Abstract

The growing demand from the automotive industry for lightweight, high-performance, and advanced manufacturing techniques for efficient and cost-effective production has accelerated the adoption of fiber-reinforced polymer composites. However, considering the manufacturing complexity of these materials, design remains challenging due to the intricate and interdependent relationships between the process conditions, the part geometry, and the resulting microstructure and quality. This research utilized the Autodesk Moldflow Insight software to design an injection molding process for the manufacturing of discontinuous glass fiber-reinforced polymer parts through computer modeling. A geometrically complex car fender was used as a case study. The effects of various process parameters, particularly gate locations, on the injection-molded parts’ properties (such as the fiber orientation, volumetric shrinkage, and shear rate) were investigated. Multiple injection molding process configurations were designed and simulated, including three, four, and five gates at varying locations. Based on the optimal performance (i.e., low shrinkage, a consistent fiber orientation, and a controllable shear rate), an optimal configuration with four gates at appropriate locations (corresponding to the second gate location set) was identified based on multicriteria decision-making analysis, i.e., volumetric shrinkage of , a fiber orientation tensor of 0.927 ± 0.011, and a stable shear rate < 74,324 (1/s). A reduced strain closure model (modified Folgar–Tucker model) was used to predict the glass fiber orientation. A multicriteria decision-making technique, based on similarity ranking with an ideal solution, was employed to optimize the gate location. The simulation results clearly demonstrate that the gate placement is crucial for material behavior during molding and for reducing common defects. The simulation-based injection molding process design for the manufacturing of discontinuous fiber-reinforced polymer parts proposed in this paper can improve the production efficiency, reduce trial-and-error rates, and improve part quality.

1. Introduction

Lightweight fiber-reinforced polymeric composites (FRPCs) offer numerous advantages in the automotive industry, primarily due to their high strength-to-weight ratio and design flexibility. This reduces the vehicle weight, thereby improving its fuel efficiency and performance, while increasing the manufacturing and design complexity and flexibility [1]. Engineers often use plastics as an alternative to metals/sheet metals such as steel and aluminum to achieve these goals because they are easier to form, rust-resistant, and easy to manufacture [2]. On the other hand, plastics are generally weaker, especially at high temperatures, and are more susceptible to environmental degradation and damage. While plastics are versatile and cost-effective, FRPCs exhibit better resistance to fatigue, creep, and environmental degradation and have superior strength, stiffness, and durability, making them more suitable for demanding applications [3]. Continuous fiber-reinforced polymers (CFRPs) generally have higher strength and stiffness than discontinuous fiber-reinforced polymers (DFRPs) due to the continuous alignment of the fibers, which allows them to more effectively transfer loads and resist deformation. CFRPs are also known for their high strength-to-weight ratio, making them suitable for applications where lightweighting is crucial. However, CFRPs can be significantly more expensive and complex to manufacture than DFRPs. Meanwhile, DFRPs are appropriate choices when manufacturability, cost-effectiveness, and design flexibility are priorities, such as in the automotive industry [4,5,6,7,8,9].

Injection molding with DFRPs offers several advantages in terms of manufacturability and cost-effectiveness compared to other manufacturing processes. (1) Improved formability: The discontinuous nature of the fibers allows the composite materials to flow and form more freely during the molding process. This is particularly advantageous in producing complex geometries that may be challenging or impossible to achieve using CFRPs. (2) Fast and repeatable production cycles: Injection molding is a highly automated process, known for its fast cycle times. Once the mold is created, parts can be produced quickly and consistently, making it ideal for high-volume manufacturing. (3) Reduced quality control issues: The precision of injection molding and the automated process reduce variability and defects compared to other methods, reducing the need for extensive quality control measures. (4) Easy design modification: Once the initial mold is created, design changes can be implemented and accommodated with relative ease. (5) Economies of scale: While the initial tooling costs for injection molding can be high, unit costs decrease substantially as production volumes increase. (6) Lower material costs (compared to CFRPs): DFRPs can use less expensive discontinuous fibers compared to CFRPs. (7) Minimized waste: Injection molding can inject the exact amount of material needed, minimizing waste and making it possible to recycle excess material in the gate. (8) Lower labor costs: The high degree of automation in injection molding reduces the need for labor, further saving costs. Based on the above description, injection molding with DFRPs can efficiently produce complex parts in large quantities at a lower unit cost, making it a compelling choice for various applications, especially in the automotive industry [10,11,12].

Compared to standard injection molding, DFRP injection molding presents unique challenges due to fiber discontinuity and their interaction with the polymer matrix. The injection molding process results in a complex fiber orientation and distribution within the molded parts. The fiber orientation contributes to anisotropy in the molded parts, which in turn affects their mechanical properties. Mechanical properties such as strength and stiffness vary significantly depending on the fiber length, shape, thickness, orientation, and dispersion. Shear forces during the injection molding process can cause fiber breakage and shortening, impacting the part’s mechanical properties. Overall, the presence of fibers affects the material flow during mold filling, which in turn affects the final physical properties of the part. The mechanical behavior of DFRPs is primarily determined by their fiber strength and modulus, matrix strength, and chemical stability and the contact bond between the fiber and the matrix, which facilitates stress transfer. All of these factors present challenges in injection molding process design [13,14,15].

Computer modeling plays a vital role in the design and optimization of the injection molding process for DFRP parts. It is particularly valuable for these materials due to the complex interplay between the processing conditions, fiber behavior, and final part properties. The fiber orientation is influenced by the flow of the molten polymer and the mold geometry during injection molding and is a major determinant of the strength, stiffness, and overall mechanical properties of the final part. Different fiber orientations can significantly affect these properties. Computer modeling can effectively help to predict potential problems during the injection molding process, such as warpage, shrinkage, and weld line formation, and allows for adjustments to design or process parameters before physical prototyping begins. Traditional methods often require costly and time-consuming trial and error with prototypes. Computer modeling enables engineers to explore the effects of different process parameters (e.g., melt temperature, injection pressure, fill speed, etc.) on the fiber orientation and other properties and to determine the optimal conditions for the manufacturing of high-quality parts. By reducing design iterations, minimizing defects, and optimizing processing parameters, computer modeling simplifies the injection molding process, thereby improving the production efficiency and reducing the manufacturing costs [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27].

Wittemann et al. focused on the fiber–flow interactions and investigated the fiber-induced anisotropic flow behavior using a novel reactive injection molding simulation method based on a fourth-order viscosity tensor. The matrix viscosity was modeled as non-Newtonian, and the dynamics were taken into account. In addition, the cavity pressure and fiber orientation were validated with experimental data, and the results showed good agreement [16]. Panduv and Sawant investigated the creation and production of an axle composed of glass fiber and epoxy resin and evaluated them under various mechanical loads using finite element analysis (FEA) software (ANSYS R15). The study highlighted the potential of glass DFRPs as a lightweight and potentially more efficient alternative to conventional materials for parts where weight and mechanical performance are critical [17]. Knoll and Heim performed a comparison between simulation results (generated by the Moldflow Insight Ultimate software 2019.0.2, Autodesk Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA) and experiments using molds of different complexity levels. Unlike many previous studies, they compared the time series of part characteristics and process parameters. The study showed that the similarity between simulations and experiments depends on the operating point, the production scenario and its dynamics, and the availability of material data [18]. Pyata et al. conducted extensive simulation-based studies using the Autodesk Moldflow software 2019.0.2 to characterize the contributing issues related to the part quality and achieved topological optimization by reducing key parameters such as shrinkage and warpage, while ensuring that the overall cycle time was suitable for industrial production rates. Different gate locations were simulated, and the optimal gate locations were selected for a dual-gate system. The results showed that the average cycle time required to produce a recycled olefin plastic part with dimensions of 200 mm × 100 mm × 1.5 mm was 10.42 s, with volumetric shrinkage of 5.08%, warpage of 1.05 mm, and a clamping force of 79.81 tons (a reduction of 60.57%) [19]. Żurawik et al. investigated the shortcomings of the injection molding model used in Moldflow software (FCS 40.0.26.0) simulations and the influence of process and model parameters. The actual fiber orientation (measured by X-ray microtomography) and the simulated fiber orientation of injection-molded short glass fiber-reinforced polyamide were compared. The results showed that different orientation regions appeared in the samples, which could not be represented by a simulation with only one parameter changed. Multiple simulations must be performed to represent the flow regions occurring in the sample as realistically as possible [20]. Szabó et al. studied the behavior of polypropylene filled with glass beads during the injection molding process. In the experiments, mixtures with different filler content and different bead sizes were prepared by extrusion. The effects of different injection molding parameters were measured, and the segregation of fillers was studied. At the same time, the segregation was numerically simulated with Moldflow and discrete element modeling [21]. Li et al. focused on predicting the failure strength of injection-molded DFRPs with complex fiber distributions. Based on a multiscale modeling approach, a parameterized failure criterion was proposed. At the microscale, a representative volume element model with multiple constituents and different fiber orientation distributions was established. At the mesoscale, a skin–core–skin model was proposed that took into account the variation in the fiber orientation along the thickness direction, i.e., a layered structure. The parameters of the model were extracted from the injection molding simulation results using the Moldflow software (Moldex3D ver2021). The numerical analysis and bench tests verified the effectiveness and accuracy of the proposed parameterized failure criterion [24]. Kameya et al. numerically analyzed the effect of the weld line strength of glass DFRPs during injection molding. The analysis showed that the locations of the weld lines are crucial to the structural strength, depending on the type of material. Therefore, improvement strategies for the weld line should be considered according to the material type and strength [25]. Chang and Su used numerical simulation to study the effects of glass fiber properties on the prediction of warpage formation during injection molding. An optimization method based on the reverse warping agent model was proposed. The results showed that the glass fiber orientation and other parameters may significantly affect the warpage of products [26]. Isaincu et al. conducted a numerical study on the effect of the fiber orientation on the mechanical responses of DFRPs by coupling FEA software such as Moldflow 2019.0.5, Digimat 2020, and Ansys 2020R1. Mechanical evaluation was performed by coupling Ansys with Digimat to consider the anisotropic behavior of the material. Different mapping procedures and mesh sizes for the Moldflow model and Ansys model were considered. The results showed that ignoring the effect of the fiber orientation on such materials leads to unrealistic results [27].

A car fender is a highly representative example of a component that can be used to fully explore and validate the advantages of computer modeling for the injection molding of DFRP parts. The complexity of the part’s geometry and the material’s anisotropic properties, balancing shrinkage, the fiber orientation, and dimensional stability, are critical. The demands for high performance and manufacturability make this an ideal case study for the validation of injection molding process design using computer modeling [28,29,30,31,32,33]. In this study, a car fender, composed of discontinuous glass fiber-reinforced polypropylene (DGFRP) composites, was chosen. The design of the injection molding process for the production of car fenders was performed by computer modeling using Moldflow Insight 2024. The effects of various process parameters, particularly the gate placement, on the most important characteristics of the injection part, such as the fiber orientation, volumetric shrinkage, and shear rate, were investigated. A multicriteria decision-making (MCDM)-based Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) was adopted to determine the optimal gate placement to achieve optimal performance, i.e., lower shrinkage, a consistent fiber orientation, and a manageable shear rate, resulting in excellent dimensional accuracy and process stability. The reduced strain closure (RSC) model (a refined Folgar–Tucker model) was used to predict the glass fiber orientation.

2. Materials and Methods

This work aimed to design an injection molding process for DGFRP car fenders, specially optimizing the gate placement. Autodesk Moldflow Insight 2024 was used to analyze the effects of the process parameters on important material characteristics, such as the fiber orientation, flow shear rate, volumetric shrinkage, and part warpage. Moldflow Insight, based on computational fluid dynamics (CFD) principles, was used to analyze and simulate fluid flow behavior, such as simulating the flow of molten plastic (a fluid) and how it fills the mold and predicting the flow patterns, temperature distribution, pressure fields, cooling efficiency, and fiber orientation. Moldflow uses FEA to discretize the geometry of the part and mold into meshes (typically tetrahedral elements for a 3D model) and then solves the relevant equations for the meshes, such as the Navier–Stokes equations that govern fluid motion.

2.1. Fiber Orientation Prediction Models and Process Governing Equations

Fiber orientation prediction involves determining the spatial distribution of fibers within each element and predicting their positions through the thickness of the part. The numerical prediction of the 3D fiber orientation during molding filling is based on equations of motion for rigid particles in a fluid suspension [34,35,36,37,38,39,40].

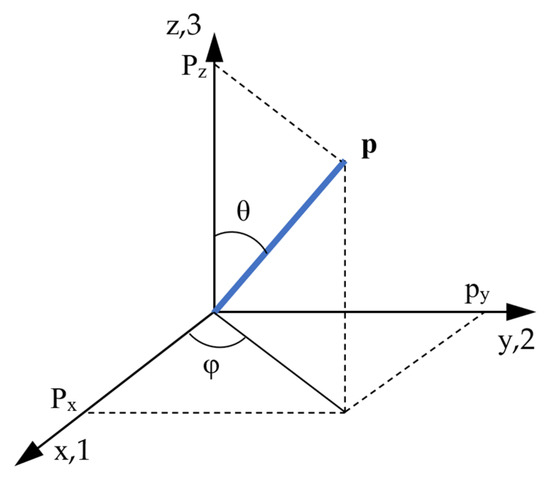

Assuming that the fibers are rigid, cylindrical, and uniform in length and diameter, they can be represented as a unit vector, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of a unit fiber orientation.

A fiber (vector) of unit length p can be represented by the projection of its components onto the x, y, and z axes at angles θ and φ:

In concentrated suspensions, the interaction between fibers cannot be ignored. Folgar and Tucker proposed a statistical method that defines the distribution function, ψ(p,t), as the probability of the orientation of a fiber group in space and time [37]. This method has become the best method for modeling the fiber orientation in concentrated suspensions. When the fiber is axisymmetric and the conditions at both ends are the same, ψ(p) = ψ(−p) holds. The integral of ψ(p,t)dp gives the probability that the fiber is oriented between p and p + dp at time t, as follows:

The governing equations for a flow in Moldflow Insight include the conservation equations for mass, momentum, and energy, known as the Navier–Stokes equations. These equations are tailored to the specific analysis type (e.g., 3D flow, fiber orientation) and material properties. In addition, fiber orientation analyses utilize the RSC model.

Conservation of mass for a fluid describes how the density of the fluid changes over time, ensuring that mass is neither created nor destroyed [41]:

where ρ is the suspension density, t is time, and V is the velocity vector. If incompressibility is assumed, then , which is not generally true.

Conservation of momentum describes how forces, including pressure, viscous stress, and gravity, affect the motion of the fluid [41,42]:

where P is the pressure vector, τ is the viscous stress tensor, and g is the gravitational acceleration vector.

Conservation of energy involves the temperature distribution within the fluid, taking into account heat transfer and heat dissipation [41,42]:

where T is the temperature, k is the thermal conductivity, Cp is the specific heat capacity, and β is the expansion coefficient, which is defined as .

Other specialized models include the following.

The reduced strain closure (RSC) model for fiber orientation analysis improves the Folgar–Tucker equation to account for fiber–fiber interactions, which significantly affect the fiber orientation during processing. It uses a phenomenological parameter to simulate slow orientation dynamics [43,44]:

where aij is the fiber orientation tensor, ωij is the velocity tensor, and is the deformation rate tensor. Cl is the fiber interaction coefficient, a scalar phenomenological parameter whose value is determined by fitting experimental results. The fourth-order tensors Lijkl and Mijkl are defined as

where σp is the p-th eigenvalue of the orientation tensor aij, and is the i-th component of the p-th eigenvector of the orientation tensor aij. The scalar factor κ is a phenomenological parameter, and κ ≤ 1 indicates the slow orientation dynamics. A smaller scalar factor κ indicates the slower flow-dependent development of the orientation tensor and a thicker orientation core. When κ = 1, the RSC model simplifies to the original Folgar–Tucker model.

The Moldflow second-order viscosity model uses a quadratic formula to describe the change in viscosity with the temperature and shear rate. It can take into account the complex viscosity behavior of thermoplastic materials. The viscosity model is given by the following equation [45]:

where η is the viscosity, is the shear rate, and A to F are the data-fitted coefficients.

2.2. Specific Considerations for Computer Modeling

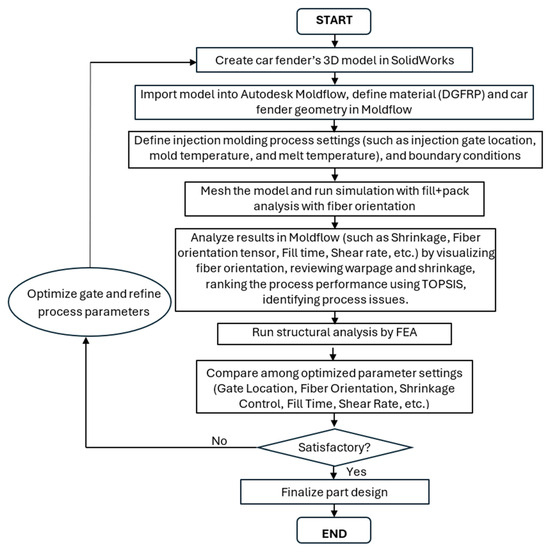

Essentially, Moldflow Insight utilizes advanced numerical methods to analyze the flow of molten plastics and the behavior of fibers within the mold cavity to simulate the composite injection molding process. It considers factors such as the fiber orientation, shear stress, temperature distribution, and cooling effects to predict part quality and optimize the manufacturing process. The computer modeling flowchart is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the computer modeling procedure for the injection modeling process design of a car fender.

When using Moldflow Insight to simulate the DFRP injection molding process, several key factors must be considered to ensure accurate predictions and reliable results.

Overall governing equations for simulation: In 3D injection molding flow analysis, Moldflow Insight uses fundamental CFD (a combination of the Navier–Stokes equations and other governing equations) to describe the flow behavior of the polymeric composites within the mold cavity. The governing equations are discretized and then assembled and solved using finite elements to simulate the flow within the 3D cavity [46]. For the pressure–velocity solution, the equations are solved using the standard FEA method. This includes material incompressibility at all process stages. For the temperature (energy conservation) solution, the equations are also solved using standard FEA. At each step, iterations between the temperature and pressure–velocity equations are completed until convergence is achieved.

Fiber orientation prediction: Fiber alignment in injection-molded composites is laminar in nature and is affected by factors such as the filling speed, processing conditions, material behavior, fiber aspect ratio and concentration, gate placement, etc. Shear flow tends to align fibers in the flow direction, while stretching flow tends to align fibers in the stretching direction. Moldflow’s fiber orientation models (e.g., the RSC model—a modified Folgar–Tucker model) provide more accurate predictions for a wide range of materials and fiber content. If not properly accounted for, the fiber orientation can be significantly overestimated [43].

Gate placement: The quality of injection-molded DFRP parts is significantly affected by the gate placement. Factors affecting gate placement that need to be considered include the following: (1) gate locations are often constrained by the part geometry and the desired fiber orientation; (2) gate placement can be optimized to minimize the injection pressure, uneven filling patterns, and temperature differences during mold filling; (3) optimal gate placement helps to avoid or minimize common molding defects such as weld lines, depressions, warpage, volumetric shrinkage, shear rate anomalies, material splashing, etc.; (4) other key considerations include the cooling system design and the determination of multiple gates. The gate placement affects the cooling process, which in turn affects the solidification time and temperature distribution of the molded part. For large or geometrically complex parts, multiple gates can be used to achieve balanced filling and prevent deflection or deformation. Computer modeling can be a powerful tool to provide detailed information about the molding process to optimize the design of gate locations [47].

Heat transfer and cooling analysis: Injection molding process modeling is true 3D modeling. Energy conservation equations govern the heat transfer between the molten material and the mold, accounting for conduction, convection, shear heating, and compressive heating. The external heat transfer coefficients represent the heat transfer at the mold–melt interface and can be adjusted by the user to suit specific mold conditions. Moldflow Insight uses a numerical method developed from the boundary element method (BEM). From a physical perspective, the BEM treats all boundaries as heat sources (heat gain/loss) during the solution process. Mold cooling simulations use the BEM and boundary conditions to solve the heat transfer equation (Laplace’s equation) and determine the temperature distribution within the mold [48].

2.3. Gate Placement Optimization

The Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) is a multicriteria decision-making (MCDM) method that can be used to optimize gate placement in injection molding in Moldflow Insight [49,50,51,52,53]. TOPSIS aims to find the best alternative (in this case, potential gate locations in the case of multiple gates) by determining the gate location that is closest to the ideal solution and furthest from the negative ideal solution.

The steps involved in applying TOPSIS are as follows: (1) define the candidate gates, i.e., identify potential gate locations on the part model using the Gate Location Analysis feature of Moldflow Insight, which recommends regions based on the minimum pressure or a balanced flow; (2) establish criteria by selecting relevant criteria to evaluate gate locations, such as minimizing the injection pressure, uniform filling and holding pressure, minimizing the flow path length, reducing the possibility of defects (e.g., weld lines, sink marks), aesthetics; (3) generate data by performing injection molding simulation and mold flow analysis (e.g., filling, holding pressure) for each potential gate location to obtain quantitative data for the selected criteria; (4) normalize the decision matrix by converting the raw data into a dimensionless scale so that the criteria can be compared even when using different units of measurement; (5) assign weights by determining the relative importance of each criterion based on expert judgment or other weighting methods; (6) calculate the separation metric by calculating the geometric distances of each alternative from the positive ideal solution (the best performance for each criterion) and the negative ideal solution (the worst performance); (7) determine the relative proximity of each alternative to the ideal solution by calculating its distances from the positive and negative ideal solutions; (8) finally, rank the alternatives based on how close the potential gate locations are to the ideal solution, with the one with the highest value being the best choice.

2.4. Car Fender and Related Information

This study uses the front fender of an automobile part with a complex geometry as a case study. Car front fenders are essential for both safety and aesthetic reasons. They block road debris, prevent damage to the vehicle body, and contribute to the vehicle’s aerodynamic profile (smooth surface and curved surfaces). In particular, in the event of a collision, fenders can absorb the impact energy, minimize damage to the passenger compartment, and potentially reduce the severity of injuries. The front fenders have traditionally been composed of steel or aluminum. However, the materials used for fenders have evolved over time, especially in the field of lightweight vehicles, aiming at improving their fuel efficiency and corrosion resistance. In this study, the material of the car fender was composed of a discontinuous glass fiber-reinforced polypropylene (DGFRP) composite (manufacturer: Japan Polypropylene Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The material properties were provided by the Autodesk Moldflow Insight database [54]. The selection of the part material and the injection molding manufacturing process was based on factors such as vehicle design, cost considerations, the required performance characteristics (e.g., strength and lightness), and manufacturing techniques. Figure 3 schematically shows different views of the part drawing [55]. The car fender dimensions are 650 mm (height) × 1160 mm (width) × 235 mm (depth) × 2.8 mm (thickness). This study aims to analyze the effects of the injection molding process parameters, especially the gate placement, on the part quality (e.g., fiber orientation, defect formation (warpage and shrinkage), shear rate, etc.), in order to optimize these process parameters. Important process information and performance aspects, including the shear rate, shrinkage, and fiber orientation, were carefully examined. The injection molding simulation software Autodesk Moldflow Insight 2024 and MATLAB 2024a were used to evaluate the injection molding process and the overall behavior of the car fender part under various molding conditions.

Figure 3.

Schematic drawing of the car front passenger-side fender composed of a DGFRP (symmetrical to the driver’s side). (a) Front view with dimensions of 650 mm (height) × 1160 mm (width) × 235 mm (depth) × 2.8 mm (thickness); (b) right-side view; and (c) top view.

Table 1 lists the properties of the DGFRP material, which is 20% high-modulus discontinuous E-glass fiber-reinforced polypropylene composite, produced by the Japan Polypropylene Corporation. The property data were provided by the Moldflow Insight database.

Table 1.

Material properties of the DGFRP (data provided by Moldflow Insight).

Moldflow Insight uses several key process parameters to simulate and optimize the injection molding process. These parameters control the filling, holding, and cooling stages of the molding process, and their proper setting is crucial in achieving high-quality parts. Key parameters include the injection speed, melt temperature, mold temperature, injection pressure, holding pressure, cooling temperature and time, and gate location.

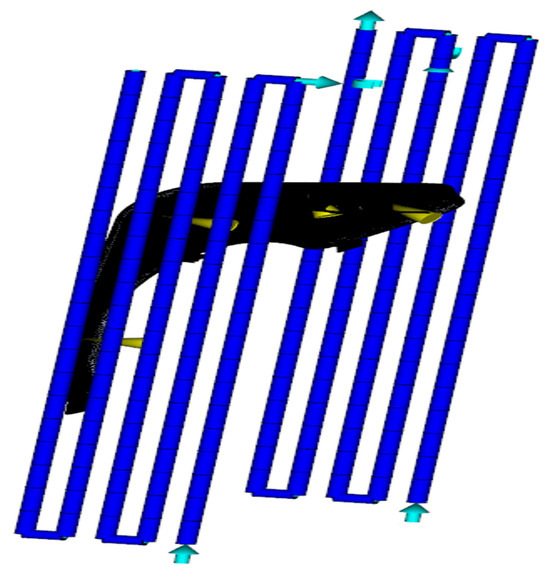

2.5. Injection Molding Model Design Brief

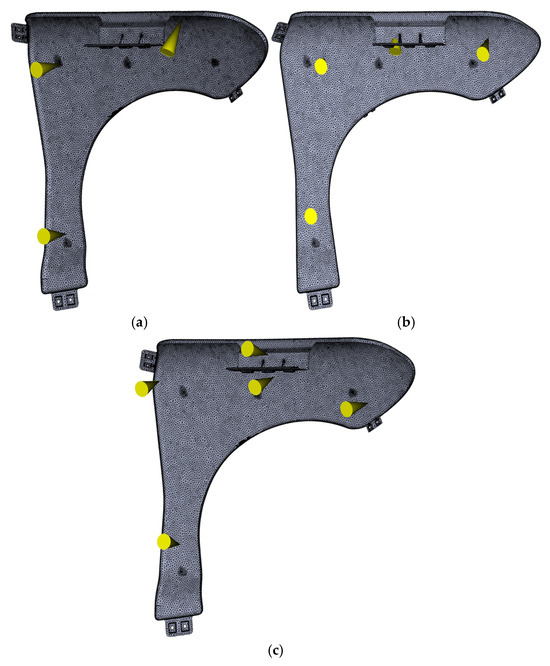

In addition to the material selection and part geometry determination mentioned above, the injection molding process considerations include (1) determining the clamping force/pressure to ensure that the mold is firmly clamped before and during injection molding; (2) properly controlling the injection speed and pressure to ensure that the mold cavity is completely filled; and (3) ensuring that the cooling system design allows sufficient cooling time for the polymer to solidify in the mold. In injection molding, an effective cooling channel system is crucial to maintaining cooling consistency, reducing warping, shrinkage, and residual stress, and improving the manufacturing efficiency, ultimately producing parts with accurate dimensions and good mechanical properties. Furthermore, to avoid flow turbulence and ineffective cooling, the cooling channel layout for locations with higher heat generation needs to be optimized, and the coolant flow needs to be adjusted to maintain constant circulation. Moldflow Insight 2024 can facilitate refinement in cooling methods to improve the efficiency. Figure 4 shows a schematic layout of the cooling methods in the injection molding model. Moreover, the locations of the injection gates are critical in molding high-quality parts. This is because the gate placement significantly affects the flow behavior of the polymer melt, which in turn affects the final fiber orientation, which in turn determines the mechanical properties of the finished part. Depending on the part’s geometry, three, four, and five gates and adjusted different gate locations were designed for optimization, as shown in Figure 5. Based on the recommendations of Moldflow Insight, the key injection molding process parameters that served as the initial optimal settings for this case study were as listed in Table 2.

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of the cooling channel layout on both sides of the part.

Figure 5.

Meshed models for computer modeling: (a) 3-gate model, (b) 4-gate model, and (c) 5-gate model.

Table 2.

Injection molding process parameters (default conditions provided by Moldflow Insight).

2.6. Mesh Generation

When simulating the injection molding process of DGFRP parts, performing a mesh-independent study is crucial in ensuring accurate and reliable simulation results. Start with a relatively coarse mesh to establish a baseline for the computational cost and initial results. Select a mesh type appropriate for the geometry and physics of interest. In this case, tetrahedral elements, suitable for complex shapes, were chosen. When determining the initial element size, consider the thickness and features of the part. Then, use the temperature characteristic (e.g., the maximum temperature across the domain) as the comparative quantity. Progressively refine the mesh by reducing the element size or increasing the number of elements, especially in critical areas or regions with high stress/deformation gradients. Ensure that the mesh is sufficiently fine to capture process details, especially in areas or regions with thickness variations, thin-walled sections, gates, and potential weld lines. Once the temperature characteristic (maximum temperature) is stable (converged) and the computational settings (e.g., the element size and number) are feasible, the element size and number should be appropriately selected. The final meshed part with different gates is shown in Figure 5. The mesh information for the final mesh used for computer modeling is listed in Table 3. There are no inverted tetrahedral elements, and there are no collapses at the model boundary. The optimal mesh is fine enough to capture critical features and gradients but not overly fine, which would result in unnecessarily long computation times. Therefore, tetrahedral mesh refinement is satisfactory according to the software criteria.

Table 3.

The final mesh adopted for modeling after the mesh-independent study.

3. Results and Discussion

This study used Autodesk Moldflow Insight 2024 to simulate, analyze, and optimize the injection molding design of a DGFRP car fender. The comprehensive injection molding process simulation not only solved the Navier–Stokes equations and other combined governing equations but also incorporated standard material properties and models. The following sections present and discuss the major results and findings from this case study.

3.1. Injection Molding Process Analysis

Autodesk Moldflow Insight is a powerful tool for injection molding process simulation, analysis, and optimization. Engineers and designers can use its capabilities to optimize mold designs, identify potential defects, and refine process parameters to produce high-quality parts. Simulation results, such as the fill time, shear rate, shrinkage, and fiber orientation, can be used as evaluation criteria, combined with the MCDM approach using the TOPSIS method, to rank gate placements to determine the optimal gate placement.

3.1.1. Glass Fiber Orientation Analysis

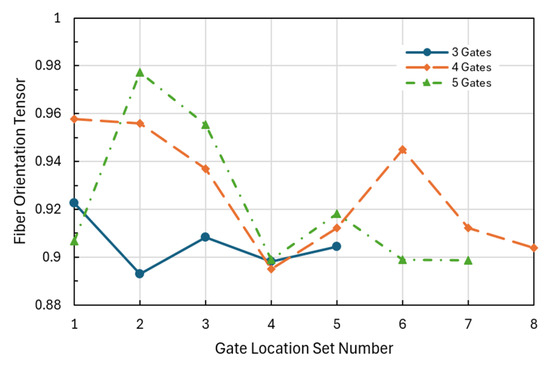

For glass fiber orientation analysis, modeling can provide insights into how short fibers align within the polymer matrix in the molded part, thereby predicting their spatial distribution and its impact on the final part properties. Figure 6 compares the fiber orientation tensor and gate location settings for different gate numbers. The results are crucial in understanding how the flow of fiber-filled plastics affects the material properties, shrinkage, and warpage, with the average result being particularly useful for thin parts. The fiber orientation tensor is a mathematical tool that represents the probabilistic alignment of fibers within a molded part. It is typically a second-order tensor (a 3 × 3 matrix). It quantifies the degree of alignment in specific directions, with values close to 1 indicating a strong preference for a particular orientation. For the three-gate case, five gate location sets were designed. The fiber orientation tensor values vary between 0.893 and 0.923, and gate set #1 reaches the highest value of 0.923, while gate set #2 reaches the lowest value of 0.893. For the four-gate case, eight gate location sets were designed. The fiber orientation tensor values vary between 0.895 and 0.958, and gate sets #1 and #2 reach the highest values of about 0.957–0.958, while gate set #4 reaches the lowest value of 0.895. For the five-gate case, seven gate location sets were designed, and the fiber orientation tensor values vary between 0.899 and 0.977. The fiber orientation tensor reaches the highest value of 0.977 for gate set #2, much higher than those at the other gate locations, and gate sets #4, 6, and 7 reach the lowest values of about 0.899. A higher degree of fiber alignment is crucial for achieving better mechanical properties, structural integrity, and performance consistency in injection-molded DGFRP car fenders.

Figure 6.

Comparison of glass fiber orientation tensors and gate location settings for different gate numbers designed in a car fender sample.

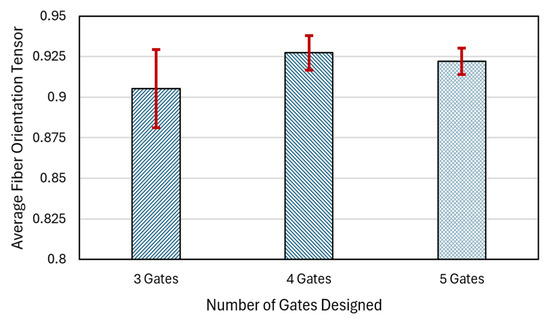

To determine the consistency of fiber alignment, a standard deviation index can be used. A lower standard deviation is directly correlated with fewer fluctuations and higher uniformity in the fiber orientation, better mechanical integrity, a longer service life, and a more uniform stress distribution. Figure 7 summarizes the fiber orientation distribution analysis via a bar chart comparing the average fiber orientation tensor over the different gate location settings, with corresponding standard deviations for different gate numbers. For the three-gate case, the average value is 0.905, and the standard deviation is 0.024 (i.e., 0.905 ± 0.024). For the four-gate case, the results are 0.927 ± 0.011. For the five-gate case, the results are 0.922 ± 0.008, similar to the four-gate case and much lower than in the three-gate case.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the average fiber orientation tensor with corresponding standard deviations for different gate numbers designed in a car fender sample.

3.1.2. Shrinkage Analysis

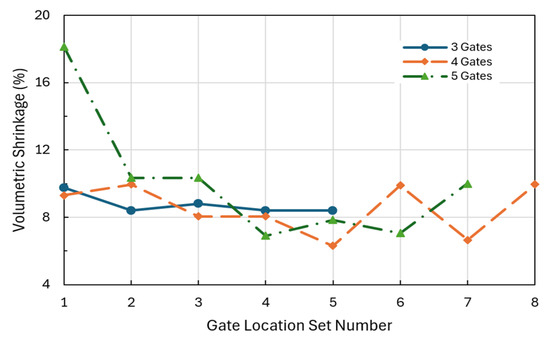

Volumetric shrinkage analysis predicts the dimensional changes that occur after part demolding due to the material properties and processing conditions, enabling designers to determine the correct mold shrinkage allowance required to achieve final part dimensions within the defined tolerance. Figure 8 shows the relationship between the volumetric shrinkage and the gate location setting for different gate numbers designed in the car fender sample, indicating the dimensional stability and deformation probability of the molded product. The lower the volumetric shrinkage, the better.

Figure 8.

Comparison of the volumetric shrinkage and gate location settings for different gate numbers designed in the car fender sample.

For the three-gate case, the shrinkage is relatively stable, ranging from 8.4% to 9.8%. For the four-gate case, the shrinkage ranges from 6.3% to 10.0%. For the five-gate case, the shrinkage ranges from 6.9% to 18.2%. As seen for gate location set #1, high shrinkage can lead to warpage and dimensional instability.

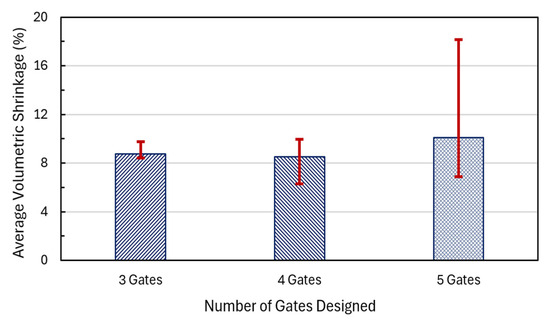

Figure 9 summarizes the volumetric shrinkage analysis via a bar chart comparing the average volumetric shrinkage of the different gate location settings, with deviations for different gate numbers, designed in a car fender sample. For the three-gate case, the average volumetric shrinkage is approximately 8.8%, and the positive deviation is 1.0% and the negative deviation is −0.35% (i.e., ). For the four-gate case, the shrinkage is the lowest (). For the five-gate case, the shrinkage is the highest (). Overall, the four-gate case maintains the lowest average shrinkage, indicating greater dimensional accuracy.

Figure 9.

Comparison of the average volumetric shrinkage with deviations for different gate numbers designed in a car fender sample.

3.2. Gate Location Design and Optimization

In DFRPs, gate location selection is crucial in achieving the desired mechanical properties, minimizing defects, and ensuring efficient mold filling. Appropriate gate design allows for a targeted fiber orientation, thereby enhancing the strength, reducing warpage, improving the part aesthetics, and optimizing the overall quality. Computer-aided engineering tools and simulation software can help to optimize the gate placement to predict and mitigate potential issues before mold construction.

After conducting the aforementioned injection process analysis for various gate numbers (i.e., three, four, and five gates) and the corresponding gate locations, the next goal was to determine the most appropriate number of injection gates and gate locations that correlated with the shrinkage, fill time, shear rate, and fiber orientation. Table 4 lists the results for various gate numbers (three, four, and five gates) and locations.

Table 4.

The injection molding process behavior with different gate numbers and locations.

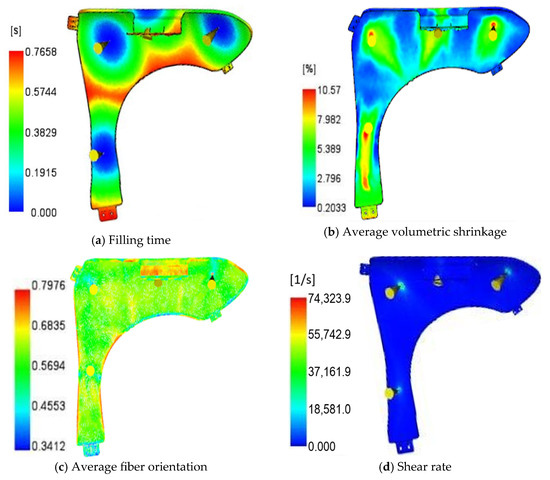

To optimize gate locations in Moldflow Insight based on the fill time, shear rate, shrinkage, and fiber orientation, a gate location analysis with the Gate Region Locator algorithm was used. This algorithm determines the optimal gate location by considering factors such as the part geometry, flow resistance, and thickness. Factors such as the fill time, shear rate, shrinkage, and fiber orientation were integrated into the MCDM approach, and the TOPSIS method was used to rank gate locations based on criteria such as fiber alignment uniformity and shrinkage reduction. By analyzing the results regarding the fill time, shear stress, shrinkage, and fiber orientation, designers can optimize gate locations to improve the part quality and reduce the cycle time. Ultimately, the optimal gate locations were selected, consisting of four gates with gate location set #2, as shown in Table 4. Figure 10 shows the detailed distribution of the injection molding process factors for the optimal gates (the four-gate case) and the corresponding locations (gate location set #2), corresponding to the results listed in Table 4.

Figure 10.

Process factor distributions of the optimal gate number (4 gates) with the corresponding gate location set #2. (a) Fill time; (b) volumetric shrinkage; (c) fiber orientation; and (d) shear rate.

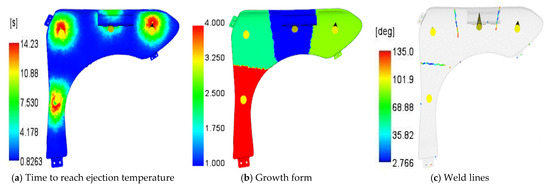

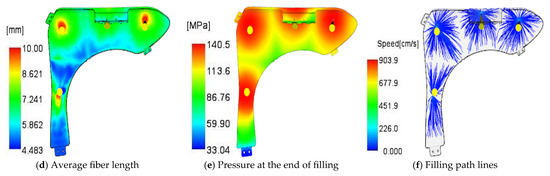

Additional process characteristics of the sample for the optimal gate configuration (four-gate) with the corresponding gate locations (gate location set #2) are shown in Figure 11, including (a) the time to reach the ejection temperature, (b) the injection material growth form, (c) weld lines, (d) the average fiber length, (e) the pressure at the end of filling, and (f) filling path lines.

Figure 11.

Process factor distributions for the optimal gate number (4 gates) with corresponding gate location set #2. (a) Time to reach ejection temperature; (b) injected material growth form; (c) weld lines; (d) average fiber length; (e) pressure at the end of filling; and (f) filling path lines.

To produce consistent and uniform parts, the material must flow smoothly, have a uniform temperature, and complete the filling process equally at each gate. However, as shown in Figure 11a, the material temperature near the gate area is higher, requiring a longer cooling time to reach the ejection temperature. The injected material from each gate eventually merges at the flow front, forming different-colored growth areas, as shown in Figure 11b. This front flow forms weld lines, as shown in Figure 11c. If the temperature in the weld line region is too low and the injection and holding time is too short, preventing the chemical fusion of the material from different gates, the weld lines will become sources of defects and easily fracture under a load. The fiber length distribution, as shown in Figure 11d, is largely dependent on or contributes to the pressure distribution. Longer fibers move more vigorously, generating higher local pressure, as shown in Figure 11e. The injected material flow path lines indicate the flow direction of the fiber material, as shown in Figure 11f. Overall, four gates with the corresponding gate locations (set #2) is the optimal gate number and gate location design for the manufacturing of high-quality car fender parts because they provide the best overall balance, with low shrinkage, reasonable shear rates, an optimal fiber orientation, etc.

4. Conclusions

This study used the Autodesk Moldflow Insight software 2024 to simulate the injection molding process of a discontinuous glass fiber-reinforced polypropylene composite car fender. The effects of various process parameters, particularly the gate location, on the part properties (such as the fiber orientation, volumetric shrinkage, and shear rate) were investigated. Several injection molding process configurations, including three, four, and five gates at varying locations, were created and simulated. The number and locations of gates were optimized using a multicriteria decision-making technique. Based on the optimal performance (i.e., low shrinkage, a consistent fiber orientation, and a controllable shear rate), the optimal configuration was determined, i.e., four gates at appropriate locations (corresponding to the second set of gate locations), with volumetric shrinkage of , a fiber orientation tensor of 0.927 ± 0.011, and a stable shear rate < 74,324 (1/s). The simulation results clearly demonstrate that the gate location is crucial for material behavior during molding and for reducing common defects. The simulation-based process design for the injection molding of discontinuous fiber-reinforced polymer parts proposed in this paper can improve the production efficiency, reduce the need for trial and error, and improve part quality.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.H., S.F. and F.A.M.; methodology, Z.H., S.F. and F.A.M.; software, F.A.M. and S.F.; formal analysis, S.F. and Z.H.; investigation, S.F. and Z.H.; resources, S.F., F.A.M. and Z.H.; data curation, S.F.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.H. and S.F.; writing—review and editing, Z.H.; visualization, S.F. and Z.H.; supervision, Z.H.; project administration, Z.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the J.J. Lohr College of Engineering and the Mechanical Engineering Department at South Dakota State University, which are gratefully acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FRPCs | Fiber-reinforced polymeric composites |

| CFRPs | Continuous fiber-reinforced polymers |

| DFRPs | Discontinuous fiber-reinforced polymers |

| TOPSIS | Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution |

| MCDM | Multicriteria decision-making |

| RSC | Reduced strain closure |

| DGFRP | Discontinuous glass fiber-reinforced polymer |

| CFD | Computational fluid dynamics |

| FEA | Finite element analysis |

References

- Khan, F.; Hossain, N.; Mim, J.J.; Rahman, S.M.M.; Iqbal, M.J.; Billah, M.; Chowdhury, M.A. Advances of composite materials in automobile applications—A review. J. Eng. Res. 2025, 13, 1001–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajak, D.K.; Wagh, P.H.; Linul, E. Manufacturing technologies of carbon/glass fiber-reinforced polymer composites and their properties: A review. Polymers 2021, 13, 3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duraikkannu, S.L.; Castro-Muñoz, R.; Figoli, A. A review on phase-inversion technique-based polymer microsphere fabrication. Colloid Interface Sci. Commun. 2021, 40, 100329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, M.M.; Alamry, K.A.; Hussein, M.A. Recent advances of fiber-reinforced polymer composites for defense innovations. Results Chem. 2025, 15, 102199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhlke, T.; Henning, F.; Hrymak, A.; Kärger, L.; Weidenmann, K.A.; Wood, J.T. Continuous-Discontinuous Fiber-Reinforced Polymers: An Integrated Engineering Approach; Hanser Publictions: Munich, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Osswald, T.A. Discontinuous Fiber Composites; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/jcs/special_issues/Discontinuous_Fibers (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Osswald, T.A.; Kuhn, C. Discontinuous Fiber Composites, Volume II; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/jcs/special_issues/Discontinuous_Fibers_v2 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Morampudi, P.; Namala, K.K.; Gajjela, Y.K.; Barath, M.; Prudhvi, G. Review on glass fiber reinforced polymer composites. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 43, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathishkumar, T.P.; Satheeshkumar, S.; Naveen, J. Glass fiber-reinforced polymer composites—A review. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2014, 33, 1258–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J. Manufacturing of Fibrous Composites for Engineering Applications; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Fleischer, J.; Teti, R.; Lanza, G.; Mativenga, P.; Möhring, H.-C.; Caggiano, A. Composite materials parts manufacturing. CIRP Ann. 2018, 67, 603–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Xu, H.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Kormakov, S.; Wu, D.; Sun, J. Overview of injection molding technology for processing polymers and their composites. ES Mater. Manuf. 2020, 8, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, Z.; Reiter, M. Design of discontinuous fiber reinforced injection molded polymer matrix composite parts. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2014, 633–634, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maertens, R.; Liebig, W.V.; Weidenmann, K.A.; Elsner, P. Development of an injection molding process for long glass fiber-reinforced phenolic resins. Polymers 2022, 14, 2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budiyantoro, C.; Rochardjo, H.S.B.; Wicaksono, S.E.; Ad, M.A.; Saputra, I.N.; Alif, R. Impact and tensile properties of injection-molded glass fiber reinforced polyamide 6-processing temperature and pressure optimization. Int. J. Technol. 2024, 15, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittemann, F.; Maertens, R.; Kärger, L.; Henning, F. Injection molding simulation of short fiber reinforced thermosets with anisotropic and non-Newtonian flow behavior. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2019, 124, 105476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panduv, P.A.; Sawant, D.A. Experimental evaluation and analysis of glass fiber reinforced composite under mechanical loading by using FEA software. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 2017, 10, 682–685. [Google Scholar]

- Knoll, J.; Heim, H.-P. Analysis of the similarity between injection molding simulations and experiment. Polymers 2024, 16, 1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyata, A.; Nikzad, M.; Vishnubhotla, S.S.; Stehle, J.; Gad, E. A simulation-based approach for assessment of injection moulded part quality made of recycled olefins. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 46, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żurawik, R.; Volke, J.; Zarges, J.-C.; Heim, H.-P. Comparison of real and simulated fiber orientations in injection molded short glass fiber reinforced polyamide by X-ray microtomography. Polymers 2021, 14, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, F.; Suplicz, A.; Kovács, J.G. Development of injection molding simulation algorithms that take into account segregation. Powder Technol. 2021, 389, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, C.; Yavuz, B.O.; Longana, M.L.; Belnoue, J.P.; Ramakrishnan, K.R.; Ward, C.; Hamerton, I. A review on the modeling of aligned discontinuous fibre composites. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z. Biomimetic design and topology optimization of discontinuous carbon fiber-reinforced composite lattice structures. Biomimetics 2023, 8, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Lu, J.; Qiu, R.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, P. Multiscale modeling based failure criterion of injection molded SFPR composites considering skin-core-skin layered microstructure and variable parameters. Compos. Struct. 2022, 286, 115277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kameya, K.; Pgata, H.; Tanohata, N. Simulation-based analysis of weld line strength of glass fiber-reinforced polymer in injection molding. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2024, 64, 852–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.-J.; Su, Z.-M. Optimizing glass fiber molding process design by reverse warping. Materials 2020, 13, 1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaincu, A.; Dan, M.; Ungureanu, V.; Marsavina, L. Numerical investigation on the influence of fiber orientation mapping procedure to the mechanical response of short-fiber reinforced composites using Moldflow, Digimat and Ansys software. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 45, 4304–4309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, R.S.; Reddy, C.R. Design and analysis of an automotive bumper. Int. J. Sci. Res. Sci. Technol. 2020, 7, 114–131. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, H.; Wang, Y.; Yang, D. Study of injection molding process simulation and mold design of automotive back door panel. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2022, 36, 2331–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.M.; Kim, H.M.; Youn, J.R.; Song, Y.S. Injection molding of carbon fiber composite automotive wheel. Fibers Polym. 2019, 20, 2665–2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, S.A.; Hain, J.; Sracic, M.W.; Tewani, H.; Prabhakar, P.; Osswald, T.A. Mechanical response of fiber-filled automotive body panels manufactured with the Ku-Fizz™ Microcellular injection molding process. Polymers 2022, 14, 4916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, H.; Ahmad, Z.; Mazlan, S.A.; Johari, M.A.F.; Siebert, G.; Petru, M.; Koloor, S.S.R. Lightweight glass fiber-reinforced polymer composite for automotive bumper applications: A review. Polymers 2023, 15, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olhan, S.; Khatkar, V.; Behera, B.K. Review: Textile-based natural fiber-reinforced polymeric composites in automotive lightweighting. J. Mater. Sci. 2021, 56, 18867–18910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kugler, S.K.; Dey, A.P.; Saad, S.; Cruz, C.; Kech, A.; Osswald, T. A flow-dependent fiber orientation model. J. Compos. Sci. 2020, 4, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oubellaouch, K.; Pelaccia, R.; Bonato, N.; Bettoni, N.; Carmignato, S.; Orazi, L.; Donati, L.; Regginani, B. Assessment of fiber orientation models predictability by comparison with X-ray µCT data in injection-molded short glass fiber-reinforced polyamide. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 130, 4479–4492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivan, R.; Sorgato, M.; Zanini, F.; Lucchetta, G. Improving numerical modeling accuracy for fiber orientation and mechanical properties of injection molded glass fiber reinforced thermoplastics. Materials 2022, 15, 4720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folgar, F.; Tucker, C.L. Orientation behavior of fibers in concentrated suspensions. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 1984, 3, 98–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egelmeers, T.R.N.; Cardinaels, R.; Anderson, P.D.; Jaensson, N.O. Direct numerical simulation of fiber orientation kinetics and rheology of fiber-filled polymers in shear flow. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2025, 268, 111197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, H.-S.; Khoo, B.C.; Phan-Thien, N.; Yeo, K.S.; Zheng, R. Simulations of fibre orientation in dilute suspensions with front moving using level set method. Rheol. Acta 2007, 46, 427–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Phan-Thien, N.; Fan, X.-J.; Tanner, R.I.; Zheng, R. Folgar Tucker constant for a fibre suspension in a Newtonian fluid. J. Non-Newton. Fluid Mech. 2002, 103, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittemann, F.; Maertens, R.; Bernath, A.; Hohberg, M.; Kärger, L.; Henning, F. Simulation of reinforced reactive injection molding with the finite volume method. J. Compos. Sci. 2018, 2, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autodesk Insight Help. Suspension Balance Model—Moldflow Insight 2025. Available online: https://help.autodesk.com/view/MFIA/2025/ENU/?guid=MFLO_SUSPENSION_BALANCE_MODEL (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Autodesk Insight Help. Reduced Strain Closure Model—Moldflow Insight 2025. Available online: https://help.autodesk.com/view/MFIA/2025/ENU/?guid=MFLO_REDUCED_STRAIN_CLOSURE_MODEL (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Wang, J.; O’Gara, J.F.; Tucker III, C.L. An objective model for slow orientation dynamics in concentrated fiber suspensions: Theory and rheological evidence. J. Rheol. 2008, 52, 1179–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autodesk Insight Help. Moldflow Second Order Viscosity Model—Moldflow Insight 2024. Available online: https://help.autodesk.com/view/MFIA/2025/ENU/?guid=MFLO_MOLDFLOW_SECOND_ORDER_VISCOSITY_MODEL (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Autodesk Insight Help. 3D Flow Derivation—Moldflow Insight 2025. Available online: https://help.autodesk.com/view/MFIA/2024/ENU/?guid=MoldflowInsight_CLC_Analyses_analysis_sequences_Pack_analysis_3D_flow_derivation_html (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Perin, M.; Berti, G.A.; Lee, T.; Quagliato, L. Gate design algorithm to maximize the fiber orientation effectiveness in thermoplastic injection-molded components. Mater. Res. Proc. 2023, 28, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autodesk Insight Help. Boundary Element Method Derivation—Moldflow Insight 2024. Available online: https://help.autodesk.com/view/MFIA/2024/ENU/?guid=MoldflowInsight_CLC_Analyses_analysis_sequences_Cool_analysis_products_Cool_analysis_for_part_Boundary_element_method_html (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Uzun, B.; Taiwo, M.; Syidanova, A.; Uzun Ozsahin, D. The Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS). In Application of Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis in Environmental and Civil Engineering; Uzun Ozsahin, D., Gökçekuş, H., Uzun, B., LaMoreaux, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Wang, T.; Jiang, H.; Yu, Y.; Miao, D. A TOPSIS method based on sequential three-way decision. Appl. Intell. 2023, 53, 30661–30676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autodesk Insight Help. Process Optimization Analysis—Moldflow Insight 2024. Available online: https://help.autodesk.com/view/MFIA/2024/ENU/?guid=MoldflowInsight_CLC_Analyses_analysis_sequences_Process_Optimization_analysis_html (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Autodesk Insight Help. Gate Location Analysis—Moldflow Insight 2024. Available online: https://help.autodesk.com/view/MFIA/2024/ENU/?guid=MoldflowInsight_CLC_Analyses_analysis_sequences_Gate_Location_analysis_html (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Gaspar-Cunha, A.; Melo, J.; Marques, T.; Pontes, A. A review on injection molding: Conformal cooling channels, modelling, surrogate models and multi-objective optimization. Polymers 2025, 17, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autodesk Insight Help. PP Materials—Moldflow Insight 2025. Available online: https://help.autodesk.com/view/MFIA/2025/ENU/?guid=MFLO_PP_MATERIALS (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Park, H.S.; Nguyen, T.T. Optimization of injection molding process for car fender in consideration of energy efficiency and product quality. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2014, 1, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).