Abstract

Pasture-based ruminant systems link nitrogen (N) nutrition with ecosystem N cycling. Grazing ruminants convert fibrous forages into milk and meat but excrete 65 to 80% of ingested N, creating excreta hotspots that drive ammonia volatilization, nitrate leaching, and nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions. This review synthesizes ecological and ruminant nutrition evidence on N flows, emphasizing microbial processes, biological N2 fixation, plant diversity, and urine patch biogeochemistry, and evaluates strategies to improve N use efficiency (NUE). We examine rumen N metabolism in relation to microbial protein synthesis, urea recycling, and dietary factors including crude protein concentration, energy supply, forage composition, and plant secondary compounds that modulate protein degradability and microbial N capture, thereby influencing N partitioning among animal products, urine, and feces, as reflected in milk and blood urea N. We also examine how grazing patterns and excreta distribution, assessed with sensor technologies, modify N flows. Evidence indicates that integrated management combining dietary manipulation, forage diversity, targeted grazing, and decision tools can increase farm-gate NUE from 20–25% to over 30% while sustaining performance. Framing these processes within the global N cycle positions pasture-based ruminant systems as critical leverage points for aligning ruminant production with environmental and climate sustainability goals.

1. Introduction

Globally, human activities have more than doubled flows of reactive nitrogen (Nr), largely through synthetic fertilizer production and expansion of livestock systems, with significant consequences for water quality, biodiversity, and climate forcing via nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions [1,2]. Livestock accounts for a major share of anthropogenic Nr and contributes substantially to the exceedance of safe planetary boundaries for Nr [3]. Within this global context, pasture-based grazing systems are critical interfaces between Nr inputs and the wider environment. Nitrogen underpins plant productivity, forage nutritive value, microbial protein synthesis, and animal performance, yet mismanagement generates substantial N losses to air and water. In grazing dairy and beef systems, nitrogen use efficiency (NUE)—the proportion of N intake recovered in milk and meat—typically ranges from 10 to 35%, with the remainder excreted and lost as ammonia (NH3), nitrate (NO3−), and N2O [4,5]. This low NUE reflects imbalances between N inputs and productive demand arising from interactions among soil, plant, microbial, and ruminant processes [6]. Legume-based swards can enhance forage protein and reduce reliance on fertilizer N [4,7] when total N inputs exceed removal in animal products and plant biomass, surpluses and losses intensify, particularly under high stocking densities and uneven excreta deposition [8,9]. Grazing returns N in urine and dung, accelerates N cycling, and creates excreta hotspots associated with disproportionately high N2O emissions [10,11].

In ruminants, dietary N moves through tightly coupled microbial–host pathways. Rumen microbes convert degradable protein into microbial protein and ammonia. When protein supply exceeds fermentable energy, excess ammonia is converted to urea and excreted [12,13]. Balancing crude protein with energy and synchronizing rumen-degradable protein with fermentable carbohydrate increases microbial ammonia capture and N retention, and reduces urinary N losses [14,15]. Forage composition further modulates these flows. Plant secondary compounds, particularly condensed tannins, can reduce ruminal proteolysis, shift N excretion from urine to feces, and mitigate NH3 volatilization and N2O emissions [13]. Milk urea nitrogen (MUN) and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) integrate these processes and provide practical indicators of herd-level NUE [16,17,18]. Once excreted, urine and dung generate fine-scale heterogeneity in nutrient availability and soil N processes through rapid urea hydrolysis, nitrification, and denitrification, as well as slower organic matter decomposition [19,20]. Excreta distribution is shaped by grazing–resting cycles, terrain, and attraction to shade, water, and supplements, and emerging tracking tools (GPS, accelerometers, biologgers) now link animal movement and behavior to N return patterns and emission hotspots [21]. Similar mismatches between N supply, animal demand, and spatial N return occur across mixed crop–livestock and pastoral systems, including low-input systems in sub-Saharan Africa [22].

Despite extensive research, ecological and nutritional work on N in grazing systems remains fragmented. Ecological studies emphasize soil–plant–microbe dynamics and excreta hotspots, whereas ruminant nutrition studies focus on rumen function, diet formulation, and indicators such as MUN and BUN [23,24]. Global assessments indicate that single agronomic, nutritional, or behavioral interventions are unlikely to achieve the reductions in N losses needed to remain within planetary boundaries [25,26]. This review synthesizes ecological and ruminant nutrition perspectives on N dynamics and use efficiency in pasture-based grazing systems by linking soil microbial processes, forage chemistry, rumen and post-ruminal N metabolism, animal behavior, spatial excreta patterns, and farm-scale N balances, with particular emphasis on how rumen N metabolism, grazing behavior, and spatial N returns jointly influence NUE. The overarching objective is to clarify the mechanisms underlying low NUE, evaluate strategies to enhance N retention and reduce environmental N losses, and identify research priorities for pasture-based grazing systems that sustain animal performance while aligning ruminant production with environmental and climate sustainability goals.

2. Methodology

This article synthesizes evidence on nitrogen (N) dynamics and nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) in pasture-based ruminant systems using a narrative, interdisciplinary literature review. Relevant publications were identified through iterative searches of Web of Science Core Collection, Scopus, CAB Abstracts, and Google Scholar (final search completed in November 2025) using combinations of keywords including “nitrogen use efficiency”, “pasture-based”, “grazing”, “urine patch”, “dung”, “ammonia volatilization”, “nitrification”, “denitrification”, “nitrous oxide”, “rumen ammonia”, “microbial protein synthesis”, “protein–energy synchrony”, “plant secondary metabolites”, “condensed tannins”, and “mixed grazing”. Peer-reviewed articles published mainly from 1990 to 2025 were prioritized, with emphasis on recent meta-analyses, long-term field experiments, and mechanistic studies or models directly relevant to grazed pastures; seminal older papers were retained when they provided foundational concepts (e.g., NUE definitions, rumen N metabolism, or soil N transformation pathways). Studies were retained if they addressed N inputs, internal cycling, excreta-mediated hotspots, microbial/plant processes, ruminant metabolism, or management interventions in grazing contexts; studies focused solely on confinement/feedlot systems or non-ruminant livestock were excluded unless used for mechanistic comparison. Additional sources were identified via backward and forward citation tracking of key reviews and through targeted searches for specific forages or phytochemical interventions. Evidence was synthesized thematically and organized across linked scales (farm-gate, paddock/patch, and animal/rumen) to connect mechanisms of N transformation and partitioning with practical levers to improve NUE and reduce N losses.

3. Discussion

3.1. Nitrogen Flows in Pasture-Based Grazing Systems

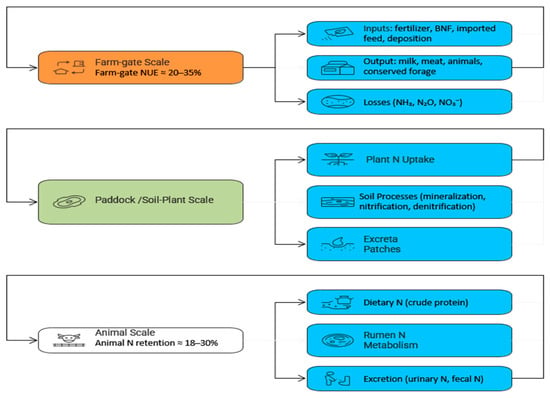

Pasture-based grazing systems exhibit nitrogen (N) flows that span interconnected biological, ecological, and behavioral processes. Nitrogen inputs derived from biological fixation, synthetic fertilizer, imported feeds, and atmospheric deposition enter a dynamic continuum of plant uptake, soil microbial transformations, and animal ingestion and excretion. Losses through volatilization, leaching, and N2O emissions emerge from these processes and are strongly modulated by diet composition, grazing behavior, and the spatial distribution of excreta. Synthesizing N dynamics across soil, plant, animal, and behavioral scales is therefore essential to evaluate and improve nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) and environmental performance in grazing systems. These multi-scale nitrogen flows are illustrated in Figure 1, which summarizes farm inputs, internal cycling, product exports, and loss pathways in a pasture-based grazing system.

Figure 1.

Conceptual representation of multi-scale nitrogen (N) flows and nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) in pasture-based grazing systems. At the farm-gate scale, N enters as fertilizer, biological N2 fixation, imported feed, and atmospheric deposition and leaves in animal products and conserved forage, with losses as NH3, N2O, and NO3−. At the paddock/soil–plant scale, N cycles through plant uptake, soil processes, and excreta patches. At the animal scale, dietary N is partitioned through rumen N metabolism into product N and excreted N. NUE emerges from the coupled interactions among these scales rather than from any single component.

3.1.1. System Boundaries and Nitrogen Use Efficiency

Nitrogen flows in grazing systems operate simultaneously at whole-farm, paddock, and animal scales, and inefficiencies at one level propagate to others. At the farm gate, inputs include imported feeds, mineral N fertilizer, biological N fixation (BNF), atmospheric deposition, and sometimes bedding or imported manure. In contrast, outputs comprise milk, meat, live animals, and conserved forage. Internal flows connect plant uptake, soil organic N dynamics, excreta deposition, and gaseous or leaching losses, indicating that NUE emerges from coupled ecological and nutritional processes rather than isolated components. Across intensive grazing dairy systems, farm-gate NUE typically ranges from 20 to 35%, with the remainder of N accumulating in soil, lost as gases, or exported in leachate [27,28].

At the animal level, biological retention is similarly low. Grazing dairy cows retain only 18 to 26% of ingested N in milk, and young heifers retain about 20 to 30% of dietary N [29,30], implying that roughly 60 to 80% of N intake is excreted [31,32]. Small physiological shifts, such as selecting cows with lower milk urea nitrogen (MUN) breeding values, can increase NUE by 3 [33], demonstrating that both genetics and nutrition influence N flows. However, NUE estimates vary widely depending on system boundaries. Schils et al. [34] show that Dutch dairy farm-gate NUE ranged from 14 to 44%, primarily driven by fertilizer rates, stocking density, and feed imports rather than by inherent biological limits. Powell et al. [5] noted that low NUE may still coincide with productive soil N accumulation, whereas Dijkstra al. [32] emphasized that even moderate NUE (25 to 30%) can be associated with high absolute N surpluses. Thus, efficiency ratios alone cannot diagnose sustainability unless absolute surplus N and the fate of accumulated N are also considered.

Reducing dietary crude protein (CP) can improve animal-level NUE and reduce excretory losses when CP exceeds requirements. For example, decreasing CP from 17% to 15% reduced urinary N excretion by about 20% without compromising milk yield [35], whereas further reductions below physiological thresholds decreased performance [36]. Genetic gains in NUE are possible [37], but remain smaller in magnitude than nutritional and management interventions [38]. Collectively, these findings indicate that improving NUE requires coordinated genetic, dietary, and management strategies, and that interpretations must be explicit about the spatial and temporal boundaries used to calculate NUE.

3.1.2. External Farm Inputs and Internal N Cycling

External N inputs and internal cycling together determine whether pasture-based systems function as N sources or sinks. At the farm and paddock scales, BNF from legumes, mineral fertilizer, imported feeds, and atmospheric deposition all contribute to the soil–plant–animal continuum. The relative contribution of these sources is strongly management-dependent. For example, grass–clover swards can supply N via Rhizobium-driven BNF at rates comparable to fertilized grass monocultures. Still, clover content and N inputs interact with stocking density, grazing pressure, and fertilizer strategy to shape long-term N balances [39,40].

Within the soil, mineralization processes regulated by temperature, moisture, C:N ratio, and microbial communities interact with plant uptake and root turnover to determine whether N is retained in soil organic pools, captured in above- and below-ground biomass, or left vulnerable to loss [41,42]. Integrated crop–livestock systems can improve N capture by distributing excreta more evenly and by using cover crops to intercept nitrate and recycle N back into the system [43]. However, long-term accumulation of 200 to 400 kg N ha−1 in soil [44] may either support climate mitigation or increase emissions and leaching, depending on how internal cycling is managed [45]. These patterns highlight that external inputs must be interpreted through the lens of internal cycling dynamics and system goals.

3.1.3. Loss Pathways: Leaching, Volatilization, and N2O Emissions

Loss pathways from grazing systems arise when N inputs and internal cycling exceed the capacity of soils and plants to retain reactive N. Under these conditions, losses occur primarily via ammonia (NH3) volatilization, nitrate (NO3−) leaching, and gaseous emissions produced by nitrification and denitrification, with nitrous oxide (N2O) and nitric oxide (NO) representing key reactive intermediates and dinitrogen gas (N2) representing the main terminal form of N returned to the atmosphere. Mechanistically, urine urea hydrolyses rapidly to NH4+ via urease, elevating soil pH and promoting NH3 loss. Nitrifiers—ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and archaea—oxidize NH4+ to NO2− and NO3− under aerobic conditions, while denitrifiers reduce NO3− to gaseous forms under anaerobic or intermittently wet conditions [46,47]. The balance between retention and loss is therefore strongly governed by soil moisture, oxygen availability, labile carbon, and the spatial distribution and intensity of excreta deposition. In addition, anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) and dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium (DNRA) may operate in waterlogged or compellingly reducing soil microsites beneath excreta patches. However, their quantitative contribution in temperate grazed pastures remains less well constrained than that of nitrification and denitrification.

Meta-analyses show that N2O emission factors from cattle excreta are generally lower than the IPCC default but highly variable, with a small number of high-flux events contributing disproportionately to annual emissions [48,49]. Patch-scale studies further reveal that concentrated urine loads create hotspots of nitrification and denitrification, while on free-draining soils NO3− leaching dominates during periods of high drainage and low plant [48,50,51]. Pasture stand age can further influence NO3− leaching risk by altering rooting continuity, plant N uptake capacity, and soil N mineralization dynamics, particularly following pasture establishment or renovation [50]. NH3 volatilization from urine is influenced by temperature, wind, pH, and soil cation exchange capacity, which, in turn, is shaped by soil texture and clay mineralogy, and can be moderated by botanical composition. Foresentence, multispecies swards containing plantain (Plantago lanceolata) and chicory (Cichorium intybus), whose deeper rooting, lower herbage N concentrations, and bioactive secondary compounds (i.e., tannins) dilute urinary N, enhance plant N uptake, and thereby reduce NH3 losses [52,53]. Regionally, nitrate leaching tends to dominate in humid climates, NH3 volatilization in warm alkaline soils, and N2O remains the most climate-intensive loss pathway [10,47]. In the following sections, we examine these pathways at patch, paddock, and landscape scales and discuss how nutrition, plant composition, and grazing behavior can be leveraged to reduce N losses while maintaining productivity.

3.2. Ecological Perspectives on Nitrogen Cycling at the Pasture Scale

At the pasture scale, nitrogen cycling emerges from interactions among soil microbes, plant functional groups, and the spatial patterning of excreta. Soil microorganisms mediate mineralization, nitrification, and denitrification, thereby regulating the balance between plant-available N, soil organic N storage, and gaseous losses. Plant functional composition and diversity, particularly the presence of legumes and deep-rooted forbs, determine how effectively these mineral N pools are captured and recycled within the sward [54]. Superimposed on these processes, excreta patches introduce localized N surpluses, creating biogeochemical hotspots that can either enhance productivity or intensify N losses, depending on soil conditions and management. Collectively, these ecological processes shape whether grazed pastures act as N sinks or sources and provide the mechanistic context for interpreting farm- and animal-scale NUE.

3.2.1. Soil Microbial Processes and Nitrogen Transformations

Soil microbes regulate N transformations in grazed systems through tightly coupled mineralization, nitrification, and denitrification pathways. For clarity, we refer to mineral nitrogen primarily as ammonium (NH4+) and nitrate (NO3−), and to gaseous losses as ammonia (NH3) and nitrous oxide (N2O). During mineralization, also referred to as ammonification, heterotrophic microbes decompose organic matter and convert organic N into ammonium (NH4+), with rates governed by substrate quality (e.g., C:N ratio and lignin or polyphenol content) and oil temperature and moisture [41]. Nitrification oxidizes NH4+ to nitrate (NO3−) via ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and archaea (e.g., Nitrosomonas) and nitrite-oxidizing bacteria (e.g., Nitrobacter), with process rates strongly modulated by soil pH, oxygen availability, and temperature [47]. Denitrification reduces NO3− to N2O and dinitrogen (N2) under anaerobic or intermittently saturated conditions through facultative anaerobes [55,56], such as Pseudomonas, with the N2O:N2 ratio controlled by oxygen status, the availability of labile carbon, and nitrate concentration [57]. Other nitrogen transformation pathways, such as anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) and dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium (DNRA), may also occur in saturated or strongly reducing soil microsites. Still, their relative importance in managed pastures is less well quantified than that of classical nitrification and denitrification.

In grazed pastures, these pathways are strongly shaped by spatial and temporal variability in soil moisture and carbon inputs. In particular, soil moisture modulates both mineralization and denitrification by controlling oxygen availability and substrate diffusion. Moisture fluctuations alter pathway dominance. Wrage-Mönnig et al. [58] reported that transient wetting events can shift N2O production from coupled nitrification–denitrification toward classical heterotrophic denitrification, particularly where nitrate and carbon accumulate. Integrated crop–livestock systems further modify microbial N dynamics by adding plant residues and cover crops with contrasting C:N ratios and residue chemistries, key components of substrate quality, thereby enhancing soil organic matter inputs, moderating the mineralization–immobilization balance, and synchronizing N release with forage uptake [43,59]. Over time, these microbial processes determine whether grazing systems accumulate soil organic N or leak reactive N through gaseous and leaching pathways [42,60] thereby linking pasture-scale ecology directly to whole-farm NUE outcomes.

3.2.2. Plant Functional Diversity, Legumes, and Biological Nitrogen Fixation

Plant functional composition shapes N cycling by determining biomass production, root distribution, litter quality, and the timing of N uptake. Legumes introduce new N to the system via symbiotic associations with Rhizobium, which reduces atmospheric N2 to ammonia through nitrogenase activity in root nodules. Because Rhizobium–legume symbioses are often host–strain specific, effective N2 fixation depends on the presence of compatible rhizobial strains. Introduced or non-native legumes may therefore fix little N where compatible symbionts are absent unless appropriate inoculation is used. This highlights the value of regionally adapted legume species and strain matching during pasture establishment [61]. This biologically fixed N is incorporated into legume biomass and enters the soil N cycle through root exudation, senesced leaves, and root turnover, with fixation rates influenced by legume proportion, defoliation intensity, and soil mineral N levels [39,40]. In addition to symbiotic Rhizobium–legume associations, free-living and associative diazotrophs in the rhizosphere and soil surface can also contribute to N2 fixation. Representative taxa documented in grass rhizospheres include associative diazotrophs such as Azospirillum spp. (e.g., Azospirillum brasilense strain Sp7), which colonize the rhizoplane and can enhance plant N status under low mineral-N conditions [62]. Endophytic diazotrophs that inhabit internal root tissues of grasses, such as Azoarcus sp. BH72 has also been shown to contribute fixed N to host plants under microaerobic conditions supported by root-derived carbon [63]. Additional well-characterized diazotrophs include Herbaspirillum seropedicae SmR1 and Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus Pal5, as well as free-living soil fixers such as Azotobacter vinelandii DJ that fix N2 while maintaining nitrogenase protection in aerobic environments [64]. However, their quantitative importance in managed pastures is less well constrained. Deep-rooted forbs and grasses complement legumes by capturing NO3− and water from deeper soil layers, thereby reducing NO3− leaching risk and stabilizing seasonal forage production under variable rainfall [65,66].

In temperate grass–clover swards, biological N fixation can supply approximately 150–250 kg N ha−1 yr−1 when clover comprises about 20–30% of the sward and fertilizer N inputs remain low [40,67,68]. Under these conditions, mixtures can match or surpass the productivity of high-N fertilized grass monocultures receiving 200–250 kg N ha−1 yr−1 [69,70]. However, the ecological benefits of legumes are highly sensitive to management. High mineral N rates above about 100 kg N ha−1 yr−1 suppress clover, reduce nodule activity, and promote grass dominance, thereby favoring non-fixing species, diminishing biological N fixation (including both symbiotic and free-living diazotrophs), and increasing reliance on external N inputs [71]. At the same time, stocking density and grazing pressure alter legume persistence [72]. Grazing effects are management-dependent, so moderate defoliation can reduce grass shading and improve light availability at the canopy base, thereby supporting clover persistence. In contrast, high stocking density or prolonged grazing pressure can suppress legumes through preferential defoliation and trampling, and by strengthening grass competitive advantage in urine-enriched patches. While selective grazing, trampling, and competition fueled by urine-derived mineral N can reduce clover content and destabilize mixtures [73,74].

Modern grass–clover mixtures are improved binary pastures of productive grasses with persistent clover cultivars selected for stolon density and grazing tolerance. Multispecies swards are intentionally diverse mixtures containing multiple grasses and legumes, often with forbs such as chicory and/or plantain. These swards offer management options to exploit functional diversity while moderating N surpluses. Cultivars with high stolon density and persistence can maintain 25–35% clover under rotational grazing and modest fertilizer N inputs (<50 kg ha−1 yr−1), thereby sustaining biological N fixation and limiting external N requirements [75]. Tactical spring fertilizer applications of 40–60 kg N ha−1 can boost early-season grass growth without permanently depressing clover or biological N fixation later in the season [76]. Moderate fertilizer strategies around 80 kg N ha−1 yr−1 may reduce clover-derived N by 30–40% but still increase total N supply by 15–20% [55], illustrating the trade-off between maximizing biological inputs and stabilizing forage yield. Economically, modern grass–clover mixtures can lower synthetic N fertilizer expenditure while maintaining similar or higher forage yields than fertilized grass monocultures because biological N fixation from clover can increase total N yield by up to 57% [56]. However, these gains come at the cost of more complex management to maintain species balance and control weeds, which can increase labor and knowledge requirements [77], and moderate mineral N strategies may reduce clover-derived N inputs by 30–40% [78]. Thus, economic viability depends on whether savings in fertilizer and improved environmental compliance outweigh these additional management demands, and is further shaped by market prices and policy incentives, such as area payments, that support grassland use [79]. Overall, plant functional diversity and legume-based biological N fixation can significantly enhance internal N cycling and soil N accumulation. Still, the net environmental and economic benefits ultimately depend on total system N loading, grazing intensity, and the persistence of legumes within the sward.

3.2.3. Excreta Patches as Hotspots and Their Spatial Patterning

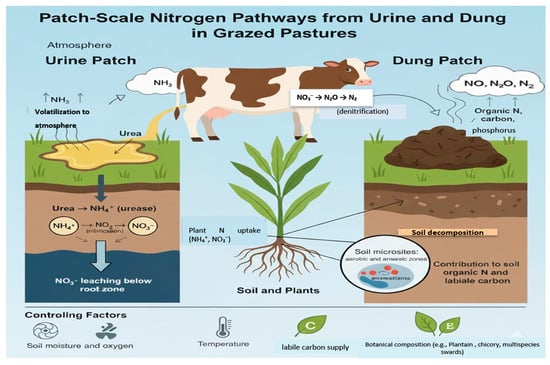

Excreta patches create extreme nutrient heterogeneity in grazed pastures by concentrating N, carbon, and other nutrients into small areas relative to the paddock. Urine deposition by grazing cattle can locally apply N loading rates exceeding 1000 kg N ha−1 within individual urine patches, primarily as urea, because N is delivered to a small wetted surface area [80]. In an intensively grazed dairy pasture, the mean urine patch area was 0.34–0.40 m2, and the annual urine patch coverage was 23.1 ± 2.2% of the paddock area, illustrating how grazing intensity influences the proportion of pasture exposed to these high-N hotspots [81]. Following deposition, urea in urine is rapidly hydrolyzed to NH4+ by urease, causing short-lived spikes in soil pH and NH3 concentration. Subsequent nitrification converts NH4+ to NO3−, and under moist or anaerobic microsites, denitrification reduces NO3− to N2O and N2 [46,47]. These conditions make urine patches disproportionate contributors to N2O emissions and nitrate leaching at the paddock scale. Meta-analyses report N2O emission factors from cattle urine, and dung generally in the range of 0.3–1.0% of excreted N, but values vary from about 0.07 to 5.9% depending on drainage, rainfall, and urine N load [19,82,83].

The balance between gaseous and leaching losses from patches depends strongly on soil physical conditions. On free-draining soils, up to 20–40% of urine N can be leached as NO3− during periods of high drainage and low plant uptake [50,84,85]. Where soils are wetter or poorly drained, denitrification processes dominate, increasing the fraction of N lost as N2O and N2 [47]. Ammonia volatilization from urine patches typically accounts for about 10–25% of excreted N and is influenced by temperature, wind speed, soil pH, and cation exchange capacity [52,86]. Botanical composition can mitigate these losses: multispecies swards containing plantain (Plantago lanceolata) and chicory (Cichorium intybus) dilute urine N concentration, alter urine chemistry, and reduce NH3 volatilization by approximately 30–50%, while also enhancing NO3− capture through deeper rooting and extended growth periods [87].

At the paddock scale, the cumulative effect of many urine and dung patches is a mosaic of nutrient-rich and nutrient-poor zones, with a relatively small proportion of the area receiving a large share of total N inputs (Figure 2). Overlapping urine and dung deposits can intensify N2O emissions and NO3− leaching by stacking labile carbon and high N in the same microsites [88].

Figure 2.

Patch-scale nitrogen (N) pathways from urine and dung patches in grazed pastures. A grazing cow deposits urine and dung that form distinct patches on the soil surface. In the urine patch (left), urea in urine is rapidly hydrolyzed to ammonium (NH4+) by urease, with a fraction volatilized to the atmosphere as ammonia (NH3). Remaining NH4+ is oxidized to nitrite (NO2−) and nitrate (NO3−) via nitrification, and NO3− can either be taken up by plant roots or leach below the root zone. In the dung patch (right), organic N, carbon, and other nutrients enter the soil more slowly through decomposition, contributing to soil organic N and labile carbon pools. Within the soil, microsites with aerobic and anaerobic zones regulate the balance between N retention and loss, including denitrification of NO3− to nitrous oxide (N2O), nitric oxide (NO), and dinitrogen (N2). Plants integrate these processes by taking up inorganic N (NH4+, NO3−) from the soil. The magnitude and direction of these fluxes are modulated by controlling factors such as soil moisture and oxygen, temperature, labile carbon supply, and botanical composition (e.g., plantain, chicory, multispecies swards).

3.3. Animal Nutrition Perspective on Nitrogen Partitioning and Use

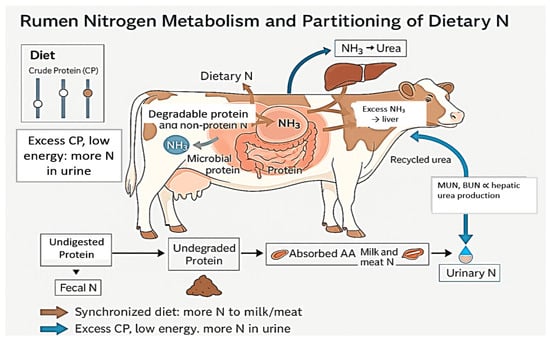

The ecological processes described in Section 3.2 determine how N is transformed and retained within soil and plant pools. But the amount and chemical form of N entering excreta hotspots ultimately depend on animal-level intake, metabolism, and partitioning. From a nutritional perspective, N use efficiency is governed by the synchrony between rumen N supply and fermentable energy, the balance between dietary crude protein (CP) and metabolizable energy, and the regulation of hepatic urea production reflected in milk and blood urea nitrogen (Figure 3 here). This section examines how rumen N metabolism, diet composition, and urea-based indicators together shape the proportions of N retained in animal products versus excreted in urine and feces, thereby controlling the N loads delivered to the patches described in Section 3.2.3.

Figure 3.

This conceptual diagram illustrates how dietary crude protein (CP) and fermentable energy regulate rumen N metabolism, microbial protein synthesis, and the partitioning of N into milk/meat, feces, and urine. Degradable protein and non-protein N are hydrolyzed in the rumen to ammonia (NH3), which is incorporated into microbial protein when fermentable energy is adequate. Excess NH3 is absorbed into the bloodstream and converted to urea in the liver, with urea partitioned between urinary excretion and recycling back to the gut. Undigested protein contributes to fecal N, whereas microbial protein and undegraded protein supply amino acids that support milk and meat N deposition. Milk urea nitrogen (MUN) and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) reflect hepatic urea production and serve as indicators of dietary protein–energy balance. The diagram highlights how synchronized diets (balanced CP and energy) shift N toward productive pathways, whereas excess CP with insufficient energy increases urinary N losses.

3.3.1. Rumen Nitrogen Metabolism and Synchrony

Interactions between dietary protein degradability, microbial capture capacity, and fermentable energy supply govern rumen N metabolism. Dietary protein and non-protein N are hydrolyzed to peptides, amino acids, and NH3-N by microbial proteases and deaminases [12]. Microbes assimilate NH3 using energy derived from carbohydrate fermentation to synthesize microbial protein, which is the primary amino acid source for the host [89]. Low NUE arises when NH3 production exceeds microbial demand, particularly in high-CP pastures where soluble protein outpaces available fermentable energy. Excess NH3 is absorbed across the rumen wall, converted to urea in the liver, and partitioned between recycling to the gut and urinary excretion [13].

Typical temperate pastures under highly productive, intensive management can contain CP levels of 18–24%, frequently exceeding animal requirements. In more extensive pasture systems, CP is often substantially lower; for example, meadow bromegrass CP ranged from 7.03% in early summer [13]. Keim and Anrique [29] showed that such surpluses elevate urinary N and depress NUE, especially when fermentable energy is limiting. Microbial growth plateaus at rumen NH3 concentrations of 5–8 mg dL−1; additional NH3 does not enhance microbial protein synthesis but increases urea production [13]. Conversely, NH3 < 2 mg dL−1 constrains microbial growth and fiber digestion, indicating a narrow optimal range that depends on diet type and microbial community composition [14]. Protein–energy synchrony improves microbial capture and reduces urinary N. Supplementing high-CP pasture with starch-rich feeds consistently reduces rumen NH3 accumulation and urinary N excretion [31]. Voglmeier et al. [87] demonstrated that inclusion of maize silage lowered excreta N by 18% and reduced N2O emission factors from 1.0% to 0.74–0.83%, linking rumen synchrony directly to downstream loss pathways. Timing further modifies outcomes. Albornoz et al. [90] found that split starch feeding, defined as dividing the daily starch supplement into two meals offered at different times of the day so that starch intake peaks coincide with peaks in rumen NH3 release, aligned peak NH3 availability with fermentable energy supply and reduced urinary N by 22% compared with providing the same starch dose all at once. Genetic variation also modulates responses. Cantalapiedra-Hijar et al. [91] showed that high-efficiency cows produced less NH3 and greater microbial protein per unit N intake on identical diets. Thus, rumen N metabolism depends on synchronizing protein degradability with fermentable energy, with dietary composition, feeding schedule, and host–microbiome interactions collectively determining how much N is captured in microbial protein versus excreted as urea that fuels the excreta hotspots described in Section 3.2.3.

3.3.2. Diet Composition, Intake, and Nitrogen Partitioning

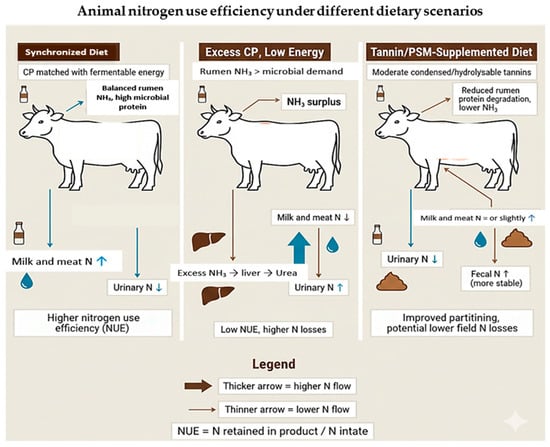

Diet composition governs N intake and excretion by determining CP concentration, protein degradability, carbohydrate type, and amino acid supply. Reducing dietary CP from 18–20% to 14–16% typically lowers urinary N excretion by 15–30% without compromising productivity, provided energy supply and metabolizable protein meet requirements [36]. Doran et al. [92] observed that reducing concentrate CP from 18% to 15% lowered MUN by 25% and urinary N by 20% without affecting milk yield. Multiple well-designed trials report that moderate CP diets (~14.5%) can sustain milk yield and composition while reducing nitrogen excretion, especially urinary N, thereby improving NUE [93,94,95]. However, CP reductions have limits. Huhtanen and Hristov [36] reported a curvilinear response: NUE increases sharply as CP declines from 19% to 16%, but plateaus below 15%, where an insufficient total amino acid supply constrains milk protein yield. Lee et al. [96] documented that high-yielding cows (>35 kg d−1 milk) fed CP < 15% experienced reduced milk protein and body condition loss, even when supplemented with rumen-protected amino acids, demonstrating that CP reductions below optimal thresholds compromise metabolizable protein supply rather than simply reducing surplus N (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Conceptual comparison of nitrogen partitioning in cows fed (left) a synchronized diet where crude protein (CP) supply is matched with fermentable energy, (middle) a high-CP, low-energy diet where rumen NH3 production exceeds microbial demand, and (right) a tannin/plant secondary metabolite (PSM)-supplemented diet. In the synchronized diet, balanced rumen NH3 and high microbial protein increase N retained in milk and meat and reduce urinary N, yielding higher nitrogen use efficiency (NUE). Under excess CP and low energy, NH3 surplus is converted to urea in the liver, increasing urinary N losses and lowering NUE. In tannin/PSM-supplemented diets, moderate condensed/hydrolysable tannins reduce rumen protein degradation and NH3 concentration, shifting N excretion toward more stable fecal N while maintaining milk and meat N at similar or slightly higher levels, thereby improving partitioning and potentially lowering field N losses.

Botanical composition also modifies N partitioning by altering forage quality and rumen fermentability. Diverse legume–forb swards generally enhance microbial protein synthesis and N retention. Dodd et al. [97] reported that cows grazing diverse swards increased milk N retention from 0.26 to 0.30 of N intake and produced 8–12% more milk than those on grass monoculture. However, these benefits diminish when pasture CP exceeds ~20% due to excessive N intake and elevated urea production [98]. Carbohydrate profile is equally influential. Hall and Huntington [99] showed that maize silage increases microbial protein flow by 15–20% compared with grass silage due to greater starch fermentation. Conversely, Gardine et al. [100] cautioned that very high starch levels (>30% of dry matter) depress fiber digestion and reduce overall N efficiency. Thus, optimal N partitioning requires integrating CP concentration, protein degradability, fermentable carbohydrate supply, and botanical diversity to reduce urinary N while maintaining milk and growth performance (Figure 4).

3.3.3. Indicators of Nitrogen Status: Milk and Blood Urea Nitrogen

Milk urea nitrogen (MUN) and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) reflect hepatic urea production and serve as integrative indicators of dietary protein–energy balance and urinary N excretion. Mechanistically, elevated rumen NH3 from excess degradable protein is absorbed, converted to urea in the liver, and equilibrates across blood, milk, and urine [31]. Kohn et al. [101] demonstrated strong quantitative relationships, with BUN accounting for 50–70% of the variation in urinary N excretion across diets.

Genetic variation in urea metabolism offers opportunities for long-term improvement in NUE. Correa-Luna et al. [33] showed that cows selected for low MUN breeding values excreted 12% less urinary N and achieved 3–4% point improvements in NUE while consuming identical diets. Bobbo et al. [102] similarly found heritable variation in MUN linked to rumen NH3 production and urea recycling efficiency. However, Richardson et al. [38] cautioned that reductions in MUN must be interpreted contextually; excessively low MUN may denote insufficient protein supply rather than improved efficiency, and environmental gains (5–8% reductions in urinary N) are generally smaller than those achieved through dietary manipulation (15–25%).

MUN threshold ranges are widely used to monitor herd-level protein balance. Zhao et al. [103] recommended 10–14 mg dL−1 for grazing dairy cows to balance production with environmental objectives. Conversely, Spek et al. [104] demonstrated that MUN–urinary N relationships vary with water intake, body weight, milk yield, and sampling time, explaining only 40–60% of the individual variation. Thus, MUN is most reliable for herd-level diagnostics rather than individual prediction. Sensor-based MUN monitoring is emerging as a tool for precision feeding. Lavery and Ferris [17] showed that inline MUN sensors reduced herd-average MUN by 15% and urinary N by 12% via dynamic CP adjustments. However, the environmental benefits of these nutritional adjustments depend on how the reduced urinary N is redistributed and transformed in the field through the excreta hotspots and soil processes [82,105] described in Section 3.2 and Section 3.4 Prevalent, MUN, and BUN provide valuable indicators of N status and support precision feeding, but they must be integrated with dietary, spatial, and soil-management strategies to achieve meaningful improvements in whole-system NUE.

3.4. Behavioral and Spatial Drivers of Nitrogen Return

The patterns of N partitioning described in Section 3.3 determine how much N is excreted in urine and feces, while animal behavior governs where this N is deposited across the landscape. Grazing circuits, resting-site preferences, and multispecies assemblages redistribute N from foraging areas to preferred lying, shading, and watering sites, thereby shaping the spatial arrangement of excreta hotspots characterized in Section 3.2.3. These behavioral and spatial processes control whether excreted N reinforces productive zones, creates chronic nutrient surpluses, or is lost via leaching and gaseous emissions.

3.4.1. Grazing Patterns, Resting Sites, and Excreta Distribution

Excreta deposition is mainly shaped by grazing behavior, with animals concentrating urine and dung in predictable zones influenced by diurnal rhythms, resource distribution, and social interactions. Cattle typically graze during early morning and late afternoon, then rest and ruminate near shade, water, or fence lines, depositing a disproportionate share of excreta in these areas [23,83]. Other livestock species differ in mobility and defecation behavior, leading to contrasting spatial patterns of nutrient deposition. Sheep and goats generally range more continuously and tend to distribute feces more evenly across paddocks than cattle, reducing the degree of clustering [106]. In contrast, horses often develop distinct dunging or “latrine” areas and avoid grazing near them, creating intense and persistent spatial heterogeneity in nutrient return across pastures [107]. This behavior creates persistent nutrient hotspots that elevate nitrate leaching and N2O emissions when N loads exceed the soil’s capacity to retain and transform reactive N. Betteridge et al. [108] showed that urination peaks during transitions between grazing and resting periods, amplifying deposition near water troughs and milking areas. Shade structures intensify spatial clustering. Carnevalli et al. [109] found that dairy heifers deposited 45% of dung in only 20% of the paddock area under silvopastoral shade. Carpinelli et al. [110] demonstrated that these concentrated dung zones increased subsequent crop N uptake by 15–25%, indicating potential agronomic benefits where hotspots coincide with target crop areas. However, White et al. [83] cautioned that N loading near water or shade often exceeds 500 kg N ha−1 yr−1, creating high-risk nitrate leaching and N2O hotspots that can offset productivity gains.

Urine–dung overlap further amplifies emissions. Auerswald et al. [111] found that overlapping patches produced 30–50% greater N2O emissions than separate patches because dung-supplied labile C enhances denitrification of urine-derived NO3−. Strategic resource placement can mitigate hotspot formation. Hirata et al. [112] reported that shifting water and shade redistributed resting areas by up to 50 m, reducing N deposition near streams by 20–30%. Nonetheless, behavioral inertia constrains effectiveness. Bailey et al. [113] observed that cattle continued to use familiar sites despite the availability of alternative shade, thereby limiting redistribution. Stocking density also matters; Schoenbach et al. [114] found that in small paddocks (<2 ha), high grazing pressure homogenized deposition regardless of resource placement, reducing the scope for spatial steering. Thus, excreta patterns result from behaviorally driven clustering around preferred resting sites, producing chronic nutrient hotspots superimposed on the soil and plant processes described in Section 3.2. Strategic design of shade, water, and grazing sequences can redistribute 10–30% of excreta and partially decouple resting sites from sensitive areas. Still, long-term effectiveness is constrained by herd familiarity, stocking density, and paddock structure.

3.4.2. Mixed-Species Grazing and Nitrogen Translocation

Grazing animals redistribute N across landscapes by consuming forage in nutrient-rich zones and excreting in preferred resting areas, creating cross-scale nutrient translocation patterns that influence vegetation structure and soil fertility. In mountain pastures, Svensk et al. [115] observed that Highland cattle grazed high-quality grass patches for 60–70% of their grazing time but deposited 30–40% of their excreta in Alnus viridis thickets used as shade, accelerating shrub expansion through localized nutrient enrichment. Riesch et al. [116] confirmed similar dynamics across multiple herbivore systems, with translocation distances from grazing to resting zones often exceeding 100 m and generating fertility gradients that shape plant community composition. Integrated crop–livestock systems may benefit from this redistribution. Lemaire et al. [59] and Carvalho et al. [43] demonstrated that manure-enriched resting zones increased soil organic matter and enhanced subsoil N retention. Carpinelli et al. [110] found 15–25% greater crop N uptake in areas previously used as cattle resting sites, suggesting the potential to use controlled resting patterns to transfer N intentionally. However, uncontrolled redistribution carries ecological risks. Schoenbach et al. [114] reported that nutrient-enriched resting sites became dominated by nitrophilous weeds, reducing pasture quality and grazing capacity. Environmental impact depends on the characteristics of receiving areas: translocation to well-drained soils increases leaching risk, whereas deposition in wetter, organic-rich areas may enhance denitrification and shift the balance of gaseous losses [116].

Mixed-species grazing modifies spatial patterns through complementary dietary and resting behaviors. Dumont et al. [117] showed that mixed sheep–cattle grazing increased herbage utilization by 10–15% through niche partitioning but did not quantify N losses. Rook et al. [118] reported that mixed grazing reduced patchiness and improved sward uniformity, indicating potential for more even nutrient return. However, differences in excreta N concentration between species (often 20–40% variation) complicate predictions of system-level N fluxes. Thus, mixed-species grazing systems may enhance spatial nutrient capture and dilute hotspots but require careful stocking rate calibration and spatial planning to avoid unintended nutrient accumulation. Landscape-scale N translocation remains a significant uncertainty in N budgeting, and integrating GPS tracking, behavioral observation, and soil N flux measurements is needed to quantify redistribution pathways and to design spatially explicit N management strategies that align animal behavior with the ecological and nutritional principles outlined in Section 3.1, Section 3.2 and Section 3.3.

3.5. Management Strategies to Enhance Nitrogen Use Efficiency and Reduce Losses

Building on the ecological, nutritional, and behavioral mechanisms outlined in Section 3.1, Section 3.2, Section 3.3 and Section 3.4, this section evaluates management strategies and tools to enhance NUE and reduce N losses in pasture-based ruminant systems.

3.5.1. Pasture Botanical Composition: Legumes and Multispecies Swards

Pasture botanical composition influences N cycling by altering N inputs, rooting depth distribution, forage nutritive quality, and animal N partitioning. This subsection primarily reflects evidence from cool-season temperate pasture systems under moderate to high rainfall. The mechanisms described are consistent across grazing environments. Responses may differ under warmer or drier climates because water limitation and seasonal growth patterns constrain legume persistence and shift the dominant pathways and magnitude of N loss. Legume-based swards supply biologically fixed N via Rhizobium symbiosis, reduce reliance on synthetic fertilizer, and enhance forage protein [40]. Egan et al. [93] showed that grass–clover mixtures receiving ~150 kg N ha−1 yr−1 matched the yields of grass monocultures fertilized at 250 kg N ha−1 yr−1, while reducing N surpluses and nitrate leaching. Lüscher et al. [40] synthesized evidence showing reductions of 30–60% in fertilizer N requirements without compromising production. Regardless of pasture type, rational N fertilization remains central to improving NUE and reducing losses. Mineral and organic N inputs should be aligned with soil testing and seasonal pasture demand, emphasizing appropriate rate, timing, and placement to avoid high-risk windows (e.g., prior to heavy rainfall, on saturated or frozen soils). Split applications and adjusting fertilizer N downward when legume BNF is high can improve plant capture and reduce surplus N cycling [94]. For organic amendments (slurry/manure/compost), timing relative to pasture growth and conditions that minimize volatilization and leaching are particularly important in grazed systems where excreta already dominates internal N fluxes. However, environmental outcomes depend on total system N loading. Ledgard et al. [95] documented that high-clover dairy systems exhibited leaching comparable to fertilized grass systems because total N inputs (BNF + excreta + deposition) exceeded removal. Eriksen et al. [119] similarly reported higher leaching in organic clover systems due to poor temporal synchrony between N release and crop demand. Legume persistence poses further challenges. Parsons et al. [120] showed that clover declined rapidly under high stocking rates due to selective grazing and shading, reducing long-term BNF benefits.

Multispecies swards incorporating plantain (Plantago lanceolata) and chicory (Cichorium intybus) offer additional benefits. Jezequel et al. [121] found that diversifying swards while reducing fertilizer N by 25–50% maintained milk yield, improved herbage NUE from 35 to 50 kg herbage N per kg applied N, and reduced N surplus by 30–40 kg N ha−1 yr−1. Plantain may reduce urine N concentration via altered water intake and renal N handling [122]. However, Gardiner et al. [100] found no change in urine volume, suggesting a physiological rather than behavioral mechanism. Minneé et al. [123] observed reduced urinary N (37–38%) and increased fecal N using 15N tracing, consistent with protein-sparing effects. However, Suter et al. [75] highlighted high variability in agronomic performance: multispecies swards underperformed when legume establishment failed, or forb palatability declined. Thus, botanical composition is a powerful but context-dependent lever requiring active management to maintain species persistence, synchronize N supply with demand, and integrate with grazing and dietary strategies for maximum NUE benefits. Pasture botanical composition also includes the weed community, which often responds strongly to nitrogen supply and can directly affect forage intake, animal health, and NUE. When reactive N inputs are high or spatially concentrated in urine patches, nitrophilous and competitive species can increase, lowering sward nutritive value and shifting N capture away from desirable forages [124]. Conversely, chronically low fertility, poor drainage, soil acidity, and repeated selective grazing can favor stress-tolerant or unpalatable taxa that reduce intake and increase patchiness [125]. Indigestible or toxic species are particularly important because they reduce usable herbage and can impose animal health risks, including sedges such as Carex spp., buttercups such as Ranunculus spp., docks such as Rumex spp., horsetails such as Equisetum spp., and poisonous species including Colchicum autumnale and Trollius altissimus. Managing N therefore also requires managing weeds through balanced fertilization, maintaining dense competitive swards, and using grazing and defoliation strategies that sustain legume and desirable grass persistence while limiting establishment of harmful species.

3.5.2. Precision Feeding and Nitrogen Management

Precision feeding aligns dietary CP supply with animal requirements to reduce rumen NH3 accumulation, enhance microbial protein synthesis, and minimize urinary N losses. Reductions of 1–2% units of dietary CP consistently lower urinary N excretion by 8–15% without affecting milk yield, provided metabolizable protein and energy needs are met [31,36]. Keim and Anrique [29] emphasized combining high-protein pasture with high-energy/low-CP supplements, particularly maize silage, to improve protein–energy synchrony. Voglmeier et al. [87] demonstrated that combining high-protein grass (22–24% CP) with maize silage reduced excreta N by 18% and N2O emission factors from 1.0% to 0.74–0.83%. Yang et al. [126] showed that temporal feeding strategies modify metabolic responses, providing starch 4–6 h after grazing improved synchrony between NH3 release and fermentable energy availability, reducing urinary N by 22% compared with 14% for simultaneous feeding. These findings highlight that both diet composition and timing influence N retention.

Precision tools use real-time indicators, such as MUN and BUN, to dynamically adjust diets. Studies have reported that sensor-guided dietary interventions achieved reductions in urinary nitrogen excretion ranging from 7% to over 40%, often linked to crude protein management [127,128]. However, practical adoption remains limited by infrastructure requirements, especially in grazing systems. Moreover, dietary improvements alone cannot address concentrated excreta deposition near shade and water; even with lower urine N concentration, hotspot formation may persist [129]. Thus, precision feeding reduces urinary N by 8–22% through improved protein–energy balance [46,103,107,130] but must be combined with pasture composition and spatial management to achieve whole-system gains. Future applications require integrating precision feeding with GPS-based excreta mapping and soil N models to capture interactions among diet, behavior, and spatial nutrient cycling.

3.5.3. Phytochemicals as Nitrogen Management Tools

Plant secondary metabolites, particularly condensed and hydrolysable tannins, offer a biochemical mechanism for improving nitrogen use by modulating rumen protein degradation, ammonia production, and N partitioning. Tannins form reversible protein–tannin complexes stable at rumen pH but dissociable in the acidic abomasum, reducing proteolysis and NH3 formation while increasing post-ruminal amino acid flow [15,131]. These shifts reduce ruminal NH3 surplus, lower hepatic urea synthesis, and shift N excretion from urine to feces, where N is less volatile and less susceptible to rapid nitrification and N2O formation [89]. Condensed tannin-containing forage legumes, such as birdsfoot trefoil (Lotus corniculatus), big trefoil (Lotus pedunculatus), and sainfoin (Onobrychis viciifolia), are typical in temperate pastures and provide a practical pasture-based tannin source that can reduce ruminal proteolysis and shift N excretion from urine toward feces [132]. Moderate tannin inclusion (2–4% DM) yields consistent reductions in urinary N. Zhang et al. [133] observed that quebracho and chestnut tannins lowered urinary N by 15–20% and increased fecal N by 10–15% without reducing milk yield. Aboagye et al. [134] found that hydrolysable tannins reduced methane by 12–18% and urinary N by 10–15% in beef cattle, indicating synergistic benefits for greenhouse gas mitigation. Thompson et al. [135] reported that ewes offered CT-rich willow (Salix Beagle) had 19% lower urinary N and 19% higher fecal N excretion than controls, clearly demonstrating a shift from urinary to fecal N. However, effects are strongly dose- and source-dependent. Excessive tannin levels (>5% DM) depress intake, fiber digestion, and microbial protein synthesis due to excessive protein binding. Muzzo et al. [131] emphasized the high variability across tannin types, dietary compositions, and animal species, which limits generalization. Soil-level responses remain largely unresolved. Carulla et al. [136] found fecal N from tannin-fed animals mineralized 20–30% more slowly, potentially reducing short-term N losses but also delaying plant N availability. Critically, only one study has directly linked tannin-induced urine chemistry changes to N2O fluxes: Luo et al. [137] reported a 25% reduction in N2O emissions from urine patches of tannin-supplemented cattle. However, high spatial variability obscured consistency, and no reduction in leaching was observed. Thus, tannins can reduce urinary N by 10–20% and alter excreta composition, potentially mitigating field-scale losses. However, high dose sensitivity, variable responses across systems, and limited soil-level evidence highlight the need for integrated pasture-scale validation linking rumen processes to soil N transformations.

3.5.4. Spatial Management: Shade, Water, and Grazing Design

Spatial management modifies animal movement and resting behavior to redistribute excreta and mitigate localized nitrogen hotspots. Stocking rate and pasture load interact with grazing system design to shape both excreta patch density and clustering. Higher pasture load increases excretal N returned per unit area and raises the likelihood of urine and dung overlap, intensifying local mineral N loads and increasing the risk of nitrate leaching and N2O emissions. Conversely, calibrating stocking rate to seasonal pasture growth and animal requirements can reduce whole-system N surpluses and dilute hotspot intensity by lowering patch density and by reducing the repeated use of the same resting site [138]. Since cattle preferentially rest near shade, water, and high-traffic corridors, manipulating the spatial configuration of these resources can influence where urine and dung accumulate [130,139]. Shade structures are particularly influential. Carnevalli et al. [109] reported that 45% of dung deposition occurred in only 20% of the paddock area under trees. This spatial clustering can be beneficial where additional fertility is desired—for example, in integrated crop–livestock rotations. Carpinelli et al. [110] showed that prior dung hotspots increased soybean N uptake by 15–25%, demonstrating the potential to use a resting-zone design as a nutrient-delivery tool. However, concentrated deposition near water or shade often produces excessive N loading (>500 kg N ha−1 yr−1), increasing nitrate leaching and N2O emissions [83]. Overlapping urine and dung deposition increases N2O emissions by 30–50% due to enhanced denitrification from combined labile C and a high inorganic N supply [112].

Strategic placement of water troughs or shade can shift resting areas by 20–30%, reducing N loading in sensitive zones such as riparian buffers [112]. Conversely, cattle exhibit strong site fidelity. Bailey et al. [140] found that herds repeatedly returned to familiar resting sites despite the presence of new shade or water, limiting the potential for redistribution. The grazing method also influences excreta patterns. Rotational and strip grazing reduce time spent near shade relative to the grazed area, thereby flattening spatial gradients. Betteridge et al. [108] documented reductions of 15–25% in excreta clustering under short-interval rotations. Building on these principles, modern regenerative grazing approaches, including Adaptive Multi-Paddock (AMP) grazing, Holistic Planned Grazing (HPG), and Ultra-high Stock Density (UHSD), use high animal density for short durations, followed by adequate recovery, to modify animal distribution and residence time. When moves occur before strong site fidelity develops, these approaches can serve as spatiotemporal distribution tools that reduce persistent congregation near attractants and promote more even nutrient return [141]. However, outcomes remain context-dependent and are not guaranteed if total N inputs remain excessive or if high-density grazing increases trampling on wet soils; thus, these approaches should be implemented alongside stocking-rate calibration and explicit N budgeting. However, total N inputs remain unchanged, and hotspots can shift to gateways and fence lines. Implementation barriers include the costs of infrastructure and labor, as well as variable success across landscapes. However, total N inputs remain unchanged, and hotspots can shift to gateways and fence lines. Implementation barriers include the costs of infrastructure and labor, as well as variable success across landscapes.

Overall, spatial management can redistribute 10–30% of excreta and mitigate high-risk hotspots, but behavioral inertia, paddock structure, and logistical constraints limit efficiency. The most reliable reductions in loss risk occur when spatial design (shade/water/fencing), grazing system timing (rotational or regenerative schedules), and pasture load are coordinated to reduce repeated deposition in sensitive areas and minimize urine–dung overlap that amplifies N2O emissions. Integrating spatial design with dietary strategies and pasture composition is essential for meaningful gains in N cycling at the paddock scale.

3.5.5. Technologies and Decision-Support Tools

Sensor technologies and decision-support tools enable integration of animal behavior, pasture dynamics, and nitrogen fluxes to improve real-time N management. GPS tracking and accelerometers quantify spatial use, grazing–resting cycles [142] and inferred urination and defecation events, allowing construction of spatially explicit N-return maps [21,143]. Hassan-Vásquez et al. [21] showed that in a Mediterranean dehesa paddock, two dung “hotspot” plots representing only 2.2% of the sampled area accumulated 24.3% of droppings, and 42.6% of feces were deposited within 8.7% of the paddock near the water trough, spatial clustering that models must represent to predict N losses accurately. Decision-support systems linking intake, N excretion, soil processes, and management variables provide practical tools. Overseer, Kankanamge et al. [144] and Giakoumatos et al. [145] recommended integrating animal N intake, excreta N, paddock-scale deposition assumptions, and soil N transformations to predict nitrate leaching. However, Cichota et al. [146] demonstrated that assuming a uniform distribution of excreta can underestimate losses because real-world deposition is highly clustered.

More advanced modeling approaches combine GPS-derived grazing intensity and soil moisture data with process-based models (e.g., APSIM). Studies showed that incorporating spatial grazing patterns improved predictions of animal grazing [147] pasture growth [148] and N leaching [21]. Inline milk MUN sensors enable adaptive dietary adjustments [17]. Integrating MUN monitoring with GPS excreta maps could link protein–energy balance with spatial N-return risk, but such integration remains experimental. Barriers include high cost, complex data processing, paddock-specific calibration requirements, and the need for secure digital infrastructure. Policy-driven adoption of decision-support tools is expanding. In New Zealand, regulatory N caps (30–50 kg N ha−1 yr−1) prompted adoption of modelling tools and stocking-rate adjustments, resulting in 15–30% reductions in nitrate leaching within five years [149]. However, compliance costs raise equity concerns for smaller farms. Collectively, technologies can improve representation of spatial N cycling and inform targeted interventions, but complexity, costs, and scalability limitations constrain widespread use. Simplified, affordable systems integrating GPS, MUN, and soil data remain a critical research frontier for operationalizing precision N management in grazing systems.

3.6. Integrating Ecological and Animal Science Perspectives

Integrating ecological and animal-nutrition perspectives requires viewing grazing animals simultaneously as metabolically constrained organisms and as mobile vectors of N across heterogeneous landscapes. From the animal side, rumen N metabolism, dietary CP concentration, protein–energy synchrony, and amino acid balance determine N intake, NUE, and the urine/feces N ratio [12,13]. From an ecological perspective, soil texture, hydrology, plant functional composition, and excreta patch dynamics govern how returned N is transformed, retained, or lost, with urine patches acting as transient hotspots that drive N2O emissions and nitrate leaching [11,150]. Across systems, livestock ‘population limits’ are most usefully expressed as stocking rate or pasture load constrained by carrying capacity and nitrogen loading risk, rather than as a single universal threshold. When grazing pressure exceeds seasonal forage supply and adequate recovery, pasture condition declines and excreta patch density and spatial overlap increase [151], which elevates nitrate leaching and nitrous oxide emissions by intensifying hotspot formation. Thus, sustainable animal numbers should be set using seasonal pasture growth and utilization targets, post-grazing residual and recovery goals, and explicit whole-farm nitrogen budgets that account for fertilizer, biological nitrogen fixation, and atmospheric deposition relative to product removal.

Legume-based and multispecies swards exemplify this coupling. Biological N fixation alters N inputs, while changes in forage quality and plant secondary metabolite profiles affect intake, N metabolism, and excreta composition, feeding back to soil microbial processes and N losses [40,121]. Plantain-rich swards can reduce effective CP degradability, lower urinary N concentration, and dilute individual urine patches via altered urination patterns, potentially decreasing N2O emissions per patch [122,123] net effects depend on total patch area and on compensatory mineralization dynamics, which remain poorly resolved [100]. Similarly, tannin-rich shrubs or trees influence both internal N partitioning and external spatial patterns by modifying grazing behavior, shade use, and resting sites, concentrating excreta under canopies and enhancing tree growth but potentially increasing leaching risks near waterways [109,115].

An integrated framework that couples (i) animal NUE models predicting N partitioning from diet and animal traits [12,152]; (ii) pasture growth and N cycling models capturing BNF, mineralization, and loss pathways [153,154] and (iii) spatial behavior models predicting excreta deposition patterns from movement and resource distribution [21] is required. Classical pasture N-cycling models, such as that of Scholefield et al. [155], showed that matching fertilizer N inputs with soil mineralization and site characteristics is critical for limiting NH3 volatilization, denitrification, and leaching while improving N use efficiency in grazed beef systems. Gregorini et al. [156], together with their mechanistic and dynamic model of a grazing dairy cow (MINDY), further emphasized that explicitly representing diurnal feeding motivation, sward structure, and spatial–temporal patterns of grazing and urination is essential for linking internal metabolic state and individual foraging decisions to paddock-scale N loading, leaching, and gaseous losses. Coupled models can evaluate scenarios such as adding clover and plantain, lowering supplement CP, relocating shade, or integrating tannin-rich forages, and quantify consequences for animal performance, N surpluses, and emissions. However, they require extensive calibration data and must capture feedback among stocking density, botanical composition, dietary CP, and excreta N loading, which can drive rapid system change if mismanaged [32,34,120]. Developing and simplifying such integrated models for practical use remains a major research priority.

3.7. Research Gaps and Future Directions

Key knowledge gaps continue to limit progress toward nitrogen-efficient pasture-based ruminant systems. A significant gap concerns how individual-animal variability scales to paddock- and farm-level N dynamics. Grazing animals differ in behavior, rumen microbiota, N metabolism, and MUN/BUN, but how these differences translate into spatial excreta patterns and N fluxes under real grazing conditions remains poorly quantified. Although genetic variation in MUN explains part of the variation in urinary N excretion [33], it is unknown whether low-MUN animals also differ in excreta spatial distribution or diurnal deposition patterns. Integrative studies linking individual-level monitoring (GPS, activity sensors, MUN/BUN, intake) with excreta mapping and soil N measurements are needed to determine how animal heterogeneity shapes whole-system N losses. The long-term ecosystem effects of tannins and other phytochemicals also remain uncertain. Short-term experiments show that tannins shift N from urine to feces and reduce N2O emissions [103,135], but multi-year impacts on soil organic N pools, microbial communities, and botanical composition are largely unmeasured. Only one study has quantified N2O emissions from tannin-modified urine patches [139], and no multi-year datasets exist to determine whether tannin-based strategies produce durable reductions in N losses or merely delay mineralization. Another major uncertainty is how pasture species composition controls system-level NUE under grazing. While legumes, deep-rooted grasses, and forbs can increase biological N inputs, improve nitrate capture from deeper soil layers, and alter forage CP and secondary metabolite profiles, the net effect on NUE depends on persistence across seasons, the timing of N release relative to plant demand, and how botanical composition modifies animal intake, urinary N concentration, and excreta patch dynamics. Long-term field studies are needed to identify which species combinations and functional traits consistently reduce N surpluses and loss risk across climates and grazing intensities, and to quantify trade-offs among productivity, sward stability, and environmental outcomes.

Scaling N processes across patch, paddock, farm, and watershed levels is another constraint. Patch-scale studies (<1 m2) provide mechanistic insights [150], but management requires validated spatially explicit N budgets. Integrating patch-scale fluxes with GPS-derived behavior, eddy-covariance N2O measurements, and hydrological models [157] demands multi-scale measurement campaigns across soil types and climates. Quantitative evidence for N cycling in multispecies grazing systems is also scarce. While complementary spatial use by cattle, sheep, and goats is documented [116,117], species-specific effects on excreta N composition, deposition patterns, and soil N transformations are poorly resolved. Finally, decision-support tools that integrate animal, pasture, and spatial processes remain data-intensive and are primarily used in research settings [153]. Simplifying model inputs, validating outputs under diverse grazing systems, and aligning tools with policy frameworks is likely to be essential for broader adoption and measurable reductions in N losses [149].

4. Conclusions

Pasture-based ruminant systems tightly couple animal N metabolism with soil–plant–microbial N cycling, and inefficiencies in these linked processes propagate as elevated reactive N losses. This synthesis indicates that low nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) arises mainly from crude protein supply exceeding fermentable energy, which increases ruminal NH3 production, hepatic urea synthesis, and urinary N excretion; from behaviorally driven excreta clustering that creates biogeochemical hotspots responsible for a disproportionate share of nitrate leaching and N2O emissions; and from temporal and spatial asynchrony between N inputs (fertilizer, biological N fixation, excreta) and plant uptake, which enhances soil mineral N accumulation and loss. Integrated management that combines precision feeding, legume- and forb-rich multispecies swards, targeted use of plant secondary metabolites such as tannins, and spatial manipulation of shade, water, and grazing allocation can increase NUE from approximately 20–25% to above 30% without reducing animal performance. Further research is recommended on multi-year, multi-scale experiments that jointly quantify rumen N dynamics, excreta chemistry, spatial deposition patterns, and soil N fluxes under realistic grazing conditions, with individual-animal monitoring (intake, MUN/BUN, microbiome, GPS-based behavior) explicitly linked to paddock- and farm-scale N budgets. Moreover, long-term field trials are needed to evaluate whether tannin- and phytochemical-based interventions produce sustained reductions in urinary N and N2O emissions while maintaining or enhancing soil organic N pools, microbial community function, and pasture botanical composition. Additional studies are needed to develop, calibrate, and simplify spatially explicit models that couple animal nutrition, pasture growth, and hydrological N transport into decision-support tools that are technically and economically accessible to small- and medium-scale grazing enterprises.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges Fred Provenza for his thorough review of the manuscript and for providing valuable insights that strengthened the conceptual framework. Sincere appreciation is also extended to Chandra Man Rai for his insightful discussion and constructive suggestions during the development of this work. During the preparation of this manuscript, I used Google Gemini (Gemini 3 Pro) to support initial figure image concept generation. I reviewed and edited all outputs for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| APSIM | Agricultural Production Systems simulator (crop–soil simulation model) |

| BNF | Biological nitrogen fixation |

| BUN | Blood urea nitrogen |

| CAB | Commonwealth Agricultural Bureaux (historical name associated with CAB International) |

| CABI | Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International |

| CP | Crude protein |

| CT | Condensed tannins |

| DM | Dry matter |

| DNRA | Dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium |

| DVE | Truly digestible protein in the small intestine (DVE protein evaluation system) |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas(es) |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| MINDY | Mechanistic, dynamic model of a grazing dairy cow |

| MUN | Milk urea nitrogen |

| N | Nitrogen |

| Nr | Reactive nitrogen |

| N2 | Dinitrogen (molecular nitrogen gas) |

| N2O | Nitrous oxide |

| NH3 | Ammonia |

| NH4+ | Ammonium |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| NO2− | Nitrite |

| NO3− | Nitrate |

| NUE | Nitrogen use efficiency |

| OEB2010 | Degraded protein balance in the rumen (2010 revision of the Dutch OEB system) |

References

- Galloway, J.N.; Townsend, A.R.; Erisman, J.W.; Bekunda, M.; Cai, Z.; Freney, J.R.; Martinelli, L.A.; Seitzinger, S.P.; Sutton, M.A. Transformation of the Nitrogen Cycle: Recent Trends, Questions, and Potential Solutions. Science 2008, 320, 889–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, M.A.; Howard, C.M.; Erisman, J.W.; Billen, G.; Bleeker, A.; Grennfelt, P.; van Grinsven, H.; Grizzetti, B. (Eds.) The European Nitrogen Assessment: Sources, Effects and Policy Perspectives; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; p. 612. [Google Scholar]

- Uwizeye, A.; de Boer, I.J.M.; Opio, C.I.; Schulte, R.P.O.; Falcucci, A.; Tempio, G.; Teillard, F.; Casu, F.; Rulli, M.C.; Galloway, J.N.; et al. Nitrogen emissions along global livestock supply chains. Nat. Food 2020, 1, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, R.J.; Williams, P.H. Nutrient Cycling and Soil Fertility in the Grazed Pasture Ecosystem. Adv. Agron. 1993, 49, 119–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, J.M.; Gourley, C.J.P.; Rotz, C.A.; Weaver, D.M. Nitrogen Use Efficiency: A Potential Performance Indicator and Policy Tool for Dairy Farms. Environ. Sci. Policy 2010, 13, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; You, L.; Amini, M.; Obersteiner, M.; Herrero, M.; Zehnder, A.J.B.; Yang, H. A High-Resolution Assessment on Global Nitrogen Flows in Cropland. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 8035–8040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guy, C.; Hennessy, D.; Gilliland, T.J.; Coughlan, F.; McCarthy, B. Growth, Morphology and Biological Nitrogen Fixation Potential of Perennial Ryegrass-White Clover Swards throughout the Grazing Season. J. Agric. Sci. 2018, 156, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oenema, O. Nitrogen Budgets and Losses in Livestock Systems. Int. Congr. Ser. 2006, 1293, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, K.; Panday, D.; Mergoum, A.; Missaoui, A. Nitrogen Losses and Potential Mitigation Strategies for a Sustainable Agroecosystem. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwman, A.F.; Boumans, L.J.M.; Batjes, N.H. Emissions of N2O and NO from fertilized fields: Summary of available measurement data. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2002, 16, 1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, K.A.; Jones, D.L.; Chadwick, D.R. The Urine Patch Diffusional Area: An Important N2O Source? Soil Biol. Biochem. 2016, 92, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, J.; France, J.; Ellis, J.L.; Strathe, A.B.; Kebreab, E.; Bannink, A. Production efficiency of ruminants: Feed, nitrogen and methane. In Sustainable Animal Agriculture; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2013; pp. 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristov, A.N.; Bannink, A.; Crompton, L.A.; Huhtanen, P.; Kreuzer, M.; McGee, M.; Nozière, P.; Reynolds, C.K.; Bayat, A.R.; Yáñez-Ruiz, D.R.; et al. Invited Review: Nitrogen in Ruminant Nutrition: A Review of Measurement Techniques Nure N Emissions in the Context of Feed Composition and Ruminant N Metabolism. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 5811–5852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Li, Y.; Wang, M.; Shen, Y.; Liu, M.; Xu, H.; Ma, N.; Cao, Y.; Li, Q.; Abdelsattar, M.M.; et al. Optimizing Dietary Rumen-Degradable Starch to Rumen-Degradable Protein Ratio Improves Lactation Performance and Nitrogen Utilization Efficiency in Mid-Lactating Holstein Dairy Cows. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1330876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, B.R.; Barry, T.N.; Attwood, G.T.; McNabb, W.C. The Effect of Condensed Tannins on the Nutrition and Health of Ruminants Fed Fresh Temperate Forages: A Review. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2003, 106, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonker, J.S.; Kohn, R.A.; Erdman, R.A. Using Milk Urea Nitrogen to Predict Nitrogen Excretion and Utilization Efficiency in Lactating Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 1998, 81, 2681–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavery, A.; Ferris, C.P. Proxy Measures and Novel Strategies for Estimating Nitrogen Utilisation Efficiency in Dairy Cattle. Animals 2021, 11, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakshi, M.P.S.; Wadhwa, M.; Makkar, H.P.S. Feeding of high-yielding bovines during transition phase. CAB Rev. 2017, 12, 006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]