The Use of Film in Geography and History Classes: A Theoretical Approach †

Abstract

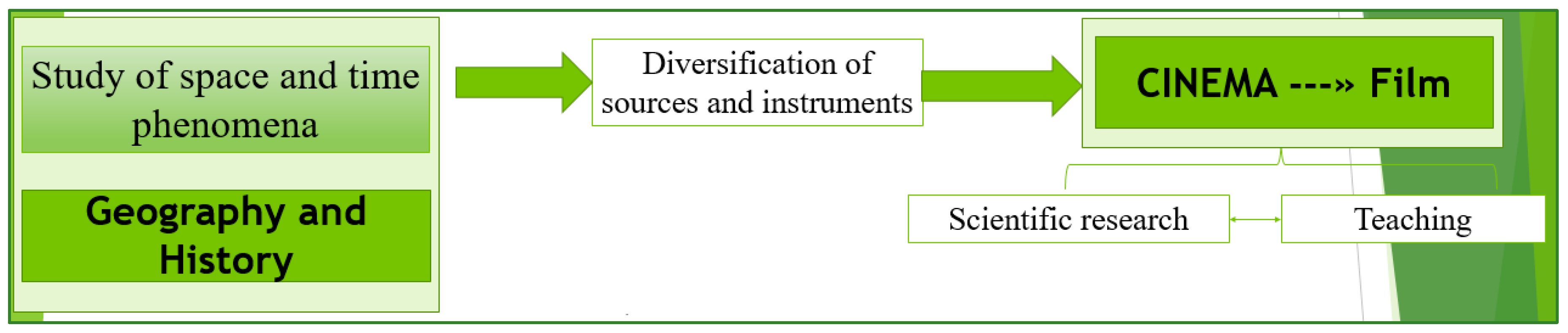

:1. Introduction

2. Discussion

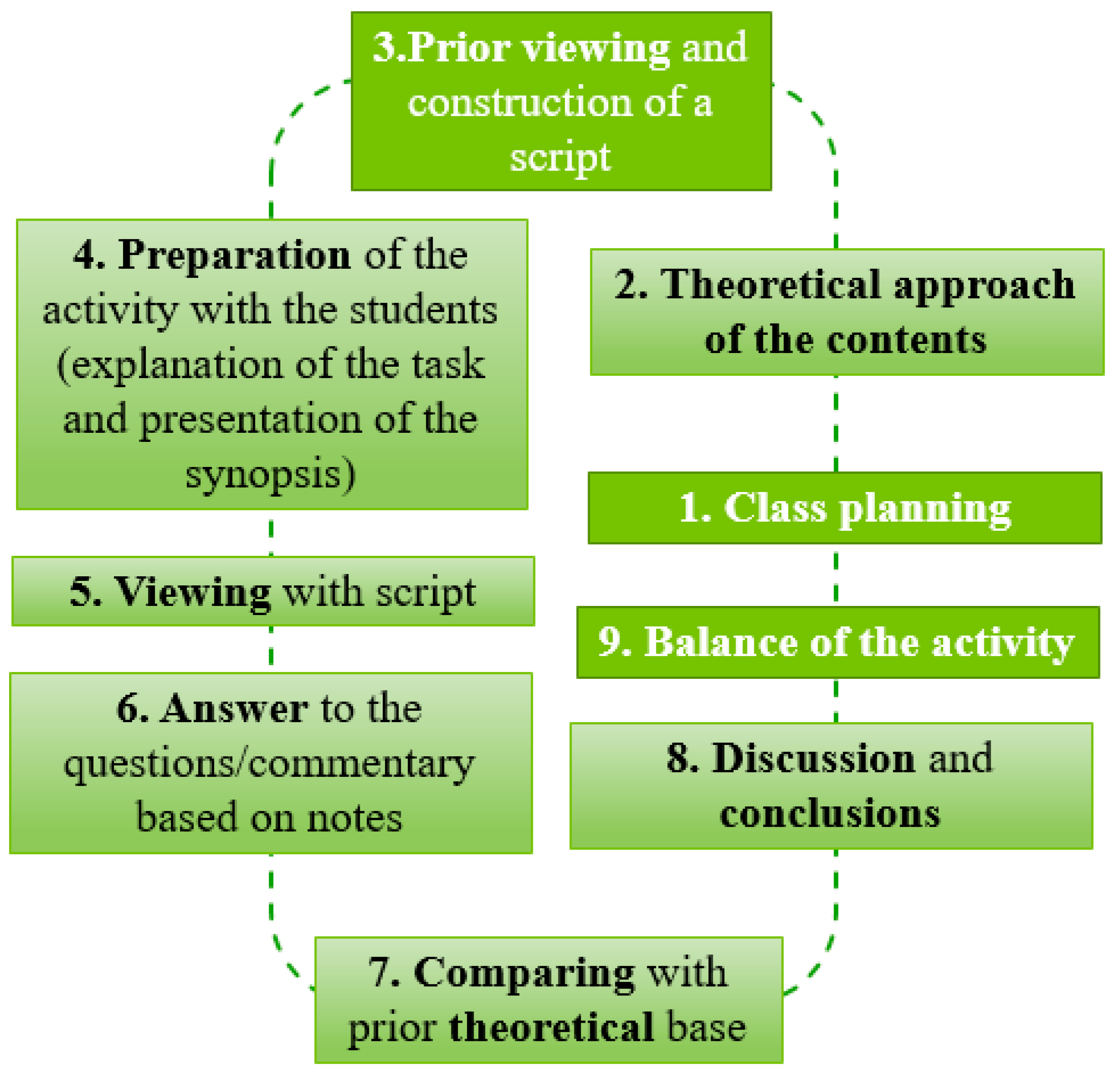

3. Proposal

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Santos, M. A Natureza do Espaço: Técnica e Tempo, Razão e Emoção, S.Paulo Editora da Universidade de S.Paulo, 4th ed.; Editora da Universidade de São Paulo: São Paulo, Brasil, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo, A.F. Geografia e Cinema. Representações Culturais do Espaço, Lugar e Paisagem na Cinematografia Portuguesa; University of Minho: Braga, Portugal, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Lez, J.A. Cinema e Literatura, A Metáfora Visual; Campo das Letras: Porto, Portugal, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, J.L. A paisagem urbana simbólica enquanto território efémero de celebração do marketing territorial—o caso particular das Christmascapes. In Atas do VII Congresso da Geografia Portuguesa; 2004; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Deshpand, A. Films as historical sources or alternative history. Econ. Political Wkly. 2004, 2–8, 4455–4459. [Google Scholar]

- Ferro, M. Cinema and History; Wayne State University Press: Detroit, MI, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- De Castro, F.V.; de Almeida, A.C. Anatopias cinematográficas em contexto geográfico. Contributo para a (des)construção de paisagens imaginadas. In Representações e Paisagens da Pós-Modernidade; de Castro, F.V., Fernandes, J.L., do Cinema, T., Eds.; Eumed-Universidade de Málaga: Málaga, Spain, 2016; pp. 163–180. [Google Scholar]

- Sarmento, J.; Azevedo, A.F.; Pimenta, J.R. Ensaios de Geografia Cultural; Figueirinhas: Porto, Portugal, 2006. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Castro, F.V.d. The Use of Film in Geography and History Classes: A Theoretical Approach. Proceedings 2018, 2, 1360. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2211360

Castro FVd. The Use of Film in Geography and History Classes: A Theoretical Approach. Proceedings. 2018; 2(21):1360. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2211360

Chicago/Turabian StyleCastro, Fátima Velez de. 2018. "The Use of Film in Geography and History Classes: A Theoretical Approach" Proceedings 2, no. 21: 1360. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2211360

APA StyleCastro, F. V. d. (2018). The Use of Film in Geography and History Classes: A Theoretical Approach. Proceedings, 2(21), 1360. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2211360