Abstract

Understanding how the surface charge environment governs pollutant–catalyst interactions is essential for designing efficient photocatalysts. In this study, ZnO–CeO2–WO3 composite materials were synthesized through a simplex-centroid mixture design to evaluate their photocatalytic activity toward the degradation of 4-nitrophenol (4-NPOH) under UV irradiation. The materials were characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD), Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), UV–Vis diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (DRS), photoluminescence (PL), nitrogen adsorption–desorption (BET/DFT) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Photocatalytic experiments were conducted without pH adjustment to analyze the intrinsic behavior of each oxide and their mixtures. The acid–base equilibrium of 4-NPOH (pKa = 7.2) allowed evaluating its deprotonation to 4-nitrophenolate (4-NP−) and its interaction with the catalyst surface, which depends on the point of zero charge (pHPzc) of ZnO, CeO2, and WO3. The Zn–W binary system (ZnWO4 phase) exhibited the highest activity, achieving 81% degradation efficiency and the largest apparent rate constant (k = 5.1 × 10−3 min−1). However, a 51% decrease in activity was observed after three reuse cycles, attributed to WO3 leaching induced by the interaction between 4-NPO− and zinc tungstate hydroxide (Zn[W(OH)8]). This work establishes a direct correlation between surface charge, pollutant speciation, and photocatalytic performance, providing a mechanistic framework for understanding pH-dependent degradation processes over multicomponent oxide composites.

1. Introduction

4-Nitrophenol (4-NP) is an aromatic compound widely used as an intermediate in the synthesis of pesticides, dyes, and pharmaceutical products []. Due to its high chemical stability associated with the nitro group (–NO2), it exhibits low biodegradability and considerable toxicity []. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA, 1992) classifies 4-NP as a priority pollutant, establishing a maximum allowable concentration of 10 ng L−1 in natural waters. Prolonged exposure to 4-NP can cause neurological and hematological disorders and may alter metabolic processes in aquatic organisms [].

Several techniques have been employed for the removal of 4-NP from wastewater, including adsorption, advanced oxidation processes (AOPs), biodegradation, and electrochemical treatments. Adsorption is often a fast and inexpensive technique; however, its efficiency depends on the material’s adsorption capacity and does not guarantee complete degradation of the contaminant []. AOPs, based on the generation of hydroxyl and sulfate radicals, have demonstrated a high ability to mineralize organic compounds, although they involve high operational costs and may produce secondary by-products [,]. Biological processes using bacterial strains such as Pseudomonas sp. have shown effectiveness in phenol degradation, yet their practical application is limited by operational sensitivity and long treatment times []. Similarly, electrochemical methods combined with AOPs have achieved high 4-NP removal efficiencies but suffer from high energy consumption and partial degradation of the pollutant [,].

In this context, heterogeneous photocatalysis emerges as a sustainable and efficient alternative capable of mineralizing organic pollutants under UV and visible light through the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as •OH, O2•−, and H2O2 [,,]. The photocatalytic degradation efficiency of 4-NP depends on several parameters, including the initial pH [], pollutant concentration [], catalyst concentration [], irradiation time, and the characteristics of the light source. According to Akhtar et al. [], the use of a 36 W mercury vapor lamp (λ ≈ 365 nm, irradiance ≈ 1.1 W m−2) provides near-UV emission within 320–400 nm, favoring the excitation of wide-bandgap oxides such as ZnO and WO3. The authors demonstrated that both the emission spectrum and irradiation time strongly influence the degradation rate of aromatic pollutants. In contrast, Das et al. [] reported photocatalytic experiments under simulated solar (680 W m−2) and visible-light (180 W m−2) irradiances for ZnO–CeO2 heterojunctions, emphasizing that variations in photon flux significantly affect reaction kinetics and charge-transfer efficiency. The pH not only influences the speciation of 4-NP but is also related to the surface charge of the catalyst, defined by its point of zero charge (pHpzc), which governs the electrostatic interactions between the catalytic surface and the molecules in solution [].

Recent studies have highlighted the importance of correlating the surface properties of materials with their photocatalytic performance, as this approach allows a better understanding of the adsorption and oxidation mechanisms involved []. This relationship has been confirmed in BiOI-based photocatalysts, where optimal activity occurs when the reaction pH is close to the pHpzc, maximizing adsorption and reaction efficiency []. Likewise, in kaolin-supported ZnO, the interaction with pollutants strongly depends on the proximity between the reaction pH and the material’s pHpzc []. However, most studies only describe this correlation qualitatively, without experimentally distinguishing the specific influence of pHpzc and pollutant speciation on photocatalytic behavior.

These investigations demonstrate that adsorption and degradation processes are governed by the balance between the pollutant’s speciation and the surface charge of the catalyst. The pHpzc regulates the density of surface hydroxyl groups, which are crucial for the generation of hydroxyl radicals (•OH)—key species in the degradation of nitroaromatic compounds []. Consequently, the initial pH of the medium and the pHpzc of the material jointly define the optimal conditions for photocatalytic efficiency [,,,,]. Nevertheless, the individual contribution of each oxide’s surface chemistry to the overall photocatalytic behavior of multicomponent systems remains poorly understood. In particular, the combined effect of ZnO, CeO2, and WO3—materials with distinct acid-base and electronic properties—offers a unique framework to explore how pHpzc-driven interactions influence pollutant degradation under near-neutral conditions.

In this regard, the present work addresses the photodegradation of 4-NP without adjusting the pH of the reaction medium, aiming to analyze the intrinsic photocatalytic behavior of individual oxides (ZnO, CeO2, and WO3), as well as their binary and ternary mixtures synthesized by combining their precursors. In this study, the point of zero charge (pHpzc) is employed as a qualitative parameter of the effective surface charge of the catalysts, establishing a direct link between surface charge polarity and the adsorption–deprotonation behavior of 4-NP. The discussion focuses on proposing 4-NP as a probe molecule suitable for exploring the influence of the point of zero charge (pHpzc) of photocatalytic materials on their performance and on the contaminant–surface interactions under near-neutral conditions. This approach provides a novel framework for understanding how the surface charge environment governs pollutant speciation and degradation efficiency, offering a new perspective to correlate the pHpzc with photocatalytic behavior.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

All reagents were of analytical grade and were used without any further purification: zinc nitrate hexahydrate (99%, Sigma-Aldrich (St. Luois, MO, USA)), cerium (III) nitrate hexahydrate (99%, Sigma-Aldrich (St. Luois, MO, USA)), ammonium tungstate (99.99%, Merck, Elkton, MD, USA), and ethanol (99.9%, Merck). All experiments were carried out using ultrapure water (18.2 MΩ·cm−1) obtained from a PureLab Option-Q, ELGA LabWater (Woodridge, IL, USA).

2.2. Mixture Design of Experiments

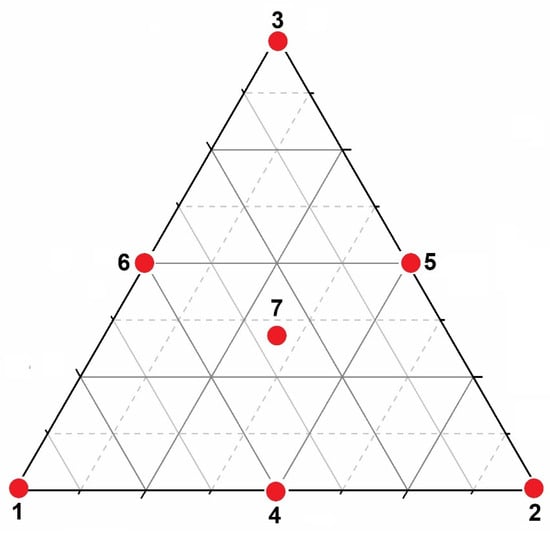

For material optimization, a mixture surface response (MSR) was constructed using three independent variables corresponding to the possible molar proportions for the synthesis of the catalysts. The statistical analysis was performed using Statistica 12.0® (StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA). The catalyst compositions were obtained according to the simplex-centroid mixture design, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Simplex-centroid mixture design with three factors at three levels, corresponding to zinc nitrate, cerium nitrate, and ammonium tungstate. The red numbered points represent the seven experimental formulations generated by the design: points 1–3 correspond to the pure components (vertices), points 4–6 represent the binary mixtures located along the edges, and point 7 denotes the ternary mixture containing the three components simultaneously.

Samples 1–3 represent the vertices in the ternary diagram, corresponding to the individual oxides. Samples 4–6 represent the binary mixtures located along the edges of the triangle, whereas sample 7 corresponds to the ternary composition. To evaluate experimental variation at the same compositional point, sample 7 was synthesized in triplicate. The detailed compositions and corresponding sample codes are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Percentage composition, mass, and sample codes of the synthesized catalysts.

2.3. Synthesis of the Materials

The corresponding amounts of precursor salts were dissolved in a 1:1 (v/v) ethanol–water solution and kept under magnetic stirring at 500 rpm for 1 h. The solvent was then evaporated in an oven (ICB, Guadalajara, Mexico) at 85 °C for 24 h. Each dried solid was finely ground in an agate mortar, and the resulting powder was placed in an alumina crucible for thermal treatment. The samples were calcined following a heating ramp of 2 °C min−1 up to 500 °C, maintaining this temperature for 6 h.

2.4. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

X-ray diffraction patterns were recorded on a D2 PHASER diffractometer (Bruker, Karlsurhe, Germany) using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.179 nm). The data were collected over a 2θ range of 20–80° with an acquisition time of 660 s. Phase identification was performed using the JADE 6 database. The average crystallite size of the catalysts was estimated using the Sherrer method.

2.5. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR)

FT-IR spectra were obtained using a PerkinElmer UATR Two™ spectrometer (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) equipped with an attenuated total reflectance (ATR) diamond crystal. The spectra were collected in the 4000–400 cm−1 range with a spectral resolution of 4 cm−1. A small number of samples were placed on a Hastelloy plate and pressed with a metal tip to ensure adequate contact with the crystal surface.

2.6. UV–Vis Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy (DRS)

Diffuse reflectance UV–Vis spectra were recorded on a Varian Cary 300 spectrophotometer (Varian, Palo Alto, CA, USA) equipped with an integrating sphere over the wavelength range of 200–800 nm. BaSO4 with 100% reflectance was used as a reference. The optical band gap energy (Eg) of the samples was estimated from the absorption spectra according to the relation:

where is the absorption coefficient for photons of energy , and the exponent m was set to 1 or 4 depending on the nature of the electronic transition, corresponding to indirect and direct allowed transitions, respectively. The linear region was selected by maximizing the correlation coefficient, preferring fits with 0.999.

2.7. Photoluminescence (PL) Spectroscopy

Photoluminescence (PL) spectra of the solid samples were obtained using a NanoLog® spectrometer (HORIBA Jobin Yvon, Longjumeau, France) equipped with a 450 W Xe lamp and an excitation monochromator operating between 200 and 600 nm. The excitation wavelength (λex) was selected individually for each catalyst. The samples were prepared at room temperature by compacting the powder into a stainless-steel sample cell previously cleaned with acetone. The cell was then placed in the sample holder module for measurement. Photoluminescence spectra were recorded at room temperature in the 350–650 nm range, which was selected to capture the near-band-edge and visible defect-related emissions of the oxide semiconductors studied.

2.8. Nitrogen Adsorption–Desorption Isotherms

The specific surface area, pore diameter, and pore volume of the catalysts were determined by nitrogen physisorption using a TriStar II 3020 surface area analyzer (Micromeritics Intrument Corp., Norcross, GA, USA) at 77 K (−196 °C). Prior to measurement, approximately 0.1 g of sample was degassed at 300 °C for 3 h to remove adsorbed impurities. The adsorption data were analyzed using the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method, and the pore size distribution was obtained by the density functional theory (DFT) model.

2.9. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

The morphology of the samples was examined using a MAIA3 UDLAP (TESCAN, Brno, Czech Republic) high-resolution scanning electron microscope equipped with an In-Beam SE detector (TESCAN, Brno, Czech Republic), operated at magnifications corresponding to 20 μm and 5 μm scale bars. Each sample was mounted on a 3.2 mm stainless-steel pin stub using conductive carbon tape. Excess powder was gently removed with a rubber air bulb to ensure a clean surface prior to imaging.

2.10. Photocatalytic Activity Test

Photocatalytic degradation experiments were carried out in a photochemical reactor equipped with UV irradiation (λ = 365 nm) provided by a 25 W mercury lamp. The incident radiation intensity measured at the liquid surface was 5.2 mW cm−2, as determined using a radiometer (Ohm HD2102.2) (Delta OHM S.r.l, Pauda, Italy). The photocatalyst (0.1 g L−1) was dispersed in 200 mL of an aqueous 4-nitrophenol (4-NP) solution (15 mg L−1) under natural pH conditions. Air was continuously supplied at a flow rate of 3.2 L min−1, providing a dissolved oxygen concentration of approximately 8.4 mg L−1, measured using a portable oximeter (YSI 550A) (YSI Inc., Yellow Springs, OH, USA). Prior to illumination, the suspension was stirred in the dark for 60 min at 700 rpm to establish adsorption–desorption equilibrium between the photocatalyst and the contaminant. The system was maintained at room temperature using circulating cooling water and enclosed within a UV-protected dark box (constructed in-house). During irradiation, 3 mL aliquots of the suspension were withdrawn at specific intervals, filtered through 0.45 µm nylon membranes, and analyzed by UV–Vis spectrophotometry (Varian Cary 300) (Varian, Palo Alto, CA, USA). to determine the residual concentration of 4-NP. The degradation efficiency (x %) was calculated using the following expression:

where [4 − NP°] (mg L−1) is the initial concentration at the onset of illumination, and [4 − NP] (mg L−1) is the concentration after 6 h of irradiation.

2.11. Scavenger Tests

To identify the main reactive species involved in the photocatalytic degradation of 4-nitrophenol, additional experiments were performed by introducing selective scavengers under identical reaction conditions. Benzoquinone (BQ), ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), and isopropanol (IPA) were used as quenchers of superoxide radicals (•O2−), photogenerated holes (h+), and hydroxyl radicals (•OH), respectively. The initial molar concentration of each scavenger was adjusted to be equivalent to that of 4-NP (1.08 × 10−4 mol L−1), maintaining a 1:1 molar ratio between the contaminant and the scavenger. The photocatalytic tests were carried out using 0.1 g L−1 of catalyst under UV irradiation (λ = 365 nm, 25 W Hg lamp) at natural pH. The degradation of 4-NP was monitored by UV–Vis spectrophotometry at λmax = 317–400 nm, depending on its protonation state. Changes in the degradation rate of 4-NP in the presence of each scavenger were used to infer the predominant reactive species, following the approach reported by Nugroho et al. [].

2.12. Reusability Cycles

The stability and reusability of the photocatalysts were evaluated through consecutive photodegradation cycles of 4-nitrophenol under identical experimental conditions. After each photocatalytic run (4 h of irradiation), the catalyst was recovered by centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 10 min, thoroughly washed three times with deionized water and once with ethanol to remove adsorbed residues, and then dried at 60 °C for 12 h. The dried powder was reused directly in the following cycle without any additional treatment. For each cycle, 200 mL of 4-NP solution (15 mg L−1) containing 0.1 g L−1 of photocatalyst was irradiated under UV light (λ = 365 nm, 25 W mercury lamp) while keeping all parameters constant (pH, air flow = 3.2 L min−1, and stirring = 700 rpm). The degradation efficiency was calculated using Equation (2). Structural stability was further evaluated by comparing the FT-IR spectra (PerkinElmer, Hopkinton, MA, USA) of the catalysts before and after reuse to detect potential loss of tungsten oxide species.

3. Results and Discussion

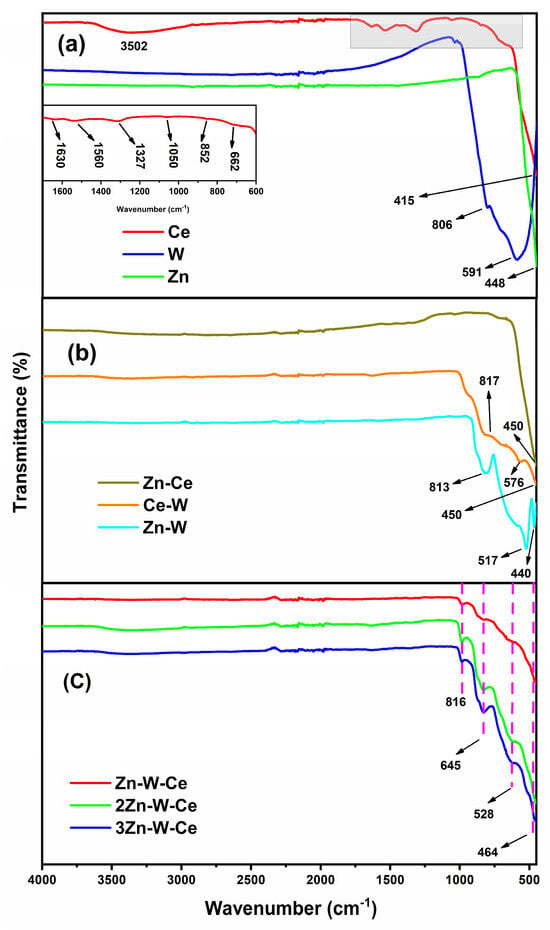

3.1. XRD Analysis

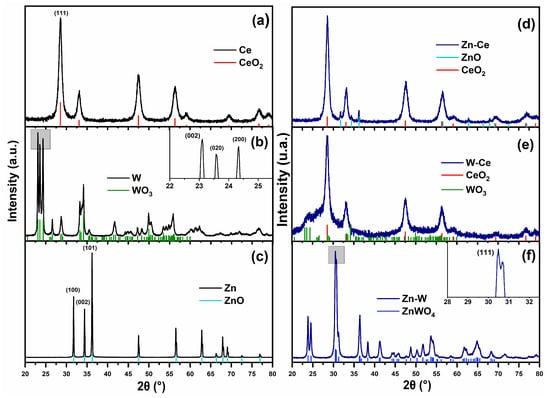

Figure 2 shows the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the individual oxides and the binary mixtures. The Ce sample exhibited reflections corresponding to the (111), (200), (220), (311), (222), (400), and (331) planes, which are characteristic of a face-centered cubic (FCC) fluorite-type structure of cerium oxide (CeO2, PDF# 43-1002) [,], as shown in Figure 2a. For the W sample, the reflections located at (002), (020), and (200) (Figure 2b) indicate a monoclinic crystal structure associated with tungsten oxide (WO3, PDF# 43-1035), which consists of a distorted octahedral arrangement of WO6 units []. In the case of the Zn sample (Figure 2c), reflections at (100), (002), (101), (102), (110), (103), (200), (112), (201), (004), and (202) were identified, confirming a hexagonal wurtzite-type structure corresponding to ZnO (PDF# 36-1451) [,].

Figure 2.

X-ray diffraction patterns of pure oxides: (a) Ce, (b) W, (c) Zn; and binary mixtures: (d) Zn–Ce, (e) W–Ce, (f) Zn–W.

The XRD pattern of the Zn–Ce sample (Figure 2d) revealed the coexistence of CeO2 and ZnO crystalline phases. The crystallite size of ZnO in this mixture was smaller than that of the pure ZnO sample, indicating that the presence of CeO2 inhibited the crystal growth of the ZnO phase. This effect has been reported by Q. Meng et al. [] and is commonly observed in such mixed systems, regardless of the synthesis method or precursor used []. The W–Ce sample (Figure 2e) also exhibited a mixture of phases, predominantly showing reflections associated with CeO2. The crystallite size of WO3 in this binary mixture was reduced compared with the pure oxide, which can also be attributed to the presence of CeO2. According to literature, CeO2 concentrations above 15 wt% suppress the crystallization of secondary phases in binary systems []. Nevertheless, the formation of heterojunctions between CeO2 and WO3 is still possible, as reported by A. Bahadoran et al. []. In the Zn–W system (Figure 2f), the diffraction peaks confirmed the formation of a zinc tungstate (ZnWO4) phase with monoclinic symmetry (PDF# 15-0774), showing diffraction planes at (011), (110), (111), (021), (200), (121), (130), (−221), and (113) []. The formation of ZnWO4 under the present synthesis conditions is noteworthy, since its preparation is typically reported at high temperatures, under acidic or basic pH, and with prolonged thermal treatments. In contrast, the synthesis method employed here allows the formation of ZnWO4 under milder conditions and at a lower cost [].

For the ternary Zn–W–Ce oxide, the XRD pattern revealed the coexistence of crystalline phases corresponding to cerium oxide (CeO2) and zinc tungstate (ZnWO4, PDF# 15-0774), as shown in Figure 3. The three synthesized replicas exhibited consistent diffraction profiles, confirming the reproducibility of the synthesis method. Notably, the diffraction peaks associated with CeO2 (PDF# 43-1002) showed higher intensity, indicating the predominance of this phase within the composite. Furthermore, a reduction in the crystallite size of ZnWO4 was observed in the ternary sample compared with the pure phase, the CeO2 inhibited crystal growth during the calcination process.

Figure 3.

X-ray diffraction patterns of the three replicated Zn–Ce–W samples. (a) Diffractogram of the Zn–W–Ce material, with reference markers for ZnWO4 and CeO2. (b) Diffractogram of sample 2Zn–W–Ce, showing the same crystalline phases and peak positions. (c) Diffractogram of sample 3Zn–W–Ce, confirming the reproducibility of the ternary synthesis.

The average crystallite sizes of the individual oxides, as well as the binary and ternary composites, calculated using the Scherrer equation, are summarized in Table 2. The Zn sample exhibited the largest crystallite size compared with the W- and Ce-based oxides. In the binary composites, the interaction with secondary oxide significantly modified the crystallite size. The combination of Zn and W led to the formation of ZnWO4-type phases with intermediate crystallite sizes relative to the pure oxides. In the W–Ce composite, the crystallites were smaller than those of pure WO3, suggesting that the dispersion of Ce species limited WO3 crystal growth. Conversely, the Zn–Ce sample retained relatively large ZnO crystallites, although a slight reduction in their size was observed, attributed to the surface interaction between ZnO and CeO2. The ternary Zn–W–Ce composites exhibited crystallite sizes in the range of 7–10 nm, smaller than those of any binary system. This reduction indicates that the simultaneous incorporation of Ce and W species more effectively inhibits the growth of ZnWO4 crystallites, resulting in a structure with a higher density of structural defects.

Table 2.

Summary of structural and textural properties of the synthesized materials.

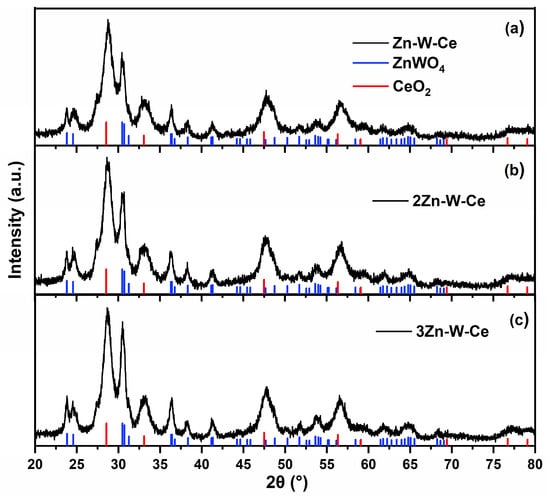

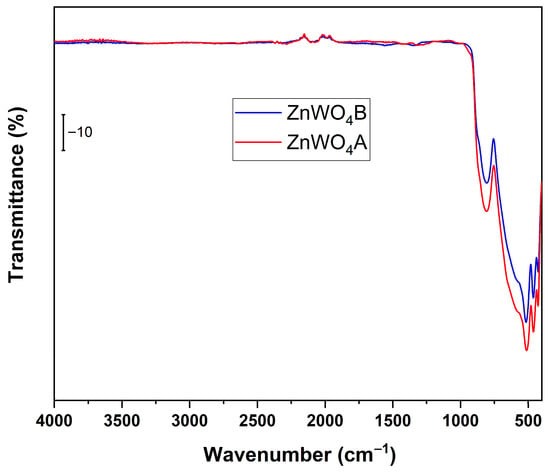

3.2. FT-IR Analysis

Figure 4a shows the FT-IR spectra of the pure oxide samples. The Ce sample exhibited a broad band around 3502 cm−1, attributed to the stretching vibration of surface O–H groups from adsorbed water molecules. This signal, together with the band at 1622 cm−1, corresponding to the bending vibration of the O–H bond, indicates the presence of residual water in the sample, a common feature in cerium oxides regardless of the synthesis route employed [,]. In addition, the bands observed at 852 cm−1 and 662 cm−1 are assigned to phonon vibrations characteristic of CeO2, confirming the formation of the cerium oxide phase. The absorption bands at 1327 cm−1 and 1050 cm−1 are associated with surface carbonate-like species formed upon exposure to atmospheric CO2. Finally, the intense band at 415 cm−1 corresponds to the ν(O–Ce–O) vibration, clearly evidencing the formation of Ce–O bonds in the fluorite crystal lattice []. The infrared spectrum of the Zn sample displays the main absorption features in the 400–1000 cm−1 region, where the characteristic Zn–O vibrations appear. According to literature, a prominent band for ZnO is typically located in the 450–500 cm−1 range, corresponding to Zn–O stretching vibrations. This agrees with the present results, where a distinct absorption band is observed in that region (Figure 4a) []. The absence of additional bands in the 1000–4000 cm−1 range indicates that the material is free of organic residues or other contaminants, which is consistent with previous reports []. The W sample exhibited no absorption bands in the 3000–4000 cm−1 region, indicating the lack of adsorbed water or free –OH groups (Figure 4a). Two intense bands at approximately 591 cm−1 and 806 cm−1 are attributed to the W=O stretching and W–O–W bridging vibrations, respectively, typical of the WO3 structural framework []. These features confirm the formation of a well-defined tungsten oxide lattice.

Figure 4.

FT-IR spectra of pure, binary, and ternary oxide samples. (a) FT-IR spectra of the pure oxides (CeO2, WO3, ZnO), highlighting characteristic O–H, metal–oxygen, and lattice vibration bands. (b) FT-IR spectra of the binary mixtures (Zn–Ce, Ce–W, Zn–W), showing the overlapping metal–oxygen vibrations associated with the corresponding combined oxides. (c) FT-IR spectra of the ternary Zn–W–Ce samples and their replicates, displaying consistent metal–oxygen vibrational bands corresponding to ZnWO4 and CeO2.

Figure 4b shows the infrared spectra of the binary samples. The Zn–Ce sample exhibits an intense band below 1000 cm−1, corresponding to metal–oxygen bond vibrations. Specifically, the bands in the 500–700 cm−1 region are attributed to Ce–O–Ce stretching vibrations of cerium oxide (CeO2), as confirmed by XRD. Additionally, the strong absorption between 400 and 600 cm−1 arises from the Zn–O vibrations characteristic of zinc oxide (ZnO), confirming the coexistence of both crystalline phases in the sample. The Ce–W spectrum displays distinct bands in the 600–800 cm−1 region, assigned to W–O stretching vibrations of tungsten oxide (WO3), while those in the 500–700 cm−1 region correspond to Ce–O vibrations from CeO2. The overlap observed between these signals is expected, due to the similar nature of metal–oxygen bonds in both oxides (Figure 4). The absence of any significant bands in the 3000–4000 cm−1 region indicates that the sample is free of adsorbed water. For the Zn–W sample, several absorption bands appear below 1000 cm−1, particularly within the 700–900 cm−1 range, which are associated with W–O–W bridging vibrations typical of tungstate structures. The signals detected between 400 and 600 cm−1 correspond to Zn–O stretching vibrations, confirming the incorporation of zinc into the material lattice. The lack of broad bands in the 3000–3500 cm−1 range indicates the absence of surface hydroxyl groups or moisture [].

The FT-IR spectra of the Zn–W–Ce, 2Zn–W–Ce, and 3Zn–W–Ce samples are shown in Figure 4c. The three samples exhibit high reproducibility, as the observed bands are consistent across all spectra. The most intense absorptions in the 500–1000 cm−1 region correspond to metal–oxygen vibrations characteristic of both CeO2 and ZnWO4. The band around 816 cm−1 can be attributed to the W–O–W stretching vibration of zinc tungstate, while those at 645 cm−1, 528 cm−1, and 464 cm−1 are assigned to Ce–O stretching modes of cerium oxide. The excellent consistency of these bands among the three samples confirms the high reproducibility of the synthesis process and the uniform formation of ZnWO4 and CeO2 phases.

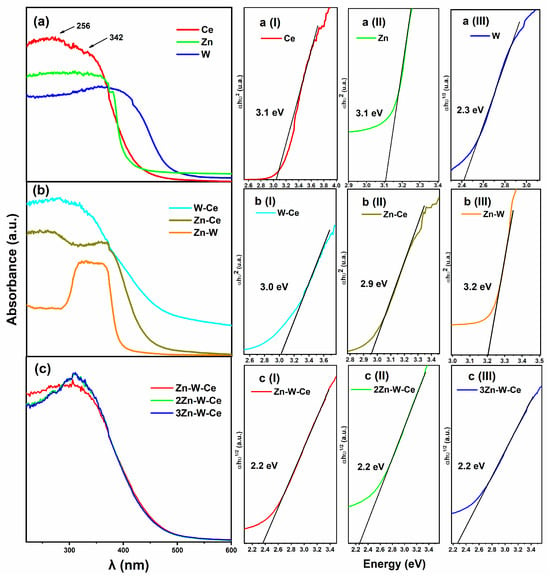

3.3. UV–Vis Analysis

Figure 5a shows the UV–Vis absorption spectra of the pure oxides. The Ce sample exhibited an absorption edge at approximately 480 nm and two additional peaks around 256 nm and 342 nm, which are attributed to charge-transfer transitions involving Ce3+ and Ce4+ species, respectively []. The Zn sample showed an absorption edge near 415 nm [,], indicating strong activity in the ultraviolet region. For the W sample, an absorption edge was observed around 515 nm, with a broad response extending from the visible to the UV region [,]. The optical band gap energies (Eg) for Ce, Zn, and W were determined using the Tauc method [,], as shown in Figure 5a(I–III) and Table 2. The values obtained are consistent with those reported in the literature, confirming the accuracy of the measurements [,,].

Figure 5.

UV–Vis absorption spectra and optical band gap estimation for the pure oxides (a), binary mixtures (b), and ternary samples (c). (a) (I–III): Tauc plots for Ce, Zn, and W, respectively. (b) (I–III): Tauc plots for W–Ce, Zn–Ce, and Zn–W, respectively. (c) (I–III): Tauc plots for Zn–W–Ce, 2Zn–W–Ce, and 3Zn–W–Ce, respectively. Each subfigure (I–III) shows the linear extrapolation used to determine the optical band gap (Eg) of the material associated with panels (a), (b), or (c). For the W–Ce mixture, the spectrum displayed a red shift of the absorption edge to ~500 nm, along with enhanced UV activity compared to the individual oxides (Figure 5b). This shift is attributed to the incorporation of WO3, which reduces the band gap due to the formation of interfacial energy levels between W and Ce species. In the case of the Zn–Ce system, the absorption edge appeared around 500 nm, with distinct bands at 256 nm and 362 nm (Figure 5b). These signals are related to the interaction between CeO2 and ZnO, suggesting efficient charge transfer between both oxides while excluding the formation of a solid solution [,].

For the Zn–W mixture, the UV–Vis spectrum exhibited a peculiar absorption profile, with an absorption range between ~313 and ~368 nm and an absorption edge near ~400 nm. Although this edge is dominated by the contribution of the ZnO component, it is noteworthy that ZnWO4 synthesized by precipitation–calcination routes can also display optical band-gap values in the 3.2–3.3 eV range, instead of the commonly reported 4.5–4.7 eV. This behavior has been documented by Liu et al., who attribute the reduced band gap to synthesis-dependent structural disorder and defect-related electronic states. Therefore, the optical response observed in our Zn–W sample is consistent with previous reports and reflects the combined contributions of ZnO and structurally modified ZnWO4 [,]

The spectra for Zn-W-Ce and its replicas 2Zn-W-Ce and 3Zn-W-Ce, along with the band gap values for each ternary sample, are presented in Figure 5c. These values decreased significantly compared to ZnWO4 and CeO2. An absorption edge at ~500 nm was observed, along with bands at ~264 nm and ~328 nm corresponding to charge transfer transitions of Ce3+ and Ce4+. The UV-Vis spectra of the ternary samples Zn-W-Ce, 2Zn-W-Ce, and 3Zn-W-Ce exhibit highly similar behavior, with an absorption edge around ~500 nm, indicating activation in the visible region (Figure 5c). This is characteristic of systems with allowed transitions in metal oxide materials such as ZnWO4 and CeO2. The reproducibility among the three samples is remarkable, as their spectra almost entirely overlap, demonstrating consistency in the synthesis process. The band gap values of the ternary samples are lower compared to ZnWO4 and CeO2, suggesting that the combination of these oxides promotes band gap reduction, thereby enhancing absorption in the visible range.

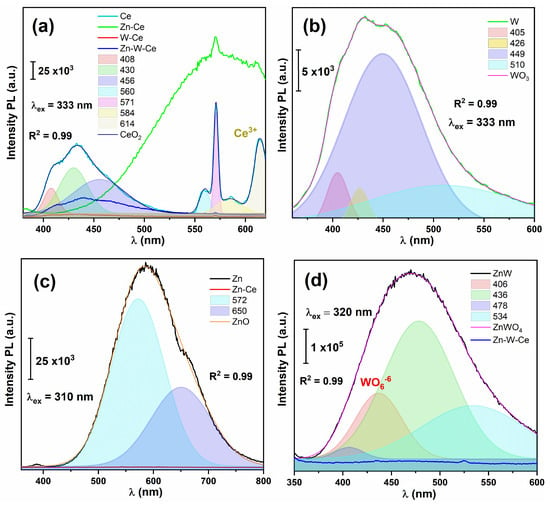

3.4. Photoluminescence (PL) Analysis

The photoluminescence (PL) technique is based on the emission of light from a material upon excitation by an external light source. This emission depends on the electronic and structural properties of the semiconductor. In this study, PL spectroscopy was employed to investigate zinc oxide (ZnO), cerium oxide (CeO2), and tungsten oxide (WO3), as well as their binary and ternary mixtures. To evaluate the emission behavior of each component, the PL spectra were grouped according to the excitation wavelength corresponding to the main absorption edge of each oxide. This approach allowed direct comparison of how all samples—pure, binary, and ternary—respond under the same excitation conditions.

Figure 6a shows the PL spectra of all materials recorded under CeO2 excitation (λex = 333 nm). The pure Ce sample exhibited characteristic emission bands centered at approximately 408, 430, 456, 560, 571, 584, and 614 nm. The emissions at ~408, ~560, ~571, and ~584 nm are attributed to defect-related transitions between the Ce 4f level (~3 eV above the valence band) and O 2p states (~1.2 eV), commonly observed in CeO2 systems with a high concentration of oxygen vacancies [,]. The band at ~430 nm corresponds to near-band-edge (NBE) emission [], while the signal at ~456 nm is associated with dislocation-related defects and lattice distortions. Additionally, the broad emissions in the 600–650 nm region originate from Ce3+ 4f → 5d electronic transitions and intrinsic lattice defect states [].

Figure 6.

Photoluminescence spectra of all materials under specific excitation wavelengths. (a) PL spectra of Ce, Zn–Ce, W–Ce, and Zn–W–Ce samples excited at 333 nm, showing emissions associated with Ce3+ and defect-related states. (b) PL response of WO3 and W–Ce samples excited at 333 nm, highlighting transitions associated with WO66− groups and oxygen-vacancy–related defects. (c) PL spectra of ZnO and Zn–Ce samples excited at 310 nm, with deconvolution of near-band-edge (NBE) and deep-level emission (DLE) contributions. (d) PL spectra of ZnWO4 and Zn–W–Ce samples excited at 320 nm, showing intra-octahedral WO66− charge-transfer transitions and defect-related emissions.

The Zn–Ce mixture displayed a broad PL emission, red-shifted compared with pure CeO2, indicating a strong electronic interaction between ZnO and CeO2. This behavior suggests an efficient charge transfer between the two oxides, which alters their optical and photocatalytic properties by suppressing the radiative recombination intensity []. For the W–Ce sample, a remarkably lower PL intensity was observed, implying a reduced radiative recombination of photoexcited electrons and holes. The presence of WO3 enhances charge separation through defect-level interactions between the oxides, generating additional electron–hole trapping sites that suppress PL emission [].

Similarly, the Zn–W–Ce ternary sample exhibited a low PL intensity, indicating a further reduction in radiative recombination compared with the pure oxides. The interaction between zinc tungstate (ZnWO4) and CeO2 promotes effective charge separation, attributed to the alignment of energy levels between ZnWO4 and CeO2, which facilitates interfacial charge transfer and enhances photocatalytic efficiency.

Figure 6b shows the PL spectra of all materials under WO3 excitation. The W sample exhibited emission peaks at 405, 426, 449, and 510 nm. The first peak at 405 nm corresponds to a near-band-edge (NBE) transition involving recombination between the valence-band O 2p states and conduction-band W 5d states []. The bands observed in the 420–480 nm region (426 and 449 nm) arise from defect-assisted electronic transitions associated with oxygen vacancies (VO), sub-stoichiometric W5+ centers, and self-trapped excitons within distorted WO6 octahedra []. The broad contribution around 510 nm is attributed to deeper defect levels related to localized states in the WO3 lattice, also linked to vacancy-induced electronic transitions []. The W–Ce sample exhibited lower PL intensity than pure WO3, indicating that the incorporation of CeO2 effectively reduces radiative recombination of charge carriers; however, this quenching does not necessarily imply an increase in photocatalytic efficiency during contaminant degradation [].

Figure 6c presents the PL spectra of the Zn-containing materials excited at 310 nm. The pure ZnO sample exhibited a strong and broad emission centered around 600 nm, which can be deconvoluted into two main components located at approximately 572 nm and 650 nm. The band at ~572 nm is assigned to an excitonic near-band-edge (NBE) transition involving the recombination of electrons from Zn 4s/4p conduction-band states with holes in O 2p valence-band states, assisted by shallow surface defects [,,]. The emission at ~650 nm originates from deep-level electronic transitions associated with intrinsic lattice defects, mainly oxygen vacancies (VO), zinc interstitials (Zni), and related defect complexes that introduce sub-bandgap states within ZnO [,,]. The relatively high intensity of these defect-mediated transitions reflects the abundance of radiative recombination centers and the high crystallinity of ZnO. For the Zn–Ce sample, a notable decrease in PL intensity was observed compared with pure ZnO. This reduction indicates improved charge-carrier separation and suppressed electron–hole recombination. Such behavior suggests that the interaction between ZnO and CeO2 enhances the material’s ability to generate and transfer charge carriers more efficiently [].

Figure 6d displays the PL spectra of the ZnWO4-containing materials excited at 320 nm. The Zn–W binary system exhibited a broad emission band centered near 470 nm, which can be deconvoluted into components at approximately 406, 436, 478, and 534 nm. These emissions correspond to well-known intra-octahedral charge-transfer transitions within the [WO6]6− units—specifically electronic transitions from oxygen 2p → tungsten 5d states—characteristic of tungstate-based materials [,,]. The broad character and relatively high intensity of these bands indicate the presence of multiple radiative pathways involving structural distortions, oxygen-vacancy centers VO and defect-related recombination channels within the ZnWO4 lattice.

In contrast, the ternary Zn–W–Ce sample exhibited a pronounced suppression of PL intensity across the entire visible range. The deconvoluted spectrum shows a strong attenuation of the 406 and 436 nm components, while the remaining bands became significantly weaker. This behavior suggests that the incorporation of CeO2 modifies the local electronic environment of the [WO6]6− octahedra and introduces additional interfacial electron-transfer pathways, which effectively compete with radiative recombination. As a result, charge carriers generated within ZnWO4 are more efficiently transferred toward CeO2, promoting non-radiative interfacial charge separation and leading to the observed PL quenching.

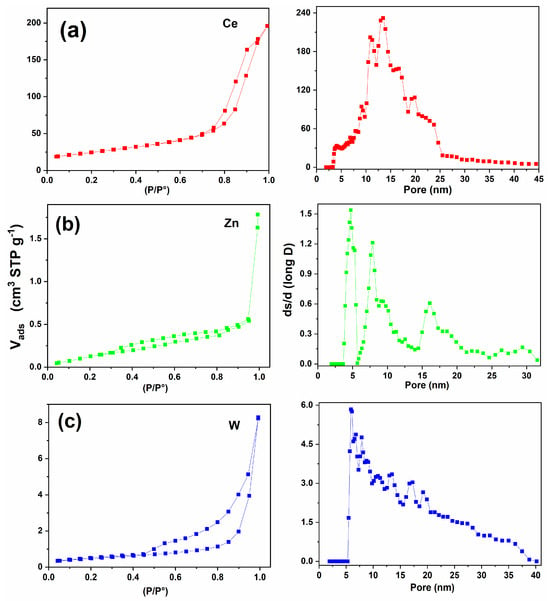

3.5. Nitrogen Adsorption–Desorption Isotherms Analysis

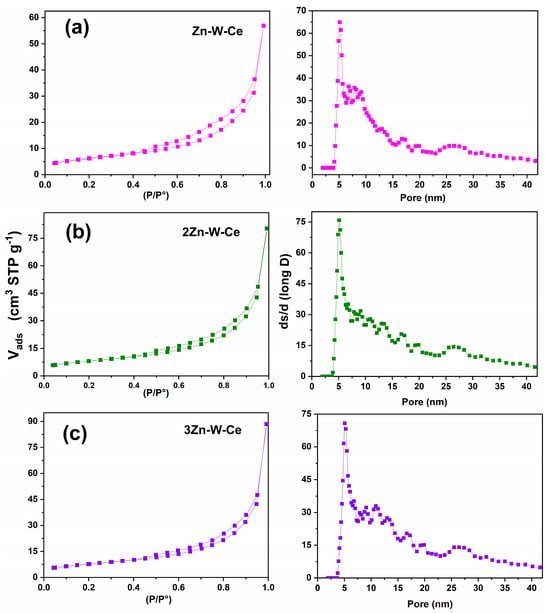

The nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms of the synthesized oxides and their composites are presented in Figure 7, and the corresponding textural parameters are summarized in Table 2. All materials exhibited type IV isotherms with distinct hysteresis loops, confirming their mesoporous nature according to the IUPAC classification [].

Figure 7.

Nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms (left column) and corresponding pore size distributions (right column) for the individual oxides: (a) Ce: (left) type-IV isotherm with H3 hysteresis; (right) mesopore distribution centered around 10–20 nm. (b) Zn: (left) type-IV isotherm with moderate hysteresis; (right) multimodal mesopore distribution with maxima near 5–12 nm. (c) W: (left) type-IV isotherm with pronounced H3 hysteresis; (right) broad mesopore distribution extending from approximately 5 to 35 nm.

The shape of the hysteresis loops varied significantly among the materials, revealing the influence of the oxide composition on pore structure. The CeO2 sample showed an H3-type loop, attributed to slit-shaped pores formed by the stacking of plate-like particles (Figure 7a). WO3 exhibited an H4-type loop, commonly associated with narrow slit pores and partial microporosity (Figure 7c), while ZnO presented an H2-type loop related to ink-bottle pores with restricted necks (Figure 7b).

The pure oxides exhibit mesoporous distributions mainly below 20 nm. CeO2 presents a broad distribution centered at ~15–25 nm, which is typical of ceria nanoparticle agglomerates. ZnO shows sharper peaks below 10–15 nm, consistent with tighter packing between crystallites. WO3 exhibits a similar but slightly broader distribution, suggesting more irregular agglomeration.

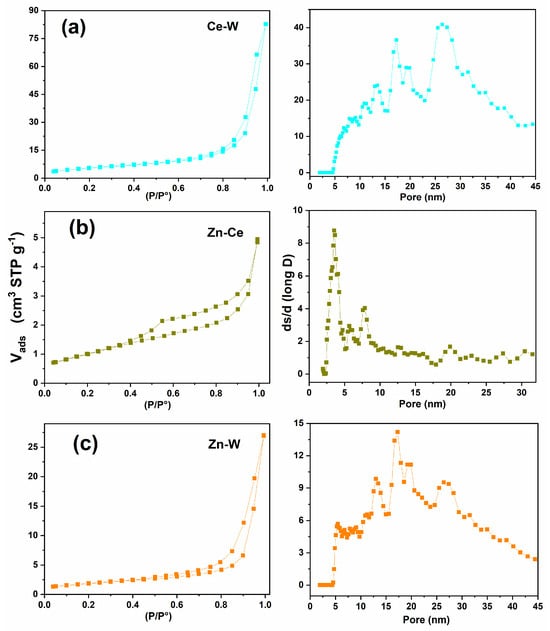

In the binary systems, the introduction of Ce into WO3 induced a transition toward an H1-type loop, suggesting the formation of more uniform and open mesopores (Figure 8a). Conversely, in the Zn–Ce composite, the hysteresis retained an H2 profile, indicating partial pore blocking by CeO2 nanoparticles (Figure 8b). The Zn–W sample displayed an H3-type loop, typical of aggregates with layered or sheet-like morphologies (Figure 8c).

Figure 8.

Nitrogen Nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms (left column) and corresponding pore size distributions (right column) for the binary samples: (a) Ce–W: (left) type-IV isotherm with H3 hysteresis; (right) broad mesopore distribution centered at ~15–30 nm. (b) Zn–Ce: (left) type-IV isotherm with moderate hysteresis; (right) multimodal mesopore distribution with maxima near 5–12 nm. (c) Zn–W: (left) type-IV isotherm with marked H3 hysteresis; (right) wide mesopore distribution extending from ~10 to 35 nm.

In the binary mixtures, the combination of oxides produces wider and more irregular pore-size distributions. This broadened range indicates that heterointerfacial contact between phases disrupts uniform particle packing, generating additional voids and structural disorder. The Zn–W mixture displays particularly wide distributions, consistent with the formation of ZnWO4 alongside unreacted oxide domains.

The ternary Zn–W–Ce composites exhibited combined features of H2 and H4 hysteresis, reflecting a heterogeneous mesoporous network with interconnected pores of different sizes (Figure 9a,b).

Figure 9.

Nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms (left column) and corresponding pore size distributions (right column) for the ternary samples: (a) Zn–W–Ce: (left) type-IV isotherm with pronounced H3 hysteresis; (right) mesopore distribution dominated by pores of ~5–15 nm with a long tail toward larger diameters. (b) 2Zn–W–Ce: (left) type-IV isotherm with moderate H3 hysteresis; (right) broad distribution with maxima around 5–12 nm and gradual decay up to ~40 nm. (c) 3Zn–W–Ce: (left) type-IV isotherm with marked hysteresis at high relative pressure; (right) mesopore distribution centered near 5–10 nm with extended tail toward the macropore region.

The ternary systems show the broadest pore-size distributions, extending toward larger pore diameters (~30–40 nm). This behavior suggests that the simultaneous presence of Zn, W, and Ce species leads to less compact agglomerates and increased interparticle spacing. These more open textural frameworks facilitate mass transfer and may enhance photocatalytic performance by improving pollutant diffusion through the catalyst.

The surface area and pore characteristics were also strongly affected by the oxide combination. CeO2 showed the highest specific surface area among the pure oxides, while ZnO and WO3 exhibited much lower values, consistent with their compact morphologies. Incorporation of Ce into WO3 significantly increased the surface area and total pore volume, indicating improved dispersion and enhanced textural accessibility. In contrast, the Zn–Ce composite showed only a moderate increase in area, consistent with partial pore blockage by Ce species. The Zn–W binary system displayed a noticeable enlargement of the pore diameter due to the formation of ZnWO4 domains. The ternary Zn–W–Ce composites presented intermediate surface areas and the largest pore diameters, revealing that the simultaneous incorporation of Ce and W species into the ZnO framework promotes the generation of interconnected mesopores and larger.

All samples exhibited type IV isotherms, resulting from capillary condensation processes characteristic of mesoporous materials. According to the IUPAC classification, type IV isotherms are indicative of mesoporous structures with pore sizes ranging between 2 and 50 nm [].

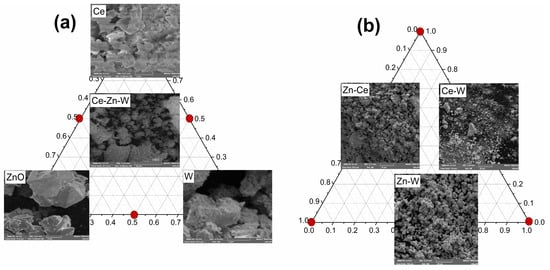

3.6. SEM Analysis

Figure 10 shows the SEM micrographs of all the synthesized samples. The Ce sample exhibited a morphology composed of irregularly shaped particles with flat surfaces and exposed edges. In contrast, the Zn sample showed a more defined morphology, characterized by randomly distributed agglomerates with smooth surfaces and angular contours, forming well-developed crystalline structures. The W sample displayed aggregated particles with irregular morphology and no well-defined shape, indicating a polydisperse size distribution and a rough surface texture.

Figure 10.

SEM micrographs of pure, binary, and ternary samples. (a) the individual oxides Ce, W and Zn and the ternary compositions Ce–Zn–W; (b) the binary mixtures Zn–Ce, Ce–W, and Zn–W.

The Zn–Ce sample exhibited clusters of spherical particles compactly assembled into larger agglomerates. In contrast, the Ce–W sample showed a heterogeneous morphology, consisting of particles with variable sizes and irregular shapes. The surface appeared predominantly rough, with unevenly distributed particles of different morphologies. The Zn–W sample displayed spherical particles forming dense agglomerates, consistent with the characteristics typically observed for ZnWO4-based materials. Finally, the ternary Zn–W–Ce sample exhibited a plate-like morphology interspersed with smaller spherical particles. This observation agrees with the features seen in the pure Ce sample, suggesting that the plate-like structures correspond to CeO2, whereas the spherical particles are attributed to zinc tungstate (ZnWO4).

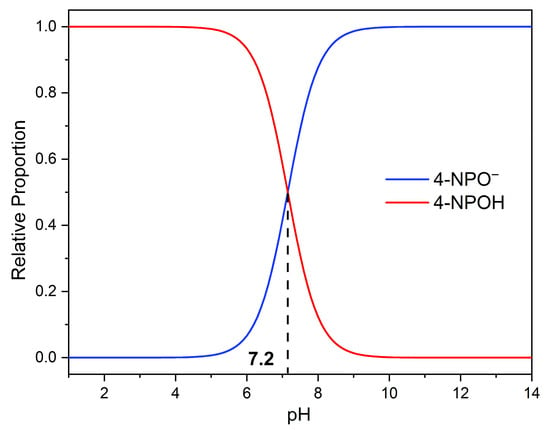

3.7. Photodegradation of 4-Nitrophenol (4-NPOH)

The photocatalytic degradation of 4-nitrophenol (4-NPOH) was carried out in water without any buffering agent, with an initial pH of 6.2, a typical value for distilled water. Under these conditions, 4-NPOH undergoes an acid–base equilibrium, where it can deprotonate to form 4-nitrophenolate (4-NP−), with a reported pKa of 7.2. By calculating the equilibrium fractions of 4-NP−/C0 and 4-NPOH/C0, it was determined that, at this pH, both species coexist in solution, with approximate proportions of 0.9 for 4-NPOH and 0.1 for 4-NP−, as shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Fractions of 4-NPO− and 4-NPOH as a function of pH.

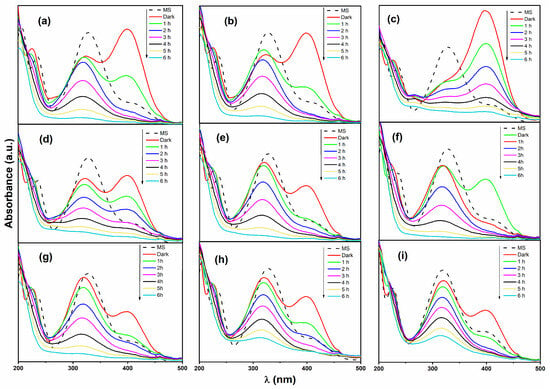

The UV–Vis spectra of 4-nitrophenol (4-NPOH) photodegradation over time are shown in Figure 12. In the absence of catalyst (dashed line), the predominant species in solution corresponds to 4-NPOH, exhibiting a main absorption band at λmax = 340 nm. Under these conditions, a minor signal at λmax = 410 nm is attributed to the 4-nitrophenolate ion (4-NPO−), since the solution pH (<7) favors the protonated form. It is worth noting that 4-NPO− possesses a higher molar absorptivity coefficient (ε) than its conjugate acid, resulting in greater absorbance intensity [].

Figure 12.

UV–Vis absorption spectra during the photocatalytic degradation of 4-nitrophenol (4-NPOH). Each subfigure shows the initial spectrum (MS), the dark adsorption–desorption stage (Dark), and the spectral evolution under UV irradiation from 1 h to 6 h. Pure oxides: (a) Ce; (b) Zn. Binary mixtures: (c) W; (d) Zn–Ce; (e) Zn–W; (f) Ce–W. Ternary mixtures: (g) Zn–W–Ce; (h) 2Zn–W–Ce; (i) 3Zn–W–Ce.

For the Ce sample (Figure 12a), an increase in the 4-NPO− signal was observed after the 30-min adsorption–desorption equilibrium. This effect is associated with the acid–base buffering capacity of CeO2, which can interact with protons in solution and slightly modify the local pH. CeO2 has a point of zero charge (pHpzc) of approximately 6.8. When the solution pH is lower than the pHpzc, the CeO2 surface tends to become positively charged by adsorbing H+ ions, which decreases the proton concentration in solution and shifts the equilibrium toward the deprotonated 4-NPO− form []. Upon UV irradiation, the 4-NPO− species rapidly decreases within the first 2 h of reaction, while 4-NPOH degrades gradually afterward.

The UV–Vis spectra for the W sample are shown in Figure 12b. After the equilibrium stage, an increase in the 4-NPO− fraction was also observed, attributed to the presence of WO3, which has a pHpzc in the range of 1.5–2.5. At the natural solution pH (6.6), the WO3 surface becomes negatively charged, favoring proton adsorption and inducing a slight pH increase []. Consequently, the acid–base equilibrium shifts toward 4-NPO− formation. Upon UV irradiation, the 4-NPO− species disappears within approximately 2 h, while 4-NPOH degrades gradually over 6 h.

For the Zn sample (Figure 12c), the highest absorption intensity of the 4-NPO− species was observed after the equilibrium stage, indicating that ZnO strongly promotes 4-NPOH deprotonation. According to literature, at pH < 7.6, ZnO forms an external [Zn(OH)]+ layer that is soluble in water and can react with 4-NPOH to form 4-NP−. At pH > 7.4, Zn(OH)2 forms, further facilitating equilibrium displacement toward the phenolate ion []. During irradiation, the 4-NPOH signal decreased steadily, while the 4-NPO− peak diminished more slowly. These results indicate that the Zn sample first promotes the conversion of 4-NPOH to 4-NP−, followed by subsequent photodegradation of the phenolate species.

The UV–Vis spectra for the Zn–Ce sample are shown in Figure 12d. After the adsorption–desorption equilibrium stage, the formation of 4-NPO− was clearly favored. Upon the onset of irradiation, both 4-NPOH and 4-NPO− species degraded simultaneously. These results suggest that the conversion of 4-NPOH to 4-NPO− in the Zn–Ce sample is primarily facilitated by ZnO, whereas the subsequent oxidative degradation of 4-NPO− is promoted by reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated during the photocatalytic process. The Ce–W sample (Figure 12e) exhibited the formation of 4-NPO− during the equilibrium stage, induced by the combined effect of CeO2 and WO3 present in the mixture. Under irradiation, both species degraded, but the 4-NPO− ion was removed at a faster rate than the molecular 4-NPOH. A similar trend was observed for the ternary Zn–W–Ce sample and its replicates (Figure 12g–i), where the coexistence and simultaneous degradation of both species were evident. For all catalysts, the initial reaction rate (ri), apparent rate constant (k), half-life (t1/2), and conversion percentage were determined based on the degradation of 4-NPOH, as summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Kinetic parameters for the photocatalytic degradation of 4-NP under UV irradiation.

The reaction rate for the different samples, as a function of their structural composition, revealed that cerium oxide (Ce) and tungsten oxide (W) individually exhibited the highest degradation rates for 4-NPOH. The presence of CeO2 and WO3 enhanced the initial reaction rate in the W–Ce mixture, while the Zn–Ce system also showed favorable performance.

It is worth noting that the Zn–W sample, in which the formation of a zinc tungstate (ZnWO4) phase was confirmed, exhibited a higher reaction rate than the other binary mixtures. The ternary samples (Zn–W–Ce) contained both CeO2 and ZnWO4 phases; however, the presence of CeO2 in the ternary composition slightly inhibited the reaction rate compared with Zn–W, possibly due to changes in the surface charge distribution and recombination dynamics.

The apparent rate constant (k) values indicate that Ce, W, and Zn–W exhibited the highest photocatalytic activities, which correlates with their shorter half-lives (t1/2). These results suggest that the overall photocatalytic efficiency is not solely governed by the optical band gap, but also by the availability and effectiveness of surface-active sites, which facilitate charge separation and interfacial redox reactions [].

Therefore, although a narrower band gap may enhance light absorption, it does not necessarily guarantee higher photocatalytic performance unless efficient charge separation and surface reaction kinetics are achieved.

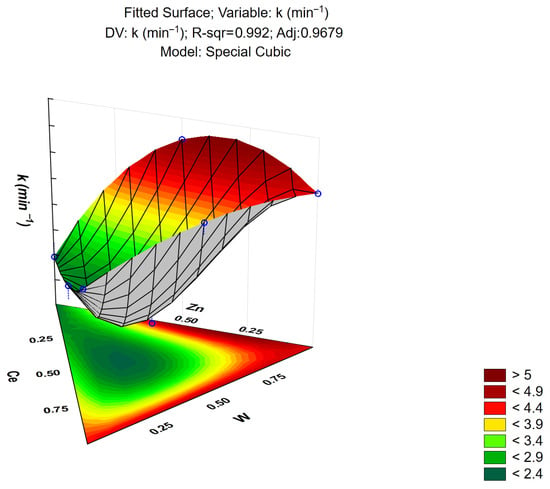

3.8. Response Surface Modeling

Mathematical models were fitted considering the apparent rate constant (k) and the band gap as the response variable. The statistical parameters of the fitted models are summarized in Table 4. Among the evaluated models, the cubic model exhibited the highest correlation coefficients (R2 and adjusted R2) compared with the linear and quadratic models.

Table 4.

Statistical parameters corresponding to the model fitting for the kinetic constant (k).

The sum of squares (SS) value for the cubic model was also higher than those of the other models, indicating that this model better explains the variability of the kinetic constant. Furthermore, the F-value obtained for the cubic model was significantly greater than those for the linear and quadratic models, demonstrating its superior predictive capability.

In addition, the p-value of the cubic model confirmed that the fitting is statistically significant, suggesting a low probability that the observed behavior of the kinetic constant is due to random variation [,].

The response surface generated by the cubic model for the apparent rate constant (k) is shown in Figure 13. The shape of the surface reveals a nonlinear relationship between the composition of the materials and the kinetic constant. The optimal region for achieving a high reaction rate corresponds to the binary Zn–W system (ZnWO4), whereas an excess of cerium in the composition leads to a decrease in photocatalytic efficiency.

Figure 13.

Response surface plot describing the variation of the apparent rate constant k (min−1) as a function of the mixture proportions of Zn, W, and Ce in the simplex-centroid design. The color map indicates the predicted magnitude of k, ranging from low values (green) to high values (dark red), according to the scale shown in the lower-right corner. Blue circles represent the experimental mixture points, which were used to fit the special-cubic response surface model.

The coefficients of the cubic model are summarized in Table 5. The AC interaction term exhibited a positive coefficient, indicating that the combined effect of these two components positively influences the apparent rate constant of the reaction. In contrast, the AB and BC interactions were not statistically significant, as their corresponding p-values were greater than 0.05, suggesting that these factors have no relevant impact on the kinetic response. On the other hand, the ABC interaction term presented a negative coefficient, indicating an adverse effect on the overall photocatalytic performance.

Table 5.

Coefficients of the cubic model.

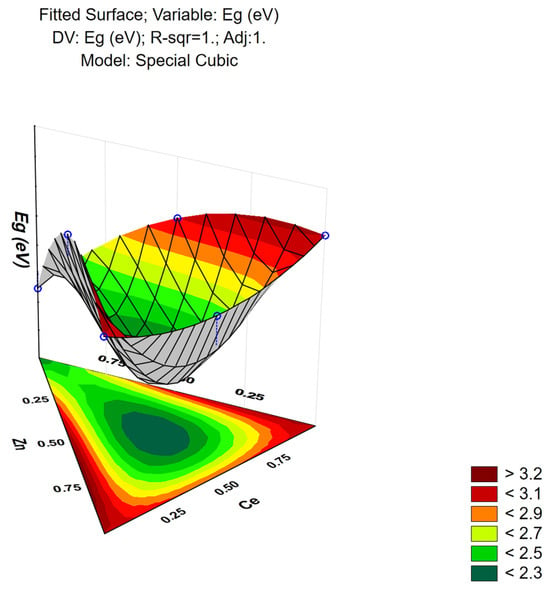

Table 6 summarizes the statistical parameters obtained from the fitting of the mathematical models, considering the band gap as the response surface variable. The results indicate that the cubic model provides the best fit, exhibiting the highest determination coefficient and the lowest p-value, confirming its statistical significance compared with the linear and quadratic models.

Table 6.

Statistical parameters corresponding to the model fitting for the band gap (Eg).

The response surface generated by the cubic model as a function of the band gap is shown in Figure 14. The presence of W significantly affects the band gap, particularly when combined with Zn and Ce. Increasing the amount of W leads to an increase in the band gap. However, when Zn is present in higher proportions, a tendency to decrease the band gap is observed. Conversely, Ce counteracts the band gap reduction induced by Zn.

Figure 14.

Three-dimensional response surface showing the predicted optical band gap (Eg, eV) as a function of the mixture fractions of Zn, Ce, and W in the simplex-centroid design. The color gradient (scale shown at right) represents the magnitude of Eg, from lower values (green) to higher values (dark red). Blue circular markers indicate the actual experimental mixture points, which were used to generate and validate the fitted special-cubic surface.

The coefficients of the cubic model are presented in Table 7. The AB interaction showed a negative coefficient, indicating that the combination of zinc oxide and cerium oxide tends to reduce the band gap. The AC interaction had a positive coefficient, suggesting that the zinc tungstate (ZnWO4) alloy promotes a higher band gap. The BC interaction was also positive, indicating that the combined presence of CeO2 and WO3 contributes to an increase in the band gap, albeit less significantly than the ZnWO4 interaction. The interaction among the three precursors (ABC) showed a negative coefficient, indicating that the presence of cerium oxide in the ZnWO4 alloy significantly reduces the band gap.

Table 7.

Statistical analysis of the effects of factors and their interactions in the response model.

When analyzing both response surfaces, it is observed that the material with the smallest band gap exhibits the lowest activity in the photodegradation of 4-NPOH. According to the literature, a reduced band gap facilitates greater light absorption and enhanced generation of electron-hole pairs (e−/h+). However, the efficiency of these processes does not exclusively depend on the band gap size but rather on the availability and effectiveness of the material’s active sites, which enable proper separation and reaction of the generated pairs []. This suggests that while a smaller band gap can be beneficial for light absorption, it does not guarantee higher photocatalytic efficiency if charge separation is not optimal.

3.9. Scavenger Tests and Reusability Cycles Analysis

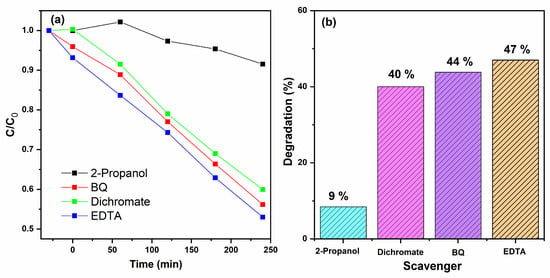

The scavenger experiments were conducted to identify the reactive species involved in the photocatalytic process, thereby providing further insight into the reaction mechanism. For these tests, the Zn–W sample was selected, and different chemical scavengers with specific affinities for reactive species were employed.

2-propanol, benzoquinone (BQ), potassium dichromate (K2Cr2O7), and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) were used as quenchers for hydroxyl radicals (•OH), superoxide radicals (•O2−), electrons (e−), and holes (h+), respectively. Each scavenger was added at a 1:1 molar ratio relative to the contaminant concentration. The effects of these scavengers on photocatalytic degradation efficiency are presented in Figure 15. The addition of 2-propanol produced a marked decrease in photoactivity during 4-nitrophenol degradation, reducing the overall conversion to 9%, which indicates that hydroxyl radicals (•OH) play a dominant role in the degradation process. These results confirm that the photodegradation of 4-nitrophenol under UV irradiation is mainly governed by the generation of hydroxyl radicals, which act as the primary oxidative species responsible for pollutant mineralization [,,].

Figure 15.

E Scavenger analysis for 4-NPOH photodegradation. (a) Photocatalytic degradation profiles (C/C0 vs. time) in the presence of different scavengers: 2-propanol, benzoquinone (BQ), dichromate, and EDTA. (b) Percentage degradation after 240 min for each scavenger, showing the relative contribution of •OH, O2•−, and h+ to the reaction pathway.

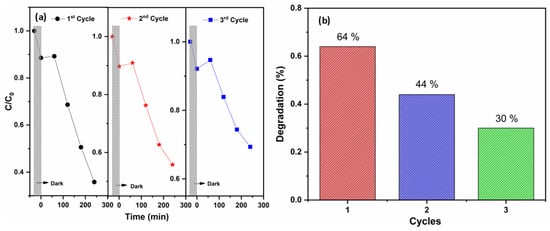

To evaluate the stability and reusability of the most active photocatalyst (Zn–W), multiple photocatalytic cycles were performed. These tests allow the assessment of whether photocatalytic activity decreases over time, which would indicate possible deactivation phenomena or loss of active material due to photocorrosion, accumulation of reaction intermediates, or structural modification of the catalyst.

The results of the recycling experiments are presented in Figure 16a. A progressive decrease in the initial reaction rate was observed, with reductions of approximately 33% after the second cycle and 51% after the third cycle. Figure 16b shows a bar chart of the corresponding degradation efficiencies for each reuse cycle, revealing an overall ~50% loss in photocatalytic efficiency after three consecutive runs.

Figure 16.

Photocatalyst reusability performance. (a) Temporal evolution of the normalized concentration (C/C0) of 4-nitrophenol during three consecutive photocatalytic degradation cycles, including the dark-adsorption stage (gray shaded region). (b) Degradation efficiency (%) obtained for each cycle, illustrating the progressive decline in activity upon reuse.

According to the results, the Zn–W sample can form zinc tungstate hydroxide (Zn[W(OH)8]), which promotes the release of soluble [WO4]2− ions due to the interaction between tungsten species and 4-nitrophenol (4-NPOH). This organic compound can act as a reactive agent that disturbs the equilibrium between hydroxide and oxide phases, favoring the decomposition of Zn[W(OH)8] and subsequent liberation of WO3 [,].

This release occurs because 4-NPOH facilitates electron transfer, leading to the breakage of W–OH bonds within the tungstate structure. Consequently, the gradual formation of 4-NPO− observed in the UV–Vis spectra is limited by the generation and detachment of hydroxyl groups from the Zn–W surface.

Therefore, the progressive loss of photocatalytic activity is attributed to the structural degradation of the catalyst itself, resulting from [WO4]2− leaching and surface hydroxide instability during repeated photocatalytic cycles.

To verify the proposed deactivation mechanism associated with tungsten leaching, a ZnWO4 sample was immersed in deionized water and stirred for 24 h under dark conditions. The solid was then recovered, dried, and analyzed by FT-IR before and after treatment (Figure 17).

Figure 17.

FT-IR spectra of the ZnWO4 sample before (ZnWO4_A) and after (ZnWO4_B) contact with water. The intentional overlap of the two spectra allows a direct point-by-point comparison, making it possible to visualize the subtle but meaningful increase in transmittance between 1500 and 500 cm−1. This crossing of the curves is necessary to highlight spectral differences associated with the partial loss of WO3 species, which would not be discernible if the spectra were plotted separately.

As previously discussed, the pristine ZnWO4 sample exhibited characteristic absorption bands below 1000 cm−1, particularly in the 700–900 cm−1 range, corresponding to the W–O–W bridging vibrations typical of tungstate structures. The bands between 400 and 600 cm−1 were attributed to Zn–O stretching vibrations, confirming the incorporation of Zn into the wolframite-type lattice. No broad bands were observed in the 3000–3500 cm−1 region, indicating the absence of surface hydroxyl groups or adsorbed moisture.

After 25 h of contact with water (ZnWO4B), a slight increase in transmittance and broadening of the W–O stretching bands was observed, accompanied by a minor shift toward lower wavenumbers. These spectral changes suggest a partial disruption of the W–O–W network, likely due to the dissolution of surface tungsten species into the aqueous phase as soluble tungstate ions [WO4]2−. The persistence of the Zn–O bands and the absence of new hydroxyl-related features indicate that the crystalline framework remains largely intact, although the surface tungsten content decreases.

This behavior indicates that not only the interaction with 4-NP, but also prolonged exposure to water can favor tungsten leaching from the Zn–W lattice, thereby weakening the structural integrity of the catalyst. The progressive loss of W–O linkages is consistent with the decrease in photocatalytic activity observed during reuse cycles, supporting the hypothesis that catalyst deactivation is associated with the gradual release of tungsten species into the reaction medium.

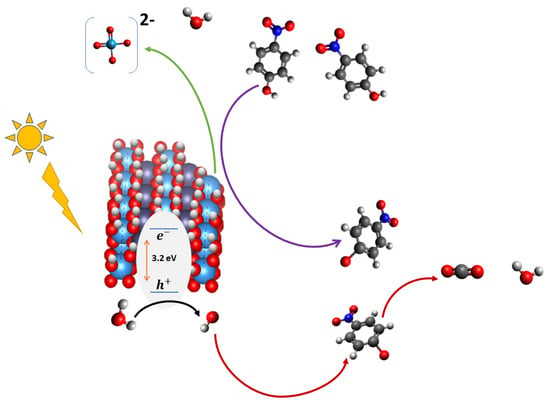

3.10. Reaction Mechanism

In an aqueous medium, the Zn–W composite can partially hydroxylate its surface, forming zinc tungstate hydroxide (Zn[W(OH)8]) species. These surface complexes interact with 4-nitrophenol (4-NPOH) through hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions, promoting its deprotonation to the 4-nitrophenolate ion (4-NPO−). The negatively charged 4-NPO− species can further coordinate with protonated W–OH groups through ligand-exchange or hydrogen-bonding interactions, generating weak surface complexes. Upon UV irradiation, electron–hole (e−/h+) pairs are generated within the semiconductor framework. The photogenerated holes (h+) oxidize surface hydroxyl groups and adsorbed water molecules to produce hydroxyl radicals (•OH), which serve as the main oxidative species responsible for the degradation of 4-NP−. Simultaneously, electrons photogenerated in ZnO and WO3 domains migrate through the W-center of Zn[W(OH)8], facilitating interfacial charge transfer and enhancing redox reactions at the surface.

However, the continuous interaction and adsorption of 4-NPO− on W-OH groups can also promote partial ligand-assisted leaching of tungsten as soluble [WO4]2− ions. This process leads to progressive structural degradation of the Zn–W catalyst, decreasing the number of active tungsten centers available for electron transfer and ultimately reducing the photocatalyst’s stability and reusability over successive cycles, see Figure 18.

Figure 18.

Proposed photocatalytic reaction mechanism for the Zn–W system. The yellow sun and lightning symbol represent UV irradiation. Inside the semiconductor, the orange arrows depict electron excitation across the 3.2 eV band gap and the corresponding generation of photogenerated holes. The purple arrow denotes the initial interaction of 4-nitrophenol with the ZnWO4 surface, where surface complexation promotes its conversion into 4-nitrophenolate (4-NP−). This interfacial process also induces partial tungsten leaching from the catalyst, forming soluble [WO4]2− ions. The green arrow represents the subsequent interaction of the surface-bound 4-NP− with reactive species generated in the photogenerated hole pathway (e.g., •OH), leading to progressive oxidation. The red arrow illustrates the final degradation steps, resulting in the formation of lower-molecular-weight products. Atom colors follow standard conventions (C = black, O = red, H = white, N = blue, W = teal). This schematic is illustrative; partial overlap of elements does not affect interpretation.

4. Conclusions

ZnO–CeO2–WO3 composites were successfully synthesized through a simplex–centroid mixture design, enabling precise control of oxide proportions. XRD and FT-IR analyses confirmed the formation of crystalline phases of ZnO, CeO2, WO3, and ZnWO4, depending on the mixture. The presence of CeO2 effectively inhibited crystal growth, producing smaller crystallite sizes (7–10 nm) and generating a higher density of surface defects.

UV–Vis DRS measurements revealed a reduction of the band gap from 3.1 eV (ZnO, CeO2) to 2.2 eV in the ternary Zn–W–Ce composite, expanding light absorption toward the visible range. However, the response surface modeling indicated that photocatalytic activity is not governed solely by the band gap size, but by the efficiency of charge separation and surface reactivity.

The PL spectra demonstrated that the Zn–W–Ce and W–Ce composites exhibit markedly lower emission intensities than the individual oxides, confirming the suppression of radiative recombination. This effect arises from interfacial charge transfer between ZnWO4 and CeO2, which promotes longer carrier lifetimes and more efficient electron–hole separation.

Nitrogen adsorption–desorption analyses revealed mesoporous structures (type IV isotherms) with combined H2–H4 hysteresis loops, characteristic of heterogeneous pore networks. The introduction of CeO2 and WO3 increased surface area and pore volume, enhancing the dispersion of active sites and favoring pollutant adsorption.

Photodegradation tests under UV light (λ = 365 nm) without pH adjustment showed that the binary Zn–W system (ZnWO4 phase) achieved the highest activity, reaching 81% degradation of 4-nitrophenol with an apparent rate constant of 5.1 × 10−3 min−1. The activity trend followed: Zn–W > W–Ce ≈ Ce > Zn–Ce > Zn–W–Ce > Zn.

The results confirmed a strong correlation between photocatalytic activity, pollutant speciation, and surface charge governed by the point of zero charge (pHpzc). The deprotonation of 4-NPOH to 4-NPO− near neutral pH modulated the adsorption on positively or negatively charged surfaces, highlighting the importance of pHpzc-driven electrostatic interactions in controlling degradation kinetics.

Scavenger tests identified hydroxyl radicals (•OH) as the dominant oxidative species, supported by the drastic drop in activity upon 2-propanol addition. The combined evidence suggests a mechanism dominated by interfacial charge transfer within ZnWO4, generating •OH radicals through valence-band oxidation and conduction-band reduction of oxygen species.

The Zn–W photocatalyst maintained structural stability over multiple cycles, though a 51% loss in activity occurred after the third reuse, attributed to WO3 leaching through formation of soluble [WO4]2− species. This behavior indicates that surface reconstruction and tungstate solubilization are key factors limiting long-term durability.

This study establishes a clear mechanistic framework linking the pHPzc, pollutant acid–base equilibrium, and photocatalytic efficiency. It demonstrates that optimal degradation occurs when the reaction pH is close to the catalyst’s pHPzc, maximizing electrostatic attraction and surface reaction rates. These findings provide valuable design criteria for developing pH-tolerant photocatalysts in real wastewater matrices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L.C.-M.; Methodology, C.M.G. and R.O.S.-D.; Software, A.A.S.-P.; Formal analysis, L.E.S.d.l.R. and R.O.S.-D.; Investigation, A.R.A.-L.; Resources, S.G.; Data curation, G.E.C.-P.; Visualization, J.R.C.-C. and R.O.S.-D.; Supervision, A.C.-U.; Funding acquisition, S.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by CONAHCYT through the project “Continuous-flow photocatalytic microfluidic reactors based on 2D heterojunction materials for treatment of aqueous pollutants” (CF-2023-G-1177). The author also received a CONAHCYT postgraduate scholarship (CVU-1232701), which provided personal support during the development of this study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the institutions and colleagues who provided technical assistance and access to laboratory facilities during the completion of this work. Special thanks to CONAHCYT for the support provided to Alma Rosa Alejandro López (CVU 1232701) and for the project “Continuous-flow photocatalytic microfluidic reactors based on 2D heterojunction materials for treatment of aqueous pollutants” (CF-2023-G-1177).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Sarkar, P.; Dey, A. 4-Nitrophenol Biodegradation by an Isolated and Characterized Microbial Consortium and Statistical Optimization of Physicochemical Parameters by Taguchi Methodology. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 104347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoro, H.K.; Orosun, M.M.; Victor, A.; Zvinowanda, C. Health Risk Assessment, Chemical Monitoring and Spatio-Temporal Variations in Concentration Levels of Phenolic Compounds in Surface Water Collected from River Oyun, Republic of Nigeria. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2022, 8, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Yu, Y.; Jung, H.J.; Naik, S.S.; Yeon, S.; Choi, M.Y. Efficient Recovery of Palladium Nanoparticles from Industrial Wastewater and Their Catalytic Activity toward Reduction of 4-Nitrophenol. Chemosphere 2021, 262, 128358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iben Ayad, A.; Luart, D.; Ould Dris, A.; Guénin, E. Kinetic Analysis of 4-Nitrophenol Reduction by “Water-Soluble” Palladium Nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, M.; Zhang, L.; Liu, S.; Wang, D.; Qin, Y.; Chen, Y.; Dai, W.; Wang, Y.; Xing, Q.; Zou, J. Degradation of 4-Nitrophenol by Electrocatalysis and Advanced Oxidation Processes Using Co3O4@C Anode Coupled with Simultaneous CO2 Reduction via SnO2/CC Cathode. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2020, 31, 1961–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Ni, Y.; Wu, Y.; Yue, W.; Zhang, G.; Bai, J. Electrocatalytic Degradation of Methyl Orange and 4-Nitrophenol on a Ti/TiO2-NTA/La-PbO2 Electrode: Electrode Characterization and Operating Parameters. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 6262–6274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaimurugan, D.; Sivasankar, P.; Durairaj, K.; Lakshmanamoorthy, M.; Ali Alharbi, S.; Al Yousef, S.A.; Chinnathambi, A.; Venkatesan, S. Novel Strategy for Biodegradation of 4-Nitrophenol by the Immobilized Cells of Pseudomonas sp. YPS3 with Acacia Gum. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudha, M.; Renu, G.; Sangeeta, G. Mineralization and Degradation of 4-Nitrophenol Using Homogeneous Fenton Oxidation Process. Environ. Eng. Res. 2020, 26, 190145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosaka, Y.; Nosaka, A.Y. Generation and Detection of Reactive Oxygen Species in Photocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 11302–11336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhtar, A.; Akram, K.; Aslam, Z.; Ihsanullah, I.; Baig, N.; Bello, M.M. Photocatalytic Degradation of P-nitrophenol in Wastewater by Heterogeneous Cobalt Supported ZnO Nanoparticles: Modeling and Optimization Using Response Surface Methodology. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2023, 42, e13984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahya, A.A.; Rashid, K.T.; Ghadhban, M.Y.; Mousa, N.E.; Majdi, H.S.; Salih, I.K.; Alsalhy, Q.F. Removal of 4-Nitrophenol from Aqueous Solution by Using Polyphenylsulfone-Based Blend Membranes: Characterization and Performance. Membranes 2021, 11, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, W.-Y.; Sheeley, S.A.; Rajh, T.; Cropek, D.M. Photocatalytic Reduction of 4-Nitrophenol with Arginine-Modified Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2007, 74, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Ray, A.K. Photodegradation Kinetics of 4-Nitrophenol in TiO2 Suspension. Water Res. 1998, 32, 3223–3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokri, A.; Mahanpoor, K.; Soodbar, D. Evaluation of a Modified TiO2 (GO–B–TiO2) Photocatalyst for Degradation of 4-Nitrophenol in Petrochemical Wastewater by Response Surface Methodology Based on the Central Composite Design. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 585–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Patra, M.; Kumar, P.; Bhagavathiachari, M.; Nair, R.G. Defect-Induced Visible-Light-Driven Photocatalytic and Photoelectrochemical Performance of ZnO–CeO2 Nanoheterojunctions. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 858, 157730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleem, A.; Shafiq, A.; Chen, S.-Q.; Nazar, M. A Comprehensive Review on Adsorption, Photocatalytic and Chemical Degradation of Dyes and Nitro-Compounds over Different Kinds of Porous and Composite Materials. Molecules 2023, 28, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, L.V.; Alcántar-Vázquez, B.; Manríquez, M.E.; Albiter, E.; Ortiz-Islas, E. Photodegradation of Emerging Pollutants Using a Quaternary Mixed Oxide Catalyst Derived from Its Corresponding Hydrotalcite. Catalysts 2025, 15, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thai, N.-T.-P.; Nguyen, B.-N.; Luan, V.-H.; Son, L.V.T.; Dang, B.-T.; Le, M.-V. Synthesis and Photocatalytic Activity of BiOI Particles: An Efficient Visible-Light-Driven Degradation of Organic Pollutants in Aqueous Environments. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2024, 1340, 012009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyoud, A.H.; Zubi, A.; Zyoud, S.H.; Hilal, M.H.; Zyoud, S.; Qamhieh, N.; Hajamohideen, A.; Hilal, H.S. Kaolin-Supported ZnO Nanoparticle Catalysts in Self-Sensitized Tetracycline Photodegradation: Zero-Point Charge and pH Effects. Appl. Clay Sci. 2019, 182, 105294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Ma, J.; Sun, Z.; Zhai, X. Mechanism of Influence of Initial pH on the Degradation of Nitrobenzene in Aqueous Solution by Ceramic Honeycomb Catalytic Ozonation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 4002–4007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khairy, M.; Naguib, E.M.; Mohamed, M.M. Enhancement of Photocatalytic and Sonophotocatalytic Degradation of 4-Nitrophenol by ZnO/Graphene Oxide and ZnO/Carbon Nanotube Nanocomposites. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2020, 396, 112507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiwaan, H.A.; Atwee, T.M.; Azab, E.A.; El-Bindary, A.A. Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Dyes in the Presence of Nanostructured Titanium Dioxide. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1200, 127115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirikaram, N.; Pérez-Molina, Á.; Morales-Torres, S.; Salemi, A.; Maldonado-Hódar, F.J.; Pastrana-Martínez, L.M. Photocatalytic Performance of ZnO-Graphene Oxide Composites towards the Degradation of Vanillic Acid under Solar Radiation and Visible-LED. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, W.; Khan, A.; Hussain, S.; Khan, H.; Abumousa, R.A.; Bououdina, M.; Khan, I.; Iqbal, S.; Humayun, M. Enhanced Light Absorption and Charge Carrier’s Separation in g-C3N4-Based Double Z-Scheme Heterostructure Photocatalyst for Efficient Degradation of Navy-Blue Dye. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2024, 17, 2381591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, B.R.; Patel, U.D. Reductive Transformation of Aqueous Pollutants Using Heterogeneous Photocatalysis: A Review. J. Inst. Eng. India Ser. A 2022, 103, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, D.; Thinthasit, A.; Wannakan, K.; Surya, R.; Nanan, S.; Benchawattananon, R. Well-Synthesized Carbon Dots from Flower of Cassia Fistula and Its Hydrothermally Grown Heterojunction Photocatalyst with Zinc Oxide (CDs@ZnO-H400) for Photocatalytic Degradation of Ciprofloxacin and Paracetamol. Arab. J. Chem. 2024, 17, 105931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Bang, G.; Liu, L.; Lee, C.-H. Synthesis of Mesoporous MgO–CeO2 Composites with Enhanced CO2 Capture Rate via Controlled Combustion. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2019, 288, 109587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Liu, H.C.; Wu, M.; Han, L.; Wang, Z. A Sensitive Electrochemical Sensor for Detection of Methyltestosterone as a Doping Agent in Sports by CeO2/CNTs Nanocomposite. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2023, 18, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, S.; Selvapandiyan, M.; Sasikumar, P.; Parthibavaraman, M.; Nithiyanantham, S.; Srisuvetha, V.T. Investigation on the Properties of Vanadium Doping WO3 Nanostructures by Hydrothermal Method. Mater. Sci. Energy Technol. 2022, 5, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, T.K.; Coetsee-Hugo, E.; Swart, H.C.; Swart, C.W.; Kroon, R.E. Preparation and Characterization of Ce Doped ZnO Nanomaterial for Photocatalytic and Biological Applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2020, 261, 114780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chen, T. Development of Nanostructured Based ZnO@WO3 Photocatalyst and Its Photocatalytic and Electrochemical Properties: Degradation of Rhodamine B. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2023, 18, 100055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Cui, J.; Tang, Y.; Han, Z.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, G.; Diao, Q. Solvothermal Synthesis of Dual-Porous CeO2-ZnO Composite and Its Enhanced Acetone Sensing Performance. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 4103–4107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, B.G.; Rao, G.R. Promoting Effect of Ceria on the Physicochemical and Catalytic Properties of CeO2–ZnO Composite Oxide Catalysts. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2006, 243, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Liang, Y.; Cao, W.; Su, Y. Ionic Liquid-Templated Synthesis of Mesoporous CeO2–TiO2 Nanoparticles and Their Enhanced Photocatalytic Activities under UV or Visible Light. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2011, 223, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadoran, A.; Ramakrishna, S.; Masudy-Panah, S.; Roshan De Lile, J.; Sadeghi, B.; Li, J.; Gu, J.; Liu, Q. Novel S-Scheme WO3/CeO2 Heterojunction with Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Sulfamerazine under Visible Light Irradiation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 568, 150957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]