Abstract

The paper aims to investigate challenges faced by fishing communities in developing fishing tourism. Using a case study approach and qualitative research methods, it explores fishing tourism in Thermaikos and Strymonikos Gulf (Thessaloniki, Northern Greece). This is an alternative form of tourism which was initiated by the local LEADER/CLLD Fisheries and Marine Operational Program 2014–2020. A semi-structured questionnaire was designed to conduct in-depth interviews, and a snowball sampling technique was used to select participants. Thematic content analysis elaborates on challenges faced by those fishing communities (mainly economic and cenvironmental) that hinder the sustainability of fishing communities and their livelihood. Findings are presented through an Ishikawa (fishbone) diagram, illustrating the cause-and-effect relationships underlying the challenges identified. To promote the well-being of local fishing communities and ensure the sustainability of fishing tourism, the paper recommends legislative reforms and empowerment of fishermen/women through targeted educational initiatives. These recommendations also serve as potential directions for future research.

1. Introduction

Coastal fisheries face significant sustainability challenges that necessitate action towards mitigating ecological pressure and providing alternative sources of income for fishing communities [1]. Depletion of fish stocks and loss of biodiversity [2] along with overall degradation of the marine ecosystem [3] have led to actions such as those described in the United Nations (UN) 2030 Agenda, which calls for minimizing overfishing and supporting small coastal areas linked to fisheries [4]. The interrelated connection between environmental and economic sustainability [5] requires a common framework for action integrating values, attitudes, and policies [6]. To this end, participatory management of marine resources is required which achieves—in addition to the aforementioned goals—the goal of shaping attitudes and behaviours [7], and seeks innovative alternative entrepreneurial activities in rural coastal areas, among which tourism might have a prominent place.

In fact, many fishing communities in countries such as Italy and France have adopted fishing (or pesca) tourism as an important tool for economic and environmental sustainability [8]. In Greece also, many coastal destinations and fishing communities were recently organized through a national network (funded by the LEADER/CLLD INTER-REGIONAL COOPERATION PROJECT “FISHING TOURISM”, Priority 4 “Increasing employment and territorial cohesion” E. PI. “FISHERIES AND THE SEA 2014–2020”) to promote the idea and the experience of fishing tourism in an attempt to balance lost incomes by providing participatory recreational services to tourists in professional fishing boats [9].

2. Materials and Methods

For the purposes of this case study (Thermaikos and Strymonikos Gulf in Northern Greece, close to the city of Thessaloniki), various qualitative research tools were employed: in-depth interviews with an interview guide, focus group discussions with experts (local key informants), and thematic analysis of media posts regarding fishing tourism in Greece. Overall, material from 7 participants (fishermen/women and experts selected via a snowball sampling technique) was analysed by thematic analysis [10] and presented (theorized) in the form of a cause-and-effect diagram, otherwise known as an Ishikawa fishbone, which helps identify and solve problems and suggest solutions [11].

3. Results

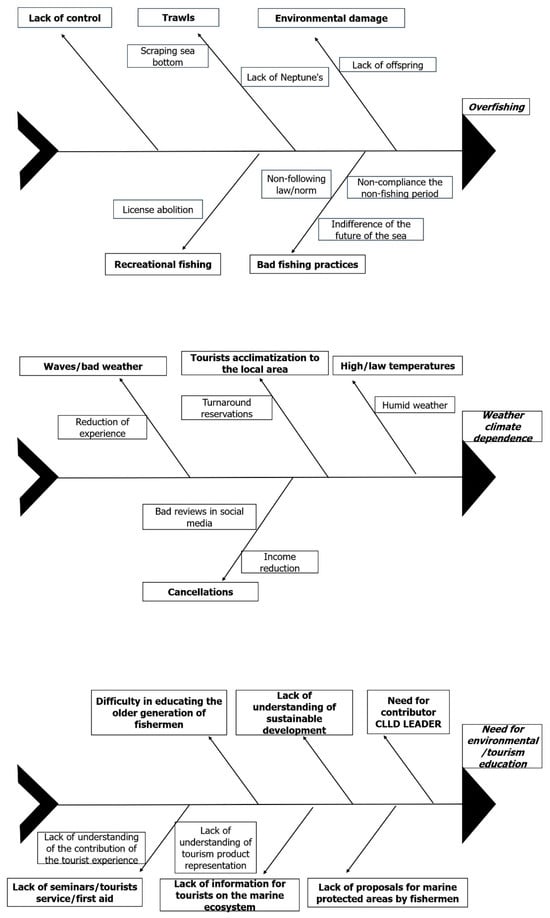

Fishing communities in our case study area face a number of interconnected economic and environmental challenges. From an environmental perspective (Figure 1), overfishing not only contributes to depletion of fish stocks, but also poses a significant threat to marine biodiversity. Certain fishing practices have intensified the degradation of marine resources. These issues, exacerbated by the withdrawal of recreational fishing licenses and poor enforcement of regulations, place increasing pressure on coastal fisheries and local ecosystems. Fishing tourism in the area is less than 5 years old (having been initiated by the local LEADER/CLLD Fisheries and Marine Operational Program 2014–2020), and involves only a handful of fishing families. Adverse weather conditions present an additional obstacle to the development of fishing tourism, often resulting in cancellations or last-minute changes to bookings. These problems frequently lead to negative reviews on social media platforms; these in turn contribute to reductions in local fishers’ incomes, demonstrating the interconnection of environmental and economic dimensions.

Figure 1.

Environmental perspective. Source: Authors’ processing, 2025.

Older fishers often face difficulties in adapting to educational programmes, while development agencies provide only limited support, if any, to facilitate this transition. A lack of specialized seminars and environmental education initiatives directed at fishers limits the development of a shared understanding of marine ecosystems and the principles of sustainable development. Moreover, tourists often receive insufficient information regarding the environmental significance of the coastal regions they visit. Limited recognition of this significance by fishers themselves, who are key stakeholders in this emerging tourism model, alongside an absence of proposals for designation areas, further constrains the advancement of this alternative form of tourism.

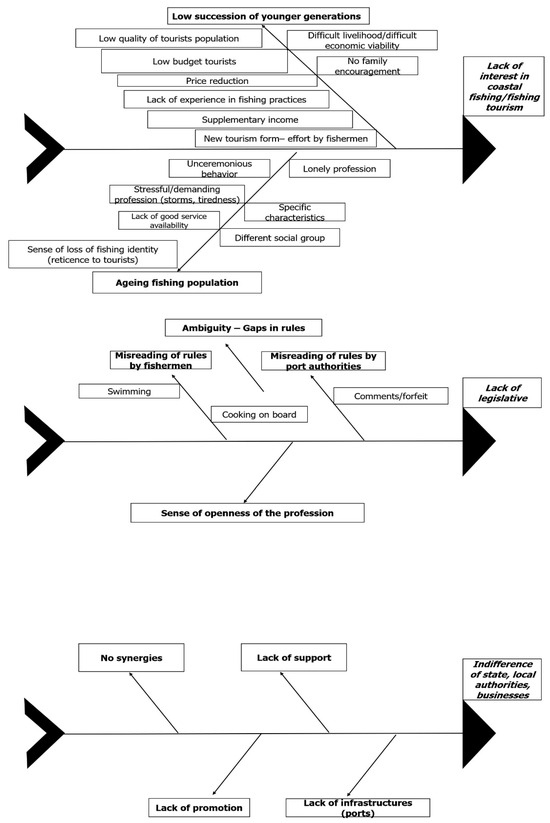

From an economic perspective (Figure 2), fishers reported encountering difficulties with port authorities and personnel, primarily due to misinterpretations of existing regulations. These misinterpretations have led to fines and complaints, and to unintentional violations of the law—particularly in relation to a lack of clear provisions concerning activities such as swimming or cooking on board fishing vessels. Minimal to non-existent support from local institutions, a lack of cooperation between stakeholders, an almost complete absence of promotional initiatives, and inadequate infrastructure (e.g., the absence of appropriate port facilities) all raise serious concerns regarding the viability of this emerging form of tourism. Moreover, the younger generation shows limited interest in engaging with coastal fisheries or fishing tourism, primarily due to the economic hardship associated with traditional fishing livelihoods, as well as an absence of encouragement from within their families to pursue the profession. In instances where young fishers do engage in fishing tourism, they often serve low-budget tourists. As a result, they are compelled to reduce the price of fishing excursions in order to cover their operational costs. Additionally, younger fishers often lack the experience of their older counterparts, making it more difficult for them to maintain traditional fishing practices, which are essential for the authenticity of the tourism experience.

Figure 2.

Economic perspective. Source: Authors’ processing, 2025.

A general reluctance among fishers to engage in hospitality-related activities aboard their vessels (often linked to perceived threats to their identity and social status) further impedes the development of fishing tourism. As members of a close-knit social group, many fishers exhibit scepticism towards tourists. This reinforces their resistance to engaging in this emerging activity, and institutes an additional barrier to the growth of fishing tourism.

4. Discussion

Coastal fisheries in the case study area do indeed face significant sustainability challenges; these have been much debated in recent years in academic and lay discourses concerning multiple places all over Greece. However, new opportunities associated with fishing tourism have also emerged in recent years; these have been recognised not only in the literature but within EU policy measures as an innovative alternative practice for fishing communities in order to balance loss of income and loss of fish stock. However, the transition towards sustainable fishing tourism is hampered by educational and institutional constraints. The ageing demographic of fishers, the behavioural patterns shaped by the solitary and demanding nature of their profession, and their distinct anthropological traits all present additional challenges. Regulatory ambiguities, combined with the apparent indifference of local authorities and tourism business stakeholders, also significantly hinder the full development of fishing tourism. The LEADER/CLLD programme has indeed stimulated discussion and interest in several parts of the country by advocating the important role of fishing communities in overall rural development.

5. Conclusions

Fishing tourism can be a solution to important economic and environmental problems. However, if fishing tourism is to successfully serve its purpose in small fishing areas, financial support for fishers (to transform their vessels and adapt to the needs of their clientele) and training courses on sustainable practices and tourism skills are crucial. Cooperation between the state, local authorities, and other local tourism entrepreneurs (agritourism small guesthouses, open farms, wineries, etc.) is essential to develop an overall agrotourism experience. Further research should explore training needs, consider best practices to serve as a benchmark, and carry out an analysis of Greece’s legislative framework in comparison with those of other countries in which fishing tourism has been developed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.T. and M.P.; methodology, K.T. and M.P.; validation, K.T. and M.P.; formal analysis, K.T.; investigation, K.T.; resources, K.T.; data curation, K.T.; writing—original draft preparation, K.T. and M.P.; writing—review and editing, K.T. and M.P.; visualization, K.T. and M.P.; supervision, M.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the non-interventional nature of the research and the complete anonymization of the data.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions. Given that the research was conducted within a small-scale fishing community, the data contain sensitive information that could potentially identify the participants, thus compromising their confidentiality.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to all participating fishermen/women and the staff of the Local Action Group ANETH, S.A. of Thessaloniki, Greece.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UN | United Nations |

| LEADER | Liaison Entre Actions de Developpement de l’Economie Rurale |

| CLLD | Community-Led Local Development |

| EU | European Union |

References

- Chen, C.L.; Chang, Y.C. A transition beyond traditional fisheries: Taiwan’s experience with developing fishing tourism. Mar. Pol. 2017, 79, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, S.; Kaiser, M.J. The effects of fishing on marine ecosystems. In Advances in Marine Biology; Academic Press: London, UK, 1998; Volume 34, pp. 201–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, G.; Floris, R.; Serangeli, C.; Di Paola, L. Fishery wastes as a yet undiscovered treasure from the sea: Biomolecules sources, extraction methods and valorization. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNIRIC. Goal 14—Life Below Water. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/goal-14-life-below-water/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Baumgärtner, S.; Quaas, M. What is sustainability economics? Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limburg, K.E.; Hughes, R.M.; Jackson, D.C.; Czech, B. Human population increase, economic growth, and fish conversation: Collision course or savvy stewardship? Fisheries 2011, 36, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, S.C.; Braga, H.O.; de Santa-Maria, S.; Fonte, B.; Pereira, M.J.; García-Vinuesa, A.; Azeiteiro, U.M. An environmental education and communication project on migratory fishes and fishing communities. Educ. Sci. 2011, 11, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FARNET. Linking Fisheries to the Tourism Economy (FARNET Magazine No 9). European Commission. 2013. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/531ddc24-40be-49b2-bfa0-0c68edbb0e22 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Partalidou, M.; De Matteis, L. Sustainable Agritourism: An Opportunity for Agrifood Systems Transformation in the Mediterranean—Technical Brief; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024; Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/cd3578en (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Tsiolis, A. Thematic analysis of qualitative data. In Research Paths in Social Sciences: Theoretical and Methodological Contributions and Case Studies; Zaimakis, G., Ed.; University of Crete—Laboratory of Social Analysis and Applied Social Research: Heraklion, Greece, 2018; pp. 97–125. [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa, K.; Loftus, J.H. (Eds.) Introduction to Quality Control; 3A Corporation: Tokyo, Japan, 1990. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.