Abstract

Sustainable recycling of organic residues and industrial byproducts is crucial for soil fertility and environmental sustainability. This study evaluated the effects of clinker-tea-waste compost (CTC) on rice growth, nutrient uptake, and soil chemical properties in a low-fertility paddy field over two years. In 2017, CTC was applied at 12, 18, and 22 Mg ha−1, while chemical fertilizer (CF) served as control. In 2018, all treatments received equal CF to assess residual effects. The results showed a limited immediate nitrogen supply in 2017, with no significant differences in rice growth, yield, or soil ammonium nitrogen (AN) among treatments. However, significant residual nitrogen effects emerged in 2018, with higher soil AN concentrations, nitrogen uptake indices, and rice yields in plots with higher CTC rates than in 2017. Si availability from clinker ash was evident immediately after application in 2017, correlating positively with rice stover Si content and CTC application rate. However, its residual effect disappeared in 2018 when CTC was discontinued. These findings demonstrate the complementary nutrient supply of CTC, with delayed nitrogen availability from tea residues and short-lived silicon release from clinker ash. This study highlights the potential of CTC for enhancing soil fertility and crop productivity in rice cultivation systems.

1. Introduction

Sustainable recycling of organic residues and industrial byproducts in agricultural systems is crucial for soil fertility enhancement and environmental sustainability [1,2]. Among organic materials, tea residue and spent coffee grounds from the beverage industry have attracted attention for nutrient recycling; however, their direct application is often limited because of their slow decomposition and potential phytotoxicity [3,4,5]. Tea residues contain nitrogen and bioactive polyphenols that decompose slowly, limiting immediate nutrient availability to crops [6,7,8]. Likewise, despite their nutrient-rich composition, spent coffee grounds require proper composting because of their high carbon-to-nitrogen C/N ratio and potential inhibitory effects [9,10,11].

Clinker ash, an industrial byproduct of coal combustion, is produced when boiler bottom ash undergoes high-temperature melting and rapid cooling, resulting in a hardened, silicate-rich material. It is widely used to supply plant-available silicon (Si), enhancing soil properties such as porosity, water retention, and pH buffering [12,13,14]. Silicon derived from industrial residues significantly benefits rice by enhancing its resistance to stress and pests and improving growth conditions, particularly in Si-deficient soils [15,16,17].

Recently, co-composting tea residues with clinker ash (Clinker-Tea-Waste Compost, CTC) has shown potential for improving compost maturity and nutrient retention and reducing nitrogen losses during composting [18]. This innovative combination combines slow-release nitrogen from tea residue with rapid-release Si from clinker ash, thereby offering distinct temporal benefits [2,19,20]. However, nitrogen in composted organic materials generally mineralizes slowly, contributing mainly to subsequent cropping seasons [21,22]. In contrast, Si availability from clinker ash and similar silicate materials is rapid but transient and often lacks residual effectiveness without repeated applications [13,23,24].

Industrial byproducts, such as clinker and fly ash, require careful management to avoid heavy metal accumulation and microbial disruption [23,24]. Thus, evaluating the nutrient dynamics, residual effects, and practical agricultural implications of CTC is essential for validating its potential as a sustainable amendment for rice production systems [25]. Despite the known benefits of tea residue and clinker ash, there is limited research on their combined effects as CTC in rice cultivation, particularly in terms of nutrient dynamics and residual effects.

Low-fertility paddy soils pose significant challenges for rice cultivation, as they often exhibit low organic matter content, limited nitrogen availability, and insufficient plant-available silicon, all of which restrict early growth and reduce yield potential. In particular, sandy or degraded paddy soils with low cation exchange capacity (CEC) have difficulty retaining nutrients, resulting in rapid leaching losses and poor synchronization between nutrient supply and crop demand. These constraints highlight the need for amendments capable of providing sustained nutrient availability in order to support stable rice production. CTC, integrating slow-release nitrogen from tea waste and readily available silicon from clinker ash, has the potential to address these critical nutrient limitations in low-fertility paddy systems.

This study evaluated the effects of CTC on rice growth, nutrient uptake, and soil properties in low-fertility paddy fields to highlight its potential as a sustainable soil amendment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site and Test Materials

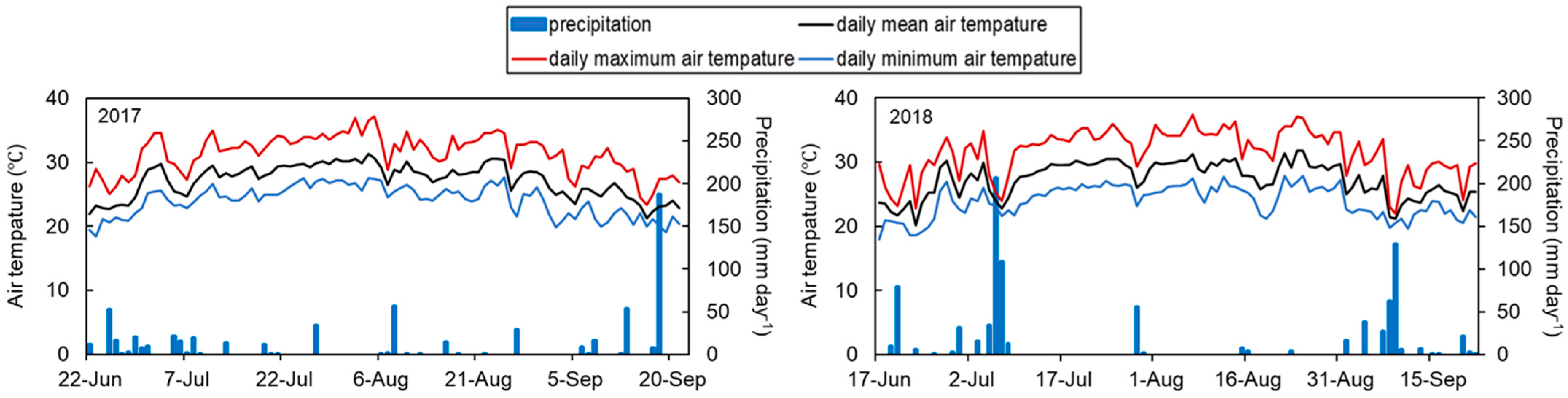

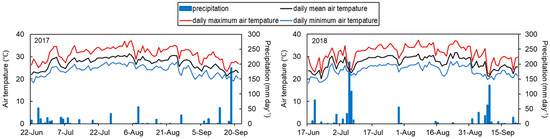

This study was conducted at Ehime University Farm (33°57.60′ N, 132°47.51′ E) from 4 June to 21 September 2017, and 4 June to 23 September 2018. Rice (Oryza sativa L. var. Koshihikari) was used as the test variety because it is the most widely cultivated cultivar in Japan and is well adapted to regional climatic and soil conditions. Its broad cultivation suitability makes it an appropriate standard variety for evaluating fertilizer and soil amendment effects under typical paddy management practices. According to Soil Taxonomy (2nd edition, 1999) [26], the soil was classified as Typic Dystropepts. The topsoil texture was sandy loam. Carbon (C) and nitrogen (N) contents and C/N ratio were 16.0 g kg−1, 1.59 g kg−1, and 10.1, respectively. The soil availability of soluble phosphoric acid (P2O5) and silicic acid (SiO2) was 263 and 50 mg kg−1, respectively, and the cation exchange capacity was 11.3 cmolc kg−1. The physicochemical properties of the soils are listed in Table 1. Table 2 shows the physicochemical properties of the CTC used as test material. Compost was provided by West Japan Crush Stone. The field was puddled and leveled before transplanting, following standard local cultivation practices. Puddling was performed on 20 June 2017, and 15 June 2018, respectively. Irrigation was managed under conventional flooded paddy conditions, maintaining continuous submergence from transplanting until the mid-season drainage period. Mid-season drainage was carried out from 21 July to 27 July 2017, and from 25 July to 28 July 2018, after which the field was re-flooded. Other crop management practices, including weeding and pest control, followed regional guidelines to avoid introducing confounding factors affecting nutrient dynamics or crop growth. The average temperature and precipitation during the rice growing period (22 June to 21 September 2017, and 17 June to 23 September 2018) are shown in Figure 1, based on records from Matsuyama District Meteorological Observatory of the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) (33°50.6′ N, 132°46.6′ E; 32.2 m above sea level), which is located approximately 13 km from the experimental site. The average temperatures were similar in both years; however, the precipitation was higher in July and August 2018.

Table 1.

Soil physicochemical properties.

Table 2.

CTC physicochemical properties.

Figure 1.

Air temperature and precipitation during the rice cultivation period.

2.2. Treatments and Fertilizer Management

The study was conducted using four test plots. The four treatment areas consisted of a chemical fertilizer (CF) zone and three different levels of CTC application: 12 Mg ha−1 (CTC12), 18 Mg ha−1 (CTC18), and 22 Mg ha−1 (CTC22).

In 2017, the CF was applied using a chemical fertilizer containing 14% N (3.4% NH4-N), 10% P2O5 (4.2% water-soluble P2O5), and 10% K2O (Asahi Fertilizer Co., Ltd., Kagawa, Japan). CTC was provided by Nishinihon Saiseki Co., Ltd. (Ehime, Japan). P2O5 and K2O in the CTC application area were supplemented with 0-30-0 fertilizer (containing 30% P2O5, of which 5% was water-soluble P2O5, 8% MgO, 1% Mn, 0.5% B; Jcam Agri Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and 0-0-60 fertilizer (containing 60% K2O; ZEN-NOH, Tokyo, Japan) to achieve the same amount of fertilizer as in the CF application area. N application rates were 80 kg ha−1 for CF, 70 kg ha−1 for CTC12, 105 kg ha−1 for CTC18, and 130 kg ha−1 for CTC22.

In 2018, all treatments received chemical fertilizer containing 14% N (of which 5.5% was NH4-N), 14% P2O5 (of which 9.0% was water-soluble P2O5), and 14% K2O at 52 kg ha−1 of each nutrient. The treatment areas were arranged using a completely random clumping method with four replicates per treatment; each plot was 14.4 m2 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Amount of fertilizer applied in each treatment.

2.3. Rice Growth and Yield Surveys

In both the 2017 and 2018 trials, four paddy rice plants from each treatment were selected every two weeks from transplantation to harvest, and grass height, stem number, and leaf color values were measured. Grass height was measured from the ground surface to the highest leaf height using a folding scale. The number of stems was defined as the number of shoots, including invalid shoots. Leaf color was measured using a chlorophyll meter (SPAD-502, Soil–Plant Analysis Development, SPAD KONICA MINOLTA Sensing, Osaka, Japan).

For the yield survey, four replicates of paddy rice in each treatment were harvested from the ground by tsubo-mowing (3 × 3 plants) for a total of nine plants and dried in a glass room of the Faculty of Agriculture, Ehime University, for approximately two weeks. The number of ears was then counted, and the above-ground dry weight was weighed. The paddy was then weighed, and the aboveground dry weight was subtracted to calculate the straw weight (Figure 2). Hulling was performed using a hulling machine in a glass room at Ehime University, Japan. The number of ears, aboveground dry weight, number of hulled grains per ear, total hulled rice weight, coarse and polished brown rice weight, and thousand grain weight of the brown rice were measured. Five ears were randomly selected from the paddy rice in each treatment, and the number of hulled grains was calculated by manually threshing the ears, counting the number of hulled grains, and dividing the number of grains by five. The weight of coarse brown rice was measured after hulling, and the weight of polished brown rice was calculated by passing the coarse brown rice through a 1.85 mm sieve and measuring the weight of the brown rice remaining on the sieve. For brown rice thousand-grain weight, the number of thousand grains were weighed after measuring the number of grains using a grain discriminator (RQGI 10A) manufactured by Satake Co.

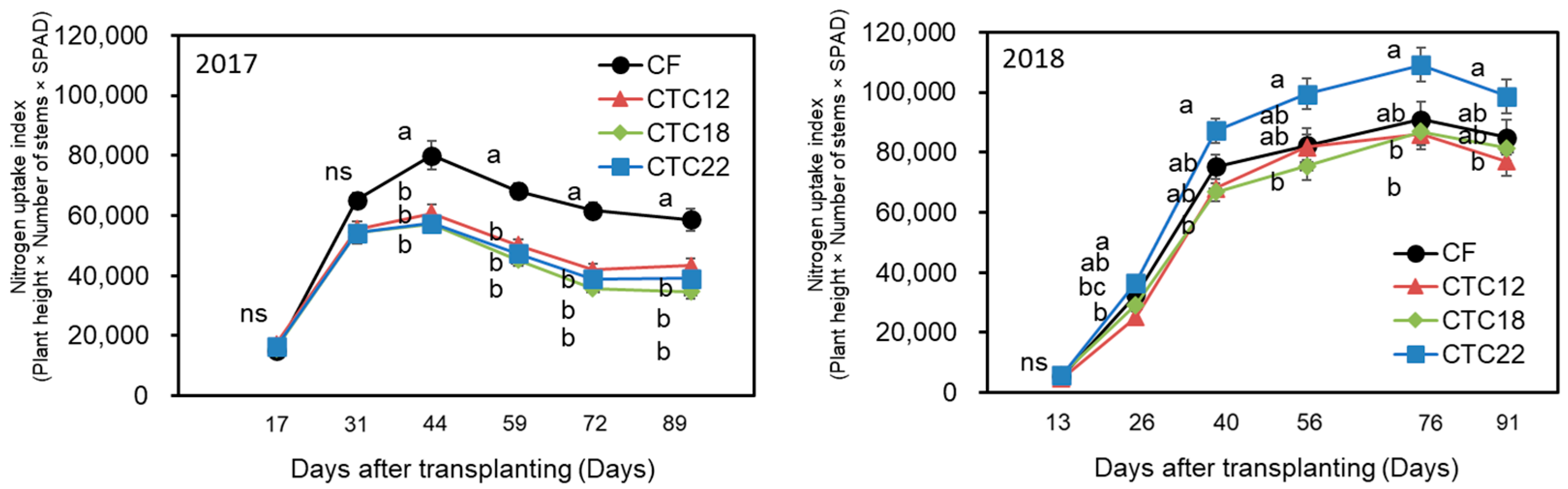

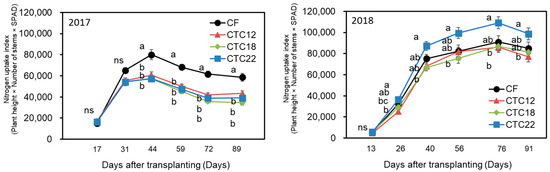

Figure 2.

Nitrogen uptake index of rice plants during the growing season (2017, 2018). Nitrogen uptake index was calculated as plant height (cm) × number of stems (stems plant−1) × SPAD value (n = 16). CF, chemical fertilizer; CTC12, CTC applied at 12 Mg ha−1; CTC18, CTC applied at 18 Mg ha−1; CTC22, CTC applied at 22 Mg ha−1. Error bars indicate standard error, while different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) according to Tukey’s test.

2.4. Measurement of Si Content in Rice and Soil Chemical Properties

Four rice plants were harvested from the ground at the ear emergence stage and dried in a dryer at 70 °C for 48 h, after which the dried weight was measured and crushed using a high-speed vibrating sample grinder. Silicon (Si) content was determined using a conventional gravimetric method widely employed for plant Si analysis. Briefly, the ground samples were wet-digested with sulfuric acid and hydrogen peroxide, and the digest was filtered through No. 6 quantitative filter paper. The residue retained on the filter was transferred to a pre-weighed crucible, ignited in a muffle furnace at 550 °C for 5 h, and the ash weight was used to quantify crude Si content.

To determine soil chemical properties during the growth study, soil samples were collected once every two weeks. Sampling was conducted at four uniformly distributed locations within each treatment plot, avoiding edge areas, from a depth of 0–10 cm using a 50 mL syringe with the end cut off. The four subsamples were combined to obtain a representative composite sample for each plot. AN was extracted using a standard 2 M potassium chloride (KCl) extraction method widely employed for soil inorganic nitrogen analysis. Soil samples were mixed with 2 M KCl at a soil:solution ratio of 1:10 and shaken at 180 rpm for 1 h. The slurry was then filtered through No. 2 qualitative filter paper (Toyo Roshi Kaisha, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) to obtain the extract. Ammonium concentration in the extract was measured at a wavelength of 630 nm using a spectrophotometer (Ultraviolet and Visible Spectrophotometer V-630, JASCO Co., Tokyo, Japan) based on the indophenol blue colorimetric method, which is a conventional procedure for determining AN in soil extracts.

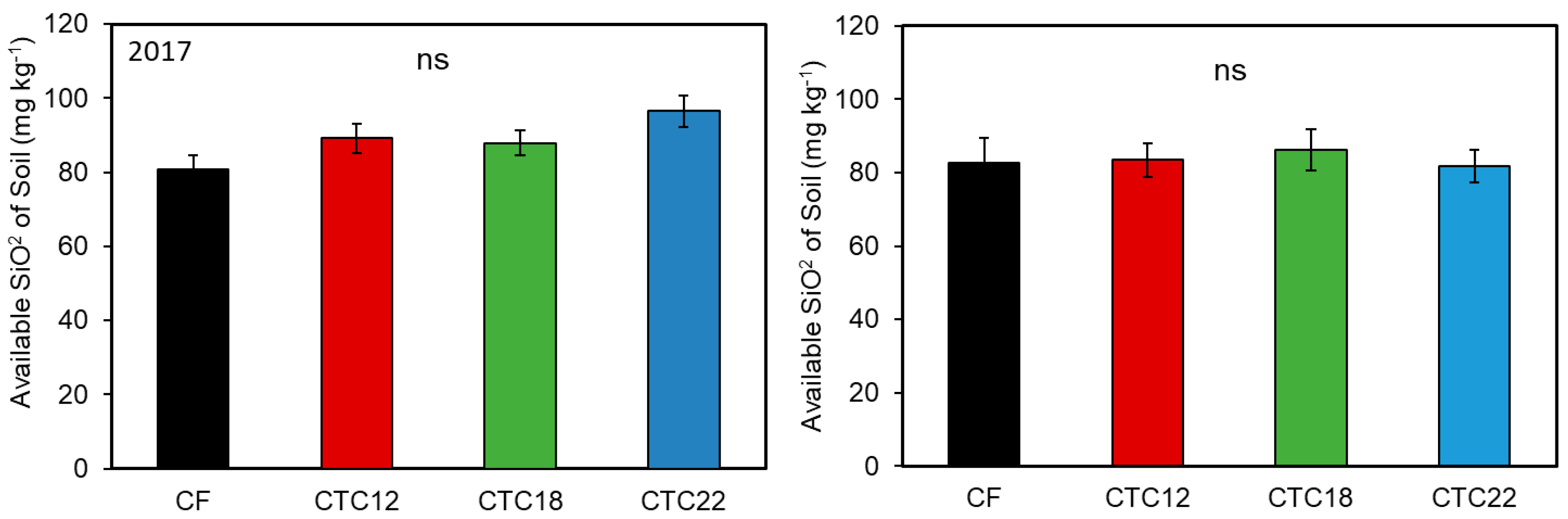

The moisture content was determined from the weight ratio before and after drying by drying approximately 5 g of soil in a dryer at 105 °C for 72 h. Available SiO2 content in the soil was determined at the end of the cultivation period in 2017 and 2018 using a standard molybdenum blue colorimetric method widely employed for soil available silicon analysis. After sampling, the collected soil was air-dried for 48 h and sieved through a 2 mm mesh. The air-dried fine soil was then extracted in a pH 6.2 phosphate-buffered solution under waterlogged conditions at 40 °C for 24 h, following conventional procedures for releasing plant-available silicate. The extract was subsequently filtered and analyzed spectrophotometrically at 810 nm using the molybdenum blue reaction to quantify available SiO2.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the Statcel5 add-in software for Excel. Comparisons between treatments for rice growth, yield, Si content, and soil chemical properties were performed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post hoc tests (Tukey’s method) at a 5% level of significance.

3. Results

3.1. Nitrogen Uptake Index and Rice Yield

Nitrogen uptake indices during the 2017 and 2018 growing seasons are shown in Figure 2. In 2017, there were no significant differences among the treatments in which CTC was applied throughout the growing season. The treatment where compost was applied starting 44 d after planting remained significantly lower than CF. In 2018, when compost was stopped and the same amount of chemical fertilizer was applied to all treatments, CTC22 tended to be higher than the other treatments starting 40 d after planting. The nitrogen uptake index also tended to be higher in the treatments with the highest amount of compost applied in 2017 at 26, 76, and 91 d after planting.

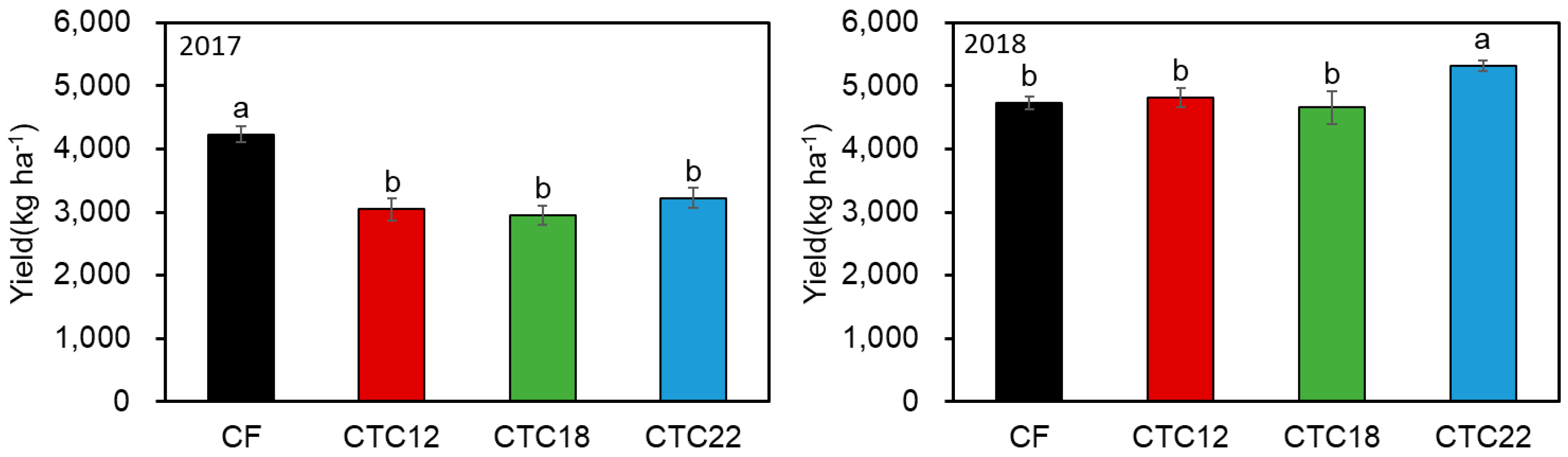

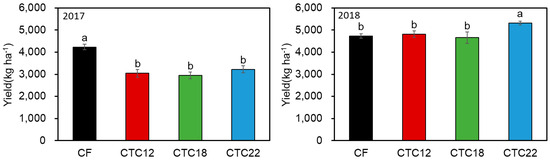

The yields in 2017 and 2018 are shown in Figure 2, and the yield components in Table 1 were significantly higher in 2017 than in CF in both compost-applied treatments. The number of ears was significantly lower in the yield component; in 2018, CTC22 was significantly higher than in the other treatments. The number of ears was significantly higher in the yield components; CTC12 and 18 had similar yields to CF. The 2018 yields in each treatment were generally higher than those in 2017. The rice yields for 2017 and 2018 are shown in Figure 3. In 2017, the grain yield in the compost-applied treatments was significantly lower than that in the CF treatment. In contrast, in 2018, the yield in the CTC22 treatment was significantly higher than in the other treatments, while the yields in CTC12 and CTC18 were comparable to that of the CF treatment.

Figure 3.

Rice yield (2017, 2018) (n = 16). CF, chemical fertilizer; CTC12, CTC applied at 12 Mg ha−1; CTC18, CTC applied at 18 Mg ha−1; CTC22, CTC applied at 22 Mg ha−1. Error bars indicate standard error, while different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) according to Tukey’s test.

3.2. Soil Chemical Properties

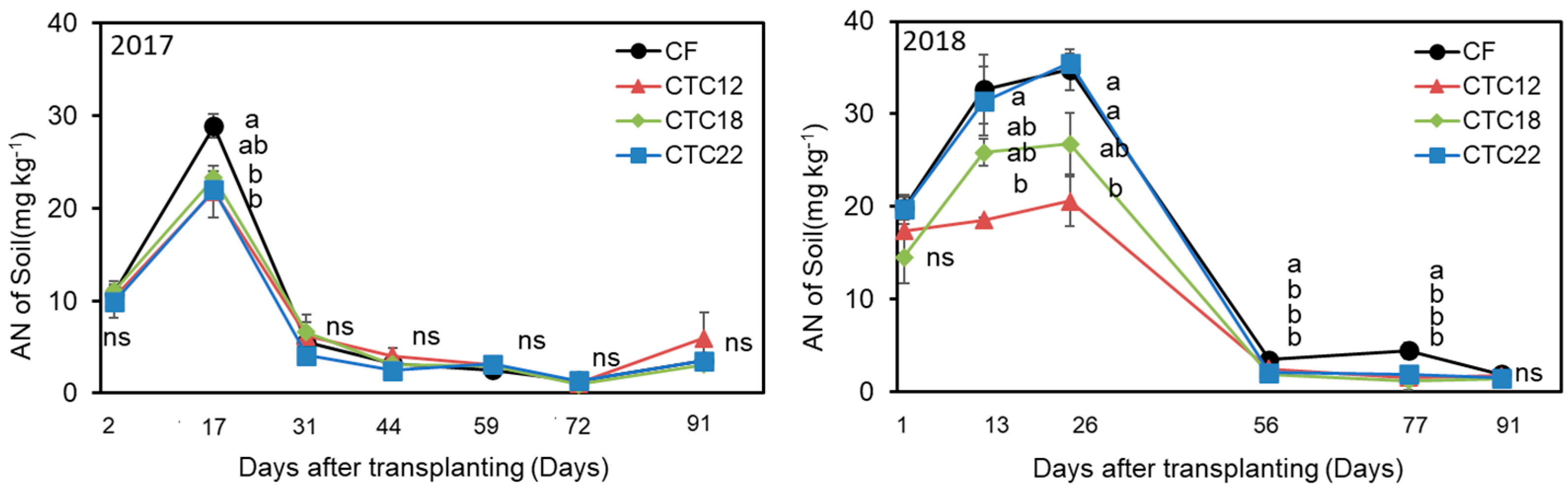

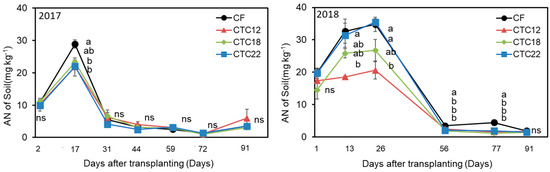

The soil ammonia nitrogen content during the 2017 and 2018 growing seasons is shown in Figure 4. In 2017, the compost-applied treatment was lower than CF at 17 d after planting, and the ammonia nitrogen content for the entire treatment dropped after 29 d of planting and 7 d of drying. In 2018, CTC22 was similar to that of CF until 26 d after planting. In 2018, CTC22 was similar to CF until 26 d after planting, and CTC22 was the highest and CTC12 was the lowest at 13 and 26 d, respectively, after planting in the CTC-applied treatments. The ammonia nitrogen content of all treatments decreased after 4 d of drying from 38 d after planting.

Figure 4.

Ammonia nitrogen content in soil during the growing season (2017, 2018) (n = 4). CF, chemical fertilizer; CTC12, CTC applied at 12 Mg ha−1; CTC18, CTC applied at 18 Mg ha−1; CTC22, CTC applied at 22 Mg ha−1. Error bars indicate standard error, while different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) according to Tukey’s test.

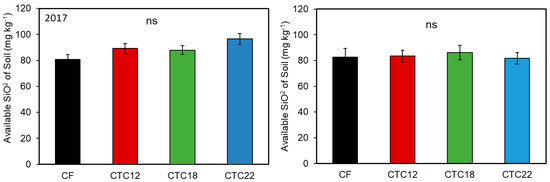

Figure 5 shows the post-cultivation soil soluble silicate content in 2017 and 2018. In 2017, the composted treatments tended to have a higher silicate content than in CF. In 2018, there were no differences among treatments.

Figure 5.

Available SiO2 in the soil after the end of rice cultivation (2017, 2018) (n = 4). CF, chemical fertilizer; CTC12, CTC applied at 12 Mg ha−1; CTC18, CTC applied at 18 Mg ha−1; CTC22, CTC applied at 22 Mg ha−1. Error bars indicate standard error, while different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) according to Tukey’s test.

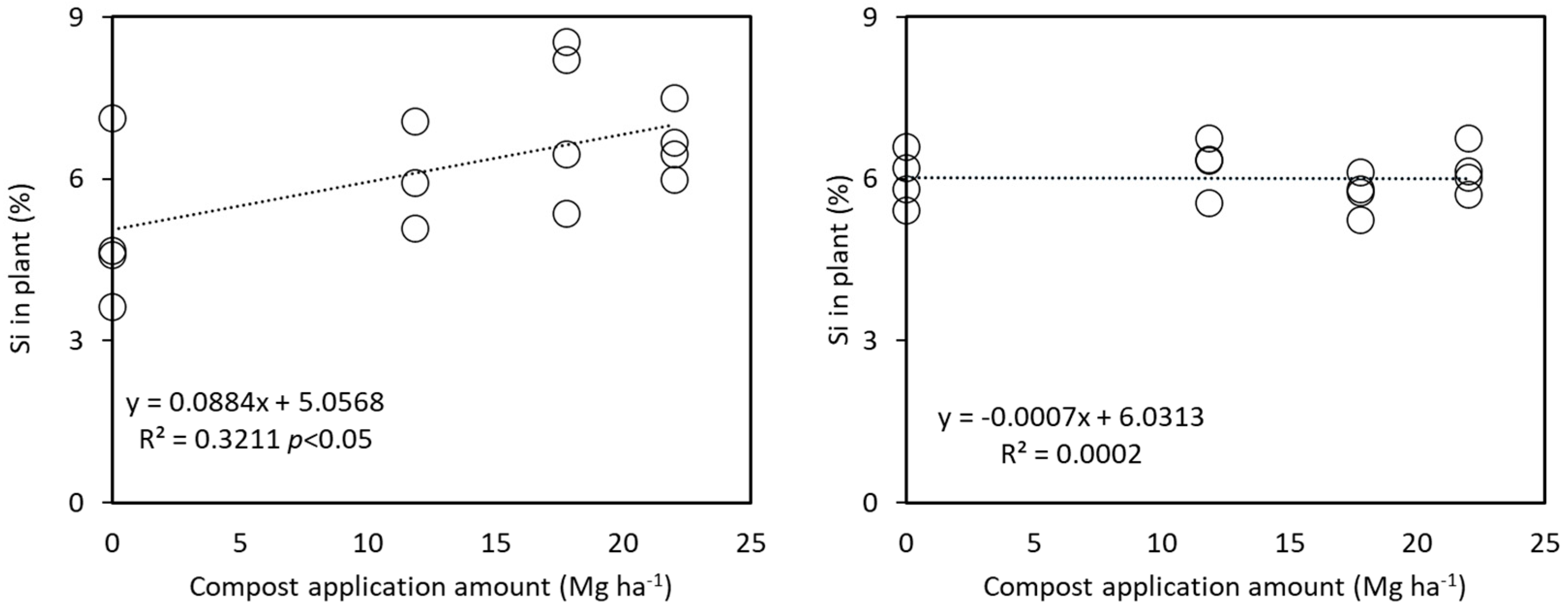

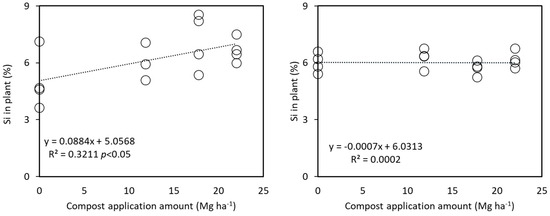

3.3. Relationship Between Compost Application Rate and Si Content in Rice

The relationship between compost application rate and Si content in rice plants in 2017 and 2018 is shown in Figure 6 (in 2018, the 2017 compost application rate was used.) In 2017, a positive correlation was observed between the Si content in paddy rice stover and the compost application rate. However, in 2018, no correlation was found between the amount of compost applied in 2017 and the Si content of the paddy rice stover.

Figure 6.

Correlation between compost application amount and Si in rice plants (2017, 2018) (n = 16). CF, chemical fertilizer; CTC12, CTC applied at 12 Mg ha−1; CTC18, CTC applied at 18 Mg ha−1; CTC22, CTC applied at 22 Mg ha−1. R2 indicates the coefficient of determination.

4. Discussion

4.1. CTC Application and Residual Effect on the Next Crop (N)

In 2017, our results indicated a limited immediate nitrogen supply from the CTC, because increased compost application did not significantly affect rice growth, yield, or soil ammonium nitrogen content. These findings align with those of Nille et al. (2021) [3] and Zaine et al. (2021) [6], where tea-waste-derived nitrogen predominantly exists in organic forms that are resistant to rapid mineralization, resulting in slow nutrient availability. Moreover, Bomfim et al. (2021) [5] reported similar delayed nitrogen release patterns in composted coffee grounds, confirming slow decomposition due to stable organic compounds and limited immediate nitrogen effectiveness.

However, significant residual nitrogen effects were observed in 2018. Soil ammonium-nitrogen concentrations, nitrogen uptake indices, and rice yields notably increased in plots that received higher compost application rates than those in the previous year (CTC22). These results corroborate the findings of previous studies [21,28] in which composted organic residues exhibited substantially delayed nitrogen mineralization, enhancing soil fertility and crop productivity in subsequent cropping seasons. Additionally, Myint et al. (2010) [29] demonstrated improved nitrogen availability over extended periods through integrated organic–inorganic fertilizer management, supporting our observation of prolonged nitrogen release from tea compost.

Furthermore, the incorporation of clinker ash into CTC may indirectly facilitate nitrogen retention and availability. The authors of [12,30] improved soil structure, enhanced nutrient adsorption capacity, and increased microbial activity, potentially reducing nitrogen loss and synchronizing nutrient availability with crop demand. Such soil improvements are likely contributors to the significant effects of residual nitrogen observed in our study.

Thus, our results demonstrate that nitrogen derived from tea residues within CTC serves primarily as a slow-release nutrient source, offering significant residual benefits owing to gradual mineralization. The complementary role of clinker ash further reinforced nitrogen availability, suggesting the efficacy of CTC in sustainable nitrogen management for rice cultivation.

4.2. CTC Application and Residual Effect on the Next Crop (Si)

In contrast to nitrogen, Si availability from clinker ash was evident immediately upon application. In 2017, a positive correlation (r = 0.32) between rice stover Si content and compost application rate indicated effective plant-available Si provision from clinker ash. Similar rapid Si release and plant uptake effects were confirmed by [15,16], who demonstrated that slag- and clinker-derived Si amendments provided rapid but short-lived Si availability to crops.

However, the residual Si effect disappeared in 2018 when compost application was discontinued. No significant correlation was found between previous compost application and the silicon content in rice stover or soil-available silicon levels. These findings suggest that rapid Si uptake or leaching occurred within the first cropping year, limiting the residual availability. Yao et al. (2015) and Nayak et al. (2015) [13,24] reported similar observations with fly ash-derived Si amendments, showing rapid initial Si release but limited residual effectiveness without repeated applications.

The limited persistence of silicon from clinker ash observed in our study aligns closely with findings from previous studies [14,23], which emphasized that industrial silicate materials typically provide silicon rapidly, but require regular applications to sustain soil availability. Thus, our findings underscore the necessity of periodic Si amendments to maintain the soil Si status in paddy systems.

4.3. Practical Implications

This study highlights the practical advantages of integrating tea residue with clinker ash via CTC. Morita et al. (2024) [18] showed that clinker accelerated compost maturation, reduced nutrient loss, and significantly enhanced compost quality and safety within a short composting period. These beneficial effects closely match our findings, indicating a clear complementary nutrient supply: delayed nitrogen availability and immediate Si release.

Additionally, clinker ash significantly improves soil structure and nutrient retention properties, including ammonium adsorption capacity, indirectly benefiting soil fertility and plant growth. Similar soil improvements were observed by [30,31], who reported enhanced porosity, water retention, and nutrient adsorption capabilities resulting from the incorporation of clinker ash.

However, the careful management of clinker ash and other industrial residues is necessary to avoid heavy metal contamination and potential microbial inhibition. Singh et al. (2016) and Thanarasu et al. (2015) [23,24] demonstrated that excessive fly ash application can lead to significant heavy metal accumulation and adverse effects on soil microorganisms, emphasizing the importance of cautious application rates.

The benefits of composted agricultural residues extend beyond nitrogen and Si nutrition. Studies on coffee ground composting [5,10] have confirmed the importance of proper composting techniques in minimizing phytotoxicity and maximizing soil fertility and crop productivity. Biochar derived from agricultural residues, as described previously [25] and [32], also enhanced soil nutrient retention and crop yield, reinforcing the potential for integrated waste-derived soil amendments.

Therefore, CTC exemplifies a sustainable and practical approach to circular agriculture. The integration of slow-release nitrogen and immediate Si provision, combined with soil structural improvements, makes it a valuable agricultural input for sustainable crop production systems.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that Clinker-Tea Compost (CTC), produced by combining tea residues with clinker ash, provides a unique and complementary nutrient supply pattern that benefits rice production. Nitrogen derived from tea residues exhibited limited immediate availability during the year of application, largely due to its stable organic composition. However, substantial residual nitrogen effects were observed in the subsequent season, as gradual mineralization during the fallow period enhanced soil ammonium levels, nitrogen uptake, and rice yield in the second year. These results highlight the potential of tea-based composts as slow-release nitrogen sources capable of contributing to long-term soil fertility.

In contrast, silicon from clinker ash acted as a fast-release nutrient. A significant increase in silicon uptake by rice plants was detected in the application year, confirming efficient release of plant-available silicon from clinker. Nevertheless, this effect did not persist into the following season, suggesting rapid uptake or leaching of silicon under paddy conditions and the need for repeated supplementation to maintain sufficient soil silicon levels. At the same time, careful management of industrial by-products such as clinker is required to prevent potential risks associated with heavy metals or excessive application.

Overall, CTC represents a promising amendment that aligns with the principles of circular agriculture by effectively recycling organic and industrial residues. Its dual action-slow-release nitrogen and fast-release silicon provides both immediate and long-term agronomic advantages. These findings support the incorporation of CTC into sustainable nutrient management strategies, particularly in rice-based systems where both nitrogen and silicon play essential roles in productivity and resilience.

Based on these findings, CTC can be recommended as a viable amendment for improving nutrient dynamics in low-fertility paddy soils, especially where both nitrogen deficiency and silicon scarcity limit crop performance. To enhance its practical application, future studies should refine optimal CTC application rates, investigate its cumulative multi-year effects on soil chemical properties, and assess environmental safety, including potential risks associated with industrial by-products. Expanding such evaluations will help establish evidence-based guidelines for the wider adoption of CTC in sustainable rice production systems.

Author Contributions

All the authors conceived and designed the experiments; W.S., N.M., Y.T. and H.U. performed the experiments and analyzed the data; all authors contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools and wrote the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was partly supported by Nishinihon Saiseki Co., Ltd., Japan.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Nishinihon Saiseki Co., Ltd. for providing the clinker-tea-waste compost for this study and Yoichi Yamashita, Masataka Adachi, and Keiji Ishikake at the University Farm, Faculty of Agriculture, Ehime University for their technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Martínez-Blanco, J.; Lazcano, C.; Christensen, T.H.; Muñoz, P.; Rieradevall, J.; Møller, J.; Antón, A.; Boldrin, A. Compost benefits for agriculture evaluated by life cycle assessment. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 33, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, K.W.; Chia, S.R.; Yen, H.-W.; Nomanbhay, S.; Ho, Y.-C.; Show, P.L. Transformation of biomass waste into sustainable organic fertilizers. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nille, O.S.; Patil, A.S.; Waghmare, R.D.; Naik, V.M.; Gunjal, D.B.; Kolekar, G.B.; Gore, A.H. Valorization of Tea Waste for Multifaceted Applications: A Step Toward Green and Sustainable Development. In Valorization of Agri-Food Wastes and By-Products; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 219–236. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, S.; Wei, Y.; Chen, J.; Wei, X. Extraction methods, physiological activities and high value applications of tea residue and its active components: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 12150–12168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomfim, A.S.C.d.; de Oliveira, D.M.; Walling, E.; Babin, A.; Hersant, G.; Vaneeckhaute, C.; Dumont, M.-J.; Rodrigue, D. Spent Coffee Grounds Characterization and Reuse in Composting and Soil Amendment. Waste 2023, 1, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaine, M.Z.; Shah, M.N.A.; Juan, D. Performance study of tea waste as nutrient rich organic fertilisers. Borneo Eng. Adv. Multidiscip. 2023, 2, 116–121. [Google Scholar]

- Anand, J.; Rawat, S.; Teshwar, S.; Gupta, S.; Sahil, M.; Rai, N. Impact of green tea compost on soil quality and growth of plants. Ecol. Environ. Conserv. 2020, 26, S103–S108. [Google Scholar]

- Tarashkar, M.; Matloobi, M.; Qureshi, S.; Rahimi, A. Assessing the growth-stimulating effect of tea waste compost in urban agriculture while identifying the benefits of household waste carbon dioxide. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 151, 110292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horgan, F.G.; Floyd, D.; Mundaca, E.A.; Crisol-Martínez, E. Spent coffee grounds applied as a top-dressing or incorporated into the soil can improve plant growth while reducing slug herbivory. Agriculture 2023, 13, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Burillo, S.; Cervera-Mata, A.; Fernández-Arteaga, A.; Pastoriza, S.; Rufián-Henares, J.Á.; Delgado, G. Why should we be concerned with the use of spent coffee grounds as an organic amendment of soils? A narrative review. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhanarajan, A.-E.; Han, Y.-H.; Koh, S.-C. The efficacy of functional composts manufactured using spent coffee ground, rice bran, biochar, and functional microorganisms. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, A.A.; Muhambi, M.; Tsubo, M.; Sato, K.; Nishihara, E. Utilisation of coal clinker ash in transforming the carbon content of sandy soil. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.T.; Ji, X.S.; Sarker, P.K.; Tang, J.H.; Ge, L.Q.; Xia, M.S.; Xi, Y.Q. A comprehensive review on the applications of coal fly ash. Earth Sci. Rev. 2015, 141, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Goyal, D. Mineralogical studies of coal fly ash for soil application in agriculture. Part. Sci. Technol. 2015, 33, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, J.; Nguyen, T.B.T.; Honeyands, T.; Monaghan, B.; O’Dea, D.; Rinklebe, J.; Vinu, A.; Hoang, S.A.; Singh, G.; Kirkham, M.B.; et al. Production, characterisation, utilisation, and beneficial soil application of steel slag: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 419, 126478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Kang, Y.-G.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kim, J.-H.; Choi, J.-W.; Oh, T.-K. Influences of silicate fertilizers containing different rates of iron slag on CH4 emission and rice (Oryza sativa L.) growth. Korean J. Agric. Sci. 2024, 51, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munda, S.; Nayak, A.K.; Mishra, P.N.; Bhattacharyya, P.; Mohanty, S.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, U.; Baig, M.J.; Tripathi, R.; Shahid, M.; et al. Combined application of rice husk biochar and fly ash improved the yield of lowland rice. Soil Res. 2016, 54, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, N.; Toma, Y.; Ueno, H. Acceleration of composting by addition of clinker to tea leaf compost. Waste 2024, 2, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Li, J.; Meng, Q.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y. Enhanced adsorption capacity of sulfadiazine on tea waste biochar from aqueous solutions by the two-step sintering method without corrosive activator. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 104898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.; Wang, P.; Vigneshwaran, S.; Chen, Z. Resource Utilization of Tea Waste in Biochar Production and Other Applications 2025, 101042p.

- Jahangir, M.M.R.; Islam, S.; Nitu, T.T.; Uddin, S.; Kabir, A.K.M.A.; Meah, M.B.; Islam, R. Bio-compost-based integrated soil fertility management improves post-harvest soil structural and elemental quality in a two-year conservation agriculture practice. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diacono, M.; Montemurro, F. Long-term effects of organic amendments on soil fertility. In Sustainable Agriculture Volume 2; Lichtfouse, E., Hamelin, M., Navarrete, M., Debaeke, P., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 761–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.K.; Tripathi, P.; Dwivedi, S.; Awasthi, S.; Shri, M.; Chakrabarty, D.; Tripathi, R.D. Fly-ash augmented soil enhances heavy metal accumulation and phytotoxicity in rice (Oryza sativa L.); A concern for fly-ash amendments in agriculture sector. Plant Growth Regul. 2016, 78, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, A.K.; Raja, R.; Rao, K.S.; Shukla, A.K.; Mohanty, S.; Shahid, M.; Tripathi, R.; Panda, B.B.; Bhattacharyya, P.; Kumar, A.; et al. Effect of fly ash application on soil microbial response and heavy metal accumulation in soil and rice plant. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2015, 114, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thanarasu, A.; Periyasamy, K.; Devaraj, K.; Periyaraman, P.; Palaniyandi, S.; Subramanian, S. Tea powder waste as a potential co-substrate for enhancing the methane production in anaerobic digestion of carbon-rich organic waste. J. Cleaner Prod. 2018, 199, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soil Survey Staff. Soil Taxonomy: A Basic System of Soil Classification for Making and Interpreting Soil Surveys, 2nd ed.; USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service: Washington, DC, USA, 1999.

- IUSS Working Group WRB. World Reference Base for Soil Resources 2014, Update 2015: International Soil Classification System for Naming Soils and Creating Legends for Soil Maps; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.H.; Park, C.Y.; Jung, K.Y.; Kang, S.S. Long-term effects of inorganic fertilizer and compost application on rice sustainability in paddy soil. Korean J. Soil Sci. Fertil. 2013, 46, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Myint, A.K.; Yamakawa, T.; Kajihara, Y.; Zenmyo, T. Application of different organic and mineral fertilizers on the growth, yield and nutrient accumulation of rice in a Japanese ordinary paddy field. Sci. World J. 2010, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, A.A.; Abebe, M.G.; Manneh, E.; Tsubo, M.; Sato, K.; Nishihara, E. Coal clinker ash influence in mineral nitrogen sorption and leaching in sandy soil. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.M.; Li, Z.; Wang, L. Utilization of Fly Ash in Agriculture: A Comprehensive review 2021. Unpublished manuscript. 124542p.

- Fan, S.; Tang, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, H.; Tang, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, X. Biochar prepared from co-pyrolysis of municipal sewage sludge and tea waste for the adsorption of methylene blue from aqueous solutions: Kinetics, isotherm, thermodynamic and mechanism. J. Mol. Liq. 2016, 220, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).