Abstract

This present study describes a novel manta ray foraging optimization approach based non-dominated sorting strategy, namely (NSMRFO), for solving the multi-objective optimization problems (MOPs). The proposed powerful optimizer can efficiently achieve good convergence and distribution in both the search and objective spaces. In the NSMRFO algorithm, the elitist non-dominated sorting mechanism is followed. Afterwards, a crowding distance with a non-dominated ranking method is integrated for the purpose of archiving the Pareto front and improving the optimal solutions coverage. To judge the NSMRFO performances, a bunch of test functions are carried out including classical unconstrained and constrained functions, a recent benchmark suite known as the completions on evolutionary computation 2020 (CEC2020) that contains twenty-four multimodal optimization problems (MMOPs), some engineering design problems, and also the modified real-world issue known as IEEE 30-bus optimal power flow involving the wind/solar/small-hydro power generations. Comparison findings with multimodal multi-objective evolutionary algorithms (MMMOEAs) and other existing multi-objective approaches with respect to performance indicators reveal the NSMRFO ability to balance between the coverage and convergence towards the true Pareto front (PF) and Pareto optimal sets (PSs). Thus, the competing algorithms fail in providing better solutions while the proposed NSMRFO optimizer is able to attain almost all the Pareto optimal solutions.

1. Introduction

Nowadays, meta-heuristics become popular in different research areas for resolving challenging optimization issues. These stochastic approaches are among the best and effective strategies in finding optimal solutions, conflicting with the classical (deterministic) optimization approaches which are devalued due to their drawbacks as local optima stagnation [1], etc. In spite of the benefits of the intelligence algorithms, they require some improvement to satisfy the diverse characteristics of complex real-world applications. Features that mostly faced in real issues are uncertainty [2], dynamicity [3], combinatorial, multiple objectives [4,5], constraints, etc. Along these lines, it is obviously seen that no approach is qualified in resolving the diverse kind of optimization problems. In that regard, the No-Free Lunch (NFL) theorem [6] validates this and opens the way for developers to create the newest approaches and enhances the quality of the existing ones.

Some of well-regarded meta-heuristic algorithms are: a genetic algorithm (GA), which is the first stochastic algorithm inspired by John Holland in 1960 [7], followed by simulated annealing (SA) in 1983 [8], particle swarm optimization (PSO) in 1995 by Kennedy [9], and more approaches that were developed later such as ant bee colony (ABC) [10], arithmetic optimization algorithm (AOA) [11], Harris hawks optimization (HHO) [12], sine cosine algorithm (SCA) [13], black widow optimization (BWO) [14], dynamic differential annealed optimization (DDAO) [15], levy flight distribution (LFD) [16], Salp swarm algorithm (SSA) [17], Henry gas solubility optimization (HGSO) [18], manta ray foraging optimization (MRFO) [19], and so on. All these developed stochastic algorithms are frequently single-objective; therefore, the researchers improve them according to the nature and complexity of their problems. Hence, in line with the aforementioned nature of applications, we have improved the new bio-inspired approach called manta ray foraging optimization (MRFO) [19] with a view to cope with the multi-objective problems (MOPs), which are the main focus of this paper.

During the two last years, several studies have guaranteed the superiority and efficiency of the MRFO algorithm in solving global optimization problems, such as: Fahd et al. [20], who applied the standard MRFO to perform the dynamic operation for connecting PV into the grid system. The authors in [21] have examined the global maximum power point of a partially shaded MJSC photovoltaic (PV) array applying the MRFO algorithm. Regarding the work of Selem et al. [22], the MRFO was applied to define the unknown electrical parameters of proton exchange membrane fuel cells stacks, which is considered as a constrained optimization problem. In addition, El-Hameed et al. [23] used MRFO to solve the solar module parameters’ identifications of a three diode equivalent model of PV. In addition, in an attempt to ameliorate the performance of this suggested approach, Dalia et al. [24] introduced a modified MRFO by using the fractional-order optimization algorithms, in order to enhance its exploitation ability. Referring to [25], a binary version of MRFO has been proposed using four S-Shaped and four V-Shaped transfer functions for the feature selection problem. In the bio-medical area, Karrupusamy utilized a hybrid MRFO to identify the issue in an existing brain tumor by using a convolutional neural network as a classifier that classifies the features and supplies optimal classification results [26], etc. The authors in [27] have used the multi-objective manta ray foraging optimization (MOMRFO) based weighted sum to handle the optimal power flow (OPF) problem for hybrid AC and multi-terminal direct current power grids. In Ref. [28], the authors applied the IMOMRFO to solve the IEEE-30 and IEEE-57 OPF issues.

In accordance with the literature review, the multi-objective algorithms (MOAs) are divided into two techniques: a priori versus a posteriori [29]. The first class converts the multi-objective problem to a single one, by aggregating all objectives in one function using a set of weights that are chosen by an expert in the problem domain (decision makers). The drawback of this method appears when we generate the Pareto optimal set, we should run the algorithm multiple times. Alternatively, the second class is the posteriori technique which does not require any addition weights. In this method, the multi-objective formulation is maintained and the Pareto optimal set is obtained in just one run; then, the decision-making occurs after the optimization. In addition, the Pareto front of all kinds of problems can be determined utilizing this posteriori technique, which is the focus of this work, in which a new multi-objective version of MRFO based non-dominated sorting approach named NSMRFO was developed.

Different shapes of fronts exist in multi-objective problems: linear, convex, concave, separated, and so on. Therefore, to obtain an accurate approximation Pareto optimal front for every multi-objective optimization issues, three fundamental challenges should be addressed: distribution of solutions (coverage), accuracy (convergence), and local fronts [30]. Thus, an efficient algorithm is the one that has the ability to balance between them: avoid a premature convergence and extract a uniform distribution front covering the entire true Pareto optimal front. Some of the most popular multi-objective algorithms are: Non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm (NSGA) [31,32], strength Pareto evolutionary algorithm (SPEA) [33,34], multi-objective particle swarm optimization (MOPSO) [35], and multi-objective evolutionary algorithm based on decomposition (MOEA/D) [36].

Since the multi-objective optimization problem appears, the non-dominated sorting strategy with crowding distance and non-dominated ranking has been known as the efficient and most significant mechanisms in handling the algorithms for solving the multi-objective problems. The significant advantages of the NSGA-II and its borrowed MOAs motivated us to suggest a novel multi-objective variant of the MRFO approach, which is based on the NSGA-II outstanding operators. The search mechanism in MRFO is kept similar in the NSMRFO optimizer. Furthermore, in order to assess the NSMRFO success, various MMMOEAs with other MOEAs were investigated for comparisons with respect to diverse indicator metrics in search and objective spaces. Thus, with accordance to the statistical outcomes, the proposed NSMRFO outperformed its competitors and even the existing MOMRFOs for different kinds of problems.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- A new multi-objective version of manta ray foraging optimization based the crowding distance and non-dominated sorting operators has been introduced.

- Various performance metrics have been employed in order to affirm the NSMRFO effectiveness.

- The suggested NSMRFO was benchmarked on the standard unconstrained, constrained multi-objective test suites, CEC2020 multi-modal multi-objective optimization functions as well as engineering design problems to verify its validity.

- The IEEE 30-bus OPF as one of the most significant real-world issues in the power system is investigated with wind/solar/small-hydro energy sources for the first time with the multi-objective case.

The remainder of this paper is arranged in four sections as follows: Section 2 summarizes the basic definitions of the multi-objective problems, and then describes the proposed algorithm MRFO and the structure of its multi-objective version NSMRFO. Simulation results, analyses, and competing algorithms are discussed in Section 3. As a final point, Section 4 concludes this work and proposes some future research directions.

2. Multi-Objective Optimization

As mentioned before, the multi-objective problem is the subject of handling problems that need optimizing more than one objective simultaneously, which are mostly in conflict. The basic mathematical formulation of the multi-objective optimization for such minimization problem can be defined as:

where is the objective function to be optimized, is the equality constraints, is the inequality constraints, , m, p, and n are the numbers of objective functions, inequality constraints, equality constraints, and variables. and are the boundaries of the ith variable.

The arithmetic relational operators cannot be effective in multi-objective optimization to compare the search space of different solutions. Alternatively, the Pareto optimal dominance concept is utilized to determine which solution is better than another. The essential definitions of dominance relation are defined as follows [37,38]:

Let us take two vectors and

Definition 1

(Pareto Dominance). is said to dominate if and only if is partially less than (i.e., ):

Definition 2

(Pareto Optimality). is called a Pareto-optimal solution iff:

Definition 3

(Pareto Optimal Set). The Pareto optimal set is a set that comprises all Pareto optimal solutions (neither dominates nor dominates ):

Definition 4

(Pareto Optimal Front). The Pareto optimal front is defined as:

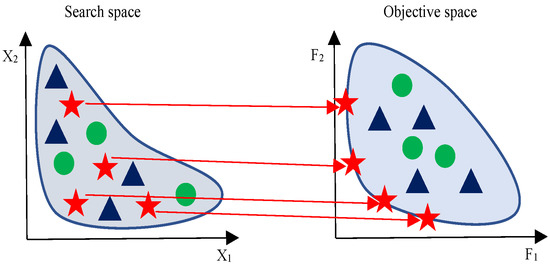

In such multi-objective optimization problem, a solution is the set of best non-dominated solutions. Therefore, the Pareto optimal solutions projection in the objective space are kept in a set called Pareto optimal front as illustrated in Figure 1. The solutions of both spaces obviously reveal that the green shapes are better than the others, since they dominate all other colors.

Figure 1.

Parameter and objective spaces.

The concept of the MRFO standard version is explained briefly in the following section.

2.1. Manta Ray Foraging Optimizer (MRFO)

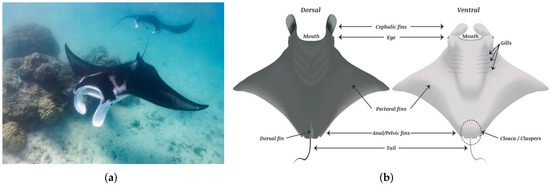

MRFO is among the recent algorithms proposed in 2020, inspired by giant known critters of the sea called Manta Rays [19]. Figure 2 depicts the shape of a manta ray. To establish this algorithm, the authors mimic three feeding behaviors of Manta Rays: chain, somersault, and cyclone feeding. Furthermore, the manta rays are assumed as search agents which explore the planktons’ location and proceed towards them. Then, the planktons at significant concentration represent the best solution. The source code of MRFO is given in https://www.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/73130-manta-ray-foraging-optimization-mrfo (accessed on 24 May 2021).

Figure 2.

Manta ray body form. (a) Manta ray in the ocean; (b) parts of a manta ray, dorsal, and ventral.

Following the population-based optimization algorithms, the steps of MRFO are randomly initialized as illustrated below:

where and are the maximum and minimum bounds of variables in the search space, rand is a random number between 0 and 1, .

The three main operators are mathematically clarified in the next subsections.

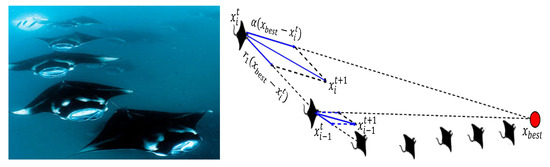

2.1.1. Chain Foraging

In this foraging strategy, about 50 Mantas line up head to tail forming an orderly line. The chain swims towards the position of intense concentration of plankton with a fully open mouth. The missing plankton by the leader (manta at the top of the chain) will be devoured by the followers. In the course of the foraging process, the position of each follower is updated towards the best source of plankton and individuals in front of it. This foraging phase is depicted in Figure 3. The mathematical updating formulas are presented as follows:

where is the position of ith manta ray in the jth dimension, and are the random vector in range [0, 1], is the best plankton concentration position, and is a weight coefficient that is expressed as:

where and introduce the random vector in range [0, 1].

Figure 3.

Simulation model of chain foraging behavior.

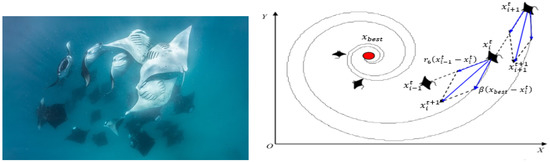

2.1.2. Cyclone Foraging

Cyclone foraging phase follows the feeding strategy in WOA [39] in terms of spiral movement. After discovering a significant amount of plankton in the profundity of the ocean, the mantas move one behind another towards plankton making a spiral shape. This foraging phase is illustrated in Figure 4. The manta updates its position based on its best previous position and the manta in front of it.

Figure 4.

Simulation model of cyclone foraging behavior.

The spiral-shaped movement is mathematically modeled as:

where and present the random value in [0, 1]; is the weight coefficient that is formulated as:

where denotes the random vector in range [0, 1], and T and t are the maximum and current iteration, respectively.

The cyclone foraging can be considered as the main phase in MRFO, in which it performs the intensification (exploitation) and diversification (exploration) mechanisms. The exploitation improvement is achieved based on considering the best plankton found so far as a reference point. On the other hand, the exploration phase incites MRFO to reach the overall optimal solution in accordance with the mathematical equations described below:

where is the random position generated inside the search space.

2.1.3. Somersault Foraging

The last phase in MRFO is somersault feeding, wherein the manta ray swims to and fro around a pivot point and somersaults around itself to a new position. Figure 5 illustrates this feeding behavior. The manta updates its position using the following mathematical model:

where , depict the random values between 0 and 1. S is the somersault factor, .

Figure 5.

Simulation model of somersault foraging behavior.

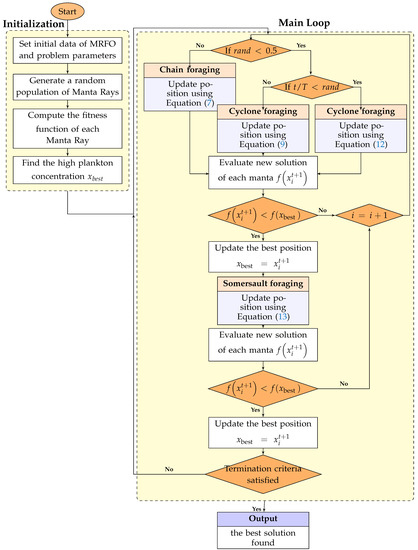

MRFO’s diversification and intensification phases are balanced using the variations value , which is gradually increased. The expression denotes the exploration stage, reversibly, and the exploitation process is adopted. The main steps followed in MRFO are demonstrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

MRFO flowchart for the minimization problem.

block = [rectangle split, draw, rectangle split parts=2, text width=10em, text centered, minimum height=4em] grnblock = [rectangle, draw, fill=green!20, text width=10em, text centered, minimum height=3em] whtblock = [rectangle, draw, fill=white!20, text width=12em, text centered, minimum height=3em] line = [draw, -latex’] cloud = [draw, ellipse,fill=orange!50, node distance=2cm, minimum height=2em] diam=[draw,diamond,fill=orange!60,text width=9em, text centered, inner sep=-2pt] container = [draw, rectangle,dashed,inner sep=0.28cm, rounded corners,fill=yellow!20,minimum height=4cm]

2.2. Proposed (NSMRFO)

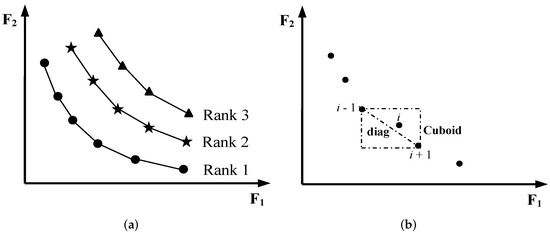

As MRFO is relevant for single objective issues, we have developed a multi-objective version of MRFO to handle problems with many fitness functions by applying the Pareto dominance strategy. This variant is inspired from the non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm (NSGA-II) approach, which is the most popular and efficient algorithm in the area of multi-objective optimization in the literature. The non-dominated sorting (NDS) technique employs the crowding distance to define an ordering among individuals and preserve the diversity and the elitist mechanism. To compute all non-dominated solutions, a ranking process is applied called non-dominated ranking (NDR), in which the front that is not dominated by any solutions is assigned to rank 1, while rank 2 is in accordance with the front that is dominated by at least one of the solutions, and so on; the ranking scheme is described in Figure 7a. The crowding distance value of a particular solution is the average distance of its two neighboring solutions as illustrated in Figure 7b. Therefore, the less value of crowding distance denotes comparatively the higher crowded space and conversely. The formulation of this crowding distance mechanism is defined as below:

where and are the minimum and maximum values of the ith objective function.

Figure 7.

Non-dominated ranking fonts (a); crowding-distance calculation (b).

It is worth discussing here that the (NDS) provides a probability to the dominated solutions to be chosen as well, which enhances the diversification of the suggested algorithm. The pseudo-code of NSMRFO is depicted in Algorithm 1. The computational space complexity of NSMRFO is the same as NSGA-II of the order of , where M is the number of objectives, and N is the number of manta rays, while the computational complexity was found to be much better than that of some of the approaches such as SPEA and NSGA, which are of .

| Algorithm 1 Non-Dominated Sorting Manta Ray Foraging Optimization |

|

2.3. Evaluation Criteria

The employed performance metrics are described in this section. The performance indicators are one of the techniques employed for measuring the potential of a multi-objective algorithm in terms of the diversity and coverage. In this work, various metrics are used such as generational distance (GD) [40], inverted generational distance (IGD) [41] in search [42] and objective [42] spaces, spacing (SP) [43], Pareto sets proximity (rPSP) [44] and reciprocal of hypervolume (rHV) [45], which are formulated as follows:

- Generational Distance (GD) [40]:

- Inverted Generational Distance (IGD) [41]:

is the IGD in search space. is the IGD in objective space:

- Spacing (SP) [43]:

- Reciprocal of Pareto sets proximity (rPSP) [44]:

where is the cover rate. m is the number of objective functions. D is the number of decision variables. , are the true and obtained Pareto front, respectively:

- Reciprocal of hypervolume (rHV) [45]:

3. Experimental Results and Analysis

In this section, the effectiveness of the proposed multi-objective approach is carried out by using 18 different unconstrained benchmark functions, the CEC2020 benchmark test that contains 24 functions, four constrained problems, four engineering design problems, and the IEEE 30-bus optimal power flow issue incorporating wind/solar/small-hydro power. These test suites have different shapes of front like linear, convex, concave, connected, disconnected, etc., as indicated in Table 1. Five analyses are investigated to prove the robustness of the developed NSMRFO algorithm, the first one aims to assess the convergence by using generation distance (GD) metric, the second evaluates the diversity by computing the spacing (SP) metric, the inverse generation distance (IGD) in the search and objective spaces metric, which intends to affirm the NSMRFO’s efficacy in balancing between convergence and diversity, and the reciprocal of Pareto sets proximity (rPSP) and hypervolume (rHV). Moreover, for evaluating the NSMRFO approach, 11 significant multi-objective optimization algorithms are re-implemented, which are named: multi-objective slime mould algorithm (MOSMA) [46], multi-objective bonobo optimizer based decomposition (MOBO/D) [47], multi-objective multi-verse optimization (MOMVO) [48], multi-objective water cycle algorithm (MOWCA) [49], non-dominated sorting grey wolf optimizer (NSGWO) [50], multi-objective manta ray foraging optimizer (MOMRFO) [51], improved multi-objective manta ray foraging optimizer (IMOMRFO) [28], non-sorting genetic algorithm II (NSGA-II) [32], double niched non sorting genetic algorithm II (DN-NSGA) [52], omni optimizer (OMNI) [53], a multi-objective particle swarm optimizer using ring topology (MO_ Ring_ PSO_ SCD) [44], and their characteristics are shown in Table 2. The MATLAB codes for these algorithms were downloaded from: https://aliasgharheidari.com/SMA.html (SMA), https://www.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/79843-multi-objective-bonobo-optimizer-with-decomposition-method (BO), https://seyedalimirjalili.com/mvo (MVO), https://ali-sadollah.com/water-cycle-algorithm-wca/ (WCA), https://www.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/75259-multi-objective-non-sorted-grey-wolf-mogwo-nsgwo?s_tid=srchtitle_nsgwo_1 (GWO), https://www.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/103530-momrfo-multi-objective-manta-ray-foraging-optimizer?s_tid=srchtitle_MOMRFO_1 (MRFO), https://www.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/103895-improved-multi-objective-manta-ray-foraging-optimization?s_tid=srchtitle_MOMRFO_2 (IMRFO), and the codes of the other algorithms and the CEC2020 test suite can be found https://www.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/103895-improved-multi-objective-manta-ray-foraging-optimization?s_tid=srchtitle_MOMRFO_2, respectively (all accessed on 7 August 2021). Each approach is executed on a personal computer, Windows 8.1 (64-bit), core i5 with 4GB-RAM Processor @1:8 GHz using MATLAB R2020a. All benchmark functions are executed 20 times for 1000 iterations and 100 populations, except the CEC2020 problem, which is executed 21 times for a population , and a maximum number of function evaluations equal to 10,000 *. In addition, the OPF problem was repeated 20 time for and 200 iterations. Note that the best performing algorithm is assessed based on the mean and standard deviation outcomes. The quantitative and qualitative performance outcomes are illustrated in Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7, Table 8, Table 9, Table 10, Table 11, Table 12, Table 13, Table 14 and Table 15 and Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15 and Figure 16, respectively. The outcomes of each set of benchmark functions are outlined and discussed in the following sections.

Table 1.

Descriptions of the unconstrained, constrained, and CEC2020 benchmark functions.

Table 2.

Parameter settings of the tested algorithms.

Table 3.

GD, IGD, and SP metrics comparison based on unconstrained test suites.

Table 4.

GD, IGD, and SP metrics comparison based on constrained test suites.

Table 5.

rPSP, rHV, IGDX, and IGDF indicator metrics comparison based on CEC2020 test suites.

Table 6.

GD, IGD, and SP metrics comparison based on engineering design test suites.

Table 7.

The characteristics of the system.

Table 8.

Cost and emission coefficients of thermal generators [54].

Table 9.

Characteristic details of wind/solar/small-hydro generators [54].

Table 10.

Findings of best objectives for case 1.

Table 11.

Findings of best compromise solutions for case 1.

Table 12.

Findings of best objectives for case 2.

Table 13.

Findings of best compromise solutions for case 2.

Table 14.

Findings of best objectives for case 3.

Table 15.

Findings of best compromise solutions for case 3.

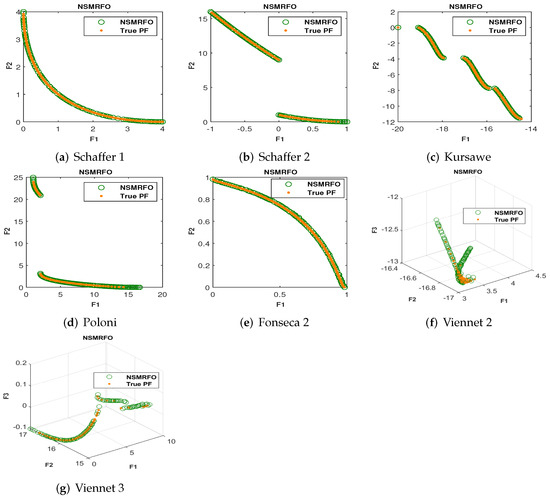

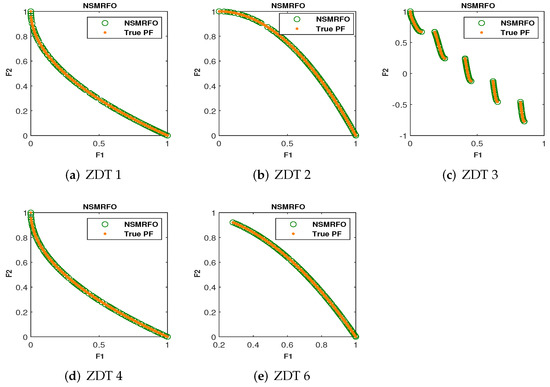

Figure 8.

Obtained Pareto front of NSMRFO on classical test suites.

Figure 9.

Obtained Pareto front of NSMRFO on ZDT test suites.

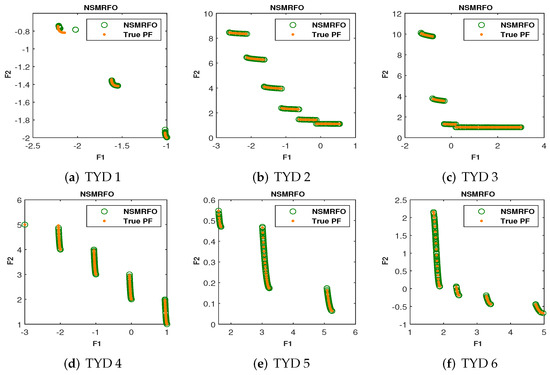

Figure 10.

Obtained Pareto front of NSMRFO on TYD test suites.

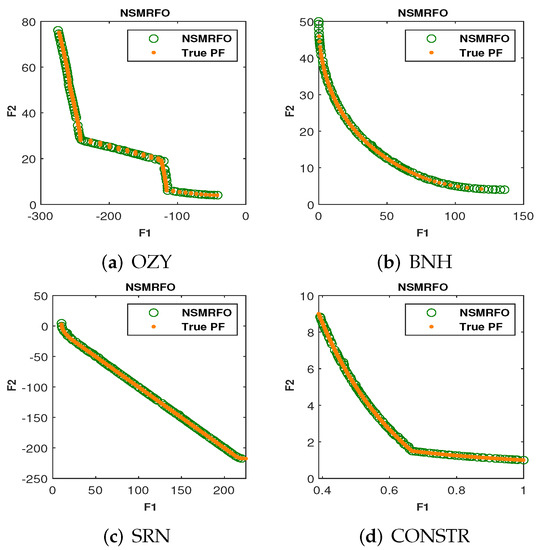

Figure 11.

Obtained Pareto front of NSMRFO on constrained test suites.

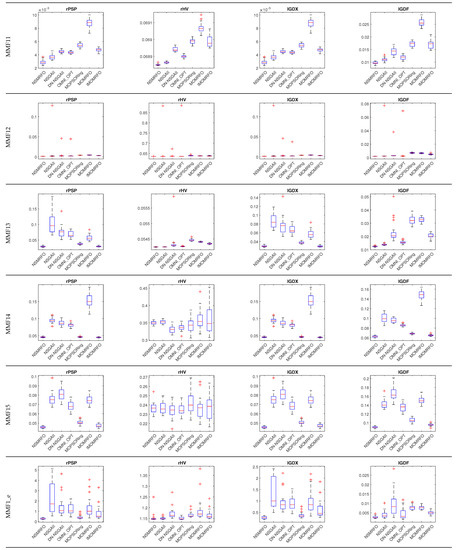

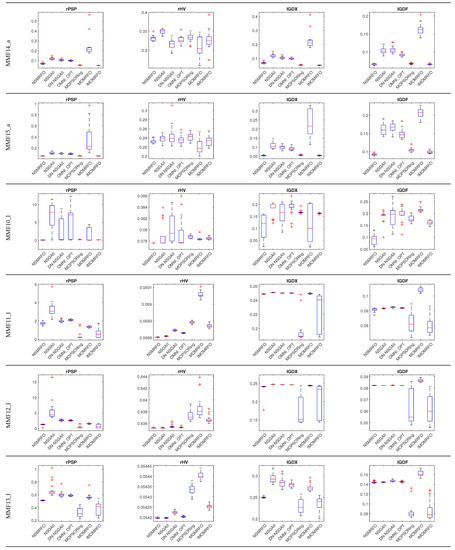

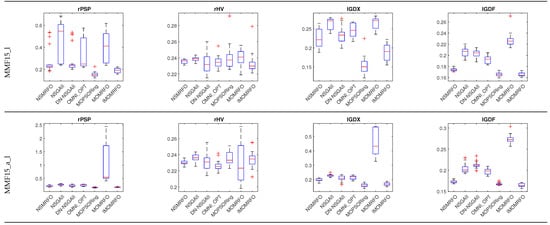

Figure 12.

Cont.

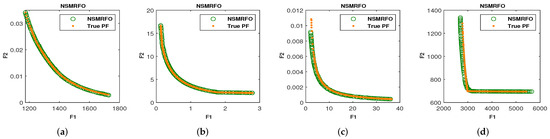

Figure 13.

Obtained Pareto front of NSMRFO on engineering design test suites. (a) 4-bar truss; (b) disk brake; (c) welded beam; (d) speed reducer.

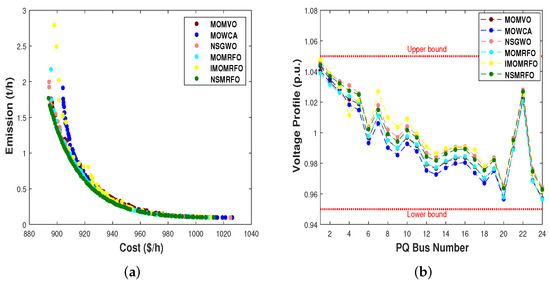

Figure 14.

Optimal Pareto fronts of all the algorithms for case 1. (a) Pareto front of optimal solutions; (b) voltage profile of PQ buses.

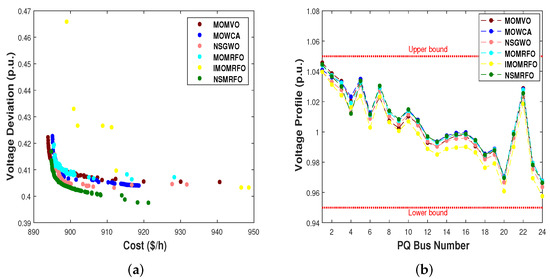

Figure 15.

Optimal Pareto fronts of all the algorithms for case 2. (a) Pareto front of optimal solutions; (b) voltage profile of PQ buses.

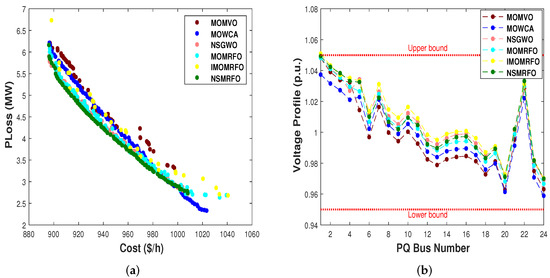

Figure 16.

Optimal Pareto fronts of all the algorithms for case 3. (a) Pareto front of optimal solutions; (b) voltage profile of PQ buses.

3.1. Evaluation on Unconstrained Benchmark Functions

As mentioned above, the proposed approach is tested firstly on the classical unconstrained test problems with two and three objectives. The achieved mean and STD values of 20 runs of each parameter metrics from NSMRFO and different approaches are presented in Table 3 and indicated in bold. It is worth noting here that the better algorithm is the one with the lower metric value. The suggested approach NSMRFO managed to outperform the MOSMA [46], MOBO/D [47], MOMVO [48], MOWCA [49], MOMRFO [51], (IMOMRFO) [28], and (NSGA-II) [32] optimizer significantly on eight functions out of 18 cases for GD, 14 out of 10 cases for IGD, and 14 out of 18 cases for SP metrics. By comparison, MOSMA is better on SCH2 for all metrics, the MOWCA is best on FON2 for GD, on POL for IGD, on POL, and VNT3 for SP, the MOMVO is best on just SCH1 for SP metric, the IMOMRFO is best on SCH1 for GD, and VNT2 for IGD; however, the NSGA-II and MOMRFO offered a good solution on four and eight functions, respectively. By contrast, the MOBO/D optimizer provides the worst results. Therefore, it may be observed from this table that the NSMRFO approach is able to outperform all competitors on most cases. Furthermore, it is also evident from Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10 that NSMRFO converges better toward a true Pareto front with different features from diverse perspectives. In addition, the Pareto optimal solutions have been well distributed over the true PF on the classical functions.

3.2. Evaluation on Constrained Benchmark Functions

To evaluate the accuracy of the developed NSMRFO approach, four constrained test functions with different Pareto optimal fronts and three analysis metrics were investigated. Inspecting the obtained Pareto fronts in Figure 11, and the outcomes in Table 4, it is clearly seen that the suggested NSMRFO yields a higher convergence and coverage toward the true PF on all constrained benchmark functions. For the numerical results, NSMRFO ranks first for the majority of functions except on BNH and CONSTR for GD, and BNH, SRN for IGD in which it ranks second compared to the aforementioned well-known competitive techniques, and OZY for SP. Note that the optimal findings are marked in boldface and underlined.

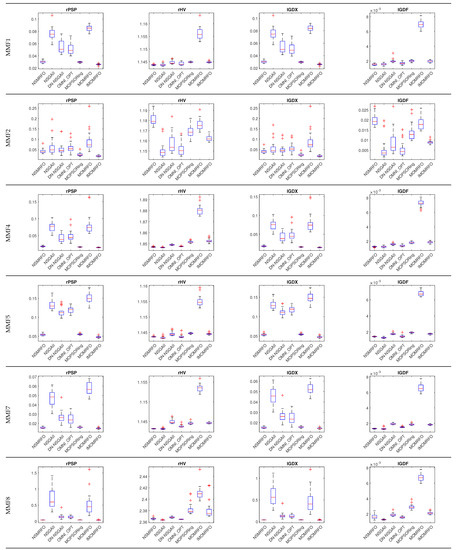

3.3. Evaluation on CEC2020 Benchmark Functions

This subsection presents the performance of the suggested technique NSMRFO in CEC2020 multimodal multi-objective optimization (MMO) problems using four indicator metrics, the and that reflect the quality of the Pareto set in the search space, and the and that reflect the quality of the Pareto front in the objective space. The functions of the remaining MMO problems are characterized by different geometries’ linear and nonlinear concave and convex functions. To illustrate the effectiveness of the multi-objective MRFO version, six well-known competitors are adopted for comparison such as: NSGA-II [32], DN-NSGAII [52], OMNI-OPT [53], MO_Ring_PSO_SCD [44], MOMRFO [51], IMOMRFO [28]. The numerical statistical results of the obtained parameter indexes in search and objective spaces by each approach are summarized in Table 5. It is worth noting that the optimal results of each indicator are the lowest values. The underlined bold solutions indicate the algorithms’ optimum result. Additionally, the last five rows posted in this table present the results score of each approach, in which the NSMRFO ranks first by providing 47 optimal solutions out of a 96 benchmark suite, which means twenty-four functions times four indicators. By contrast, the MOMRFO, OMNI-OPT, and DN-NSGAII competitor approaches show the worst scores. It can be clearly observed from the perspective of the search space values that the crowding distance mechanism has the capability to efficiently increase the PS convergence and diversity of the optimization algorithms. However, In spite of the same strategy used in NSGAII, DN-NSGAII, and the proposed optimizer, they offered a significant different performance, which means that the NSMRFO diversity and convergence are improved. The IMOMRFO was the closest approach of NSMRFO, where it ranks second by having 20 best values out of 96, and it offered good search space results and poor objective space results. The NSGAII performed a little better on the objective space, especially the metric. The CEC2020 corresponding box plots of the four metrics rPSP, rHV, IGDX, and IGDF are depicted in Figure 12. According to this figure, the NSMRFO achieved the indicator minimum values in most MMFs such as MMF1, MMF4, MMF5, MMF7, MMF8, MMF11, MMF12, MMF13, MMF14, MMF15, MMF1_e, MMF14_a, MMF15_a, MMF10_l, rHV on MMF11_l, rPSP and rHV on MMF12_l, rHV on MMF13_l, rPSP and rHV on MMF15_a_l. In addition, the NSMRFO is more stable compared to its competitor approaches. To sum up, the suggested optimizer achieves the best rank performance in terms of all indicator metrics compared to its competing algorithms, and have significant stability.

3.4. Evaluation on Engineering Design Problems

For examining the applicability of an algorithm, the engineering design problems can be very beneficial. In this subsection, four engineering functions are considered in order to assess the capability of NSMRFO in dealing with the real-word problems. The first one is 4-bar truss, and it aims to optimize the volume and deflection with four dimensions. The disk brake consists of minimizing the stopping time and weight of a brake system with four dimensions. The third engineering problem is the welded beam that tends to decrease the vertical deflection and cost of fabrication with four dimensions. The speed reducer as a last function attempts to reduce its stress and total weight with seven dimensions. For results verification, seven well-known approaches are applied. The statistical results are summarized in Table 6, and it is evident that NSMRFO can outrank the other algorithms on the most problems except the 4-bar truss for the GD metric, the welded beam for GD and SP metrics, and disk brake for SP metric; it ranks first in 8 out of 12 test suites. Accordingly, the NSGA-II and MOMRFO are the closest competitors where they provide good estimations on two functions over 12. However, concerning the other algorithms MOSMA, MOBO/D, MOMVO and IMOMRFO, they have the lowest results. As illustrated in Figure 13, the NSMRFO Pareto front shows higher approximations toward the true PFs in terms of coverage and convergence.

3.5. Evaluation on OPF Incorporating Wind/Solar/Small-Hydro Energy

3.5.1. Problem Methodology

Wind Power

The wind cost can be expressed as below:

with

where , , and are the coefficients of direct, over, and under estimation cost, respectively. , are the scheduled and actual available power, respectively. is rated power output from the plant. is the probability density function of the wind power plant.

Solar power

The total solar cost can be formulated as follows:

with

where , and are the coefficients of direct, over and under estimation cost of solar power generator. , are the scheduled and actual available power, respectively. The probability of occurrence of solar power shortage. and are the expectations of solar power above and below .

Small-hydro power

The Small-hydro power is defined as follows:

with

where is the small-hydro direct cost coefficient. and are the coefficients of over and under estimation cost of combined solar and small-hydro power generator. , are the scheduled and actual available power, respectively. and are the expectations of combined system power above and below .

Objective functions

- Total cost

The network total cost including the thermal/wind/solar/small-hydro generators is modeled as follows:

where

, and are the conventional generators cost coefficients. and are the coefficients for the valve-point loading effect.

- Emission

The emission function is formulated using an exponential function as shown below [54]:

where , , , , and are the emission coefficients of the power plant.

- Voltage deviation

The voltage deviation is calculated by:

- Power loss

The Power loss is calculated by:

where represents the conductance of line l. represents the voltage angle difference between bus i and bus j.

Constraints

- Equality constraints

The power flow equations are assumed as equality constraints that are represented by:

where is the number of buses. and are generated reactive and active power, respectively. and are reactive and active power demand, respectively. and represent the admittance matrix components called the conductance and susceptance.

- Inequality constraints

The inequality constraints are given as below:

- −

- Generator constraints:

- −

- Security constraints:

where is the number of transmission lines. and indicate the maximum limit of the transmission line.

3.5.2. Results of the OPF Problem

To assess performance of the suggested algorithm NSMRFO against other approaches, several cases related to the modified IEEE 30-bus optimal power flow problem integrating wind/solar/small-hydro power are investigated. This test system comprises 41 branches, 6 generating units in which 3 thermal generators at buses 1, 2, and 8, the wind and solar plants at buses 5 and 11, respectively, while combined solar and small-hydro generators are connected to bus 13 as summarized in Table 7. The detailed input data for the considered IEEE 30-bus system are given in [54]. The thermal generators’ coefficients are provided in Table 8. Solar irradiance, wind distribution, and small-hydro river flow rate are modeled using Lognormal, Weibull, and Gumbel probability density function (PDF), respectively [54]. These PDF parameters are listed in Table 9. Additionally, in terms of the optimization issue, the system has 11 control variables, with various constraints and objective functions for a total active and reactive power demands of 283.4 MW and 126.2 MVAR, respectively.

To validate the suggested approach, five well-known stochastic algorithms are employed as competitors, namely MOMVO [48], MOWCA [49], NSGWO [50], MOMRFO [51], and IMOMRFO [28]. The test system under study is examined via three case studies defined as follows:

- Minimizing the total cost and emission;

- Minimizing the total cost and voltage deviation;

- Minimizing the total cost and power loss.

The optimum settings of the control variables, their allowable ranges, the numerical best outcomes of each objective, and the best compromise solutions (BCS) are depicted in Table 10, Table 11, Table 12, Table 13, Table 14 and Table 15. Furthermore, their optimal Pareto fronts are illustrated in Figure 14a–Figure 16a. It is worth noting that all the findings are generated after twenty independent runs for a population size of 100 and 200 iterations. According to the aforementioned tables, it is obviously seen that the NSMRFO’ results are remarkably better than the competitor approaches in all cases, notably the best compromise solutions’ tables. In addition, it is clearly observed from the figures that the suggested NSMRFO can generate the superior Pareto non-dominated solutions with good distribution and good diversification front in comparison to other algorithms. As shown in Figure 14b–Figure 16b, the BCS’ voltage profile PQ of load buses do not exceed their limits, and remained within the minimum and maximum bounds.

3.6. Discussion

As previously stated, the main difference between the suggested approach and its competitors is the better diversity and accuracy for the majority of the problems, in which the NSMRFO ranks first, followed by the MOMRFO on the unconstrained problems, the NSGA-II on the constrained test suite, the NSGA-II on the engineering problems, and the IMOMRFO on the CEC2020 benchmark MMO functions, while the MOWCA gives a little better score. By contrast, the MOSMA, MOMVO and MOBO/D provide the worst rank. However, on the other hand, the NSMRFO generates very challenging and competitive solutions on most benchmark test suites. In summary, all quantitative and qualitative outcomes and analysis reveal the higher accuracy and significant diversity of NSMRFO in dealing with different unconstrained, constrained, CEC 2020 multimodal multi-objective, and engineering benchmark functions. This comes from the strong ability of MRFO in exploitation and exploration as long as the NSMRFO employs similar mechanisms as its single approach, and inherits its high convergence. In addition, the crowding distance and archive selection methodologies also contribute to the NSMRFO high coverage and convergence.

4. Conclusions

In this work, the ability of a suggested multi-objective manta ray foraging optimizer known as NSMRFO to handle problems with different characteristics has been tested. The NSMRFO optimizer has been developed on the basis of NSGA-II operators as crowding distance, elitist non-dominated sorting, and an archive mechanism. A set of test functions have been employed to benchmark the performance of the NSMRFO approach from different perspectives that include: seven classical, ZDT, TYD, four constrained, twenty-four CEC2020, four problems for engineering design, and the IEEE 30-bus OPF with renewable sources wind/solar/small-hydro power. Additionally, to qualitatively affirm the achieved solutions, the original true Pareto fronts have been compared to those obtained. Thereby, for performance assessment, various performance metrics in search and objective spaces have utilized such generational distance (GD), inverted generational distance (IGDX and IGDF), spacing metric, reciprocal Pareto sets proximity (rPSP), and reciprocal hypervolume (rHV). Thus, NSMRFO can relatively provide an accurate estimation shape with closer distance to the true PF compared to the multimodal multi-objective evolutionary approaches and some recent competitive algorithms. The NSMRFO impressive performance leads to handling challenging real-world problems in various engineering fields for future works.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.D. and M.O.; methodology, F.D.; software, F.D.; validation, R.E., M.O. and S.K.; formal analysis, F.D.; investigation, S.K.; resources, M.O. and A.M.A.; data curation, F.D.; writing—original draft preparation, F.D. and S.K.; writing—review and editing, F.D. and A.M.A.; visualization, R.E. and M.O.; supervision, R.E. and M.O.; project administration, R.E. and S.K.; funding acquisition, A.M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Deputyship for Research & Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia through the project number “IF_2020_NBU_408”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not Applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deputyship for Research & Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia for funding this research work through the project number “IF_2020_NBU_408”. The authors gratefully thank the Prince Faisal bin Khalid bin Sultan Research Chair in Renewable Energy Studies and Applications (PFCRE) at Northern Border University for their support and assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kelley, C.T. Detection and remediation of stagnation in the Nelder–Mead algorithm using a sufficient decrease condition. SIAM J. Optim. 1999, 10, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, H.-G.; Sendhoff, B. Robust optimization a comprehensive survey. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2017, 196, 3190–3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbig, M.; Engelbrecht, A.P. Performance measures for dynamic multi-objective optimisation algorithms. Inf. Sci. 2013, 250, 61–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- von Lucken, C.; Baran, B.; Brizuela, C. A survey on multi-objective evolutionary algorithms for many-objective problems. Comput. Optim. Appl. 2014, 58, 707–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, K. Multi-Objective Optimization Using Evolutionary Algorithms; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2001; Volume 16. [Google Scholar]

- Wolpert, D.H.; Macready, W.G. No free lunch theorems for optimization. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 1997, 1, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holland, J. Adaptation in Natural and Artificial Systems; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick, S.; Gelatt, C.D.; Vecchi, M.P. Optimization by simulated annealing. Science 1983, 220, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.; Eberhart, R.C. Particle swarm optimization. In Proceedings of the ICNN’95—International Conference on Neural Networks, Perth, WA, Australia, 27 November–1 December 1995; pp. 1942–1948. [Google Scholar]

- Basturk, B.; Karaboga, D. An artificial bee colony (ABC) algorithm for numeric function optimization. In IEEE Swarm Intelligence Symposium; IEEE Press: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 2006; pp. 4–12. [Google Scholar]

- Abualigah, L.; Diabat, A.; Mirjalili, S.; Abd-Elaziz, M.; Gandomi, A.H. The arithmetic optimization algorithm. Comput. Meth. Appl. Mech. Eng. 2021, 376, 113609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, A.A.; Mirjalili, S.; Faris, H.; Aljarah, I.; Mafarja, M.M.; Chen, H. Harris hawks optimization: Algorithm and applications. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 97, 849–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S. SCA: A Sine Cosine Algorithm for solving optimization problems. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2016, 96, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayyolalam, V.; Pourhaji, K.A.A. Black Widow Optimization Algorithm: A novel meta-heuristic approach for solving engineering optimization problems. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intel. 2020, 87, 103249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafil, H.N.; Jármai, K. Dynamic differential annealed optimization: New metaheuristic optimization algorithm for engineering applications. Appl. Soft Comput. 2020, 93, 106392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essam, H.H.; Mohammed, R.S.; Fatma, A.H.; Hassan, S.; Hassaballah, M. Lévy flight distribution: A new metaheuristic algorithm for solving engineering optimization problems. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intel. 2020, 94, 103731. [Google Scholar]

- Mirjalili, S.; Gandomi, A.H.; Mirjalili, S.Z.; Saremi, S.; Faris, H.; Mirjalili, S.M. Salp Swarm algorithm: A bio-inspired optimizer for engineering design problems. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2017, 114, 163–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, F.A.; Houssein, E.H.; Mabrouk, M.S.; Al-Atabany, W.; Mirjalili, S. Henry gas solubility optimization: A novel physics-based algorithm. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 101, 646–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, L. Manta ray foraging optimization: An effective bio-inspired optimizer for engineering applications. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2020, 87, 103300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alturki, F.A.; Omotoso, H.O.; Al-Shamma’a, A.A.; Farh, H.M.H.; Alsharabi, K. Novel Manta Rays Foraging Optimization Algorithm Based Optimal Control for Grid-Connected PV Energy System. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 187276–187290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathy, A.; Rezk, H.; Yousri, D. A robust global MPPT to mitigate partial shading of triple-junction solar cell-based system using manta ray foraging optimization algorithm. Sol. Energy 2020, 207, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selem, S.I.; Hasanien, H.M.; El-Fergany, A.A. Parameters extraction ofPEMFC’s model using manta rays foraging optimizer. Int. J. Energy Res. 2020, 44, 4629–4640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hameed, M.A.; Elkholy, M.M.; El-Fergany, A.A. Three-diode model for characterization of industrial solar generating units using Manta-rays foraging optimizer: Analysis and validations. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 219, 113048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.E.; Dalia, Y.; Mohammed, A.A.A.; Amr, M.A.; Ahmed, G.R.; Ahmed, A.E. A Grunwald–Letnikov based Manta ray foraging optimizer for global optimization and image segmentation. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2021, 98, 104105. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, K.K.; Guha, R.; Bera, S.K.; Kumar, N.; Sarkar, R. Sshaped versus V-shaped transfer functions for binary Manta ray foraging optimization in feature selection problem. Neural Comput. Appl. 2021, 33, 11027–11041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karrupusamy, P. Hybrid Manta Ray Foraging Optimization for Novel Brain Tumor Detection. Trends Comput. Sci. Smart Technol. 2020, 2, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, A.M.; El-Sehiemy, R.A.; Elsayed, A.M.; Elattar, E.E. Multi-objective manta ray foraging algorithm for efficient operation of hybrid AC/DC power grids with emission minimization. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2021, 15, 1314–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahraman, H.T.; Akbel, M.; Duman, S. Optimization of Multi-Objective Optimal Power Flow Problem Using Improved MOMRFO with a Crowding Distance-Based Pareto Archive Strategy. Appl. Soft Comput. 2022, 116, 108334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marler, R.T.; Arora, J.S. Survey of multi-objective optimization methods for engineering. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2004, 26, 369–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branke, J.; Kaußler, T.; Schmeck, H. Guidance in evolutionary multi-objective optimization. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2001, 32, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, N.; Deb, K. Muiltiobjective optimization using nondominated sorting in genetic algorithms. Evol. Comput. 1994, 2, 221–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, K.; Pratap, A.; Agarwal, S.; Meyarivan, T. A fast and elitist multi-objective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2002, 6, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zitzler, E. Evolutionary Algorithms for Multiobjective Optimization: Methods and Applications. Ph.D. Thesis, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH), Zurich, Switzerland, November 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Zitzler, E.; Thiele, L. Multiobjective evolutionary algorithms: A comparative case study and the strength pareto approach. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 1999, 3, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coello, C.A.C.; Pulido, G.T.; Lechuga, M.S. Handling multiple objectives with particle swarm optimization. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2004, 8, 256–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, H. MOEA/D: A multiobjective evolutionary algorithm based on decomposition. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2007, 11, 712–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareto, V. Cours d’Economie Politique: Librairie Droz; Librairie Droz: Geneva, Switzerland, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Coello, C.A.C. Evolutionary multi-objective optimization: Some current research trends and topics that remain to be explored. Front. Comput. Sci. China 2009, 3, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S.; Lewis, A. The whale optimization algorithm. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2016, 95, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Veldhuizen, D.A.; Lamont, G.B. Multiobjective Evolutionary Algorithm Research: A History and Analysis; Technical Report TR-98-03; Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Graduate School of Engineering, Air Force Institute of Technology, Wright-Patterson AFB: Dayton, Ohio, USA, 1998; pp. 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Sierra, M.R.; Coello, C.A.C. Improving PSO-based multi-objective optimization using crowding, mutation and ∈-dominance. In Evolutionary Multi-Criterion Optimization; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 505–519. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.; Suganthan, P.N.; Qu, B.Y.; Gong, D.W.; Yue, C.T. Problem Definitions and Evaluation Criteria for the CEC 2020 Special Session on Multimodal Multiobjective Optimization; Zhengzhou University: Zhengzhou, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Schott, J.R. Fault Tolerant Design Using Single and Multicriteria Genetic Algorithm Optimization, DTIC Document. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, C.; Qu, B.; Liang, J. A Multi-objective Particle Swarm Optimizer Using Ring Topology for Solving Multimodal Multi-objective Problems. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2017, 22, 805–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, K.; Ishibuchi, H.; He, L.; Pang, L.M. A survey on the hypervolume indicator in evolutionary multi-objective optimization. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2021, 25, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premkumar, M.; Jangir, P.; Sowmya, R.; Alhelou, H.H.; Heidari, A.A.; Chen, H. MOSMA: Multi-Objective Slime Mould Algorithm Based on Elitist Non-Dominated Sorting. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 3229–3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.K.; Nikum, A.K.; Krishnan, S.V.; Pratihar, D.K. Multi-objective Bonobo Optimizer (MOBO): An intelligent heuristic for multi-criteria optimization. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2020, 62, 4407–4444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S.; Jangir, P.; Mirjalili, S.Z.; Saremi, S.; Trivedi, I.N. Optimization of Problems with Multiple Objectives using The Multi-Verse Optimization Algorithm. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2017, 134, 50–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sadollah, A.; Eskandar, H.; Kim, J.H.; Bahreininejad, A. Water cycle algorithm for solving multi-objective optimization problems. Soft Comput. 2015, 19, 2587–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangir, P.; Jangir, N. A new Non-Dominated Sorting Grey Wolf Optimizer (NS-GWO) algorithm: Development and application to solve engineering designs and economic constrained emission dispatch problem with integration of wind power. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2018, 72, 449–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Got, A.; Zouache, D.; Moussaoui, A. MOMRFO: Multi-objective Manta ray foraging optimizer for handling engineering design problems. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 237, 107880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ishibuchi, H.; Nojima, Y.; Masuyama, N.; Shang, K. A double-niched evolutionary algorithm and its behavior on polygon-based problems. In International Conference on Parallel Problem Solving from Nature; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 262–273. [Google Scholar]

- Deb, K.; Tiwari, S. Omni-optimizer: A generic evolutionary algorithm for single and multi-objective optimization. Eur. Oper. Res. 2008, 185, 1062–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, P.P.; Suganthan, P.N.; Qu, B.Y.; Amaratunga, G.A.J. Multi-objective economic-environmental power dispatch with stochastic wind-solar-small hydro power. Energy 2018, 150, 1039–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).