UAV LiDAR-Based Automated Detection of Maize Lodging in Complex Agroecosystems

Highlights

- UAV LiDAR point cloud stratification and structural similarity analysis enable automatic height threshold selection, capturing lodging-induced canopy differences with only 2.3% deviation between monitored and manually measured lodging.

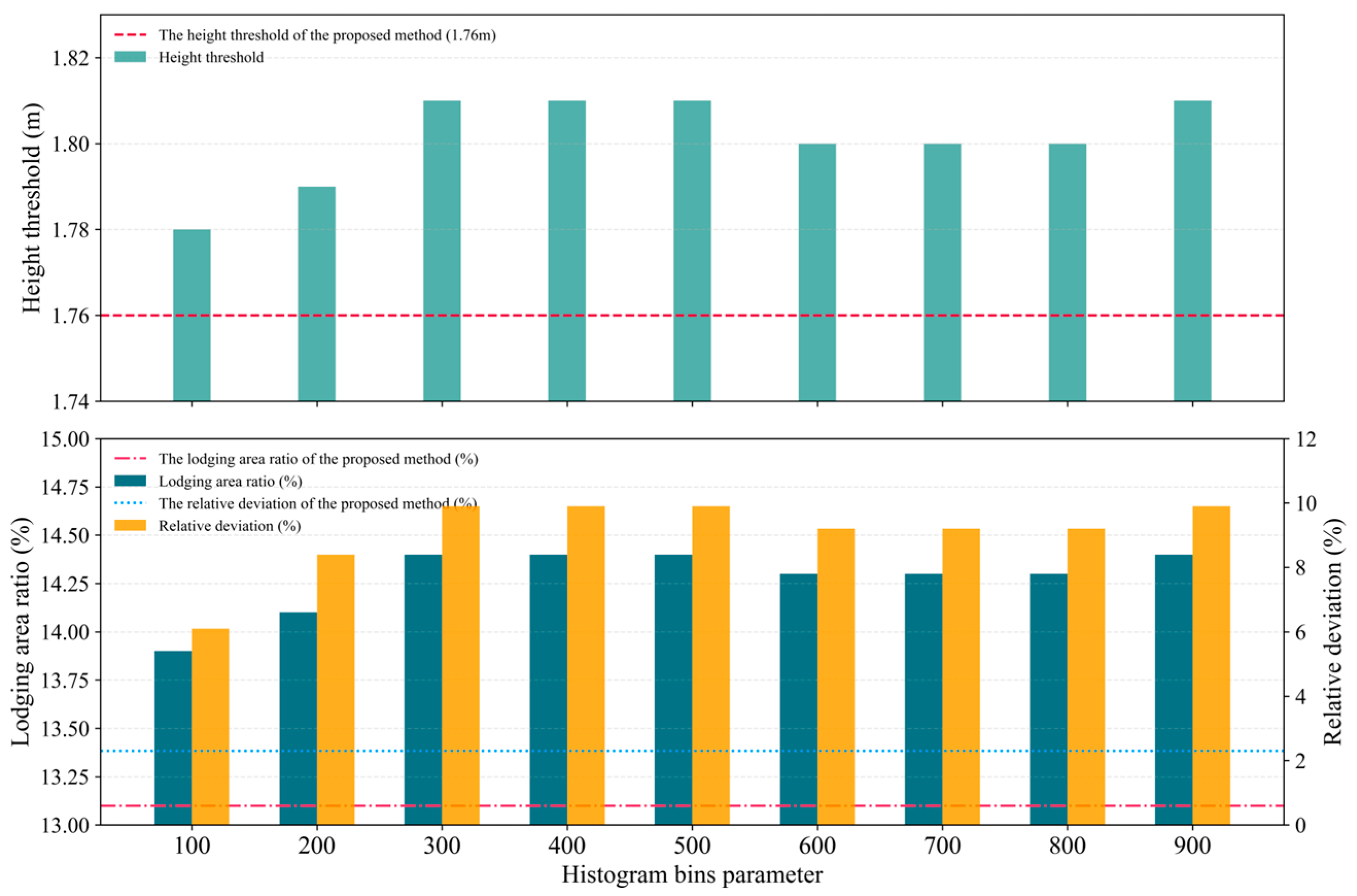

- The automatically selected height threshold shows strong robustness: ±5 cm fluctuations result in <10% deviation in lodging area estimation, verifying the scheme’s reliability.

- This intelligent monitoring technology provides an innovative solution for accurate maize lodging detection in complex, multi-variety and high-density planting environments.

- The method highlights UAV LiDAR’s application potential in agricultural monitoring, enabling extrapolation of low-altitude-derived thresholds to other high-altitude scenarios with minimal deviation (5.3%).

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

2.2. Image Collection from UAV Platforms

2.3. Implementation of the Adaptive Height Threshold Algorithm

3. Results

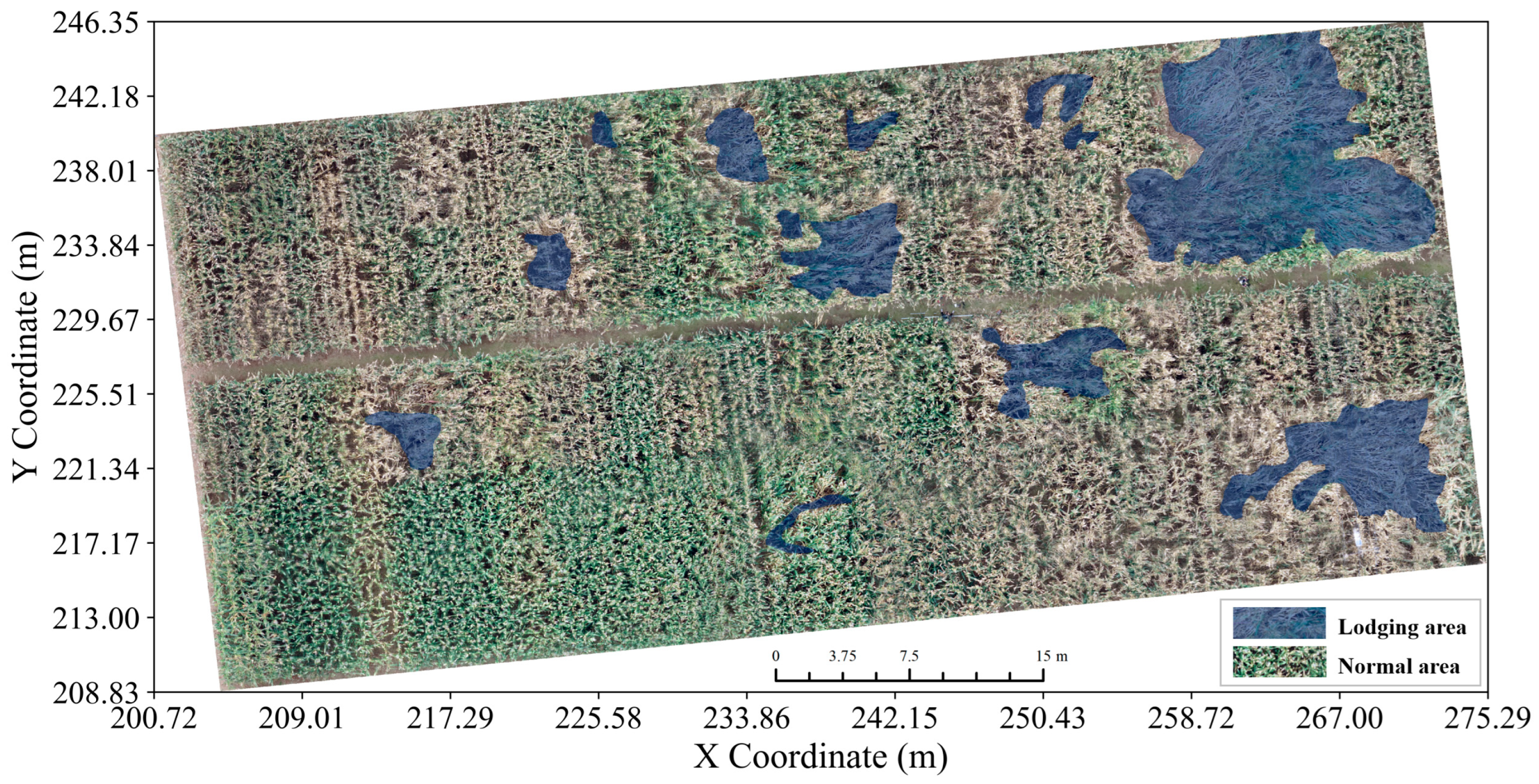

3.1. Analysis of Lodging Situation in the Study Area

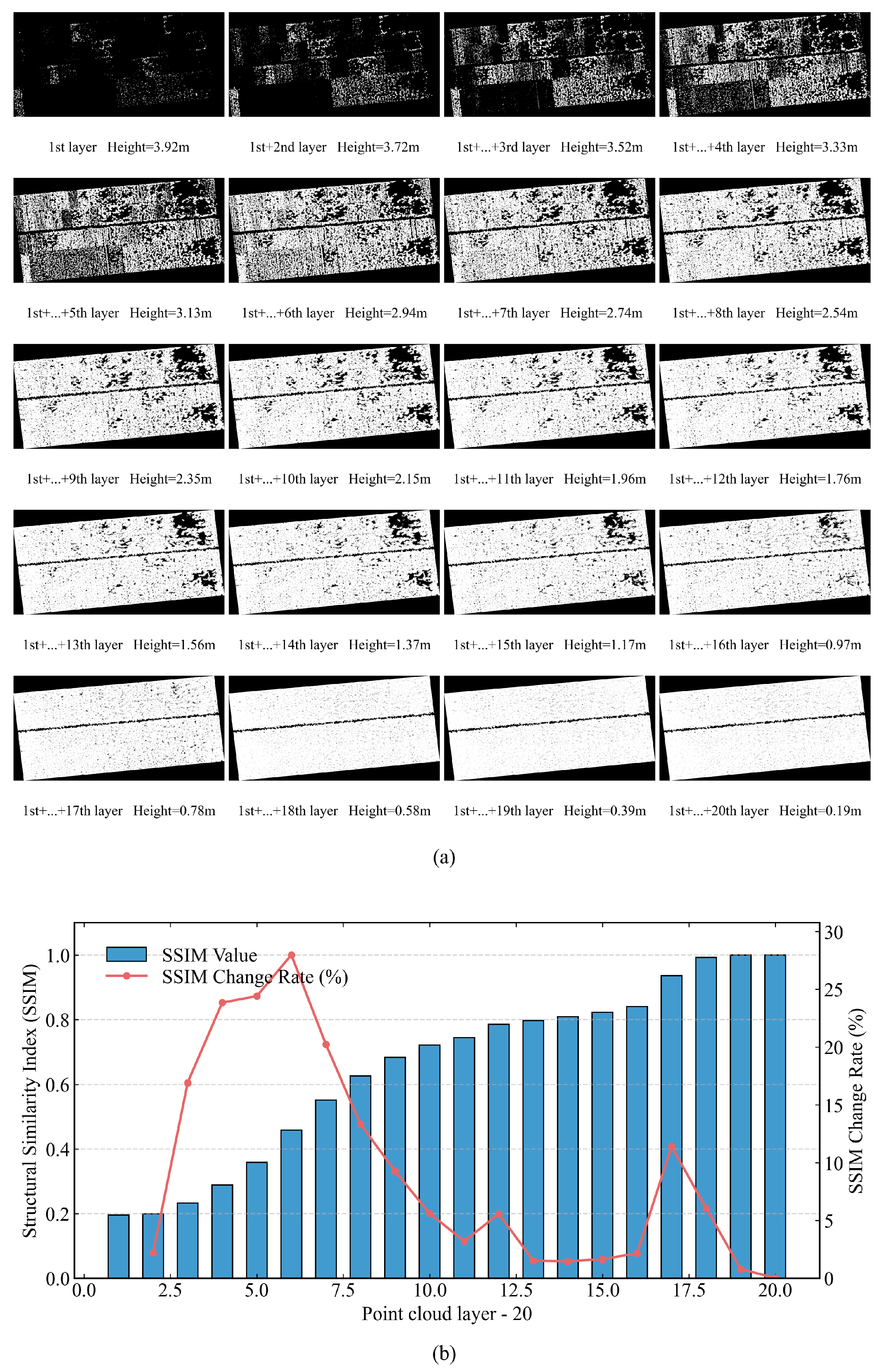

3.2. Automated Selection of Height Thresholds

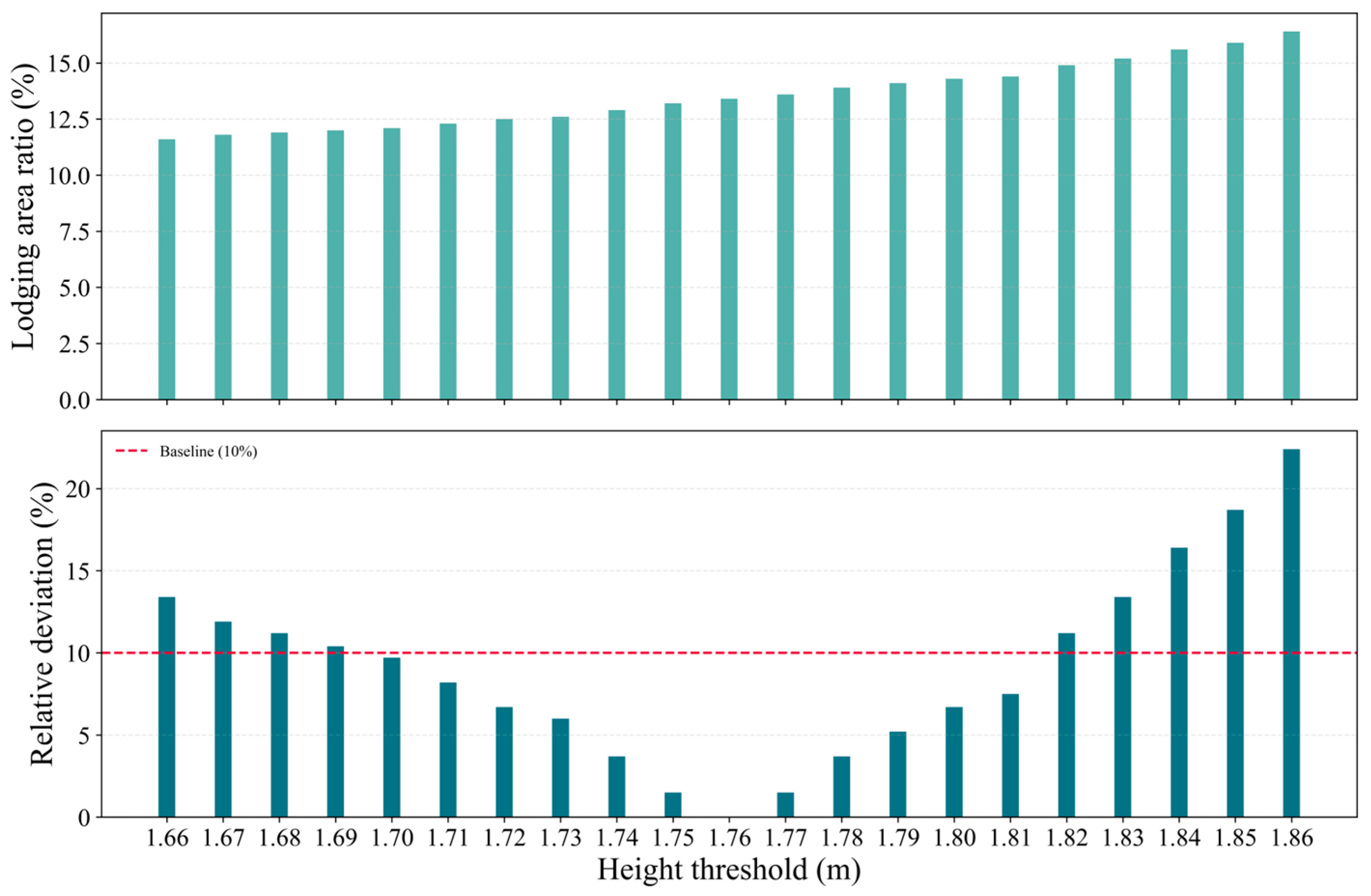

3.3. Quantitative Assessment of Lodging Area

3.4. Height Threshold Sensitivity Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Accuracy Analysis of the Proposed Method

4.1.1. Comparison with the Accuracy Results Obtained Through Manual Interpretation

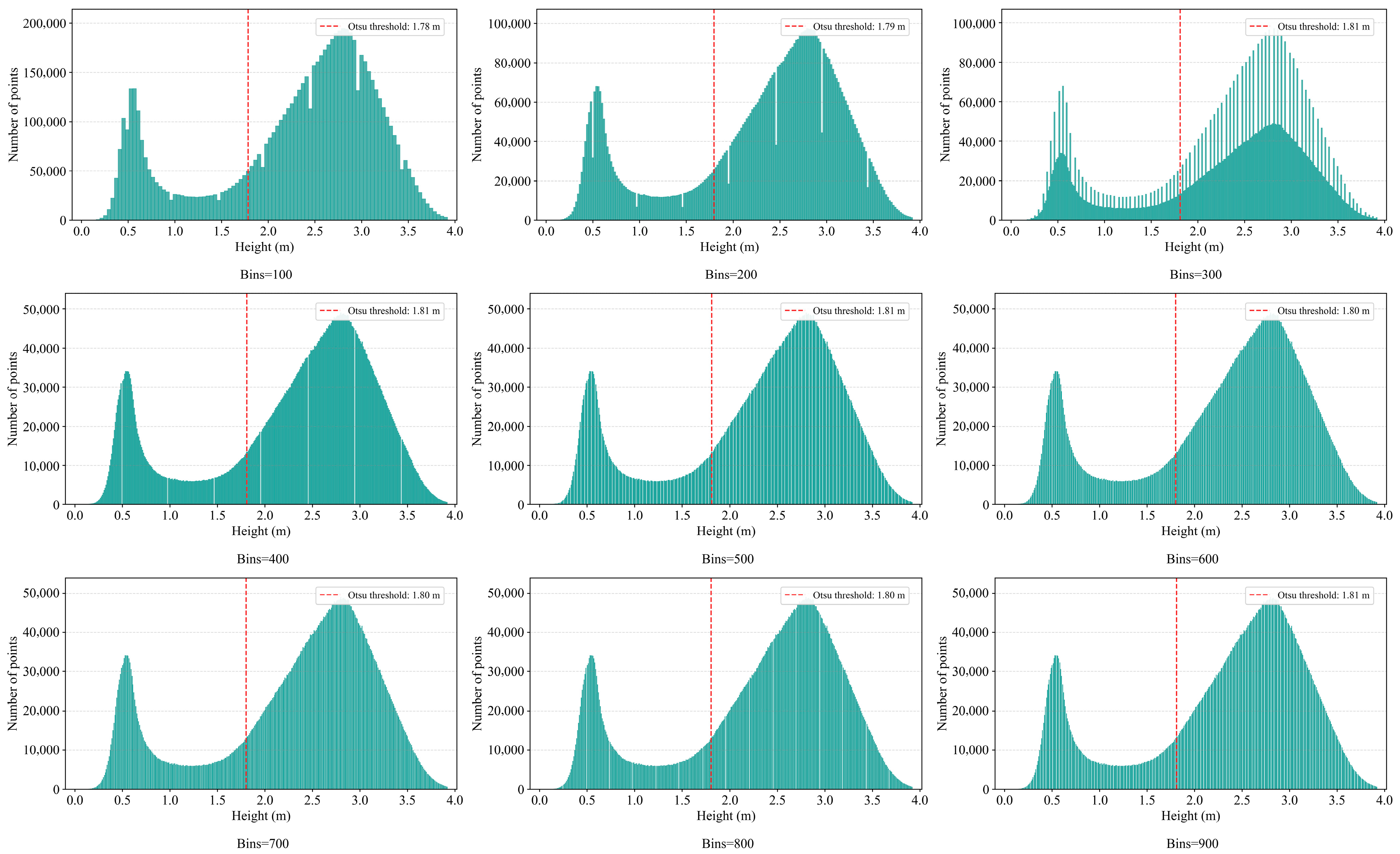

4.1.2. Comparison and Analysis with the Classic Threshold Selection Schemes

4.2. The Influence of Point Cloud Layering Parameters on the Accuracy Results

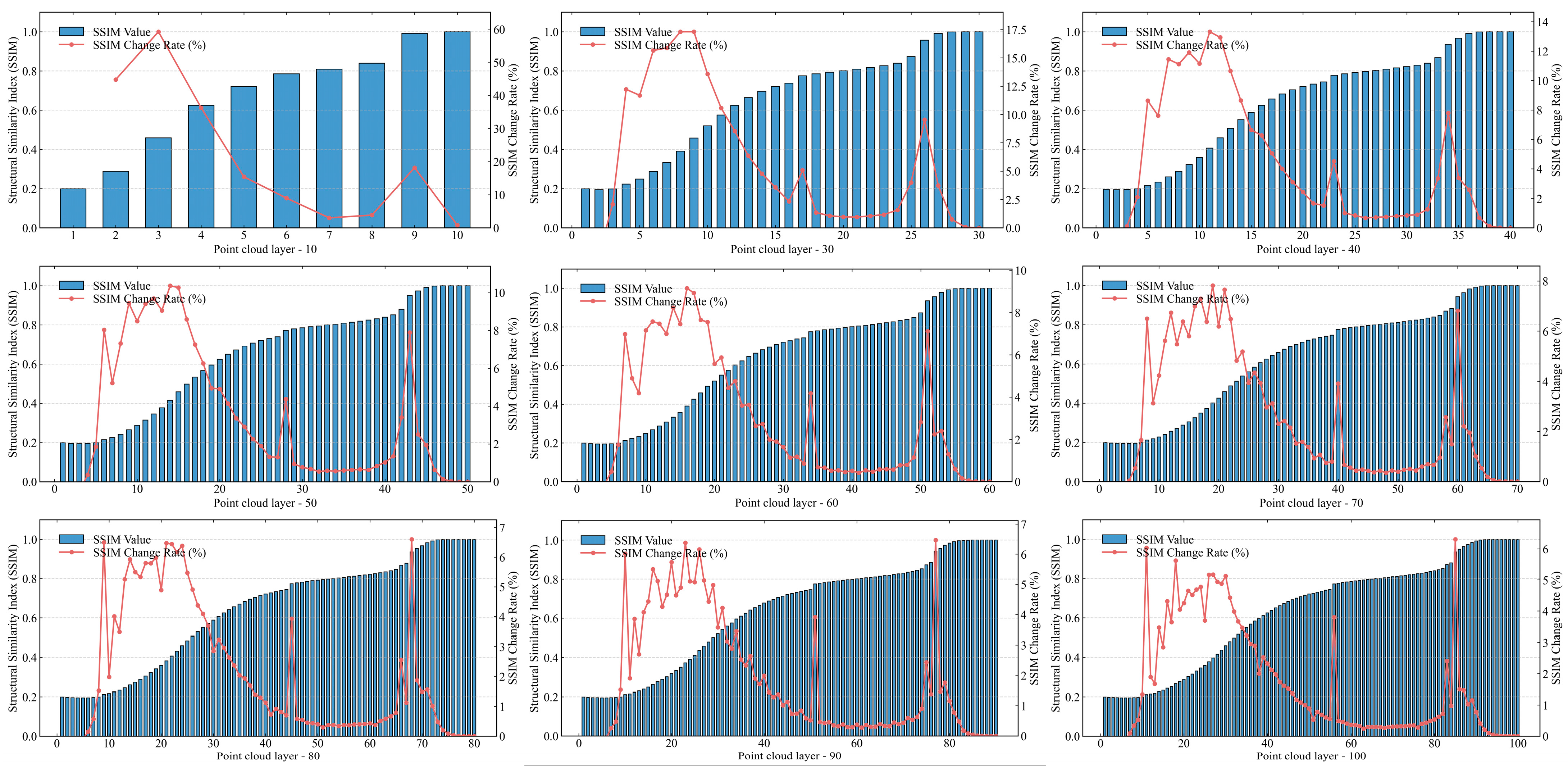

4.3. The Effect of UAV Flight Altitude on Lodging Monitoring Using Point Cloud Data

4.3.1. Research on the Accuracy of Height Threshold Monitoring Under Low Spatial Resolution

4.3.2. Research on the Transferability of Height Threshold Under Low-Altitude Flight Pre-Training

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions of This Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wei, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, D.; Zhao, C.; Guga, S.; Guo, Y.; Liu, X.; Tong, Z. Comprehensive risk fine dynamic assessment and zoning of maize high wind lodging disasters in Jilin Province, China. Eur. J. Agron. 2025, 170, 127710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Nie, C.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Ming, B.; Xue, J.; Yang, H.; Xu, H.; Meng, L.; Cui, N.; et al. Evaluating how lodging affects maize yield estimation based on UAV observations. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 979103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Gu, S.C.; Wang, Y.Y.; Xu, C.C.; Zhao, Y.T.; Liu, X.L.; Wang, P.; Huang, S.B. The relationships between maize (Zea mays L.) lodging resistance and yield formation depend on dry matter allocation to ear and stem. Crop J. 2023, 11, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, H.M.; Wang, Z.Z.; Sun, L.F.; Huang, Y.; Song, Y.F.; Zhang, R.; Wu, Z.J.; Fu, K.X.; Duan, J.Z.; Kang, G.Z.; et al. Optimizing nitrogen fertilization and planting density management enhances lodging resistance and wheat yield by promoting carbohydrate accumulation and single spike development. Crop Sci. 2024, 64, 3461–3479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Batyrbek, M.; Ikram, K.; Ahmad, S.; Kamran, M.; Misbah; Khan, R.S.; Hou, F.J.; Han, Q.F. Nitrogen management improves lodging resistance and production in maize (Zea mays L.) at a high plant density. J. Integr. Agric. 2023, 22, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Meng, X.; Yang, S.; Yang, J.; Li, Z.; Yang, Q.; Zheng, P.; Shao, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L. A simple method for lodging resistance evaluation of maize in the field. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1087652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, G.L.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, X.M.; You, N.S.; Li, Z.C.; Tang, H.; Yang, T.; Di, Y.Y.; Dong, J.W. Coupling GEDI LiDAR and Optical Satellite for Revealing Large-Scale Maize Lodging in Northeast China. Earths Future 2024, 12, e2023EF003590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Bhattacharya, B.K.; Pandya, M.R.; Handique, B.K. Machine learning based plot level rice lodging assessment using multi-spectral UAV remote sensing. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 219, 108754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.Q.; Wang, C.; Wang, A.C.; Gao, Y.Y.; Zhou, Y.A.; Huang, S.; Luo, B. Segmentation of Wheat Lodging Areas from UAV Imagery Using an Ultra-Lightweight Network. Agriculture 2024, 14, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, S.; Darvishzadeh, R.; Boschetti, M.; Pepe, M.; Nelson, A. Remote sensing-based crop lodging assessment: Current status and perspectives. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2019, 151, 124–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Song, F.; Sun, J. The application of UAV technology in maize crop protection strategies: A review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 237, 110679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, M.Y.; Bai, K.; Meng, L.; Yang, X.H.; Li, B.G.; Ma, Y.T. Assessing maize lodging severity using multitemporal UAV-based digital images. Eur. J. Agron. 2023, 144, 126754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Chen, L.; Xu, X.; Gu, X.; Hu, X.; Yang, F.; Pan, Y. A new comprehensive index for monitoring maize lodging severity using UAV-based multi-spectral imagery. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 202, 107362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhu, S.; Yang, T.; Zhang, W.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, K.; Wu, W.; Zhao, Y.; Yao, Z.; Yang, G.; et al. Maize height estimation using combined unmanned aerial vehicle oblique photography and LIDAR canopy dynamic characteristics. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 218, 108685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Li, Z.; Yang, G.; Yang, H. High-Throughput Extraction of the Distributions of Leaf Base and Inclination Angles of Maize in the Field. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 4411228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Yang, F.; Wei, H.; Liu, X. Individual Maize Location and Height Estimation in Field from UAV-Borne LiDAR and RGB Images. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Flores, P.; Igathinathane, C.; Naik, D.L.; Kiran, R.; Ransom, J.K. Wheat Lodging Detection from UAS Imagery Using Machine Learning Algorithms. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Han, W.; Huang, S.; Ma, W.; Ma, Q.; Cui, X. Extraction of Sunflower Lodging Information Based on UAV Multi-Spectral Remote Sensing and Deep Learning. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.; Liu, H.; Meng, X.; Luo, C.; Bao, Y.; Ma, Y.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, X. A Quantitative Monitoring Method for Determining Maize Lodging in Different Growth Stages. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Sun, L.; Shu, M.; Gu, X.; Yang, G.; Zhou, L. Monitoring Maize Lodging Grades via Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Multispectral Image. Plant Phenomics 2019, 2019, 5704154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Wang, K.; Liang, D.; Tang, J. WLUSNet: A lightweight wheat lodging segmentation network based on UAV image. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 237, 110587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhao, M.; Li, Z.; Xu, S.; Wu, X.; Ma, X.; Liu, X. A survey of unmanned aerial vehicles and deep learning in precision agriculture. Eur. J. Agron. 2025, 164, 127477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Qiao, Z.; Gao, Z.; Lu, S.; Tian, F. Use of unmanned aerial vehicle imagery and a hybrid algorithm combining a watershed algorithm and adaptive threshold segmentation to extract wheat lodging. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2021, 123, 103016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Su, Y.; Gao, S.; Wu, F.; Hu, T.; Liu, J.; Li, W.; Wang, D.; Chen, S.; Jiang, Y.; et al. Deep Learning: Individual Maize Segmentation from Terrestrial Lidar Data Using Faster R-CNN and Regional Growth Algorithms. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, L.; Wang, X.Y.; Yu, C.; Ye, C.Y.; Yan, Y.Y.; Wang, H.S. What factors control plant height? J. Integr. Agric. 2024, 23, 1803–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.H.; Chen, S.D.; Zhou, B.; He, H.X.; Zhao, Y.J.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, X.X. Multitemporal Field-Based Maize Plant Height Information Extraction and Verification Using Solid-State LiDAR. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasuriya, N.; Guo, Y.; Hu, W.; Ghannoum, O. Machine vision based plant height estimation for protected crop facilities. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 218, 108669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, X.; Igathinathane, C.; Xing, J.; Saha, C.K.; Sheng, W.; Li, H.; Zhang, M. Comprehensive wheat lodging detection under different UAV heights using machine/deep learning models. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 231, 109972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, C.; Wang, Z.; Liu, M.; Chen, J.; Zhang, H. Timely assessment of maize lodging severity with limited samples using multi-temporal Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 data across large spatial extents. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 237, 110671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xu, S.; Yang, C.; You, Y.; Zhang, J.; Kuai, J.; Xie, J.; Zuo, Q.; Yan, M.; Du, H.; et al. Determining rapeseed lodging angles and types for lodging phenotyping using morphological traits derived from UAV images. Eur. J. Agron. 2024, 155, 127104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Zheng, H.; Chen, J.; Chen, T.; Xie, P.; Xu, Y.; Deng, J.; Wang, H.; Sun, M.; Jiao, W. Integrating UAV, UGV and UAV-UGV collaboration in future industrialized agriculture: Analysis, opportunities and challenges. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 227, 109631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilke, N.; Siegmann, B.; Klingbeil, L.; Burkart, A.; Kraska, T.; Muller, O.; van Doorn, A.; Heinemann, S.; Rascher, U. Quantifying Lodging Percentage and Lodging Severity Using a UAV-Based Canopy Height Model Combined with an Objective Threshold Approach. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengistie, E.; McDonald, A.G. Effect of cell wall compositions on lodging resistance of cereal crops: Review. J. Agric. Sci. 2023, 161, 794–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madec, S.; Baret, F.; de Solan, B.; Thomas, S.; Dutartre, D.; Jezequel, S.; Hemmerlé, M.; Colombeau, G.; Comar, A. High-Throughput Phenotyping of Plant Height: Comparing Unmanned Aerial Vehicles and Ground LiDAR Estimates. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malambo, L.; Popescu, S.C.; Murray, S.C.; Putman, E.; Pugh, N.A.; Horne, D.W.; Richardson, G.; Sheridan, R.; Rooney, W.L.; Avant, R.; et al. Multitemporal field-based plant height estimation using 3D point clouds generated from small unmanned aerial systems high-resolution imagery. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2018, 64, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Gu, X.; Cheng, S.; Yang, G.; Shu, M.; Sun, Q. Analysis of Plant Height Changes of Lodged Maize Using UAV-LiDAR Data. Agriculture 2020, 10, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, T.X.; Starek, M.J.; Brewer, M.J.; Murray, S.C.; Pruter, L.S. Assessing Lodging Severity over an Experimental Maize (Zea mays L.) Field Using UAS Images. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.Q.; Gu, X.H.; Sun, Q.; Yang, Y.; Qu, X.Z.; Yang, X.; Guo, R. Comparison of the performance of Multi-source Three-dimensional structural data in the application of monitoring maize lodging. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 208, 107782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Sun, Q.; Che, X.H.; Chen, L.; Cui, Y.P.; Liu, J.; Wu, J.M.; Wang, T.; Li, H. Mapping rice lodging severity using dual-pol Sentinel-1 SAR data: Polarimetric parameters, lodging sensitivity, and fuzzy classification modelling. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2025, 46, 2748–2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Xuan, F.; Dong, Y.; Su, W.; Wang, X.; Huang, J.; Li, X.; Zeng, Y.; Miao, S.; Li, J. Identifying Corn Lodging in the Mature Period Using Chinese GF-1 PMS Images. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, D.M.; Wang, L.; Lu, Y.; Shi, C. Mangrove tree height growth monitoring from multi-temporal UAV-LiDAR. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 303, 114002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Wei, B.; Guan, H.; Yu, S. A method of calculating phenotypic traits for soybean canopies based on three-dimensional point cloud. Ecol. Inform. 2022, 68, 101524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.S.; Zhao, M.H.; Li, Z.L.; Wu, X.H.; Li, N.; Li, D.C.; Xu, S.; Liu, X.G. Classification of maize lodging types using UAV-SAR remote sensing data and machine learning methods. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 227, 109637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakurov, I.; Buzzelli, M.; Schettini, R.; Castelli, M.; Vanneschi, L. Structural similarity index (SSIM) revisited: A data-driven approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 189, 116087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiadi, D.I.M. PSNR vs SSIM: Imperceptibility quality assessment for image steganography. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 8423–8444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parent, J.R.; Witharana, C.; Bradley, M. Classifying and Georeferencing Indoor Point Clouds with ArcGIS. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2022, 88, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, R.G.; Wang, J.L. ArcFractal: An ArcGIS Add-In for Processing Geoscience Data Using Fractal/Multifractal Models. Nat. Resour. Res. 2020, 29, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Mittal, N.; Singh, H.; Oliva, D. Improving the segmentation of digital images by using a modified Otsu’s between-class variance. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 40701–40743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, J.W.; Yang, P.; Qingge, L.G. Robust 2D Otsu’s Algorithm for Uneven Illumination Image Segmentation. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2020, 2020, 5047976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Zhou, J.X.; Ji, X.Y.; Yin, Y.J.; Shen, X. An ameliorated teaching-learning-based optimization algorithm based study of image segmentation for multilevel thresholding using Kapur’s entropy and Otsu’s between class variance. Inf. Sci. 2020, 533, 72–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.L.; Huang, Y.W.; An, Z.K.; Zhang, H.; Han, Y.Y.; Zhao, Z.H.; Li, F.F.; Zhang, C.; Hou, C.C. Assessing radiometric calibration methods for multispectral UAV imagery and the influence of illumination, flight altitude and flight time on reflectance, vegetation index and inversion of winter wheat AGB and LAI. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 219, 108821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.Y.; Chen, Z.J.; Liao, A.L.; Zeng, X.T.; Cao, J.C. Accuracy analysis of UAV aerial photogrammetry based on RTK mode, flight altitude, and number of GCPs. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2024, 35, 106310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.Y.; Wang, Y.Q.; Guo, T.; Guo, C.L.; Wang, X.; Jiang, C.Y.; Cheng, T.; Zhu, Y.; Cao, W.X.; Chen, Q.; et al. Assessment of the influence of UAV-borne LiDAR scan angle and flight altitude on the estimation of wheat structural metrics with different leaf angle distributions. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 220, 108858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Maize Variety Name | Variety Abbreviation | Average Plant Height (cm) |

|---|---|---|

| MC 703 | A1 | 310 |

| Jiushenghe 2468 | A2 | 298 |

| Ruipu 909 | A3 | 286 |

| Xinyu 108 | A4 | 318 |

| Lianchuang 825 | A5 | 301 |

| Shandan 650 | A6 | 277 |

| Kehe 699 | A7 | 350 |

| Qiangsheng 388 | A8 | 332 |

| Xianyu 335 | A9 | 319 |

| Zhengdan 958 | A10 | 277 |

| Parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| Laser wavelength | 905 nm |

| Measurement rate | 320 kHz |

| Maximum range | 200 m |

| Field of view | 360° × ±15° |

| Echo number | 2 (first and last) |

| Range Accuracy | 2 cm |

| Resolution | Red Pixels | Total Pixels | Height Threshold | Proportion of Lodging Area | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Height raster map | 0.05 m × 0.05 m | 114,760 | 856,737 | 1.76 m | 13.4% |

| Resolution | Size (Pixels) | Red Pixels | Total Pixels | Proportion of Lodging Area | Relative Deviation 1 | SSIM 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RGB image | 7.2 mm GSD | 2942 × 1485 | 432,642 | 3,303,990 | 13.1% | 2.3% | 0.95 |

| Resolution | Size (Pixels) | Red Pixels | Total Pixels | Height Threshold | Proportion of Lodging Area | Relative Deviation 1 | SSIM 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Height raster map | 0.1 m × 0.1 m | 737 × 367 | 29,215 | 212,229 | 1.76 m | 13.8% | 5.3% | 0.95 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Yang, F.; Ji, L. UAV LiDAR-Based Automated Detection of Maize Lodging in Complex Agroecosystems. Drones 2025, 9, 876. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120876

Wang Y, Yang F, Ji L. UAV LiDAR-Based Automated Detection of Maize Lodging in Complex Agroecosystems. Drones. 2025; 9(12):876. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120876

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yajin, Fengbao Yang, and Linna Ji. 2025. "UAV LiDAR-Based Automated Detection of Maize Lodging in Complex Agroecosystems" Drones 9, no. 12: 876. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120876

APA StyleWang, Y., Yang, F., & Ji, L. (2025). UAV LiDAR-Based Automated Detection of Maize Lodging in Complex Agroecosystems. Drones, 9(12), 876. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120876