Abstract

According to the Donnell–Mushtari shell theory, this work presents a closed-form solution procedure for free vibration of open laminated circular cylindrical shells with arbitrary homogeneous boundary conditions (BCs). The governing differential equations of free vibration are derived from the Rayleigh quotient and solved by the iterative separation-of-variable (iSOV) method. In addition, considering axial aerodynamic pressure, simulated by the linear piston theory, the exact eigensolutions for the flutter of open laminated cylindrical shells with simply supported circumferential edges and closed laminated cylindrical shells are also achieved. The governing differential equations of cylindrical shell flutter are derived from the Hamilton variational principle and solved by the separation-of-variable (SOV) method. The influence of circumferential dimension on flutter speed is investigated for open cylindrical shells, which reveals that the number of circumferential waves in critical flutter mode increases with circumferential length, and there exists an infimum for flutter speed that is an invariant independent of circumferential length. The present results agree well with those obtained by the Galerkin method, the finite element method, and other analytical methods.

1. Introduction

As an important structural component, cylindrical laminated shells have a widespread application in diverse engineering fields, such as civil, mechanical, aerospace, marine, and offshore engineering, which can be attributed to their high stiffness-to-weight and strength-to-weight ratios and flexibility in design, wherein free vibration and flutter are two important issues that are related to structural safety and integrity. How to achieve the analytical solutions for these two eigenvalue problems of cylindrical laminated shells has long been a topic of interest for scholars.

Engineers need to understand the vibration behaviors of shell structures for more reliable and cost-effective designs [1]. The frequency of free vibration is an intrinsic quality for structural components, and calculating free vibration characteristics for cylindrical shells intrigues numerous engineers and scientists. The exact frequencies of cylindrical shells with simply supported conditions (also called shear diaphragm conditions [2,3]) on all edges are accessible by the inverse method [2,3,4], which can be considered a natural extension of the Naiver solutions. As for more complex conditions, wherein closed cylindrical shells have arbitrary homogeneous boundary conditions (BCs) on axial edges or open cylindrical shells have two opposite edges simply supported, the semi-inverse method can be used to obtain the Levy type of solutions. Without assumptions or simplifications beyond those underlying governing differential equations, Forsberg [5] obtained the exact frequencies of closed cylindrical shells with different axial boundaries. Following Forsberg’s work, the natural frequencies of clamped cylindrical shells were presented by Smith and Haft [6]. However, as pointed out by Smith and Half themselves, care must be taken to monitor the roots of the characteristic equation to ensure that the assumed form of solutions is preserved. Vronay and Smith [7] overcame this disadvantage by carrying all complex quantities as complex through the solution process. In order to decrease the effort required to solve for the coefficients of modal functions, Callahan and Baruh [8] developed a systematic procedure for obtaining closed-form solutions for thin circular cylindrical shell vibration; there, the obtained coefficients of modal functions were numerically determined. By using exact expressions for modal coefficients instead of calculating the coefficients through numerical methods, Xing and Liu et al. [2,3] obtained the exact solutions for the free vibration of isotropic and orthotropic closed and open circular cylindrical shells. In addition, the exact solutions for the free vibration of closed cylindrical shells with elastic restraints were attained by Zhong et al. [9]. To shorten the length of this article, the free vibration solutions obtained by numerical methods, such as the Galerkin method, the finite element method, the Rayleigh–Ritz method, etc., are not reviewed here. Relevant achievements can be found in the reviews presented by Liew et al. [10] and Qatu et al. [11,12,13].

Flutter is a self-excited oscillation caused by the coupling of elastic, inertial, and aerodynamic forces [14]. Since the first observation of panel flutter in World War II [14], panel flutter has been a popular subject of research on the aerodynamic behavior of aircraft structures, and plentiful research results have been achieved. The early theoretical and experimental studies were reviewed by Dowell [15] in 1970 and Mei et al. [16] in 1999, respectively, wherein flutter models are divided into five categories. Within the author’s knowledge, the up-to-date review for panel flutter was presented by Chai et al. [17] in 2021, wherein the state-of-the-art developments in panel flutter were summarized in detail from the perspectives of flutter mechanism, flutter model, flutter control, solving method, and the outlook on future investigations. In general, the theoretical analysis of panel flutter consists of solving flutter differential equations by using different structural dynamics theories and aerodynamic theories.

The calculation of aerodynamic pressure is an important part of panel flutter analysis. The aerodynamic theories used in panel flutter analysis mainly include the piston theory [18,19], the potential flow theory [20], and the theories based on Navier–Stokes equations [21,22], wherein the linear piston theory has a widespread application due to its concise expression for aerodynamic pressure. The piston theory was proposed by Lighthill [18], and its application scope has been investigated [16,20]. Meng [23,24] explained the physical meaning of high-order terms in the piston theory. When applied to a cylindrical shell, a more accurate version of linear piston theory was presented by Krumhaar [25], wherein the effect of curvature was taken into account.

Based on Donnell’s shell theory, Olson and Fung [26,27] compared the results obtained by the piston theory, potential theory, and experiment for simply supported cylindrical shells, indicating that results obtained by the piston theory appear to correspond more closely to the experiment. Motivated by the circumferentially traveling waves observed in the experiment [26], a nonlinear flutter analysis for simply supported cylindrical shells was performed by Evensen and Olson [28], which revealed that the circumferentially traveling wave flutter can be predicted through a nonlinear analysis. Using an improved structural and aerodynamic model, Amabili and Pellicano [29,30] reinvestigated the nonlinear stability of simply supported circular cylindrical shells in supersonic axial airflow. Except for the classical shell theory, the geometrical model of a shallow shell can also be constructed by a plate with initial deformation, as Amirzadegan and Dowell [31,32] performed. In their work, the instability and post-stability limit cycle oscillations of shallow shells in a supersonic gas flow were studied by the Galerkin method, which can be viewed as a sequel to Dowell’s earlier work [33]. Note that the flutter differential equations used in [27,28,29,30,31,32,33] were solved by the Galerkin method.

Since the trial functions used in the Galerkin method need to change as BCs and panel models change, the finite element method (FEM) is more convenient than the Galerkin method to solve complicated panel flutter models. Singha and Mandal [34] studied the supersonic flutter behaviors of laminated cylindrical shells using isoparametric degenerated shell elements. According to the Sander shell theory, Sabri and Lakis [35] investigated the influence of internal pressure and axial loading on the flutter characteristics of cylindrical shells by a hybrid FEM, and the results predicted by the FEM agreed with the experiment [26]. Based on the semi-analytical FEM, Mahmoudkhani [36] illustrated the effects of imperfections on the aero-thermoelastic behavior of functionally graded cylindrical shells. With the variable stiffness composite laminates (VSCLs) and the Love shell theory, Cachulo et al. [37] analyzed the aeroelastic stability of a VSCL cylindrical shell under supersonic airflow by the -version FEM. Bochkarev et al. [38] investigated the aeroelastic stability of shallow cylindrical shells stiffened with stringers by the FEM. Except for the Galerkin method and the finite element method, the Rayleigh–Ritz method [39] is also a common discrete method in flutter analysis for cylindrical shells.

From the above review, one can see that there are few analytical solutions of free vibration for open cylindrical shells. As for shell flutter, the analytical solutions of cylindrical shells are scarcer than those of beams [40,41] and flat panels [42,43,44], since the governing differential equations of cylindrical shell flutter are more complex than those of beams and flat plates.

In this context, according to the Donnell shell theory, this work obtains the closed-form analytical solutions of free vibration for open cylindrical shells with arbitrary combinations of homogeneous BCs by the iterative separation-of-variable (iSOV) method [45]. In addition, considering the axial aerodynamic pressure calculated by the linear piston theory, the exact solutions of open cylindrical shell flutter with simply supported circumferential edges and closed cylindrical shell flutter are also presented in this work. The effect of the circumferential dimension of the open cylindrical shell on flutter characteristics is investigated. The present results are compared with those obtained by the FEM, the Galerkin method, and other analytical methods.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 and Section 3 give the derivation of the basic equations for free vibration and flutter, respectively. Section 4 introduces the solving method. Section 5 presents the results of free vibration and flutter and compares them with those of other methods. Finally, the conclusions are drawn in Section 6.

2. Basic Equations of Free Vibration

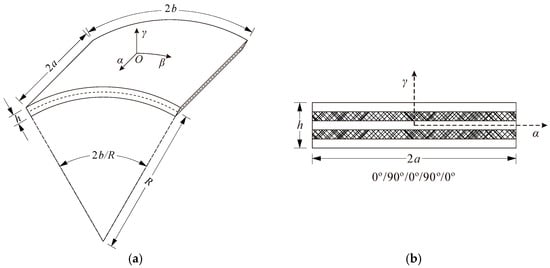

An open circular cylindrical shell with thickness , axial length , and circumferential length is shown in Figure 1. The cylindrical coordinate system with axial coordinate , circumferential coordinate , and normal coordinate is set in the middle surface, and the origin is located at the center of the middle surface. The cylindrical shell consists of five layers of homogeneous orthotropic sheets in the ply stacking sequence of . Each layer with identical thickness uses the same orthotropic material with the density , the Young’s modulus , the shear modulus , and the Poisson’s ratio .

Figure 1.

An open laminated circular cylindrical shell and coordinates. (a) Open circular cylindrical shell. (b) Ply stacking sequence.

2.1. Expressions of Energy

According to the Donnell shell theory, the displacements of the cylindrical shell have the forms as follows:

where are the displacements of an arbitrary point in the cylindrical shell along the directions, are the displacements of the middle surface along the directions, and is the time variable. The kinetic energy can be expressed as follows:

The potential energy is as follows:

wherein and represent the membrane and bending energy, respectively, which have the following forms [46]:

where and denote the membrane and bending stiffness, respectively. Considering the ply stacking sequence , the expressions of and are as follows:

where

For convenience, the dimensionless coordinates are used in the following equations. Assume that the displacements of the middle surface can be written in the separation-of-variable form as follows:

where represents the dimensional frequency for free vibration and . Substituting Equation (8) into Equation (2) obtains the amplitude of the kinetic energy, where the referenced kinetic energy is as follows:

Introducing Equation (8) into Equations (4) and (5) yields the amplitude of the potential energy, as follows:

where

In the following, the governing differential equations in the and directions are derived from the Rayleigh quotient.

where ‘st’ stands for as the stationary value of the quotient , and represents variation calculus.

2.2. Basic Equations in the Direction

In order to obtain the governing differential equations about the mode functions , assume that are known. Hence, Equations (9)–(12) can be simplified as follows:

where the integral parameter has the following form:

Substituting Equation (14) into the Rayleigh quotient (13) and performing variation operations, we can obtain the governing differential equations for as follows:

where

where the dimensionless frequency is defined as follows:

The resultant BCs can also be obtained as follows:

According to Equation (19), the simply supported (S), clamped (C), and free (F) BCs of the edges of are shown in Table 1, wherein the superscripts ‘n’ and ‘t’ represent the normal and tangential directions of edges, respectively.

Table 1.

The homogeneous boundary conditions of the edges of .

Eliminating any two functions of , , and from Equation (16) generates the following equation:

where the coefficients are as follows:

Substituting the solution , where is the spatial eigenvalue in the direction, into Equation (20) yields the following characteristic equation:

It can be seen from Equations (17) and (21) that the coefficients are functions of , so is also a function of . Given a , the eight roots of can be obtained by the Ferrari formula. Letting then can be expressed as follows:

where are unknown constants. Substituting Equation (23) into Equation (16), the relations between these constant coefficients can be found as follows:

It can be seen from Equation (24) that there are eight unknowns, , which can be determined via the BCs of the edges as shown in Table 1.

Substituting Equation (23) into the BCs of the edges yields eight homogeneous linear equations for , as follows:

where is a matrix of and

The existence of nontrivial solutions for and requires that the determinant of the coefficient matrix must be zero, i.e.,

which is a transcendental equation with respect to . After solving for , and can then be obtained from Equation (25).

2.3. Basic Equations in the Direction

Similar to the derivation performed in Section 2.2, the basic equations in the direction can be obtained by assuming are known. In this case, the amplitudes of the kinetic and potential energy shown in Equations (9)–(12) change to the following:

where the integral coefficient is defined as follows:

Substituting Equation (28) into the Rayleigh quotient (13) generates the following governing differential equations about :

where

The obtained BCs for the edges of are as follows:

which are shown in Table 2 for the simply supported, clamped, and free BCs.

Table 2.

The homogeneous boundary conditions of the edges .

From Equation (30), we obtain the following:

where the coefficients are as follows:

The characteristic equation of Equation (33) has the following form:

According to Equations (31) and (34), the coefficients are functions of frequency . With a specific frequency , the eight roots, , can be obtained from the Ferrari formula, and the general solutions of the mode function can be expressed as follows:

where , are unknown coefficients that are determined by boundary conditions in edges . Introducing Equation (36) into Equation (30) yields the following:

In order to achieve the solutions of coefficients and , substituting Equations (36) and (37) into the boundary conditions in edges as shown in Table 2 leads to eight homogeneous linear equations for the coefficients , i.e.,

where is a matrix of size and

For a nontrivial solution of , a transcendental equation with respect to the frequency is generated by requiring the determinant of to be zero, i.e.,

and with a specific frequency , the nonzero and can also be obtained from Equation (38).

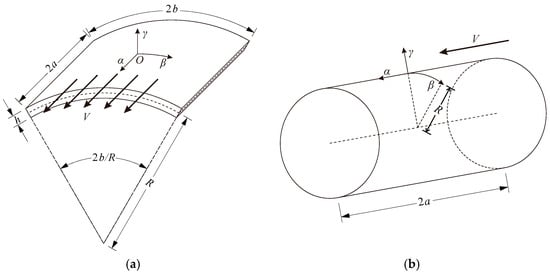

3. Basic Equations of Flutter

Consider an open and a closed circular cylindrical shell subjected to axial airflow with velocity as shown in Figure 2. The dimension, material, and coordinate system of the cylindrical shells defined in Section 2 are also used here. In the following, the governing differential equation for the cylindrical shells under aerodynamic load is derived from the general form of the Hamilton principle, and then the equation is solved using the SOV method.

Figure 2.

Cylindrical shell under aerodynamic pressure. (a) Open cylindrical shell. (b) Middle surface of a closed cylindrical shell.

The general form of the Hamilton principle is as follows:

where and are two time points, the kinetic energy and the potential energy are given in Equations (2)–(5), and the integration of the external virtual work has the following form:

where the aerodynamic pressure P is determined by the first-order piston theory and has the following form [29,35]:

where , and are the Mach number, the sound speed, the freestream static pressure, and the adiabatic exponent of the airflow, respectively. For sufficiently high Mach numbers, a different version of Equation (43), which was derived by Krumhaar [25], is as follows:

where is the density of the airflow.

By substituting Equations (2)–(5) and Equation (42) into Equation (41) and then performing partial integration of and with respect to time and spatial variable , respectively, one can obtain the following governing differential equations for

The obtained BCs for the edges of and are as follows:

The obtained BCs at four corners are as follows:

The simply supported BCs at the edges have the following forms:

where

As far as the open cylindrical shell with simply supported BCs at the edges is concerned, the Levy type of solution for Equation (45) has the following forms:

where is a complex eigenvalue and . It is obvious that Equation (51) satisfies the simply supported boundary conditions in edges and the corner boundary condition naturally. As for the closed cylindrical shell, the BCs of edges are replaced by periodical continuity conditions, and the solution has the following form:

According to Equation (46), the homogeneous BCs of edges for the open and closed cylindrical shells are given in Table 3.

Table 3.

The homogeneous boundary conditions of axial edges .

Substituting Equation (51) into Equation (45) yields the ordinary differential governing equations for , and as follows:

where the dimensionless parameters are defined as follows:

and the dimensionless aerodynamic parameters are as follows:

where , and denote the aerodynamic stiffness, aerodynamic damping, and curvature correction, respectively. When the aerodynamic pressure is calculated by Equation (44), the aerodynamic parameters in Equation (55) can be simplified as follows:

For closed circular cylindrical shells, one just needs to replace with in Equation (54).

Eliminating any two functions of , , and from Equation (53) yields the following:

where the coefficients are as follows:

The characteristic equation of Equation (57) can be expressed as follows:

Since the coefficients are functions of , the spatial eigenvalue can be obtained by numerical methods for a specific . With the eight eigenvalues, , the general solution of Equation (57) can be written as follows:

Substituting Equation (60) into Equation (53) yields the relations among as follows:

where can be determined by the BCs of edges . By substituting Equation (60) into the BCs shown in Table 3, one can obtain eight homogeneous linear equations for , as follows:

where is a matrix with the size of and

The existence of nontrivial solutions for requires the following:

which leads to a transcendental equation with respect to . For an obtained , the nonzero can be obtained from Equation (62).

4. Solution Procedures

For free vibration, the open cylindrical shell with arbitrary combinations of homogeneous BCs is considered, and the transcendental equations about the natural frequency in the direction and the direction are Equation (27) and Equation (40), respectively.

As for the flutter, the open cylindrical shell with simply supported circumferential edges and the closed cylindrical shell are taken into account, and the transcendental equation about the flutter eigenvalue is Equation (64).

This section aims to find satisfying both Equation (27) and Equation (40) and satisfying Equation (64).

4.1. Solving Method for Free Vibration

Using the iSOV method [45], the procedure for solving the natural frequency is presented as follows:

- Assume that , wherein are given initial values.

- Substituting into or Equation (15), the root of Equation (27) can be obtained by the Newton–Raphson method or the bisection method. With a specific frequency , solving or Equation (25) yields the mode functions .

- Since are solved, the root of equation or Equation (40) can be achieved by the Newton–Raphson method or the bisection method. With a specific frequency , solving or Equation (38) yields the mode functions .

- If , wherein is satisfied, then the iteration stops. Otherwise, update using the results obtained in Step (3) and go back to Step (2).

Generally, the exact mode function for simply supported BCs at the edges can be chosen as the initial mode functions , i.e.,

4.2. Solving Method for Flutter

Assuming , wherein the real number denotes the variation in amplitude and the real number represents the frequency, substituting into Equation (64) yields the following equation:

Equation (66) is equivalent to the following:

The expressions of and are implicit. But if and are given, one can attain the values of and so that the Newton–Raphson method, in which local derivatives are approximated by numerical differences, can be used to solve Equation (67). If , where , wherein k is the iteration times, then the iteration stops.

5. Numerical Results

The numerical results of the free vibration and flutter of circular cylindrical shells are presented and discussed in this section. The subscript is used to distinguish different and , i.e., and , where and denote the “mth” mode in the direction and the “nth” mode in the direction, respectively. In addition, denotes the order of a frequency from lower to higher. The cylindrical shells are stated by specifying the support type for the edges, starting with edge and proceeding in the counterclockwise direction by looking down to the upper surface of the shell from above; refer to Figure 1. For instance, CSFS defines an open cylindrical shell with the clamped (C) edge , the simply supported (S) edge , the free (F) edge , and the simply supported (S) edge . In addition, SF represents a closed cylindrical shell with a simply supported edge and a free edge .

Unless otherwise specified, the parameters of the shell and airflow are defined as and , respectively, and the aerodynamic pressure is calculated by Equation (44): . The physical parameters of the orthotropic material (unidirectional carbon-fiber composite) are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

The material property of unidirectional carbon-fiber composite.

5.1. Numerical Results for Free Vibration

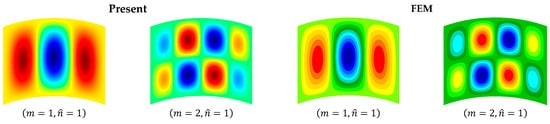

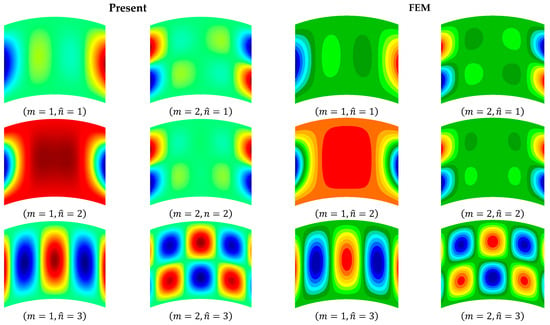

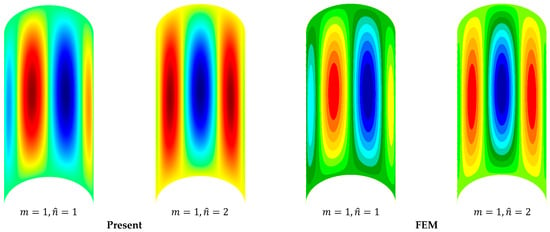

Considering the CCCC and CFCF circular cylindrical shells, Table 5 compares the present frequencies with the FEM’s results obtained by Nastran with a mesh of , and the shell elements are used to model the cylindrical shell structure. The present results agree well with those of the FEM, with a relative difference of less than , but the present frequencies are slightly larger. The principal reason for this phenomenon is the present assumption that the mode functions have a separation-of-variable form. Moreover, the different shell theories used in the present work and the FEM also contribute to the difference. In addition, the present transverse deflection modes are validated by comparing them with those of the FEM, as shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4.

Table 5.

The natural frequencies of the CCCC and CFCF laminated cylindrical shells (Hz).

Figure 3.

The transverse deflection modes of the CCCC laminated cylindrical shell.

Figure 4.

The transverse deflection modes of the CFCF laminated cylindrical shell.

Preparing for the flutter analysis of cylindrical shells, the dimensionless natural frequencies of the SSSS, SCSC, and CSFS cylindrical shells are presented in Table 6 and Table 7. Note that the exact frequencies of the SSSS cylindrical shell shown in Table 6 are obtained by the solution procedure presented in [2]. It follows that the present results for the SSSS shell are also exact, and the FEM’s frequencies are a little smaller.

Table 6.

The natural frequencies of the SSSS laminated cylindrical shell.

Table 7.

The natural frequencies of the CSCS and CSFS laminated cylindrical shells.

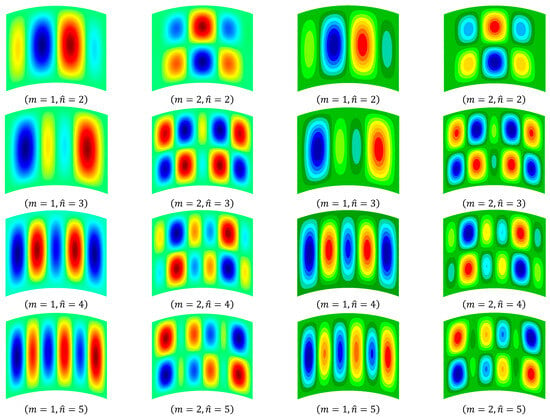

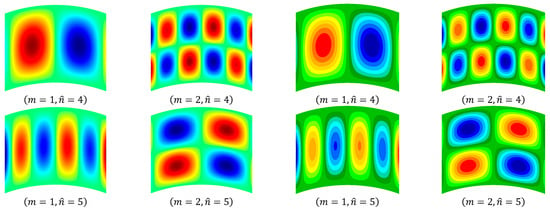

In addition, the transverse deflection modes of the SCSC and CSFS cylindrical shells are plotted in Figure 5 and Figure 6, respectively. The present results are in good agreement with those of the FEM.

Figure 5.

The transverse deflection modes of the CSCS laminated cylindrical shell.

Figure 6.

The transverse deflection modes of the CSFS laminated cylindrical shell.

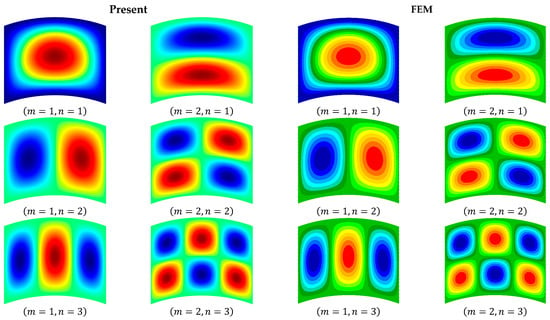

In order to further validate the present work, an isotropic shell is also considered, and the material parameters and the size of the shell are . The present results for the SCSC and SFSF cylindrical shells are compared with the exact results [2] and those of the FEM in Table 8 and Figure 7, respectively. In general, the present results are consistent with the exact results. In fact, when the open cylindrical shell has simply supported opposite edges, the iSOV method used in this work yields the Levy type of exact solutions [47]. But for the SFSF shell, the difference between the present results and the exact ones is more obvious, which is caused by the difference between the free BCs used in this work and those in [2].

Table 8.

The natural frequencies of the SCSC and SFSF isotropic cylindrical shells ().

Figure 7.

The transverse deflection modes of the SCSC isotropic cylindrical shell ().

5.2. Numerical Results for Flutter

For flat panels, flutter is generally caused by lower frequencies coalescing. However, due to the existence of curvature, higher frequency coalescing is liable to lower flutter speed for cylindrical shells. In addition, the modes with more waves for a flat panel usually correspond to higher frequencies, but this rule fails for cylindrical shells. For instance, Table 6 presents the natural frequencies of the SSSS cylindrical shell, from which one can see that the natural frequencies first decrease with the number of the circumferential waves and then increase.

- (1)

- The case of the SSSS open laminated cylindrical shell

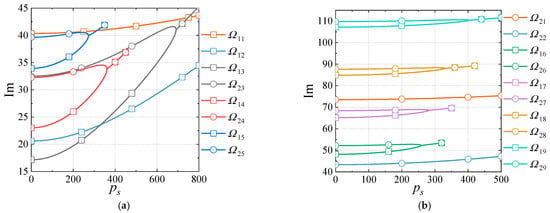

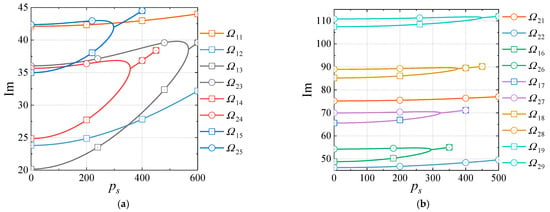

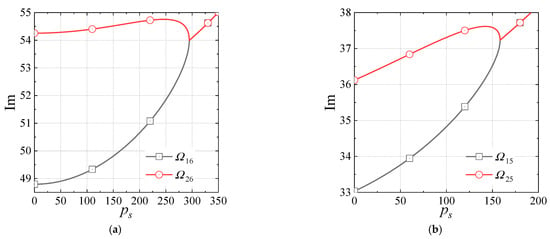

Considering the SSSS laminated cylindrical shell under the aerodynamic load, the relationships between the complex eigenvalue and the aerodynamic stiffness are shown in Figure 8 and Figure 9, wherein “Im” and “Re” represent the imaginary and the real part, respectively. ‘Re()’ denotes the variation in amplitude, and ‘Im()’ represents the frequency. Figure 8 indicates that Im() and Im() tend to coalesce with the increase in , caused by the axial airflow, and for different , Im() and Im() coalesce earlier than other eigenvalues.

Figure 8.

Relationships between and for the SSSS laminated cylindrical shell ( and ). (a) The imaginary parts of . (b) The imaginary parts of .

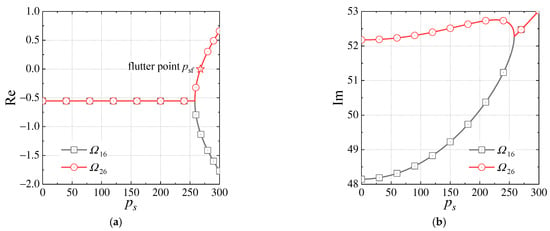

Figure 9.

Relationships between , and for the SSSS laminated cylindrical shell. (a) The real parts of and , where ‘☆’ denotes the flutter point. (b) The imaginary parts of and .

In order to present more detail about the variations in , the variations in and are plotted again in Figure 9. It can be seen that increases with , but first increases with and then decreases, gradually approaching ; when is small, and are constants less than zero, implying that vibration is decaying before flutter. When and coincide, and change dramatically in reverse directions. If is greater than 0, flutter occurs, and corresponding to is the flutter point, denoted as .

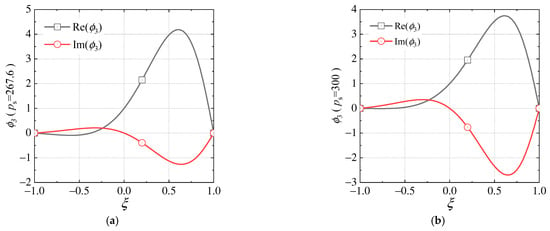

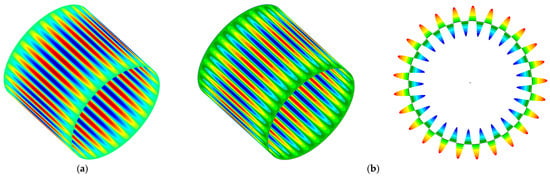

Figure 10 shows the transverse deflection flutter mode corresponding to in and in . The peaks of are postponed by the airflow. There are numerous sets of , but is normalized by dividing by to make in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Flutter modes for the SSSS laminated cylindrical shell. (a) corresponding to and . (b) corresponding to and .

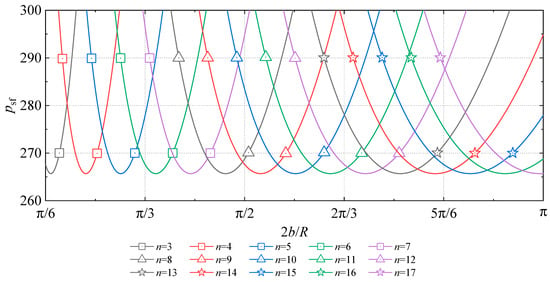

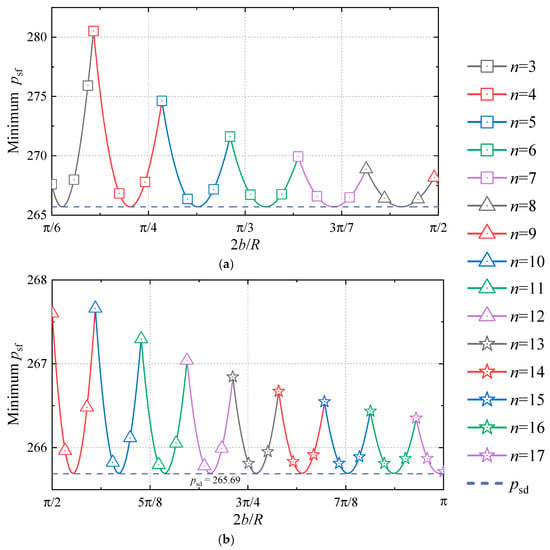

Moreover, also for the SSSS cylindrical shell, the relationships between the dimensionless circumferential length and the flutter points caused by the different coalescing of and () are depicted in Figure 11. For a specific , first decreases with and then increases, inducing the phenomenon that the corresponding to the minimum flutter point (also called the critical flutter point) increases with . Only retaining the minimum flutter points, the relationships between and are replotted in Figure 12. Notably, the minimum flutter points have an infimum , independent of .

Figure 11.

The flutter points caused by and

( and n = 3~17).

Figure 12.

The minimum flutter points caused by and with different ( and ). (a) . (b) .

- (2)

- The case of the CSCS and CSFS open laminated cylindrical shells

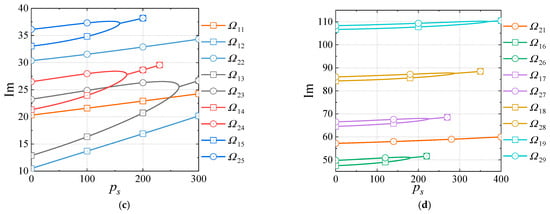

For the CSCS and CSFS laminated cylindrical shells, the natural frequencies are given in Table 7. Considering the aerodynamic load, the relationships between and are shown in Figure 13, wherein Im( for CSCS and Im( for CSFS coalesce earlier. The detailed variations in for CSCS and for CSFS are all given in Figure 14.

Figure 13.

Relationships between and for the CSCS and CSFS cylindrical shells. (a) CSCS. (b) CSCS. (c) CSFS. (d) CSFS.

Figure 14.

Variations in the pairs of coalescing frequencies with minimum for the CSCS and CSFS cylindrical shells. (a) CSCS. (b) CSFS.

- (3)

- The case of the SS, CC, and SF closed isotropic cylindrical shells

The closed cylindrical shell with arbitrary combinations of homogeneous BCs can also be handled by the formulae derived in Section 3. The parameters defined in [29,35] for a closed isotropic cylindrical shell are used below. The material properties of the shell are as follows:

The dimensions of the shell are as follows:

And for the airstream.

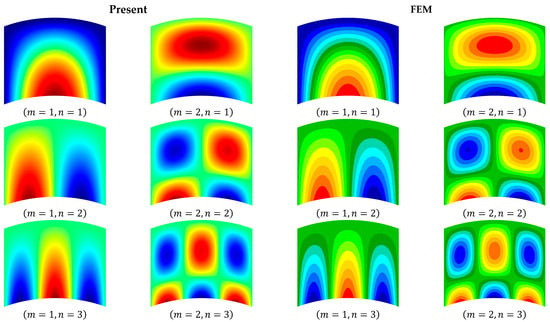

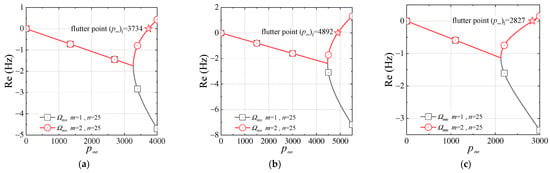

The comparison of the natural frequency and the flutter point is shown in Table 9; the natural modes are given in Figure 15, and the variations in with are presented in Figure 16. Note that, to compare with the results in [35], Equation (43) is also used here. In addition, the present natural frequencies in Table 9 are obtained by neglecting the aerodynamic force, i.e., . The present frequencies are slightly less than the results in [35], whereas they are slightly larger than the results of the FEM. In addition, the present flutter points as marked by ‘☆’ in Figure 16 are larger than those in [35]. This is because the present shell theory differs from those in [35] and the FEM. In general, the present results are in good agreement with those of the referenced results.

Table 9.

The natural frequency and flutter point for the SS cylindrical shell ().

Figure 15.

The transverse deflection natural modes of the SS isotropic cylindrical shell with (a) Present. (b) FEM.

Figure 16.

The relationships between and for the closed cylindrical shell. (a) of the SS shell, where ‘☆’ denotes the flutter point. (b) of the CC shell, where ‘☆’ denotes the flutter point. (c) of the SF shell, where ‘☆’ denotes the flutter point. (d) of the SS shell. (e) of the CC shell. (f) of the SF shell.

- (4)

- The results of the Galerkin method

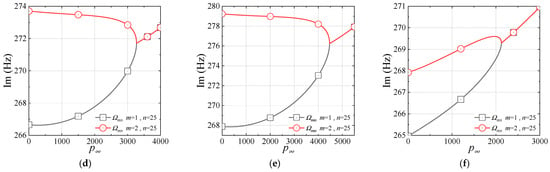

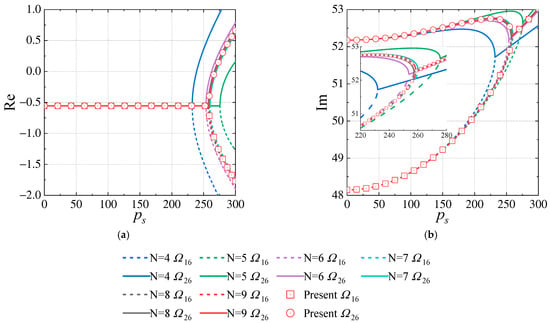

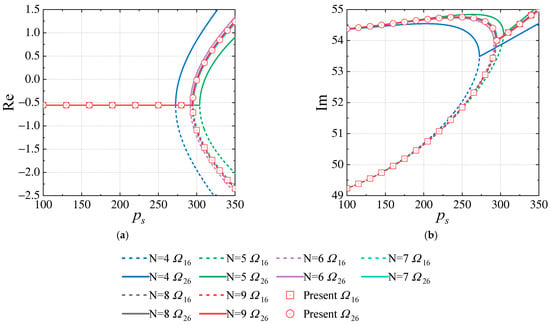

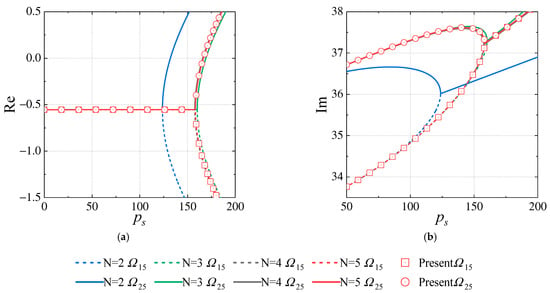

The Galerkin method has been widely used in panel flutter analysis. In order to further verify the present results, Figure 17 and Figure 18 compare the present and for the SSSS and CSCS laminated cylindrical shells with those of the Galerkin method, wherein the free vibration modes are taken as the trial functions. The formulation of the Galerkin method can be found in Appendix A. Figure 19 compares the present and of the CSFS cylindrical shell with those of the Galerkin method, in which the free vibration modes are used as the trial functions. The Galerkin method taking for the SSSS and CSCS shells agrees well with the present method, validating the accuracy of the present results. As for the CSFS shell, the Galerkin method with is accurate enough. According to Figure 17, Figure 18 and Figure 19, it follows that the frequencies coalescing in the Galerkin method is later than the present results when is odd, while it is earlier than the present results when is even.

Figure 17.

Comparison of the present method and the Galerkin method for the SSSS laminated cylindrical shell (the free vibration modes with are taken as the trial functions). (a) The real parts of and . (b) The imaginary parts of and .

Figure 18.

Comparison of the present method and the Galerkin method for the CSCS laminated cylindrical shell (the free vibration modes with are taken as the trial functions). (a) The real parts of and . (b) The imaginary parts of and .

Figure 19.

Comparison of the present method and the Galerkin method for the CSFS cylindrical shell (the free vibration modes with are taken as the trial functions). (a) The real parts of and . (b) The imaginary parts of and .

6. Conclusions

This work presented a closed-form analytical solution procedure for the free vibration of open circular cylindrical Donnell–Mushtari laminated shells. The governing differential equations were derived by the Rayleigh quotient and solved by the iterative separation-of-variable (iSOV) method. The free vibration problem of the open cylindrical shell with arbitrary combinations of homogeneous boundary conditions can be dealt with by the present method.

In addition, the exact solutions for the flutter of the laminated cylindrical shell were also obtained here. The governing differential equations of flutter were achieved by the Hamilton variational principle and solved by the SOV method. The axial aerodynamic pressure was calculated by the linear piston theory. The present method is applicable to closed cylindrical shells with arbitrary homogeneous boundary conditions and open cylindrical shells with simply supported circumferential edges and arbitrary axial edges.

The influence of the circumferential dimension on flutter characteristics was investigated for the SSSS cylindrical shell. The numerical results manifested that the number of circumferential waves in the critical flutter modes increases with circumferential length; moreover, there exists an infimum for flutter points that is independent of the circumferential length.

In order to verify the present exact solutions of the cylindrical shell flutter, the Galerkin method using the free vibration modes as trial functions was presented. It was concluded that the frequencies coalescing in the Galerkin method is later than the present results when the number of the trial functions is odd, while it is earlier than the present results when the number of the trial functions is even. The present results were also validated through comparison with the results of the finite element method, the Galerkin method, and the available literature. This work fills the gap in the research on the closed-form analytical solutions for the free vibration and flutter of the circular cylindrical shell and provides a benchmark for examining approximation methods.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcs8120493/s1, File CCCC, CFCF, SCSC: The original image of free vibration modes obtained by the present method and the FEM (Nastran) for open CCCC, CFCF, and SCSC cylindrical shells. File SS: The original image of free vibration modes obtained by the present method and the FEM (Nastran) for a closed SS cylindrical shell.

Author Contributions

Investigation, Original draft preparation, D.P. Conceptualization, Methodology, Reviewing and Editing, Y.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (12172023) is gratefully acknowledged.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest for the current study.

Appendix A

Based on the Timoshenko beam and the piston theory, the Galerkin method using the free vibration modes as trial functions has been developed to solve the beam flutter problem [48]. In the following, the Galerkin method is extended to solve the flutter problem of cylindrical shells. Neglecting the aerodynamic force in Equation (45), the governing differential equations for the free vibration of the circular cylindrical shell can be written as follows:

where the subscript is used to distinguish between the different dimensionless natural frequency and the natural modes of . As for the closed cylindrical shell and the open cylindrical shell with simply supported edges of , the exact solution procedure for the natural frequencies and modes was presented in [2,3]. In addition, based on Equation (A1), the orthogonality condition of the free vibration modes has the following forms:

Using the free vibration modes , the displacements of the cylindrical shell subjected to the aerodynamic load can be expressed as follows:

where is the number of trial functions. Substituting Equation (A3) into Equation (45) yields the following:

Introducing Equation (A1) into Equation (A4) obtains the following:

where the dimensionless time is defined as , and the aerodynamic parameters have been defined in Equation (56). By multiplying the first equation in Equation (A5) by , the second equation by , and the third equation by , and then integrating and adding the three equations together, one can obtain the following:

where . Considering Equation (A2), Equation (A6) becomes the following:

where

Substituting into Equation (A7) yields the following:

which can be rewritten as follows:

or

where ; is the unit matrix of , and

In order to obtain nontrivial solutions for , the determinant of the coefficient matrix in Equation (A10) must be zero, i.e.,

which leads to an algebraic equation of degree about so that the complex eigenvalue can be obtained numerically. In addition, can also be obtained by solving the eigenvalue Equation (A11).

References

- Zhang, L.; Xiang, Y. Vibration of Open Circular Cylindrical Shells with Intermediate Ring Supports. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2006, 43, 3705–3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Liu, B.; Xu, T. Exact Solutions for Free Vibration of Circular Cylindrical Shells with Classical Boundary Conditions. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2013, 75, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Xing, Y.F.; Qatu, M.S.; Ferreira, A.J.M. Exact Characteristic Equations for Free Vibrations of Thin Orthotropic Circular Cylindrical Shells. Compos. Struct. 2012, 94, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qatu, M.S. Vibration of Laminated Shells and Plates, 1st ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Boston, MA, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-0-08-044271-6. [Google Scholar]

- Forsberg, K. Influence of Boundary Conditions on the Modal Characteristics of Thin Cylindrical Shells. AIAA J. 1964, 2, 2150–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.L.; Haft, E.E. Natural Frequencies of Clamped Cylindrical Shells. AIAA J. 1968, 6, 720–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vronay, D.F.; Smith, B.L. Free Vibration of Circular Cylindrical Shells of Finite Length. AIAA J. 1970, 8, 601–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, J.; Baruh, H. A Closed-Form Solution Procedure for Circular Cylindrical Shell Vibrations. Int. J. Solids Struct. 1999, 36, 2973–3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, R.; Tang, J.; Wang, A.; Shuai, C.; Wang, Q. An Exact Solution for Free Vibration of Cross-Ply Laminated Composite Cylindrical Shells with Elastic Restraint Ends. Comput. Math. Appl. 2019, 77, 641–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, K.M.; Lim, C.W.; Kitipornchai, S. Vibration of Shallow Shells: A Review With Bibliography. Appl. Mech. Rev. 1997, 50, 431–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qatu, M.S. Recent Research Advances in the Dynamic Behavior of Shells: 1989-2000, Part 1: Laminated Composite Shells. Appl. Mech. Rev. 2002, 55, 325–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qatu, M.S. Recent Research Advances in the Dynamic Behavior of Shells: 1989–2000, Part 2: Homogeneous Shells. Appl. Mech. Rev. 2002, 55, 415–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qatu, M.S.; Sullivan, R.W.; Wang, W. Recent Research Advances on the Dynamic Analysis of Composite Shells: 2000–2009. Compos. Struct. 2010, 93, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrick, I.E.; Reed, W.H. Historical Development of Aircraft Flutter. J. Aircr. 1981, 18, 897–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowell, E.H. Panel Flutter—A Review of the Aeroelastic Stability of Plates and Shells. AIAA J. 1970, 8, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, C.; Abdel-Motagaly, K.; Chen, R. Review of Nonlinear Panel Flutter at Supersonic and Hypersonic Speeds. Appl. Mech. Rev. 1999, 52, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y.; Gao, W.; Ankay, B.; Li, F.; Zhang, C. Aeroelastic Analysis and Flutter Control of Wings and Panels: A Review. Int. J. Mech. Sys. Dyn. 2021, 1, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lighthill, M.J. Oscillating Airfoils at High Mach Number. J. Aeronaut. Sci. 1953, 20, 402–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, H.; Zartarian, G. Piston Theory—A New Aerodynamic Tool for the Aeroelastician. J. Aeronaut. Sci. 1956, 23, 1109–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Försching, H.W. Grundlagen Der Aeroelastik; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Gordnier, R.E.; Visbal, M.R. Development of a Three-Dimensional Viscous Aeroelastic Solver for Nonlinear Panel Flutter. J. Fluids Struct. 2002, 16, 497–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordnier, R.E.; Visbal, M.R. Computation of Three-Dimensional Nonlinear Panel Flutter. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2003, 16, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Ye, Z.; Liu, C. Nonlinear Analysis on Piston Theory. AIAA J. 2019, 57, 4583–4587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Ye, Z.; Ye, K.; Liu, C. Aerodynamic Nonlinearity of Piston Theory in Surface Vibration. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2020, 33, 04020035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumhaar, H. The Accuracy of Linear Piston Theory When Applied to Cylindrical Shells. AIAA J. 1963, 1, 1448–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, M.D.; Fung, Y.C. Supersonic Flutter of Circular Cylindrical Shells Subjected to Internal Pressure and Axial Compression. AIAA J. 1966, 4, 858–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, M.D.; Fung, Y.C. Comparing Theory and Experiment for the Supersonic Flutter of Circular Cylindrical Shells. AIAA J. 1967, 5, 1849–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evensen, D.A.; Olson, M.D. Circumferentially Traveling Wave Flutter of a Circular Cylindrical Shell. AIAA J. 1968, 6, 1522–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabili, M.; Pellicano, F. Nonlinear Supersonic Flutter of Circular Cylindrical Shells. AIAA J. 2001, 39, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabili, M.; Pellicano, F. Multimode Approach to Nonlinear Supersonic Flutter of Imperfect Circular Cylindrical Shells. J. Appl. Mech. 2002, 69, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirzadegan, S.; Dowell, E.H. Correlation of Experimental and Computational Results for Flutter of Streamwise Curved Plate. AIAA J. 2019, 57, 3556–3561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirzadegan, S.; Dowell, E.H. Nonlinear Limit Cycle Oscillation and Flutter Analysis of Clamped Curved Plates. J. Aircr. 2020, 57, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowell, E.H. Nonlinear Flutter of Curved Plates. AIAA J. 1969, 7, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, M.K.; Mandal, M. Supersonic Flutter Characteristics of Composite Cylindrical Panels. Compos. Struct. 2008, 82, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabri, F.; Lakis, A.A. Finite Element Method Applied to Supersonic Flutter of Circular Cylindrical Shells. AIAA J. 2010, 48, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudkhani, S. Aerothermoelastic Analysis of Imperfect FG Cylindrical Shells in Supersonic Flow. Compos. Struct. 2019, 225, 111160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachulo, D.; Akhavan, H.; Ribeiro, P. Supersonic Flutter of Variable Stiffness Circular Cylindrical Shells. Compos. Struct. 2023, 313, 116927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochkarev, S.A.; Lekomtsev, S.V.; Matveenko, V.P. Finite Element Analysis of the Panel Flutter of Stiffened Shallow Shells. Contin. Mech. Thermodyn. 2023, 35, 1275–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y.; Song, Z.; Li, F. Investigations on the Aerothermoelastic Properties of Composite Laminated Cylindrical Shells with Elastic Boundaries in Supersonic Airflow Based on the Rayleigh–Ritz Method. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2018, 82–83, 534–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.-M.; Song, Z.-G. Aeroelastic Flutter Analysis for 2D Kirchhoff and Mindlin Panels with Different Boundary Conditions in Supersonic Airflow. Acta Mech. 2014, 225, 3339–3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Xing, Y. Exact Eigensolutions for Flutter of Two-Dimensional Symmetric Cross-Ply Composite Laminates at High Supersonic Speeds. Compos. Struct. 2018, 183, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedgepeth, J.M. Flutter of Rectangular Simply Supported Panels at High Supersonic Speeds. J. Aeronaut. Sci. 1957, 24, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugundji, J. Theoretical Considerations of Panel Flutter at High Supersonic Mach Numbers. AIAA J. 1966, 4, 1257–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Xing, Y.; Liu, B.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Z. Accurate Closed-Form Eigensolutions of Three-Dimensional Panel Flutter with Arbitrary Homogeneous Boundary Conditions. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2023, 36, 266–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Sun, Q.; Liu, B.; Wang, Z. The Overall Assessment of Closed-Form Solution Methods for Free Vibrations of Rectangular Thin Plates. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2018, 140, 455–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Xing, Y. An Extended Separation-of-Variable Method for the Eigenbuckling of Orthotropic Open Thin Circular Cylindrical Shells. Compos. Struct. 2023, 324, 117522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Xing, Y.; Wang, Z. An Extended Separation-of-Variable Method for Free Vibration of Rectangular Mindlin Plates. Int. J. Str. Stab. Dyn. 2021, 21, 2150154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.-J.; Yang, X.-D.; Zhang, W.; Liang, F.; Yang, T.-Z.; Ren, Y. Flutter Mechanism of Timoshenko Beams in Supersonic Flow. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2019, 32, 04019033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).