Abstract

The study of economic maps has consistently attracted researchers due to their rich dynamics and practical relevance. A deeper understanding of these systems enables the development of more effective control strategies. In this work, we examine the influence of the fractional order with the Caputo fractional difference on an economic market map. The primary contribution is the comprehensive analysis of how both commensurate and incommensurate fractional orders affect the stability and complexity of the map. Numerical investigations, including phase portraits, largest Lyapunov exponents, and bifurcation analysis, reveal that the system undergoes a cascade of period-doubling bifurcations before transitioning into chaos. To further characterize the dynamics, complexity is evaluated using the 0–1 test and complexity, both confirming chaotic behavior. Furthermore, two-dimensional control schemes are introduced and theoretically validated to both stabilize the chaotic economic market map and achieve synchronization with a combined response map. The theoretical and numerical results are validated through MATLAB 2016 simulations.

Keywords:

chaos; economic market; fractional discrete calculus; bifurcation; period-doubling; 0–1 test; complexity; stabilization MSC:

37N40; 39A70; 37D45; 91B55; 93D20

1. Introduction

Economic phenomena and practices are explained through the use of mathematically structured language in mathematical economics, which is one of the theoretical and practical disciplines [1,2]. The development of ideas and concepts in a form that is self-consistent and mathematically appropriate is an important objective of mathematical economics. Models of economic phenomena and processes are then built using these foundations. On the other hand, the market is a major issue in economic systems and is taken into consideration, and its consequences are thoroughly examined [3]. Economic models that depend on difference equations involving integer orders are unable to account for non-locality and memory processes. Thus, essential parts of economic processes and occurrences are not reflected by this mathematical language. When studying the suggested economic models in integer order, the underlying assumptions are based on standard macroeconomic linkages between output, demand, and investment [4,5]. In order to achieve a stable equilibrium, it is assumed that agents modify their economic choices in accordance with past market conditions. Supply and demand feedback mechanisms give rise to nonlinearities, which can produce intricate dynamics. It is essential to comprehend how the integer-order map represents the fundamental mechanics of market adjustment and stability in a memory-less context before moving on to the fractional-order scenario [4,5].

The discrete economic model with fractional order is relatively new in comparison to the continuous model. There are not many studies on discrete chaotic models in the economic domain [6,7]. In contrast, continuous economic models have been the topic of numerous recent publications [8,9,10,11]. Research has shown how to model systems in a variety of financial and economic domains, including macroeconomics and microeconomics.

Fractional calculus is considered a useful tool for representing nonlinear systems. Many real-world phenomena in a variety of fields, including neural networks [12], finance [13,14], biology [15], economics [16,17], and so on, can be more accurately described thanks to the unique properties of fractional-order systems. Therefore, it makes sense and supports arguments to use fractional calculus for presenting financial and economic models [18,19].

Recently, there has been a notable increase in the significance of chaos in economic systems. Additionally, an expansion of fractal concepts has been applied to the study of chaotic economic models [20,21]. One-parameter Mittag-Leffler as a basis of a mathematical system in [20] has been proposed to explain the Phillips curve and the relationship between inflation and unemployment rates, while Ming et al. [21] proposed a different application of fractional calculus in the economic growth systems of the Chinese economy. However, external disturbances and dynamic uncertainties always have an impact on economic systems. These features have been examined in numerous economic models, which have documented the chaotic behaviors that can result from various bifurcation types, including a period-doubling bifurcation. We explore how the complexity of market behavior can be altered by a single agent using both numerical computations and mathematical analysis. There are memory effects in many variables in economic systems, which can be described by discrete fractional calculus. Because of its captivating dynamics, the Caputo fractional derivative is also given more consideration and used in specific discrete models [22,23,24,25]. For example, a triopoly game involving bounded rationality using Caputo-like operator was proposed by Khennaoui et al. in [23]. Chu et al. [24] explored the dynamics of artificial macro-economics using fractional calculus. In [25], employing the Caputo difference discrete operator to present the fractional discrete Lotka–Volterra system. Further research into control procedures is necessary to achieve improved system synchronization and control performance in order to address these issues [26,27,28,29]. The current research is motivated by these issues. This paper delves deeply into the various nonlinear dynamical behaviors that economic maps with a market theme may exhibit, including chaos and a period-doubling bifurcation.

The essential discoveries and results obtained in this study are listed below:

- 1.

- A new chaotic fractional economic market map is examined through mathematical methods.

- 2.

- Fractional discrete calculus basics and an explanation of the new fractional form of an economic market map are provided.

- 3.

- To validate the fractional map’s complexity, we provide chaos tests, such as the 0–1 test and complexity.

- 4.

- The scheme of control for the present map stabilization and synchronization is achieved in accordance with the stability criterion for discrete nonlinear models.

The forthcoming sections are detailed as follows: certain notions and terms essential to the fractional discrete calculus are considered in Section 2. The goal of Section 3 is to create a new fractional map of the economic market while examining the chaotic dynamics concerning commensurate and incommensurate fractional-order values. After that, the complexity and 0–1 test of the chaotic map behaviors are examined in Section 4. Analytically and numerically establishing the convergence of the synchronization errors is conducted through the stabilization scheme, which is covered in Section 5. Finally, Section 6 offers a summary of this paper’s main concepts and suggests ideas for further research.

2. Fractional Discrete–Time Calculus

Let us first review some of the relevant notions of discrete fractional calculus before delving into the topic of a fractional economic market map under commensurate and incommensurate fractional orders. It is important to understand that equations with the same order form a commensurate-order fractional model. The idea of incommensurate order, on the other hand, calls for using distinct fractional orders for each form equation.

Definition 1

([30]). The ν-th discrete fractional sum for with the fractional order given by

where , with , is the starting point.

Definition 2

([31]). For and , the ν-th Caputo fractional delta operator for is expressed as

where . Such as can presented as

and

For , the ν-th Caputo discrete difference operator can expressed as

Theorem 1

([32]). The equivalent discrete integral of

can be obtained as

where

The following theorems must be established in order to determine the fractional map’s stability criteria using commensurate and incommensurate orders.

Theorem 2

([33]). The fixed point, , of a commensurate fractional discrete system where , is the Jacobian matrix at is asymptotically stable if all , , eigenvalues of satisfy

3. The Fractional Economic Market Map

The development of ideas and concepts into forms that are self-consistent and mathematically appropriate is the main objective of mathematical economics. Models of economic phenomena and processes are then built using these foundations. The variety of mathematical forms that economic models offer have made them one of the most interesting areas of study for scientists in recent years [35]. The suggested map is created using the fundamental interaction between supply and demand in a nonlinear economy [36]. In response to prior production levels, consumers alter their demand, while producers adjust their output based on past market pricing. Based on these presumptions, in our work, we introduce a new fractional-order economic market map using Caputo discrete difference operator , as given in

where , , represents the supply, denotes the demand, is the supply adjustment rate to market changes, and is the demand adjustment rate. Note that in the case where , we obtain an incommensurate fractional economic market map, whereas in the other case, we obtain a commensurate fractional economic market map. An illustration of the main characteristics of a fractional economic map (12) is shown in Figure 1. The foundation of the model is the economic market map, which captures the interactions and standards that restrict economic dynamics. This core is impacted by two essential features: chaotic behavior, which emphasizes the dynamic sensitivity to initial conditions and the creation of intricate, irregular patterns, and fractional order, which represents the presence of long-memory and global interaction impacts in the economic map. The partial overlap of the circles highlights the relationship of the map properties.

Figure 1.

The three main characteristics of the chaotic fractional economic market map (12).

3.1. Stability Analysis

Now, we assign the left0hand side of the fractional-order economic market map (12) to zero for calculating its equilibrium points as follows:

Through algebraic calculation, the fractional map has a unique independent of the controller’s parameters. The stability of the is determined using the following conditions, which are adapted from the criteria presented in [33] to examine the stability of the of map (12).

We apply the following proposition to examine the stability of the of map (12).

Proposition 1

([33]). The fractional economic market map (12) may satisfy the following conditions:

or

where

This means that the map is asymptotically stable locally.

3.2. Lyapunov Exponents, Bifurcation and Chaos

This part will examine the behavior of the fractional economic market map (12) in light of two instances: incommensurate orders and the commensurate fractional orders . Numerous numerical techniques will be used in this investigation, including the plotting of bifurcation and maximum Lyapunov exponents () and the presentation of phase portraits and time series of the suggested fractional map (12). To this aim, the numerical formula as per Theorem 1 is formulated as

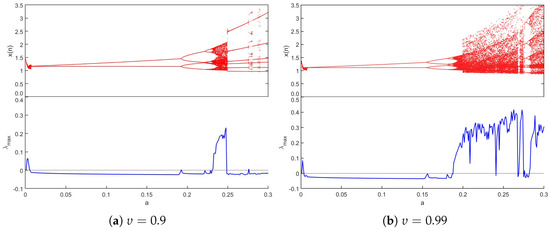

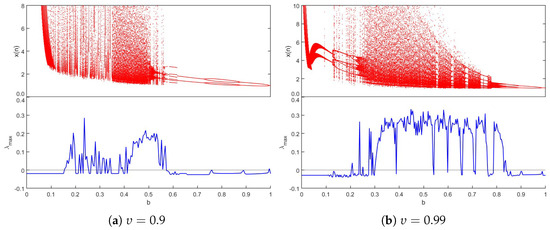

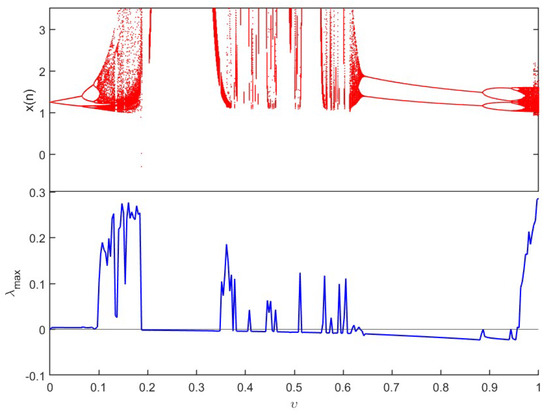

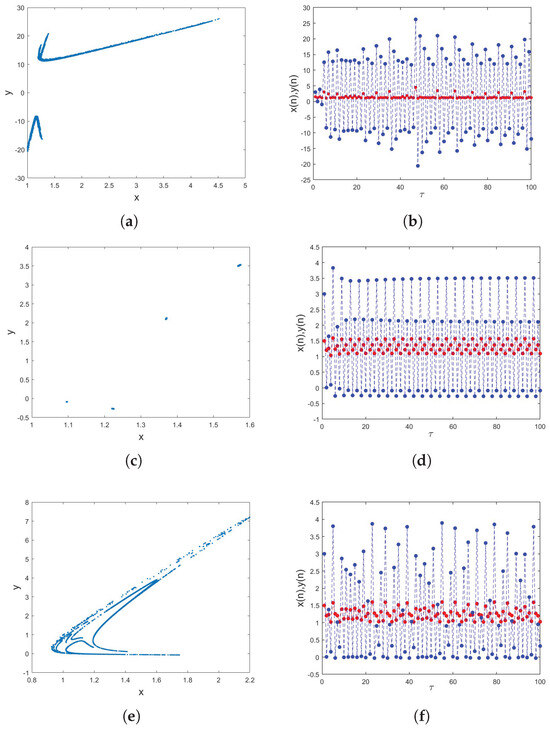

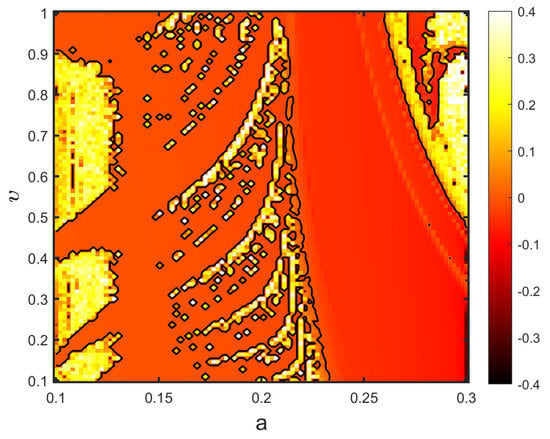

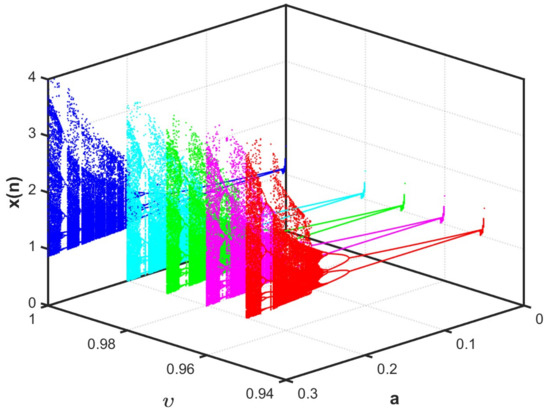

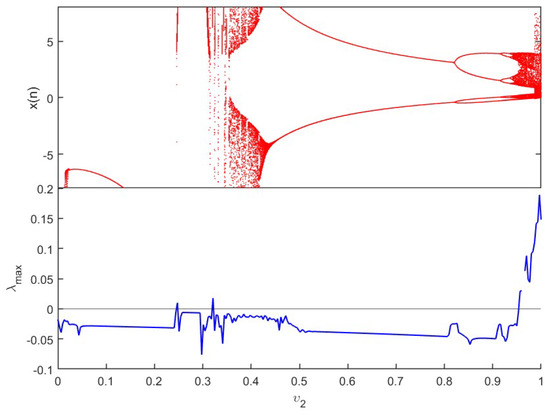

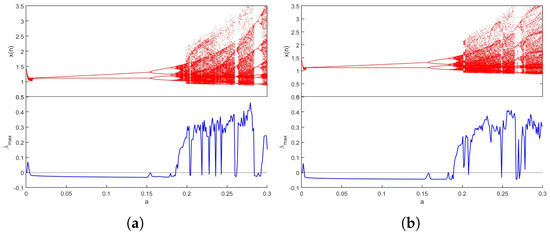

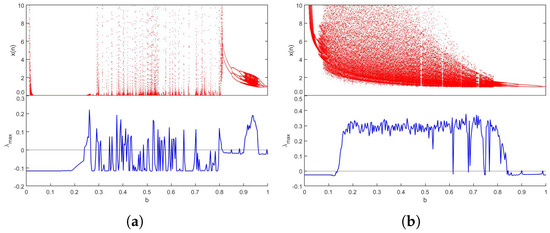

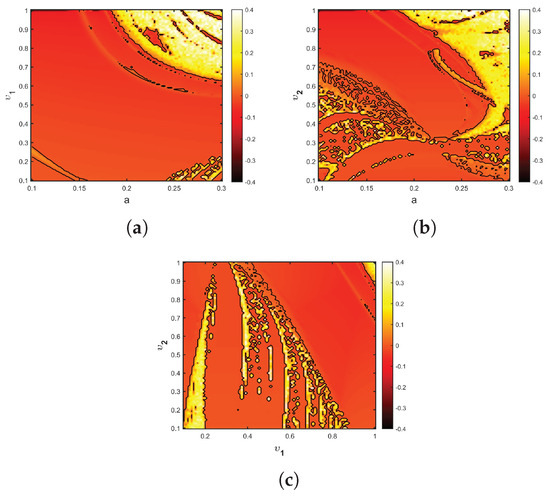

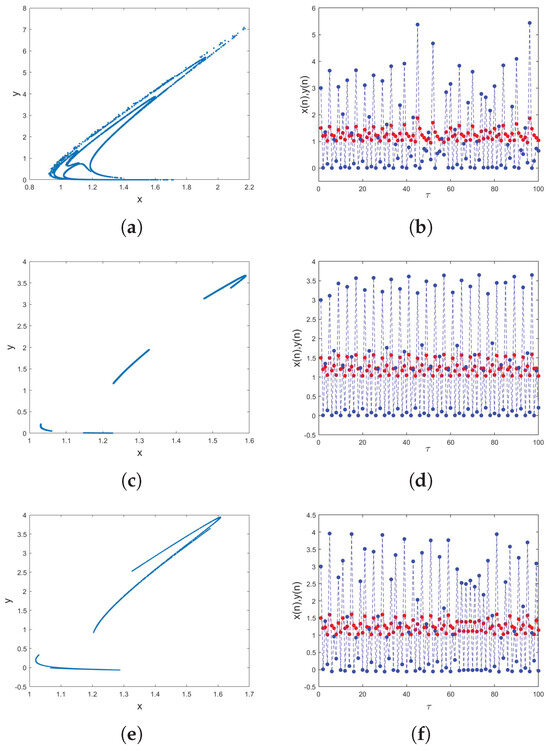

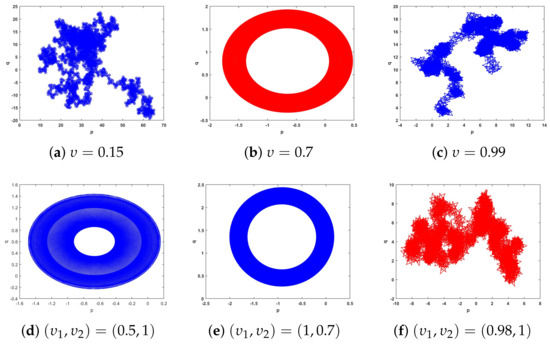

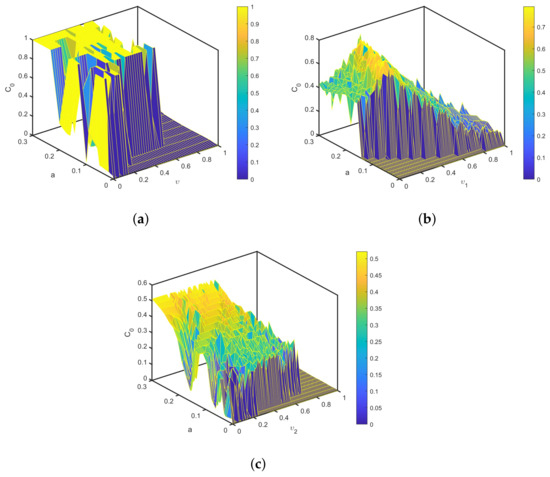

Case 1: With the aim of analyzing in greater depth the influence of commensurate derivatives on the dynamics of the fractional economic market map (12), once the two parameters, a and b, were determined to be bifurcation parameters, the bifurcation diagrams were drawn. In light of this, Figure 2 and Figure 3, respectively, present the maximum Lyapunov exponents assessed via the Jacobian Matrix method [37] and bifurcation versus a and b. First, we proposed a as the bifurcation parameter and set , as the system’s parameters, with the initial conditions (IN). When the parameter of bifurcation a was raised in for and , it is evident that the fractional economic market map (12) began in periodic states and got into chaos via the reverse period-doubling route, with a few periodic windows shown as in Figure 2. Fractional economic market map (12) has been shown to generate complex dynamical behavior depending on different values of bifurcation parameters; these include a reverse period-doubling bifurcation, a period-doubling bifurcation, and chaos. According to these diagrams, fractional economic market map (12) started in a periodic state with a negative maximum Lyapunov exponent , the fractional economic market map (12) was in a chaotic state when a increased where was positive, and it eventually entered reverse period-doubling bifurcation. In a similar manner with bifurcation parameter b in , we chose and for commensurate derivatives and , as seen in Figure 3. It is clear to see that there are multiple chaotic regions in , where chaos appears and disappears. It is evident that when b is close to 1, the states display reverse period-doubling. Next, we examine how influences fractional economic market map (12) behavior for , and in Figure 4 with step size and a time-series length of iterations. As one can note, the map is more chaotic when where has higher values, while when , chaos disappears and appears; otherwise, the states of the proposed map are stable on the rest of the intervals. For a more comprehensive understanding, Figure 5 portrays the phase plane and the corresponding time series for distinct commensurate fractional values. It is obvious that whenever the fractional values change, there is a resulting shift. The observable chaos of the fractional economic market model (12) behavior is suggested by the existence of the strange attractor when . The 2D stability map of the system in the commensurate-order case is plotted in the plane, as shown in Figure 6. Parameter a is represented by the horizontal axis, while fractional order is represented by the vertical axis. The greatest Lyapunov exponent () is represented by color, with yellow regions () denoting chaotic behavior and the remaining regions () denoting periodic dynamics. The black contour line at in the illustration clearly delineates the threshold between stability and chaos. To further examine the characteristics of fractional economic market model (12), we present bifurcation charts for various values of by taking a as the bifurcation parameter and assuming and for the remaining parameters, and the outcomes are shown in Figure 7. These analyses lead us to conclude that different fractional values produce different dynamical behaviors that influence the dynamics of fractional economic market map (12).

Figure 2.

Bifurcation and of (12) versus .

Figure 3.

Bifurcation and of (12) versus .

Figure 4.

Bifurcation and of (12) for .

Figure 5.

(a) Phase portrait for . (b) Time series of (red) and (blue) associated with (a). (c) Phase portrait for . (d) Time series associated with (c). (e) Phase portrait for . (f) Time series associated with (e).

Figure 6.

The diagram of (12) for in the plane.

Figure 7.

Bifurcation of (12) versus for various fractional-order values .

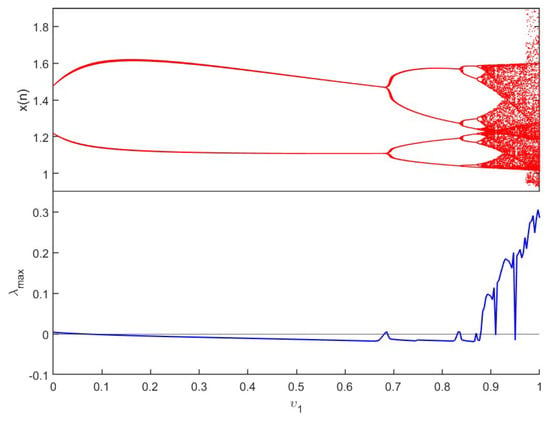

Case 2: This case is focused on investigating the dynamics of fractional economic market map (12) when . Specifically, incommensurate fractional economic market map (12), where is the bifurcation parameter that varies in and , is shown in Figure 8 along with its bifurcation and . We observe a transition in fractional economic market map (12) from stable to chaotic dynamics. Particularly, the chaotic behavior is shown when increases by means of a period-doubling bifurcation, as the values change from negative to positive. Furthermore, Figure 9 displays the bifurcation and corresponding for and , aiming to scrutinize the dynamics of (12) when varies. It seems that map (12) shows chaos when and regular states in the remainder of . To gain a more thorough comprehension of the characteristics of fractional economic market map (12), bifurcation and plots are carried out by taking into account a and b as bifurcation parameters. Figure 10 shows the period-doubling bifurcation when varies for and with , set as the system parameters. Similarly, b varies between for and in Figure 11, and we see that the dynamics of fractional economic market map (12) gradually change. In particular, when the periodic motion shrinks, a chaotic region appears, whereas as b is increased, chaos disappears. Throughout the chaotic region, the values are positive, evidently corresponding with the associated bifurcation. Since the incommensurate fractional values serve a crucial part in the dynamic behaviors of the suggested fractional economic market map (12), we can therefore confirm that it is a highly crucial parameter based on the previous findings. The 2D stability maps for the incommensurate-order case are shown in Figure 12 in planes , , and . The dynamics of the map are depicted in each subfigure as the fractional orders of the two state variables change. Stable (negative) and chaotic (positive) regimes are distinguished by the color distribution, which once more reflects . The diagram shows unequal regions of chaos in the plane, suggesting that the two fractional orders do not equally contribute to system instability. As rises, chaos emerges more quickly, demonstrating its greater influence on behavior. Regardless of the fractional orders, the maps show that the dynamics remain largely chaotic in the and planes. The variation in the dynamical reactions is increased by the greater degrees of freedom introduced by the variations in the fractional orders. All things considered, these three maps verify that the system displays a richer and more intricate bifurcation structure in the incommensurate case compared to the commensurate one. Furthermore, Figure 13 shows the phase attractors and the time series according to various incommensurate fractional values. It is clear that fractional economic market map (12) exhibits a strange attractor when . These findings suggest that, in comparison to fractional economic market map (12) with commensurate order, incommensurate fractional economic market map (12) has more complex dynamics.

Figure 8.

Bifurcation and of (12) versus and .

Figure 9.

Bifurcation and of (12) versus and .

Figure 10.

Bifurcation and of (12) versus a for (a) , (b) .

Figure 11.

Bifurcation and of (12) versus b for (a) , (b) .

Figure 12.

diagram of (12) for (a) plane, (b) plane, (c) plane.

Figure 13.

(a) Phase portrait for . (b) Time series of (red) and (blue) associated with (a). (c) Phase portrait for . (d) Time series associated with (c). (e) Phase portrait for . (f) Time series associated with (e).

4. Complexity Analysis

This part evaluates the dynamic aspects of the suggested map by looking at the intricate nature of the chaotic behaviors. Specifically, in both incommensurate and commensurate cases, the complexity of the suggested economic market map (12) is estimated using complexity and the 0–1 test.

4.1. 0–1 Test

One more technique that can be used to study the fractional orders’ impact on the fractional map’s behaviors (12) is the ‘0–1 test’; this technique [38] is another method deployed for affirming the regular behavior and chaotic regions of chaotic economic market map (12). For , is chosen at random, and the dynamics of the components

provide a visual test, and the mean square displacement is defined by

Furthermore, asymptotic growth rate is represented as

Basically, if the plot of - displays Brownian-like behavior, then output is close to 1, while if K is close to 0, then the - plane exhibits bounded-like behavior.

Table 1 and Figure 14, show the findings of the 0–1 test of the chaotic fractional economic market map for fractional values. We see that when , K is close to 1, and p-q illustrates Brownian-like behavior, it suggests that the fractional economic market map is chaotic, as confirmed by the corresponding bifurcation diagram and . Additionally, Figure 14 shows bounded-like trajectories when , affirming that fractional economic market map (12) is periodic. This confirms the previous results of Section 3.

Table 1.

The 0–1 test of chaotic fractional economic market map (12) for .

Figure 14.

The 0–1 test of (12) for fractional values.

4.2. Complexity

This part calculates the complexity of fractional economic market map (12) using the complexity algorithm [39], which comes from the inverse Fourier transform. The algorithm for is given by

- 1

- The Fourier transform of is figured out by

- 2

- Our analysis of revealed the mean square as follows: and set

- 3

- One can find the inverse Fourier transform as follows:

- 4

- Measure the complexity as

We perform a numerical evaluation of the complexity for fractional economic market map (12), setting , , and varying fractional orders , , and with , as shown in Figure 15. A higher complexity outcome indicates greater complexity in the fractional map (12). These outcomes are consistent with previous studies. Notably, the complexity is high for , , and values where was positive and drops in the periodic windows with negative values, confirming the bifurcation analysis. Thus, we are able to say that the complexity is a useful tool for precisely estimating the complexity of the map.

Figure 15.

The complexity of (12) with and (a) , (b) , , (c) , .

Remark 1.

Here, we compare the findings of Lyapunov exponents , the 0–1 test, and the complexity measure for representative parameter values compiled in Table 2 to facilitate a more thorough and detailed analysis of the various chaos detection techniques. The concordance between the three indications in detecting chaotic behavior in (12) under the same circumstances is highlighted in this comparative presentation, which validates and supports the earlier investigations.

Table 2.

Comparison of , 0–1 test, and complexity results of (12) for .

5. Chaos Control in the Fractional Economic Market Map

For the purpose of achieving stability and synchronizing the suggested fractional economic market map (12) to asymptotically drive all of its states toward zero, we propose the now adaptive laws in the next subsections.

5.1. Stabilization

We stabilize fractional economic market map (12) in two cases, and , by ensuring the stability conditions of Theorems 2 and 3 are met.

Firstly, the controlled map of fractional economic market map (12) can be described as

where and represent the adaptive controller representing the economic regulatory interventions.

Proposition 2.

The following two-dimensional control law stabilizes the fractional economic market map for the commensurate order

where .

Proof.

Proposition 3.

For the incommensurate order, the fractional economic market map is stabilized subject to the two-dimensional control law

Proof.

Substituting (37) into (33) yields

so

where ,

For

⇔

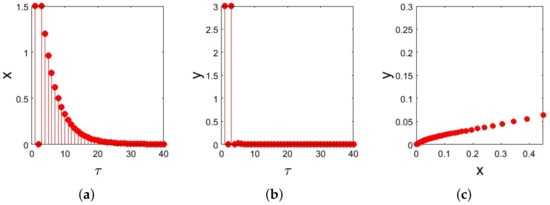

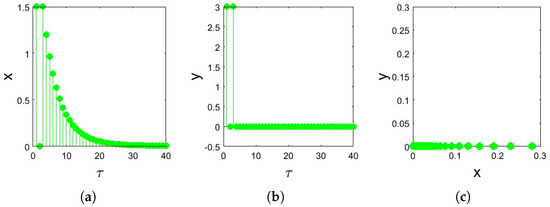

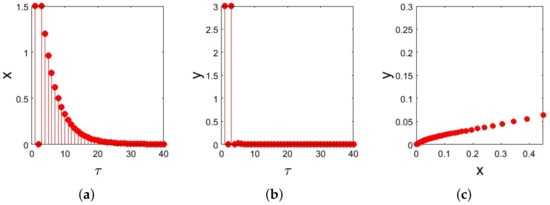

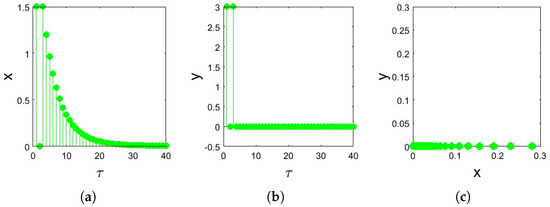

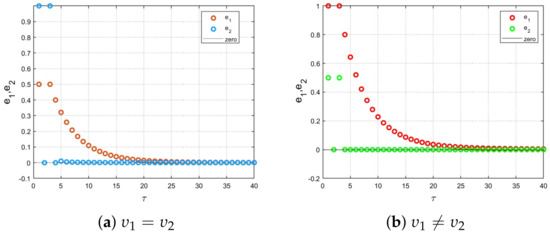

As an outcome of and Theorem 3, according to Theorem 3, the (33) map is asymptotically stable when it converges to . To verify the results, we numerically implemented Propositions 2 and 3 using Matlab for 40 iterations. In Figure 16 and Figure 17, the stabilization states of fractional economic market map (12) are displayed. □

Figure 16.

(a–c) The stabilized state of (33) when for .

Figure 17.

(a–c) The stabilized state of (33) when for .

5.2. Synchronization

Now, let us look at another kind of control for fractional economic market map (12) that has been proposed. In this part, the goal of chaos synchronization is to regulate the states of the slave ‘Response’ fractional economic market map so that they precisely match the trajectories of a fractional economic market master ‘Drive’ map. We use the subscript ℓ to indicate the slave states. Therefore, we can define the slave map as

The synchronization error conditions are described as

where , . The fractional error map can be given by

Proposition 4.

Proof.

Substituting (44) into error (45) yields

⟺

where

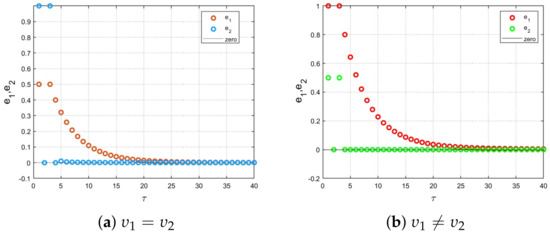

It is simple to observe that and of M for satisfy the condition of Theorems 2 and 3. Consequently, drive–response fractional economic market maps (12)–(41) are synchronized. Matlab is used to illustrate this result. We set . Figure 18 shows the states of error system (45). Thus, the errors that approach zero validate the results of the synchronization. □

Figure 18.

Time series of the synchronization errors (45).

6. Conclusions

In this work, we considered a fractional economic market map in commensurate- and incommensurate-order versions; it is a simplified abstraction of a real market. Several methods were employed to analyze the dynamics of these maps: the estimate of Lyapunov exponents, bifurcation analysis, and phase portraits all reveal that the suggested fractional map displays chaotic behavior throughout a fractional-order area. Furthermore, we provided 2D stabilization laws for the suggested maps, which incorporate adaptive supplementary terms to asymptotically move the states of the maps towards zero by applying the stability theory, and the convergence and stability of these schemes were determined. Additionally, we suggested a synchronization schema with the fractional economic market map serving as the drive map. All these notes have been validated through numerical simulation studies. These findings imply that there are significant implications when fractional-order dynamics are utilized for the proposed economic map. The appearance of chaos in the fractional-order map specifically points to long-term memory effects, which can serve as a possible source of instability since the present market behavior is dependent on previous conditions over lengthy periods of time. This emphasizes how crucial it is to take memory-dependent mechanisms into account when simulating and controlling economic maps. As a future suggestion, a variable-order fractional derivative could be used to analyze the dynamics of the proposed economic market map. Complexity studies could also be applied to maps of other fractional chaotic phenomena. Moreover, to strengthen the link between the theoretical framework and empirical data, future research could concentrate on using fractional chaotic economic models to estimate their parameters and fractional order using actual economic data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A. and O.K.; Methodology, L.D.; Software, L.D.; Validation, O.K. and A.O.; Formal Analysis, L.E.A. and M.A.; Investigation, L.D.; Resources, L.E.A. and M.A.; Data Curation, A.A., L.D. and A.O.; Writing—Original Draft, L.D.; Writing—Review and Editing, L.D. and O.K.; Visualization, L.D.; Supervision, A.O.; Project Administration, A.O.; Funding Acquisition, A.A., O.K. and M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R831), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at Northern Border University, Arar, KSA for funding this research work through the project number “NBU-FFR-2025-2443-12”.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this paper; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R831), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at Northern Border University, Arar, KSA for funding this research work through the project number “NBU-FFR-2025-2443-12”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tarasov, V.E. Mathematical economics: Application of fractional calculus. Mathematics 2020, 8, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheow, Y.H.; Ng, K.H.; Phang, C.; Ng, K.H. The Application of Fractional Calculus in Economic Growth Modelling: An Approach based on Regression Analysis. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.B.; Jahanshahi, H.; Abba, O.A.; Solís-Pérez, J.E.; Bekiros, S.; Gómez-Aguilar, J.F.; Yousefpour, A.; Chu, Y.M. The effect of market confidence on a financial system from the perspective of fractional calculus: Numerical investigation and circuit realization. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2020, 140, 110223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardini, L.; Radi, D.; Schmitt, N.; Sushko, I.; Westerhoff, F. New economic era thinking and stock market bubbles: A two-dimensional piecewise linear discontinuous map approach. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Difference Equations and Applications, Phitsanulok, Thailand, 17–21 July 2023; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 173–202. [Google Scholar]

- Gardini, L.; Radi, D.; Schmitt, N.; Sushko, I.; Westerhoff, F. Dynamics of 1D discontinuous maps with multiple partitions and linear functions having the same fixed point: An application to financial market modeling. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.20449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Chen, W. Modeling of macroeconomics by a novel discrete nonlinear fractional dynamical system. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2013, 2013, 275134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Tu, X. A new discrete economic model involving generalized fractal derivative. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2015, 2015, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farman, M.; Akgül, A.; Baleanu, D.; Imtiaz, S.; Ahmad, A. Analysis of fractional order chaotic financial model with minimum interest rate impact. Fractal Fract. 2020, 4, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Wang, H. Modeling and application of fractional-order economic growth model with time delay. Fractal Fract. 2021, 5, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, H.; Dumrongpokaphan, T.; Sitthiwirattham, T.; Alrabaiah, H.; Ansari, K.J. A numerical scheme for fractional order mortgage model of economics. Results Appl. Math. 2023, 18, 100367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tusset, A.M.; Fuziki, M.E.; Balthazar, J.M.; Andrade, D.I.; Lenzi, G.G. Dynamic analysis and control of a financial system with chaotic behavior including fractional order. Fractal Fract. 2023, 7, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hioual, A.; Alomari, S.; Al-Tarawneh, H.; Ouannas, A.; Grassi, G. Fractional discrete neural networks with variable order: Solvability, finite time stability and synchronization. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2025, 234, 2761–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasin, F.; Afzal, Z.; Arshad, M.S.; Rafaqat, M. An analytical approach for solving fractional financial risk system. Int. J. Math. Phys. 2023, 14, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diabi, L.; Ouannas, A.; Hioual, A.; Momani, S.; Abbes, A. On Fractional Discrete Financial System: Bifurcation, Chaos and Control. Chin. Phys. B 2024, 33, 100201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, M.; Eskandari, Z. Fractional calculus in ecological systems: Bifurcation analysis and continuation techniques for discrete Lotka–Volterra models. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2024, 10, 1248–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Hu, G. Stabilization and Chaos Control of an Economic Model via a Time-Delayed Feedback Scheme. Mathematics 2023, 11, 2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanshahi, H.; Sajjadi, S.S.; Bekiros, S.; Aly, A.A. On the development of variable-order fractional hyperchaotic economic system with a nonlinear model predictive controller. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2021, 144, 110698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khennaoui, A.A.; Ouannas, A. Chaos and bifurcation of fractional discrete-time population model. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Recent Advances in Mathematics and Informatics (ICRAMI), Tebessa, Algeria, 21–22 September 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Alzaid, S.S.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, S.; Alkahtani, B.S.T. Chaotic behavior of financial dynamical system with generalized fractional operator. Fractals 2023, 31, 2340056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skovranek, T. The Mittag-Leffler fitting of the Phillips curve. Mathematics 2019, 7, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, H.; Wang, J.; Fečkan, M. The application of fractional calculus in Chinese economic growth models. Mathematics 2019, 7, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.S.; Jahanshahi, H.; Din, Q.; Bekiros, S.; Alcaraz, R.; Alassafi, M.O.; Alsaadi, F.E.; Chu, Y.M. Discrete-time macroeconomic system: Bifurcation analysis and synchronization using fuzzy-based activation feedback control. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2021, 142, 110378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khennaoui, A.A.; Almatroud, A.O.; Ouannas, A.; Al-sawalha, M.M.; Grassi, G.; Pham, V.T. The effect of caputo fractional difference operator on a novel game theory model. Discret. Contin. Dyn. Syst. Ser. B 2021, 26, 4549–4565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.M.; Bekiros, S.; Zambrano-Serrano, E.; Orozco-López, O.; Lahmiri, S.; Jahanshahi, H.; Aly, A.A. Artificial macro-economics: A chaotic discrete-time fractional-order laboratory model. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2021, 145, 110776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsonbaty, A.; Elsadany, A.A. On discrete fractional-order Lotka–Volterra model based on the Caputo difference discrete operator. Math. Sci. 2023, 17, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almatroud, O.A.; Abu Hammad, M.M.; Dababneh, A.; Diabi, L.; Ouannas, A.; Khennaoui, A.A.; Alshammari, S. Multistability, Chaos, and Synchronization in Novel Symmetric Difference Equation. Symmetry 2024, 16, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calgan, H. Variable Fractional-Order Dynamics in Dark Matter–Dark Energy Chaotic System: Discretization, Analysis, Hidden Dynamics, and Image Encryption. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammad, M.M.A.; Diabi, L.; Dababneh, A.; Zraiqat, A.; Momani, S.; Ouannas, A.; Hioual, A. On New Symmetric Fractional Discrete-Time Systems: Chaos, Complexity, and Control. Symmetry 2024, 16, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Xia, L. Sliding Mode Control Design and Stability Analysis of a Class of Financial Fractional-order Chaotic Mathematical Model. Economics 2024, 1, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Atici, F.M.; Eloe, P. Discrete fractional calculus with the nabla operator. Electron. J. Qual. Theory Differ. Equ. Electron. Only 2009, 62, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdeljawad, T. On Riemann and Caputo fractional differences. Comput. Math. Appl. 2011, 62, 1602–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.C.; Baleanu, D. Discrete fractional logistic map and its chaos. Nonlinear Dyn. 2014, 75, 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čermák, J.; Győri, I.; Nechvátal, L. On explicit stability conditions for a linear fractional difference system. Electron. J. Qual. Theory Differ. Equ. Electron. Only 2015, 18, 651–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatnawi, M.T.; Djenina, N.; Ouannas, A.; Batiha, I.M.; Grassi, G. Novel convenient conditions for the stability of nonlinear incommensurate fractional-order difference systems. Alex. Eng. J. 2022, 61, 1655–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankiw, N.G.; Taylor, M.P. Economics; Cengage Learning EMEA: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Puu, T.; Panchuk, A. Nonlinear Economic Dynamics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, G.C.; Baleanu, D. Jacobian matrix algorithm for Lyapunov exponents of the discrete fractional maps. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2015, 22, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottwald, G.A.; Melbourne, I. The 0–1 test for chaos: A review. In Chaos Detection and Predictability; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 221–247. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, E.-H.; Cai, Z.-J.; Gu, F.-J. Mathematical foundation of a new complexity measure. Appl. Math. Mech. 2005, 26, 1188–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).