Abstract

In this study, medium- and high-entropy carbide systems with compositions WC-TiC-TaC-HfC and WC-TiC-TaC-HfC-ZrC were successfully synthesized via a combination of mechanical activation (using high-energy ball milling, HEBM) and spark plasma sintering (SPS) at 1900 °C. Investigation of the SPS consolidation kinetics revealed that both systems undergo single-stage active densification via a solid-state sintering mechanism within the temperature range of 1316–1825 °C. The introduction of ZrC into the five-component system led to a 22% decrease in the maximum shrinkage rate (from 0.9 to 0.7 mm·min−1), which is attributed to the manifestation of a sluggish diffusion effect, characteristic of high-entropy systems. X-ray diffraction analysis of the consolidated samples confirmed the formation of predominantly single-phase high-entropy solid solutions (W-Ti-Ta-Hf)C and (W-Ti-Ta-Hf-Zr)C with a NaCl-type cubic structure (space group Fm-3m) and lattice parameters of 4.4101 Å and 4.4604 Å, respectively. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy revealed a near-equimolar distribution of metallic components with deviations not exceeding ±1.9 at. %. The addition of ZrC increased the average crystallite size by 84.3% (from 83.6 to 153.1 nm). Both systems achieved comparable relative densities of ~91.75%; however, they exhibited differences in hardness distribution: the four-component system is characterized by a higher average microhardness (1860 HV), while the five-component system exhibits a higher macrohardness HV30 (2008.1). The established correlations between composition, phase formation, microstructure, and properties provide a fundamental basis for the targeted design of high-entropy carbide ceramics with tailored characteristics for high-temperature applications.

1. Introduction

Materials science is characterized by a continuous pursuit of novel functional materials with a unique combination of properties that surpass those of conventional counterparts. One of the most promising research directions of the last two decades is the development and investigation of high-entropy materials [,,], a concept based on a fundamentally new approach to designing multicomponent systems. Within this class of materials, high-entropy ceramics (HECs) have attracted significant attention as the ceramic analogue of high-entropy alloys (HEAs). Despite the relatively recent emergence of interest in HECs, experimental studies demonstrate their outstanding characteristics [,,]: high hardness values [,,]; exceptional thermal stability above 2000 °C [,]; an excellent combination of mechanical properties with unique optical [,], electrical [,], and magnetic [,,] characteristics; and oxidation resistance [,,] significantly exceeding that of individual metal carbides and borides [,]. Owing to this set of properties, HECs are successfully finding applications in the energy [,] and aerospace industries, and are used as high-temperature thermal insulators [,,], catalysts [,], structural materials for nuclear reactors [,], and thermionic devices [,].

A fundamental characteristic of HECs is the formation of a thermodynamically stable single-phase substitutional solid solution, typically with a face-centered cubic (FCC) or body-centered cubic (BCC) lattice []. Unlike traditional ceramic materials composed of one or two principal components, high-entropy systems contain at least five elements or compounds in equimolar or near-equimolar concentrations (5–35 at. %), forming simple crystal structures []. Alongside high-entropy materials, systems with a medium configurational entropy, containing 3–4 components [], are actively studied, representing an intermediate class between traditional and high-entropy systems. The multicomponent nature of HECs enables the development of a wide range of materials with novel, unique combinations of physical and chemical properties by varying the type and ratio of constituent components [].

The thermodynamic stability of high-entropy systems is determined by the entropy value, which comprises four components: configurational mixing entropy, lattice vibrational entropy, electronic entropy, and magnetic entropy []. The most significant contribution comes from the configurational mixing entropy, which increases sharply with the number of system components []. However, it is necessary to consider that maximizing the mixing entropy does not necessarily lead to minimization of the system’s Gibbs free energy (ΔG = ΔH − TΔS), since the enthalpy contribution ΔH, associated with differences in atomic radii, electronegativities, and types of chemical bonds of the components, can destabilize the single-phase state []. Consequently, increasing the number of components can lead to the formation of undesirable secondary phases and intermetallic compounds, making a well-founded choice of both the type of components and their ratio critically important. In most cases, equiatomic or near-equiatomic compositions are used to achieve an optimal balance between entropic and enthalpic contributions [].

A high configurational mixing entropy provides the so-called entropic stabilization of the solid solution, which promotes the formation of a disordered substitutional solution while suppressing the formation of thermodynamically competing intermediate compounds and ordered phases [,,]. The concept of entropic stabilization, originally developed for metallic high-entropy alloys, is successfully applied to ceramic systems [], where it ensures not only the formation of a single-phase structure but also outstanding functional characteristics. Entropic stabilization imparts high mechanical properties, enhanced thermodynamic stability even at temperatures above 2000 °C and under high pressure, as well as resistance to chemically aggressive environments and extreme operating conditions to ceramic solid solutions [,,,,,,]. In addition to the entropic stabilization effect, the properties of HECs are determined by four fundamental effects, first formulated by Yeh: the high-entropy effect, the sluggish diffusion effect, the severe lattice distortion effect, and the cocktail effect, which describes the synergistic interaction of multiple elements within a common lattice [].

The classification of materials as medium- or high-entropy is based on the magnitude of the configurational entropy of mixing. For an ideal equimolar solid solution, the configurational entropy can be calculated using the Boltzmann equation: ΔSconf = R·ln(n), where R is the universal gas constant (8.314 J/(mol·K)), and n is the number of principal components. According to established classification criteria, materials with ΔSconf ≥ 1.5R (~12.5 J/(mol·K)) are considered high-entropy materials. For the four-component WC-TiC-TaC-HfC system, the configurational entropy is ΔSconf = R·ln(4) = 11.53 J/(mol·K) (1.39R), which classifies it as a medium-entropy system. The five-component WC-TiC-TaC-HfC-ZrC system exhibits ΔSconf = R·ln(5) = 13.38 J/(mol·K) (1.61R), exceeding the high-entropy threshold and confirming its classification as a high-entropy material. This distinction is important, as the increased configurational entropy in the five-component system is expected to enhance thermodynamic stability and influence diffusion kinetics, microstructure evolution, and mechanical properties.

Among various types of high-entropy ceramics, systems based on carbides of group IV and V transition metals (Ti, Zr, Hf, V, Nb, Ta) are of particular interest for fundamental research and applied solutions, as these compounds possess excellent mechanical characteristics, high hardness (20–30 GPa), and superior resistance to oxidation, corrosion, and wear [,]. The crystal structure of refractory metal carbides is determined by strong covalent M-C bonds with a partial contribution of metallic bonding [], which ensures extremely high melting points (2870–3959 °C for WC-HfC) [] and low cationic diffusivity even at temperatures of 0.5–0.7 of the melting point []. Most group IV-V transition metal carbides crystallize in the NaCl-type cubic structure (space group Fm-3m), creating favorable conditions for the formation of continuous substitutional solid solutions in the cation sublattice while preserving the carbon sublattice. Despite the growing research interest in multicomponent solid solutions based on metal carbides, fundamental questions concerning phase formation mechanisms, the sequence of phase transformations upon heating, and the influence of composition on consolidation kinetics remain open []. Understanding the patterns of phase transformations in entropy-stabilized solid solutions is critical for establishing “composition-structure-property” relationships and the targeted design of high-entropy carbides with a predetermined set of characteristics.

A key factor for the successful synthesis of high-entropy carbides is the selection of a consolidation method for powder precursors. One of the most promising approaches is spark plasma sintering (SPS), which provides a high heating rate (up to 100–1000 °C/min) by passing pulsed direct current directly through the powder mixture, combined with the simultaneous application of uniaxial pressure []. The advantages of SPS include the possibility of conducting in situ reactive sintering with simultaneous synthesis and consolidation of the target phase [,], as well as a significant reduction in sintering time compared to conventional hot pressing and pressureless sintering methods []. Due to rapid heating and short holding time at the maximum temperature, SPS enables the production of materials with a fine-grained and homogeneous microstructure at a high densification level, suppressing undesirable grain growth [,,]. An important advantage of the SPS method is the absence of fundamental limitations regarding the type of material being sintered: electrically conductive materials are heated by the direct passage of current, while dielectrics and semiconductors are sintered primarily through heating from the graphite tooling [] or alternative refractory matrices [].

For efficient consolidation via SPS and achieving high material density, the use of fine-dispersed powder precursors with particle sizes in the micron and submicron range is critically important. This significantly enhances the chemical reactivity of the components by increasing the specific surface area and shortening diffusion pathways, promotes the formation of the required homogeneous microstructure after sintering, and ensures high particle packing density while minimizing residual porosity []. An effective method for producing reactive powder mixtures with a controlled particle size distribution (PSD) is mechanical activation via high-energy ball milling (HEBM). This process not only increases the overall particle dispersity by grinding coarse fractions but also ensures mixing of the components at the micro-level, accumulation of crystal structure defects, and enhancement of the material’s reactivity [].

Despite numerous studies on high-entropy carbide systems reported in the literature, the systematic investigation of the effect of progressively increasing compositional complexity—from ternary to five-component systems—on phase formation, consolidation kinetics, and the final material properties remains insufficiently explored. In particular, questions regarding how the sequential introduction of additional carbide components affects the PSD of mechanically activated mixtures, the temperature ranges and mechanisms of sintering, the formation of a single-phase high-entropy solid solution, and the distribution of mechanical properties in the consolidated materials remain open.

Potential applications for high-entropy carbides span a wide range of high-tech industries. Owing to their exceptional combination of high hardness, thermal stability, and oxidation resistance, these materials are promising for the production of cutting tools and wear-resistant coatings capable of operating at extreme cutting temperatures (>1000 °C), where traditional WC-Co-based hard metals lose functionality due to the softening of the cobalt binder. In the aerospace industry, high-entropy carbides are considered candidates for thermal protection and thermal barrier coatings on turbine blades and rocket engine combustion chamber components, as they maintain structural integrity at temperatures above 2400 °C. In the field of nuclear energy, the enhanced radiation resistance of high-entropy carbides, driven by the entropy stabilization effect, makes them promising for use as inert matrices for dispersed nuclear fuel and protective coatings for fuel elements in Generation IV reactors. Furthermore, the metal-like electrical conductivity and catalytic activity of carbides open up possibilities for their use as electrode materials for high-temperature fuel cells and electrolyzers.

The combination of mechanical activation and spark plasma sintering offers several technological advantages for the industrial production of high-entropy carbides. Mechanical activation ensures the formation of a homogeneous, fine-grained powder mixture with high reactivity, which can potentially lower the consolidation temperature by 100–200 °C compared to using non-activated powders. SPS enables extremely rapid consolidation (total process time of 30–40 min versus 2–4 h for hot pressing), minimizes undesirable grain growth due to the short dwell time at the maximum temperature, and significantly reduces energy consumption, which is critical for the potential industrial scaling of this technology. Moreover, the possibility of in situ reactive sintering opens prospects for using cheaper precursors (mixtures of elemental metal powders and carbon), which could substantially lower the production cost of high-entropy carbides.

In light of the above, the objective of this work is to establish the patterns of phase transformations and microstructure formation in equimolar mixtures of transition metal carbides WC, TiC, TaC, HfC, and ZrC during their consolidation by SPS, as well as to identify the influence of the system’s multicomponent nature on the physical and mechanical properties of the resulting high-entropy carbides.

In this work, carbide systems with compositions WC-TiC-TaC-HfC and WC-TiC-TaC-HfC-ZrC were fabricated using a combination of HEBM and SPS at 1900 °C. The study demonstrates the feasibility of synthesizing predominantly single-phase high-entropy carbides with a NaCl-type cubic structure and high hardness characteristics. The obtained results contribute to the understanding of the fundamental principles governing the formation of high-entropy carbide systems and can serve as a basis for the targeted design of multicomponent ceramic materials with an improved set of performance characteristics.

2. Materials and Methods

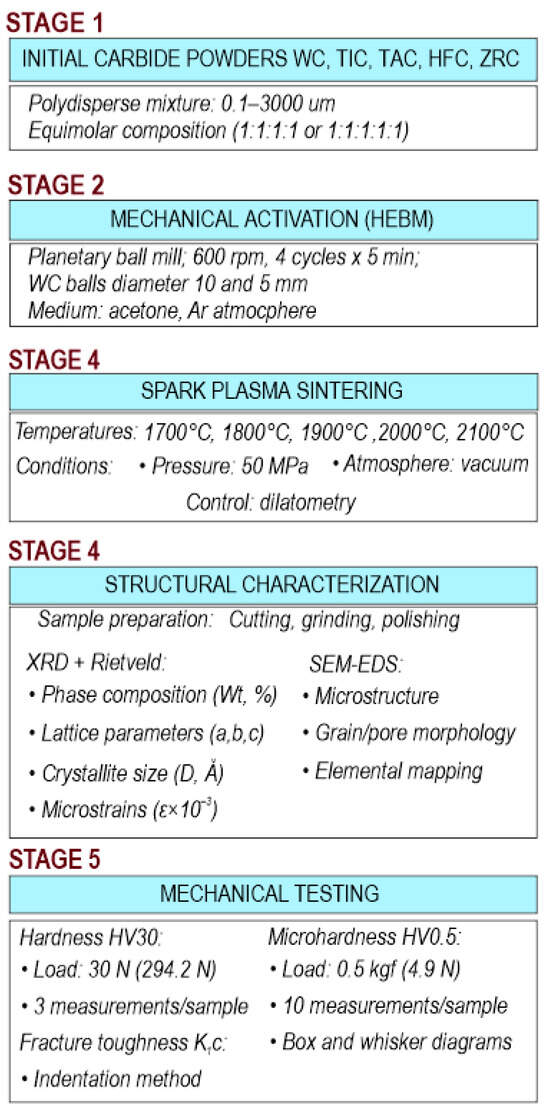

The experimental workflow is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the experimental synthesis process for the high-entropy carbides WC-TiC-TaC-HfC and WC-TiC-TaC-HfC-ZrC, including raw material preparation, mechanical activation of powder mixtures, spark plasma sintering, and comprehensive characterization of the obtained materials.

2.1. Materials

Commercial powders of WC, TiC, TaC, and ZrC with a mass fraction of 99.9% (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were used for synthesizing the initial mixtures.

2.2. Powder Preparation

The preparation of initial carbide mixtures with different ratios was carried out using powder technologies from Changsha Tianchuang Powder Technology Co. Ltd. (Changsha, China) with tungsten carbide grinding jars on a Tencan XQM-0.4A vertical planetary ball mill (Changsha, China). WC balls with diameters of 10 mm and 5 mm were used as grinding media. For every 10 g of the mixture to be milled, 10 large and 10 small balls were used. Milling was conducted at 600 rpm for 4 cycles; each cycle consisted of 20 min of milling and 20 min of cooling for the milling vessel. Milling was performed using a wet process in an anhydrous acetone medium (30 mL). To prevent oxidation of the powder materials, the acetone was pre-treated with argon to remove dissolved oxygen, and additional argon was pumped into the milling container to displace air. After completing the milling process, the container was unsealed and placed in an oven FD 115 (Binder GmbH, Tuttlingen, Germany) at 55 °C to remove the acetone.

2.3. Ceramic Sample Fabrication

SPS of the samples was performed using an SPS-515S system (Dr. Sinter LABTM, Tokyo, Japan) at a temperature of 1900 °C under a constant applied pressure of 57.3 MPa with a heating rate of 100 °C/min. Sintering was conducted according to the following procedure: 5 g of powder was placed into a graphite die (working diameter 10.5 mm), pre-pressed (20 MPa), and then placed into the sintering chamber, which was evacuated (10–5 atm), followed by sintering. The SPS process temperature was monitored using a IR-AHS optical pyrometer (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

The sintering temperature of 1900 °C was selected based on preliminary experiments, which demonstrated that at lower temperatures (1700–1800 °C), incomplete material consolidation occurs, with residual porosity exceeding 11–15% and the persistence of traces of individual carbide phases. The temperature of 1900 °C provides an optimal balance between achieving high relative density, forming a predominantly single-phase high-entropy solid solution, and practical limitations associated with the stability of graphite tooling at higher temperatures. Although kinetic studies indicate the completion of active densification at approximately ~1825 °C, additional heating to 1900 °C with a 20-min hold is necessary to ensure sufficient diffusional mobility of the components and complete homogenization of the solid solution. The holding time of 5 min at the peak temperature was chosen to minimize undesirable grain growth while simultaneously ensuring the completion of interdiffusion and homogenization processes.

2.4. Characterization Methods

The particle size distribution (PSD) of the powders was determined using an Analysette-22 NanoTec/MicroTec/XT laser particle analyzer (Fritsch, Weimar, Germany). Each sample was measured three times, and the results were then averaged.

Automatic polishing of the samples in accordance with the standards for microstructural analysis preparation was performed using a MECATECH 234 automatic grinding and polishing station (PRESI, Grenoble, France).

X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) analysis was performed using a “Kolibri” diffractometer (Burevestnik, Moscow, Russia) with CuKα1-Kα2 radiation (40 kV, 10 mA; mean wavelength λ = 1.5418 Å). The signal was recorded using a Muthen2 detector with a Ni Kβ filter, in the 2θ range of 20–140°, with a step size of 0.0185°.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images were acquired using an ULTRA 55+ scanning electron microscope (ZEISS, Jena, Germany) operating at 2 kV, which was also used for elemental mapping with an X-Max 80 EDS system (Oxford Instruments, Abingdon, UK) at 20 kV.

The specific gravity of the sintered samples was measured by hydrostatic weighing using an AdventurerTM OHAUS Corporation balance (Parsippany, NJ, USA). The relative density (RD) was calculated against the theoretical density of the ceramic samples using the formula:

where ρa is the experimental density and ρt is the theoretical density.

Vickers hardness was measured in accordance with ISO 25947-2:2017 [] using an OMNITEST universal hardness tester under HV30. Microhardness was measured under an HV0.5 load (4.903 N) using a Shimadzu HMV-G-FA-D automatic microhardness tester (Kyoto, Japan).

3. Results

3.1. Evolution of PSD and Phase Composition of Carbide Powders During HEBM

The PSD of the powder mixtures was monitored. This is a critically important factor for obtaining high-quality high-entropy carbide systems.

3.1.1. Particle Size Distribution of Initial Carbide Powders

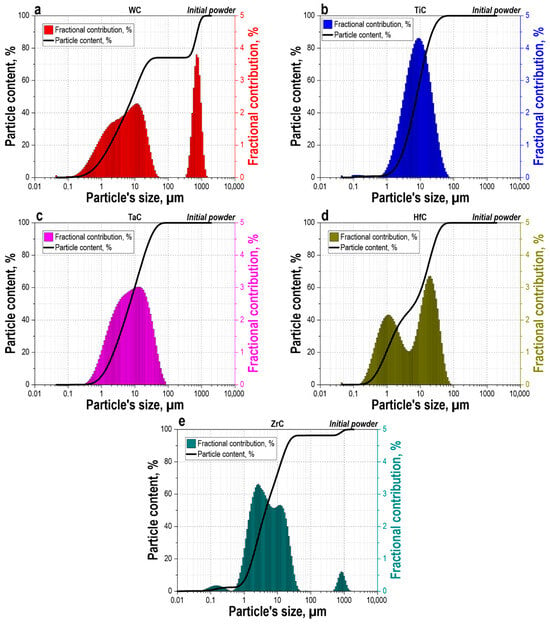

Particle size analysis of the initial carbide powders (Figure 2) reveals significant differences in their PSD, resulting in a polyfractional composition upon mixing. The WC powder exhibits the most complex composition with a bimodal distribution: a primary fraction peaking at 10–20 µm and a second distinct mode of coarse particles around 1000 µm with a fractional contribution up to 4% (Figure 2a). The TiC powder is characterized by a unimodal distribution with a maximum in the 10–50 µm range and a peak fractional contribution of about 4.5–5%, with virtually all material (>95%) consisting of particles below 100 µm (Figure 2b). The TaC powder shows a similar unimodal distribution with a particle size range of 5–100 µm and a maximum fractional contribution at 30–40 µm (Figure 2c). The HfC powder displays a pronounced bimodal distribution with two maxima at 1 µm and 30 µm, covering the broadest size range from submicron to 100 µm (Figure 2d). The ZrC powder has a broader distribution with a main peak in the 2 µm range but also contains a fraction of coarse particles up to 1000 µm (Figure 2e). Thus, the combination of the fine TiC and TaC fractions (predominantly < 100 µm), the medium-dispersed HfC and ZrC fractions (5–100 µm), and the coarse WC component (up to 1000–3000 µm) forms a polyfractional system with a wide spectrum of particle sizes.

Figure 2.

Particle size distribution of the initial carbide powders: (a)—WC, (b)—TiC, (c)—TaC, (d)—HfC, (e)—ZrC. Bar charts show the fractional contribution (left axis), and solid lines indicate the cumulative particle content (right axis).

PSD directly influences sintering kinetics, microstructure homogeneity, and the final material properties. The polyfractional composition of the initial powders, on one hand, can provide efficient particle packing and reduced porosity during compaction. However, the presence of coarse particles (>100 µm) significantly hinders the formation of a homogeneous structure and impedes the complete progression of diffusion processes during sintering due to increased diffusion paths. Fine particles (<10 µm) are characterized by high specific surface area and reactivity, which promote accelerated mass transfer and the formation of a homogeneous solid solution in high-entropy systems.

HEBM not only grinds coarse fractions and evens out the PSD but also promotes the formation of a defective structure that enhances the material’s diffusion activity. However, uncontrolled milling can lead to excessive amorphization, contamination from the grinding media, and undesirable phase transformations. Therefore, systematic analysis of the PSD before and after mechanical activation is necessary to optimize the processing parameters and ensure the reproducibility of the properties of the obtained high-entropy carbides.

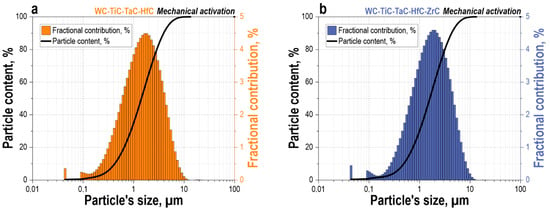

3.1.2. Changes in Particle Size Distribution After Mechanical Activation

HEBM significantly altered the PSD of the powder mixtures (Figure 3). The four-component WC-TiC-TaC-HfC mixture after processing exhibits a unimodal particle distribution with a pronounced maximum in the 0.2–10 µm range and a peak fractional contribution of approximately 4.5% at a size of ~1–2 µm (Figure 3a). The cumulative curve indicates that 100% of the particles are smaller than 10 µm, evidencing significant refinement of the initial powders and the nearly complete elimination of the coarse WC fraction (up to 1100 µm) present in the initial state, which was apparently in the form of agglomerates of smaller particles (Figure 2a). The mechanism of mechanical dispersion and fragmentation of WC particles during ball milling/activation was previously described in detail by us in reference [].

Figure 3.

Particle size distribution of powder mixtures after mechanical activation via HEBM: (a)—WC-TiC-TaC-HfC, (b)—WC-TiC-TaC-HfC-ZrC. Bar charts show the fractional contribution (left axis), and solid lines indicate the cumulative particle content (right axis).

The five-component WC-TiC-TaC-HfC-ZrC mixture exhibits a similar tendency towards forming a narrow unimodal distribution with a maximum in the 0.2–10 µm range and a peak fractional contribution of approximately 4.5–5% at a size of ~1–2 µm (Figure 3b). The particle distribution is virtually identical to that of the four-component system, with over 95% of particles also concentrated in the sub-10 µm range. The addition of ZrC did not lead to a significant change in the distribution pattern, indicating the efficiency of the HEBM process for all mixture components. This is explained by the similar physico-mechanical characteristics of these carbides: both compounds possess a NaCl-type face-centered cubic lattice, comparable hardness values (HfC ~26–28 GPa, ZrC ~25–27 GPa), and elastic modulus, which ensures a similar response to the impact-abrasive action of the WC balls. Thus, the addition of ZrC does not alter the grinding kinetics of the mixture and enables the formation of a high-entropy five-component system while maintaining the homogeneous fine-dispersed composition required for subsequent consolidation.

HEBM led to a radical transformation of the PSD: a polyfractional system with a wide range of particle sizes from submicron to millimeter (Figure 2) was converted into a homogeneous fine-dispersed system with a narrow distribution in the 0.1–10 µm range. This is attributed to several factors: firstly, the intensive impact-abrasive action of the WC balls at 600 rpm ensured effective grinding of coarse particles, especially the bimodal WC fraction; secondly, the multi-cycle processing regime (4 cycles of 20 min with cooling) promoted the gradual breakdown of agglomerates and leveling of particle sizes; and thirdly, the use of a liquid medium (acetone) prevented the agglomeration of fine particles and facilitated more efficient dispersion. The elimination of coarse fractions and the formation of a homogeneous fine-dispersed structure are critically important for the subsequent consolidation of high-entropy carbide systems, as they ensure uniform distribution of components, increase the area of interphase boundaries, and promote more complete diffusion processes during sintering.

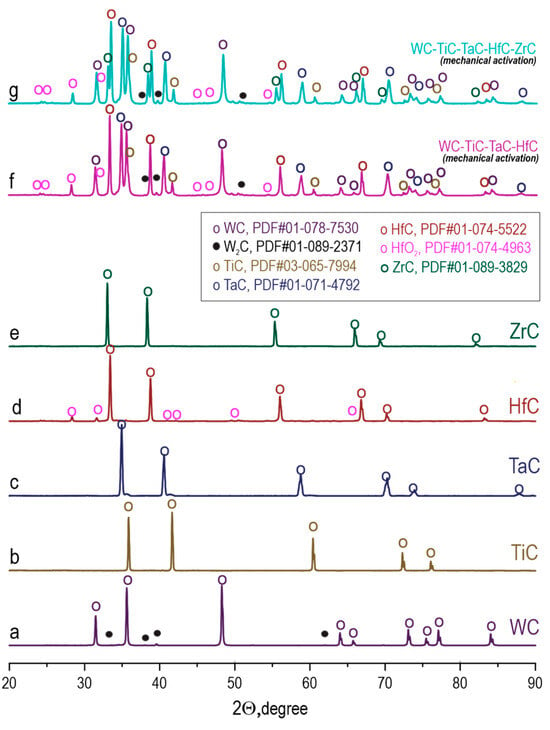

3.1.3. Phase Composition and Structural Characteristics of Initial Powders and Mechanically Activated Mixtures

XRD of the initial carbide powders (Figure 4a–e) shows that TiC, TaC, and ZrC are represented by a single carbide phase with a NaCl-type cubic structure (space group Fm-3m). The WC powder contains the primary hexagonal WC phase (97.9 wt. %) and an impurity trigonal W2C phase (2.1 wt. %), indicating non-stoichiometry of the tungsten carbide and a carbon deficiency in the initial material. The HfC powder is characterized by the presence of an oxide impurity, monoclinic HfO2 (14.9 wt. %), which is typical for hafnium carbides due to their high affinity for oxygen.

Figure 4.

Diffractograms of the initial carbide powders ((a)—WC, (b)—TiC, (c)—TaC, (d)—HfC, (e)—ZrC) and mechanically activated via HEBM mixtures ((f)—WC-TiC-TaC-HfC, (g)—WC-TiC-TaC-HfC-ZrC). Symbols denote reflections of the corresponding phases according to the PDF-2 database.

After HEBM (Figure 4f,g), the diffractograms of the WC-TiC-TaC-HfC and WC-TiC-TaC-HfC-ZrC mixtures show the presence of all initial carbide phases, indicating the absence of chemical interaction and phase transformations during the milling process. However, a noticeable broadening of the diffraction peaks is observed compared to the initial powders, which is caused by the refinement of crystallites and the accumulation of crystal structure defects under the influence of impact-abrasive loads.

Full-profile quantitative Rietveld analysis (Table 1) reveals insignificant deviations in the mass fractions of the components from the calculated equimolar ratio. In the four-component WC-TiC-TaC-HfC mixture, the phase content is: WC—29.2 wt. % (28.3% WC + 0.9% W2C), and 23.3 at. % (22.5 + 0.7); TiC—11.1 wt. %, and 28.9 at. %; TaC—28.9 wt. % and 23.3 at. %; and HfC—30.8 wt. % (24.6% HfC + 6.2% HfO2) and 24.5 at. %, differing slightly from the expected 25 at. % for each component. Deviations from the equimolar composition are associated with the error of quantitative Rietveld analysis for multicomponent systems, especially in the presence of oxide impurities. A similar pattern is observed for the five-component mixture: WC—25.3 wt. % and 18 at. %; TiC—10.9 wt. % and 25.4 at. %; TaC—25.3 wt. % and 18.3 at. %; HfC—26.0 wt. % and 18.5 at. %; and ZrC—14.7 wt. % and 19.8 at. % against a calculated value of 20%.

Table 1.

Results of quantitative phase analysis by the Rietveld method for the initial carbide powders and mechanically activated mixtures via HEBM: unit cell parameters (a, b, c), mass fraction of phases (Wt), unit cell volume (V), and reliability factors of the calculation (Rwp).

An important observation is the increase in the content of the impurity W2C phase after HEBM from 2.1 wt. % (2.2 at. %) in the initial WC powder to 0.9 wt. % (0.7 at. %) and 0.8 wt. % (0.6 at. %) in absolute terms for the mixtures. However, when recalculated relative to the WC content, the proportion of W2C increases: in the initial powder, the W2C/WC ratio is 2.1/97.9 = 0.021, while in the four-component mixture, it is 0.9/28.3 = 0.032, and in the five-component mixture, it is 0.8/24.5 = 0.033. This indicates a relative enrichment of the system with the W2C phase during HEBM. The observed relative increase in the W2C fraction may have several possible explanations, which require experimental verification. The increase in the relative W2C content may be associated with the release of fine W2C particles from large agglomerates during the milling process. To a lesser extent, this effect could be related to local heating and partial decarburization of WC under intensive mechanical impact. Since WC is a non-stoichiometric compound with variable carbon content (formula WC1−x, where x = 0–0.4), HEBM might have led to preferential decarburization of WC particles with low carbon stoichiometry, forming the more stable W2C phase under mechanical stress. An alternative explanation could be the carbothermal reduction of oxide films on the surface of WC particles with the release of CO and the formation of the carbon-depleted W2C phase. It should be noted that intensive mechanical action in the presence of grinding media creates local zones with high temperature (estimated at 200–400 °C) and pressure, which can initiate such processes despite the protective argon atmosphere. However, this hypothesis requires confirmation by direct elemental analysis of the carbon content in the powders before and after mechanical activation, which was not performed as part of this study. The absence of carbon elemental analysis data limits the ability to unambiguously interpret the observed changes in the content of the impurity phase W2C after mechanical activation.

Given the limitations of the available data, we cannot unambiguously determine the mechanism behind the observed change in the relative content of W2C. To conclusively resolve this issue, future studies should involve direct elemental CHNS analysis of the carbon content in the powders before and after HEBM, as well as a more detailed investigation using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) to analyze the chemical state of the particle surfaces. Nevertheless, it is important to emphasize that, regardless of the precise mechanism, the observed changes in the W2C content at the level of 0.7–1.0 wt. % are minimal and do not significantly impact the overall process of high-entropy solid solution formation during subsequent sintering, as evidenced by the complete disappearance of the W2C phase in the consolidated samples.

Analysis of the unit cell parameters of the carbide phases shows minimal changes after mechanical activation. For TiC, the lattice parameter increases from 4.3264 Å to 4.3269 Å (+0.01%); for TaC—from 4.4359 Å to 4.4395 − 4.4398 Å (+0.08–0.09%); for HfC, the changes range from 4.6387 Å to 4.6382 − 4.6385 Å (−0.01%); and for ZrC—a decrease from 4.6954 Å to 4.6921 Å (−0.07%). The lattice parameters of WC remain practically unchanged (a = 2.9060→2.9046 − 2.9049 Å, c = 2.8371→2.8364 − 2.8365 Å). The corresponding changes in unit cell volumes are also insignificant: for TiC from 80.983 to 81.009 − 81.012 Å3 (+0.03%); for TaC from 87.288 to 87.499 − 87.521 Å3 (+0.24–0.27%); for HfC from 99.813 to 99.784 − 99.801 Å3 (−0.01–0.03%); and for ZrC from 103.521 to 103.301 Å3 (−0.21%). Such minor changes in lattice parameters and unit cell volumes (within 0.01–0.27%) are at the level of the Rietveld method’s error (typically ±0.001 − 0.002 Å for lattice parameters) and cannot reliably indicate substantial structural rearrangements or mutual doping of the carbides during HEBM. This confirms that under the selected milling conditions (4 cycles of 20 min, 600 rpm), the process is predominantly mechanical in nature, involving particle size reduction without significant alteration of the crystalline structure of the phases and without initiating solid-state reactions between the components. The content of the HfO2 oxide phase decreases from 14.9% in the initial powder to 6.2% and 5.3% in the mixtures. The unit cell volume of HfO2 remains practically unchanged, indicating the stability of its crystal structure during HEBM.

The content of the HfO2 oxide phase changes from 14.9 wt. % (13.9 at. %) in the initial HfC powder to 6.2 wt. % (4.6 at. %) in the four-component mixture and 5.3 wt. % (3.5 at. %) in the five-component mixture. When recalculated relative to the HfC content, in the initial powder, HfO2/HfC = 14.9/84.1 = 0.177 (17.7%); in the four-component mixture, 6.2/24.6 = 0.252 (25.2%); and in the five-component mixture, 5.3/20.7 = 0.256 (25.6%). The increase in the relative HfO2 content may be associated with partial oxidation of HfC during HEBM, despite the process being conducted in a protective argon atmosphere, or with the redistribution and dispersion of oxide inclusions, which improves their detection by XRD. It can also be assumed that no significant phase transformations of the oxide occur during HEBM, and the observed changes in content are primarily related to a more uniform distribution of HfO2 within the material volume and an improvement in its X-ray detectability after dispersion.

Thus, XRD confirms that HEBM under the selected regimes provides effective grinding and homogenization of the powder mixture without significant alteration of the crystalline structure of the initial carbides. The absence of new phase formations and the minimal changes in the lattice parameters of the individual carbides indicate that the process is predominantly mechanical in nature, without initiating chemical interaction between the components. This is a necessary condition for the subsequent formation of a homogeneous high-entropy solid solution during sintering, as all components are in a highly dispersed state with a developed surface area, which promotes accelerated diffusion processes and homogenization of the system at high temperatures.

3.2. Consolidation of High-Entropy Carbide Mixtures by SPS

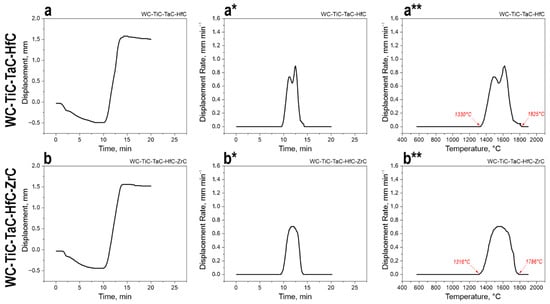

The consolidation process of HEBMed carbide mixtures by SPS at a temperature of 1900 °C is characterized by a single-stage mechanism of active densification, as confirmed by the analysis of shrinkage curves and punch displacement rate (Figure 5(a,a*,b,b*)).

Figure 5.

Kinetics of consolidation of high-entropy carbide mixtures by spark plasma sintering at a maximum temperature of 1900 °C: (a,b)—time dependence of punch displacement (sample shrinkage) for the four-component WC-TiC-TaC-HfC system (a) and the five-component WC-TiC-TaC-HfC-ZrC system (b). The curves show the change in the linear shrinkage of the sample (in mm) during the sintering process; (a*,b*)—time dependence of the punch displacement rate (shrinkage rate) for the four-component system (a*) and the five-component system (b*). The curves demonstrate the intensity of the densification process (in mm·min−1) as a function of time; (a**,b**)—Temperature dependence of the punch displacement rate for the four-component system (a**) and the five-component system (b**). The curves show how the shrinkage rate changes depending on the process temperature, allowing for the identification of the temperature intervals of active sintering.

For the four-component WC-TiC-TaC-HfC mixture, the onset of active shrinkage is observed at 10–12 min of holding time (Figure 5a), which corresponds to a temperature of approximately 1200–1300 °C, after which intensive material densification occurs, reaching a maximum punch displacement of ~1.55 mm by the 15th minute of the process. The shrinkage rate curve (Figure 5(a*)) shows a single pronounced peak with a maximum of about 0.9 mm·min−1 in the interval of 10–14 min, corresponding to the stage of the most intensive mass transfer. Analysis of the temperature dependence of the shrinkage rate (Figure 5(a**)) indicates that the active densification process occurs within the temperature range of 1330–1825 °C, with the maximum shrinkage rate achieved at 1330 °C, followed by a gradual decrease in densification intensity as the temperature rises to 1825 °C, where the process is practically completed.

The five-component WC-TiC-TaC-HfC-ZrC mixture exhibits similar densification kinetics (Figure 5(b,b*)), but with some differences in the temperature parameters. The onset of active shrinkage is also observed at 10–12 min of holding time, reaching a maximum punch displacement of ~1.55 mm by the 15th minute (Figure 5b). The shrinkage rate curve (Figure 5(b*)) shows a maximum of about 0.7 mm·min−1, which is somewhat lower than for the four-component system. The temperature dependence (Figure 5(b**)) indicates a shift in the active sintering temperature range towards higher values: 1316–1786 °C, with the maximum shrinkage rate achieved at 1316 °C and the process completion occurring at 1786 °C.

The 22% reduction in maximum shrinkage rate (from 0.9 to 0.7 mm·min−1) upon introducing ZrC into the five-component system is attributed to the specific diffusion characteristics of zirconium carbide. The coefficient of Zr self-diffusion at 1900 °C is significantly lower than that of W and Ti and is comparable to that of the slowest-diffusing element, Hf. The introduction of Zr4+ (ionic radius 0.72 Å) increases the lattice distortion parameter, as confirmed by the observed increase in the lattice parameter. Enhanced local distortions create additional energy barriers for atomic migration, while the increase in configurational entropy from ΔS_conf = 11.53 to 13.38 J/(mol·K) leads to a greater variation in M-C bond energies within local coordination environments.

ZrC is characterized by a more pronounced covalent character of the Zr-C bond and a higher vacancy formation energy compared to TiC, which reduces the equilibrium vacancy concentration and slows down the vacancy-mediated diffusion mechanism. The specific influence of ZrC on grain boundary diffusion, which controls sintering at 1900 °C, is associated with its higher grain boundary energy, which enhances impurity segregation and retards grain boundary mobility.

Thus, the observed reduction in shrinkage rate results from the synergistic action of the low intrinsic diffusional mobility of Zr, increased lattice distortions, higher configurational entropy, and the specific influence on grain boundary structure. This represents not merely a general multicomponent effect but has a concrete physicochemical basis rooted in the unique properties of ZrC. The temperature ranges of active sintering for both systems lie within 1316–1825 °C, which is significantly lower than the melting points of the individual carbides (TaC—3880 °C, HfC—3959 °C, ZrC—3540 °C, TiC—3067 °C, WC—2870 °C). This indicates the predominance of a solid-state sintering mechanism involving diffusion processes along grain boundaries and volume diffusion. The onset of active densification at 1316–1330 °C correlates with the activation temperature for diffusion of carbon and metallic components in carbide systems. The presence of WC, with the lowest melting point, promotes the formation of primary sintering sites and activates mass transfer within the mixture.

It is important to note that the presence of the HfO2 oxide phase can have a dual effect on the sintering process: on one hand, oxide inclusions hinder the formation of interparticle contacts between carbide phases and reduce the thermal conductivity of the powder composition, which may explain the necessity for higher temperatures to complete densification; on the other hand, at high temperatures, partial reduction of HfO2 by carbon from the carbide matrix with the formation of HfC and CO is possible, which contributes to additional material densification.

The observed shift in the sintering completion temperature from 1825 °C for the four-component system to 1786 °C for the five-component system may be associated with differences in particle packing and the formation of percolation paths for diffusion. Despite the lower maximum shrinkage rate, the five-component system achieves a comparable level of densification (~1.55 mm) within the same time interval, indicating a more prolonged stage of active sintering with less intense but more uniform mass transfer.

Thus, the consolidation of high-entropy carbide mixtures by SPS at 1900 °C proceeds predominantly via a solid-state sintering mechanism within the temperature range of 1316–1825 °C. The introduction of a fifth component (ZrC) leads to a reduction in densification intensity but does not prevent the achievement of a high degree of material consolidation. The obtained data on sintering kinetics allow for the optimization of temperature-time consolidation regimes to achieve minimal porosity and the formation of a homogeneous microstructure in high-entropy carbides.

3.3. Microstructure and Elemental Composition of High-Entropy Carbides After Consolidation by SPS

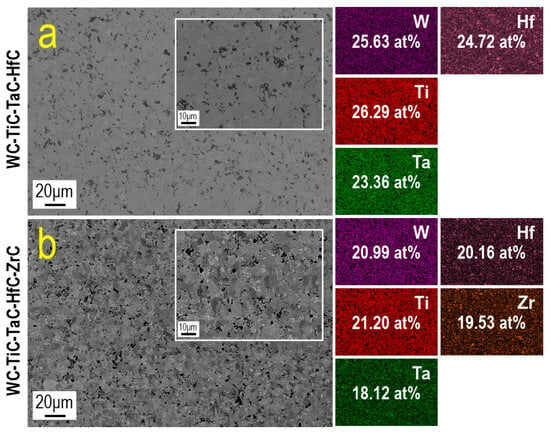

Microstructural analysis of the consolidated samples by SEM is presented in Figure 6. The four-component WC-TiC-TaC-HfC system (Figure 6a) exhibits a relatively homogeneous microstructure with uniform element distribution and the presence of dark contrast inclusions sized 1–5 µm, corresponding to porosity. The light gray matrix background indicates the formation of a consolidated structure with multiple intergranular boundaries. At higher magnification (inset, Figure 6a), a fine-grained structure is observed with a characteristic size of structural elements less than 10 µm and the presence of dark, irregularly shaped pores distributed throughout the material volume.

Figure 6.

Microstructure (SEM) and elemental distribution maps (EDS) of high-entropy carbides consolidated by SPS: (a)—WC-TiC-TaC-HfC, (b)—WC-TiC-TaC-HfC-ZrC. Insets show the microstructure at higher magnification. Atomic concentrations of metallic components according to EDS analysis are indicated.

The five-component WC-TiC-TaC-HfC-ZrC system (Figure 6b) is characterized by a higher degree of porosity compared to the four-component system. The microstructure contains a significant number of dark contrast regions of irregular shape, sized 2–10 µm, corresponding to pores, which is consistent with the reduced shrinkage rate during sintering (Figure 5b). The pore distribution is relatively uniform, although local clusters are observed in some areas. At higher magnification (inset, Figure 6b), a heterogeneous structure is visible, with alternating light and darker grains sized 3–8 µm, which may indicate differences in the content of heavy elements (W, Hf, Ta) in different structural regions. It should be noted that the visual differences in the porosity characteristics between the four-component and five-component systems, observed in the presented SEM images, may be attributed to local microstructural heterogeneity and do not reflect significant differences in the overall porosity of the materials. Quantitative relative density measurements using the Archimedes method show nearly identical values for both systems (~91.75%), indicating a comparable degree of consolidation. Local variations in pore distribution visible in the SEM images are a characteristic feature of ceramic materials produced by powder metallurgy methods and are associated with inhomogeneous particle packing and the progression of diffusion processes in different regions of the sample.

The EDS results show the distribution of metallic components in the consolidated samples. For the four-component system (Figure 6a), the atomic concentrations are: W—25.63 at. %, Hf—24.72 at. %, Ti—26.29 at. %, and Ta—23.36 at. %, which is sufficiently close to the equimolar ratio (25 at. % for each element). The maximum deviation is +1.29 at. % for Ti and −1.64 at. % for Ta, which is within the acceptable error margin of the EDS method and indicates a high degree of elemental composition homogenization during mechanical activation and subsequent sintering. The elemental distribution maps demonstrate a uniform distribution of all four metallic components throughout the material volume without clear signs of segregation or the formation of enriched zones.

For the five-component system (Figure 6b), the atomic concentrations are: W—20.99 at. %, Hf—20.16 at. %, Ti—21.20 at. %, Ta—18.12 at. %, and Zr—19.53 at. %, which is also close to the equimolar ratio (20 at. % for each element). The maximum deviations are +1.20 at. % for Ti and −1.88 at. % for Ta. Despite the increase in configurational entropy upon adding the fifth component, the system maintains a relatively uniform element distribution. However, the distribution maps show some heterogeneity in the distribution of Zr, with the formation of local areas of increased concentration, which may be associated with the lower degree of ZrC refinement and its tendency to retain the original particle morphology.

An important observation is the absence of clearly defined regions of unreacted initial carbides or their interaction products with contrast significantly different from the matrix phase in the microstructure of both systems. This indicates the occurrence of mutual diffusion processes of metallic components and carbon, leading to the formation of a substitutional solid solution based on the NaCl-type cubic lattice, which is characteristic of high-entropy carbide systems.

The presence of residual porosity is more pronounced in the five-component composition in both systems. The pores are predominantly irregularly shaped and located both at grain boundaries and within grains, which is typical for solid-state sintering of high-temperature carbides.

Thus, microstructural analysis confirms the formation of relatively homogeneous high-entropy carbide materials with a near-equimolar distribution of metallic components. The introduction of ZrC into the five-component system leads to an increase in residual porosity, which is consistent with the kinetic data on the reduced densification intensity during sintering and necessitates the optimization of consolidation regimes to obtain denser materials.

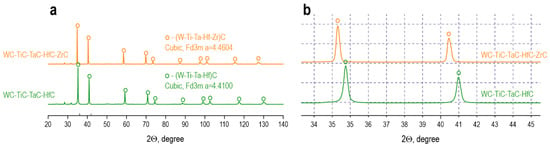

3.4. Phase Composition and Crystal Structure of Consolidated High-Entropy Carbides

XRD of the samples after consolidation by SPS at 1900 °C (Figure 7a) demonstrates a radical transformation of the phase composition compared to the mechanically activated powder mixtures. Both systems are characterized by the formation of a predominantly single-phase high-entropy solid solution structure with a NaCl-type cubic lattice (space group Fm-3m), confirming the successful mutual diffusion of metallic components and the formation of a homogeneous substitutional carbide solution.

Figure 7.

Diffractograms of high-entropy carbides WC-TiC-TaC-HfC and WC-TiC-TaC-HfC-ZrC consolidated by SPS at 1900 °C: (a)—full angular range, (b)—enlarged region of the main (111) and (200) reflections.

For the four-component WC-TiC-TaC-HfC system (Figure 7a), the diffractogram shows a set of narrow, symmetric reflections corresponding to a cubic (W-Ti-Ta-Hf)C phase with a lattice parameter a = 4.4101 Å (Table 2). Quantitative Rietveld analysis indicates that the main carbide phase constitutes 100 wt. % of the carbide constituent, while the residual oxide phase HfO2 is present in an amount of 7 wt. % with monoclinic lattice parameters a = 5.1065 Å, b = 5.1701 Å, c = 5.2861 Å, β = 99.1971°. The complete disappearance of individual reflections from the initial carbides WC (hexagonal); TiC, TaC, and HfC (cubic with different lattice parameters of 4.3269, 4.4395, and 4.6382 Å, respectively, Table 1); and the impurity W2C phase indicates the completion of the homogenization process and the formation of a homogeneous solid solution. The significant narrowing of the diffraction peaks compared to the mechanically activated mixtures (Figure 4f) points to crystallite growth and the relaxation of the defective structure during high-temperature sintering.

Table 2.

Structural characteristics of the high-entropy carbide systems WC-TiC-TaC-HfC and WC-TiC-TaC-HfC-ZrC obtained by a combination of mechanical activation and SPS at 1900 °C: unit cell parameters (a, b, c), mass fraction of phases (Wt), reliability factors of the calculation (R2), average crystallite size, lattice microstrain (ε), and dislocation density (ρD).

The five-component WC-TiC-TaC-HfC-ZrC system (Figure 7a) also demonstrates the formation of a high-entropy solid solution (W-Ti-Ta-Hf-Zr)C with a cubic structure, but with an increased lattice parameter a = 4.4604 Å. The content of the main carbide phase is 96 wt. %, and the residual oxide phase HfO2 is 4 wt. % with parameters a = 5.1295 Å, b = 5.1586 Å, c = 5.3154 Å, and β = 99.1125°.

A detailed analysis of the region of the main (111) and (200) reflections at an enlarged scale (Figure 6b) allows for the assessment of structural differences between the systems. The (111) reflection for the four-component system is located at 2θ ≈ 35.8°, while for the five-component system it is shifted to lower angles at 2θ ≈ 35.4°, which corresponds to an increase in the interplanar spacing according to Bragg’s law and correlates with the increase in lattice parameter from 4.4101 to 4.4604 Å (+1.14%). A similar shift is observed for the (200) reflection from 2θ ≈ 41.8° to 2θ ≈ 41.2°. The increase in lattice parameter upon the introduction of ZrC is explained by the difference in atomic radii of the metallic components: the radius of Zr4+ (0.72 Å) is larger than the average radius of the substituted cations W4+ (0.66 Å), Ti4+ (0.61 Å), Ta4+ (0.72 Å), and Hf4+ (0.71 Å), which leads to an expansion of the crystal lattice according to Vegard’s rule.

The lattice parameter of the four-component solid solution (W-Ti-Ta-Hf)C (a = 4.4101 Å) occupies an intermediate position between the parameters of the initial carbides: TiC (4.3264 Å), TaC (4.4359 Å), HfC (4.6387 Å), and WC (when converting the hexagonal structure to a pseudo-cubic one, a ≈ 4.22 Å), which corresponds to the pattern of substitutional solid solution formation. The deviation from the linear dependence of the lattice parameter on composition (Vegard’s rule) may be associated with effects of local ordering of different metal atoms in the metal sublattice and differences in the degree of filling of the carbon sublattice for different components.

Analysis of the microstructural parameters (Table 2) shows that the average crystallite size in the four-component system is 83.6 nm, while in the five-component system, it is 153.1 nm, which is 84.3% larger. The increase in crystallite size upon the introduction of ZrC may be attributed to several factors: firstly, the higher mobility of atoms in the five-component solution at the sintering temperature, which promotes recrystallization and grain growth, and secondly, a possible change in the mass transfer mechanism from predominantly grain boundary diffusion to volume diffusion, which is characteristic of systems with increased configurational entropy. The lattice microstrain (ε) for both systems is at a comparable level: 0.86 × 10−3 for the four-component and 0.92 × 10−3 for the five-component system, indicating a similar degree of defectiveness in the crystal structure.

The persistence of the residual oxide phase HfO2 in the amount of 4–7 wt. % after sintering at 1900 °C indicates incomplete reduction of hafnium oxide by carbon from the carbide matrix. This is explained by the high thermodynamic stability of HfO2 (ΔG°f,298 = −1117.6 kJ/mol) and the relatively low activity of carbon in the high-entropy solid solution. Thermodynamic calculations show that the reduction reaction HfO2 + 3C → HfC + 2CO becomes thermodynamically favorable only at temperatures above 2000–2200 °C under conditions of free desorption of gaseous CO. Under SPS conditions with an applied pressure of 50 MPa and a limited reaction volume, the desorption of CO is hindered, shifting the equilibrium towards the preservation of HfO2. Increasing the sintering temperature above 1900 °C could potentially promote more complete reduction of the oxide; however, this is associated with an increased risk of graphite tooling degradation and undesirable grain growth. A systematic investigation of the influence of sintering temperature within the 1900–2100 °C range on the residual HfO2 content and material properties is of interest for future research.

The formation of predominantly single-phase solid solutions in both systems can be explained through thermodynamic considerations of configurational entropy. The four-component system (WC-TiC-TaC-HfC) with ΔSconf = 11.53 J/(mol·K) (1.39R) represents a medium-entropy material, while the five-component system (WC-TiC-TaC-HfC-ZrC) with ΔSconf = 13.38 J/(mol·K) (1.61R) qualifies as a high-entropy material according to the ΔSconf ≥ 1.5R criterion. The higher configurational entropy in the five-component system provides stronger entropic stabilization of the disordered solid solution, which helps suppress the formation of ordered phases and intermetallic compounds at elevated temperatures. This enhanced entropic stabilization, combined with a relatively small mixing enthalpy due to similar crystal structures (all carbides possess a cubic NaCl-type structure) and comparable cationic radii of the metals (W4+: 0.66 Å, Ti4+: 0.61 Å, Ta4+: 0.72 Å, Hf4+: 0.71 Å, Zr4+: 0.72 Å), favors the formation of single-phase high-entropy solid solutions over competing multi-phase assemblies. The observed differences in consolidation kinetics, crystallite size evolution, and mechanical properties between the four- and five-component systems can be partially attributed to this difference in configurational entropy and its influence on atomic mobility and thermodynamic driving forces during the sintering process. Thus, XRD analysis of the consolidated samples confirms the successful formation of high-entropy carbide solid solutions (W-Ti-Ta-Hf)C and (W-Ti-Ta-Hf-Zr)C with a NaCl-type cubic structure. The introduction of ZrC into the five-component system leads to an increase in the lattice parameter (+1.14%), growth in crystallite size (+67.6%), and a decrease in dislocation density (−43.3%), indicating altered kinetics of recrystallization processes and relaxation of the defective structure during high-temperature sintering. The persistence of the residual HfO2 oxide phase in amounts of 4–7 wt. % requires further optimization of synthesis conditions to achieve a fully single-phase state of the high-entropy carbides.

3.5. Physical and Mechanical Characteristics of Consolidated High-Entropy Carbides

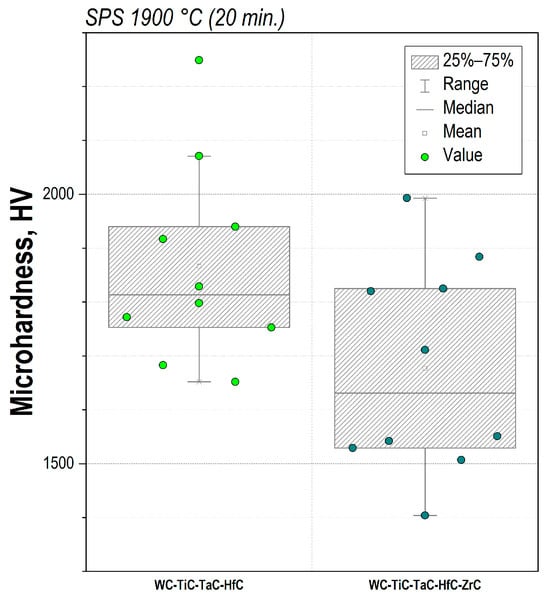

Analysis of the physical and mechanical properties of the consolidated high-entropy carbide systems (Table 3, Figure 8) reveals significant differences in the density and hardness characteristics of the materials.

Table 3.

Physical and mechanical characteristics of the consolidated high-entropy carbides: experimental density, relative density, HV30 hardness, and average microhardness HV.

Figure 8.

Distribution of Vickers microhardness values for high-entropy carbides WC-TiC-TaC-HfC and WC-TiC-TaC-HfC-ZrC consolidated by SPS at 1900 °C (20 min).

The four-component WC-TiC-TaC-HfC system is characterized by a density of 11.0225 g/cm3 and a relative density of 91.74% of the theoretical value, indicating the presence of residual porosity of about 8.26%. This value correlates with microstructural observations (Figure 6a), which show discrete pores sized 1–5 µm uniformly distributed throughout the material volume. The five-component WC-TiC-TaC-HfC-ZrC system exhibits a close relative density of 91.75%; however, the absolute density is 10.0588 g/cm3, which is 8.7% lower than that of the four-component system. The decrease in density upon the introduction of ZrC is explained by the lower atomic mass of zirconium (91.22 amu) compared to the weighted average atomic mass of the substituted elements in the four-component system (W—183.84, Hf—178.49, Ta—180.95, Ti—47.87 amu), leading to a decrease in mass while maintaining the crystal lattice volume. At the same time, the nearly identical relative density values (~91.75%) for both systems indicate a comparable degree of material consolidation under the selected SPS regimes, despite the differences in sintering kinetics (Figure 5).

Analysis of the Vickers microhardness distribution (Figure 8) reveals significant differences between the systems both in average values and in the nature of the distribution. The four-component WC-TiC-TaC-HfC system demonstrates an average microhardness value of 1860 HV with a median around 1820 HV. The interquartile range (25–75%) is approximately 1750–1900 HV, corresponding to a spread of ~150 HV. The full range of values extends from a minimum of ~1300 HV to a maximum of ~2450 HV, with two distinct outliers observed in the high-value region (~2150 HV and ~2450 HV). The broad hardness distribution indicates microstructural heterogeneity of the material, which may be associated with the presence of local areas with varying degrees of consolidation, residual porosity, and inclusions of the HfO2 oxide phase (7 wt. %, Table 2).

The five-component WC-TiC-TaC-HfC-ZrC system is characterized by an average microhardness value of 1680 HV with a median around 1640 HV, which is 9.7% lower than the four-component system. The interquartile range is approximately 1510–1810 HV (~220 HV), which is wider than that of the four-component system. The full range of values extends from ~1400 HV to ~2000 HV. The lower maximum of the distribution compared to the four-component system (2000 HV vs. 2450 HV) indicates the absence of local high-hardness regions, which may be associated with a more uniform distribution of components in the five-component solid solution.

The paradoxical relationship between Vickers hardness under a 30 kgf load (HV30) and the average microhardness requires detailed analysis. For the four-component system, HV30 is 1631.6, which is significantly lower than the average microhardness of 1860 HV. For the five-component system, HV30 = 2008.1 substantially exceeds the average microhardness of 1680 HV. This discrepancy is explained by the indentation size effect: HV30 measurements under a high load (30 kgf ≈ 294.2 N) create an imprint tens of micrometers in size, which encompasses a large material volume including pores, grain boundaries, and oxide inclusions, providing an averaged macrohardness characteristic. Microhardness, measured at a significantly lower load (typically 0.1–2 kgf), reflects the hardness of local microstructural elements—individual grains of the solid solution.

The high HV30 value for the five-component system (2008.1), coupled with a relatively low average microhardness (1680 HV), may indicate a solid solution strengthening effect at the macrostructure scale. The increased crystallite size (83.6 nm vs. 153.1 nm, Table 2) and larger grains provide a smaller fraction of grain boundaries, which act as stress concentrators during indentation with a large indenter. Furthermore, according to the Hall–Petch relationship for ceramic materials, within a certain grain size range, an inverse effect can be observed where an increase in grain size leads to enhanced resistance to plastic deformation during macroindentation due to a reduced contribution from grain boundary sliding.

For the four-component system, the low HV30 value (1631.6) combined with high average microhardness (1860 HV) is explained by the negative influence of residual porosity and oxide inclusions (7 wt. % HfO2) on the macro-mechanical characteristics. During high-load indentation, cracks propagate primarily along grain boundaries and through porous regions, which reduces the measured hardness. The local high-hardness areas detected during microindentation (outliers up to 2230 HV in Figure 8) correspond to grains of the high-entropy solid solution that are free from defects and oxide inclusions.

The 9.7% decrease in the average microhardness of the five-component system compared to the four-component one can be attributed to several factors. Firstly, the increase in lattice parameter from 4.4101 to 4.4604 Å (+1.14%, Table 2) leads to a reduction in atomic packing density and a decrease in bond energy, which facilitates plastic deformation during indentation. Secondly, the 84.3% increase in crystallite size (from 83.5 to 153.1 nm) may reduce the contribution of grain boundary strengthening according to the Hall–Petch relationship for microhardness, which for ceramics is expressed as HV = HV0 + k·d−1/2, where d is the grain size.

The wide scatter in microhardness values for both systems (standard deviation estimated at ~200–250 HV) indicates microstructural heterogeneity of the consolidated materials. This may be associated with incomplete homogenization of the solid solution, the presence of compositional fluctuations in the distribution of metallic components (partially confirmed by the EDS maps in Figure 6), and local variations in density and grain size. The presence of residual porosity ~8.25% and the HfO2 oxide phase also contribute to the heterogeneity of mechanical properties, as indentation near pores or oxide inclusions yields lower hardness values.

Thus, physico-mechanical analysis shows that both high-entropy carbide systems achieve a comparable degree of consolidation (~91.75%) but exhibit differences in hardness distribution and macro-mechanical characteristics. The four-component WC-TiC-TaC-HfC system is characterized by higher average microhardness (1860 HV) due to smaller grain size and higher dislocation density, but reduced macrohardness HV30 (1631.6) due to the influence of porosity and oxide inclusions. The five-component WC-TiC-TaC-HfC-ZrC system demonstrates higher macrohardness HV30 (2008.1) owing to grain coarsening and lower oxide phase content, but reduced average microhardness (1680 HV) resulting from decreased structural defect density. To achieve higher and more uniform mechanical characteristics, further optimization of sintering regimes is necessary to reduce residual porosity and completely eliminate the HfO2 oxide phase.

3.6. Comparative Analysis of Properties with Monolithic Carbides

The comparative physico-mechanical characteristics of the synthesized high-entropy carbides and individual monolithic transition metal carbides are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Comparative physico-mechanical characteristics of the synthesized high-entropy carbides and individual monolithic transition metal carbides.

A comparison of the physico-mechanical characteristics of the synthesized high-entropy carbides with individual monolithic carbides (Table 4) allows for an assessment of the influence of multicomponent composition and entropic stabilization on material properties. The relative density of the obtained HEC systems (~91.75%) was lower than that of monolithic carbides produced by hot pressing (96–99%), which is associated with the selected SPS parameters (1900 °C, 20 min) and the presence of the residual HfO2 oxide phase (4–7 wt. %). Monolithic carbides are typically sintered at higher temperatures (2000–2200 °C) and with longer holding times (1–4 h), which ensures more complete consolidation but requires significantly greater energy input.

Analysis of hardness values shows that individual carbides exhibit a wide range of hardness: from 1600–2000 HV for TaC to 2800–3200 HV for TiC. The high hardness of TiC and HfC is due to strong covalent Ti-C and Hf-C bonds and the high atomic packing density in the cubic lattice. WC, despite its hexagonal structure, also exhibits high hardness (2000–2400 HV) due to its unique type of chemical bonding with a partial metallic character. The HV30 macrohardness of the five-component WC-TiC-TaC-HfC-ZrC system (2008 HV) is at the lower end of the range for individual carbides, which can be considered a good result given the relatively low sintering temperature and the presence of residual porosity. The four-component system demonstrates lower macrohardness (1632 HV) but higher microhardness (1860 HV), indicating microstructural heterogeneity with local high-hardness regions.

Comparison with high-entropy carbides from the literature shows that systems based on TiZrHfNbTa, sintered at higher temperatures (2000–2100 °C), exhibit significantly higher hardness values (2550–2850 HV) and relative density (98–99%). This confirms that optimizing the sintering time-temperature parameters by increasing the temperature to 2000–2100 °C is required to achieve the maximum mechanical characteristics of high-entropy carbides. However, it should be noted that the systems from the literature do not contain WC, which has the lowest melting point (2870 °C) among the studied carbides and may limit the maximum processing temperature.

An important advantage of high-entropy carbides over monolithic ones is their potentially higher thermal stability and oxidation resistance at high temperatures due to the entropic stabilization effect and the formation of protective multi-component oxide layers. Literature data show that (TiZrHfNbTa)C retains a stable single-phase structure up to 2400 °C, while monolithic carbides may undergo phase transformations or evaporation at temperatures above 2000–2200 °C.

The fracture toughness of monolithic carbides varies in the range of 2.0–5.5 MPa·m1/2, with WC and TaC exhibiting relatively high values (3.0–5.5 MPa·m1/2), while HfC is characterized by lower toughness (2.0–3.0 MPa·m1/2). Literature data for the high-entropy carbide (TiZrHfNbTa)C show a fracture toughness of 3.2–4.1 MPa·m1/2, which is comparable to the best monolithic carbides. Unfortunately, within the scope of this study, we did not perform fracture toughness measurements for our systems, which is an important prospect for future research. It can be assumed that the presence of WC with its relatively high toughness and the formation of a fine-grained structure may contribute to increased crack resistance of the synthesized HEC materials.

Thus, the comparative analysis shows that the synthesized high-entropy carbides WC-TiC-TaC-HfC and WC-TiC-TaC-HfC-ZrC exhibit properties comparable to individual monolithic carbides, while possessing potential advantages in thermal stability and the possibility of tailored property design through composition variation. To achieve characteristics comparable to the best HEC systems reported in the literature, further optimization of the sintering regimes is required, involving an increase in temperature to 2000–2100 °C and a reduction in the oxide phase content.

3.7. Practical Applications and Technological Advantages of the Synthesized High-Entropy Carbides

The synthesized WC-TiC-TaC-HfC and WC-TiC-TaC-HfC-ZrC high-entropy carbides possess a combination of properties that make them promising for high-tech applications under extreme conditions. The achieved macrohardness of HV30 = 2008 for the five-component system is comparable to traditional WC-Co hard metals (1400–1800 HV) but is achieved without a metallic binder, which ensures potentially higher thermal stability at cutting temperatures above 700–800 °C, where cobalt softens. The presence of WC in the high-entropy solid solution is critically important, as WC is the primary wear-resistant component in traditional hard metals, and this work demonstrates the possibility of its complete incorporation into the cubic carbide matrix. For high-temperature structural materials and thermal protection coatings, the ability of high-entropy carbides to maintain a stable single-phase structure up to 2400–2600 °C and their low thermal conductivity due to phonon scattering on local lattice distortions (ε = 5.18–5.81 × 10−3) are crucial for thermal barrier coatings on gas turbine blades. In nuclear energy, the enhanced radiation resistance afforded by the entropy stabilization effect makes high-entropy carbides promising as inert matrices for dispersed fuel or protective coatings for fuel elements, while the high density of the WC-containing systems (10–11 g/cm3) provides effective radiation shielding for spent fuel storage containers.

A critical achievement is the successful incorporation of WC into the high-entropy system, as most literature focuses on Ti-Zr-Hf-Nb-Ta systems, avoiding WC due to crystal structure incompatibility (hexagonal vs. cubic). The complete absence of hexagonal WC reflections on the diffraction patterns of the consolidated samples confirms the incorporation of tungsten into the cubic lattice, which expands the compositional space of high-entropy carbides and opens avenues for property optimization by varying the WC content. Tungsten, with its melting point of 3422 °C, density of 19.25 g/cm3, and relatively good thermal conductivity, provides WC-containing systems with a unique combination of thermal stability, radiation protection, and efficient heat dissipation.

The developed approach, combining mechanical activation with SPS, offers significant technological advantages for industrial scaling. Mechanical activation provides a homogeneous, fine-grained mixture (>95% of particles <10 µm) with high reactivity, while SPS enables rapid consolidation (~30–40 min versus 2–4 h for hot pressing), minimizing grain growth and energy consumption. The demonstrated possibility of homogenization at a relatively lower temperature (1900 °C versus 2000–2200 °C reported in the literature) opens prospects for using cheaper precursors (mixtures of elemental metal powders and carbon) with in situ reactive synthesis, which would significantly reduce production costs. The reproducibility of the process, due to precise parameter control and real-time monitoring, ensures consistent product quality, which is critical for industrial applications.

Detailed investigation of the atomic structure and elemental distribution by high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) with elemental mapping (STEM-EDS) and, where possible, atom probe tomography to identify potential nanoscale compositional inhomogeneities, assess the degree of local atomic ordering, and study the structure of intergranular boundaries.

4. Conclusions

In this work, medium- and high-entropy carbide systems with compositions WC-TiC-TaC-HfC and WC-TiC-TaC-HfC-ZrC were successfully synthesized using a combination of mechanical activation and spark plasma sintering at 1900 °C. The following principal findings have been established:

- Mechanical activation via HEBM transforms the initial polyfractional system (0.1–1100 µm) into a homogeneous fine-dispersed mixture with a distribution maximum at 1–2 µm, with over 95% of particles concentrated in the <10 µm range. X-ray phase analysis confirmed the preservation of individual carbide phases without chemical interaction, with minor changes in lattice parameters (0.01–0.09%).

- Consolidation of both systems proceeds via a single-stage solid-state sintering mechanism within the temperature range of 1316–1825 °C. The introduction of ZrC leads to a 22% reduction in shrinkage rate (from 0.9 to 0.7 mm·min−1), which is attributed to the manifestation of the sluggish diffusion effect in the high-entropy system.

- After sintering, single-phase high-entropy solid solutions (W-Ti-Ta-Hf)C and (W-Ti-Ta-Hf-Zr)C with a cubic Fm-3m structure and lattice parameters of 4.4101 Å and 4.4604 Å, respectively, are formed. EDS confirms a near-equimolar distribution of components with deviations not exceeding ±1.9 at. %. The introduction of ZrC increases the average crystallite size by 84.3% (from 83.5 to 153.1 nm).

- Both systems achieve a relative density of ~91.75%, yet exhibit differences in hardness distribution. The four-component system is characterized by a higher average microhardness (1860 HV), while the five-component system exhibits a higher macrohardness HV30 (2008.1). The residual content of the HfO2 oxide phase is 4–7 wt. %.

The established patterns of phase formation and microstructure development demonstrate the feasibility of synthesizing high-entropy carbides with controlled properties and open prospects for creating a new class of multicomponent ceramic materials with improved performance characteristics for high-temperature applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.Y.B. and A.A.B. (Anton A. Belov); methodology, I.Y.B. and A.O.L.; validation, A.O.L., O.O.S. and E.K.P.; formal analysis, A.A.B. (Anton A. Belov); investigation, A.O.L., S.M.P., E.A.P., E.S.K., N.S.O., A.A.B. (Anastasia A. Buravleva) and A.N.F.; resources, I.Y.B.; data curation, A.O.L.; writing—original draft preparation, I.Y.B. and A.A.B. (Anton A. Belov); writing—review and editing, I.Y.B.; visualization, A.A.B. (Anton A. Belov) and I.Y.B.; supervision, E.K.P.; project administration, I.Y.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by the Russian Science Foundation grant No. 25-23-00578, https://rscf.ru/project/25-23-00578/ (accessed on 23 November 2025). The equipment of the joint Center for collective use, the interdisciplinary center in the field of nanotechnology, and new functional materials of the FEFU were used in the work (Vladivostok, Russia).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research does not include human or animal participants. This study follows institutional protocols for research concerning dental materials.

Data Availability Statement

The experimental data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fu, H.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhong, Z.; Liang, Z.; Wang, S.; Du, Y.; Yan, C. High-Entropy Rare Earth Materials: Synthesis, Application and Outlook. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 2211–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweidler, S.; Botros, M.; Strauss, F.; Wang, Q.; Ma, Y.; Velasco, L.; Cadilha Marques, G.; Sarkar, A.; Kübel, C.; Hahn, H.; et al. High-Entropy Materials for Energy and Electronic Applications. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2024, 9, 266–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bataeva, Z.; Ruktuev, A.; Ivanov, I.; Yurgin, A.; Bataev, I. Review of Alloys Developed Using the Entropy Approach. Met. Work. Mater. Sci. 2021, 23, 116–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.Z.; Reece, M.J. Review of High Entropy Ceramics: Design, Synthesis, Structure and Properties. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 22148–22162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.; Liu, X.; Wang, H.; Wu, Y.; Jiang, S.; Lu, Z. Development of Advanced Materials via Entropy Engineering. Scr. Mater. 2019, 165, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murty, B.S.; Yeh, J.W.; Ranganathan, S.; Bhattacharjee, P.P.; George, E.P.; Raabe, D.; Ritchie, R.O. High-Entropy Alloys; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 4, ISBN 9780128160688. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington, T.J.; Gild, J.; Sarker, P.; Toher, C.; Rost, C.M.; Dippo, O.F.; McElfresh, C.; Kaufmann, K.; Marin, E.; Borowski, L.; et al. Phase Stability and Mechanical Properties of Novel High Entropy Transition Metal Carbides. Acta Mater. 2019, 166, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gild, J.; Braun, J.; Kaufmann, K.; Marin, E.; Harrington, T.; Hopkins, P.; Vecchio, K.; Luo, J. A High-Entropy Silicide: (Mo0.2Nb0.2Ta0.2Ti0.2W0.2)Si2. J. Mater. 2019, 5, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Z.B.; Sun, S.K.; Guo, W.M.; Chen, Q.S.; Qiu, J.X.; Plucknett, K.; Lin, H.T. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of High-Entropy Borides Derived from Boro/Carbothermal Reduction. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2019, 39, 3920–3924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, B.; Wen, T.; Liu, D.; Chu, Y. Oxidation Behavior of (Hf0.2Zr0.2Ta0.2Nb0.2Ti0.2)C High-Entropy Ceramics at 1073–1473 K in Air. Corros. Sci. 2019, 153, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, B.; Wen, T.; Chu, Y. High-Temperature Oxidation Behavior of (Hf0.2Zr0.2Ta0.2Nb0.2Ti0.2)C High-Entropy Ceramics in Air. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2020, 103, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Milisavljevic, I.; Grzeszkiewicz, K.; Stachowiak, P.; Hreniak, D.; Wu, Y. New Optical Ceramics: High-Entropy Sesquioxide X2O3 Multi-Wavelength Emission Phosphor Transparent Ceramics. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 41, 3621–3628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Zhu, J.; Zhu, S.; Zhao, Y.; Li, M.; Huang, Z.; Wang, H.; He, J. Design Strategies for Perovskite-Type High-Entropy Oxides with Applications in Optics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 47475–47486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Pu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Ouyang, T.; Ji, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, C.; Sun, S.; Sun, R.; Li, J.; et al. Dielectric Temperature Stability and Energy Storage Performance of NBT-Based Ceramics by Introducing High-Entropy Oxide. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2022, 105, 4796–4804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, K.; Wang, B.W.; Sun, Z.P.; Li, W.; Jin, C.C.; Zhang, S.M.; Xu, S.Y.; Guo, L.; Mao, Y. Frist-Principles Prediction of Elastic, Electronic, and Thermodynamic Properties of High Entropy Carbide Ceramic (TiZrNbTa)C. Rare Met. 2022, 41, 1002–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Yang, Y.; Chen, D.; Zhang, Y.; Meng, Y. Micro-Structural and Magnetic Analysis of Spinel High Entropy Oxides Synthesized by Two-Step Pressureless Sintering Provides Insight into High Entropy Ceramics. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 35, 106122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Wen, Z.; Ma, B.; Wu, Z.; Lv, Y.; Yu, J.; Zhao, Y. Microstructure and Magnetic Properties of Novel High-Entropy Perovskite Ceramics (Gd0.2La0.2Nd0.2Sm0.2Y0.2)MnO3. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2024, 597, 172010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Yang, Y.; Chen, C.; Meng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C. Structure and Magnetism of Novel High-Entropy Rare-Earth Iron Garnet Ceramics. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 9862–9867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Li, Z.; Li, L.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, R.; Ma, C. Microstructures and Oxidation Mechanisms of (Zr0.2Hf0.2Ta0.2Nb0.2Ti0.2)B2 High-Entropy Ceramic. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2022, 42, 2127–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]