Abstract

Fluorinated polyurethanes (FPUs) and their composites are promising new barrier materials with a broad range of applications. In particular, they are widely used as effective hydrophobic coatings that perform well under prolonged environmental exposure. Despite their extensive use, the behavior of FPU coatings under specific climatic conditions remains insufficiently studied. In this paper, dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) is employed to evaluate the structural, mechanical, and relaxation evidence of climatic aging for paint-and-varnish coatings, which protect the surfaces of metallic alloys and polymer composites. Special knowledge of structural and physical–mechanical properties—such as a glass transition temperature (Tg), elastic moduli (E′ and E″) in both glassy and elastic states, degree of crosslinking, and other features relevant to coatings designated for climatic impact prevention—can be reliably obtained by the DMA technique. Along with previously published data, the currently obtained results for FPU have been analyzed for a long time (three years) of exposure in a wide range of climatic regions in Russia.

1. Introduction

The development of novel constructional materials in various branches of industrial engineering is aimed not only at improving their mechanical and barrier properties but also at enhancing resistance to climatic impact and environmental aging [1,2]. However, even stable plastics and their composites require additional surface protection against aggressive exterior factors such as temperature fluctuations, humidity, solar radiation, chemically active aerosols, and other harsh factors encountered under diverse operating climatic conditions [3,4,5].

Currently, to protect the blends and composites, polymer coatings and paint-and-varnish technologies are successfully used to enhance the service life of the constructional polymer materials [6,7]. For this purpose, a wide range of organic coatings with different chemical structures has been synthesized mainly based on epoxy- [8,9,10,11], acrylic- [12,13], urethane- [14,15], and silicon-containing [16] compounds. Among these, fluorinated polyurethanes [17,18,19] have proven to be the most effective barrier layers for mitigating adverse climatic impacts.

The constructional and functional materials covered by paintwork and other modifiers have been extensively studied to evaluate the effects of aggressive factors under mimicked laboratory conditions [13,20,21,22] and during natural climatic exposure [10,12,14,23,24]. To assess the coating state at various stages of weathering, several indirect indicators were used. Most commonly, the changes in gloss and color difference are monitored [10,12,14]. Functional and structural transformations in the coated layers were regularly studied using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, confocal Raman spectroscopy, scanning electron microscopy combined with energy-dispersive X-ray analysis, atomic force microscopy, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, and other methods [19,24,25,26,27,28,29]. With these techniques, the effects of photo-oxidation, thermo-oxidative degradation, hydrolysis, and post-curing were revealed at the molecular and submicron levels.

Among these informative methods, a special place belongs to the dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) method, which can reveal details of such characteristic phenomena occurring in polymers as moisture plasticizing, the shift in glass transition temperature (Tg), crystallinity evolution, spatial network arrangement, and the various features of aging [30,31]. The advantages of DMA, in relation to the paints and polymer coatings, have been discussed in a number of comprehensive reviews [32,33] and in a series of extensive publications [34,35,36,37,38,39]. It has been particularly shown that for a polymer-coated solid surface, within the framework of the basic concepts of “freely damped torsional vibrations” [30] or “forced resonant bending vibrations” [31], the post-curing degree control of the coating is possible by the glass transition temperature (Tg) measurements conducted by the DMA method. By using this approach, the thermo-mechanical behavior of a high-elastic polymer layer applied to substrates could be disclosed with greater success [32]. Similarly, the effect of UV irradiation on the intensity of polyester surface degradation, manifested as a decrease in the mechanical dynamic modulus (E′) and the symbatic decrease in Tg, was reliably shown in the work [33].

DMA is sensitive to both the bulk and surface structure of polymers. This method is responsive to structural alterations in coatings or to adhesive interactions between reinforcing fibers and polymer matrices, for example, under testing with carbon fiber adhesives [34]. After 3 months of hydrothermal aging, the Tg values of the adhesive films increased by 16.8 °C, demonstrating post-curing development in a thin surface layer. A similar post-curing effect was observed in an alkyd-silicone coating applied to a steel substrate [35]. Valuable information obtained from the DMA method for assessing the properties of paint-and-varnish coatings on the basis of acrylic enamel AC-1115 was presented [36]. As a result of the ratio variation for the thin film components, such as the acrylic styrene copolymer C-38 and the low-modulus epoxy diene oligomer E-40 deposited and cured on aluminum foil, internal stresses arose. This phenomenon worsened the elasticity of the composite coating. To eliminate this drawback, the plasticizers DAF-789 and PAS-22 were added to the coating composition, which remarkably reduced both the elastic modulus and Tg of the tested film and enhanced its relative elongation under tensile and periodic loads.

The DMA method is particularly advantageous in analyzing protective polymer coatings applied to metal structures. For example, a comprehensive study by Perrin et al. focused on the weathering aging of alkyd coating modified with silicones applied to thin steel plates [37]. The protective layer, consisting of the epoxy resin and a plasticized copolymer of vinyl chloride and vinyl acetate, was placed between the steel plate and the silicone slab. Over the course of 4 years, the steel–polymer sandwich was kept in conditions of three climatic zones and was simultaneously tested for 6 months under the conditions corresponding to ISO 9227 [40] and ASTM D5894 [41] standards. Applying the DMA method, it revealed a notable increase in Tg of silicone from 68 to 83 °C, which was accompanied by an increase in microhardness from 40 to 250 MPa. The last effect was explained by the partial release of the plasticizer and a decrease in the content of carbonyl groups, as determined by FTIR spectroscopy. After the microtome removal of the upper layer of coating, a further increase in Tg from 120 to 160 °C was observed and was associated with a decrease in the content of C=O groups. In the acrylic coating with an intermediate polyurethane layer covering a steel plate, after 2016 h of UV irradiation, a change in pigment color and surface disintegration due to photo-oxidation were observed [38]. However, the Tg retained its initial value of 77 °C.

Obviously, during climatic exposure, polymeric coatings are irradiated by sunlight. In this context, Croll [39] investigated the effect of UV irradiation on a polyurethane coating applied to brass and aluminum foils. According to the DMA data, after 6000 h of exposure, and due to the post-curing effect, Tg of the superficial film increased from 75 to 120 °C. In the framework of freely damped torsion vibration mode [30] or forced resonant bending vibration mode [31], it is possible to control the degree of post-curing of coatings by the glass transition temperature (Tg), determined from the temperature position of the maxima of the dynamic moduli losses in shear G″ or bending E″, and the value of the dynamic shear modulus G′ or bending E′ in the highly elastic state of the polymer base of the paint coatings [32]. The destruction characteristics of polyester coating under the influence of UV irradiation are reflected by a decrease in Tg and E′ under the condition: T > Tg [32].

The crosslinking density ν in a paint-and-varnish coating film can be accurately determined using Equation (1):

where E′ is a dynamic modulus of elasticity, measured in a highly elastic state by the DMA method at T > Tg, R is the universal gas constant, and T is the absolute temperature [37,42,43].

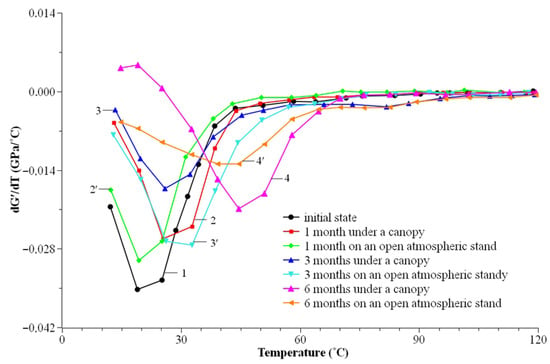

For the protected layers, the increase in crosslinking density leads to the growth of the Tg [42,44]. The DMA method can accurately determine the contribution of thin polymer layers to the viscoelastic behavior of dissimilarly layered materials. This capability was demonstrated for three composites, such as the aluminum alloy plates glued with the epoxy film [43] and the carbon fibers with a thermoregulating coating [45], and wooden plates protected with epoxy ester coating cured with a set of hardeners [46,47]. Figure 1 illustrates an example of Tg measurements for a paint-and-varnish coating based on ED-20 resin and AF-2 hardener applied to wood for 1–6 months of exposure under open and closed conditions in a moderately warm climate [46,47]. The minimum in the temperature derivative of the dynamic shear modulus dG′/dT, measured using an inverse torsion pendulum [47], shifts from 42.3 to 58.0 °C after 6 months of climatic exposure, demonstrating post-curing of the epoxy coating.

Figure 1.

Temperature dependences of dG′/dT of the paint-and-varnish coating based on ED-20 resin and AF-2 hardener applied to wood, in the initial state (1) and after exposure for 1 month (2, 2′), 3 months (3, 3′), and 6 months (4, 4′) under a canopy (2, 3, 4) and on an open atmospheric stand (2′, 3′, 4′) [47].

Thus, the DMA method is a convenient, sensitive tool for investigating the surface composite properties under both natural and laboratory conditions, as a function of time, temperature, and dynamic mechanical impact [34,45,46,47]. Because measurements can be performed without destroying the sample, DMA provides valuable information on polymer molecular mobility. Moreover, this approach enables experts to obtain unique insights into molecular mobility in coatings in glassy, highly elastic states, and the glassy–rubber transition fields [32,33,45]. Over the past few decades, several comprehensive publications have reported on the dynamic mechanical behavior of petrol-based [48,49] and biobased fibrillar [50,51] composites. However, the number of DMA surveys focused solely on the surface state of planar and fibrillar composites remains relatively small.

At the end of the last century, a series of presentations reported the outstanding role of DMA as a versatile technique for controlling the mechanical behavior of polymeric surface layers under aggressive weathering conditions [52,53], a line of research promoted by Monsanto Chemical Co, Springfield, USA. Along with that, the pioneering work of Hill et al. focused specifically on the application of DMA to study the performance of automotive coating exploitation under weathering impact in California (USA) [54]. Notably, this publication emphasizes the use of a solo DMA technique, demonstrating its reliability in assessing the mechanical and relaxation features of polymer automobile surfaces under harsh environmental conditions. The authors were among the first to recognize the method’s universality and its ability to provide multiple criteria of structure evolution simultaneously. The last outcome leads to the conclusion that, despite certain limitations of DMA, for example, its limited ability to obtain direct information on the nanoscopic changes in the polymer barrier, DMA applications can enhance the investigator’s efforts under frequent monitoring due to the possibility of obtaining several characteristics at the same time, which reduces not only the labor intensity of the study but also its costs. The idea of self-sufficiency of this dynamic method has been confirmed by several subsequent studies, which employed DMA as a valuable tool without a significant combination of other relaxation methods [55,56].

Previous studies have convincingly shown that incorporating fluorinated groups into polyurethanes (PUs) enhances the coating’s stability against adverse climatic conditions [57,58]. The inclusion of fluorinated segments in the PU macromolecule significantly increases its hydrophobicity [59], resulting in a substantial reduction in the surface energy of modified PU coatings. These high barrier characteristics against water, salts, and other aggressive atmospheric agents can even prevent icing of aircraft, ships, and other vehicles [60], thereby broadening the scope of applications under weathering conditions. Furthermore, as advanced materials, the fluorinated polyurethanes (FPUs) exhibit such promising characteristics as thermal stability, inflammability, and biocompatibility.

In modern practice, a relatively simplified instrumental approach based on DMA is widely used to assess the effects of weathering impact on both mechanical behavior and structural characteristics. This method involves comparing property indices after holding elementary samples under laboratory temperature and humidity conditions [61]. This approach assumes that the accelerated weathering test in the climatic chamber can serve as an analog of the full-scale outdoor test. However, direct comparisons have shown that even the most advanced artificial climate chambers cannot fully produce the diversity of real climatic effects (daily and seasonal fluctuations in temperature, relative humidity, overheating of samples under the sunlight, destruction of the surface layers due to UV radiation, wind, precipitation, etc.). For instance, in the work by Salnikov et al. [62], it was experimentally observed that during natural exposure of dark-colored polymer plates, their surface temperature under the influence of solar radiation overheats to 30 °C, leading to a 30% decrease in the relative humidity near the surface. Such real-life modes of climatic tests are extremely difficult to reproduce in laboratory settings. Therefore, accelerated test protocols require strict justification regarding the combination of simulating factors, their intensity, and exposure duration, making outdoor climatic tests preferable whenever possible. Nonetheless, accelerated laboratory methods remain useful for a comparative evaluation of the materials with different compositions or produced via different technologies. At the same time, accelerated methods cannot completely replace full-scale climatic tests.

The motivation for this research lies in exploring the potential of the conventional technique of DMA as a promising tool for the multi-parametrical evaluation of climatic impacts on modern high-performance coatings based on FPU. Numerous and long-term experimental efforts to reliably monitor the evolution of the structural and relaxation characteristics in fluorinated barrier materials can be significantly enhanced through the appropriate implementations of DMA as a comprehensive method.

Given the above review, the aim of this work is to investigate the long-term climatic impact on the promising coatings composed of a fluoropolyurethane and epoxy primer adduct applied to the glass fibers reinforcing the constructional plastics, following aging in different climatic zones. The novelty of this study lies in experimental confirmation and expanding capabilities of the DMA for determining molecular characteristics (Tg), and dynamic mechanical features (E′, E″) for paint-and-varnish coatings. This approach allows experts to identify relaxation processes and glassy–rubber transitions in thick surface layers, offering valuable insights for aging exploration under outdoor weathering testing.

2. Materials and Methods

In the paper by Veligodsky et al. [24], the properties of fiberglass plastic of the VPS-48/7781-grade based on the VSE-1212 binder [63] were examined after 3 years of exposure in 7 climatic regions of Russia. The characteristics of these climatic zones are given in Table 1. The maximum decrease in compressive strength σc of this material during climatic aging reached 40%. If this fiberglass plastic was protected by a VE-69 coating, the reduction did not exceed 17%. Noting the effectiveness of the coating in protecting this fiberglass plastic from aging, a difference in the temperature position of the E″ maxima related to the VE-69 coating was shown; however, no quantitative estimates of this effect were provided [24].

Table 1.

Average annual climate characteristics of the testing regions (climatic zones).

For this research, both initial and aged samples of the fiberglass plastic (grade of VPS-48/7781) were prepared based on the VSE-1212 binder [63]. An epoxy primer EP-0215 with a thickness of 20 μm was applied to the surface of the plates of this fiberglass plastic, and two layers of fluoropolyurethane coating of VE-69 with a total thickness of 45 ± 5 μm were applied on top of it [16].

The polymer matrix of VSE-1212 is based on a multifunctional modified epoxy resin. The molten binder is modified with a polyisocyanate. The polyisocyanate modifier consists of several isomers: 2,4- and 4,4-methylenediphenyldiisocyanate, triisocyanate, and polyisocyanate. 4,4-diaminodiphenyl sulfone was used as the aromatic amine hardener to obtain a strong crosslinking of the polymer material [63].

The VE-69 fluoropolyurethane paint is a two-component system consisting of a polymer resin and a hardener mixed before use. A schematic reaction of the production of fluoropolyurethane resin is given in the previous work [16]. The EP-0215 primer is a two-component epoxy system consisting of a suspension of chromate pigments and fillers in an epoxy resin solution, a hardener of amine type that is mixed immediately before application.

Specimens of the fiberglass plastic with the paint-and-varnish coating were studied by DMA according to the method described in [24]. The measurements were performed using the forced bending vibration method (DMA 242D setup, Netzsch, Selb, Germany). Three-point bending of 50 × 6 × 2.2 mm samples was performed at an oscillation frequency of 1 Hz with an oscillation amplitude of 30 μm and a dynamic force of 1.3 N. The temperature in the measuring chamber increased at a rate of 2 °C/min from room temperature to 230 °C. To reduce possible chemical transformations in the coating during heating, the measuring chamber was filled with argon.

During the measurements, and in accordance with ASTM D4065 [64], the dynamic storage modulus (E′) and dynamic loss modulus (E″) were determined using the following Equation (2):

where N is the axial force, L is the length of the free part of the sample, b is the sample width, h is the sample thickness, A is the amplitude of oscillations, a is the displacement relative to the parallel axis, and δ is the phase shift between stress and strain.

According to Merkulova et al. [17], both the VE-69 coating and the EP-0215 primer are moisture sensitive and can absorb up to 1.5–2 wt.% of water. Therefore, after exposure, fiberglass plastic samples were cut into pieces of 50 × 10 × 2 mm and divided into 2 batches for DMA measurements: without any conditioning, with moisture content after climatic exposure; after drying at 60 °C to a constant weight. The amount of desorbed moisture was controlled by weighing with an analytical balance with an accuracy of 0.1 mg. To increase the reliability of the results, 5 parallel samples of each set were measured after testing in each climatic region.

Color changes in the coatings were evaluated in accordance with GOST R 52490 [65] which specifies the use of the equal-contrast color system CIE L*a*b* for this purpose. During the climatic tests, changes in lightness (∆L*), color purity (∆C*), color tone/hue (∆H*), and total color difference (∆E*) were quantified. The changes in color parameters were evaluated in comparison with the corresponding samples in the initial state. Measurements were performed using an X-Rite SP-64 spectrophotometer (Grand Rapids, MI, USA). It was taken into account that physical–chemical transformations in the coatings promote an increase in ∆E*, depending on both the duration and the climatic characteristics of exposure.

3. Results and Discussion

During prolonged climatic exposure in five climatic regions, the outward appearance and decorative properties of the VE-69 barrier layers were sufficiently deteriorated [66]. This was manifested by a reduction in gloss and an increase in color distance. The higher the average temperature and relative humidity in the exposure area, the more noticeable the color indicators of the initial samples changed. The positive protective role of the VE-69 specimens is confirmed by their ability to slow the degradation of fiberglass when exposed to open climatic conditions. Under open climatic conditions, a decrease in the strength of the VPS-48/77 fiberglass plastic, also observed in [24], was a consequence of the binder’s destruction.

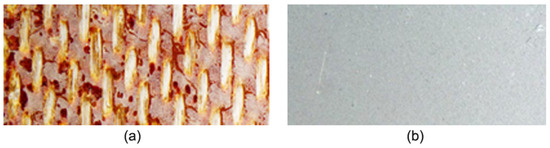

During 3 years of exposure of the fiberglass plastic to open climatic conditions without a protective coating, the polymer matrix in the surface layer was destroyed, resulting in the denudation of the glass fibers (Figure 2a). Fluoropolyurethane enamel completely protected the fiberglass surface from aging (Figure 2b), while its color remains highly stable, and there were no micro-damages and defects on the surface of the samples exposed in all climatic zones.

Figure 2.

The appearance of the fiberglass plastic surface without a protective coating (a) and protected by fluoropolyurethane enamel (b) after 3 years of exposure in the seaside temperate climate of Sochi (magnification 12×).

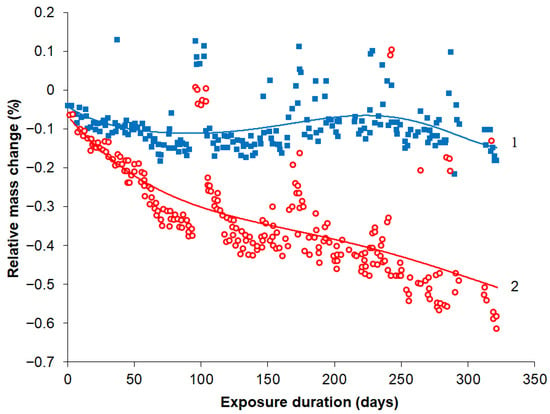

It is well-known that a good indicator of polymer destruction is their weight loss [67]. Figure 3 presents the dependence of mass change (w) of VPS-48/7781 fiberglass plastic plates, both unprotected and coated with the VE-69, during their third year of exposure in Gelendzhik. The observed mass fluctuations, with an average amplitude of 0.25%, were associated with precipitation, dew formation, and overheating due to solar irradiation, the patterns of which were discussed by Ridzuan et al. [49]. As a result of the destruction of the VSE-1212 binder, the mass of the fiberglass plastic samples decreased by 0.55 ± 0.05% per year of exposure (lower curve in Figure 3). If fiberglass plastic was protected by the VE-69 coating, its mass loss over the specified period was only 0.1 ± 0.5% (upper curve in Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Dependence of the relative mass change in fiberglass plastic plates on the duration of exposure at an open-air stand in the moderately warm climate of Gelendzhik: VPS-48/7781 with paint-and-varnish coating VE-69 (curve 1); VPS-48/7781 without a protective coating (curve 2); solid lines—approximation by a 6th degree polynomial.

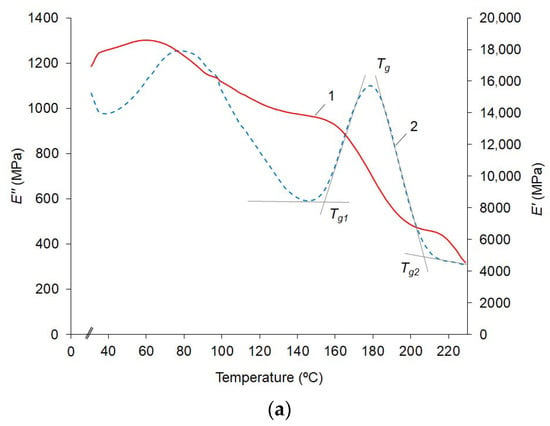

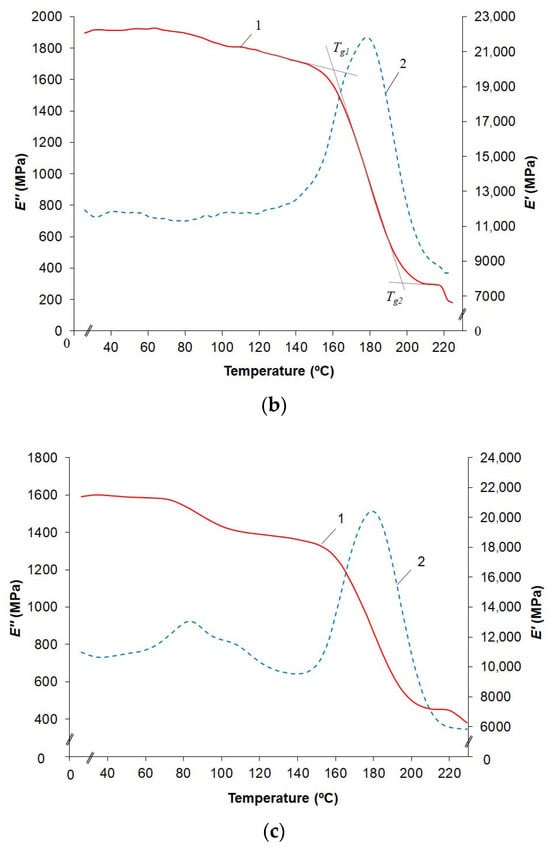

To demonstrate the effectiveness of the DMA method for assessing the transition of a paint-and-varnish coating from a glassy to a highly elastic state (the α-transition), the temperature dependences of E′(T) and E″(T) of the VPS-48/7781 with the VE-69 coating in the initial state were measured (Figure 4a). To eliminate any possible plasticizing effect of moisture, the samples were dried at 60 °C to constant weight. Figure 4a demonstrates two low- and high-temperature peaks in the range of 50 °C to 130 °C and from 150 °C to 210 °C, respectively.

Figure 4.

Temperature dependences of E′ (curve 1) and E″ (curve 2) of the dried samples of fiberglass plastic of VPS-48/7781 in the initial state: (a) with the coating of VE-69 and the primer of EP-0215; (b) from the surface of which the VE-69 coating and EP-0215 primer were removed; (c) from the surface of which the VE-69 coating was removed, but the EP-0215 primer layer was retained.

To identify these relaxation-temperature regions, parallel similar measurements were carried out for the dried samples, after removal of the surface layers of the VE-69 coating and the epoxy primer of EP-0215. Figure 4b shows that the type of temperature dependences E′(T) and E″(T) changed similarly to the results of the work of Veligodsky et al. [24]. In this case, at a high temperature (178 °C), the relaxation region manifests itself more clearly with a sharp decrease in the dynamic storage modulus (E′) and a maximum value of the dynamic loss modulus (E″) caused by the transition from a glassy state to a highly elastic one of the VPS-48/7781 fiberglass plastic matrix. Consequently, the low-temperature relaxation region (Figure 4a) with a wide maximum E″(T) arises due to enhancing the molecular mobility of the paint-and-varnish coating.

Using the recommendations of ISO 6721 [68] and their implementation, Melnikov et al. [69] determined the characteristic temperatures of the identified relaxation regions. From the dependence E′(T) presented in Figure 4a, the lower (Tg1) and the upper (Tg2) boundaries of the α transition were determined as the intersection points of the baselines and lines extrapolating the linear change in the dynamic modulus of elasticity at the beginning and end of the transition of the epoxy matrix from a glassy state to a highly elastic one [69]. Similarly, the same temperature transitions were based on the dependence E″ (T) in Figure 4b. In addition to Tg1 and Tg2, the glass transition temperature Tg was defined as the temperature corresponding to the maximum value of the dynamic loss modulus. Ideally, these characteristic temperatures obtained from the two methods should coincide; however, small differences arise due to experimental errors and extrapolation.

The high sensitivity of the DMA response to the coating modification of fiberglass plastic makes it possible to detect the contribution of the epoxy primer to both the temperature position and the shape of the low-temperature relaxation maximum. For this experiment, the VE-69 coating layer was removed from the fiberglass plastic surface by careful grinding, while the EP-0215 primer layer was retained. DMA measurements were then performed, and the results are presented in Figure 4c.

Even with a primer layer thickness of 20 µm, the low-temperature relaxation region of the VPS-48/7781/EP-0215 system also had a region of a sharp decrease in E′ from 70 ± 10 °C to 130 ± 10 °C, as well as a double maximum in E″ at the temperatures of 85 ± 10 °C and 110 ± 10 °C.

Analyzing the results of the above Figure 4a–c, it is reasonable to conclude that the broad, asymmetrical low-temperature peak E″ observed in Figure 4c reflects the superposition of three relaxation maxima located at 76 ± 2 °C, 85 ± 5 °C, and 110 ± 10 °C. The locations of these maxima on the temperature scale were determined using a graphical differentiation method commonly applied in spectrometry, an example of which is described in the work by Bensley et al. [70].

The first maximum is a consequence of the transition from the glassy state to the highly elastic one of fluoropolyurethane of VE-69 (α1-transition). The second and third maxima of E″ are caused by a similar transition from the glassy state to the highly elastic one of the multicomponent epoxy primers (α2-transition and α3-transition) due to the possible microphase separation in the layers of epoxy resin of EP-0215 [17].

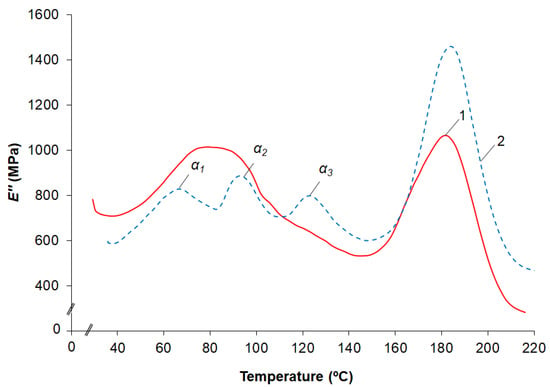

After 3 years of exposure of the fiberglass plastic of VPS-48/7781, protected by the paint-and-varnish coating, the position and shape of low-temperature relaxation maxima changed significantly. In contrast to the initial state, after exposure in all seven climatic regions, the α1, α2, and α3 transitions took the form of three clearly separated E″ peaks. For comparison, Figure 5 shows the dependences of E″(T) of the dried samples of fiberglass plastics of VPS-48/7781 with the VE-69 coating and the EP-0215 primer in the initial state and after 3 years of exposure in the warm and humid climate of the city of Sochi.

Figure 5.

Temperature dependences of E″ of dried samples of fiberglass plastic of VPS-48/7781 with the VE-69 coating and the EP-0215 primer in the initial state (curve 1), after 3 years of exposure in the warm and humid climate of Sochi (curve 2). Temperature transitions are designated as α1–α3.

Table 2 cumulates the values of the transition temperatures of the α1, α2, and α3 relaxation transitions in the initial state and after 3 years of exposure in seven climatic regions obtained from DMA measurements.

Table 2.

Influence of climatic test conditions on the temperatures of transitions of α1, α2, and α3 after 3 years of exposure.

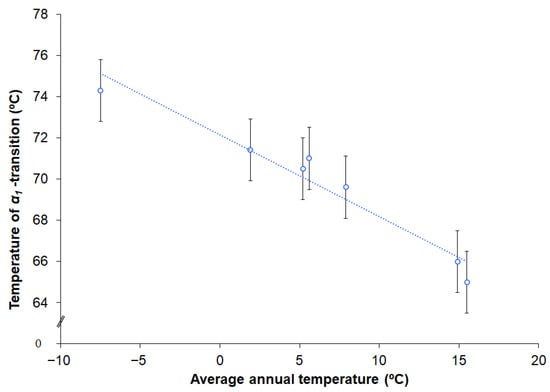

As a result of climatic exposure, the temperature of the α1-transition decreased from 1.7 °C after exposure in Yakutsk to 11.0 °C after exposure in Gelendzhik. Figure 6 shows that the temperature of the α1-transition, which is the glass transition temperature of fluoropolyurethane in VE-69, after 3 years of exposure, decreased in proportion to the average annual air temperature of the region. The total solar radiation dose during exposure also influenced the change in the temperature of the α1-transition, but monotonic proportionality was not observed.

Figure 6.

Influence of the average annual air temperature of the climate test regions after 3 years of exposure of fiberglass plastic of VPS 48/7781 with the VE-69 coating and the EP-0215 primer on the temperature of α1-transition.

The probable reasons for the decrease in the α1-transition temperature are photo-oxidative reactions in the VE-69 coating, confirmed by changes in its gloss values G (ISO 2813 [71]) and color distance ΔE (GOST R 52490 [65]). According to Andreeva et al. [66], after 3 years of exposure in various climatic zones, the VE-69 coating showed high resistance; however, with an increase in the average air temperature from 7.9 °C in Moscow to 25 °C in Florida, the gloss loss of the coating increased from 7 to 38%.

In the work of Startsev [72], the value of the color distance ΔE in the CIE L*a*b* system for the gray-colored covering of VE-69 increased depending on the duration of full-scale exposure according to Equation (3):

where ΔEmax is the maximum change in color distance, cont. units; t is the duration of exposure, days; τ is the parameter characterizing the exposure time of 0.63 × ΔEmax, days.

With an increase in the average air temperature from 7.9 °C in a temperate climate to 20.4 °C in a dry subtropical climate, the maximum change in the color distance increased from 0.38 to 2.36 con. units.

The above-mentioned loss of gloss and increase in the color distance of the VE-69 coating are clear indicators of destructive processes. For example, Liu et al. [14] conducted the experiment of aging of the polyurethane coating on the coast of the South China Sea. After 2 years of exposure, it revealed an increase in the color distance from 1.5 to 6.5 con. units, which corresponded to a decrease in the glass transition temperature of PU by 34 °C, caused by the breaking of chemical bonds.

The temperatures of α2- and α3-transitions after full-scale exposure increased by 13–15 °C and acquired stable values of α2 = 99 ± 1 °C and α3 = 122.5 ± 0.5 °C, regardless of the climatic conditions of the tests. Analogous to the results of the previous studies [36,46], it can be argued that as a result of the combined effects of temperature, moisture, and solar irradiation, the post-curing of the polymer base of the EP-0215 epoxy primer occurred. The factors responsible for the decrease in the glass transition temperature of fluoropolyurethane of VE-69 will be determined after additional studies using the FTIR method.

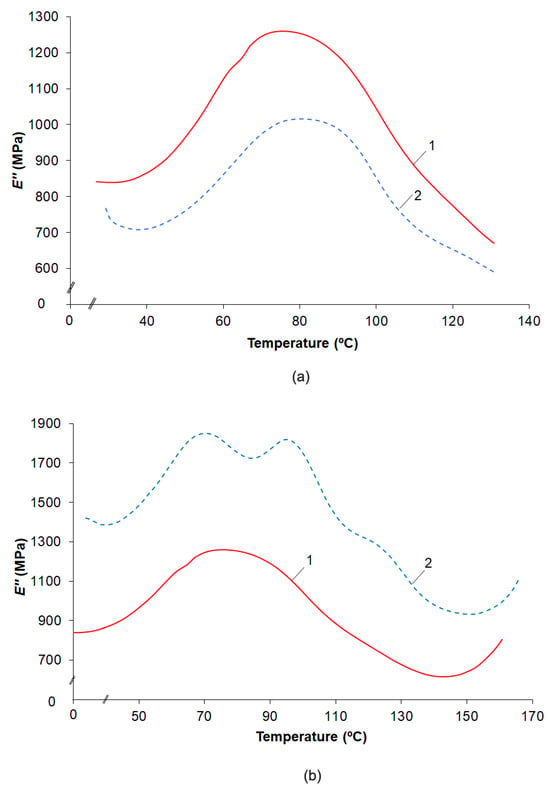

According to the work of Merkulova et al. [17], the VE-69 coating and the EP-0215 primer can absorb 1.8–2.0% of moisture. The DMA method allows one to evaluate the plasticizing effect of moisture on these materials. Figure 7a shows that in the initial fiberglass samples containing 0.3% H2O (determined by weighing after drying at 60 °C), the temperature of the low-temperature relaxation maximum was reduced by 10 ± 5 °C compared to the dried samples. This shift reflects the difference between the initial state of the moisture plasticizing effect [24,69] and the effect after climatic exposure (Figure 7b).

Figure 7.

Temperature dependences of E″ fiberglass plastic of VPS-48/7781 with the VE-69 coating and the EP-0215 primer in the initial state (a) and after 3 years of exposure in Vladivostok (b) without pre-conditioning (curve 1) and after drying at 60 °C to a constant weight (curve 2).

The examples shown in Figure 5 and Figure 7, as well as in Table 2, demonstrate the fundamental ability to detect the α1, α2, and α3 relaxation maxima when studying the properties of paint-and-varnish coatings and primers without removing them from the surface of polymer composite materials. To apply this capability in the practical study of polymer coating aging, alongside other reliable methods, several methodological issues must be addressed.

First, when using the DMA method, it is necessary to take into account that the position of maxima of α1, α2, and α3 on the temperature scale during different stages of climatic aging depend not only on irreversible chemical reactions such as destruction or post-hardening but also on the plasticizing effect of moisture. Therefore, in each specific case, the conditions under which moisture ceases to affect the measurement results must be determined. Our research showed that complete removal of moisture from fiberglass plastic of VPS-48/7781 requires drying at 60 °C for 60 days.

Secondly, to reliably interpret the α1, α2, and α3 maxima and model the kinetics of their changes on the temperature scale, comparative climatic tests of fiberglass plastics, carbon fiber plastics, and other polymer composite materials are necessary. These tests should include both without protection and with protection options (only a primer, only a polymer coating, a combination of coating and primer). We are currently conducting such studies, the results of which will be presented in a separate manuscript.

Thirdly, modern paint-and-varnish coatings must protect the surface of machinery elements without replacement for 20, 30, or more years. Therefore, the possibility of studying the aging of coatings using dynamic mechanical analysis at deep stages of aging is required. An example of such a study is presented in the paper [73] devoted to the 8- and 13-year aging test of the fluoroepoxide and acrylic styrene coatings on the surface of carbon fiber-reinforced plastic.

Fourth, for the precise determination of the relaxation maxima of α1, α2, and α3, it is advisable to perform dynamic mechanical measurements of polymer composite materials with paint-and-varnish coatings at different frequencies according to the recommendations given in [69,74,75]. With this approach, it is possible to find the values of the activation energy of relaxation maxima and use it for analysis by the Williams–Landel–Ferry and Arrhenius methods.

In this paper, the authors focused on the dynamic mechanical analysis of the VE-69 coating after 3 years of aging in seven climatic zones. It should be noted, however, that this coating effectively protects the fiberglass plastic of VPS-48/7781 from climatic aging. This was also revealed by dynamic mechanical analysis.

Table 3 shows the values of the glass transition temperature (Tg) of the VSE-1212 polymer matrix of the fiberglass plastic of VPS-48/7781, determined from the position of the maximum of the dynamic loss modulus (E″), as illustrated in Figure 4b.

Table 3.

Influence of climatic test conditions on the glass transition temperatures of the polymer matrix of VSE-1212 after 3 years of exposure.

After 3 years of exposure of fiberglass plastic of VPS-48/7781 without a protective coating, its glass transition temperature Tg decreased from 178 ± 2 °C to 150 ± 2 °C (by 28 ± 2 °C). Our research has shown that the main reason for this effect is the plasticizing effect of moisture. During 3 years of exposure, 0.65 ± 0.5% of water accumulated in fiberglass plastic plates [24]. After moisture removal by drying at 60 °C, Tg increased by 8 ± 5 °C compared to the value of this indicator in the initial state. According to [75], under the influence of temperature, humidity, and solar radiation, chemical degradation reactions that reduce Tg and post-curing reactions that increase Tg occur in the epoxy matrices of the fiberglass plastics. Excluding the reversible plasticizing effect of moisture, an increase in Tg by 8 ± 5 °C for dried samples can be considered the result of the predominance of the effect of post-curing over the effect of destruction.

After 3 years of exposure of fiberglass plastic of VPS-48/7781 protected with the VE-69 coating and the EP-0215 primer, the glass transition temperature (Tg) of the epoxy matrix decreased from 178 ± 2 °C to 171 ± 5 °C (by 7 ± 5 °C), depending on the exposure location. It can be concluded that the VE-69 coating and the EP-0215 primer significantly weakened the plasticizing effect of moisture on the polymer matrix of VSE-1212. Following moisture removal by drying at 60 °C, Tg was 191 ± 3 °C (increased by 13 ± 3 °C compared to the value of this indicator in the initial state). Consequently, the VE-69 coating and the EP-0215 primer system prevented the degradation of the VSE-1212 polymer matrix and, after 3 years of exposure, contributed to an additional increase in Tg from 8 ± 5 °C to 13 ± 3 °C.

This example demonstrates that comparative dynamic mechanical analysis of polymer composite materials, both unprotected and protected by paint-and-varnish coatings, provides valuable insights into the mechanisms of climatic aging for both composite materials and their protective systems. A critical condition for obtaining reliable results is the proper consideration of the plasticizing effect of moisture accumulated in materials during their climatic exposure.

According to the results of the conducted research, for the first time, the high sensitivity and potential of the dynamic mechanical analysis method for investigating the climatic aging of paint-and-varnish coatings designed to protect polymer composite materials has been demonstrated. It was established that temperature transitions corresponding to the transformation of a fluoropolyurethane coating and an epoxy primer from a glassy state to a highly elastic one is significantly influenced by moisture in the material. To reliably assess the effects of degradation and post-curing processes in paint-and-varnish coatings and primers caused by climatic factors, it is necessary to carry out DMA measurements of the composite–primer–enamel system after complete moisture removal from the samples.

It has been shown that the glass transition temperature of the primer coating in the enamel–primer system reaches stable values and remains unchanged regardless of the geographical exposure zone after a three-year period of full-scale testing in seven different climatic regions. This conclusion is based on a systematic analysis of the data obtained during multiple measurements.

4. Conclusions

In various technology sectors, composite coatings offer a potential opportunity to enhance their resistance to climate-related and adverse effects during indoor and outdoor exposure. The unique information on molecular and mechanical characteristics such as the glass transition temperature (Tg), elastic moduli (E′ and E″) in glassy and elastic states, the degree of crosslinking and other features of paint-and-varnish coatings can be reliably obtained by the DMA technique.

Along with the majority of previous publications focused on the bulk of the constructional composites [76,77,78] under dynamic behavior exploration, our findings disclose the long-term impact of temperature, humidity, and UV irradiation on molecular mobility via Tg and viscoelastic behavior in surface-protected layers. Special challenges emerging as a result of humidity plasticizing and composite aging were investigated by the DMA as well. The fundamental assessment of surface evolution during climatic exposition has clearly shown the water plasticizing and post-curing effect.

The proposed DMA method is extremely promising for identifying the key features of climatic aging as a multifaceted process that, in combination with additional methods of analysis, significantly expands the capabilities of other physical methods such as ATR FTIR, dielectric spectroscopy, SEM, etc., widely used in current data to examine the perspective paint-and-varnish coatings in depth.

In various engineering sectors, the FPU composite coatings offer a realistic opportunity to resist the adverse climate-related effects during their outdoor exploitations. The unique information on structure, relaxation, and mechanical characteristics such as the glass transition temperature (Tg), the elastic moduli (E′ and E″) in glassy and elastic states, the degree of crosslinking and other features of surface protective barriers was reliably obtained by the DMA technique.

Along with the majority of previous publications focused on the bulk properties of the constructional composites by DMA under dynamic behavior exploration [76,77,78], our findings disclose a long-term climatic impact on FPU molecular mobility via the Tg shift and the viscoelastic behavior in the surface protective layers. Special challenges emerging as a result of humidity plasticizing and composite aging were investigated by the DMA. The thorough assessment of surface evolution during climatic impact has shown clearly pronounced post-curing effects. The proposed DMA method is extremely promising for identifying climatic polymer aging as a multifaceted process. In the nearest prospect, the DMA technique combination with structure–morphological methods, such as ATR-FTIR, SEM, NMR, etc., may significantly enhance the development and implementation of contemporary coatings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.V.S. and A.L.I.; methodology, T.V.K.; software, E.E.M.; validation, A.L.I., E.E.M. and O.V.S.; formal analysis, E.E.M.; investigation, T.V.K., E.V.D. and I.M.V.; resources, A.L.I.; data curation, A.L.I.; writing—original draft preparation, O.V.S., T.V.K., A.A.V. and E.V.D.; writing—review and editing, O.V.S., A.A.V. and A.L.I.; visualization, E.E.M. and E.V.D.; supervision, O.V.S. and A.L.I.; project administration, O.V.S.; funding acquisition, O.V.S. and A.L.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

O.V.S., T.V.K., I.M.V. and E.V.D. are grateful to the Russian Science Foundation (project No. 24-19-00009).

Data Availability Statement

Raw data is available on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the native speaker Vasilisa Shunikhina for her assistance with the edition of the submission’s final version. O.V.S., T.V.K., I.M.V. and E.V.D. are grateful to the Russian Science Foundation (project No. 24-19-00009).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mayandi, K.; Rajini, N.; Ayrilmis, N.; Indira Devi, M.P.; Siegchin, S.; Mohammad, F.; Al-Lohedan, H.A. An overview of endurance and ageing performance under various environmental conditions of hybrid polymer composites. Review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 15962–159888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.-W.; Cho, H.-J.; Gong, Y.-D. Analytical approach to degradation structural changes of epoxy-dicyandiamide powder coating by accelerated weathering. Review. Prog. Org. Coat. 2023, 175, 107357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kablov, E.N.; Bakradze, M.M.; Gromov, V.I.; Voznesenskaya, N.M.; Yakusheva, N.A. New high-strength structural and corrosion-resistant steels for aerospace technology developed by FSUE “VIAM” (review). Aviatsionnyye Mater. Tekhnologii 2020, 1, 3–11. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kablov, E.N.; Antipov, V.V.; Oglodkova, Y.S.; Oglodkov, M.S. Experience and prospects for the use of aluminum-lithium alloys in aviation and space technology products. Metallurg 2021, 1, 62–70. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Startsev, V.O.; Antipov, V.V.; Slavin, A.V.; Gorbovets, M.A. Modern domestic polymer composite materials for aircraft construction (review). Aviatsionnyye Mater. Tekhnologii 2023, 2, 122–144. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Ramezanpour, J.; Ramezanzadeh, B.; Samani, N.A. Progress in bio-based anti-corrosion coatings; A concise overview of the advancements, constraints, and advantages. Prog. Org. Coat. 2024, 94, 108556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, T.; He, Y.; Wang, Y.; Bi, Y. Corrosion and aging of organic aviation coatings: A review. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2023, 36, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Startsev, V.O.; Khrulev, K.A.; Evdokimov, A.A. The influence of seasonality of climatic influence on changes in the color characteristics of EP-140 epoxy enamel. Korroz. Mater. Zashchita 2017, 6, 31–36. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.R.; Zhang, H.-J.; Jun, Z.; Zhang, M.; Eldin, S.M.; Siddique, I. Electrochemical corrosion protection of neat and zinc phosphate modified epoxy coating: A comparative physical aging study on Al alloy 6101. Front. Chem. 2023, 11, 1142050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Startsev, V.O.; Frolov, A.S. Influence of climatic influence on the color characteristics of paint and varnish coatings. Lakokrasochnyye Mater. Ikh Primen. 2015, 3, 16–18. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Verma, A.; Tiwary, C.S.; Bhattacharya, J. Enhancement of hydrophobic, resistive barrier and anticorrosion performance of epoxy coating with addition of Clay-Modified Green Silico-Graphitic Carbon. Carbon Trends 2024, 15, 100347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.V.; Le, X.H.; Dao, P.H.; Decker, C.; Nguyen-Tri, P. Stability of acrylic polyurethane coatings under accelerated aging tests and natural outdoor exposure: The critical role of the used photo-stabilizers. Prog. Org. Coat. 2018, 124, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Li, C.; Lv, Z.; Wang, R.; Wu, D.; Li, X. Correlation between the surface aging of acrylic polyurethane coatings and environmental factors. Prog. Org. Coat. 2019, 132, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, L.; Hou, J.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, P.; Wang, B.; Jin, N. Degradation behavior and mechanism of polyurethane coating for aerospace application under atmospheric conditions in South China Sea. Prog. Org Coat. 2019, 136, 105310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, B.; Zeng, X.; Li, Z.; Wen, Y.; Hu, Q.; Yang, Q.; Zhou, M.; Yang, B. Study on the influence of accelerated aging on the properties of an RTV anti-pollution flashover coating. Polymers 2023, 15, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nefedov, N.I.; Semenova, L.V.; Kuznetsova, V.A.; Vereninova, N.P. Paint and varnish coatings for protecting metal and polymer composite materials from aging, corrosion and biodamage. Aviatsionnyye Mater. Tekhnologii 2017, S 29, 393–404. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkulova, Y.I.; Kuznetsova, V.A.; Novikova, T.A. Study of the properties of a paint coating system based on fluoropolyurethane enamel and primer with a reduced content of toxic pigments. Proc. VIAM 2019, 5, 68–75. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, D.; Dong, Z. Degradation of fluorinated polyurethane coating under UVA and salt spray. Part II: Molecular structures and depth profile. Prog. Org. Coat. 2018, 124, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Yu, L.; Lu, Z.; Kang, H.; Li, L.; Zhao, S.; Shi, N.; You, S. Synthesis, Structure, Properties, and Applications of Fluorinated Polyurethane. Polymers 2024, 16, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, M.E. Paint weathering tests. In Handbook of Environmental Degradation of Materials; Kutz, M., Ed.; William Andrew Publishing: Norwish, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 597–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, M.; Boisseau, J.; Pattison, L.; Campbell, D.; Quill, J.; Zhang, J.; Smith, D.; Henderson, K.; Seebergh, J.; Berry, D.; et al. An improved accelerated weathering protocol to anticipate Florida exposure behavior of coatings. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 2013, 10, 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlov, A.V.; Andreeva, N.P.; Pavlov, M.R.; Merkulova, Y.I. Climatic tests of paint and varnish coating based on fluoroplastic and features of its destruction. Proc. VIAM 2019, 5, 103–110. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnev, V.P. The influence of the humid subtropical environment on the color characteristics of protective polymer coatings. Environ. Control. Syst. 2020, 3, 56–64. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veligodsky, I.M.; Koval, T.V.; Kurnosov, A.O.; Marakhovsky, P.S. Study of the climatic resistance of fiberglass samples after full-scale exposure in various climatic zones. Proc. VIAM 2022, 11, 134–148. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Manoli, Z.; Pecko, D.; Van Assche, G.; Stiens, J.; Pourkazemi, A.; Terryn, H. Transport of Electrolyte in Organic Coatings on Metal. Paint and Coatings Industry. In Paint and Coatings Industry; Yilmaz, F., Ed.; Intechopen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.P.; Vang, C.; Tallman, D.E.; Bierwagen, G.P.; Croll, S.G.; Rohlik, S. Weathering degradation of a polyurethane coating. Polym. Degrad. Stabil. 2001, 74, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.P.; Li, J.; Croll, S.G.; Tallman, D.E.; Bierwagen, G.P. Degradation of low gloss polyurethane aircraft coatings under UV and prohesion alternating exposures. Polym. Degrad. Stabil. 2003, 80, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Guo, H.; Feng, Y. Study on UV-aging performance of fluorinated polymer coating and application on painted muds. Mater. Res. Express 2021, 8, 015301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, M.T.; Cano, E.; Ramirez-Barat, B. Testing protective coatings for metal conservation: The influence of the application method. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillham, J. Torsional braid analysis (TBA) of polymers. In Developments in Polymer Characterizations; Dworkins, J., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1982; Volume 3, pp. 159–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menard, R.P.; Menard, N. Dynamic Mechanical Analysis. A Practical Introduction, 3rd ed.; CRC Press LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2020; p. 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrovanec, D.J.; Schoff, C.K. Thermal mechanical analysis of organic coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 1988, 16, 135–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.W.; McIntyre, R. Analysis of test methods for UV durability predictions of polymer coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 1996, 27, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, A.P.C.; Fulco, A.P.P.; Guerra, E.S.S.; Arakaki, F.K.; Tosatto, M.; Costa, M.C.B.; Melo, J.D.D. Accelerated aging effects on carbon fiber/epoxy composites. Compos. Part B 2017, 110, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolomeo, P.; Irigoyen, M.; Aragon, E.; Frizzi, M.A.; Perrin, F.X. Dynamic mechanical analysis and Vickers micro hardness correlation for polymer coating UV ageing characterisation. Polym. Degrad. Stabil. 2001, 72, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Startsev, O.V.; Bolonin, A.B.; Vapirov, Y.M.; Krivov, V.A.; Vladimirsky, V.N.; Ofitserova, M.G. Improving the viscoelastic properties of acrylic enamel AC-1115. Paint. Varn. Their Appl. 1986, 4, 16–18. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Perrin, F.X.; Merlatti, C.; Aragon, E.; Margaillan, A. Degradation study of polymer coating: Improvement in coating weatherability testing and coating failure prediction. Prog. Org. Coat. 2009, 64, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotnarowska, D. Influence of ageing with UV radiation on physicochemical properties of acrylic-polyurethane coatings. J. Surf. Eng. Mater. Adv. Technol. 2018, 8, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croll, S.G. Quantitative evaluation of photodegradation in coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 1987, 15, 223–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 9227:2022; Corrosion Tests in Artificial Atmospheres—Salt Spray Tests. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- ASTM D5894-21; Standard Practice for Cyclic Salt Fog/UV Exposure of Painted Metal, (Alternating Exposures in a Fog/Dry Cabinet and a UV/Condensation Cabinet). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- Osterhold, M.; Glöckner, P. Influence of weathering on physical properties of clear coats. Prog. Org. Coat. 2001, 41, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Startseva, L.T.; Jelesina, G.F.; Startsev, O.V.; Mashinskaya, G.P.; Perov, B.V. Effect of corrosive medium on properties of metal-plastics laminates. Int. J. Polymeric Mater. 1997, 37, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaja, A.; Fernando, D.; Croll, S. Mechanical property changes and degradation during accelerated weathering of polyester-urethane coatings. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 2006, 3, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deev, I.S.; Nikishin, E.F.; Kurshev, E.V.; Lonsky, S.L. Research of structure and composition of KMU-4l carbon fiber reinforced plastic after 12 years of exposure to space environment. 1. Macrostructure and surface composition. Quest. Mater. Sci. 2015, 2, 65–75. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Cataldi, A.; Corcione, C.E.; Frigione, M.; Pegoretti, A. Photocurable resin/nanocellulose composite coatings for wood protection. Prog. Org. Coat. 2017, 106, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Startsev, O.V.; Molokov, M.V.; Smirnov, V.F.; Gudozhnikov, S.S. Mechanisms of climatic aging of wood. In Climatic Testing of Building Materials; Izdatel’stvo ASV: Moscow, Russia, 2017; pp. 322–366. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Haris, N.I.N.H.; Hassan, M.Z.; Ilyas, R.A.; Suhat, M.A.; Sapuan, S.M.; Dolah, R.; Mohammad, R.; Asyraf, M.R.M. Dynamic mechanical properties of natural fiber reinforced hybrid polymercomposites: A review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 19, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridzuan, M.J.M.; Majid, M.S.A.; Afendi, M.; Mazlee, M.N.; Gibson, A.G. Thermal behaviour and dynamic mechanical analysis of Pennisetum purpureum/glass-reinforced epoxy hybrid composites. Compos. Struct. 2016, 152, 850–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manral, A.; Ahmad, F.; Chaudhary, V. Static and dynamic mechanical properties of PLA bio-composite with hybrid reinforcement of flax and jute. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 25, 577–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safri, S.N.A.; Sultan, M.T.H.; Jawaid, M.; Abdul Majid, M.S. Analysis of dynamic mechanical, low-velocity impact and compression after impact behaviour of benzoyl treated sugar palm/glass/epoxy composites. Compos. Struct. 2019, 226, 111308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, P.; Prud’homme, R.E. Miscibility behaviour of PVC/polymeth acrylate blends: Temperature and composition analysis. Polymer 1991, 32, 1468–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, L.W.; Grande, J.S.; Kozlowski, K. Dynamic mechanical analysis of weathered (Q-U-V) acrylic clearcoats with and without stabilizers. Polymeric Materials Science and Engineering. ACS Polym. Mater. Sci. Eng. Conf. Pap. 1990, 63, 654. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, L.W.; Korzeniowski, H.M.; Ojunga-Andrew, M.; Wilson, R.C. Accelerated clearcoat weathering studied by dynamic mechanical analysis. Prog. Org. Coat. 1994, 24, 147–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamasco, D.; Bulian, F.; Melchior, A.; Menotti, D.; Tirelli, P.; Tolazzi, M. DMA analysis to predict the performance of waterborne coatings. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2011, 103, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, D.M.; Escarsega, J.A. Dynamic mechanical analysis of novel polyurethane coating for military applications. Thermochim. Acta 2000, 357–358, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Wang, Q.; Chen, P.; Xu, Y.; Nie, W.; Zhou, Y. Controllable hydrolytic stability of novel fluorinated polyurethane films by incorporating fluorinated side chains. Prog. Org. Coat. 2022, 165, 106729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshan, S.; Jafari, R.; Momen, G. Multifunctional polyurethane-based coating with corrosion resistance and anti-icing performance for AA2024-T3 alloy protection. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 698, 134581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, M.; Yang, C.; Yang, Z.; Liu, X. Insights into the stability of fluorinated super-hydrophobic coating in different corrosive solutions. Prog. Org. Coat. 2021, 151, 106043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Mei, J.; Liu, M.; Zhang, C. Preparation of mechanically robust, self-healing superhydrophobic coatings based on novel fluorinated polyurethane via a “two-step” polycondensation process for applications in self-cleaning and anti-icing. Prog. Org. Coat. 2025, 207, 109385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C.; White, K.M.; Pickett, J.E. (Eds.) Service Life Prediction of Polymers and Plastics Exposed to Outdoor Weathering; A Volume in Plastics Design Library; William Andrew Publishing: Norwish, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–342. [Google Scholar]

- Salnikov, V.G. Seasonal moisture absorption of aeronautical carbon fiber reinforced plastic in conditions of warm humid climate. Monit. Syst. Environ. 2021, 2, 46–53. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaev, E.V.; Barbotko, S.L.; Andreeva, N.P.; Pavlov, M.R. Comprehensive study of the impact of climatic and operational factors on a new generation of epoxy binder and polymer composite materials based on it. Part 1. Investigation of the effect of sorbed moisture on the epoxy matrix and carbon fiber based on it. Tr. VIAM 2016, 6, 86–99. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D4065-2020; Standard Practice for Plastics: Dynamic Mechanical Properties: Determination and Report of Procedures. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- GOST R 52490-2005 (ISO 7724-3:1984); Paint Materials. Colorimetry. Part 3. Calculation of Colour Differences. Standardinform: Moscow, Russia, 2006. (In Russian)

- Andreeva, N.P.; Skirta, A.A.; Nikolaev, E.V. Study of the preservation of the properties of paint and varnish coatings for aviation purposes under the influence of climatic factors in atmospheric conditions. In Multifunctional Paint and Varnish Coatings. Materials of the All-Russian Scientific and Technical Conference, Moscow, Russia; FGUP «VIAM»: Moscow, Russia, 2018; pp. 29–38. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Kablov, E.N.; Startsev, V.O.; Inozemtsev, A.A. Moisture saturation of structural-like elements made of polymer composite materials in open climatic conditions with the imposition of thermal cycles. Aviat. Mater. Technol. 2017, 2, 56–68. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 6721:2019; Plastics—Determination of Dynamic Mechanical Properties. Part 1: General Principles. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Melnikov, D.A.; Gromova, A.A.; Gorodilova, N.A.; Zagora, A.G. Determination of heat resistance of epoxy matrixes by DMA method. Tr. VIAM 2023, 7, 114–121. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Bensley, K.A.; Chimenti, R.V.; Lofland, S.E. Low-Frequency Raman Spectroscopy of Polymers. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2025, 226, 70004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 2813:14; Paints and varnishes—Determination of Gloss Value at 20°, 60° and 85°. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- Startsev, V.O. Climate aging of paint coating systems. Part 2. Influence of different climatic zones. Tr. VIAM 2025, 6, 7. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Startsev, O.V.; Koval, T.V.; Krotov, A.S.; Dvirnaya, E.V.; Velegodsky, I.M. Investigation of the properties of carbon fiber reinforced plastic with coatings after 8 and 13 years of exposure in a moderately warm climate. Part 2. The condition of protective paint coatings. Proc. VIAM 2024, 11, 9. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Kohutiar, M.; Studeny, Z.; Krbaťa, M.; Jus, M.; Mikuš, P.; Kovaříková, I. Frequency Dependence of Glass Transition Temperature of Thermoplastics in DMA Analysis. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 25, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramita, V.D.; Panyoyai, N.; Kasapis, S. The Mechanical Glass Transition Temperature Affords a Fundamental Quality Control in Condensed Gels for Innovative Application in Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals. Foods 2025, 14, 2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krauklis, E. Predicting Environmental Ageing of Composites: Modular Approach and Multiscale Modelling. Mater. Proc. 2021, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanoth, R.; Jayanarayanan, K.; Kumar, P.S.; Balachandran, M.; Pegoretti, A. Static and dynamic mechanical properties of hybrid polymer composites: A comprehensive review of experimental, micromechanical and simulation approaches. Review. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2023, 174, 107741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, N.; Dua, S.; Singh, V.K.; Singh, S.K.; Senthilkumar, T. A comprehensive review on fillers and mechanical properties of 3D printed polymer composites. Mater. Today 2024, 40, 109617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).