Abstract

Titanium alloy TC4 countersunk head bolts (CHB) are widely used in spacecraft structures, but the research on CHB does not receive enough attention at present. There are still some more opportunities worthy of in-depth research, such as insufficient research on CHB of high-strength fasteners for aerospace applications, an insufficient combination of CHB simulation tests with real working conditions, and inspection and testing methods. In this study, through the combination of finite element simulation and experiments, the working conditions of the CHB connection structure bearing tensile load and CHB screwing were analyzed, and the requirements of the CHB connection structure and installation of CHB were optimized. Based on the single-bolt tensile simulation, the working conditions of multi-bolt connection structures under eccentric load and single-bolt composite laminate connection structures under tensile load were analyzed. Meanwhile, the structure of CHB was further optimized, and the simulation analysis model of the CHB tightening process was established. The research shows that the larger fixing bolt countersunk angle θ1 and the smaller countersunk fillet radius r, the better the ultimate bearing capacity of the connection structure will be. When the countersunk bevel angle of pressure plate θ2 was greater than or less than 100°, the clamping force–angle slope will decrease, while when θ2 was smaller, it will have a greater influence on the slope. The coaxiality Φ had little influence on the slope around the allowable tolerance range (0.3 mm), but the influence on the slope becomes greater when it exceeds the tolerance range. The research results provide a reference and basis for the layout of CHB and the use of composite materials in aerospace connection structures.

1. Introduction

The launch vehicle is the most important and widely used space vehicle. A launch vehicle consists of tens of thousands of parts, and the assembly of the parts depends on fasteners [1,2,3]. According to statistics, there are about 680,000 fasteners in a rocket, and the weight of the fasteners can account for 10% of the rocket bay. The technology and application level of fasteners directly determine the quality and reliability of the spacecraft [4,5,6]. Aerospace fasteners are typical high-end fasteners. Compared with general fasteners, aerospace fasteners are used in harsher and more complex environmental conditions, which require higher performance, reliability, and accuracy. In addition, with the continuous development of the aerospace industry in various countries and the rise of private aerospace enterprises, higher requirements have been put forward for the integrity of aerospace fastener product series and the economy of batch use [7,8]. However, at present, aerospace fasteners have some problems, such as a weak standard system, complexity, and incompleteness, and there are also othersome problems, such as varied fasteners, complicated specifications, and backward technology. Light weight, high reliability, long life, and low cost have become the core pursuits in the aerospace field. Titanium alloy countersunk head bolts (CHB) are an important part of the fastening connections of aerospace equipment. Research on aerospace fasteners is conducive to supporting the high-quality development and sustainable development of aerospace equipment [9,10,11].

Dursun et al. [12] investigated the effects of fastener geometry (protruding head and countersunk head fasteners) and the coefficient of friction (COF) on the stress distribution around the hole of a double-lap single-bolt aluminum alloy joint. The results show that the joints with convex fasteners show lower tensile stress concentration and lower bearing stress near the bolt holes of the middle plate. Egan et al. [13] used the nonlinear finite element code (Abaqus) to model the force of CHB. The accuracy of the simulation was verified by experiments. Wang et al. [14] proposed a structural damage model for multi-bolt countersunk C/SiC composite joints. By comparing the simulation results with the experimental data, the validity of the model was confirmed. The results show that when the ratio of bolt pitch to through-hole diameter was 3, the mechanical properties of joint structure achieve the best results. Coman et al. [15] analyzed the effects of geometric parameters on damage initiation and growth in composite aluminum CHB. The failure propagation and damage mechanism of bolts were predicted by the established equivalent model. Zhai et al. [16] systematically evaluated the influence of single-lap countersunk composite bolted joints with bolt preload interaction with assembly on fatigue reliability. The fatigue damage model and extended finite method were used to characterize the damage of bore bearing and fatigue cracking of CHB, respectively. Sun et al. [17] performed progressive damage analysis on the mechanically fastened joints of two-dimensional C/SiC composites and superalloy CHB using Abaqus. Qi et al. [18] studied the effect of laminate countersunk depth on the fatigue life and structural stiffness of carbon fiber reinforced plastics (CFRP) connected structures, and the results showed that the fatigue life and structural stiffness of CFRP structures increased with the deepening of countersunk depth. Wang et al. [19] analyzed the failure mechanism and strengthening mechanism of the interference fit CHB thin-layer connection structure, and found that the use of thin-layer laminate in the interference area can suppress the damage and expansion of the structure. Aksoy et al. [20] used the combined tensile/shear load test device to conduct tensile tests on the CHB connection structure at five different loading angles, and observed that the bending moment increased with the increase in load and gradually decreased after increasing to a certain point. Qu et al. [21] analyzed the influence of interference fit on the fatigue behavior of single-CHB connection structures, and found that interference fit reduced the fatigue life of the connection structure. Ge et al. [22] conducted tensile experiments on single-CHB and multi-CHB composite metal joints. The bolt load distribution of multi-bolted connections before and after damage occurrence was predicted by establishing a finite element model with Hashin’s criterion and a modified Camanho’s degradation law. An increase in pin clearance around the largest bolt decreases the load near its bolt. Qin et al. [23] conducted numerical and experimental investigations on the influence of counterbore geometry errors on the fatigue behavior of CFRP bolted connections. The research results can provide a reference for establishing reasonable geometric accuracy requirements for CFRP joint hole machining. Zhang et al. [24] established a three-dimensional elastic–plastic model based on plasticity theory and applied it to the numerical analysis of the bearing strength of composite CHB connections. By comparing the numerical results with the experimental results, the ultimate bearing strength and the 2% offset bearing strength decreased when the bolt-tightening torque or bolt hole clearance increased. Feng et al. [25] used tensile tests and finite element analysis (FEA) to investigate the root cause of fracture during assembly of TC4 high-lock CHB. The results of microscopic analysis show that mixed fracture occurred in the bolt under tensile load. The initial failure was brittle fracture of the threaded surface, which subsequently translated into ductile fracture of the screw. Zhong et al. [26] studied the fatigue failure mechanism of titanium alloy CHB connections. The fatigue life of bolted connections can be improved by increasing the stiffness of connectors and selecting appropriate geometric parameters.

Based on the above analysis, on the basis of establishing the accurate simulation model of titanium alloy TC4 CHB, this study carried out the simulation and experimental analysis of single-bolt tensile working conditions, bolt screwing working conditions, and special working condition simulation and experimental analysis of CHB connection structures. In the process of analysis, the accuracy of the screwing-in simulation model was verified by the actual torque-clamping force test. The service situation of the CHB connection structure under the special working condition of multi-bolt eccentric load and CHB composite laminate connection structure was studied. Meanwhile, according to three kinds of multi-bolt arrangement modes, the influence of bolt arrangement modes on the ultimate eccentric load of the connection structure was analyzed through simulation and actual tensile tests, and some suggestions on multi-bolt arrangement modes in practical application are given.

2. Construction of High-Strength Titanium Alloy TC4 CHB Connection Model

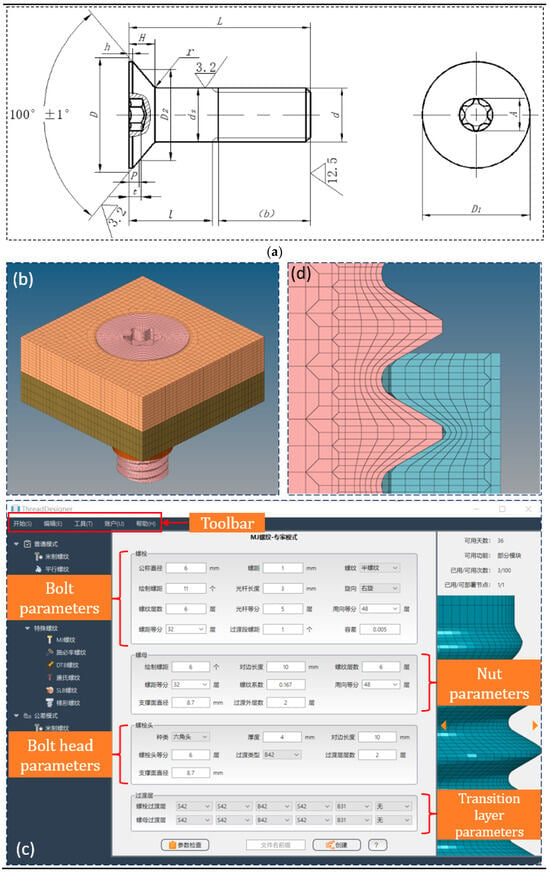

Aiming to make the simulation model accurately reflect the performance of CHB connection structures for aerospace applications, CHB were modeled and meshed according to the relevant standards of CHB. The schematic diagram of the standard CHB and the schematic diagram of some structural parameters and selected values are shown in Figure 1a and Table 1. After the size of the CHB was determined, the grid model of other parts in the connection structure was established according to the corresponding matching size and standard requirements. The simulation model of the CHB connection structure consists of four parts: the countersunk bolt, self-locking nut, laminate, and tooling. The part of the CHB consisting of the mesh of polished rod and thread was generated by the thread refinement modeling software ThreadDesigner (version 2023), and then divided by the pre-simulation processing software Hypermesh (version 2022). Figure 1c shows the parameters of bolts entered into the ThreadDesigner software. The laminate and tooling parts directly generate a hexahedral mesh through two-dimensional mesh stretching in Hypermesh. The resulting axonometric drawing of the CHB connection structure is shown in Figure 1b. An enlarged view of the threaded partial grid cell is shown in Figure 1d.

Figure 1.

Model establishment and mesh division of titanium alloy TC4 CHB. (a) Main parameters of CHB. (b) Mesh division of the CHB connection structure. (c) Parameters of the bolt finite element model in ThreadDesigner software. (d) Enlarged structure of grid elements of the threaded part.

Table 1.

Selected values of some parameters of CHB.

Except for the groove part of the bolt countersunk gear, which uses tetrahedral mesh (C3D4) because of its complex shape and difficulty in dividing hexahedral mesh, all meshes of the model adopt hexahedral mesh (C3D8R). By using the “check elems” tool to check the quality of the generated mesh in Hypermesh, the mesh sizes of the threaded part of the bolts and nuts and the CHB were about 0.3~0.4, and the mesh sizes of the empty rod section of the bolts and the outer surface part of nuts were about 0.6~0.7. The mesh sizes of the laminates and tooling parts were about 0.8~1.0. The mesh sizes meet the requirements of simulation accuracy. According to the inspection parameters of hexahedral mesh quality by Abaqus (mesh aspect ratio < 10, tetrahedral mesh corner angle 20°~160°, hexahedral mesh corner angle 10°~160°), the quality inspection was carried out in Hypermesh. The results show that the quality of the mesh meets the requirements except that the tetrahedral mesh corner angle of about 5% of the CHB part was less than 20°. The total number of meshes in the whole model was about 170,000, and the number of meshes in each part is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Number of grids for each component of the single-bolted connection structure.

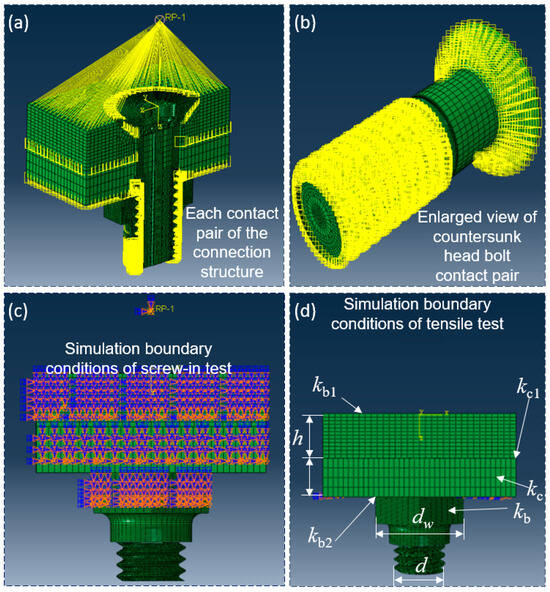

There were complex contact frictions in the tensile test or installation process of the CHB connection structure, mainly including the following: bolt and nut threads, bolt countersunk and laminate countersunk inclined surfaces, laminate lower and tooling upper surfaces, and tooling lower and nut upper surfaces (Figure 2a,b). In the bolt-tightening test, the laminate, tooling, and nuts were generally fixed and screwed into the laminate by rotating the bolts. According to the test setting, constraints were applied to the sides of the laminate, tooling, and nut in the simulation model, the countersunk head surface of the bolt was fixed at the reference point RP-1. The degrees of freedom of the surface except for U3 and UR3 were fixed. In the tensile analysis step, UR3 = 0.8 × t was controlled to control the CHB to be screwed into the laminate (Figure 2c).

Figure 2.

Mesh division and stress analysis of the high-strength titanium alloy model. (a) Each contact pair of the connection structure. (b) Enlarged view of countersunk head bolt contact pair. (c) Simulation boundary conditions of screw-in test. (d) Simulation boundary conditions of tensile test.

The simulation standard steps are set according to references [13,17]. Set the material TC4 used in this paper (density is 4.5 × 10−9 (t·mm−3); elastic modulus is 106,100 MPa; Poisson’s ratio is 0.3). The contact properties of each contact pair are as follows: the penalty function friction formula is selected for tangential contact, and the friction coefficient of other contact pairs is 0.1 except that the friction coefficient of contact pair ① is 0.15. The exponential formula is selected for normal contact, and the pressure and penetration parameters are 5 and 0.005, respectively. For the tensile test simulation, an Explicit Dynamic analysis step with a step size of T = 0.5 s is set, and a mass scaling with a target time increment of 10−6 is set to speed up the simulation analysis. For the screwing test simulation, a Static, General analysis step with step length T = 1 s is set up. The analytical methods are consistent with those in references [13,17].

The actual tensile test device generally fixes the tooling and indirectly applied load to the bolts by stretching the laminate. In the simulation model, the six degrees of freedom of the lower surface of the tooling were limited. The upper surface of the laminate was fixed to the reference point RP-1. A linearly increasing load CF3 = −70,000 × t(N) was applied to the reference point. The displacement of the reference point was extracted. When the displacement reaches a certain amount, the CHB has been broken and the simulation program is terminated (Figure 2d).

According to the stress analysis in Figure 2d, the CHB connection stiffness consists of the body stiffness kb, the contact stiffness kb1 of the lower joint surface of the bolt head, and the threaded joint surface stiffness kb2. The stiffness of the connected piece consists of the body stiffness kc and the contact stiffness kc1 of the joint surface of the connector [27,28].

The calculation method of bolt equivalent stiffness is Equation (1):

When the material and thickness of the upper and lower connecting plates are the same, the stiffness kc of the connected piece body is Equation (2):

φ is the half apex angle of the compressed area of the connected part, and its calculation method is Equation (3) [29,30]:

The solution method of the intermediate parameter Kpb1 of the contact stiffness kb1 of the joint surface under the bolt head is Equation (4):

The solution method of the intermediate parameter Kpb2 of the contact stiffness kb2 of the threaded joint surface is Equation (5):

An is specifically Equation (6):

The solution method of the intermediate parameter Kpc1 of the contact stiffness kc1 of the joint surface of the connector is Equation (7):

where pn(r) is a quartic polynomial curve about radius r, specifically, Equation (8):

where the constants of the quartic polynomial are Equation (9), respectively:

After synthesizing Equations (1)–(9) and considering the contact stiffness of the joint surface, the equivalent stiffness calculation methods of the bolt and the connected part are Equations (10) and (11):

According to Equations (10) and (11), the contact stiffness of the joint surface of the bolt can be calculated.

3. Multi-Working Condition Analysis of High-Strength Titanium Alloy Single Bolts

3.1. Test of Single-Bolt Tension

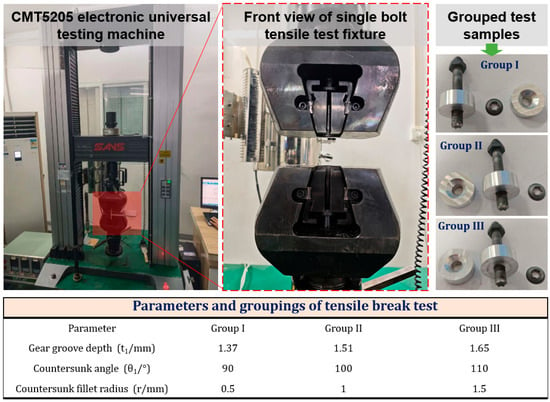

The pre-test verification was carried out according to the tensile test simulation model. The process was as follows: the grid model was established with the parameters of MJ6 × 1 CHB in Table 1 and the values of other components (self-locking nut, laminate and tooling) matched with it. The structural parameters such as MJ6 × 1 CHB and its matching self-locking nut required by existing standards (t1 = 1.51 mm, θ1 = 100°, r = 1 mm, coaxiality deviation Φ = 0) were used for tensile test simulation. In the simulation, ABAQUS (2025 version) software was used. Meanwhile, set the simulation parameters. The density of the material TC4 is 4.5 × 10−9 (t·mm−3). The elastic modulus is 106,100 MPa. Poisson’s ratio is 0.3. The contact attribute coefficient of friction is 0.1. Set up a Static, General analysis step with a step size of T = 1 s. The test piece was preloaded from 0 N to 100 N until the test piece was pulled off. Then, the control variable tests were carried out on the parameters of CHB (such as countersunk head angle, fillet radius, coaxiality deviation, etc.), respectively. The influence of the CHB connection structure on the ultimate tensile load was analyzed, so as to obtain regular conclusions, in order to put forward optimization suggestions for the structure of CHB. The values of grouped simulation test parameters are shown in Figure 3. The test equipment is a bolt universal testing machine in the test plant (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Test protocol and application conditions.

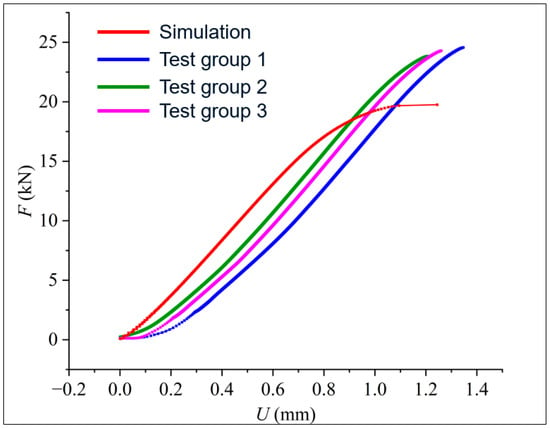

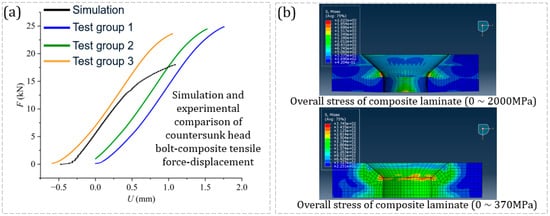

According to Figure 3, the force–displacement curve of the CHB in the Z direction (along the axial direction of the CHB and upward in the positive direction) obtained by actual tests (three groups in total, represented as “test group 1” to “test group 3”) was compared with the force–displacement curve obtained by simulation test (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Simulation and experimental comparison of force–displacement in the Z direction.

According to Figure 4, the simulation curve fits well with the test curve in the elastic stage, but after a period of tension, the bolt in the simulation enters the plastic stage faster and breaks. The average ultimate load of the three groups of test bolts was about 24.3 KN. The deviation between the ultimate load of the bolts in the simulation and the test was about 18.5%. The reason for the deviation may be that the plasticity curve of the TC4 material used in the CHB in Abaqus failed to pass the pre-test and be compared with the bolt plasticity curve used in this test. The damage-related parameters were empirical values, which may cause certain deviations. However, the general trend of the simulation curve was close to the test curve, and the influence of different parameters on the bearing performance of the CHB can also be reflected when the control variable test was carried out. After comprehensive analysis, the simulation model and environment meet the analysis requirements.

3.2. Influence of Structural Parameters on the Performance of Dangerous Sections

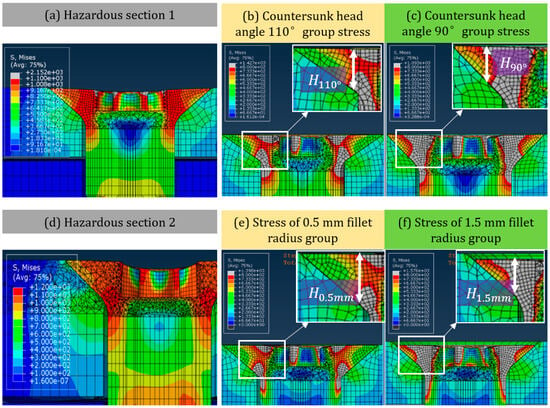

Taking countersunk head angles θ1 = 90° and 110° as examples, the stress conditions of the two sets of simulation tests when the elastic stage changes to the plastic stage (at this time t = 0.2 s, corresponding load F = 14 KN) were compared (Figure 5). The dangerous section in the group θ1 = 90° bears the greater load, and the grid that produces yield under the same tensile load penetrates the dangerous section faster, eventually causing fracture.

Figure 5.

Comparison of countersunk head angles of 110° and 90°.

The dangerous section of the bolt was the section along the axial direction of the fillet position of the CHB (dangerous Section 1, Figure 5a). For this section, the factor affecting the ultimate load of the bolt was the countersunk head height H of the CHB (Figure 1a). Another possible hazardous section was the cross section of the fillet portion of the CHB (hazardous Section 2, Figure 5d). This was because the cross-sectional area of the CHB decreases continuously from top to bottom, and the cross-sectional area reached the minimum value at the connection between the countersunk head and the polished rod. The wrenching groove of the CHB will also weaken the bearing performance of the cross-section. If the wrenching groove is too deep, the CHB will be tensioned and broken at the dangerous Section 2 position. However, in the simulation, even if the groove depth t1 reaches the nominal maximum value, the bolt still breaks at the dangerous Section 1 and the ultimate bearing performance is close, indicating that the groove depth t1 of the wrenching groove will not affect the ultimate bearing performance of the bolt within the nominal range.

Taking countersunk head angles θ1 = 90° and 110° as examples, the stress conditions of the two sets of simulation tests when the elastic stage changes to the plastic stage (at this time t = 0.2 s, corresponding load F = 14 KN) were compared (Figure 5b,c). The dangerous section in the group θ1 = 90° bears the greater load, and the grid that produces yield under the same tensile load penetrates the dangerous section faster, eventually causing fracture. Taking the radii of the countersunk head fillet R = 0.5 mm and 1.5 mm as examples, the stress conditions of the two sets of simulation tests when the elastic stage was converted to the plastic stage (t = 0.2 s, corresponding to f = 14 kN) were also compared (Figure 5e,f). The thickness of the dangerous section in the R = 1.5 mm group was smaller, which leads to the yield grid penetrating the dangerous section faster under the same tensile load, resulting in large-area material failure more rapidly, and finally causing bolt fracture.

3.3. Simulation and Test of Single-Bolt Screwing

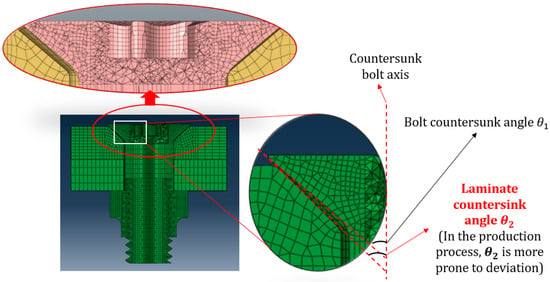

When there was a deviation between the countersunk angle θ2 of the laminate and the countersunk angle θ1 of the bolt, or there was a coaxiality deviation Φ between the countersunk axis of the laminate and the bolt, the preload force in the structure may be affected. The schematic diagram of each parameter is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram and simulation of various parameters of the screwing test.

When the screwing (torque-clamping force) test simulation analysis of the countersunk head bolt was carried out, the MJ6 × 1 CHB and its supporting structure in the existing standard (t1 = 1.51 mm, θ2 = 100°, r = 1 mm, Φ = 0; that is the “standard value” in Table 3) were simulated first, and the relationship between the clamping force and tightening torque between the laminate and tooling was obtained. The specific values of each parameter in the group simulation test are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Values of each parameter in the screwing test.

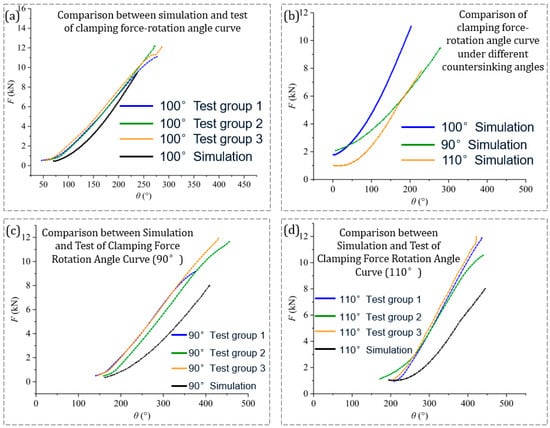

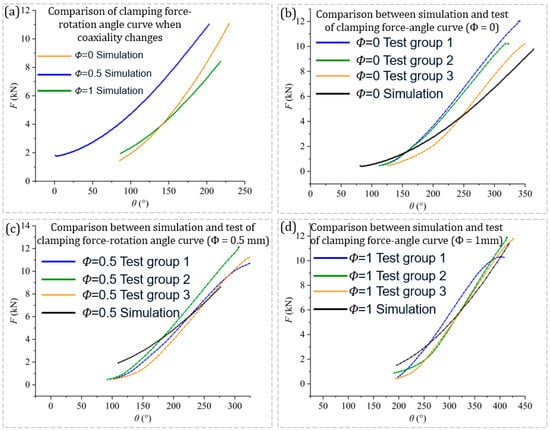

In addition, the experiment and simulation were compared. The test equipment was the bolt torsion and tension testing machine of the test plant (Figure 7). Compare the clamping force–angle curves of the CHB connection structure obtained by three sets of actual parallel tests (test curves 1~3) with the clamping force–angle curves obtained by simulation tests (simulation curves), as shown in Figure 8a. When there was a deviation between the c countersunk inclined surface angle of the laminate and the CHB angle, the inclined surface cannot fit closely with the countersunk inclined surface when the bolt was tightened, and the conversion rate of tightening torque to clamping force was reduced. The countersunk head angle of the fixing bolt θ1 = 100°, and the connection structure was simulated with the countersunk bevel angle θ2 = 90°, 100° and 110°, respectively. The results are shown in Figure 8b. In addition to θ2 = 100°, the simulation test results of θ2 = 90° and 110° were compared with the actual test results (Figure 8c and Figure 8d, respectively).

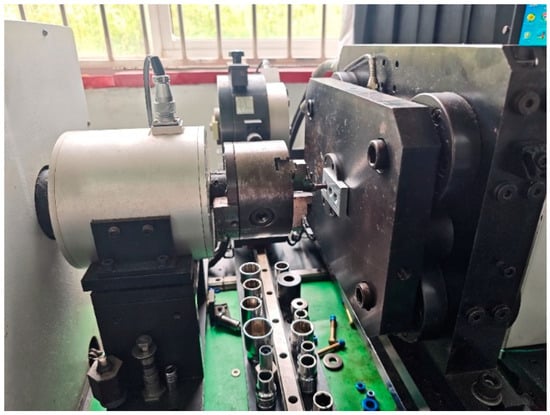

Figure 7.

Bolt torsion and tension testing machine.

Figure 8.

Simulation and experimental comparison of the influence of countersunk angle deviation on clamping force.

According to Figure 8a, after processing, the slope of the simulation curve was close to that of the test curve. After analysis, the simulation model and environment met the analysis requirements.

According to Figure 8b, in the three sets of simulation tests, when the bolts of the θ2 = 90° and 110° group start to be tightened, the tightening torque increased but the clamping force hardly increased. This is because no bolt preload was added to the simulation model, and the bolt countersunk bevel did not fit perfectly with the laminate countersunk bevel. When the corner was small, there was no clamping force between the laminate and the tooling. As the rotation angle (tightening torque) continues to increase, the growth slope of the clamping force gradually becomes larger and finally tended to be stable.

When the angle of the countersunk bevel was equal to that of the countersunk head, the slope of the clamping force growth in the stable section was the largest. When there was a deviation in the countersunk angle, the effective contact area between the bolt and the laminate was affected by the deviation. The clamping force growth was slowed down, and the clamping force growth was slower when the laminate countersunk angle was smaller than the bolt countersunk angle (θ2 < θ1) than when the laminate countersunk angle was larger than the bolt countersunk angle (θ2 > θ1). This is because when θ2 > θ1, and when the bolts were continuously tightened, the bottom of the countersunk bevel of the laminate will be deformed to adapt to the countersunk bolt shape, thereby increasing the effective contact area and increasing the clamping force slope. However, when θ2 < θ1, the laminate inclined surface is always in contact with the upper half of the countersunk bolt inclined surface. The effective contact area is always small, which affects the clamping force growth slope.

According to Figure 8c,d, the test and simulation curves were fitted respectively (the simulation curve only intercepts the second half of the steady growth section), and the slope of the simulation curve fitted well with the slope of the actual test curve (Table 4). The test curve only intercepted the steady growth section of the clamping force, which does not show the process similar to the simulation curve from the initial non-bonding and almost unchanged clamping force to the beginning of bonding and steady growth of the clamping force, but there was a similar process in the real test. Comprehensive analysis shows that the simulation test can roughly simulate the real detection test process.

Table 4.

Slope of clamping force–rotation angle fitting curve under different θ2 values.

When there is a deviation between the countersunk axis of the laminate and tooling and the countersunk axis of the bolt and nut, the countersunk inclined surface of the bolt can only contact half of the countersunk inclined surface at the initial stage of tightening, which makes it difficult to convert the tightening torque into clamping force. The clamping force–tightening torque curve shown in Figure 9a below was obtained by simulating the coaxiality deviation Φ = 0 mm, 0.5 mm, and 1 mm (the original situation was when the coaxiality deviation was 0). According to Figure 9a, when the CHB begins to be tightened, the clamping force increases slowly, and the slope of the clamping force–angle curve gradually increases to stability as the laminate is gradually clamped with the tooling. The curve fitting slope shows that Φ = 0 mm group > Φ = 0.5 mm group > Φ = 1 mm group, but when the coaxiality Φ = 0.5 mm, the curve slope decreases less, because the coaxiality deviation is close to the upper difference (0.3 mm) at this time, which has little influence on the growth of the clamping force (Table 5).

Figure 9.

Simulation and experimental comparison of the influence of coaxiality deviation on clamping force.

Table 5.

Slope of clamping force–rotation angle fitting curve under different Φ values.

Comparing the simulation test results of Φ = 0 mm, 0.5 mm, and 1 mm with the actual test results, such as Figure 9b–d, the simulation curve fits the test curve well. On the whole, the simulation test can roughly simulate the real detection test process.

Similar to the countersunk angle deviation, the coaxiality deviation will also affect the clamping force of the connection structure (Table 5). During actual assembly, if there was a coaxiality deviation between the laminate countersunk and countersunk bolt that was greater than the allowable maximum deviation (0.3 mm), but the bolts were still installed according to the original standard, the connection structure may not meet the clamping force required by the standard.

4. Analysis of Multi-Bolt and Multi-Working Conditions of High-Strength Titanium Alloy TC4

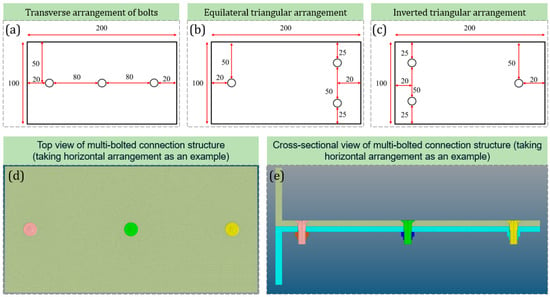

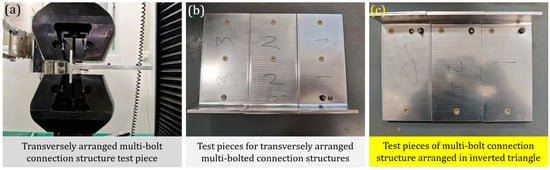

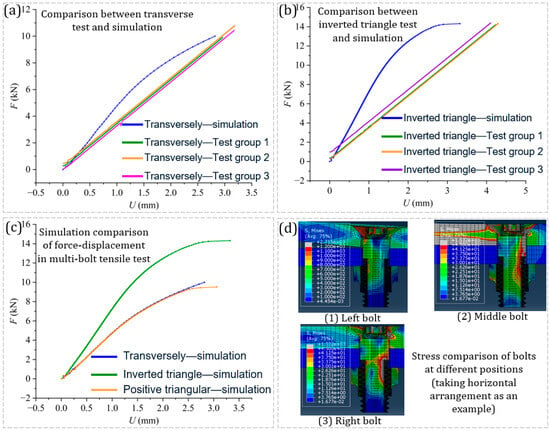

When the number of bolts was 3~5, the arrangement modes of the bolts in the connection structure mainly included transverse shape, regular triangle, inverted triangle, etc. (Figure 10a–c, in which the force application points of the laminate were all located on the left side), and the latter two arrangement modes were basically the same except that the eccentric load was different from the relative position of the bolts. Compared with the single-bolt connection structure, the overall structure and components of the multi-bolt connection structure were similar. The size of the laminate and tooling was changed from 20 mm × 20 mm × 5 mm in the single-bolt structure to 200 mm × 100 mm × 5 mm to simulate the actual working condition of arranging multiple bolts on the slender plate. The countersunk on the laminate and tooling was the same as that of the single-bolt connection structure. According to the above conditions, the grid model of the multi-bolted connection structure is established in Figure 10d,e below. Meanwhile, comparative analysis was carried out in combination with the experiments. The regular triangle arrangement and the inverted triangle arrangement were the same in the structure of the specimen, but the positions of applying the eccentric load were different. Therefore, only the model accuracy of the inverted triangle arrangement was verified in the experiment. The picture after the multi-bolt connection structure was clamped to the testing machine is shown in Figure 11. The force–displacement curve of the multi-bolt connection structure (transverse/inverted triangle test curves 1~3) was compared with the force–displacement curve obtained by simulation test (transverse/inverted triangle simulation curve), as shown in Figure 12a,b. The test force–displacement curves of each group were compared and analyzed as follows (Figure 12c).

Figure 10.

Bolt arrangement and simulation structure.

Figure 11.

Multi-bolt connection structure clamping to testing machine and arrangement.

Figure 12.

Analysis of the influence of the multi-bolt arrangement on ultimate eccentric load.

According to Figure 12a,b, the horizontal simulation curve was very close to the slope and the highest point of the test curve 1~3, and the fitting was good. The inverted triangle simulation curve was close to the highest point of the test curve 1~3, while the slope of the simulation curve was higher than that of the test curve. This was because in the simulation, the two bolts close to the force application point of the laminate were strictly equal distances from the edge of the laminate. The two bolts shared the tensile load equally and break at the same time. However, in the actual test, there were errors in the manufacturing of the specimens and the tensile load application point was not necessarily centered. The two bolts did not share the tensile load equally. In the tensile process, one bolt may bear most of the load first, and then the other bolt will bear most of the load after a certain amount of tensile yield. The two bolts were loaded alternately, resulting in a small slope of the actual test force–displacement curve. However, the ultimate bearing load obtained by simulation was similar to the actual test. After comprehensive analysis, the simulation model of the multi-bolt connection structure met the analysis requirements.

According to Figure 12c, for the group (transverse shape, regular triangle) with only one bolt on the side of the laminate applied force, the tensile length of the laminate edge (proportional to the tensile length of the bolts assembled on the laminate edge) is similar when the tensile load is the same. The stretching length is about 2.75 mm. The ultimate eccentric load borne by the connection structure is also similar. Both are approximately between 9.5 KN and 10 KN. However, the slope of the force–displacement curve of the group (inverted triangle) with two bolts on the stressed side of the laminate is obviously larger. A maximum of about 3.25 mm was achieved. The ultimate load was also higher (about 14 KN), about 1.5 times that of the other two groups (Table 6). When the laminate was subjected to an eccentric load, the laminate was subjected to a radial moment in addition to an axial tensile force, as compared to a case where the load was uniformly applied to the upper surface of the laminate. Most of the moment was borne by the countersunk portion of the bolt closest to the force application point, and a small portion was borne by the bolt located in the center of the laminate, while the bolts on the other side of the laminate hardly bear this part of the moment. The bolt closer to the force application point bears greater stress, and in the same bolt, the countersunk bevel of the bolt close to both sides of the long side of the laminate bears greater stress. For example, the stress on the left slope of the left bolt is greater, and the stress on the right slope of the right bolt is greater (Figure 12d, in which the stress cloud diagram of the left bolt ranges from 0 to 1200 MPa, and the stress cloud diagram of the middle and right bolts ranges from 0 to 45 MPa).

Table 6.

Ultimate bearing load of different multi-bolt simulation groups.

In addition, the simulation test was carried out on the set CHB composite connection structure simulation model, and three groups of repeated tension and breaking tests were performed. The comparison between the simulation curve of the force–displacement curve and the test curves 1~3 is shown in Figure 13a. The overall stress nephogram section of the composite laminate was compared with the stress nephogram section of the metal laminate in the single-bolt tensile test (Figure 13b).

Figure 13.

Stress analysis of the composite plate under tensile conditions of the bolt composite structure.

According to Figure 13a, the simulation curve fits well with the test curve in the elastic stage. However, after a period of tension, the bolts in the simulation enter the plastic stage faster and break. The average ultimate load of bolts in the three groups of the actual tensile tests was about 24.27 KN, and the deviation between the ultimate load of the bolts in simulation and in the test was about 25.7%. The reason for the deviation may be that the relevant parameters (including elasticity, damage) of the laminate composites in Abaqus had adopted values from relevant literature. Meanwhile, the maximum displacement deviation of the simulation experiment was 0.7 mm. However, the actual material parameters of the specimen were not obtained by pre-experiment. However, the CHB composite tensile test pays more attention to the stress of the composite laminate. Based on the above analysis, under the premise that the stress distribution of multi-laminated composites is the core research goal, the existing simulation model and environment can meet the preliminary analysis requirements, but there is still room for improvement in the simulation accuracy of bolt mechanical properties.

Combined with Figure 13b, compared with the metal laminate, the stress distribution of the composite laminate was more concentrated, the stress level at the stress concentration point was significantly higher, and the overall deformation degree of the laminate was greater. When both are 370 MPa, the stress distribution runs through the whole bolt head. When the experimental applied forces are at 2000 MP and 370 MPa, the simulated maximum stress peak deviations are 23 MPa and 5 MPa, respectively. This shows that although the deformation trend of the laminates is the same, the displacement increases with the increase in applied force, and the maximum stress deviation also increases.

5. Conclusions

ThreadDesigner and Hypermesh software were used to generate the fine mesh model of the titanium alloy TC4 CHB connection structure. Meanwhile, the structural stiffness of the CHB was modeled. Through simulation and experimental conclusions, the comparative study of single-bolt tension, single-bolt screwing in, multi-bolt eccentric load tension, and single-bolt composite plate structure tension was carried out.

- (1)

- The axial ultimate bearing load of the CHB was affected by factors such as countersunk head angle θ1 and fillet radius R. Within the allowable tolerance range of the current standard, the depth t1 of the wrench groove has almost no influence on the ultimate load-bearing performance. Taking θ1 = 100° and r = 1 mm CHB as a reference, the larger θ1 is and the smaller r is, the better the ultimate bearing performance of the connection structure will be.

- (2)

- When the CHB was installed and tightened, the clamping force and the slope of the rotation angle/tightening torque between the laminate and the tooling were affected by the angle difference between the bolt bevel and the countersunk bevel and the coaxiality deviation between the bolt and the laminate. Take the CHB connection structure with θ2 = θ1 = 100° and Φ = 0 as a reference. When θ2 was greater than or less than 100°, the clamping force–angle slope will decrease, while when θ2 was smaller, it will have a greater influence on the slope. The coaxiality Φ had little influence on the slope around the allowable tolerance range (0.3 mm), but the influence on the slope becomes greater when it exceeds the tolerance range.

- (3)

- When the multi-bolt connection structure bears an eccentric load (axial eccentric load), the number of bolts near the eccentric load application point determines the ultimate eccentric load of the whole connection structure, and the countersunk head inclined plane of the bolts near the eccentric load application point was a dangerous section. Compared with the horizontal arrangement, the triangular arrangement of bolts at the edge of the laminate can effectively improve the ultimate eccentric load of the whole connection structure.

- (4)

- In practical applications of multi-bolted connection structures, priority should be given to arranging all bolts on the side of the laminate that bears higher loads. Compared with metal laminates, composite laminates with the same structure and size had worse load-bearing capacity under single-bolt tensile conditions, and they are easily broken before the CHB break in actual working conditions.

- (5)

- The research conclusion of this paper can provide data and method support for high-strength rigid structural parts in the aerospace field. At the same time, random error simulation (such as bolt position deviation and loading point deviation) can be introduced to improve the adaptability of the model to actual working conditions in follow-up research on the difference between the “bolt equidistant arrangement” in bolt connection simulation and the “alternating load bearing” in actual tests.

Author Contributions

G.Y.: conceptualization. L.W. and L.H.: conceptualization, writing—original draft and writing—review and editing. W.F. and J.W.: formal analysis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52275442), (52505496), (52575511).

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviation

| CHB | Countersunk head bolts |

| COF | Coefficient of friction |

| CFRP | Carbon fiber reinforced plastics |

| FEA | Finite element analysis |

| Variable interpretation | |

| Ab | Bolt cross-sectional area |

| Eb | Elastic modulus of the bolt material |

| Lb | Equivalent length of the bolt under tension |

| Ec | Elastic modulus of the material to be connected |

| dh | Lower inner contact diameter of the bolt head |

| dm | Outer diameter of the connected piece |

| h | Thickness of a single connecting plate |

| φ | Half apex angle of the compressed area of the connected part |

| d | Nominal diameter of the bolt |

| C | Difference between the bolt hole diameter and the nominal diameter |

| R | Ratio of the thicknesses of the upper and lower connecting plates |

| νb | Poisson’s ratio of the bolt material |

| αn | Joint surface area of the screwed threaded part |

| Ln | Thickness of the nut |

| P | Pitch |

References

- Li, W.; Wang, L.; Yu, G. An accurate and fast milling stability prediction approach based on the Newton-Cotes rules. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2020, 177, 105469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liping, W.; Xiangyu, K.; Guang, Y.; Weitao, L.; Mengyu, L.; Anbang, J. Error Estimation and Cross-Coupled Control Based on a Novel Tool Pose Representation Method of a Five-axis Hybrid Machine Tool. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2022, 182, 103955. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Li, B.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y. Analysis and evaluation of multi-state wear mechanism of elastic-flexible thin-walled bearings. Tribol. Int. 2025, 202, 110293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.; Pueh, L.H.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y. Surface performance control and evaluation of precision bearing raceway with wireless sensing CBN grinding wheel. Wear 2025, 568, 205966. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y. Derivative analysis and evaluation of roll-slip fretting wear mechanism of ultra-thin-walled bearings under high service. Wear 2025, 562, 205630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Wang, L.; Wu, J.; Gao, Y. Milling stability prediction of a hybrid machine tool considering low-frequency dynamic characteristics. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2020, 135, 106364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Ye, J.; Cui, B.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y. Prediction and evaluation of the influence of static-dynamic aging wear of grease on life of high performance bearings (HPBs). Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 179, 109829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, L.; Yu, G.; Li, W.; Kong, X. A multiple test arbors-based calibration method for a hybrid machine tool. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2023, 80, 102480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, W. Real-time tool breakage monitoring based on dimensionless indicators under time-varying cutting conditions. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2023, 81, 102502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Bai, Q.; Cheng, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Ding, H. Investigation on an in-process chatter detection strategy for micro-milling titanium alloy thin-walled parts and its implementation perspectives. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 183, 109617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Du, P.; Qiu, X.; Zhao, X.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y. Enhanced dry machinability of TC4 titanium alloy by longitudinal-bending hybrid ultrasonic vibration-assisted milling. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 379, 134866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dursun, T.; Soutis, C. A finite element analysis of bolted joints loaded in tension: Protruding head and countersunk fastener. Int. J. Struct. Integr. 2017, 8, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, B.; McCarthy, C.T.; McCarthy, M.A.; Frizzell, R.M. Stress analysis of single-bolt, single-lap, countersunk composite joints with variable bolt-hole clearance. Compos. Struct. 2012, 94, 1038–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Guo, L.; Li, W.; Zhang, M.; Hong, Y.; Yang, W.; Zhang, Z. Influence of Design Parameters on Mechanical Behavior of Multi-Bolt, Countersunk C/SiC Composite Joint Structure. Materials 2023, 16, 6352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coman, C.D.; Crunteanu, D.E.; Cican, G.; Stoia-Djeska, M. Geometry Effects on Joint Strength and Failure Modes of Hybrid Aluminum-Composite Countersunk bolted Joints. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2024, 14, 12759–12768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Qu, H.; Li, D.; Ge, E.; Xiao, R.; Yang, J. Effect of bolt preload uncertainty on fatigue reliability of single-lap, countersunk composite bolted joints considering forced assembly interaction. Int. J. Fatigue 2025, 198, 109017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Lv, C.; Sun, X.; Jia, J.; Li, M. Impact Analysis of Countersunk Bolt Parameters on the Load-Bearing Capacity of a Ceramic Matrix Composite and Superalloy Joint. J. Appl. Mech. Tech. Phys. 2022, 63, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Liang, G.; Dai, Y.; Qiu, J.; Hao, H. The effects of countersink depth on fatigue performance of CFRP joint. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 128, 4397–4412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, M.; Zhao, Y.; Men, X.; Chang, Z.; Kang, Y. Bearing failure and strengthening mechanism of countersunk thin-ply laminated joints using an interference-fit bolt. Polym. Test. 2024, 130, 108298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, T.; Altıntaş, B.; Dilber, A.G. Investigation of the Structural Behavior of Countersunk Bolts Under Multi-Directional Loading[C]//ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition. Am. Soc. Mech. Eng. 2023, 87684, V011T12A015. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, H.; Li, D.; Zhai, Y.; Ge, E.; Xi, W.; Ji, C. Experimental investigation on the effect of forced assembly on fatigue behavior of single-lap, countersunk composite bolted joints. Int. J. Fatigue 2024, 189, 108542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, M.; Cheng, X.; Huang, W.; Hu, R.; Cheng, Y. Damage mode and load distribution of countersunk bolted composite joints. J. Compos. Mater. 2021, 55, 1717–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Cao, X.; Li, H.; Zhou, M.; Ge, E.; Li, Y. Effects of countersunk hole geometry errors on the fatigue performance of CFRP bolted joints. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B J. Eng. Manuf. 2022, 236, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, X.; Tian, A.; Fan, Y. Tests and numerical study of single-lap thermoplastic composite joints bolted by countersunk. Materials 2022, 15, 2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Dong, C.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ma, J.; Huang, Z.; Wan, Q. Fracture mode transition during assembly of TC4 high-lock bolt under tensile load: A combined experimental study and finite element analysis. Materials 2022, 15, 4049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Li, H.; Yang, L.; Xu, Y.; Peng, J.; Liu, J.; Zhu, M. Fatigue failure behaviour of bolted joining of carbon fibre reinforced polymers to titanium alloy. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 163, 108498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lu, X.; Wang, K.; He, F. Microstructure and mechanical properties of electron beam welded TC4 titanium alloy structure with backing plate. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 35, 106160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Miao, L.; Han, Y. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of TC4 Titanium Alloy Repaired by Metal Inert Gas under Different Current Modes. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2025, 31, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Guo, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Yang, Z. Effect of Micro-arc Oxidation/Multi-arc Ion Plating on the Galvanic Corrosion Behavior of TC4/AH36 Steel. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2025, 34, 22406–22416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Tang, S.; Wang, J.; Guo, G.; Jamil, M.; Ibrahim, A.M.M.; Hao, X. Study on milling of TC4 titanium alloy with swallowtail-shaped micro-textured PCD tools. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 140, 3227–3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.