Biopolymer-Based Nanocomposite Scaffolds: Methyl Cellulose and Hydroxyethyl Cellulose Matrix Enhanced with Osteotropic Metal Carbonate Nanoparticles (Ca, Zn, Mg, Cu, Mn) for Potential Bone Regeneration

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Chemicals

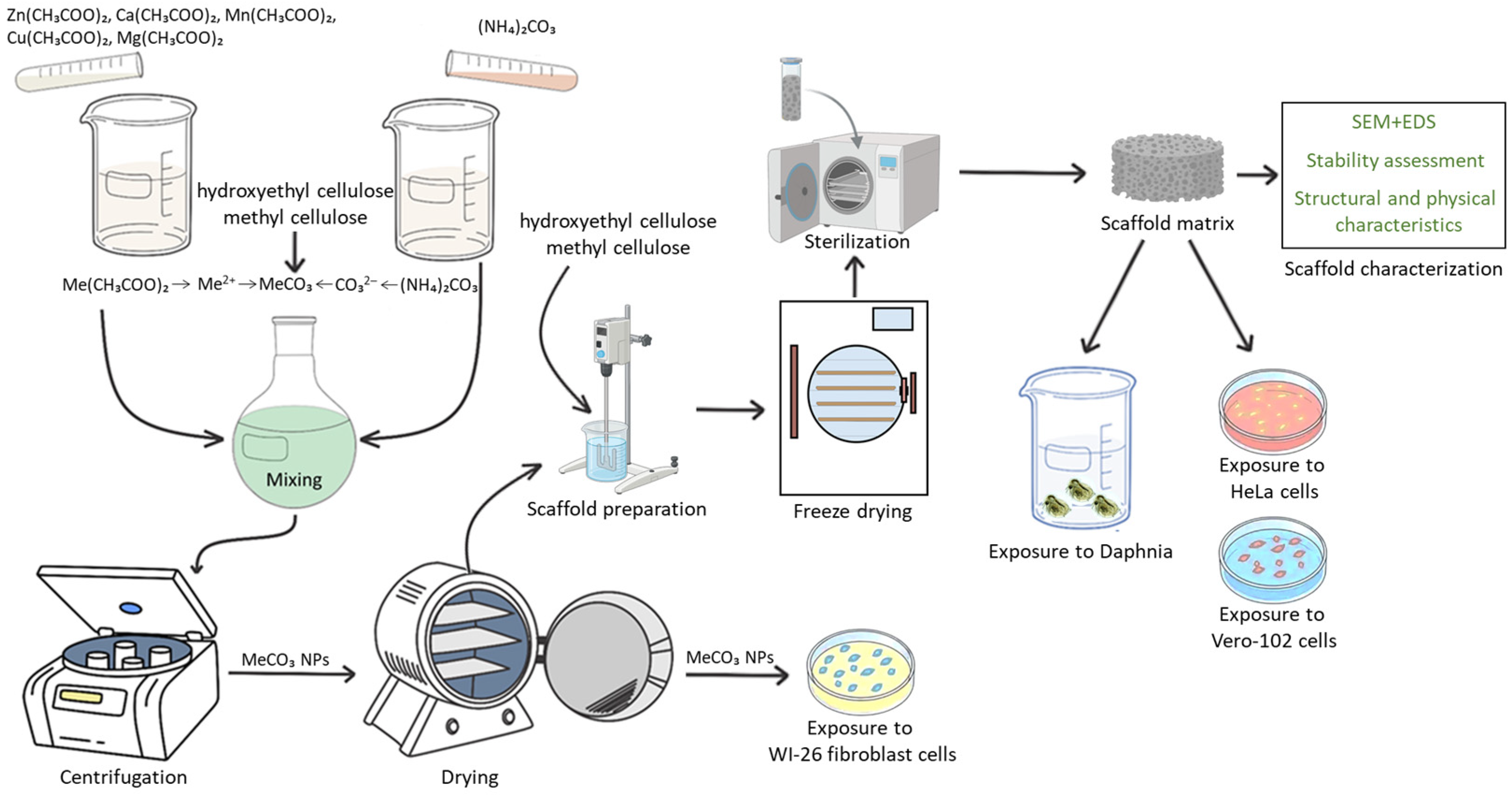

2.2. Synthesis of NPs

2.3. Synthesis of the Biopolymer Scaffold Matrices Modified with NPs

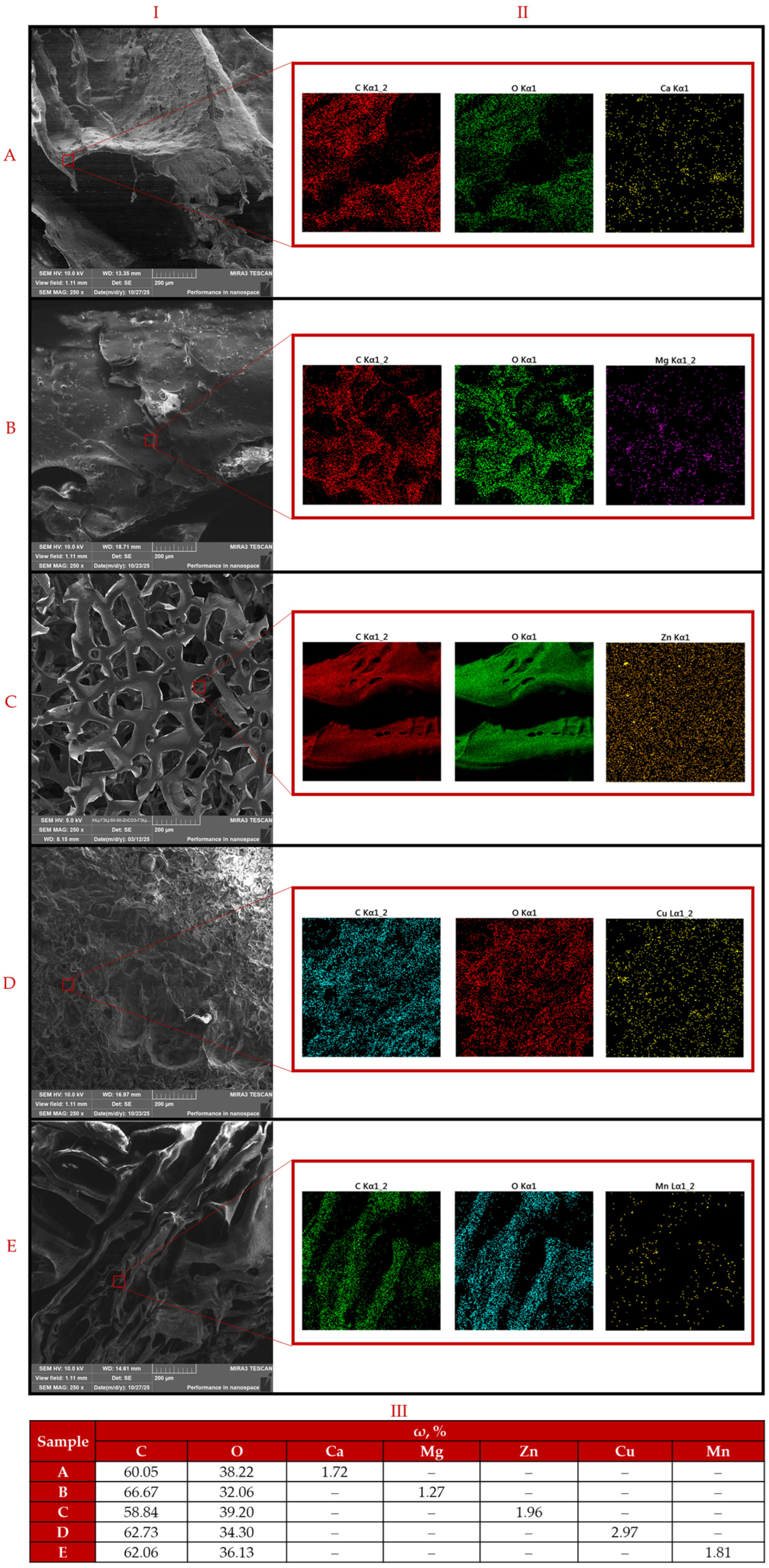

2.4. Characterization Methods

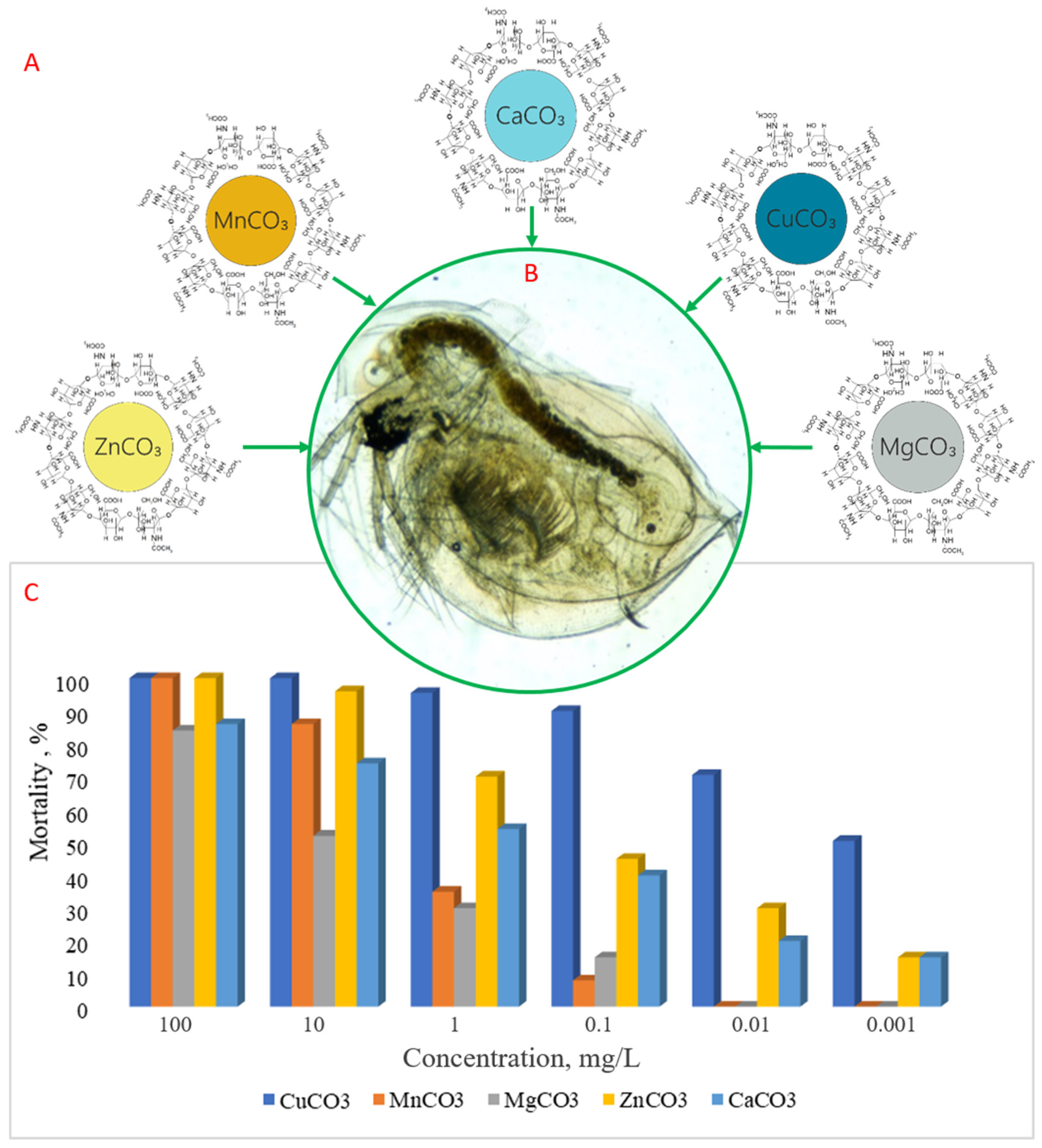

2.5. Acute Toxicity Assessment

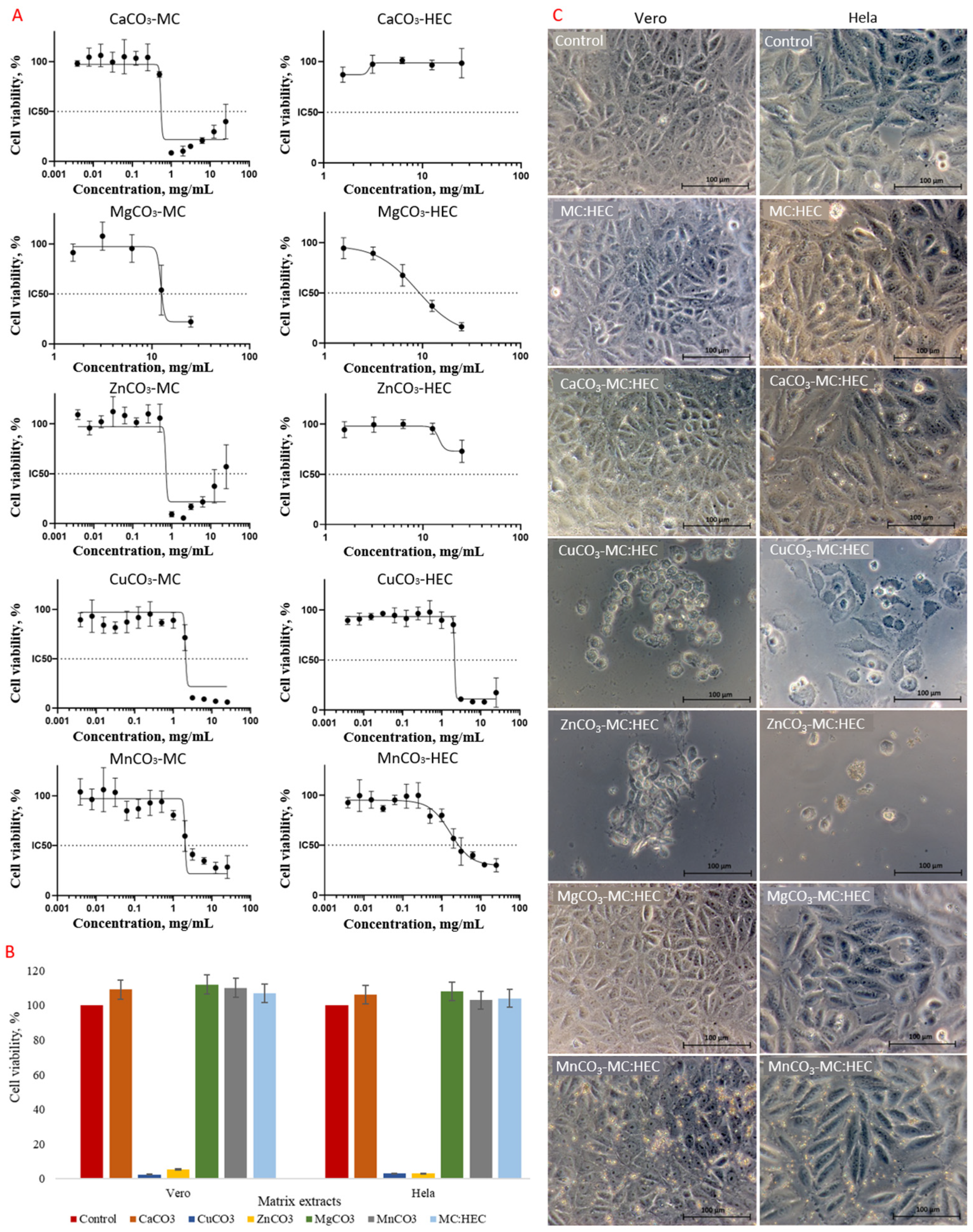

2.6. Cytotoxicity Assessment of NPs in Scaffold Matrices

2.7. Statistical Data Processing

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of Samples

3.2. Acute Toxicity Assessment

3.3. Cytotoxicity Assessment of NPs in Scaffold Matrices

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, A.-M.; Bisignano, C.; James, S.L.; Abady, G.G.; Abedi, A.; Abu-Gharbieh, E.; Alhassan, R.K.; Alipour, V.; Arabloo, J.; Asaad, M.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Bone Fractures in 204 Countries and Territories, 1990–2019: A Systematic Analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2021, 2, e580–e592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farr, J.N.; Melton, L.J., III; Achenbach, S.J.; Atkinson, E.J.; Khosla, S.; Amin, S. Fracture Incidence and Characteristics in Young Adults Aged 18 to 49 Years: A Population-Based Study. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2017, 32, 2347–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faris, M.; Lystad, R.P.; Harris, I.; Curtis, K.; Mitchell, R. Fracture-Related Hospitalisations and Readmissions of Australian Children ≤16 Years: A 10-Year Population-Based Cohort Study. Injury 2020, 51, 2172–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciancia, S.; van Rijn, R.R.; Högler, W.; Appelman-Dijkstra, N.M.; Boot, A.M.; Sas, T.C.J.; Renes, J.S. Osteoporosis in Children and Adolescents: When to Suspect and How to Diagnose It. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2022, 181, 2549–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, A.E.; Meijer, O.C.; Winter, E.M. The Multi-Faceted Nature of Age-Associated Osteoporosis. Bone Rep. 2024, 20, 101750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogliari, G.; Ong, T.; Marshall, L.; Sahota, O. Seasonality of Adult Fragility Fractures and Association with Weather: 12-Year Experience of a UK Fracture Liaison Service. Bone 2021, 147, 115916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jedynasty, K.; Zięba, M.; Adamski, J.; Czech, M.; Głuszko, P.; Gozdowski, D.; Szypowska, A.; Śliwczyński, A.; Walicka, M.; Franek, E. Seasonally Dependent Change of the Number of Fractures after 50 Years of Age in Poland—Analysis of Combined Health Care and Climate Datasets. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBoff, M.S.; Greenspan, S.L.; Insogna, K.L.; Lewiecki, E.M.; Saag, K.G.; Singer, A.J.; Siris, E.S. The Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Osteoporos. Int. 2022, 33, 2049–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vabo, S.; Steen, K.; Brudvik, C.; Hunskaar, S.; Morken, T. Patient-Reported Outcomes after Initial Conservative Fracture Treatment in Primary Healthcare—A Survey Study. BMC Prim. Care 2022, 23, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pommier, B.; Ollier, E.; Pelletier, J.-B.; Castel, X.; Vassal, F.; Tetard, M.-C. Conservative versus Surgical Treatment for Odontoid Fracture: Is the Surgical Treatment Harmful? Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World Neurosurg. 2020, 141, 490–499.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, H.-T.; Jo, Y.-H.; Kang, H.-J. Comparison of Minimally Invasive Plate Osteosynthesis (MIPO) and Open Reduction and Internal Fixation (ORIF) for the Treatment of Radial Shaft Fractures: A Retrospective Study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2025, 26, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, Y.; Kamimura, M.; Ito, K.; Koguchi, M.; Tanaka, H.; Kurishima, H.; Koyama, T.; Mori, N.; Masahashi, N.; Aizawa, T. A Review of the Impacts of Implant Stiffness on Fracture Healing. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Gong, Y.; Zhou, G.; Ren, W.; Wang, X. Biodegradable Implants for Internal Fixation of Fractures and Accelerated Bone Regeneration. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 27920–27931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baertl, S.; Alt, V.; Rupp, M. Surgical Enhancement of Fracture Healing—Operative vs. Nonoperative Treatment. Injury 2021, 52, S12–S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menezes, R.; Vincent, R.; Osorno, L.; Hu, P.; Arinzeh, T.L. Biomaterials and Tissue Engineering Approaches Using Glycosaminoglycans for Tissue Repair: Lessons Learned from the Native Extracellular Matrix. Acta Biomater. 2023, 163, 210–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salbach-Hirsch, J.; Samsonov, S.A.; Hintze, V.; Hofbauer, C.; Picke, A.-K.; Rauner, M.; Gehrcke, J.-P.; Moeller, S.; Schnabelrauch, M.; Scharnweber, D.; et al. Structural and Functional Insights into Sclerostin-Glycosaminoglycan Interactions in Bone. Biomaterials 2015, 67, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farjaminejad, S.; Farjaminejad, R.; Hasani, M.; Garcia-Godoy, F.; Abdouss, M.; Marya, A.; Harsoputranto, A.; Jamilian, A. Advances and Challenges in Polymer-Based Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering: A Path Towards Personalized Regenerative Medicine. Polymers 2024, 16, 3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, E.A.; Mirsky, N.A.; Silva, B.L.G.; Shinde, A.R.; Arakelians, A.R.L.; Nayak, V.V.; Marcantonio, R.A.C.; Gupta, N.; Witek, L.; Coelho, P.G. Functional Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Regeneration: A Comprehensive Review of Materials, Methods, and Future Directions. J. Funct. Biomater. 2024, 15, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Luo, D.; Liu, Y. Effect of the Nano/Microscale Structure of Biomaterial Scaffolds on Bone Regeneration. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2020, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.S.; Cabral, J.M.S.; da Silva, C.L.; Vashishth, D. Bone Matrix Non-Collagenous Proteins in Tissue Engineering: Creating New Bone by Mimicking the Extracellular Matrix. Polymers 2021, 13, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, F.; Yu, Y.; Liu, S.; Ming, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Zhao, J.; Jin, Y. Advancing Application of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Based Bone Tissue Regeneration. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 6, 666–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, Q.; Wan, J.; Cao, Q.; Guo, Z.; Tang, K.; Chen, X.; Lou, Q.; Xu, X.; Fu, Y.; et al. Mineralized Extracellular Matrix Composite Scaffold Incorporated with Salvianolic Acid A Enhances Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cell Osteogenesis and Promotes Calvarial Bone Regeneration. Biomater. Adv. 2025, 175, 214327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Patil, S.; Gao, Y.-G.; Qian, A. The Bone Extracellular Matrix in Bone Formation and Regeneration. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Mouser, V.H.M.; Roumans, N.; Moroni, L.; Habibovic, P. Biomimetic Mechanically Strong One-Dimensional Hydroxyapatite/Poly(D,L-Lactide) Composite Inducing Formation of Anisotropic Collagen Matrix. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 17480–17498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavoni, M.; Dapporto, M.; Tampieri, A.; Sprio, S. Bioactive Calcium Phosphate-Based Composites for Bone Regeneration. J. Compos. Sci. 2021, 5, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, F.A. Revisiting the Physical and Chemical Nature of the Mineral Component of Bone. Acta Biomater. 2025, 196, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Euw, S.; Wang, Y.; Laurent, G.; Drouet, C.; Babonneau, F.; Nassif, N.; Azaïs, T. Bone Mineral: New Insights into Its Chemical Composition. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurul, F.; Turkmen, H.; Cetin, A.E.; Topkaya, S.N. Nanomedicine: How Nanomaterials Are Transforming Drug Delivery, Bio-Imaging, and Diagnosis. Next Nanotechnol. 2025, 7, 100129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinov, A.; Rekhman, Z.; Slyadneva, K.; Askerova, A.; Mezentsev, S.; Lukyanov, G.; Kirichenko, I.; Djangishieva, S.; Gamzatova, A.; Suptilnaya, D.; et al. Advanced Strategies for the Selection and Stabilization of Osteotropic Micronutrients Using Biopolymers. J. Chem. Rev. 2025, 7, 83–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jan, H.; Zhong, Z.; Zhou, L.; Teng, K.; Chen, Y.; Xu, J.; Xie, D.; Chen, D.; Xu, J.; et al. Multiscale Metal-Based Nanocomposites for Bone and Joint Disease Therapies. Mater. Today Bio 2025, 32, 101773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, L.; Antunović, M.; Ivanković, H.; Ivanković, M. Biomimetic Scaffolds Based on Mn2+-, Mg2+-, and Sr2+-Substituted Calcium Phosphates Derived from Natural Sources and Polycaprolactone. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farjaminejad, S.; Farjaminejad, R.; Garcia-Godoy, F. Nanoparticles in Bone Regeneration: A Narrative Review of Current Advances and Future Directions in Tissue Engineering. J. Funct. Biomater. 2024, 15, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhen, C.; Yang, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Fang, Y.; Shang, P. Recent Advances of Nanoparticles on Bone Tissue Engineering and Bone Cells. Nanoscale Adv. 2024, 6, 1957–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkhenany, H. Emerging Nanomaterials Capable of Effectively Facilitating Osteoblast Maturation. Nanomedicine 2025, 20, 1603–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, Z.; Pang, Y.; Zhou, H. The Interaction between Nanoparticles and Immune System: Application in the Treatment of Inflammatory Diseases. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 20, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Qiao, W.; Liu, Y.; Yao, X.; Zhai, Y.; Du, L. Addressing the Challenges of Infectious Bone Defects: A Review of Recent Advances in Bifunctional Biomaterials. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2025, 23, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Xu, F.; Cao, J.; Dou, Q.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Yang, L.; Chen, W. Research Advances of Nanomaterials for the Acceleration of Fracture Healing. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 31, 368–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, J.; Hou, Y.; Chen, M.; Zheng, Z.; Meng, X.; Liu, L.; Huo, S.; Liu, S.; Zhang, H. Nanomaterials for Anti-Infection in Orthopedic Implants: A Review. Coatings 2024, 14, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janmohammadi, M.; Nazemi, Z.; Salehi, A.O.M.; Seyfoori, A.; John, J.V.; Nourbakhsh, M.S.; Akbari, M. Cellulose-Based Composite Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering and Localized Drug Delivery. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 20, 137–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rzhepakovsky, I.; Piskov, S.; Avanesyan, S.; Sizonenko, M.; Timchenko, L.; Anfinogenova, O.; Nagdalian, A.; Blinov, A.; Denisova, E.; Kochergin, S.; et al. Composite of Bacterial Cellulose and Gelatin: A Versatile Biocompatible Scaffold for Tissue Engineering. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 256, 128369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, P.; Wang, K.; Shuai, Y.; Peng, S.; Hu, Y.; Shuai, C. Hydroxyapatite Nanoparticles in Situ Grown on Carbon Nanotube as a Reinforcement for Poly (ε-Caprolactone) Bone Scaffold. Mater. Today Adv. 2022, 15, 100272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinov, A.; Nagdalian, A.; Rzhepakovsky, I.; Rekhman, Z.; Askerova, A.; Agzamov, V.; Kayumov, U.; Tairov, D.; Ibrahimov, S.; Sayahov, I. Assessment of Biocompatibility and Toxicity of Basic Copper Carbonate Nanoparticles Stabilized with Biological Macromolecules. J. Med. Pharm. Chem. Res. 2025, 7, 1747–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Sapna, D.; Kaur, B.; Baljinder. Cellulose-based nanocomposite hydrogels with metal nanoparticles. In Cellulose-Based Hydrogells; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 113–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yusoff, M.; Khairuddin, N.A.A.C.M.; Roslan, N.A.; Razali, M.H. Antibacterial TiO2 Nanoparticles and Hydroxyapatite Loaded Carboxymethyl Cellulose Bio-Nanocomposite Scaffold for Wound Dressing Application. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2025, 340, 130835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahal, S.; Hussain, F.S.J.; Kumar, A.; Rasad, M.S.B.A.; Yusoff, M.M. Fabrication, Characterization and in Vitro Biocompatibility of Electrospun Hydroxyethyl Cellulose/Poly (Vinyl) Alcohol Nanofibrous Composite Biomaterial for Bone Tissue Engineering. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2016, 144, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, N. Inorganic-Based Nanoparticles and Biomaterials as Biocompatible Scaffolds for Regenerative Medicine and Tissue Engineering: Current Advances and Trends of Development. Inorganics 2024, 12, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, M.W.; Sabri, S.; Umar, A.; Khan, M.S.; Abbas, M.Y.; Khan, M.U.; Wajid, M. Exploring the Antibiotic Potential of Copper Carbonate Nanoparticles, Wound Healing, and Glucose-Lowering Effects in Diabetic Albino Mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2025, 754, 151527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, T.E.L.; Łapa, A.; Samal, S.K.; Declercq, H.A.; Schaubroeck, D.; Mendes, A.C.; der Voort, P.V.; Dokupil, A.; Plis, A.; De Schamphelaere, K.; et al. Enzymatic, Urease-Mediated Mineralization of Gellan Gum Hydrogel with Calcium Carbonate, Magnesium-Enriched Calcium Carbonate and Magnesium Carbonate for Bone Regeneration Applications. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2017, 11, 3556–3566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popova, V.K.; Pyshnyi, D.V.; Dmitrienko, E.V. Biomedical Applications of Calcium Carbonate Nanoparticles: A Review of Recent Advances. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2025, 11, 6359–6385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd-Elkawi, M.; Sharshar, A.; Misk, T.; Elgohary, I.; Gadallah, S. Effect of Calcium Carbonate Nanoparticles, Silver Nanoparticles and Advanced Platelet-Rich Fibrin for Enhancing Bone Healing in a Rabbit Model. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 15232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoš, M.; Suchý, T.; Foltán, R. Note on the Use of Different Approaches to Determine the Pore Sizes of Tissue Engineering Scaffolds: What Do We Measure? BioMed. Eng. Online 2018, 17, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutlusoy, T.; Oktay, B.; Apohan, N.K.; Süleymanoğlu, M.; Kuruca, S.E. Chitosan-Co-Hyaluronic Acid Porous Cryogels and Their Application in Tissue Engineering. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 103, 366–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaru, I.I.; Mihai, D.P.; Olaru, O.T.; Gird, C.E.; Zanfirescu, A.; Stancov, G.; Andrei, C.; Luta, E.-A.; Nitulescu, G.M. Comparative Toxicological Evaluation of Solubilizers and Hydrotropic Agents Using Daphnia Magna as a Model Organism. Environments 2025, 12, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, F.; Zhao, N.; Yin, G.; Wang, T.; Jv, X.; Han, S.; An, L. Rapid Response of Daphnia Magna Motor Behavior to Mercury Chloride Toxicity Based on Target Tracking. Toxics 2024, 12, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Fuente-Jiménez, J.L.; Rodríguez-Rivas, C.I.; Mitre-Aguilar, I.B.; Torres-Copado, A.; García-López, E.A.; Herrera-Celis, J.; Arvizu-Espinosa, M.G.; Garza-Navarro, M.A.; Arriaga, L.G.; García, J.L.; et al. A Comparative and Critical Analysis for In Vitro Cytotoxic Evaluation of Magneto-Crystalline Zinc Ferrite Nanoparticles Using MTT, Crystal Violet, LDH, and Apoptosis Assay. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Sun, L.; Gu, Z.; Li, W.; Guo, L.; Ma, S.; Guo, L.; Zhang, W.; Han, B.; Chang, J. N-Carboxymethyl Chitosan/Sodium Alginate Composite Hydrogel Loading Plasmid DNA as a Promising Gene Activated Matrix for in-Situ Burn Wound Treatment. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 15, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukasheva, F.; Adilova, L.; Dyussenbinov, A.; Yernaimanova, B.; Abilev, M.; Akilbekova, D. Optimizing Scaffold Pore Size for Tissue Engineering: Insights across Various Tissue Types. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1444986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picado-Tejero, D.; Mendoza-Cerezo, L.; Rodríguez-Rego, J.M.; Carrasco-Amador, J.P.; Marcos-Romero, A.C. Recent Advances in 3D Bioprinting of Porous Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering: A Narrative and Critical Review. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yapa, P.; Munaweera, I. Functionalized Nanoporous Architectures Derived from Sol–Gel Processes for Advanced Biomedical Applications. J. Mater. Chem. B 2025, 13, 10715–10742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suamte, L.; Tirkey, A.; Barman, J.; Jayasekhar Babu, P. Various Manufacturing Methods and Ideal Properties of Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering Applications. Smart Mater. Manuf. 2023, 1, 100011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkhosh-Inanlou, R.; Shafiei-Irannejad, V.; Azizi, S.; Jouyban, A.; Ezzati-Nazhad Dolatabadi, J.; Mobed, A.; Adel, B.; Soleymani, J.; Hamblin, M.R. Applications of Scaffold-Based Advanced Materials in Biomedical Sensing. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2021, 143, 116342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, M.; Zhang, J.; Li, C.; Guo, C.; Wang, X.; Hu, Y.; Xu, W. Progress in Pore Design within 3D Orthopedic Scaffold Printing and an Assessment of Osseointegration—Overview Review and Critical Review. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 48, 113551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coburn, B.; Salary, R.R. Mechanical Characterization of Porous Bone-like Scaffolds with Complex Microstructures for Bone Regeneration. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuai, C.; Yang, W.; Feng, P.; Peng, S.; Pan, H. Accelerated Degradation of HAP/PLLA Bone Scaffold by PGA Blending Facilitates Bioactivity and Osteoconductivity. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 6, 490–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Dan, X.; Chen, H.; Li, T.; Liu, B.; Ju, Y.; Li, Y.; Lei, L.; Fan, X. Developing Fibrin-Based Biomaterials/Scaffolds in Tissue Engineering. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 40, 597–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamrani, A.; Nasrabadi, M.H.; Halabian, R.; Ghorbani, M. A Biomimetic Multi-Layer Scaffold with Collagen and Zinc Doped Bioglass as a Skin-Regeneration Agent in Full-Thickness Injuries and Its Effects in Vitro and in Vivo. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 127163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Wu, S.; Fu, L.; Shafiq, M.; Liang, Y.; Li, P.; Wang, X.; Feng, H.; Hashim, R.; Lou, S.; et al. Composite Scaffolds Based on Egg Membrane and Eggshell-Derived Inorganic Particles Promote Soft and Hard Tissue Repair. Compos. Part B Eng. 2025, 292, 112071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaghamsi, H. Antibacterial, and Biocompatible Nanocomposites of CuCO3/MgO and Chitosan via Ball-Milling. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 5998–6010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.K.; Pavlova, S.T.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Mirica, L.M. The Effect of Cu2+ and Zn2+ on the Aβ42 Peptide Aggregation and Cellular Toxicity. Metallomics 2013, 5, 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Wu, F.; Chen, L.; Xu, B.; Feng, C.; Bai, Y.; Liao, H.; Sun, S.; Giesy, J.P.; Guo, W. Copper and Zinc, but Not Other Priority Toxic Metals, Pose Risks to Native Aquatic Species in a Large Urban Lake in Eastern China. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 219, 1069–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Vijver, M.G.; Chen, G.; Peijnenburg, W.J.G.M. Toxicity and Accumulation of Cu and ZnO Nanoparticles in Daphnia Magna. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 4657–4664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trushina, D.B.; Borodina, T.N.; Belyakov, S.; Antipina, M.N. Calcium Carbonate Vaterite Particles for Drug Delivery: Advances and Challenges. Mater. Today Adv. 2022, 14, 100214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Tian, Y.; You, J.; Hu, X.; Liu, Y. Recent Advances of Calcium Carbonate Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Wang, L.; Pei, S.; Yang, S.; Wu, J.; Liu, W.; Wu, Q. Biological Functions and Detection Strategies of Magnesium Ions: From Basic Necessity to Precise Analysis. Analyst 2025, 150, 2979–2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracci, B.; Torricelli, P.; Panzavolta, S.; Boanini, E.; Giardino, R.; Bigi, A. Effect of Mg2+, Sr2+, and Mn2+ on the Chemico-Physical and in Vitro Biological Properties of Calcium Phosphate Biomimetic Coatings. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2009, 103, 1666–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, E.D.H.; Pandya, Y.; Mun, E.A.; Rogers, S.E.; Abutbul-Ionita, I.; Danino, D.; Williams, A.C.; Khutoryanskiy, V.V. Structure and Characterisation of Hydroxyethylcellulose–Silica Nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 6471–6478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motelica, L.; Ficai, D.; Petrisor, G.; Oprea, O.-C.; Trușcǎ, R.-D.; Ficai, A.; Andronescu, E.; Hudita, A.; Holban, A.M. Antimicrobial Hydroxyethyl-Cellulose-Based Composite Films with Zinc Oxide and Mesoporous Silica Loaded with Cinnamon Essential Oil. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Jiang, C.; Wu, L.; Bai, X.; Zhai, S. Cytotoxicity-Related Bioeffects Induced by Nanoparticles: The Role of Surface Chemistry. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molenda, M.; Kolmas, J. The Role of Zinc in Bone Tissue Health and Regeneration—A Review. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2023, 201, 5640–5651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciosek, Ż.; Kot, K.; Rotter, I. Iron, Zinc, Copper, Cadmium, Mercury, and Bone Tissue. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlad, R.-A.; Pintea, A.; Pintea, C.; Rédai, E.-M.; Antonoaea, P.; Bîrsan, M.; Ciurba, A. Hydroxypropyl Methylcellulose—A Key Excipient in Pharmaceutical Drug Delivery Systems. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rishikesan, S.; Basha, M.A.M. Synthesis, Characterization and Evaluation of Antimicrobial, Antioxidant & Anticancer Activities of Copper Doped Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles. Acta Chim. Slov. 2020, 67, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Zhang, A. Copper-Instigated Modulatory Cell Mortality Mechanisms and Progress in Oncological Treatment Investigations. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1236063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekki-Porębski, S.A.; Rakowski, M.; Grzelak, A. Free Zinc Ions, as a Major Factor of ZnONP Toxicity, Disrupts Free Radical Homeostasis in CCRF-CEM Cells. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Gen. Subj. 2023, 1867, 130447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalef, L.; Lydia, R.; Filicia, K.; Moussa, B. Cell Viability and Cytotoxicity Assays: Biochemical Elements and Cellular Compartments. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2024, 42, e4007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, B.; Yang, H.; Han, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Qu, X.; Zhuang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Dai, K. In Vitro and in Vivo Studies of Zn-Mn Biodegradable Metals Designed for Orthopedic Applications. Acta Biomater. 2020, 108, 358–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taskozhina, G.; Batyrova, G.; Umarova, G.; Issanguzhina, Z.; Kereyeva, N. The Manganese–Bone Connection: Investigating the Role of Manganese in Bone Health. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, D.; Wu, Z.; Fujita, H.; Lindsey, J. Design, Synthesis, and Utility of Defined Molecular Scaffolds. Organics 2021, 2, 161–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivănescu, M.C.; Munteanu, C.; Cimpoeșu, R.; Istrate, B.; Lupu, F.C.; Benchea, M.; Șindilar, E.V.; Vlasa, A.; Stamatin, O.; Zegan, G. The Influence of Ca on Mechanical Properties of the Mg–Ca–Zn–RE–Zr Alloy for Orthopedic Applications. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, S.; Wu, Y.; Ma, J. Strongly Enhanced Persulfate Activation by Bicarbonate Accelerated Cu(iii)/Cu(i) Redox Cycles. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2024, 10, 1785–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Duan, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Li, B. Efficient Diclofenac Removal by Superoxide Radical and Singlet Oxygen Generated in Surface Mn(II)/(III)/(IV) Cycle Dominated Peroxymonosulfate Activation System: Mechanism and Product Toxicity. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 433, 133742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| NaOH Volume, mL | pH |

|---|---|

| 0 | 1.81 |

| 10 | 2.21 |

| 20 | 3.29 |

| 30 | 4.56 |

| 40 | 5.72 |

| 50 | 6.8 |

| 60 | 7.96 |

| 70 | 9.15 |

| 80 | 10.38 |

| 90 | 11.58 |

| 100 | 11.98 |

| NPs | Specific Gravity, g/cm3 | Porosity, % | Swelling, % | Volume-Mass Index, cm3/g | Thickness, mm | Density, g/cm3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MgCO3 | 0.058 ± 0.003 | 93.3 ± 2.4 | 1083.0 ± 18 | 16.3 ± 0.49 | 7.7 ± 0.23 | 0.119 ± 0.006 |

| CaCO3 | 0.056 ± 0.003 | 98.0 ± 2.5 | 1089.0 ± 19 | 17.0 ± 0.51 | 1.43 ± 0.04 | 0.073 ± 0.003 |

| ZnCO3 | 0.050 ± 0.0025 | 95.6 ± 2.4 | 1402.0 ± 24 | 19.9 ± 0.6 | 1.67 ± 0.05 | 0.079 ± 0.004 |

| MnCO3 | 0.067 ± 0.0033 | 93.9 ± 2.4 | 858.0 ± 15 | 15.3 ± 0.46 | 1.66 ± 0.05 | 0.092 ± 0.005 |

| CuCO3 | 0.060 ± 0.003 | 95.8 ± 2.4 | 1192.0 ± 20 | 16.2 ± 0.49 | 2.38 ± 0.07 | 0.085 ± 0.004 |

| control | 0.066 ± 0.0033 | 95.3 ± 2.4 | 1359.0 ± 23 | 17.7 ± 0.53 | 2.5 ± 0.08 | 0.087 ± 0.004 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Blinov, A.; Rekhman, Z.; Sizonenko, M.; Askerova, A.; Golik, D.; Serov, A.M.; Bocharov, N.; Rusev, N.; Kuznetsov, E.; Ryazantsev, I.; et al. Biopolymer-Based Nanocomposite Scaffolds: Methyl Cellulose and Hydroxyethyl Cellulose Matrix Enhanced with Osteotropic Metal Carbonate Nanoparticles (Ca, Zn, Mg, Cu, Mn) for Potential Bone Regeneration. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 655. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120655

Blinov A, Rekhman Z, Sizonenko M, Askerova A, Golik D, Serov AM, Bocharov N, Rusev N, Kuznetsov E, Ryazantsev I, et al. Biopolymer-Based Nanocomposite Scaffolds: Methyl Cellulose and Hydroxyethyl Cellulose Matrix Enhanced with Osteotropic Metal Carbonate Nanoparticles (Ca, Zn, Mg, Cu, Mn) for Potential Bone Regeneration. Journal of Composites Science. 2025; 9(12):655. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120655

Chicago/Turabian StyleBlinov, Andrey, Zafar Rekhman, Marina Sizonenko, Alina Askerova, Dmitry Golik, Alexander M. Serov, Nikita Bocharov, Nikita Rusev, Egor Kuznetsov, Ivan Ryazantsev, and et al. 2025. "Biopolymer-Based Nanocomposite Scaffolds: Methyl Cellulose and Hydroxyethyl Cellulose Matrix Enhanced with Osteotropic Metal Carbonate Nanoparticles (Ca, Zn, Mg, Cu, Mn) for Potential Bone Regeneration" Journal of Composites Science 9, no. 12: 655. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120655

APA StyleBlinov, A., Rekhman, Z., Sizonenko, M., Askerova, A., Golik, D., Serov, A. M., Bocharov, N., Rusev, N., Kuznetsov, E., Ryazantsev, I., & Nagdalian, A. (2025). Biopolymer-Based Nanocomposite Scaffolds: Methyl Cellulose and Hydroxyethyl Cellulose Matrix Enhanced with Osteotropic Metal Carbonate Nanoparticles (Ca, Zn, Mg, Cu, Mn) for Potential Bone Regeneration. Journal of Composites Science, 9(12), 655. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120655