Abstract

In this study, we employ the PLS-SEM modelling approach to explore the socio-psychological drivers of horticulture, citrus, and table grapes Greek farmers to adopt biopesticides, beneficial insects, and/or functional biodiversity practices for pest control. Additionally, we investigate the barriers these farmers face-off when it comes to adoption. We found that overall “openness to innovation” and “general attitudes” have the most substantial, positive, and significant impact on farmers’ intentions for adoption. On the contrary, uncertainty, lack of financial support, and cost were identified as the three key main barriers. Importantly, our analysis emphasizes the need for tailored-made policies.

1. Introduction

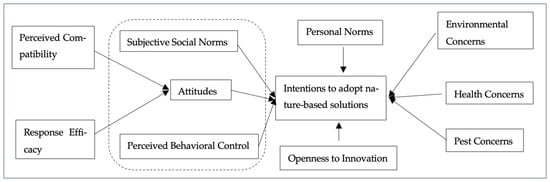

In this article, we study farmers’ intentions to adopt innovative pest management practices, namely biopesticides, beneficial insects, and functional biodiversity. To do so, we use an extended version of the TPB [1], where additional constructs to attitudes, subjective social norms, and perceived behavioral control are drawn from other theories, like the TAM [2] and the NAM [3]. The rationale is the following. First, the TPB is a well-established framework in the literature for exploring farmers’ behavior [4]. Second, research indicates that adding constructs can increase the predictability of the traditional TPB [5]. For instance, Rezaei et al. [6] integrate the TPB with the NAM to study the socio-psychological drivers on farmers’ intentions to IPM, while Xiang and Guo [7] employ an integrated model (Specifically, the integrated model includes the TPB, TAM, the innovation diffusion theory [8], and the concept of intrinsic motivation [9] that it is included in various motivation models.) to explore farmers’ intentions to use environmentally friendly techniques for pest and disease control.

Furthermore, this study targets Greek farmers that are specialized in the cultivation of horticultural products (e.g., tomato, pepper, cucumber), citrus (lemon, orange, tangerine) and table grapes. Additionally, farmers’ locations covered the Peloponnese regions (table grapes and citrus farmers) and Crete (horticulture farmers). The rationale of focusing on these agricultural products is that they have high economic value at the regional and national levels. Additionally, they usually require extensive use of pesticides and fungicides due to their high levels of vulnerability to pests and diseases.

Finally, our model was analyzed by employing the PLS-SEM modelling approach [10]. The rationale is that PLS-SEM is flexible because it does not rely on a particular data distribution, it can provide robust results even when the sample size is small, and it is recommended when extensions of traditional theories, like the TPB, are tested [11]. Furthermore, our results’ significance was tested using bootstrapping [10].

The key results can be summarized as follows. First, we found that attitudes, subjective social norms, perceived behavioral control, and openness to innovation have a positive and significant impact on farmers’ intentions to adopt innovative pest control practices. Second, both perceived compatibility and response efficacy positively but indirectly affect farmers’ intentions through attitudes. Finally, the most critical barriers for adoption were (general) uncertainty, costs, and lack of financial support.

2. Materials and Methods

In this study, data were collected using the snowball technique, and interviews were conducted both face-to-face and over the telephone. Additionally, farmers had the chance to complete the questionnaire themselves through an online platform.

Sociological and psychological constructs were measured using a 5-point Likert scale, where respondents indicated their level of agreement or disagreement with the corresponding statements. Additionally, farmers were asked to provide information on their demographic characteristics, farms and production characteristics, information channels and advisory sources, and financial characteristics.

Figure 1 depicts our theoretical framework, in which constructs inside the dotted box capture those specified in TPB, whereas those outside of it represent the additional ones.

Figure 1.

Structural representation of the theoretical framework.

The quality of the measurement model was assessed in terms of items’ (i.e., statements) reliability, model’s internal consistency, items’ convergent validity, and items’ discriminant validity [11]. Specifically, we used both Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability statistics to assess the model’s internal consistency, while for convergent validity, we used the average variance extracted coefficient (AVE). Finally, to test the item’s discriminant validity, we used the heterotrait-monotrait ratio [12].

The assessment of the structural model was performed in two steps. First, we tested for multicollinearity within the socio-psychological constructs by using the variance inflation factor (VIF) criterion. Second, the path coefficients’ significance was tested using bootstrapping with 10,000 iterations [10].

3. Results and Discussion

In this study, a sample of 235 farmers was acquired. Specifically, 76 farmers specialized in cultivating horticultural products, 84 in table grapes, and 75 in citrus. The results of our study were the following.

Overall, most of the farmers were over middle-aged, they had completed secondary education and were characterized by many years of agricultural experience. Additionally, they reported having attended agricultural training programs and being a member of an agricultural cooperative. Furthermore, most of them own up to 0.6 ha, and they rent a maximum of 0.1 ha. Moreover, the three-year average production ranged between 21 and 60 tons. Notably, most of them reported cultivating conventionally, whereas approximately 20% implement integrated pest management practices. Finally, the net agricultural income for most of the farmers was found to be low (ranging between 4000 and 15,000 euros).

Second, farmers reported knowing both biopesticides and beneficial insects, but a limited number of them mentioned that they know functional biodiversity practices (like cover crops). However, less than half of them pointed out that they currently use either biopesticides and/or beneficial insects for pest management.

Third, we found that attitudes, subjective social norms, perceived behavioral control, and openness to innovation have a positive and significant impact on farmers’ intentions to adopt innovative pest control practices. Additionally, both perceived compatibility and response efficacy positively but indirectly affect farmers’ intentions through attitudes. Finally, the most critical barriers for adoption were (general) uncertainty, costs and lack of financial support.

Fourth, farmers were found to use the Internet and social media as their main channels for information. Furthermore, they rely heavily on private agronomists for advice on both cultivation and pest management, whereas they rarely seek advice from certified agricultural extensionists.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that differences exist among farmers specialized in cultivating different agricultural products. For instance, subjective social norms and personal norms significantly affected intentions only in the case of table grapes farmers. On the contrary, openness to innovation significantly affected the intentions of both horticulture and citrus farmers to adopt innovative pest management, but its impact on table grapes farmers was insignificant. Moreover, lack of technical education and training was mentioned as an important barrier to adoption only in the case of table grape farmers.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we employed the PLS-SEM approach to explore the role of sociological and psychological constructs on farmers’ intentions to adopt innovative pest management practices.

The main conclusion is that sociological and psychological factors significantly affect farmers’ intentions at the aggregate level and per type of farming specialization. However, our sample size might be considered small for such an analysis, and thus, our result should be interpreted with some level of caution.

Most importantly, our analysis highlights the importance of technical training and education as a tool that can enhance farmers’ intentions in multiple ways. Given that behavioral differences exist among farmers, policymakers should design educational programs tailored to both farmers’ profiles (sociological, psychological, and demographic) and to the local characteristics where each farmer operates. Furthermore, policymakers should further disseminate the activities and the role of certified agricultural advisors, because their expertise on pest management practices and the needs and specialities that each farmer faces could increase the acceptability of such practices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.N.D. and I.T.; methodology, G.N.D. and I.T.; formal analysis, G.N.D. and I.T.; data curation, G.N.D.; writing—original draft preparation, G.N.D.; writing—review and editing, G.N.D. and I.T.; project administration, I.T.; funding acquisition, I.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the InnoPP-Kainotomos Fytoprostasia (Innovations in Plant Protection for sustainable and environmentally friendly pest control) research project with the support of the “EU-NextGenerationEU”, Greece 2.0 National Recovery and Resilience plan under the Grand Agreement No. TAEDR-0535675.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participants of this study and the agricultural cooperatives for their assistance in distributing the questionnaire to farmers. Additionally, we would like to thank Alexandra Sachini for her contribution to the data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of this study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PLS-SEM | Partial Least Square Structural Equation Modeling |

| TPB | Theory of Planned Behavior |

| NAM | Norm Activation Model |

| TAM | Technology Acceptance Model |

| IPM | Integrated Pest Management |

References

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative Influences on Altruism. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1977, 10, 221–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sok, J.; Borges, J.R.; Schmidt, P.; Ajzen, I. Farmer Behaviour as Reasoned Action: A Critical Review of Research with the Theory of Planned Behaviour. J. Agric. Econ. 2021, 72, 388–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, M.; Armitage, C.J. Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior: A Review and Avenues for Further Research. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 28, 1429–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, R.; Safa, L.; Damalas, C.A.; Ganjkhanloo, M.M. Drivers of farmers’ intention to use integrated pest management: Integrating theory of planned behavior and norm activation model. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 236, 328–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, P.; Guo, J. Understanding Farmers’ Intentions to Adopt Pest and Disease Green Control Techniques: Comparison and Integration Based on Multiple Models. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M.; Singhal, A.; Quinlan, M.M. Diffusion of innovations. In An Integrated Approach to Communication Theory and Research; Bryant, J., Oliver, M.B., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 432–448. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L. Effects of externally mediated rewards on intrinsic motivation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1971, 18, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 3rd ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.