Abstract

The importance of this research comes from the several applications of the Mathieu equation and its generalizations in many scientific fields. Two models of fractional Mathieu equations are provided using Katugampola fractional derivatives in the sense of Riemann-Liouville and Caputo. Each model contains two fractional derivatives with unique fractional orders, periodic forcing of the cosine stiffness coefficient, and many extensions and generalizations. The Banach contraction principle is used to prove that each model under consideration has a unique solution. Our results are applied to four real-life problems: the nonlinear Mathieu equation for parametric damping and the Duffing oscillator, the quadratically damped Mathieu equation, the fractional Mathieu equation’s transition curves, and the tempered fractional model of the linearly damped ion motion with an octopole.

1. Introduction

A linear differential equation with periodic coefficients, the famous Mathieu equation was first presented by Mathieu during his research on vibrating elliptical membranes [1,2]. Traditional applications of the classical Mathieu equation, a second-order linear differential equation, include the analysis of oscillatory systems like wave propagation in periodic media or mechanical vibrations in elastic materials [3,4]. Numerous mathematical and physical problems benefit from the equation, which frequently arises in nonlinear vibration problems. The Mathieu equation is frequently the result of the wave equation’s variables being separated in elliptical coordinates [5,6]. The standard form of it is

where the generalized coordinate, y, represents the deflection angle, t is time, is the linear spring constant, is the driving amplitude, and is the excitation frequency. In the case of linear viscous damping, the Mathieu equation is known as the damped Mathieu equation and has the form

where k is the linear damping rate.

The use of an external force and equations with parametric excitation are important when studying systems with oscillatory characteristics. The Mathieu equation is frequently employed for this purpose in a variety of domains because, despite its simplicity, it can effectively express significant aspects of this phenomenon. Nonlinear terms can be added to the Mathieu equation to produce a more realistic model [7]. A nonlinear Mathieu equation for parametric damping, also referred to as the Duffing oscillator, is defined as

where is the non-zero damping coefficient, a is the oscillator’s unforced natural frequency, q is the excitation amplitude, is the excitation frequency, and Q is the Duffing coefficient.

The quadratically damped Mathieu equation has the form

The dynamics of a cable hauled by a submarine are governed by the equation of motion above, which is derived and has physical interpretations by Rand et al. [8]. More details and generalizations for the Mathieu equations can be found in the review article [9].

Fractional calculus arose around the same time as traditional integer-order calculus. Initially, the topic of modeling real-world situations with real or complex-order differential equations was unpopular among engineers and scientific researchers [10,11]. Even though numerous outstanding results have already been documented by researchers in a number of influential monographs and review articles, many non-local phenomena remain undiscovered and unexplored. We may thus learn new things about fractional modeling and applications every year. The study of fractional calculus has gained popularity since the creation of supercomputers and the development of technology that allows for more complex simulations. It is used in a variety of scientific disciplines, including biology, physics, chemistry, geology, sociology, and circuit theory [12,13]. The study of oscillatory behaviors in dynamical systems of fractional order has also drawn more interest in recent years. The fractional version makes it possible to describe systems that display cumulative or persistent behaviors more accurately by substituting fractional derivatives for integer-order derivatives [14,15].

Grace et al. [16] used the Caputo fractional derivative to examine the asymptotic behavior of non-oscillatory solutions to forced-perturbed fractional differential equations. To solve the time-fractional Navier-Stokes equations, Alqahtani et al. [17] developed analytical and approximation methods. According to [18], a nonlinear compact-polynomial computational scheme is used to explain a numerical approach for solving elliptic differential equations (on unstructured computational grids).

The memory characteristics of such materials must be described using a fractional-order model rather than an integer-order model because the vehicle’s spring and damper clearly exhibit fractional-order characteristics. The following fractional-order Mathieu equation’s transition curves that divide the zones of stability have been provided and examined by Rand et al. [19] as

where is the Riemann–Liouville (R–L) fractional derivative of order , c is the damping coefficient, is the linear spring constant, and is quantity of forcing amplitude. In reality, the fractional derivative term merges the effects of damping and stiffness into a single term as the parameter fluctuates between 0 and 1. Also, by using a model of the pantograph-catenary system, Mu et al. [20] considered the fractional-order Mathieu equation under forced excitation

where is the Caputo fractional derivative of order , is the air spring with fractional characteristics, and is a function that depends on the excitation of the train on the pantograph.

Leung et al. [21] defined the general version of the fractional Mathieu equation as follows in a slightly modified version: by adding a fractional order time derivative of the damped Mathieu equation:

They replaced the derivative of second order with fractional order . An alternative approach would be to combine the effects of stiffness and damping in a single term.

Incorporating nonlinear factors, like cubic nonlinear stiffness, into the Mathieu equation yields a more realistic model. For this model, Leung et al. [21] produced a general version of the fractional Mathieu–Duffing equation in the form

Comprehending the motion of ions is crucial for a variety of reasons, including their use in processing quantum information and accelerating calculations. Researchers have recently become interested in controlling the oscillations of trapped ions. The tempered fractional differential model of the linearly damped ion motion with an octopole is examined by Alzabut et al. [12] due to the need for a better presentation of the physical properties of ion traps and their applications, as well as the fact that only flaws of the type

where and are Caputo-type tempered fractional operators of order with and . In this case, q is a real parameter, ℓ is the fourth field harmonic relative to the quadrupole field, and is the damping constant.

Numerous studies on the definition, use, and operation of fractional order derivatives have been carried out since the concept was first developed. The most important derivatives used to model real-life problems are Riemann–Liouville, Caputo, and Hadamard. However, many formulas appeared later that are considered generalizations of these formulas. The Katugampola formula of type is considered a generalization of many of these formulas. The Katugampola fractional integral approaches the Riemann–Liouville fractional integral as and approaches the Hadamard fractional integral as . There are two approaches for the Katugampola fractional derivative, one in the sense of Riemann-Liouville called R–L–Katugampola and other in the sense of Caputo called Caputo–Katugampola.

Motivated by the previous contributions and to generalize their fractional differential equations, we study the fractional Mathieu equation.

for all with boundary conditions

using the R-L-Katugampola fractional derivatives of order , of order , and of order and type . Additionally, we study the fractional Mathieu equation

for all with boundary conditions

using the Caputo–Katugampola fractional derivatives of order , of order , and of order and type .

Furthermore, our study stands out due to its numerous novelties, unique features, and innovative characteristics:

- It is worth noting that all preceding contributions are specialized cases of the two previous fractional Mathieu equations, including Equation (9), which will be explained later.

- Furthermore, our results can be used for a wide range of Mathieu equation applications, both fractional and ordinary, which are too many to discuss here.

- An efficient tool for the analysis of systems with nonlinear or cumulative characteristics is the R–L–Katugampola fractional derivative, which is especially helpful for controlling the boundary behavior of solutions at key places like zero and infinity.

- On the other hand, the Caputo–Katugampola fractional derivative offers flexibility and versatility by permitting more accurate modeling of systems with time-dependent behaviors and long memory effects.

- Also, the Caputo–Katugampola fractional derivative is more applicable for real-life problems due to its relation to the exact initial and boundary conditions, and it, with integer order, approaches the ordinary derivative.

- The fractional Mathieu equation, when paired with these advanced fractional operators, enables a better understanding of systems exhibiting oscillatory behavior, resonant phenomena, and stability under non-standard boundary conditions.

- With the use of these tools, we hope to provide novel insights, fresh perspectives, and answers to challenging problems in applied mathematics and physics.

We organize our paper as follows: The next section is devoted to providing some concepts, definitions, and properties for fractional calculus. Section 3 is concerned with the model of the fractional Mathieu equation with the Riemann–Liouville–Katugampola fractional derivative. The other model with the Caputo–Katugampola fractional derivative is offered in Section 4. Our results are applied to four real-life problems in Section 5: the nonlinear Mathieu equation for parametric damping and the Duffing oscillator, the quadratically damped Mathieu equation, the fractional Mathieu equation’s transition curves, and the tempered fractional model of the linearly damped ion motion with an octopole.

2. Preliminaries

To support the readers, we offer some fundamental definitions and lemmas that will be utilized throughout this investigation. Take and is a Banach space on I. Let the Banach space contain all continuous functions on I equipped with the norm . The weighted Banach space can be defined as

equipped with the norm

Take into consideration the space (for , , ) that contains Lebesgue measurable functions y on with real-valued and , and

Furthermore, consider the spaces

and

It is clear that the spaces and are Banach spaces equipped with the norms, respectively,

and

Definition 1

([22]). Let and be the set of absolute continuous functions on I. Then, we define

Definition 2

([23]). Let , , and . Then, the Katugampola fractional integral of order and type is defined by

Theorem 1

([23]). Let , , , and such that . Then, the semigroup property is valid for ; we have

Definition 3

([23]). Let , , and . Then, the R–L–Katugampola fractional derivative is defined by

where , and .

Theorem 2

([22]). Let , , . Then,

Lemma 1

([24]). Let , , and . Then,

Theorem 3

([23]). Let , , and such that . Then, for and , we have

Lemma 2.

Let , , and such that . Then, for and , we have

Proof.

By using Theorem 2 and Lemma 1 while noting , we have

which ends the proof. □

Definition 4

([22]). Let , , and . Then, the Caputo–Katugampola fractional derivative of order α is defined by

Theorem 4

([22]). Let , and or and . Then, we have

Lemma 3.

Let and such that . Then, for or , we have

Proof.

By using Theorem 4 and Lemma 1 while noting , we have

which is the desired result. □

Lemma 4

([25]). Let such that , , , and . Then,

Lemma 5.

Let in Lemmas 2 and 3. Then, we get

3. R–L–Katugampola Fractional Integral

Assume , , and . Consider the linear fractional Mathieu equation

with boundary conditions

where k is the linear damping rate, is the linear spring constant, is the driving amplitude, is excitation frequency, and .

Lemma 6.

Let , , and . Then, the problem (12) has a unique solution

Proof.

Let and , which leads to . Using Theorem 3 and Lemma 1 gives

Assume the following condition:

- Let where is continuous;

- There exists a positive constant L such thatwhere and .

For appropriateness, we take

where ,

It is easy to see that

Theorem 5.

Proof.

We define the mapping

which has, from (14), the fractional derivative

Now, we show that where is a closed ball defined as

with radius

From the assumptions, we have

which implies that

Similarly, we find that

which implies that

These lead to

which implies that the mapping maps into itself.

Now, for , while using the assumption , we have

which implies that

Similarly, we find that

These lead to

As , the mapping is a contraction and therefore there exists a unique fixed point such that . Any fixed point of is the solution of Equation (10). □

4. Caputo–Katugampola Fractional Derivative

Assume , and . Consider the linear fractional Mathieu equation

with boundary conditions

where k is the linear damping rate, is the linear spring constant, is the driving amplitude, is excitation frequency, and .

Lemma 7.

Let , , , and . Then, the problem (17) has a unique solution

Proof.

Let . Using Theorem 4 and Lemma 4, give

For appropriateness, we take

where .

Theorem 6.

Proof.

We define the mapping

Now we can show that , where is a closed ball defined as with radius

From the assumptions, as in the previous section, we have

which implies that

Similarly, we find that

These lead to

which implies that the mapping maps into itself. Now, for , we have

which implies that

Similarly, we find that

These lead to

As , the mapping is a contraction; therefore, there exists a unique fixed point such that . □

5. Applications

The Mathieu equation represented by Equation (3) is considered a generalization of Equations (1) and (2), so we choose it as the first application. Also, we investigate Equation (4) due to it being slightly different. For the fractional Mathieu equation, we examine the Equations (5), (8), and (9). It is worth mentioning that it is preferable to obtain the ordinary differential equations from the fractional differential equations in the sense of Caputo. Therefore, we investigate all problems with Caputo–Katugamploa except for the fractional Mathieu Equation (5) because it contains an R–L fractional derivative.

5.1. The Mathieu Equation (3)

The parametric damping nonlinear Mathieu equation, also referred to as the Duffing oscillator, was introduced by El-Dib [7]. This is demonstrated in Equation (3) with , , and , where is a non-zero damping coefficient, a is an oscillator unforced natural frequency, and is an excitation amplitude. Our Equation (11) converts to Equations (3) if , , , and the function . Let and . Then,

which implies that , for all and hence

According to Theorem 6 and the radius of the ball, we get

which implies that

In view of the above, we have to take for all . According to Theorem 6, there is a unique solution in the closed ball with the previous radius. In view of our equation, we note that is a trivial solution if . Therefore, the unique solution of the problem (3) in the ball with radius , is if .

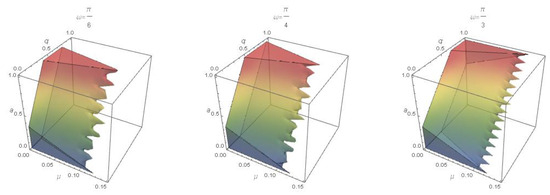

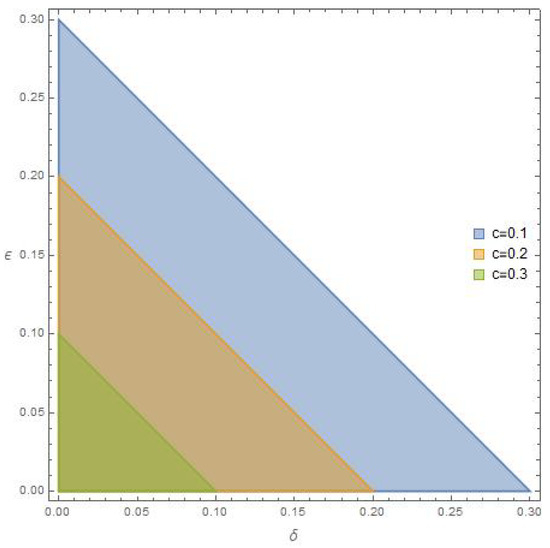

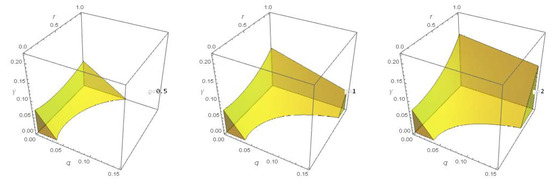

The three graphs in Figure 1 show the region of the unique solution to Equation (3) under the plane at various values of the excitation frequency in -space. While the three graphs in Figure 2 show the region of the unique solution at various values oscillator unforced natural frequency a and the excitation frequency in -plane. It is clear that the region of the existence increases with the value of .

Figure 1.

The region of the unique solution to Equation (3) at various values of .

Figure 2.

The region of the unique solution to Equation (3) at various values of and a.

5.2. The Quadratical Damped Mathieus Equation (4)

Rand et al. [8] introduced The quadratically damped Mathieus Equation (4), which is the simplest model of a towed mass, and analyzed it for linear stability and nonlinear dynamical effects. The mass is assumed to move exclusively in the horizontal direction y, which is perpendicular to the other two directions. This is demonstrated with , , , which indicates the non-dimensional mean value of the towline tension; reflects the amplitude of the towline tension’s oscillating portion, and for all and , which satisfies

for all , with , , and . Here, we take , and which lead to

These lead to

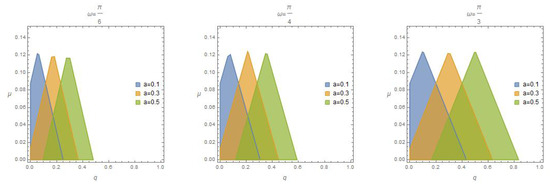

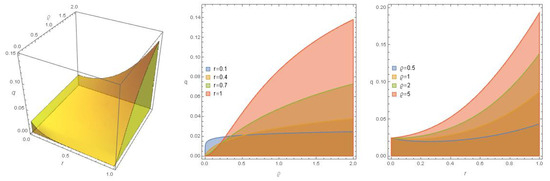

which implies that . It is clear from this inequality that the area of the region containing and expands as the length of the interval decreases and that the relationship between and is linear. We also find that the domain of existence of the unique solution is the area under the line in the -plane, which appears in the second graph in Figure 3 under different values of b. Also, the first graph shows the region that contains all points -space in which our problem has a unique non-zero solution. According to Theorem 6, there is a unique non-zero solution in the closed ball with radius for all points in -plane shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The region of the unique solution to Equation (4) in -space and in -plane at various values of b.

5.3. The Fractional Mathieu Equation (5)

Rand et al. [19] provided and examined the fractional-order Mathieu equation’s transition curves (5) that divide the zones of stability. This is demonstrated with , , , indicating the non-dimensional mean value of the towline tension; reflects the amplitude of the towline tension’s oscillating portion, and for all , , and , which satisfies

for all , with , , and . Here, we take , , and , which lead to

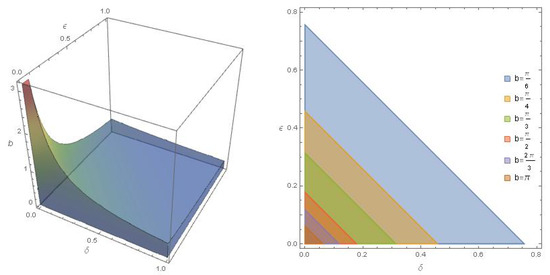

These lead to if according to Theorem 5, which implies that where

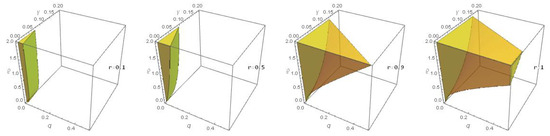

It is easy to see that the function is increasing for all and has a supremum value of , so . The four graphs in Figure 4 show the region of the existence of the unique solution under the yellow plane in -space with different values of b. They show that the larger the value of , the wider the region of existence. The second Figure 5 shows the region of existence at different values of the damping coefficient c at the supremum value of . It is obvious from this figure that the region of existence extends with decreasing value of the damping coefficient c.

Figure 4.

The region of the unique solution to Equation (5) at various values of fractional order .

Figure 5.

The region of the unique solution to Equation (5) at various values of c and supremum value of fractional order .

It is worth noting that if we take for all and , then we obtain the same results. In the light of Theorem 5, there is a unique non-zero solution in the closed ball with the previous radius.

In light of (21), we get . Also, Figure 5 shows that the existence of the unique solution is verified at any point in the region. Therefore, if we take , then , which implies that . The last inequality holds if we take or . These imply for any point in the plane.

5.4. The Tempered Fractional Mathieu Equation (9)

First, we need to prove the relation between , and where and . This can easily show by using Definition 4 and Lemma 1 as

where C is a constant, provided that . Hence, the tempered fractional Mathieu Equation (9) can be read as

The tempered fractional Mathieu Equation (9) can be demonstrated with , , , , , , , and for all , which satisfies

for all , with , , and , which lead to

These lead to

where

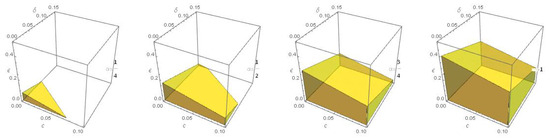

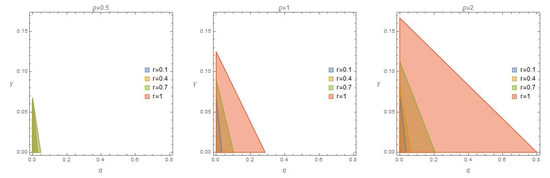

which implies that . According to Theorem 6, there is a unique non-zero solution in the closed ball with radius . The three graphs in Figure 6 and the four graphs in Figure 7 show the region of the existence of the unique solution under the yellow plane in -space and -space with various values of the fractional derivative type and fractional order r, respectively. It is clear that the region expands with the increase in the value of the type and order. The three graphs in Figure 8 show the region of the unique solution to Equation (9) at various values of the fractional derivative type and fractional order r. At , the first graph in Figure 9 shows the region of the unique solution to Equation (9) in -space, while the last two graphs show the region of the existence at various values of the fractional derivative type and fractional order r and fractional order r.

Figure 6.

The region of the unique solution to Equation (9) at various values of the fractional derivative type .

Figure 7.

The region of the unique solution to Equation (9) at various values of the fractional order r.

Figure 8.

The region of the unique solution to Equation (9) at various values of the fractional derivative type and fractional order r.

Figure 9.

The region of the unique solution to Equation (9) at and various values of the fractional derivative type and fractional order r.

6. Conclusions

This paper concerned two models of the fractional Mathieu equation. The first was the Riemann–Liouville Katugampola fractional derivative, while the other model was the Caputo–Katugampola fractional derivative. It turned out that the Caputo–Katugampola fractional derivative is more applicable to real-life problems due to its relation to the exact initial and boundary conditions and . Thus, we used the Caputo–Katugampola fractional derivative with the special cases containing the ordinary derivative. The Banach contraction principle is used to prove that each model under consideration has a unique solution. Our results were applied to four real-life problems: the nonlinear Mathieu equation for parametric damping and the Duffing oscillator (3), the quadratically damped Mathieu Equation (4), the fractional Mathieu equation’s transition curves (5), and the tempered fractional model of the linearly damped ion motion with an octopole (9). Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9 show the regions of the existence of the unique solution for several models of ordinary and fractional Mathieu equations in 3-dimensional space and 2-dimensional plane.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.; Methodology, A.S.; Software, H.M.; Validation, N.A.; Formal analysis, N.A.; Investigation, H.M. and N.A.; Resources, H.M.; Writing—original draft, H.M. and N.A.; Writing—review & editing, A.S.; Visualization, N.A.; Supervision, A.S.; Funding acquisition, H.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research work was funded by Institutional Fund Projects under grant no. (IFPIP: 1263-247-1443). The authors gratefully acknowledge technical and financial support provided by the Ministry of Education and King Abdulaziz University, DSR, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ricciardi, M.C.; Spagnolo, G. The fractional Mathieu equation: Application to vibrating systems. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2018, 61, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Gadella, M.; Giacomini, H.; Lara, L.P. Periodic analytic approximate solutions for the Mathieu equation. Appl. Math. Comput. 2015, 271, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Bakry, E.M. Fractional Mathieu equation and its applications in stability analysis. Math. Comput. Simul. 2016, 123, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, D.J. Exact solutions of Mathieu’s equation. Prog. Theor. Exp. Phys. 2020, 2020, 043A01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLachlan, N.W. Theory and Application of Mathieu Functions; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Adel, M.; Khader, M.M. Theoretical and numerical treatment for the fractal-fractional model of pollution for a system of lakes using an efficient numerical technique. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 82, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Dib, Y.O. An innovative efficient approach to solving damped Mathieu-Duffing equation with the non-perturbative technique. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2024, 128, 107590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rand, R.H.; Ramani, D.V.; Keith, W.L.; Cipolla, K.M. The Quadratically Damped Mathieu Equation and Its Application to Submarine Dynamics. In Control of Noise and Vibration: New Millenium, AD-Vol.61; ASME: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacic, I.; Rand, R.H.; Mohamed, S.S. Mathieu’s Equation and Its Generalizations: Overview of Stability Charts and Their Features. ASME. Appl. Mech. Rev. 2018, 70, 020802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, A.; Almaghamsi, L. Solvability of Sequential Fractional Differential Equation at Resonance. Mathematics 2023, 11, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, A.; Abdullah, S. Controllability results to non-instantaneous impulsive with infinite delay for generalized fractional differential equations. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 70, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzabut, J.; Selvam, A.G.M.; Vignesh, D.; Etemad, S.; Rezapour, S. Stability analysis of tempered fractional nonlinear Mathieu type equation model of an ion motion with octopole-only imperfections. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2023, 46, 9542–9554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zhang, Y.; Baleanu, D.; Chen, W.; Chen, Y. A new collection of real world applications of fractional calculus in science and engineering. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2018, 64, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaghamsi, L.; Salem, A. Fractional Langevin equations with infinite-point boundary condition: Application to Fractional harmonic oscillator. J. Appl. Anal. Comput. 2023, 13, 3504–3523. Available online: http://www.jaac-online.com/article/doi/10.11948/20230124 (accessed on 19 December 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salem, A. Existence results of solutions for anti-periodic fractional Langevin equation. J. Appl. Anal. Comput. 2020, 10, 2557–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grace, S.R.; Chhatria, G.N.; Kaleeswari, S.; Alnafisah, Y.; Moaaz, O. Forced-Perturbed Fractional Differential Equations of Higher Order: Asymptotic Properties of Non-Oscillatory Solutions. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, A.M.; Mihoubi, H.; Arioua, Y.; Bouderah, B. Analytical Solutions of Time-Fractional Navier–Stokes Equations Employing Homotopy Perturbation–Laplace Transform Method. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzenov, V.V.; Ryzhkov, S.V.; Varaksin, A.Y. Development of a Method for Solving Elliptic Differential Equations Based on a Nonlinear Compact-Polynomial Scheme. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2024, 451, 116098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rand, R.H.; Sah, S.M.; Suchorsky, M.K. Fractional Mathieu equation. Commun. Nonlin. Sci. Numer. Simulat. 2010, 15, 3254–3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, R.; Wen, S.; Shen, Y.; Si, C. Stability Analysis of Fractional-Order Mathieu Equation with Forced Excitation. Fractal Fract. 2022, 6, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, A.Y.T.; Guo, Z.; Yang, H.X. Transition curves and bifurcations of a class of fractional mathieu-type equations. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 2012, 22, 1250275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarad, F.; Abdeljawad, T.; Baleanu, D. On the generalized fractional derivatives and their Caputo modification. J. Nonlinear Sci. Appl. 2017, 10, 2607–2619. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:59607625 (accessed on 19 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Katugampola, U.N. New approach to a generalized fractional integral. Appl. Math. Comput. 2011, 218, 860–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, R.; Malinowska, A.B.; Odzijewicz, T. Fractional differential equations with dependence on the Caputo-Katugampola derivative. J. Comput. Nonlinear Dyn. 2016, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, A.; Alharbi, K.N.; Alshehri, H.M. Fractional Evolution Equations with Infinite Time Delay in Abstract Phase Space. Mathematics 2022, 10, 1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).