Abstract

Agronomic systems that can guarantee consistent and sufficient crop yields must be developed and implemented in order to address the problems presented by climate change, especially the increase in average annual temperatures and the unequal distribution of precipitation. Over the course of five successive growing seasons (2019–2024), a Poly-Factorial field experiment was carried out at the Agricultural Research and Development Station (ARDS) Turda, Romania, which is situated in the hilly region of the Transylvanian Plain. The study investigated the combined effects of soil tillage system (conventional tillage—CS; no-tillage—NT) and fertilization strategies (N48P48K48 at sowing vs. N48P48K48 at sowing + N40.5CaO10.5MgO7 applied in early spring at the growth resumption) on the quantitative and qualitative performance of winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Results showed a modest yield difference of 206 kg ha−1 between the two tillage systems, favoring conventional tillage. However, the application of additional early-spring fertilization resulted in a significant average yield increase of 338 kg ha−1. Yield variability across the five years ranged from 262 to 1797 kg ha−1, highlighting the strong influence of climatic conditions on crop performance and emphasizing the need for adaptive management practices under changing environmental conditions.

1. Introduction

Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) is a very important crop worldwide [1,2,3], and is cultivated mainly for its grains. It is versatile [3], being used in bakery and pastry; the livestock industry; with straw as a raw material for the manufacture of paper; as a source of ethanol in biorefinery processes [4]; the preparation of organic fertilizers [5]; and cereal gluten is used in the pharmaceutical and cosmetic industries [6,7]. The wheat crop is fully mechanizable, and lends itself to no-till technology [8,9,10,11]; due to its high ecological plasticity, it can be grown in different climatic zones [12] and at higher altitudes [13,14,15]. The grains have a long shelf life and there is no risk of degradation of quality indices during long-distance transport [16]. Wheat is a very good precursor crop [17], and it is cultivated in over 100 countries, occupying an area of over 220 million hectares annually [18], and China and India are the largest wheat-growing nations in the world [19].

Compared to other straw cereals, wheat has a poorly developed root system and cannot efficiently capitalize on soil resources, thus it is necessary to provide nutrients in optimal and constant doses. Without fertilizer application, especially with nitrogen (N), the crop is more vulnerable to weather conditions [20]. In general, mineral fertilization is applied gradually, in different doses and periods: during sowing and in early spring, and later supplemented with foliar fertilizations that are applied in different phases of wheat vegetation. Increased wheat yield may result from higher nitrogen dosages combined with increased soil enzyme activity and the straw in return helps to improve soil fertility [21]. Foliar fertilizing (with micro and macro elements), stimulate the physiological processes of plants and indirectly increase wheat production [22,23,24]. Significant differences in yield, ear number, grain number, and 1000-grain weight were found between different fertilization management treatments [25]. Yield, number of spikes, number of grains, and quality indicators in wheat are higher when fertilization is applied than without fertilization treatments [26].

The quality of wheat grains is determined by the values of gluten, protein, thousand-kernel weight (TKW), and volume weight (HW); these indices are influenced by technological and climatic factors [27,28,29,30]. From a quantitative, qualitative, and economic perspective, very high yields can be achieved if particular attention is given to the selection of sowing strategies [31], tillage system [32], and the crop rotation [33,34]. Conservative tillage techniques have mostly replaced the traditional practice (with plow) in Romania’s winter wheat farming in recent years (min till, no-till), with farmers considering soil protection, in order to keep water in the soil especially during autumns, which are deficient in rainfall and can delay the emergence of wheat, but also for economic reasons [35,36,37,38]. According to some studies the cultivation of winter wheat in a conservative soil tillage system, in different pedoclimatic conditions, the yield achieved were comparable to those produced in the conventional [39,40]. Nitrogen fertilization and soil tillage must be correlated to achieve high and stable yields in wheat. Nitrogen application in optimal doses and phases combined with tillage adapted to local conditions (soil type, moisture, cultivation history) can significantly increase yield and yield quality [41]. Soil and climatic conditions in Romania vary widely from one agricultural area to another, with the Transylvanian Plain having specific pedoclimatic and relief particularities that require crops adapted to local conditions. Although it is an important agricultural production area of Romania, the Transylvanian Plain is characterized by a diverse and unstable climate, due to the fact that it behaves climatically as a plain, and orographically it presents a hilly relief [38].

In the context of contemporary agricultural practices and the principles of conservative agriculture, we initiated an experiment at the Agricultural Research and Development Station (ARDS) Turda, located in the heart of the Transylvanian Plain, to assess the adaptability and yield quality of the autumn wheat variety Andrada. The focus was to evaluate how this specific wheat variety responds when cultivated under a no-tillage system with moderate fertilization, adapted to the local environmental conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site

The research was carried out at the Agricultural Research and Development Station (ARDS) Turda (elevation 405 m, geographical coordinates 46°35′02″; 23°46′09″ E), located in Transylvanian Plain, Romania (Figure 1). Most of the arable land of the unit is located in hilly areas, with the soils being in different stages of erosion (Figure 2); therefore, unconventional soil tillage systems are important premises for the practice of sustainable agriculture.

Figure 1.

Agricultural Research and Development Station (ARDS) Turda location.

Figure 2.

ARDS Turda experimental fields.

2.2. Weather Conditions

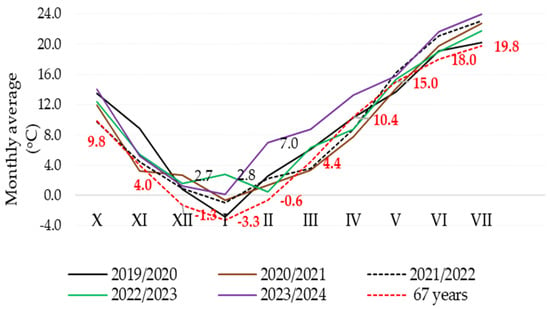

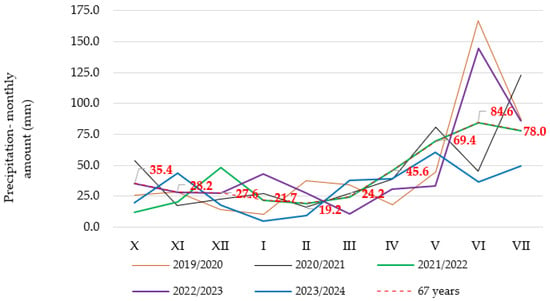

The weather conditions from five growing seasons at ARDS Turda are presented in Figure 3 and Figure 4 (Turda meteorological Station longitude: 23′47-latitude 46′35′-altitude 427 m) [42]. From the temperatures recorded between October 2019 and July 2024 in Turda, it can be seen that each year was warmer than the 67-year multiannual monthly average. It is worth noting the positive temperatures recorded in the winter months, especially the years 2020, 2022, and 2023 (Figure 3). The precipitation regime had quite large fluctuations (Figure 4) as demonstrated by the studies carried out by Haș et al. (2022) [43] and Șimon et al. (2023) [44]. In October—the winter wheat sowing period, the rainfall regime was reduced in most experimental years, except for 2020 and 2022. The highest precipitation values were obtained in the summer months, June 2019, 2022 and July 2020, 2021, 2022. In the Turda area, the specificity of the experimentation period is dependent on the unevenness of the precipitation distribution, and after longer periods of drought the rains that occurred later had a torrential character and were sometimes accompanied by hail and strong winds [45].

Figure 3.

The thermal regime for October 2019–July 2024, at ARDS Turda.

Figure 4.

The precipitation regime for October 2019–July 2024, at ARDS Turda.

2.3. Biological Materials

The biological material is represented by the Andrada winter wheat variety which has the following morphophysiological characteristics: plant size approx. 90 cm; loose spike with awn, red in color; red grain; good resistance to wintering and falling; the vegetation period from emergence to maturity is approximately 267 days [46,47].

2.4. Research Method

The type of soil on the experimental field is Phaeozem with a loamy-clay texture [48], a neutral pH 7.3 (measured potentiometrically in distilled water) characterized by good hydro-physical properties including 59% porosity at the surface and 47% at depth, a water retention capacity of 32%, and a withering coefficient of 18%. The soil’s agrochemical indices, total nitrogen 0.162%; phosphorus 9 ppm; and potassium 140 ppm and humus content of 3.01% (determined using the Walkley–Black method), good supply of N, P, K [49]. Agrochemical analyzes were conducted on soil samples collected from the arable layer (0–30 cm).

The research conducted at ARDS Turda in the five growing seasons (2019/2020; 2020/2021; 2021/2022; 2022/2023; 2023/2024) followed the influence of some technological factors (tillage and fertilization system) on the quantitative and qualitative yield of winter wheat. The Poly-Factorial experiment, type AxBxC-R:2x2x5-3, was placed according to the subdivided plots method with three replications. The experimental plots size is 48 m2 (4 m width × 12 m length).

The experimental factors:

S—Soil tillage system: S1, Conventional System (CS), plowed in autumn at a depth of 28 cm (Kuhn Huard Multi Master 125T plow) + the preparation of the seedbed (rotary harrow HRB 403 D) + sowing + basic fertilization (DIRECTA seeder) + crop maintenance, treatments (MET 1500) and harvested with WINTERSTEIGER plot combine (Wintesteiger AG, Ried im Innkreis, Austria); S2, No-till (NT), directly sowing + basic fertilization (DI-RECTA seeder) + crop maintenance, treatments (MET 1500) and harvested (WINTER-STEIGER combine for experimental plots).

F—Fertilization System: F1, basic fertilization with N48P48K48 kg ha−1 active substance concomitant with sowing; F2, basic fertilization with N48P48K48 kg ha−1 active substance concomitant with sowing + N40.5CaO10.5 MgO7 kg ha−1 active substance, early spring applied at the resumption of the wheat vegetation.

Y—Growing seasons: Y1, 2019/2020; Y2, 2020/2021; Y3, 2021/2022; Y4, 2022/2023; Y5, 2023/2024.

The sowing density was 550 germinating grains m−2, seeds were incorporated at a depth of 4 cm and 18 cm distance between rows. The seeds were treated before sowing with 0.5 L t−1 (150 g L−1 prothioconazole + 20 g L−1 tebuconazole) systemic fungicide [50]. Sowing was carried out in both systems in the second decade of October and harvesting the experiment in the last decade of July, in all experimental years. The precursor plant to winter wheat was soybean.

The control of monocotyledonous and dicotyledonous weeds present in the wheat crop was carried out with 265 g ha−1 herbicide based on 14.2 g kg−1 florasulam and 70.8 g kg−1 py-roxsulam. Pest control involved 0.2 L ha−1 insecticide based on 200 g L−1 acetamiprid + 1.2 L ha−1 growth regulator based on chlormequat-chloride 750 g/L [51]. Combating foliar and spike diseases by applying two fungicide treatments: T1 with 1.0 L ha−1 fungicide based on 100 g L−1 mefentrifluconazole + 100 g L−1 piraclostrobin when the wheat was in the bellows phase and T2 at the ear with 0.8 L ha−1 fungicide based on tebuconazole 50% + tri-floxystrobin 25% WG [52].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The gathered data were statistically analyzed using the standard analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Poly Fact Program Software 2020. The Poly Fact program facilitated the execution of Least Significant Difference (LSD) tests at significance levels of 5%, 1%, and 0.1%. The graphical representation of the results was carried out using Matrix-type charts in Past4, which display values based on color maps, where cool colors are associated with low values and warm colors with high values.

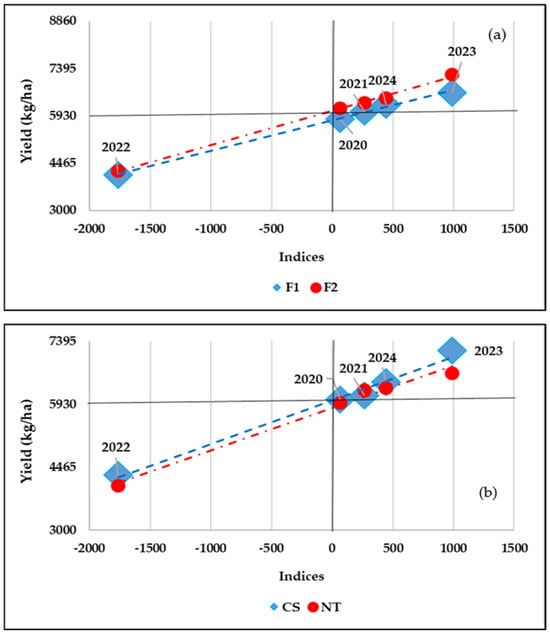

Additionally, yield stability was analyzed based on the soil tillage system and fertilization, using environmental indices calculated according to the method proposed by Eberhart and Russell (1966) [53]. The graphical representation in this case was performed using Microsoft Excel. By applying regression for each fertilization and tillage system variant of the Andrada winter wheat variety with respect to an environmental index the estimation of the desired stability parameters is achieved.

These parameters are described by the following model: Yij = μi + βiIj + δij, where

- Yij represents the mean yield of fertilization/tillage system variant i in environment j (where i = F1, F2/CS, NT and j = 2021, 2022, 2023, 2024, 2025, 2026).

- Ȳi is the mean of fertilization/tillage system variant i across all environments.

- βi is the regression coefficient expressing the response of variant i to environmental changes.

- δij is the deviation from regression of variant i in environment j.

- Ij is the environmental index, calculated as the difference between the mean of all variants in environment j and the overall mean of the experiment.

To analyze the relationships between yield, the thousand-kernel weight (TKW) and volume weight (HW), as well as their correlation with total precipitation during the winter wheat-growing season and the minimum temperature recorded during the vernalization period (December–February) and the maximum temperature in the post-anthesis period (May–June), the Pearson correlation coefficient matrix was generated using Past4.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Influence of Experimental Factors on Winter Wheat Yield

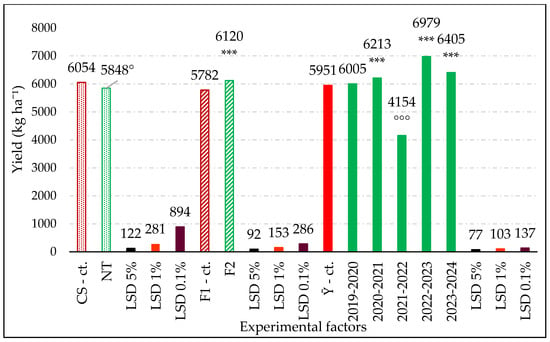

By analyzing the values in Figure 5, it shows that in the two experimental tillage systems, the achievement of grain yield was significantly influenced (negatively) by the NT system (5848 kg ha−1), compared to the control (CS with 6054 kg ha−1), with the difference of 206 kg ha−1 being in favor of the plowing system. Similar results were obtained by Wozniak et al. (2020) [54], with a reduction in yield of 4.3–23.4% in the NT soil system, while Biberdzic et al. (2020) [55] obtained an increased production (12.43–29.51%) compared to RT when CT was experimented, depending on climatic conditions.

Figure 5.

Influence of experimental factors (system, fertilization, year) on winter wheat yield. ***: significant at 0.001; °°°: significant at 0.001; °: significant at 0.05 (negative).

The doses of fertilizing are very important for crop development and implicitly in the realization of the harvests. In our study, the increase in the fertilizer dose has a very significant positive influence on the average wheat yield (F1—5782 kg ha−1, F2—6120 kg ha−1), the difference of 338 kg ha−1 being in favor of the variant with additional fertilization (F2).

During the five growing seasons, there are very large differences in yield that have been recorded, such that the most substantial yield reduction occurred in the 2021–2022 growing season (4154 kg/ha−1), the differences being 1797 kg ha−1 compared to the control variant (5951 kg ha−1 yield average for five season). More favorable conditions were met in the 2020–2021, 2022–2023 and 2023–2024 seasons when the yield obtained were between 6213 kg ha−1 and 6979 kg ha−1, and the differences between 262 and 1028 kg ha−1 present statistical assurance as being very significantly positive.

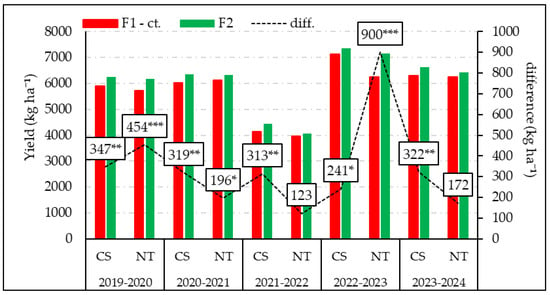

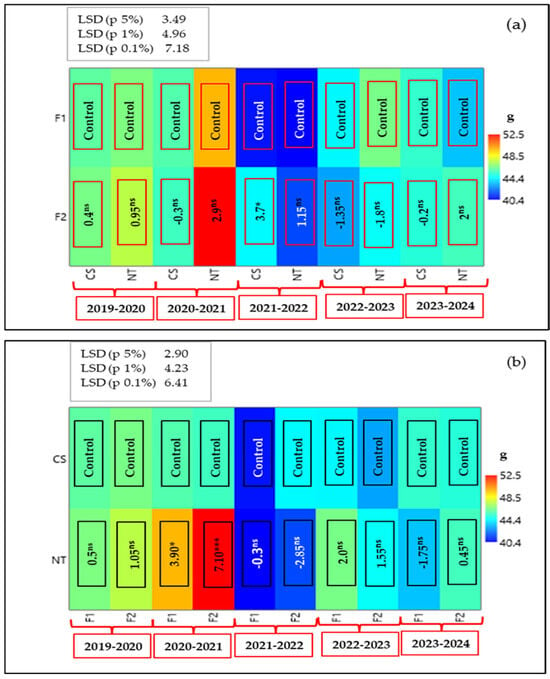

3.2. Influence of the Triple Interaction, Fertilization (F) × Year (Y) × Soil Tillage System (S), on Winter Wheat Yield

The triple interaction among fertilization (F) × year (Y) × soil tillage system (S) highlights the significant contribution of fertilization to yield formation, independent of the tillage practice (Figure 6), the same idea being proposed by Ahmadi et al. (2024) [56], Halvorson et al. (2000) [57]. In each year, statistically significant yield increases of up to 900 kg/ha (NT, 2022–2023) were observed compared to the first fertilization variant. The most substantial yield reduction was noted in the 2021–2022 growing season. Regarding the effect of the experimental factors interaction on the grain yield of the Andrada winter wheat variety, results indicate that the NT system generally produced lower yields than conventional tillage, contrary to the results obtained by some authors such as DeVita et al. (2007) [58], Mancinelli et al. (2023) [59], Li et al. (2020) [60], Yuan et al. (2022) [61], especially in years with low rainfall, but similar to those obtained by Seepamore et al. (2020) [62], López-Bellido et al. (2000) [63], Nunes et al. (2018) [64].

Figure 6.

Influence of the triple interaction, fertilization (F) × year (Y) × soil tillage system (S), on winter wheat yield. ***: significant at 0.001; **: significant at 0.01; *: significant at 0.05.

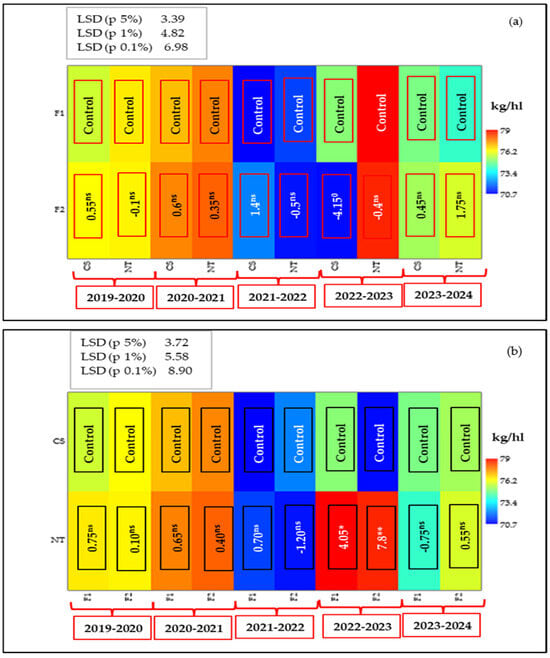

The thousand-kernel weight (TKW) is a parameter influenced by several factors, such as genotype [65], applied technology and environmental conditions during the growing season, such the data obtained in this study are in line with other studies. The variation in the thousand-kernel weight (TKW) was also influenced by the two technological factors and the experimental year, with higher values recorded under supplementary fertilization and, in general, an increasing trend for this parameter in the no-tillage system (Figure 7). Over the five-year study period, across two soil tillage systems and two fertilization levels, the TKW of the Andrada winter wheat variety ranged from 40.4 g (Y3xF1xNT) to 52.5 g (Y2xF2xNT). The application of supplementary fertilization resulted in a statistically significant increase in TKW during the 2021–2022 growing season, particularly under the conventional tillage system with plowing. In the second experimental year, the no-tillage system led to an increase in TKW by 7.10 g compared to the conventional tillage system.

Figure 7.

TKW differences in the Andrada winter wheat variety based on LSD tests at significance levels of 5%, 1%, and 0.1%. depending on the triple interaction of fertilization (F) × year (Y) × soil tillage system (S)—(a), and on the triple interaction of soil tillage system (S) × year (Y) × fertilization (F)—(b); ***: significant at 0.001; *: significant at 0.05; ns: not significant.

The volume weight (HW) ranged from 70.7 kg/hL to 79.0 kg/hL, with the lowest value recorded during the 2021–2022 growing season under the basic fertilization treatment and the conventional tillage system, with plowing (Figure 8). This parameter exhibited greater variability in response to the soil tillage system than to the fertilization regime; however, higher values were generally associated with supplementary fertilization. In terms of variation across tillage systems, an increase of 4.05 kg/hL and 7.8 kg/hL was observed in the 2022–2023 growing season under NT compared to the CS.

Figure 8.

Volume weight (HW) differences in the Andrada winter wheat variety based on LSD tests at significance levels of 5%, 1%, and 0.1%, depending on the triple interaction of fertilization (F) × year (Y) × soil tillage system (S)—(a), and on the triple interaction of soil tillage system (S) × year (Y) × fertilization (F)—(b); **: significant at 0.01; *, 0: significant at 0.05 (positive and negative); ns: not significant.

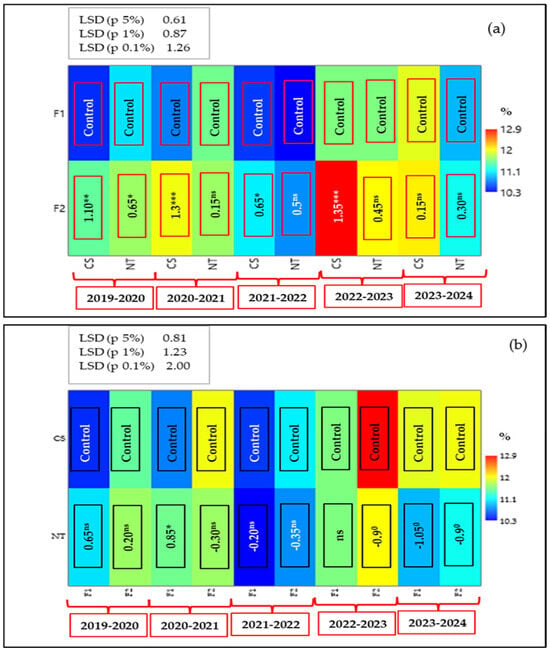

The protein content exhibited considerable variation over the five-year study period, across two soil tillage systems and two fertilization treatments (Figure 9). In the Andrada wheat variety, a protein content of 10.3% was recorded in the first experimental year under the conventional tillage system with baseline fertilization. Studies by Woźniak et al. (2017) [66] have shown that gluten and protein are influenced more by environmental conditions than by fertilization or tillage, and authors such as Leonte et al. (2024) [67] state that protein and gluten vary depending on how the soil is tilled. As anticipated, the effect of fertilization on protein accumulation in the grain is evident, with higher protein content observed under supplementary fertilization compared to the baseline treatment. The most notable increase occurred in the fourth experimental year, where under the conventional tillage system, the protein content was 1.35% higher with supplementary fertilization compared to basic fertilization. In terms of soil tillage systems, higher protein content was generally observed under the conventional tillage system with plowing. In contrast, the no-tillage (NT) system resulted in a reduction of up to 1.05% in grain protein content compared to the conventional tillage system, similar results being obtained by Buczek et al. (2021) [68], Yousefian et al. (2021) [69]. Studies such as those conducted by Woźniak and Gos (2014) [70] have shown that the tillage system did not influence the protein and gluten content of the grains.

Figure 9.

Protein content differences in the Andrada winter wheat variety based on LSD tests at significance levels of 5%, 1%, and 0.1%, depending on the triple interaction of fertilization (F) × year (Y) × soil tillage system (S)—(a), and on the triple interaction of soil tillage system (S) × year (Y) × fertilization (F)—(b) ***: significant at 0.001; **: significant at 0.01; *, 0: significant at 0.05 (positive and negative); ns: not significant.

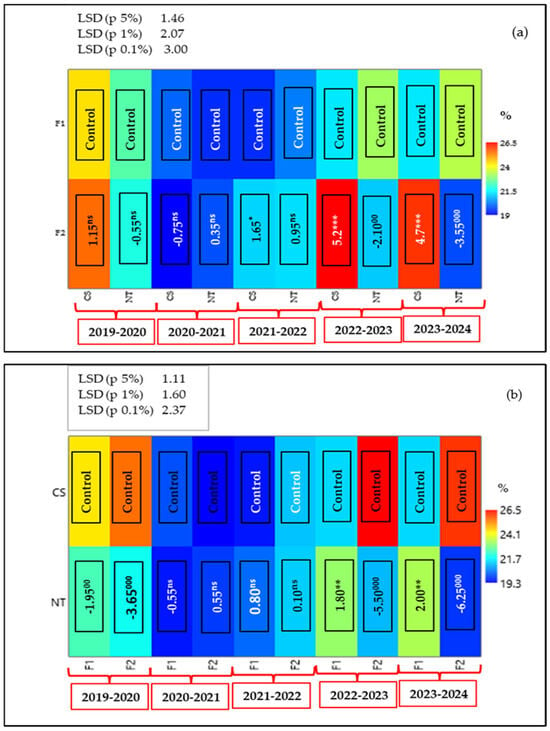

The gluten content also varied, ranging from 19% to 26.5%, with higher values observed following supplementary fertilization, where the greatest difference of 5.2% was recorded compared to basic fertilization in the 2022–2023 growing season. In general, better quality was observed under the no-tillage (NT) system compared to the conventional tillage (CS) system, in contradiction with the results obtained by Colecchia et al. (2015) [71]. Notably, in the final experimental year, NT showed both a 2% increase compared to CS under basic fertilization and a 6.25% decrease under supplementary fertilization (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Gluten differences in the Andrada winter wheat variety based on LSD tests at significance levels of 5%, 1%, and 0.1%, depending on the triple interaction of fertilization (F) × year (Y) × soil tillage system (S)—(a) and on the triple interaction of soil tillage system (S) × year (Y) × fertilization (F)—(b); ***, 000: significant at 0.001 (positive and negative); **, 00: significant at 0.01 (positive and negative); *: significant at 0.05 (positive); ns: not significant.

The analysis of yield stability across the two soil tillage systems and two fertilization treatments revealed a more pronounced stability under the conventional tillage system and with the application of supplementary fertilization (Figure 11), similar results were obtained by Obour et al. (2024) [72]. However, the regression lines for the tillage systems were nearly parallel and relatively close, indicating that under the pedoclimatic conditions of the experimental field, favorable wheat yields were also achieved with the no-tillage (NT) system. Results presented by authors such as Aula et al. (2023) [73] indicated that tillage practices had an equal effect on yield stability across a diverse range of climatic conditions. Among the five experimental years, the 2021–2022 growing season stood out, with a significant reduction in wheat yield due to unfavorable climatic conditions. Regarding yield stability across the two fertilization levels, similar yields were observed under both fertilization treatments under unfavorable conditions, while under favorable environmental conditions, supplementary fertilization resulted in significantly higher yield increases compared to baseline fertilization. The data presented by Majrashi et al. (2019) [74] showed that as the application rate of N increased, the slope also increased.

Figure 11.

The yield stability of the Andrada wheat variety over the five experimental years based on fertilization—(a) and soil tillage system—(b).

The analysis of correlation coefficients (Table 1) between yield, TKW, HW, and meteorological factors (precipitation, minimum and maximum temperatures) indicates the significant role of water availability in crop development, with a strong correlation between yield and precipitation (r = 0.92), this is also confirmed by the results obtained by Vrindts et al. (2005) [75], who state that wheat yields decrease in areas with greater moisture variability and by those presented by Fang et al. (2023) [76] who show a large fluctuation in rainfall in the important phases of the wheat vegetation period. Studies by Varadi et al. (2020) [77] have shown that the Andrada variety has a high production rate per unit of rainfall. A positive correlation was also observed between precipitation and TKW, as well as between precipitation and HW. In contrast, a strong negative correlation was found between yield and maximum temperatures recorded during the post-anthesis period (r = −0.52), emphasizing the effect of drought conditions from May and June on wheat yield. Additionally, a positive and moderate correlation was identified between yield and volume weight (r = 0.56), and a direct positive relationship between yield and TKW (r = 0.47).

Table 1.

Pearson correlation coefficients between yield, TKW, HW, and climatic factors (precipitation, minimum and maximum temperatures); ***: significant at 0.001 (positive); **, 00: significant at 0.01 (positive and negative); *, 0: significant at 0.05 (positive and negative).

4. Conclusions

The results highlight the major importance of fertilization in determining wheat yield, regardless of the tillage system used. In the 2022–2023 growing season, significant yield increases of up to 895 kg/ha were recorded in the no-tillage (NT) system, highlighting the positive impact of fertilization on crop productivity.

The triple interaction between fertilization, year and tillage system revealed that the conventional tillage system generally generated higher wheat yields compared to the no-tillage (NT) system. This result suggests that, under the specific conditions of the experiment, conventional tillage technology favored better wheat crop development, possibly due to a more efficient mobilization of soil nutrients and a more favorable structure for plant roots.

TKW values showed a significant increase following the application of additional fertilization, and the no-till system generally showed an increasing trend. During the study period, TKW fluctuated between 40.4 g and 52.5 g, with the highest increase being recorded following additional fertilization, especially under the conventional tillage system.

HW values ranged from 70.7 kg/hL to 79.0 kg/hL, with the lowest values recorded in the 2021–2022 growing season under basic fertilization and conventional tillage. A greater variation was observed by tillage system, with the NT system having higher HW values in the 2022–2023 season compared to the conventional tillage system.

The protein content showed considerable fluctuations during the experimental years, with the highest values being obtained after additional fertilization. The conventional tillage system consistently generated a higher protein content, with a significant increase of 1.35% in the case of additional fertilization in the fourth experimental year. In contrast, the NT system showed a decrease of up to 1.05% in protein content.

Gluten content ranged from 19% to 26.5%, with higher values following supplementary fertilization. The largest difference, 5.2%, was observed in the 2022–2023 growing season, when supplementary fertilization was compared to basal fertilization. The NT system generally showed superior quality, with a 2% increase in gluten content compared to the conventional basal fertilization system, but with supplementary fertilization there was a 6.25% decrease in the last experimental year.

Regarding stability, significant stability was observed when additional fertilization was applied, as well as under the conditions of a classic tillage system. These conditions favored a more uniform development of the crop, contributing to a better adaptability of the plant to environmental variability and a constant performance throughout the growing season. Additional fertilization, combined with the traditional method of tillage, led to a more stable maintenance of quality and yield parameters, indicating that these practices can ensure a more resilient agricultural production and less affected by climatic fluctuations or other external factors.

The crucial importance of water availability for crop development was highlighted by the strong correlation observed between yield and rainfall (r = 0.92). There was also a positive correlation between rainfall and two key wheat quality parameters: thousand grain weight (TKW) and volume weight (HW). These results highlight the decisive role of water in influencing both the quantity and quality of the harvest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.C.; methodology, F.C. and C.U.; software, C.U. and M.B.; formal analysis, A.Ș. and R.E.C.; investigation, F.C., A.P. and D.H.; resources, C.C. and M.B.; data curation, O.A.C., P.I.M. and R.R.; writing—original draft preparation, F.C. and A.P.; writing—review and editing, C.U., R.E.C. and D.H.; visualization, C.C., P.I.M. and A.P.; supervision, T.R., C.U. and A.Ș.; project administration, F.C.; funding acquisition, T.R. and P.I.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, Project ADER no. 123/17.07/2023: Conservation of soil resources was achieved through the use of technological components of regenerative agriculture in order to obtain economic and sustainable harvests of straw cereals in the Transylvanian Plateau.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Billen, G.; Lassaletta, L.; Garnier, J. A Biogeochemical View of the Global Agro-Food System: Nitrogen Flows Associated with Protein Production, Consumption and Trade. Glob. Food Secur. 2014, 3, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Meghwal, M.; Prabhakar, P.K. Bioactive Compounds of Pigmented Wheat (Triticum aestivum): Potential Benefits in Human Health. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 110, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebouh, N.Y.; Khugaev, C.V.; Utkina, A.O.; Isaev, K.V.; Mohamed, E.S.; Kucher, D.E. Contribution of Eco-Friendly Agricultural Practices in Improving and Stabilizing Wheat Crop Yield: A Review. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.; Suopajärvi, T.; Mankinen, O.; Mikola, M.; Mikkelson, A.; Ahola, J.; Hiltunen, S.; Komulainen, S.; Kantola, A.M.; Telkki, V.-V.; et al. Comparison of Lignin Fractions Isolated from Wheat Straw Using Alkaline and Acidic Deep Eutectic Solvents. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 15074–15084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velichkova, R.; Pushkarov, M.; Angelova, R.A.; Sandov, O.; Markov, D.; Simova, I.; Stankov, P. Exploring the Potential of Straw Biochar for Environmentally Friendly Fertilizers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimouni, B.; Raymond, J.; Merle-Desnoyers, A.M.; Azanza, J.L.; Ducastaing, A. Combined Acid Deamidation and Enzymic Hydrolysis for Improvement of the Functional Properties of Wheat Gluten. J. Cereal Sci. 1994, 20, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shan, Q.; Wang, C.; Feng, S.; Li, Y. Research Progress and Application Analysis of the Returning Straw Decomposition Process Based on CiteSpace. Water 2023, 15, 3426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, X. The Influence of Agricultural Production Mechanization on Grain Production Capacity and Efficiency. Processes 2023, 11, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chețan, F.; Chețan, C.; Rusu, T.; Moraru, P.I.; Ignea, M.; Șimon, A. Influence of Fertilization and Soil Tillage System on Water Conservation in Soil, Production and Economic Efficiency in the Winter Wheat Crop. Sci. Papers. Ser. A Agron. 2017, 60, 42–48. [Google Scholar]

- Castellini, M.; Fornaro, F.; Garofalo, P.; Giglio, L.; Rinaldi, M.; Ventrella, D.; Vitti, C.; Vonella, A.V. Effects of No-Tillage and Conventional Tillage on Physical and Hydraulic Properties of Fine Textured Soils under Winter Wheat. Water 2019, 11, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, L.; Song, J.; Wang, D.; Xue, J.; Wang, Y.; Gao, Z. Wheat Nitrogen Use and Grain Protein Characteristics Under No-Tillage: A Greater Response to Drip Fertigation Compared to Intensive Tillage. Agronomy 2025, 15, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telfer, P.; Edwards, J.; Taylor, J.; Able, J.A.; Kuchel, H. A Multi-Environment Framework to Evaluate the Adaptation of Wheat (Triticum aestivum) to Heat Stress. Theor Appl Genet 2022, 135, 1191–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppel, R.; Ingver, A.; Ardel, P.; Kangor, T.; Kennedy, H.J.; Koppel, M. The Variability of Yield and Baking Quality of Wheat and Suitability for Export from Nordic–Baltic Conditions. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. B—Soil Plant Sci. 2020, 70, 628–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.A.A.; Wu, H.; Farid, M.F.; Tareen, W.-U.-H.; Badar, I.H. Climate Trends and Wheat Yield in Punjab, Pakistan: Assessing the Change and Impact. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Shahid, M.A.; Zaman, M.; Miao, Y.; Huang, Y.; Safdar, M.; Maqbool, S.; Muhammad, N.E. Improving Wheat Yield Prediction with Multi-Source Remote Sensing Data and Machine Learning in Arid Regions. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, B.C. Wheat in the World. In Bread Wheat Improvement and Production; Plant Production and Protection Series; Curtis, B.C., Rajaram, S., Macpherson, H.G., Eds.; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2002; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Shahzad, M.; Hussain, M.; Jabran, K.; Farooq, M.; Farooq, S.; Gašparovič, K.; Barboricova, M.; Aljuaid, B.S.; El-Shehawi, A.M.; Zuan, A.T.K. The Impact of Different Crop Rotations by Weed Management Strategies’ Interactions on Weed Infestation and Productivity of Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Agronomy 2021, 11, 2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragomir, A. scris de N. GRÂUL—Triticum aestivum L.—Revista Ferma. Available online: https://revista-ferma.ro/graul-triticum-aestivum-l/ (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Top 10 Cei Mai Mari Producători de Grâu Din Lume. Available online: https://agrointel.ro/243777/top-10-cei-mai-mari-producatori-de-grau-din-lume (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Chen, H.; Deng, A.; Zhang, W.; Li, W.; Qiao, Y.; Yang, T.; Zheng, C.; Cao, C.; Chen, F. Long-Term Inorganic plus Organic Fertilization Increases Yield and Yield Stability of Winter Wheat. Crop J. 2018, 6, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Luo, Y.; Li, C.; Chang, Y.; Jin, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z. Improving Soil Fertility and Wheat Yield by Tillage and Nitrogen Management in Winter Wheat–Summer Maize Cropping System. Agronomy 2023, 13, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bărdaş, M.; Rusu, T.; Popa, A.; Russu, F.; Șimon, A.; Chețan, F.; Racz, I.; Popescu, S.; Topan, C. Effect of Foliar Fertilization on the Physiological Parameters, Yield and Quality Indices of the Winter Wheat. Agronomy 2023, 14, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saquee, F.S.; Diakite, S.; Kavhiza, N.J.; Pakina, E.; Zargar, M. The Efficacy of Micronutrient Fertilizers on the Yield Formulation and Quality of Wheat Grains. Agronomy 2023, 13, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobolewska, M.; Wenda-Piesik, A.; Jaroszewska, A.; Stankowski, S. Effect of Habitat and Foliar Fertilization with K, Zn and Mn on Winter Wheat Grain and Baking Qualities. Agronomy 2020, 10, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Li, J.; An, Z.; Liang, J.; Tian, X.; Chen, Y.; Sun, Y.; Li, Y. Optimal Fertilization Strategies for Winter Wheat Based on Yield Increase and Nitrogen Reduction on the North China Plain. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roa, G.A.; Quintana-Obregón, E.A.; González-Renteria, M.; Ruiz Diaz, D.A. Increasing Wheat Protein and Yield through Sulfur Fertilization and Its Relationship with Nitrogen. Nitrogen 2024, 5, 553–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jańczak-Pieniążek, M.; Buczek, J.; Kaszuba, J.; Szpunar-Krok, E.; Bobrecka-Jamro, D.; Jaworska, G. A Comparative Assessment of the Baking Quality of Hybrid and Population Wheat Cultivars. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chețan, F.; Hirișcău, D.; Rusu, T.; Bărdaș, M.; Chețan, C.; Șimon, A.; Moraru, P.I. Yield, Protein Content and Water-Related Physiologies of Spring Wheat Affected by Fertilizer System and Weather Conditions. Agronomy 2024, 14, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitura, K.; Cacak-Pietrzak, G.; Feledyn-Szewczyk, B.; Szablewski, T.; Studnicki, M. Yield and Grain Quality of Common Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Depending on the Different Farming Systems (Organic vs. Integrated vs. Conventional). Plants 2023, 12, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, H.; Yan, Z.; Sun, P.; Zhang, L.; Ding, P.; Li, L.; Ren, A.; Sun, M.; Gao, Z. Effects of Nitrogen on Photosynthetic Productivity and Yield Quality of Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Agronomy 2023, 13, 1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachutta, K.; Jankowski, K.J. The Quality of Winter Wheat Grain by Different Sowing Strategies and Nitrogen Fertilizer Rates: A Case Study in Northeastern Poland. Agriculture 2024, 14, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruisi, P.; Giambalvo, D.; Saia, S.; Di Miceli, G.; Frenda, A.S.; Plaia, A.; Amato, G. Conservation Tillage in a Semiarid Mediterranean Environment: Results of 20 Years of Research. Ital. J. Agron. 2014, 9, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darguza, M.; Gaile, Z. The Productivity of Crop Rotation Depending on the Included Plants and Soil Tillage. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawęda, D.; Haliniarz, M. Grain Yield and Quality of Winter Wheat Depending on Previous Crop and Tillage System. Agriculture 2021, 11, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cociu, A. Long-Term Tillage and Crop Sequence Effects on Winter Wheat and Triticale Grain Yield under Eastern Romanian Danube Plain Climate Conditions. Rom. Agric. Res. 2019, 36, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manole, D.; Giumba, A.M.; Popescu, A. Technology Adaptation and Economic Eficiency for Winter Wheat Crop in the Conditions of Climate Changes—South-East Romania, Dobrogea Area. Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2023, 23, 487–514. [Google Scholar]

- Cizmaș, G.; Cociu, A.; Mandea, V.; Marinciu, C.M.; Șerban, G.; Săulescu, N.N. Wheat Cultivar Performance under No-till and Traditional Agriculture. Rom. Agric. Res. 2022, 39, 457–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, T.; Moraru, P.I. Impact of Climate Change on Crop Land and Technological Recommendations for the Main Crops in Transylvanian Plain, Romania. Rom. Agric. Res. 2015, 32, 103–111. [Google Scholar]

- Chirita, S.; Rusu, T.; Urda, C.; Chetan, F.; Racz, I. Winter Wheat Yield and Quality Depending on Chemical Fertilization, Different Treatments and Tillage Systems. AgroLife Sci. J. 2023, 12, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Yang, S.; Li, S.; Fan, P.; Wu, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhai, C. Effects of No-Tillage on Field Microclimate and Yield of Winter Wheat. Agronomy 2024, 14, 3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Ma, G.; Wang, C.; Lu, H.; Li, S.; Xie, Y.; Ma, D.; Zhu, Y.; Guo, T. Effect of Irrigation and Nitrogen Application on Grain Amino Acid Composition and Protein Quality in Winter Wheat. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turda Weather Station, Northern Transylvania Regional Meteorological Center Cluj. Available online: https://www.meteoromania.ro/ (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Haş, V.; Tritean, N.; Copândean, A.; Vana, C.; Varga, A.; Călugar, R.; Ceclan, L.; Simon, A. The Impact of Climate Change and Genetic Progress on Performance of Old and Recent Released Maize Hybrids Created at the ARDS Turda. Rom. Agric. Res. 2022, 39, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Șimon, A.; Moraru, P.I.; Ceclan, A.; Russu, F.; Chețan, F.; Bărdaș, M.; Popa, A.; Rusu, T.; Pop, A.I.; Bogdan, I. The Impact of Climatic Factors on the Development Stages of Maize Crop in the Transylvanian Plain. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chețan, F.; Chețan, C.; Simon, A.; Bărdaș, M.; Ceclan, A.; Tărău, A.; Crișan, I.; Gaga, I. The Influence of the Soil Tillage System on Soil Water Conservation and Production, on the Autumn Wheat Culture. In The Pedoclimatic Conditions Specific to the Hill Area of the Transylvanian Plain; UIAC IASI: Bacău, Romania, 2023; pp. 31–47. [Google Scholar]

- Moldovan, V.; Kadar, R.; Popescu, C. The Winter Wheat Variety “Andrada”. Analele Institutului Național Cercet.-Dezvoltare Agric. Fundulea 2012, 80, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- State Institute for Variety Testing and Registration (ISTIS) Bucharest. Available online: https://istis.ro/ (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- SRTS Romanian System of Soil Taxonomy 2012. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/374689589/Sistemul-Roman-de-Taxonomie-a-Solurilor-2012-SRTS (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Pedological and Soil Chemistry Office Cluj. Available online: https://ospacluj.ro/ (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Redigo® Pro 170 FS | Bayer. Available online: https://www.cropscience.bayer.ro/cpd/tratament-samanta-bcs-redigo-pro-170-fs-ro-ro (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Plant Growth Regulator/3C Chlormequat 750. Available online: https://www.agricentre.basf.co.uk/en/Products/Product-Search/Plant-Growth-Regulator/3C-Chlormequat-750.html (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Fungicide/Revycare®—Fungicid Pentru Combaterea Bolilor. Available online: https://www.agro.basf.ro/ro/produse/overview/Fungicide/Revycare.html (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Eberhart, S.A.; Russell, W.A. Stability Parameters for Comparing Varieties 1. Crop Sci. 1966, 6, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woźniak, A. Effect of Cereal Monoculture and Tillage Systems on Grain Yield and Weed Infestation of Winter Durum Wheat. Int. J. Plant Prod. 2020, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biberdzic, M.; Barac, S.; Djikic, A.; Prodanovic, D.; Rajicic, V. Influence of Soil Tillage System on Soil Compaction and Winter Wheat Yield. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2020, 80, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, H.; Mirseyed Hosseini, H.; Moshiri, F.; Alikhani, H.A.; Etesami, H. Impact of Varied Tillage Practices and Phosphorus Fertilization Regimes on Wheat Yield and Grain Quality Parameters in a Five-Year Corn-Wheat Rotation System. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 14717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halvorson, A.D.; Black, A.L.; Krupinsky, J.M.; Merrill, S.D.; Wienhold, B.J.; Tanaka, D.L. Spring Wheat Response to Tillage and Nitrogen Fertilization in Rotation with Sunflower and Winter Wheat. Agron. J. 2000, 92, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devita, P.; Dipaolo, E.; Fecondo, G.; Difonzo, N.; Pisante, M. No-Tillage and Conventional Tillage Effects on Durum Wheat Yield, Grain Quality and Soil Moisture Content in Southern Italy. Soil Tillage Res. 2007, 92, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancinelli, R.; Allam, M.; Petroselli, V.; Atait, M.; Jasarevic, M.; Catalani, A.; Marinari, S.; Radicetti, E.; Jamal, A.; Abideen, Z.; et al. Durum Wheat Production as Affected by Soil Tillage and Fertilization Management in a Mediterranean Environment. Agriculture 2023, 13, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Z.; Li, J.; Tian, C.; Hua, D.; Shi, C.; Wang, H.; Han, J.; Xu, Y. Effects of Conservation Tillage on Soil Physicochemical Properties and Crop Yield in an Arid Loess Plateau, China. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Sadiq, M.; Rahim, N.; Li, G.; Yan, L.; Wu, J.; Xu, G. Tillage Strategy and Nitrogen Fertilization Methods Influences on Selected Soil Quality Indicators and Spring Wheat Yield under Semi-Arid Environmental Conditions of the Loess Plateau, China. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seepamore, M.; Du Preez, C.; Ceronio, G. Impact of Long-Term Production Management Practices on Wheat Grain Yield and Quality Components under a Semi-Arid Climate. S. Afr. J. Plant Soil 2020, 37, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Bellido, L.; López-Bellido, R.J.; Castillo, J.E.; López-Bellido, F.J. Effects of Tillage, Crop Rotation, and Nitrogen Fertilization on Wheat under Rainfed Mediterranean Conditions. Agron. J. 2000, 92, 1054–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, M.R.; Van Es, H.M.; Schindelbeck, R.; Ristow, A.J.; Ryan, M. No-till and Cropping System Diversification Improve Soil Health and Crop Yield. Geoderma 2018, 328, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mureșan, D.; Varadi, A.; Racz, I.; Kadar, R.; Ceclan, A.; Duda, M.M. Effect of Genotype and Sowing Date on Yield and Yield Components of Facultative Wheat in Transylvania Plain. AgroLife Sci. J. 2020, 9, 237–247. [Google Scholar]

- Woźniak, A.; Woźniak, A.; Stępniowska, A. Yield and Quality of Durum Wheat Grain in Different Tillage Systems. J. Elem. 2017, 22, 817–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonte, A.; Isticioaia, S.F.; Pintilie, P.; Druțu, A.C.; Enea, A.; Eșanu, S. Research on the Influence of Different Doses of Nitrogen and Phosphorus on Yield and Quality Indices on Corn Seeds, under Pedoclimatic Conditions at A.R.D.S. Secuieni. Sci. Pap. Ser. A Agron. 2023, 66, 310–315. [Google Scholar]

- Buczek, J.; Migut, D.; Jańczak-Pieniążek, M. Effect of Soil Tillage Practice on Photosynthesis, Grain Yield and Quality of Hybrid Winter Wheat. Agriculture 2021, 11, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefian, M.; Shahbazi, F.; Hamidian, K. Crop Yield and Physicochemical Properties of Wheat Grains as Affected by Tillage Systems. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woźniak, A.; Gos, M. Yield and Quality of Spring Wheat and Soil Properties as Affected by Tillage System. Plant Soil Environ. 2014, 60, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colecchia, S.A.; De Vita, P.; Rinaldi, M. Effects of Tillage Systems in Durum Wheat under Rainfed Mediterranean Conditions. Cereal Res. Commun. 2015, 43, 704–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obour, A.K.; Holman, J.D.; Prasad, P.V.V.; Assefa, Y. Winter Wheat Yield Stability as Affected by fertilizer-N, Tillage, and Yield Environment. Agron. J. 2024, 116, 2523–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aula, L.; Mikha, M.M.; Easterly, A.C.; Creech, C.F. Winter Wheat Grain Yield Stability under Different Tillage Practices. Agron. J. 2023, 115, 1006–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majrashi, M.; Obour, A.K.; Moorberg, C.J. Crop Yield and Yield Stability as Affected by Long-Term Tillage and Nitrogen Fertilizer Rates in Dryland Wheat and Sorghum Production Systems. Kans. Agric. Exp. Stn. Res. Rep. 2019, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrindts, E.; Mouazen, A.M.; Reyniers, M.; Maertens, K.; Maleki, M.R.; Ramon, H.; De Baerdemaeker, J. Management Zones Based on Correlation between Soil Compaction, Yield and Crop Data. Biosyst. Eng. 2005, 92, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, D.; Huang, J.; Sun, W.; Ullah, N.; Jin, S.; Song, Y. Characteristics of Historical Precipitation for Winter Wheat Cropping in the Semi-Arid and Semi-Humid Area. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1049824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadi, A.; Hirişcău, D.; Duda, M.M.; Kadar, R.; Russu, F.M.; Porumb, I.; Racz, I.; Ceclan, A. The Behavior of Four Winter Wheat Genotypes under Different Rates of Nitrogen Fertilizer. AgroLife Sci. J. 2020, 9, 334–341. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.