Abstract

This study systematically investigates the tensile property degradation of Carbon Fabric-Reinforced Cementitious Matrix (CFRCM) composites under anodic polarization, explicitly comparing the effects of three standard-required electrolyte environments (NACE/ISO). CFRCM specimens were polarized for 20 days at current densities of 200 and 400 mA/m2 in NaCl, NaOH, and simulated concrete pore solutions. Results reveal that anodic polarization significantly reduces peak tensile strength and post-cracking stiffness, with degradation severity dependent on the electrolyte type (NaCl > NaOH > Pore Solution). Crucially, comparative analysis demonstrates that the strength degradation of carbon fiber bundles embedded in the mortar matrix is more pronounced than that of bare bundles. This work provides essential durability data for CFRCM composites for integrated ICCP-Structural Strengthening systems.

1. Introduction

Steel corrosion is recognized as a critical issue threatening the durability and safety of reinforced concrete structures. Corrosion not only leads to reduction in the effective cross-sectional area of the steel reinforcement but, more critically, the volumetric expansion of its products (which can reach 2–6 times the original volume) can induce cracking and spalling of the concrete cover, severely compromising structural capacity [1]. Although traditional strengthening techniques, such as bonding Fiber Reinforced Polymer (FRP), can improve short-term load-bearing capacity [2,3,4,5], they are unable to halt the ongoing corrosion process of steel. For preventing corrosion, Impressed Current Cathodic Protection (ICCP) is widely employed as a reliable long-term protection technology [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. It operates by impressing an external current to maintain the steel reinforcement in a stable cathodic state, effectively suppressing its electrochemical corrosion.

To simultaneously achieve long-term anti-corrosion and structural strengthening, an innovative concept integrating these two functions has been proposed, namely ICCP-Structural Strengthening (ICCP-SS) [14,15,16]. The key advantage of this integrated technique lies in its ability to provide immediate enhancement of load-bearing capacity while also delivering continuous cathodic protection, which is expected to significantly extend the service life of structures and reduce life-cycle costs. The realization of this technique relies on the development of dual-functional materials which serve as structural strengthening elements and impressed current anodes. Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polymer (CFRP) was utilized as a dual-functional material in the early research [17,18,19,20,21,22]. However, its polymeric resin matrix is susceptible to anodic polarization-induced degradation, and its inherent low electrical conductivity hinders uniform current distribution, limiting the reliability of long-term application.

To address the issues associated with the polymer matrix, Carbon Fabric Reinforced Cementitious Matrix (CFRCM) composites (also termed textile reinforced concrete/mortar), which utilize cementitious materials to replace the resin, have emerged. The cementitious matrix offers excellent compatibility with the concrete substrate and superior performance to FRP under thermal exposure, though the mechanical behavior of FRCM can be compromised under elevated temperatures [23,24,25,26].

Extensive research has been conducted to investigate the mechanical properties of CFRCM composites at the material level and their strengthening effectiveness at the member level [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. Materially, CFRCM exhibits typical tensile strain-hardening behavior and multiple cracking under tensile load, and its mechanical constitutive relationship has been well characterized. At the structural member level, studies have confirmed that CFRCM can be effectively used to strengthen beams [28,33,35,36,37] and columns [38,39,40,41,42].

Nevertheless, when CFRCM composite serves as an anode in an ICCP system subjected to long-term anodic polarization, its durability concerns become prominent. The anodic polarization process may induce electrochemical oxidation of the carbon fibers themselves [43,44,45,46,47,48], acidification of the cementitious matrix [49,50,51,52], and damage at the fiber-matrix interface [43,53,54], leading to the degradation of the mechanical properties of CFRCM composites. Research indicates that with increasing charge density (the product of current density and time), the tensile peak strength and the modulus representing post-cracking stiffness of CFRCM show significant deterioration [55,56,57,58]. Microscopic observations have further revealed signs of degradation on the carbon fiber surface after polarization [43,46,47,48].

It is noteworthy that for ensuring reliability in engineering applications, relevant technical standards (NACE TM0294-2016 [59] and ISO 19097-1:2018 [60]) explicitly require that impressed current anodes for concrete structures must undergo long-term polarization tests in different electrolyte solutions (such as chloride-containing solutions, alkaline solutions, and simulated concrete pore solutions) to assess their durability. However, there is still a lack of systematic research investigating the evolution in the mechanical properties of CFRCM composites after being subjected to anodic polarization in the aforementioned environments.

This study aims to reveal the tensile mechanical properties of CFRCM after anodic polarization in three typical environments: NaCl, NaOH, and simulated pore solution. Through tensile tests on polarized specimens, the failure modes, crack propagation, load versus deformation curves, and stress–strain constitutive relationships were analyzed. Mechanical parameters sensitive to anodic polarization were extracted. Furthermore, by comparing the strength degradation of CFRCM with that of bare carbon fiber bundles, the exacerbating effect of non-uniform degradation caused by the mortar matrix on the fiber degradation process was elucidated. This work provides a critical basis for the durability design and assessment of CFRCM composites in integrated ICCP-SS systems.

2. Materials and Methods

This investigation was designed to reveal the tensile mechanical properties of CFRCM composites after being subjected to anodic polarization in different electrolyte solutions, with a focus on analyzing the failure mode, crack characteristics, peak strength, and stress–strain constitutive relationship during tension. The main work included specimen preparation, anodic polarization testing, and tensile testing.

2.1. Raw Materials and Specimen Preparation

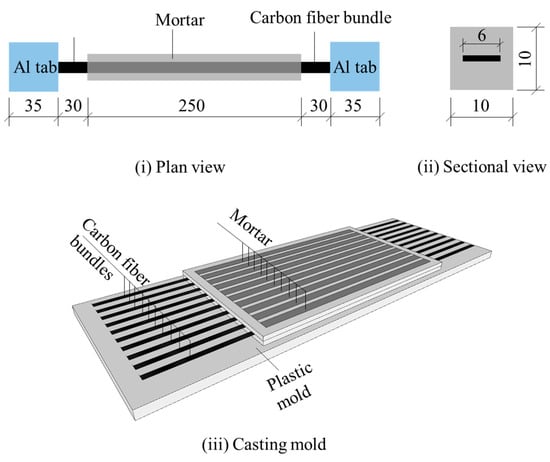

CFRCM composites were composed of carbon fiber fabric and mortar matrix. To exclude the influence of the fiber bundle nodes in a bidirectional fabric, the composite used in this study contained only a single longitudinal carbon fiber bundle, and its geometrical configuration followed that documented in the reference [57]. The specimens had a cross-sectional area of 10 mm × 10 mm and a length of 250 mm, with the carbon fiber bundle positioned centrally along the specimen axis (as shown in Figure 1). The carbon fiber bundle was sourced from untwisted continuous fiber roving, with a width of 3 mm. Each bundle contained 12,000 filaments, with the filament diameter being 7 μm. The elastic modulus and tensile strength of the carbon fiber bundle were 230 GPa and 2300 MPa, respectively.

Figure 1.

Geometrical details and casting mold for CFRCM composites (unit: mm).

The mortar matrix was prepared using PO 42.5 ordinary Portland cement with a water-to-cement ratio of 0.35. Fine sand with a particle size range of 0–0.18 mm was used as fine aggregate, accounting for 50% of the cement mass. To improve workability, a polycarboxylate superplasticizer, amounting to 0.055% of the cement mass, was added during mixing.

The CFRCM composite specimens were cast using customized plastic molds. Each mold could produce 10 specimens simultaneously (Figure 1). After casting, the molds were immediately sealed with plastic wrap to prevent rapid moisture evaporation which would affect cement hydration. After 24 h, the plastic wrap was removed, and the entire mold containing the CFRCM specimens was transferred to a standard curing room for curing. Besides serving as a mold, this setup also functioned as the electrolytic cell for the anodic polarization device, used to contain the electrolyte solution.

2.2. Implementation of Anodic Polarization

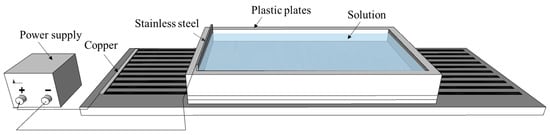

A simulated ICCP setup was used for the galvanostatic anodic polarization tests on CFRCM composites. This setup included the anode (CFRCM composite), the cathode (stainless steel plate), the electrolyte solution, the electrical circuit, and a DC power supply (constant current output), as illustrated in Figure 2. To ensure good electrical connectivity, the exposed carbon fiber ends of the CFRCM composite specimen were reliably connected to copper wires using conductive silver paste before being connected to the positive terminal of the power supply. The cathode (stainless steel plate) was connected to the negative terminal.

Figure 2.

Anodic polarization setup.

Three types of electrolyte solutions were selected based on NACE and ISO standards [59,60]: a 30 g/L NaCl solution, a 40 g/L NaOH solution, and a simulated concrete pore solution (SCP, concentration in weight: 0.20% Ca(OH)2, 3.20% KCl, 1.00% KOH, 2.45% NaOH and 93.15% deionized water), to analyze the effects of different solution environments. Each polarization cell contained ~900 mL of electrolytes which were refreshed twice during polarization. The polarization duration for all specimens was set at 20 days. The anodic current density (relative to the surface area of the carbon fiber bundle) was set at 200 mA/m2 and 400 mA/m2. The polarization was conducted indoors with the electrolyte temperature controlled at around 26 °C throughout polarization to prevent significant thermal variations.

The specimens were labeled according to the following convention: Polarization duration (D followed by number of days)-Current density (I followed by current density value)-Solution environment (denoted by letters A, B, C, where A represents 30 g/L NaCl solution, B represents 40 g/L NaOH solution, and C represents the simulated pore solution). For instance, D20-I200-A denotes a specimen polarized in 30 g/L NaCl solution at a current density of 200 mA/m2 for 20 days. The non-polarized control group specimens were labeled as Ref.

2.3. Tensile Tests

After the polarization period, the CFRCM specimens were removed from the molds and allowed to dry under ambient laboratory conditions. Both ends of the CFRCM composite tensile specimens were reinforced with aluminum alloy plates to prevent slippage of the carbon fiber bundle from the grips during testing. Gripping CF bundles in tension enabled CFRCM specimens to fail by bundle fracture, allowing for comparative assessment of mechanical properties with bare bundles. Note that this gripping method differs from standard characterization tests (e.g., ACI 549.4R [61] or RILEM TC 232-TDT [62]) where the load is transferred through the matrix. While standard methods are preferable for determining design properties, gripping the fiber bundles directly was necessary in this study to ensure fiber rupture, thereby allowing for a direct quantification of the degradation of carbon fiber bundles within the matrix.

The tensile tests were conducted on a universal testing machine with a 10 kN load cell, as shown in Figure 3. The tests were displacement-controlled, with a loading rate of 2 mm/min. The load applied to the specimen was measured by the machine’s built-in load cell. After excluding machine compliance following toe compensation (ASTM D638 [63]), the tensile deformation was calculated by deducting the elastic deformation of the exposed fiber bundle from the total machine crosshead displacement. Both load and deformation data were synchronously recorded by a data acquisition system.

Figure 3.

Tensile tests for CFRCM composite specimens.

3. Results

3.1. Failure Modes

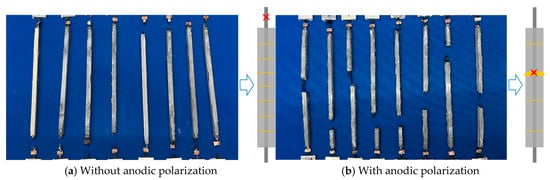

After tensile testing, the CFRCM specimens primarily exhibited two failure modes, as shown in Figure 4. The control specimens (Ref) showed multiple cracking in the mortar matrix during tension. At the peak load, failure occurred due to the rupture of the exposed carbon fiber bundle outside the mortar matrix, as shown in Figure 4a. After anodic polarization, the specimens still developed multiple cracks in the mortar matrix during tension, but the average crack spacing was noticeably increased. At the peak load, the location of the carbon fiber bundle rupture shifted to within a mortar crack (Figure 4b). This indicates that the anodic polarization process may have caused degradation at the carbon fiber-mortar interface or within the carbon fibers themselves, thereby changing the failure location of the specimens.

Figure 4.

Failure patterns for CFRCM composites without (a) and with (b) anodic polarization.

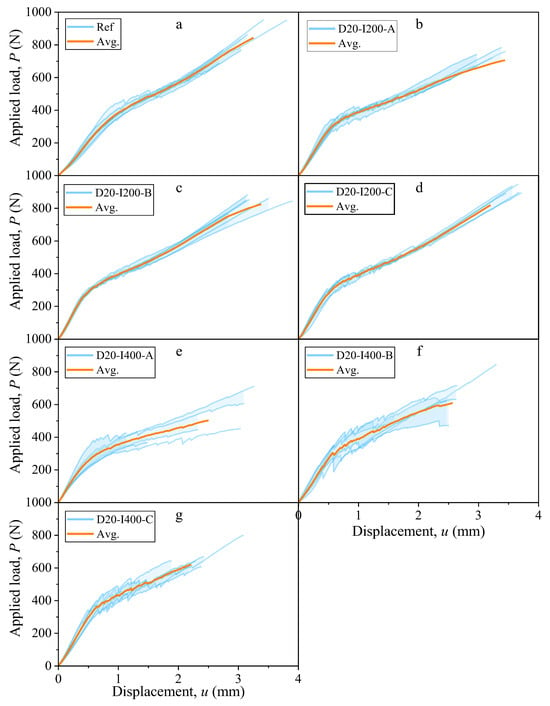

3.2. Load–Displacement Curves

The typical load–displacement curves of the CFRCM composite specimens are depicted in Figure 5. All specimens exhibited characteristic strain-hardening behavior. Their mechanical response can be divided into three stages: the initial linear-elastic uncracked stage, the multiple cracking stage, and the crack-widening stage. In the initial stage, the load and deformation showed a linear relationship, as the stress was primarily carried by the mortar matrix. Once the load reached the tensile strength of the mortar, matrix cracking initiated, leading to a reduction in the slope of the curve accompanied by fluctuations, marking the beginning of the multiple cracking stage where the number of cracks increased and the crack spacing decreased. This was followed by the crack-widening stage, where the curve ascended approximately linearly, but with a slope lower than the initial elastic stage, until the rupture of the carbon fiber bundle resulted in final failure. Anodic polarization significantly affected the mechanical behavior of the specimens in the crack-widening stage, manifesting as a decrease in the slope of the curve in this stage and a reduction in the peak load. This phenomenon can be attributed to the degradation of the carbon fibers themselves and the fiber-matrix interface induced by anodic polarization [43,46,48].

Figure 5.

Applied load versus displacement curves.

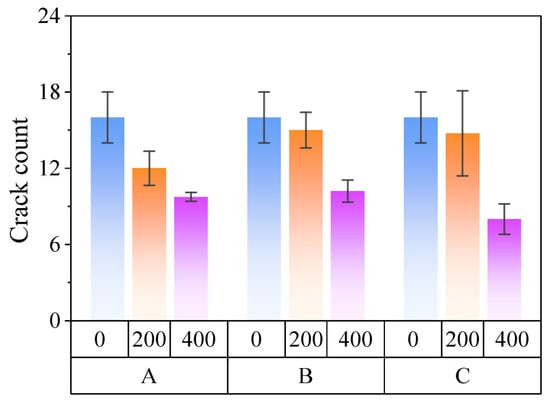

3.3. The Number of Cracks Within Mortar

The number of cracks on the surface of the CFRCM specimens after tensile testing was counted. The average values and standard deviations for each polarization condition were calculated. The average crack numbers for the CFRCM specimens are plotted in Figure 6. Compared to the control group (average number of 16), the number of cracks in the anodically polarized specimens decreased with increasing current density and was influenced by the type of electrolyte solution. After 20 days of polarization at 400 mA/m2, the average number of cracks decreased to 9.75, 10.2, and 8 for specimens polarized in solutions A, B, and C, respectively.

Figure 6.

The number of cracks in the CFRCM composite matrix.

The reduction in the number of cracks confirms the degradation effect induced by anodic polarization. The mechanism of crack spacing formation is related to stress transfer: a crack forms when the stress in the mortar reaches its tensile strength, transferring the load at the crack to the carbon fiber bundle. Through the interfacial bond stress between the fiber bundle and the matrix, the load is gradually transferred back to the mortar matrix until the stress in the mortar reaches its tensile strength again at a sufficient distance, forming a new crack. Anodic polarization weakens the interfacial bond strength, leading to an increase in the required bond transfer length (half the crack spacing) to complete the stress transfer, consequently resulting in a reduced number of cracks in the specimen.

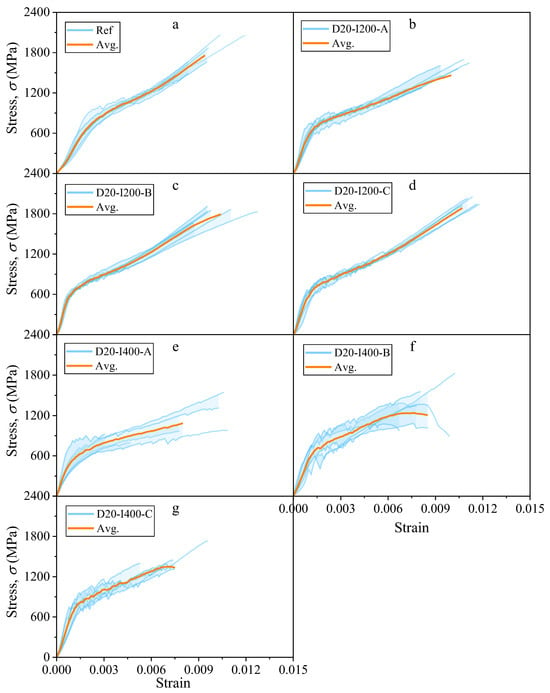

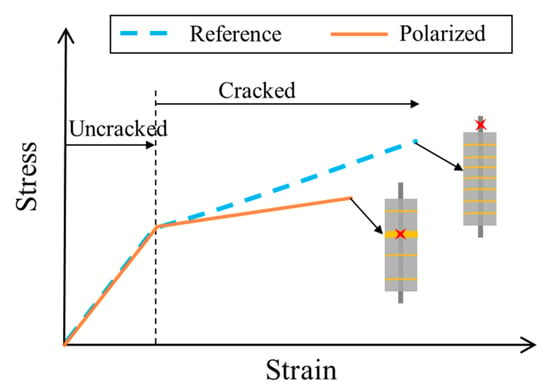

3.4. Tensile Stress–Strain Constitutive Relationship

The tensile stress in the CFRCM composite was calculated by dividing the applied load by the cross-sectional area of the carbon fiber bundle. The average strain was determined by dividing the tensile deformation of the specimen by its gauge length. The established tensile stress–strain constitutive relationship for CFRCM is shown in Figure 7, sharing a similar shape with the load–displacement curves. Given the relatively brief duration of the multiple cracking stage, the constitutive relationship can be simplified into a bilinear model, comprising the elastic uncracked stage and the post-cracking stage. The effect of anodic polarization was primarily reflected in the changes in the modulus of the post-cracking stage and the peak strength, as illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 7.

Tensile stress versus strain curves.

Figure 8.

Tensile stress versus strain curves for CFRCM composites with and without anodic polarization.

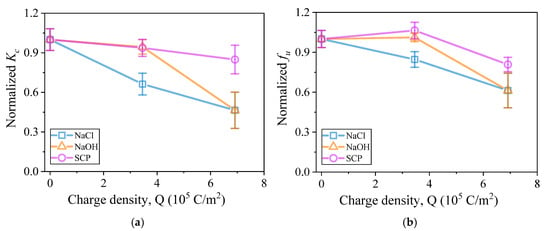

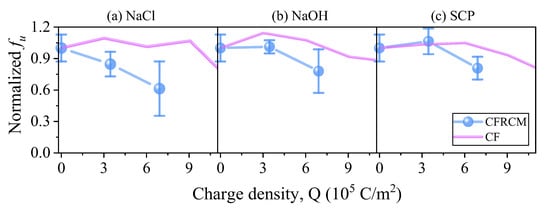

To quantify the effect of anodic polarization, the elastic modulus (slope of the curve) in the post-cracking stage and the peak strength of the polarized specimens were normalized against the corresponding values of the control specimens. Charge density (the product of current density and time) was introduced as a comprehensive indicator of the polarization level. The relationship between the normalized mechanical properties and the charge density is shown in Figure 9. At a charge density of 691,200 C/m2, the modulus in the post-cracking stage decreased by 54.5%, 26.8%, and 15.1% for specimens polarized in solution A (NaCl), B (NaOH), and C (SCP), respectively. Correspondingly, the peak tensile strength was reduced by 38.7%, 22.0%, and 19.2%. This indicates that the NaCl solution environment had the most significant degrading effect on the mechanical properties of CFRCM, while the effects in the NaOH and simulated pore solutions were relatively weaker.

Figure 9.

Effects of anodic polarization on mechanical properties of CFRCM composites: (a) Elastic modulus at the cracked stage; (b) Tensile strength.

3.5. Comparison of Tensile Strength: Bare Carbon Fiber Bundles vs. CFRCM-Embedded Bundles

Since all CFRCM specimens ultimately failed due to the rupture of the carbon fiber bundle, their tensile strength directly reflects the residual strength of the fiber bundle. Figure 10 compares the normalized tensile strength of bare carbon fiber bundles and the bundles embedded within CFRCM composites after polarization under various conditions. The results demonstrate that for any given electrolyte solution, the degree of strength degradation of the carbon fiber bundles within the CFRCM composite specimens was more severe than that of the bare carbon fiber bundles. A plausible explanation is that within the CFRCM, the distribution of current within the carbon fiber bundle, composed of tens of thousands of filaments, may become non-uniform due to the presence of the mortar matrix. This non-uniformity could lead to localized areas of high current density, thereby exacerbating the non-uniform degradation of the fiber bundle. Consequently, the non-uniform polarization effect induced by the mortar matrix must be considered when evaluating the impact of anodic polarization on the overall performance of CFRCM composites.

Figure 10.

Comparisons in normalized tensile strength between bare carbon fiber bundles and CFRCM composites subjected to anodic polarization.

4. Conclusions

Based on the tensile tests conducted on carbon fabric-reinforced cementitious matrix composites subjected to anodic polarization in different electrolyte solutions, the following main conclusions were drawn:

- (1)

- The anodic polarization treatment altered the tensile failure mode of the CFRCM specimens. In the non-polarized control specimens, the rupture of the exposed carbon fiber bundle occurred outside the mortar matrix. In contrast, after anodic polarization, the rupture of the carbon fiber bundle consistently occurred within a crack inside the mortar matrix. This indicates that the anodic polarization process caused degradation at the carbon fiber-mortar interface and within the carbon fibers themselves, prompting a shift in the location of fiber rupture.

- (2)

- Compared to the control group, the polarized specimens exhibited a reduced number of cracks and an increased average crack spacing. This confirms that anodic polarization weakened the interfacial bond strength between the fibers and the mortar matrix.

- (3)

- All specimens exhibited typical strain-hardening behavior. However, the slope of the load-deformation curve in the crack-widening stage was noticeably reduced after anodic polarization. This indicates that anodic polarization not only reduced the peak strength of the material but also impaired its stiffness during the primary service stage (post-cracking stage).

- (4)

- The degrading effect of anodic polarization on the post-cracking modulus and peak strength of CFRCM composites was positively correlated with the charge density (the product of current density and polarization time) and was significantly modulated by the type of electrolyte solution. At a charge density of 691,200 C/m2, the property degradation was most pronounced in the NaCl solution (A: 54.5% reduction in modulus, 38.7% reduction in strength), while it was least significant in the simulated pore solution (C: 15.1% reduction in modulus, 19.2% reduction in strength).

- (5)

- Comparison with bare carbon fiber bundles directly exposed to the solutions revealed that the strength degradation of the bundles embedded within CFRCM composites was more severe. This highlights a critical issue caused by the mortar matrix: non-uniform current distribution. This non-uniformity induces more significant localized damage, thereby exacerbating the overall degradation of mechanical performance. Therefore, the non-uniform polarization effect resulting from the matrix must be considered in the durability assessment of CFRCM composite for long-term applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Z. and C.Z.; methodology, Y.Z.; software, J.D.; validation, M.Z., J.D. and C.Z.; formal analysis, H.C.; investigation, Y.Z. and H.C.; resources, J.D.; data curation, M.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Z.; writing—review and editing, C.Z.; visualization, M.Z.; supervision, J.D. and C.Z.; project administration, M.Z.; funding acquisition, M.Z. and C.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52208277 and 52208308).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. This study did not involve humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. This study did not involve humans or animals.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Broomfield, J.P. Corrosion of Steel in Concrete; CRC Press: London, UK, 2022; ISBN 9781003223016. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, L.; Wang, C.; Brühwiler, E.; Wang, Q. Experiments on the Flexural Behavior of Full-Scale PC Box Girders with Service Damage Strengthened by Prestressed CFRP Plates. Compos. Struct. 2023, 312, 116864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotynia, R.; Oller, E.; Marí, A.; Kaszubska, M. Efficiency of Shear Strengthening of RC Beams with Externally Bonded FRP Materials—State-of-the-Art in the Experimental Tests. Compos. Struct. 2021, 267, 113891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Li, Y.; Yuan, H. Review of Experimental Studies on Application of FRP for Strengthening of Bridge Structures. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 2020, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naser, M.Z.; Hawileh, R.A.; Abdalla, J.A. Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites in Strengthening Reinforced Concrete Structures: A Critical Review. Eng. Struct. 2019, 198, 109542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, A.; Norton, B.; Holmes, N. State-of-the-Art Review of Cathodic Protection for Reinforced Concrete Structures. Mag. Concr. Res. 2016, 68, 664–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolini, L.; Pedeferri, P.; Redaelli, E.; Pastore, T. Repassivation of Steel in Carbonated Concrete Induced by Cathodic Protection. Mater. Corros. 2003, 54, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, S. Effectiveness of Impressed Current Cathodic Protection in Concrete Following Current Interruption. Master’s Thesis, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Polder, R.; Peelen, W. Cathodic Protection of Steel in Concrete—Experience and Overview of 30 Years Application. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 199, 01002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheaitani, A. Review of Cathodic Protection Systems for Concrete Structures in Australia. In Proceedings of the CORROSION 2017, New Orleans, LA, USA, 26–30 March 2017; pp. 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Pedeferri, P. Cathodic Protection and Cathodic Prevention. Constr. Build. Mater. 1996, 10, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mietz, J.; Fischer, J.; Isecke, B. Cathodic Protection of Steel-Reinforced Concrete Structures—Results from 15 Years’ Experience. Mater. Perform. 2001, 40, 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Polder, R.B.; Peelen, W.H.A. Service Life Aspects of Cathodic Protection of Concrete Structures; Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Su, M.-N.; Huang, J.; Ueda, T.; Xing, F. The ICCP-SS Technique for Retrofitting Reinforced Concrete Compressive Members Subjected to Corrosion. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 167, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.; Liang, H.; Wei, L.; Ueda, T.; Xing, F.; Zhu, J.; Zeng, Z.W. Experimental Investigation on the ICCP-SS Technique for Sea-Sand RC Beams. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Durability of Concrete Structures, Leeds, UK, 18–20 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Su, M.; Wei, L.; Zeng, Z.; Ueda, T.; Xing, F.; Zhu, J.-H. A Solution for Sea-Sand Reinforced Concrete Beams. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 204, 586–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Wei, L.; Zhu, M.; Han, N.; Zhu, J.; Xing, F. Corrosion Behavior of Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polymer Anode in Simulated Impressed Current Cathodic Protection System with 3% NaCl Solution. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 112, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Guo, G.; Wei, L.; Zhu, M.; Chen, X. Dual Function Behavior of Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polymer in Simulated Pore Solution. Materials 2016, 9, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.-H.; Wei, L.; Moahmoud, H.; Redaelli, E.; Xing, F.; Bertolini, L. Investigation on CFRP as Dual-Functional Material in Chloride-Contaminated Solutions. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 151, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Wei, L.; Zhu, M.; Sun, H.; Tang, L.; Xing, F. Polarization Induced Deterioration of Reinforced Concrete with CFRP Anode. Materials 2015, 8, 4316–4331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Zhu, J.-H.; Dong, Z.; Liu, J.; Liu, W.; Su, M.; Xing, F. Anodic and Mechanical Behavior of Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polymer as a Dual-Functional Material in Chloride-Contaminated Concrete. Materials 2020, 13, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Memon, S.A.; Gu, Y.; Zhu, M.; Zhu, J.; Xing, F. Degradation of Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polymer from Cathodic Protection Process on Exposure to NaOH and Simulated Pore Water Solutions. Mater. Struct. 2016, 49, 5273–5283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzuca, P.; Ombres, L.; Guglielmi, M.; Verre, S. Residual Mechanical Properties of PBO FRCM Composites after Elevated Temperature Exposure: Experimental and Comparative Analysis. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2023, 35, 04023383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzuca, P.; Micieli, A.; Campolongo, F.; Ombres, L. Influence of Thermal Exposure Scenarios on the Residual Mechanical Properties of a Cement-Based Composite System. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 466, 140304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ombres, L.; Mazzuca, P.; Micieli, A.; Candamano, S.; Campolongo, F. FRCM–Masonry Joints at High Temperature: Residual Bond Capacity. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2025, 37, 04025012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghari, H.; Omeman, Z.; Noel, M.; Hajiloo, H. Tensile Properties of Carbon Fabric-Reinforced Cementitious Matrix (FRCM) at High Temperatures. Structures 2023, 55, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raoof, S.M.; Koutas, L.N.; Bournas, D.A. Bond between Textile-Reinforced Mortar (TRM) and Concrete Substrates: Experimental Investigation. Compos. Part B 2016, 98, 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bencardino, F.; Carloni, C.; Condello, A.; Focacci, F.; Napoli, A.; Realfonzo, R. Flexural Behaviour of RC Members Strengthened with FRCM: State-of-the-Art and Predictive Formulas. Compos. Part B 2018, 148, 132–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, A.; Ebead, U. Bond Characteristics of Different FRCM Systems. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 175, 610–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Antino, T.; Papanicolaou, C. Mechanical Characterization of Textile Reinforced Inorganic-Matrix Composites. Compos. Part B Eng. 2017, 127, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arboleda, D. Fabric Reinforced Cementitious Matrix (FRCM) Composites for Infrastructure Strengthening and Rehabilitation: Characterization Methods. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Miami, Coral Gables, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Lami, K.; D’Antino, T.; Colombi, P. Durability of Fabric-Reinforced Cementitious Matrix (FRCM) Composites: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshvar, K.; Moradi, M.J.; Roshan, N.; Noel, M.; Hajiloo, H. Enhancing Flexural and Shear Capacities of RC T-Beams with FRCM Incorporating a Full FRCM-Concrete Bond. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 471, 140687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irandegani, M.A.; Zhang, D.; Shadabfar, M.; Kontoni, D.P.N.; Iqbal, M. Failure Modes of RC Structural Elements and Masonry Members Retrofitted with Fabric-Reinforced Cementitious Matrix (FRCM) System: A Review. Buildings 2022, 12, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Figueredo, G.P.; Gordon, G.S.D.; Thermou, G.E. Data-Driven Shear Strength Prediction of RC Beams Strengthened with FRCM Jackets Using Machine Learning Approach. Eng. Struct. 2025, 325, 119485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, J.; Dou, G.; Bi, X.; Zhu, J.; Yu, Z. Experimental Study on the Flexural Fatigue Performance of TRC-Strengthened Corroded RC Beams. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 110, 113065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolli, V.; Sneed, L.H.; Focacci, F.; D’Antino, T. Shear Strengthening of RC Beams with U-Wrapped FRCM Composites: State of the Art and Assessment of Available Analytical Models. J. Compos. Constr. 2025, 29, 04024091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.-H.; Wang, Z.; Su, M.; Ueda, T.; Xing, F. C-FRCM Jacket Confinement for RC Columns under Impressed Current Cathodic Protection. J. Compos. Constr. 2020, 24, 4020001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnassar, Z.; Abed, F.; Refai, A.E.; El-Maaddawy, T. FRCM Confinement of Concrete Columns: A Review of Strength and Ductility Enhancements. Compos. Struct. 2025, 370, 119389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawdhari, A.; Adheem, A.H.; Kadhim, M.M.A. Parametric 3D Finite Element Analysis of FRCM-Confined RC Columns under Eccentric Loading. Eng. Struct. 2020, 212, 110504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Arora, H.C.; Chidambaram, R.S.; Kumar, A. Prediction of Confined Compressive Strength of Concrete Column Strengthened with FRCM Composites. Struct. Concr. 2025, 26, 879–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faleschini, F.; Zanini, M.A.; Hofer, L.; Pellegrino, C. Experimental Behavior of Reinforced Concrete Columns Confined with Carbon-FRCM Composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 243, 118296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Zhu, J.; Ueda, T.; Matsumoto, K. Degradation Behavior of Multifunctional Carbon Fabric-Reinforced Cementitious Matrix Composites under Anodic Polarization. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 341, 127751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, C.; Song, G.; Zheng, D.; Guo, Y.; Huang, X. Electrochemical Activity and Damage of Single Carbon Fiber. Materials 2021, 14, 1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Lu, Y.; Yang, C. Stripping Mechanism of PAN-Based Carbon Fiber during Anodic Oxidation in NaOH Electrolyte. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 486, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.-H.; Li, Q.; Pei, C.; Yu, H.; Xing, F. Evolution Mechanism of Carbon Fiber Anode Properties for Functionalized Applications: Impressed Current Cathodic Protection and Structural Strengthening. Engineering 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, C.; Yu, H.; Zhu, J.; Xing, F. Efficient Multifunctional Modification of Commercial Carbon Fiber Through Tailored Carbon Layer Structure. Engineering 2024, 55, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Li, Q.; Zhu, J.-H.; Xing, F. Anodic Degradation Behaviour of Carbon Fibre in CFRP at High-Chloride and -Alkali Condition. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 417, 135241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.H.; Wu, X.Y.; Mohamed, I.M.A.; Xing, F. Electrochemical and Microstructural Evaluation of Acidification Damage Induced by Impressed Current Cathodic Protection after Incorporating a Hydroxy Activated-Mg/Al-Double Oxide in the External Anode Mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 309, 125116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster, T.; Peelen, W.; Larbi, J.; de Rooij, M.; Polder, R. Numerical Model of Ca(OH)2 Transport in Concrete Due to Electrical Currents. Mater. Corros. 2010, 61, 518–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Hu, J.; Ma, Y.; Huang, H.; Yin, S.; Wei, J.; Yu, Q. The Application of Novel Lightweight Functional Aggregates on the Mitigation of Acidification Damage in the External Anode Mortar during Cathodic Protection for Reinforced Concrete. Corros. Sci. 2020, 165, 108366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Qin, S.; Deng, Z.; Zhu, M. In Situ Monitoring of Anodic Acidification Process Using 3D μ-XCT Method. Materials 2024, 17, 5662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, D.; Xie, Z.; Hong, J. Effect of ICCP on Bond Performance and Piezoresistive Effect of Carbon Fiber Bundles in Cementitious Matrix. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2024, 152, 105645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, J.-H.; Xing, F. Experimental Study on Interface Bonding Fatigue Behavior of C-FRCM Composites in ICCP. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 259, 120655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, J.-H.; Xing, F. Experimental Study on the Behavior of Carbon-Fabric Reinforced Cementitious Matrix Composites in Impressed Current Cathodic Protection. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 264, 120655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.L.; Zhu, J.-H.; Ueda, T.; Su, M.; Liu, J.; Liu, W.; Tang, L.-P.; Xing, F. Tensile Behaviour of Carbon Fabric Reinforced Cementitious Matrix Composites as Both Strengthening and Anode Materials. Compos. Struct. 2020, 234, 111675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, D.; Tao, Y.; Xie, Z.; Yi, B. Effect of ICCP on Tensile Performance and Piezoresistive Effect of CFRCM Plates. Eng. Struct. 2024, 313, 118317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Zheng, Y.; Tian, J.; Shen, H.; Zhu, J. Effects of Hybrid Fibers and Anodic Polarization on Mechanical Performance of Carbon Fabric Reinforced Cementitious Matrix (C-FRCM). Eng. Struct. 2025, 336, 120302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NACE TM0294-2016; Testing of Embeddable Impressed Current Anodes for Use in Cathodic Protection of Atmospherically Exposed Steel-Reinforced Concrete. AMPP: Houston, TX, USA, 2016.

- ISO 19097-1:2018; Accelerated Life Test Method of Mixed Metal Oxide Anodes for Cathodic Protection—Part 1: Application in Concrete. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- ACI 549.4R-13; Guide to Design and Construction of Externally Bonded Fabric-Reinforced Cementitious Matrix (FRCM) Systems for Repair and Strengthening Concrete and Masonry Structures. American Concrete Institute: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2013; p. 69.

- Brameshuber, W. Recommendation of RILEM TC 232-TDT: Test Methods and Design of Textile Reinforced Concrete. Mater. Struct. 2016, 49, 4923–4927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D638-10; Test Method for Tensile Properties of Plastics. ASTM Int.: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2010; pp. 1–16.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.