Abstract

This study investigates the synchronization of coupled fractional-order Markovian reaction-diffusion neural networks (MRDNNs) with partially unknown transition rates. The novelty of this work is mainly reflected in three aspects: First, this study incorporates the Markovian switching model and reaction-diffusion term into a fractional-order system, which is a challenging and under-explored issue in existing literature, and effectively addresses the synchronization problem of fractional-order MRDNNs by introducing a continuous frequency distribution model of the fractional integrator. Second, it derives a new set of sufficient synchronization conditions with reduced conservatism; by utilizing the (extended) Wirtinger inequality and delay-partitioning techniques, abundant free parameters are introduced to significantly broaden the solution range. Third, it proposes an LMI-based optimal synchronization design by establishing an efficient offline optimization framework with semidefinite constraints, and achieves the precise solution of control gains. Finally, numerical simulations are conducted to validate the effectiveness of the proposed method.

1. Introduction

For nearly half a century, neural network research has remained an enduring research hotspot. To date, research findings in this area have been widely applied in intelligent control [1], image processing [2,3], bioprocess engineering [4], and optimization calculation [5]. Synchronization analysis is a critical component of neural network research [6,7,8,9]—given that neural networks are inherently governed by the dynamic behavior of neurons, investigating synchronization is of paramount importance.

In the field of biological and artificial neural networks, the reaction-diffusion phenomenon is a core spatiotemporal dynamic feature. For example, the activities of neurons in a non-uniform electromagnetic field and the conduction process of electrical pulses along nerve axons both involve this phenomenon. Physically, it is the coupling effect between the nonlinear reaction process of neuron states and the spatial diffusion process of state variables. Specifically, the reaction process corresponds to the nonlinear activation and state update mechanism of neurons, while the diffusion process corresponds to the spatial propagation characteristic of neuron states. In biological scenarios, it can manifest as the change in membrane potential in adjacent regions caused by action potentials on nerve axons through local currents and the spatial distributed transmission of neurotransmitters in synaptic clefts. In artificial scenarios, it can correspond to the spatial correlation and transmission of signals between sensor nodes and image pixels, such as signal diffusion in industrial sensor arrays and spatial feature propagation in visual networks. Since traditional ordinary differential equations (ODEs) cannot characterize this spatiotemporal cooperative dynamic characteristic, partial differential equations (PDEs) incorporating reaction-diffusion terms have been developed. Such equations can not only accurately describe the spatiotemporal evolution laws of real neural networks but also provide a physical-level analytical framework and support for engineering and theoretical problems.

Previously, the stability and synchronization of neural networks under reaction-diffusion effects were studied extensively [10,11,12]. For instance, ref. [10] was concerned with global exponential synchronization of a delayed fuzzy reaction diffusion neural networks (RDNNs) via adaptive intermittent control. In [11], the stability of the nontrivial stationary solution of delayed RDNNs was analyzed. In [13], impulsive synchronization of RDNNs with input saturation was investigated using a hybrid control method. Nevertheless, these studies primarily focused on integer-order reaction-diffusion systems, and currently, relatively few investigations have addressed the synchronization of fractional-order reaction-diffusion systems.

Fractional calculus is widely recognized as an extension of integral calculus [14]. Recently, with the advancement of computing technology, research in this field has witnessed breakthroughs in engineering applications [15,16,17]. Recently, breakthroughs in fractional-order chaotic dynamics, such as new phenomena in the fractional-order Rössler system [18], have further enriched the theoretical foundation. Additionally, advanced synchronization techniques like time-reversible synchronization [19,20,21] also offer novel insights for potential applications in this study.

Owing to its intrinsic memory and hereditary properties, the fractional-order derivative has been incorporated into RDNNs. For instance, in [22], an impulsive fractional-order RDNNs model was proposed, and its Mittag-Leffler stability conditions were investigated. In [23], dissipativity and synchronization control for fractional-order memristive RDNNs were explored using the fractional Halanay inequality. In [24], the synchronization control for fractional-order competitive RDNNs was examined via the M-matrix theory. Additionally, the exponential synchronization of fractional-order RDNNs with hybrid delay-dependent impulses was studied in [25].

However, most existing fractional-order RDNNs studies [22,23,24] focus solely on fixed-topology systems and fail to account for stochastic switching topologies. Although Markovian switching as a kind of stochastic switching scenario has been integrated into integer-order reaction-diffusion systems [26], it fails to capture the memory-dependent dynamics of fractional-order systems, and the combination of Markovian switching with fractional-order dynamics remains underexplored. Moreover, the interplay between reaction-diffusion terms and Markovian switching in fractional-order systems has not been systematically analyzed, despite their coexistence in many practical scenarios. These gaps highlight the need to investigate fractional-order Markovian reaction-diffusion neural networks (MRDNNs)—a model that unifies fractional-order dynamics, Markovian switching topologies, and reaction-diffusion effects to capture complex real-world behaviors.

The Markovian system, characterized by stochastic switching governed by a Markov jump process, offers a powerful framework for modeling real-world systems with dynamic topological changes, for example, dynamic connectivity in biological neural networks [26], adaptive coupling in engineering networks [27], and stochastic transitions in financial systems. Its ability to capture random yet statistically structured switching makes it indispensable for representing complex systems where fixed-topology models fall short.

Although [26] has established sufficient synchronization conditions with low conservatism for integer-order Markovian reaction-diffusion neural networks (MRDNNs), extending these results to fractional-order systems still faces unique challenges, which stem from the memory and hereditary properties of fractional-order systems. In addition, although [27,28] have explored the synchronization of fractional-order Markovian systems, they have overlooked the spatial state variations induced by reaction-diffusion phenomena. These limitations highlight the urgency of developing a unified framework for the synchronization of fractional-order MRDNNs.

To tackle the synchronization problem of the aforementioned fractional-order MRDNNs, a tailored control strategy for the system needs to be devised. In network control systems, the limited bit rate and bandwidth of communication channels inevitably result in delays, packet losses, and erroneous packet sequences, which affect the performance of the control system. Signal quantization emerges as a key preprocessing strategy. It transforms continuous control inputs into piecewise-constant signals via specific algorithms, compressing data to reduce channel load and bandwidth requirements. Among available quantizers, logarithmic quantizers offer a unique advantage as they can uniformly quantize signals across a wide dynamic range. In the subsequent research, we employ a logarithmic quantizer to perform synchronization control on coupled fractional-order MRDNNs.

In the research field of system synchronization control, solving control gains mainly relies on the MATLAB Linear Matrix Inequality (LMI) Toolbox. However, the obtained control gains are only feasible solutions and do not consider the coupling constraints between control cost and synchronization errors. To address this limitation, the particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithm was proposed in [29,30,31]; nevertheless, its solution process relies on the online back-substitution of system iterative errors, leading to substantial computational overhead and strong dependence on the system model. For this reason, this study focuses on developing a more efficient offline optimization framework, in which a convex optimization model with semidefinite constraints is constructed to achieve the accurate solution of control gains.

This paper aims to study the optimal synchronization control of fractional-order MRDNNs with partly unknown transition rates (a more prevalent scenario in real-world contexts). The core innovations are condensed as:

(1) Model Innovation:A fractional-order MRDNNs model is constructed, integrating Markovian switching topologies and reaction-diffusion terms—marking the first attempt to unify these three elements.

(2) Method Breakthrough: By leveraging the continuous frequency distribution model of fractional integrators, coupled fractional-order MRDNNs are converted into equivalent integer-order systems. This circumvents the limitations of traditional Lyapunov methods in handling non-local, memory-dominated fractional dynamics, enabling tractable synchronization analysis.

(3) Low-Conservatism Criterion: Low-conservatism synchronization criteria are derived via LMIs by utilizing extended Wirtinger inequalities, delay partitioning, and novel Lyapunov-Krasovskii functionals. These criteria introduce abundant free parameters for flexible tuning. Additionally, quantized control reduces channel bandwidth requirements, aligning with practical network constraints.

(4) Optimal control gain: A convex optimization model with semidefinite constraints is constructed, forming an efficient offline optimization framework to realize the accurate solution of control gains.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Some necessary assumptions and lemmas are provided in Section 2. Model description and problem formulation are discussed in Section 3. Two theorems, which provide the synchronization criteria for the coupled fractional-order MRDNNs and show the optimal algorithm for the control gain, are presented in Section 4. Finally, a numerical simulation is provided to validate the effectiveness of the proposed method.

Notations. is an identity matrix. Further, represents a diagonal matrix; , and represents the transpose matrix of ; is a symbolic function, if , ; else, . The symbol ⊗ is the Kronecker product. For matrices and , implies that is positive definite. Similarly, is positive semidefinite. and represent the real number and n-dimensional real vector, respectively.

2. Preliminaries

Definition 1

(Caputo Fractional Derivative). Consider function is derivable on t, and , the Caputo fractional derivative of is defined by

Definition 2

(Fractional Integration). Consider function is integrable on t, and , the Riemann-Liouville fractional integration of is defined by

Definition 3

(Caputo Fractional Partial Derivative). Consider function is derivable on t, and , the Caputo fractional partial derivative with regard to time t for is defined by

in which

is the partial derivative of . x is spatial variable, and Δ is spatial range.

Lemma 1

(Wirtinger Inequality). Given a positive matrix , if , , then

Lemma 2

(Extended Wirtinger Inequality [32]). Given a positive symmetric matrix , for all , the following inequality holds:

with , .

Lemma 3

(Continuous Frequency Distributed Model [33]). For nonlinear fractional-order differential equation , the following state model is defined

with . is the frequency weighting function of the distributed state variable with fractional order α.

Remark 1.

Compared with traditional fractional-order approximation techniques such as the Oustaloup filter and finite difference method, the core advantage of the continuous frequency distribution model lies in its theoretical equivalence. Its theoretical basis is the frequency-domain representation of fractional-order derivatives—that is, a fractional-order derivative can be decomposed into a weighted integral of infinitely many integer-order frequency components. Through rigorous decomposition and reconstruction in the frequency domain, the model theoretically achieves approximation-error-free transformation from fractional-order to integer-order. This characteristic endows it with irreplaceable reliability and universality compared to traditional methods when dealing with nonlinear, spatiotemporally distributed fractional-order systems.

3. Model Description and Problem Formulation

Consider the following delayed fractional-order RDNNs described as

where is time Caputo fractional partial derivative. . The state vector of neurons is , which is related to time t and space x. is the feedback matrix, and . is the time-varying delay that satisfies . Let the diffusion coefficient matrix with . , where and are constants. and are the activation function with and without time delay, respectively. is the external input. The second equation in delayed fractional-order RDNNs (1) represents the Dirichlet boundary condition, and the third equation denotes the initial condition, where .

Consider N coupled fractional-order MRDNNs where the switching of the coupling matrix follows a Markovian chain. It can be described as

where the Laplacian matrix characterizes the way the N neural networks are coupled. If there is a link from network j to network i, then ; otherwise, , . . The inner coupling matrix is denoted by . is the controller, which will be defined later in the following. In the probability space, the right-continuous Markov process is denoted as , which takes value in set . The matrix generated by the Markov process is given by , and its expression is as follows:

where is the transition rate from mode m to l, and for , while . In this study, the generator matrix is assumed to be partly unknown.

where represents the unknown transition rate. To facilitate the analysis, for , we define , where is known}, and is unknown}. To achieve global asymptotic synchronization of coupled fractional-order MRDNNs (2) with isolated fractional-order RDNNs (1). The quantized controller, as a simple and efficient controller, was used to achieve the synchronization goal.

Define the quantized set . For , the quantizer is described as

where is the quantization dead zone. , . is the quantization density; larger the value of , higher is the accuracy of the quantizer.

Remark 2.

From (3), one can realize that the quantized value is limited to a bounded sector region between two positive proportional functions with slopes and . When the quantization density ρ is determined, the bounded sector region is uniquely determined. When , then .

The quantized controller is designed as

where is mode-dependent gain matrix to be solved later, .

From Remark 2, for , there exists , such that [34]. Therefore, we get

where , .

Assume ; with the help of the Kronecker product, the compact format can be obtained as follows:

where , , , , , , , , , , , and .

Assumption A1.

There exist , , for all , such that the function satisfies the following condition

4. Main Results

4.1. Synchronization Analysis

Due to the existence of Markovian switching topology, the method of direct Lyapunov method (determining stability by calculating the fractional-order derivative of a energy function) is no longer applicable. Instead, an appropriate energy function is constructed using the states of the continuous frequency distributed model equivalent to the fractional-order system (7); by calculating its first-order derivative, the stability of the continuous frequency distributed model is determined, thus deriving the stability of the original fractional-order system. This method for determining system stability is called the indirect Lyapunov approach [35]. It should be noted that this approach differs from the commonly referred-to direct Lyapunov method and indirect Lyapunov method [36].

Based on continuous frequency distributed model in Lemma 3 and indirect Lyapunov approach, some sufficient criteria were obtained for synchronizing the coupled fractional-order MRDNNs (2) in Theorem 1. Moreover, the solution strategy, including some restricted LMIs, for solving the mode-dependent gain matrix is given in Theorem 2.

Theorem 1.

Suppose Assumption 1 holds. For a given gain , if there exist positive definite matrices , positive diagonal matrices , positive constant for , and positive definite symmetric matrices , , , such that the following matrix inequalities are satisfied:

where the detailed expansion of Ξ (including definitions of subblocks , auxiliary terms ) is provided in Appendix A, then the coupled fractional-order MRDNNs (2) can be globally synchronized onto the target system (1) under the quantized controller (4).

Proof.

According to Lemma 3, the coupled fractional-order MRDNNs (2) can be further converted into the following:

The monochromatic Lyapunov function is defined as follows:

corresponding to the elementary frequency . Summing all with the weighting function , and we describe it as follows:

Furthermore, mainly referring to the construction methods of Lyapunov functions in References [26,27,28], the following additional Lyapunov functions are constructed as follows:

with , and .

, , are positive definite real symmetric matrices. Moreover, , .

By calculating the weak-infinitesimal operator of along system (11), we obtain

As the generator Q is partly unknown, conditions (9) and (10) are proposed to deal with it. Note that ; thus

Therefore,

where , and are defined in Theorem 1.

By calculating the weak-infinitesimal operator of , we get

On the other hand,

and

By applying the extended Wirtinger inequality in Lemma 2, we get

where

Denote , . Under Assumption 1, there exist positive diagonal matrices , and such that

Remark 3.

Synchronization methodology for integer-order Markovian systems are well established [37,38], but there has been little research on fractional-order Markovian systems because of the complex features of fractional-order derivatives. Using the continuous frequency distributed model of the fractional integrator, the error system (7) is converted into an equivalent integer-order system. Therefore, the usual Lyapunov methods can be extended to analyze the synchronization of fractional-order MRDNNs.

Remark 4.

Notice that when solving LMI (8), the term is related to the transition rates. The transition rates are partly unknown and vary when the coupled topology switches, thereby impacts the solving process. This problem is dealt with as follows:

As is known}, is time invariant. It can be regarded the upper bound of and substituted into LMI (8).

Remark 5.

The obtained synchronization criteria are less conservative. First, the use of the matrix-form Wirtinger inequality, extended Wirtinger inequality, and inequalities (21) and (22) introduce many free parameters, e.g., , , , and . Second, the construction of Lyapunov functionals considered multiple variables, and this is very helpful in reducing conservativeness. Moreover, the delay integral is partitioned into , , . It will also expand the range of solution to some extent.

To solve for the control gains, Theorem 2 is presented as follows. The control gains can be directly solved by using the LMI Toolbox in Matlab according to the LMIs given in the theorem.

Theorem 2.

Assume Assumption 1 holds; for , if there exist symmetric matrices , , , , , , , , positive diagonal matrices , , and positive constant such that

and conditions (9) and (10) are satisfied, then the coupled fractional-order MRDNNs (2) can be globally synchronized onto (1). Here, , and the other elements are the same as Ξ in Theorem 1. The control gain is solved by .

4.2. LMI-Based Optimal Synchronization Design

To further minimize the control energy and obtain control parameters with reduced kinetic energy, an optimization model is constructed based on the LMI framework. The objective is to minimize the integrated control energy and synchronization error over a finite time horizon.

The energy of the control input is defined as:

where denotes the vector 2-norm. For a vector , it is defined as:

Substituting the control law (5) into the (25) yields:

For a fixed topology state , we utilize the matrix inequality (where is a scalar upper bound) to derive a conservative bound for . The norm term satisfies:

where is a positive-definite weighting matrix.

Substituting this bound into gives:

Define the weighted optimization objective as:

where

Here, is a weighting coefficient balancing control energy and synchronization accuracy. quantifies the control cost, which must be minimized. The ISE (Integral of Squared Error) term penalizes large synchronization errors, ensuring network functionality.

To ensure synchronization of fractional-order coupled MRDNNs, the control parameters must satisfy both the stability constraints from Theorem 1 and positive definiteness requirements for auxiliary variables. The optimization model is constrained as follows:

subject to:

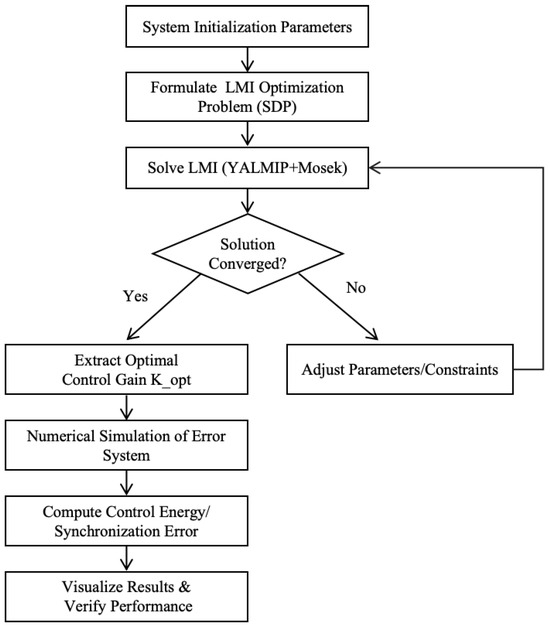

The solution procedure for the LMI-based optimization problem is illustrated in the Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Algorithm solution flowchart.

Remark 6.

The total time complexity of the LMI-based convex optimization solution is given by

The former denotes the iteration count complexity and the latter represents the per-iteration computational complexity. Specifically: p is the number of LMI constraints involved in the optimization problem with ; is the dimension of the jth LMI constraint with , for , for , ; m is the number of second-order cone (SOC) constraints with (corresponding to the constraint ); q is the total number of optimization variables with (the variables are and ).

5. Numerical Simulations

Example. Suppose , and ; i.e., the isolated fractional-order RDNNs (1) have two neurons, and the coupled MRDNNs (2) have three networks and two neurons in each network. The fractional order . The Markov process generates the coupled matrix. System (2) switches between three coupled topologies, i.e., .

The Laplacian matrices are as follows:

The other parameter matrices are as follows:

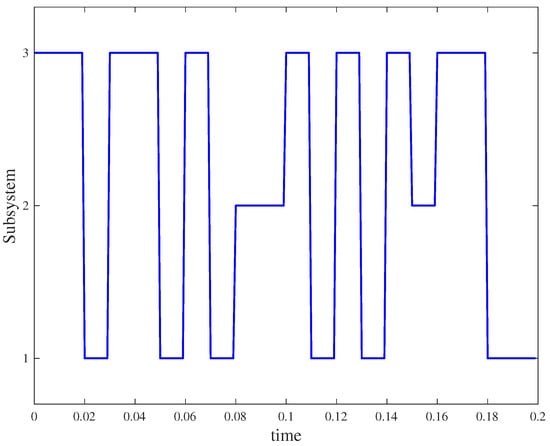

The generator matrix is partly unknown, and the Markovian switching signal is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Markovian switching signal.

The time-varying delay , , and . The initial value of (1) is . The initial values of (2) are , , . The activation function .

By solving the LMIs (9), (10), (23) and (24) with using the LMI Toolbox of MATLAB R2018a, we obtain the control gain , , as follows:

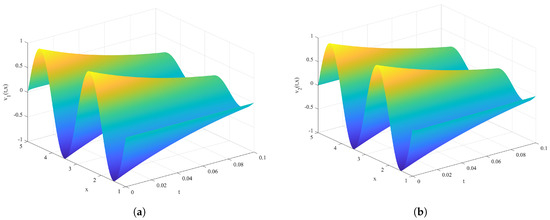

Figure 3 shows the time–space state of neurons in isolated fractional-order RDNNs (1). The reaction-diffusion phenomenon is evident from the trend of the trajectory. Moreover, the rate of reaction-diffusion is directly related to the diffusion coefficient.

Figure 3.

Time–space state of neurons (j = 1, 2) in isolated fractional-order RDNNs (1). Specifically, (a) corresponds to , (b) to .

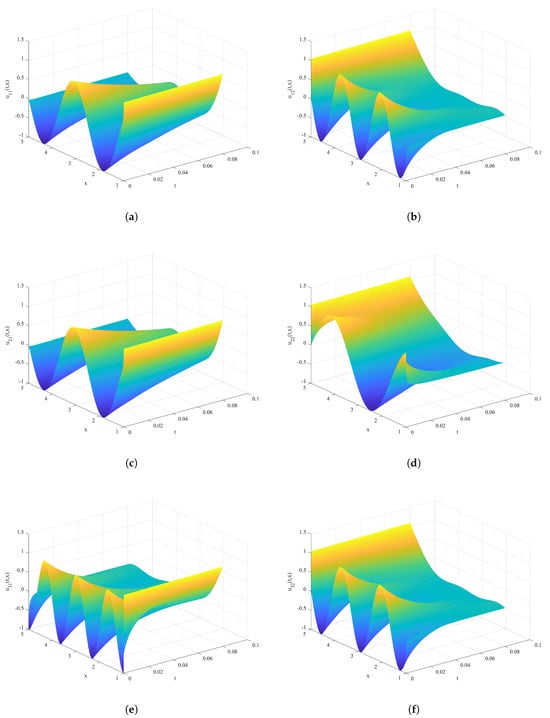

The time–space state of neurons in coupled fractional-order MRDNNs (2) is shown in Figure 3. The color scheme employed in this figure corresponds to a value-to-color mapping, with the same convention used for Figure 4 and Figure 5. We aim to synchronize the trajectory of each neuron in Figure 4 on the trajectories shown in Figure 3.

Figure 4.

Time–space state of neurons () in coupled fractional-order MRDNNs (2) without control. Specifically, (a) corresponds to , (b) to , (c) to , (d) to , (e) to , (f) to .

Figure 5.

Trajectory of synchronization error of and quantized error of (). Specifically, (a) corresponds to , (b) to , (c) to , (d) to , (e) to , (f) to .

Figure 5 shows the trajectories of synchronization and quantized errors. Owing the limited space, we only provide the error diagram of the first neuron in each network. From the figures on the right of Figure 5, we can see that the error converges to zero ultimately, implying that synchronization is achieved. Moreover, from the right side Figure 5, we can see that the quantized controller effectively reduces the channel bandwidth and communication rate.

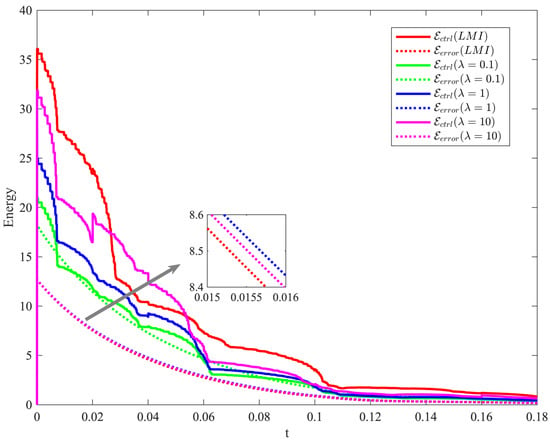

To verify the superiority of the LMI-based optimal synchronization design in regulating control energy and synchronization error, this study further solves the optimization model (27) subject to the constraint (28). Through this solution process, the dynamic evolution of the control energy and the ISE under different weight coefficients (with values of , 1, and 10) are analyzed, along with the quantitative differences between the total control energy and total error.

Figure 6 presents the variation trends of control energy and ISE with respect to time t under three operating conditions, i.e., , , and . It can be seen that the control gains obtained via the LMI-based optimization algorithm can significantly reduce control energy consumption.

Figure 6.

Variation trends of control energy and synchronization error under different conditions.

The total control energy (cumulative control input energy) and total error energy (long-term synchronization performance over a finite time horizon) are calculated via integration, with results presented in Table 1. As observed from the data in Table 1, compared to the feasible solution from the LMI Toolbox, the optimization algorithm with different values demonstrates significant improvements. For instance, when , the optimization algorithm achieves a much lower control energy than the LMI solution. Even when , although control energy is higher than that at , it is still lower than the LMI solution.

Table 1.

Performance comparison of control energy and synchronization error under different methods/weighting coefficients.

When , the design prioritizes the minimization of control energy, at the cost of a relatively large synchronization error. Conversely, when , the design prioritizes the guarantee of synchronization accuracy, with control energy increasing accordingly (while synchronization error is the smallest among all values). This indicates that the optimization algorithm can provide more flexible and superior solutions that balance control energy and synchronization error more effectively. In practical engineering, the weight coefficient can be dynamically adjusted based on the system’s priorities for energy efficiency and synchronization quality.

Remark 7.

In simulation part, L1 algorithm is adopted for Caputo time fractional-order derivative and the spatial second-order central difference quotient approximation is used for the spatial second derivative [39]. Besides, bounded smooth function vectors centered on are adopted as the initial values of the coupled fractional-order partial differential equations. This selection not only meets the stability requirements of the numerical scheme (L1 algorithm for Caputo derivatives + spatial central difference) but also adapts to the numerical implementation needs of the “global memory” characteristic of fractional-order systems, thereby ensuring the reliability of the simulation results for neuron spatiotemporal dynamics.

6. Conclusions

In this study, we investigated the synchronization of coupled fractional-order MRDNNs. Owing to the complex features of fractional-order derivatives, the synchronization methodology for integer-order Markovian systems is not applicable to fractional-order derivatives. In this study, the coupled fractional-order MRDNNs were converted into equivalent ordinary differential equations owing to the continuous frequency distributed model of the fractional integrator. Then, the indirect Lyapunov method was used to analyze the synchronization of the fractional-order Markovian systems. The quantized controller, a fundamental controller, was chosen as the synchronization controller. It effectively reduces the requirements for channel bandwidth and communication rate. By solving several LMIs, the synchronization criteria and control gains were obtained. Notably, the derived results are less conservative, and the use of matrix-form inequalities, construction of Lyapunov functions, and use of delay-partitioning technology all effectively increase the range of solutions. Moreover, we developed an innovative convex optimization model with semidefinite constraints and established an efficient offline optimization framework to achieve the precise solution of control gains. Finally, a simulation example was provided to illustrate the correctness of the obtained results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.L. and M.Z.; methodology, F.L. and Y.Y.; software, F.L. and Q.C.; validation, F.L., M.Z. and Q.C.; formal analysis, F.L.; investigation, F.L.; resources, F.L. and M.Z.; data curation, F.L.; writing—original draft preparation, F.L.; writing—review and editing, M.Z., Q.C. and Y.Y.; visualization, F.L.; supervision, Y.Y.; funding acquisition, F.L., M.Z. and Q.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by “Wuxi University Research Start-up Fund for Introduced Talents” and “the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province of China under Grant No. ZR2022QF075” and “the Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No.402331602” and “The APC was funded by the Wuxi University Research Start-up Fund for Introduced Talent”.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

The detailed expansion of matrix in Theorem 1 is provided as follows:

References

- Zhang, S.; Peng, X.; Wang, X.; Chen, C.; Zeng, Z. A Novel Memristive Multiscroll Multistable Neural Network with Application to Secure Medical Image Communication. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025, 35, 1774–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.C.; Wang, X.Y.; Ye, X.L. A new fractional-order chaos system of Hopfield neural network and its application in image encryption. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2022, 157, 111889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Hu, H.; Ding, W. A time-varying image encryption algorithm driven by neural network. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 186, 112751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Guo, Q.; Li, X.H.; Shi, T. A comprehensive review on the application of neural network model in microbial fermentation. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 416, 131801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Q. The application of neural network algorithm and embedded system in computer distance teach system. J. Intell. Syst. 2022, 31, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Liang, H. Sampled-Data Synchronization Analysis of Markovian Neural Networks With Generally Incomplete Transition Rates. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2017, 28, 740–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yang, Q.; Jiang, T.; Li, N. Synchronization Analysis of a Class of Neural Networks with Multiple Time Delays. J. Math. 2021, 2021, 5573619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, R.K.; Mondal, A.; Aziz-Alaoui, M.A. Synchronization analysis through coupling mechanism in realistic neural models. Appl. Math. Model. 2017, 44, 557–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, S.; Farokhniaee, A.; Jamali, Y. Criticality and partial synchronization analysis in Wilson-Cowan and Jansen-Rit neural mass models. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0292910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Y.; Xing, Y.; Huang, T.; Zeng, Z. Global Exponential Synchronization of Delayed Fuzzy Neural Networks With Reaction Diffusions. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2023, 31, 2809–2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Jiang, H.; Hu, C.; Abdurahman, A.; Liu, M. Adaptive pinning cluster synchronization of a stochastic reaction-diffusion complex network. Neural Netw. 2023, 166, 524–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, J. Robust synchronization of reaction-diffusion memristive neural networks with parameter uncertainties and general couplings. Neural Netw. 2025, 189, 107509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.R.; Li, C.D.; He, Z.L.; Zhang, X.Y. Synchronization of coupled reaction–diffusion neural networks via intermittent control and saturated impulses. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 2021, 35, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, B.; Kamal, S. Stabilization and Control of Fractional Order Systems: A Sliding Mode Approach; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, D.; Liao, X.; Dong, L.; Yang, R.; Yu, S.S.; Iu, H.H.C.; Fernando, T.; Li, Z. Experimental study of fractional-order RC circuit model using the Caputo and Caputo-Fabrizio derivatives. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2021, 68, 1034–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, Z.A.S.; Jasim, B.H.; Al-Yasir, Y.I.; Hu, Y.F.; Abd-Alhameed, R.A.; Alhasnawi, B.N. A new fractional-order chaotic system with its analysis, synchronization, and circuit realization for secure communication applications. Mathematics 2021, 9, 2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Wang, X.; Lai, J.; Zeng, Z. Practical finite-time synchronization of fractional-order complex dynamical networks with application to Lorenz’s circuit. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2024, 72, 4103–4114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allogmany, R.; Sarrah, A.; Abdoon, M.A.; Alanazi, F.J.; Berir, M.; Alharbi, S.A. A comprehensive analysis of complex dynamics in the fractional-order Rössler system. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butusov, D.; Rybin, V.; Karimov, A. Fast time-reversible synchronization of chaotic systems. Phys. Rev. E 2025, 111, 014213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimov, A.; Rybin, V.; Babkin, I.; Karimov, T.; Ponomareva, V.; Butusov, D. Time-reversible synchronization of analog and digital chaotic systems. Mathematics 2025, 13, 1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babkin, I.; Rybin, V.; Karimov, A.; Butusov, D. Practically feasible heuristic algorithm for time-reversible synchronization of chaotic oscillators. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2026, 202, 117470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamova, I.; Stamov, G. Mittag–Leffler synchronization of fractional neural networks with time-varying delays and reaction-diffusion terms using impulsive and linear controllers. Neural Netw. 2017, 96, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.H.; Gao, X.B.; Li, R.X. Dissipativity and synchronization control of fractional-order memristive neural networks with reaction–diffusion terms. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2019, 42, 7494–7505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Jiang, H.J.; Hu, C.; Yu, J. Synchronization for fractional-order reaction-diffusion competitive neural networks with leakage and discrete delays. Neurocomputing 2021, 436, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Jiang, J.; Hu, C.; Yu, J. Exponential synchronization of fractional-order reaction–diffusion coupled neural networks with hybrid delay-dependent impulses. J. Frankl. Inst. 2021, 358, 3167–3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.S.; Song, Q.; Cao, J.D.; Lu, J.Q. Synchronization of coupled Markovian reaction-diffusion neural networks with proportional delays via quantized control. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2018, 30, 951–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravind, R.V.; Balasubramaniam, P. Stochastic stability of fractional-order Markovian jumping complex-valued neural networks with time-varying delays. Neurocomputing 2021, 439, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakthivel, R.; Kwon, O.M.; Selvaraj, P. Observer-based synchronization of fractional-order Markovian jump multi-weighted complex dynamical networks subject to actuator faults. J. Frankl. Inst. 2021, 358, 4602–4625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Sui, X.; Shi, Z. The optimal control synchronization of complex dynamical networks with time-varying delay using PSO. Neurocomputing 2019, 333, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Q.; Wang, R.; Yang, Y. Finite-Time Cluster Synchronization of Fractional-Order Complex-Valued Neural Networks Based on Memristor with Optimized Control Parameters. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Q.; Park, J.H.; Yang, Y. The optimization of control parameters: Finite-time bipartite synchronization of memristive neural networks with multiple time delays via saturation function. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 34, 7861–7872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.K.; He, Y.; Jiang, L.; Wu, M. Stability analysis for delayed neural networks considering both conservativeness and complexity. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2015, 27, 1486–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigeassou, J.C.; Maamri, N.; Sabatier, J.; Oustaloup, A. A Lyapunov approach to the stability of fractional differential equations. Signal Process. 2011, 91, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wen, C.Y.; Yang, G.H. Adaptive backstepping stabilization of nonlinear uncertain systems with quantized input signal. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2013, 59, 460–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.H. Adaptive Control for Uncertain Fractional-Order Systems. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Automation, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ioannou, P.A.; Sun, J. Robust Adaptive Control; PTR Prentice Hall: Englewood, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.M.; Dong, H.L.; Feng, J.W. Event-triggered communication for synchronization of Markovian jump delayed complex networks with partially unknown transition rates. Appl. Math. Comput. 2017, 293, 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, K.Y.; Zhu, J.F.; Li, C.L. Exponential stabilization of Markov jump systems with mode-dependent mixed time-varying delays and unknown transition rates. Circuits, Syst. Signal Process. 2019, 38, 4526–4547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boling, G.; Xueke, P.; Fenghui, H. Fractional Partial Differential Equations and Their Numerical Solutions; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).