Abstract

Shape memory polymer composites (SMPCs) are promising materials in aerospace thanks to their light weight and ability to provide an actuation load during shape recovery, the magnitude of which depends on the laminates design. In this work, SMPCs were manufactured by alternating carbon fiber prepregs with a SM interlayer of epoxy resin. The number of composite plies ranged from 2 to 8 and two interlayer thicknesses were selected (100 μm and 200 μm in the lamination stage). Compression molding was performed for consolidation, and the interlayer’s thickness was reduced by edge bleeding. A thermo-mechanical cycle was applied for memorization. The shape fixity and the shape recovery of the vast majority of the SMPCs were above 90%, with the 200 μm/six-ply laminate recording the highest combination of values (94.8% and 95.7%, respectively). A significant effect due to the presence of a thicker interlayer was not evident, underlying the need to determine specific manufacturing procedures. Starting from these results, a lab-scale procedure was implemented to manufacture a smart device by embedding a microheater in the 200 μm/two-ply architecture. The device was memorized into a L-shape (90° bending angle), and a voltage of 24 V allowed it to recover 86.2° in 90 s, with a maximum angular velocity of 1.55 deg/s.

1. Introduction

Shape memory polymers (SMPs) belong to the class of stimuli-responsive materials. Their main property is to change shape when an external stimulus is applied; they remain in the deform state until the trigger is re-applied, restoring the initial condition. SM behavior can be activated by means of different energy sources such as heat [1], light [2], electricity [3] and magnetism [4]. However, thermally driven SMPs are the most common [5]. Both thermosetting (TS) and thermoplastic (TP) resins have SM properties including epoxy resin, polyurethane, polyimide and polylactic acid (PLA) [6]; by mixing nanomaterials with high electrical conductivity such as carbon nanotubes into the polymeric matrix, the thermal conductivity can be improved [7]. The incorporation of functional materials allows for the enhancement of SM properties such as the recoverable strain and the recovery load [8]. The integration of these functional materials into composite structures (SMPCs) has extended their use to high-valued applications, such as aerospace components [9], biomedical devices [10], SM arrays [11], soft robotics [12] and 4D printing [13]. The SM behavior is also exhibited by metal alloys (SMAs) such as nickel-titanium. However, components are difficult to manufacture using traditional processes like machining, but promising results have been obtained by using selective laser melting [14].

In aerospace, SMPs and SMPCs are used to reduce either the payload or the occupied volume, allowing structure re-design; solar arrays, deployable structures, booms and hinges are the most investigated applications [5,15]. In this context, SMPCs are generally reinforced with carbon fibers (CFs). Their presence maximizes mechanical properties and permit to take advantage of the high technological level that has been reached in manufacturing reinforced plastics (CFRPs). In recent years, several studies have underlined the suitability of CFs-SMPCs for manufacturing morphing structures [16], solar sails [17], booms for solar arrays [18] and reflectors [19]. This is because SMPCs are able to provide an actuation load during shape recovery, which favors their use in deploying systems. However, a certain amount of time is required to restore the initial configuration, and SMPCs cannot return to the deformed shape without undergoing a new memory cycle; consequently, the SM behavior of this class of smart materials is known as a one-way soft actuation. The actuation force of SMPCs laminates typically ranges from 30 N to 12 N, with a recovery time of 150 s, which is suitable for deployment operations in space [20]. In particular, self-deployable structures can be launched in the packed configuration and deployed once in orbit. However, their manufacturing can be difficult, but the use of innovative manufacturing technologies can help to overcome some limits; for example, 4D printing permit to optimize material utilization and to achieve good performances in terms of bending strength and modulus (806 MPa and 47.2 GPa, respectively) as well as a high shape fixity ratio (Rf) of 98% and a shape recovery ratio (Rr) of 99% [21]. The use of unidirectional CFs has been explored by varying fiber mass fractions; it was shown that a content of 37 wt% in SM epoxy resin allowed for an improvement of the recovery stress from 16 to 47 MPa [22]. Moreover, a high-reversible macroscale strain of 9.6% has been obtained by unidirectional CFs-SMPCs, which enabled the high-reversible deformation to be used for foldable structures in space [23]. Furthermore, fabrics can be used, but fiber weaving can have a significant effect on both mechanical and SM behavior; it has been shown that woven reinforcements can improve mechanical properties and has permitted to achieve an Rr above 98% and an Rf above 90% [24]. A 3D anisotropic thermomechanical model for woven fabric-reinforced SMPCs based on Helmholtz free energy decomposition has been designed [25]. Also, hand lamination was used to deposit a SM interlayer on the prepreg plies surface, and compression molding was conducted for consolidation; a two-ply laminate with a 100 μm interlayer obtained a Rf of 75% and a Rr of 97% [26]. Even though deploying systems in space are supposed to work only once, they undergo a severe qualification process. In this phase, the components’ ability to retain their thermo-mechanical properties after many memory cycles is typically under investigation. Therefore, SMPCs durability has gained a fundamental role when designing these structures. It was shown that after 10 memory cycles, SM properties remain almost unaltered during cycling, with the memory load having a dispersion between 2% and 6% [27].

SMPCs [28] with SM interlayers have already been tested in a space environment, showing promising results in terms of actuation load and shape recovery. The foam and the interlayer were made using the same uncured epoxy powder that has also been used in this study. The aim of the present work is to design SMPCs architectures that can potentially be used to manufacture active structures in deploying systems. Consequently, SMPCs have been manufactured by changing either the number of composite plies (from one to eight) or the thickness of the interlayer (100 μm and 200 μm). Memory tests were performed, and the properties of the laminates have been extracted and correlated. In the end, a smart device was prototyped by integrating a local heat source into the laminate structure, and memory-recovery tests were conducted.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Supplied Materials

An aeronautical epoxy CF prepreg with a 0/90 plane weave (Cycom 132 977-2 by Solvay, Brussels, Belgium) was used to manufacture the SMPCs. SM properties were added by depositing interlayers of uncured epoxy resin, which was supplied in the form of a fine blue-green powder (3M Scotchkote 206N, Maplewood, MN, USA) with a nominal density of 1.44 g/cm3.

2.2. SMPCs Architecture and Manufacturing

The experimentation was performed on 14 architectures obtained by varying the number of composite plies, from two to eight, as well as the SM interlayer thickness (100 μm and 200 μm). For each architecture, two samples were produced.

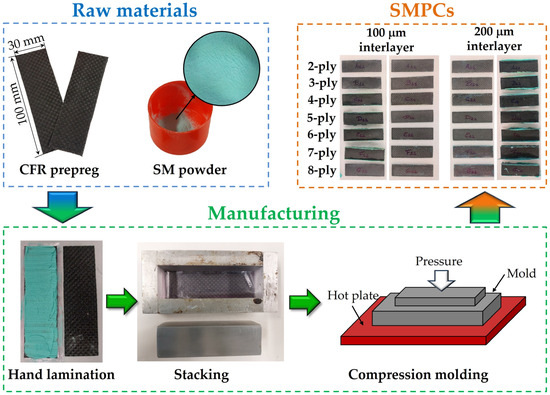

The entire manufacturing process is shown in Figure 1. CF prepreg plies have been extracted from the supplied roller with nominal dimensions 30 × 100 mm2. Nominal interlayer thicknesses of 100 μm and 200 μm were manufactured by using a mass of the uncured epoxy resin of 0.43 g and 0.86 g, respectively. The powder was manually deposited on the prepreg surface, avoiding gaps and ensuring uniform distribution. Hand lamination was performed to obtain the stacking sequence of the proposed architectures. The uncured SMPCs were positioned in an aluminum mold with a rectangular cavity of 30 × 100 mm2 for consolidation. A polyethylene film was placed between the mold and the laminate to promote releasing. Curing was carried out via compression molding on a hot plate at 200 °C and 70 kPa for 1 h. After cooling, the SMPCs were extracted from the mold and tested.

Figure 1.

Manufacturing of SMPCs using hand lamination and compression molding.

2.3. Testing

2.3.1. Laminates Characterization

After molding, the physical and mechanical properties of the composites were evaluated. The SMPCs’ mechanical performances were obtained with three-point bending using a universal material testing machine (MTS Insight 5, Eden Prairie, MN, USA). Each specimen was deformed by 1.5 mm in such a way that both the stiffness and the elastic modulus could be extracted. Tests were conducted at 1 mm/min, with a load span of 80 mm.

2.3.2. Temperature Calibration for Memory Tests

To activate the SM behavior of the manufactured composites, heat was required. The temperature increment was triggered by a hot gun that permitted to exceed the epoxy glass transition temperature (Tg) of 120 °C [17,27]. To ensure that a sufficient temperature was reached, a temperature calibration test was conducted to assess the positioning of the hot gun tip with respect to the SMPCs specimen.

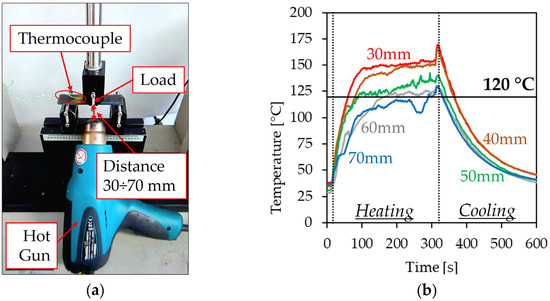

A type K thermocouple was placed on the upper face of the composite, as the air flow hit the specimen on its lower part. The test was conducted in the same conditions as the subsequent memory test, in such a way that all heat dissipating elements were present; the experimental apparatus is shown in Figure 2a. The distance between the hot gun tip and the SMPCs surface was changed in each test, and temperature changes were recorded through the thermocouple. The experiment was conducted at the distance of 30 mm, while the following tests were carried out by increasing this gap by 10 mm each time, until a distance of 70 mm was reached. The SMPCs were heated for the first 300 s and then left to cool for additional 300 s. The total duration of each experimental test was 600 s. The temperature calibration was carried out on the thickest sample (eight plies and 200 µm of SMP interlayer), which required the longest heating time due to its larger thickness.

Figure 2.

Temperature calibration: (a) experimental setup; (b) temperature curves.

2.3.3. Shape Memory Thermo-Mechanical Cycle

The evaluation of SM behavior was performed by applying a thermo-mechanical cycle to the manufactured laminates. The memory cycle was conducted by deforming the heated laminate in a three-point bending configuration with a span length of 80 mm and a test speed of 1 mm/min, with the same material testing machine. Since 14 architectures were designed, each one had a different thickness; to take this aspect into account, the memory tests were performed at the constant strain (ε) of 1%. The memory cycle was made up of three steps that started with the hot sample deformation until the selected ε was reached; the specimens were pre-heated for 300 s before loading. Subsequently, the deformation was applied; then, the hot gun was turned off and cooling was carried out for an additional 300 s without removing the constraint. At the end, the sample was unloaded and remained in the deformed shape. Furthermore, the recovery load was measured; the constrained laminate was re-heated for 300 s with the hot gun (whose tip was at the same distance as in the memory tests), followed by cooling for 300 s. Finally, free recovery was carried out by heating the deformed SMPCs with the hot gun.

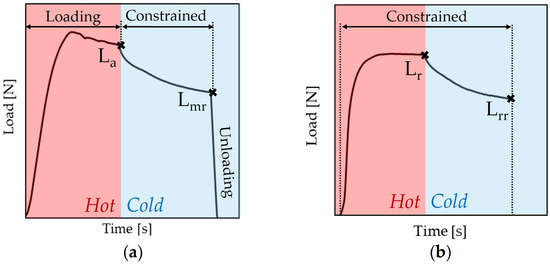

Exemplificative curves (SMPCs eight-ply, 100 μm interlayer) of the processes described above have been reported in Figure 3. Figure 3a shows the memory curve and highlights the reference loads: the applied load (La) and the memory residual load (Lmr). On the other hand, Figure 3b refers to the measurement of the recovery load (Lr) and the residual recovery load (Lrr). Data normalization was performed after testing and the corresponding stresses were extracted: applied memory stress (σa), residual memory stress (σmr), recovery stress (σr) and residual recovery stress (σrr). Furthermore, Rf and Rr were measured using the following equations:

with εu, εm, and εr representing the residual strain in the specimen at the end of the memory cycle, the recovered strain after the free recovery test and the deformation at the maximum imposed displacement, respectively.

Figure 3.

Exemplificative curves of the shape memory test: (a) memory cycle; (b) recovery load.

2.4. Manufacturing and Testing of the SMPCs Device

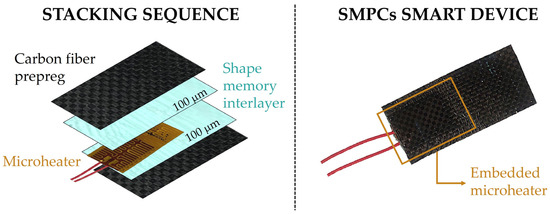

The two-ply SMPCs with 200 μm was selected to prototype a smart device which integrates a 25 × 50 mm2 microheater (Khlva 102/10 by Omega, Norwalk, CT, USA) to trigger the SM properties. The heater is a flexible rectangular device, consisting of an Inconel etched circuit, 0.001″ (25.4 μm) thick, encapsulated between two layers of polyimide film each 0.002″ (50.8 μm) thick; it has a maximum working voltage of 28 V and a watt density of 10 W/in2. By considering the microheater size, the maximum power and the maximum current are 20 W and 0.71 A, respectively. The multilayer structure was obtained by stacking composite plies of nominal size 50 × 80 mm2 and interleaving 200 μm of SM epoxy interlayer. In particular, a 100 μm interlayer was deposited on the bottom ply, the microheater was positioned on top, and then an additional 100 μm were placed; finally, the second ply was located on top. A releasing film of fluorinated ethylene propylene (FEP) was put between the composite plies and the aluminum mold to favor demolding.

Manufacturing was carried out by compression molding in a hot parallel plate press at 220 °C and 5 bar for 15 min. The extraction from the mold was performed when the composite had cooled down to room temperature, and then trimming was carried out. The device’s final size was 35 × 80 mm2. Figure 4 shows the stacking sequence as well as the smart device.

Figure 4.

SMPC with embedded microheater.

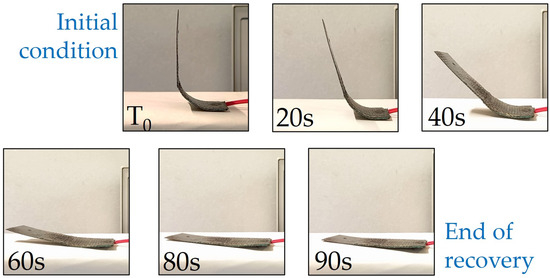

The prototype thickness was measured, and it was memorized with a bending angle of 90°, using an aluminum cylindrical mold with a diameter of 17 mm. Shape recovery was investigated by connecting the embedded microheater to a power supply at 24 V, and an infrared camera (883 by Testo) was used to ensure that the achieved temperature was sufficient to activate the SM behavior. Both the recovery angle and the angular velocity were evaluated, with the recovery test lasting for 90 s.

3. Results

The mean values of the physical and mechanical properties of the manufactured SMPCs are reported in Table 1. The thickness of the laminates increased with the number of composite plies and with the interlayer dimension; an exception was found with two- and three-ply SMPCs, whose thickness was slightly lower when manufactured with the 200 μm interlayer compared to the 100 μm interlayer. In general, densities were lower for laminates with 200 μm interlayers, because of the greater presence of neat epoxy resin within the laminate architecture; however, all SMPCs showed very close densities, with the smallest being 1.35 g/cm3 (four- and five-ply composites with 200 μm interlayers) and the largest being 1.41 g/cm3 (two-, five- and seven-ply laminates with 100 μm interlayers). Stiffness inceased with the number of composite plies, and its growth did not look to be correlated with the interlayer thickness, since the obtained values were very close to each other. Moreover, the stiffness of the eight-ply SMPCs with a 200 μm interlayer was 71.7 N/mm, which is lower than that of the seven-ply with the same interlayer, and of both the seven- and eight-ply SMPCs of the other group of laminates (73.5 N/mm, 73.6 N/mm and 107.3 N/mm, respectively); nevertheless, cracks were not visible, and thus the experimentation was also continued on this sample. After normalization, the elastic modulus was evaluated, with the 100 μm interlayer/three-ply SMPC achieving the highest value of 49.2 GPa.

Table 1.

Average physical and mechanical properties of the manufactured SMPCs.

A temperature calibration test was conducted to determine the appropriate distance between the composite laminate and the tip of the hot gun used to trigger the SM effect. To ensure its activation, the Tg of the epoxy resin (i.e., 120 °C) had to be reached, and thus temperature changes in time had been recorded during the test. The resulting curves are shown in Figure 2b, and a distance of 50 mm was selected to perform memory tests, since a heating plateau temperature of 128 °C was recorded. On the other hand, at the distances of 70 mm and 60 mm, the plateau temperatures were 111 °C and 118 °C, respectively, while 145 °C and 150 °C temperatures were obtained at 40 mm and 30 mm.

Memory tests were conducted in three-point bending by deforming the hot laminates at the same strain of 1%. Then, cooling was performed with the specimens still being constrained for 300 s, and finally, the constraint was removed. The recovery load was also measured via an additional heating–cooling cycle in presence of a constraint. The obtained average data are shown in Table 2, with the nomenclature defined in Figure 3. The reference loads (La, Lmr, Lr and Lrr) increased with the number of composite plies, with the two SMPCs with eight plies recording the highest values. However, the effect related to the two interlayer thicknesses is not evident, as measured loads are very similar. This condition is also reflected by the corresponding stresses; the highest σa is 41.1 MPa, obtained by the 100 μm interlayer/four-ply SMPC, while the 100 μm interlayer/six-ply SMPC had the highest σmr of 30.3 MPa. Variations were also obtained for the σr and the σrr, which were 37.2 MPa and 26.3 MPa, respectively, in the best case (100 μm interlayer/seven-ply SMPC). SM behavior was investigated by calculating the Rf and Rr; all SMPCs showed good behavior, with almost all laminates exceeding 90% for both parameters. Few exceptions were identified, which were above 80% anyway. In particular, the 100 μm interlayer/two-ply SMPC had an Rf and Rr of 87.0% and 88.3%, respectively, while the 200 μm interlayer/two-ply SMPC showed an Rf of 82.6%.

Table 2.

Average values obtained during memory tests.

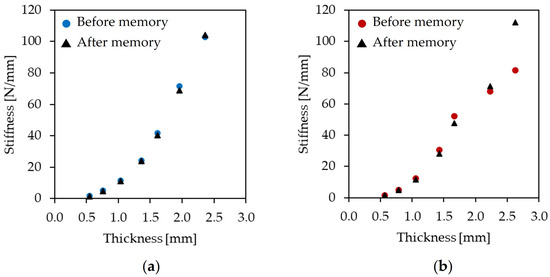

After free recovery, the SMPCs’ stiffness was measured again on one sample for each architecture and compared to its initial value, obtained right after molding; the results are shown in Figure 5. Stiffness measurement confirmed the initial data, and the 200 μm interlayer/eight-ply SMPC, which recorded an unexpected value during the first test, had the highest stiffness value of 112.3 N/mm.

Figure 5.

Stiffness measurement: (a) 100 μm interlayer; (b) 200 μm interlayer.

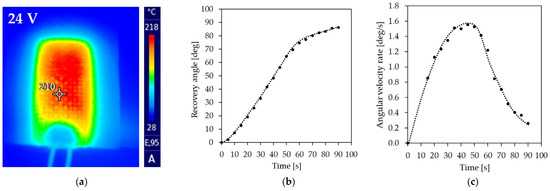

The smart device was prototyped, starting from the two-ply/200 μm interlayer SMPCs, by integrating a microheater. The multilayer structure exhibited a big thickness difference depending on the presence of the heater; in particular, a decrease from 1.22 ± 0.07 mm to 0.63 ± 0.06 mm was measured. The proper functioning of the microheater was investigated by connecting the system to a power supply at 24 V as the infrared camera acquired the temperature. After an initial growth, an average plateau of 210 °C was recorded, as shown in Figure 6a. The smart device was manufactured into a flat shape and then deformed into the temporary configuration by heating. After memorization an L-shape was obtained, and cracks were not visible on its surface. Shape recovery was carried out at 24 V; the recovery angle and the angular velocity rate are reported in Figure 6b,c, respectively. The shape of the former curve was similar to a sigmoid, with rapid growth of the recovery angle for the first 60 s, after which a lower rate was observed. Indeed, by considering the initial curvature to be 90°, the recovered angle after 60 s was already 74.6°, while at the end of the test (90 s from the beginning) it was 86.2°. The angular velocity rate showed rapid growth from the test start until a peak was reached at 1.55 deg/s after 45 s; subsequently, the angular velocity decreased, and at the end it was 0.26 deg/s.

Figure 6.

SMPC device with embedded microheater: (a) thermography; (b) recovery angle; (c) angular velocity rate during recovery.

4. Discussion

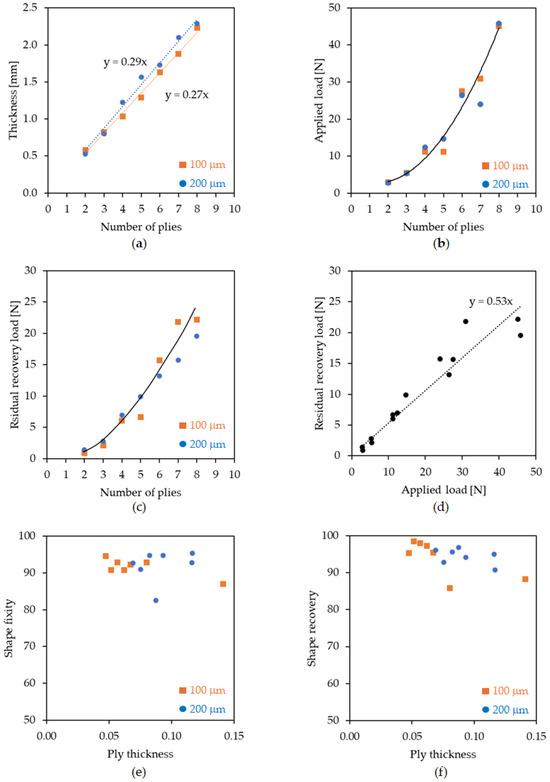

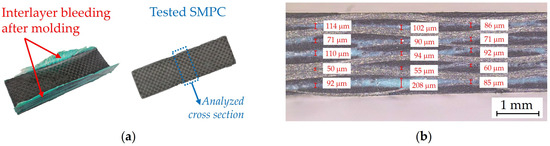

In industrial practice, composite laminates are typically manufactured via autoclave and compression molding. The former permit to achieve the highest performances, but manufacturing costs can be relevant; on the other hand, compression molding technology is simpler, less expensive and the components have good mechanical properties. Traditionally, structures used in high-valued fields such as aerospace, space and defense are manufactured using autoclave molding, but recent advances in materials science, which have promoted the development of new resins, as well as in manufacturing, also permit to consider compression molding as a suitable technology for such applications. Moreover, the number of space missions is continuously increasing, and the aerospace industry has to ensure high performance and cost reduction at the same time; in this scenario, compression molding seems to be a suitable technology to match these needs. For these reasons, the present work uses compression molding to manufacture SMPCs, alternating epoxy-CF prepreg with an interlayer of uncured epoxy resin with SM ability. The number of CFR plies influences the SMPCs physical properties, with the laminate thickness linearly increasing with it; on the other hand, the effect of the interlayer thickness is less evident, since a small increment is observed by doubling the interlayer, as shown in Figure 7a. Since uncured prepregs were laminated, and pressure of 70 kPa was applied for consolidation, a certain level of bleeding was visible after the molding, as shown in Figure 8a. This effect is normal in prepreg molding, since an excessive amount of resin is usually used to impregnate the fibers, and a proper flow of resin (both on the edges and through the plies) ensures the achievement of a good level of agglomeration. However, the SMPCs had an uncured interlayer in direct contact with the epoxy resin of the composite plies. During molding, the epoxy resin bleeding also involves the interlayer, dragging it outside of the composite structure. Thin interlayers are severely affected by this condition, while thicker ones are less susceptible. Indeed, if the interlayer is too small, it is possible for it to be removed by bleeding, while greater thicknesses allow a certain amount to remain. To better understand this phenomenon, in Figure 8b the cross section of the six-ply/200 μm interlayer is shown; the manufactured laminate had an average interlayer thickness of 92 μm, which is 46% of the nominal thickness during lamination. Also, the selection of process parameters influenced this effect, which can be minimized by developing specific solutions. In this experiment, the SMPCs laminated with a 200 μm interlayer thickness were slightly thicker on average than those with 100 μm thicknesses, as shown in Table 1. To evaluate the mass loss due to edge bleeding, the nominal weight of raw materials has been calculated for each architecture; in particular, a mass of 1.0 g has been measured for a prepreg ply of nominal size 30 × 100 mm2, while each interlayer of 100 μm and 200 μm were 0.43 g and 0.86 g, respectively. By calculating the difference between the raw materials and the SMPCs weights, an average mass loss of 12.7% was obtained for laminates with an initial interlayer thickness of 100 μm; 26.6% was obtained for the 200 μm interlayers. This analysis underlined that by doubling the initial interlayer thickness, the mass loss was also doubled. According to these results, the measured densities confirmed that there was a small difference between the two groups of laminates, with the thicker laminates being less dense than the others, since the increment in thickness was due to a greater amount of an unfilled material (i.e., the uncured epoxy powder).

Figure 7.

Correlation of physical and SM ability between SMPCs with 100 and 200 μm interlayers: (a) number of composite plies/thickness; (b) number of composite plies/applied load (i.e., La—load at the end of the heating step of memory test); (c) number of composite plies/residual recovery load (i.e., Lrr—load at the end of the cooling step of the recovery load test); (d) applied load (La)/residual recovery load (Lrr); (e) cured composite ply thickness/shape fixity (Rf); (f) cured composite ply thickness/shape fixity (Rr).

Figure 8.

SMPC with six carbon fiber plies and five interlayers of initial thickness: 200 μm. (a) Manufactured laminate; (b) cross section.

Since SM behavior was triggered by temperature, a calibration test was performed to ensure the correct positioning of the hot gun. By heating, the SMPCs can be deformed into a temporary shape, and after cooling, this configuration can be retained until the temperature is raised again. However, if the temperature is too low, fracture may occur during deformation, while excessive heating can cause polymer degradation. The calibration test allowed us to identify the distance at which the epoxy Tg was exceeded, in order to avoid breakage, but it was also low enough to prevent degradation. The calibration test was conducted on the thickest sample, which required the highest thermal load to be memorized. All the investigated distances between the hot gun tip and the SMPCs permit to achieve the Tg of epoxy resin (Figure 2b), and a gap of 50 mm was selected for subsequent memory tests. This is because greater distances led to significant temperature fluctuations, which did not ensure a uniform heating of the laminates. Although hot temperatures were obtained at distances of 30 and 40 mm, that may cause resin degradation when testing thinner samples. Finally, the time required to reach the desired temperature was measured. Hot gun distance from the laminate and heating time were the inputs in the memory test of the SMPCs. Figure 7b–d show the correlation between the two groups of manufactured SMPCs in terms of memory parameters. In particular, Figure 7b,c report the La (i.e., the applied load during the memory test) and the Lrr (i.e., the residual recovery load at the end of the second test) as a function of the number of composite plies, with both parameters increasing in a parabolic shape. However, it is not possible to identify a difference between the trend of the 100 μm and 200 μm interlayers because of the closeness of the measured values and data scattering. The correlation between the Lrr and the La is reported in Figure 7d. In this case the trend is linear, as an increment of La (i.e., the load required to deform the SMPC at the imposed strain) leads to an increase in Lrr (i.e., the load that the laminate retains for recovery), with a positive correlation. The obtained curve underlines that the Lr is 50% of the La for each of the SMPCs’ architectures. Finally, Figure 7e,f relate the Rf and Rr to the number of composite plies. These two parameters are commonly used to analyze the SM behavior of the materials. Mean values are specified in Table 2, which shows that the Rf of all SMPCs is above 90%, with the only exception being both laminates with two CF plies. Similar results were obtained for the Rr; the laminates with a 100 μm interlayer with two and three CFR plies exhibited an Rr of 88.3% and 85.8%, respectively, while all the other laminates had values of above 90%. The similarity of the measured values was also reflected in Figure 7e,f, where it was not possible to identify any trend between the analyzed parameter and the SMPCs’ architecture. The present implementation of this kind of composites also depends on their durability, since laminates’ properties tend to reduce as the number of memory–recovery cycles increases. Nevertheless, SMPCs manufactured by hand lamination and compression molding were able to undergo 10 cycles without showing cracks or delamination [27]. The effects of memory tests on the mechanical properties of the composite laminates have been investigated by comparing the initial stiffness to the one obtained by testing the memorized SMPCs after free recovery, as shown in Figure 5. Data before and after the test are superimposed, clarifying that the structures were not damaged during the test. An exception to this condition is represented by the laminate with eight CFR plies and a 200 μm interlayer, which showed a higher stiffness after the memory test. It is possible that a measurement error occurred during the first test, since an improvement of stiffness due to memorization does not seem to be reasonable at present.

Finally, a smart device was prototyped; it included two composite plies, an interlayer of 200 μm of SM epoxy resin and an embedded microheater. The architecture was selected on the basis of the memory tests; as no specific trends in terms of SM ability could be identified, the two-ply structure was selected to simplify the lab-scale experimentation. The flat device has been manufactured by compression molding and deformed into a L-shape. The device showed a thickness discontinuity due to the presence of the microheater in only a specific region of the multilayer structure. During memorization, the deformation tended to concentrate along this discontinuity line, creating a potential crack initiation point. The shape recovery test was conducted at 24 V and, as reported in Figure 9, the device was able to recover almost the entire deformation by the end (86.2°). In a previous work, recovery tests were conducted by changing the applied voltage from 18 V and 26 V; it was shown that Lr is slightly influenced by this selection, since shape recovery is obtained whenever the Tg of the SMPCs is exceeded [17]. However, the laminate temperature increases with the applied voltage, and thus should be selected by taking into account the degradation temperature of the epoxy resin. By considering these aspects, as well as the properties of the embedded microheater, 24 V seemed to be a reasonable voltage to perform the recovery test. Both the recovery angle and the angular velocity rate changed over time (Figure 6b,c), since some seconds were needed after the test beginning to reach the plateau temperature. As shown by memory tests, SMPCs are able not only to recover their shape almost completely, but they can provide an actuation load in doing so. By integrating a heating element into the composite structure, the implementation of these smart devices into flying space systems is simplified, since they can be directly connected to the main unit, which can provide the power necessary for heating. After 90 s, the device was able to recover 95.8% of its shape, as shown in Figure 9, with an applied voltage of 24 V, which is typical for spacecrafts.

Figure 9.

Shape recovery of the smart device.

5. Conclusions

SMPCs are promising materials in the space industry thanks to their ability to provide an actuation load during shape recovery. They can be used in solar sails, booms and reflectors to manufacture deploying systems. By changing the composites’ architectures, the magnitude of the actuation load is changed as well. In this work, 14 stacking sequences were investigated by changing the number of composite plies (from two to eight) and the thickness of the SM interlayer (100 μm and 200 μm). Nevertheless, the effect of the former variable was much more evident than the latter, since trends were difficult to identify. All SMPCs showed very good SM behavior, with almost all the Rf and Rr values being above 90%; the best combination was achieved by the 200 μm/six-ply laminate, which recorded 94.8% and 95.7%, respectively. A lab-scale procedure was used to manufacture a smart device with two plies of CFR epoxy, a 200 μm SM interlayer and a microheater, which was embedded into the SMPC. The device was memorized in a L-shape and a recovery angle of 86.2° was obtained, with a maximum velocity of 1.55 deg/s.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.Q.; Data curation, A.P. and F.Q.; Formal analysis, A.P. and L.I.; Investigation, G.P. and L.I.; Methodology, L.I. and F.Q.; Resources, F.Q.; Supervision, F.Q.; Validation, G.P. and L.I.; Visualization, A.P.; Writing—original draft, A.P. and G.P.; Writing—review and editing, A.P. and F.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Fabrizio Betti for his support during the experimentation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CFs | Carbon fibers |

| CFRPs | Carbon fibers reinforced plastics |

| FEP | Fluorinated ethylene propylene |

| La | Applied load |

| Lmr | Memory residual load |

| Lr | Recovery load |

| Lrr | Residual recovery load |

| Rf | Shape fixity ratio |

| Rr | Shape recovery ratio |

| SMAs | Shape memory alloys |

| SMPs | Shape memory polymers |

| SMPCs | Shape memory polymer composites |

| TS | Thermosetting |

| TP | Thermoplastic |

| εu | Residual strain in the specimen at the end of the memory cycle |

| εm | Recovered strain after free recovery test |

| εr | Deformation at the maximum imposed displacement |

| σa | Applied memory stress |

| σmr | Residual memory stress |

| σr | Recovery stress |

| σrr | Residual recovery stress |

References

- Kumar, S.; Ojha, N.; Ramesh, M.R.; Doddamani, M. 4D printing of heat-stimulated shape memory polymer composite for high-temperature smart structures/actuators applications. Polym. Compos. 2024, 45, 15460–15490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, F.; Wang, X.; Wang, B.; Xiao, H.; Duan, Y. 4D printing of 3D carbon-medium reinforced thermosetting shape memory polymer composites with superior load-bearing and fast-response shape reconfiguration. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2409611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garces, I.T.; Ayranci, C. Active control of 4D prints: Towards 4D printed reliable actuators and sensors. Sens. Actuators. A Phys. 2020, 301, 111717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Yu, T.; Chen, M.; Kang, N.; Mansori, M.E. Electrically/magnetically dual-driven shape memory composites fabricated by multi-material magnetic field-assisted 4D printing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2314854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Du, H.; Liu, L.; Leng, J. Shape memory polymers and their composites in aerospace applications: A review. Smart Mater. Struct. 2014, 23, 023001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Zhang, F.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Leng, J. Recent Advances in Shape Memory Polymers: Multifunctional Materials, Multiscale Structures, and Applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2312036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchegolkov, A.V.; Shchegolkov, A.V.; Kaminskii, V.V.; Chumak, M.A. Smart Polymer Composites for Electrical Heating: A Review. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Singh, S.K.; Das, S.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, A. Shape memory polymer and composites for space applications: A review. Polym. Compos. 2025, 46, 11647–11683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Mu, T.; Lan, X.; Zhao, H.; Liu, L.; Bian, W.; Liu, Y.; Leng, J. Structural and damage analysis of a programmable shape memory locking laminate with large deformation. Comp. B Eng. 2023, 259, 110755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeewantha, L.H.J.; Emmanuel, K.D.C.; Herath, H.M.C.M.; Islam, M.M.; Fang, L.; Epaarachchi, J.A. Multi-attribute parametric optimisation of shape memory polymer properties for adaptive orthopaedic plasters. Materialia 2022, 21, 101325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Hao, S.; Lan, X.; Bian, W.; Liu, L.; Li, Q.; Fu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Leng, J. Thermal design and analysis of a flexible solar array system based on shape memory polymer composites. Smart Mater. Struct. 2022, 31, 025021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, T.; Lan, X.; Liu, Y.; Leng, J.; Liu, L. A compliant robotic grip structure based on shape memory polymer composite. Compos. Commun. 2022, 36, 101383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Zhang, F.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Leng, J. 4D printing of electroactive shape-changing composite structures and their programmable behaviors. Compos. Part A-Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2022, 157, 106925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Lu, H.; Ma, H.; Cai, W. Research and Development in NiTi Shape Memory Alloys Fabricated by Selective Laser Melting. Acta Metall. Sin. 2023, 59, 55–74. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Leng, J. Recent progress in shape memory polymer composites: Driving modes, forming technologies, and applications. Compos. Commun. 2024, 51, 102062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, X.; Lin, C.; Li, B.; Zeng, C.; Liu, L.; Liu, Y.; Leng, J. Self-driven intelligent curved hinge based on shape-morphing composites. Compos. Struct. 2024, 345, 118329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iorio, L.; Quadrini, F.; Santo, L.; Circi, C.; Cavallini, E.; Pellegrini, R.C. Shape memory polymer composite hinges for solar sails. Adv. Space Res. 2024, 74, 3201–3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Wu, S.; Xie, D.; Guo, H.; Ma, L.; Wei, Y.; Liu, R. Shape Memory Polymer Composite Booms with Applications in Reel-Type Solar Arrays. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2023, 36, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jape, S.; Garza, M.; Ruff, J.; Espinal, F.; Sessions, D.; Huff, G.; Lagoudas, D.C.; Hernandez, E.A.P.; Hartl, D.J. Self-foldable origami reflector antenna enabled by shape memory polymer actuation. Smart Mater. Struct. 2020, 29, 115011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X.; Liu, L.; Pan, C.; Hou, G.; Li, F.; Liu, Z.; Dai, W.; Wang, L.; Zhang, F.; Sun, J.; et al. Smart Space Deployable Truss Based on Shape-Memory Releasing Mechanisms and Actuation Laminates. J. Spacecr. Rocket. 2023, 60, 1085–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Duan, Y.; Wang, B.; Qi, Y.; He, Q.; Xiao, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Ming, Y.; Wang, F. Cross-linking degree modulation of 4D printed continuous fiber reinforced thermosetting shape memory polymer composites with superior load bearing and shape memory effects. Mater. Today Chem. 2023, 34, 101790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Scarpa, F.; Lan, X.; Liu, L.; Liu, Y.; Leng, J. Bending shape recovery of unidirectional carbon fiber reinforced epoxy-based shape memory polymer composites. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2019, 116, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X.; Liu, L.; Liu, Y.; Leng, J. Thermomechanical properties and deformation behavior of a unidirectional carbon-fiber-reinforced shape memory polymer composite laminate. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2020, 137, 48532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, G.; Li, F.; Xu, M.; Zeng, C.; Zhao, W.; Liu, L.; Liu, Y.; Leng, J. Shape memory cyclic behavior and mechanical durability of woven fabric reinforced shape memory polymer composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2024, 258, 110866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ma, J.; Luo, C.; Fang, G.; Peng, X. A 3D Anisotropic Thermomechanical Model for Thermally Induced Woven-Fabric-Reinforced Shape Memory Polymer Composites. Sensors 2023, 23, 6455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quadrini, F.; Bellisario, D.; Iorio, L.; Santo, L. Shape memory polymer composites by molding aeronautical prepregs with shape memory polymer interlayers. Mater. Res. Express. 2019, 6, 115711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quadrini, F.; Iorio, L.; Bellisario, D.; Santo, L. Durability of Shape Memory Polymer Composite Laminates under Thermo-Mechanical Cycling. J. Compos. Sci. 2022, 6, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santo, L.; Quadrini, F.; Bellisario, D.; Iorio, L.; Proietti, A.; de Groh, K.K. Effect of the LEO space environment on the functional performances of shape memory polymer composites. Compos. Commun. 2024, 48, 101913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).