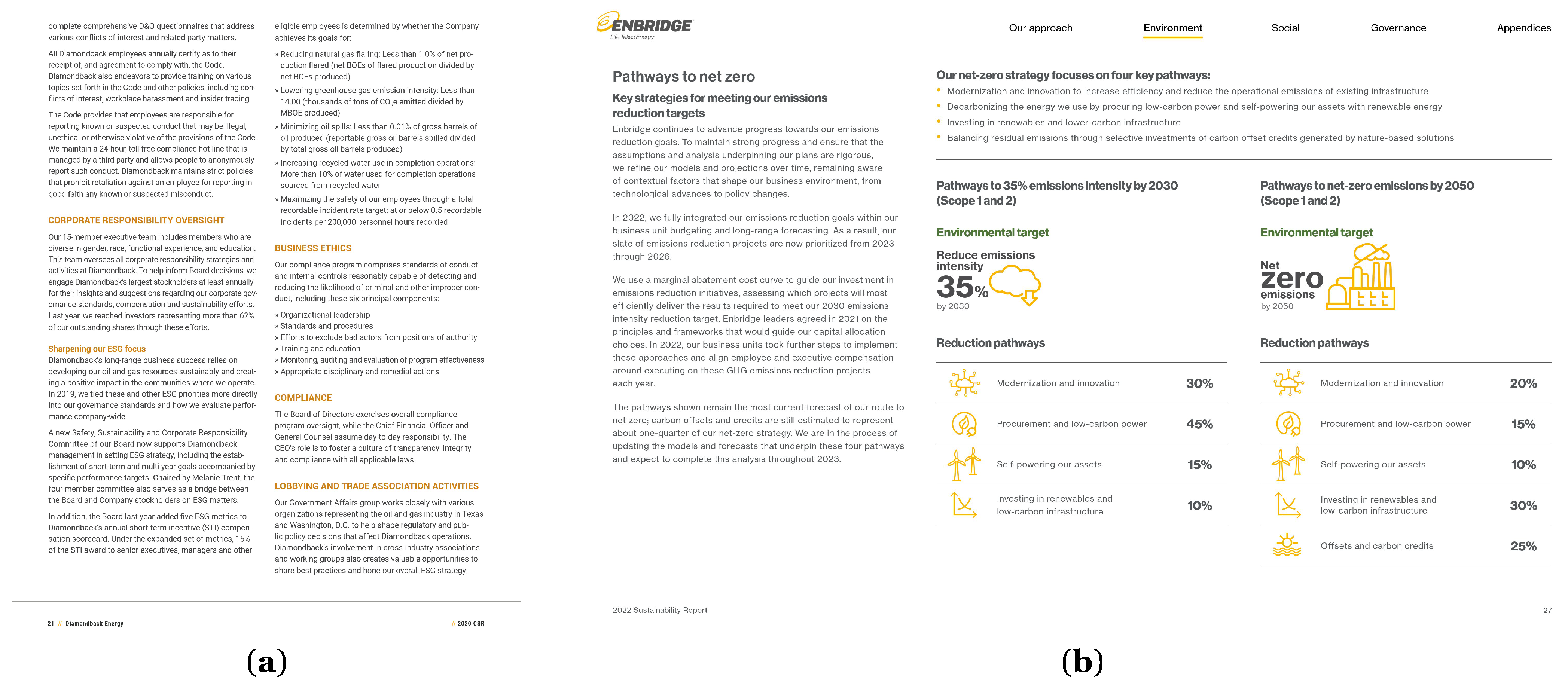

The review of the reports showed considerable variation in page layout. Some pages consist primarily of continuous text, while others contain complex structures such as tables or figures embedded in text. To assess whether layout influences extraction performance during evaluation, pages in the final dataset were classified as simple or complex when they contained at least one ESG metric [27]. Irrelevant pages without metrics were not classified. Examples of pages classified as simple and complex are displayed in Figure 3. The test dataset was stratified according to these layout types to reflect realistic conditions in which most pages do not contain relevant ESG metrics.

Figure 3.

Examples of report pages containing the targets: (a) Simple Layout from Diamondback Energy 2020, p. 22; (b) Complex Layout from Enbridge 2022, p. 27.

The dataset was divided into training, validation, and test subsets (Table 2). The training set, the smallest subset, was used to construct few-shot examples for model adaptation, reflecting the requirement of few-shot learning that only a small number of examples is needed [32]. The validation set supports iterative assessment and refinement of prompt variants during model development. The test set was used exclusively in the evaluation phase to assess the final model under conditions representative of real-world ESG report processing. Additional information on the distribution of the attributes within the metrics of the three datasets is listed in Appendix A.

Table 2.

Overview of the composition of the dataset subsets.

4.2. Automatic Evaluation Procedure

The evaluation procedure relied on precision, recall, and F1-score, following established practice for imbalanced classification tasks, while accuracy was not used. These metrics are originally defined for binary classification and had to be adapted for multi-class problems. Because many attributes contained more than two classes and exhibited substantial class imbalance, appropriate averaging methods were required. Macro (m) and weighted (w) averaging were applied. Macro averaging calculates the unweighted mean across classes and assigns equal importance to each class, which helps to reveal weaknesses in the classification of underrepresented classes that may be obscured in weighted scores. Weighted averaging accounts for class frequencies and therefore reflects overall model performance more realistically. Macro averaging may be overly pessimistic when misclassifications in dominant classes outweigh correct predictions in relevant minority classes [33]. This effect can occur when attributes allow for many potential numerical values and the model outputs values that do not exist in the dataset, e.g., for year values. For this reason, weighted scores were used as the primary metrics, complemented by macro scores to verify the results [34]. Other strategies like micro averaging, or instance-level F1-scores were explicitly excluded from the analysis, given the significant class imbalance in the dataset distribution and the need for diagnosing attribute extraction quality individually, as instance-level F1 would obscure this into a single score.

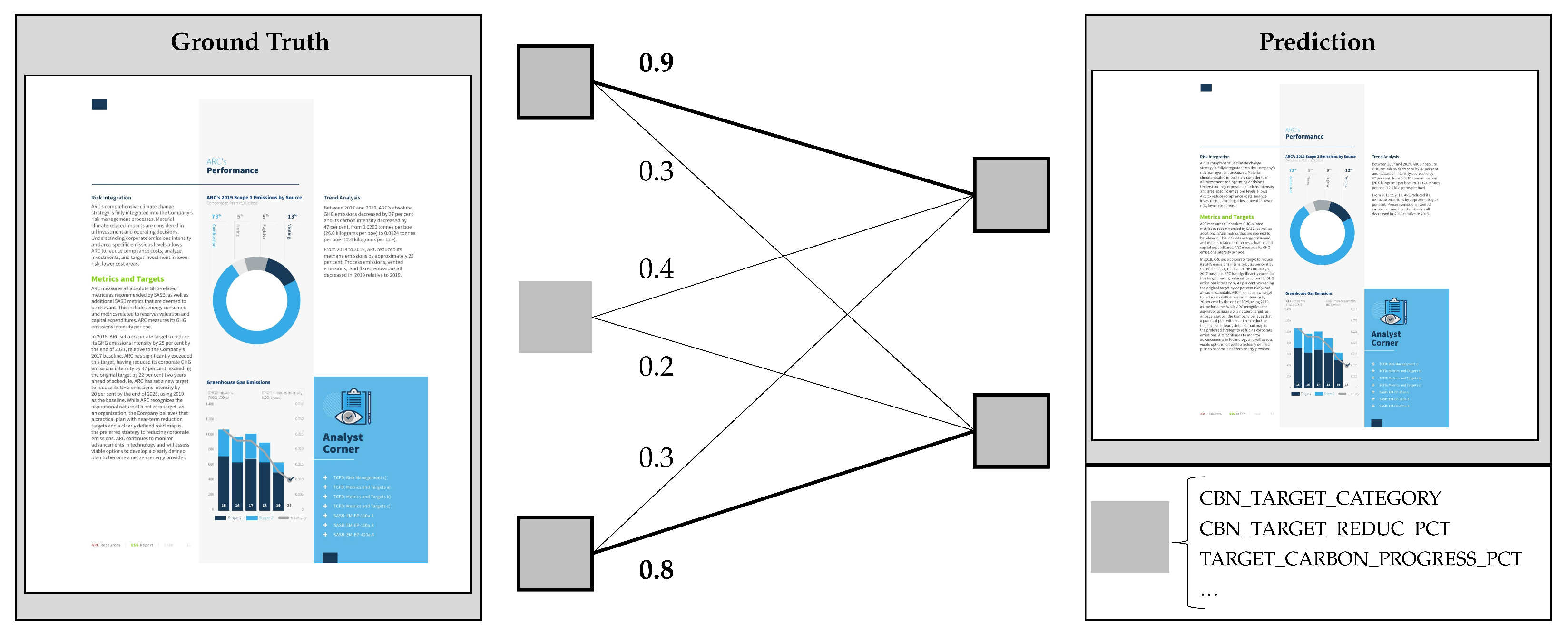

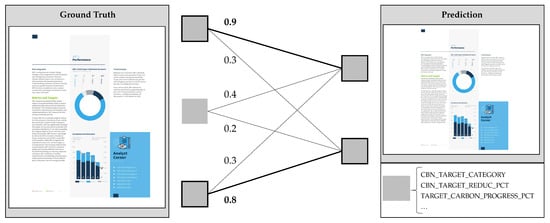

Because no established evaluation configuration exists for cases where multiple metrics may appear on a single page, a custom procedure was defined. Each extracted ESG metric on a page was matched to the corresponding ground-truth metric from the same page. The matching process consisted of two steps and is exemplified in Figure 4. First, every extracted metric was compared with every ground-truth metric on that page. This record-linkage step evaluated all classifiable attributes of a metric, counted the correctly matching attributes, and divided this value by the maximum possible number of correct attributes. The result was a set of all possible extraction-ground-truth combinations, each with an associated overlap score. Secondly, the optimal assignment was determined by maximizing total overlap. This assignment problem was solved using the Hungarian algorithm, which solved it as an equivalent minimization problem [35,36]. Alternative strategies, such as greedy matching, were considered but ultimately discarded. Greedy matching, which assigns the best immediate match iteratively, is prone to producing suboptimal global assignments [37], resulting in artificially low F1 scores when multiple similar ESG metrics (e.g., distinct targets for Scope 1 and Scope 2) differ only slightly in their attribute composition. In contrast, the Hungarian algorithm guarantees a globally optimal matching of predictions to ground truth, ensuring that the evaluation strictly assesses the model’s extraction capability.

Figure 4.

Matching of ground truth and predicted metrics.

Based on these assignments, the evaluation metrics were computed. “Missing metrics” were quantified as the proportion of ground-truth metrics with no assigned prediction. The indicator “Noise ratio” was quantified as the proportion of predicted metrics that do not correspond to any ground-truth metric:

Extraction quality, defined as the F1-score, was evaluated both at the page level and at the attribute level, allowing detailed analysis of attribute-specific performance. TARGET_CARBON_UNITS and CBN_TARGET_DESC represent special cases because no fixed expected formulation exists for these attributes, which limits the applicability of exact text-based comparison. Before calculating the evaluation metrics, the values of TARGET_CARBON_UNITS were processed. Spaces were removed, all letters are converted to uppercase, and finally, subscript characters are normalized to compensate for any differences in formatting during evaluation. CBN_TARGET_DESC is excluded from the automatic evaluation, as it represents descriptive text without a fixed expected formulation and therefore cannot be assessed using automatic comparison metrics. The generated descriptions are stored together with the other attributes.

4.3. Model Selection

For the experiments that result in the selection of the best-performing VLM, proprietary and open-source VLMs from Mistral (Mistral-Small-3.2-24B-Instruct-2506), Google (gemini-2.0-flash-001), OpenAI (gpt-4.1-mini-2025-04-14), and Meta (Llama-4-Scout-17B-16E-Instruct) were selected. The main selection criteria were availability on public cloud platforms, model recency, and context size. The validation dataset was used for this and subsequent analyses. More information on the four models is specified in Appendix B.

We used a setup with a minimal prompt only consisting of the task description, the attribute definitions, and the JSON output schema. XML tags structured the prompt and separated the sections. We used a configuration with a temperature of 0 to ensure predictions that are as repeatable as possible. PDF pages were converted to PNG images at 300 DPI, resulting in a resolution of 2481 × 3507 pixels for the DIN A4 format. The VLM providers internally rescale the images to different resolutions, which is not configurable. The results of the model comparison are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Evaluation metrics for the model selection.

The first outcome of the comparison was the conformity of the responses in terms of format. With the exception of Gemini 2.0 Flash, all models followed the specified XML-JSON structure. Gemini 2.0 Flash failed in two cases due to missing start tags or incorrect formatting. In the quantitative evaluation, Mistral Small 3.2, Llama 4 Scout, and GPT-4.1 Mini showed full format adherence. Gemini 2.0 Flash produced the lowest rate of missing metrics (5.77%) but also the highest noise ratio (47.87%), generating nearly as many incorrect as correct metrics. Mistral Small 3.2 yielded the fewest over-extractions (30.16%) and reached the highest weighted F1-score at the page level. At the attribute level, the extraction quality of Mistral Small 3.2, Gemini 2.0 Flash, and GPT-4.1 Mini was similar. However, the models differed substantially across individual attributes. For example, Gemini 2.0 Flash achieved a weighted F1-score of 38.01% for CBN_TARGET_REDUC_PCT, while GPT-4.1 Mini reached 81.10% for the same attribute.

Overall, three of the four models met the required output format, with Gemini 2.0 Flash as the only exception. Although it extracted the most correct metrics, it also generated the highest proportion of incorrect ones. Across attributes, all models exhibited varying strengths and weaknesses in the different attributes of the ESG metrics. Mistral Small 3.2 demonstrated stable performance across all evaluated criteria and was therefore selected as the model for subsequent analyses.

4.4. Text Preparation Methods

The comparison of text preparation methods focused on identifying which approach enabled the selected model to extract information most effectively from PDF files. Four methods were evaluated, combining rule-based and VLM-based procedures. Two rule-based methods were provided by the PyMuPDF (v1.26.4) library, which is regarded as one of the most reliable PDF parsers for text extraction [23]. One method generates plain text, while the other produces a markdown representation tailored to the needs of LLMs. In addition, olmOCR (v0.2.3) was applied as a fine-tuned VLM OCR model (olmOCR-7B-0725-FP8) specifically designed for PDF processing, aiming to retain structural elements such as sections, tables, and lists [38]. The fourth method used the VLM Gemini 2.0 Flash. Despite the unsuccessful test for using this model for extraction, it also demonstrates abilities for transcriptions based on PDF input according to the specifications of Google. Using the model gave us an approach capable of producing textual descriptions of images. All four text variants were processed with Mistral Small 3.2 using the minimal prompt on the validation dataset, and the resulting performance is reported in Table 4.

Table 4.

Evaluation metrics for the text preparation methods.

Based on the evaluation metrics, PyMuPDF achieved the highest extraction quality, showing the lowest rate of missing content. However, it also showed a slightly increased noise ratio. For subsequent benchmarking steps comparing the image modality to text-only extraction and setting up a combined text-image approach, the PyMuPDF plain-text conversion was selected.

4.5. Prompt Improvement

The initial baseline of the prompt improvement step relied on a minimal prompt evaluated with Mistral Small 3.2 across the three modalities: text, image and text + image. Combining image and text produced lower F1 scores and higher rates of over-extraction compared to using only text or only images. The main sources of error were linked to specific attributes and reflected a consistent pattern of inference under underspecified information. For CBN_TARGET_REDUC_PCT, the model hallucinated a reduction value of 100% whenever the claim type was classified as Net Zero. A similar issue appeared for TARGET_CARBON_SCOPE_123_CATEGORY, where Scope 1, 2, and 3 were assigned by default in the presence of a Net Zero label without supporting evidence. These behaviors indicate a systematic tendency of the model to complete missing attribute values based on learned semantic associations rather than restricting extractions to information explicitly present in the context. Over-extractions also occurred when the model included targets unrelated to company-wide goals, such as flaring or methane emissions. This points to insufficient contextual differentiation between company-level strategies and narrower operational activities. The opposite issue appeared on pages containing several metrics, where relevant metrics were missing from the output. Finally, the TARGET_CARBON_TYPE was consistently extracted as absolute, although it should depend on the unit mentioned in the source.

To address these errors, the task description and attribute specifications were revised, and a set of established prompt patterns was added [39]. The prompt was extended with an ESG-specialist persona, meta-language describing ESG metrics, and additional instructions informed by common errors and best practices from the model provider Anthropic. Table 5 shows the corresponding evaluation results of this extended prompt.

Table 5.

Evaluation metrics for the extended prompt.

Performance improved across all metrics, with reductions in both missing and over-extracted items. The noise ratio decreased for all modalities, with text achieving the lowest rate. Extraction quality at the page level increased to 99% for text. Some attributes improved substantially. For example, TARGET_CARBON_TYPE increased its weighted-average F1-score from 12.84% to 74.23% for the text-image modality. However, the model continued to infer values when a Net Zero target was detected, meaning that the hallucination of percentages and target years persisted.

As a final step, few-shot examples were integrated. The training set of five examples was used, covering distinct layout types of increasing complexity. The page contents were adapted to the respective modality by converting the same underlying examples into text, image prompts, or combined text + image, depending on the experimental setting.

The prompt parts and changes between the three versions are shown in Appendix C. Table 6 presents the evaluation metrics for this version.

Table 6.

Evaluation metrics for the final prompt.

The image and text + image modalities showed small improvements, while the text modality exhibited a slight decrease in extraction quality. These results stem from a reduction in missing metrics and an increase in correctly extracted attributes, although some attributes became less accurate. The previously observed errors related to the misinterpretation of specific target attributes were removed through the examples. Still, after the prompt engineering process, 11.54–13.46% of metrics remained unextracted, and some misinterpretations persisted. Nevertheless, the results exceeded the target threshold of 80%, and the text + image modality performed slightly better than text alone on the attribute level. The improvement in F1 scores demonstrates the potential of few-shot prompting to enhance accuracy and completeness, and the final prompt can be used for the evaluation stage.

4.6. Evaluating the Final Prompt

The final prompt was applied to the full test set and subsequently evaluated on subsets with simple and complex layouts. Because of the larger number of examples, this setup provides the most representative view of the model’s actual performance. To mitigate numerical precision effects, which can lead to instability in answers of LLMs during inference, even with a temperature of 0 [40], we perform the evaluation three times and calculate averages (Table 7 and Table 8).

Table 7.

Evaluation metrics for the final prompt on the test dataset.

Table 8.

Evaluation metrics for the final prompt using text + image on the test dataset for different layouts.

Across modalities, missing metrics for image-only and text-only inputs increased substantially, while the combined text + image modality remained the strongest with 13.52% missing metrics. Text-only inputs continued to show the lowest noise ratio, a pattern examined separately later. The text + image modality also achieved the highest F1 scores at 52.94% macro-average and 82.08% weighted-average, indicating that the overall extraction quality on the test set is lower than on the validation set. Overall, the results suggest that combining visual and textual information leads to the highest extraction performance for Mistral Small 3.2, particularly in more challenging layout conditions.

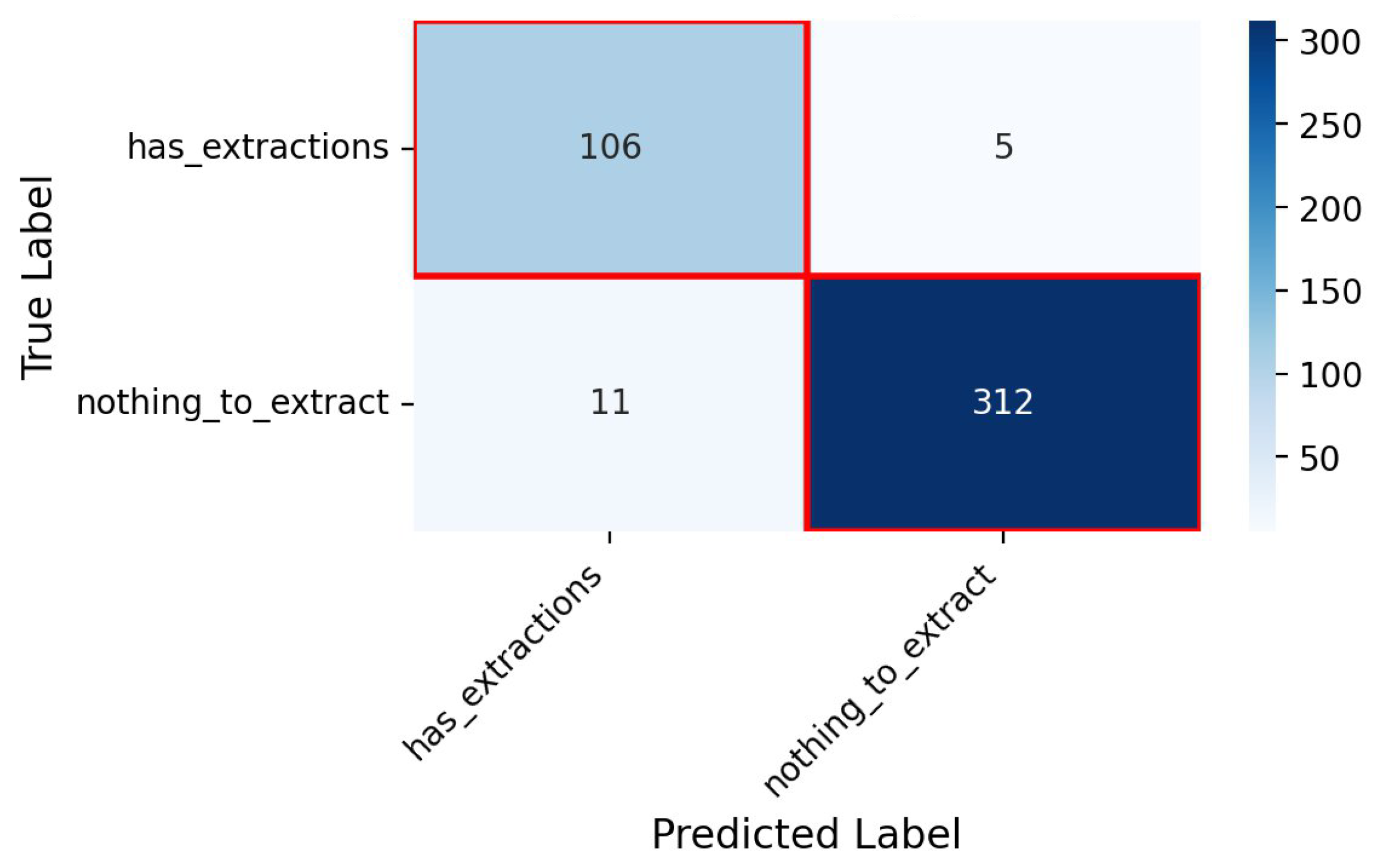

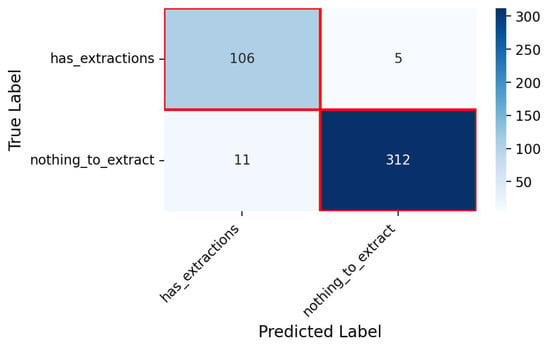

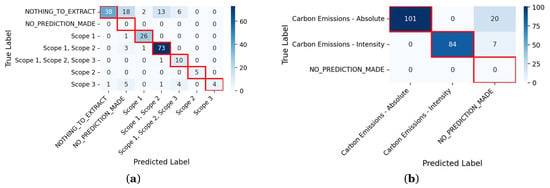

The page-level confusion matrix shows that five ESG-relevant pages were not identified (see Figure 5). Therefore, the model does not capture all relevant content, although most pages are detected. This is relevant for any practical deployment of the system.

Figure 5.

Confusion matrix of the page-level classification.

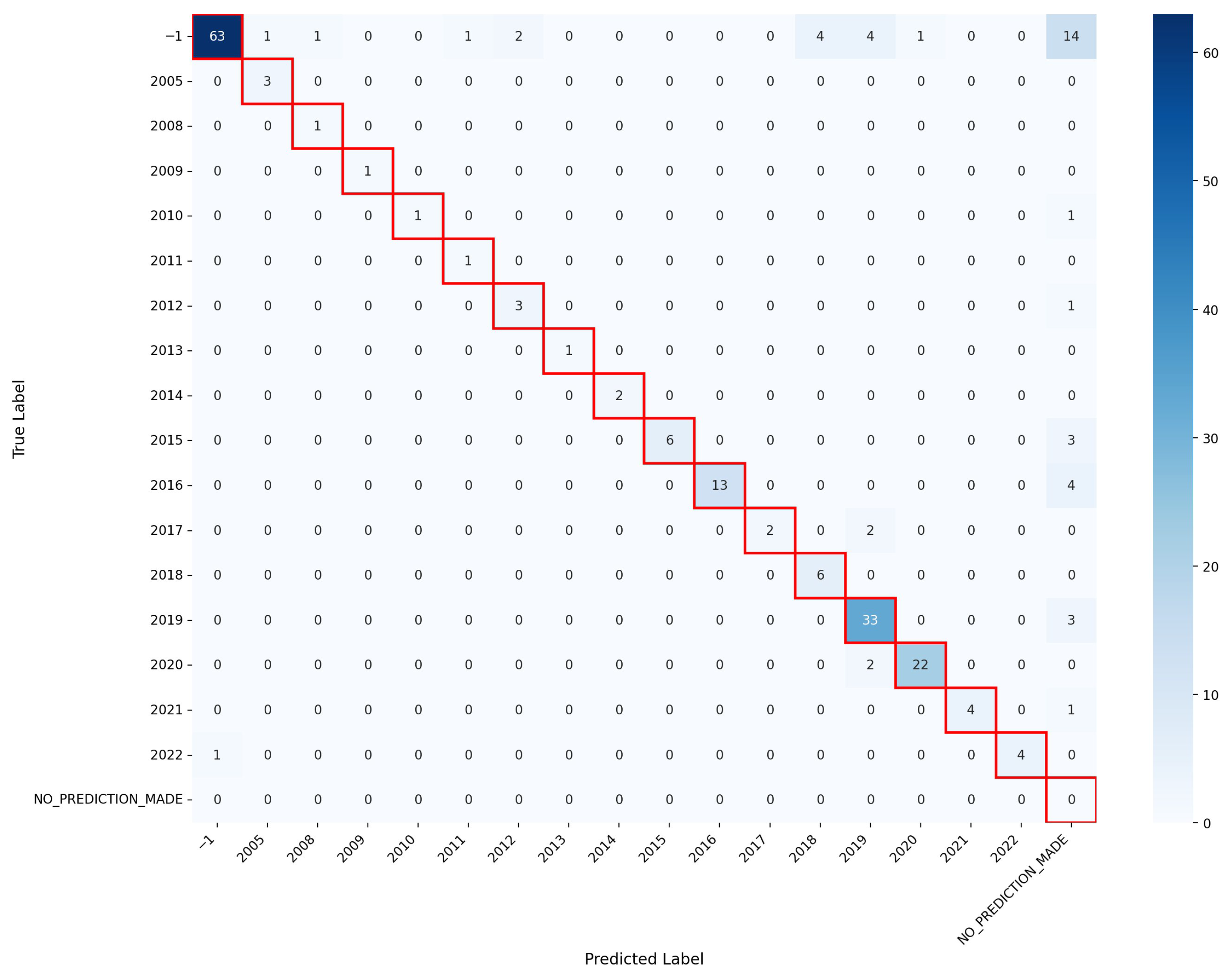

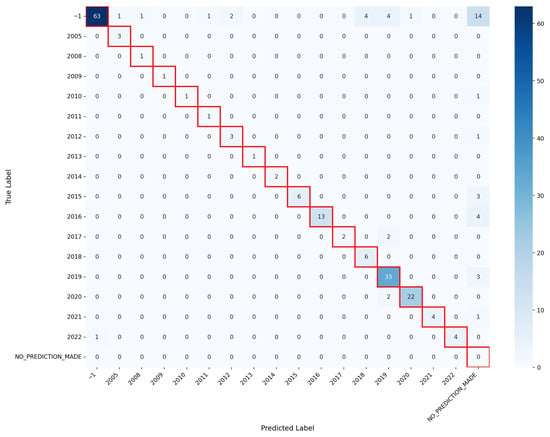

The confusion matrix for the attribute CBN_TARGET_BASE_YEAR shows all classes of the test dataset and visualizes their unbalanced distribution (Figure 6). The extraction of this attribute achieved a weighted-average F1 score of 75.02%, a precision of 87.72%, and a recall of 70.28%.

Figure 6.

Confusion matrix of the attribute CBN_TARGET_BASE_YEAR.

Most errors stem from NO_PREDICTION_MADE outputs and wrong predicted classes that should have been assigned to the −1 category. Consequently, the recall remains low. This implies that the model, in some cases, did not recognize an ESG metric with a missing base year or hallucinated values for missing base years. Still, the diagonal of the confusion matrix indicates that most classes are extracted correctly if a year was reported.

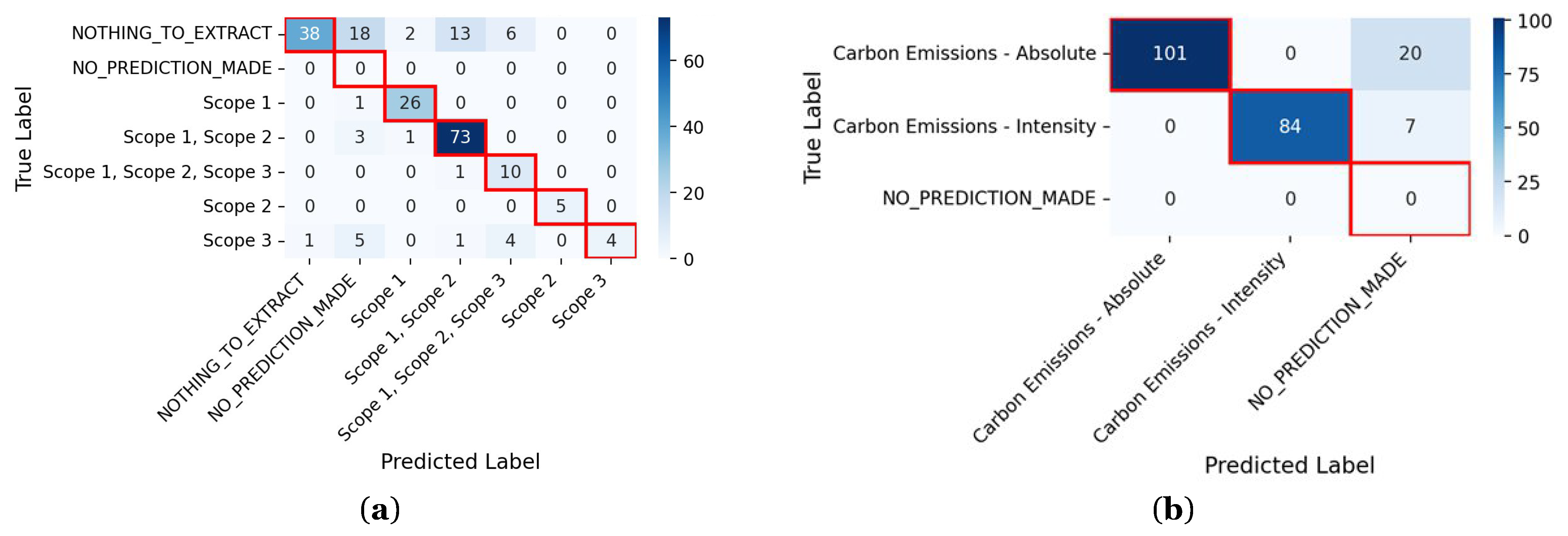

The confusion matrix for TARGET_CARBON_SCOPE_123_CATEGORY in Figure 7a shows that the model can generally differentiate between the individual scope categories, as indicated by the strong diagonal. However, a notable share of predictions falls into classes that should not have been extracted. These over-extractions suggest that the model occasionally assigns scope values even when no relevant information is present on the page. Another pattern is visualized in the confusion matrix of CBN_TARGET_CATEGORY in Figure 7b. The model reliably distinguishes between absolute and intensity targets. There are no misclassifications between these two categories, as represented by the clean diagonal. The dominant error type is not over-extraction but missing predictions: 20 instances of absolute targets and 7 instances of intensity targets were not made due to missing metrics. This means that the model fails to extract a category even though one is present in the document.

Figure 7.

Confusion matrices of two attributes: (a) TARGET_CARBON_SCOPE_123_CATEGORY; (b) CBN_TARGET_CATEGORY.

When comparing layout types using the text + image modality, simple layouts showed lower missing metrics and higher extraction quality than complex layouts. The weighted page-level extraction quality reached 96.69% for simple layouts and 96.21% for complex layouts, while the weighted attribute-level extraction quality was 84.73% and 78.88% respectively. Precision and recall were also slightly higher for simple layouts. These results indicated that simple layouts remain easier for the model to parse, as also over-extractions are more pronounced in complex layouts (53.92%) than in simple ones (46.97%). It can be interpreted that the model tended to generate additional, non-existent attributes when confronted with visually dense or irregular page structures. Missing metrics remained lower than in simple layouts but did not compensate for the reduced precision and recall. The attribute-level macro-average F1 score was higher for complex layouts (55.46%) due to more balanced performance across attributes, but all absolute performance levels remained higher for simple layouts.

For complex layouts, performance decreased across all modalities. Text + image remained the best-performing input type, with missing metrics reduced to 15.04%, compared to more than 20% for text-only and image-only. The weighted attribute-level precision for the complex layouts decreased to 88.95%, and the recall dropped to 73.14%.

5. Discussion

The results show that VLMs, despite producing a higher noise ratio with images than with text-only inputs, were able to extract more metrics from complex layouts. Visual input adds value primarily on irregular layouts by reducing missed metrics, but it increases noise. Accordingly, multimodal processing should be applied selectively rather than as a default. Over-extractions were a lot more common on pages where metrics existed than on irrelevant pages. Text-only extraction occasionally matched or exceeded multimodal performance, indicating that visual cues must be integrated carefully to avoid unnecessary errors.

Any real-world application still requires human oversight due to the remaining errors, also for pages where no metrics were identified. The lower recall compared to precision aligns with earlier work and reflects the tendency of VLMs to miss attributes more often than they falsely extract them [4,27].

Although relevant pages were identified at a high rate and the absence of an information retrieval step avoided the risk of discarding information, this design choice also increases computational cost. An IR step could reduce costs by limiting pages passed to the model. The model would then be provided with the relevant pages instead of receiving roughly 50–100 pages per company. Its effect on over-extraction is uncertain and would need empirical validation. The findings also motivate integrating the model into a RAG system capable of processing visual information or using vision-based retrieval to supply relevant pages [29].

Vision encoders at high resolution are computationally intensive, which leads to roughly three times longer durations for VLMs until the first token is issued as well as slightly increased costs, depending on the model provider. In our study, the multimodal context of the final prompt was 2.25× more expensive than the text-only context. Especially in financially constrained environments, this can be a problem compared to purely text-based methods.

Compared with earlier work, the study demonstrates that VLM-based extraction can reach acceptable quality when iterative prompt refinement is applied. While Gupta et al. [27] were unable to show that a VLM could reliably extract sustainability metrics, the present results indicate that targeted improvements, including revised task descriptions, error-oriented prompt modifications, and few-shot examples, can substantially raise extraction accuracy. Our results, unlike prior studies, examined and compared prompt patterns, different VLMs, PDF conversion methods, and modality combinations in detail.

However, the study is limited by the observation that, although iterative prompting enabled high accuracy extractions, overlooked data remain an issue, repeating findings from earlier research [27].

Also, the adjusted MSCI-based dataset may contain residual annotation errors. The narrow domain focus on GHG emission-reduction targets and the oil and gas sector also restricts generalizability. Future research, however, could use our described evaluation setup, which enables comparison across multiple extracted metrics with flexible attribute configurations. The published code, as well as the prompt parts, can be used to expand the study to other domains. However, the entire extraction process and substantial parts of the prompt structure are largely domain-agnostic and transferable to other metrics. While specific prompt constraints were tailored to GHG emission-reduction targets to mitigate hallucinations, the underlying pipeline can be adapted for any classifiable ESG metric. The prompt schema can be reused for other ESG metrics, though it requires adaptation, as the current components explicitly incorporate GHG-related terminology and rules. To facilitate this adaptation, a generalized version of the prompt, with GHG-specific components removed, is provided in Appendix D. For successful transfer to new domains, the metric with its attributes must be described as prescriptively as possible to minimize the model’s scope for interpretation. Furthermore, we recommend the strategic use of few-shot examples.

Prompt engineering is a new technique and was mostly performed experimentally. Automatic prompt-optimization could have been used instead [41,42]. More improved multimodal fusion strategies of sustainability report pages may address the limitations of naïve text + image combinations. The absence of strictly controlled single-factor ablation studies makes it difficult to disentangle the relative contribution of our design choices. Future research should therefore conduct systematic ablation experiments that isolate individual factors.

We see the most promising direction for the proposed artifact in its integration into operational ESG analytics pipelines, where extracted metrics are not consumed directly but serve as inputs to expert-driven assessment and validation workflows [43]. In such settings, the inclusion of a human-in-the-loop (HITL) is essential, as false negatives may be more consequential than over-extracting candidate values that can later be disregarded by domain experts. This perspective is in line with recent HITL literature, which emphasizes the value of prioritizing recall in information extraction systems when humans are available to guide or correct outputs, as experts can more easily filter wrong suggestions than discover absent facts in large corpora [20]. Consequently, the proposed artifact should be understood as a component within an analyst-assisted paradigm rather than as part of a fully automated ESG evaluation pipeline, which would not be suited for high-stakes decision contexts [44].

HITL mechanisms are particularly necessary for handling edge cases in which model confidence is low. Determining model confidence still remains a design challenge. Prior work suggests several approaches, including prompt-level self-assessment [41] estimation derived from multiple model runs and evidence-based confidence signals with calculated validations [12]. Confidence values could also be used to improve the matching algorithm used [22]. A continuous feedback loop in such a system could help identify common errors and adapt metric descriptions in the prompt. In a potential human-in-the-loop setting, the extracted attribute CBN_TARGET_DESC could support traceability by providing contextual evidence for identified targets. We cannot give indications regarding the correctness or practical usefulness of the generated descriptions. Manual expert assessment would therefore be required. We also considered automatic evaluation methods, such as exact matching or embedding-based similarity for future studies.

6. Conclusions

This study examined how existing Vision Language Models can be applied and adapted to extract greenhouse gas emission-reduction targets from sustainability reports. Following a design science approach, we developed and evaluated a multimodal extraction artifact that processes report pages directly and produces structured ESG metrics under realistic document and layout conditions.

From an engineering perspective, the paper contributes an extensible extraction pipeline that integrates page-level data, structured prompting, few-shot adaptation, and an automated evaluation procedure. The results demonstrate that such a pipeline can achieve stable extraction quality across heterogeneous layouts and outperform text-only baselines in visually complex settings. The remaining missing metrics and over-extractions underline that the artifact still requires human validation in practical applications.

From a scientific perspective, the contribution of this work lies not in proposing new model architectures or learning paradigms, but in providing systematic empirical insights into the behavior of VLMs in document-level information extraction tasks using GHG emission reduction targets as an example. The results show that multimodal inputs do not uniformly improve performance, but instead introduce a trade-off between higher recall on complex layouts and increased noise. Moreover, the study highlights recurring failure modes of VLMs, such as inference-based hallucinations and layout-dependent over-extraction, and illustrates how targeted prompt design and few-shot examples can mitigate these effects. By comparing models, modalities, and preprocessing strategies within a controlled experimental setup, the paper clarifies under which conditions visual information adds value.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.W. and M.S.; methodology, L.W. and C.B.; software, C.B.; validation, L.W. and C.B.; data curation, C.B.; writing—original draft preparation, L.W.; writing—review and editing, C.B. and M.S.; supervision, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in a persistent repository at https://doi.org/10.25625/KSIU6U (accessed on 27 November 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CBN | Carbon |

| DPI | Dots per Inch |

| DSRM | Design Science Research Methodology |

| ESG | Environmental, Social, and Governance |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| IE | Information Extraction |

| IR | Information Retrieval |

| JSON | JavaScript Object Notation |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| OCR | Optical Character Recognition |

| RAG | Retrieval-Augmented Generation |

| VLM | Vision Language Model |

| XML | Extensible Markup Language |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Distribution of the metrics’ attributes in the three datasets.

Table A1.

Distribution of the metrics’ attributes in the three datasets.

| Attribute | No Value | Extractions | No. of Classes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Train dataset | |||

| CBN_TARGET_CATEGORY | 0 | 18 | 2 |

| CBN_TARGET_REDUC_PCT | 6 | 12 | 7 |

| TARGET_CARBON_PROGRESS_PCT | 16 | 2 | 2 |

| TARGET_CARBON_SCOPE_123_CATEGORY | 2 | 16 | 4 |

| NET_ZERO_CLAIM_TYPE | 14 | 4 | 2 |

| CBN_TARGET_BASE_YEAR | 7 | 11 | 6 |

| CBN_TARGET_BASE_YEAR_VAL | 14 | 4 | 5 |

| CBN_TARGET_YEAR | 0 | 18 | 7 |

| CBN_TARGET_YEAR_VAL | 14 | 4 | 5 |

| TARGET_CARBON_TYPE | 8 | 10 | 3 |

| TARGET_CARBON_UNITS | 8 | 10 | 10 |

| Validation dataset | |||

| CBN_TARGET_CATEGORY | 0 | 52 | 2 |

| CBN_TARGET_REDUC_PCT | 19 | 33 | 13 |

| TARGET_CARBON_PROGRESS_PCT | 49 | 3 | 4 |

| TARGET_CARBON_SCOPE_123_CATEGORY | 16 | 36 | 5 |

| NET_ZERO_CLAIM_TYPE | 34 | 18 | 2 |

| CBN_TARGET_BASE_YEAR | 20 | 32 | 9 |

| CBN_TARGET_BASE_YEAR_VAL | 46 | 6 | 7 |

| CBN_TARGET_YEAR | 0 | 52 | 10 |

| CBN_TARGET_YEAR_VAL | 48 | 4 | 5 |

| TARGET_CARBON_TYPE | 44 | 8 | 3 |

| TARGET_CARBON_UNITS | 44 | 8 | 8 |

| Test dataset | |||

| CBN_TARGET_CATEGORY | 0 | 212 | 2 |

| CBN_TARGET_REDUC_PCT | 69 | 143 | 39 |

| TARGET_CARBON_PROGRESS_PCT | 195 | 17 | 12 |

| TARGET_CARBON_SCOPE_123_CATEGORY | 77 | 135 | 6 |

| NET_ZERO_CLAIM_TYPE | 159 | 53 | 2 |

| CBN_TARGET_BASE_YEAR | 91 | 121 | 17 |

| CBN_TARGET_BASE_YEAR_VAL | 191 | 21 | 20 |

| CBN_TARGET_YEAR | 4 | 208 | 15 |

| CBN_TARGET_YEAR_VAL | 183 | 29 | 27 |

| TARGET_CARBON_TYPE | 152 | 60 | 5 |

| TARGET_CARBON_UNITS | 152 | 60 | 45 |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Features of the VLMs (costs from deepinfra.com, accessed on 12 December 2025).

Table A2.

Features of the VLMs (costs from deepinfra.com, accessed on 12 December 2025).

| Model | Context Window | Input Costs | Output Costs | Model Size | Company |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gemini 2.0 Flash | 1,048,576 | 0.1 €/million token | 0.4 €/million token | Unknown | Google, Mountain View, CA, USA |

| Mistral Small 3.2 | 128,000 | 0.075 €/million token | 0.2 €/million token | 24 B | Mistral AI, Paris, France |

| GPT-4.1 Mini | 1,047,576 | 0.4 €/million token | 1.6 €/million token | Unknown | OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA |

| Llama4 Scout | 10,000,000 | 0.08 €/million token | 0.3 €/million token | 109 B | Meta, Menlo Park, CA, USA |

Appendix C

Table A3.

Parts of the Minimal Prompt.

Table A3.

Parts of the Minimal Prompt.

| Text | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Your task is to extract absolute and interim GHG-Emission targets from an image and/or a <context> extracted from an ESG report; both contain the same information. Your answer should contain just the relevant information. | Instruction |

| <json_schema_descriptions> **Never guess or infer**. If an attribute is not in the context, use the default (-1 for numbers, “NOTHING_TO_EXTRACT” for strings). CBN_TARGET_DESC: “Target description text (1-2 sentences) from where the information was found. Use NOTHING_TO_EXTRACT if not found.” CBN_TARGET_CATEGORY: “Carbon/Energy Target Category of the GHG-Metric. Choose one of these: Carbon Emissions - Absolute, Carbon Emissions - Intensity, Energy Consumption - Absolute, Energy Consumption - Intensity.” CBN_TARGET_REDUC_PCT: “Overall percentage reduction (%) the company aims to achieve between the CO2e equivalent reduction base year (CBN_TARGET_BASE_YEAR) and the CO2e reduction target year (CBN_TARGET_YEAR). Decimal (%). Use -1 if not found.” TARGET_CARBON_PROGRESS_PCT: “Progress already achieved of towards the CBN_TARGET_REDUC_PCT. Decimal (%). Use -1 if not found.” TARGET_CARBON_SCOPE_123_CATEGORY: “Greenhouse gas scope(s) covered by the target. Scope 1, 2, and 3 can be combined. This is easy you just need to look for the relevant entities inside the text. Other categories (e.g., Energy use) must be a single element.” NET_ZERO_CLAIM_TYPE: “Claim that the Company aims to be “Net Zero” at some point. There also must be a CBN_TARGET_YEAR to be extracted.” TARGET_CARBON_TYPE: “Indicates whether the GHG-Reduction Target is Absolute or Intensity-based. Choose one of: Absolute, Sales intensity, Production intensity, Other. Use NOTHING_TO_EXTRACT if not found.” TARGET_CARBON_UNITS: “Unit of measure used for the GHG-metric (e.g., tCO2e per USD million revenue, MJ, % of operations, etc.). Use NOTHING_TO_EXTRACT if not found.” CBN_TARGET_BASE_YEAR: “Base year of the GHG-Metric. Integer. Use -1 if not disclosed.” CBN_TARGET_BASE_YEAR_VAL: “Base value associated with the CBN_TARGET_BASE_YEAR. Can be a percentage (%) or a unit-based value. Decimal. Use -1 if not found.” CBN_TARGET_YEAR: “Year by which the GHG-metric is intended to be met. Integer. Use -1 if not found.” CBN_TARGET_YEAR_VAL: “Targeted reduction target of the CBN_TARGET_YEAR. Decimal. Use -1 if not found.” </json_schema_descriptions> | Attribute descriptions |

| <json_schema> { “$schema”: “http://json-schema.org/draft-07/schema#”, “title”: “ESG Targets Extraction Schema”, “type”: “object”, “properties”: { “CBN_TARGET_DESC”: { “type”: “string” }, “CBN_TARGET_CATEGORY”: { “type”: “string”, “enum”: [ “Carbon Emissions - Absolute”, “Carbon Emissions - Intensity”, “Energy Consumption - Absolute”, “Energy Consumption - Intensity” ] }, “CBN_TARGET_REDUC_PCT”: { “type”: “number”, “default”: -1 }, “TARGET_CARBON_PROGRESS_PCT”: { “type”: “number”, “default”: -1 }, “TARGET_CARBON_SCOPE_123_CATEGORY”: { “type”: “array”, “minItems”: 1, “uniqueItems”: true, “items”: { “type”: “string”, “enum”: [“Scope 1”, “Scope 2”, “Scope 3”, “Energy use”, “NOTHING_TO_EXTRACT”] } }, “NET_ZERO_CLAIM_TYPE”: { “type”: “string”, “enum”: [“Net Zero”, “Scientific Net Zero”, “SBTI Net Zero”, “NOTHING_TO_EXTRACT”] }, “TARGET_CARBON_TYPE”: { “type”: “string”, “enum”: [“Absolute”, “Sales intensity”, “Production intensity”, “Other”, “NOTHING_TO_EXTRACT”] }, “TARGET_CARBON_UNITS”: { “type”: “string”, “default”: “NOTHING_TO_EXTRACT” }, “CBN_TARGET_BASE_YEAR_VAL”: { “type”: “number”, “default”: -1 }, “CBN_TARGET_BASE_YEAR”: { “type”: “integer”, “default”: -1 }, “CBN_TARGET_YEAR_VAL”: { “type”: “number”, “default”: -1 }, “CBN_TARGET_YEAR”: { “type”: “integer”, “default”: -1 } }, “required”: [ “CBN_TARGET_DESC”, “CBN_TARGET_CATEGORY”, “CBN_TARGET_REDUC_PCT”, “TARGET_CARBON_PROGRESS_PCT”, “TARGET_CARBON_SCOPE_123_CATEGORY”, “NET_ZERO_CLAIM_TYPE”, “CBN_TARGET_BASE_YEAR”,”CBN_TARGET_BASE_YEAR_VAL”, “CBN_TARGET_YEAR”, “CBN_TARGET_YEAR_VAL”, “TARGET_CARBON_TYPE”, “TARGET_CARBON_UNITS” ], “additionalProperties”: false } </json_schema> This is how your answer should look like if you dont see a GHG-Emission-Target (ALWAYS INCLUDE THE XML TAGS): <extraction> [] </extraction> This is how your answer should look like if you see one or more GHG-Emission-Targets (ALWAYS INCLUDE THE XML TAGS): <extraction> [ {{ ‘CBN_TARGET_CATEGORY’: ‘...’, ... }}, ... ] </extraction> <context> … </context> Now extract the GHG-Metrics from the given context: | Response Template |

Table A4.

Changed Parts of the Extended Prompt.

Table A4.

Changed Parts of the Extended Prompt.

| Text | Purpose |

|---|---|

| You are an expert in Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) extraction, specializing in Greenhouse Gas Reduction Target (GHG) metrics. You are the top performer in your department, tasked with extracting **company-wide** absolute and interim GHG and CO2e (equivalent) reduction targets from ESG reports. These targets represent aggregated, summarized data for the entire company, not individual emissions sources. You will be provided with a context (text, image, or both containing identical information, contained in text, tables and figures). As the company’s most experienced and motivated expert, your objective is to meticulously read the context for relevant GHG reduction metrics. Accuracy and comprehensiveness of your extraction are crucial Exceptionally good work will be rewarded with 1000$ bonuses. | Instruction and Persona |

| <language_info> The prompt uses the following terms: - “Metric/ESG Metric/ESG-GHG-Metric” refers to a greenhouse gas reduction target extracted from the context and represented as a JSON object with key-value pairs (attributes). Each metric is defined by a unique combination of enabled (“on”) and disabled (“off”) attributes. </language_info> | Meta-Language |

| You follow these guidelines: <guidelines> - Focus on company-wide GHG-reduction emissions reduction targets: The target must represent the entire company’s CO2e emissions. - Populate all fields in the JSON schema: Use default values if attribute not present for given metric (e.g., -1 for numerical values, “NOTHING_TO_EXTRACT” for strings). - Extract the esg-metrics precisely. - Adhere strictly to the provided JSON schema: Format your answers correctly. - Always include every key-value pair defined in the JSON schema in your JSON objects. - If a target is presented as a range, select the *higher* value. - Exclude Single Emitter Targets: If a target describes only a singular greenhouse gas emitter (e.g., methane), do not include it. - *Absolutely no inference of scope*: The scope *must* be directly and explicitly found in the OCR text. Do not use contextual understanding or external knowledge to determine the scope. If absent, use the default. - *Numbers must be directly linked to the target*: Extract numbers ONLY if they are part of the target statement (e.g., “Reduce emissions by 20%”). Do not extract numbers from unrelated tables, figures, or text, even if they seem relevant. </guidelines> | Best Practices |

| <extraction_ruleset> - TARGET_CARBON_TYPE and TARGET_CARBON_UNITS must either *both* be NOTHING_TO_EXTRACT or *both* be extracted from the context. If one is present, the other must also be explicitly stated. - If a TARGET_CARBON_UNITS is found in the context, TARGET_CARBON_TYPE must also be present. - For absolute targets, only populate TARGET_CARBON_TYPE and TARGET_CARBON_UNITS if *both* are explicitly stated in the context. - A NET_ZERO_CLAIM_TYPE must have a corresponding CBN_TARGET_YEAR to be extracted. Do not extract “Net Zero” claims without a target year. - CBN_TARGET_BASE_YEAR_VAL and CBN_TARGET_YEAR_VAL represent the value of TARGET_CARBON_UNITS. For example, a figure showing 100% -> 80% GHG reduction. - TARGET_CARBON_PROGRESS_PCT describes the progress in percentage already made towards achieving the desired target. </extraction_ruleset> | Extraction descriptions |

Table A5.

Changed Parts of the Final Prompt.

Table A5.

Changed Parts of the Final Prompt.

| Text | Purpose |

|---|---|

| <examples> <example> … </example> <extraction> … </extraction> <example> … </example> <extraction> … </extraction> <example> … </example> <extraction> … </extraction> <example> … </example> <extraction> … </extraction> <example> … </example> <extraction> … </extraction> </examples> | Few-Shot examples |

Appendix D

Table A6.

Prompt template for the usage with other metrics.

Table A6.

Prompt template for the usage with other metrics.

| You are an expert in Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) extraction, specializing in [METRIC_NAME] metrics. You are the top performer in your department, tasked with extracting [METRIC_NAME] from ESG reports. You will be provided with a context (text, image, or both containing identical information, contained in text, tables and figures). As the company’s most experienced and motivated expert, your objective is to meticulously read the context for relevant [METRIC_NAME]. Accuracy and comprehensiveness of your extraction are crucial Exceptionally good work will be rewarded with 1000$ bonuses. <language_info> The prompt uses the following terms: “Metric/ESG Metric “ refers to a [METRIC_NAME] extracted from the context and represented as a JSON object with key-value pairs (attributes). Each metric is defined by a unique combination of enabled (“on”) and disabled (“off”) attributes. </language_info> You follow these guidelines: <guidelines> - Populate all fields in the JSON schema: Use default values if attribute not present for given metric (e.g., -1 for numerical values, “NOTHING_TO_EXTRACT” for strings). - Extract the esg-metrics precisely. - Adhere strictly to the provided JSON schema: Format your answers correctly. - Always include every key-value pair defined in the JSON schema in your JSON objects. - If a target is presented as a range, select the *higher* value. [FURTHER_GUIDELINES] </guidelines> <json_schema_descriptions> **Never guess or infer**. If an attribute is not in the context, use the default (-1 for numbers, “NOTHING_TO_EXTRACT” for strings). TEXTUAL_METRIC_ATTRIBUTE: “[SHORT_DESCRIPTION]. [SHOW_ONE_OR_MORE_OF_POSSIBLE_CLASSES]. Use NOTHING_TO_EXTRACT if not found.” NUMERICAL_METRIC_ ATTRIBUTE: “[SHORT_DESCRIPTION]. [UNIT_TYPE]. Use -1 if not found.” … </json_schema_descriptions> <json_schema> [INDIVIDUAL_JSON_SCHEMA_FOR_TASK] </json_schema> <extraction_ruleset> [LIST_OF_SPECIAL_RULESETS_FOR_COMPLEX_EXTRACTIONS_AND_RELATIONSHIPS] </extraction_ruleset> This is how your answer should look like if you dont see a [METRIC_NAME] (ALWAYS INCLUDE THE XML TAGS): <extraction> [] </extraction> This is how your answer should look like if you see one or more [METRIC_NAME] (ALWAYS INCLUDE THE XML TAGS): <extraction> [ {{ … }}, ... ] </extraction> <examples> [TEXT TOKEN, IMAGE TOKEN OR BOTH. EXTRACTION PART ARE ALWAYS TEXT TOKENS] <example> … </example> <extraction> … </extraction> </examples> <context> … </context> Now extract the Metrics from the given context: |

References

- Cruz, C.A.; Matos, F. ESG Maturity: A Software Framework for the Challenges of ESG Data in Investment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Bustamante, M.; Espinosa-Leal, L. Natural Language Processing Methods for Scoring Sustainability Reports—A Study of Nordic Listed Companies. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, F.; Kölbel, J.F.; Rigobon, R. Aggregate Confusion: The Divergence of ESG Ratings. Rev. Financ. 2022, 26, 1315–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Shi, M.; Chen, Z.; Deng, Z.; Lei, Z.; Zeng, Z.; Yang, S.; Tong, H.; Xiao, L.; Zhou, W. ESGReveal: An LLM-Based Approach for Extracting Structured Data from ESG Reports. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 489, 144572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escrig-Olmedo, E.; Fernández-Izquierdo, M.; Ferrero-Ferrero, I.; Rivera-Lirio, J.; Muñoz-Torres, M. Rating the Raters: Evaluating How ESG Rating Agencies Integrate Sustainability Principles. Sustainability 2019, 11, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MSCI. MSCI ESG Ratings; MSCI: New York, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, J.; Bingler, J.; Colesanti Senni, C.; Kraus, M.; Gostlow, G.; Schimanski, T.; Stammbach, D.; Vaghefi, S.; Wang, Q.; Webersinke, N.; et al. chatReport: Democratizing Sustainability Disclosure Analysis through LLM-based Tools. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.15770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laokulrach, M. ESG Data and Metrics. In Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Investment and Reporting; Bednárová, M., Soratana, K., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 119–144. [Google Scholar]

- Sneideriene, A.; Legenzova, R. Greenwashing Prevention in Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Disclosures: A Bibliometric Analysis. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2025, 74, 102720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; El Akremi, A.; Jia, M. Quantitative Research on Corporate Social Responsibility: A Quest for Relevance and Rigor in a Quickly Evolving, Turbulent World. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 187, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, H.B.; Hail, L.; Leuz, C. Mandatory CSR and Sustainability Reporting: Economic Analysis and Literature Review. Rev. Acc. Stud. 2021, 26, 1176–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, J.; Steinberg, A.; Dimmelmeier, A.; Domenech Burin, L.; Kormanyos, E.; Fehr, M.; Schierholz, M. Addressing Data Gaps in Sustainability Reporting: A Benchmark Dataset for Greenhouse Gas Emission Extraction. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visalli, F.; Patrizio, A.; Lanza, A.; Papaleo, P.; Nautiyal, A.; Pupo, M.; Scilinguo, U.; Oro, E.; Ruffolo, M. ESG Data Collection with Adaptive AI. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems; Filipe, J., Śmiałek, M., Brodsky, A., Hammoudi, S., Eds.; SCITEPRESS—Science and Technology Publications: Setúbal, Portugal, 2023; pp. 468–475. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffswell, J.; Liu, Z. Interactive Repair of Tables Extracted from PDF Documents on Mobile Devices. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Bronzini, M.; Nicolini, C.; Lepri, B.; Passerini, A.; Staiano, J. Glitter or Gold? Deriving Structured Insights from Sustainability Reports via Large Language Models. EPJ Data Sci. 2024, 13, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordes, F.; Pang, R.Y.; Ajay, A.; Li, A.C.; Bardes, A.; Petryk, S.; Mañas, O.; Lin, Z.; Mahmoud, A.; Jayaraman, B.; et al. An Introduction to Vision-Language Modeling. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.17247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Gao, J.; Tong, X.; Guo, J.; Yang, H.; Qi, J.; Li, R.; Li, N.; Xu, M. Advanced Unstructured Data Processing for ESG Reports: A Methodology for Structured Transformation and Enhanced Analysis. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.02992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Kchouk, M.; Bellato, S.; Gan, M.; El Maarouf, I. FinSim4-ESG Shared Task: Learning Semantic Similarities for the Financial Domain. Extended Edition to ESG Insights. In Proceedings of the Fourth Workshop on Financial Technology and Natural Language Processing (FinNLP@IJCAI-ECAI 2022); Chen, C.-C., Huang, H.-H., Takamura, H., Chen, H.-H., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: San Diego, CA, USA, 2022; pp. 57–63. [Google Scholar]

- Polignano, M.; Bellantuono, N.; Lagrasta, F.P.; Caputo, S.; Pontrandolfo, P.; Semeraro, G. An NLP Approach for the Analysis of Global Reporting Initiative Indexes from Corporate Sustainability Reports. In Proceedings of the LREC 2022 Workshop on The First Computing Social Responsibility Workshop: NLP Approaches to Corporate Social Responsibilities (CSR-NLP I 2022); Wan, M., Huang, C.-R., Eds.; European Language Resources Association (ELRA): Paris, France, 2022; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Wrzalik, M.; Faust, F.; Sieber, S.; Ulges, A. NetZeroFacts: Two-Stage Emission Information Extraction from Company Reports. In Proceedings of the Joint Workshop of the 7th Financial Technology and Natural Language Processing, the 5th Knowledge Discovery from Unstructured Data in Financial Services, and the 4th Workshop on Economics and Natural Language Processing; Chen, C.-C., Liu, X., Hahn, U., Nourbakhsh, A., Ma, Z., Smiley, C., Hoste, V., Das, S.R., Li, M., Ghassemi, M., et al., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Torino, Italia, 2024; pp. 70–84. [Google Scholar]

- Schimanski, T.; Bingler, J.; Hyslop, C.; Kraus, M.; Leippold, M. ClimateBERT-NetZero: Detecting and Assessing Net Zero and Reduction Targets. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.08096. [Google Scholar]

- Dave, A.; Zhu, M.; Hu, D.; Tiwari, S. Climate AI for Corporate Decarbonization Metrics Extraction. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.03402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, N.S.; Agarwal, S. A Comparative Study of PDF Parsing Tools Across Diverse Document Categories. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.09871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Lv, T.; Cui, L.; Lu, Y.; Wei, F. LayoutLMv3: Pre-Training for Document AI with Unified Text and Image Masking. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Multimedia; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 4083–4091. [Google Scholar]

- Do, A.-D.; Do, T.-H. Adapting Vision-Language Models for Information Extraction from Bilingual Medical Invoices. In Proceedings of the 2025 Asia Pacific Signal and Information Processing Association Annual Summit and Conference (APSIPA ASC); IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; p. 2429. [Google Scholar]

- Khalighinejad, G.; Scott, S.; Liu, O.; Anderson, K.L.; Stureborg, R.; Tyagi, A.; Dhingra, B. MatViX: Multimodal Information Extraction from Visually Rich Articles. In Proceedings of the 2025 Conference of the Nations of the Americas Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 1: Long Papers); Chiruzzo, L., Ritter, A., Wang, L., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 2025; pp. 3636–3655. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, T.; Goel, T.; Verma, I. Exploring Multimodal Language Models for Sustainability Disclosure Extraction: A Comparative Study. In Proceedings of the Sixth Workshop on Insights from Negative Results in NLP; Drozd, A., Sedoc, J., Tafreshi, S., Akula, A., Shu, R., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 2025; pp. 141–149. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, W.; Zheng, Y.; Li, Y.; Xu, H.; Nie, D.; Wang, P.; He, Y. Large Language Models in Document Intelligence: A Comprehensive Survey, Recent Advances, Challenges, and Future Trends. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. 2025, 44, 1–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Tang, C.; Xu, B.; Cui, J.; Ran, J.; Yan, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, S.; Han, X.; Liu, Z.; et al. VisRAG: Vision-Based Retrieval-Augmented Generation on Multi-Modality Documents. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2410.10594. [Google Scholar]

- Peffers, K.; Tuunanen, T.; Rothenberger, M.A.; Chatterjee, S. A Design Science Research Methodology for Information Systems Research. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2007, 24, 45–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronczyk, M.; McCurdy, P.; Russill, C. Greenwashing, Net-Zero, and the Oil Sands in Canada: The Case of Pathways Alliance. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 112, 103502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Wang, T.; Cai, P.; Mondal, S.K.; Sahoo, J.P. A Comprehensive Survey of Few-Shot Learning: Evolution, Applications, Challenges, and Opportunities. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A. Micro-Average, Macro-Average, Weighting: Precision, Recall, F1-Score. Anal. Yogi 2023. Available online: https://vitalflux.com/micro-average-macro-average-scoring-metrics-multi-class-classification-python/ (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Leung, K. Micro, Macro & Weighted Averages of F1 Score, Clearly Explained. Towards Data Sci. 2022. Available online: https://towardsdatascience.com/micro-macro-weighted-averages-of-f1-score-clearly-explained-b603420b292f/ (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Foster, I.; Ghani, R.; Jarmin, R.; Kreuter, F.; Lane, J. Big Data and Social Science, 2nd ed.; Chapman & Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, H.W. The Hungarian Method for the Assignment Problem. In 50 Years of Integer Programming 1958-2008: From the Early Years to the State-of-the-Art; Jünger, M., Liebling, T.M., Naddef, D., Nemhauser, G.L., Pulleyblank, W.R., Reinelt, G., Rinaldi, G., Wolsey, L.A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 29–47. [Google Scholar]

- Black, P.E. Greedy Algorithm. Dictionary of Algorithms and Data Structures 2005. Available online: https://xlinux.nist.gov/dads/HTML/greedyalgo.html (accessed on 8 January 2026).

- Poznanski, J.; Rangapur, A.; Borchardt, J.; Dunkelberger, J.; Huff, R.; Lin, D.; Rangapur, A.; Wilhelm, C.; Lo, K.; Soldaini, L. olmOCR: Unlocking Trillions of Tokens in PDFs with Vision Language Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.18443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.; Fu, Q.; Hays, S.; Sandborn, M.; Olea, C.; Gilbert, H.; Elnashar, A.; Spencer-Smith, J.; Schmidt, D.C. A Prompt Pattern Catalog to Enhance Prompt Engineering with ChatGPT. In Proceedings of the 30th Conference on Pattern Languages of Programs; The Hillside Group: Monticello, IL, USA, 2023; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, J.; Li, H.; Ding, X.; Xie, W.; Li, Y.-J.; Zhao, W.; Wan, K.; Shi, J.; Hu, X.; Liu, Z. Understanding and Mitigating Numerical Sources of Nondeterminism in LLM Inference. In Proceedings of the Thirty-ninth Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, San Diego, CA, USA, 2–7 December 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.-C.; Weng, H.-T.; Pardeshi, M.S.; Chen, C.-M.; Sheu, R.-K.; Pai, K.-C. Evaluation of Prompt Engineering on the Performance of a Large Language Model in Document Information Extraction. Electronics 2025, 14, 2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; Sun, H.; Lopez, D.; Das, K.; Malin, B.A.; Kumar, S. Heuristic-Based Search Algorithm in Automatic Instruction-Focused Prompt Optimization: A Survey. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2025; Che, W., Nabende, J., Shutova, E., Pilehvar, M.T., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Vienna, Austria, 2025; pp. 22093–22111. [Google Scholar]

- Birti, M.; Osborne, F.; Maurino, A. Optimizing Large Language Models for ESG Activity Detection in Financial Texts. In Proceedings of the ICAIF ‘25: Proceedings of the 6th ACM International Conference on AI in Finance, Singapore, 15–18 November 2025; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- John, L.; Ghanmi, A.M.; Wittenborg, T.; Auer, S.; Karras, O. ExtracTable: Human-in-the-Loop Transformation of Scientific Corpora into Structured Knowledge. In Proceedings of the Linking Theory and Practice of Digital Libraries; Balke, W.-T., Golub, K., Manolopoulos, Y., Stefanidis, K., Zhang, Z., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2026; pp. 470–487. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.