Abstract

In the field of second language acquisition (SLA) and language teaching, willingness to communicate (WTC), a construct of oral communication, has been extensively researched as it is considered a facilitative factor for language development. Most studies examine this construct using the quantitative method. There are fewer studies that have examined how languages are codeswitched and used interchangeably across different social domains, a common practice among Malaysian English language users. The purpose of this research was to develop and validate a WTC measuring tool for Malaysian English language learners. In the questionnaire, WTC in English was examined and determined via four language use domains—education, friendship, transaction and family. The validity of the four domain factors was tested using the two-stage approach factor analysis. The results suggest that WTC can be seen as a domain-based construct where learner social domains are contextualized. This paper aims to briefly introduce the study and presents its validation results.

1. Introduction

Willingness to communicate (WTC) plays a crucial role in facilitating oral interaction among speakers. The term was coined [1] and defined as the inclination to participate in an interaction when there is an opportunity for it. This idea was shaped by other studies [2,3] who investigated the reluctance of native speakers to engage in communication.

Although various variables that influence a native speaker’s WTC communication competence have been identified (for example, communication anxiety, introversion, self-efficacy, and cultural diversities), early studies on WTC of native speakers primarily focused on its link to personality attributes. Native speaker WTC has also been examined across several different communication settings as well as involving different types of recipients [4]. As a result of these personality-based studies, WTC is seen as a construct that remains mostly constant across various communicative situations. This native speaker view, or the L1 view, of WTC, however, is in contradiction to the second language speaker view, or the L2 view, posited by [5].

In the L2 context, WTC is defined as the psychological preparedness to interact in the target language when the opportunity arises. The manifestation of WTC among L2 speakers is different from L1 speakers as they generally have high oral competency and therefore the situation is rather simple, without any issues [5]. This however is not the case for L2 speakers whose oral competency levels could range from the lowest to the highest. Authors [5] believe that WTC among L2 speakers is dependent on the context as their predisposition to interact seems to be contingent on the situational condition that is different in each context. Given this, [6] included situation-bound contextual variables such as the topic, interactants, magnitude of the communicative group, and cultural setting to facilitate his research on WTC of Korean L2 speakers.

In addition, [5] also points out that there are many intergroup issues in the L2 context that have social and political ramifications. In Malaysia, for example, to ensure the unity of its multiethnic and multilingual population, Malay, the country’s official language, is to be used as a language of unity. English, on the other hand, is seen as a global language—a language of international business, diplomacy, knowledge, technology etc. [7]. Because of the complex linguistic landscape of the country, an exploration of this crucial communication construct is warranted to avoid the over-generalisation of WTC in the L2 setting.

1.1. The WTC Scale

To identify the WTC levels of L2 learners, an adapted version of the WTC scale developed by [8] is usually employed. The instrument determines the WTC of language learners through their scores in four context-based situations: (1) group discussion, (2) meetings, (3) interpersonal interaction, and (4) public speaking. Additionally, it measures WTC in terms of the scores of the recipients which include strangers, acquaintances and friends. Most of the studies that have employed this instrument have been conducted in Western countries, particularly America and Canada [9,10,11]. Over in Asia, similar studies have been conducted in Japan [12,13,14] and China [4,15].

As noted by [16], these L2 studies view WTC from a monolithic perspective, the East versus the West perspective. She argues that given the pluralistic nature of Malaysia, WTC should be approached from a pluralistic viewpoint as it would be more representative of its society. Following this argument, the present study considered two variables—socio-cultural and psychological—in its investigation of WTC. These factors are particularly pertinent to an ethnically and linguistically diverse country such as Malaysia.

This study measured the WTC in English of Malaysian undergraduates in four language use domains—education, family, friendship, and transaction—as outlined by [17]. This selection was also guided by specifications stated in government documents that touched on language policy and use such as the Rahman Talib Report and Tenth Malaysia Plan. Besides official documents, media also play a role in influencing the way Malaysians think and what they express in certain language domains [18].

1.2. Language Use Domain

Studies on language use domains describe the language choices of speakers, which are determined by the individuals they are conversing with, the conversation topic, and the location of the conversation. Their language choice is further confined by the cultural norms and social expectations of their society [17,19].

Discourse on language use is of particular relevance to Malaysia given its linguistically diverse society where it is common to code switch and use more than one language when communicating in some social domains [17,20]. Researchers such as [21,22,23,24,25] feel that in the context of a multilingual society, the decision on which language to use in a particular language domain is determined largely by the interactants, their relationships, the discussion topic and the setting.

The domains of language use are also discussed in relation to the familiarity among the interactants. Typical interactions between typical participants in typical settings create a domain [26]. A study by Platt links the domain to the continuum of formality [27]. In tandem with this view, it is stated that the degree of formality in a domain is dependent on the outcome intended by the interactants [28]. For example, if the intention is to create an air of elitism, a formal code might be preferred while a more casual less formal code might be preferred to foster a sense of friendliness and kinship.

Another factor that affects language use choices is the social organization (the family, community, educational institution, workplace, etc.) that individuals are in [29]. Comparatively, the educational and workplace settings are likely to be more formal than the friendship and family settings.

Additionally, the government language policies also influence what language would be used in an institution and/or organisation. This is relevant for the Malaysian context where English is taught as a subject in schools. In other words, the elements of language use construct such as the discussion topic, relationship, setting, and formality are crucial to an understanding of the language choices that individuals made. For these reasons, this study aimed to focus on the education, transactional, friendship and family domains to study WTC in English among Malaysian undergraduates.

2. Method

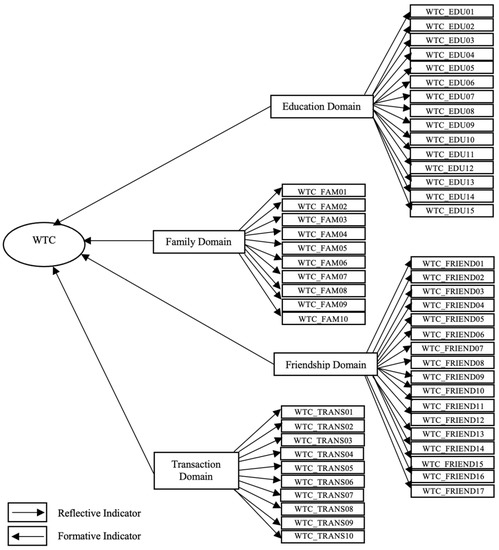

The respondents were 540 undergraduates from a public university in Malaysia selected using proportionate quota sampling. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences Program (SPSS) version 17 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used to analyse the data collected. After the data were analysed and assessed, structural equation modelling (SEM) was utilised. The second-order model presented in Figure 1 was validated using the two-stage approach in SmartPLS 2.0.M3 software (SmartPLS2., Hamburg, Germany). Each item in the questionnaire is a reflective indicator of its domain in the model while each domain is the formative indicator of WTC in English. Hence, a complete measurement model of WTC in English for Malaysian language learners was developed.

Figure 1.

The measurement model of WTC.

3. Results

The measurement model of WTC in English was validated statistically. First, factor analysis of the reflective-formative hierarchical component model (HCM) of the WTC construct was conducted using a two-stage approach. For the first stage, the first or lower order components of the reflective measurement model were evaluated whereas the second stage involved the evaluation of the second or higher order components of the formative measurement model.

3.1. Reflective Measurement Model

The reflective measurement model determines the validity and reliability of the questionnaire items or indicators. For this study, two types of validity assessment were conducted: (1) convergent validity and (2) discriminant validity.

“Convergent validity is the degree to which indicators of a specific construct converge or share a high proportion of variance in common” [30]. Both factor loadings and average variance extracted (AVE) were used to assess the convergent validity of these indicators [31]. The indicator loadings, AVE, and composite reliability (CR) of the reflective construct of WTC in the four domains of language use are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

WTC in English, reflective measurement model.

Items with loadings higher than 0.708, as suggested by [31], were retained while the others were omitted. These low loading items, WTC_EDU5, 7, 12, 13 and 16, were from the education construct and are not depicted in Table 1. With their omission, the loading for WTC_EDU15 fell from 0.705 to 0.692. Therefore, this item remained since the total loading scores are high with its inclusion. Furthermore, the AVE score is more than 0.5, which is acceptable [32]. The four constructs also attained the threshold values for CR and AVE. CR scores for all four domains are greater than 0.7 while the AVE scores are greater than 0.5 after the item deletion [31]. It can be concluded that the requirements for reliability and convergent validity of the four domains of the WTC construct have been attained.

To determine the discriminant validity of the model, the Fornell–Larcker indicators were used (see Table 2 for the results). According to [33], the indicators should load more strongly within the same construct compared to the other constructs of the model. Furthermore, the average variance of each construct and its measure should be more than the variance shared between the construct and other constructs. As indicated in Table 2, all the constructs attained satisfactory discriminant validity [33], that is, the square root of AVE (diagonal) is larger than the correlations (off-diagonal) of the four reflective constructs.

Table 2.

Discriminant validity using the Fornell-Larcker criterion.

Based on the results of the Fornell–Lacker discriminant validity test, it can be concluded that the construct WTC in English in the education, friendship, transaction, and family domains met the requirement of discriminant validity for the reflective measurement model.

3.2. Formative Measurement Model

A three-step approach that involved determining the convergent validity, addressing collinearity issues, and assessing the significance and relevance of the formative indicators was used to establish the validity of the formative measurement model for this HCM. The measurement properties of the formative construct of WTC are indicated in Table 3.

Table 3.

Measurement properties of the formative construct WTC.

Results of the redundancy analysis indicate that the path coefficient of 0.728 is bigger than 0.7. This means that the WTC formative construct has a satisfactory level of convergent validity [34]. Besides, the Varian Inflation Factor (VIF) values are all lower than the threshold value of 5 [31]. In addition, the collinearity does not reach a critical level in any of the formative construct indicators and therefore it can be used for estimating the Partial Least Square (PLS) path model.

As to the significance level, three of the WTC constructs (education, friendship and transaction) were found to be significant whereas the family domain was insignificant. By employing Hair et al.’s [31] absolute contribution method, the loading value was 0.640 and the t-value was 15.414. Thus, the family domain was retained. In conclusion, the results proved the validity and reliability of the reflective-formative measurement model for the WTC in English.

4. Conclusions

This research on WTC in English examines the interchangeable use of languages in the daily lives of Malaysians within and across the four language use domains of education, friendship, transaction, and family. It is quite usual for Malaysians to be able to converse in two or more languages and to codeswitch between them in their daily interaction. Furthermore, language policies (Malay as a language of unity and public domains; English as a global language and a language of knowledge and technology) dictate that one language is used more than another in specific domains. The validated WTC scale for Malaysian English language learners, which is reflective of the unique local social and linguistic landscape, is a valuable contribution to research in the area.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.N.A.R. and A.N.A.; methodology, F.N.A.R.; software, F.N.A.R. and N.I.A.R.; validation, F.N.A.R. and V.N.; formal analysis, F.N.A.R.; writing—original draft preparation, F.N.A.R.; writing—review and editing, A.N.A. and V.N.; supervision, A.N.A. and V.N.; funding acquisition, F.N.A.R. and N.I.A.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Universiti Putra Malaysia under the Putra Grant—Putra Graduate Initiative (GP-IPS/2018/9631200) and UiTM Cawangan Negeri Sembilan.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Paper presented at the International Academic Symposium of Social Science 2022 by the first author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- McCroskey, J.C.; Baer, J.E. Willingness to communicate: The construct and its measurement. In Proceedings of the Annual Convention of the Speech Communication Association, Denver, CO, USA, 7–10 November 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Burgoon, J.K. The unwillingness-to-communicate scale: Development and validation. Commun. Monogr. 1976, 43, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortensen, C.D.; Arntson, P.H.; Lustig, M. The measurement of verbal predispositions: Scale development and application. Hum. Commun. Res. 1977, 3, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.M. Willingness to Communicate in English among Secondary School Students in the Rural Chinese English as a Foreign Language (EFL) Classroom. Doctoral Dissertation, AUT University, Auckland, New Zealand, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- MacIntyre, P.D.; Clément, R.; Dörnyei, Z.; Noels, K.A. Conceptualizing willingness to communicate in a L2: A situational model of L2 confidence and affiliation. Mod. Lang. J. 1998, 82, 545–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.J. Dynamic emergence of situational willingness to communicate in a second language. System 2005, 33, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.K. Language policy in Malaysia: Reversing direction. Lang. Policy 2005, 4, 241–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCroskey, J.C. Reliability and Validity of the Willingness to Communicate Scale. Commun. Q. 1992, 40, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clément, R.; Baker, S.C.; MacIntyre, P.D. Willingness to communicate in a second language. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 22, 190–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIntyre, P.; Baker, S.; Clément, R.; Conrod, S. Willingness to Communicate, Social Support, and Language-learning Orientations of Immersion Students. Stud. Second Lang. Acquis. 2001, 23, 369–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIntyre, P.; Baker, S.; Clément, R.; Donovan, L. Talking in order to Learn: Willingness to Communicate and Intensive Language Programs. Can. Mod. Lang. Rev. 2003, 59, 589–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, Y. Motivation and Willingness to communicate as predictors of L2 use. Second Lang. Stud. 2002, 20, 29–70. [Google Scholar]

- Yashima, T. Willingness to communicate in a second language: The Japanese EFL context. Mod. Lang. J. 2002, 86, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashima, T.; Zenuk-Nishide, L.; Shimizu, K. The influence of attitudes and affect on willingness to communicate and second language communication. Lang. Learn. 2004, 54, 119–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.E. Willingness to communicate in an L2 and integrative, motivation among college students in an intensive English language program in China. Univ. Syd. Pap. TESOL 2007, 2, 33–59. [Google Scholar]

- Saidi, S.B. Willingness to Communicate in English among Malaysian Undergraduates: An Identity-Based Motivation Perspective. Doctoral Dissertation, University of York, Heslington, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fishman, J.A. Language in Sociocultural Change; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Abd Razak, F.N.; Nimehchisalem, V.; Nadzimah, A. The relationship between ethnic group affiliation (EGA) and willingness to communicate (WTC) in English among undergraduates in a public university in Malaysia. Int. J. Appl. Linguist. Engl. Lit. 2018, 7, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granhemat, M. Language Choice and Use among Undergraduates at a Malaysian Public University. Doctoral Dissertation, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Seri Kembangan, Malaysia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, H.; Smith, P.M. Accommodation Theory: Optimal Levels of Convergence; Giles, H.S., Clair, R.N., Eds.; Peter Lang: New York, NY, USA, 1979; pp. 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, A.R.M.; Chan, S.H.; Abdullah, A.N. What determine the choice of language with friends and neighbors? The case of Malaysian university undergraduate. Lang. India 2008, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, C.C. Language Choices of Malaysian Youth: A Case Study. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Burhanudeen, H. Language and Social Behavior: Voices from the Malay World; Penerbit Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia: Bangi, Malaysia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, H.; Chan, H.; Cheng, Y. Language Use in Taiwan: Language Proficiency and Domain Analysis. J. Taiwan Norm. Univ. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2004, 49, 75–108. [Google Scholar]

- Parasher, S.N. Mother-Tongue-English Diglossia: A Case Study of Educated Indian Bilinguals’ Language Use. Anthropol. Linguistics. 1980, 22, 151–168. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, J. An Introduction to Sociolinguistics, 2nd ed.; Longman: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Platt, J.T. A Model for Polyglossia and Multilingualism (With Special Reference to Singapore and Malaysia). Lang. Soc. 1977, 6, 361–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasiorek, J.; Giles, H. Accommodating the Interactional Dynamics of Conflict Management. Iran. J. Soc. Cult. Lang. 2013, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, A. Sociology; Blackwell Publishers: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.J.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modelling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, R.D.; Whybark, D.C. The Impact of Environmental Technologies on Manufacturing Performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1999, 42, 599–615. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).