Highlights

What are the main findings?

- A dual-loop MPC architecture (outer-loop position MPC + inner-loop attitude MPC), weight-tuned via an Adaptive Niche Radius Genetic Algorithm (ANRGA), markedly improves tracking accuracy and stability for feeding UAVs under variable mass, inertia and wind—achieving max x-axis error of 0.018 m, typical axis errors ≤ 0.5 m with minimal overshoot, and ~58% faster response than a conventional single-loop MPC.

- Among six metaheuristics tested for MPC weight optimization, ANRGA delivers the best overall control performance—lowest average fitness and superior ISE/IAE/ITSE/ITAE—while maintaining rapid yet non-premature convergence, indicating it is the most effective optimizer for the dual-loop MPC in this application.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- The controller’s ability to sustain stable, repeatable, and high-precision tracking under complex feeding trajectories and gust disturbances indicates practical feasibility for real aquaculture operations (e.g., spiral paths and figure-eight maneuvers). This implies reduced overfeeding and missed feeding, improved feed utilization, and enhanced operational safety. The implication is corroborated by the consistency between simulated trajectories and attitude responses and is further supported by the two-loop stability analysis (small-gain condition under varying mass/inertia).

Abstract

Feeding unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) in aquaculture face critical challenges due to time-varying mass, strong coupling, and environmental disturbances, which hinder the effectiveness of conventional control strategies. This paper proposes a robust dual-loop model predictive control (MPC) framework optimized by an adaptive niche radius genetic algorithm (ANRGA). The outer loop employs MPC for position regulation using virtual acceleration inputs, while the inner loop applies MPC for attitude stabilization with dynamic inertia adaptation. To overcome the limitations of manual weight tuning, ANRGA adaptively optimizes the weighting factors, preventing premature convergence and improving global search capability. System stability is theoretically ensured through Lyapunov analysis and the small-gain theorem, even under variable-mass dynamics. MATLAB simulations under representative trajectories—including spiral, figure-eight, and feeding cruise paths—demonstrate that the proposed ANRGA-MPC-MPC achieves position errors below 0.5 m, enhances response speed by approximately 58% compared with conventional MPC, and outperforms benchmark controllers in terms of accuracy, robustness, and convergence. These results confirm the feasibility of the proposed method for precise and energy-efficient UAV feeding operations, providing a promising control strategy for intelligent aquaculture applications.

1. Introduction

Fisheries and aquaculture play a pivotal role in sustaining the world’s growing population. Over the past few decades, global aquaculture fish production has expanded rapidly, making a substantial contribution to the supply of fish for human consumption [1]. This contribution manifests in multiple dimensions, including poverty alleviation [2,3,4], job creation [5,6,7], economic growth, and the enhancement of income and nutritional security. Among the critical aspects of aquaculture, precise feed management stands at the forefront. Both underfeeding and overfeeding not only impair fish growth but also elevate production costs and exacerbate pollution within aquatic ecosystems [8]. Conventional aquaculture practices, being largely labor-intensive, are often inefficient, costly, and expose workers to considerable risks [9,10]. Consequently, the development of intelligent feeding systems is imperative to achieve uniform feed distribution, optimize nutrient utilization, and minimize water pollution during feeding operations. Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) technology has demonstrated considerable potential in meeting these technological requirements [11]. Thus, leveraging UAV-based solutions to achieve high-precision, energy-efficient, and intelligent feeding control emerges as a critical scientific and engineering challenge of contemporary aquaculture.

In recent years, UAV operational capabilities have advanced at an exponential rate, thereby empowering these platforms to accomplish multiple tasks in parallel [12]. Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS) have been widely deployed in marine scientific research, with de Lima et al. [13] providing a systematic account of their conservation-driven applications in oceanographic investigations. Agricultural UAVs, leveraging precision monitoring, crop protection, and automated seeding, have markedly enhanced operational efficiency in modern farming practices [14,15]. These systems are predominantly deployed at higher altitudes, exhibiting the capability for rapid dispersal of agricultural inputs. Nevertheless, the integration of UAV technology into aquaculture feeding practices remains in its infancy [16]. Feeding UAVs exhibit dynamic characteristics akin to agricultural UAVs, as both operate in low-altitude regimes near ground or water, where flight stability is susceptible to terrain irregularities, localized turbulence, battery decay, and variable payload mass [17]. Time-varying mass constitutes a fundamental parameter governing the flight dynamics of feeding UAVs [18]. Throughout feeding operations, the progressive reduction in mass necessitates adaptive control strategies to preserve flight stability; absent such mechanisms, unregulated mass depletion inevitably compromises operational efficiency. Consequently, the implementation of advanced attitude control architectures is indispensable for guaranteeing both stable flight and precise feed delivery.

A wide spectrum of quadrotor attitude control architectures has been explored, including Incremental Nonlinear Dynamic Inversion (INDI) [19], intelligent control schemes [20], and sliding-mode control [21]. Nonetheless, classical PID control remains the prevailing paradigm for small-scale UAVs in precision agriculture, particularly within the decentralized farming systems of southern China [22,23]. Kapnopoulos and Alexandridis [24] advanced a controller tuning framework grounded in Cooperative Particle Swarm Optimization (COOP-PSO), tailored for quadrotor trajectory-tracking missions employing an “outer-loop error-based MPC for position control” in conjunction with an “inner-loop PID for attitude stabilization”. While the dual-loop controller concept offers valuable inspiration, its direct applicability to the practical operational environment of aquaculture feeding remains limited. Ben Abdi et al. [25] introduced a hybrid P-PID controller, whose gain parameters were adaptively tuned through Ant Colony Optimization (ACO), thereby enhancing quadrotor robustness in the presence of external disturbances and dynamic uncertainties. Nonetheless, owing to the use of a sole proportional regulator in the altitude loop, this design is prone to pronounced tracking errors under variable-mass conditions. Wu et al. [26] developed a Distributed Model Predictive Control (DMPC) scheme, wherein the Adaptive Grasshopper Optimization Algorithm (AGOA) served as the underlying solver for trajectory optimization of multiple Solar UAVs engaged in cooperative target-tracking missions in urban environments. Moreover, there are deep reinforcement learning methods based on the Simulated Annealing—Twin Delayed Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (SA-TD3) framework for quadrotor attitude stabilization and position tracking [27]; a performance comparison of 8 model-free reinforcement learning algorithms in quadrotor attitude control and trajectory tracking, along with a benchmark recommendation for the TD3 algorithm [28]; the Differential Evolution (DE) algorithm to optimize PID parameters for improving quadrotor energy efficiency [29]; the TD3-TPR method combined with Tangential Path Reward (TPR) that considers attitude dynamics to optimize quadrotor autonomous navigation [30]; and the optimization of Model Predictive Control (MPC) parameters based on the Improved Black-Wing Kite Algorithm (IBKA) to enhance the heading control and depth tracking accuracy of Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs) [31]. Although this framework cannot be seamlessly adapted to the aquaculture-feeding scenario under investigation, its optimization methodology provides valuable conceptual guidance.

Driven by the rapid advancement of the semiconductor industry, embedded platforms have witnessed remarkable growth in computational capacity, thereby markedly enhancing their efficiency in solving Quadratic Programming (QP) problems. Consequently, Model Predictive Control (MPC) schemes are now more amenable to deployment in nonlinear, strongly coupled UAV systems, enabling enhanced control performance in such complex dynamics.

Model Predictive Control (MPC) constitutes a control paradigm that leverages predictive models of system dynamics. By employing a Rolling Horizon Optimization (RHO) strategy, MPC anticipates the influence of control inputs on the system’s future trajectories [32,33]. By means of optimization, MPC simultaneously addresses the demands of position and attitude regulation, thereby yielding optimal thrust–acceleration and angular-velocity commands. The efficacy of MPC is strongly contingent upon the accuracy of the underlying model. In practice, however, precise mathematical modeling of quadrotor UAVs proves challenging—especially in time-varying configurations characterized by heavy payloads and pronounced load fluctuations. Consequently, deviations between MPC-predicted trajectories and the UAV’s actual states may emerge, ultimately degrading attitude-control accuracy. To mitigate this issue, a dual-loop MPC framework is proposed herein, wherein the outer loop governs position regulation while the inner loop is dedicated to attitude stabilization. The synergistic interplay of the two loops enables the feeding UAV under investigation to attain superior control performance. Simulation results corroborate that the proposed controller effectively mitigates disturbances arising from modeling inaccuracies.

Nevertheless, MPC-MPC frameworks exhibit a pronounced dependence on control parameters, where empirical tuning typically entails laborious trial-and-error procedures, thereby rendering the experimental process both time-intensive and inefficient. Accordingly, metaheuristic optimization offers a viable pathway for selecting optimal gains in attitude control. Classical approaches—such as Genetic Algorithms (GA) [34], Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [35], and Simulated Annealing (SA)—are prone to premature convergence, often stagnating in local optima [36,37]. To overcome this limitation, this study refines the conventional Genetic Algorithm and integrates it within the MPC-MPC framework, culminating in an Adaptive Niche Radius Genetic Algorithm-based MPC-MPC (ANRGA-MPC-MPC). The proposed controller was validated through MATLAB 2023b-based simulations of quadrotor UAVs across three distinct motion scenarios.

2. Dynamic Modeling and Dual-Loop MPC Design

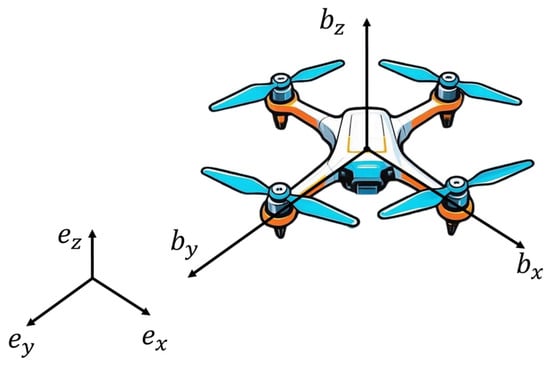

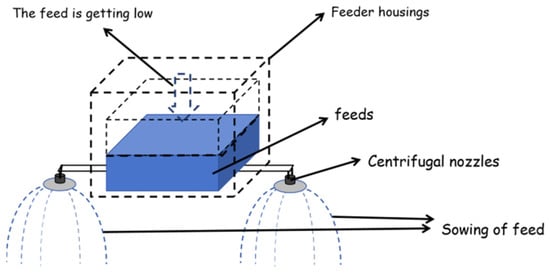

Quadrotor UAVs represent a prototypical class of underactuated, time-varying systems characterized by multivariable nonlinearities and strong coupling effects [38], as illustrated in Figure 1. As depicted in Figure 2, the feed container affixed beneath the quadrotor may be reasonably approximated as a time-varying lumped mass, subject to an admissible error tolerance.

Figure 1.

Configuration of the quadrotor in the right-handed body-fixed frame. forward, right, down. Attitude follows the convention. Positions are defined in the inertial frame used in the model and in the wind-disturbance description.

Figure 2.

Operational illustration of the feed container.

The modeling and control design adopt right-handed coordinate frames. The inertial frame () is used for positions () and for the wind-disturbance description. The inertial vertical is aligned with ; gravity acts along the negative inertial vertical. The body-fixed frame () is right-handed with pointing forward, pointing to the right, and pointing downward along the thrust axis. Attitude is parameterized by Euler angles following the sequence with right-hand positive rotations. The rotation from body to inertial is defined by this sequence, and the Newton–Euler equations and their small-angle linearization are interpreted under these conventions. This choice is consistent with the use of an inertial reference frame in the dynamic model and with the wind-field variables, which are specified in the inertial frame in the disturbance model.

As mass depletion progresses and the moments of inertia evolve, the UAV’s dynamic parameters undergo continuous variation within the governing dynamic model. Accordingly, the time-varying mass is formally defined as:

In this context, denotes the UAV’s full-load mass, specifies the feed-release rate per unit time (kg/s), and corresponds to the elapsed flight duration. Accordingly, the variation rate of the moment of inertia is expressed as:

In this formulation, represents the container’s moment of inertia about its intrinsic center of mass, while denotes the offset distance between the container’s center of mass and the UAV’s overall centroid. The aforementioned notation is applied consistently throughout the manuscript and will not be reiterated henceforth.

The mathematical formulation of the UAV is derived from the Newton–Euler equations, yielding the following dynamic model [39]:

Here, and represent the translational coordinates of the UAV’s center of mass with respect to the inertial reference frame; and correspond to the roll, pitch, and yaw angles, respectively; , and u4 denote the control input signals; denotes the gravitational acceleration, specified as 9.81 m/s2; , , and designate the external disturbances imposed on the translational dynamics of the UAV’s center of mass; , , and correspond to the external disturbances exerted on the rotational dynamics about the UAV’s center of mass.

As previously noted, the intrinsic nonlinearities, strong couplings, and underactuated characteristics of quadrotors necessitate linearization of their governing dynamic equations. In low-speed, constant-altitude operations above aquaculture ponds, the condition is satisfied, whereby small-angle linearization markedly alleviates computational complexity while preserving the real-time feasibility of rolling-horizon optimization. For moderate attitude deviations () induced by maneuvers, gust perturbations, or rapid trajectory transitions, Section 2.1 elaborates on nonlinear extensions together with Reference Governor (RG)-based constraint handling, thereby extending the controllable envelope.

2.1. Controller Design

All matrices and variables in this section follow the coordinate frames and conventions stated in Section 2, which ensures consistent interpretation of and the linearization near hover. Under the small-angle assumption (), with yaw angle ψ approximated as a constant (), and linearization performed about the near-hover equilibrium (), the following linearized model is obtained:

To enable the outer loop to exert direct regulation over the “acceleration target”, the virtual control input is defined as:

Here, represents the desired acceleration vector of the UAV’s center of mass. By operating directly within the acceleration domain, the outer loop employs a double-integrator approximation to map acceleration references into position trajectories, thereby mitigating the intermediate nonlinear coupling between “position” and “attitude” while enhancing the interpretability of the outer-loop predictions.

Approximated through an ideal double-integrator representation:

Consequently, the states and inputs of the outer loop can be expressed as:

The resulting continuous-time model can thus be formulated as:

The system is discretized via a Zero-Order Hold (ZOH) scheme:

Zero-Order Hold (ZOH) discretization is adopted since both the onboard flight controller and the supervisory computer operate under a fixed sampling period . The ZOH scheme effectively approximates the actuator behavior of maintaining constant input between sampling instants, while ensuring consistency with the discrete prediction inherent to rolling-horizon optimization.

In the above equations,

Let denote the prediction horizon and the control horizon, subject to the constraint . They are defined as follows:

It follows that:

where

Likewise, linearization about the small-angle equilibrium point , with quadratic coupling terms , , and neglected, yields:

Accordingly, the states and inputs of the inner loop are defined as:

where

Upon discretization, the system can be expressed as:

where

By analogy, one obtains:

where

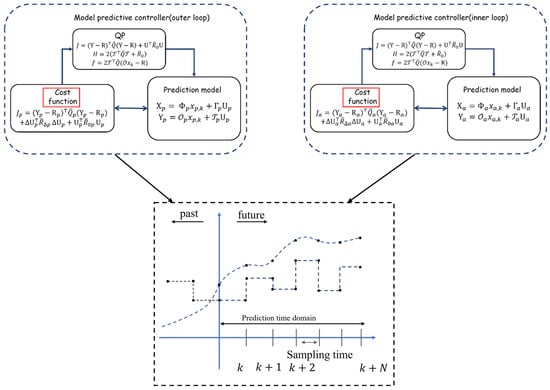

Building upon the aforementioned linearized discrete model, the cost functions for both the outer- and inner-loop controllers can be formulated, with the outer loop defined as:

In this context, , and denote the state-weighting matrix and the control-weighting matrix, respectively.

Formulated as a Quadratic Programming (QP) problem:

The inner loop is formulated as:

Formulated as a Quadratic Programming (QP) problem:

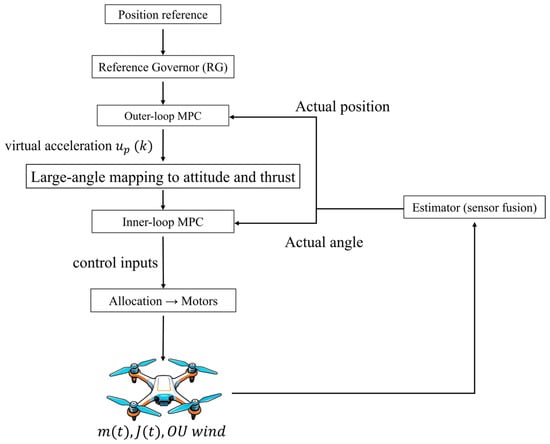

At this stage, the mathematical models of both the outer- and inner-loop controllers have been established, and the corresponding dual-loop MPC architecture is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Schematic of the dual-loop MPC architecture.

In Figure 3, the outer loop receives as its input and generates , which incorporates the gravity-compensation component; the inner loop maps to the desired attitude (corresponding total thrust), subsequently allocated to the four rotors via thrust–torque distribution. Bandwidth separation ensures the “slower outer loop and faster inner loop” characteristic, with a typical bandwidth ratio of no less than 5.

2.2. Extension to Large-Angle Operating Conditions

In the preceding section, the controller was designed under the small-angle and near-hover assumptions, enabling effective regulation during routine constant-altitude aquaculture operations. In practical scenarios, however, UAVs are frequently required to undertake maneuvers such as turning, gust alleviation, and rapid path transitions, wherein roll and pitch angles may rise to . Retaining the small-angle approximation under such conditions leads to pronounced errors in gravity decomposition and coupling dynamics, thereby degrading control accuracy and compromising system stability. Accordingly, this section extends both the inner- and outer-loop controllers to accommodate large-angle operating conditions, while preserving the dual-loop MPC framework.

Taking into account the time-varying mass and inertia , the translational and rotational dynamics of the UAV can be expressed as:

Here, denotes the attitude rotation matrix, represents the body angular velocity, corresponds to the total thrust, and designates the control torque vector.

As defined earlier, the outer-loop virtual input is given by which, under large-angle operating conditions, must be mapped into the corresponding desired attitude and thrust. is defined as:

Here, represents the desired orientation of the body-fixed axis. Together with the desired yaw angle , it follows that:

The desired thrust magnitude can be expressed as:

Considering the inner-loop state and the control input . Equation (27) can be discretized into the following form:

Here, is computed via numerical integration. The inner-loop NMPC cost function is formulated as:

The constraints are formulated as:

Owing to the constrained computational resources of the UAV’s onboard processor, a Linear Parameter-Varying (LPV) approximation is employed. Let the scheduling parameters be defined as:

The matrices are precomputed at offline grid points, and the online barycentric interpolation produces:

Accordingly, the incremental linear MPC is formulated as:

The optimization objective is formulated as:

Subject to constraints on attitude angles, angular velocities, and thrust.

To guarantee the attainability of the outer-loop reference, the virtual input is governed accordingly.

Constraint on lateral acceleration:

where .

Constraint on trajectory curvature:

Here, denotes the trajectory curvature, while represents the horizontal velocity.

If these bounds are exceeded, the Reference Governor (RG) smooths the trajectory or scales the reference acceleration, thereby guaranteeing the feasibility of the inner-loop attitude dynamics. The RG is incorporated to guarantee the geometric attainability of the outer-loop reference trajectory, ensuring that the virtual input produced by the outer loop remains within the physical limits of the inner-loop attitude dynamics.

In MATLAB simulations, the average computational time for a single-step optimization was 0.02 s (Intel i5 CPU, sampling interval of 10 ms), demonstrating that the proposed controller exhibits real-time implementability on existing embedded platforms.

This chapter addressed the time-varying dynamics of the feeding UAV by developing a linearized dual-loop MPC model under small-angle assumptions, wherein state and control weighting terms were incorporated into the cost function to balance tracking accuracy against energy consumption. Building upon this, an extension to large-angle operating conditions was proposed, incorporating nonlinear modeling, an LPV approximation, and a reference governor, thereby ensuring the feasibility and stability of the controller under complex maneuvering scenarios. The foregoing design establishes a unified control framework that facilitates the incorporation of optimization algorithms in the subsequent chapter.

3. Adaptive Niche Radius Genetic Algorithm for MPC Optimization

This study targets a safety-critical dual-loop MPC for aquaculture feeding UAVs that face variable mass and near-surface wind. We optimize (Q,R) offline so that the deployed controller remains a standard constraint-aware MPC with the stability guarantees derived in this paper, and a predictable onboard cost given by a QP per control step. The genetic algorithm is used only before flight and does not introduce additional real time burden. The weight search problem is multimodal because of outer and inner loop coupling and time-varying inertia. To reduce the risk of premature convergence we adopt an Adaptive Niche Radius Genetic Algorithm. Fitness sharing maintains population diversity in early generations, and a scheduled niche radius gradually strengthens exploitation in later generations. The observed convergence profiles and the time domain indices reported in the Results section are consistent with this behavior.

Reinforcement learning is a promising direction. However, reaching the same level of explicit constraint handling, certifiable stability, and transparent deployment would require large amounts of interaction data, explicit safety filters, and additional compute and memory for policy inference and verification. Given the current deployment priorities, namely stability certificates, interpretability, and maintainability, an offline tuned MPC with ANRGA is the most suitable choice.

3.1. Adaptive Adjustment of Weight Factors via Genetic Algorithms

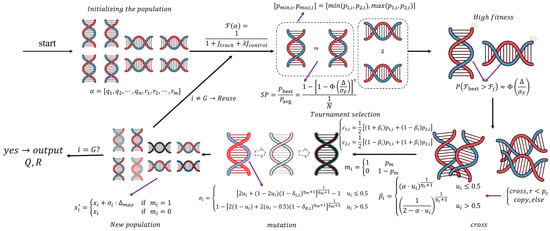

As previously discussed, the practical unavailability of an exact quadrotor UAV model often results in fluctuations in control accuracy. Consequently, adaptive adjustment of the weighting factors in the Model Predictive Controller (MPC) is required to mitigate this limitation. The Genetic Algorithm (GA) is a biologically inspired evolutionary optimization technique, rooted in the principles of genetic inheritance. By employing genetic operators—namely, selection, crossover, and mutation—it explores complex search spaces to efficiently identify near-optimal solutions. Leveraging this capability, the GA can be integrated with the MPC framework (Figure 4) to supplant manual tuning of weighting factors, thereby enabling the rapid acquisition and construction of high-performance weighting matrices.

Figure 4.

MPC framework integrated with the Genetic Algorithm (GA).

First, an initial population consisting of combinations of weighting factors is generated, where chromosomes are encoded in real numbers to represent the diagonal entries of the weighting matrix (with the outer loop taken as an illustrative example):

Here, , with the logarithmic scaling adopted to guarantee positive definiteness; , employed to mitigate numerical overflow.

Following the generation of the initial population, a fitness evaluation is performed, with the corresponding evaluation function defined as:

where

denotes the tracking-error component, defined as:

denotes the control-energy consumption component, defined as:

denotes the trade-off coefficient that balances the penalty weights assigned to control-energy consumption and tracking-error performance. A larger value of biases the system toward minimizing energy expenditure at the expense of tracking accuracy, whereas a smaller enhances tracking precision but incurs higher energy consumption. In practical flight scenarios, further improves the system’s capability to attenuate instantaneous disturbances. Within the iterative process of the Genetic Algorithm (GA), is dynamically adapted along the Pareto front:

Here, denotes the incremental change in the tracking-error component; denotes the incremental change in the control-energy component.

To eliminate dimensional inconsistencies that may bias the weighting, the error term is normalized with respect to its maximum value, while the energy-consumption term is normalized against the full-load power reference, with both scaled into the [0, 1] range. The learning rate is chosen to ensure smooth convergence while mitigating excessive parameter oscillations induced by the rapid mass depletion during feeding, thereby achieving a trade-off between flight stability and energy efficiency. This choice is supported by extensive sensitivity analyses, which indicate that within the range [0.05, 0.2], the algorithm exhibits negligible variation in convergence performance.

In the above formulation, denotes the tracking error at time step , while designates the weighting factor associated with the tracking error at that instant.

Following evaluation by Equation (41), the initial population proceeds to the genetic iterations, beginning with population selection, where a tournament-based selection strategy is employed. The best individual attains a winning probability of unity in a single tournament, provided it appears within the selected candidates. The probability of exclusion is given by ; thus:

In practical tournament selection, the selection probability of the best individual varies as a function of the fitness distribution. Let denote the probability that the best individual prevails in a random comparison:

For any two individuals and , the probability that iii outperforms is given by:

Here, denotes the standard deviation of the population fitness distribution; denotes the average fitness of the population; denotes the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the standard normal distribution. For the best individual, is given as:

It follows that:

Furthermore, the selection pressure is given by:

In UAV attitude-control optimization, a moderate increase in selection pressure expedites the identification of stable parameter configurations, whereas excessive pressure may drive the solutions to collapse into a local region, thereby undermining robustness. Accordingly, this work employs fitness-variance-based dynamic adjustment of the selection pressure, thereby striking a balance between rapid convergence and robustness in controller optimization. The fitness-variance coefficient is defined as .

After selection yields the fittest individuals, they proceed to chromosome crossover and mutation operations, producing offspring with enhanced fitness. Given that the weighting factors are continuous-valued, crossover is performed using the Simulated Binary Crossover (SBX) method, while mutation is implemented via polynomial mutation. The adoption of SBX and polynomial mutation stems from the fact that MPC weighting parameters are continuous real-valued variables. This approach preserves the feasibility of the generated parameters within the physical bounds and mitigates the emergence of unstable extreme control gains—an aspect especially crucial for the strongly coupled outer and inner loops of the dual-loop MPC framework.

Let the two parent chromosomes be denoted as:

Here, denotes the dimensionality of the chromosome.

Compute the gene difference between the parent chromosomes:

The crossover probability is defined to determine whether a pair of parent chromosomes undergoes crossover. For each pair of parent chromosomes, generate a random number :

When crossover is performed, the expansion factor is first generated:

Here, ; while denotes the distribution index of the crossover operator.

The offspring chromosomes can be modeled by employing the expansion factor as:

Upon expansion, it follows that:

Furthermore, boundary conditions must be specified.

The parent interval is defined as:

The effective interval of the offspring is defined as:

Finally, it must be constrained within the search space :

By deriving the probability density function (PDF) of , the effect of the crossover distribution index in Equation (52) on parent crossover can be characterized, with the PDF defined as:

As , , yielding an approximately uniform distribution and placing the algorithm in a highly exploratory regime; As , , causing the offspring to converge toward the mean of the parents.

In contrast to crossover, the mutation operator acts exclusively on a single parent chromosome. Offspring are generated by independently perturbing each gene locus of the chromosome. Polynomial mutation is adopted herein, with the parent chromosome represented as , constrained within the search space . The normalized distance from the search-space boundaries is defined as:

Here, denotes the relative distance to the left boundary, whereas denotes the relative distance to the right boundary.

For each gene position , a mutation is applied with probability , and the mutation indicator is defined as:

Here, denotes a Bernoulli random variable.

If a gene position is selected for mutation, the perturbation magnitude is determined by a random number drawn from the parent, thereby enabling mutations of varying intensities. Let the perturbation magnitude be defined as ; thus:

Here, denotes the mutation distribution index, which governs the overall intensity of the mutation operator. This characteristic is captured by the probability density function (PDF) of , defined as:

As :

It degenerates toward a uniform distribution, resulting in relatively large mutation amplitudes.

As :

It converges toward the Dirac delta function, with mutation amplitudes diminishing to zero. The function is defined as:

Based on the perturbation magnitude derived from Equation (64), the offspring generated under the mutation operator are computed as:

Here, denotes the search-space span. The probability density function (PDF) of the offspring gene value is defined as:

Here, denotes the exploitation component within the mutation process; constitutes the exploration component. The expected value of the offspring is analyzed as:

It can thus be demonstrated that the mutation operator introduces no systematic bias, thereby preserving solution quality. This property is particularly critical for the MPC-based UAV attitude controller, as it prevents the generation of infeasible weighting factors. Upon completion of selection, crossover, and mutation, the Genetic Algorithm (GA) produces a new population. The process iterates until the prescribed maximum number of generations is reached, at which stage the optimal weighting factors are obtained. The overall procedure is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Flowchart of the Genetic Algorithm (GA).

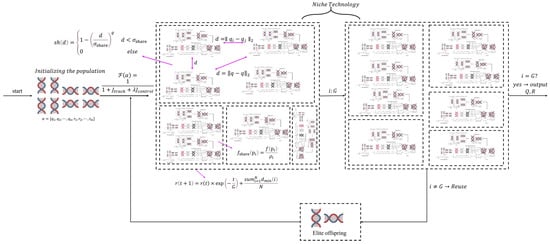

3.2. Incorporation of Niching Technique

By employing the aforementioned genetic algorithm, adaptive adjustment of the weighting factors in the Model Predictive Controller (MPC) can be realized. Nevertheless, conventional genetic algorithms (GAs) remain prone to premature convergence into local optima. During the later stages of evolution, the population frequently undergoes premature convergence, resulting in the loss of diversity—for instance, individuals tend to cluster around local optima without the ability to escape, thereby precluding the attainment of the global optimum. Even with exploration ability regulated via and , the improvement remains marginal.

Accordingly, to preserve population diversity, this work incorporates the niching technique (Figure 6). The notion of niching stems from the ecological concept of a “niche”, denoting the survival space of species within a given environment. Conventional genetic algorithms (GAs) face pronounced limitations when tackling multimodal optimization problems, often leading to premature convergence or the erosion of diversity. Drawing inspiration from the coexistence and coevolution of species in nature by occupying distinct niches, researchers have developed a suite of niching methods designed to sustain population diversity, avert the monopolization by a single optimum, and concurrently identify and maintain multiple optima. Its central principle lies in simulating niche partitioning, resource sharing, and competitive interactions within the algorithmic population, while leveraging mechanisms such as fitness-sharing penalties to steer the population toward the formation and maintenance of multiple stable subpopulations (niches), thereby remedying the fundamental deficiencies of conventional genetic algorithms.

Figure 6.

Schematic structure of the Niching Genetic Algorithm (NGA).

First, the population is partitioned into several independent niches (subpopulations). Shared fitness is then derived by computing the Euclidean distance between individuals together with the niche density, thereby enabling clustering. The Euclidean distance between two individuals is defined as:

The niche radius is accordingly defined as:

Accordingly, the sharing function is derived as:

Here, denotes the shape parameter. Individuals separated by less than are grouped into a single niche.

The niche density of individual is determined using the sharing function and the niche radius:

The shared fitness is defined in terms of :

Within the solution space, if left unconstrained, densely populated groups tend to dominate, causing the algorithm to converge prematurely into local optima, thereby neglecting potentially superior individuals and diminishing population diversity. By executing shared-fitness operations independently within each niche, densely clustered individuals are penalized, while sparsely distributed ones gain competitive advantage, thus preserving population diversity and mitigating premature convergence to local optima.

To strike a balance between algorithmic convergence speed and population diversity, this study adopts an adaptive niche radius. During the early stages of evolution, a relatively large niche radius is employed to enhance global exploration and preserve diversity; As evolution advances, the niche radius is progressively reduced, facilitating deep exploitation within regions populated by optimal individuals and thereby expediting convergence.

The adaptive radius is formulated as:

Here, denotes the maximum number of iterations, while denotes the minimum distance from individual iii to all other individuals (excluding itself). In the context of UAV attitude control, if the search converges prematurely to a local region, the weighting parameters may be unable to adapt to dynamic characteristics such as rapid mass depletion. The adaptive niche radius preserves a broad search range during the early stages to prevent entrapment in local optima, and progressively contracts in later stages to accelerate convergence toward the global optimum. It is worth emphasizing that the Genetic Algorithm (GA) employed herein is solely utilized for offline weight optimization prior to flight missions. During real flight operations, the controller merely employs the pre-optimized weighting parameters for receding-horizon prediction and control, thereby incurring no additional burden on the real-time capabilities of the embedded hardware.

3.3. Stability Analysis of the System

Following the design of the dual-loop MPC controller, it is essential to conduct a theoretical analysis of system stability. As the system is discretized into a linear model around the small-angle hovering point and the cost function is quadratic, the Lyapunov method together with the feasibility principle of receding-horizon optimization can be invoked within the predictive control framework to establish asymptotic stability of the closed-loop system. First, the stability of a single loop is examined. For the outer-loop discrete model, it follows that:

The predictive cost function is formulated as:

where . Let the optimal receding-horizon cost be denoted as:

According to the construction method of the “shifted feasible sequence”, it can be demonstrated that:

Therefore, serves as the Lyapunov function of the closed-loop system, indicating that the outer loop is asymptotically stable. Similarly, for the inner loop:

By incorporating its quadratic cost function, a similar conclusion can be drawn.

In the dual-loop architecture, the attitude reference generated by the outer loop serves as the input to the inner loop. If the inner loop is designed with a sampling frequency at least 3–5 times faster than that of the outer loop, and its tracking error exhibits input-to-state stability (ISS) with respect to reference variations, then from the outer loop’s perspective, the system can be regarded as an MPC framework subject to small disturbances.

According to the small-gain theorem, the following conditions must be satisfied:

Then the overall dual-loop system remains asymptotically stable.

During the feeding process, the system mass and moment of inertia gradually decrease over time, rendering the system matrices slowly time-varying. If the parameter variation rate is sufficiently small such that:

Then, as long as , the system still preserves its stability.

In this study, the solution space of the GA is defined as the set of weighting factors subject to the following hard constraints:

- (1)

- ;

- (2)

- The terminal control gain is computed from , and the terminal weight is defined as the solution to the discrete algebraic Riccati equation (DARE):

- (3)

- The terminal invariant set is positively invariant under the closed-loop dynamics and satisfies the imposed constraints;

- (4)

- The small-gain or bandwidth separation condition of the dual-loop system holds.

Let . From the DARE, it follows that:

Summing up yields:

If we denote , then it follows that:

That is, the larger and the smaller , the faster the system converges with reduced overshoot. Within , ANRGA explores different combinations of and . By leveraging multimodal search to avoid entrapment in local optima, it is more likely to identify weight combinations yielding larger and smaller thereby enhancing the Lyapunov decay rate.

In summary, Section 3 presents an Adaptive Niche Radius Genetic Algorithm (ANRGA) that achieves efficient optimization of MPC weighting parameters and demonstrates, through stability analysis, the asymptotic stability of the closed-loop system. The subsequent chapter will further validate the effectiveness of the proposed method through comparative simulations involving different controllers and optimization algorithms.

4. Simulation Results and Analysis

4.1. Comparative Study with Different Controllers

After establishing the mathematical model of the controller, simulation experiments for different controllers are conducted in MATLAB (Intel i5 CPU, 16 GB RAM). All four controllers are tuned empirically. To ensure fairness, their parameters are adjusted under identical trajectories and wind disturbance conditions through repeated simulations until the respective error and energy-consumption indices stabilize within acceptable bounds. The results are summarized in Table 1. The simulation trajectory is defined such that the UAV ascends vertically to 4 m, hovers, and subsequently simulates the actual feeding scenario. Under full load, feeding begins once the UAV reaches 4 m, during which the mass and moments of inertia gradually vary.

Table 1.

Parameters for Simulating Wind Disturbance.

To better approximate the aerodynamic disturbances encountered in real flight environments, this study incorporates a nonlinear Ornstein–Uhlenbeck (OU) wind disturbance model into the UAV dynamic simulations. This model captures both the temporal correlation of the wind field and the characteristics of small-scale turbulence, while preventing numerical degeneration. Its continuous-time representation can be expressed as:

Here, denotes the wind velocity vector in the inertial frame; is the time constant of the OU process; represents the intensity of large-scale stochastic disturbances; characterizes the turbulence intensity; and and are independent standard Wiener processes. Unlike the conventional OU process that employs a fixed mean, the present study adopts a dynamic mean aligned with the current wind direction:

To prevent aerodynamic drag from vanishing as the wind speed decays toward zero, a small random perturbation is introduced whenever , thereby ensuring it remains within a physically reasonable range.

In the aerodynamic modeling, the relative airflow velocity is defined as:

The aerodynamic drag acting on the UAV is modeled using an axis-wise quadratic formulation:

Here, the air density is ; the equivalent frontal area in the lateral directions is ; and in the vertical direction is . Ultimately, together with thrust and gravity, is applied to the translational dynamics for numerical integration.

Balancing simulation accuracy and computational efficiency, the parameters listed in Table 1 are adopted in this study. This wind disturbance model preserves the slow drift characteristics of large-scale wind fields while capturing the high-frequency fluctuations of small-scale turbulence, thereby providing a realistic representation of UAV flight disturbances in a wind environment.

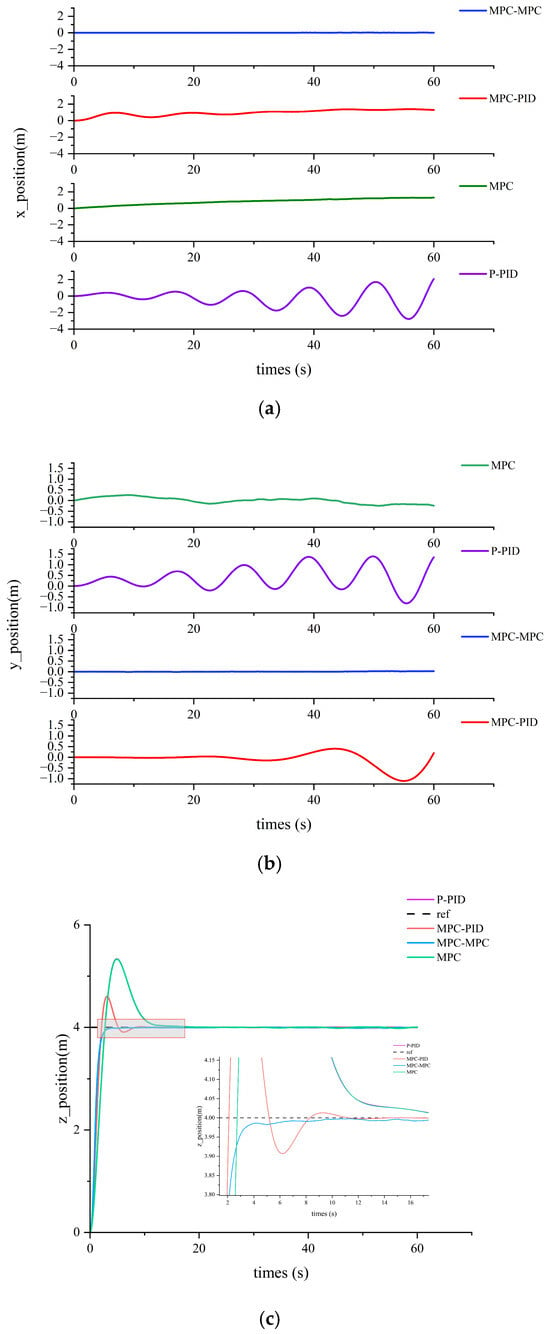

To avoid randomness in the experimental results, each set of experiments is independently executed at least 30 times and simulated on three different computers to validate the performance of the controllers. In aquaculture feeding, the UAV’s three position indices directly determine the feeding accuracy. Excessive position deviation results in uneven feed distribution. Therefore, the simulations focus primarily on the UAV’s positional accuracy along all three axes.

As illustrated in Figure 7, in Figure 7a, the dual-loop MPC exhibits the best performance in x-axis position control, with a maximum deviation of only 0.018 m. The MPC-PID controller ranks second, with a maximum deviation of 1.139 m, whereas the traditional MPC and P-PID controllers show maximum deviations of 1.278 m and over 3 m, respectively. Notably, the P-PID controller exhibits pronounced oscillations in the x-axis position. As shown in Figure 7b, the performance of each controller varies across different positional axes. Nonetheless, the dual-loop MPC consistently achieves the highest accuracy, with maximum errors not exceeding 0.5 m. The MPC-PID controller performs worse on the y-axis compared to the x-axis, maintaining errors around 1 m. The traditional MPC maintains stable control within 0.5 m along the y-axis, while the P-PID controller continues to exhibit significant oscillations. In terms of ascent performance (see Figure 7c), the P-PID controller exhibits the largest overshoot, with a maximum error approaching 1.5 m. The dual-loop MPC achieves rapid ascent with virtually no overshoot, whereas the other two controllers ascend quickly but with pronounced overshoot.

Figure 7.

Position tracking under the different controllers; (a) describes the positions of different controllers along the x-axis; (b) describes the positions of different controllers along the y-axis; (c) describes the height control performance of different controllers.

A comparison of the manually tuned controllers clearly shows that the dual-loop MPC achieves near-ideal control accuracy. However, as illustrated in Figure 8, although the dual-loop MPC exhibits high accuracy, its control speed remains somewhat limited. Nevertheless, the response speed of the dual-loop MPC is still at least 58% faster than that of the traditional MPC. Among the four controllers, the P-PID responds the fastest, followed by MPC-PID; the dual-loop MPC ranks third, while the single MPC exhibits the slowest response.

Figure 8.

Comparison of response times among the four controllers.

4.2. Control Performance of the Dual-Loop MPC Under Different Optimization Algorithms

The preceding section compared four different controllers; however, during the simulations, their parameters were manually tuned based on empirical methods, with each controller requiring an average of approximately 3.3 h. Parameter tuning is particularly more complex for cascaded controllers. It was observed during tuning that even slight adjustments to the inner-loop attitude parameters can exert unpredictable effects on the outer loop, while minor modifications in the outer-loop parameters may lead to significant deviations in the inner loop. This, in turn, may cause overcompensation in the inner loop, severe position-control offsets, and ultimately a vicious cycle during flight. Given the strong coupling inherent in cascaded controllers, their performance is highly dependent on control parameters. Consequently, the parameter-tuning process in this study is regarded as a multimodal optimization problem. In multimodal optimization problems, metaheuristic algorithms play a pivotal role. However, as discussed earlier, the performance differences among optimization algorithms are substantial. Therefore, selecting an appropriate optimization algorithm is particularly critical for the feeding-type quadrotor UAV investigated in this work.

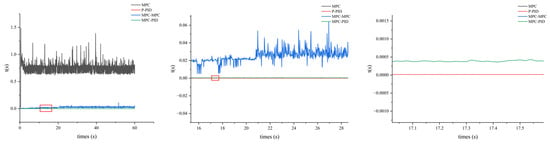

By simulating six different optimization algorithms and recording the data, the trajectory is again defined as ascent and hover at 4 m under wind disturbance conditions. The integral of squared error (ISE), integral of absolute error (IAE), integral of time-weighted squared error (ITSE), and integral of time-weighted absolute error (ITAE) are adopted as performance indices for evaluating the optimization algorithms. The positional data along x, y, and z are recorded, and the corresponding metrics are computed, with the results summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of Various Errors in Different Optimization Algorithms.

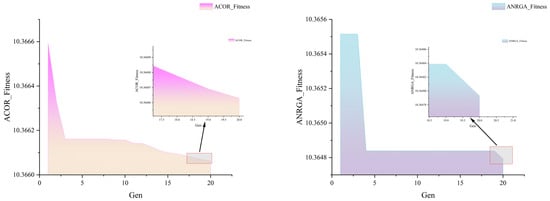

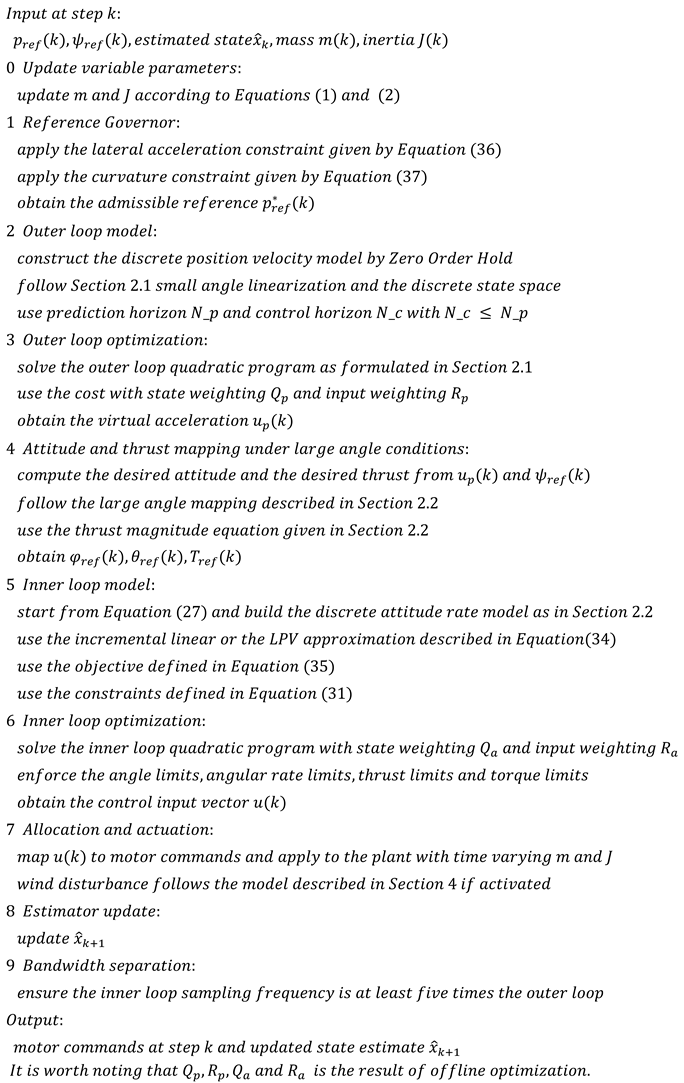

From the above data, it can be observed that the dual-loop MPC controller optimized with the adaptive niche radius exhibits the lowest average fitness and demonstrates superior control performance across all error-based performance indices. In terms of convergence (see Figure 9), the fitness descent processes of different algorithms are compared.

Figure 9.

Fitness values corresponding to different algorithms. The maintained descent in later generations with preserved spread reflects the use of shared fitness and an adaptive niche radius that first favors exploration and then focuses exploitation, consistent with the mechanism described in Section 4.2.

Comparative results indicate that the Genetic Algorithm, the Pelican Algorithm, and the Adaptive Niche Radius Genetic Algorithm converge the fastest; the Grasshopper Algorithm begins converging only after the 16th generation; the Ant Colony Algorithm experiences a sharp drop at the 3rd generation but then enters slow convergence after the 10th generation; and the Particle Swarm Optimization remains in slow convergence throughout the first 17 generations. Compared with the Ant Colony Algorithm, the proposed method achieves a similar convergence rate but yields lower fitness values and continues to exhibit a significant downward trend in the later stages. For UAV control systems, even for heavily loaded and less maneuverable feeding-type UAVs, rapid convergence of the optimization algorithm remains one of the key performance indicators. However, it must be noted that rapid convergence should not come at the expense of diversity; otherwise, premature convergence may trap the algorithm in local optima. On this basis, the proposed Adaptive Niche Radius Genetic Algorithm effectively balances the requirement for rapid convergence with the necessity of avoiding premature convergence.

This study employs a dual-loop MPC in which the outer loop regulates position or velocity and the inner loop stabilizes attitude and rate under variable mass and low-altitude wind. The weighting design of Q and R forms a multimodal landscape due to the coupling between the two loops and the slow time variation in the inertial parameters during feeding. The offline ANRGA MPC approach is aligned with this setting because the genetic search is executed before flight and the flight controller remains a standard constrained dual-loop MPC that solves a deterministic QP each step. The manuscript specifies that the GA is used only for offline weight optimization and therefore imposes no additional run time burden, while the online computation is limited to the receding horizon QP. Stability is analyzed for the outer and inner loops and for their interaction, using Lyapunov arguments and a small-gain condition together with terminal constraints and a DARE-based terminal weight, which provides an analytical basis for closed-loop asymptotic stability in the dual-loop architecture. Within this admissible set the ANRGA maintains population diversity by niching and then schedules the niche radius to accelerate convergence, which addresses premature convergence in the multimodal search and is the specific mechanism adopted in the manuscript. The results already reported show that the ANRGA tuned dual-loop MPC achieves the lowest average fitness and consistently improved error based indices over alternative metaheuristics under the same budget, and the convergence profiles exhibit a faster descent without loss of diversity, which supports the final design choice for initial deployment. In contrast, a reinforcement learning workflow would require a separate training process with interaction data or explicit domain randomization and additional mechanisms for constraint enforcement and policy validation, and the manuscript does not implement such a framework. Given the present deployment objective that favors analytical stability, explicit constraints, and predictable timing on embedded avionics, the offline ANRGA MPC configuration matches the requirements established earlier in the paper.

The fitness aggregates normalized tracking error and control effort over the prediction horizon. Candidate weights must satisfy the stability-admissible conditions defined by the terminal controller, the DARE-based terminal weight, the terminal invariant set, and the small-gain requirement. Infeasible candidates are rejected or penalized. The population is initialized within physically meaningful bounds and may include seeded individuals from prior tuning. Selection, crossover, and mutation follow standard operators under a fixed generation budget. Diversity is maintained through fitness sharing. The niche radius is scheduled as a monotone function of the generation index so that exploration is emphasized in early generations and gradually concentrated later. Only the deterministic quadratic program of the dual-loop MPC runs in flight.

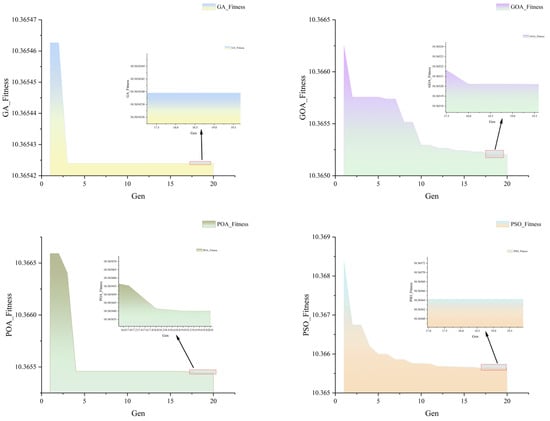

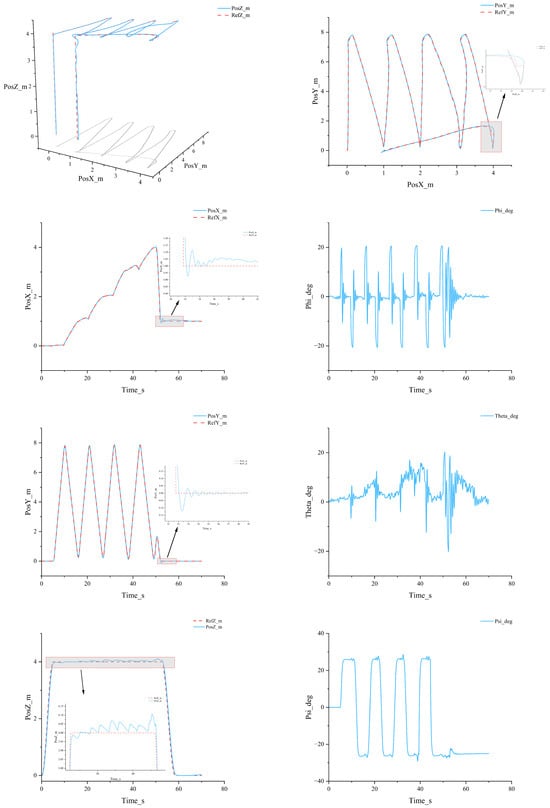

To further validate the superior performance of the proposed algorithm, the UAV is simulated to follow different trajectories. Figure 10 illustrates that the trajectory generated by Algorithm A1 is a helical trajectory. This trajectory involves both altitude variations and horizontal rotations, thereby imposing stricter requirements on the coordination between the position and attitude channels. The experimental results are shown in the figure: the red dashed line represents the reference trajectory, the blue solid line denotes the actual trajectory, the blue point indicates the starting position, and the red point marks the end position.

Figure 10.

Performance metrics of the quadrotor under the helical trajectory.

In the helical trajectory tracking experiment, both the three-dimensional trajectory and its x–y plane projection demonstrate a high degree of consistency between the UAV’s actual path and the reference trajectory. Although slight phase lags are observed in regions of high curvature, the deviations are minimal, decay rapidly, and do not accumulate into drift. This indicates that the controller effectively handles the pronounced nonlinearities and strong coupling inherent in helical maneuvers, achieving favorable dynamic response and steady-state accuracy. Meanwhile, the altitude channel remains smooth during both ascent and descent, with virtually no overshoot, reflecting the stability of thrust allocation and total thrust balancing.

The attitude responses further reveal the cooperative characteristics of the control system under complex maneuvers. During the helical maneuver, the roll and pitch angles exhibit periodic variations with amplitudes confined within reasonable bounds, showing only transient spikes at acceleration and deceleration transitions that quickly recover. The yaw angle closely tracks the reference signal, ensuring that the vehicle consistently maintains the correct tangential orientation. Considering both position and attitude results, the system demonstrates strong robustness and convergence in helical trajectory tracking, thereby providing effective support for UAV operations in complex environments.

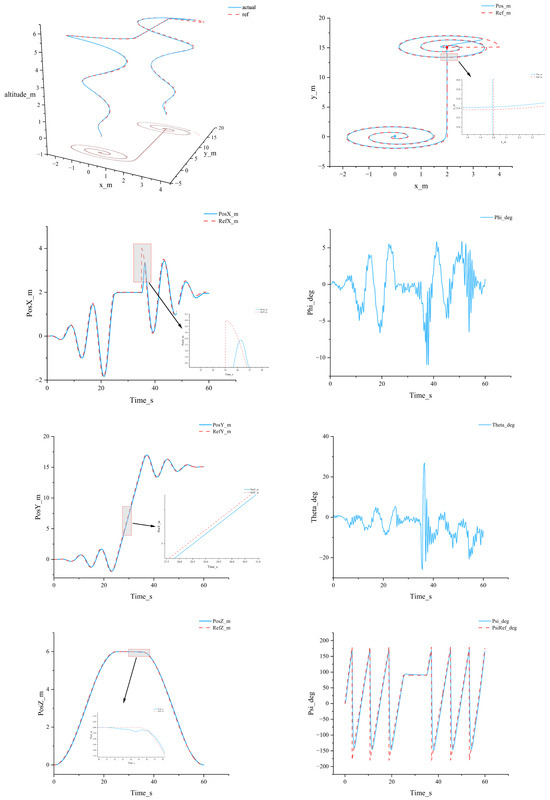

Figure 11 shows corresponds to an aerial figure-eight maneuver. The three-dimensional trajectory and its x–y projection demonstrate that the actual path aligns geometrically with the reference curve around the double loops and intersection regions, with no cumulative drift observed. The temporal responses of x and y exhibit slight phase lead (or lag) and minor undershoot (or overshoot) at curvature reversals and intersection points, but these deviations recover rapidly, consistent with the transient demands of centripetal acceleration during the figure-eight maneuver. The z-channel reaches the commanded altitude within a few seconds and remains stable, with only minor ripples at the top and no evident overshoot, indicating proper thrust balancing and altitude-loop damping configuration. Regarding attitude responses, and increase moderately at the loop apexes and curvature peaks to provide the required lateral centripetal force, while spikes and ripples remain short-lived and within controllable amplitudes. The yaw angle remains close to zero with only minor fluctuations, validating the decoupling effectiveness of the heading-hold strategy. Similarly to the helical case, errors are primarily concentrated within the short time windows of “high curvature or velocity transitions”. Their magnitudes are small and decay rapidly, indicating that the system possesses strong convergence and robustness.

Figure 11.

Performance metrics of the quadrotor under the aerial figure-eight maneuver.

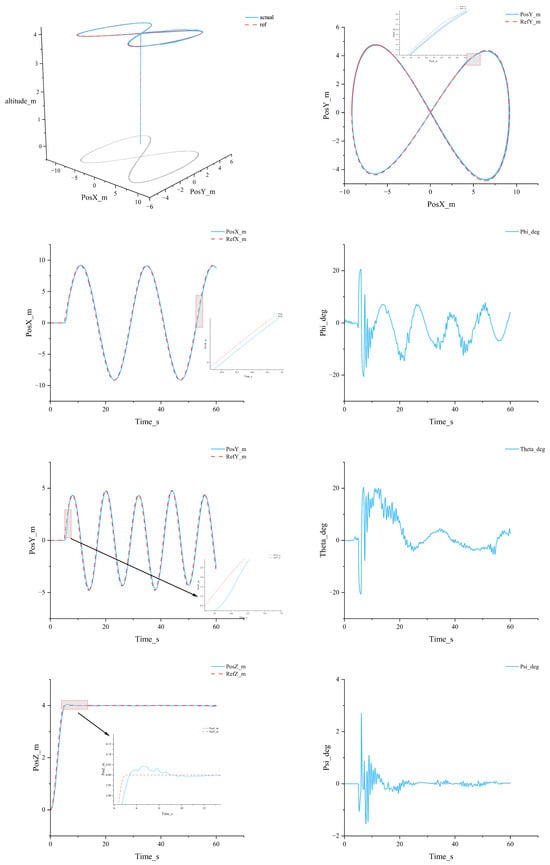

To verify the adaptability and robustness of the proposed control method in practical feeding tasks, a cruise-feeding trajectory simulation in a fishpond environment is designed. The altitude first ascends to an operational layer of approximately 4 m, after which coverage is accomplished following the rhythm of “reciprocal sweeping—turning—entering the next lane”. The three-dimensional trajectory is shown in Figure 12, where the x–y projection indicates a sawtooth-shaped sweeping pattern: the x-axis advances stepwise with each pass, while the y-axis oscillates in a triangular-wave fashion. Correspondingly, the yaw angle executes discrete heading commands at each reversal and settles rapidly, whereas the roll angle exhibits paired peak–valley responses at the corners to generate the lateral centripetal force required for turning. The altitude channel maintains a plateau after reaching the operational layer and responds distinctly to mid-phase minor altitude adjustments, indicating that the task rhythm of “constant-altitude operation with local altitude refinements” is effectively executed. The corresponding three-axis position curves (Figure 12) display short-lived, small-amplitude transitional oscillations after turns, which subsequently decay over time and return to the designated flight path.

Figure 12.

Performance metrics of the quadrotor under the simulated real feeding trajectory.

From the perspective of control division, the outer loop is primarily responsible for velocity constraints and position advancement along straight segments, while at corners it executes heading step commands combined with saturated roll (and pitch) requests to accomplish the “deceleration–turning–reacceleration” process. The inner-loop attitude peaks are confined within the corner windows and quickly decay after the turn is completed, without inducing significant altitude deviations, demonstrating that thrust allocation effectively suppresses the coupling between attitude regulation and altitude holding. The magnified view shows that the residual oscillations of x and y after turning persist for several cycles but gradually attenuate, aligning with the termination of the yaw step command.

In summary, the multi-scenario simulation results presented in Section 4 demonstrate that the proposed method significantly outperforms the comparative approaches in terms of positional accuracy and convergence performance, thereby providing a solid foundation for the subsequent conclusions and practical applications.

5. Conclusions

This study addresses the control challenges of feeding-type UAVs under conditions of variable mass, variable inertia, and wind disturbances and proposes a dual-loop Model Predictive Control (MPC) approach integrated with an Adaptive Niche Radius Genetic Algorithm (ANRGA). By incorporating a time-varying dynamic model that accounts for payload reduction along with low-altitude wind disturbances, a decoupled framework of outer-loop position MPC and inner-loop attitude MPC is established, wherein ANRGA is employed to optimize the controller weights.

Simulation results demonstrate that ANRGA–MPC exhibits outstanding performance in lateral trajectory tracking: the RMSE values in the x- and y-directions are 0.00172 m and 0.00133 m, respectively, representing an accuracy improvement of approximately 45% compared with the least effective algorithm. In terms of the IAE metric, ANRGA achieves 0.0182 along the y-axis, significantly outperforming GA (0.0310) and POA (0.0272). For the vertical z-direction, the RMSE remains stable at 0.411 m. Although affected by payload reduction, ANRGA continues to maintain robust performance.

Theoretical analysis based on the small-gain theorem establishes the asymptotic stability of the closed-loop system, further confirming the feasibility of the proposed method. Overall, the proposed approach outperforms the comparative algorithms in trajectory accuracy, robustness, and convergence performance, offering a viable solution for precision feeding and complex-environment operations of aquaculture UAVs, while also showing potential for extension to agricultural plant protection and multi-UAV cooperative applications.

6. Discussion and Future Work

This study is simulation-based, and the genetic optimization remains an offline step, while the controller executed on board is the constrained dual-loop MPC that solves a deterministic quadratic program each cycle. For deployment we will first fix the control period and the solver budget, then select prediction and control horizons that match plant bandwidth and the available cycle time, form the problem with sparse or block structured matrices, warm start from the previous optimal sequence, generate target specific code that uses static workspaces with bounded memory, and supervise timing with a watchdog that applies a safe fallback such as holding the last feasible input or switching to a prevalidated backup law in rare solver overruns. This approach leaves the control law unchanged and makes timing and memory predictable on embedded avionics. A staged validation path will be followed that moves from software in the loop with the flight stack to processor in the loop timing on the target device, then bench tests of actuator and sensor timing, and finally restrained outdoor trials, with acceptance based on per step solver time within budget, absence of missed deadlines over long runs, and tracking performance consistent with the simulated wind profiles. For multi agent operation the architecture can be extended by augmenting the outer loop with separation and collision avoidance constraints or by inserting a reference governor that accounts for neighbor states while the inner attitude loop remains unchanged; practical deployment then addresses limited bandwidth, packet drops, and asynchronous updates using either decentralized MPC with locally communicated states or a hierarchical scheme where a coordinator provides feasible waypoints and each vehicle solves its own MPC, in all cases keeping the genetic optimization offline per vehicle class. Beyond the linearized regime we will investigate nonlinear MPC or an LPV-based variant to relax small-angle assumptions for aggressive maneuvers and large attitude excursions, applying the same deployment discipline of fixed time budget, structure-exploiting solvers, warm starts, and watchdog with safe fallback to balance accuracy against computation. Finally, to enhance adaptivity under variable mass and wind, we plan to integrate vision or other sensor-based feedback for state, disturbance, and parameter estimation, for example, visual odometry, airspeed, or wind estimation, fused through a Kalman-type filter with event-triggered updates, so that model parameters and disturbance estimates are refined online without changing the optimization structure. This roadmap does not alter the reported results, but it explicitly demonstrates how the present design can transition from simulation to embedded implementation and how it can scale to coordinated multi-agent missions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Q. and X.M.; methodology, H.Q. and X.L. (Xiwen Luo); software, Y.Y.; resources, W.X.; data curation, W.X.; writing—original draft preparation, W.X.; writing—review and editing, X.L. (Xiaohao Li); project administration, H.Q.; funding acquisition, X.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Construction Projects In Specific Universities, grant number 2023B10564002; Jiangsu Provincial Key Research and Development Program, grant number BE2022366; The Open Fund of Key Laboratory of Smart Agricultural Technology (Yangtze River Delta), Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, grant number KSAT-YRD2024008.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

| Algorithm A1. Optimization Process of MPC |

|

References

- Subasinghe, R.; Soto, D.; Jia, J. Global Aquaculture and Its Role in Sustainable Development. Rev. Aquac. 2009, 1, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béné, C.; Arthur, R.; Norbury, H.; Allison, E.H.; Beveridge, M.; Bush, S.; Campling, L.; Leschen, W.; Little, D.; Squires, D. Contribution of Fisheries and Aquaculture to Food Security and Poverty Reduction: Assessing the Current Evidence. World Dev. 2016, 79, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genschick, S.; Kaminski, A.M.; Kefi, A.S.; Cole, S.M. Aquaculture in Zambia: An Overview and Evaluation of the Sector’s Responsiveness to the Needs of the Poor; CGIAR Research Program on Fish Agri-Food Systems: Lusaka, Zambia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kassam, L. Assessing the Contribution of Aquaculture to Poverty Reduction in Ghana. Ph.D. Thesis, SOAS University of London, London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, J.; Leung, P.; Hishamunda, N. Commercial Aquaculture and Economic Growth, Poverty Alleviation and Food Security. Assessment Framework; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Shamsuzzaman, M.M.; Mozumder, M.M.H.; Mitu, S.J.; Ahamad, A.F.; Bhyuian, M.S. The Economic Contribution of Fish and Fish Trade in Bangladesh. Aquac. Fish. 2020, 5, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sribhibhadh, A. Role of Aquaculture in Economic Development Within Southeast Asia. J. Fish. Board Can. 1976, 33, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, B.; Sun, X.; Hong, Q.; Duan, Q. Intelligent Fish Feeding Based on Machine Vision: A Review. Biosyst. Eng. 2023, 231, 133–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, J.; Li, D.; Qiao, X.; Rauschenbach, T. Integrated Navigation for Autonomous Underwater Vehicles in Aquaculture: A Review. Inf. Process. Agric. 2020, 7, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Wei, Q.; An, D. Intelligent Monitoring and Control Technologies of Open Sea Cage Culture: A Review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 169, 105119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Duan, Y.; Wei, Y.; An, D.; Liu, J. Application of Intelligent and Unmanned Equipment in Aquaculture: A Review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 199, 107201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Xu, Y.; Sun, L.; Chen, Z.; Feng, J.; Wu, X. Development Status and Prospect of Aviation Plant Protection in China. Agrochemicals 2022, 61, 469–477. [Google Scholar]

- De Lima, R.L.P.; Paxinou, K.; Boogaard, F.C.; Akkerman, O.; Lin, F.-Y. In-Situ Water Quality Observations under a Large-Scale Floating Solar Farm Using Sensors and Underwater Drones. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Zhang, R.; Yang, J.; Chen, L. Development Status and Key Technologies of Plant Protection UAVs in China: A Review. Drones 2022, 6, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, J.; Xiang, Y.; Geng, H.; Yang, X.; Yang, N.; Du, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, L. Improving UAV Hyperspectral Monitoring Accuracy of Summer Maize Soil Moisture Content with an Ensemble Learning Model Fusing Crop Physiological Spectral Responses. Eur. J. Agron. 2024, 160, 127299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, F.; Tian, X.; Ge, S.; Man, C.; Xiao, M. Research on Precise Feeding Strategies for Large-Scale Marine Aquafarms. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Lan, Y.; Fritz, B.K.; Clint Hoffmann, W.; Liu, S. Review of Agricultural Spraying Technologies for Plant Protection Using Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV). Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2021, 14, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijaz, S.; Shi, Y.; Khan, Y.A.; Khodaverdian, M.; Javaid, U. Robust Adaptive Control Law Design for Enhanced Stability of Agriculture UAV Used for Pesticide Spraying. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2024, 155, 109676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, K.; Asadi, D.; Nabavi-Chashmi, S.-Y.; Tutsoy, O. Modified Adaptive Discrete-Time Incremental Nonlinear Dynamic Inversion Control for Quad-Rotors in the Presence of Motor Faults. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 188, 109989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Ahn, C.K.; Liu, D.; Wang, W.; Zhang, C. Near-Asteroid Spacecraft Formation Control with Prescribed-Performance: A Dynamic Event-Triggered Reinforcement Learning Control Approach. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2025, 161, 110138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Ozguner, U. Sliding Mode Control of a Quadrotor Helicopter. In Proceedings of the 45th IEEE Conference on Decision and Control, San Diego, CA, USA, 13–15 December 2006; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 4957–4962. [Google Scholar]

- Gautam, D.; Ha, C. Control of a Quadrotor Using a Smart Self-Tuning Fuzzy PID Controller. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2013, 10, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pounds, P.E.I.; Bersak, D.R.; Dollar, A.M. Stability of Small-Scale UAV Helicopters and Quadrotors with Added Payload Mass under PID Control. Auton. Robot. 2012, 33, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapnopoulos, A.; Alexandridis, A. A Cooperative Particle Swarm Optimization Approach for Tuning an MPC-Based Quadrotor Trajectory Tracking Scheme. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2022, 127, 107725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Abdi, S.; Debilou, A.; Guettal, L.; Guergazi, A. Robust Trajectory Tracking Control of a Quadrotor under External Disturbances and Dynamic Parameter Uncertainties Using a Hybrid P-PID Controller Tuned with Ant Colony Optimization. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2025, 160, 110053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, H.; Li, N.; Yao, P.; Huang, Y.; Su, Z.; Yu, Y. Distributed Trajectory Optimization for Multiple Solar-Powered UAVs Target Tracking in Urban Environment by Adaptive Grasshopper Optimization Algorithm. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2017, 70, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trad, T.Y.; Choutri, K.; Lagha, M.; Meshoul, S.; Khenfri, F.; Fareh, R.; Shaiba, H. Real-Time Implementation of Quadrotor UAV Control System Based on a Deep Reinforcement Learning Approach. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2024, 81, 4757–4786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caffyn Yuste, P.; Iglesias Martínez, J.A.; Sanchis De Miguel, M.A. Simulation-Based Evaluation of Model-Free Reinforcement Learning Algorithms for Quadcopter Attitude Control and Trajectory Tracking. Neurocomputing 2024, 608, 128362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gün, A. Attitude Control of a Quadrotor Using PID Controller Based on Differential Evolution Algorithm. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 229, 120518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Li, Y.; Zeng, J.; Wu, G.; Wang, Y. Quadrotor Navigation Considering Attitude: A Deep Reinforcement Learning Method Using Tangent Path Rewards. Expert Syst. Appl. 2026, 298, 129762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, S.; Wang, H. Parameter Optimization Design of MPC Controller in AUV Motion Control Based on Improved Black-Winged Kite Algorithm. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Liu, S.; Xue, W.; Ding, Y.; Li, D. Disturbance-Rejection Guaranteed Mpc Design for Mimo Systems with Application to a 2-Dof Helicopter. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2025, 168, 110757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Tang, J.; Liu, M.; Li, Y.; Chen, H.; Cao, D. A Data-Driven Neural Model Predictive Controller for Multi-Layer Nonlinear Vibration Isolation System. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2025, 166, 110583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberge, V.; Tarbouchi, M.; Labonte, G. Fast Genetic Algorithm Path Planner for Fixed-Wing Military UAV Using GPU. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2018, 54, 2105–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; He, C.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, X. Efficient Trajectory Planning for UAVs Using Hierarchical Optimization. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 60668–60681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X.; Ren, J.; Hua, Y.; Li, Q. Online Nonparametric Identification Modeling of Ship Maneuvering Motion Based on PSO-Optimized Incremental Gaussian Mixture Model. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 160, 111962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Zeng, H.; Yin, L. Dynamic Distributed Multi-Objective Mantis Search Algorithm Based on Transformer Hybrid Strategy for Novel Power System Dispatch. Energy 2025, 332, 136075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffo, G.V.; Ortega, M.G.; Rubio, F.R. An Integral Predictive/Nonlinear H∞ Control Structure for a Quadrotor Helicopter. Automatica 2010, 46, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, E.-H.; Xiong, J.-J.; Luo, J.-L. Second Order Sliding Mode Control for a Quadrotor UAV. ISA Trans. 2014, 53, 1350–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).