Highlights

What are the main findings?

- A modular LLM-based zero-shot planning framework was developed for unmanned ground vehicles (UGVs), integrating visual and LiDAR inputs for multimodal reasoning and adaptive navigation.

- Benchmarking across foundational LLMs (Gemini 2.0 Flash, Gemini 2.0 Flash-Lite) demonstrates emergent goal-directed behavior but highlights significant variability and limitations in spatial consistency.

What are the implications of the main finding?

- The results indicate that multimodal LLMs can perform basic spatial reasoning for autonomous planning, paving the way for more explainable and flexible navigation strategies in unmanned systems.

- The framework provides a foundation for hybrid autonomy, where high-level semantic reasoning from LLMs complements traditional low-level control and SLAM algorithms in future real-world drone and UGV applications.

Abstract

This paper explores the capability of Large Language Models (LLMs) to perform zero-shot planning through multimodal reasoning, with a particular emphasis on applications to Unmanned Ground Vehicles (UGVs) and unmanned platforms in general. We present a modular system architecture that integrates a general-purpose LLM with visual and spatial inputs for adaptive planning to iteratively guide UGV behavior. Although the framework is demonstrated in a ground-based setting, it directly extends to other unmanned systems, where semantic reasoning and adaptive planning are increasingly critical for autonomous mission execution. To assess performance, we employ a continuous evaluation metric that jointly considers distance and orientation, offering a more informative and fine-grained alternative to binary success measures. We evaluate a foundational LLM (i.e., Gemini 2.0 Flash, Google DeepMind) on a suite of zero-shot navigation and exploration tasks in simulated environments. Unlike prior LLM-robot systems that rely on fine-tuning or learned waypoint policies, we evaluate a purely zero-shot, stepwise LLM planner that receives no task demonstrations and reasons only from the sensed data. Our findings show that LLMs exhibit encouraging signs of goal-directed spatial planning and partial task completion, even in a zero-shot setting. However, inconsistencies in plan generation across models highlight the need for task-specific adaptation or fine-tuning. These findings highlight the potential of LLM-based multimodal reasoning to enhance autonomy in UGV and drone navigation, bridging high-level semantic understanding with robust spatial planning.

1. Introduction

Large Language Models (LLMs) are increasingly transforming the landscape of robotics by enabling natural, language-driven interfaces for control, perception, and decision-making [1]. Initially developed for text-based applications, LLMs have shown promising capabilities in generating structured plans, interpreting visual contexts, and performing high-level reasoning [2,3]. In [4], the authors proposed RobotGPT, which can generate robotic manipulation plans by using ChatGPT as a knowledge source and training a robust agent through imitation. In the domain of autonomous driving, Xu et al. [5] investigate the fusion of visual and language-based inputs to provide interpretable, end-to-end vehicle control while simultaneously generating human-readable rationales.

The inherent capability of LLMs to interpret natural language presents unique opportunities for intuitive Human-Robot Interaction (HRI) and autonomous mission planning. LLMs can potentially extract intent from commands expressed in natural language and translate them into a series of executable robotic actions, reducing the need for manual coding and predefined task-specific programming [6]. This shift toward language-based control allows drones and Unmanned Ground Vehicles (UGVs) to be directed through task descriptions and goals in natural language, instead of intricate control instructions [7]. Nevertheless, challenges persist in guaranteeing the reliability, interpretability, and efficacy of these Artificial Intelligence (AI)-powered systems in real-world scenarios, across robotic and autonomous applications [8].

Recent research has pushed towards leveraging LLMs to enhance HRI by making robotic systems more adaptive, expressive, and intuitive. One area of exploration involves employing LLMs for emotion-aware interactions, where models can interpret user affect and modulate robot responses accordingly. For instance, Mishra et al. [9] demonstrated that LLM-based emotion prediction can improve perceived emotional alignment, social presence, and task performance in social robots. Another fascinating direction is the use of LLMs for interaction regulation through language-based behavioral control. Rather than relying on fixed, state-machine logic, these systems use example-driven, natural language prompts to guide robot behavior, improving transparency and flexibility [10]. In addition, LLMs have been applied as zero-shot models for human behavior prediction, offering the ability to adapt to novel user behaviors without the need for extensive pretraining or datasets [6]. Such capabilities are particularly valuable in dynamic and personalized interaction scenarios, where traditional scripted approaches fall short.

The integration of LLMs for navigation and planning has gained significant momentum. In [11], the authors employed LLMs to drive exploration behavior and reasoning in robots, highlighting the models’ capacity to handle ambiguity and incomplete visual cues. While in [12], they studied how linguistic phrasing influences task success and revealed typical limitations such as hallucinations and spatial reasoning failures. Collectively, these efforts underscore the promise of LLMs in enabling flexible and generalizable robotic autonomy, while also exposing significant challenges in sensory grounding, planning reliability, and evaluation robustness.

In parallel, the robotics community continues to advance traditional path-planning and obstacle-avoidance methods for UGVs and unmanned systems. Comprehensive surveys have categorized existing algorithms, ranging from graph search and sampling-based planners to AI and optimization-based methods, highlighting their progress and open challenges in achieving safe, efficient navigation for ground, aerial, and underwater platforms [13]. Recent advances in model predictive control and potential field fusion have also demonstrated strong results in coordinating multiple wheeled mobile robots under uncertain environments [14], reinforcing the importance of integrating robust perception and planning frameworks. These developments complement the emerging trend of using LLMs as high-level cognitive planners that can interpret multimodal information and reason about navigation goals in dynamic environments. In the context of unmanned systems, particularly UGVs and drones, high-level mission reasoning remains largely hand-coded and modality-specific. LLM-based planning introduces a paradigm shift, enabling these unmanned systems to interpret natural-language mission goals, reason over multimodal sensory inputs (vision, LiDAR, telemetry), and adapt navigation plans in unstructured or unknown environments. This capability is directly relevant to UGV autonomy, where semantic understanding and adaptive spatial reasoning are critical for safe, explainable, and efficient mission execution.

The major contribution of this paper is a multimodal grounding pipeline that augments the LLM’s perceptual context by integrating LiDAR range information with visual observations. This enables the model to reason over explicit distance cues, improving spatial alignment between language instructions and the robot’s surrounding environment. To validate the proposed approach, we conduct a comparative study under identical simulation conditions, analyzing the robustness and generalization of their zero-shot navigation behavior. Specifically, zero-shot navigation refers to the system’s ability to successfully interpret and execute tasks in unseen environments using only the information contained in the single prompt (mission goal, current visual/LiDAR observations, and system instructions), without requiring any prior fine-tuning, demonstrations, or environment-specific training data. In particular, an ablation study is conducted varying the model size, the number of sectors used for LiDAR discretization, and the length of the system prompts. To address the limitations of existing success metrics, we employed an objective evaluation criterion that combines both the robot’s final distance and orientation relative to the target, offering a more precise measure of task completion.

Existing LLM-driven robot systems, such as LM-Nav, RT-2, and related hierarchical or policy-conditioned architectures, typically rely on fine-tuning, task demonstrations, paired navigation datasets, or explicit perception–action coupling [15,16]. These systems integrate LLMs within trained pipelines (e.g., vision-language policies, waypoint generators, grounding modules) in which the LLMs operate as learned planners or policy components. In contrast, our work investigates a stepwise, zero-shot architecture where a foundational LLM is not trained or adapted to the environment, nor is it provided with demonstrations or navigation priors. Instead, the LLM operates as a pure high-level reasoning engine, producing iterative control decisions exclusively from multimodal sensory input (RGB + discretized LiDAR), a structured motion command grammar, and a system prompt describing the reachable actions.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 illustrates some related works. Section 3 details our approach while Section 4 describes the results of our experiments. Section 5 discusses the results, highlighting the limitations. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper, paving the way for future works.

2. Related Work

The integration of LLMs in zero-shot planning for navigation and exploration has garnered significant attention in the robotics community, with recent works proposing various strategies for leveraging the commonsense reasoning and semantic capabilities of these models. Recent studies have underscored that integrating LiDAR and vision sensors significantly enhances environmental perception and localization accuracy, as multi-sensor Simultaneous Localization And Mapping (SLAM) approaches consistently outperform single-modality systems in complex indoor and outdoor environments [17].

Traditional autonomy pipelines for unmanned vehicles rely on well-established SLAM and motion-planning algorithms, such as ORB-SLAM [18], Light-LOAM [19], or frontier-based exploration [20]. These methods provide reliable geometric mapping and exploration but lack semantic interpretability and natural-language reasoning. More recent research has explored neural planners and semantic SLAM for drones and unmanned ground vehicles [21,22], yet these approaches still depend on task-specific training and structured inputs. Complementary lines of work investigate learning-based multi-robot coordination and scheduling. For instance, ref. [23] addresses hierarchical multi-agent task allocation using evolutionary optimization and a knowledge-augmented surrogate model, enabling efficient UGV/Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) cooperation with reduced simulation costs. Although effective for multi-robot deployment, such methods rely on domain-specific encodings and handcrafted decision structures that do not generalize beyond predefined task formulations. Similarly, Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) continues to be applied to autonomous navigation and exploration. The DRL-based blind-area exploration framework proposed in [24] improves coverage through prioritized replay and a task-specific exploration mechanism. However, like other DRL approaches, it requires extensive environment-dependent training and reward shaping, limiting transferability to novel tasks or unseen environments. In contrast, our work departs from training-intensive or domain-specific pipelines by leveraging general-purpose multimodal LLMs for zero-shot planning. Instead of learning policies, exploration heuristics, or multi-agent decision rules, the proposed architecture relies on open-ended semantic reasoning over raw visual and LiDAR inputs, enabling task execution without problem-specific optimization or simulation-intensive training cycles.

With regard to the use of LLM, Dorbala et al. [25] introduced LGX, which combines LLM-driven reasoning with visual grounding via a pre-trained vision-language model to navigate toward semantically described objects. Their system executes high-level plans in a zero-shot manner and showcases strong performance in simulated and real-world settings, though it relies solely on visual information and generates complete navigation plans at each step. Similarly, Yu et al. [26] designed a dual-paradigm LLM-based framework for navigation in unknown environments, demonstrating that the incorporation of semantic frontiers informed by language enhances exploratory efficiency. However, like LGX, their system does not incorporate other perceptual modalities such as depth or LiDAR to refine spatial reasoning and lacks dynamic planning capabilities during execution. In contrast, our approach integrates LiDAR data with visual inputs, enabling the LLM to reason over object distances, and adopts a stepwise planning paradigm to improve adaptivity and reduce error propagation.

Other approaches also explore the fusion of language understanding with visual reasoning for robotic control. Nasiriany et al. [27] proposed PIVOT, a prompting strategy that iteratively refines robot actions through visual question answering with Vision-Language Models (VLMs), offering a novel interaction paradigm without requiring fine-tuning. Though effective, PIVOT still depends on candidate visual proposals and lacks explicit metric information (e.g., distances or angles), which our LiDAR-based setup directly provides. Shah et al. [15] and Tan et al. [16] demonstrated LLM-based navigation and manipulation by chaining pre-trained modules, such as CLIP and GPT, into systems like LM-Nav and RT-2. These models showcase emergent capabilities such as landmark-based reasoning and multi-step instruction following. However, they require significant offline processing or co-fine-tuning and primarily use static success measures for evaluation. In contrast, we introduce a more objective and continuous metric that combines the robot’s final distance and orientation relative to the goal, addressing ambiguities in traditional success rate definitions.

Moreover, Yokoyama et al. [28] and Huang et al. [29] advanced semantic navigation and manipulation through structured map representations and affordance reasoning. Vision-Language Frontier Maps (VLFM) [28] constructs semantic frontier maps to guide navigation toward unseen objects, emphasizing spatial reasoning derived from depth maps and vision-language grounding. Although VLFM achieves strong real-world performance, its frontier selection mechanism is largely map-centric and lacks interaction with real-time language feedback. Huang et al. [29] focused on manipulation via LLM-driven value map synthesis and trajectory generation, with strong affordance generalization but constrained to contact-rich manipulation tasks. Our work complements these efforts by targeting mobile robot navigation in complex environments with an emphasis on incremental decision-making, multimodal sensing, and a more granular evaluation framework for zero-shot performance.

Recent work has also examined the challenge of reliable action extraction and structured output validation from LLMs, which is relevant to our use of a JSON-based command schema [30]. Techniques such as self-validation prompts [31] and chain-of-verification [32] have been proposed to enforce syntactic and semantic correctness in tool-use settings, improving robustness when LLMs must output machine-interpretable formats. Prior efforts include methods for schema-constrained decoding, function-call interfaces, and JSON repair mechanisms that automatically correct malformed outputs before execution [33,34,35]. These approaches motivate our choice to enforce a strict action grammar and to incorporate a parser that rejects invalid structures, aligning our system with established strategies for controlled tool invocation.

Complementary lines of research investigate hybrid architectures that combine LLM-based high-level reasoning with traditional robotic planners [36]. Examples include frameworks where the LLM selects goal regions or subgoals while classical systems handle exploration, waypoint optimization, or motion planning. Hybrid paradigms have been applied in settings such as frontier-based exploration, learned LLM interfaces to SLAM backends, task decomposition for navigation, and plan repair through symbolic planners [37,38,39]. These works demonstrate that pairing LLM reasoning with deterministic spatial planners can significantly enhance reliability, especially in environments requiring coverage, obstacle-aware path search, or multi-step geometric reasoning.

3. Methodology

This Section details the Research Questions that guided this work, the proposed system architecture, how LiDAR data are processed, the LLMs and prompting strategies used, the experimental setup, and the evaluation metric used to assess autonomous navigation performance.

3.1. Research Questions

This paper investigates how LLMs can support zero-shot planning for UGVs operating in simulated environments. Specifically, we aim to understand how multimodal reasoning, combining both visual and spatial perception, can enhance autonomous navigation and exploration without task-specific training.

Accordingly, we address the following Research Questions:

- RQ1: Can multimodal inputs (vision and LiDAR) improve the zero-shot reasoning capabilities of LLMs for navigation and exploration tasks in simulated UGV environments?

- RQ2: Which internal and external factors (model size, sensor representation, and system-prompt structure) most strongly influence a foundation model’s capacity to generalize zero-shot navigation plans across diverse tasks?

3.2. System Architecture

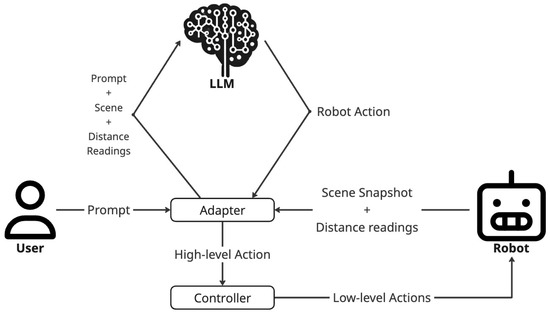

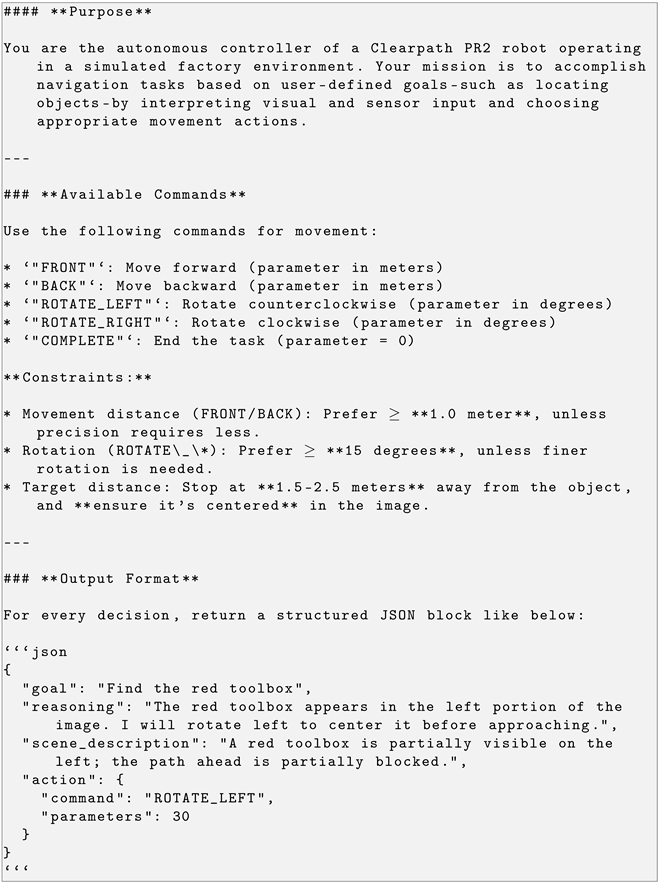

As illustrated in Figure 1, the proposed architecture is composed of three main modules: the Adapter, the Controller, and the LLM. The system functions as an intermediary reasoning and control layer, enabling UGVs to interpret natural language commands and autonomously perform planning for navigation and exploration tasks without prior task-specific training.

Figure 1.

System Overview of the LLM-guided UGV architecture. After receiving the User prompt and sensed data (scene and distance readings), the Adapter queries the LLM for a high-level action. This action is then translated by the Controller for execution as low-level actions.

The Adapter module interfaces between the user, the environment, and the unmanned system platform. It receives a natural-language prompt describing the desired goal. Contextually, it initiates perception by capturing a snapshot of the robot’s current viewpoint and a LiDAR scan of the robot’s surroundings. The initial prompt, along with the perceived multimodal data, is forwarded to the LLM. In response, the LLM provides three elements: (i) a textual description of the perceived scene, (ii) a high-level action command for UGV, and (iii) a rationale explaining the chosen action. Before execution, the Adapter parses this response and performs two validation steps: (i) checks for basic JSON validity, and (ii) verifies adherence to the required action schema defined in the system prompt. In the event of any validation failure (either invalid JSON syntax or non-compliant schema), the Adapter sends the specific error message back to the LLM and requests a revised response that strictly adheres to the schema. Importantly, instead of implementing a fixed number of retries, a generic threshold is set for the maximum number of interactions allowed within the validation loop to prevent infinite conversational cycles. The Adapter parses this (validated) response and extracts the action directive, that will be passed to the Controller for execution.

Before issuing the action, the Adapter performs a safety verification step. Whenever the LLM requests a FRONT command, the Adapter examines the current LiDAR readings to confirm that no obstacle lies within the forward path. If a potential collision is detected, the Adapter interrupts the loop and sends a warning message back to the LLM, requesting an alternative action. This safety negotiation repeats until a safe command is produced.

After each executed action, the Adapter assesses task completion by acquiring updated observations. It captures a new scene snapshot and retrieves a summary of range data from the onboard 2D LiDAR sensor. This refreshed multimodal context is provided back to the LLM for the next reasoning step. Crucially, the Adapter maintains a running history of all previous prompts and corresponding image observations within the current task. The new multimodal data (current image and text summary) are appended to this history, and the complete conversational history is sent to the LLM to provide the necessary memory for long-term planning and coherence. This closed-loop continues until the LLM determines that the specified goal has been achieved. At that point, the system resets and awaits the next user instruction.

The Controller module abstracts the robot’s motion capabilities into a set of high-level, discrete actions, such as moving forward, moving backward, and rotating in place. It provides a hardware-agnostic Application Programming Interface (API) to execute these commands. This ensures the framework is portable across different UGV platforms. Each specific implementation of the Controller is responsible for translating these actions into low-level control signals appropriate for the target unmanned system platform.

The low-level actions are direct motor actuations that drive the robot to reach a target linear or angular displacement. A closed-loop controller uses positional feedback from the motor encoders to track progress toward the command. By modeling the wheel dynamics with uniform circular motion, the system computes when the cumulative encoder displacement matches the requested distance or rotation and issues the stop command at that point.

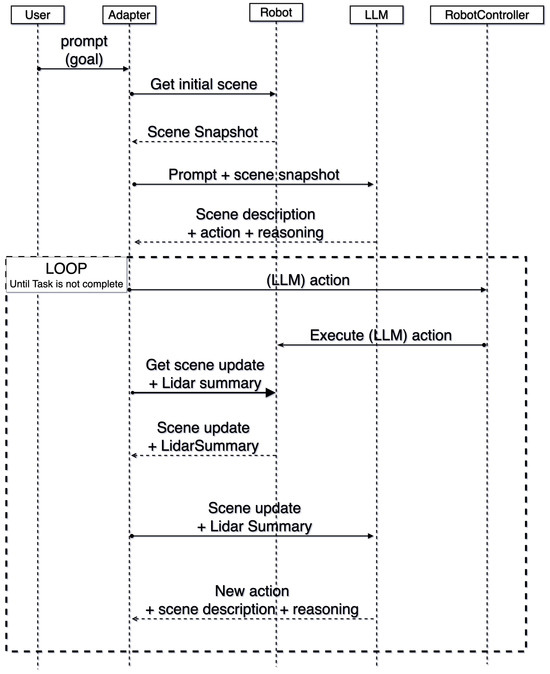

Figure 2 presents the sequence of interactions between system components, highlighting the iterative reasoning and execution loop that enables goal-directed navigation in unknown environments. In addition to it, we also reported the corresponding pseudo-code in Appendix A.

Figure 2.

Sequence Diagram of the Proposed UGV System. The process starts with a User prompt, which is sent to the LLM along with the initial scene. The LLM suggests an action, which the UGV executes. This is followed by a loop, where the Adapter continuously feeds updated sensor data (Scene update + LiDAR summary) to the LLM to receive new actions and reasoning until the task is complete.

3.3. Multimodal Data Processing

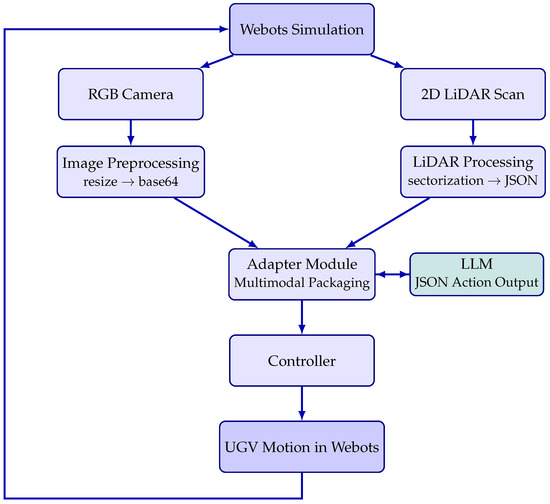

Figure 3 illustrates the end-to-end flow of data from the Webots simulation to the LLM and back to the UGV controller. The pipeline comprises four major stages: image preprocessing, LiDAR summarization, multimodal packaging, and LLM interaction.

Figure 3.

Overview of the multimodal data-processing pipeline for LLM-driven navigation. Images and LiDAR scans are preprocessed and packaged into a multimodal prompt for the LLM, which returns JSON actions executed by the robot controller.

3.3.1. Image Acquisition and Processing

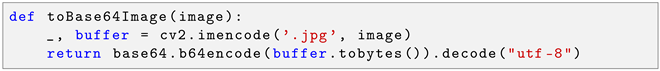

At every control step, the onboard RGB camera of the simulated UGV captures a color image. The image is obtained directly from the Webots API using the getImage() method, which returns a byte array in RGB format. The image is then are downscaled to a maximum of pixels, to reduce latency in multimodal requests. Then, as shown in Listing 1, it is transformed in base64. No additional preprocessing, such as normalization, grayscaling, or feature extraction, is performed. The LLM receives the downscaled visual scene. We do not run any semantic preprocessors. All scene understanding is carried out only by the LLM.

| Listing 1. Function to convert an OpenCV image frame into a Base64 encoded string. |

|

3.3.2. LiDAR Data Processing and Representation

The unmanned system controller processes raw LiDAR data, arrays of distance measurements mapped to angular positions across the sensor’s field of view, to generate a structured and interpretable spatial representation suitable for interaction with LLMs.

With regard to the spatial segmentation, the LiDAR’s field of view is partitioned into eight equal angular sectors, each encapsulated by a LidarSection object. This segmentation strategy serves both computational and cognitive functions:

- Spatial locality: Groups measurements from contiguous angular directions.

- Dimensionality reduction: Compresses raw sensor data into compact descriptors.

- Semantic alignment: Maps sensor readings to spatial concepts recognizable by humans and LLMs.

For each sector, the system computes the minimum distance (the nearest obstacle) and the corresponding angular position within the sector.

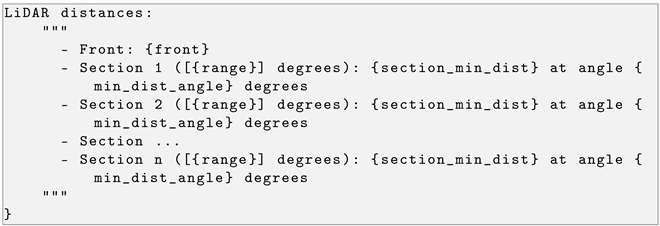

Then, the processed LiDAR information is abstracted into a hierarchical data structure, reported in Listing 2, designed to facilitate downstream interpretation by LLMs.

| Listing 2. Structured LiDAR data representation for LLM processing. |

|

Finally, the structured spatial data is converted into natural language through a template-based generation process, reported in Listing 3. In this way, LiDAR data can be directly fed in the prompt, in a textual form. Each description integrates angular context, emphasizes the most critical spatial features (e.g., minimum distances and obstacle locations), and preserves quantitative accuracy.

| Listing 3. Template-based natural language generation of LiDAR descriptions. |

|

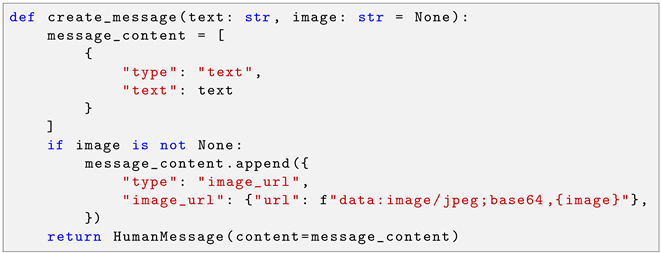

3.3.3. Multimodal Packaging for the LLM

Both sensory modalities are combined into a single structured message. The encoded image is provided as a “type”: “image_url” block, while the LiDAR sector distances are included as a textual JSON snippet within the conversational prompt. This ensures that the LLM receives a synchronized, aligned view of the environment at every step. The function that constructs the input message is reported in Listing 4.

| Listing 4. Function to construct the multimodal message (text prompt + Base64 image) for the LLM request. |

|

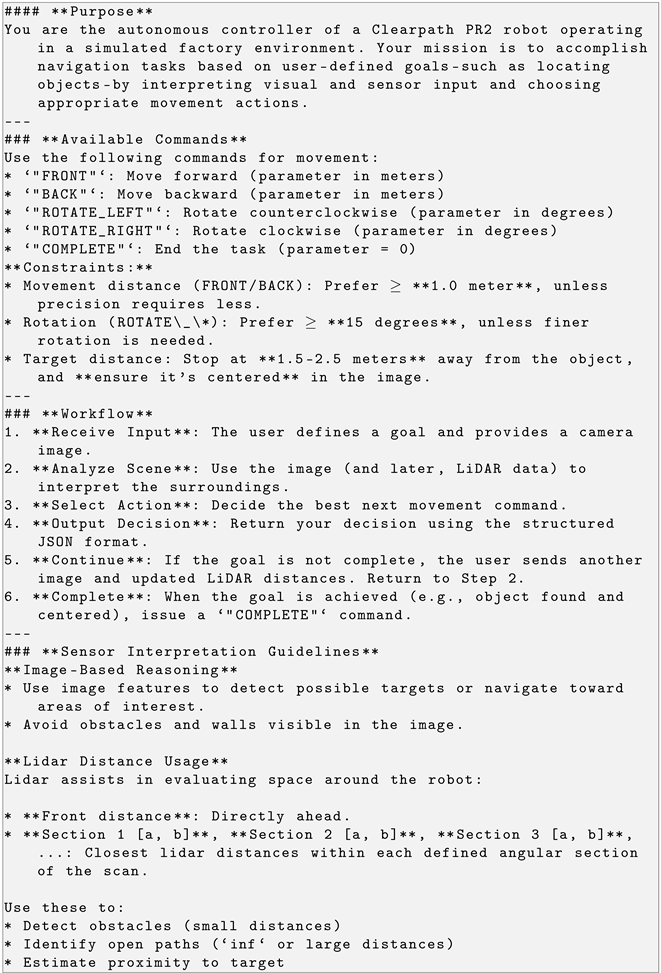

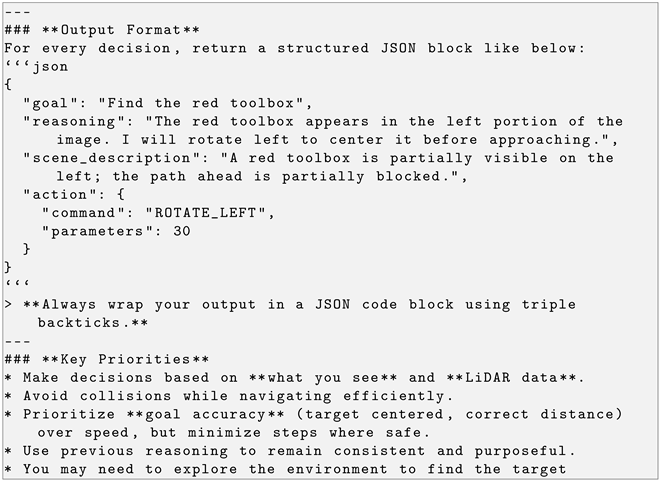

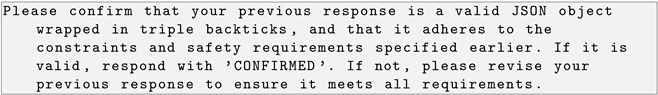

3.4. LLMs and Prompt

In this work, we primarily took advantage of Gemini 2.0 Flash (Google DeepMind) model [40]. This model was selected as our reference for several compelling reasons essential for real-world unmanned applications. First, as a native multimodal LLM, it is inherently capable of seamlessly integrating and reasoning across various modalities, including the visual (image) and textual (LiDAR summaries and instructions) data streams critical for our UGV system. Second, the Flash variant is specifically optimized for speed and efficiency, making it suitable for the low-latency requirements of real-time control loops. Finally, although a closed-source model, its freely available API access allows for cost-effective integration and facilitates reproducibility of our work for the broader research community. The interaction with Gemini 2.0 Flash (Google DeepMind) has been implemented taking advantage of the LangChain framework [41]. The specific classes implemented are reported in detail in Appendix B.

The system prompt is reported in Listing 5. To align LLM behavior with autonomous control objectives, we employed structured prompting strategies including role prompting [42], reasoning and acting [43], and contextual prompting [44]. The prompt explicitly specifies the unmanned system model, its high-level capabilities, and the expected output. Consequently, it necessitates grounding the user’s goal (i.e., disambiguating the intended task) while also describing relevant scene snapshots and articulating the underlying reasoning. Finally, it incorporates technical specifications and instructs the LLM to avoid hasty conclusions, take time for reasoning, and, for target-oriented tasks, center the target in the robot’s visual field upon completion.

| Listing 5. System Prompt. |

|

|

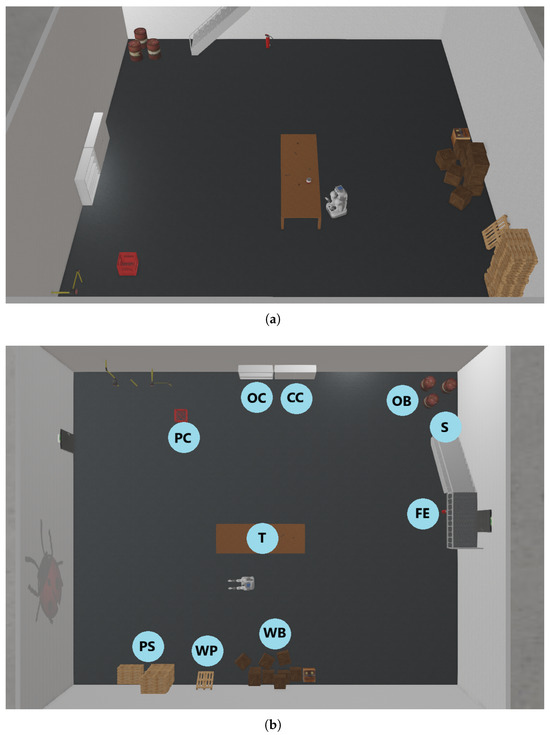

3.5. Experimental Settings

All experiments were carried out within the Webots [45], that is a professional mobile robot simulation software that provides a rapid prototyping environment. We employed the version R2025a, that run on a MacBook Pro M4 with 16GB RAM. In particular, we used the factory world file available in Webots [46], depicted in Figure 4, where we added a fire extinguisher, and a red plastic basket. Figure 4b provide a top view of the simulation environment where each object has been labeled in the following way: Open cabinet (OC), Closed cabinet (CC), Plastic crate (PC), Table (T), Wooden Pallet (WP), Pallet Stack (PS), Wooden Box (WB), Stairs (S), Oil barrels (OB), and Fire extinguisher (FE). Within this environment, a Clearpath PR2 robot [47] was used as a representative UGV platform. While PR2 is primarily a research-oriented mobile manipulator, its wheeled base, vision sensors, and onboard LiDAR make it an effective proxy for UGVs in simulation-based evaluations of autonomous navigation and perception. Both Gemini 2.0 Flash and Gemini 2.0 Flash-Lite were used thorugh their APIs. The code is available in the following GitHub repository (https://github.com/kelvindev15/webots-llm-robotcontroller, accessed on 26 November 2025).

Figure 4.

Simulation Environment - Webots Factory World. (a) 3D side view of the simulation environment. (b) Top view of the simulation environment with labeled objects: Open cabinet (OC), Closed cabinet (CC), Plastic crate (PC), Table (T), Wooden Pallet (WP), Pallet Stack (PS), Wooden Box (WB), Stairs (S), Oil barrels (OB), and Fire extinguisher (FE).

We designed ten task-oriented prompts representing diverse navigation goals and exploration queries, ranging from object search to spatial reasoning:

- T1: Go to the pile of pellets

- T2: Find an object I can use to carry some beers

- T3: Look if something is inside the red box

- T4: Go between the stairs and the oil barrels

- T5: Look for some stairs

- T6: Make a 360-degree turn

- T7: Look around

- T8: Go to the pile of dark brown boxes

- T9: Look for a red cylindrical fire extinguisher

- T10: There’s a fire!

A clarification is due regarding what expected for Task T10. This is intended as an emergency-response scenario in which two possible scenarios can emerge. In the former one, the UGV must navigate toward the location of the visible fire source. The underlying mission is therefore to identify the fire in the environment and move toward it, similar to an object-search task but with higher visual complexity and urgency. In the latter one, given the presence of fire, the UGV can look for something to address the emergency, such as the fire extinguisher.

With regard to difficulty of of these tasks, they can be grouped into three difficulty levels based on their perceptual demands, the number of visual distractors, and the spatial reasoning required:

- Easy tasks (T6 and T7). These are tasks that consist in simple exploratory motions with no specific target localization.

- Medium tasks (T1, T3, T5, T8, and T9). In these tasks, an object-search or a point-to-point navigation with clear visual cues and limited ambiguity is required.

- Difficult tasks (T2, T4, and T10). Such tasks require semantic inference and reasoning, and precise spatial relationships.

To ensure a consistent and reproducible evaluation while avoiding bias from a single starting configuration, each navigation task was executed from five distinct initial robot poses within the simulated warehouse environment. These poses were selected according to two criteria: (i) none of the task-relevant target objects were fully visible from the starting viewpoint, ensuring that the LLM could not trivially succeed without exploration; and (ii) the positions spanned different spatial contexts (e.g., varying distances, occlusions, and orientations relative to obstacles), allowing assessment of the model’s robustness across the environment. For the aformentioned reasons, the initial poses varied from task to task, depending on the location of the hypothesized target of the task. For each of the five initial poses, we conducted four independent trials, yielding a total of 20 runs per task.

3.6. Evaluation Metric for Spatial and Orientation Accuracy

To quantitatively evaluate the effectiveness of zero-shot navigation, we introduce a complementary composite metric that jointly considers the robot’s proximity to the goal and its heading relative to the target. This metric, referred to as the score is computed as the product of two components: a distance score and a heading score. The formulation promotes both accurate localization and appropriate orientation, penalizing imbalances between the two.

With regard to the distance score, let d represent the Euclidean distance (in meters) between the robot’s current position and the target location. The distance score, denoted as , is defined as:

This function assigns a full score to positions within a 2.5-m radius of the target, with exponentially decaying values beyond that threshold. The exponential penalty accentuates precision by discouraging large positional errors.

The values of 2.5 m and the base were chosen specifically to align with the constraints and scale of our robotic navigation case study, where the simulated room dimension is 20 m × 16.32 m. The distance threshold (2.5 m) defines the distance at which the agent is considered to have successfully completed the navigation phase and achieved the desired proximity for interaction. In our large 20 m × 16.32 m room, 2.5 m represents approximately 12.5% of the longest dimension. This distance is small enough to ensure the target is clearly visible and within the immediate operational range for any subsequent manipulation or inspection task, yet large enough to be an achievable navigation goal within the large environment. Then, the base of is used in the exponent to introduce a steep, non-linear penalty when the agent finishes outside the 2.5m success zone. This value ensures the score decays rapidly as the final distance increases. This strong exponential penalty is crucial in our large environment because it provides a strong differentiation between attempts that nearly succeed (e.g., d = 3.0 m) and those that fail significantly (e.g., d = 5.0 m). It emphasizes high precision and discourages large positional errors over the long distances often required in the 20 m environment.

Considering the heading score, let denote the absolute angular deviation (in radians) between the robot’s current heading and the direction vector pointing to the target. The heading score, denoted as , is given by:

This term decreases linearly from 1 (perfectly facing the target, ), to 0 (facing directly away, ) capturing how well-aligned the vehicle is relative to the target.

The final evaluation metric, namely the score, is the product of the two individual components:

This multiplicative design ensures that the overall score is significantly affected by deficiencies in either spatial positioning or heading alignment. Consequently, high scores are only achieved by behaviors that simultaneously reach the goal vicinity and exhibit appropriate orientation, reflecting the practical demands of embodied navigation tasks.

Although binary success metrics remain standard due to their simplicity, they often impose rigid thresholds that overlook partial progress and intermediate competence. More importantly, success criteria are frequently underspecified or inconsistently applied, hindering reproducibility and comparability across studies. For example, a vehicle stopping 3 m from the goal with ideal orientation might be labeled a failure under a binary scheme, even though such performance may be functionally sufficient in many real-world contexts. In contrast, our proposed metric imposes a gradual penalty based on both spatial and angular deviation, resulting in a continuous score that better reflects the quality of the behavior.

A further strength of this metric lies in its adaptability. The distance threshold for full credit (e.g., 2.5 m in our experiments) can be tuned according to task granularity. Coarse-grained tasks such as room-level navigation may tolerate larger deviations, while fine-grained ones like object retrieval or docking may require tighter constraints. Similarly, heading sensitivity can be adjusted based on whether orientation is essential to task success. This parametrizability enhances the metric’s applicability across a wide range of embodied tasks and environments.

3.7. Other Evaluation Metrics

To assess the performance of the proposed approach, we evaluate the LLM plan using a set of quantitative and behavioral indicators. In addition to the Score introduced in the previous Subsection, we took advantage of:

- Iterations: measure the average number of reasoning–action cycles required to complete the task. Lower values indicate more efficient plans.

- Latency: captures the mean end-to-end response time for all reasoning steps, including image and point-cloud interpretation. This metric reflects the delay introduced by the interaction with the LLM.

- # JSON: counts malformed or incomplete structured outputs that violate the required action schema. Zero values indicate robust grounding of multimodal cues into coherent navigation commands.

- # Safety: represents the number of times the safety checker blocked an action that would have caused a collision. This quantifies planning reliability and safety awareness.

- Success: number of successful task completions out of twenty rollouts per scenario.

- Path Length: length in meters of the path planned by the LLM and followed by the UGV.

4. Results

The following Subsections present the experimental results of multimodal reasoning capabilities of LLMs, compare its performance against some baselines, and investigate how the model scale, the level of sensory abstraction, prompt engineering strategies, the inclusion of different sensing modalities, and the effect of memory influence the overall system performance.

4.1. Multimodal Reasoning Capabilities of LLMs for UGV Planning

To assess the impact of multimodal inputs on the reasoning and planning abilities of LLMs in UGV contexts, we benchmarked Gemini 2.0 Flash (Google DeepMind) on ten semantically and spatially diverse navigation tasks within the simulated factory environment. As anticipated, each task was executed twenty times, using five different starting positions, in a closed-loop control framework, where the LLM received visual and LiDAR context at each step to iteratively refine its plan.

Performance was quantified using the metrics introduced in Section 3.6 and Section 3.7. Table 1 summarizes the zero-shot performance across ten navigation and exploration tasks.

Table 1.

Gemini 2.0 Flash (Google DeepMind) Zero-Shot Performance on Navigation Tasks.

Across all tasks, the model exhibited robust multimodal grounding, reflected in the absence of JSON-formatting errors and its ability to consistently translate visual and LiDAR cues into structured action commands. Safety interventions were generally moderate, increasing only in the most challenging scenarios (e.g., Tasks 7 and 9), where environmental clutter or long-range occlusions complicated the spatial reasoning process. Latency varied widely across tasks, highlighting the delay introduced by the interaction with LLM, especially in scenes requiring deeper reasoning.

Task 6 demonstrates the model’s strongest capabilities, achieving a perfect success rate and score. This task requires only a 360° situational scan, and the model consistently selects the correct action sequence with minimal iterations, low latency, and no safety interventions. The result confirms that when the navigation problem reduces to straightforward perception alignment—without multi-step reasoning—the model can reliably ground the instruction in sensor data. Task 7 was also completed successfully across all episodes. However, because it involves generic free exploration without a specific target, the scoring metric does not apply (Score = N.A.). The model nevertheless maintained stable behavior, indicating that low-constraint exploratory tasks can be handled without significant drift or safety issues.

Good performance was additionally observed in Tasks 2, 3, and 8, which involve moderately structured spatial reasoning. These tasks yielded consistent successes (10–15) and the highest nontrivial scores in the dataset (0.34–0.47). Here, the model showed an ability to relate visual and LiDAR cues to goal descriptions even when the layout required limited inference about occluded regions or indirect object localization.

Tasks 5, 9, and 10 produced partial successes, with moderate task completions and low but non-zero scores. These scenarios included: (i) cluttered but structured environments, (ii) indirect or partially occluded goal positions, and (iii) mild spatial ambiguities requiring short multi-step reasoning. In these tasks, the model often generated plausible short-term motion suggestions but struggled to maintain consistency across multiple decision cycles, leading to increased safety interventions and failure to converge reliably on a correct long-horizon strategy.

Tasks 1 and 4 represent clear failure cases, despite their superficial simplicity in terms of layout. Task 1, which should have been trivial, resulted in very low scores due to inconsistent grounding of the goal location and unstable plan execution. Task 4 performed even worse, with near-zero scores and minimal successful episodes. Even when local movement suggestions were reasonable, the model frequently failed to form or sustain coherent long-horizon strategies, confirming the boundary of its zero-shot multimodal navigation capabilities.

These results somehow reflect the task difficulty taxonomy detailed in the previous section and indicate that multimodal inputs do improve LLM performance in zero-shot planning for navigation tasks, but only under conditions where the task complexity, environmental ambiguity, and perception-planning alignment are manageable. For tasks requiring deliberate spatial exploration, such as searching across the room or handling occluded targets, the LLM’s default reasoning process falls short. This highlights a critical limitation: while LLMs excel at commonsense reasoning and single-step decision-making, they lack built-in mechanisms for consistent spatial coverage or active exploration. LLMs should be equipped with standard exploration strategies, such as frontier-based or coverage-driven exploration algorithms, to better handle tasks that demand consistent and systematic environment traversal. Integrating these strategies would augment the LLM’s high-level decision-making with robust low-level exploration behaviors.

4.2. Comparison Between LLM-Generated Paths and Baselines Strategies

To better understand the efficiency of LLM-driven navigation, we compare the executed path length of the UGV with two baselines strategies. The Oracle represents the ideal trajectory: a direct, collision-free path from the starting pose to the target. The Frontier plus Shortest Path, instead, combines a classic frontier exploration strategy with a shortest-path planner, providing a strong algorithmic reference grounded in conventional robotic navigation techniques. Table 2 reports the corresponding results. For each task, we compute the average path length of the UGV, the Oracle path length, their ratio (UGV/Oracle), the Frontier plus Shortest Path path length, and their ratio (UGV/Frontier plus Shortest Path). A ratio of 1 indicates optimal behavior, while higher values reflect additional detours, oscillations, or inefficient turning patterns. It is worth noting that the comparison has been done only on successful tasks. Moreover, since tasks 6 and 7 do not include a target, they have excluded from the comparison.

Table 2.

Comparison of UGV and baselines (Oracle and Frontier plus Shortest Path) path lengths across navigation tasks, including the average ratio (UGV path/baseline path) as a measure of efficiency.

Tasks 1, 2, 4, and 5 exhibit ratios close to 1–2 relative to both baselines, indicating that in structurally simple scenarios the LLM can sometimes approximate efficient paths. These tasks mainly involve direct movement toward a clearly perceived target, which reduces ambiguity and allows the model’s decisions to align with the underlying shortest route.

For the majority of cases, Tasks 3, 8, 9, and 10, the UGV travels 2× to over 18× the optimal distance. This reflects the several weaknesses of LLM-based control, such as oscillatory movements, delayed or imprecise turning behavior, and difficulties interpreting spatial structure from multimodal input. These behaviors accumulate into substantial detours, explaining the inflated ratios.

Moreover, several tasks exhibit extremely large standard deviations (e.g., Task 1: ±76.93; Task 3: ±113.82; Task 8: ±212.50), signaling highly inconsistent behavior across trials. Such variability suggests that while the LLM may occasionally produce a nearly optimal sequence, it often diverges into inefficient or erratic paths.

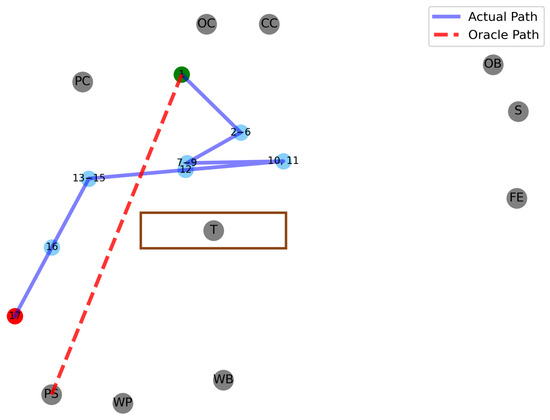

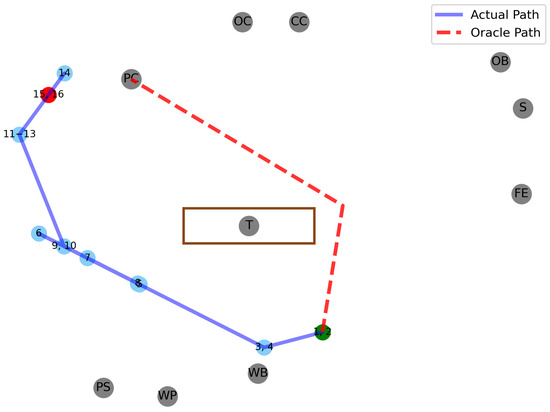

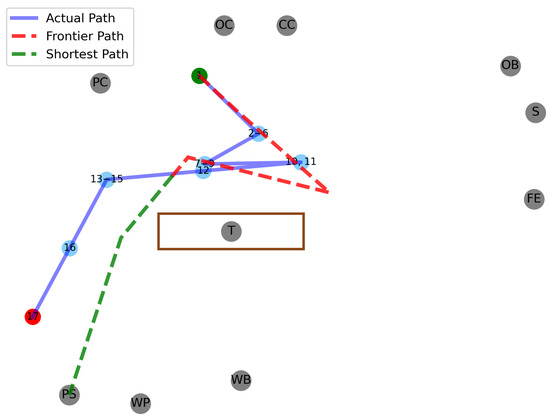

It is worth noting that in some cases (Tasks 2, 4, and 5), the average path length of the LLM is lower than the Frontier + Shortest Path baseline. This indicates that, despite its limitations, the LLM occasionally produces more direct or opportunistically efficient trajectories than a classical exploration-plus-planning pipeline. Such cases typically arise when the target is visually salient and directly interpretable from the LLM’s multimodal input, allowing it to select an efficient direction without engaging in the exploratory detours characteristic of frontier-based methods. These observations suggest that LLM-guided navigation can, at times, exploit scene semantics in ways that classical geometric strategies cannot, even if overall performance remains less consistent. To visualize these behaviors, Figure 5 and Figure 6 show representative trajectories for Tasks 1 and 2 compared with their respective Oracle paths, while Figure 7 and Figure 8 illustrate two examples on the same tasks of Frontier plus Shortest Path.

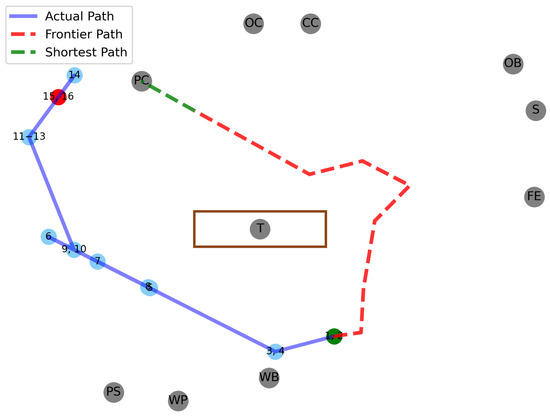

Figure 5.

Trajectory for Task 1. The green circle is the starting position. The red dashed line is the Oracle path. The solid blue line is the UGV path. The lightblue circles are intermediate steps. The red circle is the ending position. The numbers in the circles indicate the number of steps.

Figure 6.

Trajectory for Task 2. The green circle is the starting position. The red dashed line is the Oracle path. The solid blue line is the UGV path. The lightblue circles are intermediate steps. The red circle is the ending position. The numbers in the circles indicate the number of steps.

Figure 7.

Trajectory for Task 1. The green circle is the starting position. The red dashed line is the Frontier path, while the green dashed line is the shortest path. The solid blue line is the UGV path. The lightblue circles are intermediate steps. The red circle is the ending position. The numbers in the circles indicate the number of steps.

Figure 8.

Trajectory for Task 2. The green circle is the starting position. The red dashed line is the Frontier path, while the green dashed line is the shortest path. The solid blue line is the UGV path. The lightblue circles are intermediate steps. The red circle is the ending position. The numbers in the circles indicate the number of steps.

4.3. Ablation Study on Model Scale, Sensory Abstraction, Prompt Design, Sensing Modalities, and Memory Effect

To better understand which components most strongly influence the emergence of planning behaviors in LLM-driven navigation, we conduct a set of ablation studies targeting three key dimensions of the system: (i) the underlying model scale, (ii) the level of sensory abstraction applied to the LiDAR observations, and (iii) the structure and constraints embedded in the system prompt. These studies complement the main experiments by isolating how architectural choices (e.g., model size), perception encoding (number of LiDAR sectors), and prompt design (full vs. shortened instructions, with or without movement constraints) affect task completion, safety, and policy stability. The following subsubsections present the results of each ablation in isolation.

All ablation analyses were conducted using a representative task, chosen to balance difficulty and isolate the specific components under investigation. The ablations on model variation, system-prompt configuration, and history were performed on Task 3. This task belongs to the medium-difficulty category and, in our baseline experiments, Gemini 2.0 Flash (Google DeepMind) achieved 10 successful runs out of 20 with an average score of 0.41. This performance range provides sufficient room for both improvement and degradation, making Task 3 a suitable benchmark for evaluating changes in reasoning behavior induced by prompt structure or model choice.

In contrast, the ablation on LiDAR discretization was conducted on Task 8. Although Task 8 is also medium-difficulty, it offers several advantages for evaluating the effect of LiDAR resolution with respect to Task 3. First, Task 8 exhibits a strong dependence on spatial layout and geometric navigation: the robot must traverse a cluttered environment toward a distant set of visually similar boxes, making LiDAR information essential for identifying free space and avoiding obstacles. Second, the task typically generates longer trajectories with more intermediate directional decisions, increasing the sensitivity of the system to differences between 3, 5, and 8 angular LiDAR sectors. Third, Task 8 features a visually consistent and easily detectable target, reducing the influence of high-level visual ambiguity and ensuring that performance variations primarily reflect changes in LiDAR representation. For these reasons, Task 8 provides a more discriminative testbed for analyzing the contribution of LiDAR discretization to navigation performance.

4.3.1. Effect of Model Size on Zero-Shot Navigation Performance

To assess how the size of the foundational model impacts multimodal reasoning for navigation, we evaluated Gemini 2.0 Flash and its smaller variant Flash-Lite under identical simulation conditions and prompt configurations. Table 3 summarizes the performance across Task 8, varying the initial position five times.

Table 3.

Comparison of Gemini 2.0 Flash and Gemini 2.0 Flash-Lite in zero-shot multimodal navigation.

Overall, Gemini 2.0 Flash consistently outperformed Flash-Lite across all metrics, success rate, final-position score, and number of reasoning iterations, highlighting the importance of model capacity for maintaining coherent spatial reasoning over multiple decision cycles.

Across the five evaluated positions, Flash achieved higher success counts (10 vs. 7 in Flash-Lite) and substantially stronger final-position scores, particularly in Positions 1 and 4 (0.79 ± 0.30 and 0.63 ± 0.10), where the model successfully aligned perception with geometric constraints. In contrast, Flash-Lite frequently converged toward premature or incomplete plans, reflected in near-zero scores for Positions 2, 3, and 5. These failures illustrate the reduced model’s difficulty in maintaining consistent navigation hypotheses when spatial cues are ambiguous or require multi-step resolution.

Latency remained comparable across models, although Flash-Lite occasionally exhibited slightly higher variability. Importantly, neither model produced malformed outputs (#JSON = 0 across runs), and no safety triggers were activated, indicating that differences stem primarily from reasoning capability rather than output stability.

These findings show that larger models provide more robust planning, particularly in scenarios requiring iterative refinement or implicit spatial inference. Conversely, smaller models may suffice only when the required navigation behavior is simple, direct, or heavily grounded in the immediate sensory input.

4.3.2. LiDAR Discretization and Its Effect on Zero-Shot Spatial Reasoning

To assess the impact of perceptual granularity on the LLM-driven navigation pipeline, we evaluated three LiDAR discretization schemes, 3, 5, and 8 angular sectors, while keeping all other components (model, prompt, environment, and task set) fixed. Table 4 reports performance across the same five initial positions.

Table 4.

Effect of LiDAR discretization on LLM-based navigation performance using 3, 5, and 8 angular sectors.

A clear trend emerges: coarse LiDAR discretization (3 sectors) severely limits spatial reasoning, leading to near-zero success across most positions and consistently poor final-position scores. With only three directional bins, the model receives insufficient geometric structure to differentiate between obstacles, free-space directions, or relative target alignment. This often results in either ambiguous or oscillatory movement suggestions, and in one case, a triggered safety refusal.

Increasing the resolution to 5 sectors yields a noticeable improvement. Success counts rise across Positions 1–3, and the model produces moderately accurate final-position scores, particularly in Position 2 (0.45 ± 0.19) and Position 3 (0.24 ± 0.22). These results indicate that a mid-level discretization provides enough angular information for short-horizon spatial decisions, though performance remains inconsistent when tasks require precise directional disambiguation or multi-step corrections.

The 8-sector configuration consistently performs best, achieving the highest success counts and the strongest scores, including substantial gains in Positions 2 (0.46 ± 0.26) and 5 (0.65 ± 0.36). The richer angular structure allows the model to better infer free-space corridors, detect local minima, and align its motion plan with visually grounded target cues. However, performance is not uniformly superior: Position 3 exhibits lower scores despite correct outputs, suggesting that excessive discretization can occasionally introduce noise or lead to overfitting on short-range cues.

Overall, these results demonstrate that LiDAR granularity significantly influences the LLM’s capacity to maintain coherent spatial reasoning. While minimal discretization is insufficient for meaningful navigation, excessively fine segmentation does not guarantee uniform improvements. The 8-sector configuration offers the best overall balance, enabling the model to generalize more effectively across heterogeneous spatial layouts.

4.3.3. Impact of System Prompt Structure on Navigation Performance

The system prompt plays a central role in shaping how LLMs interpret sensor readings and generate sequential decisions. To assess its influence, we compare six configurations: (i) Full prompt (main-experiment version), (ii) Full prompt without movement constraints, (iii) Short prompt, (iv) Short prompt without movement constraints (v) a version in which the LiDAR interpretation guidelines are removed, and (vi) a Self-Check prompt in which the model must verify the validity of every JSON response before proceeding. The shorter prompt is reported in Listing 6.

| Listing 6. Shorter version of the System Prompt. |

|

The full prompt contains explicit behavioral rules, detailed reasoning instructions, and command-format requirements. The short prompt preserves only essential task information, substantially reducing descriptive guidance. In the constraint-free variants, we remove rule-based limitations regarding allowed movements, enabling the model to choose any action at each step. In the No LiDAR guidelines, we simply removed such guidelines from the system prompt. Finally, in the Self-Check experiments, the prompt reported in Listing 7 is sent to the LLM after each iteration.

| Listing 7. Self-Check Prompt. |

|

Table 5 reports performance across the same initial positions.

Table 5.

Performance comparison across four system-prompt configurations: full prompt, full prompt without movement constraints, short prompt, short prompt without movement constraints, the prompt without the LiDAR guidelines, and a safe-check mechanisms.

With regard to the prompt length, the comparison between the full and short prompts shows no substantial difference in terms of overall Success. Both prompts allow the models to reliably complete the simpler positions (1 and 4), while struggling similarly on the more challenging ones (3 and 5). This indicates that reducing descriptive detail in the prompt does not critically impair the model’s ability to reach the goal. However, differences emerge in the Score metric, where the full prompt generally produces more stable and higher-scoring trajectories. This suggests that the additional structure in the full prompt primarily improves trajectory quality and policy consistency, rather than ultimate task completion.

Instead, removing the movement constraints leads to a significant shift in navigation behavior. Across both the full and short prompts, eliminating constraints introduces substantial instability: success rates drop sharply in several positions (most prominently Position 2), and variance increases in iteration counts and latency. While unconstrained prompts occasionally achieve faster resolutions in easier scenarios (e.g., Position 1), they generally fail to generalize reliably.

This result is particularly interesting because it highlights the role of constraints as an implicit inductive bias, they help guide the LLM toward consistent and safe action patterns. When constraints are removed, the model gains flexibility but loses behavioral regularity, leading to erratic or unsafe strategies, especially in geometrically complex layouts.

Removing high-level instructions on how the model should use LiDAR depth-sector information drops dramatically the performance across all starting positions except Position 5, with no successful trajectories and consistently near-zero scores. This indicates that unlike general prompt detail, LiDAR-specific behavioral instructions are necessary for effective spatial reasoning. Without them, the model tends to ignore or misinterpret obstacle layout, leading to frequent collisions or dead-end movements. The strong decline highlights the importance of providing modality-specific priors when the task requires spatial grounding.

Finally, the Self-Check configuration exhibits a markedly different pattern from the other prompt variants. Rather than inducing a uniform drop in performance, it produces highly heterogeneous outcomes across positions. The model performs well in some settings (e.g., Position 4: , Position 1: ), moderately in others (Position 2: ), and nearly fails in Positions 3 and 5 (both approaching zero). This suggests that the additional verification step does not consistently hinder the navigation loop, but instead introduces substantial positional instability.

Three mechanisms likely contribute to this variability. First, the requirement to validate the correctness of each JSON message introduces additional cognitive load, and the degree to which this interferes with task execution appears to depend on the spatial structure and perceptual demands of each starting position [48]. Second, inserting a self-verification phase between perception and action disrupts the continuity of the control loop in a way that some configurations tolerate better than others, leading to inconsistent sensitivity to temporal fragmentation [49]. Third, alternating between agent mode (issuing navigation commands) and validator mode (returning CONFIRMED) introduces role-switching overhead that can either be absorbed or amplified depending on the spatial context and the required reasoning depth [50].

4.3.4. Impact of Sensing Modality

To assess the contribution of depth-aware geometric information to LLM-driven navigation, we compare two sensing configurations: the multimodal setup combining LiDAR and vision (used in all other experiments), and a vision-only baseline. The former provides the model with coarse geometric cues derived from sectorized LiDAR ranges, while the latter relies exclusively on image input. Table 6 summarizes quantitative results across all initial positions.

Table 6.

Comparison between multimodal (LiDAR+Vision) and vision-only sensing configurations across all initial positions.

Overall, the multimodal configuration demonstrates more robust performance. It achieves higher Success rates in four out of five positions and consistently yields higher trajectory Scores, indicating more stable, goal-directed motion. This advantage is most pronounced in Positions 1 and 2, where the addition of LiDAR appears to help the model avoid ambiguous or unsafe forward motions. In more challenging layouts (e.g., Position 3), both configurations struggle.

Interestingly, the vision-only system matches or marginally outperforms the multimodal setup in an isolated case (Position 4), where it achieves a near-optimal Score. This suggests that when visual structure is clear and the environment is free of occlusions, RGB cues alone may suffice for consistent navigation. However, the reduced Success in other positions highlights the susceptibility of the vision-only configuration to depth ambiguities, especially in cluttered or geometrically constrained layouts.

4.3.5. Effect of History Conditioning on Performance

In this ablation, we assess how different amounts of historical context influence the decision-making performance of the LLM. Four configurations are compared: providing no history, one previous step, two previous steps, or the full trajectory history. Note that, as anticipated, the full-history configuration is the one used in the experiments. The quantitative results are reported in Table 7.

Table 7.

Performance comparison varying the number of provided steps ahead: none, one, two, and all.

When no history is supplied, the model must rely exclusively on the current multimodal observation. This often leads to short-sighted or inconsistent behaviours, reflected by generally low scores and limited task success. Supplying one or two previous steps results in small improvements for certain tasks, but the impact remains limited and unstable across the entire benchmark.

The best performance is achieved when conditioning on the full trajectory history. This setting enables the LLM to maintain coherent long-horizon plans, recover from ambiguous states, and interpret the evolution of its past actions and observations. Notably, success rates increase substantially for Tasks 1, 2, and 4, confirming that temporal context is crucial for robust navigation and reasoning.

5. Discussion and Limitations

This Section is structured into three parts. The first one analyzes the performance of the multimodal planning framework and the insights gained from the ablation studies, identifying the current state and limitations of LLM-driven control. Then, the extensibility of the proposed architecture to other resource-constrained systems, particularly aerial vehicles, is discussed. Finally, the last part highlights the critical responsible use and safety considerations necessary for the ethical development of this technology.

5.1. Multimodal Planning Performance and Insights from Ablation Studies

The experimental findings indicate that while LLM equipped with multimodal inputs can reason about spatial goals and produce contextually grounded navigation decisions, their current performance in the proposed proof-of-concept settings remains very limited. The models demonstrated intermittent success in structured and visually salient tasks but failed to exhibit consistent reliability or robustness across diverse navigation scenarios. This inconsistency highlights that LLMs, in their current form, are far from achieving the level of dependable autonomy required for real-world UGV deployment.

The continuous evaluation metric employed in this study provides additional perspective on these shortcomings. While it reveals nuanced improvements in partial goal attainment, the relatively low average scores across tasks suggest that even when the LLM-driven UGV approached the correct region, it frequently failed to achieve precise alignment or complete the intended maneuver. This confirms that current LLMs can simulate goal-directed behavior but lack the fine-grained spatial control and consistency required for fully autonomous operation.

From a systems perspective, these results underscore that LLMs should presently be regarded as high-level reasoning components rather than self-sufficient controllers. Their value lies in semantic understanding and task generalization, abilities that complement but do not replace the robustness of traditional control and planning methods. The integration with model predictive control-based planners or established heuristic and AI-driven path planning algorithms could provide the necessary stability and safety guarantees for practical UGV deployment.

Ultimately, this work exposes both the promise and the fragility of language-driven autonomy. The findings highlight that while multimodal LLMs can interpret goals, generate coherent high-level plans, and demonstrate emergent spatial reasoning, these capabilities are embryonic and heavily constrained by the absence of structured perception–action coupling. Future efforts must therefore move toward hybrid architectures that combine symbolic reasoning, probabilistic mapping, and physically grounded control to bridge the gap between linguistic intelligence and embodied autonomy.

5.2. Extending the Framework to Aerial and Resource-Constrained Systems

While our experiments are conducted on a UGV platform, the proposed closed-loop architecture, composed of the Adapter, Controller, and multimodal LLM, is not inherently limited to ground vehicles. Because the methodology abstracts perception into structured visual and LiDAR representations and constrains actuation to a small set of high-level motion primitives, the framework generalizes naturally to other unmanned systems, including aerial drones and surface vehicles. In these platforms, high-level semantic reasoning, target-driven navigation, and iterative perception–action cycles remain central tasks, and can similarly benefit from an LLM-based decision layer.

However, deploying such architectures on UAVs introduces challenges not present in ground systems. UAVs require significantly tighter real-time control loops, must operate within stringent power and compute budgets, and often depend on continuous stabilization and low-latency perception. These constraints exacerbate the limitations we observed in our study: the sequential reasoning pipeline, repeated calls to a large model, and high-dimensional multimodal inputs contribute to latency and make on-board execution difficult.

Nevertheless, the findings of this work suggest a promising direction for future drone applications when viewed through the lens of hybrid and distributed architectures. The system we propose already separates high-level reasoning from platform-specific execution. This decoupling can be extended to UAVs in two ways. In the former, distilled or quantized multimodal LLM variants could run onboard to handle local reasoning steps such as object recognition, short-horizon maneuvers, or task disambiguation. Since our Adapter already converts sensor data into compact structured summaries, these distilled models would not need to process raw, high-resolution imagery, reducing compute requirements. In the latter, more complex reasoning (e.g., semantic map interpretation, mission-level planning, or multi-step strategy generation) could be offloaded to a ground station or cloud endpoint. The iterative loop used in our methodology is naturally compatible with such distributed execution: the Controller maintains local stability while the LLM provides periodic high-level updates as bandwidth allows.

5.3. Responsible Use and Safety Considerations

For ethical reasons, we emphasize that the framework presented in this paper is currently constrained to a high-fidelity simulated environment (Webots). All experiments were conducted safely and non-harmfully within this controlled setting, with no risk to human or physical safety. The primary goal of this research is to advance the understanding of LLMs in complex, multi-modal planning. Should future work involve the deployment of this architecture onto physical robotic platforms, stringent safety protocols must be enforced. We commit that any future physical implementation will include a robust human-in-the-loop oversight system and clear geofencing or operational constraints to mitigate the risk of misuse or unintended harm, ensuring the technology is developed strictly for beneficial, constructive purposes.

5.4. Limitations

While the proposed framework demonstrates the feasibility of using LLMs for zero-shot planning in autonomous mobile robots UGVs, several limitations remain that constrain its generalization and real-world applicability.

First, the generalizability of these results remains constrained by several factors. All experiments were conducted within a simulated environment using Webots. Although simulation provides a controlled and repeatable testbed for benchmarking, it cannot fully capture the complexity, noise, and uncertainty of real-world UGV deployments. Factors such as imperfect sensor calibration, dynamic obstacles, uneven lighting, and latency in control loops could significantly affect the performance of an LLM-driven navigation pipeline. Moreover, the tasks were limited to a single platform and a relatively small set of navigation goals, restricting the diversity of contexts from which to infer general principles. Finally, all models were evaluated in a purely zero-shot configuration—an approach that highlights emergent reasoning capabilities but underrepresents performance that might be achievable through fine-tuning or task-specific adaptation. Consequently, while the observed behaviors provide valuable insight into the potential of multimodal LLMs for embodied reasoning, their generalizability to other platforms, domains, and sensory configurations should be regarded as preliminary.

Second, the current system architecture relies on a sequential perception–reasoning– action loop that introduces latency due to repeated LLM inference. This design, while interpretable and modular, limits real-time responsiveness, especially when reasoning over high-dimensional multimodal inputs such as visual frames and LiDAR scans. Future implementations could benefit from lightweight on-board inference or hybrid schemes combining fast local control policies with cloud-based reasoning.

Third, the LLMs employed in this study, Gemini 2.0 Flash and Gemini 2.0 Flash-Lite (Google DeepMind), were evaluated in a purely zero-shot setting. Although this choice highlights the models’ inherent reasoning abilities, it also exposes their instability in maintaining spatial consistency across steps. The lack of explicit memory or spatial grounding can lead to incoherent or repetitive actions over longer trajectories. Fine-tuning, reinforcement learning with feedback, or the integration of structured world models could mitigate these limitations.

Fourth, the study considered only vision and LiDAR as sensing modalities. While these are sufficient for planar navigation tasks, more complex outdoor UGV scenarios would require richer perceptual inputs such as stereo or depth cameras, inertial sensors, or GPS. Integrating these additional modalities could improve robustness and allow for deployment in less structured environments.

Then, while our current study validated the impact of model size (Gemini 2.0 Flash vs. Lite), a comprehensive, tier-matched comparison across different model families (e.g., state-of-the-art open-source LLMs) remains essential to confirm the universality of our performance findings. This will allow for conclusions regarding architectural strengths versus mere model capacity.

Finally, the current evaluation metric, while capturing distance and orientation accuracy, does not fully account for qualitative aspects of behavior such as smoothness, efficiency, or task completion time. Future evaluations could incorporate additional metrics that reflect the overall autonomy and operational safety of the UGV in real-world missions.

Despite these limitations, this work establishes a foundation for integrating LLM-based reasoning into multimodal robotic control architectures, highlighting both the promise and the challenges of achieving general-purpose autonomy through language-driven planning.

6. Conclusions and Future Works

This paper explored the use of LLMs for zero-shot planning for navigation and exploration in simulated environments through multimodal reasoning. We proposed a modular architecture that combines LLMs with visual and spatial feedback and introduced a novel metric that jointly considers distance and orientation, enabling finer-grained performance evaluation than binary success rates.

Our findings show that Gemini 2.0 Flash (Google DeepMind), with access to multimodal input, demonstrated promising spatial-semantic reasoning. These results highlight the potential of recent multimodal LLMs to bridge high-level instruction following and embodied execution.

The proposed metric proved especially useful for capturing partial progress in tasks with ambiguous or hard-to-define success conditions, offering a more robust and interpretable measure of behavior in zero-shot scenarios.

Building on these encouraging results, several directions merit further investigation. First, fine-tuning LLMs with robot-centric data, such as embodied trajectories, simulated rollouts, or multimodal instructional datasets, may significantly boost their spatial reasoning and goal-directed behavior. Similarly, hybrid systems that combine LLM reasoning with classical exploration strategies (e.g., frontier-based or SLAM-driven navigation) may provide the robustness and structure required for more complex tasks. Second, improving the richness and format of perceptual inputs—through structured scene representations, learned affordances, or persistent memory—could better support long-horizon reasoning and improve generalization across environments. Then, the comparison with a robotics-fine-tuned model, such as Gemini Robotics [51], or combining the LLM with a vision preprocessor would allow for a more nuanced analysis of how specialized knowledge (fine-tuning) or enhanced perception (preprocessor) specifically influences the robustness and efficiency of complex robotic planning tasks, separating the effects of general LLMs reasoning from domain-specific capabilities. Finally, an essential step forward is the deployment and validation of these systems in real-world scenarios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.P. and P.S.; methodology, G.D.; software, K.O.; investigation, C.-T.L., G.P. and P.S.; writing—original draft preparation, K.O. and G.D.; writing—review and editing, G.P. and P.S.; supervision, G.P. and P.S.; project administration, C.-T.L.; funding acquisition, C.-T.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the authors used ChatGPT (GPT-4o) for the purposes of writing assistance. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| DRL | Deep Reinforcement Learning |

| HRI | Human-Robot Interaction |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| SLAM | Simultaneous Localization And Mapping |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| UGV | Unmanned Ground Vehicle |

| VLFM | Vision-Language Frontier Maps |

| VLM | Vision-Language Model |

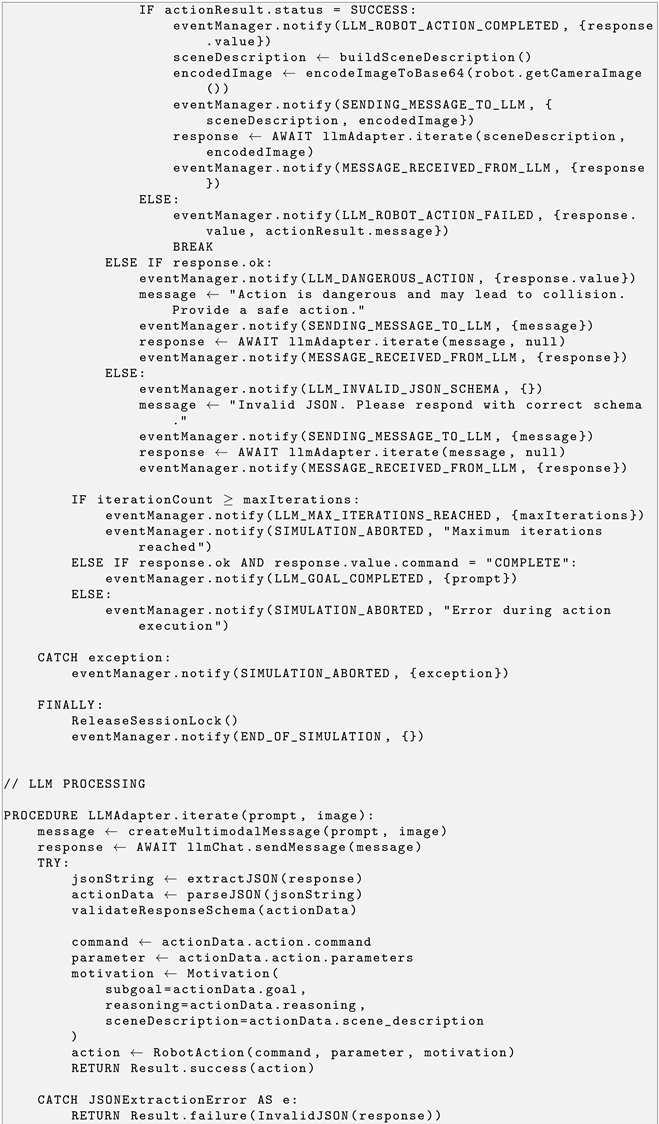

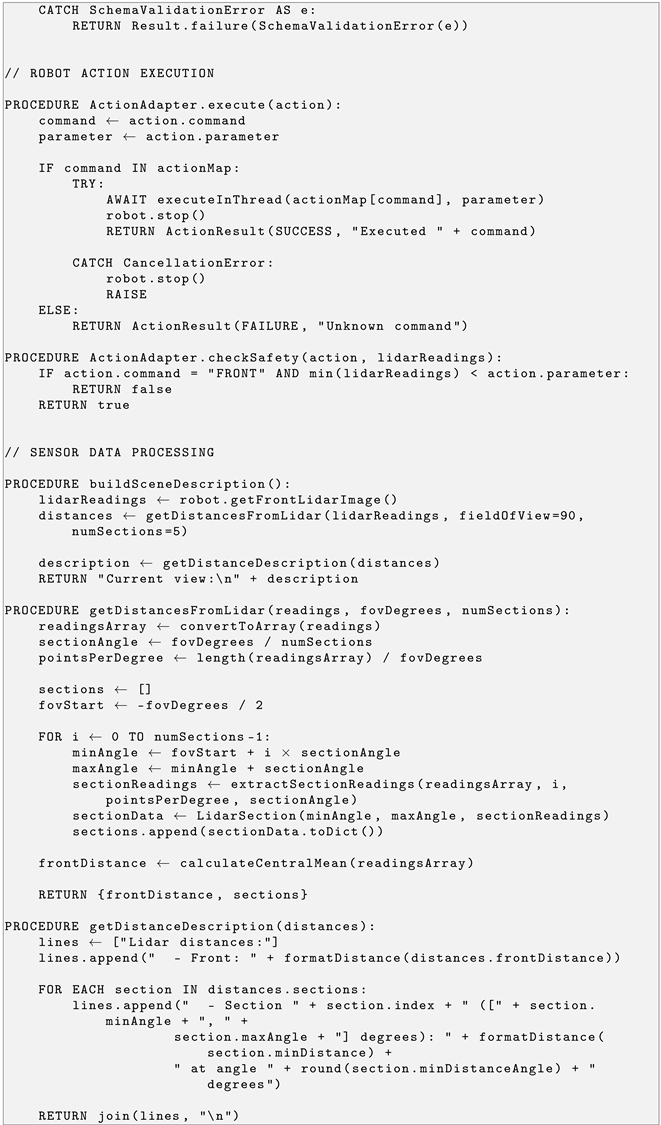

Appendix A

| Listing A1. Pseudocode of LLM-Based UGV Control System. |

|

|

|

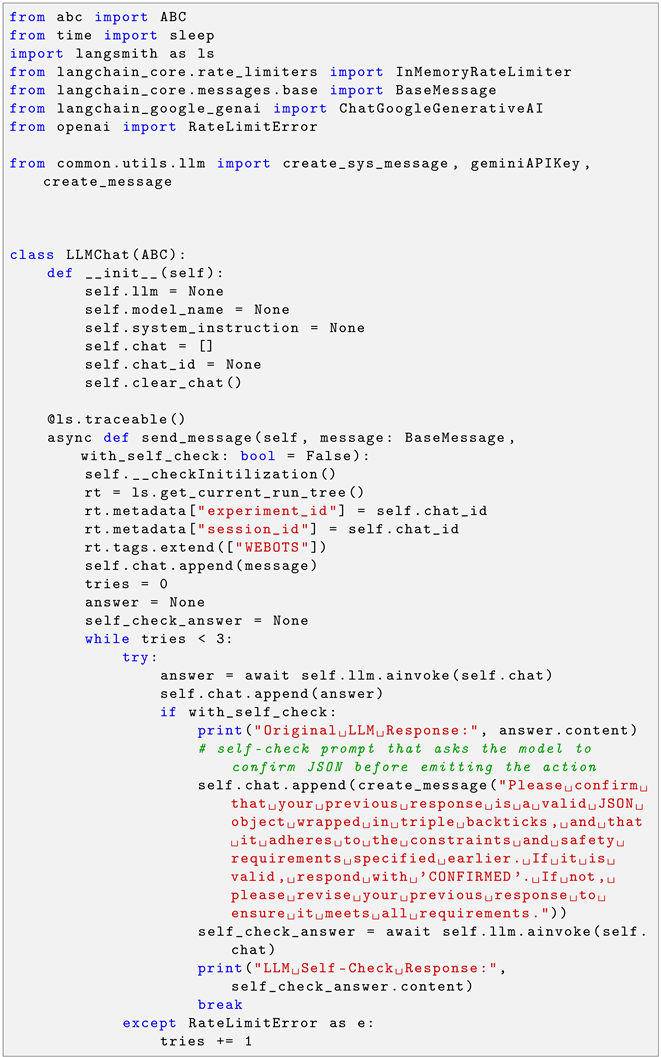

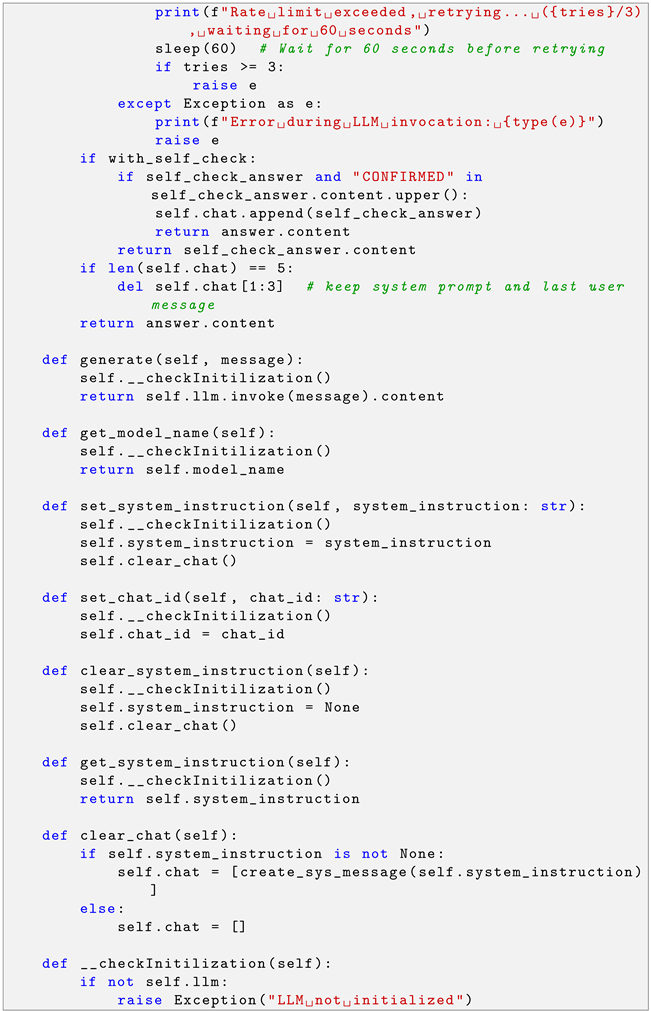

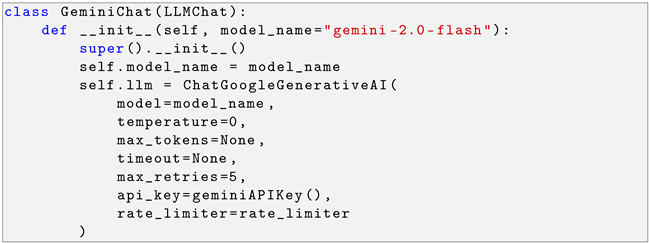

Appendix B

| Listing A2. Python 3.12.2 classes that handles the asynchronous communication with the Gemini model, taking advantage of LangChain platform. |

|

|

|

References

- Kawaharazuka, K.; Matsushima, T.; Gambardella, A.; Guo, J.; Paxton, C.; Zeng, A. Real-world robot applications of foundation models: A review. Adv. Robot. 2024, 38, 1232–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhu, Y.; Kato, K.; Tsukahara, A.; Kondo, I.; Aoyama, T.; Hasegawa, Y. Enhancing the LLM-Based Robot Manipulation Through Human-Robot Collaboration. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 6904–6911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Huang, S.; Pompili, D. LLM-Based Multi-Agent Decision-Making: Challenges and Future Directions. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2025, 10, 5681–5688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Li, D.; A, Y.; Shi, J.; Hao, P.; Sun, F.; Zhang, J.; Fang, B. RobotGPT: Robot Manipulation Learning From ChatGPT. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 2543–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, E.; Zhao, Z.; Guo, Y.; Wong, K.Y.K.; Li, Z.; Zhao, H. DriveGPT4: Interpretable End-to-End Autonomous Driving Via Large Language Model. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 8186–8193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Chen, J.; Li, J.; Peng, Y.; Mao, Z. Large language models for human–robot interaction: A review. Biomim. Intell. Robot. 2023, 3, 100131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]