Abstract

Automatic anomaly detection is vital in domains such as healthcare, finance, and cybersecurity, where subtle deviations may signal fraud, failures, or impending risks. This paper proposes an unsupervised anomaly-detection method called Anomaly Detection Based on Markovian Geometric Diffusion (AD-MGD). The technique is applicable to uni- and multidimensional datasets, employing Markovian Geometric Diffusion to uncover nonlinear structures in the relationships among instances. For multidimensional data, the scale parameter, which is crucial to the performance of the method, is tuned using Shannon entropy. The approach includes a global search followed by local refinement of the scale parameter, promoting adaptability to the data context. Experimental evaluations on synthetic and real datasets show that AD-MGD consistently outperforms classical methods such as KNN, LOF, and IForest in terms of area under the ROC curve (AUC), particularly in heterogeneous data scenarios. The results highlight the potential of AD-MGD in critical anomaly-detection applications, advancing the use of diffusion techniques in data mining.

1. Introduction

The exponential growth in data generation has highlighted the importance of developing robust analytical methods capable of transforming raw records into valuable information. This process, known as Knowledge Discovery in Databases (KDD), aims to extract relevant patterns and identify significant deviations, commonly referred to as anomalies or outliers [1,2]. Accurate detection of such anomalies is critical, as atypical events, such as operational failures, financial fraud, and instrumental errors, can have severe impacts in various contexts, ranging from financial audits to medical diagnostics [3,4].

Although traditional methods based on statistics, distance, density, and clustering are effective in many applications, their reliance on manually tuned parameters often limits robustness and generalization capacity, particularly in noisy or structurally heterogeneous environments [4,5]. A recent evaluation of unsupervised anomaly detection algorithms on real-world tabular datasets showed that performance varies with the anomaly type (global or local) and that many methods require careful hyperparameter selection [4]. Studies on Biological Early Warning Systems (BEWS), for example, which apply unsupervised techniques such as Local Outlier Factor (LOF) and Isolation Forest (iForest), confirm the need for careful tuning to avoid false alarms [6]. Moreover, Isolation Forest (iForest), despite its efficiency, still presents disadvantages such as strong randomness, low generalization, and insufficient stability [7].

Robustness is crucial in practical settings. In Structural Health Monitoring (SHM) tasks, detecting extreme events, such as seismic ones, is complex due to the interference of faulty data and multiple anomaly types (for example, missing data, small deviations, or drift) [8,9]. In addition, non-uniform data loss is a realistic challenge that affects normal structural assessment and the detection of unusual changes [10]. These challenges add to the complexity of industrial anomalies, which often exhibit significant scale variations and demand robust networks [11]. On the other hand, diffusion models have emerged as promising alternatives due to their ability to model complex distributions through iterative denoising processes [12]. This promise is reinforced by the use of graph diffusion models in hierarchical neural networks to enhance data quality and mitigate sparsity or poor quality in sensor networks, such as in machining centers [13]. However, applying these models to anomaly detection remains relatively unexplored.

Diffusion Maps Theory (DMT) offers advantages by capturing the intrinsic geometry of data, showing promising applications in areas such as medical image restoration and industrial quality control [14,15]. Nevertheless, a central challenge remains: developing methods that preserve geometric sensitivity without manual tuning while producing statistically consistent results.

The recent advances reviewed above expose a persistent research gap. Although diffusion-based models excel in vision and sequential data, there is still no unsupervised solution that handles heterogeneous tabular datasets, eliminates manual hyperparameter tuning, and yields an easily interpretable anomaly metric. The relevance of this unsupervised focus is underscored by practice in critical domains such as credit-card fraud detection, often reframed as an unsupervised anomaly detection problem using advanced networks like Autoencoders and GANs [16]. In this context, our goal is to close this gap by introducing Anomaly Detection based on Markovian Geometric Diffusion (AD-MGD), which combines geometric diffusion with automatic scale-parameter selection. Specifically, we test the hypothesis that AD-MGD achieves higher AUC than a representative set of classical detectors (KNN, LOF, IForest, among others) on both synthetic and real benchmarks.

This study presents an unsupervised anomaly detection method that extends Markovian Geometric Diffusion (MGD) [17], a formulation rooted in Diffusion Maps Theory, along with its multivariate variant, extended-MGD (e-MGD). In MGD, a probabilistic reduction is performed on triangular meshes to preserve the object’s essential geometry, whereas e-MGD generalizes this operation to data-mining scenarios by constructing suitable proximity graphs for multi-attribute datasets, prioritizing the preservation of structural information as a preprocessing step rather than merely maximizing classification accuracy. By maximizing Shannon entropy [18] over the diagonal elements of a Markov transition matrix, AD-MGD produces an ordered probability vector that ranks instances by their anomalousness. This approach aligns with the ranking nature of unsupervised anomaly detection and provides interpretable scores that are essential for practical applications [4].

The proposed AD-MGD algorithm couples the geometric diffusion of MGD with an automatic scale-parameter selection rule that maximizes Shannon entropy [18] evaluated over the diagonal elements of the Markov transition matrix. These elements encode direct anomaly probabilities. The resulting ordered probability vector ranks instances by their degree of anomalousness, and the generated boxplots qualitatively confirm that the most atypical cases appear at the top.

To validate this approach, we conducted an extensive experimental evaluation on fifteen different datasets, including one-dimensional synthetic distributions, complex two-dimensional structures, nonlinear three-dimensional scenarios, and four widely recognized real-world datasets. Qualitative assessments revealed clear visual separation between normal and anomalous samples, while quantitatively the method achieved 100% AUC [19] in all analyzed synthetic scenarios. On real-world datasets, average performance surpassed traditional baseline methods.

The main contributions of this work include: (i) the design of an unsupervised method integrating geometric diffusion with entropy-based automatic parameter tuning, and (ii) empirical demonstration of its robustness and generalizability across multiple application contexts.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the pertinent literature. Section 3 introduces the theoretical foundations of Markovian Geometric Diffusion and describes the e-MGD algorithm. Section 4 presents the proposed anomaly-detection framework. Section 5 reports the experimental findings, whereas Section 6 analyzes their implications. Finally, Section 7 summarizes the main contributions and outlines directions for future research.

2. Related Work

This section reviews recent advances in anomaly detection, beginning with the distinction among supervised, unsupervised, and semi-supervised approaches. It then synthesizes traditional techniques, including statistical, density-based, distance-based, clustering, isolation, ensemble, and subspace methods, and highlights solutions grounded in Diffusion Models.

Anomaly detection can be grouped into three main approaches: supervised, which relies on labeled data but is limited by the scarcity of anomalous examples [3]; unsupervised, which assigns anomaly scores to instances without labels but is sensitive to high contamination rates in the data [3,20]; and semi-supervised, which models normal behavior exclusively, without requiring prior knowledge of anomaly characteristics [3,20].

The present work focuses on unsupervised methods, whose relevance is underscored by studies such as Goldstein and Uchida (2016) [21], Domingues et al. (2018) [22], Campos et al. (2016) [23], Pang et al. (2021) [24], and Zamanzadeh et al. (2024) [25]. These works identify three recurring challenges: (i) scalability to large, high-dimensional datasets, (ii) robustness to noise, and (iii) the representation of complex non-linear structures [24,25].

The main studies related to anomaly detection are presented below, with emphasis on unsupervised approaches. This focus reflects scenarios in which reliable labels for rare events are costly or unfeasible, anomaly profiles evolve over time, and adaptive methods without human intervention are preferable. The proposed method (AD-MGD) is intrinsically unsupervised, building a diffusive representation of the data space without class information. Comparative studies also highlight the importance and challenges of this research line, particularly scalability in high-dimensional settings, robustness to noise, and the representation of complex non-linear structures [21,22,23,24,25].

Robustness is essential in practical environments, such as Structural Health Monitoring (SHM), where detecting seismic events is complex due to the interference of faulty data and multiple anomaly types (e.g., missing data, small deviations, or drift) [8,9]. In addition, non-uniform data loss is a realistic challenge that affects normal structural assessment and the detection of unusual changes [10]. In the financial domain, credit-card fraud detection is often reformulated as an unsupervised anomaly detection problem using networks such as Autoencoders and GANs [16]. In this context, the use of the term diffusion in the recent literature warrants clarification.

The term diffusion in the recent literature is applied to two conceptually distinct families. The first corresponds to Diffusion Maps (DMs), a manifold learning technique that builds an affinity graph and applies spectral analysis to obtain a low-dimensional embedding that preserves intrinsic connectivity [26,27]. In this diffusion space, outliers usually appear as isolated points relative to the main manifold [28].

Applications of DMs have demonstrated utility in domains such as network intrusion logs [28], gene expression profiles [29], biomedical signals [30], and industrial processes [31,32]. Their main advantage lies in capturing non-linear geometries. Nevertheless, important challenges remain, including (i) computational cost, (ii) sensitivity to the choice of the scale parameter, and (iii) difficulties with out-of-sample extension (OOSE), which may fail when anomalies are absent from the reference set [26,33,34].

These challenges are particularly relevant in large datasets, where OOSE techniques often rely on sampling [35,36,37,38,39]. The effectiveness of OOSE depends on representative samples, and failures may occur when anomalies are missing, since interpolation rather than extrapolation is performed [28,33,35]. Moreover, an inadequate choice of the scale parameter can reduce separability by connecting anomalies with the background [26,28,37].

The second family includes Generative Diffusion Models, which learn to reverse a noise-adding process [40,41]. These models have been applied to synthesize pseudo-anomalies or to define deviation scores [40,41,42,43]. In machining centers, the use of a graph diffusion augmentation module helps address sparsity and poor quality in sensor datasets [13]. However, generative models require substantial computational power and provide limited interpretability [44], which restricts their adoption. Future work on data reconstruction in SHM considers introducing Diffusion Models or GANs to generate high-fidelity synthetic data as augmentation [10].

Within the realm of classical methods, Samariya et al. (2023) classify 52 algorithms into seven categories: statistical, density-based, distance-based, clustering, isolation, ensemble, and subspace [5]. A recent evaluation by Bouman et al. [4] compared 33 unsupervised algorithms across 52 real-world multivariate tabular datasets whose sizes ranged from 19 to 619,326 samples and whose anomaly prevalence varied from 0.03.

Among unsupervised, statistically based methods, HBOS (Histogram-Based Outlier Score) [45] stands out for its simplicity and scalability. However, HBOS may be less effective when attributes are correlated due to its independence assumption. In the density-based family, LOF (Local Outlier Factor) [46], COF (Connectivity-Based Outlier Factor) [47], LoOP (Local Outlier Probability) [48], and LOCI (Local Correlation Integral) [49] are prominent. Although effective on low-dimensional datasets, they tend to lose performance on sparse or high-dimensional data because reliable density estimation becomes difficult.

Among distance-based approaches, notable algorithms include k-NN (k-Nearest Neighbors) [50,51], kth-NN (kth Nearest Neighbor) [52], ABOD (Angle-Based Outlier Detection) [53], and LDOF (Local Distance-Based Outlier Factor) [54]. These methods detect anomalies as instances that are significantly farther from their nearest neighbors. Although effective for simple, well-separated distributions, their performance degrades on data with non-linear structures and in high-dimensional spaces.

In the isolation-based category, Isolation Forest (IForest) [55] is notable for its efficiency. However, traditional IForest presents disadvantages such as strong randomness, low generalization, and insufficient stability [7]. Studies on Biological Early Warning Systems that apply IForest and LOF confirm that accurate anomaly detection requires careful hyperparameter selection to avoid false alarms [6].

Low-cost hybrid strategies such as AEKNN (AutoEncoder KNN) [56] and SECODA (Segmentation-and Combination-based Detection of Anomalies) [57] mitigate some of these limitations but remain detached from advances in Diffusion Map theory.

Taken together, this body of evidence naturally leads to the gap that this work seeks to fill. There is still no comprehensive investigation of Markovian Geometric Diffusion in heterogeneous tabular data such as financial transactions, clinical records, industrial production logs, and administrative registries. Moreover, the limitations of traditional methods and those based on neural networks, including reliance on manual hyperparameter tuning, performance that varies with anomaly type for example, global versus local, and lack of interpretability [4], reinforce the need for a robust and adaptable approach. By combining the geometric robustness of DGM with computationally efficient local operations, the proposed AD-MGD algorithm provides a reliable anomaly detection tool for domains that require high dependability, including public expenditure audits, clinical monitoring, and industrial process supervision.

3. Markov Geometric Diffusion and the Extended-MGD Method

This section introduces the theoretical foundations of the Markovian Geometric Diffusion (MGD) method [17] and its extension to generic data sets, termed extended MGD (e-MGD) [58]. Both approaches are grounded in Diffusion Maps theory [26,27,59], which models information flow as a heat-diffusion process in which data elements are treated as particles connected by “bars” that encode pairwise relationships; the “heat” that diffuses along these links represents the information propagated through the system, so elements that retain more heat are considered more representative and are therefore preserved during simplification [58].

MGD represents a three–dimensional mesh as a weighted graph in which each vertex is viewed as a state of a Markov chain and each edge captures geometric adjacency between and . The weight is defined by a symmetric, positive Gaussian kernel that quantifies the similarity between adjacent vertices via the difference between their unit normal vectors; it is evaluated only for connected vertex pairs [17].

The kernel is given by [17]

where and denote the unit normals at vertices and , respectively. Any kernel used in MGD or e-MGD must satisfy symmetry, off-diagonal non-negativity, and on-diagonal positivity, which guarantee a probabilistic interpretation of the diffusion operator [17,26,59,60].

Row-wise normalisation produces the transition matrix

with

ensuring that for every state. Although the kernel itself is symmetric, the resulting matrix P is generally non-symmetric owing to local connectivity [17].

The representativeness of a vertex (or instance) is assessed by combining its self-transition probability with its degree [17]:

Low values of mark regions of high local similarity and are therefore prioritised for removal. By the Hoffman–Wielandt theorem [61], eliminating states whose corresponding diagonal entries in the transition matrix P are small perturbs its spectrum only minimally, which preserves the global structure of the data. The iterative procedure terminates when the moving average of stabilises [17].

The e-MGD method [58] extends the diffusion logic to generic data sets. During preprocessing, heterogeneous attributes, whether differing in nature or scale, are rescaled to the interval . The space is then partitioned into adaptive hypercubes, and at most P neighbours per instance are selected via Monte Carlo sampling. A user-defined Gaussian kernel allows tailored handling of continuous, categorical, or mixed attributes. The same importance score guides instance suppression, with the additional requirement of retaining at least one representative per neighbourhood. Elimination proceeds iteratively until the user-specified reduction ratio is reached.

4. Anomaly Detection Based on Markovian Geometric Diffusion

This section describes the Anomaly Detection by Markovian Geometric Diffusion (AD-MGD) algorithm, conceived as an extension of the MGD and e-MGD methods for automatic outlier detection. Starting from the diffusion graph, the diagonal elements of the transition matrix P (Equation (9)) are computed; the instances are then ranked in descending order of abnormality, placing at the top those with the highest probability of being outliers.

The procedure comprises four phases: (i) data preprocessing (Equation (7)); (ii) local graph construction via K-nearest neighbors (KNN) to define neighborhood relations and sparsify the affinity structure; (iii) estimation of the scale parameter by maximizing Shannon entropy [18] applied to the diagonal entries of P (Equation (11)); and (iv) final computation and sorting of the corresponding scores (Equations (9) and (12)). Algorithm 1 summarizes the entire pipeline, and the following subsections detail each step.

4.1. Pre-Processing

This subsection describes the data preprocessing in AD-MGD, which involves Min-Max normalization of all attributes to the interval , thereby equalizing scales and ensuring numerical stability for accurate anomaly detection. Each instance was normalized using the Min-Max method [62], which maps every attribute to the interval according to

where is the normalised value of the j-th attribute of instance , and and denote, respectively, the minimum and maximum of attribute j in the entire data set. Normalisation prevents large-scale features from dominating the similarity computation, preserves the relative relationships among instances, and facilitates reliable outlier ranking. It also improves numerical stability and accelerates convergence in the subsequent AD-MGD calculations.

4.2. Local Graph Construction via K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN)

This subsection introduces the construction of the local neighborhood graph, which provides the structural foundation for the diffusion process. By modeling neighborhood relations through K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), AD-MGD is able to capture both local and global geometric patterns in the data, ensuring a balanced representation for anomaly detection.

To model the geometric structure of the data, AD-MGD constructs a neighborhood graph based on KNN. For each instance , a set with the k closest instances is identified according to the Euclidean metric.

Local connectivity is then quantified using a Gaussian kernel (heat kernel) applied to the distances:

applied only for . The value of k controls the local reach of diffusion: smaller values highlight microstructures and point anomalies, while larger values smooth irregularities and reinforce global structures.

| Algorithm 1 Markovian Geometric Diffusion-Based Anomaly Detection |

|

To ensure probabilistic interpretability, the weights of each instance are normalized so that the sum of each row of the transition matrix equals 1. The normalization term is given by:

where the term 1 represents the self-loop. The transition matrix thus becomes sparse and locally adapted.

Finally, a minimum value of was adopted to guarantee minimal local connectivity and stable estimates of transition probabilities. The parameter k was automatically adjusted for each dataset, keeping it small relative to the sample size n, in order to balance local sensitivity and global robustness. KNN queries were performed using a KD-tree [63] in multidimensional datasets, leveraging spatial indexing to optimize search speed. In cases where , the brute force method was used, which preserves exact results with a total computational complexity of for graph construction. It is worth noting that a stable mergesort was adopted to order KNN distances, resolving ties deterministically and keeping the sample itself in the first position (self-neighbor). Thus, the self element is excluded from the neighbor weight summation (only are considered), preserving the definition of and ensuring reproducibility of results, with negligible additional cost since it operates on vectors of size k per row.

4.3. Scale Parameter

This subsection defines the Gaussian kernel scale paramete and explains how it is estimated by maximising Shannon entropy through a global logarithmic grid search followed by local refinement.

The diffusion (scale) parameter governs the radius of influence of the Gaussian kernel that builds the similarity graph. Small values of privilege local connections, yielding sparse transition matrices that capture fine geometric detail, whereas large values promote near-uniform connectivity and consequently blur relevant variations [26,64].

Hyper-parameter selection for stochastic models, such as choosing , is crucial, yet ad hoc heuristics remain common because no universally optimal value exists. We introduce an information-theoretic criterion: select the that maximises the Shannon entropy of the diagonal entries of the transition matrix, which correspond to the self-transition probabilities. To the best of our knowledge, this criterion has not previously appeared in the literature.

Statistically, Shannon entropy quantifies the uncertainty or disorder of a system: higher entropy indicates greater variability in the probability distribution and thus increased unpredictability. Leveraging this principle, the proposed strategy uses the entropy of the diagonal of P as a dynamic regulariser. Maximising this quantity discourages extreme persistence, that is, states that are either too stable or purely transient, and yields a more homogeneous distribution of self-transition probabilities. The resulting model is less susceptible to overfitting fragile or noisy dynamics, enhancing its capacity to generalise. Unlike methods that require external training data, this approach relies solely on intrinsic properties of P. The corresponding mathematical formulation is presented below.

Let denote the transition matrix introduced in Equation (2), where

is the Gaussian kernel and the normalisation term is given in Equation (3).

This Gaussian kernel (Equation (3) represents a generalization of the original MGD method, which employed normal vectors for mesh simplification, to the context of generic datasets (e-MGD). This change replaces the reliance on normal vectors with the Euclidean distance () in feature space, which is essential for applying the method to multivariate tabular data. The scale parameter is crucial for modulating this local connectivity.

The diagonal entries

quantify the probability of remaining at state . The Shannon entropy associated with these probabilities is

and the scale parameter selected under the Shannon criterion is

Maximising the entropy of the self-transition probabilities strikes a balance between local connectivity and global diversity, thereby widening the gap between dense regions (inliers) and sparse regions (outliers) in anomaly-detection tasks.

The formulation of the Gaussian kernel (Equation (8)) and the definition of the Shannon entropy maximization criterion (Equation (10)) for the scale parameter are, by definition, inherently multivariate, applicable to instances for any dimensionality d. Hierarchical optimization via logarithmic search is the default AD-MGD procedure to ensure robust performance in multidimensional settings (). However, Algorithm 1 includes a specialization to optimize efficiency, as detailed below.

For one-dimensional data sets that have been pre-rescaled to , empirical evidence shows that keeps the graph connected while avoiding excessively small weights, without altering the performance of the evaluated algorithms.

For multidimensional data sets, the optimal scale is determined numerically by a hierarchical strategy: a global logarithmic grid search first evaluates a log-spaced range of values by computing the Shannon entropy of the self-transition probability vector, and the that maximises this entropy serves as the initial estimate, which is then refined locally around this optimum to finalise the parameter that governs the diffusion- matrix connectivity.

The local refinement is then performed in a linear neighborhood centered on this preliminary estimate . The interval is sampled uniformly to capture subtler variations in entropy. The relative width and the sample cardinality define the granularity of this process. In the reported experiments, we set (thus defining a 40% interval centered at ) and uniformly sampled values. If any point within this restricted interval yields an entropy higher than the initial estimate, is updated; otherwise, the global estimate is retained. This hierarchical strategy combines a broad exploration of the search space, which mitigates the risk of undesirable local maxima, with fine optimization near the global peak, thereby ensuring a highly accurate estimate of .

4.4. Representativeness Analysis and Anomaly Detection via Geometric Diffusion

This subsection details the representativeness analysis and anomaly-detection stage of AD-MGD: the algorithm forms a diffusion graph, estimates the scale parameter by maximising Shannon entropy, and isolates anomalous instances by ranking the diagonal entries of the transition matrix.

AD-MGD detects anomalous instances in a data set through geometric diffusion, exploiting the topology of a similarity graph built on the pre-processed instances. The procedure begins by constructing a neighbourhood graph whose edge weights are given by the Gaussian kernel in Equation (8). The normalisation in Equation (2) converts this affinity matrix into the Markov transition matrix P; the term in Equation (3) acts as a normaliser that guarantees each row of P sums to 1, thereby preserving the probabilistic interpretation. The scale parameter is selected by maximising Shannon entropy, as discussed in Section 4.3, ensuring a faithful representation of the intrinsic geometry of the data. The diagonal entries of the transition matrix (, see Equation (9)) quantify the local relevance of each instance. The fundamental logic for anomaly detection is based on geometric connectivity: anomalies, or outliers, are instances located in sparse regions that exhibit weak connectivity to their neighbors. Interpreted as a diffusion process, a virtual particle at will tend to remain at (high ) when local connectivity is low. Conversely, low values indicate strong integration into dense regions, with a high probability of transitioning to neighbors, which is characteristic of normal observations. Thus, large self transition probabilities signal potential anomalies, whereas low values indicate high integration.

AD-MGD detects anomalies by sorting the instances in descending order of their self-transition probabilities, so the most likely outliers appear at the top of the list. Formally, let:

be the vector of ordered indices, where corresponds to the instance with the largest self-transition probability and, consequently, the highest anomaly likelihood.

The method supports two labelling schemes. When the contamination rate is known, the first observations in the ranking, where n is the total number of instances, are labelled as anomalous. If no prior information is available, the algorithm returns the complete anomaly-ordered list, allowing the analyst to inspect instances sequentially until an observation no longer exhibits typical outlier characteristics; that change-of-behaviour point defines the cut-off threshold, which may be validated through domain knowledge or statistical criteria.

Algorithm 1 summarises the entire procedure, from constructing the diffusion graph to generating the ranking of the self-transition probabilities.

It is important to note that the iterative process in Algorithm 1 (lines 6 to 24) does not refer to the convergence of the Markov transition matrix P in terms of stationary states, but rather to a hierarchical and adaptive search for the optimal hyperparameters and .

Including the parameter in the kernel (Equation (8)) allows the local geometry of the graph to be adapted to different data scales. The stability of the process is ensured by Shannon entropy maximization (Equation (10)), which acts as a dynamic regularizer to prevent extreme state persistence (overfitting to fragile dynamics) and to ensure a more stable and generalizable geometric representation. The convergence of this search process is determined by the maximum number of iterations of the k loop (t) and by explicit stopping conditions, for example or , which ensure termination within a bounded computational cost.

4.5. Complexity Analysis

This subsection presents a detailed complexity analysis of the AD-MGD algorithm, highlighting both time and memory costs under different data dimensionalities and comparing them with classical anomaly detection methods.

Let n be the number of instances, d the dimensionality, k the number of neighbors per diffusion, m the cardinality of the global -grid, r the cardinality of the local refinement, the total number of values evaluated per trial, and the maximum number of iterations of the adaptive k-loop. In the code, each trial of k involves a neighbor precomputation followed by the evaluation of c -values on the same distance block.

The neighborhood search mechanism uses brute-force scanning when and a KD-Tree when . For , the algorithm enforces and performs an all-against-all comparison between points; since no relevant indexing stage is needed, the time cost reduces to computing all distances, that is, . Distances can be stored in an matrix, which implies memory usage of . For , with a KD-Tree, the average cost of k-NN precomputation per trial is , while memory to store the k distances per point is ; in high dimensionality, degradation to may occur.

Given the distance block , each value of is evaluated in to compute Gaussian weights and . In each trial of k, the global search with m values and the local refinement with r values totalize . During the global search, the code temporarily maintains a list with m vectors of size n, which produces an additional memory peak of besides ; this peak does not persist outside the function.

Summing the costs per trial of k and considering up to t iterations, the total time for is

with peak memory

For , since the code fixes and evaluates a single , it holds that and . In practice, with moderate , the dominant term in n for is typically from the KD-Tree, resulting in sub-quadratic growth; the AD-MGD-specific step after precomputation scales linearly in .

In qualitative comparison, neighborhood-based methods such as KNN, LOF, and COF also depend on neighbor searches with average costs of and memory ; ABOD tends to be more expensive, while HBOS is linear in n and IForest is nearly linear with subsampling. Thus, the code implements AD-MGD with an average time of per trial and peak memory of for , and costs of in both time and memory in the one-dimensional case.

5. Experimental Evaluation

This section describes the AD-MGD experiments in two complementary stages. In the first stage, synthetic data sets were employed in which the normal instances form complex geometric structures and the anomalies are scattered across multiple regions of the space, providing strict control over both geometry and contamination rate and enabling rigorous validation of the ranking based on the self-transition probabilities and of the scale parameter selected by maximising Shannon entropy. In the second stage, the method was evaluated on four widely used real-world data sets with different dimensionalities and anomaly proportions, assessing its performance under practical conditions.

Quantitative results, including the number of recovered anomalies and the area under the ROC curve (AUC) [19], the most commonly used metric in anomaly detection evaluations [21], are presented in tables. For all comparisons, ROC curves and AUC were computed from the continuous anomaly scores output by each method, in accordance with best practices; no prior binarization of scores was performed. Boxplots of the self-transition probabilities display location, dispersion, skewness, tails and outliers, with anomalies consistently occupying the leading positions (lower percentiles) of the ranking because they exhibit the highest self-transition probabilities, while one-, two- and three-dimensional projections visually contrast normal and anomalous instances.

Given the multitude of anomaly-detection algorithms, choosing the most appropriate technique is far from trivial. To benchmark AD-MGD against classical unsupervised detectors, six representative algorithms spanning the main methodological families highlighted in recent surveys [5] were selected: HBOS [45] (statistical), LOF [46] and COF [47] (density-based), KNN [51] and ABOD [53] (distance-based), and Isolation Forest [55] (isolation-based). All implementations relied on the PyOD library [65] and were configured solely with the nominal contamination rate of each dataset, with no additional hyper-parameter tuning—mirroring real-world conditions and ensuring fair comparability across methods. Although Bouman et al. (2024) [4] report that Extended Isolation Forest excels on global anomalies and KNN on local anomalies, Isolation Forest was retained here as the canonical representative of the isolation family because of its maturity and widespread adoption.

For experimental validation, all compared algorithms were configured with each dataset’s known nominal contamination rate . The “Detected Anomalies” metric reported in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 quantifies the number of true anomalies (true positives) each algorithm identifies when the cutoff threshold is set to the most anomalous points in the ranking. Therefore, a higher value indicates better ranking performance, with the maximum possible value equal to the total number of anomalies in the dataset. AUC, however, remains the primary threshold-independent metric for the overall assessment of discriminatory power and is computed strictly from continuous scores as noted above.

Table 1.

Consolidated results for one-dimensional data.

Table 2.

Consolidated results for two-dimensional data.

Table 3.

Consolidated results for three-dimensional data.

Table 4.

Consolidated results on real data sets.

5.1. Synthetic Data Sets

Experiments on synthetic data were divided into three groups: (i) one-dimensional Gaussian, Beta and Gamma distributions; (ii) five two-dimensional sets with distinct geometries (Ring, Corners, Curves, Spiral and Waves); and (iii) three more complex three-dimensional sets (Helical Curve, 3D Corners and 3D Spiral). For each group we specify the generation process, the anomaly-labelling criterion, the AD-MGD parameters and the metrics used for comparison with the reference methods.

5.1.1. One-Dimensional Synthetic Data

Three one-dimensional sets of 10 000 instances were generated from different statistical distributions: Gaussian, Beta (, ) and Gamma (, ). Anomalies were identified by the Z-score rule (), yielding 23, 34 and 91 outliers, respectively.

Table 1 reports, for these distributions, the number of anomalies detected by each method and the corresponding AUC.

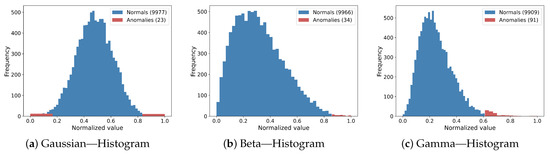

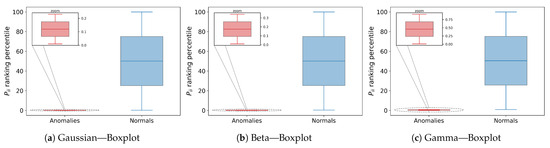

Figure 1 and Figure 2 summarise these results. Figure 1 shows histograms in which anomalous observations (red) lie in the low-density tails of the normal data (blue), evidencing a clear spatial separation irrespective of the distribution shape. Figure 2 displays boxplots of the self-transition rank percentiles: normal data have medians near 50% and wide interquartile ranges, whereas anomalies are compressed into a narrow band near the origin; even after zooming, they do not exceed 1% of the global ranking.

Figure 1.

Histograms of the one-dimensional Gaussian, Beta and Gamma data sets used in the experiments. Blue bars correspond to normal observations, while red bars indicate anomalies.

Figure 2.

Boxplots of the self-transition probability rank percentiles produced by AD-MGD for the Gaussian, Beta, and Gamma data sets. Blue boxes correspond to normal instances and red boxes to anomalies; the zoomed inset highlights the narrow percentile range occupied by anomalous scores.

5.1.2. Two-Dimensional Synthetic Data

Following Aryal et al. [66], five two-dimensional data sets were constructed, namely Ring, Corners, Curves, Waves and Spiral, each containing slightly more than 2000 instances. These sets were designed to emulate different geometric configurations with controlled anomaly rates.

Table 2 summarises, for each data set, the total anomalies recovered and the AUC of the evaluated methods.

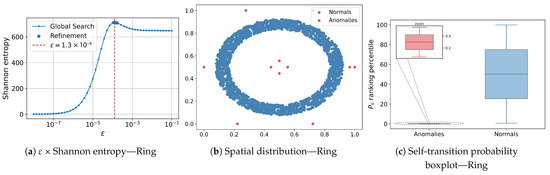

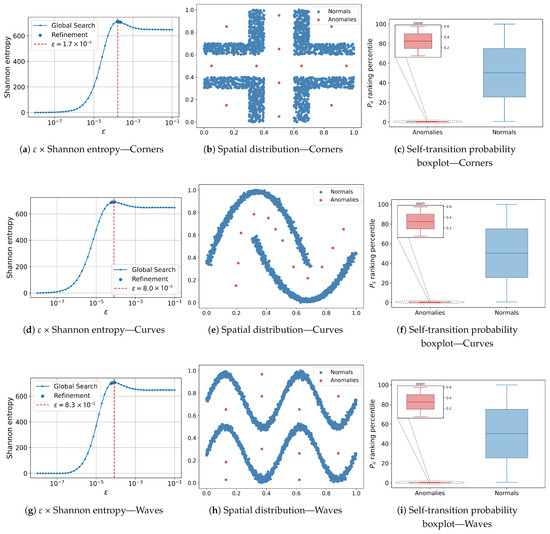

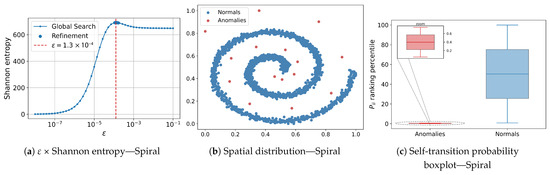

Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5 consolidate the results for the five two-dimensional sets. Each row shows, from left to right: (i) the –Shannon-entropy curve used to select the scale parameter; (ii) the spatial distribution of instances classified by AD-MGD (blue = normal, red = anomaly); and (iii) a boxplot of the self-transition probability rank percentiles, where normal data exhibit a wide interquartile range and a central median, whereas anomalies are compressed into a narrow rectangle near the lower bound; a zoomed inset highlights the low internal variability of the anomalous group.

Figure 3.

Results for the Ring data set. (a) × Shannon-entropy curve used to select the scale parameter; (b) spatial distribution of the instances classified by AD-MGD (blue = normal, red = anomalies); (c) boxplot of the self-transition probability rank percentiles, highlighting the separation between normal (blue) and anomalous (red) observations.

Figure 4.

Results for the three two-dimensional synthetic datasets. Rows correspond, from top to bottom, to Corners, Curves, and Waves. For each dataset, (a,d,g) show the × Shannon-entropy curve used to select the scale parameter; (b,e,h) display the spatial distribution of instances classified by AD-MGD (blue = normal, red = anomalies); (c,f,i) present boxplots of the self-transition probability rank percentiles, highlighting the separation between normal (blue) and anomalous (red) observations.

Figure 5.

Results for the two-dimensional Spiral dataset. (a) × Shannon-entropy curve used to select the scale parameter; (b) spatial distribution of instances classified by AD-MGD (blue = normal, red = anomalies); (c) boxplot of the self-transition probability rank percentiles, highlighting the separation between normal (blue) and anomalous (red) observations.

5.1.3. Three-Dimensional Synthetic Data

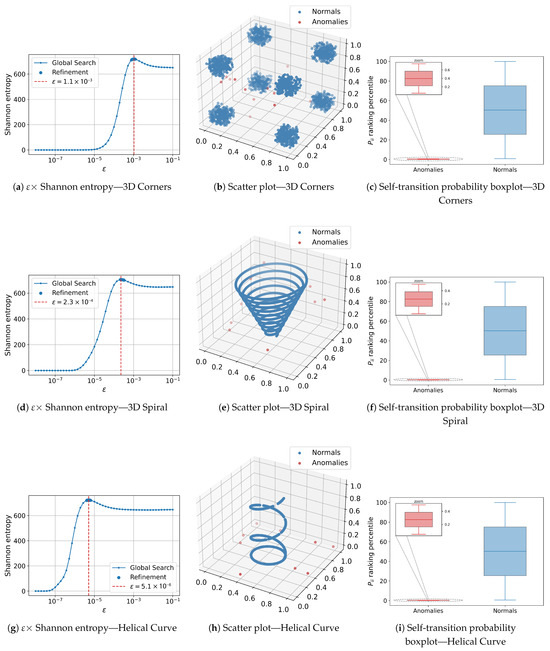

To emulate scenarios with greater spatial complexity, three three-dimensional data sets were generated: Helical Curve, 3D Corners and 3D Spiral, each containing slightly more than 2000 instances with known outlier proportions.

Table 3 lists the total anomalies identified and the corresponding AUC.

Figure 6 compiles the AD-MGD results for the three-dimensional datasets. Each row shows, from left to right: (i) the –Shannon-entropy curve used to select the scale parameter; (ii) the 3-D scatter plot coloured by the AD-MGD classification (blue = normal, red = anomalies); and (iii) the boxplot of the self-transition-probability rank percentiles, where normal data exhibit a wide interquartile range and a central median, whereas anomalies are compressed into a narrow band near the lower bound; a zoomed inset highlights the low internal variability of the anomalous group.

Figure 6.

Results for the three synthetic three-dimensional datasets. Rows correspond, from top to bottom, to 3D Corners, 3D Spiral, and Helical Curve. For each dataset, (a,d,g) show the × Shannon-entropy curve used to select the scale parameter; (b,e,h) display the three-dimensional scatter plots of the instances classified by AD-MGD (blue = normal, red = anomalies); (c,f,i) present the boxplots of the self-transition-probability rank percentiles, contrasting the variability of normal data with the narrow band occupied by anomalous scores.

5.2. Real Data

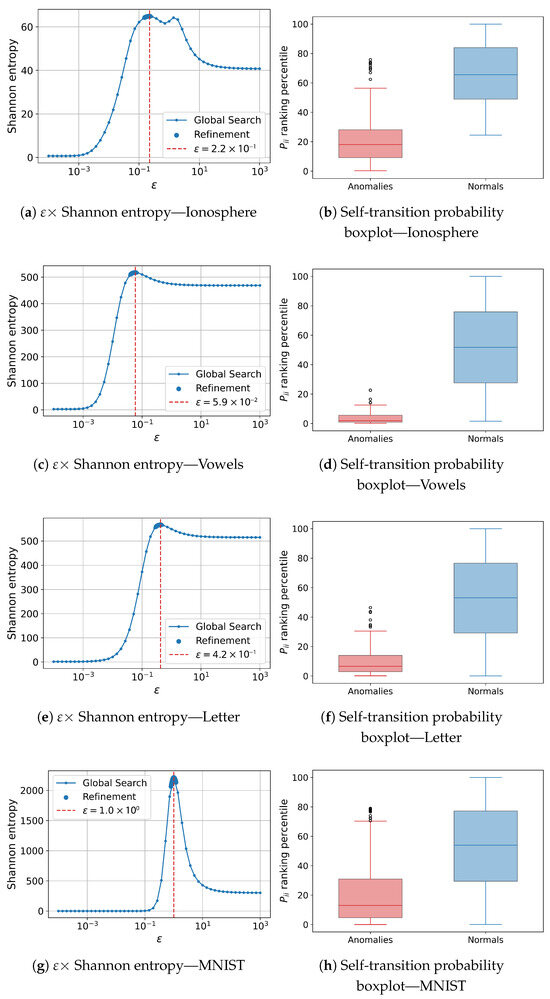

This subsection evaluates the performance of AD-MGD on real-world datasets selected to cover a broad spectrum of sizes, dimensionalities, and contamination rates, verifying whether the robustness observed on synthetic data is maintained in practical and heterogeneous scenarios. Four datasets from the ODDS collection [67] were used: Ionosphere (351 instances, 33 attributes, 35.9% anomalies) [68]; Vowels (1456 instances, 12 attributes, 3.4%) [69,70,71]; Letter (1600 instances, 32 attributes, 6.3%) [67,72,73]; and MNIST (7603 instances, 100 attributes, 9.2%) [74,75]. Most of these datasets originate from the UCI Machine Learning Repository [76], except for MNIST.

Although the original ODDS repository (https://odds.cs.stonybrook.edu/), accessed on 3 September 2024) is currently unavailable, the author [67] maintains a personal webpage with the datasets used in this work (https://shebuti.com/outlier-detection-datasets-odds/), accessed on 22 August 2025). In parallel, the anomaly-detection research community has increasingly adopted the PyOD [65] and ADBench [77] suites, which provide standardized and preprocessed versions of datasets from UCI, OpenML, and additional collections focused on computer vision, text processing, and time series.

In this study, known contamination rates were employed to facilitate the presentation of results and to validate proper anomaly detection, ensuring that the experimental protocol remains directly comparable to those reported in the literature. The results obtained by AD-MGD are presented below.

Table 4 consolidates, for each data set, the number of anomalies recovered and the AUC obtained by AD-MGD and the comparative methods.

Figure 7 gathers the AD-MGD results for the real-world datasets listed above. Each row shows, in sequence: (a) the × Shannon-entropy curve whose maximum defines the scale parameter; and (b) the boxplot of the self-transition probability ranking positions, which highlights the systematic shift of anomalous scores toward lower percentiles, reinforcing the algorithm’s discriminative power.

Figure 7.

AD-MGD results on the four real datasets. Rows correspond, from top to bottom, to Ionosphere, Vowels, Letter, and MNIST. For each dataset, panels (a,c,e,g) show the × Shannon-entropy curve used to select the scale parameter; panels (b,d,f,h) show the boxplot of the self-transition probability rank percentiles, contrasting normal data (blue) with anomalies (red).

6. Discussion

This section consolidates and interprets the experimental findings, comparing AD-MGD with reference methods by means of the area under the ROC curve (AUC). We first examine one-, two- and three-dimensional synthetic scenarios, highlighting the influence of data geometry on the observed performance. Next, we discuss the tests on real data sets, emphasising the contribution of automatically selecting the scale parameter via Shannon-entropy maximisation. Finally, we analyse the limitations observed in high dimensionality and scalability, and, in Section 6.3, outline research directions aimed at improving efficiency, adaptability, and interpretability.

The experiments showed that AD-MGD delivered consistent performance across synthetic and real data. AUC was adopted as the main metric because it objectively reflects the ability to discriminate between normal and anomalous instances. On synthetic data, the method achieved AUC for all one-, two- and three-dimensional distributions, matching or surpassing the other algorithms. Overall, AD-MGD attains perfect separation across all synthetic sets, while histogram- and tree-based baselines degrade on curved manifolds.

On the real data sets, AD-MGD reached AUC on Ionosphere (best overall; next best k-NN ), on Vowels (second best, closely trailing k-NN at and ahead of ABOD ), and on Letter (best overall). On the higher-dimensional MNIST set, AD-MGD obtained AUC , outperforming IForest () and k-NN (). These results indicate that the method keeps a consistent edge over the evaluated alternatives, while the small gaps on MNIST suggest room for further gains through tuning or hybridisation with complementary techniques.

Regarding scalability, high dimensionality remains challenging. Although our implementation mitigates the naive cost of constructing full pairwise-distance matrices by reusing k-NN neighbourhoods, further advances (for example, batching, and distributed computation) are promising directions to improve efficiency without sacrificing detection quality.

6.1. Synthetic Data

This subsection examines the experiments on one-, two-, and three-dimensional synthetic data, relating geometry to AUC and anomaly-detection rate, characterising the performance of AD-MGD and identifying limitations of the comparative methods.

6.1.1. One-Dimensional Synthetic Data

On the one-dimensional sets, AD-MGD detected of the anomalies in the Gaussian, Beta, and Gamma distributions, achieving a perfect AUC in every case. Isolation Forest also performed very strongly (AUC on Gaussian, on Beta, and on Gamma). Among the remaining detectors, AUCs ranged from high to moderate: kNN (≈99.85–99.99%), HBOS (up to ), ABOD (up to ), while LOF ( on Beta; on Gamma) and COF ( on Beta; on Gamma) degraded on Gamma, with COF identifying only 6 of the 91 anomalies there. The Markov transition matrices used by AD-MGD capture both local and global relationships, contributing to the observed separation between normal and anomalous classes, as illustrated by the histograms in Figure 1.

6.1.2. Two-Dimensional Synthetic Data

Across all two-dimensional sets Ring, Corners, Curves, Waves, Spiral, AD-MGD attained AUC , perfectly identifying the expected anomalies. Neighbourhood-based methods (kNN, LOF, COF, ABOD) matched this result with AUC in every set. Histogram- and tree-based baselines showed geometry-dependent drops: HBOS reached on Corners, but fell to on Curves, on Waves, and on Spiral; IForest scored on Ring, on Curves, on Waves, and on Spiral. These results reinforce AD-MGD’s robustness on diverse non-linear geometries, while highlighting the sensitivity of histogram- and tree-based approaches to curved manifolds.

6.1.3. Three-Dimensional Synthetic Data

In three dimensions, AD-MGD kept AUC across all benchmarks (3D Corners, 3D Spiral, Helical Curve). Neighbourhood-based algorithms (kNN, LOF, ABOD) and COF also achieved AUC on 3D Spiral and Helical Curve; on 3D Corners, COF remained near-perfect (AUC ). HBOS reached on 3D Corners and Helical Curve, and on 3D Spiral. IForest showed small but consistent gaps (AUC on 3D Corners, on 3D Spiral, and on Helical Curve). Thus, AD-MGD maintains maximal performance even on geometrically complex 3D structures, while tree-based methods exhibit mild degradations.

6.2. Real Data

This subsection discusses the results obtained with real data, assessing how AD-MGD compares to baseline methods in terms of AUC, dimensionality, anomaly proportion, and the impact of choosing via Shannon Entropy.

Across the four real-world datasets (Ionosphere, Vowels, Letter, and MNIST), AD-MGD ranked among the top performers in all experiments. Its AUC values were on Ionosphere (best overall; next best k-NN at ), on Vowels (second place, very close to k-NN at and ahead of ABOD at ), on Letter (best overall), and on MNIST (best overall, ahead of IForest at and k-NN at ).

The key to these results lies in the automatic selection of the scale parameter . Choosing by maximizing Shannon Entropy consistently placed outliers at the top of the self-transition probability ranking, which explains the high detection rates illustrated by the boxplots.

However, the comparatively smaller margins on high-dimensional datasets such as MNIST and Letter suggest sensitivity to the curse of dimensionality, a common challenge for distance- and density-based methods.

Performance in high-dimensional settings and computational complexity are intrinsically linked to scalability considerations. As discussed in Section 4.5, the worst-case cost of building a full pairwise-distance matrix can reach in time and memory. Our implementation mitigates this by reusing k-NN neighborhoods and their distances across the grid and the local refinement, yielding an overall cost of approximately time and memory for the search over c candidates. Even so, further improvements using batching, and distributed computation remain promising to better handle very large and high-dimensional datasets.

To mitigate performance drops in high-dimensional scenarios, future extensions of AD-MGD should incorporate non-linear dimensionality reduction or feature selection. These strategies can reduce noise and redundancy in high-dimensional spaces, alleviate the curse of dimensionality, and improve discrimination, thereby increasing AUC.

6.3. Limitations and Future Work

AD-MGD was effective across the evaluated scenarios, but margins narrow in high dimensionality. On MNIST, the AUC reached 83.23% and remained close to IForest (82.41%) and k-NN (80.41%), which is consistent with the influence of the curse of dimensionality on distance- and density-based methods. From a computational standpoint, the procedure operates in two regimes, in accordance with Section 4.5. For , it fixes and evaluates a single , with time and memory . For , it reuses the same k-NN distances across the global grid and the local refinement, yielding an average per-trial time of and peak memory , with possible degradation toward as d grows.

Future research may explore approximate neighbors such as HNSW (Hierarchical Navigable Small World [78], a hierarchical small-world graph for approximate nearest-neighbor search) and product quantization [79] to reduce the cost of the k-NN stage and its dependence on d. It is also promising to compute in blocks or in a streaming manner, eliminating the transient peak during the global search over , as well as to employ batching on GPUs (Graphics Processing Units) and distributed execution to handle very large, high-dimensional datasets. Another avenue is to develop an online variant with incremental updates of and neighborhoods, enabling real-time detection on data streams. On the algorithmic side, investigating non-linear dimensionality reduction and feature selection could mitigate noise and redundancy in high-dimensional spaces, and a meta-learning scheme that automatically chooses the most suitable information criterion—comparing Shannon entropy with alternatives—may enhance robustness across domains. As an extension, we plan to formalize a measure of anomaly severity, for example by modulating with neighborhood properties such as or local graph structure, in order to distinguish isolated points from small anomalous clusters.

Finally, combining multiple kernels in diffusion ensembles and incorporating interpretability modules, including vertex-level importance scores and graph visualizations, can improve both accuracy and transparency in critical applications.

7. Conclusions

AD-MGD proved effective in anomaly detection by combining Markovian Geometric Diffusion with automatic scale selection via Shannon entropy. On synthetic one-, two-, and three-dimensional datasets, it achieved AUC across all geometries—including rings, corners, curves, waves, spirals, and helices—demonstrating reliable separation even on non-linear manifolds. On real datasets, AD-MGD ranked among the top methods in every case and was best overall on three out of four benchmarks: Ionosphere (AUC , next best k-NN ), Vowels (, narrowly behind k-NN at and ahead of ABOD at ), Letter (, best overall), and MNIST (, best overall, ahead of IForest and k-NN ). As detailed in Section 5, these results yield the highest average AUC among the compared methods.

Its chief strength is capturing multi-dimensional structure in an unsupervised way, stabilising via a global logarithmic grid followed by local refinement. This procedure removes manual tuning and produces consistent outlier rankings through self-transition probabilities, as illustrated by the boxplots and spatial visualisations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.C.R., L.C.d.S. and G.H.M.B.M.; methodology, E.C.R., L.C.d.S. and G.H.M.B.M.; software, E.C.R.; validation, E.C.R., L.C.d.S. and G.H.M.B.M.; formal analysis, E.C.R., L.C.d.S. and G.H.M.B.M.; investigation, E.C.R., L.C.d.S. and G.H.M.B.M.; resources, E.C.R.; data curation, E.C.R.; writing—original draft preparation, E.C.R.; writing—review and editing, E.C.R., L.C.d.S. and G.H.M.B.M.; visualization, E.C.R.; supervision, L.C.d.S. and G.H.M.B.M.; project administration, E.C.R., L.C.d.S. and G.H.M.B.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sources used in this work were referenced throughout the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the editor and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABOD | Angle-Based Outlier Detection |

| AD-MGD | Anomaly Detection Based on Markovian Geometric Diffusion |

| ADBench | Anomaly Detection Benchmarks |

| AEKNN | AutoEncoder K-NN |

| AUC | Area Under the ROC Curve |

| BEWS | Biological Early Warning Systems |

| COF | Connectivity-Based Outlier Factor |

| DMs | Diffusion Models |

| DMT | Diffusion Maps Theory |

| e-MGD | Extended Markovian Geometric Diffusion |

| EIF | Extended Isolation Forest |

| GAN(s) | Generative Adversarial Network(s) |

| GPU(s) | Graphics Processing Unit(s) |

| HBOS | Histogram-Based Outlier Score |

| HNSW | Hierarchical Navigable Small World |

| IForest | Isolation Forest |

| KDD | Knowledge Discovery in Databases |

| k-d tree | k-dimensional tree (KD-tree) |

| k-NN | k-Nearest Neighbors |

| kth-NN | kth Nearest Neighbor |

| LOCI | Local Correlation Integral |

| LOF | Local Outlier Factor |

| LoOP | Local Outlier Probability |

| MGD | Markovian Geometric Diffusion |

| ODDS | Outlier Detection DataSets |

| OOSE | Out-of-Sample Extension |

| PyOD | Python Outlier Detection |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| SECODA | Segmentation-and Combination-based Detection of Anomalies |

| UCI | University of California, Irvine (Machine Learning Repository) |

References

- Souza, R.A.S.d. Um Sistema de Apoio à Detecção de Anomalias em Dados Governamentais usando Múltiplos Classificadores. Master’s Thesis, Federal University of Paraíba (UFPB), Paraíba, Brazil, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fayyad, U.; Piatetsky-Shapiro, G.; Smyth, P. From Data Mining to Knowledge Discovery in Databases. AI Mag. 1996, 17, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandola, V.; Banerjee, A.; Kumar, V. Outlier Detection: A Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2007, 14, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Bouman, R.; Bukhsh, Z.; Heskes, T. Unsupervised Anomaly Detection Algorithms on Real-world Data: How Many Do We Need? J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2024, 25, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Samariya, D.; Thakkar, A. A Comprehensive Survey of Anomaly Detection Algorithms. Ann. Data Sci. 2023, 10, 829–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grekov, A.N.; Kabanov, A.A.; Vyshkvarkova, E.V.; Trusevich, V.V. Anomaly detection in biological early warning systems using unsupervised machine learning. Sensors 2023, 23, 2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, J.; Qian, R.; Yuan, J.; Ren, Y. An anomaly detection method for wireless sensor networks based on the improved isolation forest. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Guo, J.; Wang, Y.; Xu, W.; Bao, Y.; He, J.; Zhang, Y. Automated seismic event detection considering faulty data interference using deep learning and Bayesian fusion. Comput. Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2025, 40, 1910–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, G.; Tang, Z.; Guo, J.; Huang, X.; Zhang, C.; Xu, W. Consistent Seismic Event Detection Using Multi-Input End-to-End Neural Networks for Structural Health Monitoring. Struct. Control Health Monit. 2025, 2025, 9966359. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Huang, X.; Xu, W. Nonuniform data loss reconstruction based on time-series-specialized neural networks for structural health monitoring. Struct. Health Monit. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, S.; Gao, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Wan, X.; Hu, W.; Jiang, X. MST: Multiscale Flow-Based Student–Teacher Network for Unsupervised Anomaly Detection. Electronics 2024, 13, 3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhosale, A.; Mukherjee, S.; Banerjee, B.; Cuzzolin, F. Anomaly Detection Using Diffusion-Based Methods. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Yang, Y. Anomaly detection in machining centers based on graph diffusion-hierarchical neighbor aggregation networks. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bercea, C.I.; Wiestler, B.; Rueckert, D.; Schnabel, J.A. Diffusion Models with Implicit Guidance for Medical Anomaly Detection. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention—MICCAI, Marrakesh, Morocco, 6–10 October 2024; Linguraru, M.G., Dou, Q., Feragen, A., Giannarou, S., Glocker, B., Lekadir, K., Schnabel, J.A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, F.M.; Souza, P.; de Magalhães, M.S. Determining Baseline Profile by Diffusion Maps. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2019, 279, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Dong, R.; Wang, J.; Xia, M. Credit card fraud detection based on unsupervised attentional anomaly detection network. Systems 2023, 11, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, L.C.d. Simplificação de Malhas com Preservação de Feições baseada em Difusão Geométrica Markoviana. Master’s Thesis, Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (PUC-Rio), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, C.E. A Mathematical Theory of Communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawcett, T. An Introduction to ROC Analysis. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2006, 27, 861–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, M.; Uchida, S. A Comparative Evaluation of Unsupervised Anomaly Detection Algorithms for Multivariate Data. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues, R.; Filippone, M.; Michiardi, P.; Zouaoui, J. A Comparative Evaluation of Outlier Detection Algorithms: Experiments and Analyses. Pattern Recognit. 2018, 74, 406–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, G.O.; Zimek, A.; Sander, J.; Campello, R.J.G.B.; Micenková, B.; Schubert, E.; Assent, I.; Houle, M.E. On the Evaluation of Unsupervised Outlier Detection: Measures, Datasets, and an Empirical Study. Data Min. Knowl. Disc. 2016, 30, 891–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, G.; Shen, C.; Cao, L.; Hengel, A.V.D. Deep Learning for Anomaly Detection: A Review. ACM Comput. Surv. 2021, 54, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamanzadeh Darban, Z.; Webb, G.I.; Pan, S.; Aggarwal, C.; Salehi, M. Deep Learning for Time Series Anomaly Detection: A Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 57, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coifman, R.R.; Lafon, S. Diffusion Maps. Appl. Comput. Harmon. Anal. 2006, 21, 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkin, M.; Niyogi, P. Laplacian eigenmaps for dimensionality reduction and data representation. Neural Comput. 2003, 15, 1373–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipola, T.; Juvonen, A.; Lehtonen, J. Anomaly Detection from Network Logs using Diffusion Maps. In Engineering Applications of Neural Networks; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 363, pp. 172–181. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, R.; Wunsch II, D.; Du, K.; Xu, Y.; Shaefer, J.M. Applications of Diffusion Maps in Gene Expression Data-Based Cancer Diagnosis Analysis. In Proceedings of the 29th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, Lyon, France, 22–26 August 2007; pp. 2200–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirotori, M.; Sugitani, Y. Change-point detection using diffusion maps for sleep apnea monitoring with contact-free sensors. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0306139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, X. Diffusion maps based k-nearest-neighbor rule technique for semiconductor manufacturing process fault detection. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2014, 136, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zang, C. Discriminant Diffusion Maps Based K-Nearest-Neighbour for Batch Process Fault Detection. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2018, 96, 484–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, C.C.; Judd, K.P.; Nichols, J.M. Manifold Learning Techniques for Unsupervised Anomaly Detection. Expert Syst. Appl. 2017, 91, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishne, G.; Shaham, U.; Cloninger, A.; Cohen, I. Diffusion Nets. Appl. Comput. Harmon. Anal. 2017, 91, 259–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishne, G.; Cohen, I. Iterative Diffusion-Based Anomaly Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), New Orleans, LA, USA, 5–9 March 2017; pp. 2337–2341. [Google Scholar]

- Mishne, G.; Cohen, I. Multi-Channel Wafer Defect Detection Using Diffusion Maps. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Quebec City, QC, Canada, 27–30 September 2015; pp. 1740–1744. [Google Scholar]

- Mishne, G.; Cohen, I. Multiscale Anomaly Detection Using Diffusion Maps. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 2013, 7, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishne, G.; Cohen, I. Multiscale anomaly detection using diffusion maps and saliency score. In Proceedings of the 39th IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Florence, Italy, 4–9 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Juvonen, A.; Hämäläinen, T. An efficient network log anomaly detection system using random projection dimensionality reduction. In Proceedings of the 2014 6th International Conference on New Technologies, Mobility and Security (NTMS), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 30 March–2 April 2014; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, J.; Jain, A.; Abbeel, P. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Virtual, 6–12 December 2020; Volume 33, pp. 6840–6851. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K.; Yu, H.; Yan, Y.; Hu, Z.; Rajak, P.; Weerasinghe, A.; Boz, O.; Chakrabarti, D.; Wang, F. Graph diffusion models for anomaly detection. In Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2024, Singapore, 13–17 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Zeng, D.; Wu, Z.; Jiang, Y.G. DiffusionAD: Norm-Guided One-Step Denoising Diffusion for Anomaly Detection. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2025, 47, 7140–7152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Zhang, J.; Chen, H.; Chen, X.; Li, Z.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Xie, L. DiAD: A Diffusion-based Framework for Multi-class Anomaly Detection. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.06607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrieta, A.B.; Díaz-Rodríguez, N.; Del Ser, J.; Bennetot, A.; Tabik, S.; Barbado, A.; García, S.; Gil-López, S.; Molina, D.; Benjamins, R.; et al. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI): Concepts, taxonomies, opportunities and challenges toward responsible AI. Inf. Fusion 2020, 58, 82–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, M.; Dengel, A. Histogram-Based Outlier Score (HBOS): A Fast Unsupervised Anomaly Detection Algorithm; DFKI: Kaiserslautern, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Breunig, M.M.; Kriegel, H.P.; Ng, R.T.; Sander, J. LOF: Identifying Density-Based Local Outliers. In Proceedings of the 2000 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data, Dallas, TX, USA, 16–18 May 2000; pp. 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J.; Chen, Z.; Fu, A.W.c.; Cheung, D.W. Enhancing Effectiveness of Outlier Detections for Low Density Patterns. In Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; Chen, M.S., Yu, P.S., Liu, B., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; pp. 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriegel, H.P.; Kröger, P.; Schubert, E.; Zimek, A. LoOP: Local Outlier Probabilities. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Hong Kong, China, 2–6 November 2009; pp. 1649–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, S.; Kitagawa, H.; Gibbons, P.; Faloutsos, C. LOCI: Fast Outlier Detection Using the Local Correlation Integral. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Data Engineering (Cat. No.03CH37405), Bangalore, India, 5–8 March 2003; pp. 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, E.M.; Ng, R.T. Algorithms for Mining Distance-Based Outliers in Large Datasets. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Very Large Data Bases. Citeseer, New York, NY, USA, 24–27 August 1998; pp. 392–403. [Google Scholar]

- Knorr, E.M.; Ng, R.T.; Tucakov, V. Distance-Based Outliers: Algorithms and Applications. VLDB J. 2000, 8, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy, S.; Rastogi, R.; Shim, K. Efficient Algorithms for Mining Outliers from Large Data Sets. In Proceedings of the 2000 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data, Dallas, TX, USA, 16–18 May 2000; pp. 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriegel, H.P.; Schubert, M.; Zimek, A. Angle-Based Outlier Detection in High-Dimensional Data. In Proceedings of the 14th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 24–27 August 2008; pp. 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Hutter, M.; Jin, H. A New Local Distance-Based Outlier Detection Approach for Scattered Real-World Data. In Advances in Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; Theeramunkong, T., Kijsirikul, B., Cercone, N., Ho, T.B., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.T.; Ting, K.M.; Zhou, Z.H. Isolation Forest. In Proceedings of the 2008 Eighth IEEE International Conference on Data Mining, Pisa, Italy, 15–19 December 2008; pp. 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Liu, G.; Zuo, Y.; Wu, J. An Anomaly Detection Framework Based on Autoencoder and Nearest Neighbor. In Proceedings of the 2018 15th International Conference on Service Systems and Service Management (ICSSSM), Hangzhou, China, 21–22 July 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foorthuis, R. SECODA: Segmentation- and Combination-Based Detection of Anomalies. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Data Science and Advanced Analytics (DSAA), Tokyo, Japan, 19–21 October 2017; pp. 755–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.A.N.S.; Souza, L.C.; Motta, G.H.M.B. An Instance Selection Method for Large Datasets Based on Markov Geometric Diffusion. Data Knowl. Eng. 2016, 101, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bah, B. Diffusion Maps: Analysis and Applications. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Belkin, M.; Niyogi, P. Convergence of Laplacian Eigenmaps. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006; Volume 19. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, A.J.; Wielandt, H.W. The Variation of the Spectrum of a Normal Matrix. Duke Math. J. 1953, 20, 37–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayalakshmi, T.; Santhakumaran, A. Statistical Normalization and Back Propagation for Classification. Int. J. Comput. Theory Eng. 2011, 3, 1793–8201. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, A.W. An Introductory Tutorial on KD-Trees; Technical Report No. 209; Computer Laboratory, University of Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 1991; Available online: https://www.ri.cmu.edu/pub_files/pub1/moore_andrew_1991_1/moore_andrew_1991_1.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2023).

- Singer, A.; Wu, H.T. Orientability and Diffusion Maps. Appl. Comput. Harmon. Anal. 2011, 31, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Zhao, Y.; Nasrullah, Z.; Li, Z. PyOD: A Python Toolbox for Scalable Outlier Detection. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2019, 20, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Aryal, S.; Santosh, K.; Dazeley, R. usfAD: A Robust Anomaly Detector Based on Unsupervised Stochastic Forest. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cyber. 2021, 12, 1137–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayana, S.; Akoglu, L. Less Is More: Building Selective Anomaly Ensembles. ACM Trans. Knowl. Discov. Data 2016, 10, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigillito, V.; Wing, S.; Hutton, L.; Baker, K. Ionosphere. 1989. Available online: https://archive.ics.uci.edu/dataset/52/ionosphere (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Kudo, M.; Toyama, J.; Shimbo, M. Japanese Vowels. 1999. Available online: https://archive.ics.uci.edu/dataset/128/japanese+vowels (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Aggarwal, C.C.; Sathe, S. Theoretical Foundations and Algorithms for Outlier Ensembles. SIGKDD Explor. Newsl. 2015, 17, 24–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathe, S.; Aggarwal, C. LODES: Local Density Meets Spectral Outlier Detection. In Proceedings of the 2016 SIAM International Conference on Data Mining, Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, Miami, FL, USA, 5–7 May 2016; pp. 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slate, D. Letter Recognition. 1991. Available online: https://archive.ics.uci.edu/dataset/59/letter+recognition (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Micenková, B.; McWilliams, B.; Assent, I. Learning Outlier Ensembles: ACM SIGKDD 2014 Workshop ODD2; Aarhus University: Aarhus Centrum, Denmark, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lecun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-Based Learning Applied to Document Recognition. Proc. IEEE 1998, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandaragoda, T.R.; Ting, K.M.; Albrecht, D.; Liu, F.T.; Wells, J.R. Efficient Anomaly Detection by Isolation Using Nearest Neighbour Ensemble. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining Workshop, Shenzhen, China, 14 December 2014; pp. 698–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M.; Longjohn, R.; Nottingham, K. The UCI Machine Learning Repository. Available online: https://archive.ics.uci.edu/ (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Han, S.; Hu, X.; Huang, H.; Jiang, M.; Zhao, Y. ADBench: Anomaly Detection Benchmark. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 32142–32159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkov, Y.A.; Yashunin, D.A. Efficient and robust approximate nearest neighbor search using hierarchical navigable small world graphs. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2018, 42, 824–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jegou, H.; Douze, M.; Schmid, C. Product quantization for nearest neighbor search. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2010, 33, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).