Abstract

This study explores the potential of Precision Agriculture (PA) to optimize top-dressing nitrogen (N) fertilization in rainfed barley under drought conditions in Central Catalonia (Spain). Efficient N management is critical in Mediterranean dryland winter cereal systems, where water scarcity and environmental regulations limit fertilization strategies. Two plots (2.93 ha and 1.80 ha) were zoned using soil apparent electrical conductivity (ECa) and elevation data obtained with the VERIS 3100 ECa soil surveyor. An on-farm experimental design tested four N dose rates (0 kg N/ha, 32 kg N/ha, 64 kg N/ha, and 96 kg N/ha) across two management zones per plot. Yield data were collected using a combine harvester equipped with a yield monitor and were mapped using geostatistical methods. A linear model (ANOVA) was used to analyze barley yield (kg/ha at 13% moisture), with nitrogen rate and soil zone (management class) as explanatory factors. Results showed low average yields (~1200 kg/ha–1300 kg/ha) due to severe water stress during the 2022–2023 season. Non-fertilized plots (N0) and those receiving moderate (N64) or high fertilization (N96) achieved the best performance, with the latter likely enhancing crop N uptake during the post-stress recovery period. In contrast, low fertilization (N32) proved less effective. Marginal return analysis supported variable-rate N application only in one plot, whereas under drought conditions, a no-fertilization strategy proved more suitable in the other. Ultimately, additional trials conducted under more favourable climatic scenarios are necessary to assess and validate the effectiveness of Precision Agriculture-based fertilization strategies in rainfed barley.

1. Introduction

Nitrogen (N) fertilization remains a cornerstone of agronomic management in extensive cereal cropping systems, particularly in Mediterranean dryland environments where water scarcity and soil heterogeneity pose significant challenges to productivity and sustainability. Among winter cereals, barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) is widely cultivated in semi-arid regions such as Central Catalonia (Spain), where its performance is tightly linked to both nitrogen availability and climatic constraints, especially drought stress during critical growth stages. Furthermore, barley has a high N demand, averaging 24 kg N per ton of grain [1]. Therefore, efficient N fertilization strategies must combine accurate dosage with optimal timing, with top-dressing generally being more effective than basal applications under rainfed conditions. These findings support the approach proposed in [2,3], emphasizing the need to analyze crop responses to N to refine fertilizer recommendations and enhance N use efficiency (NUE).

The role of nitrogen in barley development is well established: it enhances vegetative growth, photosynthetic capacity, and grain protein content, contributing to both yield and grain quality [4,5]. However, excessive or poorly timed N applications can lead to environmental risks such as nitrate leaching and nitrous oxide emissions [6], particularly in areas with a Mediterranean climate and limestone soils that limit water retention capacity. In this context, optimizing NUE is not only an agronomic imperative but also a regulatory requirement under the European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP 2023–2027), which promotes sustainable fertilization practices and Precision Agriculture technologies. This is particularly relevant in the nitrate vulnerable zones (NVZs) of Central Catalonia (Spain), where N fertilization for barley cultivation is strictly regulated, limiting the maximum allowable N input per hectare and growing season.

An important aspect to consider in nitrogen fertilization strategies is the interaction between N supply and water availability, particularly under drought conditions. Barley is highly sensitive to water stress and, for this reason, N fertilization strategies under drought conditions must account for the complex interplay between water availability and crop physiological responses. NUE is context-dependent, varying with environmental stress and crop developmental stage [7]. Nitrogen and water limitations interact non-linearly, affecting biomass accumulation and grain formation [8]. Their findings suggest that optimizing nitrogen inputs under water stress requires dynamic, site-specific approaches that consider temporal and spatial variability in soil moisture and crop demand. Together, these two studies support the need for adaptive nitrogen management in barley, especially under drought, where traditional fertilization practices may lead to reduced NUE and increased environmental risk.

On the other hand, the application of nitrogen under drought can lead to contrasting outcomes: while it may enhance vegetative growth when water is sufficient, it can exacerbate stress symptoms when water is limited [9]. Drought stress significantly reduces photosynthetic activity and grain yield, and nitrogen fertilization may intensify these effects by increasing the plant’s water demand due to stimulated vegetative growth [10,11]. This imbalance can lead to reduced NUE and lower grain quality. Conversely, some studies also suggest that barley plants attempt to recover nitrogen uptake after the stress period, although with reduced efficiency. Thus, Ref. [12] demonstrated that under drought, nitrogen uptake from fertilizer (15N) was delayed and shifted to post-flowering stages, with modern varieties showing better recovery than historical ones. This implies that nitrogen application timing and dosage must be carefully adjusted to avoid yielding penalties and ensure optimal nutrient recovery. Overall, these findings reinforce the need for adaptive N management under drought-prone conditions. Precision fertilization, considering both crop developmental stage and water availability, is essential to mitigate the negative impacts of drought and optimize NUE [13,14]. Rainfed barley is a major crop in Mediterranean dryland systems, particularly in Central Catalonia where it often prevails under limited water availability. The increasing frequency and intensity of droughts due to climate change further complicate N management, reinforcing the need to optimize fertilization practices to sustain productivity and resource-use efficiency under variable climatic conditions.

In this context, Precision Agriculture (PA) offers a promising framework to improve N management through site-specific applications that account for spatial and temporal variability in soil and crop conditions. Farmers, even in vulnerable rainfed areas, can thus benefit from the implementation of EU agricultural policies and qualify for eco-scheme payments under the CAP if their N adjustment practices support environmental sustainability. Technologies such as soil apparent electrical conductivity sensors (e.g., VERIS 3100, Veris Technologies Inc., Salina, KS, USA), yield monitors, and geostatistical mapping tools facilitate the delineation of management zones, enabling tailored N prescriptions that better match crop requirements and soil characteristics [15]. In this respect, an on-farm experimentation study with winter cereals in a rainfed area of northeastern Spain using PA techniques [3] demonstrated significant differences in economic returns, calculated as partial net income. Negative outcomes were observed for low-fertility areas in several scenarios, underscoring the financial benefits of site-specific input management and the importance of adapting fertilization strategies to local conditions.

In addition, recent developments in remote sensing and UAV-based imagery have enhanced the precision of in-season N recommendations. Multispectral data from UAVs have been used to guide topdressing in wheat, improving NUE and reducing input costs [16]. UAV-derived fertilizer maps have also enabled significant reductions in N application—up to 49.6% in durum wheat—without yield penalties, while lowering residual soil nitrate and environmental impact [17]. Moreover, long-term studies comparing variable rate nitrogen (VRN) prescriptions based on NDVI and yield history have shown that profitability varies with seasonal weather patterns, underscoring the need for adaptive strategies that integrate multiple data sources [18].

Despite these technological advancements, the successful implementation of VRN fertilization requires robust local experimentation. On-farm trials are essential to validate agronomic responses under specific environmental conditions and to assess the economic viability of VRN strategies. This is particularly relevant in rainfed systems, where temporal variability in moisture availability can significantly influence N uptake and crop performance.

This study adopts an on-farm experimentation (OFE) approach to evaluate the suitability of differentiated N top-dressing in rainfed barley under drought conditions. Two plots were zoned using high-resolution soil data (apparent electrical conductivity and elevation), and four N dose rates (0 kg N/ha, 32 kg N/ha, 64 kg N/ha, and 96 kg N/ha) were applied across management zones. Yield data were collected using a combine harvester equipped with a yield monitor and were analyzed to derive response curves and marginal economic return. In short, the objectives are threefold: (i) to assess barley yield response to N fertilization under drought conditions, (ii) to evaluate the agronomic and economic feasibility of VRN application in dryland agricultural systems, and (iii) to demonstrate the value of on-farm experimentation as a decision-support tool for site-specific N management. The methodology and the results may be used to increase the NUE and, hence, the global efficiency and sustainability of rainfed barley farms in the Mediterranean region.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The field experiment was conducted in a rainfed spring barley cropping system (Solist cultivar, Florimond Desprez Ibérica) on two plots located in Castellfollit de Riubregós (Anoia county), in the semi-arid region of Central Catalonia, Spain. Solist is a malting barley variety valued for its good grain quality and high specific weight, and it is adaptable to diverse growing conditions. Sowing was performed in mid-December 2022 at a rate of 200 kg/ha and a depth of 2.5–4 cm. The trial followed an on-farm experimentation framework, incorporating active farmer participation in both the design and implementation of the nitrogen fertilization treatments.

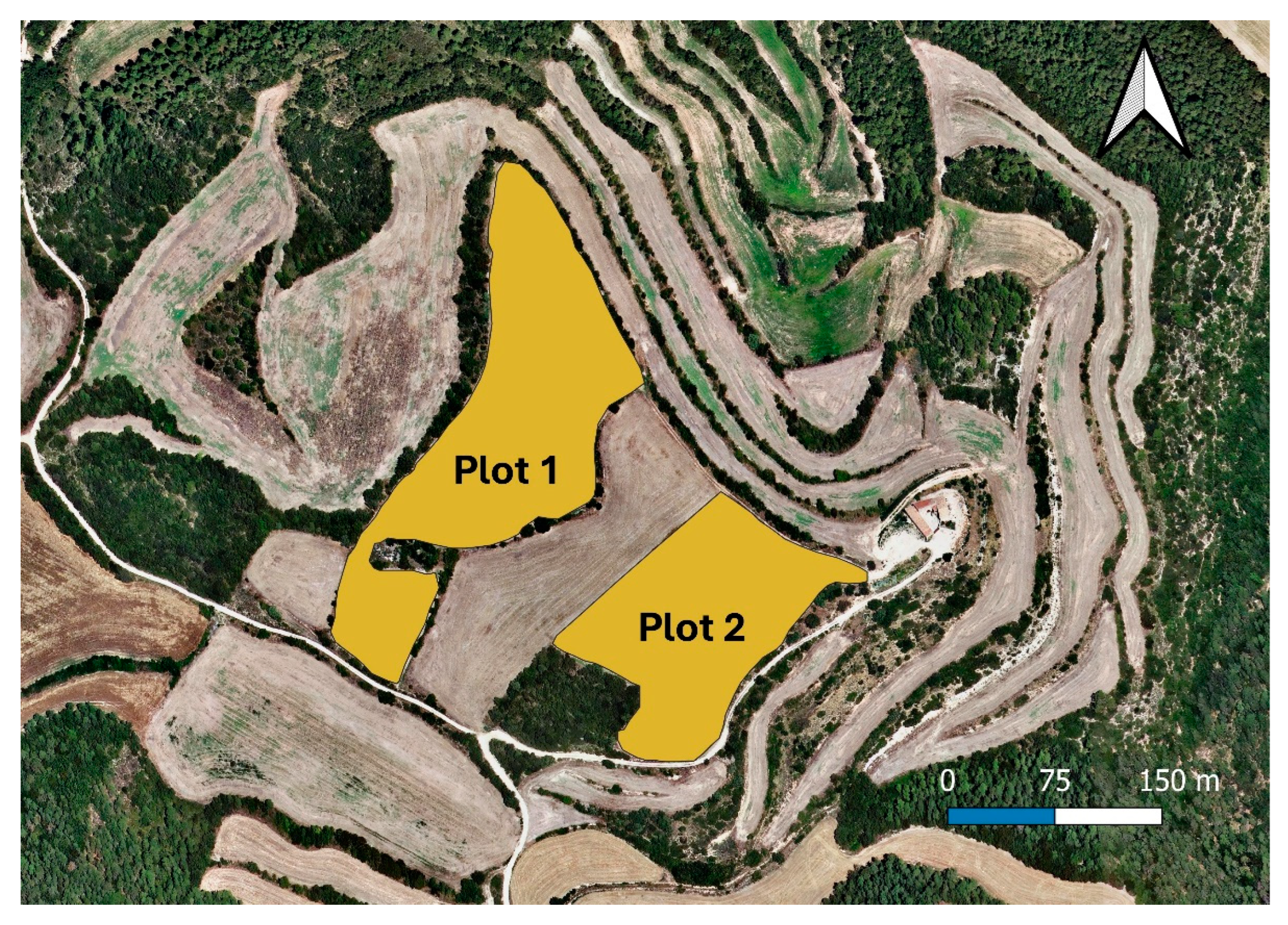

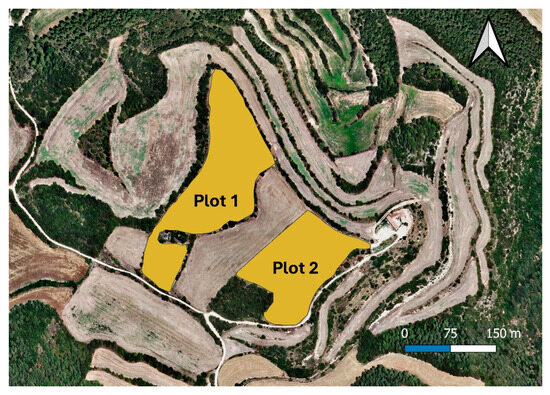

Figure 1 illustrates the two experimental plots used in the study (Lat 41°44′53.00″, Long 1°26′8.27″ WGS84). Plot 1 encompassed a total area of 2.93 hectares and featured an average slope of 14.5%, indicative of a notably uneven terrain. Plot 2, comparatively smaller with 1.80 hectares, also exhibited a pronounced elevation gradient, with an average slope of 11.6%. These topographic characteristics are relevant for understanding spatial variability in water retention and nutrient distribution, particularly under rainfed conditions.

Figure 1.

Plots 1 (2.93 ha) and 2 (1.80 ha) within the study area over the 2023 orthophoto (Cartographic and Geologic Institute of Catalonia, ICGC).

Soils in the region are predominantly developed over sedimentary formations of Miocene epoch, including marls, limestones, and gypsum-bearing layers [19]. These soils typically exhibit a fine to medium texture (loam to clay loam), moderate depth, and a relatively high pH (7.8–8.3) due to the calcareous parent material. Organic matter content is generally low, ranging between 1.2% and 2.0%, reflecting the semi-arid climate and the long-term use of conventional tillage in extensive cereal cropping systems [20]. Typically, two main soil classes alternate in the case study area: Typic Xerorthents and Calcic Haploxerepts [21]. The Typic Xerorthents are more frequently found at flat higher elevation positions and are shallow or moderately deep. Calcic Haploxerepts usually occupy locally lower elevations and present secondary accumulation of carbonates, being moderately deep to deep soils.

The climate is Mediterranean continental, characterized by low annual precipitation (350 mm–450 mm), concentrated in spring and autumn, and hot, dry summers with frequent drought stress episodes. Mean annual temperature ranges between 12 °C and 14 °C, with significant thermal amplitude. Because of the calcareous soils and semi-arid climate, soil fertility is generally limited by low organic matter content and restricted nutrient availability. Additionally, low rainfall and high temperatures reduce microbial activity and slow nutrient cycling, making adaptive fertilization strategies essential to sustain crop productivity.

2.2. Data Acquisition and Information Extraction

2.2.1. Soil Data (ECa) and Elevation

The VERIS 3100 sensor (Figure 2) (Veris Technologies, Inc., Salina, KS, USA) was used to measure the apparent soil electrical conductivity (ECa) at two depths: shallow (0 cm–30 cm) and deep (0 cm–90 cm). The VERIS 3100 is a galvanic contact sensor that operates by injecting an electrical current into the soil through a pair of transmitting electrodes. Depending on the soil’s physicochemical properties, the current is transmitted with varying efficiency. The system was designed to measure ECa over a defined soil volume, with particular attention to ensuring that the electrical current reached the depth explored by crop roots. As previously mentioned, the sensor provides dual-depth measurements. This feature enabled the detection of vertical variability in soil properties, facilitating the identification of whether the soil profile was homogeneous or composed of distinct horizons with differing edaphic characteristics [22].

Figure 2.

VERIS 3100 soil sensor used to measure the soil apparent electrical conductivity at two depths.

ECa measurements (mS/m) were georeferenced using a sub-metre accuracy Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS). Specifically, a Trimble AgGPS 332 receiver with SBAS EGNOS differential correction was employed, which also provided elevation data (m). Georeferenced measurements of soil electrical conductivity (ECa) and elevation were recorded at one-second intervals along parallel transects spaced 12 m apart. A total of 1593 points in Plot 1 and 1113 points in Plot 2 were collected, corresponding to point densities ranging from 543 to 618 observations per hectare. The interest in ECa measurements stemmed from the influence of soil properties—such as texture, moisture content, and salinity—on the electrical signal. Subsequently, ECa mapping using geostatistical techniques (kriging) enabled the assessment of spatial variability in both soil and topography and supported the delineation of potential site-specific management classes [15]. This information was key to designing an on-farm experimentation process aimed at optimizing nitrogen rates based on soil variability and barley response.

Raster maps of soil ECa and elevation were generated using the software VESPER v.1.62 [23]. Specifically, ordinary kriging was applied based on local spherical variograms (variability was modelled at the local scale, as more than 500 sampling points were available within each plot). For the fitting of each local variogram, between 90 and 100 neighbouring points around the prediction location were used, and the interpolated values were finally projected onto a 2 m resolution interpolation grid.

2.2.2. Barley Yield Measurements

Barley yield data were collected using the FieldView™ Yield Kit, a system compatible with any grain harvester and integrated with the Climate FieldView™ platform (Climate LLC., San Francisco, CA, USA), which enabled high-resolution spatial recording of harvest data.

The yield monitoring system consisted of: (i) an optical sensor and (ii) a speed sensor installed on the clean grain elevator. These components worked together to estimate the volumetric grain flow rate (, l/s) entering the grain tank. Additionally, a moisture sensor continuously measured the grain’s humidity during harvesting. All sensors operated at a measurement frequency of 1 Hz, ensuring high temporal resolution and real-time monitoring of both grain flow rate and quality. Simultaneously, the yield monitor recorded the harvester’s travel distance (m) and working width (m), allowing for the calculation of the harvested area per time unit (, ha/s). Yield per hectare was derived from these values, corrected for grain bulk density ( kg/l), and georeferenced using the harvester’s GNSS receiver with EGNOS correction. All data were stored in the yield monitor and displayed in real time on an onboard screen.

The harvester was calibrated prior to data collection to ensure accuracy in both volume and moisture readings. After harvesting, yield data were standardized to a reference moisture content of 13%. After removing yield outliers, raster-based yield maps were generated using kriging interpolation techniques [23] to support spatial analysis. Specifically, yield maps were generated by applying ordinary kriging in 6 m blocks, based on the prior fitting of a global spherical variogram (since less than 500 yield data points were available per plot). The interpolated values were then projected onto a 2 m resolution grid as the one for ECa and elevation.

2.3. Zoning and Design of the On-Farm Experiment

For plot zonation, an unsupervised classification algorithm—k-means clustering—was applied. The input variables consisted of the two interpolated maps of soil ECa shallow and ECa deep, along with a third elevation map derived from GNSS data collected during the VERIS 3100 sensor survey transects. In both plots (Plot 1 and Plot 2), classification was performed using two distinct classes (k = 2) through QGIS Desktop 3.16.4 software.

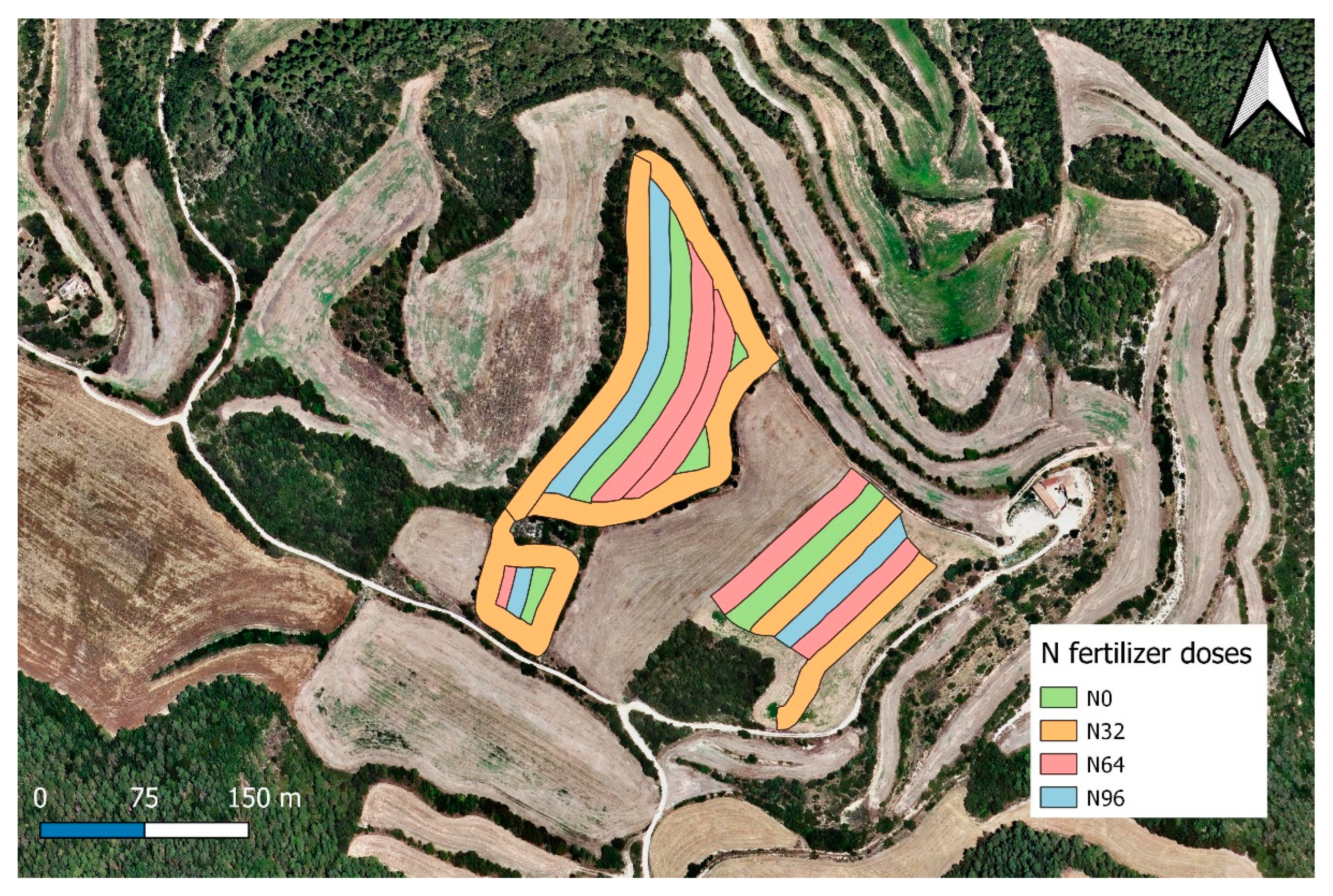

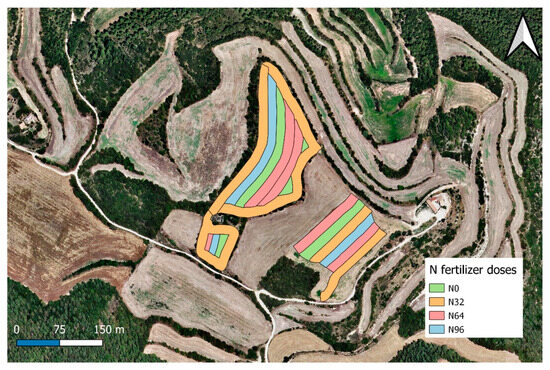

The experimental design followed an on-farm experimentation approach, where four nitrogen (N) fertilization rates (0 kg N/ha, 32 kg N/ha, 64 kg N/ha, and 96 kg N/ha) were applied in 18 m-wide strips, corresponding to the working width of the application equipment. Each N rate was implemented within both potential management classes identified through prior classification, resulting in a total of eight treatment combinations (4 N rates × 2 potential management classes). Nitrogen rates were selected to avoid exceeding recommended limits, as the plots were in a Nitrate Vulnerable Zone (NVZ). At the same time, higher dose rates were included to ensure a wide range of variation in the predictor variable (N fertilizer). This was necessary to properly fit the crop response curve. In line with OFE and its farmer-centric approach [24], the experiment was integrated into routine farm operations to deliver practical, robust insights. Despite limited soil N profiling, the design accounted for variability, ensuring relevant and interpretable results. The experimental layout is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Experimental design of N fertilization with differentiated rates of 0 kg N/ha (N0), 32 kg N/ha (N32), 64 kg N/ha (N64), and 96 kg N/ha (N96) over the 2023 orthophoto (ICGC).

Liquid nitrogen fertilizer (N32) was used for variable-rate fertilization across the experimental strips, applied with a sprayer featuring 18 m working width. The tractor was equipped with ISOBUS connectivity and operated through a task-based documentation system (Fendt Task Doc). This system recorded the operation type, tractor–sprayer configuration, field boundaries with guidance lines, and the prescription map used for the on-farm experiment. The 18 m strip width was suitable for subsequent harvest operations, allowing for up to three passes per strip with a 6 m combine header. For statistical analysis, only the central pass—or the two most central passes—within each strip were considered, retaining points inside the strips to minimize edge effects and ensure consistency regardless of one or two harvester passes.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Barley yield (kg/ha at 13% moisture) was analyzed using a two-way ANOVA to assess the effects of nitrogen fertilization and soil class. Nitrogen was applied at four rates (0 kg N/ha, 32 kg N/ha, 64 kg N/ha, and 96 kg N/ha), while soil classification into two management classes was based on a cluster analysis of shallow and deep ECa maps and elevation. The resulting 4 × 2 factorial design was evaluated using a non-additive linear model with interaction, as represented in Equation (1) [25],

where , , and ; was the k-th yield response at the i-th level of the main factor ‘N fertilization’ and the j-th level of the main factor ‘soil class’; represented the effect of the i-th level of the main factor ‘N fertilization’; the effect of the j-th level of the main factor ‘soil class’; the interaction between the i-th level of ‘N fertilization’ and the j-th level of ‘soil class’; and the experimental error (assumed to be independent and normally distributed).

For factors with a significant effect (p < 0.05), mean separation was subsequently performed using either Student’s t-test or Tukey’s HSD test, depending on whether the number of levels to be compared was two or more than two, respectively. This analysis was conducted separately for each plot. The software used was JMP® Pro 17.

3. Results

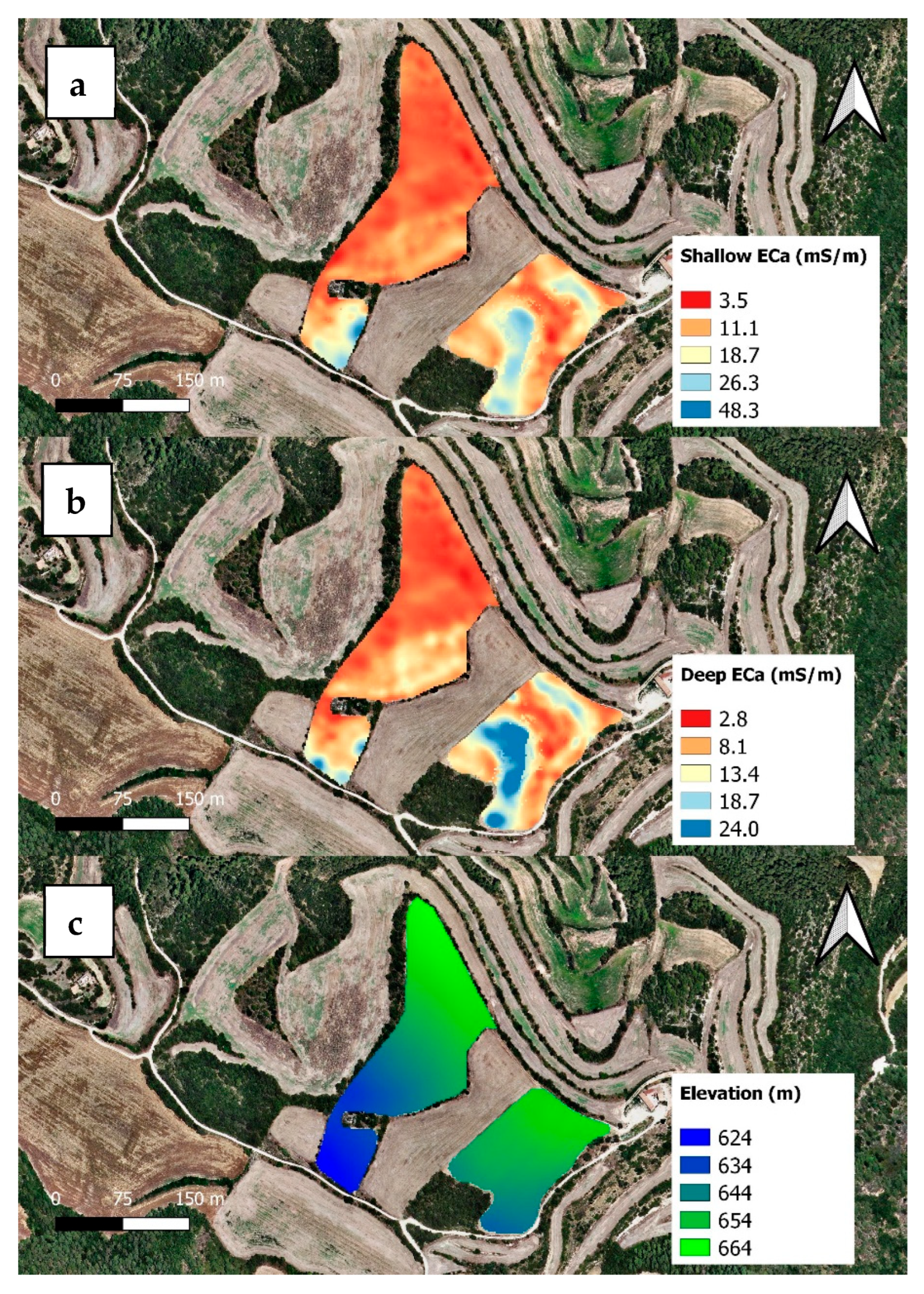

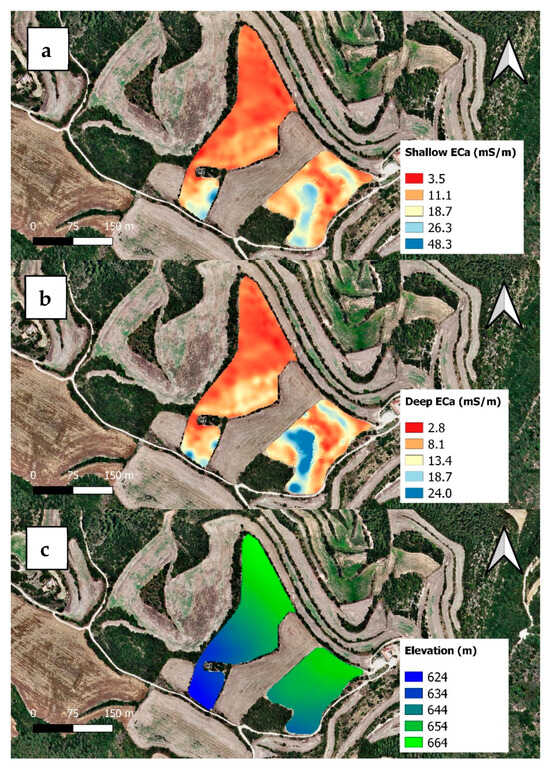

3.1. Mapping of Apparent Electrical Conductivity (ECa) and Terrain Elevation

The soil apparent electrical conductivity (ECa) and elevation maps for both Plot 1 and Plot 2 are shown in Figure 4. Additionally, summary statistics of ECa (shallow and deep) are presented in Table 1. Since all values were below 100 mS/m, the presence of salinity could be ruled out [26]. Both plots exhibited evident spatial variability, as indicated by the high coefficient of variation (CV), and showed a markedly contrasting pattern of variation, especially in Plot 2 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Raster maps of shallow ECa (a), deep ECa (b), and elevation (c) for plots 1 and 2 over 2023 orthophoto (ICGC).

Table 1.

Summary statistics of ECa in the study plots.

In Plot 1, shallow ECa values were slightly higher than those obtained for deep ECa. This result, along with higher ECa values towards the southern part of the plot, could be partially explained by elevation differences within the field, which also correspond to differences in soil types (see Section 2.1). With a variation of nearly 40 m, the southern area may act as a zone of accumulation—resulting in deeper soils—and also concentrating finer-textured material in the uppermost horizon. Both characteristics—soil depth and texture—significantly influence ECa values.

In Plot 2, despite the smaller elevation difference (19 m between the northern and southern parts) (Figure 4), the ECa pattern in both shallow and deep layers reveals a strong spatial variation structure, with well-defined zones of low and high ECa. Moreover, the soil appears to be homogeneous in depth. Plot 2, more than Plot 1, may probably offer greater potential for site-specific N fertilization.

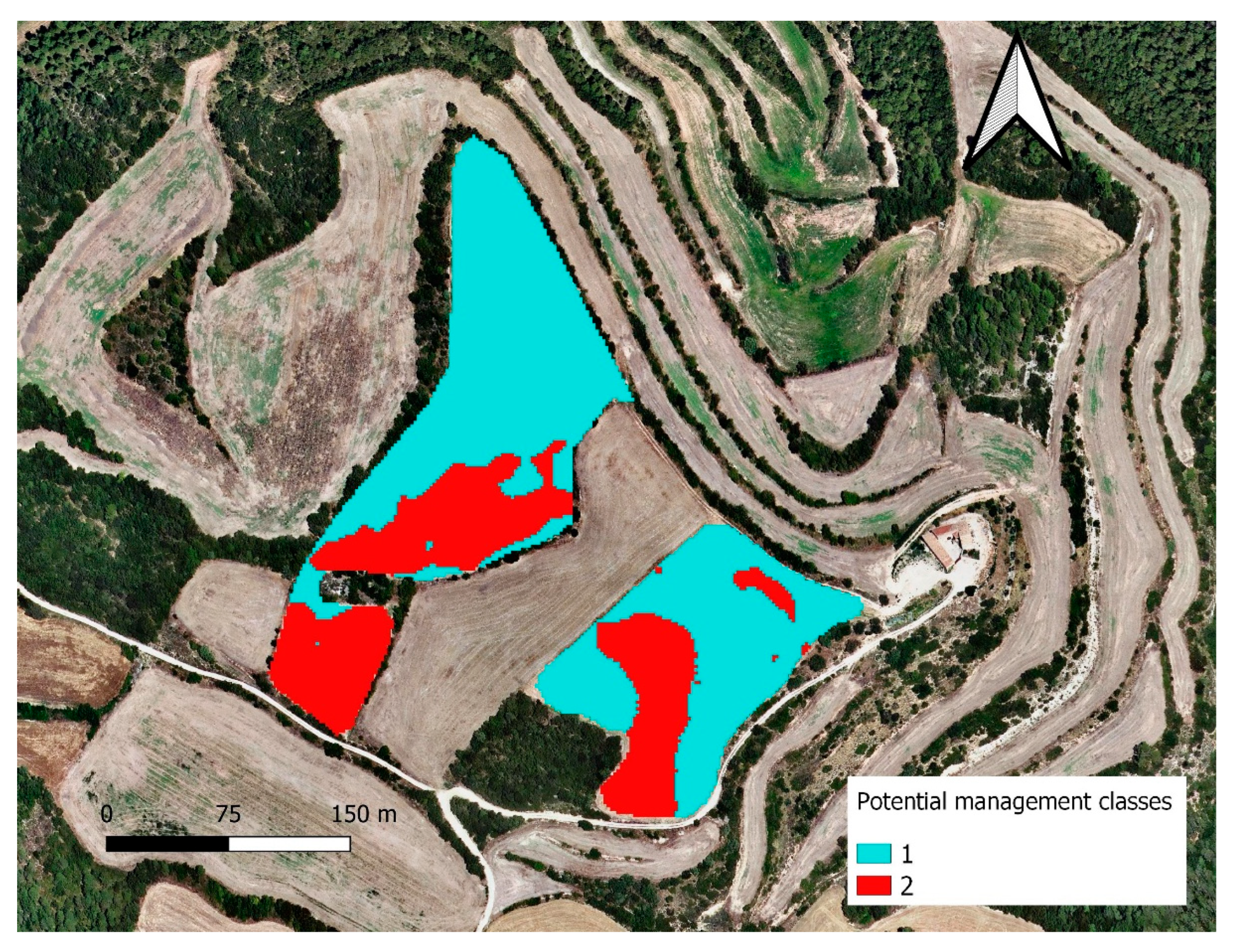

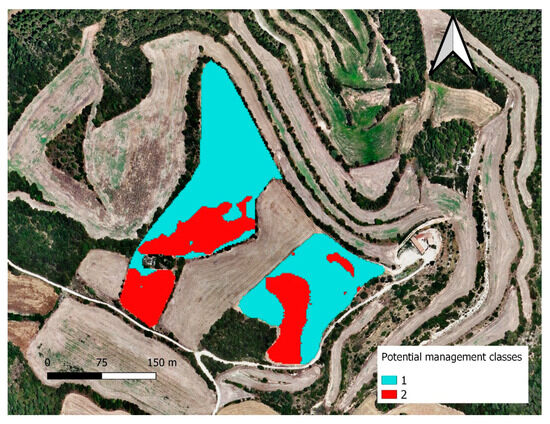

3.2. Plot Zoning

The resulting zoned maps are presented in Figure 5. In both plots, the number of clusters was restricted to k = 2. The decision to define only two potential management classes was based on two main considerations: (i) to simplify both the experimental setup and its subsequent interpretation—bearing in mind that the experiment is designed to be feasible for implementation by the farmer—and (ii) to demonstrate, if applicable, that Precision Agriculture (PA) can also be approached through a simple change, such as shifting from a uniform fertilization rate to a dual-rate strategy, better aligned with the specific needs of the two potential management classes identified within the plot.

Figure 5.

Classified (zoned) maps of plots 1 and 2 over 2023 orthophoto (ICGC).

The results of the unsupervised classification are presented in Table 2. For Plot 1, Class ‘1’—predominantly located in the northern part of the plot, where Typic Xerorthents are more abundant—is characterized by lower ECa values and higher elevation. In contrast, Class ‘2’ occupies the lower areas of the plot, with predominance of Calcic Haploxerepts, an average elevation approximately 16 m lower and slightly higher ECa values.

Table 2.

Values of the delineated potential management classes (PMC) within Plots 1 and 2.

As in Plot 1, Class ‘1’ in Plot 2 is characterized by slightly lower ECa values and higher elevation. However, in this case, the difference in mean elevation between the two classes is smaller—approximately 4 m—suggesting that, at least in terms of ECa and elevation, the soils in both classes are not markedly different. As shown in the classified map (Figure 5), Class ‘1’ occupies the largest portion of the plot, covering most of the northern areas as well as some zones in the lower part. In contrast, Class ‘2’, which covers a smaller area, is mainly concentrated in a central strip that extends from the middle of the plot down to its southern end.

Theoretically, based on soil and topographic characteristics, Class ‘2’ in both plots could delineate areas with higher productive potential compared to Class ‘1’. This assumption is grounded in the possibility that Class ‘2’ may be associated with deeper soils and a loam-clay texture, which would confer a greater water-holding capacity—an especially critical factor for ensuring adequate yields in rainfed cereal systems.

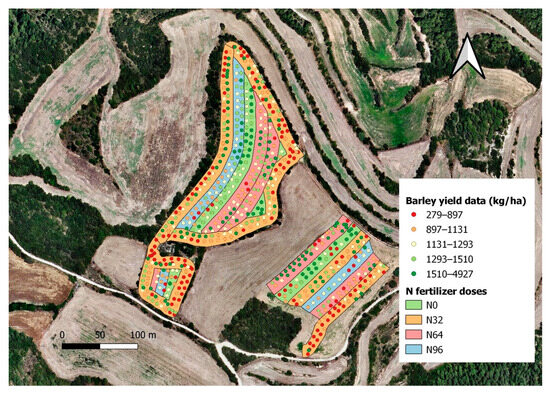

3.3. Assessment of Variable Rate N Fertilization

Barley yield was relatively low in both plots, largely due to the drought conditions experienced in 2023. Table 3 summarizes the filtered yield monitor data for barley, adjusted to 13% moisture content. Specifically, the average grain yield ranged from 1200 kg/ha to 1300 kg/ha, which is substantially below the expected yield of 3700 kg/ha–3800 kg/ha typically achieved under more favourable climatic conditions. A high degree of yield variation was observed within both plots (Figure 6); the CVs are notably high, reaching 46% in Plot 1 and 34.7% in Plot 2, resulting in yield maps with marked spatial variability (raster yield maps are not shown in order to maintain the focus on the field experiment).

Table 3.

Summary statistics of barley yield (kg/ha at 13% moisture content) in the study plots during the 2023 growing season.

Figure 6.

Experimental design of N fertilization (application rates of 0 kg N/ha, 32 kg N/ha, 64 kg N/ha, and 96 kg N/ha), and visualization of filtered harvest points (kg/ha @ 13%) used for statistical analysis over 2023 orthophoto (ICGC).

Figure 6 illustrates the on-farm experimental design, showing the filtered yield points overlaid on the different N rate strips. Although the N dose rates were randomly assigned and the area allocated to each dose was not exactly equal, the experimental setup ensures that yield data were available for each combination of ‘N rate’ × ‘soil class’.

At this point, a methodological clarification is necessary. The experimental design is unbalanced, as the number of observations per factor combination varies. In an effort to increase data availability, interpolated yield values (maps not shown) could have been used to model the yield response. However, this option was discarded for two main reasons. First, interpolated values are predictive estimates and therefore subject to interpolation error. Second, the smoothing effect of kriging may result in yield estimates that, in some cases, diverge considerably from the actual values recorded by the yield monitor. Therefore, although based on fewer data points, the ANOVA model (Equation (1)) was applied to the available actual yield data (Figure 6). The following two sections present the yield modelling results for each plot separately.

3.3.1. Plot 1

The ANOVA model (Equation (1)) yielded a statistically significant result (p = 0.0122). However, no interaction was detected between the N fertilization rate and the potential management class. The main effect of N rate was the only factor showing statistical significance (p = 0.0059) (Table 4).

Table 4.

ANOVA results of barley yield as a function of N rate and potential management class (Plot 1).

Mean separation for N dose rates (Tukey’s test) is presented in Table 5. Interestingly, the ‘N0’ treatment resulted in a relatively high yield, which—within the drought conditions previously described—was statistically comparable to the yields obtained under the ‘N64’ and ‘N96’ treatments. In contrast, the ‘N32’ dose rate was associated with a significantly lower yield, approximately 220 kg/ha less than that recorded for the ‘N64’ treatment.

Table 5.

Mean yield separation (kg/ha) across N fertilization rates in Plot 1.

3.3.2. Plot 2

In Plot 2, the analysis of variance (ANOVA) indicated a highly significant overall model fit (p < 0.0001). As detailed in Table 6, both N application rate and soil class had statistically significant effects on barley yield, with p-values of 0.0001 and 0.0147, respectively. Additionally, a significant interaction between N rate and soil class was observed (p = 0.0134), suggesting that the response to nitrogen fertilization was modulated by PMC characteristics.

Table 6.

ANOVA results of barley yield as a function of N rate and potential management class (Plot 2).

As shown in Table 7, the interaction between N rate and PMC revealed differentiated yield responses. In soil class ‘2’, only the unfertilized treatment (‘N0’) significantly increased yield compared to ‘N32’, suggesting a beneficial effect of no nitrogen input under specific conditions. This pattern was not observed in class ‘1’, where only the ‘N64’ treatment resulted in a significantly higher yield than ‘N32’. Regarding the initial hypothesis that class ‘2’ might exhibit greater productive potential due to more favourable soil and topographic characteristics (e.g., higher apparent electrical conductivity and lower elevation), the results offer a nuanced view. Class ‘2’ only showed a significant yield advantage under the ‘N0’ treatment, while no significant differences between soil classes were detected for the other nitrogen rates (‘N32’, ‘N64’, ‘N96’).

Table 7.

Mean yield separation (kg/ha) across N rate × soil class interactions in Plot 2.

4. Discussion

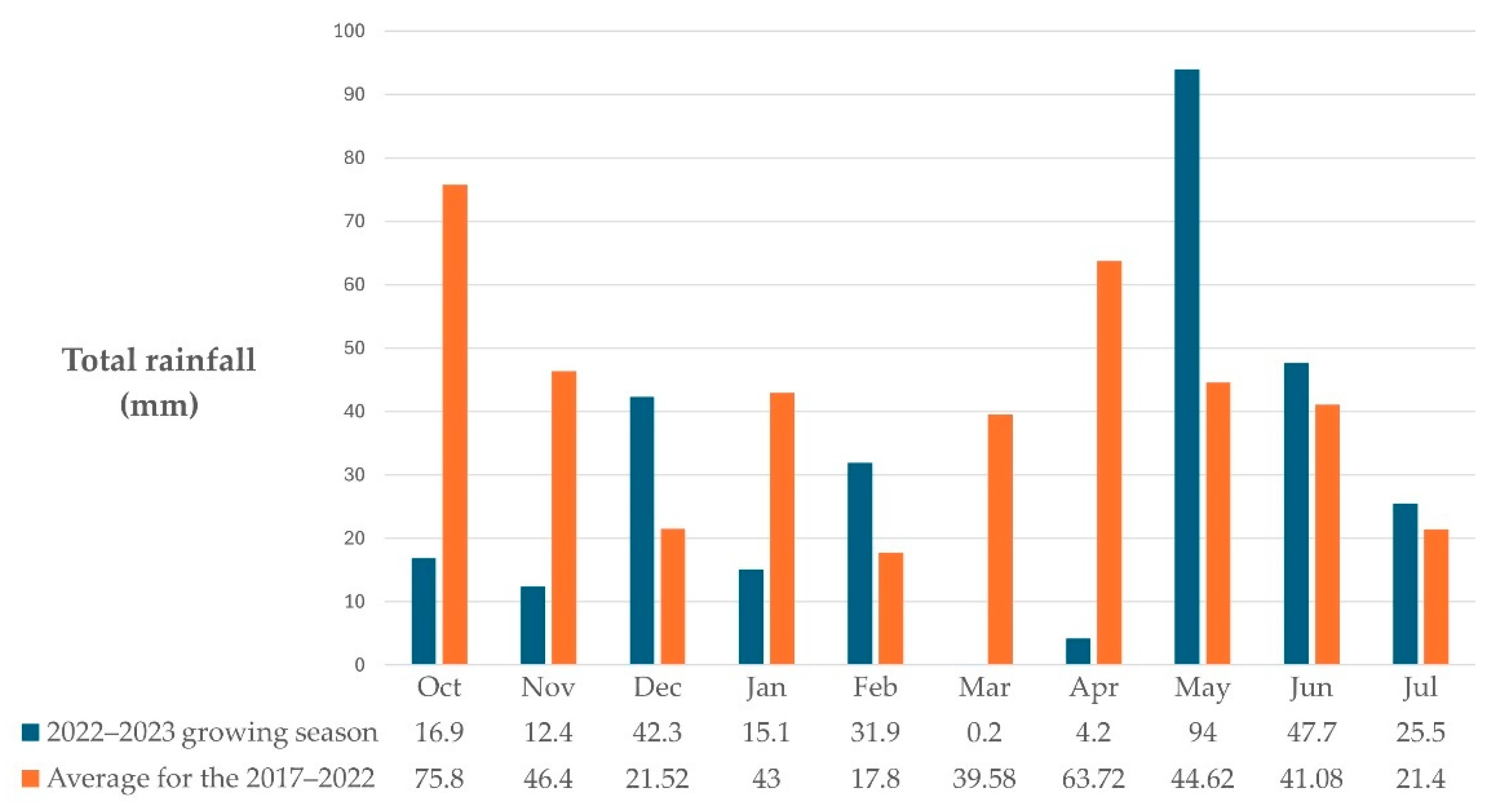

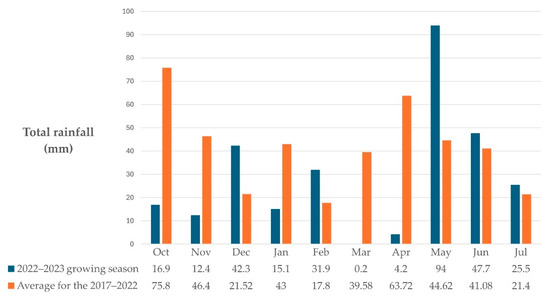

The 2023 growing season was particularly poor in terms of yield due to widespread drought conditions affecting the entire Anoia county. Specifically (Figure 7), total precipitation recorded during the 2022–2023 campaign amounted to only 290 mm, significantly below the average of 415 mm observed when analyzing the five previous campaigns before the drought episode. Although rainfall in November and December facilitated seed germination and early crop establishment, the subsequent lack of precipitation—particularly during March and April—clearly penalized yield performance. According to [27], prolonged spring drought conditions constrain plant growth, reduce tillering and spike density, and limit nutrient uptake, especially nitrogen.

Figure 7.

Distribution of precipitation during the 2022–2023 growing season and the average from the previous five seasons (2017–2022). (Source: Meteorological Service of Catalonia, La Panadella weather station).

It has been suggested that N fertilization, under specific drought conditions, may even intensify the negative impact of water scarcity and further reduce crop yield [11]. This effect has been reported in other extensive crops, such as maize [28]. In this recent study, it was found that under drought conditions, nitrogen fertilization decreased yield and increased crop water stress. Similarly, in [29] it was observed that nitrogen application exacerbated drought effects, with yield reductions increasing proportionally with nitrogen levels. These findings could help explain the yield patterns observed in the experimental plots, where the non-fertilized strips (N0) showed clearly higher—although still limited—production compared to the strips where nitrogen was applied. The fact that, in both Plot 1 and Plot 2, the N64 treatment achieved a yield comparable to N0 is not easy to interpret. As proposed in [9], when early nitrogen uptake is restricted, crops attempt to compensate later with low efficiency, often requiring additional inputs. This same idea is addressed in [12], indicating that the crop may attempt to recover the nitrogen not absorbed during the stress phase, albeit with reduced efficiency, which could require a certain degree of over-fertilization. In our case, this recovery might have been supported by the favourable rainfall in May (Figure 7), potentially compensating for the initially low spike density with grains of higher specific weight and contributing to a partial yield recovery, as referenced in [9].

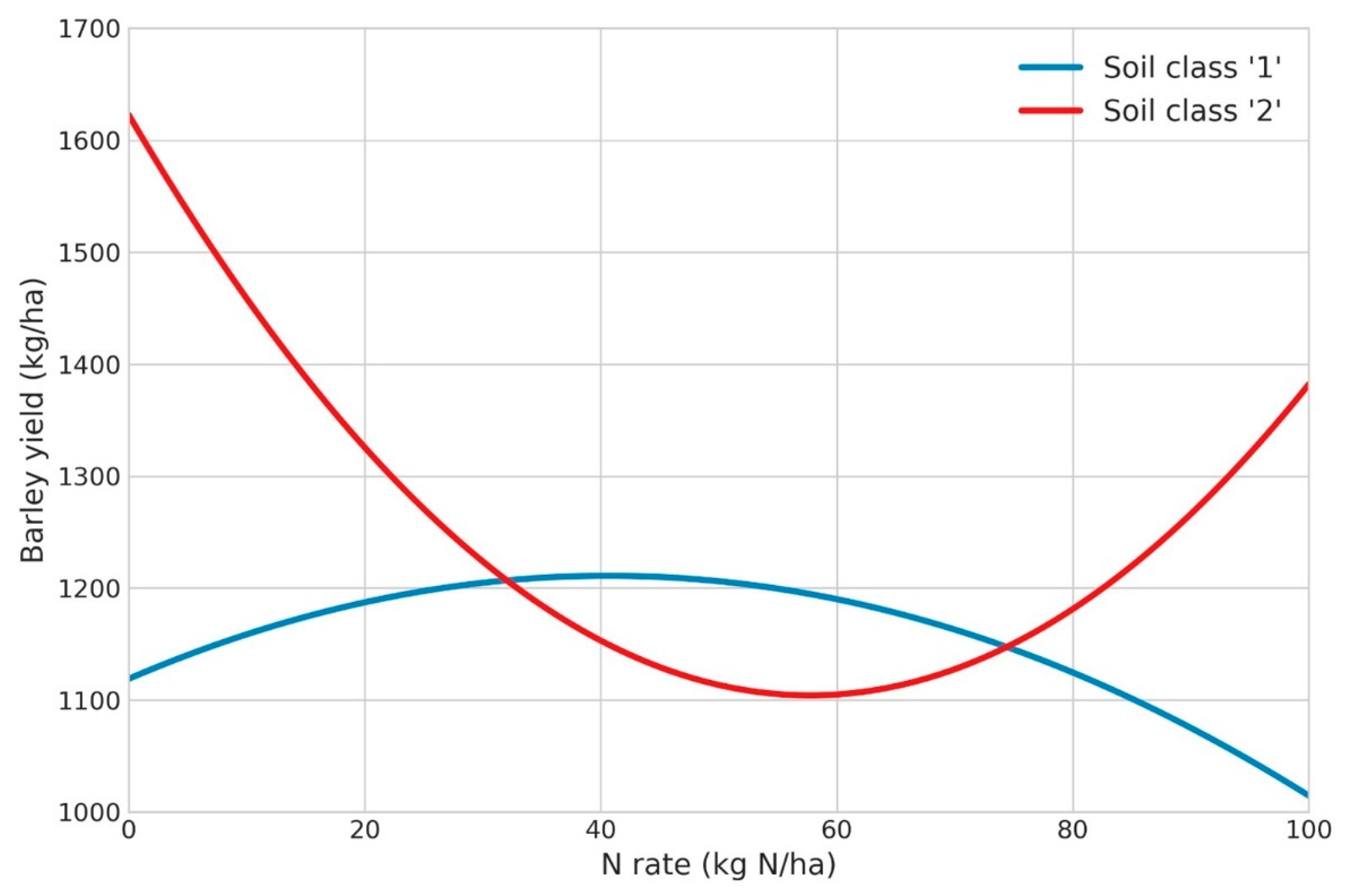

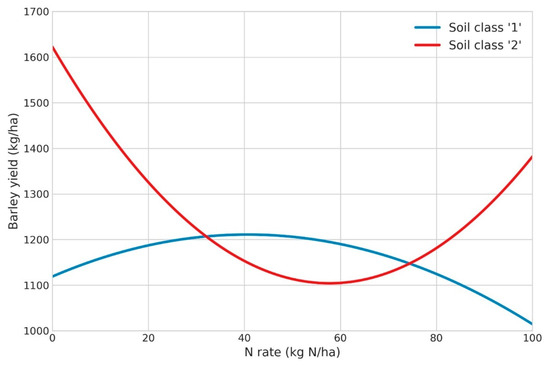

4.1. Barley Response Curve to Nitrogen Fertilization Rates

In Plot 2, where barley yield was significantly influenced by the interaction between N dose rate and soil class, response curves were fitted separately for soil class ‘1’ and class ‘2’. Drought conditions clearly shaped the crop response and the type of curve obtained. In an attempt to improve the fit, quadratic response functions were applied (Figure 8), which deviate notably from what would typically be expected in this type of trial. No clear increase in yield followed by stabilization or decline was observed with increasing N fertilization. On the contrary—particularly in soil class ‘2’—N application appeared counterproductive under initial drought conditions yet tended toward partial yield recovery at higher nitrogen dose rates, possibly due to improved nutrient uptake under more favourable rainfall conditions later in the season. The interaction between nitrogen fertilization, drought stress, and yield reported in [9] aligns with our findings.

Figure 8.

Barley yield response curves (kg/ha) to nitrogen fertilization dose rate (kg N/ha) in Plot 2, with separate models fitted for soil class ‘1’ and soil class ‘2’.

The fitting of a quadratic response function for each soil class is shown in Figure 8. Specifically, the function fitted is displayed in Equation (2),

where is barley yield (kg/ha), and is the nitrogen fertilizer dose rate (kg N/ha). The response model for soil class ‘1’ is described by Equation (3):

and for soil class ‘2’, by Equation (4),

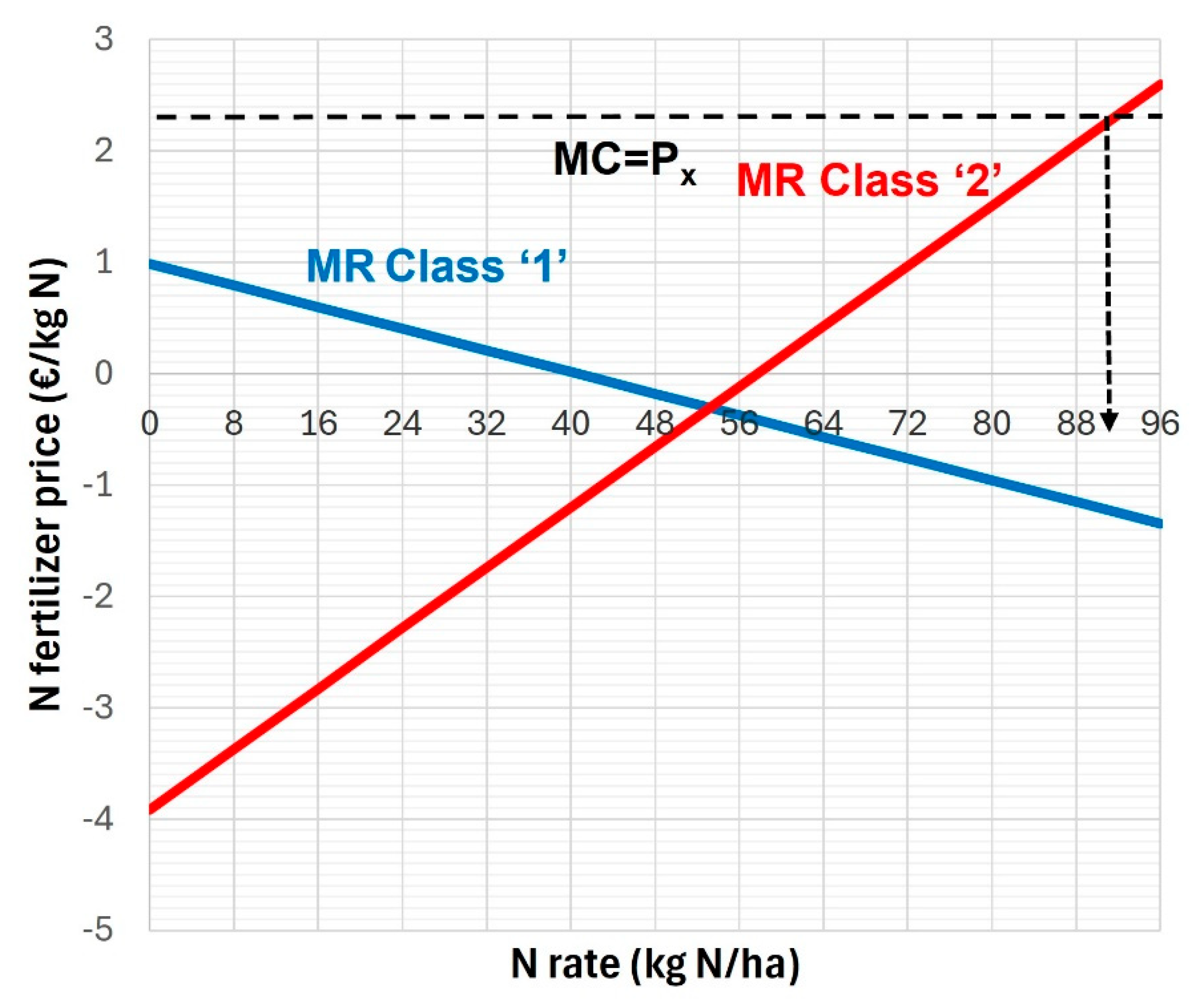

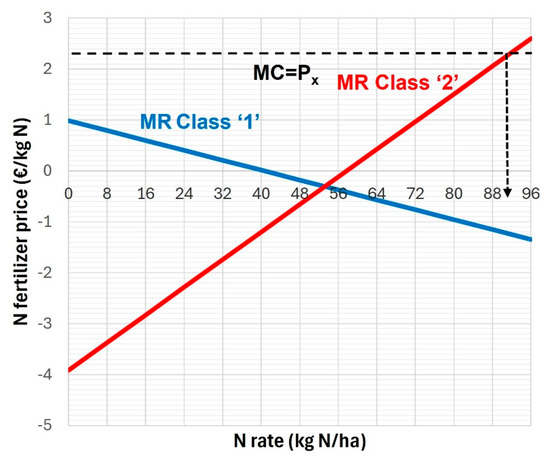

4.2. Marginal Economic Analysis

Taking as reference the response curves obtained for Plot 2 (a plot that, due to the significant interaction between nitrogen rate and soil class, emerges as a candidate for variable-rate N fertilization), the next step is to decide on the optimal N application rates for each management class. This is undoubtedly one of the key challenges in Precision Agriculture [30]. A suitable approach to this issue, grounded in production economics, involves identifying the N application rate that maximizes economic return. This corresponds to the point at which the marginal cost of applying an additional unit of nitrogen equals the marginal revenue generated by the resulting increase in barley yield [31]. The gross margin or profit (considering only the cost of the fertilizer) can be expressed using Equation (5),

In this equation, GM, R, and C represent the values (€/ha) of profit, revenue, and cost, respectively. The cost of fertilization is calculated as the product of the applied dose rate x (kg N/ha) and the input price (€/kg N), while the revenue is simply the product of the obtained yield (kg/ha) and the unit price of barley (€/kg). Maximizing the margin involves differentiating and setting Equation (5) equal to zero (Equation (6)).

In summary, the economically optimal nitrogen rate is the point at which the marginal cost (MC) of N equals the marginal revenue (MR) from the associated increase in crop yield, satisfying the condition MC = MR.

Table 8 summarizes the barley and nitrogen fertilizer prices used in the analysis, whereas Figure 9 provides a graphical representation of the corresponding results.

Table 8.

Unit prices of barley and nitrogen fertilizer.

Figure 9.

Marginal revenue equalization for N use vs. input cost ([29]). The arrow indicates the optimal dose rate.

As shown in Figure 9, for class ‘1’, the unit price of N fertilizer (2.33 €/kg N) consistently exceeded marginal revenue, meaning that the additional cost of applying 1 kg of N was not compensated by the value of the extra barley yield. This outcome reflects the poor and unrepresentative 2023 harvest and, more importantly, the nearly flat N response curve observed in field trials (Figure 8), making fertilization economically unjustifiable. For class ‘2’, yield initially declined with nitrogen application before recovering at higher rates (Figure 8), likely due to early drought stress, later better compensated by late rainfall in the more fertilized zones. Consequently, marginal returns were negative at low N rates but improved at higher dose rates (data used to construct Figure 9 can be found in Table A1 of the Appendix A). Despite the exceptional conditions of the 2022–2023 season, field characteristics suggest some potential for site-specific N management, with an advisable rate of about 90 kg N/ha for class ‘2’ and no fertilization for class ‘1’. These preliminary results highlight the need for further experimentation under contrasting climatic conditions, including refined N rates for variable-rate applications, while accounting for site-specific factors such as soil properties, water availability, topography, crop traits, and previous management practices [13,32,33].

5. Conclusions

Soil apparent electrical conductivity (ECa) and elevation, measured with a VERIS 3100 sensor, proved effective for delineating potential management zones, with two classes recommended as a practical starting point for adopting Precision Agriculture in rainfed cereals. Yield monitor data from combine harvesters are essential for interpreting field trials; original filtered yield monitor data should be used as the response variable in variance analysis rather than predicted yield values derived from interpolated raster maps. Experimental design must ensure sufficient observations across factor combinations (N rate and potential management class) to derive reliable N response curves and optimal rates, which should respect agronomic limits and be economically assessed using marginal revenue analysis. Under severe drought, N topdressing is counterproductive—at least at low rates—reducing barley yield in fertilized strips compared to unfertilized ones, while post-stress recovery was only partial and mainly evident at higher N rates. Given the atypical 2022–2023 season and the inherent climatic variability, site-specific N fertilization requires further evaluation within a multi-year framework to capture the effects of unpredictable weather conditions. By strengthening on-farm experimentation and economic modelling, this work contributes to the growing body of evidence supporting site-specific N management in rainfed cereal systems. It also aligns with the CAP’s objectives of promoting digitalization, environmental stewardship, and farmer-led innovation in nutrient management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A. and J.A.M.-C.; methodology, J.A. and J.A.M.-C.; software, J.A.; validation, J.A., A.E., L.S.-P. and J.A.M.-C.; formal analysis, J.A.; investigation, J.A. and J.A.M.-C.; resources, J.A.M.-C.; data curation, J.A. and J.A.M.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.A.; writing—review and editing, J.A., A.E., L.S.-P. and J.A.M.-C.; visualization, J.A. and J.A.M.-C.; supervision, J.A.; project administration, J.A. and J.A.M.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions, as they contain sensitive information about the participating farmer and the farm location.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bernat Colell Garcia for his technical support and for allowing the trial to be conducted on his farm located in Castellfollit de Riubregós (Catalonia, Spain).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PA | Precision Agriculture |

| N | Nitrogen |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| NUE | Nitrogen Use Efficiency |

| CAP | Common Agricultural Policy |

| NVZ | Nitrate Vulnerable Zone |

| VRN | Variable Rate Nitrogen |

| ECa | Apparent Electrical Conductivity |

| GNSS | Global Navigation Satellite System |

| WAAS | Wide Area Augmentation System |

| EGNOS | European Geostationary Navigation Overlay Service |

| SBAS | Satellite-Based Augmentation Systems |

| HSD | Honest Significant Difference |

| CV | Coefficient of Variation |

| PMC | Potential Management Class |

| GM | Gross Margin |

| MC | Marginal Cost |

| MR | Marginal Revenue |

Appendix A

Table A1 shows the calculated values of marginal production (MP) and marginal revenue (MR) required for applying Equation (6) to both classes ‘1’ and ‘2’ for Plot 2. Marginal productions were derived from the barley response curves (Section 4.1). Specifically, the equality to be verified is displayed in Equation (A1),

Table A1.

Analysis of marginal production (MP) and marginal revenue (MR) for different N fertilizer rates (Plot 2).

Table A1.

Analysis of marginal production (MP) and marginal revenue (MR) for different N fertilizer rates (Plot 2).

| N Fertilizer Rate (kg N/ha) | N Fertilizer Price (€/kg N) | Barley Grain Price (€/kg) | MP Class ‘1’ (kg Barley/kg N) | MR Class ‘1’ (€/kg N) | MP Class ‘2’ (kg Barley/kg N) | MR Class ‘2’ (€/kg N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2.33 | 0.218 | 4.531 | 0.988 | −17.961 | −3.916 |

| 8 | 2.33 | 0.218 | 3.639 | 0.793 | −15.472 | −3.373 |

| 16 | 2.33 | 0.218 | 2.747 | 0.599 | −12.983 | −2.830 |

| 24 | 2.33 | 0.218 | 1.854 | 0.404 | −10.494 | −2.288 |

| 32 | 2.33 | 0.218 | 0.962 | 0.210 | −8.005 | −1.745 |

| 40 | 2.33 | 0.218 | 0.070 | 0.015 | −5.516 | −1.202 |

| 48 | 2.33 | 0.218 | −0.822 | −0.179 | −3.026 | −0.660 |

| 56 | 2.33 | 0.218 | −1.714 | −0.374 | −0.537 | −0.117 |

| 64 | 2.33 | 0.218 | −2.606 | −0.568 | 1.952 | 0.425 |

| 72 | 2.33 | 0.218 | −3.498 | −0.763 | 4.441 | 0.968 |

| 80 | 2.33 | 0.218 | −4.391 | −0.957 | 6.930 | 1.511 |

| 88 | 2.33 | 0.218 | −5.283 | −1.152 | 9.419 | 2.053 |

| 96 | 2.33 | 0.218 | −6.175 | −1.346 | 11.908 | 2.596 |

References

- IRTAPubpro. Available online: https://repositori.irta.cat/handle/20.500.12327/2397 (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Sylvester-Bradley, R.; Kindred, D.R. Analysing nitrogen responses of cereals to prioritize routes to the improvement of nitrogen use efficiency. J. Exp. Bot. 2009, 60, 1939–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Videgain, M.; Martínez-Casasnovas, J.A.; Vigo-Morancho, A.; Vidal, M.; García-Ramos, F.J. On-farm experimentation of precision agriculture for differential seed and fertilizer management in semi-arid rainfed zones. Precis. Agric. 2024, 25, 3048–3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhulst, N.; François, I.; Grahmann, K.; Cox, R.; Govaerts, B. Eficiencia Del Uso de Nitrógeno Y Optimización de la Fertilización Nitrogenada en la Agricultura de Conservación; CIMMYT: Mexico City, Mexico, 2015; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Roel-Rezk, V.; Lundy, M.E.; Pittelkow, C.M. Assessing crop nitrogen status under organic amendments to reduce nitrogen fertilizer inputs and improve sustainability. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2025, 131, 365–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Liu, K.; Zhou, B.; Gao, H.; Han, X.; Liu, S.; Huang, S.; Zhang, A.; Hua, K.; et al. Minimizing the potential risk of soil nitrogen loss through optimal fertilization practices in intensive agroecosystems. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 45, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadras, V.O.; Richards, R.A. Improvement of crop yield in dry environments: Benchmarks, levels of organisation and the role of nitrogen. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 1981–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basso, B.; Ritchie, J.T. Simulating crop growth and biogeochemical fluxes in response to land management using the SALUS model. In The Ecology of Agricultural Landscapes: Long-Term Research on the Path to Sustainability; Hamilton, S.K., Doll, J.E., Robertson, G.P., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 252–274. [Google Scholar]

- Olšovská, K.; Sytar, O.; Kováčik, P. Optimizing Nitrogen Application for Enhanced Barley Resilience: A Comprehensive Study on Drought Stress and Nitrogen Supply for Sustainable Agriculture. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Menaie, H.; Al-Ragam, O.; Al-Shatti, A.; Al-Hadidi, M.A.; Babu, M.A. Optimizing Nitrogen Fertilization for Barley Crop at Full and Deficit Irrigation in the Arid Region. Indian J. Agric. Res. 2024, 58, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardehji, S.; Mahlooji, M.; Zare, S.; Kocak, M.Z.; Yıldırım, B. Comparative analysis of two-rowed and six-rowed barley genotypes: Impacts of water stress and nitrogen fertilizer on yield and stress responses. Cereal Res. Commun. 2025, 53, 597–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejnák, V.; Ernestová, Z. The Influence of Drought on the Utilisation of Nitrogen (15N) by Two Modern and One Historical Spring Barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) Varieties. Cereal Res. Commun. 2007, 35, 445–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammarano, D.; Holland, J.; Gianinetti, A.; Baronchelli, M.; Ronga, D. Impact of Nitrogen and Water on Barley Grain Yield and Malting Quality. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 24, 6718–6730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabra, D.; Reda, A.; El-Shawy, E.; El-Refaee, Y.; Abdelraouf, R. Improving Barley Production Under Deficient Irrigation Water and Mineral Fertilizers Conditions. SABRAO J. Breed. Genet. 2023, 55, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Casasnovas, J.A.; Arnó, J.; Escolà, A. Sensores de conductividad eléctrica aparente para el análisis de la variabilidad del suelo en Agricultura de Precisión. In Tecnología Hortícola Mediterránea; Namesny, A., Conesa, C., Martín Olmos, L., Papasseit, P., Eds.; SPE3 s.l.: Valencia, Spain, 2022; pp. 765–786. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, W.; Krienke, B.; Cao, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Cao, W.; Liu, X. In-season variable rate nitrogen recommendation for wheat precision production supported by fixed-wing UAV imagery. Precis. Agric. 2022, 23, 830–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsitouras, A.; Noulas, C.; Liakos, V.; Stamatiadis, S.; Tziouvalekas, M.; Qin, R.; Evangelou, E. Variable-Rate Nitrogen Application in Wheat Based on UAV-Derived Fertilizer Maps and Precision Agriculture Technologies. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.W.; Swinton, S.M.; Basso, B. Comparing profitability of variable rate nitrogen prescriptions. Precis. Agric. 2025, 26, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institut Cartogràfic i Geològic de Catalunya (ICGC). Geoíndex—Mapa Geològic de Catalunya 1:25.000. Available online: https://www.icgc.cat/ca/Eines-i-visors/Visors/Visualitzadors-Geoindex/Geoindex-Mapa-geologic-de-Catalunya-125000 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Institut Cartogràfic i Geològic de Catalunya (ICGC). Geoíndex—Sòls. Available online: https://www.icgc.cat/ca/Eines-i-visors/Visors/Visualitzadors-Geoindex/Geoindex-Sols (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Soil Survey Staff. Keys to Soil Taxonomy, 13th ed.; USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; p. 401.

- Martínez-Casasnovas, J.A.; Arnó, J. Sensors de sòl per optimitzar la zonificació del reg. In Agricultura de Precisió: Aplicacions al reg, Dossier Tècnic, 107; Romanyà Valls, S.A., Ed.; Departament d’Agricultura, Ramaderia, Pesca i Alimentació: Barcelona, Spain, 2020; pp. 32–36. [Google Scholar]

- Minasny, B.; McBratney, A.B.; Whelan, B.M. VESPER Version 1.62. Precision Agriculture Laboratory (PA Lab), The University of Sydney. 2005. Available online: https://precision-agriculture.sydney.edu.au/ (accessed on 16 January 2023).

- Bramley, R.G.V.; Song, X.; Colaço, A.F.; Evans, K.J.; Cook, S.E. Did someone say “farmer-centric”? Digital tools for spatially distributed on-farm experimentation. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 42, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, D. Regresión y Diseño de Experimentos; Alianza Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 2002; p. 744. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, E.D.; Colin, P.; Christy, D.; Drummond, P.E. Applying Soil Electrical Conductivity Technology to Precision Agriculture. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Precision Agriculture, St. Paul, MN, USA, 19–22 July 1998; Robert, P.C., Rust, R.H., Larson, W.E., Eds.; ASA, CSSA, and SSSA: Madison, WI, USA, 1999; pp. 1089–1100. [Google Scholar]

- IRTAPubpro. Available online: https://extensius.cat/2022/02/25/com-pot-afectar-la-sequera-al-cereal-dhivern/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Chen, J.; Lin, L.; Lü, G.; Wang, S. Effects of nitrogen fertilization on crop water stress index of summer maize in red soil. J. Plant Nutr. Fertil. 2010, 16, 1114–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Fu, W.; Guo, W.; Ren, N.; Zhao, Y.; Ye, Y. Efficient Physiological and Nutrient Use Efficiency Responses of Maize Leaves to Drought Stress under Different Field Nitrogen Conditions. Agronomy 2020, 10, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lara, A.; Mieno, T.; Luck, J.D.; Puntel, L.A. Predicting site-specific economic optimal nitrogen rate using machine learning methods and on-farm precision experimentation. Precis. Agric. 2023, 24, 1792–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, B.; Taylor, J. Precision Agriculture for Grain Production Systems; CSIRO Publishing: Collingwood, Australia, 2013; p. 199. [Google Scholar]

- Mittermayer, M.; Maidl, F.-X.; Donauer, J.; Kimmelmann, S.; Liebl, J.; Hülsbergen, K.-J. Optimizing Nitrogen Use Efficiency and Yield in Winter Barley: A Three-Year Study of Fertilization Systems in Southern Germany. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paccioretti, P.; Puntel, L.; Córdoba, M.; Mieno, T.; Ferguson, R.; Luck, J.; Thompson, L.; Balboa, G. Site-specific drivers of sensor-based nitrogen management in on-farm corn and wheat experiments. Front. Agron. 2025, 7, 1651522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).