Preliminary Evaluation of Sustainable Treatment of Landfill Leachate Using Phosphate Washing Sludge for Green Spaces Irrigation and Nitrogen Recovery

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials: Characterization of Phosphate-Washing Sludge and Leachate

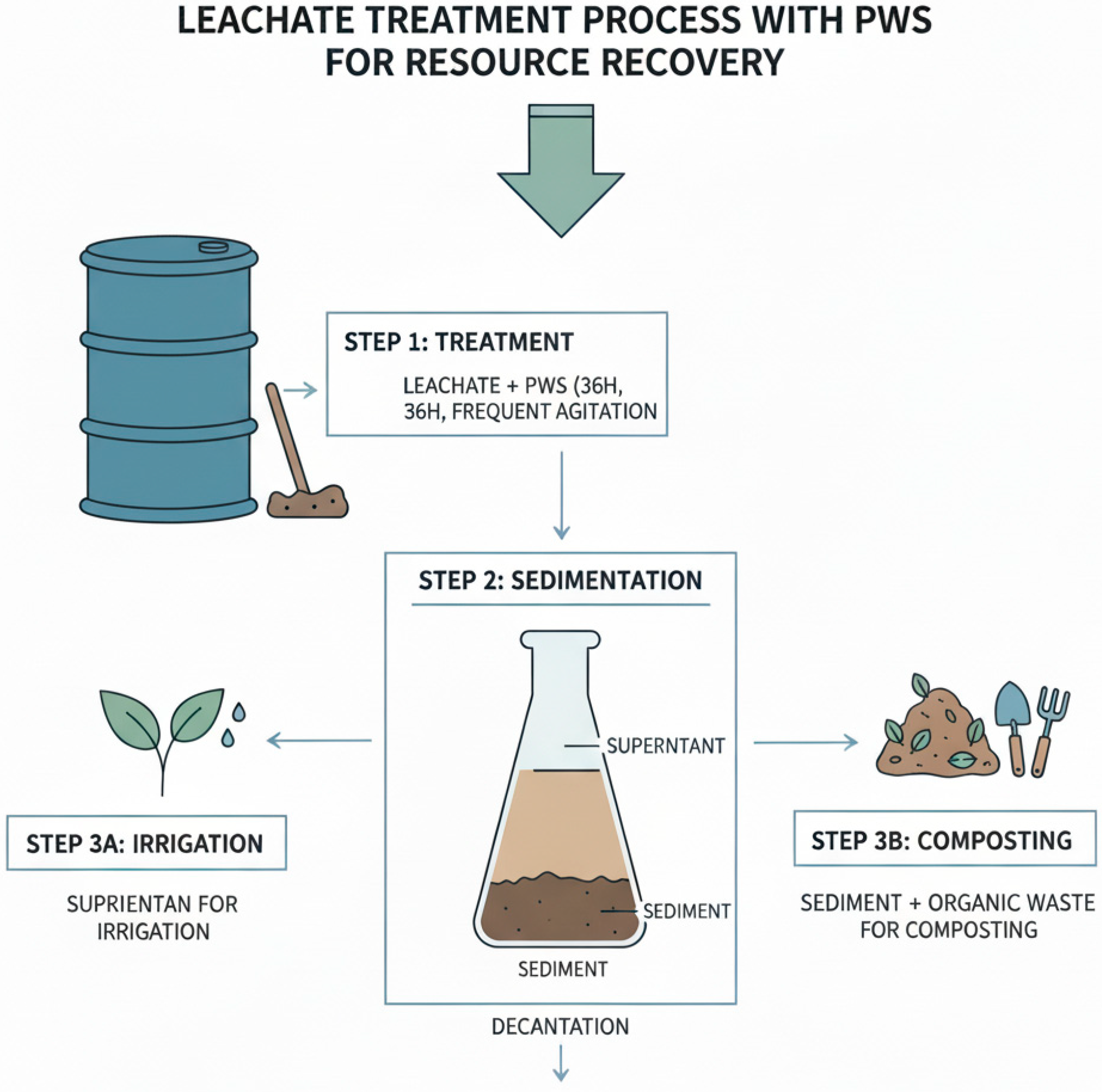

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Treatment Procedure

2.2.2. Bacteriological Analyses

- Total Aerobic Mesophilic Flora (TAMF) was measured according to ISO 4833, using Plate Count Agar (Biokar Diagnostics, Allone, France) and incubated at 30 °C for 72 h.

- Fecal Streptococci were determined following ISO 7899-2 using BEA agar (Biokar Diagnostics, Allone, France),

- Total and Fecal Coliforms were analyzed using NF ISO 9308-1, applying lactose agar supplemented with tergitol 7 and TTC (Biokar Diagnostics, Allone, France).

2.2.3. Phytotoxicity Test

2.2.4. Composting of the Sediment

2.2.5. Chemical Analyses and Suitability for Irrigation

- pH AFNOR NF ISO 10-390 (BioBase 900 multiparameter, Jinan, China);

- Electrical conductivity (BioBase 900 multiparameter, Jinan, China);

- Organic matter (OM) by calcination at 600 °C;

- Total Kjeldahl Nitrogen (TKN): The five windrows were evaluated using conventional physicochemical parameters commonly monitored during composting. Moisture content was measured on 100 g of fresh material after oven-drying at 105 °C for 24 h, and pH was determined in a 1:10 (w/v) water extract. Organic matter (OM) was quantified by ignition at 650 °C for 6 h according to the AFNOR NF V18-101 (1988) standard, and total organic carbon (TOC) was calculated from OM according to the empirical equation:

- Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD): COD was analyzed using the dichromate reflux method (APHA Standard Methods 5220D).

- Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD5): BOD5 was determined by incubating samples at 20 °C for 5 days, and oxygen consumption was measured following APHA Standard Methods 5210B.

2.2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Physico-Chemical Characteristics of Supernatants

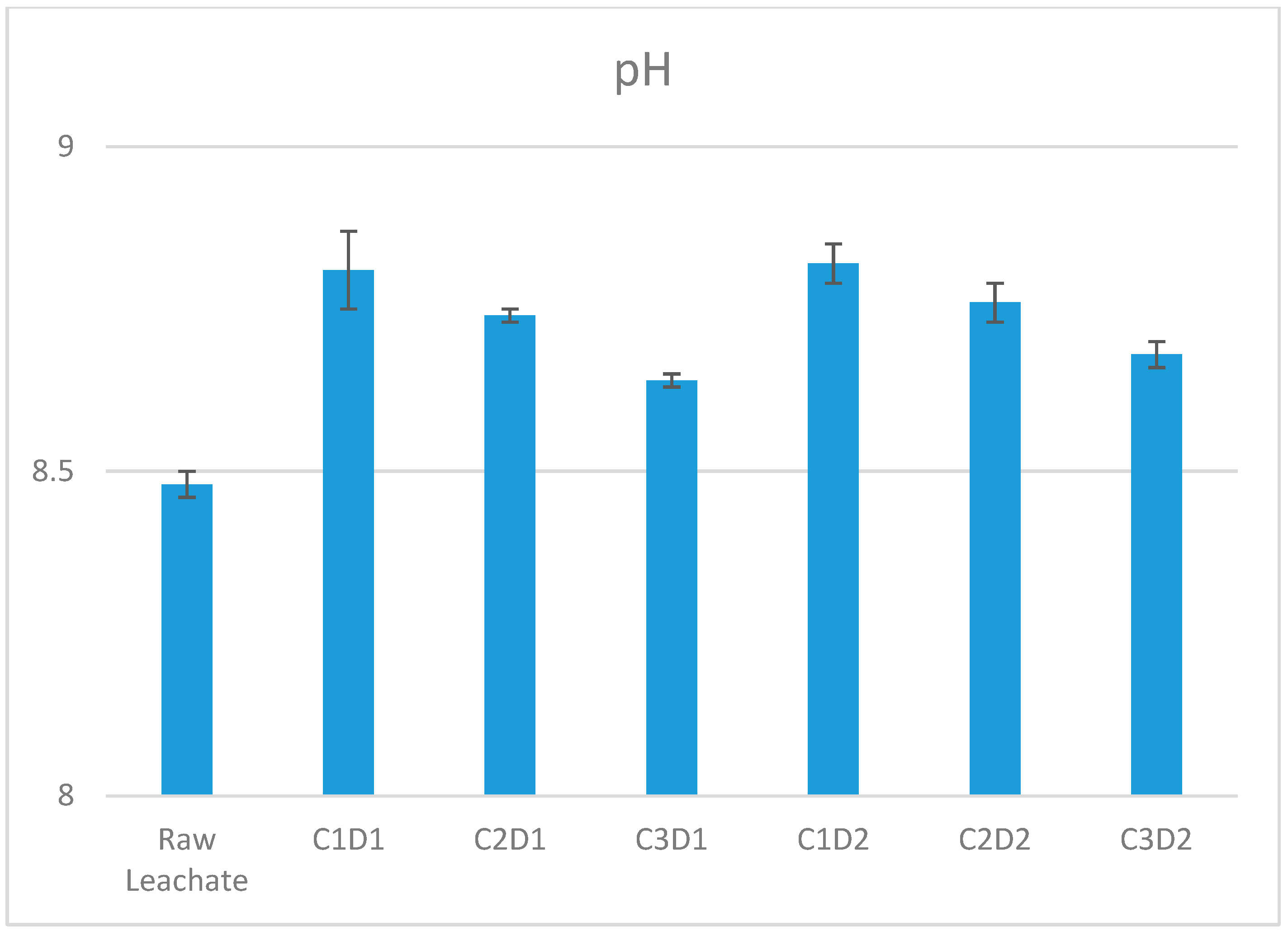

3.1.1. pH Values After Leachate Treatment with Three Concentrations of Phosphate Washing Sludge

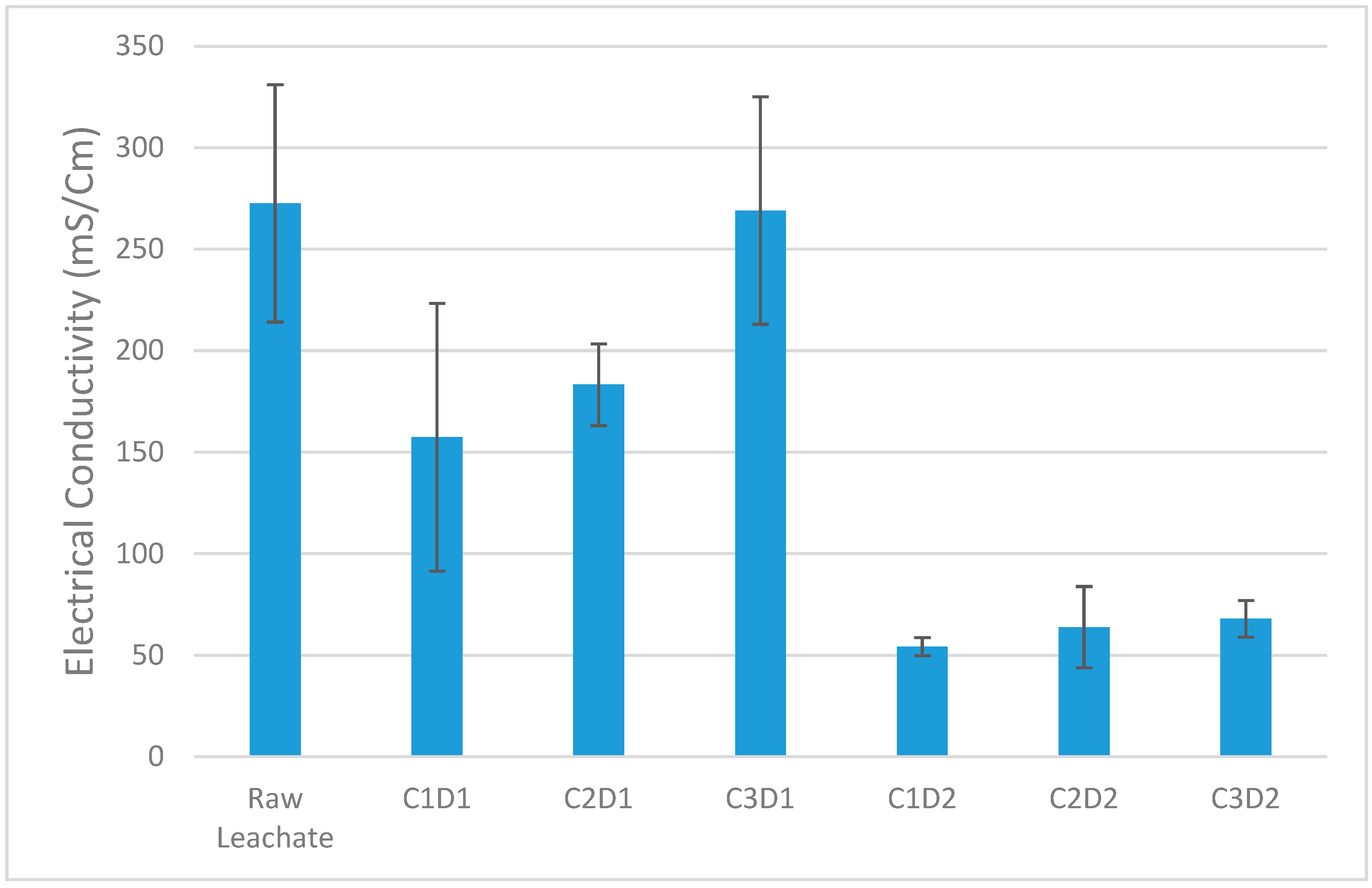

3.1.2. Electrical Conductivity After Treatment with Phosphate Washing Sludge

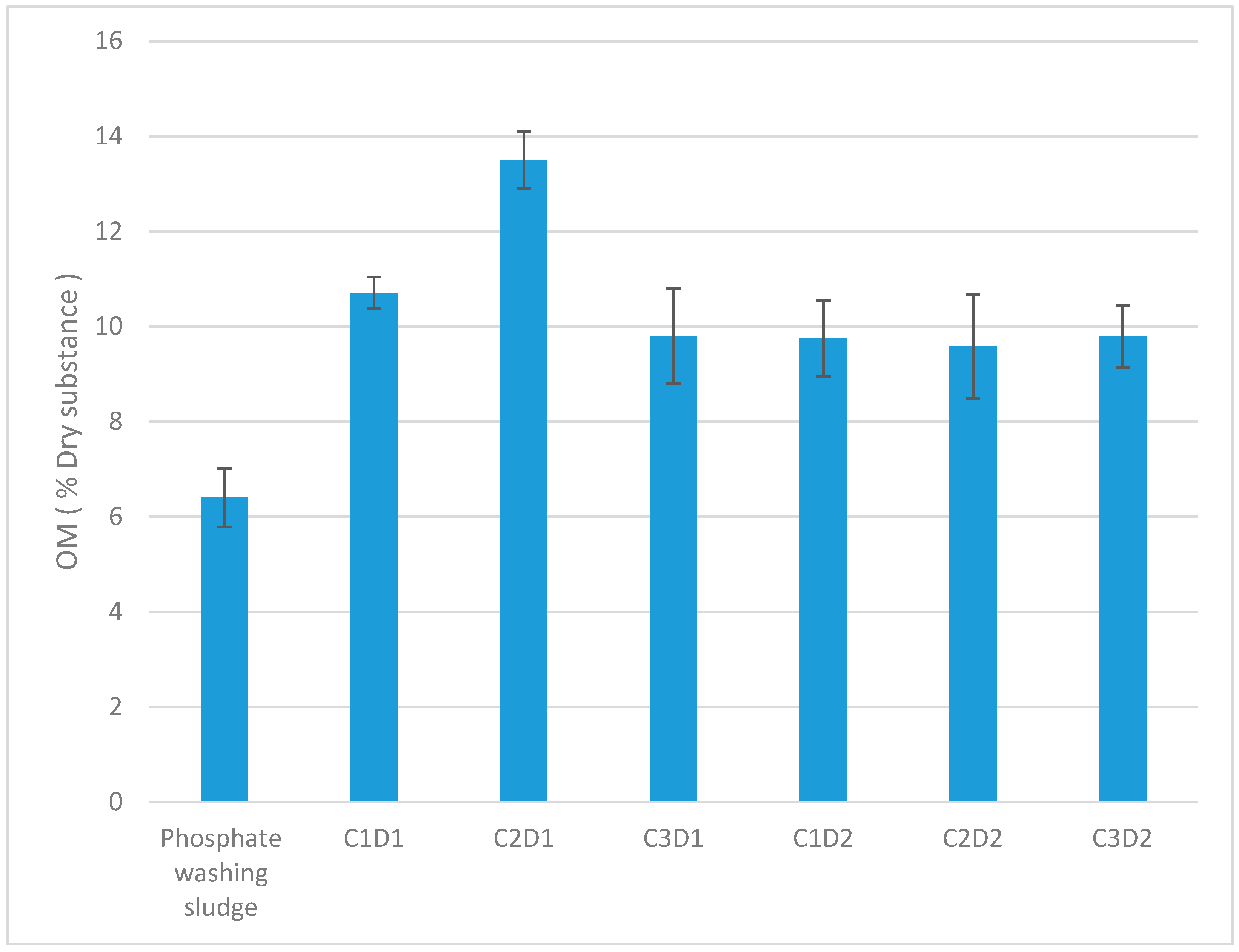

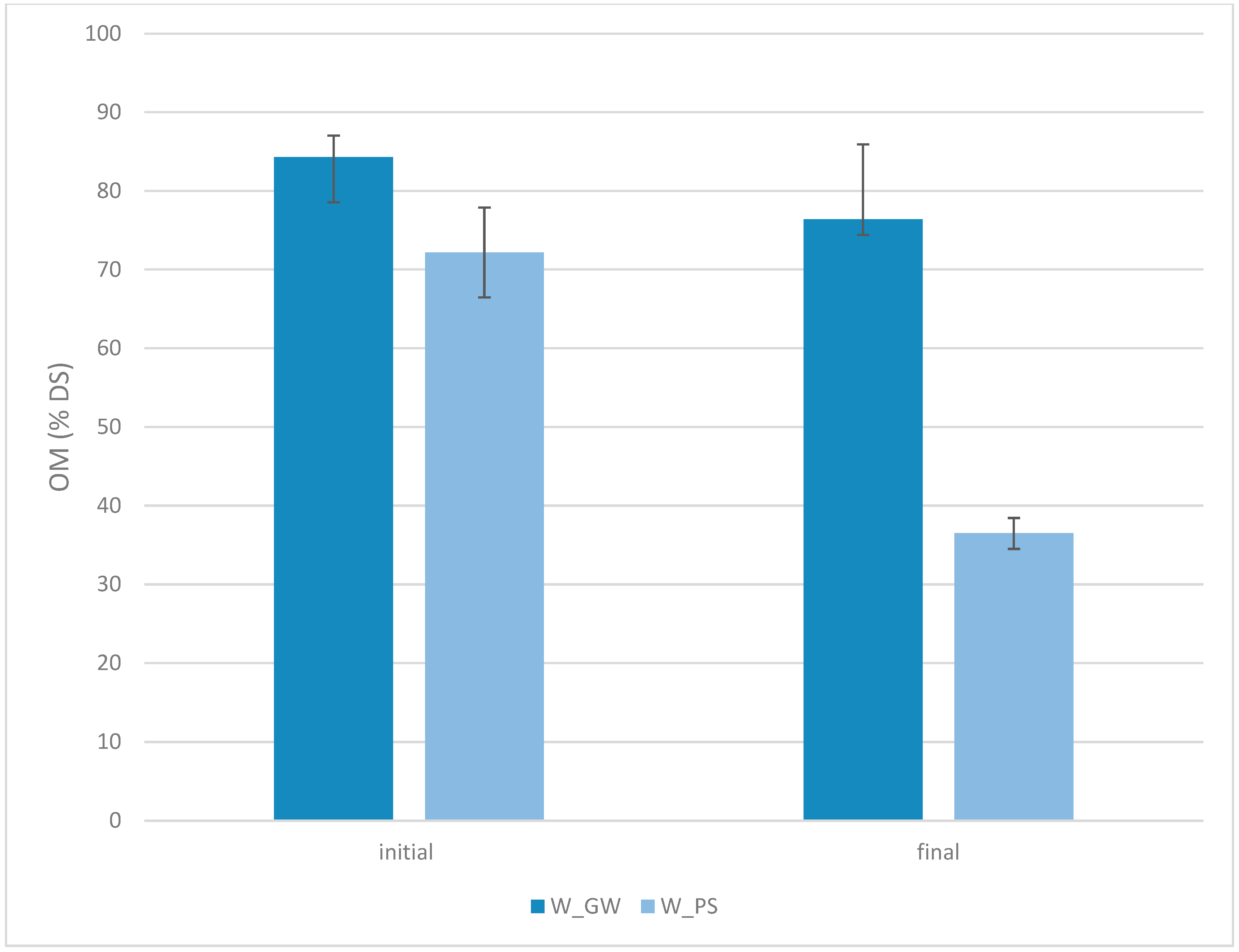

3.2. Organic Matter Content in the Sediment After Leachate Treatment

3.3. Phytotoxicity Assessment of Treated Leachate for Irrigation Potential

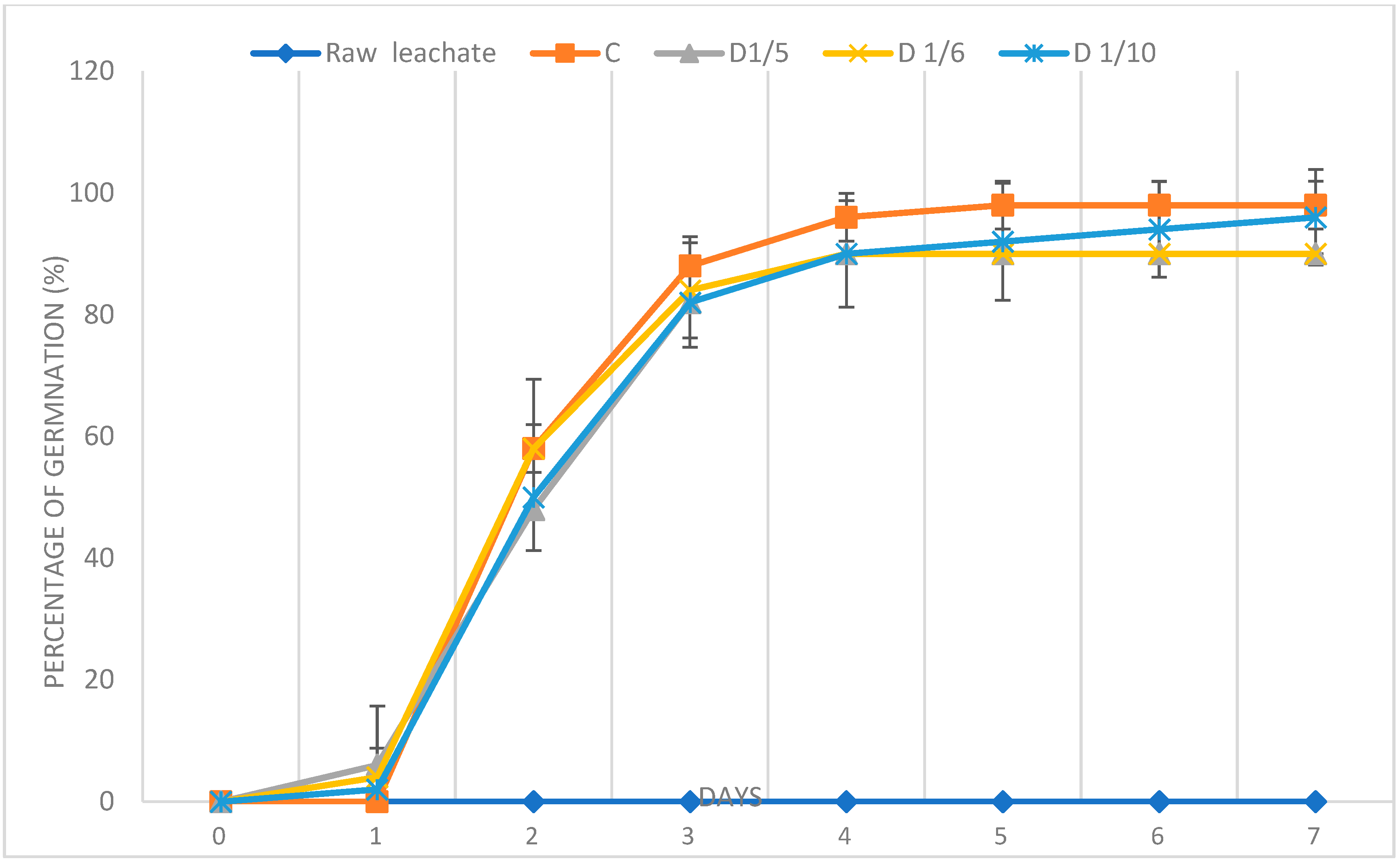

3.3.1. Germination Percentage

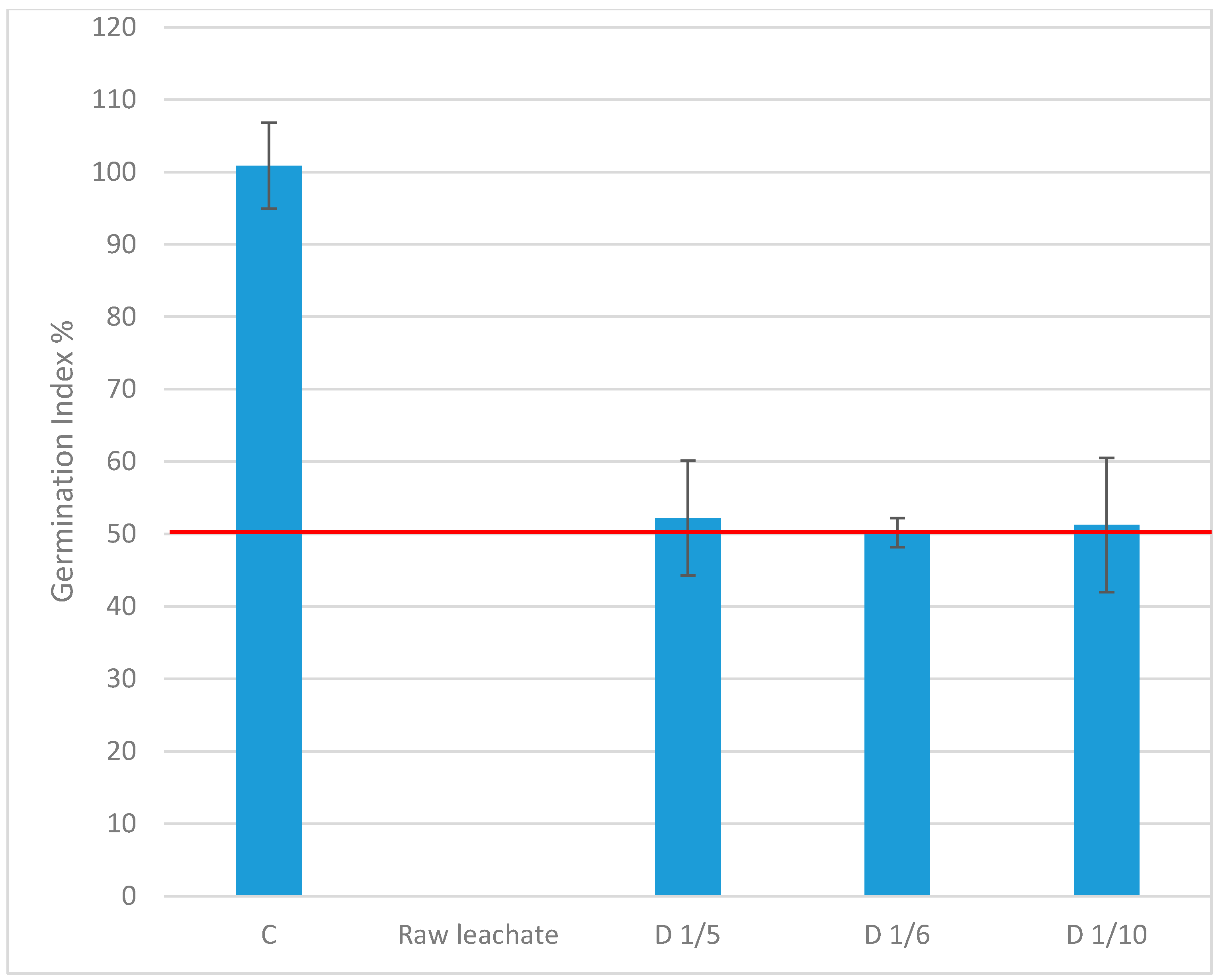

3.3.2. Germination Index

3.4. Microbiological Findings

3.4.1. Raw Leachate

3.4.2. Fecal Streptococci After Treatment with Phosphate-Washing Sludge

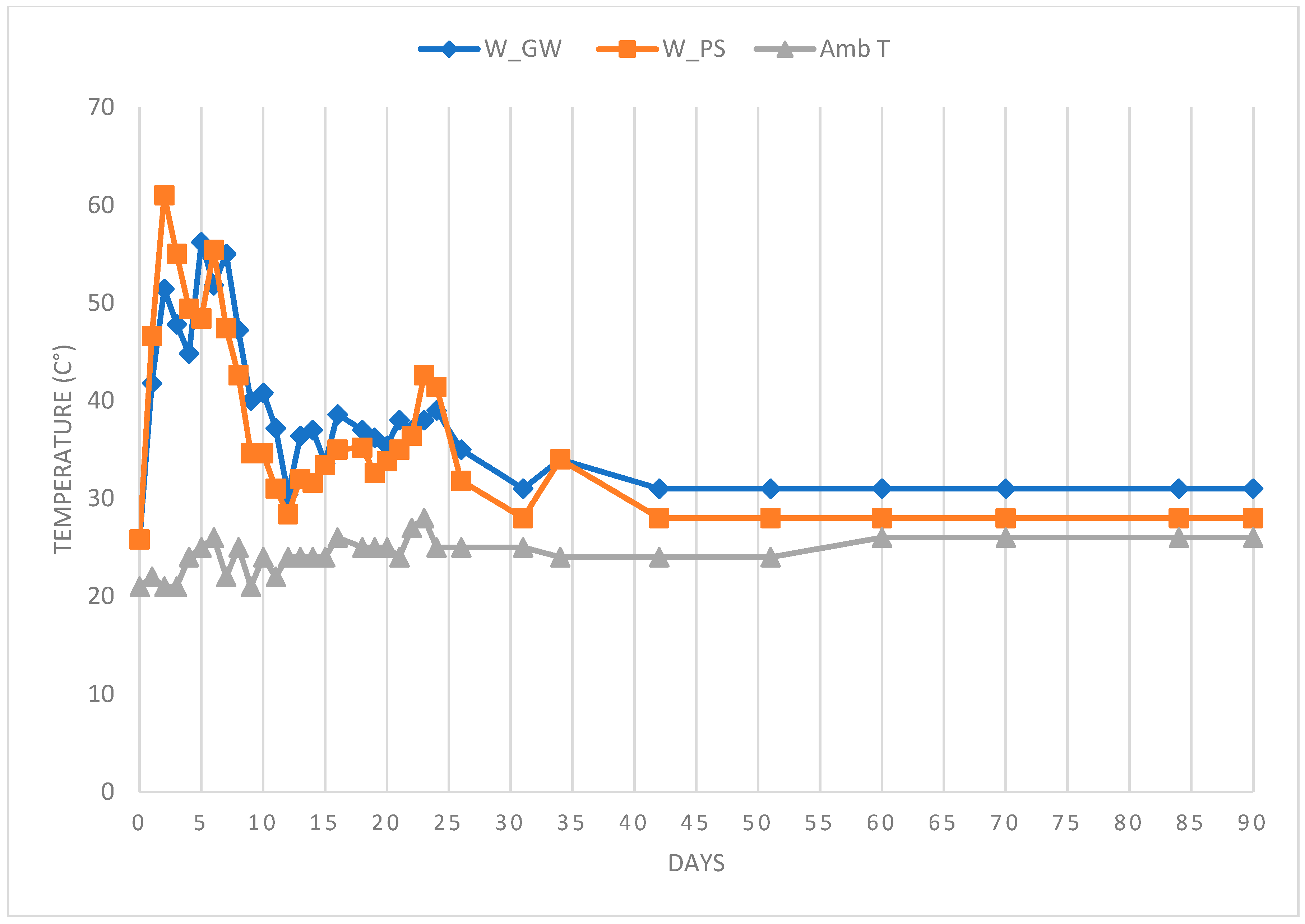

3.5. Composting of Sediment with Green Waste

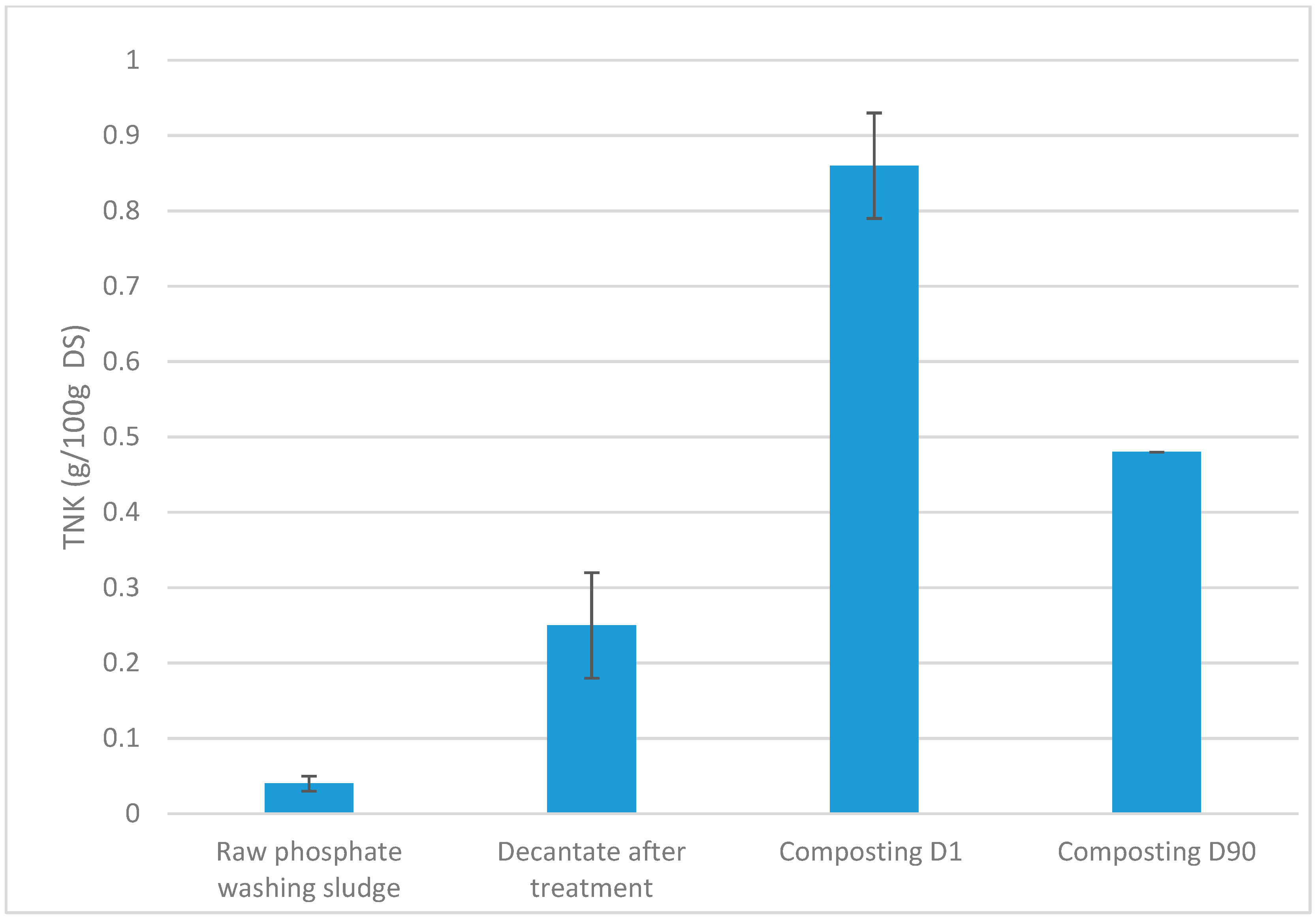

3.6. Evolution of Total Nitrogen Content Throughout the Treatment and Composting Process

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNEP. Global Waste Management Outlook 2024. United Nations Environment Programme, 2024. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/global-waste-management-outlook-2024 (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Singh, P.; Bisen, M.; Kulshreshtha, S.; Kumar, L.; Choudhury, S.R.; Nath, M.J.; Mandal, M.; Kumar, A.; Patel, S.K.S. Advancement in anaerobic ammonia oxidation technologies for industrial wastewater treatment and resource recovery: A comprehensive review and perspectives. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, R.; Wei, W.; Mei, T.; Wei, Z.; Yang, X.; Liang, J.; Zhu, J. A Review on Landfill Leachate Treatment Technologies: Comparative Analysis of Methods and Process Innovation. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Times of India. Leachate from Bandhwari Spills into Aravalis, Forms Toxic Puddles. Available online: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/gurgaon/leachate-from-bandhwari-spills-into-aravalis-forms-toxic-puddles/articleshow/122305718.cms (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Gunarathne, V.; Phillips, A.J.; Zanoletti, A.; Rajapaksha, A.U.; Vithanage, M.; Di Maria, F.; Pivato, A.; Korzeniewska, E.; Bontempi, E. Environmental pitfalls and associated human health risks and ecological impacts from landfill leachate contaminants: Current evidence, recommended interventions and future directions. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neill, P.; Megson, D. Landfill leachate treatment process is transforming and releasing banned per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances to UK water. Front. Water 2024, 6, 1480241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagwar, P.P.; Dutta, D. Landfill leachate: A potential challenge towards sustainable environmental management. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 926, 171668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njewa, J.B.; Mweta, G.; Sumani, J.; Biswick, T.T. The impact of dumping sites on air, soil and water pollution in selected Southern African countries: Challenges and recommendations. Water Emerg. Contam. Nanoplastics 2025, 4, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goukeh, M.N.; Ssekimpi, D.; Asefaw, B.K.; Zhang, Z. Occurrence of per- and polyfluorinated substances, microplastics, pharmaceuticals and personal care products as emerging contaminants in landfill leachate: A review. Total Environ. Eng. 2025, 3, 100019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, C.; Chen, W. Technologies for the treatment of emerging contaminants in landfill leachate. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2023, 31, 100409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindamulla, L.; Nanayakkara, N.; Othman, M.; Jinadasa, S.; Herath, G.; Jegatheesan, V. Municipal solid waste landfill leachate characteristics and treatment options in tropical countries. Water Pollut. 2022, 8, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamrah, A.; Al-Zghou, T.M.; Al-Qodah, Z. An extensive analysis of combined processes for landfill leachate treatment. Water 2024, 16, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Shafy, H.I.; Ibrahim, A.M.; Al-Sulaiman, A.M.; Okasha, R.A. Landfill leachate: Sources, nature, organic composition, and treatment—An environmental overview. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2024, 15, 102293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisht, T.S.; Kumar, D.; Alappat, B.J. Revised leachate pollution index (r-LPI): A tool to quantify contamination potential. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 168, 1142–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abunama, T.; Moodley, T.; Abualqumboz, M.; Kumari, S.; Bux, F. Variability of leachate quality and polluting potentials in light of the leachate pollution index (LPI): A global perspective. Chemosphere 2021, 282, 131119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, W.; Wang, X. Comprehensive review of landfill leachate treatment technologies. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1439128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, K.; Song, J.; Xi, B.; Yuan, Y.; Tan, W. Generation mechanisms, environmental behaviors, and treatment technologies of conventional and emerging contaminants in landfill leachate: A review. Environ. Ecol. Contam. 2026, 8, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Rana, R.; Shukla, P. Characteristics and treatability of landfill leachate in aging landfills. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 901, 1675872. [Google Scholar]

- Clemente, E.; Domingues, E.; Quinta-Ferreira, R.M.; Leitão, A.; Martins, R.C. European and African landfilling practices: An overview on MSW management, leachate characterization and treatment technologies. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 66, 105931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobaligh, M.; Meddich, A.; Imziln, B.; Fares, K. The use of phosphate washing sludge to recover by composting the leachate from the controlled landfill. Processes 2019, 9, 1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haouas, A.; El Modafar, C.; Douira, A.; Ibnsouda-Koraichi, S.; Filali-Maltouf, A.; Moukhli, A.; Amir, S. Phosphate sludge: Opportunities for use as a fertilizer in deficient soils. Detritus 2021, 16, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakkou, R.; Benzaazoua, M.; Bussière, B. Valorization of Phosphate Waste Rocks and Sludge from the Moroccan Phosphate Mines: Challenges and Perspectives. Procedia Eng. 2016, 138, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baganna, T.; Choukri, A.; Fares, K. Sustainable treatment of landfill leachate using sugar lime sludge for irrigation and nitrogen recovery. Nitrogen 2025, 6, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucconi, F. Evaluating toxicity of immature compost. Biocycle 1981, 22, 54–57. [Google Scholar]

- Siqueira, J.F.; Lopes, H.P. Mechanisms of antimicrobial activity of calcium hydroxide: A critical review. Int. Endod. J. 1999, 32, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuzaki, S.; Azuma, K.; Lin, X.; Kuragano, M.; Uwai, K.; Yamanaka, S.; Tokuraku, K. Farm use of calcium hydroxide as an effective barrier against pathogens. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sea, Y.F.; Chua, A.S.M.; Ngoh, G.C.; Rabuni, M.F. Integrated struvite precipitation and Fenton oxidation for nutrient recovery. Water 2024, 16, 1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadaa, W. Wastewater Treatment Utilizing Industrial Waste Fly Ash as a Low-Cost Adsorbent for Heavy Metal Removal: Literature Review. Clean Technol. 2024, 6, 221–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Elements | Value |

|---|---|

| Humidity (%) | 1.5 ± 0.3 |

| OM (%DS) | 6.4 ± 0.5 |

| TNK (g/100 g DS) | 0.04 ± 0.1 |

| pH | 7.98 ± 0.02 |

| Pb (mg/kg DS) | 1.1 ± 0.01 |

| Cr (mg/kg DS) | 51.4 ± 1 |

| Cu (mg/kg DS) | 32.4 ± 0.6 |

| As (mg/kg DS) | 19.4 ± 0.4 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| pH | 8.48 ± 0.02 |

| Conductivity(mS/cm) | 272.5 ± 56.62 |

| BOD (mg O2/L) | 1400 ± 0.0 |

| COD (mg O2/L) | 25.750 ± 403.7 |

| BOD5/COD Ratio | 0.05 |

| Ni (mg/L) | 0.07 ± 0.01 |

| Cu (mg/L) | 0 |

| Pb (mg/L) | 0.01 ± 0.0 |

| Zn (mg/L) | 0.04 ± 0.0 |

| Cr (mg/L) | 0.07 ± 0.0 |

| As (mg/L) | 0.5 ± 0.1 |

| Microorganisms | CFU/mL |

|---|---|

| Fecal streptococci | 40,000 |

| Fecal coliforms | 0 |

| Total coliforms | 0 |

| Total mesophilic flora | 1,666,666.7 |

| Sample | CFU/mL | Reduction (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Raw leachate | 40,000 | - |

| C1D1 | 5800 | 85.5 |

| C2D1 | 1050 | 97.38 |

| C3D1 | 926 | 97.68 |

| C1D2 | 430 | 98.93 |

| C2D2 | 936 | 97.66 |

| C3D2 | 870 | 97.82 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baganna, T.; Choukri, A.; Sbahi, M.; Fares, K. Preliminary Evaluation of Sustainable Treatment of Landfill Leachate Using Phosphate Washing Sludge for Green Spaces Irrigation and Nitrogen Recovery. Nitrogen 2025, 6, 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/nitrogen6040113

Baganna T, Choukri A, Sbahi M, Fares K. Preliminary Evaluation of Sustainable Treatment of Landfill Leachate Using Phosphate Washing Sludge for Green Spaces Irrigation and Nitrogen Recovery. Nitrogen. 2025; 6(4):113. https://doi.org/10.3390/nitrogen6040113

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaganna, Tilila, Assmaa Choukri, Mohamed Sbahi, and Khalid Fares. 2025. "Preliminary Evaluation of Sustainable Treatment of Landfill Leachate Using Phosphate Washing Sludge for Green Spaces Irrigation and Nitrogen Recovery" Nitrogen 6, no. 4: 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/nitrogen6040113

APA StyleBaganna, T., Choukri, A., Sbahi, M., & Fares, K. (2025). Preliminary Evaluation of Sustainable Treatment of Landfill Leachate Using Phosphate Washing Sludge for Green Spaces Irrigation and Nitrogen Recovery. Nitrogen, 6(4), 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/nitrogen6040113