Abstract

Composite tubes were filament-wound and cured using a vitrimer epoxy resin and carbon fiber (CF). The matrix was dissolved under mild conditions, and recovered continuous fiber tows were used to rewind a second-generation tube. Property retention and microstructural quality were evaluated by mechanical tests and examination of polished sections. The vitrimer–matrix composite exhibited a higher short-beam shear strength compared to specimens wound with a traditional epoxy, typical of hydrogen tanks. Single-fiber testing revealed that CFs were not degraded by the recycling process. The remanufactured composite exhibited mechanical properties comparable to those of the first-generation material when normalized to the fiber volume fraction. This work demonstrates a circular manufacturing process that includes full fiber recovery and re-use for producing a second-generation filament-wound article.

1. Introduction

The sustainability of composites lags far behind conventional structural metals, particularly aluminum and ferrous alloys, which can be recycled repeatedly. Today, composite recycling is virtually non-existent, and down-cycling (once) represents the most sustainable practice of addressing composite waste. The primary reason stems from the irreversible nature of the chemical reactions that occur during the curing of thermoset matrices, making the separation of fibers and matrices difficult. However, the advent of vitrimer matrices, which feature reversible covalent bonds, introduces the possibility of overcoming this difficulty and developing composites that can be recycled. In this work, we present one of the first demonstrations of a method for producing fully recyclable filament-wound composite structures, together with remanufacturing using recovered fibers. The motivation stems from the growing use of composite overwrapped pressure vessels (COPVs) for gas storage, coupled with the expanding applications for hydrogen fuel.

Hydrogen fuel is a major component of current efforts to decarbonize. In 2023, the U.S. National Clean Hydrogen Strategy and Roadmap outlined methods for hydrogen production and use over the coming decades to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 [1]. The expanded use of hydrogen will naturally increase the demand for structures for distribution (pipes) and storage (tanks). Typically, these are filament-wound pipes and COPVs. However, there is no technologically mature process for recycling COPVs, and thus, a need exists for new materials and/or processes.

Filament winding differs from nearly all other methods used to produce composites because a continuous tow is wound onto a mandrel without cutting fibers. As such, filament-wound products contain only continuous tows of fiber without cut ends, thus eliminating a formidable recycling challenge common to other composite manufacturing processes. However, current COPVs for hydrogen storage are typically made from carbon fiber (CF)–epoxy, which makes separation difficult. The tanks feature thick walls (>10 mm), and thus contain large quantities of high-value CFs. At COPV end-of-life (EOL), fibers generally remain continuous and largely undamaged [2]. However, when hydrogen tanks are decommissioned to landfills, the discarded fibers represent lost value. According to the U.S. Department of Energy, 69% of the total cost of hydrogen COPV production is attributed to CFs [3].

Vitrimers contain crosslinked networks similar to thermosets, but consist of covalent adaptable networks (CANs) that can undergo topographical changes via bond exchange reactions when exposed to stimuli [4]. These reactions allow the crosslinks to break and reform with one another, enabling flow when the cured polymer is heated, an attribute previously associated only with thermoplastics. The associative nature of the CAN indicates that bonds only break to form new crosslinks, preserving the crosslink density. Polyimine chemistry has been developed, in which bond exchange occurs between amine and aldehyde groups, allowing for dissolution by disrupting the stoichiometric ratio [5]. Temperatures above the topology-freezing temperature facilitate resin flow through bond exchange reactions, while dissolution occurs when these reactions take place with small molecules in solution, causing the polymer backbone to revert to monomers [6]. This process offers the possibility of full recyclability of the material, as the vitrimer thermoset network can be dissolved and returned to its monomers for re-use. When used as a matrix for COPVs, a dissolvable vitrimer enables the separation and recovery of clean fibers that can be unwound and rewound via reverse filament winding.

Chemical composite recycling methods, such as solvolysis and acid digestion, are difficult to apply to COPVs because the composite overwrap can be over 25 mm thick. Previous work includes the ECOHYDRO project at IMT Nord Europe, focused on a thermoplastic matrix (Elium, Arkema Global) with low viscosity suitable for fiber infiltration during filament winding [7]. Voith Composites prepared a conventional epoxy hydrogen tank, but reportedly recovered 0.5 m lengths of CFs through a pyrolysis method [8], while this method represents an EOL option for COPVs, chopping the long-range fibers reduces the efficacy of further use of the fibers. DEECOM is a CF recovery method that utilizes pressurized steam to remove matrix from the reinforcements and has also been applied to hydrogen tanks [9,10]. This process required high-temperature steam (400 °C), which required significant energy input. These recycling methods rely on shortening the fibers, which limits the applicability of recovered fibers. Additionally, these methods inhibit recovery of the matrix, wasting potentially valuable material.

Few of the cited works demonstrate remanufacturing with recovered CFs, although all claim COPV recyclability. In this work, we demonstrate the recovery of CF tows from a vitrimer matrix and subsequent re-use to demonstrate the manufacture of second-generation parts. The findings demonstrate how the attributes of vitrimer matrices can be leveraged to recycle filament-wound composites, particularly COPVs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Production Methods

Tubular specimens were produced by filament winding for mechanical testing in short-beam shear loading. A control epoxy resin (Epon 826, Westlake, Houston, TX, USA and Jeffamine T-403, Huntsman, The Woodlands, TX, USA). was chosen as the reference material. Two vitrimer formulations were used; A proprietary blend of vitrimer resin (Vitrimax VHM Resin, Mallinda Inc., Denver, CO, USA) was chosen for recyclability for wet filament winding. A vitrimer prepreg (Vitrimax VHM Prepreg, Mallinda Inc.) was hand-spliced to form towpreg, offering control of resin content in the resulting composite. The prepreg was reinforced with unidirectional CFs (HTS40, Tejin, Rockwood, TN, USA). These fibers had a 12K filament count and polyurethane sizing at a 1% loading. For the wet winding processes, the control epoxy resin was mixed with hardener for ten minutes at a ratio of 1:0.45, followed by degassing. The vitrimer resin was prepared by combining a 1.5:1 ratio of imine to epoxy, followed by 2 min of mixing and then 2 min at 90 °C. The heating and mixing cycle was repeated three times until a consistent mix was achieved. CFs (T700S, Toray, Tokyo, Japan) were used as reinforcement to produce the specimens via wet filament winding. These fibers had a 24K filament count and 50C (epoxy, phenolic, polyester, vinyl ester, 1%) sizing. The vitrimer resin system (VHM) was reinforced with fibers recovered from the vitrimer prepreg. A tabular comparison of the fiber properties are shown in A1. A lab-scale filament winder was employed for winding (4-Axis Model 4X-23, X-Winder, El Prado, NM, USA). Minor modifications were made including incorporating poly-tetrafluoroethylene rollers, and a blank resin bath. Two different tubular mandrels were designed, with diameters of 152.4 mm and 31.75 mm, made from aluminum and silicone, respectively. The silicone mandrel was collapsible, allowing for the removal of a tubular part without cutting the fibers, which was advantageous for the recycling process. Following winding, consumables consisting of peel ply (FIBREGLAST Econostitch Peel Ply, FIBREGLAST, Brookville, OH, USA) perforated release film (AIRTECH A4000P3-001-48”, AIRTECH, Huntington Beach, CA, USA), breather (AIRTECH AIRWEAVE-N10-60”, AIRTECH, Huntington Beach, CA, USA), and shrink tape were applied (HI-SHRINK TAPE 100 yards—Release Coated 220 cR 1.5”, Composite Envisions LLC, Wausau, WI, USA). The shrink tape was activated with a heat gun prior to the cure cycle. Additional details of the filament winding process are available in Appendix A Table A2 and Table A3. The control resin cure cycle was 24 h at room temperature and 24 h at 80 °C. Specimens produced with the vitrimer resin and prepreg (VHM) were cured at 135 °C for 40 min, followed by a 5 °C/min ramp to 180 °C, and then held at 180 °C for 6 h. Vitrimer tubes were dissolved in a proprietary aqueous solution with a pH of 1.9, indicating acidic conditions. Two liters of the solution were used at 90 °C to dissolve one two-layer tube of cured composite. The acidic conditions break crosslinks in the vitrimer network, but the short exposure time and mild temperatures leave CFs intact. Specimens for single-fiber testing were removed after 24 h, while full tows of CFs, used for remanufacturing, were submerged in the recycling solution for 2 h. For the second-generation components, 14 small tubes (31.75 mm diameter) were produced via filament winding and dissolved to recover fiber tows. The recovered individual tows were adhered together (Devcon 2 Ton Epoxy) with approximately 10 mm of overlap. These recovered tows were filament-wound with a neat vitrimer resin (Mallinda VHM Resin, Mallinda Inc.) onto a 152.4 mm diameter aluminum tube, following the above methods.

2.2. Characterization

Short-beam shear testing (SBS) of curved specimens cut from tubular samples was performed following ASTM D2344/D2344M-22 (Instron 5667) [11]. Samples were 40 mm by 12 mm cut via water jet cutting and tested at 1 mm/min. Light microscopy of polished sections was used to examine sample microstructure (VHX-7100, Keyence, Osaka, Japan). Machine learning algorithms were employed to measure void content and fiber volume fractions using commercial software (Dragonfly 2024.1), using the images recorded at 150× and 1500× magnification, respectively. Single-fiber testing was based on ISO 11566: 1996(E) [12]. and diameters were measured from light microscope images. 40 specimens of both the virgin and recovered fibers (Tejin, Rockwood, TN, USA) were prepared and tested to determine the effects of the recycling process. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Apreo 2, ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to analyze fibers before and after recycling.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. First-Generation Composites

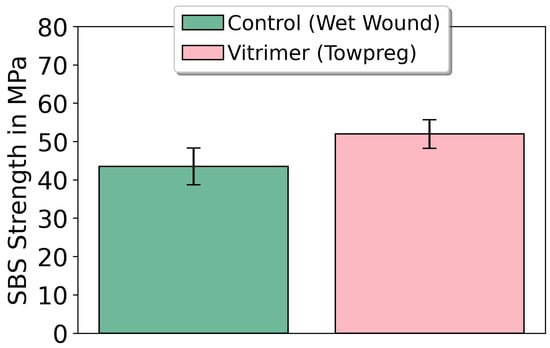

Figure 1 shows tubular SBS data of the epoxy control, wet wound, and vitrimer towpreg specimens. The tested loading condition is more dependent on the fiber–matrix properties compared to longitudinal tensile testing, thus being of interest for COPV applications. Despite a more demanding configuration, the vitrimer towpreg had greater SBS strengths than the wet wound control samples. The increase was found to be highly statistically significant with p < 0.0001. Towpreg materials have more controlled fiber volume fractions because the fibers are impregnated with a specified amount of resin, which is an uncontrolled variable in wet winding [13]. The additional manufacturing steps required to produce towpreg result in increased costs; therefore, a wet-wound specimen was used as a control, representing the typical wet filament winding currently employed to produce COPVs.

Figure 1.

Short-beam shear strength of control specimens prepared via wet winding and vitrimer samples prepared from a towpreg material. Error bars represent standard deviation.

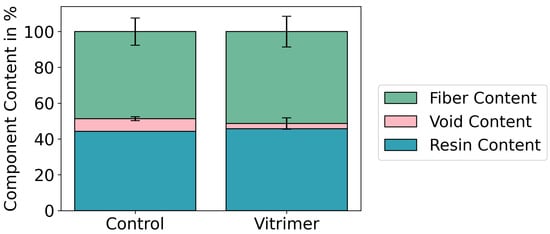

Microscopy and image segmentation revealed differences in void content and fiber volume fraction of the control epoxy and towpreg vitrimer specimens, as shown in Figure 2. The higher void content in the wet wound control specimens was a result of the wet winding process. Previous work has shown that flexural strength can decrease by 5–10% for each 1% increase in void content in carbon fiber–epoxy composites [14]. The lower void content in the vitrimer towpreg material enhances its mechanical performance compared to the control specimens, resulting from superior load transfer between the matrix and fibers. p-values were calculated based on t-tests to determine statistical significance and revealed that the difference in void content was significant (p = 0.0027), while the difference in fiber volume fraction was not (p = 0.4767).

Figure 2.

Contents of composite samples from image analysis. Error bars represent standard deviation.

3.2. Remanufactured Composites

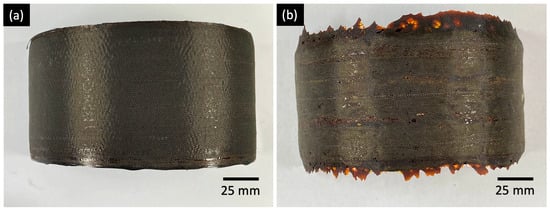

CF tows were recovered from the towpreg vitrimer and rewound to produce a second-generation tube (specimens shown in Figure 3). The rewound sample showed no obvious defects stemming from the recycling process. These images demonstrated that long fiber tows can be recovered and reused in a remanufacturing process.

Figure 3.

(a) Composite tube as manufactured. (b) Remanufactured, second-generation tube.

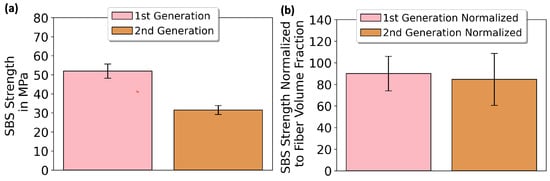

Figure 4a displays the first- and second-generation SBS data, including normalization. The remanufactured tube exhibited lower SBS strength compared to its first-generation counterpart, although this was consistent with the differences between dry and wet winding [14]. The wet winding process introduces additional defects due to the variability in resin infiltration and compaction compared to the uniform consolidation in a prepregging process. To compare similar resin systems produced via different filament winding processes, a method was devised to normalize the SBS strength to the fiber volume fraction. Different methods of this normalization have been reported [15,16], but the goal in the present study was to ensure a valid comparison of properties. Results of dividing the SBS strength of the composites by the respective fiber volume fractions is shown in Figure 4b. Once normalized, the strengths were comparable, indicating that the remanufacturing process did not inherently reduce strength. Prepregging the recovered fibers would restore the prior fiber volume fraction, and thus, the mechanical properties of the composite. A previous COPV recycling demonstration (Voith Composites) demonstrated 80–90% retention of strength in short CF tapes [8]. Following normalization, the present method retained 94% of the first-generation composite.

Figure 4.

(a) Short beam shear strength of remanufactured tube compared to values from Figure 1. SBS strength error bars represent standard deviation. (b) SBS data normalized to the fiber volume fraction. The normalized error bars used error propagation.

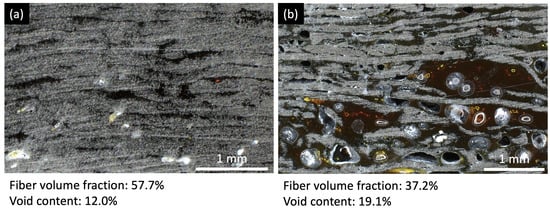

Figure 5 shows light micrographs of the first- and second-generation, remanufactured vitrimer tubes. These images elucidate the differences in SBS strength between the samples. The first-generation tube exhibited some fiber waviness and voids, but remained largely uniform. The remanufactured tube contained large resin pockets > 1 mm2 which act as stress concentrators, reducing the loading efficiency in SBS loading. We elected to allow for some resin residue on the CF tows after the dissolution to maintain tow integrity and reduce tangles in the fibers. As these tows passed through the wet winding process, additional resin was deposited between the layers, causing the resin pockets and reducing the mechanical properties. The additional resin present reduced the fiber volume fraction and thus the SBS strength of the composite. Due to instrument limitations, the recovered fibers could only be remanufactured in a wet winding process. The addition of a prepreg machine would provide sufficient compaction to restore the original fiber content to the tows.

Figure 5.

Light microscopy images of (a) towpreg vitrimer specimen and (b) remanufactured vitrimer specimen.

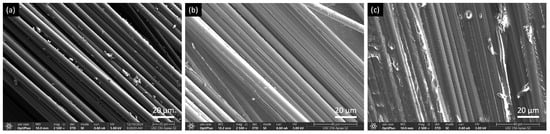

A major concern of composite recycling processes centers on possible detrimental effects on recovered fibers, as harsh recycling processes can damage CFs, leaving down-cycling as the only viable option [17]. Figure 6 shows micrographs of virgin fibers compared to two different sections of the remanufactured tube. The outer layer refers to the layer of the tube in direct contact with the dissolution liquid. The inner layer refers to the layer in contact with the mandrel and, therefore, the last material the solution penetrates. The absence of fiber damage indicates our mild conditions preserve integrity, unlike high-temperature methods that cause surface degradation, although the inner layer contained matrix residue. This excess material could be deemed either tolerable or intolerable. For the reuse of the recovered CFs with a matrix different than the first-generation composite, clean fibers can be expected to eliminate issues with adhesion based on the immiscibility of different polymers. However, when re-winding with the same resin, the resin may bond equally well to the matrix residue in regions as to fibers with sizing.

Figure 6.

Scanning electron micrographs of carbon fibers. (a) Virgin fibers. (b) Recycled fibers from the outside layer of tube during dissolution. (c) Recycled fibers from the inside layer of tube during dissolution.

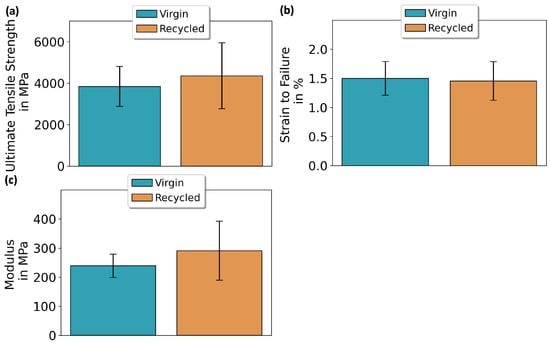

Single-fiber tensile testing elucidated the extent of performance retention following recycling. Figure 7 shows values for tensile strength, strain-to-failure and modulus values for tested fibers. The recycled fibers exhibited similar mechanical properties compared to the virgin fibers and are not statistically significantly different (p = 0.262). The standard deviation was larger for recovered fibers compared to virgin fibers from the supplier, indicating minor defects associated with the processing. The aforementioned DEECOM project yielded fibers with only 94 % strength retention at higher temperatures, compared to our reported method [18]. The acidic recycling solution did not interact with the carbon backbone of the fibers, thereby allowing for the retention of strength. The dissolution process involved mild conditions that did not damage the fibers, offering the possibility of genuine recycling, as opposed to down-cycling CFs. Full details of the recycling process are presently proprietary (Mallinda Inc., Denver, CO, USA). The retention of mechanical properties of the fibers explains the equivalence between the first- and second-generation SBS results after normalization (Figure 4b) because the fibers were not damaged in the recycling process.

Figure 7.

(a) Ultimate tensile strength of 0° reinforced control and vitrimer coupons. (b) Strain-to-failure values of the same samples. (c) Moduli values of the same samples. Error bars represent standard deviation.

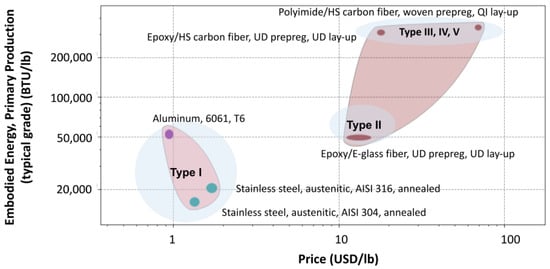

Major considerations affecting the design of future COPVs include fiber costs and embodied energy. Due to the high pressures required for efficient hydrogen use, Type IV tanks, which feature polymeric liners and a full CF overwrap, are necessary. Figure 8 shows the price of component materials and the embodied energies as a function of tank type. CF production involves process temperatures exceeding 3000 °C, and thus CFs have a high embodied energy (183–286 MJ/Kg) [19]. Type IV tanks require more CF than Type III vessels to withstand similar loads, resulting in even greater embodied energy. Recovering and recycling fibers from COPVs can divert these materials from landfills and recover the embodied energy.

Figure 8.

Adapted from ANSYS Granta EduPack v[2021 R2], Materials Selection Database, (ANSYS Inc., Canonsburg, PA, USA).

The benefits of the presented method compared to those associated with the previous recycling efforts discussed above are shown in Table 1. Our method, which utilized a vitrimer matrix, requires less thermal energy and demonstrated recycled fibers with no statistical difference from virgin fibers. A typical COPV used for a lightweight vehicle contains approximately 75 kg of CF [20]. Each kilogram of virgin CF requires 200 MJ of production energy, while recovering CFs from COPVs requires just 2.03 MJ/kg, indicating that recycling a single COPV can save approximately 15,000 MJ of embodied energy.

Table 1.

Comparison of COPV Recycling Methods.

4. Conclusions

We report a demonstration of unwinding of COPVs to recover continuous fiber tows, and subsequent re-use in a second-generation product. The selected vitrimer matrix was designed to be recycled, and the dissolution liquid can be returned to its original state, with multiple rounds of recycling [21]. A prototype towpreg with vitrimer epoxy matrix exhibited mechanical properties comparable to the control system, indicating recycling feasibility for the intended application.

The use of vitrimer technology will extend beyond the application of hydrogen containment. Other industries stand to benefit from the circularity of the process demonstrated, such as compressed natural gas, life support systems, and applications such as pipelines and subsurface fuel storage. Further advancements in vitrimer technology are expected to yield increases in mechanical performance and processability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K., C.G. and S.N.; methodology, A.K. and C.G.; formal analysis, A.K. and C.G.; investigation, A.K. and C.G.; resources, A.K., C.G. and S.N.; data curation, A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K.; writing—review and editing, C.G. and S.N.; visualization, A.K.; supervision, C.G. and S.N.; funding acquisition, S.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The Ershaghi Center for Energy Transition at USC under grant number CA101515-2010621. Funding for this project came from a cy pres award, as part of the distribution of a settlement relating to fuel economy for gasoline-powered vehicles.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated in this study are available in the text and Appendix A. Raw microscopy files and mechanical dataset are available from the authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Huntsman, Toray, and AirTech for generously providing materials. We gratefully acknowledge Philip Taynton, the CEO from Mallinda, for technical consultations. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Dragonfly Software (2022.2.0.1409) for the purposes of microscopy image segmentation in determining fiber volume fraction and void content. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| COPV | Composite overwrapped pressure vessel |

| CF | Carbon fiber |

| EOL | End of life |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| CFRP | Carbon fiber-reinforced polymer |

| SBS | Short-beam shear |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Fiber Properties.

Table A1.

Fiber Properties.

| Fiber | Toray T700S | Teijin HTS40 |

|---|---|---|

| Tensile Strength (MPa) | 4900 | 4400 |

| Tensile Modulus (GPa) | 230 | 240 |

| Elongation (%) | 2.1 | 1.8 |

| Density (g/cm3) | 1.80 | 1.77 |

| Filament Count | 24K | 12K |

| Sizing | 50C (1%) | PU (1%) |

Table A2.

Filament Winding Parameters.

Table A2.

Filament Winding Parameters.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Speed | 1.8 mm/s |

| Mandrel Rotation | 10 rpm |

| Mandrel Speed | 79.8 mm/s |

| Filament Width | 10 mm |

| Filament Thickness | 0.18 mm |

Table A3.

Filament-Wound Coupon Dimensions.

Table A3.

Filament-Wound Coupon Dimensions.

| Coupon | Diameter (mm) | Height (mm) | Layers |

|---|---|---|---|

| SBS | 152.4 | 38.1 | 14 |

| Dissolution | 31.75 | 50.8 | 2 |

References

- U.S. National Clean Hydrogen Strategy and Roadmap; U.S. Department of Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.hydrogen.energy.gov/library/roadmaps-vision/clean-hydrogen-strategy-roadmap (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Human Spaceflight Knowledge Sharing: Mitigating the High Risk of COPVs|APPEL Knowledge Services. Available online: https://appel.nasa.gov/2017/10/26/human-spaceflight-knowledge-sharing-mitigating-the-high-risk-of-copvs/ (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Houchins, C.; James, B.D.; Acevedo, Y. Hydrogen Storage Cost Analysis. In Proceedings of the Technical Report, DOE Hydrogen Program 2021 Annual Merit Review and Peer Evaluation Meeting, Virtual, 7–11 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mclaughlan, P.B.; Scott, P.E.; Forth, C.; Grimes-Ledesma, L.R. Composite Overwrapped Pressure Vessels, A Primer; Technical Report; Johnson Space Center: Houston, TX, USA, 2011.

- Taynton, P.; Ni, H.; Zhu, C.; Yu, K.; Loob, S.; Jin, Y.; Qi, H.J.; Zhang, W. Repairable woven carbon fiber composites with full recyclability enabled by malleable polyimine networks. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 2904–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, M.; Suzuki, M.; Kito, T. Understanding the Topology Freezing Temperature of Vitrimer-Like Materials through Complementary Structural and Rheological Analyses for Phase-Separated Network. ACS Macro Lett. 2025, 14, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingrid Colleau. ECOHYDRO, Recyclable Composites for Hydrogen Storage. Available online: https://imtech.imt.fr/2023/12/05/ecohydro-composites-recyclables-pour-stockage-hydrogene/ (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Mason, H. Recycling Hydrogen Tanks to Produce Automotive Structural Components. Available online: https://www.compositesworld.com/articles/recycling-hydrogen-tanks-to-produce-automotive-structural-components (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Reynolds, S.; Longworth, B.; Norris, J.; Norris, P.; Reid, C.; Longworth, B.; Uk, L.; Millington, P. Deecom®: A Sustainable Process Used in Various Reclamation Processes; Technical Report. Available online: https://www.carolinapec.com/files/files/deecom-a-sustainable-process-used-in-various-reclamation-processes-2.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Cygnet, Viritech Recover H2 Tank Continuous Carbon Fibers in Ford FCVGen2.0 project|CompositesWorld. Available online: https://www.compositesworld.com/news/cygnet-viritech-recover-h2-tank-continuous-carbon-fibers-in-ford-fcvgen20-project (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- D2344/D2344M-22; Standard Test Method for Short-Beam Strength of Polymer Matrix Composite Materials and Their Laminates. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- 11566:1996(E); Carbon Fibre—Determination of the Tensile Properties of Single-Filament Specimens. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1996.

- Mohammadi, N.; Pouladvand, A.R.; Beheshty, M.H. Optimizing Towpreg Parameters for Filament Winding: A Comparison with Wet Winding. Polym. Compos. 2025, 46, 15331–15341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiorse, S.R. Effect of void content on the mechanical properties of carbon/epoxy laminates. SAMPE 1993, 24, 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.G.; Bae, J.S.; Hwang, H.Y. A normalization method of measured elastic properties of glass NCF composites with respect to fiber volume fraction based on periodic microstructure micromechanics. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 36, 106767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broyles, N.S.; Verghese, K.N.; Davis, R.M.; Lesko, J.J.; Riffle, J.S. Pultruded Carbon Fiber/Vinyl Ester Composites Processed with Different Fiber Sizing Agents. Part I: Processing and Static Mechanical Performance. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2005, 17, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isa, A.; Nosbi, N.; Che Ismail, M.; Md Akil, H.; Wan Ali, W.F.F.; Omar, M.F. A Review on Recycling of Carbon Fibres: Methods to Reinforce and Expected Fibre Composite Degradations. Materials 2022, 15, 4991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hecker, M.D.; Longana, M.L.; Eloi, J.C.; Thomsen, O.; Hamerton, I. Recycling end-of-life sails by carbon fibre reclamation and composite remanufacture using the HiPerDiF fibre alignment technology. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2023, 173, 107651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakdel, E.; Kashi, S.; Varley, R.; Wang, X. Recent progress in recycling carbon fibre reinforced composites and dry carbon fibre wastes. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 166, 105340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hydrogen Storage; United States Department of Energy. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/eere/fuelcells/hydrogen-storage (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Mallinda Inc. Our Responsibility; Mallinda Inc.: Denver, CO, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.mallinda.com/responsibility (accessed on 7 October 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.